Organizing the Cell Cortex: The role of ERM proteins (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2010 Oct 1.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010 Apr;11(4):276–287. doi: 10.1038/nrm2866

Abstract

Specialized membrane domains are an important feature of almost all cells. In particular, they are essential to tissues such as the intestinal brush border epithelium, that have a highly organized cell cortex including a complex array of apical microvilli, an apical junctional complex, and a basolateral membrane domain. The ERM proteins (ezrin, radixin and moesin) have a crucial role in organizing membrane domains through their ability to interact with transmembrane proteins and the underlying cytoskeleton. In so doing, they not only can provide structural links to strengthen the cell cortex, but also can regulate the activities of signal transduction pathways. Recent studies, primarily focused on structural analysis of these proteins and their binding partners, together with genetic dissection of their in vivo functions, have significantly advanced our understanding of the importance of membrane–cytoskeletal interactions.

Recent studies in signal transduction have highlighted the importance of specialized membrane domains, such as the apical junctional domain and the immunological synapse, in bringing ligands, receptors and downstream components in close proximity1. The ability to organize and maintain specialized membrane domains is essential to most, if not all cells. To do this, cells must coordinate processes at the cell surface with those occurring within the underlying cortical cytoplasm and cytoskeleton. For example, the formation of complex subcellular structures at the apical end of the cell, such as microvilli and intercellular junctions, requires close interactions between the plasma membrane, membrane-associated cytoplasmic proteins and the underlying cytoskeleton.

Studies over the past 25 years have implicated ezrin, radixin and moesin, collectively known as the ERM proteins, as key organizers of specialized membrane domains. The ERMs are expressed in a developmental and tissue-specific manner, with many epithelial cells expressing predominantly ezrin and many endothelial cells expressing predominantly moesin. This suggests that different ERM functions are tailored to the needs of specific cell types (BOX 1). Through their ability to interact with transmembrane proteins, phospholipids, membrane-associated cytoplasmic proteins and the cytoskeleton, ERMs organize complex membrane domains. In addition, genetic studies in the past few years have revealed an unexpected diversity of functions, including villar organization in the gut2, light-regulated maintenance of photoreceptors3, control of cortical stiffening during mitosis4, 5, and regulation of RhoA activity in epithelial cells6, for these proteins. Together, these data present a uniquely rich understanding of ERM protein regulation and functions.

BOX 1. Functional redundancy and diversity among mammalian ERM proteins.

In mammals, ezrin, radixin and moesin are encoded by three genes (in humans on chromosomes 6, 11 and X, respectively) that appear to each give rise to a single protein species. The proteins show tissue specificity, with ezrin being present mostly in epithelial cells, moesin in endothelial cells, and radixin in hepatocytes. ERMs share striking amino acid identity but a few notable features suggest possible functional diversity. For example, ezrin can be tyrosine phosphorylated on residues that are not present in moesin or radixin99, and moesin lacks proline-rich sequences that are found in ezrin and radixin100.

While ezrin-deficient mice die within 3 weeks of age and have defects that are apparently limited to the gastrointestinal tract2, initial studies revealed that inactivation of radixin in the mouse yielded viable animals that exhibited relatively subtle liver defects101, while moesin-deficient mice did not exhibit overt phenotypes102. The paucity of phenotypes in these mice suggests that other ERMs can compensate for the loss of individual ERMs in many tissues.

However, additional studies have uncovered additional crucial roles for individual ERMs in vivo. For example, homozygosity for a severely hypomorphic allele of Ezrin yields defective acid secretion by gastric parietal cells. Interestingly, this phenotype is associated with a failure of the formation and function of apical canaliculi, which deliver acid-secreting pumps to the apical surface of the parietal cells103. Another interesting example involves the loss of hearing and selective degeneration of stereocilia in the inner ear of radixin-deficient mice; this study also revealed that radixin and ezrin are crucial for the maintenance of different stereocilia subtypes104. Most recently, roles for moesin in hepatic stellate cell migration and alveolar wound healing have been identified105, 106. These studies do not distinguish between a requirement for tissue-specific expression of individual ERMs versus truly functionally divergent roles for ERMs per se, although work on the immunological synapse (see main text) indicates that ezrin and moesin can display distinct functions. A better understanding of redundancy and diversity of ERM function will require genetic studies in which, for example, the Ezrin coding region is knocked into the Moesin locus.

Early studies of ERMs concentrated on their biochemical interactions and functions in cultured mammalian cells. These aspects of ERM function have been extensively reviewed elsewhere7–10 and will be touched on only briefly here. More recently, considerable progress has been made in two diverse areas: elucidating the structural properties of ERMs and understanding their functions in living tissues. In this Review we discuss well-established biochemical models for ERM regulation and describe how they relate to recent work that explores ERM structure and cellular functions during development, immune responses and disease.

Regulation of ERM function

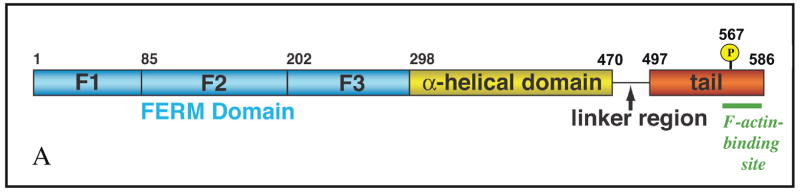

ERMs are characterized by the presence of a ~300 amino acid plasma membrane-associated FERM domain, followed by a long region with a high α-helical propensity and terminating in a C-terminal domain (also known as the C-ERMAD: C-terminal ERM-association domain) that has the ability to bind the FERM domain or F-actin (Fig. 1A).

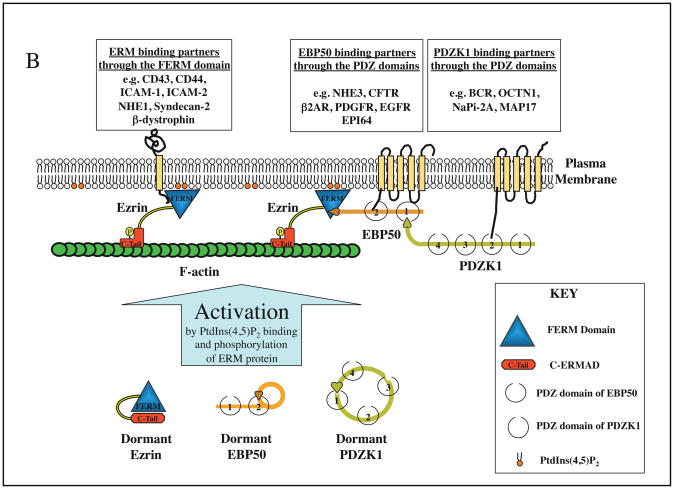

Figure 1. Domain organization of ERM proteins and activation model.

A| All ERMs have a similar domain structure. The domain organization of ezrin is represented here. The N-terminal FERM domain (blue) consists of three subdomains, designated F1, F2, F329 or A, B, C39. The central ~150 residue region (yellow) is predicted to have a high α-helical content and propensity to assemble into a coiled-coil structure. This is followed by a linker region that is rich in proline residues in ezrin and radixin, but not moesin, and the protein terminates in the C-ERMAD (red) containing the F-actin-binding site (green). B | Ezrin is activated through PtdIns(4,5)P2 binding and phosphorylation of threonine 567, which reduces the affinity of the N-terminal FERM domain (blue) for the C-ERMAD (C-Tail, red). This unmasks binding sites for F-actin (green), the cytoplasmic tails of specific membrane proteins, and the adaptor protein EBP50. As EBP50 binding to the FERM domain reduces the affinity of the FERM domain for the cytoplasmic tails of membrane proteins47, these two ERM binding modes might be mutually exclusive as shown. The PDZ domains of EBP50 can bind additional proteins, including the scaffolding protein PDZK1. Moesin and radixin are thought to function in a similar manner and bind many of the same, or related, proteins, although in general they have not been as well studied. EBP50 and PDZK1 are believed to exist in a closed form. Upon unmasking of the EBP50 binding site on the ezrin FERM domain, the open conformation of EBP50 is stabilized and binds ezrin. A similar type of mechanism might also exist for PDZK1.

Two findings led to the discovery that ERM protein function is conformationally regulated by head to tail folding (that is, binding of the C-terminal C-ERMAD to the N-terminal FERM domain). First, an F-actin binding site was identified in the last 34 residues of ezrin11, and second, the ~80 C-terminal residues of ezrin, designated the C-ERMAD, were found to bind tightly to the FERM domain in such a way that the F-actin binding site was masked12. We now know that all ERMs exist in an apparently dormant, closed conformation and that release of the C-terminal domain from the FERM domain is necessary for their full activation to expose binding sites in the FERM domain and the C-terminal F-actin binding site (Fig. 1B). Current ideas suggest that the dormant protein is spring-loaded, so that when the affinity between the FERM domain and the C-ERMAD is reduced, the molecule pops open allowing it to connect the membrane to the underlying actin cytoskeleton.

