Perspectives on NcRNAs in HBV/cccDNA-driven HCC progression (original) (raw)

Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) integration, the HBx protein (and its mutants), and covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) are critical for HBV replication, packaging, and transmission to new host cells. Although nucleos(t)ide analogs (NAs) are a class of antiviral drugs that effectively suppress HBV replication, they do not eliminate cccDNA. This persistent cccDNA, often referred to as an “invisible bullet”, plays a pivotal role not only in the horizontal transmission of HBV but also within the context of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Growing evidence reveals that noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) are deeply involved in cancer progression, as well as the HBV life cycle and related pathogenesis, including liver inflammation, fibrosis, and HCC. This involvement occurs through various mechanisms, as ncRNAs regulate gene transcription, act as miRNA sponges, modulate signaling pathways, and influence downstream effects. These functions depend on the proper formation of RNA structures, which are critical for maintaining the biological activity of ncRNAs. The structure of RNAs appears to play a pivotal role in their functional capacity. Moreover, both ncRNAs and viral nucleotides contribute to G-quadruplex structure formation, which is essential for the HBV life cycle and cancer progression. In this review, we provide an updated overview of the mechanisms by which key ncRNAs mediate HBV/cccDNA actions in HCC progression and focus on their roles in gene expression and structural formation/modification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among the various types of liver cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common types worldwide and is also associated with high mortality [1]. Hepatitis virus infection, metabolic syndrome, and aflatoxin exposure are the major risk factors for HCC [2]. Liver cancer develops centrally through the sequence of inflammation → fibrosis → cirrhosis → HCC. Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), which cannot be translated into proteins, act as crucial regulators of multiple pathways, such as apoptosis, cell proliferation, cell motility, metabolism, drug resistance, tumorigenesis, and metastasis [3].

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a double-stranded DNA virus that belongs to the family Hepadnaviridae [4]. Liver infection can lead to acute and chronic liver diseases. Indeed, HBV is known to be transmitted through contact with infected blood and vertically from mother to child at delivery [5]. Patients with chronic HBV infection have a considerably increased risk of cirrhosis and liver failure/disease leading to progression to HCC. The Taiwanese government initiated an HBV vaccination program in 1984 for newborns and older children/adults. As a result, epidemiological studies in Taiwan have shown a dramatic decrease in the frequency of HBV carriers and a decrease in the incidence of HCC in vaccinated populations [6]. According to large-scale longitudinal HBV cohort studies in Taiwan, this report provides strong evidence supporting a causal role of HBV infection in HCC development and highlights the long-term benefits of vaccination in reducing the incidence of liver cancer. However, even though this policy decreases the prevalence of HBV infection and the incidence rate of HCC, the incidence of HCC in other groups of HBV patients is still close to 1% per year, and these patients will likely eventually develop HCC. Nucleos(t)ide analogs (NAs), a class of antiviral drugs, are implemented as a treatment for HBV patients to avoid such consequences. This drug class includes well-established antiviral therapies such as lamivudine, adefovir dipivoxil, entecavir, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and tenofovir alafenamide. These are potent viral suppressors that function using an inhibitory mechanism that targets the HBV DNA polymerase to block the synthesis of viral DNA [7].

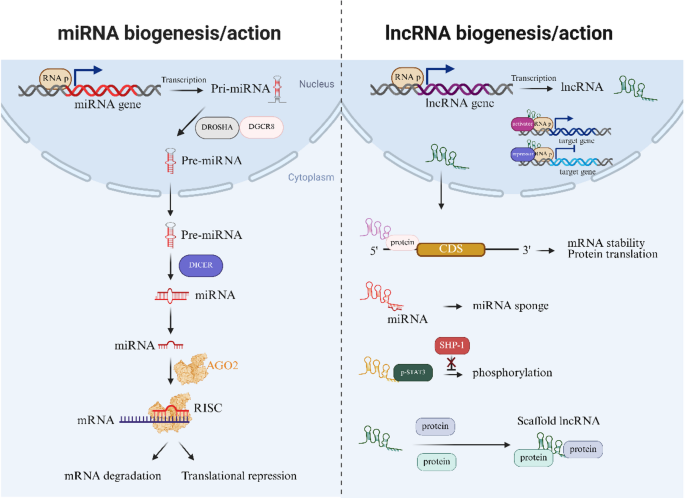

NcRNAs are broadly classified into microRNAs (miRNAs) and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) according to sequence length, with lncRNAs exceeding 200 nucleotides. Research on miRNAs was conducted prior to that on lncRNAs for historical reasons. miRNAs generally control the expression of genes by interacting with the target gene, most often at the 3’UTR, which results in degradation of the mRNA or inhibition of translation (Fig. 1). On the contrary, lncRNAs control genes at various stages, such as the transcriptional, posttranscriptional, translational, and posttranslational stages, via interactions with DNA, RNA and proteins [8, 9] (Fig. 1). In addition, all classes of ncRNAs are now well-known mediators of host-pathogen interactions, viral infections and etiological drivers of disease and cancer [10,11,12].

Fig. 1

Schematic illustration of miRNA and lncRNA biogenesis and their functional roles in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Inside the nucleus, miRNA is transcribed into pri-miRNA from DNA by RNA polymerase (RNA p), which is then processed into pre-miRNA by the DROSHA-DGCR8 complex. Pre-miRNA is imported into the cytoplasm, where it undergoes further processing through Dicer, leading to the production of mature miRNA. After processing, the mature miRNA becomes associated with Argonaute 2 (AGO2) to form the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which binds to complementary mRNAs to mediate mRNA degradation or translational inhibition. Like mRNAs, lncRNAs are also transcribed by RNA polymerase and can regulate gene expression by different means: (1) Through interactions with specific regions of mRNAs, lncRNAs alter mRNA stability and affect mRNA translation. (2) Functioning as miRNA sponges that inhibit miRNA function. (3) Regulating processes such as phosphorylation (e.g., phosphorylation of p-STAT3) by disrupting phosphatase SHP-1-mediated dephosphorylation. (4) Acting as scaffolds to facilitate molecular interactions. Created with BioRender.com

While some prevention or reduction interventions for HCC development have been established, each virus leads to liver cancer through different mechanisms, and thus liver cancer development is a complex process. One such example is HBV-derived covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), which plays a central role in this process. cccDNA drives HBV-related gene expression and HBV replication, and as it cannot currently be eliminated, it serves as the main mediator of HBV persistence. These findings emphasize the critical need to understand the molecular processes that drive the oncogenic effects of cccDNA in HCC. In this review, we summarize the relevant mechanisms of viruses, HBV-derived cccDNA, ncRNAs and their interactions in HBV/cccDNA-mediated liver cancer.

The role of HBV in hepatocarcinogenesis

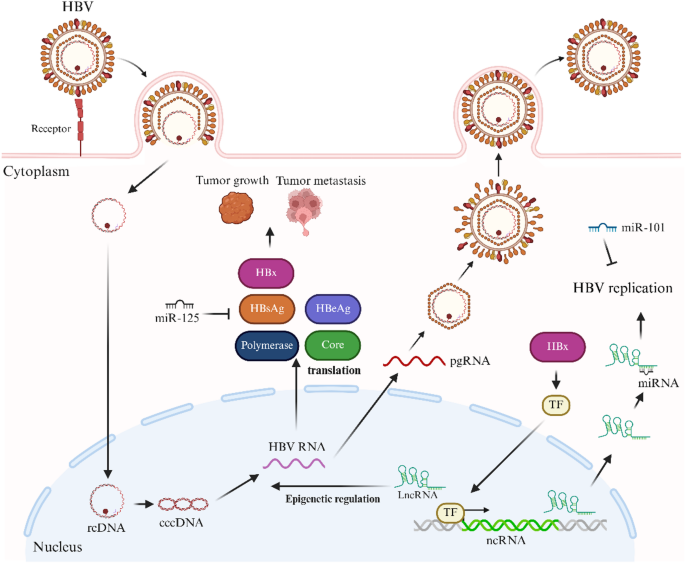

HBV integration, the HBx protein (and its mutants), and cccDNA are core drivers of the oncogenic pathways that lead to HCC (Fig. 2). The following section describes those actions in HCC progression.

