Structural insights into selective histone H3 recognition by the human Polybromo bromodomain 2 (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2010 Aug 15.

Published in final edited form as: Cell Res. 2010 Apr 6;20(5):529–538. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.43

Abstract

The Polybromo (PB) protein functions as a key component of the human PBAF chromatin remodeling complex in regulation of gene transcription. PB is made up of modular domains including six bromodomains that are known as acetyl-lysine binding domains. However, histone-binding specificity of the bromodomains of PB has remained elusive. In this study, we report biochemical characterization of all six PB bromodomains’ binding to a suite of lysine-acetylated peptides derived from known acetylation sites on human core histones. We demonstrate that bromodomain 2 of PB preferentially recognizes acetylated lysine 14 of histone H3 (H3K14ac), a post-translational mark known for gene transcriptional activation. We further describe the molecular basis of the selective H3K14ac recognition of bromodomain 2 by solving the protein structures in both the free and bound forms using X-ray crystallography and NMR, respectively.

Keywords: NMR, crystallography, bromodomain, chromatin, transcription regulator

Introduction

Histone lysine acetylation plays an important role in control of chromatin-directed gene transcription. Recognition of acetylated histones has been shown to occur through a protein-protein interaction domain, the bromodomain, which is the only known structured domain thus far that recognizes acetylated lysine on histones or transcriptional proteins [1–3]. Bromodomain interactions with lysine-acetylated histones have been shown to aid the recruitment of transcriptional proteins as well as processivity of chromatin remodeling complexes to facilitate gene transcription [4–7]. Polybromo (PB) is a chromatin remodeling protein found in metazoans that regulates gene expression in association with the PBAF remodeling complex during heart development [8, 9], in activation of nuclear hormone receptors [10] and in response to some cancers [11]. PB has a unique domain architecture consisting of a DNA-binding domain, two BAH (bromodomain adjacent homology) domains and six bromodomains [12]. It has been postulated that PB bromodomain-mediated interactions with lysine-acetylated histones are responsible for its unique ability to regulate gene transcription [13, 14]. However, the histone binding selectivity of the PB bromodomains has remained elusive.

We report here our study on the binding of PB bromodomains to a library of lysine-acetylated peptides derived from known acetylation sites in core histones. While each of the PB bromodomains shows varying degree of selectivity to acetylated histone peptides, the second bromodomain (BRD2) of PB shows a distinct preferential binding to lysine 14-acetylated histone 3 (H3K14ac) over all other histone peptides. We characterized the structural basis of H3K14ac recognition by the PB BRD2 by using X-ray crystallography and NMR techniques. The NMR solution structure of the BRD2/H3K14ac complex reveals that the binding specificity for this transcriptional activation mark is established through interactions with the H3 residues flanking the acetyl-lysine 14, including specific recognition of A15 of histone H3 by the BRD2 residues Val269, Leu207 and Glu206.

