Connexin43 Controls the Myofibroblastic Differentiation of Bronchial Fibroblasts from Patients with Asthma (original) (raw)

Journal Article

Department of Cell Biology, Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland

Search for other works by this author on:

Department of Cell Biology, Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland

Search for other works by this author on:

Department of Cell Biology, Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland

Search for other works by this author on:

Department of Cell Biology, Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland

Search for other works by this author on:

Department of Cell Biology, Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland

Search for other works by this author on:

Department of Cell Biology, Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland

Search for other works by this author on:

Katarzyna A. Wójcik-Pszczoła ,

Katarzyna A. Wójcik-Pszczoła

Department of Cell Biology, Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland

Department of Medicine, Jagiellonian University Medical School, Kraków, Poland

Search for other works by this author on:

Center for Molecular Cardiology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland and

Search for other works by this author on:

Department of Cell Biology, Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland

Search for other works by this author on:

Department of Medicine, Jagiellonian University Medical School, Kraków, Poland

Search for other works by this author on:

Accepted:

31 January 2017

Cite

Milena Paw, Izabela Borek, Dawid Wnuk, Damian Ryszawy, Katarzyna Piwowarczyk, Katarzyna Kmiotek, Katarzyna A. Wójcik-Pszczoła, Małgorzata Pierzchalska, Zbigniew Madeja, Marek Sanak, Przemysław Błyszczuk, Marta Michalik, Jarosław Czyż, Connexin43 Controls the Myofibroblastic Differentiation of Bronchial Fibroblasts from Patients with Asthma, American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology, Volume 57, Issue 1, July 2017, Pages 100–110, https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2015-0255OC

Close

Navbar Search Filter Mobile Enter search term Search

Abstract

Pathologic accumulation of myofibroblasts in asthmatic bronchi is regulated by extrinsic stimuli and by the intrinsic susceptibility of bronchial fibroblasts to transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). The specific function of gap junctions and connexins in this process has remained unknown. Here, we investigated the role of connexin43 (Cx43) in TGF-β–induced myofibroblastic differentiation of fibroblasts derived from bronchoscopic biopsy specimens of patients with asthma and donors without asthma. Asthmatic fibroblasts expressed considerably higher levels of Cx43 and were more susceptible to TGF-β1–induced myofibroblastic differentiation than were their nonasthmatic counterparts. TGF-β1 efficiently up-regulated Cx43 levels and activated the canonical Smad pathway in asthmatic cells. Ectopic Cx43 expression in nonasthmatic (Cx43low) fibroblasts increased their predilection to TGF-β1–induced Smad2 activation and fibroblast–myofibroblast transition. Transient Cx43 silencing in asthmatic (Cx43high) fibroblasts by Cx43 small interfering RNA attenuated the TGF-β1–triggered Smad2 activation and myofibroblast formation. Direct interactions of Smad2 and Cx43 with β-tubulin were demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation assay, whereas the sensitivity of these interactions to TGF-β1 signaling was confirmed by Förster Resonance Energy Transfer analyses. Furthermore, inhibition of the TGF-β1/Smad pathway attenuated TGF-β1–triggered Cx43 up-regulation and myofibroblast differentiation of asthmatic fibroblasts. Chemical inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication with 18 α-glycyrrhetinic acid did not affect the initiation of fibroblast–myofibroblast transition in asthmatic fibroblasts but interfered with the maintenance of their myofibroblastic phenotype. Collectively, our data identified Cx43 as a new player in the feedback mechanism regulating TGF-β1/Smad–dependent differentiation of bronchial fibroblasts. Thus, our observations point to Cx43 as a novel profibrotic factor in asthma progression.

Clinical Relevance

This work demonstrates that connexin43 (Cx43) controls the susceptibility of bronchial fibroblasts to transforming growth factor-β/Smad–dependent myofibroblastic differentiation and contributes to the maintenance of the phenotype of differentiated myofibroblasts. Cx43 plays a crucial role in the feedback mechanism regulating the activity of the canonical transforming growth factor-β/Smad signaling pathway. Cx43 should therefore be considered an important player in airway fibrosis and asthma progression.

Local tissue fibrosis accompanies chronic inflammatory disorders that lead to the functional impairment of numerous tissues and organs (1–5). In chronic lung diseases, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and bronchial asthma, pulmonary dysfunction is attributed to the fibrotic remodeling of airway and lung parenchymal compartments. Bronchial asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases throughout the world, with a continuously increasing prevalence observed over the last decades (6). Epithelial damage and subepithelial fibrosis commonly result in airway remodeling and in the thickening of asthmatic bronchial walls during the asthmatic process. Phenotypic shifts, such as the epithelial–mesenchymal transition and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)–inducible fibroblast–myofibroblast transition (FMT), determine these pathological processes because they lead to the accumulation of myofibroblasts in bronchial walls (1, 7). Myofibroblasts combine the extracellular matrix–producing activity of fibroblasts with the characteristics of the smooth muscle cells (i.e., a high contractility and the presence of prominent α-smooth muscle actin [α-SMA]positive microfilament bundles) (8). Normally, myofibroblasts accumulate in response to tissue damage and are cleared during the repair process. Chronic inflammation is considered to increase the longevity of bronchial myofibroblasts (9) through paracrine (e.g., TGF-β–dependent) and cell adhesion–dependent mechanisms (7, 10, 11). Thus, the activity of myofibroblasts is pathologically prolonged during bronchial asthma. However, the role of connexins in the regulation of FMT in asthmatic bronchi has not yet been investigated.

Connexins constitute a family of transmembrane proteins involved in the synchronization of cellular functions (including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and motility) within multicellular tissue compartments (12). When built into the membranes of adjacent cells, two hexameres of connexins (connexons) form intercellular aqueous channels, which aggregate into semicrystalline clusters (gap junctions). Such channels mediate the intercellular diffusion of small molecules (<1.5 kD) (i.e., gap junctional intercellular coupling [GJIC]). Unpaired connexons can also act as membrane channels that mediate cell communication with extracellular milieu (13, 14). Finally, connexin molecules localized within the intracellular compartments regulate intracellular signaling pathways in a GJIC-independent manner (15, 16). For example, connexin43 (Cx43) regulates the activity of Smad-dependent TGF-β signaling in cardiac cells (17, 18).