Fig. 2

Schematic diagram of the HBV life cycle and the functions of ncRNAs in HBV replication. HBV infects host cells and converts relaxed circular DNA (rcDNA) into cccDNA in the nucleus. As a transcriptional template, cccDNA produces pgRNA. In the cytoplasm, these RNAs are translated into HBV proteins, including HBV polymerase, core protein (core), HBsAg, HBeAg and HBx proteins. HBV particles are then assembled and released from the cell. In contrast, HBx affects downstream target gene expression. Different ncRNAs facilitate the control of HBV replication via different mechanisms; for example, HBV replication is inhibited by miRNAs such as miR-125 and miR-101. NcRNAs regulate the epigenetic state of cccDNA in the nucleus. NcRNAs also regulate transcription factors (TFs), which in turn modulate the expression of viral genes and replication. This figure depicts the balancing effect of HBV replication and host ncRNA-mediated regulation. Created with BioRender.com

HBV integration

A key mechanism of HBV-induced oncogenesis is the integration of HBV DNA into hepatocyte DNA, which disrupts gene regulation and drives genomic instability, promoting liver tumorigenesis [4, 13].

HBx protein and its mutants

HBx modulates cellular homeostasis through alterations in gene expression and activation of tumorigenic pathways [14]. This dysregulation affects host transcription and genes involved in the cell cycle, apoptosis, genomic instability, metabolism, and the immune response. Additionally, HBx activates oncogenic pathways such as the Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/AKT, and NF-κB pathways, which are crucial for tumor initiation and progression [15,16,17]. Mutant HBx variants often exhibit increased oncogenic activity, which promotes HCC progression [18, 19]. Both HBx and its mutants act as molecular drivers and serve as important prognostic and therapeutic biomarkers.

CccDNA: a key player in HBV-mediated HCC

cccDNA, like an invisible bullet, plays a key role not only in the horizontal transmission of HBV but also in HCC progression [20]. As a stable transcriptional template, cccDNA sustains HBV replication and chronic infection in hepatocytes. Its resistance to antiviral therapies makes it a key driver of persistent infection and liver cancer progression. cccDNA promotes oncogenesis by producing viral proteins such as HBsAg, HBx, and core proteins [21]. Since cccDNA itself is not integrated into the host genome, HBV genome replication mediated by cccDNA further causes HBV DNA integration events. cccDNA interacts with the host’s epigenetic machinery and influences chromatin structure and transcriptional activity [22]. These epigenetic modifications regulate both viral and host gene expression, enhancing the oncogenic potential of chronic HBV infection. Additionally, cccDNA sustains HBV persistence and triggers immune-mediated liver inflammation and fibrosis. This establishes a procarcinogenic microenvironment through oxidative stress and cytokine production, which promotes the progression from chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis and ultimately to HCC.

NcRNAs and hbv/cccdna

Accumulating evidence indicates that ncRNAs are critically involved in the life cycle of HBV and its related pathogenesis, including liver inflammation, liver fibrosis, and HCC. NcRNAs regulate HBV replication and expression by modulating viral RNA, the immune response and host cellular pathways [23]. However, the major obstacle to HBV therapy is the persistence of HBV-derived cccDNA in host cells. The ncRNA-HBV interplay may lead to novel potential therapeutic targets for HBV-associated disorders. In this section, several notable interactions between ncRNAs (miRNAs and lncRNAs) and HBV in HCC are introduced and are shown in Fig. 2.

Interplay between MiRNAs and hbv/cccdna in HCC

miR-122 and HBV/HCC

A liver-specific miRNA associated with cellular metabolism, cirrhosis and HCC progression is miR-122 [24]. MiR-122 knockdown results in the induction of HBV, whereas the overexpression of miR-122 results in the opposite effects [25, 26]. This effect is mediated by cyclin G1, a direct target gene of miR-122 that also directly interacts with HBV polymerase and core proteins. Moreover, overexpression of the RNA-editing enzyme adenosine deaminase acting on RNA 1 (ADAR1) was shown to reduce HBV DNA replication in HepG2.2.15 cells following palmitic acid treatment [27]. This effect was mediated through miR-122. Furthermore, the expression levels of both ADAR1 and miR-122 were significantly lower in chronic HBV patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) than in those with chronic HBV infection alone. Another study revealed that HBx overexpression in HepG2 and Huh7 cells markedly inhibited miR-122 expression via its interaction with peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) [28]. Drug resistance is a crucial phenomenon in cancer progression and is recognized as one of the hallmarks of cancer [29]. Elevated miR-122 expression or depletion of cyclin G1 in HepG2 cells with wild-type p53 was shown to inhibit cell proliferation and invasion and to enhance doxorubicin sensitivity by promoting p53 activity [30]. Notably, the inhibition of miR-122 in Huh7 cells that carry mutant p53 still suppresses cell apoptosis upon doxorubicin treatment. These findings suggest that miR-122 enhances doxorubicin sensitivity in liver cancer cells through both p53-dependent and p53-independent pathways. Another report noted that miR-122 is downregulated in HCC cells (HpeG2, Bel-7402, SMMC-7721 and Huh7) compared with the normal liver cell line WRL-68 [31]. Functionally, elevated miR-122 expression induces apoptosis and sensitizes hepatoma cell lines (Bel-7402 and SMMC-7721) to oxaliplatin by suppressing the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Furthermore, β-catenin was found to directly bind to the promoter region of the MDR1 gene. These effects are reversed upon miR-122 overexpression. A previous study demonstrated that miR-122 is downregulated in HCC specimens [32]. A 3′UTR reporter assay and western blot analysis revealed that TLR4 is a target gene of miR-122. Ectopic expression of miR-122 in liver cancer cell lines (Hep3B and MHCC97H) reduces cell growth and enhances apoptosis via the repression of TLR4. Moreover, activation of the PI3K, AKT, and NF-κB signaling cascades was shown to be reduced by miR-122. These observations support the role of miR-122 as a tumor-suppressive miRNA that functions in HCC progression through the modulation of distinct molecules and pathways, which suggests that it is a promising therapeutic target in HCC.

miR-125a and HBV/HCC

Ten years ago, miRanda-based bioinformatics analysis was implemented based on the prediction of a putative interaction between miR-125a-5p and the HBV genome [33]. This finding was confirmed using a luciferase reporter assay, which revealed that the region from nucleotides 3037 to 3065 in the HBV genome is the target site for miR-125a-5p. Patients with high HBV expression also exhibit upregulation of miR-125a [34]. HBx overexpression increases miR-125a expression in liver cancer cell lines (HepG2 and Huh7 cell lines). Induction of this miRNA leads to impaired HBV surface antigen expression, resulting in the inhibition of HBV replication. These findings suggest that the interaction of HBV, HBx and miR-125a forms a self-inhibitory feedback loop. In one study, the overexpression of miR-125a-5p in HepG2.2.15 and HepG3X cells inhibited cell growth and induced apoptosis [35]. ErbB3, a target gene of miR-125a-5p, was identified by 3’UTR luciferase assays, qRT-PCR analysis and western blotting. The results of rescue assays indicated that miR-125a-5p regulates cellular functions through ErbB3. On the contrary, miR-125a-5p expression was found to be lower in HCC tissues than in normal tissues in a small-scale study of HBV-HCC. Collectively, these findings indicate that this miRNA acts as a tumor suppressor that is negatively regulated by HBx. Further validation is needed because miR-125a-5p expression levels are inconsistent across different cohorts.