Results

Histone binding specificity of the PB BRDs

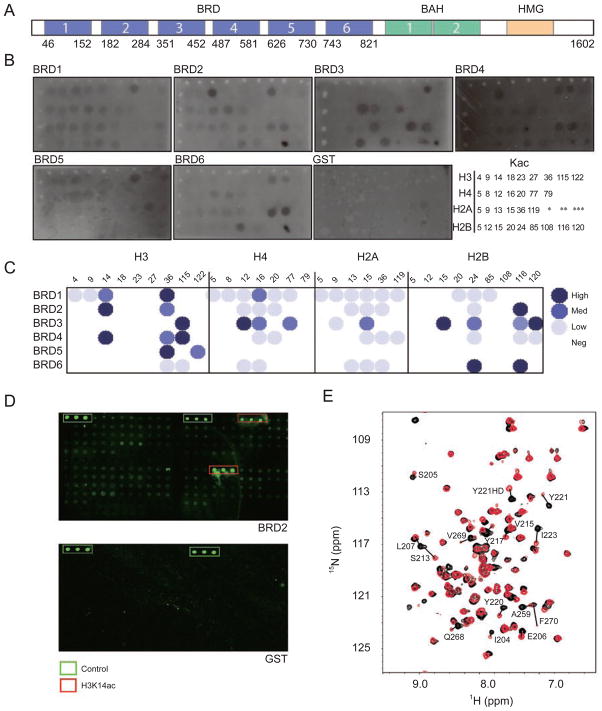

To understand the molecular basis of acetylated histone recognition by the individual bromodomains of human PB, we cloned and purified GST-fusion proteins of all six bromodomains (Figure 1A) and assessed their histone binding using a dot blot assay. Specifically, we spotted a library of N-terminal biotinylated acetyl-lysine (Kac) peptides that are derived from known acetylation sites of the four core histones (Table 1) on a streptavidin membrane and incubated the membrane with individual GST-BRD proteins. In addition, we also included a pair of lysine 50-acetylated and non-acetylated HIV Tat peptides [15] and lysine 382-acetylated p53 peptide [16] on the membrane as reference. The GST-BRDs bound to the membrane-immobilized peptides were visualized by probing with an anti-GST-HRP antibody (Figure 1B). The results reveal that each BRD exhibits a different pattern in binding to the multiple histone acetyl-lysine peptides present on the blot (Figure 1C). For instance, BRD1 binds strongly to H3K36ac, whereas BRD2 specifically prefers H3K14ac over the other histone peptides. BRD3 interacts broadly with H3K115ac, H4K12ac, H2AK15ac and H2BK15ac, and BRD4 binds specifically to H3 at K14ac and K115ac. BRD5 and BRD6 appear to bind to H3K36ac and H3K122ac, and H2BK24ac and H2BK116ac, respectively. Note that some acetylation sites such as H3K36ac and H2BK116ac appear to be recognized commonly by several BRDs of PB. Finally, BRD3, BRD4 and BRD6 also show interactions to the HIV Tat peptides with a small preference for the acetylated form by the latter two, whereas none of the PB BRDs shows any binding to the p53-K382ac peptide.

Figure 1.

Histone binding specificity of the human Polybromo bromodomains. (A) Organization of protein functional units in human Polybromo, consisting of bromodomains (BRD, blue), bromodomain adjacent homology (BAH) domain (green) and high mobility group (HMG) box (yellow). Numerals refer to copies of these conserved protein modules in the protein. (B) Dot blot assay showing GST-fusion BRDs of human Polybromo binding to an array of lysine-acetylated peptides that are derived from known acetylation sites in core histones (shown at low right corner). The binding was detected by western blot analysis using anti-GST antibodies. Peptides marked by single, double and triple asterisks are non-histone peptides derived from HIV Tat-K50, HIV Tat-K50ac and p53-K382ac, respectively. The sequences of the peptides are listed in Table 1. (C) Presentation of quantitative assessment of histone binding data of the Polybromo BRDs in B after normalization of dot blot signal intensity, color-coded in three categories of high, medium and low. (D) Peptide microarray assay using fluorescein-labeled BRD2 showing its selective binding to H3K14ac over other histone peptides. (E) 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled BRD2 (0.25 mM) showing chemical shift perturbations of the protein residues on binding to the H3K14ac peptide (~2.5 mM). Protein NMR signals in the free form and in the presence of the H3K14ac peptide are color-coded in black and red, respectively.

Table 1.

