Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): Background, Indications, Contraindications (original) (raw)

Overview

Background

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is a technique that uses a combination of luminal endoscopy and fluoroscopic imaging to diagnose and treat conditions associated with the pancreatobiliary system. The endoscopic portion of the examination uses a side-viewing duodenoscope that is passed through the esophagus and stomach and into the second portion of the duodenum. (See Technique.)

With the scope in this position, the major duodenal papilla is identified and inspected for abnormalities. This structure is a protrusion of the hepatopancreatic ampulla (also known as the ampulla of Vater) into the duodenal lumen. The ampulla is the convergence point of the ventral pancreatic duct and the common bile duct (CBD) and thus acts as a conduit for drainage of bile and pancreatic secretions into the duodenum.

The minor duodenal papilla is also located in the second portion of the duodenum and serves as the access point for the dorsal pancreatic duct. Evaluation of the dorsal pancreatic duct with ERCP is rarely performed; indications are discussed below.

After the papilla has been examined with the side-viewing endoscope, selective cannulation of either the CBD or the ventral pancreatic duct is performed. Once the chosen duct is cannulated, either a cholangiogram (CBD) or a pancreatogram (pancreatic duct) is obtained fluoroscopically after injection of radiopaque contrast material into the duct. ERCP is now primarily a therapeutic procedure; thus, abnormalities that are visualized fluoroscopically can typically be addressed by means of specialized accessories passed through the working channel of the endoscope.

Because ERCP is an advanced technique, it is associated with a higher frequency of serious complications than other endoscopic procedures are. [1, 2] Accordingly, specialized training and equipment are required, and the procedure should be reserved for appropriate indications.

A review by Freeman et al, using data from 2004, estimated that about 500,000 procedures were performed annually in the United States. [3] However, because of a decrease in diagnostic ERCP with the advent of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), this number is likely decreasing.

Indications

Since its first description in the late 1960s as a diagnostic technique, [4] ERCP has evolved into an almost exclusively therapeutic procedure. The main reason for this evolution is that diagnostic modalities have been developed that are less invasive than ERCP but possess similar sensitivity and specificity for disease processes of the hepatobiliary system. [5]

Imaging techniques currently used in the diagnosis of hepatobiliary processes include computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography (US), EUS, and MRCP. The use of these modalities, in conjunction with pertinent clinical information (eg, the clinical history, physical examination findings, and laboratory data), can help select those patients for whom ERCP is most appropriate.

Because ERCP has a higher rate of severe complications than most other endoscopic procedures do, having an appropriate indication for its use is extremely important. In fact, most ERCP-related legal claims center on the aptness of the indication for the procedure. [6]

In 2005, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) published guidelines regarding the role of ERCP in biliary tract and pancreatic diseases. [7] The guidelines were updated in 2015 to include the following recommendations for benign biliary tract disease [8] :

- Diagnostic ERCP should not be undertaken to evaluate pancreaticobiliary-type pain in the absence of objective abnormalities on other pancreaticobiliary imaging or laboratory studies (moderate-quality evidence)

- Routine ERCP before laparoscopic cholecystectomy is contraindicated if there are no objective signs of biliary obstruction or stone (moderate-quality evidence)

- In patients with acute biliary pancreatitis, ERCP should be reserved for those with concomitant cholangitis or biliary obstruction (high-quality evidence)

- ERCP with dilation and stent placement is recommended for benign biliary strictures (moderate-quality evidence)

- ERCP should be performed as first-line therapy for postoperative biliary leakage (high-quality evidence)

- Cholangioscopy should be considered as an adjunct in the management of difficult bile duct stones that are not amenable to removal after sphincterotomy with or without balloon dilation or mechanical lithotripsy (low-quality evidence)

- Cholangioscopy with directed biopsy should be considered as an adjunct for characterizing biliary strictures (low-quality evidence)

- ERCP with sphincterotomy is recommended for patients with type I sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD; moderate-quality evidence)

- ERCP is not recommended for evaluation or treatment of type III SOD (high-quality evidence)

- Rectal indomethacin with or without pancreatic stenting is recommended for prophylaxis against post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) when ERCP is performed in the setting of suspected SOD (moderate-quality evidence)

In June 2019, the ASGE issued a guideline for the use of ERCP in the evaluation and management of choledocholithiasis, [9] which included the following recommendations:

- In patients with gallstone pancreatitis without cholangitis or biliary obstruction/choledocholithiasis, urgent (< 48 hr) ERCP is not recommended.

- In patients with large choledocholithiasis, large-balloon dilation after sphincterotomy is suggested rather than endoscopic sphincterotomy alone.

- For patients with large and difficult choledocholithiasis, intraductal therapy or conventional therapy with papillary dilation is suggested.

- Same-admission cholecystectomy is recommended for patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis.

