High Prevalence of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Patients with Moderate to Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (original) (raw)

Journal Article

Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Division

Correspondence and requests for reprints should be addressed to Xavier Soler, M.D., Ph.D., 200 West Arbor Drive, M/C 8377, San Diego, CA 92103-8377. E-mail: [email protected]

Search for other works by this author on:

Pulmonary Division, University of Brasilia, Brasilia, Brazil

Physiology Division, and

Search for other works by this author on:

General Internal Medicine Division, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California; and

Search for other works by this author on:

Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Division

Search for other works by this author on:

Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Division

Search for other works by this author on:

Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Division

Search for other works by this author on:

Published:

01 August 2015

Cite

Xavier Soler, Eduardo Gaio, Frank L. Powell, Joe W. Ramsdell, Jose S. Loredo, Atul Malhotra, Andrew L. Ries, High Prevalence of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Patients with Moderate to Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Annals of the American Thoracic Society, Volume 12, Issue 8, August 2015, Pages 1219–1225, https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201407-336OC

Close

Navbar Search Filter Mobile Enter search term Search

Abstract

Rationale

When obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) coexist in the so-called “overlap” syndrome, a high risk for mortality and morbidity has been reported. There is controversy about the prevalence of OSA in people affected by COPD.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to investigate objective meaures of sleep-disordered breathing in patients with moderate to severe COPD to test the hypothesis that COPD is associated with an increased prevalence of OSA.

Methods

Fifty-four patients (54% men) with moderate to severe COPD were enrolled prospectively (mean ± SD, FEV1 = 42.8 ± 19.8% predicted, and FEV1/FVC = 42.3 ± 13.1). Twenty patients (37%) were on supplemental oxygen at baseline. Exercise tolerance; questionnaires related to symptoms, sleep, and quality of life; and home polysomnography were obtained.

Measurements and Main Results

Forty-four patients had full polysomnography suitable for analysis. OSA (apnea-hypopnea index > 5/h) was present in 29 subjects (65.9%). Sleep efficiency was poor in 45% of subjects.

Conclusions

OSA is highly prevalent in patients with moderate to severe COPD referred to pulmonary rehabilitation. Sleep quality is also poor among this selected group. These patients have greater-than-expected sleep-disordered breathing, which could be an important contributory factor to morbidity and mortality. Pulmonary rehabilitation programs should consider including a sleep assessment in patients with moderate to severe COPD and interventions when indicated to help reduce the impact of OSA in COPD.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a mostly preventable disease characterized by airflow obstruction that is not fully reversible (1). COPD is a major global epidemic that occurs in more than 10% of adults older than 40 years of age. COPD accounts for more than 5% of physician office visits and 13% of all hospitalizations and has recently become the third leading cause of death in the United States (1–5). In a multicenter epidemiological study, COPD was found in 15.8% of men and 5.5% of women (6). A recognized cause of death and comorbidity in subjects with COPD is the presence of cardiovascular events such as stroke, acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or arrhythmias. Because of lack of awareness and somewhat vague symptoms, COPD is underappreciated and underdiagnosed.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a form of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) clinically recognized 4 decades ago (7) and defined by total or partial intermittent collapse of the upper airway resulting in nocturnal hypoxemia and arousals from sleep (8). Recent data (2007–2010) indicate an increasing trend, with 26% of adults estimated to have mild to severe OSA (apnea–hypopnea index [AHI] ≥ 5/h) (9).

Prevalence of OSA increases with age, probably similar to COPD (1, 10, 11). Also, COPD as well as OSA symptoms appear slowly over time and therefore can be easily overlooked. Furthermore, the detrimental cardio vascular effects of OSA are well recognized and can be present even in patients without daytime sleepiness (12–14).

The presence of both OSA and COPD was termed the “overlap” syndrome by Flenley (15). The prevalence of OSA among patients with COPD varies across different studies (16, 17). Some epidemiologic studies have reported OSA to be present in about 10 to 15% of patients with COPD, similar to the general population (18–22).

Little is known about the pathophysiological and clinical consequences of having concomitant COPD and OSA. Recent studies have demonstrated that patients with COPD-OSA have a high risk of death as well as increased risk of exacerbations if OSA remains untreated (23, 24). Also, people with COPD-OSA have more profound hypoxemia (both day and night) than patients having either condition alone and may be predisposed to pulmonary hypertension (19). In patients with OSA, the presence of COPD increases the risk of death sevenfold (25). Therefore, evaluating the presence of OSA in patients with advanced COPD seems logical, as concurrence of these diseases may potentially explain the high cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in these patients.

Pulmonary rehabilitation, a well-established treatment for patients with chronic lung diseases, enhances standard therapy and helps to control and alleviate symptoms, optimize function, and reduce medical and economic burdens of disease (26–33). Patients are typically referred for rehabilitation at advanced stages of the disease with associated comorbid conditions.

The prevalence of the overlap syndrome in this at-risk population is unknown. To that end, we investigated sleep characteristics of patients enrolling in a single-site pulmonary rehabilitation program to determine the prevalence and nature of disordered sleep.

Methods

Patients and Study Design

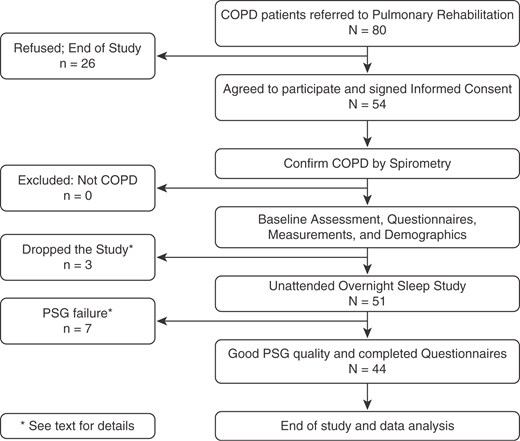

This was a prospective, observational study of patients enrolled in the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program during a 2-year period from September 2010 to August 2012 (Figure 1). Patients presenting sequentially were screened and enrolled based on the following selection criteria: age 40 years or older, diagnosis of COPD confirmed by pulmonary function tests, and important smoke exposure (>10 pack-years accumulated). Experienced staff performed a comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation assessment. Participants had an overnight full sleep study (polysomnograpy [PSG]) at home to capture objective measures of sleep. Patients with a previous diagnosis of OSA or those using supplemental oxygen were included. The UCSD Human Subjects Protection Program approved the protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Figure 1.