miR-101 and HBV/HCC

MiR-101 is involved in the progression of several cancers, including HCC [36]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that miR-101 overexpression in liver cancer cell lines, including HepG2.2.15, HepG2, and SMMC-7721 cells, suppresses HBV replication and expression, inhibits cell growth and migration, and promotes apoptosis by targeting genes such as FOXO1, Rab1b, and Rab5a [37,38,39]. More recently, HBV was shown to inhibit miR-101 expression at the transcriptional level. Importantly, circulating miR-101 is present in the serum of HCC patients and has been proposed as a potential biomarker for HBV-associated HCC [40, 41]. Recently, a group demonstrated that PDZ domain containing 1 (PDZK1) is overexpressed in HCC tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues [42]. Ectopic expression of PDZK1 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasiveness of Huh7 cells through activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Moreover, PDZK1 was identified as a direct target of miR-101. Notably, miR-101 overexpression reverses the oncogenic effects mediated by PDZK1. In addition, miR-101 has been associated with chemotherapeutic response [43]. Elevated miR-101 expression enhances DNA damage and apoptosis by targeting the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2D1 (UBE2D1), thereby sensitizing hepatoma cells to cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil. Another study reported that miR-101-3p functions as a tumor-suppressive miRNA in liver cancer cells by downregulating the baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5 (BIRC5) gene [44]. In a nude mouse model, BIRC5 overexpression promoted tumor formation, which was abolished upon treatment with a PI3K/AKT inhibitor. These findings collectively indicate that miR-101 exerts antitumor effects in HCC.

miR-520c-3p and HCC

A study by Liu et al. revealed that HCC tissues express high levels of miR-520c-3p [45]. Moreover, HBV infection upregulates miR-520c-3p expression by the HBx/CREB1 axis, thus promoting epithelial‒mesenchymal transition (EMT) through modulation of the AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways. These functional effects were observed in Huh7 cells. Through experimental validation, we found that PTEN is a target gene of miR-520c-3p, the role of which role in HBx-mediated liver carcinogenesis was demonstrated through both in vitro and in vivo studies. In a different study, HepG2 cell lines that overexpressed miR-520c-3p exhibited increased apoptosis, increased sensitivity to doxorubicin and decreased cell proliferation and invasion [46, 47]. The functional role of miR-520c-3p in HCC progression has a dual nature that is dependent on the cellular context, as indicated by these observations.

Interactions among lncrnas, viruses and CccDNA in HCC

HBx-LINE1 and HBV/HCC

Lau et al. reported the integration of HBV in HBV-infected HCC patient-derived HKCI-1, HKCI-4, HKCI-5B, HKCI-7, HKCI-9, and HKCI-11 cell lines via a novel chimeric lncRNA transcript termed HBx-LINE1 [48]. This chimeric transcript was also expressed in an independent cohort of patients with HCC tumors. HBx-LINE1 acts as an oncogenic lncRNA during HCC progression via wnt-β-catenin signaling pathway activation in vitro and in vivo. This finding provides strong evidence that this fusion produces a long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) that promotes HCC development. Another report confirmed these results in HCC progression [49]. It was shown that HBx-LINE1 is abundant in HBV-HCC patients and is inversely correlated with the expression of miR-122, the tumor-suppressive miRNA involved in hepatocarcinogenesis that was described previously. Mechanistically, HBx-LINE1 harbors interaction sites for miR-122, which results in the suppression of miR-122, increased EMT, β-catenin signaling activation, and the repression of E-cadherin expression in Huh7 cell lines. HBx-LINE1 also induces liver cell mitosis and hepatic injury via miR-122 suppression in a mouse model.

Highly upregulated in liver cancer (HULC) and HBV/HCC

One study revealed that the lncRNA HULC is upregulated in HCC tissues [50]. Interestingly, in that study, HULC triggered the expression of HBeAg, HBsAg, HBcAg, pgRNA, HBx, cccDNA, and HBV DNA in HBV-positive liver cancer cell lines (HepG2.2.15 and HepAD38) and in de novo HBV-infected liver cancer cell lines (HepG2-NTCP and differentiated HepRG). HULC stabilized cccDNA through miR-539 induction to suppress apolipoprotein-B mRNA-editing complex 3B (APOBEC3B). A previous study demonstrated that APOBEC3B knockdown in HepG2.2.15 cells increases HBV replication via the C-terminal domain of APOBEC3B [51]. These results demonstrate that APOBEC3B is involved in HBV replication. Zhao and colleagues showed that both HULC expression levels and the frequency of regulatory T cells (Tregs) are significantly increased in the plasma of patients with HBV-cirrhosis [52]. In this sense, ectopic HULC expression increases the Treg frequency. HULC is a well-known target gene of HBx [53]. In vitro assays using liver cancer cell lines (HepG2 and HCCML3) and a fetal hepatocyte cell line (LO2) demonstrated that HULC expression and transcriptional activity are positively regulated by HBx, which is reversed by metformin treatment. Notably, HULC has been reported as a scaffold lncRNA of histone acetyltransferase 1 (HAT1) and HBc in liver cancer cell lines (HepG2, HepG2.2.15, and HepAD38) and primary human hepatocytes [54]. Zhang et al. demonstrated that ectopic expression of HULC promotes cell growth, motility, and tumor formation through its interaction with miR-2052, which in turn leads to the upregulation of the oncogene MET [55]. In addition, HULC overexpression induces the expression of the autophagy-related genes LC3 and Beclin-1 and activates the NF-κB signaling pathway [56]. These findings support the role of HULC in HCC progression through multiple molecular pathways.

Deletion in leukemia 2 (DLEU2) and HBV/HCC

Salerno et al. reported that HBx positively regulates lncRNA-DLEU2 in infected hepatocytes [57]. The binding of HBx to the DLEU2 promoter region in primary human hepatocytes was confirmed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays. Moreover, this lncRNA physically interacts with HBx and enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2). DLEU2 associates with HBx, which promotes transcription and HBV replication through the displacement of EZH2 in HBV-infected HepG2 cells, presumably adjacent to cccDNA. Moreover, the HBx/DLEU2 complex physically interacts with the promoters of some target genes and helps them express host genes whose expression is regularly inhibited by EZH2. These results provide evidence that lncRNA-DLEU2 physically interacts with HBx to increase cccDNA activity and promote HBV replication via epigenetic modifications. Consistently, DLEU2 has been found to associate with EZH2 in SMMC7721 cells [58]. The expression levels of DLEU2 are also upregulated in HCC samples. Depletion of DLEU2 suppresses the growth, migration, and invasiveness of hepatoma cell lines (SMMC7721 and HCLM3 cells). Rescue experiments demonstrated that DLEU2-mediated HCC progression occurs through its association with EZH2. Collectively, these findings suggest that the effects of DLEU2 on HBV replication and HCC progression are dependent on its interaction with EZH2.

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen pseudogene 1 (PCNAP1) and HBV/HCC

Noncoding gene transcripts give rise to lncRNAs, and one of the two subtypes of lncRNAs is referred to as pseudogene-derived lncRNAs; this type is involved in the regulation of cellular functions, disease development, and cancer progression [59]. A pseudogene-derived lncRNA, PCNAP1, is highly expressed in HBV-positive patients and promotes replication and cccDNA accumulation in HBV-infected hepatic cells (primary human hepatocytes and HepaRG) and liver cancer cells (HepG2.2.15) [60]. PCNAP1 mediates HBV replication and cccDNA accumulation through PCNA. PCNAP1 functions as miRNA sponge by which miR-154 upregulates PCNA expression. This interaction upregulates PCNA, which is directly associated with cccDNA and promotes tumor growth. In agreement with these data, another study showed that PCNAP1 is upregulated in patients with HBV-HCC and that its high expression is associated with less favorable survival outcomes [61]. It was demonstrated that PCNAP1 also promotes cell growth through its interaction with miR-340-5p, which leads to the upregulation of activating transcription factor 7 (ATF7) expression. These results highlight the oncogenic role of the pseudogene-derived lncRNA PCNAP1 in promoting HBV replication, cccDNA accumulation and tumor growth through its ability to act as an oncogenic miRNA sponge for miR-154 and miR-340-5p.