Regulation of ERMs by phosphorylation

The first insights into the molecular mechanism of the regulation of ERMs came with the discovery that moesin is phosphorylated on threonine 558 (which is located within the C-ERMAD) during platelet activation13, and numerous other studies then showed that the equivalent residue in ezrin, radixin and moesin (T576, T564, T558, respectively) can lead to activation. A two-step model of activation has been proposed in which ERMs are recruited to membrane regions rich in phosphatidylinositol, 4,5-bisphosphate (PdIns(4,5)P2), perhaps rendering the conserved threonine amino acid residue more accessible to phosphorylation14, 15. A number of kinases in vertebrate cells can phosphorylate ERMs on this regulatory threonine, including Rho Kinase, PKCα, PKCθ, NIK, Mst4 and LOK16–20.

In vivo studies in D. melanogaster, which has a single ERM called Moesin21, have provided further evidence that ERMs are activated when they adopt an open conformation following phosphorylation of the regulatory threonine. Several studies have shown that a single kinase, Slik, appears to be responsible for phosphorylation at this residue4, 5, 22, 23, though one study has also demonstrated that Rho kinase mutations affect phospho-Moesin staining in the oocyte24. Mutations that mimic phosphorylation (T559D) or abolish phosphorylation (T559A) at the regulatory threonine residue of the C-ERMAD have been tested for their ability to rescue Moesin mutations. As predicted by the conformational regulation model, transgenically-expressed, N-terminally MYC-tagged MoeT559D rescues Moesin mutations, whereas MoeT559A does not6. Interestingly, two other studies have obtained somewhat different results. Polesello et al. found that neither allele provided genetic rescue25, and Karagiosis and Ready found that the T559D allele had strongly dominant phenotypes when expressed in the developing eye26. Both of these studies used Moesin transgenes that had been C-terminally tagged with either GFP or six copies of the MYC epitope. However, biochemical studies have raised the possibility that C-terminal tags might disrupt hydrogen bonding between the FERM domain and the C-terminal hydroxyl group, thereby interfering with the intramolecular head to tail interaction and altering ERM function27.

Additional mechanisms of ERM activation have also been described in vertebrates. CDK5 can phosphorylate ezrin’s threonine 235 of ezrin28 which lies on the FERM/C-ERMAD interface directly opposite threonine 56729. In addition to threonine residues, ezrin can be phosphorylated on tyrosines 145 and 353 by various tyrosine kinases, including the EGF receptor30, but how these modifications affect the conformation and function of ezrin is still unclear.

Binding partners of ERMs

As mentioned above, phosphorylation of ERMs at the regulatory threonine residue reduces the affinity of the C-ERMAD for the FERM domain, and this active conformation allows other proteins to bind. Numerous proteins can bind the FERM domain; the regulatory subunit of protein A-kinase binds the α-helical region31, and F-actin binds the tail. An account of the FERM domain binding proteins has been provided elsewhere32, so only a few key points will be made here.

The FERM domain of activated ERMs can bind directly to the cytoplasmic tails of many membrane proteins, including CD44, CD43, and intracellular adhesion molecule 2 (ICAM2)33 (Fig. 1B). A distinct site on the FERM domain can bind to the related scaffolding proteins EBP50 (also known as NHERF1) and E3KARP (also known as NHERF2), each of which has two PDZ domains followed by an ERM binding domain. Therefore, the FERM domain can bind at least two different classes of membrane-associated proteins. Since EBP50 and E3KARP have been found to bind multiple different membrane proteins themselves34, the number of proteins that have the potential to bind the FERM domain directly or indirectly is large. Further expanding the possible repertoire of associated proteins involves PDZK1, a scaffolding protein that has four PDZ domains, linking through its tail to the PDZ domains of EBP5035. Interestingly, like ERMs, EBP50 and PDZK1 are conformationally regulated by intra-molecular associations (Fig. 1B)35–37 that perhaps modulate affinities for their ligands.

The overall model that emerges of ERMs is that their activity is regulated by many signal transduction pathways, and when active they can potentially assemble clusters of specific membrane proteins and link them to F-actin.

Structural insights into ERM function

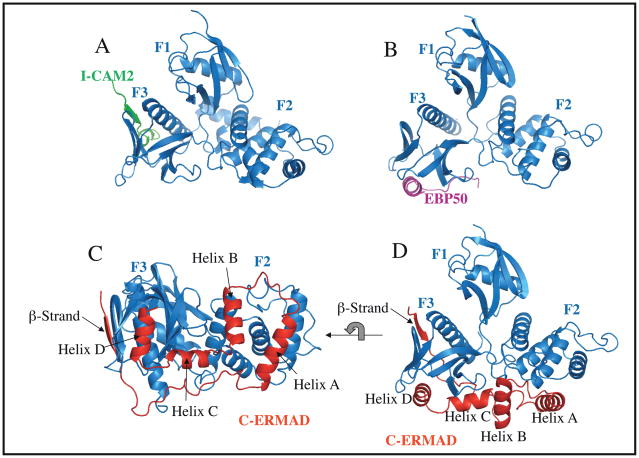

Several structures have been described that provide insights into how ERMs function. The X-ray structures of the ~300 amino acid residue FERM domains of ERMs have all been solved independently (ezrin38; radixin39; moesin40) and, as expected from their high sequence conservation, are very similar. The FERM domain can be divided into three subdomains (F1, F2 and F3 or A, B, C) arranged like a cloverleaf (Fig. 2), that each have structural (but not sequence) homology to a known protein fold. Thus F1 is very similar to ubiquitin, F2 to acyl-CoA binding protein, and F3 to a PTB domain. The structure of the isolated FERM domain provides a view of the ‘active’ structure free of the inhibitory C-ERMAD.

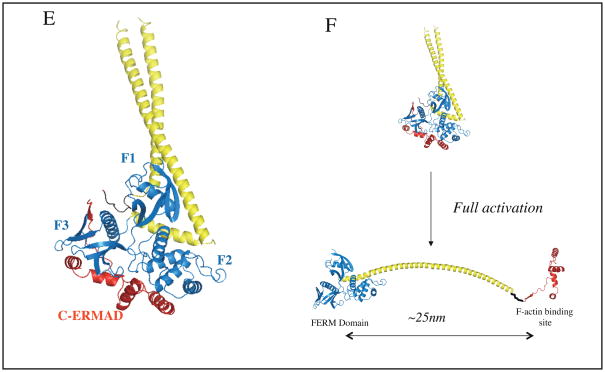

Figure 2. Structures of FERM domains with bound ligands.

A| The radixin FERM domain complexed with a peptide from the cytoplasmic tail of ICAM2. The β-strand binds to a groove on the F3 subdomain.43. B | The moesin FERM domain with the C-terminal peptide of EBP50 bound. The tail of EBP50 forms an α-helix that binds to the surface of the F3 subdomain46, 47. C–D | Two views of the C-ERMAD of moesin bound to the moesin FERM domain. The C-ERMAD binds the F2 and F3 subdomains through a β-strand followed by four helices (helix A, B, C and D)29. In the orientation corresponding to panels A and B, it can be seen that the β-strand occupies the same groove that binds ICAM2, and helix D binds to the same surface as EBP50. E | Full length insect (Spodoptera frugiperda) moesin dormant structure revealing the structure of the central α-helical region50. F | A conceptual model of the activation of ERMs involving the complete dissociation of the C-ERMAD from the FERM domain and allowing the central the α-helical region to unravel and potentially span up to 25nm. The figures were assembled from Protein Data Bank files 1J19 (panel A), 1SGH (panel B), 1EF1 (panels C and D) and 2I1J (panel E).

The crystal structure of the radixin FERM domain bound to the cytoplasmic tail of ICAM-2, CD43, or P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1) identified a consensus (R/K/Q)xxT(Y/L)xx(A/G) sequence (in which × denotes any amino acid) that binds in a groove bordered by a β-strand and an α-helix of subdomain F3 involving an antiparallel β-strand β-strand interaction (Fig. 2A) in a manner very similar to the phospho-peptide of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) recognition by PTB of the insulin receptor41–43. This groove has also been shown to be involved in the binding of the tails of the adhesion molecules CD44 and the neutral endopeptidase NEP through a different sequence44, 45. The FERM ligand EBP50 binds through its C-terminal region to a different surface on subdomain F3 (Fig. 2B)46. Extensive analysis of this interaction shows that the consensus sequence MDWxxxxx(L/I)Fxx(L/F) in EBP50 is necessary to bind the FERM domain, and that binding of EBP50 reduces the affinity of the FERM domain for ligands discussed above that bind to the same site as ICAM-247.

