Increased expression of cholesterol transporter ABCA1 is highly correlated with severity of dementia in AD hippocampus (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 Mar 8.

Abstract

To gain insight into ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) function and its potential role in AD pathology, we analyzed the expression of the cholesterol transporter ABCA1 in postmortem hippocampus from persons at different stages of dementia and AD associated neuropathology relative to cognitively intact normal donors by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and Western blot. In this study clinical dementia rating (CDR) scores were used as a measure of dementia severity, whereas, Braak neuropathological staging and neuritic plaque density were used as an index of the neuropathological progression of AD. Correlation analysis showed that ABCA1 mRNA expression was significantly elevated at the earliest recognizable stage of dementia compared to persons with intact cognition. ABCA1 mRNA was also positively correlated with Braak neuropathological stages and neuritic plaque density counts. Additionally, ABCA1 mRNA levels showed robust correlation with dementia severity even after controlling for the confounding contribution of accompanying neuropathological parameters to ABCA1 mRNA expression. Western blot analyses showed that the differential expression observed at the transcriptional level is also reflected at the protein level. Thus, our study provides transcriptional and translational evidence that the expression of ABCA1, a key modulator of cholesterol transport across the plasma membrane, is dysregulated in the AD brain and that this dysregulation is associated with increasing severity of AD, whether measured functionally as dementia severity or neuropathologically as increased neuritic plaque and neurofibrillary tangle density.

1. Introduction

Abnormalities in cholesterol metabolism in brain appear as an important element in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk and pathogenesis, as evidenced by genetic, cell-culture, mouse model, and epidemiologic data (Corder et al., 1993; Simons et al., 1998; Fassbender et al., 2001; Refolo et al., 2001; Kivipelto et al., 2001; Shobab et al., 2005; Hutter-Paier et al., 2004; Wolozin et al., 2000; Wahrle et al., 2002). This is not surprising as generation of β-amyloid (Aβ), a hallmark of AD pathophysiology, is a membrane-associated event and cholesterol is an essential membrane component highly enriched in the brain (compared to other tissues). Cholesterol levels regulate membrane fluidity and size and distribution of lipid rafts where enzymes necessary for Aβ production are localized (Wahrle et al., 2002; Puglielli et al., 2003; Stefani and Liguri, 2009; Ehehalt et al., 2003; Bodovitz and Klein, 1996). Consequently, changes in content or distribution of cholesterol in neurons and glia could have a profound impact on Aβ production, dementia and neuropathology.

Peripheral and cerebral cholesterol pools remain largely segregated due to the relative impermeability of the blood brain barrier. Therefore, the brain meets its own cholesterol demand by de novo synthesis. In the adult brain, cholesterol homeostasis is achieved by slow turnover and efficient excretion of excess cholesterol in the form of 24-hydroxycholesterol to the peripheral circulation for eventual excretion by the liver (Dietschy and Turley, 2001;Vance et al., 2005). In the periphery, there are three main pathways for elimination of cholesterol. Cholesterol can be esterified and stored as cholesterol esters (Brown and Goldstein, 1999), it can be oxidized at positions 24, 25, or 27 to form specific oxysterols by the action of enzymes belonging to the cytochrome P-450 family (Russell, 2000), or it can be metabolized via the bile acid pathway following its secretion within lipoprotein complexes, a process termed reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), where ABCA1 plays a pivotal role (Fielding and Fielding, 1995; Yancey et al., 2003). The role of the first two pathways in removal of excess brain cholesterol has been extensively elucidated. However, the contribution of RCT to cerebral cholesterol transport and metabolism is relatively obscure and provided an impetus to explore a connection between ABCA1 and AD.

ABCA1 mediates the rate-limiting step in RCT (Bodzioch et al., 1999; Brooks-Wilson et al., 1999; Repa and Mangelsdorf, 2002). ABCA1 is an integral membrane protein that mediates the efflux of cellular cholesterol and phospholipids to lipid-deficient apolipoproteins, a process critical for HDL synthesis. Mutations in ABCA1 cause Tangier disease, a severe HDL deficiency syndrome characterized by the deposition of sterols in tissue macrophages and defective assembly of cholesterol and phospholipids within apolipoproteins. Interestingly, the ABCA1 gene is highly expressed in putamen, occipital lobe, amygdala, hippocampus, and substantia nigra in the human brain (Langmann et al., 1999). Animal studies suggest that ABCA1 mRNA is localized predominantly (Tachikawa et al., 2005), but not exclusively, to neurons (Kim et al., 2006).

Analysis of results from a large-scale microarray study of postmortem brain specimens obtained from multiple brain regions of elderly patients with varying severity of dementia (Katsel et al., 2009) indicates transcriptional changes in several genes that modulate intracellular cholesterol flux (Akram et al., 2007; Akram et al., 2008). Notably, preliminary analyses of microarray data showed that ABCA1 expression was dysregulated in brain regions at an early stage in the progression of AD. Moreover, analysis of 15 individually assessed brain regions indicated most robust changes in gene expression in AD vulnerable regions such as areas 20, 22 and hippocampus, whereas area 17, a region relatively spared during the course of disease (Kergoat et al., 2002; Lee and Martin, 2004; Hao et al., 2005; Bair, 2005), remained unaffected. To gain more conclusive and detailed insight into ABCA1 function and its potential role in AD we analyzed ABCA1 mRNA expression in the hippocampus of a large series of cases at different stages of dementia and AD associated neuropathology by qPCR. Also, because mRNA and protein levels can diverge significantly through post-transcriptional regulation and intracellular compartmentalization, Western blotting was used to quantify protein levels in the hippocampus of a subset of the postmortem brain specimens used in PCR analyses.

2. Results

3.1. qPCR Analysis of ABCA1 Expression in Hippocampus

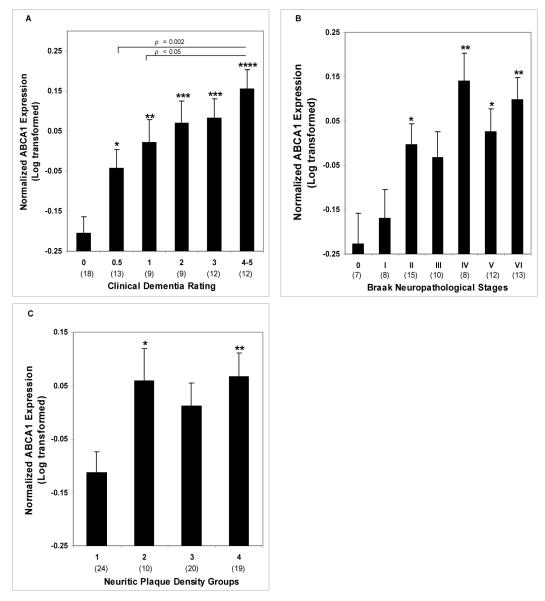

Partial correlations of ABCA1 mRNA expression controlling for age and RIN demonstrated significant associations with CDR (r = 0.569, df = 69, p < 0.0005), Braak score (r = 0.435, df = 69, p < 0.0005) and plaque density (r = 0.335, df = 69, p = 0.004). Even after controlling also for Braak score and plaque density, ABCA1 gene expression was still strongly correlated with CDR (r = 0.415, df = 67, p < 0.0005). In ANCOVAs controlling for age and RIN, when CDR (F5,65 = 7.16, p < 0.0005), Braak score (F6,64 = 3.21, p = 0.008) and plaque density (F3,67 = 3.42, p = 0.022) were used as categorical variables, the associations were similarly evident. The association of ABCA1 gene expression with CDR, controlling also for Braak score and plaque density scales, remained strong (F5,63 = 3.75, p = 0.005). Figure 1 presents the estimated means and SEM from the ANCOVAs. Significant differences in ABCA1 expression were evident when the lowest disease severity groups were compared to any of the more severely affected groups. Significance generally increased with increasing clinical or neuropathological severity. In addition to a strong linear trend (p < 0.0005) and no other significant polynomial trend, ABCA1 levels in subjects with CDR 0.5 (p = 0.002) and CDR 1 (p < 0.05) were significantly different from those with CDR 4 or 5.

