MRG15 Regulates Embryonic Development and Cell Proliferation (original) (raw)

Abstract

MRG15 is a highly conserved protein, and orthologs exist in organisms from yeast to humans. MRG15 associates with at least two nucleoprotein complexes that include histone acetyltransferases and/or histone deacetylases, suggesting it is involved in chromatin remodeling. To study the role of MRG15 in vivo, we generated knockout mice and determined that the phenotype is embryonic lethal, with embryos and the few stillborn pups exhibiting developmental delay. Immunohistochemical analysis indicates that apoptosis in _Mrg15_−/− embryos is not increased compared with wild-type littermates. However, the number of proliferating cells is significantly reduced in various tissues of the smaller null embryos compared with control littermates. Cell proliferation defects are also observed in _Mrg15_−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts. The hearts of the _Mrg15_−/− embryos exhibit some features of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The increase in size of the cardiomyocytes is most likely a response to decreased growth of the cells. _Mrg15_−/− embryos appeared pale, and microarray analysis revealed that α-globin gene expression was decreased in null versus wild-type embryos. We determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation that MRG15 was recruited to the α-globin promoter during dimethyl sulfoxide-induced mouse erythroleukemia cell differentiation. These findings demonstrate that MRG15 has an essential role in embryonic development via chromatin remodeling and transcriptional regulation.

Human MRG15 was first identified as a member of the MORF4/MRG family of novel transcription factors. MORF4 induces senescence in a subset of human tumor cell lines, is a truncated version of MRG15, and has 93% identity to MRG15 at the amino acid level (7). MORF4 lacks the chromodomain (CHR) present in the N-terminal region of MRG15 that has been implicated in protein-protein, as well as protein-RNA, interactions (2, 5, 12, 15, 30, 32, 35). MRG15 does not have the ability to induce senescence in tumor cells. MRG15 is down-regulated ∼3-fold at the protein level in senescent human cells, and our studies suggest that it acts in part to promote cell growth. We have shown that MRG15 activates the B-myb (Mybl2) promoter (37), which is generally thought to be repressed by an Rb/E2F/HDAC complex at the E2F site in this promoter (11, 36, 40, 51). B-myb is an essential protein for cell growth, and its promoter is activated in early G1 phase (36). We found that MRG15 associates with Rb in complex(es) (37, 47); therefore, one potential mechanism of MRG15 action is the inactivation of the inhibitory activity of Rb at Rb/E2F-regulated sites, thereby affecting gene expression and cell growth.

We have also demonstrated that there are at least two MRG15-containing complexes in human cells by fractionating nuclear proteins on a sucrose gradient (47). MRG15-associated factor 1 (MAF1) contains MRG15, Rb, and a novel small protein, PAM14, and association of MRG15 with this complex involves the leucine zipper motif. MAF2 is a larger complex that includes another MYST family histone acetyltransferase (HAT), hMOF (46), and this complex requires the CHR region of MRG15 for association. Interestingly, both the Rb and hMOF associations of MRG15 are required to derepress the B-myb promoter because deletion of either the CHR or leucine zipper region of MRG15 results in loss of activation (47).

MRG15 is a highly conserved protein and has orthologs in organisms from yeast to human (8, 41). In budding yeast, the MRG15 homologue, Eaf3p, is one of the components of the NuA4 HAT complex, which includes the MYST family HAT member Esa1 (3, 19). A NuA4-like HAT complex has also been identified in human cells (13, 17, 18); it is composed of many more protein components than that in yeast and includes MRG15 and TIP60 (an Esa1-related HAT) (13, 17, 18, 27). Recently, it has been shown that a similar complex exists in Drosophila and that the protein components are highly homologous to those found in yeast and human (34). Furthermore, deletion or knockdown by double-stranded RNA of either Drosophila Tip60 (dTip60) or Mrg15 (dMrg15) results in an embryonic-lethal phenotype. The dTip60- or dMrg15-depleted embryos and S2 cells are unable to repair double-strand DNA breaks following γ-irradiation, and the mechanistic basis is the inability of Tip60- or Mrg15-depleted cells or embryos to dephosphorylate and acetylate histone H2Av. Thus, MRG15 is an essential component for DNA repair activity of this complex.

In this report, we describe the characteristics of Mrg15 null mice, which we have generated using gene-targeting technology, to determine the function(s) of MRG15 in vivo. Deletion of MRG15 results in embryonic lethality, and the majority of the embryos die between embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) and birth. The null embryos are smaller than wild-type and heterozygous embryos, and the growth potential of _Mrg15_−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) is greatly reduced. The hearts of _Mrg15_−/− embryos exhibit some features of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, including myocardial disarray and cardiomyocyte enlargement, which is most likely a compensatory response to decreased cardiomyocyte growth potential. In addition, lung alveolar formation is impaired, the liver is congested, and the keratinocyte-epidermal layer in the skin is reduced in size. The effects of the elimination of Mrg15, therefore, do not appear to be merely the result of abnormal heart development, because a non-muscle myosin II-B knockout mouse exhibits many features in the heart and liver similar to those in the Mrg15 null embryos, but no major changes in lung or skin were observed in that study (58). Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), we have demonstrated an increased association of MRG15 at the α-globin promoter during induction of differentiation of mouse erythroleukemia (MEL) cells and expression of hemoglobin. The results provide evidence for the role of MRG15 in transcriptional regulation via chromatin remodeling, which impacts cell growth and differentiation during development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Western blot analysis.

Embryos at different times of gestation were isolated from pregnant C57BL/6J animals. Whole embryos at E10.5, E12.5, and E14.5 and embryonic tissues from E16.5 and E18.5 embryos were lysed with TNESV buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1% NP-40, 2 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 10 mM sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitor cocktail set I [Calbiochem]) (29). The lysates were kept on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 20,000 × . for 15 min. The protein concentrations of the supernatants were determined by the copper-bicinchoninic acid method with a Pierce Laboratory (Rockford, Ill.) kit. The total proteins (50 μg) were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. MRG15 was detected using rabbit anti-MRG15 antibodies raised by our laboratory. The antibodies were affinity purified using an antigen column, and their specificities were confirmed by Western blotting using lysates of cells expressing hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged MRG15. The anti-MRG15 and anti-HA antibodies detected the same protein band. Mouse anti-β-actin antibody (AC-15; Abcam) was used as a loading control. Total cell lysate (25 μg) from HeLa cells was used as a positive control.

MEFs were collected and lysed in TNESV buffer. MRG15 and p21 proteins were detected by Western blotting using rabbit anti-MRG15 and rabbit anti-p21 antibodies (sc-756; Santa Cruz).

An acid-histone extraction method was used to obtain histones from MEF cultures (16, 55). Cells were lysed in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)-150 mM NaCl-1.5 mM MgCl2-0.65% NP-40 and protease inhibitor cocktail set I and centrifuged at 1,000 × .. After three washes in lysis buffer, the nuclei were pelleted and extracted with 0.4 N H2SO4 on ice for 1 h, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × . for 5 min. Acid-soluble histones were precipitated with 10× volumes of acetone at −20°C overnight. The precipitated histones were collected by centrifugation, dried, and resuspended in distilled water. The histones were separated on SDS-15% PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with rabbit anti-acetyl-histone H4 (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. 06-598), anti-acetyl-histone H3 (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. 06-599), anti-histone H4 (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. 07-108), or anti-histone H3 (sc-10809; Santa Cruz) antibody.

Construction of the targeting vector.

