Rectal Prolapse: Practice Essentials, Anatomy, Pathophysiology (original) (raw)

Overview

Practice Essentials

Rectal prolapse was described as early as 1500 BCE. This condition occurs when a mucosal or full-thickness layer of rectal tissue protrudes through the anal orifice. [1, 2] Problems with fecal incontinence, constipation, and rectal ulceration are common.

Three different clinical entities are often combined under the umbrella term rectal prolapse:

- Full-thickness rectal prolapse

- Mucosal prolapse

- Internal prolapse (internal intussusception)

Treatment of these three entities differs.

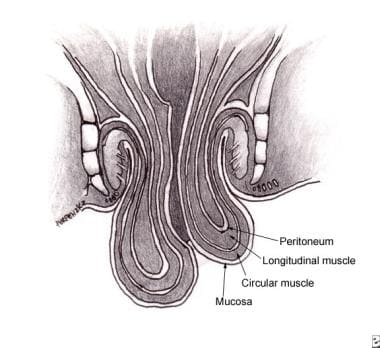

Full-thickness rectal prolapse (see the image below) is defined as protrusion of the full thickness of the rectal wall through the anus; it is the most commonly recognized type. Mucosal prolapse, in contrast, is defined as protrusion of only the rectal mucosa (not the entire wall) from the anus. Internal intussusception may be a full-thickness or a partial rectal wall disorder, but the prolapsed tissue does not pass beyond the anal canal and does not pass out of the anus.

Full-thickness rectal prolapse.

Most of this article focuses on full-thickness rectal prolapse, which, for the sake of convenience, will be referred to simply as rectal prolapse.

In adult patients, treatment of rectal prolapse is essentially surgical; no specific medical treatment is available. [3] (See Treatment.) Children, however, can usually be treated nonsurgically and by managing the underlying condition. There is no widespread agreement as to which repair constitutes the best treatment. Laparoscopic approaches have been developed that have outcomes as good as those of open abdominal procedures but are associated with shorter hospital stays and greater patient comfort.

Anatomy

The rectum is the distal 12-15 cm of the large intestine between the sigmoid colon and the anal canal. It primarily serves as a reservoir for fecal material. The mucosa is the inner lining of the intestinal tract. The dentate line is the junction of the ectoderm and endoderm in the anal canal.

The internal anal sphincter is a smooth muscle that is the most distal extension of the inner circular smooth muscle of the colon and the rectum. It is 2.5-4 cm long and normally 2-3 mm thick. The internal sphincter is not under voluntary control and is continuously contracted to prevent unplanned loss of stool.

The external anal sphincter is striated muscle that forms a circular tube around the anal canal. Moving proximally, it merges with the puborectalis and the levator ani to form a single complex. Control of the external anal sphincter is voluntary.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of rectal prolapse is not completely understood or agreed upon. There are two main theories, which essentially are different ways of expressing the same idea.

The first theory postulates that rectal prolapse is a sliding hernia through a defect in the pelvic fascia. The second theory holds that rectal prolapse starts as a circumferential internal intussusception of the rectum beginning 6-8 cm proximal to the anal verge. With time and straining, this progresses to full-thickness rectal prolapse, though some patients never progress beyond this stage.

The pathophysiology and etiology of mucosal prolapse most likely differ from those of full-thickness rectal prolapse and internal intussusception. [4] Mucosal prolapse occurs when the connective tissue attachments of the rectal mucosa are loosened and stretched, thus allowing the tissue to prolapse through the anus. This often occurs as a continuation of long-standing hemorrhoidal disease and is treated as such.

Often, prolapse begins with an internal prolapse of the anterior rectal wall and progresses to full prolapse.

Etiology

The precise cause of rectal prolapse is not defined; however, a number of associated abnormalities have been found. As many as 50% of prolapse cases are caused by chronic straining with defecation and constipation.