Study workflow for patients referred to pulmonary rehabilitation enrolled in the study. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Measurements

Information obtained from the pulmonary rehabilitation evaluation included: demographics; body mass index (BMI), comorbidities (systemic hypertension, past diagnosis of OSA by self-report, depression, diabetes, and dyslipidemia), current use of medications and supplemental oxygen, and available pulmonary function tests. Exercise tolerance was evaluated with a 6-minute-walk test.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Questionnaire Index (PSQI) was used to assess the quality of sleep. The PSQI consists of 19 items and provides a well-validated global index of sleep quality over the previous 1-month time interval. PSQI greater than 5 is generally considered to be an indicator of poor sleep quality (34). Health-related quality of life was evaluated using the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36), a general health profile. The SF-36 contains 36 items used to evaluate subjects in eight subscales (35). Physical and mental composite summary scores were calculated from the subscales.

An assessment of dyspnea was performed using the UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire, which asks patients to rate the severity of their breathlessness experienced with various daily activities (36). We also measured subjective confidence in exercise capacity using the self-efficacy for walking tool, (37). Self-efficacy for walking was measured with a questionnaire modified from that developed by Kaplan and collaborators (37). The questionnaire assesses efficacy expectations associated with the physical activity of walking. A more detailed explanation about those measures is available in the online supplement.

Objective sleep architecture was measured with a full unattended home overnight PSG with 16-channel portable system (Somte PSG; Compumedics Limited, Abbotsford, Victoria, Australia) to evaluate sleep efficiency and architecture, OSA, and nocturnal oxygen desaturations. The International 10–20 system of electrode placement was used. EEG recordings were critical for the proposed project, because nocturnal oxygen desaturations, arousals, and sleep efficiency are important outcome measures. Based on our data on more than 300 subjects in the Sleep Health and Knowledge in U.S. Hispanics study, we anticipated ∼10% of initial sleep recordings to be deficient. Our laboratory has experience with this procedure and has recorded well over 400 home recordings using the Somte. All data were scored by a blinded certified Registered Polysomnographic Technologist using the 2007 American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) criteria (38).

Criteria from the Sleep Heart Health Study were used to determine the quality of PSG recordings (39). Each record was graded in six categories from Outstanding to Unsatisfactory. Poor and Unsatisfactory grade recordings were not used for analyses. An intrascore and interscore reliability was used to validate the findings. Sleep efficiency and apneas were calculated. To identify all physiologically important respiratory events, the 2007 AASM alternative hypopnea definition was used to define hypopneas (i.e., a 50% reduction of airflow amplitude from baseline lasting ≥10 s associated with a ≥3% oxyhemoglobin desaturation and/or an arousal terminating the respiratory event). Arousals were divided into movement, respiratory, and spontaneous (40).

For patients who slept using supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula, the hypopnea definition was modified to also include periods of unequivocal airflow reduction lasting 10 seconds or more regardless of desaturation with or without an arousal. Mean nocturnal oxygen saturation, oxygen desaturation index (drops ≥ 3% in oxygen saturation, ≥10 seconds, <180 s), and percentage of recorded time spent at an oxygen saturation level less than 90% were recorded. OSA was defined as an AHI greater than or equal to 5/h.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize measures at baseline. Comparisons of outcomes between subgroups were evaluated by t tests. The relationships among baseline measures of sleep, lung function, exercise tolerance, and psychosocial function were evaluated initially with a correlation matrix. Mean values are presented ±SD. Candidate variables (P ≤ 0.15) were then evaluated further using stepwise, multivariate regression models to explore the interrelationships and independence among these various measures. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data analyses were conducted using the SPSS 17.0 software package, (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Fifty-four patients completed the baseline assessment. The participants were generally elderly (age, 67.2 ± 8.1 yr), 54% were men, spirometry demonstrated on average moderate to severe COPD, and 37% had been prescribed long-term supplemental oxygen at the time of the study. Three participants consented but dropped out during initial evaluation due to: COPD exacerbation (n = 2) or declined polysomnography (n = 1). Seven PSG studies (13%) were not suitable for analysis: sleep duration less than 4 hours (n = 2), loss of EEG signal (n = 2), and lost raw data in a hardware malfunction (n = 3). A final sample of 44 subjects was included in the analyses.

Baseline demographic, anthropometric, and spirometric data are presented in Table 1 for all subjects who completed the study. There were no demographic differences between patients who dropped out of the study or had inadequate PSG data. Subjects with COPD-OSA had increased BMI and larger neck circumference, but these measures were not significantly different from those without OSA (P = 0.13 and P = 0.21 respectively). Smoking history was not different between patients with COPD-OSA and OSA only (P = 0.33).

Table 1.

Demographic, anthroprometric, and spirometric data (N = 44)

| All Patients (N = 44) | COPD and OSA (n = 29) | COPD no OSA (n = 15) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female, % | 59/41 | 62/38 | 53/47 | 0.58 |

| Age, yr | 67.8 ± 8.4 | 68.1 ± 7.6 | 67.0 ± 10.0 | 0.68 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.9 ± 5.4 | 27.7 ± 5.2 | 25.2 ± 5.4 | 0.13 |

| Neck circumference, cm | 38.4 ± 4.9 | 39.2 ± 4.7 | 37.0 ± 5.2 | 0.21 |

| Smoking, pack-years | 41.8 ± 24.4 | 44.6 ± 24.5 | 36.8 ± 24.4 | 0.33 |

| Spirometry | ||||

| FVC, % predicted | 75.5 ± 18.4 | 76.8 ± 20.0 | 73.1 ± 15.2 | 0.53 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 41.0 ± 18.2 | 41.6 ± 18.8 | 39.8 ± 17.8 | 0.76 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 41.5 ± 12.7 | 41.7 ± 12.4 | 41.3 ± 13.7 | 0.94 |

| All Patients (N = 44) | COPD and OSA (n = 29) | COPD no OSA (n = 15) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female, % | 59/41 | 62/38 | 53/47 | 0.58 |

| Age, yr | 67.8 ± 8.4 | 68.1 ± 7.6 | 67.0 ± 10.0 | 0.68 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.9 ± 5.4 | 27.7 ± 5.2 | 25.2 ± 5.4 | 0.13 |

| Neck circumference, cm | 38.4 ± 4.9 | 39.2 ± 4.7 | 37.0 ± 5.2 | 0.21 |

| Smoking, pack-years | 41.8 ± 24.4 | 44.6 ± 24.5 | 36.8 ± 24.4 | 0.33 |

| Spirometry | ||||

| FVC, % predicted | 75.5 ± 18.4 | 76.8 ± 20.0 | 73.1 ± 15.2 | 0.53 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 41.0 ± 18.2 | 41.6 ± 18.8 | 39.8 ± 17.8 | 0.76 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 41.5 ± 12.7 | 41.7 ± 12.4 | 41.3 ± 13.7 | 0.94 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

Data presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise noted.