- To minimize the risk of diagnostic ERCP, the following high-risk criteria are suggested to directly prompt ERCP for suspected choledocholithiasis:(1) CBD stone on US or cross-sectional imaging or (2) total bilirubin >4 mg/dL and dilated CBD on imaging (>6 mm with gallbladder in situ) or (3) ascending cholangitis. In patients with intermediate-risk criteria—abnormal liver tests or age >55 years or dilated CBD on US—EUS, MRCP, laparoscopic intraoperative cholangiography (IOC), or laparoscopic intraoperative US is suggested for further evaluation. For patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis without any of these risk factors, cholecystecomy without IOC is suggested.

- Preoperative or postoperative ERCP or laparoscopic treatment is suggested for patients at high risk of choledocholithiasis or positive intraoperative cholangiopancreatography, depending on local surgical and endoscopic expertise.

- For patients with Mirizzi syndrome, per-oral cholangioscopic therapy may be an alternative to surgical management, depending on local expertise; however, gallbladder resection is needed regardless of strategy. For hepatolithiasis, a multidisciplinary approach that includes endoscopy, interventional radiology, and surgery is suggested.

- Plastic and covered metal stents may facilitate removal of difficult choledocholithiasis but require planned exchange or removal.

In February 2023, the ASGE issued a guideline on management of post–liver transplant biliary strictures, [10] which included the following suggestions:

- In patients with post-transplant biliary strictures, ERCP is suggested as the initial intervention and a covered self-expandable metal stent as the preferred stent for extrahepatic strictures

- In patients with unclear diagnoses or intermediate probability of a stricture, MRCP is suggested as the diagnostic modality

- Antibiotic administration during ERCP is suggested when biliary drainage cannot be ensured

Indications for benign pancreatic disease in the 2015 ASGE guidelines included the following [11] :

- Evaluation of idiopathic acute recurrent pancreatitis (suspected type 2 pancreatic SOD) when findings on EUS or MRCP are normal and not suspicious for biliary stones, sludge, or chronic pancreatitis; ERCP with empiric biliary or pancreatic sphincterotomy is an alternative

- Biliary and/or pancreatic sphincterotomy is recommended for type 1 pancreatic SOD or type 2 pancreatic SOD confirmed by manometry

- Rectal indomethacin and/or pancreatic duct stenting is recommended for prevention of PEP in high-risk patients

- Treatment (with dilation or stent placement) of symptomatic dominant pancreatic duct strictures

- Pancreatic duct leakage

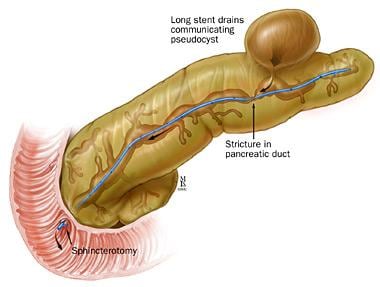

ERCP may also be indicated for treatment of symptomatic pancreatic pseudocysts (see the image below) or benign pancreatic fluid collections. [12]

Pancreatic stent placement for pseudocyst drainage. Used with permission from the Johns Hopkins Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (www.hopkinsmedicine.org/gi). Illustration Copyright© 1998-2003 by The Johns Hopkins Health System Corporation and The Johns Hopkins University. Illustration created by Mike Linkinhoker.

Indications for diagnosis of pancreatic malignancies include the following [13] :

- Pancreatoscopy

- Bile duct brushing and biopsy

- Intraductal US

- Diagnosis and characterization of suspected main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) [14]

Indications for ampullary disease include the following:

- Assessment and treatment of ampullary adenomas [15]

- Assessment of ampullary malignancy

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications for ERCP include the following:

- Patient refusal to undergo the procedure

- Unstable cardiopulmonary, neurologic, or cardiovascular status

- Existing bowel perforation

Structural abnormalities of the esophagus, stomach, or small intestine may be relative contraindications for ERCP. Examples are acquired conditions such as esophageal stricture, paraesophageal herniation, esophageal diverticulum, gastric volvulus, gastric outlet obstruction, and small-bowel obstruction. An altered surgical anatomy, such as is seen after partial gastrectomy with Billroth II or Roux-en-Y jejunostomy, may also be a relative contraindication for ERCP.

Several factors play a role in choosing the best approach for ERCP access in patients with altered surgical anatomy in cases where ERCP is indeed indicated. These factors include long versus short Roux limb, native papilla versus bilioenteric anastomosis, prior sphincterotomy, anticipated accessory use (eg, sphincter of Oddi manometry), surgical risk, likelihood of repeat procedures, and possibility of internal hernias.

