Pediatric Hyperthyroidism: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology (original) (raw)

Overview

Background

Hyperthyroidism refers to overactivity of the thyroid gland, which leads to excessive release of thyroid hormones and consequently accelerated metabolism in the peripheral tissues. Thyrotoxicosis refers to the clinical effects of unbound thyroid hormones, whether or not the thyroid gland is the primary source. Hyperthyroidism is the most prevalent cause of thyrotoxicosis but a relatively rare condition in children. Graves disease, a form of thyroid autoimmune disorder featuring hyperthyroidism, [1] in childhood accounts only for 1-5% of all patients with Graves disease but is the cause of more than 95% of cases of pediatric thyrotoxicosis. [2]

In children and adolescents, the symptoms of Graves disease, such as hyperthyroidism, may appear insidiously over months. Early diagnosis requires a high degree of suspicion. The main clinical features are goiter, tachycardia, nervousness, hypertension, tremor, weight loss despite increased appetite, hyperactivity, irregular menses, ophthalmopathy, heat intolerance, and diarrhea.

The Japanese Thyroid Association (JTA) includes the following diagnostic criteria for childhood-onset Graves disease [3] :

Clinical findings

- Signs of thyrotoxicosis such as tachycardia, weight loss, finger tremor, and sweating.

- Diffuse enlargement of the thyroid gland.

- Exophthalmos and/or specific ophthalmopathy

Laboratory findings

- Elevation in serum free thyroxine (FT4) and/or free triiodothyronine (FT3) level

- Suppression of serum thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH): less than 0.1 μU/mL

- Positive for anti-TSH receptor antibody (TRAb or TSH binding inhibitory immunoglobulin [TBII]) or thyroid stimulating antibody (TSAb)

- Elevated radioactive iodine (or 99mTcO4–) uptake to the thyroid gland

Graves disease is diagnosed with at least one of the clinical findings and all four laboratory findings. Graves disease is suspected with at least one of the clinical findings and the first three laboratory findings or at least one of the clinical findings and first two laboratory findings. Elevation in serum FT4 has usually been present for at least 3 months.

Treatment approaches include antithyroid drugs (ATDs), which are commonly used as the first-line treatment, or thyroid ablation with either radioactive iodine therapy or thyroidectomy. However, ATDs have a high rate of relapse. Treatment with radioiodine or surgical subtotal thyroidectomy is very effective, but most patients develop hypothyroidism and require lifelong thyroid replacement. Although remission in adults is 40-60%, only about one third of children achieve remission. [2]

See also Pediatric Graves Disease; Hyperthyroidism and Thyrotoxicosis; Hyperthyroidism, Thyroid Storm, and Graves Disease in Emergency Medicine; Pediatric Hypothyroidism; Graves Disease; Orbital Decompression for Graves Disease; and Thyroid-Associated Orbitopathy.

Pathophysiology

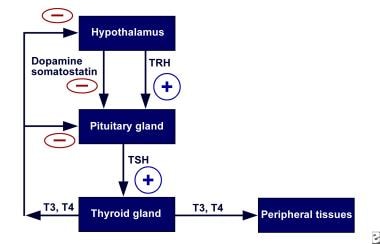

Understanding the normal physiology of the thyroid gland is necessary to understand the pathophysiology of hyperthyroidism. Secretion of thyroid hormone is controlled by the interaction of stimulatory and inhibitory factors. The thyroid, like other endocrine glands, is controlled by a complex feedback mechanism (see the image below).

Pediatric Hyperthyroidism. Schematic representation of the negative/positive feedback system with respect to the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis. TRH = thyrotropin-releasing hormone; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone.

The release of thyrotropin, or thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), from the anterior pituitary gland is stimulated by low circulating levels of thyroid hormones (negative feedback) and is under the influence of thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), somatostatin, or dopamine. Thyrotropin then binds to TSH receptors on the thyroid gland, setting off a cascade of events within the thyroid gland, leading to the release of the thyroid hormones, primarily thyroxine (T4) and, to a lesser degree, triiodothyronine (T3). Elevated levels of these hormones, in turn, act on the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary gland, decreasing synthesis of TSH. Under physiologic conditions, the levels of circulating free thyroid hormones are tightly regulated.

