Major Jenney Garners a Salute (original) (raw)

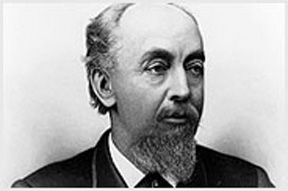

On June 15th, 1907, William Le Baron Jenney suffered twin indignities. The first, he found himself in Los Angeles, the second, he died. He has remained dead now, give or take a week or so, for one hundred years.

Celebrating the anniversary of someone's death is something you'd think you'd wish only on an enemy, but we're always looking for any excuse for a good party. If a birthday isn't available in a large round number, a death can be made to make do.

So over the next few weeks, we're saying a big, "Here's to you, WLJ," with a series  of events that commemorate the 100th anniversary of Jenney's passing, including a Saturday symposium at the Chicago History Museum, the dedication of a new Jenney monument at Graceland Cemetery, and a series of lectures at the Chicago Architecture Foundation.

of events that commemorate the 100th anniversary of Jenney's passing, including a Saturday symposium at the Chicago History Museum, the dedication of a new Jenney monument at Graceland Cemetery, and a series of lectures at the Chicago Architecture Foundation.

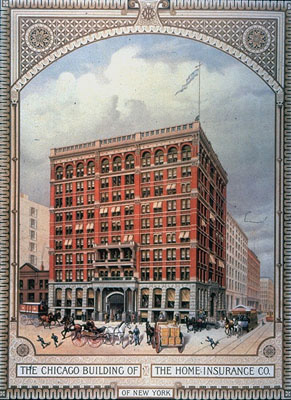

Jenney's major claim to fame is as "The Father of the Skyscraper." Leroy Buffington may have been the first to patent the idea of a metal-frame building, but Jenney was the one who got it done, in the 1884 Home Insurance Building. His partner William B. Mundie said Jenney first saw the possibilities of frame construction while visiting the Philippines aboard one of his father's fleet of whaling vessels. It was there, according to historian Carl Condit, that he found houses constructed by "using whole tree trunks as columns and split trunks as beams, joists and diagonal braces in a complete framing system." And, then course, there was the precedent of the simple balloon frame house, which had become a staple in Chicago construction.

Jenney himself told a much more engaging story, recounted in Sixty Years A Builder, the autobiography of legendary Chicago contractor Henry Ericsson, for whom my great-grandfather, Peter Warner, served as a construction foreman. Faced with a wildcat strike of bricklayers, "Jenny, sick at heart, closed his rolltop desk . . . and left in the middle of the afternoon for his home in Bittersweet place. So unusual was this that Mrs. Jenney could only surmise that he must be ill, and as she rose to greet him she found no immediately convenient place to lay the heavy book she was reading. Inadvertently she laid it down on top of a bird cage which stood on a table. . . . An inspiration struck Jenny: if so frail a frame of wire would sustain so great a weight without yielding, would not a cage or iron or steel serve as a frame for a building?"

Fives years before Home Insurance, Jenney had completed the first Leiter Building,  which could be considered the halfway house between the Philippines and the bird cage. According to historian Carl Condit, its five floors and roof were carried on timber girders and joists, which were, in turn, supported on cast iron columns. The widely spaced exterior brick piers carried only their own weight, not that of the building, and framed triplets of large, almost floor-to-ceiling windows, made the Leiter, in Condit's words, "very nearly a glass box."

which could be considered the halfway house between the Philippines and the bird cage. According to historian Carl Condit, its five floors and roof were carried on timber girders and joists, which were, in turn, supported on cast iron columns. The widely spaced exterior brick piers carried only their own weight, not that of the building, and framed triplets of large, almost floor-to-ceiling windows, made the Leiter, in Condit's words, "very nearly a glass box."