Figure 1.

Normalized ABCA1 mRNA expression plotted against CDR scores, Braak neuropathological stages and plaque density groups. A, ANCOVA was used to determine ABCA1 gene expression in different CDR groups. Age and RIN were used as covariates. CDR groups are significantly different relative to control group (F5,67 = 7.16, p < 0.0001). B, ABCA1 gene expression plotted against different Braak neuropathological stages also revealed significant differences between different stages (F6,66 = 3.28, p < 0.01). C, ABCA1 gene expression plotted against plaque density groups revealed significant differences between different groups (F3,69 = 3.42, p < 0.05). Average values ± SEM are shown. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001 and **** = p < 0.0001.

Comparisons of subjects with and without AD showed greater ABCA1 gene expression by the CDR criterion (F1,69 = 24.30, p < 0.0005), by the Braak neuropathological staging (F1, 69 = 17.93, p < 0.0005), and by the neuritic plaque density criterion (F1,69 = 9.20, p = 0.003). For subjects with dementia (i.e. CDR ≥ 0.5), the linear association of CDR with ABCA1 gene expression was significant (r = 0.401, df = 51, p = 0.003) and retained significance even after controlling for Braak neuropathological staging and plaque neuritic density (r = 0.320, df = 49, p = 0.021). However, the associations of ABCA1 gene expression with Braak neuropathological staging and plaque neuritic density were not significant.

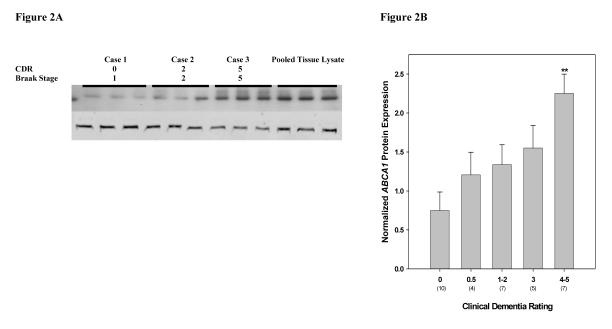

3.2. ABCA1 Protein Expression

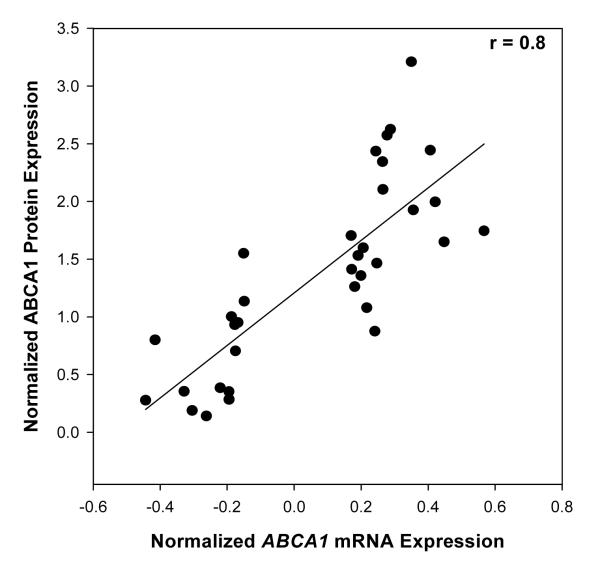

Western blot analysis revealed robust ABCA1 protein expression in the hippocampal tissue homogenates from human postmortem brains (Fig. 2A). ABCA1 protein expression was highly correlated (r = 0. 80, p < 0.0001) with mRNA levels of ABCA1 (Fig. 3). These findings suggest coordinated transcription and translation modulation of ABCA1 during the course of AD.

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of ABCA1 in the hippocampus of cognitively intact controls and subjects with varying severity of dementia and NFT pathology. Representative immunoblot of ABCA1 protein expression is shown. Total tissue homogenates were separated by reducing SDS-PAGE and probed with mouse anti-ABCA1 and mouse anti-VCP antibodies. Second row shows VCP signal detected by Odyssey IR imaging system. The positions of marker proteins are indicated. Tissue lysate from each subject and pooled tissue lysate (last 3 lanes) were loaded in triplicate.

Figure 3.

Association between mRNA levels and protein levels of ABCA1. Increase in ABCA1 mRNA was highly correlated (r = 0.80, p < 0.0001) with protein levels of ABCA1 in a subset of cases used in PCR analysis.

Partial correlations of ABCA1 protein expression controlling for age and PMI were comparable to those of gene expression for CDR (r = 0.580, df = 30, p = 0.001) and for Braak score (r = 0.485, df = 30, p = 0.005) but lower for plaque density (r = 0.194, df = 30, p = 0.288). Similarly in ANCOVAs, CDR (F4,27 = 4.36, p = 0.007) (Figure 2B) and Braak neuropathological stages (F4,27 = 2.96, p = 0.038) were significantly correlated with ABCA1 protein expression. However, the association of ABCA1 protein expression with CDR, controlling also for Braak score and plaque density scales, approached significance (F4,25 = 2.46, p = 0.072).

These results indicate that there is close correspondence between ABCA1 gene and protein expression. Moreover, ABCA1 expression is correlated with the cardinal measures of disease severity, namely cognitive decline and NFT associated pathology.

3. Discussion

These results indicate that ABCA1 gene expression in the hippocampus increases in AD and as a function of increasing AD-associated indices of disease severity. To determine whether ABCA1 expression was upregulated early in the course of cognitive compromise or AD pathogenesis, subjects were grouped based on cognitive function (CDR score) at the time of death, severity of NFT pathology, and neuritic plaque involvement. Correlation analyses indicated that the expression level of the cholesterol transporter ABCA1 increased with increasing disease severity, irrespective of the metric used to assess disease progression. Specifically, alteration in gene expression was strongly correlated with increasing cognitive impairment. Interestingly, the upregulation of ABCA1 with disease severity is not restricted to the analysis of the hippocampus, similar results had been obtained when the superior temporal gyrus (area 22) and inferior temporal gyrus (area 20) were analyzed in preliminary microarray studies (Akram et al., 2007; Akram et al., 2008). On the other hand, area 17, the primary visual cortex - a region less susceptible to AD, did not show early changes in gene expression. Contrary to previously reported discordance between relative mRNA and protein expression pattern in mouse brain (Wellington et al., 2002), we observed highly coordinated upregulation of ABCA1 protein in human hippocampus. However, this study is based on assays at brain tissue level and did not resolve increased ABCA1 gene expression at the cellular level.

