Dieter Rams (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

German industrial designer

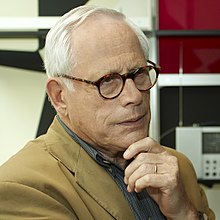

| Dieter Rams | |

|---|---|

Dieter Rams in 2010 Dieter Rams in 2010 |

|

| Born | (1932-05-20) 20 May 1932 (age 92)Wiesbaden, Hesse-Nassau, Prussia, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | Industrial designer |

| Known for | Ten principles of "good design"Braun consumer productsVitsœ furniture |

| Notable work | Braun SK 4 radiogramVitsœ 606 Universal Shelving System |

| Spouse | Ingeborg Kracht-Rams |

| Awards | Commander's Cross (Order of Merit, Germany) |

| Website | rams-foundation.org |

Dieter Rams (born 20 May 1932) is a German industrial designer who is most closely associated with the consumer products company Braun, the furniture company Vitsœ, and the functionalist school of industrial design. His unobtrusive approach and belief in "less, but better" (German: Weniger, aber besser) design has influenced the practice of design, as well as 20th century aesthetics and culture.[1][2] He is quoted as stating that "Indifference towards people and the reality in which they live is actually the one and only cardinal sin in design."[3]

Early life and education

[edit]

Rams' undergraduate work 1952 a model of a chair

Dieter Rams was born in Wiesbaden, Germany in 1932.[4] He began his studies in architecture and interior decoration at Wiesbaden School of Art (now part of the RheinMain University of Applied Sciences) in 1947. A year later, he took a break from studying to gain practical experience and finish his carpentry apprenticeship. He returned to the Wiesbaden School of Art in 1948 and graduated in architecture with honours in 1953, after which he began working for Frankfurt-based architect Otto Apel.[5] In 1955, he was recruited by Braun as an architect and an interior designer,[4] and eventually became a protégé of Fritz Eichler and the Ulm School of Design professors Hans Gugelot and Otl Aicher,[6] all of whom worked for Braun in various capacities.[7][8]

Braun Phonosuper SK 4 "Snow White's coffin" by Dieter Rams and Hans Gugelot (1956)

Rams joined Braun in 1955 at the age of 23. In 1961 he became head of design at the company, a position he retained until his retirement at the age of 65 in 1997.[6][9][10][4]

Rams and his staff designed many memorable products for Braun including the famous Phonosuper SK 4 [de] radiogram and the high-quality 'D'-series (D 45, D 46) of 35mm film slide projectors. The SK 4, known as the "Snow White's coffin," is considered revolutionary because it transitioned household appliance design away from looking like traditional furniture.[11] By producing electronic gadgets that were remarkable in their austere aesthetic and user friendliness, Rams made Braun a household name in the 1950s.

In 1968, Rams designed the cylindric T 2 cigarette lighter for Braun. A member of the company's board had asked him for a design; Rams replied, "only if we design our own technology to go inside them." Successive versions of the product went on to use then-current motorcycle-like magnetic ignition, followed by piezoelectric, and finally solar-powered mechanisms.[12]

Rams's furniture seen in a Vitsœ showroom in Tokyo

In 1959, Rams began a collaboration with Vitsœ, at the time known as Vitsœ-Zapf, which led to the development of the 606 Universal Shelving System, which is still sold today, with only minor changes from the original.[13] He also designed furniture for Vitsœ in the 1960s, including the 620 chair collection.[8] He worked with both Braun and Vitsœ until his retirement in 1997, and continues to work with Vitsœ.[6][14]

Apple iPod pictured next to a 1958 Braun T3 transistor radio

His approach to design and his aesthetics influenced Apple designer Jonathan Ive[15] and many Apple products pay tribute[16] to Rams's work for Braun,[17] including Apple's iOS 6 calculator, which references[18] the 1977 ET66 calculator,[19] and prior to a redesign, the appearance of the playing screen in Apple's Podcast app mimicked the appearance of the Braun TG 60 reel-to-reel tape recorder. The iOS 7 world clock app closely mirrors Braun's clock and watch design, while the original iPod closely resembles the Braun T3 transistor radio.[20][21][10] In Gary Hustwit's 2009 documentary film Objectified, Rams states that Apple is one of the few companies designing products according to his principles.[22][23] In a 2010 interview with Die Zeit, Rams mentions that Ive personally sent him an iPhone "Along with a nice letter. He thanked me for the inspiration that my work was to him".[10]

The designer Jasper Morrison has spoken[24] of his grandfather's Rams designed Braun "Snow White's Coffin" being an "important influence on [his] choice in becoming a designer."[25][26][18]

Ten Principles of Good design

[edit]

Braun SK 61

Rams introduced the idea of sustainable development, and of obsolescence being a crime in design, in the 1970s.[6] Accordingly, he asked himself the question: "Is my design a good design?" The answer he formed became the basis for his celebrated "Ten Principles of Good design".[27][28] According to Rams, "good design":[29][30]

- is innovative – The possibilities for progression are not, by any means, exhausted. Technological development is always offering new opportunities for original designs. But imaginative design always develops in tandem with improving technology, and can never be an end in itself.