Cx43 is expressed abundantly in the respiratory system (19, 20). Recent data has shown up-regulation of Cx43 in a mouse model of asthma (21); however, the role of Cx43 expressed by human bronchial fibroblasts (HBFs) in the asthmatic process has not been addressed. In this study, we investigated the involvement of Cx43 in the TGF-β–inducible myofibroblastic differentiation of bronchial fibroblasts. We used an in vitro model of cultured lineages of HBFs derived from biopsy specimens of donors with asthma (AS) and donors without asthma (NA). Using this model, we have previously reported enhanced fibrogenic potential of AS HBFs (10, 22–26). Here, we analyzed the GJIC-dependent and GJIC-independent involvement of Cx43 in the initiation of TGF-β1–induced FMT in AS and NA HBFs and in the maintenance of their myofibroblastic phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Propagation of Primary HBFs

Primary HBFs were isolated as described previously (22) from bronchial biopsy specimens derived from five patients with moderate to severe asthma (AS group), three males and two females aged 39 ± 17.6 years. The mean duration of asthma in the AS group was 16.7 ± 12.2 years (FEV1 % = 48.75 ± 0.86). The control (NA) group consisted of five individuals (three males and two females) aged 57.4 ± 9.9 years, in whom diagnostic bronchoscopy ruled out any serious airway pathology (including asthma, chronic inflammatory lung disease, or cancer; FEV1 % = 101.83 ± 14.7). All patients were treated at the Department of Medicine, Jagiellonian University Medical School and were in stable clinical condition. The study was approved by the University’s Ethics Committee (Decision No. 122.6120.69.2015). After the establishment of primary cultures, HBFs between the 5th and 15th passage were harvested for end point experiments. Human recombinant TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) was administered alone or in combination with SB-431542 (10 μM), PD98059 (20 μM), 5Z-7-oxozeaenol (10 μM), and 18 α-glycyrrhetinic acid (AGA) (10–50 μM) in serum-free conditions. The cells were incubated for 7 days before end point analyses, with the exception of Smad2 analyses, which were performed 1 hour after TGF-β1 administration. Where indicated, Smad2 and Smad2/3 were silenced in HBFs by specific small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and Cx43 was silenced and/or overexpressed in HBFs by siRNA and Cx43 expression vector, respectively. In these experiments, the end point analyses were performed 7 or 14 days after TGF-β1 application. Detailed culture protocols are available in the online supplement (see Figure E1 in the online supplement).

Cell Imaging and Gene Expression Analyses

α-SMApositive microfilament bundles were immunodetected in HBF populations to identify myofibroblasts (23). In addition, immunodetection of phospho-Smad (p-Smad)2(S467), Smad2, Cx43, and vinculin and visualization of F-actin and DNA in HBFs were performed. Image acquisition was performed with a Leica DMI6000B microscope (version DMI7000; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and a FlowSight imaging cytometer (Amnis Corp., Seattle, WA). Smad2, p-Smad2(S467), Cx43, and α-SMA expression levels were analyzed at the population level with reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction and immunoblotting. Cytofluorimetric and densitometric analyses were performed with LasX software (Leica) and ImageJ freeware (National Institutes of Health), respectively (27–29). Direct interactions among Cx43, Smad2, and β-tubulin in HBFs were estimated using a co-immunoprecipitation approach (28). A detailed description of staining procedures is available in the online supplement.

Functional Studies and Living Cell Microscopy

GJIC was estimated by intercellular calcein transfer assay. Cell proliferation, motility, and viability were analyzed with the Coulter counter, time-lapse videomicroscopy, and the fluorescence microscopy-assisted fluorescein diacetate/ethidium bromide test, respectively, using the Leica DMI6000B epifluorescence system (27, 28, 30). For gene silencing and overexpression, HBFs were transfected with siRNA-A (control), siRNA-Smad2, siRNA Smad2/3 (Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany), MISSION esiRNA GJA1, and pCMVpcDNA3.2-Cx43-siRes vector (Addgene, Cambridge, MA) using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) analyses, the cells were transfected with pmTurquoise2-α-Tubulin and pTRE-TIGHT-Cx43-eYFP (31–33) and analyzed with a Leica DMI6000B system equipped with an external filter wheel CFP/YFP FRET set controlled by FRET SE Wizard software (Leica). Detailed protocols are available in the online supplement.

Results

TGF-β Induces Cx43 Up-Regulation and Myofibroblastic Differentiation in Cx43high AS HBFs

To study Cx43 involvement in myofibroblast differentiation of HBFs, we treated the populations of bronchial fibroblasts derived from patients with asthma (AS HBFs, n = 5) or from donors without asthma (NA HBFs, n = 5) with TGF-β1 for 7 days. TGF-β1 efficiently induced the FMT in AS HBFs. This was demonstrated by more effective formation of prominent α-SMApositive microfilament bundles in TGF-β1–treated asthmatic fibroblasts than in their nonasthmatic counterparts (Figure 1A). AS HBFs showed high basal Cx43 expression levels in the absence of TGF-β1. Immunofluorescence (Figure 1A) and immunoblot studies (Figures 1B and E2A) revealed further up-regulation of Cx43 in AS HBFs in response to TGF-β1 stimulation. Accordingly, analyses of GJIC by intercellular calcein transfer assay demonstrated increased activity of gap junctions in AS HBF populations on TGF-β1 treatment (Figure E3). We also addressed the correlation between Cx43 and α-SMA at the single cell level using imaging cytometry. Single Cx43high AS HBFs showed high α-SMA expression (Figure 1C). In contrast to AS HBFs, NA HBFs displayed low basal Cx43 levels and showed poor susceptibility to TGF-β1–induced FMT as demonstrated by immunofluorescence (Figure 1A), immunoblot (Figure 1B), and imaging cytometry (Figure 1C). These assays demonstrated only slight Cx43 up-regulation after TGF-β1 treatment in NA HBFs (Figures 1A–1C). AS and NA HBF lineages displayed stable Cx43high and Cx43low phenotypes, respectively, over numerous passages in vitro (not shown). Collectively, these data suggest that the high susceptibility of AS HBFs to TGF-β1–induced FMT may be functionally related to high Cx43 expression levels in these cells.

![Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) induces myofibroblastic differentiation and connexin43 (Cx43) up-regulation in Cx43high human bronchial fibroblasts (HBFs) from donors with asthma (AS). (A) AS and HBFs from donors without asthma (NA) were cultured in control conditions (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium [DMEM]/0.1% bovine serum albumin) or in DMEM supplemented with TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) for 7 days, immunostained for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (green), Cx43 (red), and DNA (blue) (right), and the fraction of cells that formed abundant α-SMApositive stress fibers was quantified with fluorescence microscopy (left). Scale bar: 25 μm. (B) HBFs from five AS and five NA donors were cultured in control conditions or in DMEM supplemented with TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) for 7 days and subjected to immunoblot analyses of Cx43 levels (for densitometric quantification of the blots, see Figure E2A). (C) AS and NA cells were cultured as in A and immunostained against Cx43/α-SMA. The expression pattern of both proteins was analyzed with imaging cytometry. Dot plots comprise 50,000 events gated according to sum of squared difference properties. Quantitative data were obtained with IDEAS software. Bars represent mean values (±SEM). P values were calculated with Student's t test (versus TGF-β+), *P ≤ 0.05. All results are representative of three independent experiments. Note that the predilection of HBFs to TGF-β1–induced fibroblast–myofibroblast transition is correlated with Cx43 levels in these cells and with the magnitude of Cx43 up-regulation.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ajrcmb/57/1/10.1165_rcmb.2015-0255OC/1/m_ajrcmb_57_1_100_f1.jpeg?Expires=1773995569&Signature=CclXmwIxHm~pIV34NlZn5rLYurqZNKqmX0bpzjv9NkxJmFbdyFAwkUDLZFx24aPv5SFmgsRe~wr2r6hnSP1bN~OhlBKDB7v0Wzz8dfOv7OFdMKUhncAMPHEtdORrNrcUl7XJH7e4-LvtC66XrL4ChaGyUZnju~xG5JmPi6syeE7E1q8h-unCz76AfPUy8tqUO8OtRc33Mszfv4WLKUU2ir9CTfRJIW9LEhUgNqsSnvR4VPIpS12lufDIoP7lLshnLHLiCMJfGTGoQWnAXPuUds~9jvkq4w-02mVY5DtU0FDp0gZwpuh-ejpBXQmkadQHor1PJsDG2Ig4pIX4VPSGnQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Figure 1.

Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) induces myofibroblastic differentiation and connexin43 (Cx43) up-regulation in Cx43high human bronchial fibroblasts (HBFs) from donors with asthma (AS). (A) AS and HBFs from donors without asthma (NA) were cultured in control conditions (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium [DMEM]/0.1% bovine serum albumin) or in DMEM supplemented with TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) for 7 days, immunostained for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (green), Cx43 (red), and DNA (blue) (right), and the fraction of cells that formed abundant α-SMApositive stress fibers was quantified with fluorescence microscopy (left). Scale bar: 25 μm. (B) HBFs from five AS and five NA donors were cultured in control conditions or in DMEM supplemented with TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) for 7 days and subjected to immunoblot analyses of Cx43 levels (for densitometric quantification of the blots, see Figure E2A). (C) AS and NA cells were cultured as in A and immunostained against Cx43/α-SMA. The expression pattern of both proteins was analyzed with imaging cytometry. Dot plots comprise 50,000 events gated according to sum of squared difference properties. Quantitative data were obtained with IDEAS software. Bars represent mean values (±SEM). P values were calculated with Student's t test (versus TGF-β+), *P ≤ 0.05. All results are representative of three independent experiments. Note that the predilection of HBFs to TGF-β1–induced fibroblast–myofibroblast transition is correlated with Cx43 levels in these cells and with the magnitude of Cx43 up-regulation.

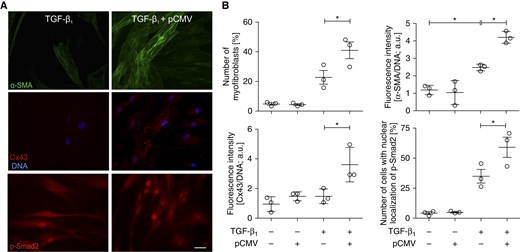

Ectopic Cx43 Expression Increases the Susceptibility of NA HBFs to TGF-β1–Induced FMT

Next, we addressed whether Cx43 overexpression could enhance myofibroblastic differentiation of NA HBFs. Indeed, ectopic Cx43 expression (Figure E4A) increased the susceptibility of Cx43low NA HBFs to TGF-β1–induced FMT (Figure 2). This effect was illustrated by prominent α-SMA up-regulation and by increased numbers of Cx43-transfected NA HBFs showing α-SMA incorporation into microfilament bundles (Figures 2A and 2B). Concomitantly, a considerably more prominent Cx43 up-regulation was observed in Cx43-transfected NA HBFs than in control cells after TGF-β1 treatment. Analysis of TGF-β–dependent Smad pathway activity in control NA HBFs showed its low responsiveness to TGF-β1 (Figures 2B and E4B). Importantly, Cx43 overexpression significantly increased the number of p-Smad2positive nuclei in TGF-β1–treated NA HBFs. These observations confirm that Cx43 participates in the initiation of TGF-β1–induced FMT in HBFs and point to the involvement of Smad-dependent signaling in this process.

Figure 2.

Cx43 increases the susceptibility of NA HBFs to TGF-β1–induced fibroblast–myofibroblast transition (FMT). (A) NA HBFs were transfected with pCMV-Cx43 vector (see Materials and Methods and Figure E4), treated with TGF-β1 and immunostained for α-SMA, Cx43, and phospho-Smad (p-Smad)2. (B) Relative numbers of cells that formed abundant α-SMApositive stress fibers and Cx43 levels were analyzed 7 days after TGF-β1 administration, whereas p-Smad2positive nuclei were counted 1 hour after TGF-β1 administration. Scale bar: 100 μm. Bars represent the mean values (±SEM). P values calculated with one-way analysis of variance and post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test (versus TGF-β+); *P ≤ 0.05. All results are representative of at least three independent experiments. Note that ectopic Cx43 expression in undifferentiated NA HBFs increased their susceptibility to TGF-β1–induced FMT and Cx43 up-regulation. It also facilitated Smad2 activation after TGF-β1 stimulation. a.u., arbitrary units; pCMV, promoter of cytomegalovirus.

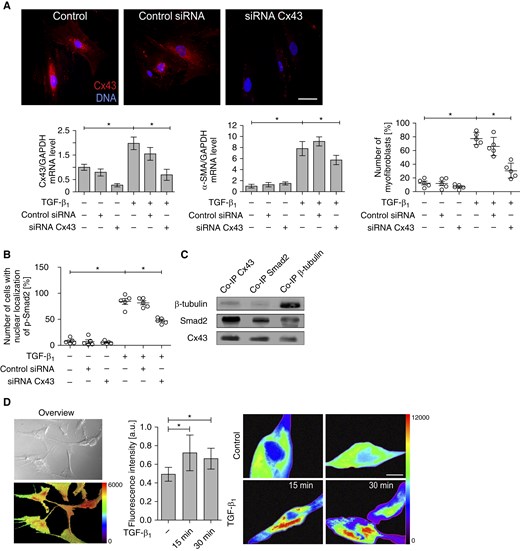

Cx43 Regulates the Susceptibility of AS HBFs to TGF-β1–Induced FMT through Smad2-Dependent Mechanism

To confirm the significance of Cx43 for the initiation of FMT in bronchial fibroblasts, we silenced Cx43 expression in Cx43high AS HBFs using Cx43 siRNA (Figure 3). Partial Cx43 silencing (by roughly 60%) significantly attenuated TGF-β1–induced α-SMA up-regulation in AS HBFs (Figure 3A). It also impaired the formation of α-SMApositive myofibroblasts in AS HBF populations (Figure 3A) and attenuated the nuclear accumulation of p-Smad2 in TGF-β1–treated AS HBFs (Figure 3B). This is illustrated by the reduced number of p-Smad2positive nuclei in TGF-β1–treated AS HBF populations (Figure E5). Cx43 was shown previously to regulate TGF-β1–induced FMT in cardiac fibroblasts through interference with the sequestration of Smad2 molecules on microtubules (17). Therefore, we further analyzed the interactions among Cx43, Smad2, and β-tubulin in AS HBFs. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed the interaction of Cx43 and Smad2 with microtubules, as illustrated by the presence of both proteins in the fraction precipitated with anti–β-tubulin IgG (Figure 3C). Using FRET assay, we demonstrated that the pool of microtubule-bound Cx43 in AS HBFs increases rapidly in response to TGF-β1 (Figure 3D). In conjunction with the increased susceptibility of NA HBFs to the TGF-β1–induced FMT observed after ectopic Cx43 expression (Figure 2), these observations show that TGF-β1 can induce Cx43/microtubule interaction. This interaction further attenuates the cytoplasmic sequestration of Smad2 and facilitates its activation in a GJIC-independent manner.

Figure 3.