HOXA cluster antisense RNA 2 (HOXA-AS2) and HCC

One study reported that HOXA-AS2 is overexpressed in HCC and liver cancer cell lines [62]. Silencing HOXA-AS2 in MHCC97H cells inhibits proliferation and migration and promotes apoptosis, whereas HOXA-AS2 overexpression in Huh7 cells has the opposite effects. Bioinformatics prediction and dual luciferase assay analysis revealed that HOXA-AS2 directly targets miR-520c-3p to inhibit the output of miR-520c-3p. Moreover, rescue experiments further confirmed that miR-520c-3p contributes to the cellular functions mediated by HOXA-AS2. In a previous study [63], similar conclusions were reported. HOXA-AS2 has recently been identified as an HBV-associated lncRNA that is upregulated in HBV-positive liver samples [64]. Notably, HOXA-AS2 was demonstrated to interact directly with cccDNA, generating an RNA/DNA complex that represses its transcription and inhibits HBV replication in HBV-infected HepG2-NTCP cells. Additionally, the association of HOXA-AS2 with the metastasis associated 1 (MTA1) protein and the recruitment of the MTA1-histone deacetylase 1/2 (HDAC1/2) complex to cccDNA was demonstrated by RNA pull-down and RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays. This complex mediates epigenetic histone modifications, particularly through a decrease in H3K9 and H3K27 acetylation.

HOX transcript antisense intergenic RNA (HOTAIR) and HBV/HCC

HOTAIR is a well-known oncogenic lncRNA that participates in cancer progression [65]. Two components of the transcription repressive complex, SUZ12 and ZNF198, were shown to be phosphorylated by PLK1 and then ubiquitinated and degraded in HBx-overexpressing 4pX1 cells and HepAD 38 cells [66]. These regulatory effects are enabled by HOTAIR, and these changes in turn result in changes in chromatin modifications. Previous data indicate that HOTAIR participates in HBx-mediated chromatin modification. In one study, HOTAIR was overexpressed in HBV-infected cells and PBMCs from patients with chronic HBV [67]. Ectopic expression of HOTAIR modulated the HBV promoter by cccDNA-associated SP1, which increased HBV transcription and replication. Previously, HOTAIR was shown to suppress miR-122 expression through DNMT-mediated DNA methylation of the miR-122 promoter region, which represents an epigenetic regulatory mechanism [68]. Functionally, depletion of HOTAIR inhibits cell growth, delays cell cycle progression in vitro, and suppresses tumor formation through the induction of miR-122 expression. Notably, circulating HOTAIR has been identified as a potential biomarker for HCC detection in patients with cirrhosis and for predicting tumor stage [69]. Wu and colleagues demonstrated that β-Elemene treatment inhibits hepatoma cell proliferation by suppressing HOTAIR, SP1, and PDK1 expression [70]. Conversely, overexpression of HOTAIR or SP1 reverses the inhibitory effects of β-Elemene. Taken together, these findings suggest that HOTAIR functions as an oncogenic lncRNA in HCC.

Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1) and HBV/HCC

One study showed that HBx positively regulates MALAT1 expression and inversely regulates miR-124 expression in HepG2 cells [71]. The interaction between miR-124 and MALAT1 was verified by luciferase assays. Rescue experiments revealed that HBx promotes cancer stem cell phenotypes and tumorigenesis via MALAT1 and miR-124, which were previously demonstrated to regulate the PI3K/AKT pathway. In contrast, in a recently published study, MALAT1 deregulation was shown to be associated with decreased expression in patients with HBV-infected germinal center B-cell-like (GCB)-type diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [72]. Ectopic expression of HBx in GCB-type DLBCL cell lines (SUDHL-4 and DB cells) confirmed that MALAT1 expression is inhibited by HBx in cell-based assays. Reoverexpression of MALAT1 partially reverses the effects of HBx-mediated impairment of erastin-induced ferroptosis. This result underscores the heterogeneous and controversial nature of the relationship between HBx and MALAT1 expression and its consequences in different cell lines. In HCC cell lines, MALAT1 expression is positively regulated under hypoxic conditions, as hypoxia-enhanced cell growth and motility are impaired upon MALAT1 knockdown [73]. Furthermore, database analysis and in vitro assays revealed that miR-200a is downregulated by both MALAT1 and hypoxia. miR-200a has been implicated in MALAT1/hypoxia-mediated effects in hepatoma cells. Fan et al. demonstrated that MALAT1 expression is elevated in sorafenib-resistant hepatoma cell lines [74] and that silencing MALAT1 sensitizes these nonresponsive hepatoma cells to sorafenib. Mechanistically, MALAT1 contributes to a sorafenib-resistant phenotype by interacting with miR-140-5p and modulating Aurora-A expression. More recently, MALAT1 was also found to be associated with sorafenib resistance in hepatoma cells [75]. In one study, NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase family member 2 (NSUN2)- and Aly/REF export factor (ALYREF)-mediated 5-methylcytosine modifications led to the upregulation of MALAT1 expression. Moreover, the NSUN2/ALYREF/MALAT1 axis enhances sorafenib resistance by suppressing sorafenib-induced ferroptosis.

NEAT1 and HBV/HCC

NEAT1 is a core regulator of paraspeckle formation in cells [76]. Paraspeckles modulate gene regulation, nuclear export inhibition, and miRNA biogenesis [77,78,79,80]. A clinical cohort study revealed that NEAT1 is expressed at lower levels in chronic HBV-infected patients than in healthy individuals [81]. Furthermore, compared with those in the healthy group, genes involved in innate immunity-related pathways, such as toll-like receptor 6 (TLR-6) and retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), were shown to be downregulated in chronic HBV-infected patients during the active phase. The TLR-6 and RIG-I expression levels were found to be positively correlated with NEAT1 expression according to the correlation assessment. Another report demonstrated that NEAT1 is highly expressed in HCC compared with adjacent normal tissues [82]. In that study, silencing NEAT1 reduced the growth, colony formation and invasiveness of hepatoma cell lines (MHCC97H and SMCC-7721 cells) via the modulation of miR-613 expression. Consistently, NEAT1 has been found to be upregulated in HCC tissues [83]. Its expression levels have also been reported to be greater in liver cancer cell lines, such as HepG2, Huh7, Hep3B, Bel-7404, and SK-Hep1, than in the normal liver cell line LO2. Depletion of NEAT1 suppresses cell growth and motility through its interaction with miR-485. In vitro assays revealed that STAT3 is a direct target gene of miR-485. Collectively, these findings suggest that oncogenic NEAT1 contributes to HCC progression by modulating or interacting with specific miRNAs.