Table 1.

Demographic, anthroprometric, and spirometric data (N = 44)

| All Patients (N = 44) | COPD and OSA (n = 29) | COPD no OSA (n = 15) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female, % | 59/41 | 62/38 | 53/47 | 0.58 |

| Age, yr | 67.8 ± 8.4 | 68.1 ± 7.6 | 67.0 ± 10.0 | 0.68 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.9 ± 5.4 | 27.7 ± 5.2 | 25.2 ± 5.4 | 0.13 |

| Neck circumference, cm | 38.4 ± 4.9 | 39.2 ± 4.7 | 37.0 ± 5.2 | 0.21 |

| Smoking, pack-years | 41.8 ± 24.4 | 44.6 ± 24.5 | 36.8 ± 24.4 | 0.33 |

| Spirometry | ||||

| FVC, % predicted | 75.5 ± 18.4 | 76.8 ± 20.0 | 73.1 ± 15.2 | 0.53 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 41.0 ± 18.2 | 41.6 ± 18.8 | 39.8 ± 17.8 | 0.76 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 41.5 ± 12.7 | 41.7 ± 12.4 | 41.3 ± 13.7 | 0.94 |

| All Patients (N = 44) | COPD and OSA (n = 29) | COPD no OSA (n = 15) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female, % | 59/41 | 62/38 | 53/47 | 0.58 |

| Age, yr | 67.8 ± 8.4 | 68.1 ± 7.6 | 67.0 ± 10.0 | 0.68 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.9 ± 5.4 | 27.7 ± 5.2 | 25.2 ± 5.4 | 0.13 |

| Neck circumference, cm | 38.4 ± 4.9 | 39.2 ± 4.7 | 37.0 ± 5.2 | 0.21 |

| Smoking, pack-years | 41.8 ± 24.4 | 44.6 ± 24.5 | 36.8 ± 24.4 | 0.33 |

| Spirometry | ||||

| FVC, % predicted | 75.5 ± 18.4 | 76.8 ± 20.0 | 73.1 ± 15.2 | 0.53 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 41.0 ± 18.2 | 41.6 ± 18.8 | 39.8 ± 17.8 | 0.76 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 41.5 ± 12.7 | 41.7 ± 12.4 | 41.3 ± 13.7 | 0.94 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

Data presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise noted.

OSA (AHI greater than or equal to 5/h) was present in 29 of 44 subjects (65.9%). Only six subjects at baseline (11%) reported having OSA by self-report. Of these, we confirmed OSA in four (severe: n = 2, moderate: n = 2); one subject with a prior OSA diagnosis dropped out of the study because of a COPD exacerbation, and one had loss of EEG signal during polysomonography. New OSA cases represented 85.2% of subjects (23 new cases, 4 previously reported OSA confirmed in our study, and 2 reported OSA but no available PSG).

Mean sleep efficiency was low at 80.8 ± 14.2% (normal, ≥85%) (41–43). Also, we found abnormal sleep architecture in both groups. As expected, stage 1 sleep was significantly higher in subjects with COPD-OSA than subjects with COPD only (P = 0.04), Table 2.

Table 2.

Polysomnographic data (N = 44)

| All Patients (N = 44) | COPD and OSA (n = 29) | COPD no OSA (n = 15) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep efficiency, % | 80.8 ± 14.2 | 80.2 ± 15.8 | 81.9 ± 10.8 | 0.71 |

| N1, % | 22.5 ± 15.0 | 25.8 ± 16.8 | 16.0 ± 7.4 | 0.04 |

| N2, % | 58.5 ± 13.6 | 55.9 ± 14.1 | 63.5 ± 11.4 | 0.08 |

| N3, % | 7.1 ± 8.7 | 7.4 ± 8.1 | 6.6 ± 10.0 | 0.77 |

| REM, % | 11.9 ± 7.8 | 10.9 ± 7.8 | 13.8 ± 7.8 | 0.24 |

| Arousal index, events/h | 29.4 ± 17.3 | 34.5 ± 17.9 | 19.4 ± 10.5 | 0.004 |

| AHI, events/h | 18.3 ± 20.8 | 26.4 ± 21.5 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

| All Patients (N = 44) | COPD and OSA (n = 29) | COPD no OSA (n = 15) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep efficiency, % | 80.8 ± 14.2 | 80.2 ± 15.8 | 81.9 ± 10.8 | 0.71 |

| N1, % | 22.5 ± 15.0 | 25.8 ± 16.8 | 16.0 ± 7.4 | 0.04 |

| N2, % | 58.5 ± 13.6 | 55.9 ± 14.1 | 63.5 ± 11.4 | 0.08 |

| N3, % | 7.1 ± 8.7 | 7.4 ± 8.1 | 6.6 ± 10.0 | 0.77 |

| REM, % | 11.9 ± 7.8 | 10.9 ± 7.8 | 13.8 ± 7.8 | 0.24 |

| Arousal index, events/h | 29.4 ± 17.3 | 34.5 ± 17.9 | 19.4 ± 10.5 | 0.004 |

| AHI, events/h | 18.3 ± 20.8 | 26.4 ± 21.5 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: AHI = apnea–hypopnea index; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; N1–N3 = sleep stages; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; REM = rapid eye movement.

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Table 2.

Polysomnographic data (N = 44)

| All Patients (N = 44) | COPD and OSA (n = 29) | COPD no OSA (n = 15) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep efficiency, % | 80.8 ± 14.2 | 80.2 ± 15.8 | 81.9 ± 10.8 | 0.71 |

| N1, % | 22.5 ± 15.0 | 25.8 ± 16.8 | 16.0 ± 7.4 | 0.04 |

| N2, % | 58.5 ± 13.6 | 55.9 ± 14.1 | 63.5 ± 11.4 | 0.08 |

| N3, % | 7.1 ± 8.7 | 7.4 ± 8.1 | 6.6 ± 10.0 | 0.77 |

| REM, % | 11.9 ± 7.8 | 10.9 ± 7.8 | 13.8 ± 7.8 | 0.24 |

| Arousal index, events/h | 29.4 ± 17.3 | 34.5 ± 17.9 | 19.4 ± 10.5 | 0.004 |

| AHI, events/h | 18.3 ± 20.8 | 26.4 ± 21.5 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

| All Patients (N = 44) | COPD and OSA (n = 29) | COPD no OSA (n = 15) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep efficiency, % | 80.8 ± 14.2 | 80.2 ± 15.8 | 81.9 ± 10.8 | 0.71 |

| N1, % | 22.5 ± 15.0 | 25.8 ± 16.8 | 16.0 ± 7.4 | 0.04 |

| N2, % | 58.5 ± 13.6 | 55.9 ± 14.1 | 63.5 ± 11.4 | 0.08 |

| N3, % | 7.1 ± 8.7 | 7.4 ± 8.1 | 6.6 ± 10.0 | 0.77 |

| REM, % | 11.9 ± 7.8 | 10.9 ± 7.8 | 13.8 ± 7.8 | 0.24 |

| Arousal index, events/h | 29.4 ± 17.3 | 34.5 ± 17.9 | 19.4 ± 10.5 | 0.004 |

| AHI, events/h | 18.3 ± 20.8 | 26.4 ± 21.5 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: AHI = apnea–hypopnea index; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; N1–N3 = sleep stages; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; REM = rapid eye movement.