Cx43 participates in the initiation of FMT in AS HBFs in a gap junctional intercellular coupling (GJIC)–independent manner. (A) AS HBFs were transfected with Cx43 small interfering RNA (siRNA) (or control siRNA; see Materials and Methods). Cx43 expression was analyzed at the mRNA level with quantitative RT-PCR. The long-term effects of Cx43 silencing on α-SMA–encoding mRNA levels and FMT in AS HBFs populations were estimated with quantitative RT-PCR and fluorescence microscopy, respectively, after 7 days of TGF-β1 treatment. Scale bar: 25 µm. (B) AS HBFs were transfected with Cx43 siRNA, subjected to TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml), and immunostained against p-Smad2 after 1 hour of TGF-β1 treatment. The fraction of p-Smad2positive nuclei was estimated with fluorescence microscopy (Figure E5). (C) Clarified lysates of AS HBFs were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Cx43, anti-Smad2, and anti–β-tubulin antibody and then analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (D) pmTurquoise2-α-tubulin and eYFP-Cx43 were expressed in HBFs. Scale bar: 100 µm (left). After 48 hours, TGF-β1 was added to the cells at a concentration of 5 ng/ml, and Förster Resonance Energy Transfer signal was registered 15 and 30 minutes afterward (middle). The pseudocolor scale was used to indicate Förster Resonance Energy Transfer signal intensity within the Region of Interest (right; see Materials and Methods). Scale bar: 25 µm. P values calculated with one-way analysis of variance and post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test (versus TGF-β+); *P ≤ 0.05. Note that transient Cx43 silencing results in the attenuation of TGF-β1–induced FMT of AS HBFs and decreases the magnitude of TGF-β1–induced Smad2 activation, whereas TGF-β1 induces Cx43/microtubule interactions in AS HBFs. Co-IP, co-immunoprecipitation.

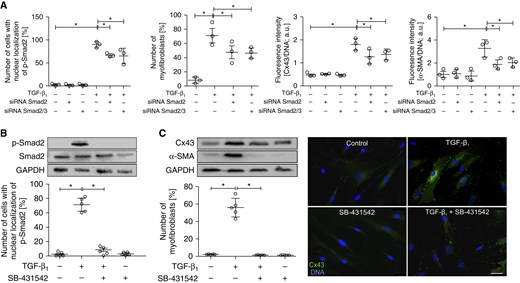

Inhibition of the TGF-β/Smad Axis Attenuates Cx43 Up-Regulation and FMT in AS HBFs

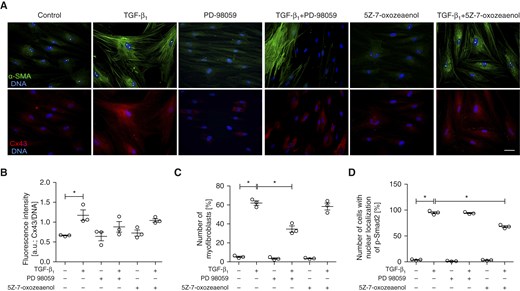

Our data indicate that a certain amount of Cx43 is necessary for the initiation of TGF-β1–induced FMT in bronchial fibroblasts, whereas progressive Cx43 up-regulation during FMT may further amplify FMT signaling. To identify the mechanisms responsible for TGF-β1–dependent Cx43 up-regulation in AS HBFs, we targeted the canonical TGF-β signaling pathway with Smad2 siRNA or with the inhibitor of TGF-β type I receptor (SB-431542). Smad2 silencing reduced the numbers of p-Smad2positive nuclei and the formation of α-SMApositive myofibroblasts in TGF-β1–treated AS HBFs (Figures 4A and E6). Notably, the attenuating effect of Smad2 silencing on TGF-β1–dependent Cx43 up-regulation was observed in AS HBFs. We also applied siRNA specific for both Smad2- and Smad3-encoding mRNA. No additional effect of Smad3 silencing on Smad2 activation, FMT, and Cx43 expression was observed (Figures 4A and E6). Furthermore, SB-431542 almost completely prevented nuclear translocation of p-Smad2 (Figures 4B and E7), myofibroblast formation, and Cx43 up-regulation in TGF-β1–treated AS HBF populations (Figures 4C and E2B). Instead, the treatment of AS HBFs with TAK1 inhibitor (5Z-7-oxozeaenol) or with the inhibitor of ERK1/2-dependent signaling (PD98059) did not affect TGF-β1–induced Cx43 up-regulation (Figures 5A and 5B). However, we found that treatment with PD98059 slightly affected the number of myofibroblasts in TGF-β1–treated cells (Figure 5C). Furthermore, 5Z-7-oxozeaenol slightly reduced p-Smad2 activation but did not affect myofibroblast formation in TGF-β1–treated AS HBFs (Figures 5C and 5D). Collectively, these data indicate that TGF-β1–induced Cx43 up-regulation and FMT in HBFs is regulated by the TGF-β1/Smad–dependent axis. Cx43 seems to participate in the TGF-β1/Smad–dependent feedback mechanism that controls myofibroblastic differentiation of bronchial fibroblasts.

Figure 4.

Cx43 expression and FMT of AS HBFs is controlled by Smad2. (A) Cells were transfected with Smad2 or Smad2/Smad3 siRNA (Figure E6); subjected to TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml); immunostained for p-Smad2, Cx43, and α-SMA; and analyzed with fluorescence microscopy after 1 hour (p-Smad2; see Figure E6A) or 7 days (Cx43 and α-SMA; see Figure E6B). (B) AS HBFs were cultivated in control conditions or in DMEM supplemented with TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml), in the presence or absence of SB431542 (10 μM). The effect of SB431542 treatment on the levels of p-Smad2 and Smad2 (in relation to GAPDH as a housekeeping protein) and on the relative numbers of p-Smad2positive nuclei was estimated after 1 hour, with immunoblotting and fluorescence microscopy, respectively (see Figure E7). (C) Cells were cultivated as in B for 7 days, and the effect of SB431542 on Cx43 and α-SMA expression and on myofibroblastic differentiation of AS HBFs was analyzed with immunoblotting in relation to GAPDH as a housekeeping protein (for densitometric quantification of the blots, see Figure E2B) and with fluorescence microscopy, respectively. Bars represent the mean values (±SEM). P values were calculated with one-way analysis of variance and post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test (versus TGF-β+); *P ≤ 0.05. Scale bar: 25 μm. All results are representative of at least three independent experiments. Note that the correlation among the number of p-Smad2positive nuclei, Cx43 expression, and the abundance of myofibroblastic fraction in AS HBF populations is accompanied by a lack of Smad2 and Smad3 additive effects on cell sensitivity to TGF-β1.

Figure 5.

ERK1/2- and TAK1-dependent signaling play secondary roles in the regulation of Cx43 expression and FMT in populations of AS HBFs. (A) AS HBFs were cultivated in control conditions or in DMEM supplemented with TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of PD98059 (20 μM) and 5Z-7-oxozeaenol (10 μM). Subsequently, the cells were immunostained for Cx43, α-SMA, p-Smad2, and DNA (blue). (B) Cx43 levels in AS HBFs were quantified with the fluorometric approach. Alternatively, relative numbers of (C) cells that had formed abundant α-SMApositive stress fibers and of (D) p-Smad2positive nuclei were quantified with fluorescence microscopy. Bars represent the mean values (±SEM). P values were calculated with one-way analysis of variance and post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test (versus TGF-β+); *P ≤ 0.05. Scale bar: 25 μm. All results are representative of three independent experiments. Note that ERK1/2 inhibition by PD98059 attenuates FMT and slightly inhibits TGF-β1–induced Cx43 up-regulation in the absence of any effects on Smad2 activation. The inhibition of TAK1 by 5Z-7-oxozeaenol does not affect FMT and Cx43 up-regulation, although it slightly reduces relative numbers of p-Smad2positive nuclei in TGF-β1–treated AS HBFs.