The moesin FERM domain complexed with the ~80 residue C-ERMAD revealed the structure of the ‘inactive’ FERM domain and the extended C-ERMAD consisting of a β-strand and four major α-helices to bind and mask a large surface of the F2 and F3 subdomains (Fig. 2C–D)29. A recent nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) study has shown that C-ERMAD helices bind the FERM domain independently, implying that each make a binding contribution to achieve the high affinity seen between the FERM domain and the C-ERMAD48. A number of features concerning this association are notable. First, the C-ERMAD contributes two helices, helix A and helix D, around which the mobile regions of subdomains F2 and F3 fold, thus contributing to the stability of the interaction38. Second, the C-ERMAD binds FERM surfaces that also bind ligands, for example the surface bound by the ICAM-2 peptide is occupied by the β-strand of the C-ERMAD, and binding site of the EBP50 C-terminal helix is occupied by helix D of the C-ERMAD (Fig. 2A–D). This masking of binding sites explains why EBP50 cannot bind to the FERM domain of the full-length dormant ERM or the FERM/C-ERMAD complex49.

Although attempts to crystallize full-length human ERMs have been difficult, the structure of the insect Spodoptera frugiperda moesin was recently reported revealing the location of the highly α-helical central region (Fig. 2E)50. The structure of the FERM and C-ERMAD regions are essentially identical to the corresponding structures of the human proteins, and the central region exists as three α-helices. The first helix, emerging from F3, folds back along F1 and F2, the second helix makes hydrophobic contacts with F1 and extends as an anti-parallel coiled-coil with the third helix which lands on the back of F1 and connects through a linker region to the C-ERMAD Fig. 2E). Interestingly, the linker lies in a pocket between F2 and F3 that can be occupied by inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3), the soluble head group of PtdIns(4,5)P2. This suggests that the linker region may become excluded from this site when PtdIns(4,5)P2 binds39. This is interesting as PtdIns(4,5)P2 binding has been implicated in the first step of ERM activation by inducing a conformational change to render the conserved threonine more accessible for phosphorylation15, 39.

Altogether, the biochemical and structural studies suggest that multiple signal transduction pathways can contribute to the complete opening of ERMs to activate the membrane-cytoskeleton linking activity of ERMs. They also hint at the possibility that functionally important intermediate states of ERM activation may also exist.

ERM proteins in cell signalling

Given their ability to mediate multiple interactions at the cell cortex, ERMs are ideally located to regulate the formation of specialized membrane domains. Such domains are essential for signal transduction because they bring receptors and downstream signalling components together in close proximity1. As described in the following paragraphs, genetic studies in Drosophila have provided direct evidence for ERM regulation of RhoA and Hedgehog signalling, though given their ability to interact with transmembrane receptors ERMs are likely involved in other signalling pathways as well.

RhoA signalling

RhoA, a small GTPase, is a key regulator of the cortical actin cytoskeleton. By interacting with downstream effectors, such as Rho kinase and formins, RhoA shapes the cytoskeleton, thereby regulating dynamic cellular processes, including morphogenesis, cytokinesis and cell migration (see below).

Early work on ERM and RhoA signalling concentrated on a potential role for ERMs as RhoA downstream effectors8, 51, 52. Recent work indicates that ERM may also function upstream to regulate RhoA activity. Several studies have shown that ERMs interact with proteins that regulate Rho GTPases, including RhoGEF, RhoGAP and RhoGDI53–56. In D. melanogaster Moesin has been proposed to negatively regulate Rho1, the fly RhoA orthologue, as reducing Rho1 genetic dosage (in _Rho1+/_− animals), strongly suppresses loss of function Moesin phenotypes including loss of epithelial integrity and lethality6, 22, 57. A similar suppression of Moesin phenotypes has been observed in cultured S2 cells using RhoA RNAi5. Consistent with these findings, levels of activated RhoA protein are increased in mammalian cells expressing a dominant-negative ezrin construct6.

Interestingly, other reports have concluded that rather than acting antagonistically to RhoA, mammalian ERMs positively regulate RhoA activity through interactions with RhoGEF and RhoGDI7, 58–60. These inconsistencies may reflect differences in experimental design or perhaps that ERMs function in a context-dependent manner. Regardless, our current knowledge of the functional interactions between RhoA and ERMs is rudimentary, and further study is needed.

Hedgehog signalling

The Hedgehog signalling pathway regulates cell fate specification and proliferation in a variety of tissues and developmental contexts. A recent study has used HYPOMORPHIC Moesin alleles that allow the examination of Moesin function during later developmental stages to study its function in adult wing patterning57. These mutations produce pattern defects in the adult wing veins, such as broadening of the third vein and alteration of inter-vein spacing. Examination of reporters for all of the major signalling pathways known to function in wing development, including Notch, Wingless, Decapentaplegic, Epidermal growth factor receptor and Hedgehog, revealed that only Hedgehog signalling is affected. More detailed analysis showed that Hedgehog targets that require low levels of signalling output are expressed normally, while those that require high levels are expressed poorly. These phenotypes are strongly suppressed by reducing Rho1 dosage, suggesting that these Moesin functions also involve Rho1 signalling. The mechanism by which Moesin facilitates high levels of Hedgehog signalling is not clear; however, a previous two-hybrid interaction study showed that Moesin interacts with Patched61, a Hedgehog receptor, suggesting that Moesin might regulate its function (see below).

Membrane receptor signalling

Patched is just one of a range of membrane receptors that interact with the FERM domain of ERMs either directly or through the PDZ-domain containing adaptor proteins EBP50 and E3KARP32. These interactions may serve not only to link the receptors to the cortical cytoskeleton in a regulated fashion, but also to assemble signalling complexes, that in turn, may regulate receptor trafficking and co-receptor functions. Although functionally disparate, many ERM-associated receptors are co-expressed and may be co-ordinately regulated by ERMs.

Well-studied examples of interactions with membrane proteins include the association of ERM with the positively charged juxtamembrane regions of transmembrane proteins such as CD44 or CD43, and with membrane receptors such as NHE3 or CFTR that associate with EBP50 through a C-terminal PDZ-binding domain. Association with ERMs is thought to promote the activation of CD44 co-receptors such as c-Met62, and regulated association of CD43 with ERMs is important for immunological synapse formation as described below. Furthermore, interaction with ERMs is necessary for apical EBP50 localization in the mouse intestinal epithelium, and therefore likely for the localization and/or function of associated receptors such as NHE3 or CTFR2. Indeed, many studies support a role for ezrin binding in the regulation and/or trafficking of NHE3 and CFTR, through the assembly of higher-order membrane complexes63.

Although the primary focus of many studies of ERM function in cell signalling has been as targets or effectors of signalling mechanisms that organize the apical domain of the cell, there is a growing body of evidence that ERMs function as upstream regulators of signalling mechanisms in epithelia and other tissues. Through their ability to interact with different transmembrane and membrane-associated partners, ERMs have the potential to bring cytoskeletal regulatory proteins in close apposition to the actin cytoskeleton, or receptors together with downstream signalling components. This underexplored area of ERM research will likely result in many exciting discoveries in the future.

ERM functions in development and differentiation

A key prediction from biochemical studies over the past 20 years is that ERMs function to organize both the plasma membrane and the cortical cytoskeleton. However, this prediction has only recently been tested in tissues using model systems in which ERM genetic mutations could be studied. The existence of a single ERM orthologue D. melanogaster and C. elegans eliminates questions of redundancy that surround mammalian studies, and gene knockout studies in mice have both supported the concept of redundancy and provided intriguing hints of functional diversity among mammalian ERMs (BOX 1). Recent genetic studies in D. melanogaster, C. elegans and mice have revealed a wide range of ERM functions, only some of which were predicted from earlier biochemical studies and the models generated from them (discussed below).