We have previously reported the isolation of mouse Mrg15 genomic clones and the determination of Mrg15 gene structure (56). The replacement targeting vector to inactivate Mrg15 contained a 1.8-kb SalI-SphI (SalI from the λFIX II cloning vector) fragment for the 5′ homology arm; a PgkHPRT selectable marker cassette that replaced a 3.2-kb SphI-BamHI region of the locus, including exon 1 of the Mrg15 gene; a 7-kb BamHI-EcoRV fragment for the 3′ homology arm; and an MC1_tk_ expression cassette for negative selection. Twenty-five micrograms of ClaI-linearized targeting vector was electroporated into 107 AB2.2 embryonic stem (ES) cells. ES clones were selected in culture medium containing hypoxanthine-aminopterin-thymidine and 1-(2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-β-d-arabinofuranosyl)-5′-iodouracil. DNA from the clones was analyzed by Southern blotting, and targeted ES cell clones were expanded and injected into blastocysts as described previously (43).

Southern blot analysis.

Tail DNA or DNA from the yolk sac or parts of embryos was digested with BamHI at 37°C overnight. The digested DNAs were separated on a 0.7% agarose gel and transferred to Hybond N+ (Amersham Pharmacia) using an alkaline transfer method. The membrane was probed with the 3′ external or 5′ internal probe using Rapid Hybridization solution (Amersham Pharmacia).

Northern blot analysis.

RNAs were extracted from MEFs or E13.5 embryos using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the instruction manual. Ten micrograms of total RNA was separated on 1% agarose gels and transferred to a Hybond N+ membrane. The membrane was probed with either a MRG15-specific probe (56) or a mouse α-globin probe using HybriMax hybridization solution (Ambion) at 42°C overnight. The membrane was washed twice with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)-0.1% SDS solution for 15 min at 65°C and then washed once with 0.2× SSC-0.1% SDS solution for 15 min at 65°C.

Histology and immunohistochemistry.

Isolated embryos and newborn pups were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C overnight, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin wax. Serial sections (5 μm thick) were stained with hematoxylin-eosin.

For immunohistochemisty of PCNA or anti-single-stranded DNA, tissue sections (5 μm thick) were rehydrated and treated with 3% H2O2 for 10 min to inactivate endogenous peroxidase. After being blocked in 5% goat serum-PBS, the sections were stained with anti-single-stranded DNA antibody (1/100; Dako Japan, Kyoto, Japan) or biotinylated anti-PCNA (1/100; BD Pharmingen) for 1 h at room temperature. Secondary antibody incubation and enzymatic reactions were performed using the ABC and DAB staining kit (Vector Laboratories). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

For detection of growing cells in embryos, pregnant mice were intraperitoneally injected with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) (10 mg/ml in PBS) at 100 μg/g of body weight, and after 2 h, the mice were sacrificed. Embryos were isolated from the uterus, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS, and embedded in paraffin wax. Incorporated BrdU in embryos was detected with an in situ BrdU detection kit (BD Sciences) according to the instruction manual, and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. We used the following method for scoring BrdU-positive cells in the skin. In E14.5 embryos, we counted the cells in the epidermis using 400-fold magnification and determined the percentage of BrdU-positive cells. Ten different areas per embryo were analyzed. Statistical analysis was performed by the unpaired . test.

Generation of MEFs and analysis of growth properties.

MEFs were derived from 13.5-day-old wild-type Mrg15+/− and _Mrg15_−/− embryos. After removal of the head and intestinal organs, each embryo was washed with PBS and minced, and the tissue was placed in a 15-ml conical tube. After centrifugation, 1 ml of trypsin solution (0.25% trypsin-0.005% EDTA in PBS) was added, and the pelleted tissue was digested on ice overnight. The trypsin was inactivated by the addition of Eagle's minimum essential medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum-2 mM glutamine-0.1 mM nonessential amino acids-50 μg of gentamicin per ml. After the mixture was pipetted several times, the cells were counted with a Coulter Counter, and 200 cells from each preparation were used directly for colony formation assays. Then, 4 × 106 to 5 × 106 cells were plated in one T75 tissue culture flask and incubated at 37°C for 2 days. We designated this culture PD 0.

For the growth study, equal numbers (105) of PD 0 MEFs were plated in 60-mm-diameter tissue culture dishes, maintained in 5% CO2 at 37°C, and counted every 24 h (in triplicate) using a Coulter Counter.

For the colony formation assay, 200 cells were seeded in 60-mm-diameter tissue culture dishes in Eagle's minimum essential medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were incubated undisturbed for 14 days, fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and the number of cells per clone was determined microscopically.

Adenovirus infection.

The full-length human MRG15 fragment was cloned into the pShuttle vector, and MRG15 adenovirus (ad-MRG15) was produced by the Adeno-X Expression System. The ad-MRG15 was amplified, purified by two rounds of CsCl centrifugation, and subjected to titer determination. The adenovirus was produced by the core at Baylor College of Medicine, headed by Alan R. Davis.

Primary wild-type and _Mrg15_−/− MEFs (3 × 104) were seeded into 24-well plates and infected with and without ad-MRG15 (multiplicities of infection, 100 and 300) 24 h later. The cells were incubated with adenovirus for 24 h, washed with PBS three times, and labeled with 10 μM BrdU in culture medium for 16 h. Then, the cells were fixed and stained with anti-BrdU antibody. At least 100 cells were scored per MEF culture, and the percentage of BrdU-positive cells was determined.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

cDNAs were synthesized from E13.5 embryo total RNA (5 μg) by priming with 200 ng of random hexamer, 0.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 100 U of SuperScript II (Gibco BRL) at 42°C for 1 h. Real-time PCR for α-globin and β-actin was carried out using SYBR Green Reaction Mix (Applied Biosystems). The following primer sets were used; α-globin-5′ (5′-CCACCCTGCCGATTTCAC-3′) plus α-globin-3′ (5′-CTCACAGAGGCAAGGAATTTGTC-3′) and β-actin-5′ (5′-ACCAGTTCGCCATGGATGAC-3′) plus β-actin-3′ (5′-TGCCGGAGGCGTTGTC-3′). α-Globin expression levels were normalized to those of β-actin.

ChIP using MEL cells.

MEL (BB88) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC TIB-55) and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells (1 × 107 to 5 × 107/ChIP) were treated with 2% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 16 h or left untreated. After incubation, formaldehyde was added to the cell cultures to a final concentration of 1%, and the cultures were incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Glycine (0.125 M) was added to quench the reaction, and the cells were washed with PBS. The cells were suspended in 2 ml of SDS buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM EDTA plus protease inhibitor cocktail I) and pelleted again. They were resuspended in 2 ml of ice-cold immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (1 volume of SDS buffer plus 0.5 volume of Triton dilution buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.6], 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 5% Triton X-100) and subjected to sonication on ice to reduce the chromatin fragments to 500 to 1,000 bp. The final volume per IP reaction was adjusted to 1 ml with IP buffer, and 25 μl of salmon sperm DNA-protein A-agarose beads (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. 16-157) was added to each tube. The mixture was microcentrifuged at full speed for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was incubated with full-length rabbit anti-MRG15 or anti-HA (negative control) (sc-805; Santa Cruz) antibody overnight at 4°C on a rocking platform. An aliquot (25 μl) was removed from each tube prior to the addition of antibody as input (2.5%). Then, 30 μl of salmon sperm DNA-protein A-agarose was added, and incubation continued for an additional 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed twice with Low Salt Immune Complex Wash Buffer (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. 20-154), followed by High Salt Immune Complex Wash Buffer (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. 20-155), LiCl Immune Complex Wash Buffer (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. 20-156), and finally Tris-EDTA. DNA-protein cross-links were eluted and reverse cross-linked by incubation with elution buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3 and 1% SDS) overnight at 65°C. Two hundred fifty microliters of proteinase K solution (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 0.12 mg of glycogen/ml, and 0.4 mg of proteinase K/ml) was added, and the beads were further incubated at 65°C for 2 h. Fifty microliters of 4 M LiCl was added to the samples, and then the samples were extracted with phenol-chloroform. DNAs were precipitated with ethanol, washed once with 70% ethanol, and dissolved in 60 μl of Tris-EDTA. Real-time PCR quantification was performed with 3 μl of DNA solution and 0.8 μM primers to a final volume of 10 μl in SYBR Green Reaction Mix (Applied Biosystems). The primer sets were as follows: the α1-globin gene promoter (forward, 5′-TGACCAAGGTAGGAGGATACTAACTTCT-3′; reverse, 5′-TTGCCCGGACACACTTCTTAC-3′), the neuron-specific gene 2 exonic region (forward, 5′-ATCCTGCTGCTTGCCTTAGGT-3′; reverse, 5′-CTCTCCAGGGTTGCTGTTCAG-3′), and the β-actin gene promoter (forward, 5′-CGGTGTGGGCATTTGATGA-3′; reverse, 5′-CGTCTGGTTCCCAATACTGTGTAC-3′) (4). Fluorescence was monitored by a GeneAmp 7900HT Sequence Detection system (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR data analysis was performed by the methodology described previously (20).