GJIC Inhibition Affects the Phenotype of Differentiated AS HBFs

Reciprocal links between Cx43 function and TGF-β1/Smad–dependent FMT of bronchial fibroblasts prompted us to estimate the involvement of GJIC in the initiation of FMT in AS HBFs. AGA significantly attenuated GJIC in HBF populations (Figure E8A), but did not exert any significant cytotoxic effects on HBFs (Figures E8B–E8E). Importantly, AGA did not affect α-SMA and Cx43 up-regulation in AS HBFs observed after TGF-β1 treatment (Figures 6A and E2C). However, AGA impaired the formation of α-SMApositive microfilament bundles in TGF-β1–treated AS HBF populations (Figure 6A). Consequently, the fraction of the cells that formed α-SMApositive microfilament bundles decreased considerably in AGA-treated populations (Figure E8F), in the absence of AGA effects on the relative numbers of α-SMApositive cells. We did not observe any true additive effects of AGA and Cx43 siRNA on the numbers of α-SMApositive cells or p-Smad2positive nuclei (Figure 6B). These results confirm that GJIC does not participate in the initiation of FMT in AS HBF populations. They also suggest that GJIC may stabilize the myofibroblastic phenotype of HBFs.

![Cx43 influences the functional status of α-SMA in differentiated AS HBFs. (A) AS HBFs were cultured in the presence or the absence of TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml)/18α-glycyrrhetinic acid (AGA) (30 μM) for 7 days. α-SMA/Cx43 expression levels and intracellular localization of α-SMA were estimated by immunoblotting (for densitometric quantification of the blots, see Figure E2C) and immunofluorescence, respectively. Histograms show the intensities of α-SMA–specific immunofluorescence signals along the indicated scan line. (B) AS HBFs were transfected with Cx43 siRNA (or control siRNA; see Materials and Methods). Relative numbers of α-SMApositive cells (after 7 days of TGF-β1 [5 ng/ml] treatment) and of p-Smad2positive nuclei (after 1 hour of TGF-β1 [5 ng/ml] treatment) were quantified by fluorescence microscopy in the presence or absence of AGA. (C) AS HBFs were treated with TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) for 7 days. Then they were transfected with Cx43 siRNA or treated with AGA (30 μM), cultivated for the next 7 days in the absence of TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml), and immunostained for α-SMA (left). Relative numbers of cells with abundant α-SMApositive stress fibers (middle) and α-SMA expression levels (right) were quantified with fluorescence microscopy. Bars represent the mean values (±SEM). P values calculated with one-way analysis of variance and post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test (versus TGF-β+); *P ≤ 0.05. Scale bar: 25 μm. All results are representative of at least three independent experiments. Note that GJIC inhibition has no effect on TGF-β1–induced p-Smad2 activation, FMT, and Cx43 up-regulation in AS HBFs but does affect the functional status of α-SMA in differentiated cells.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ajrcmb/57/1/10.1165_rcmb.2015-0255OC/1/m_ajrcmb_57_1_100_f6.jpeg?Expires=1773995570&Signature=bC365TfjsEdNrajEnDRffQdwBrtTbQBtEGbmCbKeI42iYsxkONsssmq5XtusibzdiEJe4zeOoEf-GpDWYOX6gySq6hAJmPz0RrcYRlYo-gHP6idorTWUDJ0TbGfSbNp3fs15U61a09H9sKQrl9uZ5X76oljm8773x37THBtsSgietNFOtelKrQeXM2hUf9PmqxhxUHcSaG-Qx2saxyEUudQM3VEcXVuLIgDX9xgruRtzj~~4I9HIIA18BYWEPaXD-ZHzPp1-QghSBx146ZAYSiuZmiiMK7vaizbE5PBVfrnZDiqSlryWypoW~QS1pJejbu~PUx-Zz5vdaD3IsD7VTQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Figure 6.

Cx43 influences the functional status of α-SMA in differentiated AS HBFs. (A) AS HBFs were cultured in the presence or the absence of TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml)/18α-glycyrrhetinic acid (AGA) (30 μM) for 7 days. α-SMA/Cx43 expression levels and intracellular localization of α-SMA were estimated by immunoblotting (for densitometric quantification of the blots, see Figure E2C) and immunofluorescence, respectively. Histograms show the intensities of α-SMA–specific immunofluorescence signals along the indicated scan line. (B) AS HBFs were transfected with Cx43 siRNA (or control siRNA; see Materials and Methods). Relative numbers of α-SMApositive cells (after 7 days of TGF-β1 [5 ng/ml] treatment) and of p-Smad2positive nuclei (after 1 hour of TGF-β1 [5 ng/ml] treatment) were quantified by fluorescence microscopy in the presence or absence of AGA. (C) AS HBFs were treated with TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) for 7 days. Then they were transfected with Cx43 siRNA or treated with AGA (30 μM), cultivated for the next 7 days in the absence of TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml), and immunostained for α-SMA (left). Relative numbers of cells with abundant α-SMApositive stress fibers (middle) and α-SMA expression levels (right) were quantified with fluorescence microscopy. Bars represent the mean values (±SEM). P values calculated with one-way analysis of variance and post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test (versus TGF-β+); *P ≤ 0.05. Scale bar: 25 μm. All results are representative of at least three independent experiments. Note that GJIC inhibition has no effect on TGF-β1–induced p-Smad2 activation, FMT, and Cx43 up-regulation in AS HBFs but does affect the functional status of α-SMA in differentiated cells.

In the next experiments, we analyzed the effects of Cx43 manipulation on the phenotype of differentiated AS HBFs. For this purpose, TGF-β1–induced myofibroblastic differentiation of AS HBFs was followed by the silencing of Cx43 expression or by the inhibition of GJIC by AGA in the absence of TGF-β1 (Figures 6C and E1). TGF-β1 depletion did not significantly affect α-SMA expression in differentiated HBFs and did not reduce the numbers of α-SMApositive myofibroblasts. Cx43 silencing by siRNA considerably disturbed the phenotype of differentiated AS HBFs as illustrated by attenuated α-SMA expression levels and reduced fraction of α-SMApositive cells. A slightly less pronounced effect of AGA on both these parameters was observed (Figure 6C). These observations confirm the significance of Cx43 up-regulation in the progression of FMT in HBFs. They also illustrate the involvement of Cx43 and GJIC in the maintenance of the HBF myofibroblastic phenotype.