Oocyte polarity

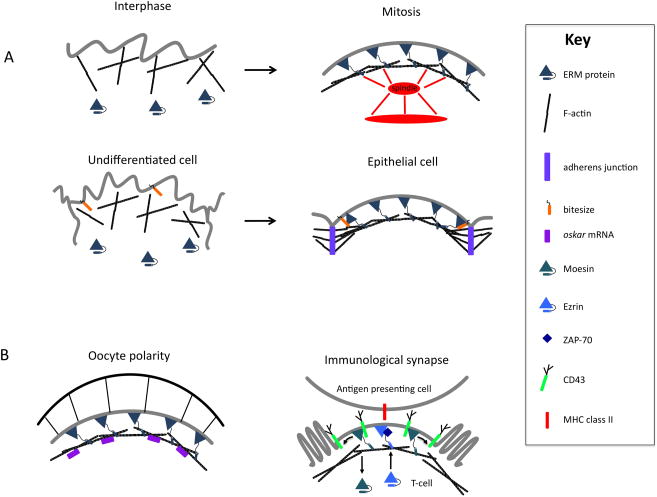

The ability to asymmetrically orient and localize the cytoskeleton is known to be essential to stable maintenance of cell polarity. Although ERMs organize the cortical cytoskeleton asymmetrically and thereby promote ADHERENS JUNCTION stability and epithelial integrity, they do not seem to be directly involved in establishing apical–basal polarity in epithelial cells. However, partial depletion of Moesin from the D. melanogaster oocyte can result in severe anterior–posterior polarity defects owing to mislocalization of ‘posterior group’ gene products, including oskar mRNA and Staufen (Fig. 3B)25, 64. Localization of oskar mRNA by Staufen is known to require interaction with the cortical actin cytoskeleton65, which is disrupted in Moesin-depleted oocytes25, 64. Interestingly, Moesin appears to stabilize actin filaments uniformly throughout the oocyte cortex, suggesting that other molecules are involved in localizing oskar mRNA and Staufen specifically in the posterior end.

Figure 3. In vivo functions of ERM proteins.

A | Two examples, mitotic cells in culture and differentiating epithelial cells, where ERMs function by binding to and organizing the cortical actin cytoskeleton. In interphase cells, inactive, self-associated ERMs do not stabilize the interface between membrane proteins and the cortical cytoskeleton, yielding randomly oriented actin filaments and low cortical tension. As cell enter mitosis, ERM activation results in linkage of actin filaments to the cell cortex so that they lie parallel to the plasma membrane, increased in cortical tension, an associated rounding of the cell membrane, and proper positioning of the mitotic spindle. In differentiating D. melanogaster epithelial cells, ERM recruitment to the apical membrane by Bitesize, a synaptotagmin-like protein, results in recruitment and stabilization of actin filaments in the apical domain. These filaments in turn stabilize adherens junctions that assemble in the apical junctional region. Although not depicted it is likely that ERMs interact with as-yet-unidentified transmembrane proteins in mitotic cells and in the fly embryonic epithelium. B | Examples where ERMs organize both the actin cytoskeleton and other cortical molecules. In the D. melanogaster oocyte Moesin is necessary for cortical cytoskeleton integrity and cytoskeleton-dependent localization of posterior polarity determinants such as oskar mRNA. As in [A], Moesin likely associates with transmembrane proteins during the establishment of oocyte polarity. In human T cell activation, Moesin, which normally binds and localizes CD43, is transiently inactivated in the region where the T-cell binds to the antigen-presenting cell, leading to microvillar collapse and delocalization of CD43. Simultaneously, Ezrin is activated and recruits ZAP-70, the signalling tyrosine kinase ζ-chain associated protein, to the immunological synapse, where it phosphorylates other components of the T-cell activation pathway.

Mitosis

Cells in culture, and even polarized epithelial cells, undergo cortical retraction and rounding as they enter the early stages of mitosis. Concomitantly, the spindle becomes organized, elongated and properly positioned in the cell. Rounding is accompanied by increased cortical stiffness, loss of stress fibres and uniform accumulation of actin microfilaments around the cell cortex. Previous studies have shown that this process is RhoA dependent, suggesting a role for myosin II and possibly other RhoA effectors. However, the exact mechanisms by which this occurs are unclear66.

Recent studies have shown that Moesin functions in enhancing cortical stiffness to promote cell rounding during mitosis4, 5. In D. melanogaster cultured cells, reduction in Moesin levels using RNA interference results in multiple defects during mitosis, including cell shape abnormalities and delay in anaphase onset. Furthermore, these cells fail to undergo normal cortical retraction and exhibit severe membrane blebbing that is myosin II dependent. Consistent with this phenotype, ERMs are recruited to the plasma membrane during bleb formation in interphase mammalian cells and appear to play a role in bleb retraction67. Measurements using ATOMIC FORCE MICROSCOPY indicate that cortical rigidity fails to increase during mitosis when Moesin is depleted4. This phenotype is suppressed by the expression of the phosphomimetic MoesinT559D allele but not by non-phosphorylatable MoesinT559A. Furthermore, depletion of Slik kinase, which phosphorylates Moesin, resulted in similar phenotypes to Moesin knockdown, suggesting that the activated, phosphorylated form of Moesin is essential for cortical contraction and rigidity that occur during mitosis.

Taken together, these results support a model in which D. melanogaster Moesin, and presumably the mammalian ERMs, promote cortical rigidity by binding to cortical actin filaments so that they lie parallel to the plasma membrane4, 68 (Fig. 3A). This model is elegant, simple and consistent with existing paradigms for ERM function. However, as observed previously in IMAGINAL DISCS6, many phenotypes of Moesin deficiency, including cortical deformation and spindle morphology, can be suppressed by simultaneous depletion of Rho1, even though cortical stiffness should be severely compromised in these cells5. The same study found that both Rho1 and myosin II are mislocalized in Moesin-depleted cells. These results suggest a complex relationship between ERMs and the regulation of cortical stiffness, and that the ability of ERMs to regulate RhoA plays a role in this process.

Epithelial morphogenesis and integrity

Early studies of ezrin indicated that it localizes to the BRUSH BORDER of the intestinal epithelium, strongly suggesting a role in the organization of the actin-rich apical plasma membrane of epithelial cells. Recent studies have significantly expanded our understanding of the mechanistic basis of this function for ERMs.

D. melanogaster embryonic development provides a unique system in which to study epithelial morphogenesis because the entire embryonic epidermis is formed in a simultaneous cleavage event that divides the embryonic SYNCYTIUM into thousands of cells at the cellular blastoderm stage. A genome-wide DNA array study to identify genes expressed specifically at this crucial stage identified a D. melanogaster SYNAPTOTAGMIN orthologue, Bitesize, as being expressed during the time that the blastoderm differentiates into a polarized epithelium69. Bitesize, a cytoplasmic protein, is recruited to the apical membrane domain through interactions with the APICAL POLARITY COMPLEX. In the absence of bitesize function, early aspects of apical–basal polarity, including the formation of adherens junctions, occur normally, but subsequently epithelial organization and the adherens junctions break down.

How does Bitesize stabilize adherens junctions and epithelial architecture? Protein interaction studies identified Moesin as a binding partner for Bitesize 61, and genetic studies confirmed that depletion of Moesin has a similar phenotype69. As Moesin binds F-actin, these results suggest that Bitesize recruits Moesin to the apical domain early during cell polarization, and Moesin, in turn, stabilizes cortical actin. Cortical actin is required for the formation of stable adherens junctions, which are necessary for epithelial integrity and polarity (Fig. 3A).

Moesin also appears to have an important role in other D. melanogaster epithelia at later developmental stages. In the imaginal epithelia, Moesin loss-of-function mutants display a disruption in overall morphology and epithelial integrity6, 57. Mutant cells that ‘fall out’ of the epithelium lack markers for intercellular junctions or apical–basal polarity and appear able to migrate, suggesting they have undergone an EPITHELIAL TO MESENCHYMAL TRANSFORMATION (EMT). Cortical actin underlying the apical membrane is substantially diminished in cells that remain in the epithelium, but surprisingly adherens junctions appear only mildly affected. The EMT-like phenotype does not seem directly related to loss of apical actin, because it is strongly suppressed by reducing Rho1 genetic dosage, even though apical actin is not restored (Neisch and Fehon, unpublished).

Overall, studies in D. melanogaster seem to support a model in which Moesin stabilizes the apical plasma membrane and adherens junctions through its ability to interact with filamentous actin. However, it is not yet clear that this is a general model for ERM function in epithelial morphogenesis. Bitesize function does not appear to be required for the development of imaginal epithelia70, suggesting that its interaction with Moesin is specific to the early stages of epithelial morphogenesis or that it has redundancy with other, currently unknown proteins. Similarly, although some Moesin mutant imaginal epithelial cells lose cell integrity and polarity, many remain integrated into the epithelial layer, suggesting that ERMs are not absolutely required for adherens junction stability in established epithelia.

Lumen morphogenesis

The formation of epithelial structures containing a central lumen that is lined by apical surfaces and sealed off by apical junctions underlies the morphogenesis of vital organs across evolution. Studies in both C. elegans and mice have recently suggested a crucial role for the ERMs in certain types of lumen morphogenesis.