Condit called Jenney's Home Insurance Building "the decisive step in the evolution of iron and steel framing . . . The frame consisted of a serial column-and-beam system made up of cylindrical cast-iron columns, wrought-iron box columns of built-up section, and wrought-iron and steel I-beams joining them to receive the floor loads." During construction, Bessemer steel production was finally looking for markets beyond the fabrication of rails, and so above the sixth floor, for the first time, it came to be used for beams and girders. The completed structure weighed only a third as much as one constructed of masonry. The "first skyscraper" was only 10 stories - 138 feet - high, although an additional two stories were added in 1891.

production was finally looking for markets beyond the fabrication of rails, and so above the sixth floor, for the first time, it came to be used for beams and girders. The completed structure weighed only a third as much as one constructed of masonry. The "first skyscraper" was only 10 stories - 138 feet - high, although an additional two stories were added in 1891.

The Home Insurance Building was a bit too fussy for purists like Condit - too much ornament, and the string courses dividing it into five sections obscured the power of its verticality - but while others talked and dreamed, Jenney built. "For the first time since bricks were burned in history's early dawn," marveled Ericsson, "men were laying brick walls that were only curtains . . . a metal frame now supported both floors and building load."

Still, Jenney is often the Rodney Dangerfield of the great Chicago school architects. In the words of Louis Sullivan, "The Major was a free-and-easy cultured gentleman, but not an architect except by courtesy of terms. His true profession was that of engineer. He had received his technical training, or education, at the Ecole Polytechnique in France."

Jenney was born in 1832 in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, into a prosperous family whose patriarch owned a shipping company. During the Civil War, Jenney served on the engineering staff of Ulysses S. Grant. According to Ericsson, "In a few hours of the night after the battle of Champion Hills at Vicksburg, [Jenney] had bridged the Black river, and by dawn a division of Grant's army, with artillery and baggage wagons, had crossed in safety. . . . So proficient was Jenny that, in connection with  Sherman's March to the Sea, a Southern newspaper stated that it was useless for the retreating armies to burn the railroad bridges because Sherman carried a fully line of ready-built bridges with him!"

Sherman's March to the Sea, a Southern newspaper stated that it was useless for the retreating armies to burn the railroad bridges because Sherman carried a fully line of ready-built bridges with him!"

In his Autobiography of an Idea, Sullivan immortalized Jenney's outsize personality. "He spoke French with an accent so atrocious that it jarred Louis's teeth, while his English speech jerked about as though it had St. Vitus's dance. He was monstrously pop-eyed, with hanging mobile features, sensuous lips . . . not, really, in his heart, an engineer at all, but by nature, and in toto, a bon vivant, a gourmet. . . . Louis often smiled to see him carry home by their naked feet, with all plumage, a brace or two of choice wild ducks, or other game birds, or a rare and odorous cheese from abroad."

"And the Major knew his vintages, every one, and his sauces, every one; he was also a master of the chafing dish and the charcoal grille. . . . a welcome guest anywhere, but by preference a host . . . an excellent raconteur. . . he squeaked or blew, or lost his voice, or ran in arpeggio from deep bass to harmonica, or took octaves, or fifths, or sevenths, or ninths in spasmodic splendor. His audience roared."

Jenney knew talent, and many of the high luminaries of the first Chicago School passed through his office, among them both Martin Roche and William Holabird, John Edelmann, and Sullivan himself, who wrote: "In the Major's absences, which were frequent and long, bedlam reigned. John Edelmann would mount a drawing table and make a howling stump speech on greenback currency, or single tax, while at the same time Louis, at the top of his voice, sang elections from the oratorios, beginning with his favorite, "Why Do the Nations so Furiously Rage  Together." and so all the force furiously raged together in joyous deviltry, and bang-bang-bang . . . The office rat suddenly appears: "Cheese it, Cullies; the Boss!"

Together." and so all the force furiously raged together in joyous deviltry, and bang-bang-bang . . . The office rat suddenly appears: "Cheese it, Cullies; the Boss!"

