The Architecture of Dreams and Waking (original) (raw)

[April 3, 2007] ON THE 4700 block of North Broadway two wooden doors, one white and one black, stand in ornamental frames topped by broken pediments. The  long walls they once centered have been removed. The completely gutted first-floor space behind them—old metal, bare concrete floor, raw brick—is open to the street. Only the two doors remain, surreal portals. Remnants meet rehab. Welcome to Uptown.

long walls they once centered have been removed. The completely gutted first-floor space behind them—old metal, bare concrete floor, raw brick—is open to the street. Only the two doors remain, surreal portals. Remnants meet rehab. Welcome to Uptown.

Walking its streets can, at times, feel like wading through a hallucination. The exuberant flapper Baroque architecture, amiably pompous and determined to impress, faded, failing, cracking from the vise-like insinuation of tendrils of lowered circumstance and abandonment.

Through the 1920s Uptown experienced a building boom that had some speculating that the neighborhood might eclipse the Loop, just as midtown Manhattan was overtaking the island’s older downtown to the south. Then, like a switch being thrown, the Depression abruptly halted development and Uptown entered a period of decline that would last almost the rest of the century.

On Sheridan Road north of Montrose, you can still see some of the mansions, run- down and often derelict, that sprang up after the first Uptown subdivision was laid in 1894. Situated on land that had once been marshes and sand dunes, the neighborhood offered a retreat from the often filthy industrial city center. Then in 1896 came the Clark Street streetcar line. Four years later the Northwestern Elevated Railroad began service, terminating at Wilson Avenue.

down and often derelict, that sprang up after the first Uptown subdivision was laid in 1894. Situated on land that had once been marshes and sand dunes, the neighborhood offered a retreat from the often filthy industrial city center. Then in 1896 came the Clark Street streetcar line. Four years later the Northwestern Elevated Railroad began service, terminating at Wilson Avenue.

The population swelled. The not-so-old mansions were soon replaced by huge luxury hotels; the grandest was Walter W. Ahlschlager’s $2 million, 12-story  Sheridan Plaza at Wilson and Sheridan, which for its 1920 opening assembled a staff that included veterans of some of the best hotels in Vienna, Paris, and New York. Elegant homes with expansive lawns fell to large apartment blocks built to the lot line, which attracted an influx of young singles that turned the intersection of Broadway and Lawrence into a nightlife mecca, crammed with restaurants, movie houses, clubs, bars, and ballrooms.

Sheridan Plaza at Wilson and Sheridan, which for its 1920 opening assembled a staff that included veterans of some of the best hotels in Vienna, Paris, and New York. Elegant homes with expansive lawns fell to large apartment blocks built to the lot line, which attracted an influx of young singles that turned the intersection of Broadway and Lawrence into a nightlife mecca, crammed with restaurants, movie houses, clubs, bars, and ballrooms.

As the great hotels and apartment blocks deteriorated in the 1950s, however, apartments were subdivided, maintenance was deferred, and rents were lowered. Uptown became a refuge for the city’s dispossessed—the poor and elderly, the immigrants, and the mentally ill. Today those residents and gentrifying newcomers share an uneasy cohabitation. Moving down Broadway, Wilson Avenue is like an economic equator: the poor gravitate to the south, the upwardly mobile to the north.

You can trace Uptown’s churning fortunes in a single triangular block bounded by  Racine, Broadway, and Leland. At the north end is the classically styled Sheridan Trust and Savings Bank Building, with its Corinthian-columned entrance and arcades of huge arched windows. Just to the south, in elegant white terra-cotta, is the five-story Loren Miller department store, dating from 1915. At the south end of the block was the 1912 Plymouth Hotel, whose guests were said to include Gloria Swanson and Charlie Chaplin when Uptown’s Essanay Studios, the headquarters of which still stands nearby at 1333-45 W. Argyle, was a major player in producing silent movies.

Racine, Broadway, and Leland. At the north end is the classically styled Sheridan Trust and Savings Bank Building, with its Corinthian-columned entrance and arcades of huge arched windows. Just to the south, in elegant white terra-cotta, is the five-story Loren Miller department store, dating from 1915. At the south end of the block was the 1912 Plymouth Hotel, whose guests were said to include Gloria Swanson and Charlie Chaplin when Uptown’s Essanay Studios, the headquarters of which still stands nearby at 1333-45 W. Argyle, was a major player in producing silent movies.