The different approaches in patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy include the following [16, 17] :

- Duodenoscope through the anatomic route

- Colonoscope or enteroscope through the anatomic route

- Single- or double-balloon enteroscope

- Spiral/rotational enteroscope

- ERCP through gastrostomy or jejunostomy

- Laparoscopically assisted ERCP

- Biliary access obtained by interventional radiology

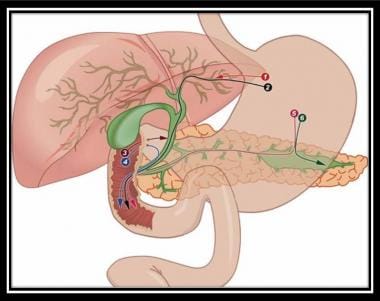

EUS-guided biliary access has been described in cases of difficult primary cannulation of a native papilla or in the appropriate setting with altered surgical anatomy. [18] (See the image below.)

Endosonography-guided cholangiopancreatography. Used with permission from Baishideng Publishing Group, Inc (Fig 1 from Perez-Miranda M, de la Serna C, Diez-Redondo P, Vila JJ. Endosonography-guided cholangiopancreatography as a salvage drainage procedure for obstructed biliary and pancreatic ducts. World J Gastrointest Endosc. Jun 16 2010;2(6):212-22).

The presence of acute pancreatitis is typically considered a relative contraindication as well, unless the etiology of the pancreatitis is gallstone-related and the therapeutic goal is to improve the clinical course by means of stone extraction. [19, 20] In addition, ERCP with sphincterotomy or ampullectomy is relatively contraindicated in coagulopathic patients (international normalized ratio [INR] >1.5 or platelet count < 50,000/µL).

Technical Considerations

Best practices

Before ERCP, all of the patient’s previous abdominal imaging findings (from CT, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], US, and cholangiography or pancreatography) should be reviewed; this can facilitate location of the pathology during ERCP, as well as help pinpoint any changes that occurred since the previous imaging was performed.

A scout radiograph should be obtained while the patient is on the fluoroscopy table and before insertion of the duodenoscope; this image can act as a baseline for comparison with subsequent fluoroscopic images taken after contrast injection.

The patient's surgical history should be reviewed before the procedure to determine whether there is anything in the surgical anatomy that may be a contraindication for ERCP.

To minimize the patient's exposure to radiation, fluoroscopic images should be obtained only as necessary during the procedure; some fluoroscopy machines can be adjusted to minimize the frequency of image acquisition.

Deep sedation is desirable during ERCP because a stable endoscopic position in the duodenum is important for proper cannulation, therapeutic intervention, and avoidance of complications.

If the pancreatic duct is cannulated several times or if contrast is injected into the pancreatic duct, placement of a temporary pancreatic duct stent or rectally administered nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; eg, indomethacin or diclofenac) should be considered in order to decrease the risk of PEP. [21] These two prevention modalities have proved effective for PEP prophylaxis. Numerous other pharmacologic agents have been studied, including gabexate, somatostatin, octreotide, steroids, heparin, allopurinol, and nitroglycerin, but with disappointing results. [22]

Multiple randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have shown rectally administered NSAIDs to be effective in reducing the incidence of PEP, the occurrence of moderate-to-severe pancreatitis, and the length of hospital stay in high-risk patients who develop PEP. [23, 24, 22, 25, 21] Indirect comparative effectiveness studies suggested that rectal NSAIDs alone may be superior to pancreatic duct stenting in preventing PEP as a simple, easily administered, safe, inexpensive, and effective treatment modality, [25] but there remains a need for further studies to help confirm these results through direct comparison with prospective randomized controlled data.

Whether rectal NSAIDs should be given to all patients or employed selectively in high-risk patients is a topic of debate among experts. Widespread adoption of this simple strategy may minimize the incidence of PEP and modulate its severity, resulting in major clinical and economic benefit. [22, 21] NSAIDs have been shown to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, phospholipase A2 activity, and neutrophil/endothelial cell attachment, which are all believed to play a key role in the pathogenesis of the initial inflammatory cascade of acute pancreatitis. [23, 26, 27, 22]

Single-dose administration is not associated with enhanced risk of bleeding or renal insufficiency. Rectal administration seems to work better than other routes, including oral, intramuscular (IM), intravenous (IV), and intraduodenal. [22]

In a prospective randomized study (N = 162) designed to compare the efficacy of single-dose (n = 87) and double-dose (n = 75) rectal indomethacin administration for preventing PEP, Lai found that although the incidence of PEP was lower in the latter group, the difference was not significant. [28] They concluded that in the general population, single-dose rectal indomethacin immediately after ERCP is sufficient for prevention, but they noted that in cases of difficult cannulation, the incidence of PEP frequency may rise as high as 15.4% even when rectal indomethacin is used.