CDR, plaque density, and Braak stages represent different facets of the disease: CDR defines a continuum of functional impairment; neuritic plaque density reflects the extent of amyloid pathology; Braak stage reflects the extent of neurofibrillary and tau pathology. However, these parameters are highly interrelated and stratification of subjects based on these variables does not permit analysis of the independent relationship of ABCA1 gene to each of these variables. To gain a better understanding of the independent relationship of each of these clinical and neuropathological variables to the expression of ABCA1 gene, we performed partial correlation analyses where the relationship of ABCA1 to CDR was assessed after controlling for the contribution of NFTs and neuritic plaques. Controlling for the potential contribution of both NFTs and neuritic plaques did not affect the strong association between ABCA1 and cognitive decline.

ABCA1 is a translocase that uses its ATPase activity to move cholesterol from the cytofacial to exofacial leaflet of the plasma membrane (Zarubica et al., 2007). It plays a critical role in peripheral cholesterol transport by controlling the formation of high-density lipoprotein (HDL). ABCA1 is also capable of reorganizing cholesterol-rich lipid rafts on the plasma membrane such that more non-raft microdomains are formed upon ABCA1 expression. Importantly, these non-raft domains facilitate apolipoprotein association with cells and, consequently, cholesterol and phospholipid acquisition by apolipoproteins to form nascent HDL particles. This process known as reverse cholesterol transport ultimately leads to elimination of excess cholesterol from the body. In other words, ABCA1 controls physiologic properties of membrane by modulating both transversal and lateral lipid distribution at the plasma membrane and primes the cell surface for apolipoprotein-mediated efflux of cholesterol (Landry and Xavier, 2006). Because membrane cholesterol modulates the generation of Aβ derived from the sequential proteolytic cleavage of the transmembrane amyloid precursor protein (APP) by the β- and γ-secretases respectively (Kojro et al., 2001; Abad-Rodriguez et al., 2004; Crameri et al., 2006), membrane cholesterol dyshomeostasis can potentially contribute to the amyloidogenic processing of APP. It has been shown in hippocampal neuronal membranes of both humans and transgenic mice expressing physiologically and pathologically relevant levels of APP and β-secretase, that APP is largely excluded from the less fluid, cholesterol-rich detergent-resistant microdomains (DRMs) (Abad-Rodriguez et al., 2004). However, with moderate reduction of membrane cholesterol, β-secretase is displaced from DRMs to non-raft domains and cofractionates with APP in the more fluid medium, which offers the optimal conditions for enzyme-substrate interaction. Similarly, several studies suggest that cholesterol loss in neuronal membranes enhances amyloid peptide generation (Ledesma and Dotti, 2005; Arispe and Doh, 2002). These results are all consistent with ABCA1 facilitation of cholesterol efflux. However, in vitro studies investigating a direct role of ABCA1 in the regulation of proteolytic cleavage of APP and Aβ deposition have reported variable and contradictory observations. Consistent with the current observations, induction of ABCA1 in the Neuro2a neuroblastoma cell line using oxysterol or synthetic ligands has been shown to increase Aβ secretion (Fukumoto et al., 2002). In contrast, liver X receptor (LXR)/retinoic acid receptor (RXR)-induced ABCA1 expression inhibited Aβ secretion from Neuro2a cell, rat primary cortical neurons, and from a CHO cell line stably expressing the amyloidogenic Swedish variant of human APP695 (Koldamova et al., 2003; Sun et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2007). The reasons for the discrepancies among the studies is likely attributable to differences between the expression of APP under physiologic conditions vs. its expression in mutant cells, and possibly to differences in the extent to which membrane cholesterol transport was modified under the different in vitro conditions.

Interestingly, in vivo studies investigating potential association between genetic loss of ABCA1 and Aβ production and plaque deposition in transgenic mice, found no consistent evidence for a modified rate of APP processing or Aβ deposition (Hirsch-Reinshagen et al., 2005; Wahrle et al., 2005; Burns et al., 2006; Hirsch-Reinshagen et al., 2007). Despite these inconsistencies, differences in transgene expressed and the mutation it carried, the promoter used and the genetic background of the animals, the overall conclusion that can be reached from these studies is that in the absence of ABCA1, significant reductions in brain total ApoE concentration or altered ApoE solubility was observed in all four animal models. Coming from the opposite direction, selective overexpression of ABCA1 in amyloidogenic transgenic PDAPP mice was recently shown to be associated with significantly less Aβ deposition and increased lipidation of ApoE-containing particles. Based on the lack of effect of ABCA1 on APP processing and yet pronounced effect on ApoE levels and lipidation, it was suggested that lipidated ApoE may somehow promote Aβ clearance. This is substantiated by strong association between ApoE and Aβ in vivo (Naslund et al., 1994) and in vitro binding and internalization of soluble Aβ by human ApoE expressing neurons. In light of these findings, the upregulated ABCA1 expression observed in our study can be interpreted as an attempt to clear Aβ presumably through the modulation of membrane cholesterol efflux and increased ApoE lipidation. Since most robust effects on ApoE lipidation were observed in mice with as much as 6-14 fold increase in ABCA1 expression, we cannot rule out the possibility of driving ABCA1 expression further (or to a much higher levels in brain) may increase ApoE levels of lipidation.

Although association of ABCA1 overexpression with NFT pathology has not been evaluated directly in animal studies, however, cholesterol levels in the brain are intimately associated with degree of tau phosphorylation (Koudinov and Koudinova, 2001; Fan et al., 2001). These and other observations (Sawamura et al., 2003; Suzuk et al., 1995; Blanchette-Mackie et al., 1988; Vanier et al., 1998; Distl et al., 2003; Naslund et al., 1994) support the hypothesis that _ABCA1_-mediated cholesterol translocation on the cellular membrane and subsequent efflux can potentially influence amyloidogenesis and tau processing. Significant associations between increased expression of ABCA1 and neuropathological indices of AD observed in our data also strongly support an association between ABCA1 and AD.

It is important to emphasize that ABCA1 not only affects the lateral lipid distribution, thereby priming the cellular efflux of cholesterol, but also disrupts membrane rafts, and as such modulates the lipid architecture at the membrane and its physiochemical properties (Landry et al., 2006; Zarubica et al., 2009). Indeed, expression of ABCA1 has been shown to reduce the activity of the transferrin receptor (Goodwin et al., 2005), and several raft-associated cytokine receptors (Maldonado et al., 2004; Marchetti et al., 2006), in addition to promoting potentially pathogenic microvesiculation and proinflammatory responses (Combes et al., 2005; Duong et al., 2006). Interestingly, altered lipid compositions with cholesterol decrease and lipid raft alteration have been reported in temporal cortex samples from AD brains (Mason et al., 1992; Molander-Melin et al., 2005). Moreover, biochemical analysis of membranes in hippocampus of human subjects with AD revealed a mild, yet significant, cholesterol reduction and raft disorganization (reflected by the loss of raft-enriched proteins) compared to age-matched controls (Ledesma et al., 2003). There is considerable converging evidence that raft disorganization reported in patients with AD is associated with the two hallmarks of AD, the amyloid plaques and NFTs (Ledesma et al., 2003; Tucker et al., 2000; Ledesma et al., 2000). The data presented here based on the direct analysis of the brains of persons with varying severity of AD indicate that ABCA1 levels are abnormally upregulated in AD. Taken together with the previously reported postmortem analyses of AD brains, and polymorphisms in ABCA1 gene with dementia and AD progression (Reynolds et al., 2009; Rodriguez-Rodriguez et al., Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007; Katzov et al., 2004; Wollmer et al., 2003) increased levels of ABCA1 with increasing severity of cognitive impairment and AD neuropathology may underlie the cholesterol dyshomeostasis and lipid raft disorganization previously observed in the AD brain.