By 1926 Sheridan Trust had moved across the street into an even grander edifice, Marshall and Fox’s Uptown Bank Building; it’s now the Bridgeview Bank, but you can still see the S in a grill above the stairs that also includes the Sheridan’s coat of arms.

can still see the S in a grill above the stairs that also includes the Sheridan’s coat of arms.

Loren Miller had expanded into the Sheridan’s old space and bought out the Plymouth, renaming it the Uptown Hotel. Five years later Loren Miller was itself bought out by Goldblatt’s, Chicago’s archetypal discount department store. A large illuminated clock was erected above the Sheridan’s former entrance, the great windows of both buildings were boarded up, and decade by decade the facades became grimier and more decrepit. The store was finally closed in 1998, when Goldblatt’s gave up the ghost to national megadiscounters like Target and Kmart.

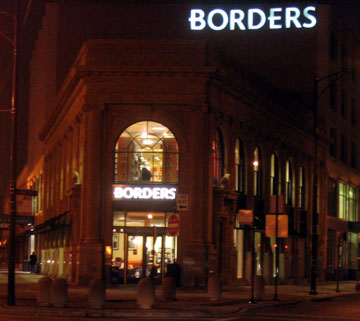

The following year the block was purchased by Palatine developer Joseph Freed and Associates, who’s currently trying to find tenants to replace Carson Pirie Scott in Louis Sullivan’s architectural masterpiece on State Street.  Architects Hartshorne & Plunkard were enlisted for a $24.3 million redevelopment of the block, now named Uptown Square. After a brief battle with preservationists, Freed won the right to demolish the hotel, replacing it with a depressingly bland two-story structure. At Goldblatt’s, the clock, the garish signs, and all the other vulgar accumulations of the decades have been stripped away as the facades have been restored to their original condition. Once again there’s glass in the huge windows, streaming light into the interior by day and radiating it back onto the street at night. Inside, it’s pretty much boilerplate modern retail—Borders is the current occupant—but outside you can imagine Uptown at the peak of its grandeur.

Architects Hartshorne & Plunkard were enlisted for a $24.3 million redevelopment of the block, now named Uptown Square. After a brief battle with preservationists, Freed won the right to demolish the hotel, replacing it with a depressingly bland two-story structure. At Goldblatt’s, the clock, the garish signs, and all the other vulgar accumulations of the decades have been stripped away as the facades have been restored to their original condition. Once again there’s glass in the huge windows, streaming light into the interior by day and radiating it back onto the street at night. Inside, it’s pretty much boilerplate modern retail—Borders is the current occupant—but outside you can imagine Uptown at the peak of its grandeur.

Today the neighborhood is a museum of urban flux, grandeur and decay, adaptation and rebirth. You can still see traces of the elegant 1923 beaux arts-style Uptown  Station, which replaced Frank Lloyd Wright’s Stohr Arcade Building of 1909, but these days it’s just the Wilson stop on the Red Line. The adjacent trestle for the North Shore Line has been rotting since 1963, the year service shut down. In the 1950s the station’s spacious waiting room was converted to retail, including a supermarket. The majestic arched parapet crowning the primary corner entrance was dismantled, the entrance itself sealed up. The space is currently occupied by a Popeyes.

Station, which replaced Frank Lloyd Wright’s Stohr Arcade Building of 1909, but these days it’s just the Wilson stop on the Red Line. The adjacent trestle for the North Shore Line has been rotting since 1963, the year service shut down. In the 1950s the station’s spacious waiting room was converted to retail, including a supermarket. The majestic arched parapet crowning the primary corner entrance was dismantled, the entrance itself sealed up. The space is currently occupied by a Popeyes.