The optimal timing of administering rectal NSAIDs has not been clearly defined. Two meta-analyses found no difference in efficacy between giving the medication before the procedure and giving it immediately afterward. [22, 21]

A pilot study suggested that aggressive IV hydration with lactated Ringer (LR) solution may reduce the development of PEP and is not associated with volume overload. [29]

In a subsequent prospective randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 192 patients at high risk for PEP received standard normal saline solution (NS) plus placebo (n = 48), NS plus indomethacin (n = 48), LR solution plus placebo (n = 48), or LR solution plus indomethacin (n = 48). [30] The primary outcome was PEP; secondary outcomes were severe acute pancreatitis, localized adverse events, death, length of stay, and readmission. The combination of LR solution and indomethacin led to reductions in PEP incidence and readmission rate as compared with the combination of NS and placebo.

Complication prevention

The first step in preventing post-ERCP complications is to identify those patients who are most likely to experience adverse events. [1] Factors that place patients at higher risk for PEP, the most common serious complication associated with this procedure, may be broadly grouped as follows:

- Patient-related factors

- Procedure-related factors

- Operator-dependent factors

- Underlying disease or indication for performing ERCP

It is important to distinguish between asymptomatic postprocedural pancreatic enzyme elevations of serum amylase and lipase, which can be seen in more than half of all patients undergoing ERCP in the first 24 hours after the procedure, and true clinical pancreatitis induced by the ERCP, which presents with pancreatic-type pain or cross-sectional imaging confirming inflammation. [27]

Proposed underlying mechanisms that can induce PEP include the following [23, 27] :

- Thermal injury from electrocautery

- Hydrostatic injury from overinjection of the pancreatic duct

- Enzymatic injury from intestinal contents or contrast

- Mechanical injury from prolonged manipulation around the papillary orifice causing edema

Patient-related factors include the following [23, 26, 27, 31] :

- Younger age (< 50 y)

- Female sex

- History of acute or recurrent pancreatitis

- History of PEP

- Preexisting biliary-type pain

- Presence of bile duct stones

- Normal serum bilirubin

- Documented or suspected SOD (especially type III dysfunction with normal bile duct size and normal liver tests)

The term SOD is used to define motility abnormalities caused by stenosis or dyskinesia of the sphincter of Oddi. [23] A history of chronic calcific pancreatitis seems to confer a protective effect on the risk of developing PEP. [27]

Procedure-specific risk factors for PEP include the following [23, 25, 26, 27, 32] :

- Difficult cannulation of the ampulla of Vater (>10 attempts)

- Cannulation of the pancreatic duct

- Injection of contrast into the pancreatic duct (>2 times)

- Pancreatic duct sphincterotomy

- Pancreatic acinarization (opacification of acini)

- Pancreatic duct tissue sampling/brushing

- Pneumatic dilation of an intact biliary sphincter

- Precut sphincterotomy

- Ampullectomy

Data support the use of prophylactic pancreatic duct stents or the administration of rectal NSAIDs in patients at increased risk for pancreatitis, because such measures have been shown to reduce the incidence of PEP in this high-risk cohort of patients. [33, 23, 26, 27, 24, 22, 25]

A meta-analysis by Yang et al found that in patients treated for benign biliary strictures with stenting, self-expandable metallic stents caused a significantly higher incidence of PEP than multiple plastic stents ( though fewer ERCP procedures) but that the two stent types did not differ significantly with respect to rate of stricture resolution, recurrence, or overall adverse events. [34]

Operator-dependent factors include the following:

- Low case volume

- Lack of experience

- Lack of good technique

The significance of low case volume in this setting was challenged by a multicenter prospective study showing that the risk of PEP was not associated with the case volume of either the single endoscopist or the center. [32]

Those at higher risk for post-ERCP hemorrhage include patients with either a pathologic or an iatrogenic coagulopathy. Anticoagulant or antithrombotic therapy should be discontinued before elective ERCP (generally 5-7 days beforehand), and the prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) should be evaluated on the day of the procedure. If the PT and PTT are significantly abnormal, the procedure should be rescheduled if it is not an emergency. If there is an urgent need for ERCP, reversal of the coagulopathy with fresh frozen plasma may be required.

Routine use of prophylactic antibiotics in elective ERCP is controversial. The infectious risks of ERCP (ie, bacteremia and cholangitis) are most likely to occur in patients who present with biliary obstruction.

The 2015 ASGE guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis for gastrointestinal endoscopy recommended antibiotic therapy in all patients presenting with bile duct obstruction and acute cholangitis. [35] They also recommended antibiotics in cases where drainage with ERCP is incomplete or is achieved with difficulty (eg, in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma and primary sclerosing cholangitis).