Discussion

Connexins and gap junctions participate in intercellular cooperation within tissue compartments. The involvement of connexins in the etiopathology of chronic diseases has been considered predominantly in terms of their tissue-specific deficiency and/or dysfunction. For example, deficient expression or function of Cx26, Cx32, Cx37, Cx40, and Cx43 has been implicated in hereditary deafness and neuropathies, infertility, cardiac dysfunctions, and cancer (34–38). Only a few studies have considered the development of diseases as a result of pathologically increased Cx43 levels, which have been implicated in the invasion and extravasation of cancer cells (27, 28, 39). Cx43 up-regulation also accompanies the acquisition of the myofibroblastic phenotype (myofibroblastic differentiation) by aortic (40) and myocardial cells (18). Myofibroblastic differentiation of bronchial fibroblasts is crucial for bronchial fibrosis and asthma progression (41). However, the role of connexins in these processes has not yet been addressed, even though numerous connexins are present in the respiratory system. We used in vitro cultured lineages of AS and NA HBFs to show that high Cx43 levels in bronchial fibroblasts facilitate the development and maintenance of their myofibroblastic phenotype. Our study adds bronchial asthma to the list of chronic diseases whose progression is facilitated by increased intracellular Cx43 levels.

TGF-β1–induced FMT plays a crucial role in the pathologic expansion of myofibroblasts in asthmatic bronchial walls (41, 42). HBFs derived from asthmatic bronchi display a relatively high predisposition for TGF-β1–induced FMT when compared with nonasthmatic HBFs. We have reported previously that the mechanical equilibrium of actin cytoskeleton, Wnt-signaling activity, and the functional status of N-cadherin participate in this fundamental phenotypic difference between NA and AS HBFs (10, 22–24, 29). Our current data show considerably higher levels of Cx43 in AS HBFs than in their NA counterparts. The augmentation of the fibrogenic potential of Cx43low NA HBFs was seen on ectopic Cx43 expression, whereas transient Cx43 silencing impaired TGF-β1–induced FMT in Cx43high AS HBFs. These observations show that certain threshold levels of Cx43 are necessary for the initiation of TGF-β–dependent myofibroblastic differentiation of bronchial fibroblasts. The interplay between Cx43- and TGF-β1/Smad–dependent pathways in cardiac and aortic smooth muscle cells has been addressed previously (18, 40, 43). In this study, ectopic Cx43 expression increased the magnitude of Smad2 activation in NA HBFs in response to TGF-β1, whereas impaired Smad2 activation was observed in TGF-β1–treated AS HBFs on Cx43 silencing. These data confirm the functional links between Cx43 and TGF-β1/Smad signaling in bronchial fibroblasts. Furthermore, considerable amounts of Smad2 were bound to microtubules in AS HBFs. TGF-β1 induced the interaction between Cx43 and microtubules in these cells. We postulate that Cx43 can release the microtubule-sequestrated Smad2 molecules through GJIC-independent competition for their binding sites on microtubules. Conceivably, this event may facilitate the nuclear accumulation of Smad2, leading to up-regulation of Smad-responsive genes (including α-SMA and Cx43) in TGF-β1–treated cells. These interactions account for the GJIC-independent involvement of Cx43 in the activation of the TGF-β/Smad–dependent signaling cascade and in the initiation of FMT in HBF populations.

Notably, Cx43 expression in differentiating HBFs is under the control of the TGF-β1/Smad–dependent pathway, as demonstrated by the sensitivity of Cx43 up-regulation to Smad2 inhibition. Reciprocal links between Cx43 and the Smad-dependent cascade illustrate the biological significance of Cx43 up-regulation during TGF-β1–induced myofibroblastic differentiation of bronchial fibroblasts. Because of the role of Cx43 as a cofactor of the Smad-dependent pathway, Cx43 up-regulation apparently helps amplify TGF-β1/Smad signaling activity in a GJIC-independent manner (Figure E9). A positive feedback loop between Cx43 expression and TGF-β1/Smad–dependent signaling can facilitate the multistep myofibroblastic differentiation of asthmatic fibroblasts. A lack of additional effects of Smad3 silencing on FMT and on Cx43 expression in AS HBFs indicates that Smad2 function is crucial for this feedback mechanism. However, Smad3 may still participate in the Cx43/TGF-β1/Smad signaling axis. A corresponding axis that couples the Cx43high phenotype with cellular predilection for FMT and epithelial–mesenchymal transition has been implicated previously in myocardial fibrosis and prostate cancer (17, 18, 28). Conceivably, ERK1/2- and TAK1/p38-dependent cascades play a secondary role in the myofibroblastic differentiation of AS HBFs. However, Smad3, ERK1/2, and TAK1/p38 functions can still affect the cooperative TGF-β/Cx43 signaling. Further studies are necessary to fully elucidate the complex Cx43 functions in the expansion of myofibroblasts in asthmatic bronchi.

In our study, GJIC inhibition had no effect on TGF-β1–induced α-SMA up-regulation or Smad2 activation in AS HBFs. These data indicate that GJIC is not necessary for the initiation of HBF myofibroblastic differentiation. Instead, disturbed α-SMA incorporation into stress fibers was observed on the inhibition of GJIC in TGF-β1–treated HBF populations. α-SMApositive stress fibers are largely responsible for the contractile phenotype of myofibroblasts (8). Their structural integrity is regulated by the intracellular exchange of contractile stimuli (such as Ca++ waves) via gap junctional channels (29, 44–46). GJIC-mediated “bystander effects” (44) may regulate the functional status and/or the turnover of α-SMA in myofibroblasts. Our data indicate that GJIC-mediated bystander effects are involved in the acquisition of the contractile phenotype by differentiating HBFs. Furthermore, enhanced Cx43-dependent GJIC can increase the longevity of bronchial myofibroblasts. This notion is supported by down-regulation of α-SMA expression, which was observed in differentiated AS HBFs on Cx43 silencing or on the inhibition of GJIC. It remains to be elucidated whether GJIC helps sustain residual Smad2 activation levels in the absence of TGF-β1. It is also premature to draw a conclusion about the full reversal of the myofibroblastic phenotype of HBFs on GJIC inhibition (47). However, these observations show that GJIC might participate in the pathologic prolongation of myofibroblast activity during asthma progression (9, 41).

Collectively, we demonstrate the involvement of Cx43 in fundamental phenotypic differences between NA and AS HBFs. Further in vivo screening studies are definitely needed to address the correlation between Cx43 levels in bronchial walls and asthma severity. However, our in vitro data also suggest an increased abundance of Cx43high fibroblastic lineages in asthmatic bronchi. Selective expansion of preexisting progenitors, the recruitment of fibrogenic Cx43high progenitors from the circulation (48), and/or the progressive reprogramming of Cx43low HBFs toward the profibrogenic (Cx43high) phenotype may account for this phenomenon. The Cx43high phenotype facilitates the induction of pathological profibrotic shifts in bronchial fibroblasts exposed to the TGF-β1–rich microenvironment of asthmatic bronchi, whereas the Cx43low phenotype of HBFs could counteract these events. Connexins and connexons interact with a myriad of protein assemblies within and outside the “gap junction proteome” (15). Our study adds cooperation with the TGF-β1/Smad–dependent pathway during the myofibroblastic differentiation of HBFs to the long list of “noncanonical” Cx43 functions (15, 19). Given the postulated significance of TGF-β1/Smad–dependent FMT in bronchial fibrosis, these observations identify Cx43 as a new player in the feedback mechanisms that regulate the expansion of myofibroblasts in asthmatic bronchi and as a key factor in asthma progression. Further studies on the origin of Cx43high bronchial fibroblasts and on the role of Cx43 in HBF responsiveness to local inflammation in vivo will help introduce Cx43 targeting into antiasthmatic regimens. However, our results provide a mechanistic rationale for evaluating the clinical benefits of Cx43 targeting in asthma treatment, either alone or in combination with other therapies.