The TSH receptor belongs to one of the families of proteins known as G-protein–coupled receptors. The TSH receptor is a large protein embedded in the cell membrane. It contains an extracellular domain (that binds) TSH and an intracellular domain that acts via a G-protein second messenger system to activate thyroid adenyl cyclase, yielding cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). Effects of TSH are largely mediated through this second messenger system.

Synthesis of thyroid hormone depends on an adequate supply of iodine. Dietary inorganic iodide is transported into the gland by an iodide transporter (iodide pump on the surface of thyroid follicular cells). Iodide is then converted to iodine and bound to tyrosine residues on thyroglobulin by the enzyme thyroid peroxidase via a process called organification. The result is the formation of monoiodotyrosine (MIT) and diiodotyrosine (DIT). Coupling of MIT and DIT results in the formation of T3 and T4, which are then stored with thyroglobulin in the extracellular colloid of the thyroid’s follicular lumen. The thyroid contains a large supply of its preformed hormones.

To release thyroid hormones, thyroglobulin is first endocytosed into the follicular cell and then degraded by lysosomal enzymes. Stored T4, and T3 to a lesser degree, then diffuse into the peripheral circulation. Most T4 and T3 in the peripheral circulation are bound to plasma proteins and are inactive. Only 0.02% of T4 and 0.3% of T3 molecules are free (unbound to other proteins). T4 can be monodeiodinated to form either T3 or reverse T3 (rT3), but only free T3 is metabolically active. T3 acts by binding to nuclear receptors (DNA-binding proteins in cell nuclei), regulating the transcription of various cellular proteins.

Any process that causes an increase in the peripheral circulation of unbound thyroid hormone can cause signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism. Disturbances of the normal homeostatic mechanism can occur at the level of the pituitary gland, the thyroid gland, or in the periphery. Regardless of etiology (see Etiology), the result is an increase in transcription in cellular proteins causing an increase in the basal metabolic rate. In many ways, signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism resemble a state of catecholamine excess, and adrenergic blockade can improve these symptoms.

Etiology

Childhood Graves disease

Graves disease accounts for the majority of cases of hyperthyroidism in children and adolescents. It is an autoimmune disease associated with thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor-stimulating antibodies. Classic Graves disease includes the triad of hyperthyroidism, ophthalmopathy, and dermopathy. Dermopathy is characterized by localized myxedema and is extremely unusual in children.

Hyperthyroidism in Graves disease is caused by thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins (TSIs) of the immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) subclass. These antibodies bind to the extracellular domain of the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor and activate it, causing follicular growth and activation and release of thyroid hormones. Patients may have a number of other antithyroid antibodies, some of which are also thyroid receptor antibodies (TRAbs) but which may not activate the receptor. Interplay between these various antibodies likely determines the course and severity of disease.

Initial stimulus for the formation of TSI is not known. Some microorganisms, such as Yersinia species, have proteins that bind TSH. Infection with these organisms possibly induces antibodies that cross-react with the TSH receptor. Some clinical evidence supports this hypothesis. Other evidence suggests that viral infection of the thyroid may be involved. Viruses may induce expression of major histocompatibility (MHC) class II antigens on the surface of thyroid follicular cells, leading to an immune response and autoantibody formation.

Ophthalmopathy of Graves disease is multifactorial. Some symptoms, such as lid lag and lid retraction, are caused by sympathomimetic effects of the thyrotoxicosis and resolve when the patient becomes euthyroid. Other symptoms may be a result of an autoimmune reaction against the muscles or fibroblasts of the orbit. These symptoms may not resolve with correction of the thyroid dysfunction. Theoretically, a shared antigen or antigens between the thyroid gland and the contents of the orbit may be present.

Neonatal Graves disease

Graves disease in neonates accounts for fewer than 1% of all cases of hyperthyroidism in pediatric patients. The frequency of neonatal Graves disease is equal in males and females, reflecting the underlying pathophysiology. Pathogenesis and course of the disorder in this age group are unique. Virtually all patients have a maternal history of Graves disease, either during the pregnancy or at some time in the past.

Neonatal Graves disease is caused by the transplacental passage of TSI. The mother may have clinical hyperthyroidism, may be on antithyroid medication, or may have a history of radioablation therapy or thyroid surgery. Rarely, the mother has a history of chronic lymphocytic (Hashimoto) thyroiditis. Maternal elevation of TSI titers is a consistent finding in these cases.