A lot of buildings in Uptown have a similar story. On Wilson just east of the station is a TGF branch that is but the latest in a series of banks that since 1922 have made  their home in what was originally the Standard Vaudeville Theatre, built in 1905. Walk inside and you’ll find a surprisingly large room lined with richly ornamented terra-cotta pilasters and spandrels. That gutted structure on Broadway with the two freestanding doors? That’s Ahlschlager’s 80-year-old Uptown Broadway Building, whose upper floors are encrusted in a riotous, Spanish-baroque-inspired hallucination of polychromatic terra-cotta. It’s in the midst of a $4 million restoration to its original overwrought splendor.

their home in what was originally the Standard Vaudeville Theatre, built in 1905. Walk inside and you’ll find a surprisingly large room lined with richly ornamented terra-cotta pilasters and spandrels. That gutted structure on Broadway with the two freestanding doors? That’s Ahlschlager’s 80-year-old Uptown Broadway Building, whose upper floors are encrusted in a riotous, Spanish-baroque-inspired hallucination of polychromatic terra-cotta. It’s in the midst of a $4 million restoration to its original overwrought splendor.

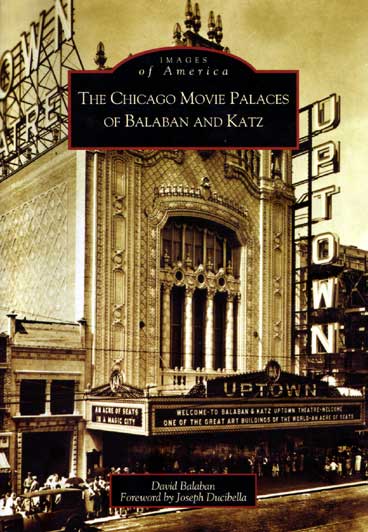

The challenges facing historic Uptown may best be represented, however, in its great namesake monument, the Uptown Theatre, dating from 1925. Constructed at a cost of $4 million in a deliriously eclectic style that a contemporary reporter called “Spanish Mexican Renaissance,” it covers 46,000 square feet (most of a city block), stands eight stories high, and seats 4,300. By the end of its first decade, nearly 20 million people had passed through the 213-foot-long lobby, which is terminated by a curving double stair and lined with twin colonnades rising to a 92-foot-high ceiling. As detailed in The Chicago Movie Palaces of Balaban and Katz by David Balaban, namesake grandson of the Uptown’s manager, the theater occupied a rare moment of shared democracy, where anyone with a quarter or 50 cents could spend a couple hours steeped in the sort of luxury usually reserved for the ultrarich, attended to by a small army arrayed in at least eight different styles of uniforms, designating every station from floor manager to page boy to footman. So as not to disturb the patrons, ushers had to master a complex set of hand signals to manage the huge crowds.

David Balaban, namesake grandson of the Uptown’s manager, the theater occupied a rare moment of shared democracy, where anyone with a quarter or 50 cents could spend a couple hours steeped in the sort of luxury usually reserved for the ultrarich, attended to by a small army arrayed in at least eight different styles of uniforms, designating every station from floor manager to page boy to footman. So as not to disturb the patrons, ushers had to master a complex set of hand signals to manage the huge crowds.

By the 1960s, of course, we had begun opting for a no-frills, self-service, lowest-price world. Blitzed by free TV, the great movie palaces crashed into dust. The Uptown held on, finally closing for good in 1981. The heat was turned off soon after, and in the dead of winter the water pipes froze and burst, causing massive damage. It’s gone downhill ever since. The theater has passed through multiple owners, including convicted slumlord Lou Wolf, who once owned the Goldblatt’s block, and is currently in receivership. Recently the  city picked up the tab for $500,000 in emergency repairs, removing some large, unstable chunks of terra-cotta before they simply fell to the street. Despite the ongoing efforts of activists committed to saving this official Chicago landmark, the Uptown remains boarded up and forlorn. Just before the February election, the 48th Ward alderman Mary Ann Smith told Windy City Times that a “premier developer” had signed a contract to restore the theater but declined to divulge the company’s name.

city picked up the tab for $500,000 in emergency repairs, removing some large, unstable chunks of terra-cotta before they simply fell to the street. Despite the ongoing efforts of activists committed to saving this official Chicago landmark, the Uptown remains boarded up and forlorn. Just before the February election, the 48th Ward alderman Mary Ann Smith told Windy City Times that a “premier developer” had signed a contract to restore the theater but declined to divulge the company’s name.