RESULTS

MRG15 protein expression.

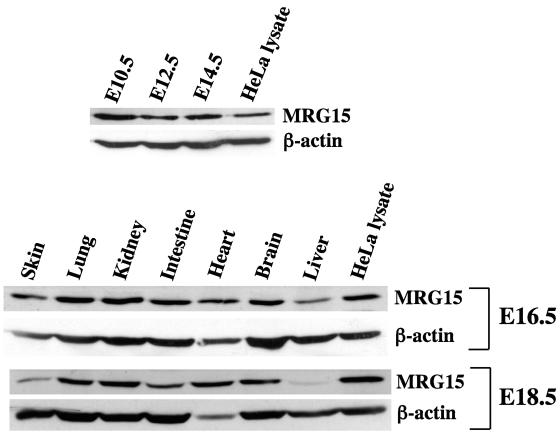

To determine MRG15 expression during mouse embryogenesis, whole embryo lysates at E10.5, E12.5, and E14.5 and various embryonic tissues at E16.5 and E18.5 were analyzed by Western blot analysis using an anti-MRG15 antibody (Fig. 1). The protein was expressed as early as E10.5 and in all tissues, though at various levels. These results were consistent with Northern blot data that we had obtained previously using RNA from adult human and mouse tissues (7, 56).

FIG. 1.

MRG15 expression during mouse development. Expression levels of MRG15 in whole embryos at E10.5, E12.5, and E14.5 (50 μg of total cell lysate) were determined by Western blotting. Total cell lysate (25 μg) from HeLa cells was used as a positive control. The blot was reprobed with an anti-β-actin antibody as a loading control. Expression levels of MRG15 in tissues from E16.5 and E18.5 embryos were determined by Western blotting under the same conditions.

Targeted disruption of Mrg15 causes embryonic lethality.

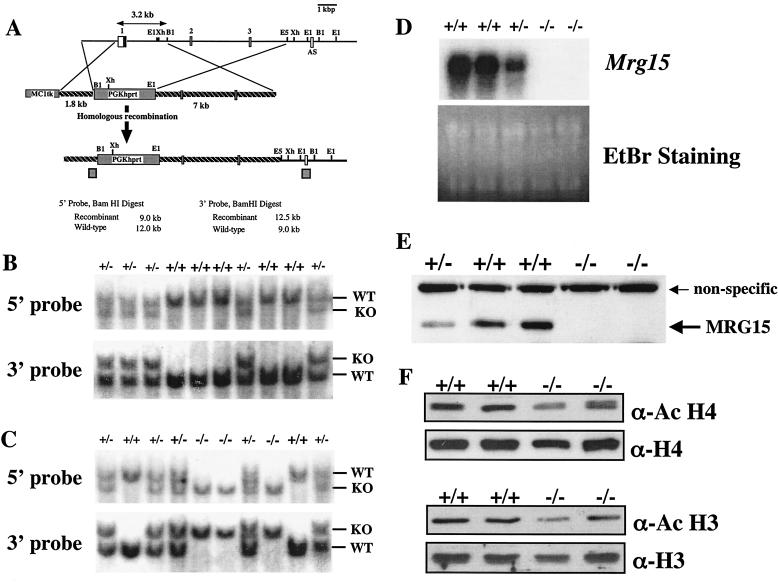

We generated a mutant allele of Mrg15 by homologous recombination in ES cells, deleting a 3.2-kb fragment of the Mrg15 gene that includes exon 1 (Fig. 2A). We expected that the targeted allele would not express MRG15 mRNA or protein because this 3.2-kb fragment of the Mrg15 gene includes the putative transcription start site(s) and the translation initiation site. Following electroporation of the targeting vector into ES cells and selection, we screened 96 ES clones and determined that 55 clones were correctly targeted at the Mrg15 locus. Heterozygous mice carrying the mutant allele were generated from two independent ES clones (_Mrg15_-151-E6 and _Mrg15_-151-C8), and we have confirmed that the mutant mice generated from both clones have the same phenotype.

FIG. 2.

Targeted disruption of the mouse Mrg15 gene. (A) Gene-targeting strategy to generate the Mrg15 mutant allele. The Mrg15 targeting vector was constructed by replacing a 3.2-kb region, which contains exon 1 and a part of intron 1 of the Mrg15 gene, with a PgkHPRT cassette. The regions of homology consist of 1.8 kb for the 5′ arm and 7 kb for the 3′ arm. The MC1_tk_ cassette was located next to the 1.8-kb 3′ homology arm. The probe fragments for genotyping are indicated as shaded boxes on the bottom. (E1) EcoRI; (Xh) XhoI; (B1) BamHI; (E5) EcoRV. (B) Southern blot analysis of tail DNA from pups from heterozygous intercrosses at weaning. Genomic DNAs were digested with BamHI and hybridized with 5′ or 3′ probes. Fragments that hybridized to the 5′ probe are 12 kb for the wild-type (WT) allele and 9 kb for the mutant (KO) allele. Fragments that hybridized to the 3′ probe are 9 kb for the WT allele and 12.5 kb for the KO. Wild-type (+/+), Mrg15+/− (+/−). (C) Southern blot analysis of BamHI-digested E14.5 embryo genomic DNA from heterozygous intercrosses. _Mrg15_−/− (−/−). (D) Northern blot analysis of Mrg15 expression in wild-type (+/+), Mrg15+/−, and _Mrg15_−/− MEFs. (E) Western blot analysis of MRG15 protein expression in wild-type, Mrg15+/− and _Mrg15_−/− MEFs. (F) Acetylation levels of histone H4 and H3 in wild-type (+/+) and _Mrg15_−/− MEFs.

Heterozygous mice were intercrossed, and offspring were generated. Genotype analysis of 3-week-old offspring from these intercrosses failed to identify any Mrg15 homozygous mutant animals (Fig. 2B and Table 1). Analysis of _Mrg15_−/− embryos at different gestational stages revealed the occurrence of perineonatal lethality (Fig. 2C and Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Mrg15 genotype analysis of embryos and offspring from heterozygous × heterozygous intercrosses

| Stage | No. (%) of genotype | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Heterozygous | Homozygous | |

| E13.5 | 21 (38.9) | 21 (38.9) | 12 (22.2) |

| E14.5 | 28 (26.4) | 56 (52.8) | 22 (20.8) |

| E15.5 + E16.5 + E17.5 + E18.5 | 23 (32.9) | 35 (50.0) | 12 (17.1) |

| 3 wk | 107 (32.4) | 223 (67.6) | 0 (0) |

To confirm that the introduced Mrg15 mutation was null, we isolated MEFs from E13.5 embryos and obtained total RNA and whole-cell lysates at early passage. Northern and Western blot analyses revealed that Mrg15 mRNA and protein were not expressed in _Mrg15_−/− MEFs and that the Mrg15 mRNA and protein in Mrg15 heterozygous cells was half that of the wild type (Fig. 2D and E). We also did not detect any truncated MRG15 products in Mrg15 null or heterozygous cells.