Neonatal Graves disease is rare even among mothers with known hyperthyroidism. Only 1 in 70 infants of thyrotoxic mothers has clinical symptoms. A maternal TSI level must be very high (>5 times normal) to produce clinical disease in the neonate.

Because neonatal Graves disease is caused by maternal IgG antibodies, it is self-limited and resolves when the child is aged 3-4 months. Symptoms of hyperthyroidism rarely persist longer. More persistent hyperthyroidism in neonates is likely to reflect a different pathogenesis, such as an activating mutation of the TSH receptor.

Prenatally, the thyroid gland is fully responsive at 28 weeks' gestation. These babies can be treated with methimazole, which is given to the mother. Methimazole may be preferable to propylthiouracil (PTU), because methimazole binds less to plasma proteins and therefore crosses the placenta more easily. However, the risk of cutis aplasia may be increased in infants born to mothers who have taken methimazole during pregnancy. PTU is associated with a higher incidence of idiopathic liver failure.

If the mother is taking antithyroid drugs, infants are usually born asymptomatic. Signs and symptoms may become manifest when antithyroid medications that have crossed the placenta are cleared from the infant's bloodstream. Signs are similar to those in older children with thyrotoxicosis, such as tachycardia, wide pulse pressure, irritability, tremor, and hyperphagia with poor weight gain. The baby may have exophthalmos and goiter.

Neonates have a much higher risk of morbidity and mortality from cardiac disease. In severe cases, congestive heart failure (CHF) can be observed. In addition, the goiter can occasionally be large enough to cause airway compression.

Long-term effects can include craniosynostosis and developmental delay. This latter finding occurs even in the face of early diagnosis and treatment, which suggests that prenatal exposure to high levels of thyroid hormone may have early effects that cannot be overcome after birth.

Toxic adenomas, toxic nodular goiter, carcinomas

Isolated toxic adenoma (Plummer disease) and toxic nodular goiter of adulthood are rare in children. Although follicular or papillary carcinomas can appear as a thyroid mass, they are virtually always nonfunctioning and therefore rarely cause hyperthyroidism.

McCune-Albright syndrome

Hyperthyroidism associated with McCune-Albright syndrome is rare. This syndrome includes polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, café-au-lait spots, or other endocrinopathies. The most common endocrinopathy is precocious puberty, but hyperthyroidism also can be observed.

In addition to other signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism, patients initially present with a diffuse goiter. The goiter may become a multinodular goiter over time.

Hyperthyroidism in McCune-Albright syndrome is due to a mutation in the α subunit of the G regulatory protein that links the TSH receptor with adenylate cyclase. This mutation results in constitutive activation of the protein and production of cAMP, bypassing the normal requirement for TSH activation of the receptor. Biopsies revealed some tissue with the normal protein and other tissue with the mutated protein, suggesting that the mutation may occur postfertilization and providing an explanation for its heterogeneous expression.

Unlike the hyperthyroidism of Graves disease, McCune-Albright syndrome does not spontaneously remit. Treatment with antithyroid medications provides only temporary benefit. Therefore, the treatment of choice is surgical resection (thyroidectomy) or radioactive iodine ablation. Injection of ethanol into toxic nodules under ultrasonographic guidance has been used with some success in adults. [4]

Subacute thyroiditis

Subacute thyroiditis is generally associated with a viral upper respiratory infection. Signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism are mild and generally overshadowed by fever and thyroid tenderness. The area surrounding the thyroid may be erythematous and warm, and the gland is always tender to touch.

Hyperthyroidism in these patients is caused by inflammation of the thyroid gland and subsequent release of preformed thyroid hormone. Laboratory studies reveal elevated thyroid hormones and decreased TSH. Unlike iodine 1 123 (123 I) or technetium TC 99m (99m Tc) radionuclide scans in patients with Graves disease, radionuclide scans in patients with subacute thyroiditis show decreased uptake by the thyroid gland. Once the inflammation resolves, thyroid-related symptoms resolve.

Because antithyroid medications do not prevent the release of preformed thyroid hormones, these agents are not useful.

Cardiac symptoms can be alleviated with propranolol. Anti-inflammatory medications, such as aspirin and corticosteroids, offer symptomatic relief.

Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis

Like Graves disease, chronic lymphocytic (ie, Hashimoto) thyroiditis is an autoimmune disorder. However, in patients with chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, antithyroglobulin and antithyroid peroxidase antibodies predominate. If present, TSI titers are low.