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

There were no differences in measures of dyspnea, exercise tolerance, health-related quality of life, quality of sleep, and sleepiness between patients with COPD only and patients with COPD-OSA “overlap.” Overall, subjective sleep quality was poor (mean PSQI, 8.3 ± 4.3; normal ≤ 5). Results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Baseline results on dyspnea, exercise tolerance, health-related quality of life, quality of sleep, and sleepiness (N = 44)

| All Patients (N = 44) | COPD and OSA (n = 29) | COPD no OSA (n = 15) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire | 45.8 ± 15.5 | 45.9 ± 16.1 | 45.5 ± 15.0 | 0.94 |

| UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire. | 50.2 ± 19.1 | 51.1 ± 19.8 | 48.4 ± 18.3 | 0.67 |

| 6_-_min-walk test | ||||

| Distance, m | 376 ± 106 | 379 ± 105 | 369 ± 111 | 0.77 |

| Resting SpO2, % | 95.5 ± 2.0 | 95.4 ± 1.8 | 95.6 ± 2.5 | 0.77 |

| Short Form-36 Health Survey | ||||

| Physical | 35.2 ± 10.0 | 35.5 ± 10.3 | 34.5 ± 9.7 | 0.77 |

| Mental | 52.9 ± 9.3 | 53.6 ± 8.8 | 51.5 ± 10.4 | 0.50 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | 8.3 ± 4.3 | 7.7 ± 3.9 | 9.3 ± 4.9 | 0.26 |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale | 7.8 ± 4.4 | 8.7 ± 4.4 | 6.2 ± 4.1 | 0.08 |

| All Patients (N = 44) | COPD and OSA (n = 29) | COPD no OSA (n = 15) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire | 45.8 ± 15.5 | 45.9 ± 16.1 | 45.5 ± 15.0 | 0.94 |

| UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire. | 50.2 ± 19.1 | 51.1 ± 19.8 | 48.4 ± 18.3 | 0.67 |

| 6_-_min-walk test | ||||

| Distance, m | 376 ± 106 | 379 ± 105 | 369 ± 111 | 0.77 |

| Resting SpO2, % | 95.5 ± 2.0 | 95.4 ± 1.8 | 95.6 ± 2.5 | 0.77 |

| Short Form-36 Health Survey | ||||

| Physical | 35.2 ± 10.0 | 35.5 ± 10.3 | 34.5 ± 9.7 | 0.77 |

| Mental | 52.9 ± 9.3 | 53.6 ± 8.8 | 51.5 ± 10.4 | 0.50 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | 8.3 ± 4.3 | 7.7 ± 3.9 | 9.3 ± 4.9 | 0.26 |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale | 7.8 ± 4.4 | 8.7 ± 4.4 | 6.2 ± 4.1 | 0.08 |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; SpO2 = oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry; UCSD = University of California, San Diego.

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Table 3.

Baseline results on dyspnea, exercise tolerance, health-related quality of life, quality of sleep, and sleepiness (N = 44)

| All Patients (N = 44) | COPD and OSA (n = 29) | COPD no OSA (n = 15) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire | 45.8 ± 15.5 | 45.9 ± 16.1 | 45.5 ± 15.0 | 0.94 |

| UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire. | 50.2 ± 19.1 | 51.1 ± 19.8 | 48.4 ± 18.3 | 0.67 |

| 6_-_min-walk test | ||||

| Distance, m | 376 ± 106 | 379 ± 105 | 369 ± 111 | 0.77 |

| Resting SpO2, % | 95.5 ± 2.0 | 95.4 ± 1.8 | 95.6 ± 2.5 | 0.77 |

| Short Form-36 Health Survey | ||||

| Physical | 35.2 ± 10.0 | 35.5 ± 10.3 | 34.5 ± 9.7 | 0.77 |

| Mental | 52.9 ± 9.3 | 53.6 ± 8.8 | 51.5 ± 10.4 | 0.50 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | 8.3 ± 4.3 | 7.7 ± 3.9 | 9.3 ± 4.9 | 0.26 |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale | 7.8 ± 4.4 | 8.7 ± 4.4 | 6.2 ± 4.1 | 0.08 |

| All Patients (N = 44) | COPD and OSA (n = 29) | COPD no OSA (n = 15) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire | 45.8 ± 15.5 | 45.9 ± 16.1 | 45.5 ± 15.0 | 0.94 |

| UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire. | 50.2 ± 19.1 | 51.1 ± 19.8 | 48.4 ± 18.3 | 0.67 |

| 6_-_min-walk test | ||||

| Distance, m | 376 ± 106 | 379 ± 105 | 369 ± 111 | 0.77 |

| Resting SpO2, % | 95.5 ± 2.0 | 95.4 ± 1.8 | 95.6 ± 2.5 | 0.77 |

| Short Form-36 Health Survey | ||||

| Physical | 35.2 ± 10.0 | 35.5 ± 10.3 | 34.5 ± 9.7 | 0.77 |

| Mental | 52.9 ± 9.3 | 53.6 ± 8.8 | 51.5 ± 10.4 | 0.50 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | 8.3 ± 4.3 | 7.7 ± 3.9 | 9.3 ± 4.9 | 0.26 |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale | 7.8 ± 4.4 | 8.7 ± 4.4 | 6.2 ± 4.1 | 0.08 |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; SpO2 = oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry; UCSD = University of California, San Diego.

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Table 4 reports the sleep data of patients stratified by BMI. As expected, OSA was significantly more prevalent among overweight individuals (77.8% if BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 and 47.1% for BMI < 25 kg/m2; P = 0.04).

Table 4.

