Esophageal Stricture: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology (original) (raw)

Background

Disease processes that can produce esophageal strictures can be grouped into three general categories: (1) intrinsic diseases that narrow the esophageal lumen through inflammation, fibrosis, or neoplasia; (2) extrinsic diseases that compromise the esophageal lumen by direct invasion or lymph node enlargement; and (3) diseases that disrupt esophageal peristalsis and/or lower esophageal sphincter (LES) function by their effects on esophageal smooth muscle and its innervation.

Many diseases can cause esophageal stricture formation. These include acid peptic, autoimmune, infectious, caustic, congenital, iatrogenic, medication-induced, radiation-induced, malignant, and idiopathic disease processes.

The etiology of esophageal stricture can usually be identified using radiologic and endoscopic modalities and can be confirmed by endoscopic visualization and tissue biopsy. Use of manometry can be diagnostic when dysmotility is suspected as the primary process. Computed tomography (CT) scanning and endoscopic ultrasonography are valuable aids in staging of malignant stricture. Fortunately, most benign esophageal strictures are amenable to pharmacologic, endoscopic, and/or surgical interventions.

Because peptic strictures account for 70-80% of all cases of esophageal stricture, peptic stricture is the focus of this article. A detailed discussion of possible benign and malignant processes associated with esophageal stricture and its management is beyond the scope of this article.

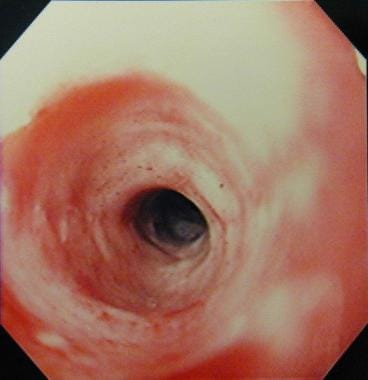

See the image below.

Esophageal stricture. Endoscopic appearance of the distal esophagus showing a smooth stricture with a benign appearance.

Pathophysiology

Peptic esophageal strictures are sequelae of gastroesophageal reflux -induced esophagitis, and they usually originate at the squamocolumnar junction and average 1-4 cm in length.

Two major factors involved in the development of a peptic esophageal stricture are as follows:

- Dysfunctional lower esophageal sphincter: Mean LES pressures are lower in patients with peptic strictures compared with healthy controls or patients with milder degrees of reflux disease. A study by Ahtaridis et al showed that patients with peptic esophageal strictures had a mean LES pressure of 4.9 mm Hg versus 20 mm Hg in control patients. [1] An LES pressure of less than 8 mm Hg appeared to correlate significantly with the presence of peptic esophageal stricture without any overlap in controls.

- Disordered motility resulting in poor esophageal clearance: In the same study, Ahtaridis et al demonstrated that 64% of patients with strictures had motility disorders compared with 32% of patients without strictures. [1]

Other possible associated factors include the following:

- Presence of a hiatal hernia: Hiatal hernias are found in 10-15% of the general population, 42% of patients with reflux symptoms and no esophagitis, 63% of patients with esophagitis, and 85% of patients with peptic esophageal strictures. This suggests that hiatal hernias may play a significant role.

- Acid and pepsin secretion: This does not appear to be a major factor. Patients with peptic esophageal strictures have been demonstrated to have the same acid and pepsin secretion rates as sex-matched and age-matched controls with esophagitis but no stricture formation. In fact, some authors believe that alkaline reflux may play an important role.

- Gastric emptying: No good evidence suggests that delayed emptying plays a role in peptic esophageal strictures.

Etiology

Proximal or mid esophageal strictures may be caused by the following:

- Caustic ingestion (acid or alkali)

- Malignancy

- Radiation therapy [2, 3]

- Infectious esophagitis -Candida, herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

- Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and immunosuppression in patients who have received a transplant

- Medication-induced stricture (pill esophagitis) - Alendronate, ferrous sulfate, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), phenytoin, potassium chloride, quinidine, tetracycline, ascorbic acid. [4] Drug-induced esophagitis often occurs at the anatomic site of narrowing, with the middle one third of the esophagus behind the left atrium predominating in 75.6% of cases. [5]

- Diseases of the skin - Pemphigus vulgaris, benign mucous membrane (cicatricial) pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa dystrophica

- Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis

- Extrinsic compression

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Sequela of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial squamous cell neoplasms. [6]