G-quadruplex secondary structure (G4) and hbv/cccdna

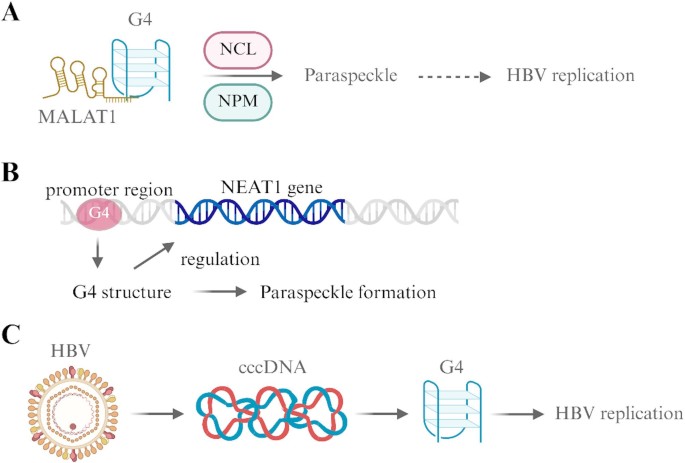

G4s are noncanonical secondary structures that form in nucleic acids, with particular prominence in DNA and RNA [84]. These architectures are stabilized by the stacking of G-quartets, which are planar arrangements of four guanine bases that are held together by Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds. G4 structures commonly appear in guanine-rich areas of the genome, including telomeres, promoter sequences, and the UTRs of mRNAs. They are dynamic in nature, form under physiological conditions and are strongly influenced by ionic strength. G4 structures are relevant to telomere maintenance, gene expression, genome stability, and cellular processes, all of which are highly relevant to cancer biology [85]. G4s occur in telomeric sequences where they regulate telomere length and stability. Telomerase, which extends telomeres in cancer cells, is inhibited through G4 formation, which suggests that these structures are potential therapeutic targets in cancer. Recently, a research group demonstrated that a tanshinone IIA derivative, TA-1, was found to stabilize G4 DNA, thereby repressing angiogenesis and inducing cell death in hepatoma cell lines [86]. Mechanistically, TA-1 treatment activates the ATM/Chk2/p53 signaling cascade, leading to apoptosis. Notably, these findings suggest that TA-1 functions as a G4 stabilizer and may serve as a potential therapeutic agent for the suppression of HCC progression. G4s are also present in oncogene promoter regions (c-MYC and KRAS) [87, 88]. Their assembly can modify transcriptional activity, which frequently leads to the downregulation of oncogene transcription. The specific lncRNAs and viruses that are key to G4 formation are defined below and are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3

Interplay among G4 structures, lncRNAs and HBV. (A) The interaction of MALAT1 with the G4 structure is facilitated by NPM and NCL to induce paraspeckle formation, which facilitates the establishment of HBV replication. (B) G4 structures in the promoter region of NRP1 regulate the expression of the NRP1 gene. (C) The viral genome of HBV functions as cccDNA, an intermediary structure required for HBV replication, as it contains G4 structures. Created with BioRender.com

Telomeric repeat-containing RNA (TERRA) and DNA G4

One pivotal lncRNA, TERRA, comprises UUAGGG repeat sequences that enable the formation of G4 structures in vitro and in vivo [89,90,91,92]. Experimental studies have shown that TERRA is associated with telomeric chromatin [93]. Moreover, depletion of TERRA in mouse embryonic stem cells leads to altered gene expression, which suggests that G4-associated TERRA regulates downstream gene expression. One study reported that TERRA deletion increases the recruitment of the chromatin remodeler ATRX to both repetitive sequences and TERRA target sequences in mouse embryonic stem cells [94]. ChIP-seq analysis also revealed that the levels of H3K9me3 are altered in ATRX-bound genes and that altered H3K9me3 levels are present in both intracisternal A particles (IAPs) and betaretroviral ERV (ERVB) elements after TERRA knockdown. Thus, these results indicate that G4-associated TERRA sequesters ATRX and is responsible for epigenetic regulation.

MALAT1 and RNA G4

The potential of MALAT1 to form RNA G4 structures in vivo has previously been identified using the G4-sequencing dataset and G4 prediction tools, including G4NN [95], cGcC [96] and G4hunter [97]. Spectroscopy assays have confirmed these predictions [98]. Importantly, MALAT1 can directly interact with the NONO protein, and this particular interaction is inhibited by treatment with G4-specific compounds, including pyridostatin and an L-RNA aptamer (L-Apt.4-1c). Another study by Ghosh et al. confirmed that the 3′ end sequence of MALAT1 harbors three RNA G4 domains [99]. The authors used RNA pull-down and RIP assays and discovered that two proteins, nucleolin (NCL) and nucleophosmin (NPM), interact with MALAT1 through its RNA G4 structure (Fig. 3A). Importantly, NCL localizes solely in the nucleolus in MALAT1-/- cells, as opposed to MALAT1+/+ cells, which indicates that MALAT1 not only modulates the expression of NCL but also its cellular distribution.

NEAT1 and G4

As mentioned earlier, NEAT1 participates in paraspeckle formation and regulates a variety of physiological processes. Both NEAT1 and MALAT1 interact with NONO through their G4 motif [98, 100]. Another study reported that G4 and paraspeckle formation rates are greater in breast cancer cell lines than in nontumorigenic cell lines [101]. Importantly, the NEAT1 promoter region contains G4-forming sequences. Additionally, G4 formation is induced by G4-stabilizing reagent treatment, which subsequently regulates paraspeckle formation and NEAT1 expression (Fig. 3B). G4 regulates NEAT1 expression at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels in a variety of cancer cell lines, including U2OS, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231. G4 structures facilitate the formation of paraspeckles and their essential component NEAT1. These results, unfortunately, were observed in breast cancer cell lines but not in hepatoma cell lines. Thus, in subsequent studies, it is necessary to identify whether NEAT1-promoted G4 formation indeed occurs in hepatoma cell lines and whether this event contributes to liver cancer development.

HBV and G4

The association of HBV with G4 structures was recently characterized. Wang et al. also showed that treatment of HBV-infected cells with the G4 stabilizer pyridostatin increases HBc levels in a dose-dependent manner but has no effect on precore RNA or pregenomic RNA [102, 103]. This regulation was based on pgRNA. Importantly, mutation analysis has suggested that G4 structures are affected by pgRNA. On the basis of these results, we concluded that HBV pregenomic RNA produces signals for the G4 structure that modulates viral mRNA transcription. Combined biochemical and functional assays of cccDNA were another major discovery that revealed the presence of G4 structures in cccDNA. Shortly thereafter, mutations were shown occur in the G4 structure at enhancer I of the HBV regulatory sequence, which changes cccDNA and affects HBV replication [103]. To our knowledge, this study is the first to show that G4 structures regulate cccDNA function (Fig. 3C). As mentioned above, G4 structure formation is governed by many lncRNAs. Nonetheless, direct evidence for the roles of TERRA, NEAT1, and MALAT1 in the regulation of cccDNA through G4 structures remains elusive. However, these gaps must be addressed as research moves forward.

Conclusion and perspectives

As mentioned above, ncRNAs (miRNAs and lncRNAs), HBV, and cccDNA each play critical roles in liver cancer progression. Table 1 summarizes their functional interactions across different hepatoma cell lines, highlighting both shared and distinct pathways regulated by specific ncRNAs. HBV-derived cccDNA functions as an “invisible bullet” to promote HCC progression through its modulation of ncRNAs and their downstream target genes and pathways. According to in vitro experiments and clinical observations, HBV-derived cccDNA and HBx serve as upstream regulators of ncRNA expression. Conversely, ncRNAs can also act as key modulators of HBV replication. Collectively, these elements influence one another through specific mechanisms, ultimately driving HCC development. Notably, the maintenance of RNA structures is essential for their biological function. In this review, we also summarize G4 structures, which are implicated in the regulation of both cellular processes and viral replication, within ncRNAs and viral sequences. However, the roles of specific lncRNA-mediated G4 structures in cccDNA regulation and HBV-driven tumorigenesis remain to be fully elucidated. Therefore, the interplay among lncRNAs, G4 structures, cccDNA, and HCC progression is highly important. Innovative strategies that target cccDNA stability, its epigenetic landscape, or its transcriptional activity through ncRNA-based mechanisms hold great potential for HBV eradication and HCC prevention.