The shuttered theater, Borders, and some persistently empty storefronts may mark off its embattled core, but there’s a lot more to Uptown than Broadway and Lawrence. There are lake-hugging high-rises to the east and upscale homes to the west. To the south stands architect Stanley Tigerman’s 1981 Pensacola Place, a graceful reminder of the  fleeting fad of postmodernism at its best. There’s more faux Spanish embellishment (was Uptown founded by conquistadors?) in the fabled Aragon Ballroom west of Broadway on Lawrence. There’s the landmark Hutchinson Street District, just off Marine Drive between Montrose and Irving Park, with its handsome turn-of-the-century homes by architect George Maher.

fleeting fad of postmodernism at its best. There’s more faux Spanish embellishment (was Uptown founded by conquistadors?) in the fabled Aragon Ballroom west of Broadway on Lawrence. There’s the landmark Hutchinson Street District, just off Marine Drive between Montrose and Irving Park, with its handsome turn-of-the-century homes by architect George Maher.

Consistent with its history, Uptown's current revival keeps threatening to double back on itself. On Broadway, under the L, there's the closed First Lao Grocery.  Apparently there's not going to be a second. Last February, after 47 years, the Uptown Snack Shop was forced out of business. More than a year after its eviction, its interior remains a gutted, ugly shell. A proposal to build a Target on the site of the old Wilson Yards where Red Line trains were stored and repaired has lingered unfilled for years. And that sparkling new Borders? The troubled chain is already looking to get out of its lease.

Apparently there's not going to be a second. Last February, after 47 years, the Uptown Snack Shop was forced out of business. More than a year after its eviction, its interior remains a gutted, ugly shell. A proposal to build a Target on the site of the old Wilson Yards where Red Line trains were stored and repaired has lingered unfilled for years. And that sparkling new Borders? The troubled chain is already looking to get out of its lease.

But that's Uptown, chronically overpopulated and unsettled at the same time, where tranquility is to be found only in death. In the southwest corner, at Clark and Irving Park, lies one of it’s lesser-known treasures: Graceland, the cemetery of the architects. There’s no Elvis, but there are two stunning tombs, the Getty and the Ryerson, designed by Louis Sullivan, who himself is buried here under a rustic boulder. His nemesis, Daniel “Make No Little Plans” Burnham, is interred on his own island, while Burnham’s great partner, John Wellborn Root, lies beneath a simple, carved Celtic cross. Dwight Perkins, whose handsome 1907 Graeme Stewart School, just off Broadway on Kenmore, is an Uptown landmark, is buried here, as is Richard Nickel, the architectural photographer who died documenting the destruction of Sullivan’s Stock Exchange Building. So are Fazlur Khan, the engineer behind the Sears Tower and the Hancock Building, and Mies van der Rohe, father of the second Chicago school of architecture.

the cemetery of the architects. There’s no Elvis, but there are two stunning tombs, the Getty and the Ryerson, designed by Louis Sullivan, who himself is buried here under a rustic boulder. His nemesis, Daniel “Make No Little Plans” Burnham, is interred on his own island, while Burnham’s great partner, John Wellborn Root, lies beneath a simple, carved Celtic cross. Dwight Perkins, whose handsome 1907 Graeme Stewart School, just off Broadway on Kenmore, is an Uptown landmark, is buried here, as is Richard Nickel, the architectural photographer who died documenting the destruction of Sullivan’s Stock Exchange Building. So are Fazlur Khan, the engineer behind the Sears Tower and the Hancock Building, and Mies van der Rohe, father of the second Chicago school of architecture.

In 1916, Carl Sandburg, who lived in Uptown from 1911 to 1914 in a house at 4646 N. Hermitage that was recently designated a Chicago landmark, wrote a poem called Graceland. It includes these lines:

TOMB of a millionaire,

A multi-millionaire, ladies and gentlemen,

Place of the dead where they spend every year

The usury of twenty-five thousand dollars

For upkeep and flowers

To keep fresh the memory of the dead . . .(A hundred cash girls want nickels to go to the movies to-night.

In the back stalls of a hundred saloons, women are at tables

Drinking with men or waiting for men jingling loose silver dollars in their pockets.

In a hundred furnished rooms is a girl who sells silk or dress goods or leather stuff

for six dollars a week wages . . .

Today as in Sandburg’s time, that’s a pretty good summation of Uptown—its people, its contradictions, and its architecture.

Join a discussion on this story.

© Copyright 2007 Lynn Becker All rights reserved.