- Miscellaneous - Trauma to the esophagus from external forces, foreign body, surgical anastomosis/postoperative stricture, congenital esophageal stenosis

Distal esophageal strictures may be caused by the following

- Adenocarcinoma

- Collagen vascular disease - Scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis

- Extrinsic compression

- Alkaline reflux following gastric resection

- Sclerotherapy and prolonged nasogastric intubation

Epidemiology

United States data

Gastroesophageal reflux affects approximately 40% of adults. Esophageal strictures are estimated to occur in 7-23% of untreated patients with reflux disease.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease accounts for approximately 70-80% of all cases of esophageal stricture. Postoperative strictures account for about 10%, and corrosive strictures account for less than 5%.

The overall frequency of initial and subsequent dilations for peptic stricture appears to have decreased gradually since the introduction of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in 1989. This has been borne out by data at the author's institution and in two large community hospitals in Wisconsin. It is also in keeping with the general experience of gastroenterologists in the United States.

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

Peptic strictures are 10-fold more common in whites than blacks or Asians. However, this is controversial as a recent retrospective study reported comparable frequencies between blacks and non-Hispanic whites. [7] The authors reported that distribution of reflux esophagitis and the grade and frequency of reflux-related esophageal ulcer and hiatal hernia were also similar in non-Hispanic whites and blacks. However, heartburn was more frequent and nausea/vomiting less frequent in non-Hispanic whites compared with blacks with erosive esophagitis or its complications. [7]

Peptic strictures are 2- to 3-fold more common in men than in women.

Patients with peptic stricture tend to be older, with a longer duration of reflux symptoms.

Prognosis

Esophageal dilation

Several studies have shown that progressive dilation of peptic strictures to 40-60F resulted in effective relief of dysphagia in approximately 85% of cases, with a low rate of complications. However, 30% of patients require repeat dilation in 1 year despite optimal acid suppression therapy. This is in comparison to a 60% recurrence rate without adequate acid suppression therapy.

Poor prognostic factors include a lack of heartburn and significant weight loss at initial presentation.

The severity of the initial stenosis and the type and size of dilator used have no effect on esophageal stricture recurrence.

Surgical intervention

The outcome of surgery is highly dependent on the surgeon's experience and whether or not it is performed in high-volume centers. Most surgical series report a good-to-excellent outcome in 77% of cases, with the range being 43-90%.

The repeat dilation rate is reported to be 1-43% after surgery, requiring 1-2 sessions at most.

Mortality and morbidity rates are reported to be less than 0.5% and 20%, respectively.

Currently, no good controlled trials exist comparing the efficacy, outcome, and safety of surgery with aggressive medical management that includes PPIs and dilation as necessary.

Mortality/morbidity

The mortality rate of peptic strictures is not increased unless a procedure-related perforation occurs or the stricture is malignant. However, the morbidity for peptic strictures is significant.

Most patients undergo a chronic relapsing course with an increased risk of food impaction and pulmonary aspiration.

Frequently, coexistent Barrett esophagus and its attendant complications occur.

The need for repeated dilatations potentially increases the risk of perforation.

Complications

Complications include perforation, bleeding, and bacteremia.

Bleeding

A 1974 American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) survey estimated rates of perforation to be 0.1% and bleeding to be 0.3%. A 1984 ASGE survey estimated the overall complication rate to be 2.5%. In general, both of these complications seem to occur with equal frequency, but significant variation in published reports exists. Providing precise estimates is difficult because of flawed methodologies in the published literature. However, based on this review, one would estimate that the risk of serious complications is approximately 0.5%.

A multivariate analysis found that predictors of massive bleeding following stent placement for malignant esophageal stricture/fistulae included the presence of esophageal fistulae, previous radiotherapy, and concomitant tracheal stent. [8]

Bacteremia

Bacteremia appears to occur in approximately 20-45% of all dilations based on some reports in the literature; however, it usually is clinically insignificant, and reports of endocarditis and brain abscesses are rare. Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended in all high-risk cases as defined by the American Heart Association guidelines.

Patient Education

Consider the following:

- Reinforce the need for patients with esophageal stricture to comply with the usual antireflux precautions and lifestyle modifications.

- Encourage weight loss.

- Patients are told to eat smaller meals, avoid eating in a hurried fashion, and chew their food well.

- Ill-fitting dentures or poor dentition should be corrected if possible.