It has been reported by our group and others that MRG15 is present in a complex(es) with hMOF and TIP60, MYST family HAT members (13, 18, 47). Since TIP60 is known to acetylate histones H4 and H3, we determined the total acetylation levels of these histones in MEFs and found that both decreased about twofold in cells derived from null versus wild-type E13.5 embryos, whereas there was no difference in total histone H4 and H3 proteins (Fig. 2F).

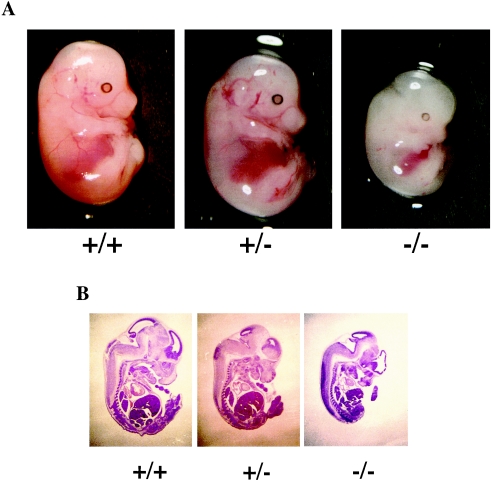

At E14.5, _Mrg15_−/− embryos were obtained in the correct Mendelian ratio (Table 1) and were alive, judging from their beating hearts; however, the body sizes of the null embryos were significantly reduced compared to those of littermate controls (∼74% of wild type; . < 0.001). Additionally, Mrg15 null embryos at E14.5 were pale compared with wild-type and heterozygous embryos, suggesting abnormalities in circulation, vascularization, and/or hematopoiesis (Fig. 3A). Histological analysis of E14.5 embryos indicated that almost all of the major tissues in Mrg15 null embryos were proportionally smaller than those in wild-type embryos (Fig. 3B). A similar analysis of Mrg15 heterozygous and wild-type embryos revealed no such differences (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and null (−/−) Mrg15 embryos. (A) Gross morphology of E14.5 wild-type, Mrg15+/−, and _Mrg15_−/− pups. (B) Hematoxylin-eosin-stained sections of MRG15 embryos at E14.5. Paraffin wax-embedded embryos were sagittally sectioned and stained with hematoxylin-eosin.

Genotyping of newborn pups demonstrated that 6.7% (22 of 330) were Mrg15 null, and these died soon after delivery. The body weights of the null embryos were ∼63% (. < 0.0001) of those of wild-type and heterozygous newborn pups.

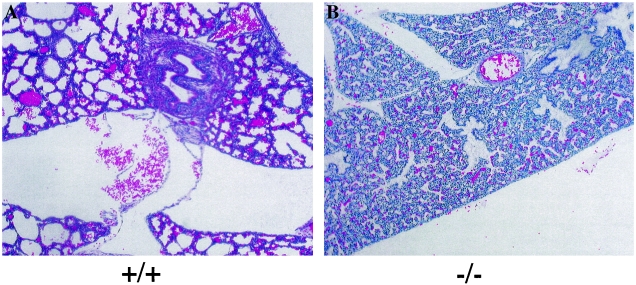

Histological analysis.

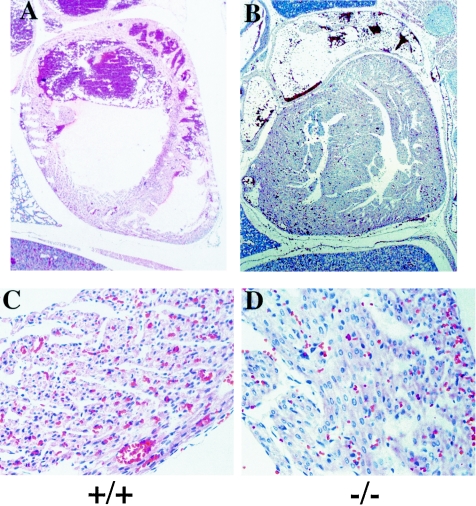

Overall histological examination was performed to determine the potential cause of the death and retarded growth of Mrg15 null embryos and neonates. Examination of the dead neonates revealed that the alveolar space of the _Mrg15_−/− lungs was markedly reduced and most likely failed to inflate at birth (Fig. 4). In general, defects observed in the embryos often became more severe in the neonates. The hearts of _Mrg15_−/− neonates (Fig. 5B and D) exhibited hypertrophy of the ventricles and the atria compared with those of wild-type neonates (Fig. 5A and C). This abnormality of the heart was obvious in E14.5 _Mrg15_−/− embryos, although the phenotype was milder than in neonates (data not shown). In addition, it was evident that the cardiomyocytes were enlarged, and there was myocardial fiber disarray in the null embryos and neonates compared with the wild type. Congestion, particularly in liver, lung, and spleen, and edema under the skin were observed in _Mrg15_−/− neonates but not in the wild type (data not shown). These are phenotypes resulting from abnormalities in the placenta that have been observed in other null mice (1, 25, 53). We therefore examined the placentas of MRG15 null embryos for abnormalities and observed none (data not shown). The skin from Mrg15 null embryos and neonates was thinner and less keratinized than that of control littermates (data not shown), and the cell number and BrdU labeling in the basal cell layer were decreased (see below).

FIG. 4.

Histological analysis of lungs from neonates. Hematoxylin-eosin-stained histological sections of lungs from (A) wild type and (B) _Mrg15_−/−. (Magnification, ×100.)

FIG. 5.

Histological analysis of hearts from neonates. Hematoxylin-eosin-stained histological sections of hearts from wild-type (+/+) (A [magnification, ×40] and C [magnification, ×400]) and _Mrg15_−/− (B [magnification, ×40] and D [magnification, ×400]) neonates. Samples were sectioned sagittally, and the sections show the right ventricle and right atrium of the heart (A and B).

Growth analysis of _Mrg15_−/− embryonic tissues and cells. (i) Immunostaining for apoptosis and cell cycle.

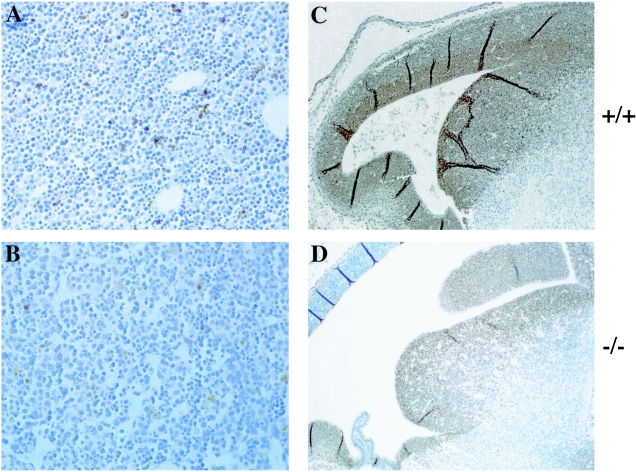

An anti-single stranded DNA antibody was used for detection of apoptotic cells in embryos (21, 49, 60), and no difference in the number of apoptotic cells in null versus wild-type embryos was observed (Fig. 6A and B; liver is the tissue shown). Thus, the apoptotic program was not abnormally activated in _Mrg15_−/− embryos.

FIG. 6.

Detection of apoptotic and proliferating cells. (A and B) Immunohistochemical detection of apoptotic cells in E14.5 liver from wild-type (A) and _Mrg15_−/− (B) embryos with antibody that recognizes single-stranded DNA (brown). (Magnification, ×400) (C and D) Immunohistochemical staining of E14.5 embryo sections with anti-PCNA antibody (brown). An area of the forebrain demonstrates decreased PCNA staining in null (D) versus wild-type (C) embryos. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. (Magnification, ×100.)