Body mass index and age, apnea-hypopnea index, oxygen desaturation index, and obstructive sleep apnea

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (n = 27) | BMI < 25 kg/m2 (n = 17) | P Value* | All (N = 44) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 66.3 ± 8.2 | 70.1 ± 8.4 | 0.15 | 67.8 ± 8.4 |

| AHI, events/h | 22.8 ± 22.1 | 11.0 ± 16.8 | 0.07 | 18.3 ± 20.8 |

| ODI, events/h | 15.3 ± 20.3 | 6.0 ± 13.1 | 0.10 | 11.7 ± 18.3 |

| OSA†, % | 77.8 | 47.1 | 0.04 | 65.9 |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (n = 27) | BMI < 25 kg/m2 (n = 17) | P Value* | All (N = 44) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 66.3 ± 8.2 | 70.1 ± 8.4 | 0.15 | 67.8 ± 8.4 |

| AHI, events/h | 22.8 ± 22.1 | 11.0 ± 16.8 | 0.07 | 18.3 ± 20.8 |

| ODI, events/h | 15.3 ± 20.3 | 6.0 ± 13.1 | 0.10 | 11.7 ± 18.3 |

| OSA†, % | 77.8 | 47.1 | 0.04 | 65.9 |

Definition of abbreviations: AHI = apnea–hypopnea index; BMI = body mass index; ODI = oxygen desaturation index; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

* Chi-square test.

† Prevalence using AHI.

Table 4.

Body mass index and age, apnea-hypopnea index, oxygen desaturation index, and obstructive sleep apnea

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (n = 27) | BMI < 25 kg/m2 (n = 17) | P Value* | All (N = 44) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 66.3 ± 8.2 | 70.1 ± 8.4 | 0.15 | 67.8 ± 8.4 |

| AHI, events/h | 22.8 ± 22.1 | 11.0 ± 16.8 | 0.07 | 18.3 ± 20.8 |

| ODI, events/h | 15.3 ± 20.3 | 6.0 ± 13.1 | 0.10 | 11.7 ± 18.3 |

| OSA†, % | 77.8 | 47.1 | 0.04 | 65.9 |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (n = 27) | BMI < 25 kg/m2 (n = 17) | P Value* | All (N = 44) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 66.3 ± 8.2 | 70.1 ± 8.4 | 0.15 | 67.8 ± 8.4 |

| AHI, events/h | 22.8 ± 22.1 | 11.0 ± 16.8 | 0.07 | 18.3 ± 20.8 |

| ODI, events/h | 15.3 ± 20.3 | 6.0 ± 13.1 | 0.10 | 11.7 ± 18.3 |

| OSA†, % | 77.8 | 47.1 | 0.04 | 65.9 |

Definition of abbreviations: AHI = apnea–hypopnea index; BMI = body mass index; ODI = oxygen desaturation index; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

* Chi-square test.

† Prevalence using AHI.

Table 5 reports sleep data of patients stratified by use of supplemental oxygen. Those using supplemental oxygen had an AHI greater than or equal to 5/h marginally less frequently than patients who slept on room air (50 vs. 76.9%, P = 0.06, for oxygen use and room air, respectively).

Table 5.

Apnea-hypopnea index, obstructive sleep apnea, and oxygen desaturation index in patients with and without long-term oxygen therapy.

| No Supplemental O2 (n = 26) | Supplemental O2 (n = 18) | P Value* | All (N = 44) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHI, events/h | 21.6 ± 22.8 | 13.5 ± 17.0 | 0.21 | 18.3 ± 20.8 |

| OSA†, % | 76.9 | 50.0 | 0.06 | 65.9 |

| ODI, events/h | 15.2 ± 18.6 | 6.6 ± 16.9 | 0.13 | 11.7 ± 18.3 |

| No Supplemental O2 (n = 26) | Supplemental O2 (n = 18) | P Value* | All (N = 44) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHI, events/h | 21.6 ± 22.8 | 13.5 ± 17.0 | 0.21 | 18.3 ± 20.8 |

| OSA†, % | 76.9 | 50.0 | 0.06 | 65.9 |

| ODI, events/h | 15.2 ± 18.6 | 6.6 ± 16.9 | 0.13 | 11.7 ± 18.3 |

Definition of abbreviations: AHI = apnea–hypopnea index; ODI = oxygen desaturation index; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

* Chi-square test.

† Prevalence using AHI.

Table 5.

Apnea-hypopnea index, obstructive sleep apnea, and oxygen desaturation index in patients with and without long-term oxygen therapy.

| No Supplemental O2 (n = 26) | Supplemental O2 (n = 18) | P Value* | All (N = 44) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHI, events/h | 21.6 ± 22.8 | 13.5 ± 17.0 | 0.21 | 18.3 ± 20.8 |

| OSA†, % | 76.9 | 50.0 | 0.06 | 65.9 |

| ODI, events/h | 15.2 ± 18.6 | 6.6 ± 16.9 | 0.13 | 11.7 ± 18.3 |

| No Supplemental O2 (n = 26) | Supplemental O2 (n = 18) | P Value* | All (N = 44) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHI, events/h | 21.6 ± 22.8 | 13.5 ± 17.0 | 0.21 | 18.3 ± 20.8 |

| OSA†, % | 76.9 | 50.0 | 0.06 | 65.9 |

| ODI, events/h | 15.2 ± 18.6 | 6.6 ± 16.9 | 0.13 | 11.7 ± 18.3 |

Definition of abbreviations: AHI = apnea–hypopnea index; ODI = oxygen desaturation index; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

* Chi-square test.

† Prevalence using AHI.

OSA was also marginally more prevalent among younger subjects (age > 65 years, 37% and ≤65 years, 69%; P = 0.06). The presence of OSA was not correlated with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, insomnia index, sleep quality, dyspnea scale, anxiety/depression scales, exercise tolerance, BODE index (Body-mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea scale, and Exercise capacity index) (44), or FEV1. However, BMI did correlate with OSA (r = 0.33, P = 0.03).

Discussion

We observed a high prevalence of SDB in patients with moderate to severe COPD referred to our pulmonary rehabilitation program. The presence of both COPD and OSA coexisting was termed by Flenley as the “overlap” syndrome (15). We have further identified poor sleep quality based on both PSQI questionnaire and low sleep efficiency in full polysomonography in these patients undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation. These findings may be important causative risk factors among patients with COPD (e.g., increased cardiovascular events, reduced quality of life) in afflicted individuals. Furthermore, our study demonstrated that the majority of subjects were naive to the OSA diagnosis, which may be clinically important.

The literature regarding sleep in COPD is somewhat mixed. The Sleep Heart Health study, for example, found no major increase in OSA risk among patients with COPD compared with matched control subjects (18). However, the authors studied a community sample of patients with mild subclinical disease, and thus the findings may not generalize to clinical cohorts. On the other hand, Sharma and coworkers found a high risk of OSA in patients with COPD, but the authors failed to use gold standard polysomnography, and thus the results may be biased by misclassification (45).