Table 1 The actions of NcRNAs and hbv/cccdna

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

HCC:

Hepatocellular carcinoma

ncRNA:

Non-coding RNA

HBV:

Hepatitis B virus

NA:

Nucleos(t)ide analogs

miRNA:

MicroRNA

lncRNA:

Long non-coding RNA

circRNA:

Circular RNA

cccDNA:

Covalently closed circular DNA

ADAR1:

Adenosine deaminase acting on RNA 1

NAFLD:

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

PPARγ:

Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma

PDZK1:

PDZ domain containing 1

UBE2D1:

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2D1

BIRC5:

Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5

HULC:

Highly up-regulated in liver cancer

APOBEC3B:

Apolipoprotein-B mRNA-editing complex 3B

Treg:

Regulatory T cell

HAT1:

Histone acetyltransferase 1

DLEU2:

Deleted in leukemia 2

ChIP:

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

PCNAP1:

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen pseudogene 1

ATF7:

Activating transcription factor 7

EZH2:

Zeste homolog 2

HOXA-AS2:

HOXA cluster antisense RNA 2

MTA1:

Metastasis associated 1

RIP:

RNA immunoprecipitation

HOTAIR:

HOX transcript antisense RNA

MALAT1:

Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1

DLBCL:

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

NSUN2:

NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase family member 2

ALYREF:

Aly/REF export factor

TLR-6:

Toll-like receptor 6

RIG-I:

Retinoic acid-inducible gene I

G4:

G-quadruplex secondary structure

UTR:

Untranslated regions

TERRA:

Telomeric repeat-containing RNA

IAP:

Intracisternal A particle

ERVB:

Betaretroviral ERV elements

NCL:

Nucleolin

NPM:

Nucleophosmin

HIV:

Human immunodeficiency virus

LTR:

Long terminal repeat

References

- Kim DY. Changing etiology and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: Asia and worldwide. J Liver Cancer. 2024;24(1):62–70.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Rumgay H, Arnold M, Ferlay J, Lesi O, Cabasag CJ, Vignat J, et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J Hepatol. 2022;77(6):1598–606.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Uppaluri KR, Challa HJ, Gaur A, Jain R, Krishna Vardhani K, Geddam A, et al. Unlocking the potential of non-coding RNAs in cancer research and therapy. Transl Oncol. 2023;35:101730.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zoulim F, Chen PJ, Dandri M, Kennedy PT, Seeger C. Hepatitis B virus DNA integration: implications for diagnostics, therapy, and outcome. J Hepatol. 2024;81(6):1087–99.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - di Filippo Villa D, Navas MC. Vertical transmission of hepatitis B Virus-An update. Microorganisms. 2023;11(5).

- Lu FT, Ni YH. Elimination of Mother-to-Infant transmission of hepatitis B virus: 35 years of experience. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2020;23(4):311–8.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Abd El Aziz MA, Sacco R, Facciorusso A. Nucleos(t)ide analogues and hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: A literature review. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2020;28:2040206620921331.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chen LL, Kim VN. Small and long non-coding rnas: past, present, and future. Cell. 2024;187(23):6451–85.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lin YH, Chi HC, Wu MH, Liao CJ, Chen CY, Huang PS, et al. The novel role of LOC344887 in the enhancement of hepatocellular carcinoma progression via modulation of SHP1-regulated STAT3/HMGA2 signaling axis. Int J Biol Sci. 2024;20(15):6281–96.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Gama-Carvalho M, Tran N, Editorial. Non-coding RNA elements as regulators of host-pathogen interactions. Front Genet. 2024;15:1374636.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Alharbi KS. Noncoding RNAs in hepatitis: unraveling the apoptotic pathways. Pathol Res Pract. 2024;255:155170.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Li S, Peng M, Tan S, Oyang L, Lin J, Xia L, et al. The roles and molecular mechanisms of non-coding RNA in cancer metabolic reprogramming. Cancer Cell Int. 2024;24(1):37.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhang M, Chen H, Liu H, Tang H. The impact of integrated hepatitis B virus DNA on oncogenesis and antiviral therapy. Biomark Res. 2024;12(1):84.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang F, Song H, Xu F, Xu J, Wang L, Yang F, et al. Role of hepatitis B virus non-structural protein HBx on HBV replication, interferon signaling, and hepatocarcinogenesis. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1322892.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Gajos-Michniewicz A, Czyz M. WNT/beta-catenin signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma: the aberrant activation, pathogenic roles, and therapeutic opportunities. Genes Dis. 2024;11(2):727–46.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Paskeh MDA, Ghadyani F, Hashemi M, Abbaspour A, Zabolian A, Javanshir S, et al. Biological impact and therapeutic perspective of targeting PI3K/Akt signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma: promises and challenges. Pharmacol Res. 2023;187:106553.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Liu Y, Zhang J, Zhai Z, Liu C, Yang S, Zhou Y, et al. Upregulated PrP(C) by HBx enhances NF-kappaB signal via liquid-liquid phase separation to advance liver cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2024;8(1):211.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhang Y, Yan Q, Gong L, Xu H, Liu B, Fang X, et al. C-terminal truncated HBx initiates hepatocarcinogenesis by downregulating TXNIP and reprogramming glucose metabolism. Oncogene. 2021;40(6):1147–61.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lin YH, Wu MH, Liu YC, Lyu PC, Yeh CT, Lin KH. LINC01348 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through Inhibition of SF3B3-mediated EZH2 pre-mRNA splicing. Oncogene. 2021;40(28):4675–85.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bianca C, Sidhartha E, Tiribelli C, El-Khobar KE, Sukowati CHC. Role of hepatitis B virus in development of hepatocellular carcinoma: focus on covalently closed circular DNA. World J Hepatol. 2022;14(5):866–84.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Xia Y, Guo H. Hepatitis B virus cccdna: formation, regulation and therapeutic potential. Antiviral Res. 2020;180:104824.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ren J, Cheng S, Ren F, Gu H, Wu D, Yao X, et al. Epigenetic regulation and its therapeutic potential in hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA. Genes Dis. 2025;12(1):101215.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wang P. The opening of pandora’s box: an emerging role of long noncoding RNA in viral infections. Front Immunol. 2018;9:3138.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jopling C. Liver-specific microRNA-122: biogenesis and function. RNA Biol. 2012;9(2):137–42.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang S, Qiu L, Yan X, Jin W, Wang Y, Chen L, et al. Loss of MicroRNA 122 expression in patients with hepatitis B enhances hepatitis B virus replication through Cyclin G(1) -modulated P53 activity. Hepatology. 2012;55(3):730–41.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chen Y, Shen A, Rider PJ, Yu Y, Wu K, Mu Y, et al. A liver-specific MicroRNA binds to a highly conserved RNA sequence of hepatitis B virus and negatively regulates viral gene expression and replication. FASEB J. 2011;25(12):4511–21.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yang H, Rui F, Li R, Yin S, Xue Q, Hu X, et al. ADAR1 inhibits HBV DNA replication via regulating miR-122-5p in palmitic acid treated HepG2.2.15 cells. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2022;15:4035–47.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Song K, Han C, Zhang J, Lu D, Dash S, Feitelson M, et al. Epigenetic regulation of MicroRNA-122 by peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma and hepatitis b virus X protein in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology. 2013;58(5):1681–92.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ladd AD, Duarte S, Sahin I, Zarrinpar A. Mechanisms of drug resistance in HCC. Hepatology. 2024;79(4):926–40.

PubMed Google Scholar - Fornari F, Gramantieri L, Giovannini C, Veronese A, Ferracin M, Sabbioni S, et al. MiR-122/cyclin G1 interaction modulates p53 activity and affects doxorubicin sensitivity of human hepatocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69(14):5761–7.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Cao F, Yin LX. miR-122 enhances sensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma to oxaliplatin via inhibiting MDR1 by targeting Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Exp Mol Pathol. 2019;106:34–43.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wei X, Liu H, Li X, Liu X. Over-expression of MiR-122 promotes apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma via targeting TLR4. Ann Hepatol. 2019;18(6):869–78.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Potenza N, Papa U, Mosca N, Zerbini F, Nobile V, Russo A. Human MicroRNA hsa-miR-125a-5p interferes with expression of hepatitis B virus surface antigen. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(12):5157–63.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Mosca N, Castiello F, Coppola N, Trotta MC, Sagnelli C, Pisaturo M, et al. Functional interplay between hepatitis B virus X protein and human miR-125a in HBV infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;449(1):141–5.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Li G, Zhang W, Gong L, Huang X. MicroRNA 125a-5p inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in hepatitis B Virus-Related hepatocellular carcinoma by downregulation of ErbB3. Oncol Res. 2019;27(4):449–58.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Liu N, Yang C, Gao A, Sun M, Lv D. MiR-101: an important regulator of gene expression and tumor ecosystem. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(23).