- makes a product useful – A product is bought to be used. It has to satisfy not only functional, but also psychological and aesthetic criteria. Good design emphasizes the usefulness of a product whilst disregarding anything that could detract from it.[31]

- is aesthetic – The aesthetic quality of a product is integral to its usefulness because products are used every day and have an effect on people and their well-being. Only well-executed objects can be beautiful.

- makes a product understandable – It clarifies the product’s structure. Better still, it can make the product clearly express its function by making use of the user's intuition. At best, it is self-explanatory.

- is unobtrusive – Products fulfilling a purpose are like tools. They are neither decorative objects nor works of art. Their design should therefore be both neutral and restrained, to leave room for the user's self-expression.

- is honest – It does not make a product appear more innovative, powerful or valuable than it really is. It does not attempt to manipulate the consumer with promises that cannot be kept.

- is long-lasting – It avoids being fashionable and therefore never appears antiquated. Unlike fashionable design, it lasts many years – even in today's throwaway society.

- is thorough down to the last detail – Nothing must be arbitrary or left to chance. Care and accuracy in the design process show respect towards the consumer.

- is environmentally friendly – Design makes an important contribution to the preservation of the environment. It conserves resources and minimizes physical and visual pollution throughout the lifecycle of the product.

- is as little design as possible – Less, but better. Simple as possible but not simpler. Good design elevates the essential functions of a product.

Exhibitions and recognition

[edit]

Rams at the 50th Anniversary of Braun Innovation exhibition, Boston (2005)

Rams has been involved in design for seven decades and has received many honorary appellations throughout his career.[32]

- 1960: Received Kulturkreis im Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie

- 1961: TP1 portable record player and radio received Supreme Award at Interplas exhibition, London[33]

- 1963: F21 received ‘Supreme Award’ at Interplas exhibition, London

- 1965: Berliner Kunstpreise 'Bildende Kunst, Junge Generation' (with Reinhold Weiss, Richard Fischer, and Robert Oberheim)[34]

- 1968: Honorary Member, Royal Designers for Industry of the British Royal Society of Arts[35]

- 1969: 620 chair awarded gold medal at the International Furniture Exhibition in Vienna

- 1978: Awarded SIAD Medal of the Society of Industrial Artists and Designers, UK

- 1985: Awarded Académico de Honor Extranjero by the Academia Mexicana de Diseño, Mexico

- 1989: First recipient of the Industrie Forum Design Hannover, Germany, for special contribution to design

- 1989: Awarded Doctor honoris causa by Royal College of Art, London, UK

- 1992: Received Ikea prize and uses prize money for his own Dieter and Ingeborg Rams Foundation for the promotion of design

- 1996: Received World Design Medal from the Industrial Designers Society of America

- 2002: Awarded Commander's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (German: Verdienstkreuz des Verdienstordens der Bundesrepublik Deutschland)[10]

- 2003: Received Design Award ONDI, Havana, Cuba for his special contribution to industrial design and world culture[_citation needed_]

- 2007: Awarded Design Prize of the Federal Republic of Germany for his life’s work[36][37]

- 2007: Received Lucky Strike Designer Award [de] from the Raymond Loewy Foundation

- 2009: Awarded the great design prize in Australia.[_clarification needed_]

- 2010: Kölner Klopfer prize awarded by the students of the Cologne International School of Design

- 2012: Reddot design award and iF product design award, for the BN0106 digital chronograph[38]

- 2013: Awarded Lifetime Achievement Medal at London Design Festival

- 2014: Compasso d'Oro Career Award from the Associazione per il Disegno Industriale (ADI), Milan[39]

- 2024: He became the first recipient of the iF design lifetime-achievement award

- 2024: DesignEuropa lifetime achievement award[40]

Less and More exhibition

[edit]