In addition to the causes of abnormal sleep seen in a general population and in patients with other chronic diseases, patients with COPD may have particular problems that contribute to poor sleep. More profound arterial hypoxemia (and perhaps associated hypercapnia) are found in patients with COPD-OSA than those with OSA alone (46, 47). In addition, changes during sleep in chemoreceptor sensitivity and ventilatory control, respiratory mechanics, respiratory muscle function, and symptoms such as cough and sputum production may occur in these patients (48–56). Patients with severe emphysema are known to have poor sleep quality. Krachman and collaborators studied 25 patients with COPD and emphysema and found that sleep quality was poor, nocturnal oxygenation desaturations were common, and the measurements of respiratory mechanics and function as well as nocturnal oxygenation desaturations were important predictors of sleep quality (57). It is certainly reasonable to speculate that poor sleep quality is an important contributing factor to the markedly impaired quality of life seen in patients with COPD.

Multiple mechanisms may be implicated in the link between OSA and COPD. End-expiratory lung volume has an important impact on pharyngeal mechanics, and thus the hyperinflation associated with COPD may protect against upper airway collapse (58). Conversely, because lung elastic recoil is believed to be important, the dilation and destruction of lung parenchyma seen in emphysema may reduce caudal traction forces believed to stabilize the upper airway.

Regarding body weight, we found a weak correlation (r = 0.33) between OSA and BMI, confirming the results of previously published studies demonstrating a relationship between weight and OSA (9, 59). However, in our study, one out of two subjects with a BMI less than 25 kg/m2 were found to have OSA, and therefore OSA should be also suspected among nonobese patients with COPD. Although end-stage COPD can be associated with cachexia, which might be predicted to protect against OSA, patients often gain weight after smoking cessation or with systemic glucocorticoid use and, thus, may be predisposed to OSA. As a result, the uncertainty in the literature may reflect differences in study populations, including stages of disease as well as prior pharmacological therapy.

Despite the strengths of our study, we also acknowledge a number of limitations. First, the scoring criteria for SDB in COPD are imperfect. For example, a 3-minute reduction in breathing would be counted as one hypopnea even though it may have serious clinical implications. Thus, we used the gold standard criteria as defined by AASM but recognize the need for further research in this area (38, 60).

Second, although this is the first in-depth report of SDB in patients presenting for pulmonary rehabilitation, our sample size was modest compared with some prior reports in more general COPD populations. We studied a relatively sick homogeneous cohort of pulmonary rehabilitation participants, and thus our findings should not be seen as generalizable to all patients with COPD, specifically those having mild disease. Larger-scale studies are warranted based on our results.

Third, a number of our participants were using oxygen, which could affect the sensitivity of nasal cannula to judge hypopneas. In addition, based on the shape of the oxy-hemoglobin saturation curve, the sensitivity of the pulse oximeter for desaturation may be reduced depending on the baseline saturations while on therapy. The observation that oxygen-treated patients had marginally significant less OSA than those not on oxygen could reflect these methodological limitations but could equally occur as a result of beneficial effects of oxygen on ventilatory control instability (i.e., loop gain) (61).

A selection bias could have occurred, as patients referred to pulmonary rehabilitation have usually more severe disease than those who are managed in regular COPD clinics. However, our intent was to study patients with more advanced disease, as mild COPD has been previously researched. The participants in our research have typical demographic and anthropometric data compared with our usual outpatient COPD clinics. We have also previously observed that patients with advanced COPD do not describe classic OSA symptoms, and thus we doubt that patients with sleep apnea symptoms were more motivated to participate in our study or preferentially enrolled. However, we acknowledge the need for further research in this area to assess the generalizability of our findings. Despite these limitations, we are confident that our findings add to the existing literature.

In summary, in this study we found that a high percentage of patients with moderate to severe COPD referred to pulmonary rehabilitation had OSA, poor sleep efficiency, and poor sleep quality. Supplemental oxygen may be protective in this group of patients. Pulmonary rehabilitation programs may provide unique platforms to incorporate measures of sleep assessment that could eventually benefit this highly selected group of patients.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank, in alphabetical order, Maria Correa, Pamela DeYoung, Trina Limberg, Anne Mohney, Erik Smales, Russel Trojino, and Arianna Villa for data collection, sleep assessment, and patient care throughout the program. They also thank Dr. Shu-Yi Liao for statistical support, and all the patients who kindly participated in this study.

Footnotes

Funded by the Tobacco Related Disease Reserch Program New Investigator Award KT-0014 (X.S.), Center of Translational Research Institute seed grant UL1TR000100 from the National Institutes of Health, and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) grant 103/26-0 (E.G.) from the Brazilian Ministry of Higher Education.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of National Institutes of Health.

Author Contributions: X.S. takes responsibility for the study as a whole. A.L.R., A.M., and J.S.L. contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis, statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation. E.G. contributed to data and statistical analysis and manuscript preparation. J.W.R. and F.L.P. contributed to data analysis and manuscript preparation.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article.

References

Vestbo

J

,

Hurd

SS

,

Agustí

AG

,

Jones

PW

,

Vogelmeier

C

,

Anzueto

A

,

Barnes

PJ

,

Fabbri

LM

,

Martinez

FJ

,

Nishimura

M

, et al.

Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary

.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2013

;

187

:

347

–

365

.

Pauwels

RA

,

Buist

AS

,

Calverley

PM

,

Jenkins

CR

,

Hurd

SS

;

GOLD Scientific Committee

.

Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary

.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2001

;

163

:

1256

–

1276

.

Lindberg

A

,

Jonsson

AC

,

Ronmark

E

,

Lundgren

R

,

Larsson

LG

,

Lundback

B

.

Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease according to BTS, ERS, GOLD and ATS criteria in relation to doctor's diagnosis, symptoms, age, gender, and smoking habits

.

Respiration

2005

;

72

:

471

–

479

.

Mannino

DM

,

Buist

AS

.

Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends

.

Lancet

2007

;

370

:

765

–

773

.

Miniño

AM

,

Murphy

SL

,

Xu

J

,

Kochanek

KD

.

Deaths: final data for 2008

.

Natl Vital Stat Rep

2011

;

59

:

1

–

126

.

Peña

VS

,

Miravitlles

M

,

Gabriel

R

,

Jiménez-Ruiz

CA

,

Villasante

C

,

Masa

JF

,

Viejo

JL

,

Fernández-Fau

L

.

Geographic variations in prevalence and underdiagnosis of COPD: results of the IBERPOC multicentre epidemiological study

.

Chest

2000

;

118

:

981

–

989

.

Guilleminault

C

,

Tilkian

A

,

Dement

WC

.