Other predisposing conditions include the following:

- Pregnancy

- Previous surgery

- Diarrhea

- Benign prostatic hypertrophy

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Cystic fibrosis

- Pertussis (ie, whooping cough)

- Pelvic floor dysfunction

- Parasitic infections – Amebiasis, schistosomiasis

- Neurologic disorders - Previous lower back or pelvic trauma/lumbar disk disease, cauda equina syndrome, spinal tumors, multiple sclerosis

- Disordered defecation (eg, stool withholding)

Certain anatomic features found during surgery for rectal prolapse are common to most patients. These features include a patulous or weak anal sphincter with levator diastasis, deep anterior Douglas cul-de-sac, poor posterior rectal fixation with a long rectal mesentery, and redundant rectosigmoid. Whether these anatomic features are causes or results of the prolapsing rectum is not known. [5]

In children, rectal prolapse is probably related to the vertical orientation of the rectum, the mobility of the sigmoid colon, the relative weakness of the pelvic floor muscle, mucosa that is poorly fixed to submucosa, and redundant rectal mucosa.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Rectal prolapse is uncommon; however, the true incidence is not known, because of underreporting, especially in the elderly population. Peaks in occurrence are noted in the fourth and seventh decades of life, and most patients (80-90%) are women. [6]

The condition is often concurrent with pelvic floor descent and prolapse of other pelvic floor organs, such as the uterus or the bladder. Although multiple pregnancies are often implicated in the etiology, 35% of patients are nulliparous. A small subset of children is affected, usually before the age of 3 years. Evaluation and treatment of children with rectal prolapse is addressed elsewhere.

International statistics

The annual incidence of rectal prolapse in Finland was found to be 2.5 per 100,000 population. [7]

Age-related demographics

Although all ages can be affected, peak incidences are observed in the fourth and seventh decades of life. Pediatric patients usually are affected when younger than 3 years, with the peak incidence in the first year of life. Mucosal prolapse is more common than complete prolapse (possibly because of poor fixation of the submucosa to the mucosa in pediatric patients). The incidence of prolapsed rectum in children with cystic fibrosis approaches 20%.

Sex-related demographics

In the adult population, the male-to-female ratio is 1:6. Although in the adult population, women account for 80-90% of cases, in the pediatric population, the incidence of rectal prolapse is evenly distributed between males and females. [8]

Prognosis

The prognosis generally is good with appropriate treatment. Spontaneous resolution usually occurs in children. Of patients with rectal prolapse who are aged 9 months to 3 years, 90% will need only conservative treatment. Continence usually is initially worse after surgical treatment, but in most patients it improves over time; however, the degree of improvement is unpredictable.

Untreated rectal prolapse can lead to incarceration and strangulation (rare). More commonly, increasing difficulties with rectal bleeding (usually minor), ulceration, and incontinence occur.

Postoperative mortality is low, but the recurrence rate can be as high as 15%, regardless of the operative procedure performed (see below). The most common postoperative complications involve bleeding and dehiscence at the anastomosis. Other complications include mucosal ulceration and necrosis of the rectal wall. Operative complications are higher for abdominal operations, with a lower recurrence rate; the opposite is true for perineal operations, which have a much lower complication rate but a higher recurrence rate.

Surgical treatment of rectal prolapse can be additionally challenging in patients who also have cirrhosis. In a study using data from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP), Janjua et al found that whereas complication rates for both cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients were higher with abdominal repair than with perineal repair, the rates for abdominal repair were higher in the cirrhotic group (25%) than in the noncirrhotic group (11%). [9] The presence of ascites as also a predictor of higher complication rates in patients with cirrhosis.

Recurrence

The recurrence rate for anterior resection without sacral fixation is about 7-9%, with a morbidity of 15-29%. This recurrence rate is higher than that for other abdominal procedures.

The recurrence rate for Marlex rectopexy is in the range of 2-10%, with a morbidity of 3-29%. Continence is improved in 50-70% of patients. Constipation, however, is not improved and may worsen after this operation. The results of suture rectopexy are comparable.

The recurrence rate for resection and rectopexy is 3-4%, with several studies reporting a 0% recurrence rate. Morbidity ranges from 4% to 23%. Because the redundant colon is also resected, constipation improves in 60-80% of patients, and continence improves in 35-60%.

The recurrence rate for Delorme mucosal sleeve resection ranges from 5% to 26%, with a variable morbidity that is usually related to the patient’s underlying comorbidities. Fecal incontinence and constipation improve in about 50% of patients.