In C. elegans, the single ERM orthologue, erm-1, localizes to the luminal membrane of epithelia that lack a supporting cuticle71, 72. Genetic loss or overexpression of erm-1 led to the appearance of cyst-like structures along the lumen in these epithelia, suggesting a defect in lumen formation. For example, constrictions and occlusions occur along the erm-1-deficient intestine and are accompanied by perturbations in the cortical cytoskeleton, aberrant apical morphology and abnormal positioning of adherens junctions. Coincident loss of either cadherin or catenin, which are components of the apical portion of the C. elegans adherens junction, led to a marked fragmentation of junctional staining. This phenotype was not seen in erm-1-, cadherin-or catenin-deficient animals, suggesting that erm-1 functionally interacts with the apical junctional complex. In contrast, genetic studies did not support a functional interaction between erm-1 and Dlg-1, a component of the basal portion of the adherens junction. The erm-1 phenotype was also enhanced by loss of either actin or the cortical cytoskeletal protein β-H-spectrin, suggesting that erm-1 is important for cortical cytoskeletal integrity71. Intestinal lumen morphogenesis in C. elegans is thought to be accompanied by the migration of adherens junction components from the apical to apico-lateral position yielding a free apical surface73. One group suggested that this process was incomplete in the absence of erm-1 yielding intestinal obstructions caused by aberrant points of adhesion along the gut lumen72, whereas another group suggested that these ‘obstructions’ represented severely ‘twisted’ intestinal segments that arise later during the repositioning of cells around the already formed central lumen71. Either way, these observations suggest that erm-1 has an important function at the apical:junctional interface during lumen morphogenesis.

A strikingly similar role for ezrin has been reported in the mouse intestinal epithelium, where ezrin is the only ERM expressed2. The mammalian intestinal lumen is normally lined with finger like villi that expand the absorptive surface of the gut. Deletion of ezrin yields abnormal fusion of individual villi—a defect that originates during embryonic development when the conversion of a stratified epithelium to a columnar epithelial monolayer drives villus morphogenesis. Central to this conversion is the appearance within the stratified epithelium of poorly-characterized, elongated cell-cell junctions that exhibit an electron dense appearance by transmission electron microscopy; de novo lumina appear at the centre of each junction and expand, always framed by such electron dense junctions. These secondary lumina fuse together and drive the fragmentation of the stratified epithelium as it converts to a monolayer covering each villus. In the absence of Ezrin secondary lumina form but fail to expand completely, leaving incompletely segregated villi. Importantly, properly segregated regions of the villus that display a well-developed BRUSH BORDER do form, but ultrastructural defects in the cytoskeleton-rich apical platform known as the terminal web and its associated junctions and microvilli are evident, consistent with a role for ezrin in stabilizing this structure. The corrugated appearance of the terminal web and rounded nascent villar epithelial surfaces suggests altered tension across the apical surface of the epithelial sheet in the absence of ezrin, which is consistent with recent studies in D. melanogaster implicating Moesin in controlling apical stiffness during tracheal lumen expansion74.

These studies suggest that erm-1 and ezrin are important for maintaining the apical:junctional interface during morphogenetic processes that involve apical expansion or reorganization. Notably, in both the early C. elegans and mouse embryos, erm-1 and Ezrin are localized to the junctional region prior to being repositioned to the apical surface as polarity is established72, 75. This is also true in the developing intestine where junctional concentration of ezrin precedes de novo lumen formation, and in the adult intestine where ezrin concentrates along cell-cell boundaries within the crypt but is apically repositioned as cells differentiate and migrate up the villus axis (I Saotome, AIM, unpublished observations). It is possible that erm-1 and ezrin actually facilitate junctional remodelling along cell-cell boundaries during highly dynamic situations when cells are dividing and actively moving past each other; subsequent apical relocalization might restrict remodelling to the apical-junctional interface.

ERM functions in physiology and disease

Metastasis

During the complex process of metastasis tumour cells invade the surrounding normal tissue, recruit new blood vessels and successfully travel to and colonize distant organs76. Each step involves an intimate physical relationship between the tumour cell and surrounding tissue. Accumulating evidence suggests that ezrin promotes tumour metastasis, though the molecular and cellular basis of this is unclear. Many studies document increased ezrin expression and/or activity specifically in metastatic tumours with human and mouse osteosarcomas and rhabdomyosarcomas being the best-studied examples77. Most but not all of these studies cite a unique role for ezrin and not moesin or radixin.

Recent studies suggest that ezrin is dynamically regulated during different stages of osteosarcoma metastasis78. Ezrin is upregulated early during metastatic progression and then later as established metastases expand, but downregulated during the intervening establishment and survival of metastatic nodules. This suggests a role for ezrin in tumour invasion, initially from the primary tumour and subsequently during metastatic expansion; this is consistent with studies implicating ERMs in junctional remodelling and/or stability, processes known to be defective in tumour invasion79.

Several ezrin-associated transmembrane proteins, such as CD44, podoplanin and podocalyxin, have been implicated independently in tumour metastasis. Some studies of CD44 in tumour invasion suggest that its role is directly related to its function as a receptor for hyaluronic acid, which is often concentrated at the invasive front of tumours and may be important in cancer stem cell-niche interactions80. In addition, CD44 is thought to function as a co-receptor for certain receptor tyrosine kinases such as c-Met, which is known to promote tumour invasion and cell motility; this function has been shown to require its association with ezrin81. Podoplanin and podocalyxin are both transmembrane sialoproteins that are found in the kidney podocyte among other places. Podoplanin is upregulated at the outer edge of tumours and transgenic expression of podoplanin in the RIP-Tag mouse model of pancreatic beta-cell tumourigenesis promotes tumour invasion without EMT82. This is unusual given that EMT is thought to promote tumour invasion by endowing tumour cells with more motile mesenchymal behavior83. On the other hand, podoplanin can promote EMT in Madine-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells in a manner dependent upon its association with ezrin84. Podocalyxin antagonizes cell-cell adhesion and drives the formation of a preapical domain in MDCK cells85. Recent studies suggest that podocalyxin promotes the invasion of breast and prostate tumour cells in an ezrin-dependent manner86.

Association of ezrin with all three transmembrane proteins is thought to mediate regulation (either positive or negative) of RhoA84, 87, 88. RhoA activity, in turn, has been linked both positively and negatively to junctional stability, cell motility and tumour invasion, suggesting that particular thresholds and/or context-dependency dictates the cellular outcome of RhoA activity89. It is striking that the ‘invasive’ behaviour of Moe-deficient imaginal disc epithelial cells is also driven by altered RhoA activity, though in the fly Moesin loss, rather than increased expression, seems to promote EMT like behavior6. Similarly, ERMs have been proposed to have both positive and negative roles in lymphocyte migration58, 90. Genetic studies using mouse models should help to unravel the role of ezrin and its associated proteins in tumour metastasis in vivo.

The immunological synapse – an example of ERM functional diversity

Non-vertebrate animals appear to have only one ERM protein, whereas vertebrates have three (BOX 2). The vertebrate ERMs show considerable tissue specificity, suggesting that evolution has tailored ezrin, radixin and moesin to perform related but distinct functions in different cell types (BOX 1). An interesting example of functional diversity is seen during immunological synapse formation in mammalian white blood cells that express ezrin and moesin, but not radixin91. During immunological synapse formation a peptide presented by an antigen-presenting cell (APC) is recognized by the cognate T-cell to form a tight interaction that forms in seconds and persists for hours. Recognition of the peptide presented by the APC triggers the T-cell receptor, which brings about a number of changes. Unstimulated T-cells appear spherically uniform and covered in microvilli, so to form the synapse, the microvilli have to be locally disassembled at the site of interaction, which is achieved through ERM dephosphorylation92. In addition, bulky glycoproteins (such as CD43) have to be moved away, the T-cell receptor has to be recruited to the site of the synapse, and adhesion molecules have to then hold the two cells together. ERMs have been implicated in all of these processes93–95. Interestingly, a similar array of ERM mediated cytoskeletal rearrangements occurs during infection of lymphocytes by the HIV retrovirus (BOX 3).

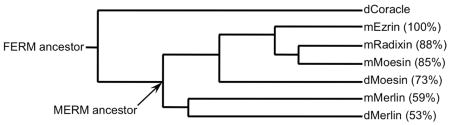

BOX 2. ERM sequence conservation between vertebrates, flies and worms.