Peptides used on blots and microarrays

| Protein | Acetylation sites | Acetyl-Lys-containing sequences |

|---|---|---|

| H3 (GGSG + aa 1–11) | H3-K4ac | Biotin-GGSGART-Kac-QTARKST |

| H3 (aa 2–16) | H3-K9ac | Biotin-RTKQTAR-Kac-STGGKAP |

| H3 (aa 7–21) | H3-K14ac | Biotin-ARKSTGG-Kac-APRKQLA |

| H3 (aa 11–25) | H3-K18ac | Biotin-TGGKAPR-Kac-QLATKAA |

| H3 (aa 16–30) | H3-K23ac | Biotin-PRKQLAT-Kac-AARKSAP |

| H3 (aa 20–34) | H3-K27ac | Biotin-LATKAAR-Kac-SAPATGG |

| H3 (aa 29–43) | H3-K36ac | Biotin-APATGGV-Kac-KPHRYRP |

| H3 (aa 108–122) | H3-K115ac | Biotin-NLCVIHA-Kac-RVTIMPK |

| H3 (aa 115–129) | H3-K122ac | Biotin-KRVTIMP-Kac-DIQLARK |

| H4 (GGS + aa 1–12) | H4-K5ac | Biotin-GGSSGRG-Kac-GGKGLGK |

| H4 (aa 1–15) | H4-K8ac | Biotin-SGRGKGG-Kac-GLGKGGA |

| H4 (aa 5–19) | H4-K12ac | Biotin-KGGKGLG-Kac-GGAKRHR |

| H4 (aa 9–23) | H4-K16ac | Biotin-GLGKGGA-Kac-RHRKVLR |

| H4 (aa 13–27) | H4-K20ac | Biotin-GGAKRHR-Kac-VLRDNIQ |

| H4 (aa 70–84) | H4-K77ac | Biotin-VTYTEHA-Kac-RKTVTAM |

| H4 (aa 72–86) | H4-K79ac | Biotin-YTEHAKR-Kac-TVTAMDV |

| H2A (GGS + aa 1–12) | H2A-K5ac | Biotin-GGSSGRG-Kac-QGGKARA |

| H2A (aa 2–16) | H2A-K9ac | Biotin-GRGKQGG-Kac-ARAKAKT |

| H2A (aa 6–20) | H2A-K13ac | Biotin-QGGKARA-Kac-AKTRSSR |

| H2A (aa 8–22) | H2A-K15ac | Biotin-GKARAKA-Kac-TRSSRAG |

| H2A (aa 29–43) | H2A-K36ac | Biotin-RVHRLLR-Kac-GNYSERV |

| H2A (aa 112–126) | H2A-K119ac | Biotin-QAVLLPK-Kac-TESHHKA |

| H2B (GGS + aa 1–12) | H2B-K5ac | Biotin-GGSPEPA-Kac-SAPAPKK |

| H2B (aa 5–19) | H2B-K12ac | Biotin-KSAPAPK-Kac-GSKKAVT |

| H2B (aa 8–22) | H2B-K15ac | Biotin-PAPKKGS-Kac-KAVTKAQ |

| H2B (aa 13–27) | H2B-K20ac | Biotin-GSKKAVT-Kac-AQKKVGK |

| H2B (aa 17–31) | H2B-K24ac | Biotin-AVTKAQK-Kac-DGKKRKR |

| H2B (aa 78–92) | H2B-K85ac | Biotin-SRLAHYN-Kac-RSTITSR |

| H2B (aa 101–115) | H2B-K108ac | Biotin-LLPGELA-Kac-HAVSEGT |

| H2B (aa 109–123) | H2B-K116ac | Biotin-KAVSEGT-Kac-AVTIKYT |

| H2B (aa 103–127) | H2B-K120ac | Biotin-GTKAVTI-Kac-YTSSKGS |

| HIV-1 Tat (aa 45–58) | Tat-K50ac | Biotin-GISYGR--Kac-KRRQRRRP |

| HIV-1 Tat (aa 45–58) | Tat-K50 | Biotin-GISYGR--K---KRRQRRRP |

| p53 (aa 375–388) | p53-K382ac | Biotin-GQSTSRH-Kac-KLMFKTE |

To verify the specificity of these histone interactions, we labeled the PB BRD proteins with a fluorescent dye and used them as probes in another binding assay using the same acetylated peptide library. In this peptide array assay, the peptide library was first mechanically spotted in triplicate on a glass slide. Figure 1D illustrates the binding results for green fluorescent labeled BRD2 using GST as a negative control. In the analysis of this assay, the fluorescent intensity at the spots containing an H3K14ac peptide was comparable to the positive control of directly spotted fluorescent molecules. This signal was much higher than all other peptide signals, underscoring the highly specific nature of BRD2/H3K14ac binding. Finally, we confirmed BRD2/H3K14ac binding by using 2 dimensional (2D) 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation (HSQC) NMR spectroscopy. As shown in Figure 1E, the backbone amide NMR resonances of the 15N-labeled BRD2 protein showed chemical shift perturbations in the 2D 15N-HSQC spectra on addition of the H3K14ac peptide, but not of a corresponding non-acetylated H3K14 peptide (data not shown). Taken together, these results establish that H3K14ac, which is an acetylation mark known for gene transcriptional activation, is likely a specific interaction site for PB BRD2.