In summary, significant associations between upregulated expression of ABCA1 and clinical/neuropathological indices of AD observed in our data support a strong connection between ABCA1 and AD. Our results also corroborate previously reported cholesterol dyshomeostasis observed in patients with AD and support the view that increased levels of ABCA1 with increasing severity of cognitive impairment and AD neuropathology may be associated with increased translocation of cholesterol to the exofacial side of plasma membrane thereby progressively facilitating cholesterol efflux to lipid-poor apolipoproteins particles. Given the static postmortem and homogenate nature of the current study, the notion that the observed AD severity-associated ABCA1 expression increases involve cholesterol translocation must be interpreted as suggestive only. Nonetheless, _ABCA1_-mediated cholesterol efflux and ApoE lipidation have been shown to reduce Aβ deposition in APP transgenic mice, and therefore, this beneficial function of ABCA1 may become overwhelmed by _ABCA1_-mediated disruption of lipid architecture, which in turn is intimately associated with amyloidogenesis and tau processing.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1 Study Cohort

The study utilized postmortem brain specimens from 73 subjects selected to include cases with varying severity of dementia and AD neuropathology and cognitively intact persons with no discernable neuropathology or psychopathology. Cases were selected from a pool of over 600 donors to meet the following criteria: postmortem delay of less than 24 hours, no perimortem coma longer than 6 hours, no evidence of seizures in the 3 months preceding death, brain tissue pH of 6.2 or greater, either no discernable neuropathology or only those neuropathological lesions associated with AD alone (e.g., exclusion of cases with vascular lesions, Lewy body inclusions, normal pressure hydrocephalus, etc). Controls were derived from persons who, on extensive medical record review and/or neuropsychological examination and caregiver interview, evidenced no neurological or neuropsychiatric diseases, died of natural causes (myocardial infarction, various non-brain non-hepatic cancers, and congestive heart failure) and did not show evidence of any discernable neuropathology (Purohit et al., 1998). None of the subjects had a history of licit or illicit drug abuse (tobacco use excepted) and died of natural causes. All diagnostic and cognitive assessment procedures were approved by the Mount Sinai Medical Center (New York, NY)/J. J. Peters Veterans Administration Medical Center (Bronx, NY) Institutional Review Boards, and postmortem consent for autopsy and research use of tissue was obtained from the next of kin or a legally authorized official.

4.1.1 Classification of Subjects into Dementia Severity Groups

In order to perform post-assay analyses based on a clinical index of disease severity, the subjects were classified with respect to the cognitive dementia rating (CDR) score at the time of death (Hughes et al., 1982; Burke et al., 1988; Morris, 1993) (Table 1). The assessments, on which these classifications were based, were performed blind to clinical or neuropathological disease diagnosis.

Table 1.

Group classifications for gene and protein expression analyses.

| Gene Expression Analysisa | Protein Expression Analysisb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDR Groups | Dementia Severity | Subject Number | CDR Groups | Dementia Severity | Subject Number |

| 0 | No dementia (0) | 18 | 0 | No dementia (0) | 10 |

| 1 | Questionable dementia (0.5) | 13 | 1 | Questionable dementia (0.5) | 4 |

| 2 | Mild dementia (1) | 9 | 2 | Mild/moderate dementia (1-2) | 7 |

| 3 | Moderate dementia (2) | 9 | 3 | Severe dementia (3) | 5 |

| 4 | Severe dementia (3) | 12 | 4 | Very severe/terminal dementia (4-5) | 7 |

| 5 | Very severe/terminal dementia (4-5) | 12 |

| Braak Groups | Braak stages | Braak Groups | Braak stages | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | None (0) | 7 | 0 | None (0) | 5 |

| 1 | Mild transentorhinal (I) | 8 | 1 | Mild transentorhinal (I) | 6 |

| 2 | Severe transentorhinal (II) | 15 | 2 | Severe transentorhinal (II) | 9 |

| 3 | Limbic (III) | 10 | 3-4 | Limbic / Hippocampal CA1(III-IV) | 6 |

| 4 | Limbic/Hippocampal CA1 (IV) | 8 | 5-6 | Isocortical / Primary sensory areas (V-VI) | 8 |

| 5 | Isocortical (V) | 12 | |||

| 6 | Isocortical/ Primary sensory areas (VI) | 13 |

| Plaque Density Groups | Plaques (number/mm2) | Plaque Density Groups | Plaques (number/mm2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 24 | 1 | 0 | 15 |

| 2 | 1-5 | 10 | 2 | 1-5 | 5 |

| 3 | 6-10 | 20 | 3 | 6 and more | 14 |

| 4 | 11 and more | 19 |

Postmortem intervals (PMI) (Johnson et al., 1986;Barton et al., 1993) and tissue pH (a proxy measure for agonal state) (Vawter et al., 2006; Lipska et al., 2006) are important issues for consistency and reproducibility of quantitative gene and protein expression studies. Brain samples were obtained from cases with a median PMI of 6.5 hrs and pH of 6.58. Table 2 describes the sample size, sex, age at the time of death, pH and PMI of the study cohort when grouped on the basis of CDR. CDR groups differed significantly for age (F5,67 = 3.3, p = 0.01) and for PMI (F5,67 = 3.2, p = 0.01). The influence of age and PMI was therefore factored out statistically buy including age and PMI as covariates in the analyses of variance (ANCOVA) (see below).

Table 2.

Demographic details of study cohort stratified with respect to CDR (Clinical Dementia Rating) groups.

| Characteristics | CDR 0 | CDR 0.5 | CDR 1 | CDR 2 | CDR 3 | CDR 4–5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total subjects* | 18 | 13 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 12 |

| Gender (men/women) | 7/11 | 6/7 | 3/6 | 0/9 | 3/9 | 3/9 |

| Age (years) | 75.2 ± 3.5 | 85.4 ± 2.7 | 83.4 ± 3.4 | 87.9 ± 2.0 | 88.8 ± 1.7 | 85.0 ± 1.9 |

| Brain pH | 6.43 ± 0.04 | 6.43 ± 0.07 | 6.31 ± 0.1 | 6.38 ± 0.09 | 6.34 ± 0.05 | 6.39 ± 0.07 |

| RNA integrity number (RIN) | 6.6 ± 0.1 | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 6.2 ± 0.1 |

| Postmortem intervals (minutes) | 713 ± 137 | 393 ± 85 | 264 ± 39 | 336 ± 66 | 276 ± 40 | 332 ± 80 |

4.1.2 Neuropathological Assessment and Dissection of Hippocampus

The hippocampus was dissected at the level of the mammillary bodies from flash frozen never thawed 8 mm-thick coronal sections of the left hemisphere. All samples were dissected while frozen, with neuropathological assessment blind to clinical diagnosis. The selection of hippocampus for study by qPCR was based on its high susceptibility to the disease (Bouras et al., 1994; Hof et al., 1992; Hyman et al., 1990; Lewis et al., 1987; Morrison et al., 1987). For pathologic staging of AD neurofibrillary tangle density was assessed using the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) (Mirra et al., 1987; Mirra et al., 1991) criteria, NFTs were evaluated using the criteria by Braak and Braak (Braak and Braak, 1991) (Table 1). Neuritic plaques were identified as the dystrophic neurites arranged radially and forming a discrete spherical lesion about 30 mm in diameter with amyloid cores. Neuritic plaques were counted and characterized as 1 = none, 2 = 1-5 per mm2, 3 = 6-10 per mm2 and 4 = 11 or more per mm2. Neuritic plaque groups in Table 1 reflect a composite score of neuritic plaques counts in 5 cortical regions. The composite measure of cortical neuritic plaque density was used to reflect better the general level of disease severity and to match more closely to the global assessment of cognitive function measured by the CDR.