- Educate all patients with esophageal stricture about avoiding medications known to cause esophagitis, including over-the-counter medications such as aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Inform all patients that the stricture recurrence rate for esophageal stricture is higher if they are noncompliant with PPI therapy.

- Ahtaridis G, Snape WJ, Cohen S. Clinical and manometric findings in benign peptic strictures of the esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 1979 Nov. 24(11):858-61. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lawson JD, Otto K, Grist W, Johnstone PA. Frequency of esophageal stenosis after simultaneous modulated accelerated radiation therapy and chemotherapy for head and neck cancer. Am J Otolaryngol. 2008 Jan-Feb. 29(1):13-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chen AM, Li BQ, Jennelle RL, et al. Late esophageal toxicity after radiation therapy for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2010 Feb. 32(2):178-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pace F, Antinori S, Repici A. What is new in esophageal injury (infection, drug-induced, caustic, stricture, perforation)?. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009 Jul. 25(4):372-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zografos GN, Georgiadou D, Thomas D, Kaltsas G, Digalakis M. Drug-induced esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2009. 22(8):633-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ono S, Fujishiro M, Niimi K, et al. Predictors of postoperative stricture after esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial squamous cell neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2009 Aug. 41(8):661-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Vega KJ, Chisholm S, Jamal MM. Comparison of reflux esophagitis and its complications between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Jun 21. 15(23):2878-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Liu SY, Xiao P, Li TX, et al. Predictor of massive bleeding following stent placement for malignant oesophageal stricture/fistulae: a multicentre study. Clin Radiol. 2016 May. 71(5):471-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ravich WJ. Endoscopic management of benign esophageal strictures. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017 Aug 24. 19(10):50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dakkak M, Hoare RC, Maslin SC. Oesophagitis is as important as oesophageal stricture diameter in determining dysphagia. Gut. 1993 Feb. 34(2):152-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Smith PM, Kerr GD, Cockel R. A comparison of omeprazole and ranitidine in the prevention of recurrence of benign esophageal stricture. Restore Investigator Group. Gastroenterology. 1994 Nov. 107(5):1312-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Marks RD, Richter JE, Rizzo J. Omeprazole versus H2-receptor antagonists in treating patients with peptic stricture and esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1994 Apr. 106(4):907-15. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Swarbrick ET, Gough AL, Foster CS. Prevention of recurrence of oesophageal stricture, a comparison of lansoprazole and high-dose ranitidine. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996 May. 8(5):431-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Silvis SE, Farahmand M, Johnson JA. A randomized blinded comparison of omeprazole and ranitidine in the treatment of chronic esophageal stricture secondary to acid peptic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996 Mar. 43(3):216-21. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- de Wijkerslooth LR, Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD. Endoscopic management of difficult or recurrent esophageal strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Dec. 106(12):2080-91. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fan Y, Song HY, Kim JH, et al. Fluoroscopically guided balloon dilation of benign esophageal strictures: incidence of esophageal rupture and its management in 589 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011 Dec. 197(6):1481-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Al-Hussaini A. Savary dilation is safe and effective treatment for esophageal narrowing related to pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016 Nov. 63(5):474-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Yan X, Nie D, Zhang Y, Chang H, Huang Y. Effectiveness of an orally administered steroid gel at preventing restenosis after endoscopic balloon dilation of benign esophageal stricture. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Feb. 98(8):e14565. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Thyoka M, Barnacle A, Chippington S, et al. Fluoroscopic balloon dilation of esophageal atresia anastomotic strictures in children and young adults: single-center study of 103 consecutive patients from 1999 to 2011. Radiology. 2014 May. 271(2):596-601. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Uygun I, Arslan MS, Aydogdu B, Okur MH, Otcu S. Fluoroscopic balloon dilatation for caustic esophageal stricture in children: an 8-year experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2013 Nov. 48(11):2230-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Saeed ZA, Winchester CB, Ferro PS. Prospective randomized comparison of polyvinyl bougies and through-the- scope balloons for dilation of peptic strictures of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995 Mar. 41(3):189-95. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Scolapio JS, Pasha TM, Gostout CJ. A randomized prospective study comparing rigid to balloon dilators for benign esophageal strictures and rings. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999 Jul. 50(1):13-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kozarek RA, Patterson DJ, Ball TJ. Esophageal dilation can be done safely using selective fluoroscopy and single dilating sessions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995 Apr. 20(3):184-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pregun I, Hritz I, Tulassay Z, Herszenyi L. Peptic esophageal stricture: medical treatment. Dig Dis. 2009. 27(1):31-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kirsch M, Blue M, Desai RK. Intralesional steroid injections for peptic esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991 Mar-Apr. 37(2):180-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lee M, Kubik CM, Polhamus CD. Preliminary experience with endoscopic intralesional steroid injection therapy for refractory upper gastrointestinal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995 Jun. 41(6):598-601. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kochhar R, Makharia GK. Usefulness of intralesional triamcinolone in treatment of benign esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002 Dec. 56(6):829-34. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dunne DP, Rupp T, Rex DK, Lehman GA. Five year follow-up of prospective randomized trial of Savary dilation with or without intra-lesional steroids for benign gastroesophageal reflux strictures [abstract]. Gastroenterology. 1999. 116:A152.