We next determined the binding affinity of PB BRD2 to the H3K14ac peptide in an NMR titration experiment by plotting protein chemical shift changes in the 2D HSQC spectra as a function of peptide concentration to Kd of ~500 μM. This is a weak interaction but falls in the range of binding affinity previously reported for other BRD/lysine-acetylated peptide interactions such as human BRG1/H3K14ac (Kd of 1 mM) [17] and PCAF BRD/H3K14ac (Kd of 128 μM) [18]. It is noted that several recent papers reported single-digit micromolar affinities for BRD-acetylated histone peptide binding obtained using steady-state fluorescence anisotropy measurements [19, 20]. However, in our hands, we have never been able to obtain an affinity this high, including using a fluorescence polarization assay with a FITC-tagged H3K14ac peptide. In general, we have found that bromodomain binding to lysine-acetylated histone and non-histone peptides is significantly weaker in affinity than lysine-methylated histone binding by the chromodomains [21] or the PHD fingers [22].

3D structures of BRD2 reveal its selective interaction with H3K14ac

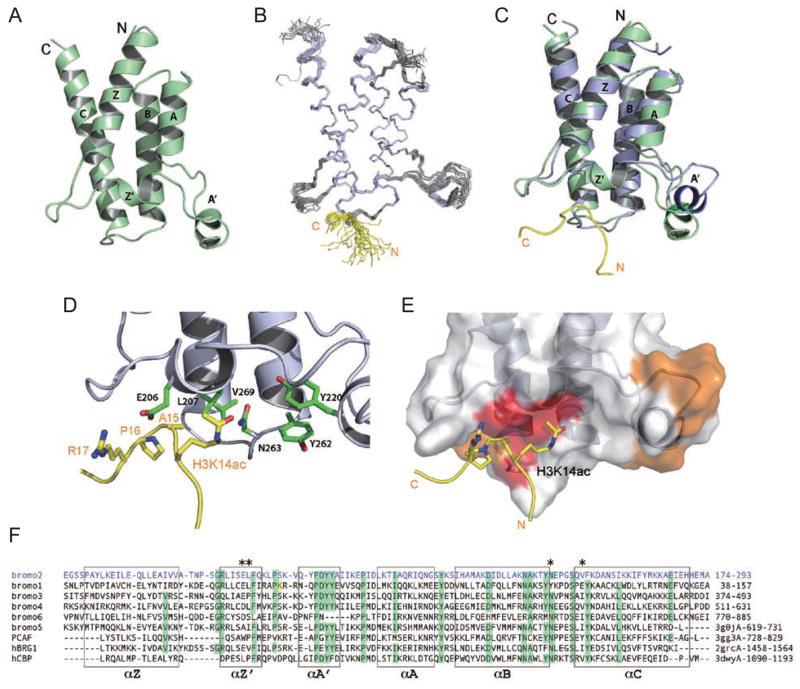

To understand the molecular basis of this selective interaction, we then sought to solve a 3D structure of the BRD2/H3K14ac peptide complex. We co-crystallized BRD2 in the presence of an H3K14ac peptide and collected a full data set with the crystals that reflected to a maximum resolution of 1.5Å. Using the Balbes program [23], we generated an initial molecular replacement structure and refined it to a final _R_work of 0.17 with the Phenix program [24] (see Table 2). The structure shows a left-handed four-helix bundle (Figure 2A), the typical bromodomain fold [25]. Compared to the structures of other bromodomains [3], BRD2 has shortened Z and A helices, but a longer ZA loop that consists of two short one-turn helices A′ and Z′. The peptide, however, did not co-crystallize with the protein. Interestingly, we observed that the carboxylate oxygen of the C-terminal residue Ala from an adjacent BRD2 symmetry molecule in the unit cell forms a hydrogen bond to side-chain amide nitrogen of Asn263 of the BRD2 molecule (data not shown). Given that the highly conserved Asn263 in BRD2 is expected to directly participate in acetyl-lysine recognition by forming a hydrogen bond to the acetyl group (see below), as shown in other BRD structures [3], this crystal packing problem likely prevented us from obtaining co-crystal for the BRD2/H3K14ac peptide complex.

Table 2.