ERMs are encoded by three highly homologous genes, being ~85% similar at the amino acid level (amino acid similarity to mouse ezrin provided in the figure). In all non-mammalian genomes sequenced so far, there is only one ERM gene, suggesting that the genes encoding ezrin, radixin and moesin are the result of gene duplication events unique to mammals. In Drosophila melanogaster this single ERM orthologue has been named Moesin because it lacks a polyproline stretch near the C-terminus, as does mammalian moesin (Fig. 1A).

As indicated in the similarity tree, within the FERM domain superfamily, the ERMs clearly form a subgroup together with Merlin, the product of the Neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) gene (D. melanogaster Coracle is provided as a representative protein superfamily member). Recent genomic sequence data from a diverse group of animals suggests that Merlin and ERM arose very early in metazoan evolution from a common ancestral protein (MERM ancestor) because both genes are conserved in groups as diverse as flies, worms, mammals and even choanoflagellates32. If true, then their common origins would suggest that Merlin and the ERMs share similarities both in cellular functions and in mechanisms of regulation.

BOX 3. The role of ERMs in retroviral and bacterial infections.

ERMs have a surprisingly complex role in cells being infected by retroviral or bacterial pathogens. When the human immunodeficiency retrovirus HIV-1 infects lymphocytes, a complex array of cortical rearrangements occur to form what has been termed the ‘virological synapse’107 by analogy to the immunological synapse (see text). At contact, GP120 on the surface of the virus binds CD4 on the lymphocyte cell surface, recruiting this transmembrane protein and an associated protein CXCR4 to the region of contact. At the same time, there is a local activation and accumulation of moesin and ezrin together with filamentous actin, the actin binding protein filamin, and the severing protein cofilin to the synapse. siRNA mediated knockdown of ERMs strongly diminished the ability of HIV-1 to enter and infect cells108, 109 and prevented redistribution of CD4 and CXCR4 into the synapse108. CD4/CXCR4 clustering is known to be dependent on the actin cytoskeleton, suggesting that ERMs facilitate virological synapse formation by anchoring microfilaments.

A related series of events appears to occur in response to bacterial attachment to endothelial cells during infections leading to meningitis. Neisseria meningitides in the bloodstream can attach to endothelial cells and form small colonies. Infected endothelial cells form local membrane protrusions at the site of contact that facilitate bacterial internalization and transcytosis. In response, leukocytes of the immune system adhere to endothelial cells at the site of infection and migrate across the endothelial layer. Stabilization of the initial leukocyte adhesion involves local activation of ERMs, accumulation of actin filaments, and recruitment of adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1110.

A recent study has revealed a fascinating mechanism that infecting bacteria appear to use to circumvent the host’s leukocyte response111. Endothelial cells respond to the adhering bacterial colony somewhat similarly to leukocytes by accumulating transmembrane proteins (ICAM-1, ICAM-2, CD-44, and E-selectin), filamentous actin, and active ERMs. As a result, infected cells are unable to respond properly to leukocytes, apparently because the N. meningitides colony titrates away a limited pool of available ERMs and blocking the formation of a leukocyte docking site.

Two new studies have examined in more detail the roles of ERM in immunological synapse formation, one in human cells and the other in mice96, 97. The relative contributions of ezrin and moesin seem to be slightly different in the two systems. In human cells, moesin and ezrin bind different proteins and have complementary, phosphorylation-regulated roles in formation of the immunological synapse97. Specifically, in unstimulated cells, phosphorylated moesin is enriched and associates with CD43 in the cell cortex, whereas ezrin is largely unphosphorylated and located in the cytoplasm. On stimulation, moesin is rapidly and locally dephosphorylated to collapse the microvilli in the contact area and release CD43. Ezrin binds to, and is needed for, the recruitment of the signalling tyrosine kinase ζ-chain associated protein 70kD (ZAP70), to the synapse, from which moesin and CD43 are excluded (Fig. 3B).

In mice, ezrin and moesin are also found in complementary regions during immunological synapse formation, but this transient state ends with both being localized to the distal pole of the cell96. In contrast to the human system, immunological synapse formation had only modest defects in ezrin knockout cells, with ZAP70 still being correctly localized, whereas depletion of both ezrin and moesin had severe effects. Thus, in the mouse, it appears that ezrin and moesin play both unique and redundant roles in immunological synapse formation.

Conclusion and perspectives

Recent work using genetic approaches has revealed a surprising wealth of phenotypes and functions for ERMs both in the context of normal tissues and in disease states. Such a wide array of phenotypes, from loss of epithelial integrity on one hand to disruption of embryonic anterior–posterior polarity on the other, seems to suggest a wide range of molecular functions. Nonetheless, all available evidence suggests that ERMs function primarily to organize the interface between the actin cytoskeleton and the plasma membrane in a variety of cellular contexts (Fig. 3), so the impressive pleiotropy of ERM mutant phenotypes may simply represent the diverse range of functions of membrane–cytoskeletal interactions in all cells.

There are hints that ERMs may regulate cortical cytoskeletal organization in multiple ways. By far the best documented is the ability of the C-ERMAD to bind filamentous actin, thereby perhaps organizing and bundling filaments parallel to the cell membrane. In addition, there is increasing evidence that ERM may interact with different sets of transmembrane and membrane-associated partners in different cells and subcellular domains (Fig. 3B), thereby bringing cytoskeletal regulatory proteins in close apposition to the actin cytoskeleton. This ability to interact with multiple partners, possibly in a combinatorial fashion, provides the potential for considerable functional diversity. Thus, further elucidation of ERM binding partners, and the contexts in which they interact, will be a key area for future research.

Another important, and still relatively unexplored, area of ERM research is how they are regulated. Although we know that head to tail folding, which is controlled by phospholipid binding and phosphorylation, is important, we know little about the mechanisms upstream of these events. Is membrane phospholipid composition regulated to affect ERM function as suggested by a recent study98? How exactly is ERM phosphorylation controlled, and in what cellular and developmental contexts is this regulated?

As described in BOX 2, within the FERM domain superfamily the ERMs are most closely related to Merlin, the product of the Neurofibromatosis 2 tumour suppressor gene. Merlin is required for proper growth regulation in both mammals and flies, suggesting that its molecular functions are quite well conserved. Although there is clear evidence that ERMs and Merlin are derived from a common evolutionary precursor (BOX 2), we currently have a very poor understanding of their functional relationship (BOX 4). Given the structural similarities between Merlin and the ERMs, it seems likely that they share molecular properties, but genetic analyses performed thus far suggest that their phenotypes are quite different. As our understanding of the molecular functions of all of these proteins grows, it will be interesting to see to what extent their functions are similar, and to what extent Merlin and the ERMs have diverged.

BOX 4. Merlin and its relationship to ERM proteins.

When positional cloning studies revealed that the Neurofibromatosis 2 tumour suppressor gene encodes a protein, Merlin, that is closely related to ERMs, it was initially surprising that a protein believed to mediate membrane-cytoskeletal interactions could function in growth control112, 113. Subsequent studies have suggested that Merlin functions at the plasma membrane, possibly to regulate growth factor receptor availability at the cell surface, a function that is consistent with a protein that regulates membrane-cytoskeletal interactions32. Still, genetic studies indicate that Merlin and the ERMs have quite different functions, despite the fact that Merlin and the ERMs appear to have diverged evolutionarily from a common ancestor and have retained dramatic sequence and structural similarity. Significant aspects of the conformational regulation model are conserved in Merlin, though it appears that the simple closed-inactive, open-active relationship for ERM may not apply to Merlin32. Studies have identified several binding partners that are shared by both proteins, and Merlin and the ERMs both seem to be regulated by a combination of phosphorylation and phospholipid binding.

One model suggests that Merlin and ERMs might function antagonistically, perhaps because ERMs have a well-defined actin-binding domain at the C-terminus, which is not present in Merlin. Indeed, deletion of the actin-binding domain produces a dominant-negative form of ERMs6. However, ERM are ~10X more abundant than Merlin in cells, suggesting that Merlin would be a weak competitive binding partner114. Nonetheless, the overall similarity in structure and common evolutionary origin suggests that the functional differences between Merlin and ERM are the result of different specificities for binding partners rather than fundamentally different modes of molecular action.

Further studies in these areas are likely to reveal even more functions for ERMs and may provide clearer insights into the precise mechanisms by which ERM organize and control specialized membrane domains. Integration of this information into a comprehensive model of regulated ERM-mediated membrane complex formation will, in turn, expand our understanding of many complex biological and disease processes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of our laboratories for their contributions and helpful discussions. We apologize for work that was omitted due to space limitations. Work in our laboratories was supported by grants from the NIH (A.B., R.G.F. and A.I.M.) and the US Army Neurofibromatosis Research Program (A.B. and A.I.M.).