The sleep apnea syndromes

.

Annu Rev Med

1976

;

27

:

465

–

484

.

Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force

.

Sleep

1999

;

22

:

667

–

689

.

Peppard

PE

,

Young

T

,

Barnet

JH

,

Palta

M

,

Hagen

EW

,

Hla

KM

.

Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults

.

Am J Epidemiol

2013

;

177

:

1006

–

1014

.

Young

T

,

Peppard

PE

,

Gottlieb

DJ

.

Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective

.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2002

;

165

:

1217

–

1239

.

Cosio

MG

,

Cazzuffi

R

,

Saetta

M

.

Is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease a disease of aging?

Respiration

2014

;

87

:

508

–

512

.

Golbin

JM

,

Somers

VK

,

Caples

SM

.

Obstructive sleep apnea, cardiovascular disease, and pulmonary hypertension

.

Proc Am Thorac Soc

2008

;

5

:

200

–

206

.

Kato

M

,

Adachi

T

,

Koshino

Y

,

Somers

VK

.

Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease

.

Circ J

2009

;

73

:

1363

–

1370

.

Kent

BD

,

Garvey

JF

,

Ryan

S

,

Nolan

G

,

Dodd

JD

,

McNicholas

WT

.

Severity of obstructive sleep apnoea predicts coronary artery plaque burden: a coronary computed tomographic angiography study

.

Eur Respir J

2013

;

42

:

1263

–

1270

.

Flenley

DC

.

Sleep in chronic obstructive lung disease

.

Clin Chest Med

1985

;

6

:

651

–

661

.

Weitzenblum

E

,

Chaouat

A

,

Kessler

R

,

Canuet

M

.

Overlap syndrome: obstructive sleep apnea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

.

Proc Am Thorac Soc

2008

;

5

:

237

–

241

.

Guilleminault

C

,

Cummiskey

J

,

Motta

J

.

Chronic obstructive airflow disease and sleep studies

.

Am Rev Respir Dis

1980

;

122

:

397

–

406

.

Sanders

MH

,

Newman

AB

,

Haggerty

CL

,

Redline

S

,

Lebowitz

M

,

Samet

J

,

O’Connor

GT

,

Punjabi

NM

,

Shahar

E

;

Sleep Heart Health Study

.

Sleep and sleep-disordered breathing in adults with predominantly mild obstructive airway disease

.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2003

;

167

:

7

–

14

.

Chaouat

A

,

Weitzenblum

E

,

Krieger

J

,

Ifoundza

T

,

Oswald

M

,

Kessler

R

.

Association of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sleep apnea syndrome

.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med

1995

;

151

:

82

–

86

.

Bednarek

M

,

Plywaczewski

R

,

Jonczak

L

,

Zielinski

J

.

There is no relationship between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a population study

.

Respiration

2005

;

72

:

142

–

149

.

Fleetham

JA

.

Is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease related to sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome?

Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2003

;

167

:

3

–

4

.

McNicholas

WT

.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea: overlaps in pathophysiology, systemic inflammation, and cardiovascular disease

.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2009

;

180

:

692

–

700

.

Marin

JM

,

Soriano

JB

,

Carrizo

SJ

,

Boldova

A

,

Celli

BR

.

Outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea: the overlap syndrome

.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2010

;

182

:

325

–

331

.

Machado

MC

,

Vollmer

WM

,

Togeiro

SM

,

Bilderback

AL

,

Oliveira

MV

,

Leitão

FS

,

Queiroga

F

Jr,

Lorenzi-Filho

G

,

Krishnan

JA

.

CPAP and survival in moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome and hypoxaemic COPD

.

Eur Respir J

2010

;

35

:

132

–

137

.

Lavie

P

,

Herer

P

,

Lavie

L

.

Mortality risk factors in sleep apnoea: a matched case-control study

.

J Sleep Res

2007

;

16

:

128

–

134

.

Lacasse

Y

,

Wong

E

,

Guyatt

GH

,

King

D

,

Cook

DJ

,

Goldstein

RS

.

Meta-analysis of respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

.

Lancet

1996

;

348

:

1115

–

1119

.

ACCP/AACVPR Pulmonary Rehabilitation Guidelines Panel. American College of Chest Physicians. American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

.

Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based guidelines

.

Chest

1997

;

112

:

1363

–

1396

.

Lacasse

Y

,

Brosseau

L

,

Milne

S

,

Martin

S

,

Wong

E

,

Guyatt

GH

,

Goldstein

RS

.

Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2002

;

3

:

CD003793

.

Ramirez-Sarmiento

A

,

Orozco-Levi

M

,

Guell

R

,

Barreiro

E

,

Hernandez

N

,

Mota

S

,

Sangenis

M

,

Broquetas

JM

,

Casan

P

,

Gea

J

.

Inspiratory muscle training in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: structural adaptation and physiologic outcomes

.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2002

;

166

:

1491

–

1497

.

Mota

S

,

Güell

R

,

Barreiro

E

,

Solanes

I

,

Ramírez-Sarmiento

A

,

Orozco-Levi

M

,

Casan

P

,

Gea

J

,

Sanchis

J

.

Clinical outcomes of expiratory muscle training in severe COPD patients

.

Respir Med

2007

;

101

:

516

–

524

.

Ries

AL

,

Bauldoff

GS

,

Carlin

BW

,

Casaburi

R

,

Emery

CF

,

Mahler

DA

,

Make

B

,

Rochester

CL

,

Zuwallack

R

,

Herrerias

C

.

Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines

.

Chest

2007

;

131

:

4S

–

42S

.

Mota

S

,

Güell

R

,

Barreiro

E

,

Casan

P

,

Gea

J

,

Sanchis

J

.

Relationship between expiratory muscle dysfunction and dynamic hyperinflation in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[in Spanish]

.

Arch Bronconeumol

2009

;

45

:

487

–

495

.

Spruit

MA

,

Singh

SJ

,

Garvey

C

,

ZuWallack

R

,

Nici

L

,

Rochester

C

,

Hill

K

,

Holland

AE

,

Lareau

SC

,

Man

WD

, et al. ;

ATS/ERS Task Force on Pulmonary Rehabilitation

.

An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation

.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2013

;

188

:

e13

–

e64

.

Buysse

DJ

,

Reynolds

CF

III,

Monk

TH

,

Berman

SR

,

Kupfer

DJ

.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research

.

Psychiatry Res

1989

;

28

:

193

–

213

.

Ware

JE

Jr,

Gandek

B

.

Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project

.

J Clin Epidemiol

1998

;

51

:

903

–

912

.

Eakin

EG

,

Resnikoff

PM

,

Prewitt

LM

,

Ries

AL

,

Kaplan

RM

.