4.2.1 RNA Isolation

Total RNA was isolated from 50 mg of microdissected pulverized frozen brain samples from hippocampus with the guanidinium isothiocyanate method (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987) using ToTALLY RNA kits (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer’s protocol as described previously (Katsel et al., 2009). To remove genomic DNA contamination, isolated RNA samples were treated with 40 units of DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX) in the presence of 120 units of RNaseOUT (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY) for 1 hour at 37°C. The quality of the isolated total RNA for each case was assessed using a combination of 260 nm/280 nm ratio obtained spectrophotometrically (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA) and by Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) before proceeding with cDNA synthesis. Only specimens with an RNA integrity number (RIN) ≥ 5.5 were included in the analyses.

4.2.2 Reverse Transcriptase Reaction

cDNA synthesis was performed with iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) which uses both random and poly-dT priming for the reverse transcription (RT) reaction. Total RNA (1 μg) was employed for each 20 μl reaction. The resulting cDNA was diluted 25 times for qPCR.

4.2.3 Real-Time PCR

ABCA1 mRNA expression was measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and gene-specific fluorogenic TaqMan® probes (Applied Biosystems). Each 20 μl PCR reaction contained 5 μl of the relevant cDNA, 20X TaqMan® assay (used at a final concentration of 0.5X), and 10 μl of TaqMan® Universal PCR Reaction Mix which contains ROX as a passive internal reference (Applied Biosystems). The thermal cycling program consisted of 2 min at 50 °C, 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C. The reactions were quantified by selecting the amplification cycle when the PCR product of interest was first detected (threshold cycle, Ct). Tests of primers and probes sensitivity and assay linearity were conducted for all real-time PCR assays by amplification of mRNA in 10-fold serial dilutions of pooled as previously described (Dracheva et al., 2001). Each reaction was performed in triplicate and the average Ct value was used in all analyses.

The relative gene expression level of ABCA1 was calculated using the Relative Standard Curve Method (see Guide to Performing Relative Quantitation of Gene Expression Using Real-time Quantitative PCR, Applied Biosystems) which accounts for differences in the efficiencies of the target and control amplifications, thereby, producing accurate, quantitative results. Standard curves were generated for target assay and for each endogenous control assay by the association between the Ct values and different quantities (5 serial dilution steps) of a “calibrator” cDNA. The “calibrator” was prepared by mixing small quantities of all experimental samples. Expression values of ABCA1 and the control genes were extrapolated from their respective standard curves. Relative expression of target gene was computed as the ratio of the target mRNA level to the geometric mean of the four endogenous controls: β-glucuronidase (GUSB), cyclophilin A (PP1A), β2-microglobulin (β2M), and ribosomal protein, large, P0 (RPLP0) which were picked for their stability using geNorm (Vandesompele et al., 2002;Byne et al., 2008). Samples with Ct values < 33 were considered outside the range of sensitivity of the assay and were not included in the analyses.

4.3 Protein Quantitation

Protein expression studies were carried out to determine whether different levels of ABCA1 gene expression were reflected in the expression level of ABCA1 protein. Because of the inherently lower reproducibility and higher variability characteristic of Westerns in postmortem tissue relative to qPCR, we restricted ABCA1 protein analyses to cases with most robust changes in gene expression. Therefore, a subset of the hippocampal samples (N = 33) studied for mRNA expression was analyzed by Western blotting to reflect broad variations in gene expression. As fewer protein analyses were performed than gene analyses, adjacent categories for all three indices of disease severity (see below) for gene expression analyses were combined to achieve sufficiently large sample sizes for comparisons (Table 1).

4.3.1 Tissue Lysate Preparation

Total tissue lysates were prepared from frozen hippocampal specimens from sister aliquots of the same brain samples as those used for qPCR analysis. Fifty mg pulverized tissue specimen were homogenized in 600 μl ice cold lysis buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 1% n-dodecyl-β-maltoside (DDM), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, supplemented with complete protease inhibitor (Roche Diagnostic, Mannheim, Germany) and 50 U of benzonuclease (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) for 1 min at 50% saturation. This was followed by incubation for 1 hr at 4 °C with constant shaking. The resultant homogenates were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4 °C and the supernatants containing tissue lysates were collected. Tissue pellet was resuspended with 400 μl of the above lysis buffer by repeating homogenization and centrifugation steps. The clear supernatants were pooled, mixed and used for determination of total protein concentration using a CBQCA Quantitation Kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR ) with fluorescence measured on a SpectraMAX Gemini XS spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

4.3.2 Western Blot Analysis

For gel electrophoresis, 20 μg of total protein was mixed with loading buffer and loaded onto pre-cast 7.5% Tris-glycine gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), and run at 125 V for ~1 hour. Each gel was loaded with three experimental samples in triplicate and “standard tissue homogenate” (the mix of small aliquots of tissue from all samples), also run in triplicate. Separated proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes at 100 V for 1 hour and probed with anti ABCA1 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) diluted 1:2,000 in 5 % non-fat dry milk in TBS overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. To ensure equal protein loading between individual samples, membranes were also incubated with an anti Valosin containing protein (VCP) antibody. VCP, a 97 kDa protein, has been previously validated as reliable internal standard (Bauer et al., 2009). Following 1 hour incubation with the secondary HRP conjugated antibodies, blots were developed using SuperSignal® West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Images made on Hyperfilm ECL (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) were digitized with Alpha ChemImager™ 5500 Imaging System and quantitated with AlphaEaseFC software (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). The average digital signal per band was measured after subtraction of the appropriate background. Optical density for each ABCA1 band was first normalized to the corresponding average signal for the standard tissue homogenate and then for the VCP band from the same sample. In addition to detection by chemiluminescence, VCP signal was also detected and quantified using the Odyssey IR imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). There was a high correlation (r = 0.88) between the signals detected by both methods. The linearity of the dose responses for the antibodies used was established in preliminary experiments.

4.4 Statistical Analyses

We performed a logarithmic transformation of ABCA1 gene expression to eliminate heterogeneity, and used the transformed gene expression values for all statistical analyses. Another preliminary analysis assessed linear associations with gender, pH, PMI and RIN to evaluate their use as covariates. Age and RIN were used as covariates in all analyses. PMI was associated with CDR at trend level, but could not be used a covariate in CDR analyses because it did not satisfy the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) requirement of homogeneity of regression coefficients.