Less and More is an exhibition of Rams's landmark designs for Braun and Vitsœ. It first traveled to Japan in 2008 and 2009,[41] appearing at the Suntory Museum in Osaka and the Fuchu Art Museum in Tokyo. Between November 2009 and March 2010 it appeared at the Design Museum in London.[42][43] It appeared at the Museum für Angewandte Kunst in Frankfurt from July to September 2010.[44][45] The exhibit then appeared at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art from August 2011 to February 2012.[46]

On 22 June 2016, filmmaker Gary Hustwit[47] announced his documentary Rams and launched a Kickstarter campaign for the project. The full-length documentary features in-depth conversations with Rams about his design philosophy, the process behind some of his most iconic designs, his inspiration and his regrets. Some of the funds raised in the Kickstarter campaign also helped to preserve Rams's design archive in cooperation with the Dieter and Ingeborg Rams Foundation.[48]

Dieter Rams. Modular World

[edit]

In 2016, the Vitra Design Museum staged an exhibition titled "Dieter Rams. Modular World" focusing on Rams "obsession with grids and shelving".[49]

Dieter Rams. A Style Room

[edit]

In 2022, the Museum für Angewandte Kunst in Frankfurt updated and expanded its permanent display titled "Dieter Rams. A Style Room" to mark the designer's 90th birthday. The exhibit also includes photographs by his wife, Ingeborg Rams.[50]

Dieter Rams. Looking back and ahead exhibition

[edit]

In 2021 an exhibition of approximately 30 works, 100 photographs, and information panels opened at the Museum Angewandte Kunst.[51][52] The exhibit was subsequently on view at the Goethe Institute in New York in 2022,[53] and the ADI Design Museum in Milan in 2023.[54][55]

Braun SK 61 radiogram, 1956

Braun Transistor 1 radio, 1957- [

![Braun TP1 portable transistor radio and phonograph, 1959[56]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3f/DieterRamsTP1Perspective.jpg/100px-DieterRamsTP1Perspective.jpg) ](/wiki/File:DieterRamsTP1Perspective.jpg "Braun TP1 portable transistor radio and phonograph, 1959[56]")

](/wiki/File:DieterRamsTP1Perspective.jpg "Braun TP1 portable transistor radio and phonograph, 1959[56]")

Braun TP1 portable transistor radio and phonograph, 1959[56]

Braun LE 1 speaker, 1959

Vitsœ Model 601 lounge chair, 1960

Vitsœ 606 Universal Shelving System, 1960

Vitsœ 620 Chair Programme, 1962

Braun tone arm scale, 1962

Braun TS 45, TG 60, L 450, 1964–1965

Braun T 1000 CD shortwave radio receiver, 1968- [

![Braun audio 310, early 1970s[57]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a4/Braun_audio_310.jpeg/120px-Braun_audio_310.jpeg) ](/wiki/File:Braun%5Faudio%5F310.jpeg "Braun audio 310, early 1970s[57]")

](/wiki/File:Braun%5Faudio%5F310.jpeg "Braun audio 310, early 1970s[57]")

Braun audio 310, early 1970s[57]

Braun Regie 510 stereo receiver, 1972

Braun Atelier series, 1979 to 1991

Braun lighter, early 1980s

Braun ABW 30 clock, 1982

Braun ET 66 calculator, 1987

- ^ "What is "Good" Design? A quick look at Dieter Rams' Ten Principles". Design Museum. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Lange, Alexandra (28 November 2018). "What We've Learned from Dieter Rams, and What We've Ignored". The New Yorker. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Dziersk, Mark (2 December 2012). "In tribute to Mr. Rams". Fast Company. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ a b c ""Design has to make things understandable"". Goethe-Institut. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ Fiell, Charlotte; Fiell, Peter (2005). Design of the 20th Century (25th anniversary ed.). Köln: Taschen. p. 591. ISBN 9783822840788. OCLC 809539744.

- ^ a b c d "Dieter Rams Biography". Vitsœ. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ "Hans Gugelot". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ a b Lovell, Sophie (22 November 2016). "Dieter Rams' modular designs open a world of possibilities at the Vitra Schaudepot". Wallpaper Magazine. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ What weve learned from Dieter Rams and what weve ignored The New Yorker 28 November 2018

- ^ a b c d Zuber, Anne (22 October 2010). "Ein Mann räumt auf" [A man cleans up]. Zeit Online (www.zeit.de) (in German). Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Master and commandments". Wallpaper (103). IPC Media: 321. October 2007. ISSN 1364-4475. OCLC 948263254.

- ^ "05 Good design is unobtrusive". Wallpaper (103). IPC Media: 331. October 2007. ISSN 1364-4475. OCLC 948263254.