Validation of a new dyspnea measure: the UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire. University of California, San Diego

.

Chest

1998

;

113

:

619

–

624

.

Kaplan

RM

,

Atkins

CJ

,

Reinsch

S

.

Specific efficacy expectations mediate exercise compliance in patients with COPD

.

Health Psychol

1984

;

3

:

223

–

242

.

Ruehland

WR

,

Rochford

PD

,

O’Donoghue

FJ

,

Pierce

RJ

,

Singh

P

,

Thornton

AT

.

The new AASM criteria for scoring hypopneas: impact on the apnea hypopnea index

.

Sleep

2009

;

32

:

150

–

157

.

Redline

S

,

Sanders

MH

,

Lind

BK

,

Quan

SF

,

Iber

C

,

Gottlieb

DJ

,

Bonekat

WH

,

Rapoport

DM

,

Smith

PL

,

Kiley

JP

;

Sleep Heart Health Research Group

.

Methods for obtaining and analyzing unattended polysomnography data for a multicenter study

.

Sleep

1998

;

21

:

759

–

767

.

EEG arousals: scoring rules and examples: a preliminary report from the Sleep Disorders Atlas Task Force of the American Sleep Disorders Association

.

Sleep

1992

;

15

:

173

–

184

.

Ohayon

MM

,

Carskadon

MA

,

Guilleminault

C

,

Vitiello

MV

.

Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan

.

Sleep

2004

;

27

:

1255

–

1273

.

Walsleben

JA

,

Kapur

VK

,

Newman

AB

,

Shahar

E

,

Bootzin

RR

,

Rosenberg

CE

,

O’Connor

G

,

Nieto

FJ

.

Sleep and reported daytime sleepiness in normal subjects: the Sleep Heart Health Study

.

Sleep

2004

;

27

:

293

–

298

.

Mitterling

T

,

Hogl

B

,

Schonwald

SV

,

Hackner

H

,

Gabelia

D

,

Frauscher

MB

.

Sleep and respiration in 100 healthy caucasian sleepers: a polysomnographic study according to American Academy of Sleep Medicine standards

.

Sleep

2015

;

38

:

867

–

875

.

Celli

BR

,

Cote

CG

,

Marin

JM

,

Casanova

C

,

Montes de Oca

M

,

Mendez

RA

,

Pinto Plata

V

,

Cabral

HJ

.

The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

.

N Engl J Med

2004

;

350

:

1005

–

1012

.

Sharma

B

,

Feinsilver

S

,

Owens

RL

,

Malhotra

A

,

McSharry

D

,

Karbowitz

S

.

Obstructive airway disease and obstructive sleep apnea: effect of pulmonary function

.

Lung

2011

;

189

:

37

–

41

.

Ballard

RD

,

Clover

CW

,

Suh

BY

.

Influence of sleep on respiratory function in emphysema

.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med

1995

;

151

:

945

–

951

.

Collop

N

.

Sleep and sleep disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

.

Respiration

2010

;

80

:

78

–

86

.

Wynne

JW

,

Block

AJ

,

Hemenway

J

,

Hunt

LA

,

Flick

MR

.

Disordered breathing and oxygen desaturation during sleep in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease (COLD)

.

Am J Med

1979

;

66

:

573

–

579

.

DeMarco

FJ

Jr,

Wynne

JW

,

Block

AJ

,

Boysen

PG

,

Taasan

VC

.

Oxygen desaturation during sleep as a determinant of the “Blue and Bloated” syndrome

.

Chest

1981

;

79

:

621

–

625

.

Cormick

W

,

Olson

LG

,

Hensley

MJ

,

Saunders

NA

.

Nocturnal hypoxaemia and quality of sleep in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease

.

Thorax

1986

;

41

:

846

–

854

.

Fletcher

EC

,

Luckett

RA

,

Miller

T

,

Costarangos

C

,

Kutka

N

,

Fletcher

JG

.

Pulmonary vascular hemodynamics in chronic lung disease patients with and without oxyhemoglobin desaturation during sleep

.

Chest

1989

;

95

:

757

–

764

.

Mills

PJ

,

Dimsdale

JE

,

Ancoli-Israel

S

,

Clausen

J

,

Loredo

JS

.

The effects of hypoxia and sleep apnea on isoproterenol sensitivity

.

Sleep

1998

;

21

:

731

–

735

.

Young

T

,

Peppard

P

.

Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: epidemiologic evidence for a relationship

.

Sleep

2000

;

23

:

S122

–

S126

.

Loredo

JS

,

Clausen

JL

,

Nelesen

RA

,

Ancoli-Israel

S

,

Ziegler

MG

,

Dimsdale

JE

.

Obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension: are peripheral chemoreceptors involved?

Med Hypotheses

2001

;

56

:

17

–

19

.

von Känel

R

,

Loredo

JS

,

Ancoli-Israel

S

,

Dimsdale

JE

.

Association between sleep apnea severity and blood coagulability: treatment effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure

.

Sleep Breath

2006

;

10

:

139

–

146

.

Krachman

S

,

Minai

OA

,

Scharf

SM

.

Sleep abnormalities and treatment in emphysema

.

Proc Am Thorac Soc

2008

;

5

:

536

–

542

.

Krachman

SL

,

Chatila

W

,

Martin

UJ

,

Permut

I

,

D’Alonzo

GE

,

Gaughan

JP

,

Sternberg

AL

,

Ciccolella

D

,

Criner

GJ

.

Physiologic correlates of sleep quality in severe emphysema

.

COPD

2011

;

8

:

182

–

188

.

Squier

SB

,

Patil

SP

,

Schneider

H

,

Kirkness

JP

,

Smith

PL

,

Schwartz

AR

.

Effect of end-expiratory lung volume on upper airway collapsibility in sleeping men and women

.

J Appl Physiol (1985)

2010

;

109

:

977

–

985

.

Peppard

PE

,

Young

T

,

Palta

M

,

Dempsey

J

,

Skatrud

J

.

Longitudinal study of moderate weight change and sleep-disordered breathing

.

JAMA

2000

;

284

:

3015

–

3021

.

Iber

C

.,

American Academy of Sleep Medicine

.

The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology, and technical specifications

.

Westchester, IL

:

American Academy of Sleep Medicine

;

2007

.

Wellman

A

,

Malhotra

A

,

Jordan

AS

,

Stevenson

KE

,

Gautam

S

,

White

DP

.

Effect of oxygen in obstructive sleep apnea: role of loop gain

.

Respir Physiol Neurobiol

2008

;

162

:

144

–

151

.

Copyright © 2015 by the American Thoracic Society