The hyperthyroid phase of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (hashitoxicosis) is self-limited and responds to antithyroid therapy. Antithyroid T lymphocytes and antibodies cause destruction of thyroid follicular cells, and hypothyroidism occurs over time.

The duration of the hyperthyroid phase of Hashimoto thyroiditis may be as long as 6 months.

One study found that 11.5% of patients with Hashimoto thyroiditis presented with hyperthyroidism. [5]

Epidemiology

Because Graves disease accounts for more than 95% of childhood cases of hyperthyroidism in the United States, the frequency of Graves disease approximates the frequency of all cases of hyperthyroidism. Prevalence of Graves disease is approximately 1 in 10,000 in the pediatric population [6] , accounting for fewer than 5% of the total US cases of Graves disease.

Graves disease is associated with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B8 and HLA-DR3 and is more common in some families than in others. Inheritance is polygenic. Monozygotic twins show 50% concordance for the disease, suggesting interplay between environmental and genetic factors.

Associations between Graves disease and other autoimmune diseases are well described and include associations with diabetes mellitus (DM), Addison disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), myasthenia gravis, vitiligo, immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), and pernicious anemia. Graves disease is more common in patients with trisomy 21 than in patients without trisomy 21.

One study estimated the incidence of hyperthyroidism in the United States in 2008 based on the number of new prescriptions of thionamides by age group and date from the 2008 US Census. [7] The study concluded that the incidence among individuals aged 0-11 years was 0.44 cases per 1000 population and that the incidence among individuals aged 12-17 years was 0.59 cases per 1000 population. [7] Thus, the incidence increases throughout childhood, with a peak incidence in children aged 10-15 years.

Sexual differences in incidence

Although females are affected by Graves disease more often than males, with a reported female-to-male ratio of 3-6:1, the frequency of neonatal Graves disease is equal in males and females.

Other causes of hyperthyroidism have no male or female preponderance. These include the hyperthyroidism of McCune-Albright syndrome, although the variant of this syndrome that includes precocious puberty is more common in girls than in boys.

Prognosis

The vast majority of pediatric patients with hyperthyroidism have an excellent prognosis. However, those diagnosed with Graves disease and treated in childhood may have a lower quality of life than thier healthy peers. [8] Signs of congestive heart failure (CHF) are rare in children. Ophthalmopathy of Graves disease is usually mild but may persist despite resolution of the hyperthyroidism.

Although the course of neonatal Graves disease is self-limited, the prognosis is considerably worse than that in older children. As a result of their disease, patients are prone to prematurity, airway obstruction, and heart failure. The mortality rate from these conditions has been as high as 16%. Even patients who are successfully treated may develop craniosynostosis and eventual developmental delay.

Complications from hyperthyroidism include the following:

- Congestive heart failure (CHF)

- Craniosynostosis (neonates)

- Developmental delay (neonates)

- Hypothyroidism

- Hypercalcemia is occasionally seen in patients with hyperthyroidism.

Only one-third of pediatric patients with Graves disease achieve remission. In one study, the strongest predictor of remission was TRAb normalization timing. Patients who normalized TRAb levels in the first year had a 70% remission rate and among those who normalized in the second year of therapy, a 50% remission rate was seen. [2]

Complications

Graves orbitopathy (GO) is the main extrathyroidal manifestation of Graves disease, though severe forms are rare. In a study of 346 newly diagnosed patients at a single center over an 8-year period found moderate-to-severe and active GO or sight-threatening GO were rare at presentation and rarely develop during ATD treatment. Most patients (>80%) with no GO at baseline did not develop GO after an 18-month follow-up period. Remission of mild GO occurs in the majority of cases. [9]

In its 2016 guidelines, the European Thyroid Association/European Group on Graves Orbitopathy (EUGOGO) provides an algorithm for treatment selection based on activity and severity. [10]

Patient Education

Compliance

Patients who choose treatment with antithyroid medications should be educated on the importance of compliance, as noncompliance can be problematic. Patients with hyperthyroidism are prone to forgetting their medicine because of short attention span. Some patients skip their medicine as a way of controlling their weight.

Treatment adverse effects

Counsel patients regarding the common and uncommon adverse effects of treatment. At the first sign of a serious adverse effect, such as fever, rash, jaundice, arthritis, or mucocutaneous ulcer, their antithyroid medications should be discontinued; laboratory evaluation may be appropriate.