Glossary terms

PDZ DOMAIN

(Postsynaptic-density protein of 95 kDa, Discs large and Zonula occludens-1). A region that is present in several scaffolding proteins and is named after the founding members of this protein family. PDZ domains bind to specific short amino-acid sequences in interacting proteins

HYPOMORPHIC

A mutant allele having a similar but weaker function than the wild-type allele

JUXTAMEMBRANE REGION

A sequence in a transmembrane protein on the cytoplasmic side adjacent to a transmembrane helix

ADHERENS JUNCTION

A cell cell adhesion complex that contains cadherins and catenins that are associated with cytoplasmic actin filaments

APICAL POLARITY COMPLEX

A protein complex consisting of Par-3 (Bazooka), Par-6, and atypical protein kinase C that establishes and maintains the apical membrane in polarized epithelial cells

ATOMIC FORCE MICROSCOPY

A microscope that non-destructively measures the forces (at the atomic level) between a sharp probing tip (which is attached to a cantilever spring) and a sample surface. The microscope images structures at the resolution of individual atoms

IMAGINAL DISC

A single-cell layer epithelial structure of the D. melanogaster larva that gives rise to wings, legs and other appendages

BRUSH BORDER

The highly architecturally and functionally specialized apical domain of intestinal and renal epithelial cells. The brush border is composed of the cytoskeleton-rich terminal web and its associated apical junctions, which form a platform from which a dense array of microvilli project; these microvilli serve to increase the absorptive and resorptive surface areas of the gut and kidney, respectively

SYNCYTIAL EMBRYO

The early stage D. melanogaster embryo in which a rapid series of nuclear replication cycles occur in the absence of cell division, resulting in a single cell with thousands of nuclei

SYNAPTOTAGMINS

A group of Ca2+-binding proteins that are generally understood to be involved with the secretion of granules and vesicles, especially in the nervous system

EPITHELIAL TO MESENCHYMAL TRANSFORMATION

A morphological change characteristic of some developing tissues and certain forms of cancer in which cells lose intercellular junctions and apical-basal polarity, become migratory, and in the case of cancer, become invasive

CADHERIN

A cell-type-specific calcium-dependent transmembrane adhesion protein. Cadherins promote homophilic binding and are preferentially located at adherens junctions

CATENIN

A cytoplasmic protein that is directly or indirectly linked to the cytoplasmic tail of cadherins. In this complex, catenins promote the anchoring of cadherins to actin and junction stabilization

PODOCYTES

Cells in the kidney that have a crucial function in the filtration of solutes in the blood to form urine

IMMUNOLOGICAL SYNAPSE

A large junctional structure that is formed at the cell surface between a T cell that is interacting with an APC; it consists of molecules required for adhesion and signalling. This structure is important in establishing T-cell adhesion and polarity, is influenced by the cytoskeleton, and transduces highly controlled secretory signals, thereby allowing the directed release of cytokines or lytic granules towards the APC or target cell