One of Jenney's earliest draftsmen was a young and unfocused Daniel Burnham. Jenney's words of encouragement led him to declare, "For the first time in my life I feel perfectly certain that I have found my vocation." (Which didn't stop him from bolting Jenney's office in 1869 to travel to Nevada for two failed diversions - as prospector [Jenney, himself, as a young man had gone to California in 1849 for the Gold Rush] and as political candidate - but once he got that out of his system and returned to Chicago to pair up with John Wellborn Root, it all turned out rather well.)

You can't look at the broad thoroughfares of Burnham's 1909 Plan of Chicago without thinking of the great garlands of parks and boulevards Jenney laid out in the 1870's as landscape architect for the western division parks commission (Humboldt, Garfield, and Douglas), even as Frederick Law Olmsted, who had been impressed by Jenney's abilities when they first met during the Siege of Vicksburg, took on what would become Jackson Park to the south. Jenney also did his part for the gestation of urban sprawl by designing buildings, including the historic water tower, for Olmsted and Vaux's railroad suburb of Riverside "one of the first planned communities"

While the Major was capable of great simplicity - see his Second Leiter Building from 1891, a designated landmark still surviving on State Street between Van Buren and Congress, or the stunning 1891 Ludington Building at 1104 S. Wabash, beautifully restored by Columbia College - looking across the wide range of his work it's clear he considered stylistic consistency the hobgoblin of uncongenial minds. You can see antecedents for all the basic principles of Mies's Second Chicago School in his work, but it's often wrapped up in the conservative conventions of his time.

To my mind, one of the best jokes in architecture - and I cherish the hope that the Major may have actually intended it - is in Jenney's Manhattan Building at Dearborn and Congress. Its sixteen story height made it one of the world's tallest at the time of  its 1891 completion, yet it is hardly a "soaring thing, rising in exultation" - but, instead, solid and stout - more like a prosperous Dutch burgher after a week of banquets.

its 1891 completion, yet it is hardly a "soaring thing, rising in exultation" - but, instead, solid and stout - more like a prosperous Dutch burgher after a week of banquets.

It's a battleship of a building, its bulk deflecting contemporary fears of skyscrapers. (The Home Insurance's construction was briefly suspended while city safety inspectors conducted an investigation to certify it wouldn't simply collapse into the street). The facades of the top thirteen stories pile brick upon brick, and in turn, are nestled securely atop two floors of massive-looking rusticated granite. At the entry level, however, the entire mountainous heap dangles above a wall made almost entirely of glass, with flat, thin metal surround panels. "Goodness knows," the Major seems to be saying, "we all love our brick and stone, myself included. So here's fifteen full floors of it. To keep us all comfortable. But just between you and me, it's window dressing. See where you walk through the door? Where those huge panes of glass and a few plates of metal seem to be the only thing holding the whole pile up? Now that's the real thing."

"Goodness knows," the Major seems to be saying, "we all love our brick and stone, myself included. So here's fifteen full floors of it. To keep us all comfortable. But just between you and me, it's window dressing. See where you walk through the door? Where those huge panes of glass and a few plates of metal seem to be the only thing holding the whole pile up? Now that's the real thing."

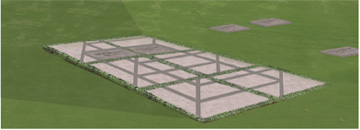

Jenney wasn't a purist. I doubt he ever let a mundane truth get in the way of a good story, and in that tradition the new monument, designed by DePree Bickford  Associates, that will be dedicated this Saturday, June 9th, at 2:30 P.M. at Graceland Cemetery marks, not his own grave, but that of his wife, Elizabeth Hannah Cobb, over which his own ashes were scattered after his death.

Associates, that will be dedicated this Saturday, June 9th, at 2:30 P.M. at Graceland Cemetery marks, not his own grave, but that of his wife, Elizabeth Hannah Cobb, over which his own ashes were scattered after his death.

Join a discussion on this story.

© Copyright 2007 Lynn Becker All rights reserved.