A Cochrane analysis of nine randomized clinical trials found that the rates of bacteremia and cholangitis were lower in patients who received prophylactic antibiotics before elective ERCP than in those who did not, though subgroup analysis demonstrated that the effect of antibiotics was less evident in patients who underwent uncomplicated ERCP with successful biliary drainage. [36]

In March 2015, the American Gastroenterological Association suggested the following recommendations for reducing endoscope-associated infections in ERCP [37] :

- Treat all elevator-channel endoscopes the same, including both fine-needle aspiration (FNA) echoendoscopes (endoscopic ultrasound) and duodenoscopes

- Track elevator-channel endoscopes by patient and by device serial number to facilitate retrospective identification in case of infection

- Use a two-phase infection surveillance program that tracks all patients who have had a procedure with an elevator-channel endoscope, and periodically collect culture surveillance of all elevator-channel endoscopes; a positive culture should trigger a review of reprocessing techniques

- Use a standard device reprocessing training program, and require reprocessing staff to demonstrate competency every 6 months

- Immediately contact the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to aid in investigation of any suspected breach or infection

Most mucosal perforations occurring during ERCP are periampullary and are associated with sphincterotomy. Periampullary perforations are usually retroperitoneal and can often be managed with supportive care rather than immediate surgical intervention. This complication can be prevented in many cases by following proper landmarks while performing sphincterotomy and by taking care to not cut beyond the intraduodenal portion of the CBD.

Perforations occurring away from the ampulla are typically due to traumatic endoscope passage, often related to limited visualization of the lumen.

As a general rule, the duodenoscope should never be forced against significant resistance during insertion. The forceps elevator should be in the closed position during passage of the endoscope down the lumen because it may lacerate the adjacent tissue if left in the open position.

Outcomes

Because of inherent bias and patient underreporting, an accurate estimate of the procedural complication rate is difficult to obtain. However, comparisons with complication data pertaining to other endoscopic procedures makes it clear that ERCP is associated with approximately fourfold higher rates of severe complications. [38]

In a study of post-ERCP complications that pooled prospective patient survey data from almost 17,000 patients undergoing the procedure, ERCP-related morbidity secondary to pancreatitis, bleeding, perforations, and infections was 6.85%, of which 5.17% was graded as mild-to-moderate and 1.67% as severe; ERCP-specific mortality was 0.33%. [39] Pancreatitis was the most common complication (3.47% of patients), followed by infection (1.44%), bleeding (1.34%), and perforations (0.6%).

The incidence of PEP ranges from 1% to 10% in average-risk patients but can exceed 25-30% in certain high-risk patient populations. This wide range is due to the heterogenous interplay of multiple patient-, procedure-, and operator-related factors. [26] Acute PEP is not a uniform disorder and varies in intensity. Most cases are mild and resolve with proper treatment without any permanent sequelae. [27]

The relatively high risk associated with ERCP underscores the importance of having this procedure performed by experienced practitioners. [2] It also helps explain the trend toward therapeutic as opposed to diagnostic ERCP. Although the absolute complication risk is greater with therapeutic ERCP than with diagnostic ERCP, the potential benefits are also greater, and the risk-to-benefit ratio favors therapeutic ERCP. [40, 41, 42, 31]

ERCP has not been as thoroughly studied in infants and children as it has in adults, though some reports have suggested its safety in this context. In a retrospective series of 244 procedures performed in 158 patients younger than 18 years (including 56 procedures in 53 infants [< 1 y]), Åvitsland et al noted only two cases of infection and no instances of PEP in infants; in older children (>1 y), the incidence of PEP was 10.4%. [43]