Patients and their parents should also be warned about excessive weight gain as the hyperthyroidism is corrected. Treatment of hyperthyroidism is associated with excessive weight gain, unless food intake is decreased.

Thyroid storm, thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism, and adrenergic agents

Patients with Graves disease and their parents should be also advised to take necessary precautions to avoid trauma to the neck area, as this could precipitate thyroid storm.

All patients monitored for hyperthyroidism should be aware of the signs and symptoms of thyrotoxicosis (should they have a relapse) and the signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism. Symptoms of hypothyroidism include fatigue, cold intolerance, hoarseness, constipation, muscle cramps, menstrual irregularities, and weight gain. Signs of hypothyroidism include dry skin, bradycardia, edema, and delayed relaxation of deep tendon reflexes.

In addition, because thyrotoxic symptoms largely mimic those of adrenergic excess, patients with hyperthyroidism should avoid taking any adrenergic agents. Advise patients not to take over-the-counter (OTC) cold remedies because many contain sympathomimetic agents (eg, pseudoephedrine) and can therefore exacerbate thyrotoxic symptoms.

- Borowiec A, Labochka D, Milczarek M, et al. Graves' disease in children in the two decades following implementation of an iodine prophylaxis programme. Cent Eur J Immunol. 2018. 43 (4):399-404. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Gastaldi R, Poggi E, Mussa A, et al. Graves disease in children: thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies as remission markers. J Pediatr. 2014 May. 164(5):1189-1194.e1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Committee on Pharmaceutical Affairs, Japanese Society for Pediatric Endocrinology, and the Pediatric Thyroid Disease Committee, Japan Thyroid Association et al. Guidelines for the treatment of childhood-onset Graves' disease in Japan, 2016. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol. 2017. 26(2):29-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Sharma A, Abraham D. Vascularity-targeted percutaneous ethanol injection of toxic thyroid adenomas: outcomes of a feasibility study performed in the USA. Endocr Pract. 2020 Jan. 26(1):22-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Nabhan ZM, Kreher NC, Eugster EA. Hashitoxicosis in children: clinical features and natural history. J Pediatr. 2005 Apr. 146(4):533-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Conference Proceeding. Hepatic Toxicity Following Treatment for Pediatric Graves’ Disease Meeting. October 28, 2008. Available at https://bpca.nichd.nih.gov/collaborativeefforts/Documents/Hepatic_Toxicity_10-28-2008.pdf#search=graves.

- Emiliano AB, Governale L, Parks M, Cooper DS. Shifts in propylthiouracil and methimazole prescribing practices: antithyroid drug use in the United States from 1991 to 2008. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 May. 95(5):2227-33. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Mooij CF, Cheetham TD, Verburg FA, et al. 2022 European Thyroid Association guideline for the management of pediatric Graves' disease. Eur Thyroid J. 2022 Jan 1. 11(1):e210073. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Tanda ML, Piantanida E, Liparulo L, et al. Prevalence and natural history of Graves' orbitopathy in a large series of patients with newly diagnosed graves' hyperthyroidism seen at a single center. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013 Apr. 98(4):1443-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Bartalena L, Baldeschi L, Boboridis K, et al, for the European Group on Graves' Orbitopathy (EUGOGO). The 2016 European Thyroid Association/European Group on Graves' Orbitopathy guidelines for the management of Graves' orbitopathy. Eur Thyroid J. 2016 Mar. 5(1):9-26. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Yoshimura Noh J, Miyazaki N, Ito K, et al. Evaluation of a new rapid and fully automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay for thyrotropin receptor autoantibodies. Thyroid. 2008 Nov. 18(11):1157-64. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Baskaran C, Misra M, Levitsky LL. Diagnosis of pediatric hyperthyroidism: technetium 99 uptake versus thyroid stimulating immunoglobulins. Thyroid. 2015 Jan. 25(1):37-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Ross DS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al. 2016 American Thyroid Association guidelines for diagnosis and management of hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid. 2016 Oct. 26(10):1343-421. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Amisha F, Rehman A. Propylthiouracil (PTU). StatPearls [Internet]. Updated: Jun 10, 2022. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] US Preventative Services Task Force. Screening for thyroid disease: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004 Jan 20. 140(2):125-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Peroni E, Angiolini MR, Vigone MC, et al. Surgical management of pediatric Graves' disease: an effective definitive treatment. Pediatr Surg Int. 2012 Jun. 28(6):609-14. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chen Y, Masiakos PT, Gaz RD, et al. Pediatric thyroidectomy in a high volume thyroid surgery center: Risk factors for postoperative hypocalcemia. J Pediatr Surg. 2015 Aug. 50(8):1316-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] van der Kaay DC, Wasserman JD, Palmert MR. Management of neonates born to mothers with Graves' disease. Pediatrics. 2016 Apr. 137(4):e20151878. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Klatka M, Grywalska E, Partyka M, Charytanowicz M, Rolinski J. Impact of methimazole treatment on magnesium concentration and lymphocytes activation in adolescents with Graves' disease. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2013 Jun. 153(1-3):155-70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Toderian AB, Lawson ML. Use of antihistamines after serious allergic reaction to methimazole in pediatric Graves' disease. Pediatrics. 2014 May. 133(5):e1401-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: New Boxed Warning on severe liver injury with propylthiouracil. April 21, 2010 [Current as of February 6, 2018]. Available at <https://FDA Drug Safety Communication: New Boxed Warning on severe liver injury with propylthiouracil>.