- ^ Rams, Dieter. "606 Universal Shelving System". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Bentley, Daniel (16 March 2020). "The greatest designs of modern times". Fortune Magazine. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ Ling, Brian (19 January 2008). "Jonathan Ive, Design Genius or Something Else?". Design Sojourn. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ Wilson, Mark (1 September 2016). "The Irony Of Apple's War On Design Theft". Fast Company. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ Kosner, Anthony Wing. "Jony Ives' (No Longer So) Secret Design Weapon". Forbes. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ a b Lovell, Sophie; Klemp, Klaus (12 August 2021). "Looking back, and ahead". Vitsœ. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "Apple design and Dieter Rams". mac-history.net. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ "Design Classic: Dieter Rams' T3 radio". Financial Times. 5 February 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Dunning, Brad; Göksenin, Lili (16 May 2017). "This Massive Dieter Rams Braun Collection Is Pure Design Brilliance". GQ. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Design evolution". Braun GmbH. 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ "The Future Of Apple Is In 1960s Braun: 1960s Braun Products Hold the Secrets to Apple's Future". gizmodo.com. Gawker Media. 14 January 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "Jasper Morrison, The Minimalist". jaspermorrison.com. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "The Minimalist". Whitewall Magazine. February 2010.

- ^ "Design Icon: 10 Works by Jasper Morrison". Dwell. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "What is "Good" Design? A quick look at Dieter Rams' Ten Principles". Design Museum. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ "Dieter Rams and the 10 principles for a good design". www.domusweb.it. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ "SFMOMA Presents Less and More: The Design Ethos of Dieter Rams". Sfmoma.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ "The power of good design: Dieter Rams's ideology, engrained within Vitsœ". Vitsœ. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ "02 Good design makes a product useful". Wallpaper (103). IPC Media: 326. October 2007. ISSN 1364-4475. OCLC 948263254.

- ^ "Vitsœ History". Vitsœ. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ "01 Design is innovative". Wallpaper (103). IPC Media: 324–325. October 2007. ISSN 1364-4475. OCLC 948263254.

- ^ "Berliner Kunstpreise 1965 übergeben im Charlottenburger Schloß". www.bild.bundesarchiv.de. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ "Current Honorary Royal Designers for Industry, Dieter Rams, Electrical Appliances & Furniture,1968". The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Dieter Rams Timeline | Wright: Auctions of Art and Design". www.wright20.com. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ "Awards". rams foundation (in German). Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ "BRAUN collection Clocks". PHORMA SRL. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ^ "ADI – Associazione per il Disegno Industriale". www.adi-design.org. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ "Transparent turntable and cantilevered holiday home among DesignEuropa Awards 2024 finalists". Dezeen. 17 July 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Less and More: the design ethos of Dieter Rams in Japan". Vitsœ. 15 September 2008. Archived from the original on 6 April 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "'Less and More' at London's Design Museum". Vitsœ. 4 December 2009. Archived from the original on 21 November 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "Less and More – The Design Ethos of Dieter Rams". Designmuseum.org. 18 November 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "Less and More in Frankfurt". Vitsœ. 19 April 2010. Archived from the original on 11 May 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "Less and More – Das Designethos von Dieter Rams (requires Flash)". Angewandtekunst-frankfurt.de. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "'Less and More': The Design Ethos of Dieter Rams". SFMoMa.com. 27 August 2011. Archived from the original on 13 September 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ^ "Rams Film Update". hustwit.com. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ "RAMS: The First Feature Documentary About Dieter Rams". kickstarter.com. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ Sammicheli, Marco (12 December 2016). "Dieter Rams at the Vitra Design Museum". Abitare. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Dieter Rams. A Style Room / Museum Angewandte Kunst". www.museumangewandtekunst.de. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ "Interview with Prof. Dr. Klaus Klemp on the work of Dieter Rams". Stylepark. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ "Dieter Rams: Looking Back and Ahead". Museum Angewandte Kunst. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ "Exhibition: Dieter Rams A Look Back and Ahead – Goethe-Institut USA". Goethe Institut. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Kiran Piotti, Cristina (8 May 2023). "Less but better: Dieter Rams' lessons on show at ADI Design Museum, Milan". wallpaper.com. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ "The works of Dieter Rams on show in Milan". www.domusweb.it. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ "Dieter Rams. Portable Transistor Radio and Phonograph model TP 1 (1959)". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "braun audio 310 classical stereo systems from the 70s by Dieter Rams". Braun Audio. 13 January 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- Official website

- Dieter Rams interview with Alessandro Mendini (Domus magazine)

- Dieter Rams – A brave new world of Product Design (documentary interview by the Victoria and Albert Museum)