Statistics of the crystal structure of the free PB BRD2

| Data collection statistics1 | |

|---|---|

| Wavelength | 0.978 Å |

| Space group | P31 |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å) | |

| a | 78.96 |

| b | 78.96 |

| c | 50.65 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50-1.5 (1.55-1.50) |

| No. of observed reflections | 177392 |

| No. of unique reflections | 56078 |

| Data completeness (%) | 99.5 (99.9) |

| Redundancy | 3.2 (3.0) |

| _R_sym (%)2 | 7.8 (20.6) |

| I/σ(I) | 31.22 (5.85) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 28.3-1.501 (1.54-1.50) |

| Number of reflections | 53140 |

| _R_factor (%)3 | 17.4 (19.5) |

| _R_free (%) | 19.9 (22.9) |

| Mean overall B-factor (Å2) | 25.97 |

| Number of protein atoms | 1872 |

| Number of water molecules | 716 |

| Heteroatoms | 30.1 |

| R.M.S. bond deviations (Å) | 0.006 |

| R.M.S. angle deviations (degrees) | 0.941 |

| Ramachandran Plot | |

| Most favored region (%) | 99.15 |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 0.85 |

| Generously allowed (%) | 0.0 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.0 |

Figure 2.

Structural insights into selective H3K14ac recognition by BRD2 of human Polybromo. (A) Ribbon representation of a 1.5 Å resolution crystal structure of the BRD2 in the free form. (B) Superimposition of the final 20 NMR structures of the BRD2 bound to H3K14ac peptide. The secondary structural elements are colored in blue and H3 residues K14ac, A15 and P16 of the H3K14ac peptide are shown in orange. (C) Superposition of the crystal structure (green) and the most representative NMR structure (blue) of the BRD2, showing major structural changes of the protein in the ZA loop owing to H3K14ac peptide binding. (D) Acetyl-lysine binding site, showing the key BRD2 residues for H3K14ac recognition, including the conserved Asn263, and Leu205, Glu206, Leu207, Val269, as well as Tyr220 and Tyr262. The former forms hydrogen bond with the acetyl group of H3K14ac, whereas the latter show intermolecular NOEs to the peptide. Note that the conserved Tyr220 is also found to be involved in acetyl-lysine binding in other BRDs. (E) Binding site surface where residues donating NOE are colored in red and residues with HSQC chemical shift colored in blue. (F) Structure-based sequence alignment of BRDs from the human Polybromo and other transcriptional proteins such as PCAF, BRG and CBP and RSC4. Asterisks highlight the residues in the BRD2 of human Polybromo that are involved in H3K14ac interactions, as shown by the NMR structural analysis.

To capture the molecular basis of BRD2/H3K14ac recognition, we collected a full set of heteronuclear multidimensional NMR spectra of the complex and solved the solution structure of BRD2 bound to H3K14ac. The top 20 NMR structures are well defined by the NMR data (Figure 2B; see Table 3). The average minimized NMR structure of BRD2 in complex with the H3K14ac peptide is similar to the crystal structure of the free form but differs in the orientation of the ZA loop, visible in a superimposition of the two structures (Figure 2C). In the NMR structure, the ZA loop is flexed away from the binding site, creating a shallow binding cavity important for peptide binding. In the structures of PCAF BRD bound to HIV-1 Tat-K50ac peptide [15] or CBP BRD bound to p53-K382ac peptide [16], intermolecular NOEs were observed with peptide residues up to Kac ± 3 position, and the Kac binding pocket is formed along the ZA-loop with the A′ helix contributing about half of all protein-to-peptide contacts, notably the conserved tyrosines such as Tyr262 and Tyr220 (Figure 2D), which do not interact with the peptide in our structure. In this BRD2 structure, most of the observed inter-molecular NOEs are between hydrophobic residues Val269 and Leu207 of BRD2 and the side-chain methyl group of A15 and also involve the side chain Cβ, Cγ and Cδ methylene groups of K14ac of the H3 peptide (Figure 2D). Although the residues showed intermolecular NOEs (Figure 2E, red) clustered near A15 and K14ac, there is a wider spread of protein residues that exhibited significant chemical shift perturbations (Figure 2E, orange) indicative of the dynamic BRD/lysine-acetylated peptide interactions. In addition, the acetyl-methyl group of K14ac interacts with Val269, and acetyl amide is within a hydrogen bond distance to the side-chain carbonyl oxygen of the highly conserved Asn263 of BRD2. Moreover, given the close distance observed in the structure, H3R17 and Glu206 may form electrostatic interactions that could further stabilize the complex. We did not observe intermolecular NOEs between the protein residues in the ZA loop and K14ac of the peptide, which could involve electrostatic and/or hydrogen bonding interactions that were not detected in the NOE-based NMR spectra. Collectively, the NMR structural analysis provides new insight into the inter-molecular interactions that likely constitute the selectivity of PB BRD2 binding to H3K14ac.