- Ramage JI Jr, Rumalla A, Baron TH, et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of endoscopic steroid injection therapy for recalcitrant esophageal peptic strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Nov. 100(11):2419-25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hishiki T, Kouchi K, Saito T, et al. Successful treatment of severe refractory anastomotic stricture in an infant after esophageal atresia repair by endoscopic balloon dilation combined with systemic administration of dexamethasone. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009 Jun. 25(6):531-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Raijman I, Siddique I, Rachal LT. Endoscopic stricturoplasty in the management of recurrent benign esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999. 49:AB172.

- Hagiwara A, Togawa T, Yamasaki J. Endoscopic incision and balloon dilatation for cicatricial anastomotic strictures. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999 Mar-Apr. 46(26):997-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tang SJ, Singh S, Truelson JM. Endotherapy for severe and complete pharyngo-esophageal post-radiation stenosis using wires, balloons and pharyngo-esophageal puncture (PEP) (with videos). Surg Endosc. 2010 Jan. 24(1):210-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Repici A, Conio M, De Angelis C, et al. Temporary placement of an expandable polyester silicone-covered stent for treatment of refractory benign esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004 Oct. 60(4):513-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Siersema PD. Stenting for benign esophageal strictures. Endoscopy. 2009 Apr. 41(4):363-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Han Y, Liu K, Li X, et al. Repair of massive stent-induced tracheoesophageal fistula. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009 Apr. 137(4):813-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Thomson A, Baron TH. Esophageal stents: One size does not fit all. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Jan. 24(1):2-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Vandenplas Y, Hauser B, Devreker T, Urbain D, Reynaert H. A biodegradable esophageal stent in the treatment of a corrosive esophageal stenosis in a child. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 Aug. 49(2):254-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Suzuki T, Siddiqui A, Taylor LJ, et al. Clinical outcomes, efficacy, and adverse events in patients undergoing esophageal stent placement for benign indications: a large multicenter study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016 May-Jun. 50(5):373-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kim KY, Tsauo J, Song HY, et al. Evaluation of a new esophageal stent for the treatment of malignant and benign esophageal strictures. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2017 Oct. 40(10):1576-85. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dunne D, Mercer D, Paterson WG. Decreasing frequency of esophageal dilation for peptic stricture correlates with omeprazole use. Can J Gastroenterol. 1997. 11(suppl A):43A.