We also analyzed the proliferative status of cells in embryos by PCNA staining and BrdU labeling. The number of PCNA-positive cells in _Mrg15_−/− embryos was somewhat lower than in wild-type embryos (Fig. 6C and D; an area of forebrain is shown), and we estimate a decrease of 20 to 30% depending on the tissue examined. This was confirmed by injection of BrdU into pregnant females and incorporation into embryos. The average percentage of BrdU-positive cells was 46% in null embryos versus 58% in wild-type embryos. This was a small but statistically significant difference as determined by the unpaired . test.

(ii) Analysis of growth of mouse embryonic fibroblasts.

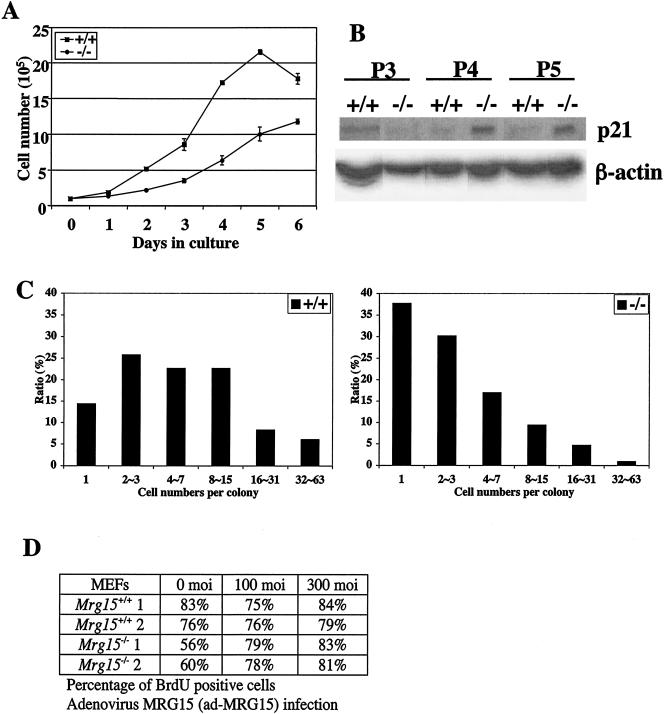

We isolated MEFs from E13.5 embryos and examined their growth properties using daily cell counts and the colony size distribution assay (54). Similar to the observations in embryos, _Mrg15_−/− MEFs showed a significantly lower growth rate than cells from wild-type littermates (Fig. 7A). Enlarged and flattened morphological cells, characteristic of a senescent phenotype (42), were present in cultures at earlier passages of Mrg15 null MEFs than in cultures of wild-type MEFs.

FIG. 7.

Analysis of growth defects in Mrg15 mutant MEFs. (A) Growth kinetics of MEFs. MEFs (105) were plated in 60-mm-diameter dishes and counted every 24 h. This result is representative of three independent experiments. +/+, wild type; −/−, null. (B) p21 expression in MEF cultures. An increased level of p21 is observed in Mrg15−/− MEFs at passage 4 (P4) and P5. (C) Colony size distribution assay of MEFs. MEFs (200 cells) were plated in 60-mm-diameter dishes and incubated for 14 days. The cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde and stained with crystal violet, and the cell number in each colony was determined. These results are representative of three independent experiments. (D) MEFs were infected with adenovirus encoding MRG15, and BrdU incorporation was determined.

To define possible mechanisms for this observation, we determined p21 expression and found that it was at significantly higher levels in Mrg15 null MEFs than in wild-type MEFs at passages 4 and 5 (Fig. 7B). We also determined the expression levels of p53 and p19ARF, which are potential upstream regulators of p21, and found no differences in the expression of these genes in wild-type versus null (data not shown). This suggests that the up-regulation of p21 in MEFs by Mrg15 deficiency may be caused by a p53-independent pathway.

The colony size distribution assay revealed that the number of colonies with >4 Mrg15 null MEFs was lower than for wild-type MEFs (Fig. 7C), and there was a concomitant increase in the number of single-cell colonies, representing cells unable to divide. The colony size distribution assay was developed as a predictor of the number of population doublings a culture would undergo (54), and the results are consistent with the earlier onset of senescence observed in the Mrg15 null cell cultures compared with the wild type. Taken together, the results suggest that a cell growth defect contributes to the runted phenotype of _Mrg15_−/− embryos.

To confirm if this growth defect of _Mrg15_−/− MEFs is a direct effect of the Mrg15 deficiency, we reintroduced MRG15 into MEFs by infection with adenovirus encoding MRG15 and determined the labeling index by BrdU incorporation. There was no effect of ad-MRG15 infection on wild-type MEFs; however, the percentage of BrdU-positive cells increased from 60 to 80% in _Mrg15_−/− MEFs, the same percentage observed in wild-type MEFs (Fig. 7D). These data clearly indicate that the growth defect is a direct consequence of Mrg15 deficiency and not a secondary effect.

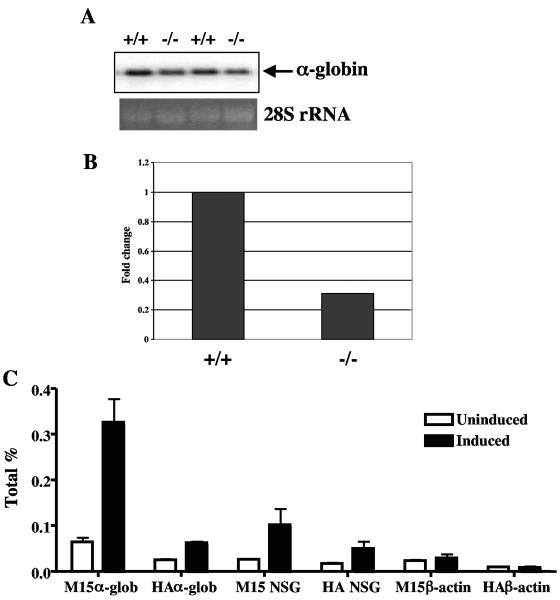

(iii) α-Globin expression by MRG15.

To identify MRG15 target genes, we compared the expression patterns of wild-type and _Mrg15_−/− embryos at E13.5 using membrane-based microarray analysis (unpublished data) and found that α-globin gene expression was significantly reduced in Mrg15 null embryos compared with wild-type embryos. This was predicted by the fact that null embryos were always paler than wild-type and heterozygous embryos. Northern blot and real-time PCR analyses confirmed that α-globin gene expression in _Mrg15_−/− embryos at E13.5 was two to three times lower than that in wild-type embryos (Fig. 8A and B). Additionally, preliminary analyses of peripheral blood specimens from embryos indicated many abnormalities in red and white blood cell morphology in null versus wild-type embryos (R. Robetorye, K. Taminaga, and O. M. Pereira-Smith, unpublished results).

FIG. 8.

Expression of α-globin by MRG15. (A) Northern blot analysis of α-globin expression in E13.5 wild-type (+/+) and _Mrg15_−/− embryos. The lower blot shows 28S rRNA stained with ethidium bromide as a loading control. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of α-globin expression in E13.5 wild-type and _Mrg15_−/− embryos. These data were normalized to β-actin. (C) ChIP assay of the α-globin promoter in MEL cells under uninduced (open column) and induced (16 h; filled column) conditions. The data are derived from quantitative real-time PCR analysis of the α-globin promoter (α-glob), the exonic region of a neuron-specific gene 2 (NSG), and the β-actin promoter. ChIP was performed using either anti-MRG15 (M15) or anti-HA (HA) control antibody. The error bars indicate standard errors of the mean for immunoprecipitations performed in triplicate.