Table 3.

Statistics of NMR structure of PB BRD2 bound to H3K14ac peptide (PB BRD2/H3K14ac complex)

| NMR distance and dihedral constraints | |

|---|---|

| Distance restraints | 2003 |

| Total NOEs | 1877 |

| Short range (|i – j | ≤ 1) |

| Medium range (1 < |i – j | < 5) |

| Long range (|i – j | ≥ 5) |

| Hydrogen bonds | 106 |

| Inter-molecular constraints | 20 |

| Dihedral angle restraints | |

| Ψ | 84 |

| Φ | 84 |

| Deviations from idealized covalent geometry | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.0077 ± 0.000063 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.85 ± 0.012 |

| Impropers (°) | 2.14 ± 0.087 |

| Ramachandran analysis1 | |

| Most favored (%) | 80.5 (97.5) |

| Additional allowed (%) | 15.5 (2.5) |

| Generously allowed (%) | 2.3 (0.0) |

| Disallowed (%) | 1.6 (0.0) |

| RMSD from average structure | |

| Backbone (N, C, C) atoms (&) | 0.35 ± 0.088 (0.23 ± 0.063) |

| Heavy atoms (&) | 0.72 ± 0.080 (0.66 ± 0.048) |

Histone binding selectivity of the PB BRD2

We further examined the molecular basis of the H3K14ac binding selectivity of BRD2 over the other BRDs of PB based on the new structure. In PB BRD2, H3A15 at the Kac+1 position appears to play an important role in control of the selective H3K14ac recognition by the BRD2, as reflected by a number of intermolecular NOEs that are even more than that with K14ac (Figure 2E, red). The structure-based sequence alignment reveals that the key residues of BRD2 are not all conserved among the PB BRDs (Figure 2F). Specifically, Glu206 in BRD2 is substituted with a shortened side chain Asp in BRD4 and BRD6, and Ala in BRD5; Leu207 is changed to Pro in BRD3 and Ser in BRD6; and Val269 is replaced by Glu in BRD1. Interestingly, the residues corresponding to Glu206 and Leu207 of BRD2 are very different from those in the BRDs of PCAF and CBP (Figure 2F), but similar to those in human BRG1 and RSC4 BRDs. This observation is consistent with the previous report of BRG1 BRD interaction with H3K14ac in gene transcriptional activation [17], and also provides an explanation as to how CBP BRD can recognize a bulky hydrophobic amino acid H4V21 at (Kac+1) position, as shown in the CBP BRD/H4K20ac complex structure [16]. Taken together, these differences of the key amino acid residues at the peptide-binding site collectively account for the selective recognition of H3K14ac by PB BRD2 but not or with reduced affinity by the other BRDs.

Discussion

Since the discovery of bromodomains as acetyl-lysine binding modules, the functional importance of these protein domains in gene transcription has been established [3, 25]. Despite bromodomains’ in vitro low affinities of (10–100 μM) binding to histones [18, 26, 27], they have been shown to be able to guide biological processes by regulating the recruitment and assembly of multi-protein complexes that are important for gene transcription [3, 15, 16]. The modest affinity interaction domains such as bromodomains can work in tandem to create stable binding interfaces in protein complexes. This phenomenon was illustrated with the double bromodomains of BRD4, a bromodomain-ET domain (BET) family protein, which has been shown to be involved in gene transcription elongation during mitosis through cooperative interactions between the tandem bromodomains with acetylated lysines 8 and 12 of histone H4 [28–31]. Interestingly, even at such relatively modest affinity, these domains exhibit distinct preference for binding partners, thus providing positional cues for dynamic and transient protein-protein interactions within multiple protein complexes needed for complex gene transcriptional regulation. As the only multi-bromodomain protein in the PBAF chromatin remodeling complex, PB likely utilizes these characteristic features to coordinate nucleosome structural change at target loci for transcriptional activation [13, 32].