- Sisson JC, Freitas J, McDougall IR, et al. Radiation safety in the treatment of patients with thyroid diseases by radioiodine 131I : practice recommendations of the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2011 Apr. 21(4):335-46. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and the postpartum. Thyroid. 2017 Mar. 27(3):315-89. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Pediatric Hyperthyroidism. Schematic representation of the negative/positive feedback system with respect to the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis. TRH = thyrotropin-releasing hormone; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Author

Coauthor(s)

Chief Editor

Stephen Kemp, MD, PhD Former Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Section of Pediatric Endocrinology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences College of Medicine, Arkansas Children's Hospital

Stephen Kemp, MD, PhD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association of Clinical Endocrinology, American Pediatric Society, Endocrine Society, Phi Beta Kappa, Southern Medical Association, Southern Society for Pediatric Research

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

George P Chrousos, MD, FAAP, MACP, MACE, FRCP(London) Professor and Chair, First Department of Pediatrics, Athens University Medical School, Aghia Sophia Children's Hospital, Greece; UNESCO Chair on Adolescent Health Care, University of Athens, Greece

George P Chrousos, MD, FAAP, MACP, MACE, FRCP(London) is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Endocrinology, American College of Physicians, American Pediatric Society, American Society for Clinical Investigation, Association of American Physicians, Endocrine Society, Pediatric Endocrine Society, and Society for Pediatric Research

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Cydney L Fenton, MD, FAAP Consulting Staff, Department of Pediatric Endocrinology, Children's Hospital Medical Center of Akron

Cydney L Fenton, MD, FAAP is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, American Diabetes Association, Endocrine Society, and Lawson-Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Robert J Ferry Jr, MD Le Bonheur Chair of Excellence in Endocrinology, Professor and Chief, Division of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Pediatrics, University of Tennessee Health Science Center

Robert J Ferry Jr, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, American Diabetes Association, American Medical Association, Endocrine Society, Pediatric Endocrine Society, Society for Pediatric Research, and Texas Pediatric Society

Disclosure: Eli Lilly & Co Grant/research funds Investigator; MacroGenics, Inc Grant/research funds Investigator; Ipsen, SA (formerly Tercica, Inc) Grant/research funds Investigator; NovoNordisk SA Grant/research funds Investigator; Diamyd Grant/research funds Investigator; Bristol-Myers-Squibb Grant/research funds Other; Amylin Other; Pfizer Grant/research funds Other; Takeda Grant/research funds Other

Ab Sadeghi-Nejad, MD Chief, Division of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, Tufts Medical Center; Professor of Pediatrics, Tufts University School of Medicine

Ab Sadeghi-Nejad, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association for the Advancement of Science, American Pediatric Society, Endocrine Society, Massachusetts Medical Society, Pediatric Endocrine Society, and Society for Pediatric Research

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Thomas A Wilson, MD Professor of Clinical Pediatrics, Chief and Program Director, Division of Pediatric Endocrinology, Department of Pediatrics, The School of Medicine at Stony Brook University Medical Center

Thomas A Wilson, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Endocrine Society, Pediatric Endocrine Society, and Phi Beta Kappa

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Mary L Windle, PharmD Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.