- Guda NM, Vakil N. Proton pump inhibitors and the time trends for esophageal dilation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 May. 99(5):797-800. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Agnew SR, Pandya SP, Reynolds RP. Predictors for frequent esophageal dilations of benign peptic strictures. Dig Dis Sci. 1996 May. 41(5):931-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Antibiotic prophylaxis for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995 Dec. 42(6):630-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Attwood SE, DeMeester TR, Bremner CG. Alkaline gastroesophageal reflux: implications in the development of complications in Barrett's columnar-lined lower esophagus. Surgery. 1989 Oct. 106(4):764-70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bell NJ, Burget D, Howden CW. Appropriate acid suppression for the management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Digestion. 1992. 51 Suppl 1:59-67. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Berenson GA, Wyllie R, Caulfield M. Intralesional steroids in the treatment of refractory esophageal strictures. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994 Feb. 18(2):250-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Botoman VA, Surawicz CM. Bacteremia with gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986 Oct. 32(5):342-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cox JG, Winter RK, Maslin SC. Balloon or bougie for dilatation of benign oesophageal stricture? An interim report of a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 1988 Dec. 29(12):1741-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Dajani AS, Taubert KA, Wilson W, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. Recommendations by the American Heart Association. JAMA. 1997 Jun 11. 277(22):1794-801. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Graham DY, Saeed ZA. Guidewire-assisted esophageal dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991 Nov-Dec. 37(6):650-1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Heller SR, Fellows IW, Ogilvie AL. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and benign oesophageal stricture. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982 Jul 17. 285(6336):167-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kadakia SC, Parker A, Carrougher JG. Esophageal dilation with polyvinyl bougies, using a marked guidewire without the aid of fluoroscopy: an update. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993 Sep. 88(9):1381-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kuo WH, Kalloo AN. Reflux strictures of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1998 Apr. 8(2):273-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mamazza J, Schlachta CM, Poulin EC. Surgery for peptic strictures. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1998 Apr. 8(2):399-413. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Marks RD, Richter JE. Peptic strictures of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993 Aug. 88(8):1160-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Marks RD, Shukla M. Diagnosis and management of peptic esophageal strictures. Gastroenterologist. 1996 Dec. 4(4):223-37. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Meyer GW. Endocarditis prophylaxis for esophageal dilation: a confusing issue?. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998 Dec. 48(6):641-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ott DJ, Gelfand DW, Lane TG. Radiologic detection and spectrum of appearances of peptic esophageal strictures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1982 Feb. 4(1):11-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Patterson DJ, Graham DY, Smith JL. Natural history of benign esophageal stricture treated by dilatation. Gastroenterology. 1983 Aug. 85(2):346-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pungpapong S, Raimondo M, Wallace MB, Woodward TA. Problematic esophageal stricture: an emerging indication for self-expandable silicone stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004 Nov. 60(5):842-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Richter JE. Peptic strictures of the esophagus. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1999 Dec. 28(4):875-91, vi. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Spechler SJ. AGA technical review on treatment of patients with dysphagia caused by benign disorders of the distal esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1999 Jul. 117(1):233-54. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Spechler SJ. American gastroenterological association medical position statement on treatment of patients with dysphagia caused by benign disorders of the distal esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1999 Jul. 117(1):229-33. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Spechler SJ. Comparison of medical and surgical therapy for complicated gastroesophageal reflux disease in veterans. The Department of Veterans Affairs Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1992 Mar 19. 326(12):786-92. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Vandenplas Y, Hauser B, Devreker T, Urbain D, Reynaert H. A degradable esophageal stent in the treatment of a corrosive esophageal stenosis in a child. Endoscopy. 2009. 41 Suppl 2:E73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Vollan G, Stangeland L, Soreide JA. Long term results after Nissen fundoplication and Belsey Mark IV operation in patients with reflux oesophagitis and stricture. Eur J Surg. 1992 Jun-Jul. 158(6-7):357-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Wilcox CM, Alexander LN, Clark WS. Localization of an obstructing esophageal lesion. Is the patient accurate?. Dig Dis Sci. 1995 Oct. 40(10):2192-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Wilkins WE, Ridley MG, Pozniak AL. Benign stricture of the oesophagus: role of non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs. Gut. 1984 May. 25(5):478-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zein NN, Greseth JM, Perrault J. Endoscopic intralesional steroid injections in the management of refractory esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995 Jun. 41(6):596-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Author

Specialty Editor Board

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Received salary from Medscape for employment. for: Medscape.

Chief Editor

Additional Contributors

Maurice A Cerulli, MD, FACP, FACG, FASGE, AGAF Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University; Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Hofstra Medical School

Maurice A Cerulli, MD, FACP, FACG, FASGE, AGAF is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, American College of Physicians, New York Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, American Gastroenterological Association, American Medical Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Sandeep Mukherjee, MB, BCh, MPH, FRCPC Associate Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Nebraska Medical Center; Consulting Staff, Section of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Veteran Affairs Medical Center

Disclosure: Merck Honoraria Speaking and teaching; Ikaria Pharmaceuticals Honoraria Board membership

Rajeev Vasudeva, MD, FACG Clinical Professor of Medicine, Consultants in Gastroenterology, University of South Carolina School of Medicine

Rajeev Vasudeva, MD, FACG is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Columbia Medical Society, South Carolina Gastroenterology Association, and South Carolina Medical Association

Disclosure: Pricara Honoraria Speaking and teaching; UCB Consulting fee Consulting