The first analyses classified CDR, Braak stages and plaque density groupings as scales, and assessed their associations with ABCA1 gene expression by partial correlation, controlling for age and RIN. Because the associations of each of these interrelated scales with A_BCA1_ is at least partly mediated through the associations with the other two scales, additional partial correlation analyses assessed each scale controlling also for the other two scales.

In addition, CDR, Braak stages, and plaque density were treated as categorical variables, in order to be sensitive to non-linear as well as linear associations with ABCA1 gene expression. ANCOVA was performed for each categorical variable controlling for age and RIN. Another ANCOVA for each categorical variable controlled also for other two variables as scales, similar to the partial correlations.

For each categorical variable, some subjects were classified as not having AD: CDR = 0, Braak Staging = 0 and 1, and Plaque Density = 1. For each categorical variable, ANCOVA compared subjects with and without AD. In addition, parallel partial correlation and ANCOVAs to those described above were performed on subjects with AD only (for the respective categorical variable). These AD limited analyses were used to describe changes in ABCA1 expression as a function of disease progression. Analyses for protein expression were the same as for gene expression. All analyses were performed with SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH grants P01 AG02219 and AG05138.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Abad-Rodriguez J, Ledesma MD, Craessaerts K, Perga S, Medina M, Delacourte A, Dingwall C, De Strooper B, Dotti CG. Neuronal membrane cholesterol loss enhances amyloid peptide generation. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:953–960. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akram A, Katsel P, Hof PR, Haroutunian V. 2008 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Society for Neuroscience; Washington, DC: 2008. Coordinated transcriptional and translational changes in cholesterol transporters correlate with cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Program No. 45.8. 2008. Online. [Google Scholar]

- Akram A, Katsel P, Hof PR, Haroutunian V. 2007 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Society for Neuroscience; San Diego, CA: 2007. Changes in the expression of genes involved in cholesterol trafficking with the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Program No. 795.9. 2007. Online. [Google Scholar]