- [Guideline] ASGE Standards of Practice Committee., Chandrasekhara V, Khashab MA, Muthusamy VR, Acosta RD, Agrawal D, et al. Adverse events associated with ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017 Jan. 85 (1):32-47. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- García-Cano J. Fewer endoscopists should perform more ERCPs. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2023 Feb 22. 115:[QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Freeman ML, Guda NM. Prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a comprehensive review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004 Jun. 59 (7):845-64. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- McCune WS, Shorb PE, Moscovitz H. Endoscopic cannulation of the ampulla of vater: a preliminary report. Ann Surg. 1968 May. 167 (5):752-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cohen S, Bacon BR, Berlin JA, Fleischer D, Hecht GA, Loehrer PJ Sr, et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: ERCP for diagnosis and therapy, January 14-16, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002 Dec. 56 (6):803-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cotton PB. Analysis of 59 ERCP lawsuits; mainly about indications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006 Mar. 63 (3):378-82; quiz 464. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Adler DG, Baron TH, Davila RE, Egan J, Hirota WK, Leighton JA, et al. ASGE guideline: the role of ERCP in diseases of the biliary tract and the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005 Jul. 62 (1):1-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] ASGE Standards of Practice Committee., Chathadi KV, Chandrasekhara V, Acosta RD, et al. The role of ERCP in benign diseases of the biliary tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Apr. 81 (4):795-803. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] ASGE Standards of Practice Committee., Buxbaum JL, Abbas Fehmi SM, Sultan S, Fishman DS, Qumseya BJ, et al. ASGE guideline on the role of endoscopy in the evaluation and management of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019 Jun. 89 (6):1075-1105.e15. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Kohli DR, Amateau SK, Desai M, Chinnakotla S, Harrison ME, Chalhoub JM, et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on management of post-liver transplant biliary strictures: summary and recommendations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023 Feb 14. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] ASGE Standards of Practice Committee., Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Acosta RD, Decker GA, Early DS, et al. The role of endoscopy in benign pancreatic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Aug. 82 (2):203-14. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] ASGE Standards of Practice Committee., Muthusamy VR, Chandrasekhara V, Acosta RD, et al. The role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory pancreatic fluid collections. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Mar. 83 (3):481-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] ASGE Standards of Practice Committee., Eloubeidi MA, Decker GA, Chandrasekhara V, et al. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation and management of patients with solid pancreatic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Jan. 83 (1):17-28. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] ASGE Standards of Practice Committee., Muthusamy VR, Chandrasekhara V, Acosta RD, et al. The role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of cystic pancreatic neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Jul. 84 (1):1-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] ASGE Standards of Practice Committee., Chathadi KV, Khashab MA, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Eloubeidi MA, et al. The role of endoscopy in ampullary and duodenal adenomas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Nov. 82 (5):773-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lopes TL, Wilcox CM. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010 Mar. 39 (1):99-107. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Samarasena JB, Nguyen NT, Lee JG. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with roux-en-Y anatomy. J Interv Gastroenterol. 2012 Apr. 2 (2):78-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Baron TH, Kozarek RA, Carr-Locke DL. ERCP. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2019.

- Karaliotas CC, Broelsch CE, Habib NA, eds. Liver and Biliary Tract Surgery: Embryological Anatomy to 3D-Imaging and Transplant Innovations. New York: Springer-Verlag/Wein; 2006. 90.

- Boumitri C, Kumta NA, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Wallace MB, Fockens P, Sung JJY, eds. Gastroenterological Endoscopy. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme; 2018. Chap 16.

- Puig I, Calvet X, Baylina M, Isava Á, Sort P, Llaó J, et al. How and when should NSAIDs be used for preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014. 9 (3):e92922. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Ding X, Chen M, Huang S, Zhang S, Zou X. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Dec. 76 (6):1152-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tammaro S, Caruso R, Pallone F, Monteleone G. Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography pancreatitis: is time for a new preventive approach?. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Sep 14. 18 (34):4635-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Elmunzer BJ, Scheiman JM, Lehman GA, Chak A, Mosler P, Higgins PD, et al. A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2012 Apr 12. 366 (15):1414-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Akbar A, Abu Dayyeh BK, Baron TH, Wang Z, Altayar O, Murad MH. Rectal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are superior to pancreatic duct stents in preventing pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a network meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Jul. 11 (7):778-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yang D, Draganov PV. Indomethacin for post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis prophylaxis: is it the magic bullet?. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Aug 21. 18 (31):4082-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Parsi MA. NSAIDs for prevention of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: ready for prime time?. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Aug 14. 18 (30):3936-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lai JH, Hung CY, Chu CH, Chen CJ, Lin HH, Lin HJ, et al. A randomized trial comparing the efficacy of single-dose and double-dose administration of rectal indomethacin in preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 May. 98 (20):e15742. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Buxbaum J, Yan A, Yeh K, Lane C, Nguyen N, Laine L. Aggressive hydration with lactated Ringer's solution reduces pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Feb. 12 (2):303-7.e1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mok SRS, Ho HC, Shah P, Patel M, Gaughan JP, Elfant AB. Lactated Ringer's solution in combination with rectal indomethacin for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis and readmission: a prospective randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017 May. 85 (5):1005-1013. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee., Anderson MA, Fisher L, Jain R, Evans JA, Appalaneni V, et al. Complications of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Mar. 75 (3):467-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Testoni PA, Mariani A, Giussani A, Vailati C, Masci E, Macarri G, et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis in high- and low-volume centers and among expert and non-expert operators: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Aug. 105 (8):1753-61. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fazel A, Quadri A, Catalano MF, Meyerson SM, Geenen JE. Does a pancreatic duct stent prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis? A prospective randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003 Mar. 57 (3):291-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yang H, Yang Z, Hong J. Post-ERCP pancreatitis occurs more frequently in self-expandable metallic stents than multiple plastic stents on benign biliary strictures: a meta-analysis. Ann Med. 2022 Dec. 54 (1):2439-2449. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] ASGE Standards of Practice Committee., Khashab MA, Chithadi KV, Acosta RD, Bruining DH, Chandrasekhara V, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Jan. 81 (1):81-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Brand M, Bizos D, O'Farrell P Jr. Antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing elective endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Oct 6. 10:CD007345. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- How to stop duodenoscope infections. American Gastroenterological Association. Available at https://www.gastro.org/press-release/how-to-stop-duodenoscope-infections. March 23, 2015; Accessed: February 23, 2023.