Hyperacetylated histones and nucleosomes have been shown in vitro to be better binding partners for bromodomain proteins [33–37]. Recently, it has been reported that the first bromodomain of the testes-specific BET protein, BRDT, prefers to bind di-acetylated histone 4 containing acetylated lysines 5 and 8 with binding affinity Kd of 21.9 μM, which is at least 10–20 fold higher than the affinity of the same bromodomain binding to individual acetylation sites [38]. The site-specific interaction of BRDT with hyperacetylated histone H4 was shown to play an important role in proper compaction of chromatin during sperm development.

These results argue that the pair-wise bromodomain-acetylation-mark binding model is likely to be supplanted by a more complex combinatorial model. They also support the notion that the PB bromodomains could sense a combinatorial status of acetyl marks on histones, thereby allowing them to work cooperatively with one another to facilitate chromatin remodeling and gene transcription. Although it can be argued that these interactions are too weak to be of functional value, there is precedent for weak protein-protein interactions (Kd ~ 1 mM) to be required for the assembly and bioactivity of multi-component protein complexes [39]. Given that the individual bromodomains are connected to each other in a large protein, it is expected that while each of the six bromodomains exhibits relatively modest affinity to their preferred binding site on histones, they could work cooperatively to facilitate the function of the PBAF remodeling complex, leading to productive gene transcription [32]. It is interesting to note that the yeast ortholog RSC remodeling complex consists of three double bromodomain- containing proteins that possibly make up the collective chromatin remodeling functions by the human PB [14, 40].

Protein modular domains have long been known to serve as functional units in signaling networks that enable proteins to establish molecular interactions for regulatory purposes with other proteins in a sequence-specific and modification-dependent manner [1, 3]. Recent proteomic surveys show that there are a large number of cellular proteins that undergo lysine acetylation, and that lysine acetylation has been implicated in a wide array of cellular processes including chromatin remodeling and gene transcription in the cell nucleus, and likely in cytoplasmic cell signaling [41, 42]. As the only human protein that distinctly consists of more than two acetyl-lysine binding bromodomains, PB is uniquely capable of coordinating multiple transcriptional proteins and histones for control of chromatin structure change and transcriptional activation of specific target genes. In this study, we demonstrate that each of the six PB bromodomains has a different preference in binding to lysine-acetylated histone peptides, and establish that the BRD2 of PB selectively recognizes H3K14ac, an acetylation mark associated with transcriptional activation. Our structural analysis further provides the detailed molecular basis of the sequence-specific recognition of H3K14ac by the PB BRD2. Overall, our findings reported here have important implications for better understanding of the cellular functions that human PB plays in gene transcriptional regulation.

Materials and Methods

Sample preparation

The six bromodomains of human PB (NP_060635.2) consist of residues 46-152, 182-284, 351-452, 487-581, 626-739 and 743-821 that were designed based on domain definitions in the SMART database [43]. The DNA encoding each of the six PB BRDs was cloned from cDNA library (a kind gift of Martin Walsh) into the pGEX-4T1 vector (GE Healthcare) resulting in an N-terminal GST-fusion construct. These recombinant constructs were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells for protein expression. Fusion proteins were purified using a glutathione sepharose Fast Flow column (GE Healthcare) and further purified after thrombin cleavage of the GST tag by Superdex75 size exclusion column. 15N or 15N/13C/2H (90%) labeled proteins for the NMR study were prepared in the M9 minimal media using 15NH4Cl and 12C- or 13C6-D-glucose as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources in H2O or 90% 2H2O.