We then used ChIP to confirm that MRG15 was directly involved in regulation of the α-globin promoter. MEL cells (BB88), in which expression of the α- and β-globin genes is controlled by a differentiation program induced by the addition of DMSO (39), were analyzed before and after induction. We selected the promoter area of the α1-globin gene that has the GATA binding site for amplification in this assay. MRG15 protein was recruited to the α-globin promoter at 16 h postinduction at significant levels (Fig. 8C). The acetylation levels of histone H3 and H4 in this region were increased to similar levels at this time point (data not shown) (4). α-Globin mRNA was first detected 24 h after the addition of DMSO, consistent with our hypothesis that MRG15-regulated chromatin-remodeling activity occurs prior to transcriptional activation of this promoter. We also amplified the exonic region of a neuron-specific gene 2 and the β-actin promoter as negative controls and observed no significant differences in induced versus uninduced cells.

DISCUSSION

Inactivation of the Mrg15 gene in mice has demonstrated that it has an essential role in embryogenesis, most likely through regulation of cell growth and differentiation. _Mrg15_−/− embryos display growth retardation and delayed development of many organs and tissues, which is reflected in the proliferative behavior of MEF cultures. MRG15 is involved in chromatin remodeling, and we have shown here that the protein is recruited to the α-globin promoter and correlates with increased histone acetylation around the α-globin promoter and increased expression of the α-globin gene. This could explain the paler appearance of Mrg15 null embryos.

MRG15 is evolutionarily conserved in organisms from yeast to human and is expressed ubiquitously in all tissues (7, 8, 56). It encodes a chromodomain that is very similar to the msl3 chromodomain in Drosophila, which is involved in dosage compensation and causes an increase in transcription along the entire X chromosome of male flies (23). This suggests that MRG15 has the potential to be involved in global transcriptional control. Very similar MRG15-containing complexes exist in yeast and mammalian cells and are thought to be involved in transcriptional control through chromatin remodeling.

The MRG15 homologue in budding yeast, Eaf3p, has been found to be a component of the NuA4 HAT complex (19), and a similar complex has been reported in human cells (13, 17, 18). The Eaf3p null mutant is nonlethal, and the only phenotype is a decrease in the expression of a small number of target genes (19, 52). It is now proposed that Eaf3p is required for maintaining the normal pattern of global H3 and H4 acetylation (10, 31, 33) because of the global histone acetylation pattern changes observed in the Eaf3p deletion mutant (52), although the physiological impact of this in Saccharomyces cerevisiae remains unknown. In contrast, deletion of Alp13, which is the MRG15 homologue in fission yeast (50) and a component of the Clr6 histone deacetylase complex (24, 45), results in loss of viability and increased sensitivity to DNA damage-inducing agents. The Alpl3 mutant also exhibits impaired condensation and resolution of chromosomes during mitosis. The reasons for the differences in the phenotypes in budding versus fission yeast are not clear, but they may be due to differences in cofactors in the cells and thus in the outcome of inactivation of the MRG15 orthologs. The results suggest that Alp13 and other components of the Clr6 complex are involved in the maintenance of genomic integrity (24, 45). If this function is conserved in mammals, we might expect that cancer incidence will be higher in heterozygous MRG15 versus wild-type mice.

MRG-1, the MRG15 homologue in Caenorhabditis elegans, is essential for mitotic proliferation of primordial germ cells during postembryonic development, and RNA interference knockdown of mrg-1 expression results in sterility in 100% of the injected worms (22; A. Olgun, T. Aleksenko, O. M. Pereira-Smith, and D. K. Vassilatis, in press). A small percentage exhibit body wall defects, vulval protrusion, and posterior developmental defects that cause a blunt and shortened tail (Olgun et al., in press). Interestingly, as one analyzes more complex organisms, the Mrg15 null phenotype becomes more severe.

A loss-of-function mutation generated by a P element insertion into the Drosophila Mrg15 allele (dMrg15) results in recessive lethality (FlyBase Report [http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu]). Although we do not know the precise mechanism and phenotype for lethality of this mutant, it is possible that dMrg15 is important for cell growth control during embryo development, similar to the Mrg15 null phenotype in mice. Recently, it has been shown that Drosophila dMrg15 is one of the components of the dTip60 complex, similar to what has been found in yeast and human cells, and that it is essential for DNA repair of double-strand breaks by γ-irradiation (34).

TRRAP (for transactivation-transformation domain-associated protein) is a component of HAT complexes, such as PCAF (59), GCN5 (44), and TIP60 (27). A null mutation of Trrap in mice results in peri-implantation lethality due to a blocked proliferation of blastocysts (26). _Trrap_-deficient cells exhibit chromosome missegregation, mitotic exit failure, and a compromised mitotic checkpoint. These defects are caused by transcriptional dysregulation of the mitotic checkpoint proteins Mad1 and Mad2 (38), since TRRAP recruits HAT activities, including TIP60 and PCAF, to the promoters of these genes. Consistent with this is the fact that acetylation of histone H4 and H3 at these promoters is decreased in _Trrap_-deficient cells. The phenotypes of Mrg15, Gcn5, and Pcaf deficiencies (61, 62) are milder than those of Trrap deficiency. This may be due to the fact that TRRAP is shared by different HAT complexes and loss of Trrap expression results in various overlapping phenotypes that are the consequence of decreased activity of multiple HATs.

_Mrg15_−/− MEFs exhibit impaired proliferation in culture, and the p21 protein is expressed at higher levels in early-passage Mrg15 null MEFs than in the wild type. Early-passage Mrg15 null MEFs also exhibit enlarged and flattened morphology compared with wild-type cells and enter the senescent state more rapidly. The molecular mechanism(s) that results in this growth defect and the increase in p21 expression in Mrg15 null MEFs, with no change in protein levels of p53, requires further investigation. However, it has been reported that the human HAT TIP60 and the budding yeast homologue, Esa1, are involved in DNA damage response (6, 9, 18, 27). If MRG15 is a canonical subunit in complexes involving TIP60 and essential for their function(s), it is possible that this p21 up-regulation and cell proliferation defect may be triggered by increasing genetic instability in _Mrg15_−/− MEFs due to the loss of some TIP60 functions rather than induction by p53. Furthermore, the reduced growth may cause the small-size phenotype and tissue abnormalities observed during development in Mrg15 null embryos.

During development, many factors are involved in organogenesis, and their expression is tightly controlled in a spatiotemporal manner. Control of the α- and β-globin gene loci has been under analysis for many years, and intriguing models for the control of gene expression have been proposed (14, 28, 48). At E11.5 of mouse gestation, the main site of erythropoiesis changes from the embryonic yolk sac (primitive erythropoiesis) to the fetal liver (definitive erythropoiesis) (57). This change in site is coincident with a change from primitive to definitive gene expression in both the α- and β-globin gene clusters, leading to predominant expression of α1 and α2 and βmaj and βmin. At the α-globin locus, acetylation of histones H3 and H4 in ES and nonerythroid cells is maintained at low levels (4), and these are dramatically increased during hemopoietic lineage commitment and differentiation. In the MEL cell differentiation model, although some fraction of H3 and H4 is already acetylated at the α-globin locus prior to induction of globin gene expression, possibly reflecting a primed condition, there is an increase just prior to α-globin gene induction (4) (data not shown). We have found that recruitment of MRG15 protein to the α-globin locus precedes an increase in acetylation. Therefore, one possibility is that MRG15 recruits a HAT(s) to the α-globin locus and thereby controls α-globin expression levels.