Footnotes

This work was supported by funds granted to the Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology of Jagiellonian University to further “The Development of Young Scientists and Doctoral Students” 2014/2015 (BMN 3/2014 [M.P.]) and by the Polish National Science Centre (Grants 2015/17/B/NZ3/01040 and 2011/01/B/NZ3/00004 [J.C.], and 2015/17/B/NZ3/02248 [M.M.]). The Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology of Jagiellonian University is a beneficiary of structural funds from the European Union (Grants UDA-POIG.01.03.01-14-036/09-00, POIG.02.01.00-12-064/08, POIG 01.02-00-109/99, and POIG.02.01.00-12-167/08) and a partner in the Leading National Research Center (KNOW) supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Author Contributions: M. Paw: study design, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation; I.B.: data collection and data analysis; D.W.: data collection and data analysis; D.R.: data collection and data analysis; K.P.: data collection; K.K.: data collection and data analysis; K.A.W.-P.: data collection; M. Pierzchalska: study design; Z.M.: study design; M.S.: study design; P.B.: data analysis and manuscript preparation; M.M.: study conception and data analysis; J.C.: study conception and design, data analysis, and final manuscript preparation. All authors participated in the initial drafting, review, and final approval of the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0255OC on February 28, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Sylwia Bobis-Wozowicz for designing the polymerase chain reaction primers.

References

Al-Muhsen

S

,

Johnson

JR

,

Hamid

Q

.

Remodeling in asthma

.

J Allergy Clin Immunol

2011

;

128

:

451

–

462, quiz 463–464

.

Hinz

B

,

Phan

SH

,

Thannickal

VJ

,

Prunotto

M

,

Desmoulière

A

,

Varga

J

,

De Wever

O

,

Mareel

M

,

Gabbiani

G

.

Recent developments in myofibroblast biology: paradigms for connective tissue remodeling

.

Am J Pathol

2012

;

180

:

1340

–

1355

.

Kania

G

,

Blyszczuk

P

,

Müller-Edenborn

B

,

Eriksson

U

.

Novel therapeutic options in inflammatory cardiomyopathy

.

Swiss Med Wkly

2013

;

143

:

w13841

.

Loeffler

I

,

Wolf

G

.

Transforming growth factor-β and the progression of renal disease

.

Nephrol Dial Transplant

2014

;

29

:

i37

–

i45

.

Falke

LL

,

Gholizadeh

S

,

Goldschmeding

R

,

Kok

RJ

,

Nguyen

TQ

.

Diverse origins of the myofibroblast—implications for kidney fibrosis

.

Nat Rev Nephrol

2015

;

11

:

233

–

244

.

Anandan

C

,

Nurmatov

U

,

van Schayck

OC

,

Sheikh

A

.

Is the prevalence of asthma declining? Systematic review of epidemiological studies

.

Allergy

2010

;

65

:

152

–

167

.

Halwani

R

,

Al-Muhsen

S

,

Al-Jahdali

H

,

Hamid

Q

.

Role of transforming growth factor-β in airway remodeling in asthma

.

Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol

2011

;

44

:

127

–

133

.

Desmoulière

A

,

Chaponnier

C

,

Gabbiani

G

.

Tissue repair, contraction, and the myofibroblast

.

Wound Repair Regen

2005

;

13

:

7

–

12

.

Darby

IA

,

Laverdet

B

,

Bonté

F

,

Desmoulière

A

.

Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in wound healing

.

Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol

2014

;

7

:

301

–

311

.

Michalik

M

,

Pierzchalska

M

,

Włodarczyk

A

,

Wójcik

KA

,

Czyż

J

,

Sanak

M

,

Madeja

Z

.

Transition of asthmatic bronchial fibroblasts to myofibroblasts is inhibited by cell-cell contacts

.

Respir Med

2011

;

105

:

1467

–

1475

.

Agarwal

SK

.

Integrins and cadherins as therapeutic targets in fibrosis

.

Front Pharmacol

2014

;

5

:

131

.

Maeda

S

,

Tsukihara

T

.

Structure of the gap junction channel and its implications for its biological functions

.

Cell Mol Life Sci

2011

;

68

:

1115

–

1129

.

Burra

S

,

Jiang

JX

.

Regulation of cellular function by connexin hemichannels

.

Int J Biochem Mol Biol

2011

;

2

:

119

–

128

.

Zhou

JZ

,

Jiang

JX

.

Gap junction and hemichannel-independent actions of connexins on cell and tissue functions--an update

.

FEBS Lett

2014

;

588

:

1186

–

1192

.

Dbouk

HA

,

Mroue

RM

,

El-Sabban

ME

,

Talhouk

RS

.

Connexins: a myriad of functions extending beyond assembly of gap junction channels

.

Cell Commun Signal

2009

;

7

:

4

.

Mroue

RM

,

El-Sabban

ME

,

Talhouk

RS

.

Connexins and the gap in context

.

Integr Biol

2011

;

3

:

255

–

266

.

Dai

P

,

Nakagami

T

,

Tanaka

H

,

Hitomi

T

,

Takamatsu

T

.

Cx43 mediates TGF-β signaling through competitive Smads binding to microtubules

.

Mol Biol Cell

2007

;

18

:

2264

–

2273

.

Asazuma-Nakamura

Y

,

Dai

P

,

Harada

Y

,

Jiang

Y

,

Hamaoka

K

,

Takamatsu

T

.

Cx43 contributes to TGF-β signaling to regulate differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts

.

Exp Cell Res

2009

;

315

:

1190

–

1199

.

Losa

D

,

Chanson

M

,

Crespin

S

.

Connexins as therapeutic targets in lung disease

.

Expert Opin Ther Targets

2011

;

15

:

989

–

1002

.

Bou Saab

J

,

Losa

D

,

Chanson

M

,

Ruez

R

.

Connexins in respiratory and gastrointestinal mucosal immunity

.

FEBS Lett

2014

;

588

:

1288

–

1296

.

Yao

Y

,

Zeng

QX

,

Deng

XQ

,

Tang

GN

,

Guo

JB

,

Sun

YQ

,

Ru

K

,

Rizzo

AN

,

Shi

JB

,

Fu

QL

.

Connexin 43 upregulation in mouse lungs during ovalbumin-induced asthma

.

PLoS One

2015

;

10

:

e0144106

.

Michalik

M

,

Pierzchalska

M

,

Legutko

A

,

Ura

M

,

Ostaszewska

A

,

Soja

J

,

Sanak

M

.

Asthmatic bronchial fibroblasts demonstrate enhanced potential to differentiate into myofibroblasts in culture

.

Med Sci Monit

2009

;

15

:

BR194

–

BR201

.

Michalik

M

,

Wojcik

KA

,

Jakiela

B

,

Szpak

K

,

Pierzchalska

M

,

Sanak

M

,

Madeja

Z

,

Czyz

J

.

Lithium attenuates TGF-β(1)-induced fibroblasts to myofibroblasts transition in bronchial fibroblasts derived from asthmatic patients

.

J Allergy (Cairo)

2012

;

2012

:

206109

.