- Arispe N, Doh M. Plasma membrane cholesterol controls the cytotoxicity of Alzheimer’s disease Aβ(1-40) and (1-42) peptides. FASEB J. 2002;16:1526–1536. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0829com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair W. Visual receptive field organization. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:459–464. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KR, Verina T, Dodel RC, Du Y, Altstiel L, Bender M, Hyslop P, Johnstone EM, Little SP, Cummins DJ, Piccardo P, Ghetti B, Paul SM. Lack of apolipoprotein E dramatically reduces amyloid beta- peptide deposition. Nat Genet. 1997;17:263–264. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton AJ, Pearson RC, Najlerahim A, Harrison PJ. Pre- and postmortem influences on brain RNA. J Neurochem. 1993;61:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DE, Haroutunian V, McCullumsmith RE, Meador-Woodruff JH. Expression of four housekeeping proteins in elderly patients with schizophrenia. J Neural Transm. 2009;116:487–491. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0143-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RD, Sagare AP, Friedman AE, Bedi GS, Holtzman DM, Deane R, Zlokovic BV. Transport pathways for clearance of human Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide and apolipoproteins E and J in the mouse central nervous system. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:909–918. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette-Mackie EJ, Dwyer NK, Amende LM, Kruth HS, Butler JD, Sokol J, Comly ME, Vanier MT, August JT, Brady RO, Pentchev PG. Type-C Niemann-Pick disease: low density lipoprotein uptake is associated with premature cholesterol accumulation in the Golgi complex and excessive cholesterol storage in lysosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:8022–8026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodovitz S, Klein WL. Cholesterol modulates alpha-secretase cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4436–4440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodzioch M, Orso E, Klucken J, Langmann T, Bottcher A, Diederich W, Drobnik W, Barlage S, Buchler C, Porsch-Ozcurumez M, Kaminski WE, Hahmann HW, Oette K, Rothe G, Aslanidis C, Lackner KJ, Schmitz G. The gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 is mutated in Tangier disease. Nat Genet. 1999;22:347–351. doi: 10.1038/11914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouras C, Hof PR, Giannakopoulos P, Michel JP, Morrison JH. Regional distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in the cerebral cortex of elderly patients: a quantitative evaluation of a one-year autopsy population from a geriatric hospital. Cereb Cortex. 1994;4:138–150. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.2.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Wilson A, et al. Mutations in ABC1 in Tangier disease and familial high-density lipoprotein deficiency. Nat Genet. 1999;22:336–345. doi: 10.1038/11905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A proteolytic pathway that controls the cholesterol content of membranes, cells, and blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11041–11048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke WJ, Miller JP, Rubin EH, Morris JC, Coben LA, Duchek J, Wittels IG, Berg L. Reliability of the Washington University Clinical Dementia Rating. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:31–32. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520250037015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns MP, Vardanian L, Pajoohesh-Ganji A, Wang L, Cooper M, Harris DC, Duff K, Rebeck GW. The effects of ABCA1 on cholesterol efflux and Abeta levels in vitro and in vivo. J Neurochem. 2006;98:792–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byne W, Dracheva S, Chin B, Schmeidler JM, Davis KL, Haroutunian V. Schizophrenia and sex-associated differences in the expression of neuronal and oligodendrocyte specific genes in individual thalamic nuclei. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Analy Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combes V, Coltel N, Alibert M, van Eck M, Raymond C, Juhan-Vague I, Grau GE, Chimini G. ABCA1 gene deletion protects against cerebral malaria: potential pathogenic role of microparticles in neuropathology. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:295–302. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62253-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, Roses AD, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s Disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261:921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crameri A, Biondi E, Kuehnle K, Lutjohann D, Thelen KM, Perga S, Dotti CG, Nitsch RM, Ledesma MD, Mohajeri MH. The role of seladin-1/DHCR24 in cholesterol biosynthesis, APP processing and Abeta generation in vivo. EMBO J. 2006;25:432–443. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane R, Sagare A, Hamm K, Parisi M, Lane S, Finn MB, Holtzman DM, Zlokovic BV. apoE isoform-specific disruption of amyloid beta peptide clearance from mouse brain. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:4002–4013. doi: 10.1172/JCI36663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietschy JM, Turley SD. Cholesterol metabolism in the brain. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2001;12:105–112. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200104000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distl R, Treiber-Held S, Albert F, Meske V, Harzer K, Ohm TG. Cholesterol storage and tau pathology in Niemann-Pick type C disease in the brain. J Pathol. 2003;200:104–111. doi: 10.1002/path.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dracheva S, Elhakem SL, Gluck MR, Siever LJ, Davis KL, Haroutunian V. Glutamate synthesis and NMDA receptor and PSD-95 expression in DLPFC and occipital cortices of schizophrenics. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Duong PT, Collins HL, Nickel M, Lund-Katz S, Rothblat GH, Phillips MC. Characterization of nascent HDL particles and microparticles formed by ABCA1-mediated efflux of cellular lipids to apoA-I. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:832–43. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500531-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehehalt R, Keller P, Haass C, Thiele C, Simons K. Amyloidogenic processing of the Alzheimer beta-amyloid precursor protein depends on lipid rafts. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:113–123. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan QW, Yu W, Senda T, Yanagisawa K, Michikawa M. Cholesterol-dependent modulation of tau phosphorylation in cultured neurons. J Neurochem. 2001;76:391–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassbender K, Simons M, Bergmann C, Stroick M, Lutjohann D, Keller P, Runz H, Kuhl S, Bertsch T, von Bergmann K, Hennerici M, Beyreuther K, Hartmann T. Simvastatin strongly reduces levels of Alzheimer’s disease beta -amyloid peptides Abeta 42 and Abeta 40 in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5856–5861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081620098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielding CJ, Fielding PE. Molecular physiology of reverse cholesterol transport. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:211–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto H, Deng A, Irizarry MC, Fitzgerald ML, Rebeck GW. Induction of the cholesterol transporter ABCA1 in central nervous system cells by liver X receptor agonists increases secreted Abeta levels. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48508–48513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin JS, Drake KR, Remmert CL, Kenworthy AK. Ras diffusion is sensitive to plasma membrane viscosity. Biophys J. 2005;89:1398–1410. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.055640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J, Li K, Li K, Zhang D, Wang W, Yang Y, Yan B, Shan B, Zhou X. Visual attention deficits in Alzheimer’s disease: an fMRI study. Neurosci Lett. 2005;385:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch-Reinshagen V, Chan JY, Wilkinson A, Tanaka T, Fan J, Ou G, Maia LF, Singaraja RR, Hayden MR, Wellington CL. Physiologically regulated transgenic ABCA1 does not reduce amyloid burden or amyloid-beta peptide levels in vivo. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:914–923. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600543-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch-Reinshagen V, Maia LF, Burgess BL, Blain JF, Naus KE, McIsaac SA, Parkinson PF, Chan JY, Tansley GH, Hayden MR, Poirier J, Van Nostrand W, Wellington CL. The absence of ABCA1 decreases soluble ApoE levels but does not diminish amyloid deposition in two murine models of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43243–43256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof PR, Bierer LM, Perl DP, Delacourte A, Buee L, Bouras C, Morrison JH. Evidence for early vulnerability of the medial and inferior aspects of the temporal lobe in an 82-year-old patient with preclinical signs of dementia. Regional and laminar distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:946–953. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530330070019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman DM, Bales KR, Wu S, Bhat P, Parsadanian M, Fagan AM, Chang LK, Sun Y, Paul SM. Expression of human apolipoprotein E reduces amyloid-beta deposition in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:R15–R21. doi: 10.1172/JCI6179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman DM, Fagan AM, Mackey B, Tenkova T, Sartorius L, Paul SM, Bales K, Ashe KH, Irizarry MC, Hyman BT. Apolipoprotein E facilitates neuritic and cerebrovascular plaque formation in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:739–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter-Paier B, Huttunen HJ, Puglielli L, Eckman CB, Kim DY, Hofmeister A, Moir RD, Domnitz SB, Frosch MP, Windisch M, Kovacs DM. The ACAT inhibitor CP-113,818 markedly reduces amyloid pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2004;44:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman BT, Van Hoesen GW, Damasio AR. Memory-related neural systems in Alzheimer’s disease: an anatomic study. Neurology. 1990;40:1721–1730. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.11.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Ohtsuki S, Kamiie J, Nezu Y, Terasaki T. Cerebral clearance of human amyloid-beta peptide (1-40) across the blood-brain barrier is reduced by self-aggregation and formation of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 ligand complexes. J Neurochem. 2007;103:2482–2490. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SA, Morgan DG, Finch CE. Extensive postmortem stability of RNA from rat and human brain. J Neurosci Res. 1986;16:267–280. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490160123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsel P, Tan W, Haroutunian V. Gain in brain immunity in the oldest-old differentiates cognitively normal from demented individuals. PloS ONE. 2009;4:e7642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzov H, Chalmers K, Palmgren J, Andreasen N, Johansson B, Cairns NJ, Gatz M, Wilcock GK, Love S, Pedersen NL, Brookes AJ, Blennow K, Kehoe PG, Prince JA. Genetic variants of ABCA1 modify Alzheimer disease risk and quantitative traits related to beta-amyloid metabolism. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:358–367. doi: 10.1002/humu.20012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kergoat H, Kergoat MJ, Justino L, Chertkow H, Robillard A, Bergman H. Visual retinocortical function in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Gerontology. 2002;48:197–203. doi: 10.1159/000058350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WS, Guillemin GJ, Glaros EN, Lim CK, Garner B. Quantitation of ATP-binding cassette subfamily-A transporter gene expression in primary human brain cells. Neuroreport. 2006;17:891–896. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000221833.41340.cd. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WS, Rahmanto AS, Kamili A, Rye KA, Guillemin GJ, Gelissen IC, Jessup W, Hill AF, Garner B. Role of ABCG1 and ABCA1 in regulation of neuronal cholesterol efflux to apolipoprotein E discs and suppression of amyloid-beta peptide generation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2851–2861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Laakso MP, Hanninen T, Hallikainen M, Alhainen K, Soininen H, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A. Midlife vascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease in later life: longitudinal, population based study. Br Med J. 2001;322:1447–1451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7300.