The recurrence rate for Altemeier perineal rectosigmoidectomy ranges from 0% to 50%, with an average of approximately 10%. Continence may be improved if a levator plication is added to the procedure. A study by Altomare et al indicated that restoration of continence with this procedure can be unpredictable. [10]

A multicenter study by Bordeianou et al suggested that surgical treatment of recurrent rectal prolapse may yield better results if it employs a different operation from that used for the initial repair. [11]

- McNevin MS. Evaluation and Management of Rectal Prolapse. Surg Clin North Am. 2024 Jun. 104 (3):557-564. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Segal J, McKeown DG, Tavarez MM. Rectal Prolapse. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls; 2023. [Full Text].

- Hamahata Y, Akagi K, Maeda T, Nemoto K, Koike J. Management of Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) and Rectal Prolapse. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2022. 6 (2):83-91. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Wijffels NA, Collinson R, Cunningham C, Lindsey I. What is the natural history of internal rectal prolapse?. Colorectal Dis. 2010 Aug. 12 (8):822-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Harmston C, Jones OM, Cunningham C, Lindsey I. The relationship between internal rectal prolapse and internal anal sphincter function. Colorectal Dis. 2011 Jul. 13 (7):791-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gallo G, Martellucci J, Pellino G, Ghiselli R, Infantino A, Pucciani F, et al. Consensus Statement of the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (SICCR): management and treatment of complete rectal prolapse. Tech Coloproctol. 2018 Dec. 22 (12):919-931. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kairaluoma MV, Kellokumpu IH. Epidemiologic aspects of complete rectal prolapse. Scand J Surg. 2005. 94 (3):207-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hotouras A, Murphy J, Boyle DJ, Allison M, Williams NS, Chan CL. Assessment of female patients with rectal intussusception and prolapse: is this a progressive spectrum of disease?. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013 Jun. 56 (6):780-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Janjua M, Kearse L, Watson K, Zeineddin A, Rivera-Valerio M, Nembhard C. Less is more: Outcomes of surgical approaches to rectal prolapse in patients with cirrhosis. Surgery. 2024 Jul 11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Altomare DF, Binda G, Ganio E, De Nardi P, Giamundo P, Pescatori M, et al. Long-term outcome of Altemeier's procedure for rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009 Apr. 52 (4):698-703. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bordeianou L, Ogilvie JW Jr, Saraidaridis JT, Olortegui KS, Ratto C, Ky AJ, et al. Durable Approaches to Recurrent Rectal Prolapse Repair May Require Avoidance of Index Procedure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2024 Jul 1. 67 (7):968-976. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Elmalik K, Dagash H, Shawis RN. Abdominal posterior rectopexy with an omental pedicle for intractable rectal prolapse: a modified technique. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009 Aug. 25 (8):719-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kwak HD, Chung JS, Ju JK. A comparative study on the surgical options for male rectal prolapse. J Minim Access Surg. 2022 Jul-Sep. 18 (3):426-430. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Kumari M, MadhuBabu M, Vaidya H, Mital K, Pandya B. Outcomes of Laparoscopic Suture Rectopexy Versus Laparoscopic Mesh Rectopexy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2024 Jun. 16 (6):e61631. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- de Hoog DE, Heemskerk J, Nieman FH, van Gemert WG, Baeten CG, Bouvy ND. Recurrence and functional results after open versus conventional laparoscopic versus robot-assisted laparoscopic rectopexy for rectal prolapse: a case-control study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009 Oct. 24 (10):1201-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Sajid MS, Siddiqui MR, Baig MK. Open vs laparoscopic repair of full-thickness rectal prolapse: a re-meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2010 Jun. 12 (6):515-25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ismail M, Gabr K, Shalaby R. Laparoscopic management of persistent complete rectal prolapse in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2010 Mar. 45 (3):533-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kosba Y, Elshazly WG, Abd El Maksoud W. Posterior sagittal approach for mesh rectopexy as a management of complete rectal in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010 Jul. 25 (7):881-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gurland B, Garrett KA, Firoozi F, Goldman HB. Transvaginal sacrospinous rectopexy: initial clinical experience. Tech Coloproctol. 2010 Jun. 14 (2):169-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Senapati A, Gray RG, Middleton LJ, Harding J, Hills RK, Armitage NC, et al. PROSPER: a randomised comparison of surgical treatments for rectal prolapse. Colorectal Dis. 2013 Jul. 15 (7):858-68. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Madiba TE, Baig MK, Wexner SD. Surgical management of rectal prolapse. Arch Surg. 2005 Jan. 140 (1):63-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Marderstein EL, Delaney CP. Surgical management of rectal prolapse. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Oct. 4 (10):552-61. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Randall J, Smyth E, McCarthy K, Dixon AR. Outcome of laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy for external rectal prolapse. Colorectal Dis. 2014 Nov. 16 (11):914-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Koimtzis G, Stefanopoulos L, Geropoulos G, Chalklin CG, Karniadakis I, Alawad AA, et al. Mesh Rectopexy or Resection Rectopexy for Rectal Prolapse; Is There a Gold Standard Method: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis. J Clin Med. 2024 Feb 28. 13 (5):[QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hetzer FH, Roushan AH, Wolf K, Beutner U, Borovicka J, Lange J, et al. Functional outcome after perineal stapled prolapse resection for external rectal prolapse. BMC Surg. 2010 Mar 8. 10:9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Tschuor C, Limani P, Nocito A, Dindo D, Clavien PA, Hahnloser D. Perineal stapled prolapse resection for external rectal prolapse: is it worthwhile in the long-term?. Tech Coloproctol. 2013 Oct. 17 (5):537-40. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rectal prolapse.