Wójcik

K

,

Koczurkiewicz

P

,

Michalik

M

,

Sanak

M

.

Transforming growth factor-β1-induced expression of connective tissue growth factor is enhanced in bronchial fibroblasts derived from asthmatic patients

.

Pol Arch Med Wewn

2012

;

122

:

326

–

332

.

Michalik

M

,

Soczek

E

,

Kosińska

M

,

Rak

M

,

Wójcik

KA

,

Lasota

S

,

Pierzchalska

M

,

Czyż

J

,

Madeja

Z

.

Lovastatin-induced decrease of intracellular cholesterol level attenuates fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition in bronchial fibroblasts derived from asthmatic patients

.

Eur J Pharmacol

2013

;

704

:

23

–

32

.

Wójcik

KA

,

Skoda

M

,

Koczurkiewicz

P

,

Sanak

M

,

Czyż

J

,

Michalik

M

.

Apigenin inhibits TGF-β1 induced fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition in human lung fibroblast populations

.

Pharmacol Rep

2013

;

65

:

164

–

172

.

Piwowarczyk

K

,

Wybieralska

E

,

Baran

J

,

Borowczyk

J

,

Rybak

P

,

Kosińska

M

,

Włodarczyk

AJ

,

Michalik

M

,

Siedlar

M

,

Madeja

Z

, et al.

Fenofibrate enhances barrier function of endothelial continuum within the metastatic niche of prostate cancer cells

.

Expert Opin Ther Targets

2015

;

19

:

163

–

176

.

Ryszawy

D

,

Sarna

M

,

Rak

M

,

Szpak

K

,

Kędracka-Krok

S

,

Michalik

M

,

Siedlar

M

,

Zuba-Surma

E

,

Burda

K

,

Korohoda

W

, et al.

Functional links between Snail-1 and Cx43 account for the recruitment of Cx43-positive cells into the invasive front of prostate cancer

.

Carcinogenesis

2014

;

35

:

1920

–

1930

.

Sarna

M

,

Wojcik

KA

,

Hermanowicz

P

,

Wnuk

D

,

Burda

K

,

Sanak

M

,

Czyż

J

,

Michalik

M

.

Undifferentiated bronchial fibroblasts derived from asthmatic patients display higher elastic modulus than their non-asthmatic counterparts

.

PLoS One

2015

;

10

:

e0116840

.

Daniel-Wójcik

A

,

Misztal

K

,

Bechyne

I

,

Sroka

J

,

Miekus

K

,

Madeja

Z

,

Czyz

J

.

Cell motility affects the intensity of gap junctional coupling in prostate carcinoma and melanoma cell populations

.

Int J Oncol

2008

;

33

:

309

–

315

.

Fujita

N

,

Jaye

DL

,

Kajita

M

,

Geigerman

C

,

Moreno

CS

,

Wade

PA

.

MTA3, a Mi-2/NuRD complex subunit, regulates an invasive growth pathway in breast cancer

.

Cell

2003

;

113

:

207

–

219

.

Smyth

JW

,

Hong

TT

,

Gao

D

,

Vogan

JM

,

Jensen

BC

,

Fong

TS

,

Simpson

PC

,

Stainier

DY

,

Chi

NC

,

Shaw

RM

.

Limited forward trafficking of connexin 43 reduces cell-cell coupling in stressed human and mouse myocardium

.

J Clin Invest

2010

;

120

:

266

–

279

.

Goedhart

J

,

von Stetten

D

,

Noirclerc-Savoye

M

,

Lelimousin

M

,

Joosen

L

,

Hink

MA

,

van Weeren

L

,

Gadella

TW

Jr,

Royant

A

.

Structure-guided evolution of cyan fluorescent proteins towards a quantum yield of 93%

.

Nat Commun

2012

;

3

:

751

.

Naus

CC

,

Laird

DW

.

Implications and challenges of connexin connections to cancer

.

Nat Rev Cancer

2010

;

10

:

435

–

441

.

Avshalumova

L

,

Fabrikant

J

,

Koriakos

A

.

Overview of skin diseases linked to connexin gene mutations

.

Int J Dermatol

2014

;

53

:

192

–

205

.

Kleopa

KA

,

Sargiannidou

I

.

Connexins, gap junctions and peripheral neuropathy

.

Neurosci Lett

2015

;

596

:

27

–

32

.

Lambiase

PD

,

Tinker

A

.

Connexins in the heart

.

Cell Tissue Res

2015

;

360

:

675

–

684

.

Winterhager

E

,

Kidder

GM

.

Gap junction connexins in female reproductive organs: implications for women’s reproductive health

.

Hum Reprod Update

2015

;

21

:

340

–

352

.

Czyż

J

,

Szpak

K

,

Madeja

Z

.

The role of connexins in prostate cancer promotion and progression

.

Nat Rev Urol

2012

;

9

:

274

–

282

.

Rama

A

,

Matsushita

T

,

Charolidi

N

,

Rothery

S

,

Dupont

E

,

Severs

NJ

.

Up-regulation of connexin43 correlates with increased synthetic activity and enhanced contractile differentiation in TGF-β-treated human aortic smooth muscle cells

.

Eur J Cell Biol

2006

;

85

:

375

–

386

.

Descalzi

D

,

Folli

C

,

Scordamaglia

F

,

Riccio

AM

,

Gamalero

C

,

Canonica

GW

.

Importance of fibroblasts-myofibroblasts in asthma-induced airway remodeling

.

Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov

2007

;

1

:

237

–

241

.

He

W

,

Dai

C

.

Key fibrogenic signaling

.

Curr Pathobiol Rep

2015

;

3

:

183

–

192

.

Matsushita

T

,

Rama

A

,

Charolidi

N

,

Dupont

E

,

Severs

NJ

.

Relationship of connexin43 expression to phenotypic modulation in cultured human aortic smooth muscle cells

.

Eur J Cell Biol

2007

;

86

:

617

–

628

.

Hall

EJ

.

The bystander effect

.

Health Phys

2003

;

85

:

31

–

35

.

Davis

J

,

Molkentin

JD

.

Myofibroblasts: trust your heart and let fate decide

.

J Mol Cell Cardiol

2014

;

70

:

9

–

18

.

Prunotto

M

,

Bruschi

M

,

Gunning

P

,

Gabbiani

G

,

Weibel

F

,

Ghiggeri

GM

,

Petretto

A

,

Scaloni

A

,

Bonello

T

,

Schevzov

G

, et al.

Stable incorporation of α-smooth muscle actin into stress fibers is dependent on specific tropomyosin isoforms

.

Cytoskeleton

2015

;

72

:

257

–

267

.

Yang

X

,

Chen

B

,

Liu

T

,

Chen

X

.

Reversal of myofibroblast differentiation: a review

.

Eur J Pharmacol

2014

;

734

:

83

–

90

.

Wang

CH

,

Punde

TH

,

Huang

CD

,

Chou

PC

,

Huang

TT

,

Wu

WH

,

Liu

CH

,

Chung

KF

,

Kuo

HP

.

Fibrocyte trafficking in patients with chronic obstructive asthma and during an acute asthma exacerbation

.

J Allergy Clin Immunol

2015

;

135

:

1154

–

62.e1, 5

.

Copyright © 2017 by the American Thoracic Society