- Wang Y, Tian H. miR-101 suppresses HBV replication and expression by targeting FOXO1 in hepatoma carcinoma cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;487(1):167–72.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Sheng Y, Ding S, Chen K, Chen J, Wang S, Zou C, et al. Functional analysis of miR-101-3p and Rap1b involved in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis. Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;92(2):152–62.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Sheng Y, Li J, Zou C, Wang S, Cao Y, Zhang J, et al. Downregulation of miR-101-3p by hepatitis B virus promotes proliferation and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by targeting Rab5a. Arch Virol. 2014;159(9):2397–410.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Fu Y, Wei X, Tang C, Li J, Liu R, Shen A, et al. Circulating microRNA-101 as a potential biomarker for hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2013;6(6):1811–5.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Xu J, An P, Winkler CA, Yu Y. Dysregulated MicroRNAs in hepatitis B Virus-Related hepatocellular carcinoma: potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1271.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Gao H, Gao Z, Liu X, Sun X, Hu Z, Song Z, et al. miR-101-3p-mediated role of PDZK1 in hepatocellular carcinoma progression and the underlying PI3K/Akt signaling mechanism. Cell Div. 2024;19(1):9.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Mu X, Wei Y, Fan X, Zhang R, Xi W, Zheng G, et al. Aberrant activation of a miR-101-UBE2D1 axis contributes to the advanced progression and chemotherapy sensitivity in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Discov. 2024;10(1):422.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhu W, Ni Q, Wang Z, Zhang R, Liu F, Chang H. MiR-101-3p targets the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway via Birc5 to inhibit invasion, proliferation, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Exp Med. 2025;25(1):88.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Liu Y, Wang J, Chen J, Wu S, Zeng X, Xiong Q, et al. Upregulation of miR-520c-3p via hepatitis B virus drives hepatocellular migration and invasion by the PTEN/AKT/NF-kappaB axis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2022;29:47–63.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Miao HL, Lei CJ, Qiu ZD, Liu ZK, Li R, Bao ST, et al. MicroRNA-520c-3p inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation and invasion through induction of cell apoptosis by targeting glypican-3. Hepatol Res. 2014;44(3):338–48.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ragheb MA, Soliman MH, Elzayat EM, Mohamed MS, El-Ekiaby N, Abdelaziz AI, et al. MicroRNA-520c-3p modulates Doxorubicin-Chemosensitivity in HepG2 cells. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2021;21(2):237–45.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lau CC, Sun T, Ching AK, He M, Li JW, Wong AM, et al. Viral-human chimeric transcript predisposes risk to liver cancer development and progression. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(3):335–49.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Liang HW, Wang N, Wang Y, Wang F, Fu Z, Yan X, et al. Hepatitis B virus-human chimeric transcript HBx-LINE1 promotes hepatic injury via sequestering cellular microRNA-122. J Hepatol. 2016;64(2):278–91.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Liu Y, Feng J, Sun M, Yang G, Yuan H, Wang Y, et al. Long non-coding RNA HULC activates HBV by modulating HBx/STAT3/miR-539/APOBEC3B signaling in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2019;454:158–70.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chen Y, Hu J, Cai X, Huang Y, Zhou X, Tu Z, et al. APOBEC3B edits HBV DNA and inhibits HBV replication during reverse transcription. Antiviral Res. 2018;149:16–25.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zhao J, Fan Y, Wang K, Ni X, Gu J, Lu H, et al. LncRNA HULC affects the differentiation of Treg in HBV-related liver cirrhosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;28(2):901–5.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jiang Z, Liu H. Metformin inhibits tumorigenesis in HBV-induced hepatocellular carcinoma by suppressing HULC overexpression caused by HBX. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(6):4482–95.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yang G, Feng J, Liu Y, Zhao M, Yuan Y, Yuan H, et al. HAT1 signaling confers to assembly and epigenetic regulation of HBV CccDNA minichromosome. Theranostics. 2019;9(24):7345–58.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhang H, Liao Z, Liu F, Su C, Zhu H, Li Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA HULC promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Aging. 2019;11(20):9111–27.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Liu S, Huttad L, He G, He W, Liu C, Cai D, et al. Long noncoding RNA HULC regulates the NF-kappaB pathway and represents a promising prognostic biomarker in liver cancer. Cancer Med. 2023;12(4):5124–36.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Salerno D, Chiodo L, Alfano V, Floriot O, Cottone G, Paturel A, et al. Hepatitis B protein HBx binds the DLEU2 LncRNA to sustain CccDNA and host cancer-related gene transcription. Gut. 2020;69(11):2016–24.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Guo Y, Bai M, Lin L, Huang J, An Y, Liang L, et al. LncRNA DLEU2 aggravates the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma through binding to EZH2. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;118:109272.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lin YH, Yeh CT, Chen CY, Lin KH. Pseudogene: relevant or irrelevant?? Biomed J. 2024:100790.

- Feng J, Yang G, Liu Y, Gao Y, Zhao M, Bu Y, et al. LncRNA PCNAP1 modulates hepatitis B virus replication and enhances tumor growth of liver cancer. Theranostics. 2019;9(18):5227–45.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - He M, Hu L, Bai P, Guo T, Liu N, Feng F, et al. LncRNA PCNAP1 promotes hepatoma cell proliferation through targeting miR-340-5p and is associated with patient survival. J Oncol. 2021;2021:6627173.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhang Y, Xu J, Zhang S, An J, Zhang J, Huang J, et al. HOXA-AS2 promotes proliferation and induces Epithelial-Mesenchymal transition via the miR-520c-3p/GPC3 Axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;50(6):2124–38.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wang F, Yang H, Deng Z, Su Y, Fang Q, Yin Z. HOX antisense LincRNA HOXA-AS2 promotes tumorigenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;40(1–2):287–96.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Qin Y, Ren J, Yu H, He X, Cheng S, Chen W, et al. HOXA-AS2 epigenetically inhibits HBV transcription by recruiting the MTA1-HDAC1/2 deacetylase complex to CccDNA minichromosome. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11(24):e2306810.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hsu CY, Jamal A, Kamal MA, Ahmad F, Bokov DO, Mustafa YF et al. Pathological roles of LncRNA HOTAIR in liver cancer: an updated review. Gene. 2024:149180.

- Zhang H, Diab A, Fan H, Mani SK, Hullinger R, Merle P, et al. PLK1 and HOTAIR accelerate proteasomal degradation of SUZ12 and ZNF198 during hepatitis B Virus-Induced liver carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2015;75(11):2363–74.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ren F, Ren JH, Song CL, Tan M, Yu HB, Zhou YJ, et al. LncRNA HOTAIR modulates hepatitis B virus transcription and replication by enhancing SP1 transcription factor. Clin Sci (Lond). 2020;134(22):3007–22.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Cheng D, Deng J, Zhang B, He X, Meng Z, Li G, et al. LncRNA HOTAIR epigenetically suppresses miR-122 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma via DNA methylation. EBioMedicine. 2018;36:159–70.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - El-Shendidi A, Ghazala R, Hassouna E. Circulating HOTAIR potentially predicts hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic liver and prefigures the tumor stage. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2022;8(2):139–46.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wu J, Tang X, Shi Y, Ma C, Zhang H, Zhang J, et al. Crosstalk of LncRNA HOTAIR and SP1-mediated repression of PDK1 contributes to beta-Elemene-inhibited proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;283:114456.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - He B, Peng F, Li W, Jiang Y. Interaction of lncRNA-MALAT1 and miR-124 regulates HBx-induced cancer stem cell properties in HepG2 through PI3K/Akt signaling. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(3):2908–18.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bai X, Li J, Guo X, Huang Y, Xu X, Tan A, et al. LncRNA MALAT1 promotes Erastin-induced ferroptosis in the HBV-infected diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(11):819.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhao ZB, Chen F, Bai XF. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates hepatocellular carcinoma growth under hypoxia via sponging MicroRNA-200a. Yonsei Med J. 2019;60(8):727–34.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Fan L, Huang X, Chen J, Zhang K, Gu YH, Sun J, et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 contributes to Sorafenib resistance by targeting miR-140-5p/Aurora-A signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2020;19(5):1197–209.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Shi CJ, Pang FX, Lei YH, Deng LQ, Pan FZ, Liang ZQ, et al. 5-methylcytosine methylation of MALAT1 promotes resistance to Sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma through ELAVL1/SLC7A11-mediated ferroptosis. Drug Resist Updat. 2025;78:101181.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Taiana E, Ronchetti D, Todoerti K, Nobili L, Tassone P, Amodio N et al. LncRNA NEAT1 in paraspeckles: A structural scaffold for cellular DNA damage response systems?? Noncoding RNA. 2020;6(3).