- Full-thickness rectal prolapse.

- Marlex rectopexy for rectal prolapse.

- Delorme mucosal sleeve resection for rectal prolapse.

- Altemeier perineal rectosigmoidectomy for rectal prolapse.

Author

Jan Rakinic, MD Chief, Section of Colorectal Surgery, Program Director, SIU Residency in Colorectal Surgery, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine

Jan Rakinic, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, American Medical Association, American Medical Women's Association, American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, Illinois State Medical Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Coauthor(s)

Lisa Susan Poritz, MD Associate Professor of Surgery and Cellular and Molecular Physiology, Director, Colon and Rectal Research, Department of Surgery, Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery, Milton S Hershey Medical Center, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine

Lisa Susan Poritz, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, American Physiological Society, Central Surgical Association, Society of University Surgeons, Association of Women Surgeons, American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, Association for Academic Surgery, Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

John Geibel, MD, MSc, DSc, AGAF Vice Chair and Professor, Department of Surgery, Section of Gastrointestinal Medicine, Professor, Department of Cellular and Molecular Physiology, Yale University School of Medicine; Director of Surgical Research, Department of Surgery, Yale-New Haven Hospital; American Gastroenterological Association Fellow; Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine

John Geibel, MD, MSc, DSc, AGAF is a member of the following medical societies: American Gastroenterological Association, American Physiological Society, American Society of Nephrology, Association for Academic Surgery, International Society of Nephrology, New York Academy of Sciences, Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Michael S Beeson, MD, MBA, FACEP Professor of Emergency Medicine, Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine and Pharmacy; Attending Faculty, Akron General Medical Center

Michael S Beeson, MD, MBA, FACEP is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency Physicians, Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors, National Association of EMS Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Brian James Daley, MD, MBA, FACS, FCCP, CNSC Professor, Associate Program Director, Department of Surgery, Division of Trauma and Critical Care, University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Medicine

Brian James Daley, MD, MBA, FACS, FCCP, CNSC is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for the Surgery of Trauma, American College of Chest Physicians, American College of Surgeons, American Medical Association, Association for Academic Surgery, Association for Surgical Education, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, Shock Society, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Southeastern Surgical Congress, and Tennessee Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Steven C Dronen, MD, FAAEM Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine, LeConte Medical Center

Steven C Dronen, MD, FAAEM is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Lynn K Flowers, MD, MHA, FACEP Physician Partner, ApolloMD, Atlanta, Georgia

Lynn K Flowers, MD, MHA, FACEP is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency Physicians, American Medical Association, National Association of EMS Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

David L Morris, MD, PhD, FRACS Professor, Department of Surgery, St George Hospital, University of New South Wales, Australia

David L Morris, MD, PhD, FRACS is a member of the following medical societies: British Society of Gastroenterology

Disclosure: RFA Medical None Director; MRC Biotec None Director

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Medscape Salary Employment