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojro E, Gimpl G, Lammich S, Marz W, Fahrenholz F. Low cholesterol stimulates the nonamyloidogenic pathway by its effect on the alpha-secretase ADAM 10. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5815–5820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081612998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koldamova RP, Lefterov IM, Ikonomovic MD, Skoko J, Lefterov PI, Isanski BA, DeKosky ST, Lazo JS. 22R-hydroxycholesterol and 9-cis-retinoic acid induce ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 expression and cholesterol efflux in brain cells and decrease amyloid beta secretion. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13244–13256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koudinov AR, Koudinova NV. Essential role for cholesterol in synaptic plasticity and neuronal degeneration. FASEB J. 2001;15:1858–1860. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0815fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry A, Xavier R. Isolation and analysis of lipid rafts in cell-cell interactions. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;341:251–282. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-113-4:251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry YD, Denis M, Nandi S, Bell S, Vaughan AM, Zha X. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 expression disrupts raft membrane microdomains through its ATPase-related functions. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36091–36101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmann T, Klucken J, Reil M, Liebisch G, Luciani MF, Chimini G, Kaminski WE, Schmitz G. Molecular cloning of the human ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 (hABC1): evidence for sterol-dependent regulation in macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:29–33. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma MD, Abad-Rodriguez J, Galvan C, Biondi E, Navarro P, Delacourte A, Dingwall C, Dotti CG. Raft disorganization leads to reduced plasmin activity in Alzheimer’s disease brains. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:1190–1196. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma MD, Da Silva JS, Crassaerts K, Delacourte A, De SB, Dotti CG. Brain plasmin enhances APP alpha-cleavage and Abeta degradation and is reduced in Alzheimer’s disease brains. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:530–535. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma MD, Dotti CG. The conflicting role of brain cholesterol in Alzheimer’s disease: lessons from the brain plasminogen system. Biochem Soc Symp. 2005:129–138. doi: 10.1042/bss0720129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AG, Martin CO. Neuro-ophthalmic findings in the visual variant of Alzheimer’s disease. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:376–380. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00732-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Campbell MJ, Terry RD, Morrison JH. Laminar and regional distributions of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in Alzheimer’s disease: a quantitative study of visual and auditory cortices. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1799–1808. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-06-01799.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipska BK, Deep-Soboslay A, Weickert CS, Hyde TM, Martin CE, Herman MM, Kleinman JE. Critical factors in gene expression in postmortem human brain: Focus on studies in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:650–658. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado RA, Irvine DJ, Schreiber R, Glimcher LH. A role for the immunological synapse in lineage commitment of CD4 lymphocytes. Nature. 2004;431:527–532. doi: 10.1038/nature02916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti M, Monier MN, Fradagrada A, Mitchell K, Baychelier F, Eid P, Johannes L, Lamaze C. Stat-mediated signaling induced by type I and type II interferons (IFNs) is differentially controlled through lipid microdomain association and clathrin-dependent endocytosis of IFN receptors. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2896–2909. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-01-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason RP, Shoemaker WJ, Shajenko L, Chambers TE, Herbette LG. Evidence for changes in the Alzheimer’s disease brain cortical membrane structure mediated by cholesterol. Neurobiol Aging. 1992;13:413–419. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(92)90116-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, Vogel FS, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Berg L. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirra SS, Vogel FS, Heyman A. Guide to the CERAD protocol for the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. CERAD; Durham, NC: 1987. 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Molander-Melin M, Blennow K, Bogdanovic N, Dellheden B, Mansson JE, Fredman P. Structural membrane alterations in Alzheimer brains found to be associated with regional disease development; increased density of gangliosides GM1 and GM2 and loss of cholesterol in detergent-resistant membrane domains. J Neurochem. 2005;92:171–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JH, Lewis DA, Campbell MJ, Huntley GW, Benson DL, Bouras C. A monoclonal antibody to non-phosphorylated neurofilament protein marks the vulnerable cortical neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1987;416:331–336. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90914-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund J, Schierhorn A, Hellman U, Lannfelt L, Roses AD, Tjernberg LO, Silberring J, Gandy SE, Winblad B, Greengard P. Relative abundance of Alzheimer A beta amyloid peptide variants in Alzheimer disease and normal aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8378–8382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglielli L, Tanzi RE, Kovacs DM. Alzheimer’s disease: the cholesterol connection. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:345–351. doi: 10.1038/nn0403-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit DP, Perl DP, Haroutunian V, Powchik P, Davidson M, Davis KL. Alzheimer disease and related neurodegenerative diseases in elderly patients with schizophrenia: a postmortem neuropathologic study of 100 cases. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:205–211. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refolo LM, Pappolla MA, LaFrancois J, Malester B, Schmidt SD, Thomas-Bryant T, Tint GS, Wang R, Mercken M, Petanceska SS, Duff KE. A cholesterol-lowering drug reduces beta-amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:890–899. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repa JJ, Mangelsdorf DJ. The liver X receptor gene team: potential new players in atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2002;8:1243–1248. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CA, Hong MG, Eriksson UK, Blennow K, Bennet AM, Johansson B, Malmberg B, Berg S, Wiklund F, Gatz M, Pedersen NL, Prince JA. A survey of ABCA1 sequence variation confirms association with dementia. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1348–1354. doi: 10.1002/humu.21076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez E, Mateo I, Llorca J, Sánchez-Quintana C, Infante J, García-Gorostiaga I, Sánchez-Juan P, Berciano J, Combarros O. Association of genetic variants of ABCA1 with Alzheimer’s disease risk. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:964–968. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW. Oxysterol biosynthetic enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1529:126–135. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura N, Gong JS, Chang TY, Yanagisawa K, Michikawa M. Promotion of tau phosphorylation by MAP kinase Erk1/2 is accompanied by reduced cholesterol level in detergent-insoluble membrane fraction in Niemann-Pick C1-deficient cells. J Neurochem. 2003;84:1086–1096. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shobab LA, Hsiung GY, Feldman HH. Cholesterol in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:841–852. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons M, Keller P, De Strooper B, Beyreuther K, Dotti CG, Simons K. Cholesterol depletion inhibits the generation of beta-amyloid in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6460–6464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani M, Liguri G. Cholesterol in Alzheimer’s disease: unresolved questions. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6:15–29. doi: 10.2174/156720509787313899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Yao J, Kim TW, Tall AR. Expression of liver X receptor target genes decreases cellular amyloid beta peptide secretion. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27688–27694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Parker CC, Pentchev PG, Katz D, Ghetti B, D’Agostino AN, Carstea ED. Neurofibrillary tangles in Niemann-Pick disease type C. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1995;89:227–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00309338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachikawa M, Watanabe M, Hori S, Fukaya M, Ohtsuki S, Asashima T, Terasaki T. Distinct spatio-temporal expression of ABCA and ABCG transporters in the developing and adult mouse brain. J Neurochem. 2005;95:294–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker HM, Kihiko-Ehmann M, Wright S, Rydel RE, Estus S. Tissue plasminogen activator requires plasminogen to modulate amyloid-beta neurotoxicity and deposition. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2172–2177. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance JE, Hayashi H, Karten B. Cholesterol homeostasis in neurons and glial cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:193–212. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:0034.1–0034.11. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanier MT, Suzuki K. Recent advances in elucidating Niemann-Pick C disease. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:163–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vawter MP, Tomita H, Meng F, Bolstad B, Li J, Evans S, Choudary P, Atz M, Shao L, Neal C, Walsh DM, Burmeister M, Speed T, Myers R, Jones EG, Watson SJ, Akil H, Bunney WB. Mitochondrial-related gene expression changes are sensitive to agonal-pH state: implications for brain disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:663–679. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahrle S, Das P, Nyborg AC, McLendon C, Shoji M, Kawarabayashi T, Younkin LH, Younkin SG, Golde TE. Cholesterol-dependent gamma-secretase activity in buoyant cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;9:11–23. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahrle SE, Jiang H, Parsadanian M, Hartman RE, Bales KR, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. Deletion of Abca1 increases Abeta deposition in the PDAPP transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43236–43242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508780200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellington CL, Walker EK, Suarez A, Kwok A, Bissada N, Singaraja R, Yang YZ, Zhang LH, James E, Wilson JE, Francone O, McManus BM, Hayden MR. ABCA1 mRNA and protein distribution patterns predict multiple different roles and levels of regulation. Lab Invest. 2002;82:273–283. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollmer MA, Streffer JR, Lütjohann D, Tsolaki M, Iakovidou V, Hegi T, Pasch T, Jung HH, Bergmann K, Nitsch RM, Hock C, Papassotiropoulos A. ABCA1 modulates CSF cholesterol levels and influences the age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:421–426. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolozin B, Kellman W, Ruosseau P, Celesia GG, Siegel G. Decreased prevalence of Alzheimer disease associated with 3-hydroxy-3-methyglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:1439–1443. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.10.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey PG, Bortnick AE, Kellner-Weibel G, Llera-Moya M, Phillips MC, Rothblat GH. Importance of different pathways of cellular cholesterol efflux. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:712–719. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000057572.97137.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarubica A, Plazzo AP, Stockl M, Trombik T, Hamon Y, Muller P, Pomorski T, Herrmann A, Chimini G. Functional implications of the influence of ABCA1 on lipid microenvironment at the plasma membrane: a biophysical study. FASEB J. 2009;23:1775–1785. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-122192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarubica A, Trompier D, Chimini G. ABCA1, from pathology to membrane function. Pflugers Arch. 2007;453:569–579. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0108-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]