We have demonstrated that MRG15 is present in multiple complexes in human cells (13, 18, 47) and that it can act as an activator of the B-myb promoter (37). Both the chromodomain and the leucine zipper region of the protein are required for this activity (47). Thus, it is possible that MRG15 acts through chromatin remodeling, as well as directly at promoters, to regulate the transcription of target genes. The results with the null mice support the hypothesis that MRG15 affects cell proliferation in many tissues and that it is required as a positive regulator for growth during mouse embryogenesis. Comparative studies using null versus wild-type embryos, MEFs, or other cell types should allow us to identify additional endogenous target genes. This will aid in the identification of other potential functions of MRG15 in the maintenance of genomic integrity, immortalization, and tumor formation.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of Ryan Robetorye, Peter J. Hornsby, and Qin Huang in photographing the histology figures. We also thank Lei Chen for injection of ES cells into blastocysts, Simona Varani for help with the ES cell strategies, Julio Agno for maintaining mice, Kevin G. Becker and Diane Teichberg for microarray analysis, Johanna Echigo for maintaining mice and microarray analysis, Meihua Song for purification of antibodies and real-time PCR analysis, and Emiko Tominaga for MEF culture.

This work was supported by NIH grants P01AG2752 (J.R.S. and O.M.P.-S.) and CD60651 (to M.M.M.), the Ellison Medical Foundation (O.M.P.-S.), the American Federation for Aging Research (K.T. and J.G.J.), and DOD grant for Breast Cancer Research DAMD 17-03-1-0324 (J.G.J.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, R. H., A. Porras, G. Alonso, M. Jones, K. Vintersten, S. Panelli, A. Valladares, L. Perez, R. Klein, and A. R. Nebreda. 2000. Essential role of p38α MAP kinase in placental but not embryonic cardiovascular development. Mol. Cell 6**:**109-116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhtar, A., D. Zink, and P. B. Becker. 2000. Chromodomains are protein-RNA interaction modules. Nature 407**:**405-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allard, S., R. T. Utley, J. Savard, A. Clarke, P. Grant, C. J. Brandl, L. Pillus, J. L. Workman, and J. Cote. 1999. NuA4, an essential transcription adaptor/histone H4 acetyltransferase complex containing Esa1p and ATM-related cofactor Tra1p. EMBO J. 18**:**5108-5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anguita, E., J. Hughes, C. Heyworth, G. A. Blobel, W. G. Wood, and D. R. Higgs. 2004. Globin gene activation during haemopoiesis is driven by protein complexes nucleated by GATA-1 and GATA-2. EMBO J. 23**:**2841-2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bannister, A. J., P. Zegerman, J. F. Partridge, E. A. Miska, J. O. Thomas, R. C. Allshire, and T. Kouzarides. 2001. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by HP1 chromo domain. Nature 410**:**120-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berns, K., E. M. Hijmans, J. Mullenders, T. R. Brummelkamp, A. Velds, M. Heimerikx, R. M. Kerkhoven, M. Madiredjo, W. Nijkamp, B. Weigelt, R. Agami, W. Ge, G. Cavet, P. S. Linsley, R. L. Beijersbergen, and R. Bernards. 2004. A large-scale RNAi screen in human cells identifies new components of the p53 pathway. Nature 428**:**431-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertram, M. J., N. G. Berube, X. Hang-Swanson, Q. Ran, J. K. Leung, S. Bryce, K. Spurgers, R. J. Bick, A. Baldini, Y. Ning, L. J. Clark, E. K. Parkinson, J. C. Barrett, J. R. Smith, and O. M. Pereira-Smith. 1999. Identification of a gene that reverses the immortal phenotype of a subset of cells and is a member of a novel family of transcription factor-like genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19**:**1479-1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertram, M. J., and O. M. Pereira-Smith. 2001. Conservation of the MORF4 related gene family: identification of a new chromo domain subfamily and novel protein motif. Gene 266**:**111-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bird, A. W., D. Y. Yu, M. G. Pray-Grant, Q. Qiu, K. E. Harmon, P. C. Megee, P. A. Grant, M. M. Smith, and M. F. Christman. 2002. Acetylation of histone H4 by Esa1 is required for DNA double-strand break repair. Nature 419**:**411-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boudreault, A. A., D. Cronier, W. Selleck, N. Lacoste, R. T. Utley, S. Allard, J. Savard, W. S. Lane, S. Tan, and J. Cote. 2003. Yeast enhancer of polycomb defines global Esa1-dependent acetylation of chromatin. Genes Dev. 17**:**1415-1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brehm, A., E. A. Miska, D. J. McCance, J. L. Reid, A. J. Bannister, and T. Kouzarides. 1998. Retinoblastoma protein recruits histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nature 391**:**597-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brehm, A., K. R. Tufteland, R. Aasland, and P. B. Becker. 2004. The many colours of chromodomain. Bioessays 26**:**133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai, Y., J. Jin, C. Tomomori-Sato, S. Sato, I. Sorokina, T. J. Parmely, R. C. Conaway, and J. W. Conaway. 2003. Identification of new subunits of the multiprotein mammalian TRRAP/TIP60-containing histone acetyltransferase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 278**:**42733-42736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cantor, A. B., and S. H. Orkin. 2002. Transcriptional regulation of erythropoiesis: an affair involving multiple partners. Oncogene 21**:**3368-3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavalli, G., and R. Paro. 1998. Chromo-domain proteins: linking chromatin structure to epigenetic regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 10**:**354-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheung, P., K. G. Tanner, W. L. Cheung, P. Sassone-Corsi, J. M. Denu, and C. D. Allis. 2000. Synergistic coupling of histone H3 phosphorylation and acetylation in response to epidermal growth factor stimulation. Mol. Cell. 5**:**905-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doyon, Y., and J. Cote. 2004. The highly conserved and multifunctional NuA4 HAT complex. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14**:**147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doyon, Y., W. Selleck, W. S. Lane, S. Tan, and J. Cote. 2004. Structural and functional conservation of the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complex from yeast to humans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24**:**1884-1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisen, A., R. T. Utley, A. Nourani, S. Allard, P. Schmidt, W. S. Lane, J. C. Lucchesi, and J. Cote. 2001. The yeast NuA4 and Drosophila MSL complexes contain homologous subunits important for transcription regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 276**:**3484-3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank, S. R., M. Schroeder, P. Fernandez, S. Taubert, and B. Amati. 2001. Binding of c-Myc to chromatin mediates mitogen-induced acetylation of histone H4 and gene activation. Genes Dev. 15**:**2069-2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frankfurt, O. S., J. A. Robb, E. V. Sugarbaker, and L. Villa. 1996. Monoclonal antibody to single-stranded DNA is a specific and sensitive cellular marker of apoptosis. Exp. Cell Res. 226**:**387-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujita, M., T. Takasaki, N. Nakajima, T. Kawano, Y. Shimura, and H. Sakamoto. 2002. MRG-1, a mortality factor-related chromodomain protein, is required maternally for primordial germ cells to initiate mitotic proliferation in C. elegans. Mech. Dev. 114**:**61-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorman, M., A. Franke, and B. S. Baker. 1995. Molecular characterization of the male-specific lethal-3 gene and investigations of the regulation of dosage compensation in Drosophila. Development 122**:**463-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grewal, S. I. S., M. J. Bonaduce, and A. J. Klar. 1998. Histone deacetylase homologs regulate epigenetic inheritance of transcriptional silencing and chromosome segregation in fission yeast. Genetics 150**:**563-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemberger, M., and J. C. Cross. 2001. Genes governing placental development. Trends Endocrin. Metab. 12**:**162-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herceg, Z., W. Hulla, D. Gell, C. Cuenin, M. Lleonart, S. Jackson, and Z. Q. Wang. 2001. Disruption of Trrap causes early embryonic lethality and defects in cell cycle progression. Nat. Genet. 29**:**206-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikura, T., V. V. Ogryzko, M. Grigoriev, R. Groisman, J. Wang, M. Horikoshi, R. Scully, J. Qin, and Y. Nakatani. 2000. Involvement of the TIP60 histone acetylase complex in DNA repair and apoptosis. Cell 102**:**463-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isogai, Y., and R. Tjian. 2003. Targeting genes and transcription factors to segregated nuclear compartments. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15**:**296-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson, J. G., P. St. Clair, M. X. Sliwkowski, and M. G. Brattain. 2004. Blockade of epidermal growth factor- or heregulin-dependent ErbB2 activation with the anti-ErbB2 monoclonal antibody 2C4 has divergent downstream signaling and growth effects. Cancer Res. 64**:**2601-2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones, D. O., I. G. Cowell, and P. B. Singh. 2000. Mammalian chromodomain proteins: their role in genome organisation and expression. Bioessays 22**:**124-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katan-Khaykovich, Y., and K. Struhl. 2002. Dynamics of global histone acetylation and deacetylation in vivo: rapid restoration of normal histone acetylation status upon removal of activators and repressors. Genes Dev. 16**:**743-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koonin, E. V., S. Zhou, and J. C. Lucchesi. 1995. The chromo superfamily: new members, duplication of the chromodomain and possible role in delivering transcription regulators to chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 23**:**4229-4233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurdistani, S. K., and M. Grunstein. 2003. Histone acetylation and deacetylation in yeast. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4**:**276-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kusch, T., L. Florens, W. H. MacDonald, S. K. Swanson, R. L. Glaser, J. R. R. Yates, S. M. Abmayr, M. P. Washburn, and J. L. Workman. 2004. Acetylation by Tip60 is required for selective histone variant exchange at DNA lesions. Science 306**:**2084-2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lachner, M., D. O'Carroll, S. Rea, K. Mechtler, and T. Jenuwein. 2001. Methlation of histone H3 lysine 9 creates a binding site for HP1 proteins. Nature 410**:**116-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lam, E. W., and R. J. Watson. 1993. An E2F-binding site mediates cell-cycle regulated repression of mouse B-myb transcription. EMBO J. 12**:**2705-2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leung, J. K., N. G. Berube, A. Venable, S. Ahmed, N. Timchenko, and O. M. Pereira-Smith. 2001. MRG15 activates the B-myb promoter through formation of a nuclear complex with the retinoblastoma protein and the novel protein PAM14. J. Biol. Chem. 276**:**39171-39178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li, H., C. Cuenin, R. Murr, Z. Q. Wang, and Z. Herceg. 2004. HAT cofactor Trrap regulates the mitotic checkpoint by modulation of Mad1 and Mad2 expression. EMBO J. 23**:**4824-4834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu, S.-J., S. Rowan, M. R. Bani, and Y. Ben-David. 1994. Retroviral integration within the Fli-2 locus results in inactivation of the erythroid transcription factor NF-E2 in Friend erythroleukemias: evidence that NF-E2 is essential for globin expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91**:**8398-8402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo, R. X., A. A. Postigo, and D. C. Dean. 1998. Rb interacts with histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Cell 92**:**463-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marin, I., and B. S. Baker. 2000. Origin and evolution of the regulatory gene male-specific lethal-3. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17**:**1240-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathon, N. F., and A. C. Lloyd. 2001. Cell senescence and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 1**:**203-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matzuk, M. M., M. J. Finegold, J. J. Su, A. J. W. Hsueh, and A. Bradley. 1992. Alpha-inhibin is a tumor suppressor gene with gonadal specificity in mice. Nature 360**:**313-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McMahon, S. B., M. A. Wood, and M. D. Cole. 2000. The essential cofactor TRRAP recruits the histone acetyltransferase hGCN5 to c-Myc. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20**:**556-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakayama, J., G. Xiao, K. Noma, A. Malikzay, P. Bjerling, K. Ekwall, R. Kobayashi, and S. I. S. Grewal. 2003. Alp13, an MRG family protein, is a component of fission yeast Clr6 histone deacetylase required for genomic integrity. EMBO J. 22**:**2776-2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neal, K. C., A. Pannuti, E. R. Smith, and J. C. Lucchesi. 2000. A new human member of the MYST family of histone acetyl transferases with high sequence similarity to Drosophila MOF. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 1490**:**170-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pardo, P. S., J. K. Leung, J. C. Lucchesi, and O. M. Pereira-Smith. 2002. MRG15 a novel chromodomain protein is present in two distinct multiprotein complexes involved in transcriptional activation. J. Biol. Chem. 277**:**50860-50866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patrinos, G. P., M. de Krom, E. de Boer, A. Langeveld, A. M. Imam, J. Strouboulis, W. de Laat, and F. G. Grosveld. 2004. Multiple interactions between regulatory regions are required to stabilize an active chromatin hub. Genes Dev. 18**:**1495-1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prochazkova, J., D. Kylarova, P. Vranka, and V. Lichnovsky. 2003. Comparative study of apoptosis-detecting techniques: TUNEL, apostain, and lamin B. BioTechniques 35**:**528-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Radeliffe, P., D. Hirata, D. Childs, L. Vardy, and T. Toda. 1998. Identification of novel temperature-sensitive lethal alleles in essential β-tubulin and nonessential α2-tubulin genes as fission yeast polarity mutants. Mol. Biol. Cell. 9**:**1757-1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rayman, J. B., Y. Takahashi, V. B. Indjeian, J.-H. Dannenberg, S. Catchpole, R. J. Watson, H. te Riele, and B. D. Dynlacht. 2002. E2F mediates cell cycle-dependent transcriptional repression in vivo by recruitment of an HDAC1/mSin3B corepressor complex. Genes Dev. 16**:**933-947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reid, J. L., Z. Moqtaderi, and K. Struhl. 2004. Eaf3 regulates the global pattern of histone acetylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24**:**757-764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rossant, J., and J. C. Cross. 2001. Placental development: lessons from mouse mutants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2**:**538-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith, J. R., O. M. Pereira-Smith, and E. L. Schneider. 1978. Colony size distributions as a measure of in vivo and in vitro aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75**:**1353-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taplick, J., V. Kurtev, G. Lagger, and C. Seiser. 1998. Histone H4 acetylation during interleukin-2 stimulation of mouse T cells. FEBS Lett. 436**:**349-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tominaga, K., and O. M. Pereira-Smith. 2002. The genomic organization, promoter position and expression profile of the mouse MRG15 gene. Gene 294**:**215-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trimborn, T., J. Gribnau, F. Grosveld, and P. Fraser. 1999. Mechanisms of developmental control of transcription in the murine α- and β-globin loci. Genes Dev. 13**:**112-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tullio, A. N., D. Accili, V. J. Ferrans, Z.-X. Yu, K. Takeda, A. Grinberg, H. Westphal, Y. A. Preston, and R. S. Adelstein. 1997. Nonmuscle myosin II-B is required for normal development of the mouse heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94**:**12407-12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vassilev, A., J. Yamauchi, T. Kotani, C. Prives, M. L. Avantaggiati, J. Qin, and Y. Nakatani. 1998. The 400 kDa subunit of the PCAF histone acetylase complex belongs to the ATM superfamily. Mol. Cell 2**:**869-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Watanabe, I., M. Toyoda, J. Okuda, T. Tenjo, K. Tanaka, T. Yamamoto, H. Kawasaki, T. Sugiyama, Y. Kawarada, and N. Tanigawa. 1999. Detection of apoptotic cells in human colorectal cancer by two different in situ methods: antibody against single-stranded DNA and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end-labeling (TUNEL) methods. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 90**:**188-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu, W., D. G. Edmondson, Y. A. Evrard, M. Wakamiya, R. R. Behringer, and S. Y. Roth. 2000. Loss of Gcn5l2 leads to increased apoptosis and mesodermal defects during mouse development. Nat. Genet. 26**:**229-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamauchi, T., J. Yamauchi, T. Kuwata, T. Tamura, T. Yamashita, N. Bae, H. Westphal, K. Ozato, and Y. Nakatani. 2000. Distinct but overlapping roles of histone acetylase PCAF and of the closely related PCAF-B/GCN5 in mouse embryogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97**:**11303-11306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]