References

- 1.Lajoie P, Goetz JG, Dennis JW, Nabi IR. Lattices, rafts, and scaffolds: domain regulation of receptor signaling at the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:381–385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saotome I, Curto M, McClatchey AI. Ezrin is essential for epithelial organization and villus morphogenesis in the developing intestine. Dev Cell. 2004;6:855–64. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.05.007. This work provides a detailed phenotypic analysis of epithelial defects in the intestine of mice defficient for ezrin, demonstrating that ezrin plays a crucial role in lumen morphogenesis in the gut. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chorna-Ornan I, et al. Light-regulated interaction of Dmoesin with TRP and TRPL channels is required for maintenance of photoreceptors. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:143–152. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunda P, Pelling AE, Liu T, Baum B. Moesin controls cortical rigidity, cell rounding, and spindle morphogenesis during mitosis. Curr Biol. 2008;18:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carreno S, et al. Moesin and its activating kinase Slik are required for cortical stability and microtubule organization in mitotic cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:739–746. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Speck O, Hughes SC, Noren NK, Kulikauskas RM, Fehon RG. Moesin functions antagonistically to the Rho pathway to maintain epithelial integrity. Nature. 2003;421:83–87. doi: 10.1038/nature01295. This in vivo analysis of Moesin’s role in fly epithelial morphogenesis demonstrates strong functional interactions between Moesin and RhoA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivetic A, Ridley AJ. Ezrin/radixin/moesin proteins and Rho GTPase signalling in leucocytes. Immunology. 2004;112:165–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bretscher A, Edwards K, Fehon RG. ERM proteins and merlin: integrators at the cell cortex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:586–599. doi: 10.1038/nrm882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gautreau A, Louvard D, Arpin M. ERM proteins and NF2 tumor suppressor: the Yin and Yang of cortical actin organization and cell growth signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:104–9. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(01)00300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsukita S, Yonemura S. Cortical actin organization: lessons from ERM (Ezrin/Radixin/Moesin) proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34507–34510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turunen O, Wahlstrom T, Vaheri A. Ezrin has a COOH-terminal actin-binding site that is conserved in the ezrin protein family. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:1445–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.6.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gary R, Bretscher A. Ezrin self-association involves binding of an N-terminal domain to a normally masked C-terminal domain that includes the F-actin binding site. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1061–75. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.8.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura F, Amieva MR, Furthmayr H. Phosphorylation of threonine 558 in the carboxyl-terminal actin-binding domain of moesin by thrombin activation of human platelets. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31377–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yonemura S, Matsui T, Tsukita S. Rho-dependent and -independent activation mechanisms of ezrin/radixin/moesin proteins: an essential role for polyphosphoinositides in vivo. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2569–2580. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.12.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fievet BT, et al. Phosphoinositide binding and phosphorylation act sequentially in the activation mechanism of ezrin. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:653–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belkina NV, Liu Y, Hao JJ, Karasuyama H, Shaw S. LOK is a major ERM kinase in resting lymphocytes and regulates cytoskeletal rearrangement through ERM phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4707–4712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805963106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsui T, et al. Rho-kinase phosphorylates COOH-terminal threonines of ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM) proteins and regulates their head-to-tail association. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:647–57. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng T, et al. Ezrin is a downstream effector of trafficking PKC-integrin complexes involved in the control of cell motility. Embo J. 2001;20:2723–41. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simons PC, Pietromonaco SF, Reczek D, Bretscher A, Elias L. C-terminal threonine phosphorylation activates ERM proteins to link the cell’s cortical lipid bilayer to the cytoskeleton. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253:561–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ten Klooster JP, et al. Mst4 and Ezrin induce brush borders downstream of the Lkb1/Strad/Mo25 polarization complex. Dev Cell. 2009;16:551–62. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCartney BM, Fehon RG. Distinct cellular and subcellular patterns of expression imply distinct functions for the Drosophila homologues of moesin and the neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor, merlin. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:843–852. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.4.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hipfner DR, Keller N, Cohen SM. Slik Sterile-20 kinase regulates Moesin activity to promote epithelial integrity during tissue growth. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2243–2248. doi: 10.1101/gad.303304. This paper shows that the Sterile 20 family kinase Slik is required for D. melanogaster Moesin phosphorylation in vivo, and that loss of this phosphorylation produces a strong Moesin-like phenotype, demonstrating that C-terminal phosphorylation is necessary for ERM function. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes SC, Fehon RG. Phosphorylation and activity of the tumor suppressor Merlin and the ERM protein Moesin are coordinately regulated by the Slik kinase. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:305–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verdier V, et al. Drosophila Rho-kinase (DRok) is required for tissue morphogenesis in diverse compartments of the egg chamber during oogenesis. Dev Biol. 2006;297:417–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polesello C, Delon I, Valenti P, Ferrer P, Payre F. Dmoesin controls actin-based cell shape and polarity during Drosophila melanogaster oogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:782–789. doi: 10.1038/ncb856. This paper, together with Jankovics et al. (ref. 64) describes dramatic polarity defects in D. melanogaster oocytes deficient for Moesin function. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karagiosis SA, Ready DF. Moesin contributes an essential structural role in Drosophila photoreceptor morphogenesis. Development. 2004;131:725–732. doi: 10.1242/dev.00976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chambers DN, Bretscher A. Ezrin mutants affecting dimerization and activation. Biochemistry. 2005;44:3926–3932. doi: 10.1021/bi0480382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang HS, Hinds PW. Increased Ezrin Expression and Activation by CDK5 Coincident with Acquisition of the Senescent Phenotype. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1163–76. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pearson M, Reczek D, Bretscher A, Karplus P. Structure of the ERM protein moesin reveals the FERM domain fold masked by an extended actin binding tail domain. Cell. 2000;101:259–270. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80836-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krieg J, Hunter T. Identification of the two major epidermal growth factor-induced tyrosine phosphorylation sites in the microvillar core protein ezrin. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19258–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dransfield DT, Bradford AJ, Goldenring JR. Distribution of A-kinase anchoring proteins in parietal cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1269:215–20. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(95)00121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McClatchey AI, Fehon RG. Merlin and the ERM proteins--regulators of receptor distribution and signaling at the cell cortex. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yonemura S, et al. Ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM) proteins bind to a positively charged amino acid cluster in the juxta-membrane cytoplasmic domain of CD44, CD43, and ICAM-2. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:885–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinman EJ, Hall RA, Friedman PA, Liu-Chen LY, Shenolikar S. The association of NHERF adaptor proteins with g protein-coupled receptors and receptor tyrosine kinases. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:491–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.131050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lalonde D, Bretscher A. The scaffold protein PDZK1 undergoes a head-to-tail intramolecular association that negatively regulates its interaction with EBP50. Biochemistry. 2009 doi: 10.1021/bi802089k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng H, et al. Autoinhibitory interactions between the PDZ2 and C-terminal domains in the scaffolding protein NHERF1. Structure. 2009;17:660–9. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morales FC, et al. NHERF1/EBP50 head-to-tail intramolecular interaction masks association with PDZ domain ligands. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2527–37. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01372-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith WJ, Nassar N, Bretscher A, Cerione RA, Karplus PA. Structure of the Active N-terminal Domain of Ezrin. CONFORMATIONAL AND MOBILITY CHANGES IDENTIFY KEYSTONE INTERACTIONS. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4949–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamada K, Shimizu T, Matsui T, Tsukita S, Hakoshima T. Structural basis of the membrane-targeting and unmasking mechanisms of the radixin FERM domain. Embo J. 2000;19:4449–62. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edwards SD, Keep NH. The 2.7 A crystal structure of the activated FERM domain of moesin: an analysis of structural changes on activation. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7061–8. doi: 10.1021/bi010419h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takai Y, Kitano K, Terawaki S, Maesaki R, Hakoshima T. Structural basis of PSGL-1 binding to ERM proteins. Genes Cells. 2007;12:1329–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takai Y, Kitano K, Terawaki S, Maesaki R, Hakoshima T. Structural basis of the cytoplasmic tail of adhesion molecule CD43 and its binding to ERM proteins. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:634–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamada K, Shimizu T, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, Hakoshima T. Structural basis of adhesion-molecule recognition by ERM proteins revealed by the crystal structure of the radixin-ICAM-2 complex. Embo J. 2003;22:502–14. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mori T, et al. Structural basis for CD44 recognition by ERM proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29602–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803606200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terawaki S, Kitano K, Hakoshima T. Structural basis for type II membrane protein binding by ERM proteins revealed by the radixin-neutral endopeptidase 24.11 (NEP) complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19854–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609232200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Finnerty CM, et al. The EBP50-moesin interaction involves a binding site regulated by direct masking on the FERM domain. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1547–52. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Terawaki S, Maesaki R, Hakoshima T. Structural basis for NHERF recognition by ERM proteins. Structure. 2006;14:777–89. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jayaraman B, Nicholson LK. Thermodynamic dissection of the Ezrin FERM/CERMAD interface. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12174–89. doi: 10.1021/bi701281e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reczek D, Bretscher A. The carboxyl-terminal region of EBP50 binds to a site in the amino- terminal domain of ezrin that is masked in the dormant molecule. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18452–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Q, et al. Self-masking in an Intact ERM-merlin Protein: An Active Role for the Central alpha-Helical Domain. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:1446–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.075. The first structural determination of a full-length ERM protein, this paper shows how head-to-tail folding results in inactivation of the ERM protein and provides support for a model in which ERMs are activated by sequential unfolding. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mackay DJ, Esch F, Furthmayr H, Hall A. Rho- and rac-dependent assembly of focal adhesion complexes and actin filaments in permeabilized fibroblasts: an essential role for ezrin/radixin/moesin proteins. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:927–938. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.4.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hirao M, et al. Regulation mechanism of ERM (ezrin/radixin/moesin) protein/plasma membrane association: possible involvement of phosphatidylinositol turnover and Rho-dependent signaling pathway. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:37–51. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hatzoglou A, et al. Gem associates with Ezrin and acts via the Rho-GAP protein Gmip to down-regulate the Rho pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1242–1252. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reczek D, Bretscher A. Identification of EPI64, a TBC/rabGAP domain-containing microvillar protein that binds to the first PDZ domain of EBP50 and E3KARP. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:191–206. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hamada K, et al. Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic studies of RhoGDI in complex with the radixin FERM domain. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:889–90. doi: 10.1107/s090744490100556x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.D’Angelo R, et al. Interaction of ezrin with the novel guanine nucleotide exchange factor PLEKHG6 promotes RhoG-dependent apical cytoskeleton rearrangements in epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4780–4793. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-12-1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Molnar C, de Celis JF. Independent roles of Drosophila Moesin in imaginal disc morphogenesis and hedgehog signalling. Mech Dev. 2006;123:337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee JH, et al. Roles of p-ERM and Rho-ROCK signaling in lymphocyte polarity and uropod formation. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:327–337. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takahashi K, et al. Direct interaction of the Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor with ezrin/radixin/moesin initiates the activation of the Rho small G protein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23371–23375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takahashi K, et al. Interaction of radixin with Rho small G protein GDP/GTP exchange protein Dbl. Oncogene. 1998;16:3279–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Formstecher E, et al. Protein interaction mapping: A Drosophila case study. Genome Res. 2005 doi: 10.1101/gr.2659105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Orian-Rousseau V, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor-induced Ras activation requires ERM proteins linked to both CD44v6 and F-actin. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:76–83. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lamprecht G, Seidler U. The emerging role of PDZ adapter proteins for regulation of intestinal ion transport. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G766–777. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00135.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jankovics F, Sinka R, Lukacsovich T, Erdelyi M. MOESIN crosslinks actin and cell membrane in Drosophila oocytes and is required for OSKAR anchoring. Curr Biol. 2002;12:2060–2065. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01256-3. Together with Polesello et al. (ref. 25) this paper demonstrates an essential role for Moesin in D. melanogaster oocyte polarity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Micklem DR, Adams J, Grunert S, St Johnston D. Distinct roles of two conserved Staufen domains in oskar mRNA localization and translation. EMBO J. 2000;19:1366–1377. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maddox AS, Burridge K. RhoA is required for cortical retraction and rigidity during mitotic cell rounding. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:255–265. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Charras GT, Hu CK, Coughlin M, Mitchison TJ. Reassembly of contractile actin cortex in cell blebs. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:477–490. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Neisch A, Fehon RG. FERMing up the plasma membrane. Dev Cell. 2008;14:154–156. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pilot F, Philippe JM, Lemmers C, Lecuit T. Spatial control of actin organization at adherens junctions by a synaptotagmin-like protein Btsz. Nature. 2006;442:580–584. doi: 10.1038/nature04935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Serano J, Rubin GM. The Drosophila synaptotagmin-like protein bitesize is required for growth and has mRNA localization sequences within its open reading frame. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13368–13373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1835727100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gobel V, Barrett PL, Hall DH, Fleming JT. Lumen morphogenesis in C. elegans requires the membrane-cytoskeleton linker erm-1. Dev Cell. 2004;6:865–73. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.05.018. This paper together with Van Furden et al. (ref. 72) demonstrate that in C. elegans ERMs function in luminal morphogenesis in the gut. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Van Furden D, Johnson K, Segbert C, Bossinger O. The C. elegans ezrin-radixin-moesin protein ERM-1 is necessary for apical junction remodelling and tubulogenesis in the intestine. Dev Biol. 2004;272:262–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.05.012. Together with Gobel et al this paper explores ERM function in C. elegans epithelia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bossinger O, Klebes A, Segbert C, Theres C, Knust E. Zonula adherens formation in Caenorhabditis elegans requires dlg-1, the homologue of the Drosophila gene discs large. Dev Biol. 2001;230:29–42. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kerman BE, Cheshire AM, Myat MM, Andrew DJ. Ribbon modulates apical membrane during tube elongation through Crumbs and Moesin. Dev Biol. 2008;320:278–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.05.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Louvet S, Aghion J, Santa-Maria A, Mangeat P, Maro B. Ezrin becomes restricted to outer cells following asymmetrical division in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 1996;177:568–79. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Christofori G. New signals from the invasive front. Nature. 2006;441:444–50. doi: 10.1038/nature04872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]