- Sieg A, Hachmoeller-Eisenbach U, Eisenbach T. Prospective evaluation of complications in outpatient GI endoscopy: a survey among German gastroenterologists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001 May. 53 (6):620-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Andriulli A, Loperfido S, Napolitano G, Niro G, Valvano MR, Spirito F, et al. Incidence rates of post-ERCP complications: a systematic survey of prospective studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Aug. 102 (8):1781-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, Chilovi F, Costan F, De Berardinis F, et al. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998 Jul. 48 (1):1-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Enestvedt BK, Tofani C, Lee DY, Abraham M, Shah P, Chandrasekhara V, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the pediatric population is safe and efficacious. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Nov. 57 (5):649-54. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Glomsaker TB, Hoff G, Kvaløy JT, Søreide K, Aabakken L, Søreide JA, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a prospective, multicentre study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013 Jul. 48 (7):868-76. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Åvitsland TL, Aabakken L. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in infants and children. Endosc Int Open. 2021 Mar. 9 (3):E292-E296. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Yao W, Huang Y, Chang H, Li K, Huang X. Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Using a Dual-Lumen Endogastroscope for Patients with Billroth II Gastrectomy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013. 2013:146867. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lagström R, Knuhtsen S, Stigaard T, Bulut M. ERCP with single-use disposable duodenoscopes in four different set-ups. BMJ Case Rep. 2023 Feb 22. 16 (2):[QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Draganov PV, Forsmark CE. Prospective evaluation of adverse reactions to iodine-containing contrast media after ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008 Dec. 68 (6):1098-101. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Garg MS, Patel P, Blackwood M, Munigala S, Thakkar P, Field J, et al. Ocular Radiation Threshold Projection Based off of Fluoroscopy Time During ERCP. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 May. 112 (5):716-721. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Güitrón-Cantú A, Adalid-Martínez R, Gutiérrez-Bermúdez JA, Segura-López FK, García Vázquez A. [Does the use of fentanyl make Vater's ampulla cannulation difficult? A prospective and comparative study]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2010. 75 (2):142-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schilling D, Rosenbaum A, Schweizer S, Richter H, Rumstadt B. Sedation with propofol for interventional endoscopy by trained nurses in high-risk octogenarians: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Endoscopy. 2009 Apr. 41 (4):295-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cheung J, Tsoi KK, Quan WL, Lau JY, Sung JJ. Guidewire versus conventional contrast cannulation of the common bile duct for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009 Dec. 70 (6):1211-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tse F, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P, Leontiadis GI. Guide wire-assisted cannulation for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2013 Aug. 45 (8):605-18. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tyagi P, Sharma P, Sharma BC, Puri AS. Periampullary diverticula and technical success of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Surg Endosc. 2009 Jun. 23 (6):1342-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996 Sep 26. 335 (13):909-18. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cotton PB, Garrow DA, Gallagher J, Romagnuolo J. Risk factors for complications after ERCP: a multivariate analysis of 11,497 procedures over 12 years. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009 Jul. 70 (1):80-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Aliperti G. Complications related to diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996 Apr. 6 (2):379-407. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kwon CI, Song SH, Hahm KB, Ko KH. Unusual complications related to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and its endoscopic treatment. Clin Endosc. 2013 May. 46 (3):251-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Sperna Weiland CJ, Engels MML, Poen AC, Bhalla A, Venneman NG, van Hooft JE, et al. Increased Use of Prophylactic Measures in Preventing Post-Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Dec. 66 (12):4457-4466. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Deng F, Zhou M, Liu PP, Hong JB, Li GH, Zhou XJ, et al. Causes associated with recurrent choledocholithiasis following therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A large sample sized retrospective study. World J Clin Cases. 2019 May 6. 7 (9):1028-1037. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Zhang Y, Gong Z, Chen S. Clinical application of enhanced recovery after surgery in the treatment of choledocholithiasis by ERCP. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Feb 26. 100 (8):e24730. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- View of duodenoscope tip. Note that elevator is in closed position and is obscuring instrument channel from view.

- Fluoroscopy table and dual-screen procedure monitors.

- Sphincterotome in bowed position.

- Two different sizes of biliary stone baskets.

- Biliary stricture–dilating balloon catheter.

- Prone position.

- Semiprone position.

- Supine position.

- Endoscopic view of major duodenal papilla.