- Ingram HB, Fox AH. Unveiling the intricacies of paraspeckle formation and function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2024;90:102399.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hirose T, Virnicchi G, Tanigawa A, Naganuma T, Li R, Kimura H, et al. NEAT1 long noncoding RNA regulates transcription via protein sequestration within subnuclear bodies. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25(1):169–83.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hu SB, Xiang JF, Li X, Xu Y, Xue W, Huang M, et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase CARM1 attenuates the paraspeckle-mediated nuclear retention of mRNAs containing IRAlus. Genes Dev. 2015;29(6):630–45.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jiang L, Shao C, Wu QJ, Chen G, Zhou J, Yang B, et al. NEAT1 scaffolds RNA-binding proteins and the microprocessor to globally enhance pri-miRNA processing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017;24(10):816–24.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zeng Y, Wu W, Fu Y, Chen S, Chen T, Yang B, et al. Toll-like receptors, long non-coding RNA NEAT1, and RIG-I expression are associated with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients in the active phase. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33(5):e22886.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang Z, Zou Q, Song M, Chen J. NEAT1 promotes cell proliferation and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma by negative regulating miR-613 expression. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;94:612–8.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zhang XN, Zhou J, Lu XJ. The long noncoding RNA NEAT1 contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma development by sponging miR-485 and enhancing the expression of the STAT3. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(9):6733–41.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Fracchioni G, Vailati S, Grazioli M, Pirota V. Structural unfolding of G-Quadruplexes: from small molecules to antisense strategies. Molecules. 2024;29(15).

- Kosiol N, Juranek S, Brossart P, Heine A, Paeschke K. G-quadruplexes: a promising target for cancer therapy. Mol Cancer. 2021;20(1):40.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Huang F, Liu Y, Huang J, He D, Wu Q, Zeng Y, et al. Small molecule as potent hepatocellular carcinoma progression inhibitor through stabilizing G-quadruplex DNA to activate replication stress responded DNA damage. Chem Biol Interact. 2025;412:111469.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Esain-Garcia I, Kirchner A, Melidis L, Tavares RCA, Dhir S, Simeone A, et al. G-quadruplex DNA structure is a positive regulator of MYC transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121(7):e2320240121.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang KB, Liu Y, Li J, Xiao C, Wang Y, Gu W, et al. Structural insight into the bulge-containing KRAS oncogene promoter G-quadruplex bound to Berberine and Coptisine. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):6016.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Xu Y, Kaminaga K, Komiyama M. G-quadruplex formation by human telomeric repeats-containing RNA in Na + solution. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(33):11179–84.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Collie GW, Parkinson GN, Neidle S, Rosu F, De Pauw E, Gabelica V. Electrospray mass spectrometry of telomeric RNA (TERRA) reveals the formation of stable multimeric G-quadruplex structures. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(27):9328–34.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Martadinata H, Phan AT. Structure of human telomeric RNA (TERRA): stacking of two G-quadruplex blocks in K(+) solution. Biochemistry. 2013;52(13):2176–83.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Xu Y, Suzuki Y, Ito K, Komiyama M. Telomeric repeat-containing RNA structure in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(33):14579–84.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chu HP, Cifuentes-Rojas C, Kesner B, Aeby E, Lee HG, Wei C, et al. TERRA RNA antagonizes ATRX and protects telomeres. Cell. 2017;170(1):86–e10116.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Tsai RX, Fang KC, Yang PC, Hsieh YH, Chiang IT, Chen Y, et al. TERRA regulates DNA G-quadruplex formation and ATRX recruitment to chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(21):12217–34.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Garant JM, Perreault JP, Scott MS. Motif independent identification of potential RNA G-quadruplexes by G4RNA screener. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(22):3532–7.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Beaudoin JD, Jodoin R, Perreault JP. New scoring system to identify RNA G-quadruplex folding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(2):1209–23.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bedrat A, Lacroix L, Mergny JL. Re-evaluation of G-quadruplex propensity with G4Hunter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(4):1746–59.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Mou X, Liew SW, Kwok CK. Identification and targeting of G-quadruplex structures in MALAT1 long non-coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(1):397–410.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ghosh A, Pandey SP, Joshi DC, Rana P, Ansari AH, Sundar JS, et al. Identification of G-quadruplex structures in MALAT1 LncRNA that interact with nucleolin and nucleophosmin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(17):9415–31.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Simko EAJ, Liu H, Zhang T, Velasquez A, Teli S, Haeusler AR, et al. G-quadruplexes offer a conserved structural motif for NONO recruitment to NEAT1 architectural LncRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(13):7421–38.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bhatt U, Kretzmann AL, Guedin A, Ou A, Kobelke S, Bond CS, et al. The role of G-Quadruplex DNA in paraspeckle formation in cancer. Biochimie. 2021;190:124–31.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wang J, Huang H, Zhao K, Teng Y, Zhao L, Xu Z, et al. G-quadruplex in hepatitis B virus pregenomic RNA promotes its translation. J Biol Chem. 2023;299(9):105151.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Giraud G, Roda M, Huchon P, Michelet M, Maadadi S, Jutzi D, et al. G-quadruplexes control hepatitis B virus replication by promoting CccDNA transcription and phase separation in hepatocytes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(5):2290–305.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan (CMRPG3M2122, CRRPG3N0031 and CORPG3N0592 to WRL; NRRPG3P0011 and CMRPG3P0731 to YHL) and from the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC 113-2311-B-182 A-001- to YHL).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Liver Research Center, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, Taoyuan, Taiwan

Yang-Hsiang Lin, Ming-Wei Lai, Chau-Ting Yeh & Wey-Ran Lin - Graduate Institute of Biomedical Sciences, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan

Yang-Hsiang Lin & Wey-Ran Lin - Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Department of Pediatrics, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital Linkou Main Branch, Taoyuan, Taiwan

Ming-Wei Lai - Institute of stem cell and translational cancer research, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, Taoyuan, Taiwan

Chau-Ting Yeh - Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Linkou Medical Center, Chang Gung University College of Medicine, 5, Fu-Shin Street, Taoyuan, 333, Taiwan

Wey-Ran Lin

Authors

- Yang-Hsiang Lin

- Ming-Wei Lai

- Chau-Ting Yeh

- Wey-Ran Lin

Contributions

Y.H. L., M.W.L., C.T.Y. and W.R.L.: conception and design, manuscript drafting, and final approval.

Corresponding author

Correspondence toWey-Ran Lin.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, YH., Lai, MW., Yeh, CT. et al. Perspectives on NcRNAs in HBV/cccDNA-driven HCC progression.Cancer Cell Int 25, 224 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-025-03849-0

- Received: 17 February 2025

- Accepted: 07 June 2025

- Published: 21 June 2025

- Version of record: 21 June 2025

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-025-03849-0