- Cholangiogram. Note (a) duodenoscope positioned in duodenum with tip at distal aspect of common bile duct and (b) moderately dilated bile duct.

- Biliary stents. Upper stent is plastic stent; lower stent is self-expanding metal stent (SEMS).

- Fluoroscopic image of plastic stent in bile duct. Also note guide wire adjacent to stent in bile duct.

- This video, captured via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, shows side-viewing duodenoscope being inserted and advanced into stomach and duodenum. Scope is then reduced into short position, bringing ampulla into view. Video courtesy of Dawn Sears, MD, and Dan C Cohen, MD, Division of Gastroenterology, Scott & White Healthcare.

- This video, captured via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, shows engagement and cannulation of ampulla using biliary cannulation catheter. Video courtesy of Dawn Sears, MD, and Dan C Cohen, MD, Division of Gastroenterology, Scott & White Healthcare.

- This video, captured via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, shows sphincterotomy being performed. Sphincter of Oddi is being cut by using electrocautery applied to biliary cannulation catheter. Video courtesy of Dawn Sears, MD, and Dan C Cohen, MD, Division of Gastroenterology, Scott & White Healthcare.

- This video, captured via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, shows cannulation of ampulla. Guide wire is then advanced, as seen on fluoroscopy, and wire makes right turn into pancreatic duct. Video courtesy of Dawn Sears, MD, and Dan C Cohen, MD, Division of Gastroenterology, Scott & White Healthcare.

- This video, captured via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, shows cannulation of common bile duct (CBD). Dye is then injected, and CBD is seen on fluoroscopy; there are filling defects suggestive of stones within duct. Video courtesy of Dawn Sears, MD, and Dan C Cohen, MD, Division of Gastroenterology, Scott & White Healthcare.

- This video, captured via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, shows insertion of biliary extraction balloon over guide wire. Sweeps of common bile duct (CBD) are made with extraction balloon to remove stones, sludge, and debris from CBD. Video courtesy of Dawn Sears, MD, and Dan C Cohen, MD, Division of Gastroenterology, Scott & White Healthcare.

- This video, captured via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, shows placement of biliary stent into common bile duct. Video courtesy of Dawn Sears, MD, and Dan C Cohen, MD, Division of Gastroenterology, Scott & White Healthcare.

- Endosonography-guided cholangiopancreatography. Used with permission from Baishideng Publishing Group, Inc (Fig 1 from Perez-Miranda M, de la Serna C, Diez-Redondo P, Vila JJ. Endosonography-guided cholangiopancreatography as a salvage drainage procedure for obstructed biliary and pancreatic ducts. World J Gastrointest Endosc. Jun 16 2010;2(6):212-22).

- Biliary obstruction secondary to chronic pancreatitis. Used with permission from the Johns Hopkins Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (www.hopkinsmedicine.org/gi). Illustration Copyright© 1998-2003 by The Johns Hopkins Health System Corporation and The Johns Hopkins University. Illustration created by Mike Linkinhoker.

- Technique for pancreatic stone extraction. Used with permission from the Johns Hopkins Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (www.hopkinsmedicine.org/gi). Illustration Copyright© 1998-2003 by The Johns Hopkins Health System Corporation and The Johns Hopkins University. Illustration created by Mike Linkinhoker.

- (A) Biliary sphincterotomy and stent placement; (B) corresponding endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) film. Used with permission from the Johns Hopkins Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (www.hopkinsmedicine.org/gi). Illustration Copyright© 1998-2003 by The Johns Hopkins Health System Corporation and The Johns Hopkins University. Illustration created by Mike Linkinhoker.

- Pancreatic stent placement for pseudocyst drainage. Used with permission from the Johns Hopkins Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (www.hopkinsmedicine.org/gi). Illustration Copyright© 1998-2003 by The Johns Hopkins Health System Corporation and The Johns Hopkins University. Illustration created by Mike Linkinhoker.

- Side-viewing endoscope. Used with permission from the Johns Hopkins Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (www.hopkinsmedicine.org/gi). Illustration Copyright© 1998-2003 by The Johns Hopkins Health System Corporation and The Johns Hopkins University. Illustration created by Mike Linkinhoker.

Author

Coauthor(s)

Specialty Editor Board

Mary L Windle, PharmD Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Kurt E Roberts, MD Associate Professor, Division of Bariatric and Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Yale University School of Medicine; Chair, Department of Surgery, Saint Francis Hospital, Trinity Health of New England Medical Group

Kurt E Roberts, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, Society of Laparoscopic and Robotic Surgeons

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Medscape Drugs & Diseases thanks Dawn Sears, MD, Associate Professor of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Scott and White Memorial Hospital, and Dan C Cohen, MD, Fellow in Gastroenterology, Scott and White Hospital, Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine, for assistance with the video contribution to this article.