Peptide array assay

All 31 histone peptides and 3 non-histone peptides, used in the protein/peptide binding study consist of a central acetylated lysine flanked by seven residues on each side and an N-terminal biotin (Table 1). The peptide library was spotted on a streptavidin membrane (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) at 1 mg/ml concentration and 1 μl per spot. The membranes were blocked with BSA and probed with the PB bromodomains. After incubation, the membranes were washed and re-probed with 1:7 500 GST-HRP and exposed using ECL reagent (GE Healthcare). Images were analyzed with ImageJ.22. Spot intensity was measured and normalized to negative controls spotted on the same membranes. Slides were scaled by defining the upper negative value as the mean intensity of the negative controls plus 2 standard deviations. This difference between the upper bound and the maximum pixel intensity on the slide was divided into three intensity bins of equal size, that is, low, medium and high, and visualized using MatrixtoPNG [44]. The peptide microarray was created with histone peptides that were mixed in a ratio of 1:1 in a protein-printing buffer (http://Arrayit.com) and spotted in 100 nl triplicate spots on silicon slides using a GMS Arrayer (Mount Sinai Core Facility). Fusion protein constructs were randomly labeled using AlexaFluor 647 (Succidimydyl ester small volume kit, Molecular Probes). After blocking of the slides, fluorescein-labeled proteins were used as probes for binding with the output measured by fluorescent intensity.

Crystallization

Crystallization was performed at room temperature using sitting drop Intelliplates (Hampton Research). The PB BRD2 protein of 0.7 mM was mixed with H3K14ac peptide (residues 1-20) with a 1:10 protein-to-peptide molar ratio immediately before plating. Lead crystals were optimized in sitting drop Intelli-plates, mixed in a ratio of 1:1 with 1 μl of 35% PEG 4000 solution of pH 5.5 containing 10 mM sodium acetate. After 2 weeks, grown crystals were cryo-protected in 25% glycerol and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data were collected to 1.5Å on the beam-line X4C at Brookhaven National Laboratory in space group P31 with unit cell parameters listed in Table 2.

Crystal structure determination

The crystal structure of the PB BRD2 in the free form was determined with the molecular replacement method. An initial molecular replacement structure was generated using the Balbes server [23] that was used for refinement by the Phenix program [24]. The starting search structure used in the initial Balbes search was the crystal structure of the fifth bromodomain of PB (PDB code 3G0J). The crystal structure was refined to 1.5Å with _R_free value of 0.19 after several iterative cycles of refinement.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR samples contained PB BRD2 of 0.5 mM in complex with an H3K14ac peptide (residues 1-20) (1:5 molar ratio for HSQC spectra and 1:10 molar ratio for 3D NMR data collection) were prepared in the 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5), containing 100 mM NaCl and 1.0 mM DTT in 90% H2O/10% 2H2O. NMR spectra were acquired at 25 °C on a Bruker 800, 600 or 500 MHz spectrometer. 1H, 15N and 13C resonance assignments of the protein were determined with triple resonance NMR spectra [45] collected with 15N/13C- or 15N-labelled protein bound to an unlabeled H3 peptide. 1H resonance assignments of the free H3 peptide were obtained with 2D ROESY and TOCSY spectra. The NOE-derived distance restraints were obtained from 15N- or 13C-edited 3D NOESY data collected using protein/peptide samples in 100% 2H2O. 3_J_HN,Hα coupling constants measured from 3D HNHA data were used to determine φ-angle restraints. Other dihedral angle restraints were predicted from TALOS [46] based on resonance assignments, and hydrogen bond restraints were derived from secondary structure elements as determined by TALOS. Slowly exchanging amide protons were identified from a series of 2D 15N-HSQC spectra recorded after H2O/2H2O buffer exchange. The intermolecular NOEs of the BRD2 bound to the H3 peptide were detected in 13C-edited (F_1_), 13C/15N-filtered (F_3_) 3D NOESY spectra. All NMR spectra were processed by using NMRPipe [47] and analyzed with NMRView [48].

NMR structure calculations

The solution structure of PB BRD2/H3K14ac peptide complex was calculated with a distance geometry-simulated annealing protocol with X-PLOR [49]. Initial structural calculations were performed with manually assigned NOE-derived distance restraints. Hydrogen-bond distance restraints, generated from the H/D exchange data, were added at a later stage of structural calculations for residues with characteristic NOE patterns. The converged structures were used for the iterative automated NOE assignment by ARIA/CNS for refinement [49, 50]. Structural statistics calculated by CNS and PROCHECK-NMR [51] are provided in Table 3.

NMR titration of protein/peptide binding

Affinity of PB BRD2 binding to the H3K14ac peptide was measured by using 2D 1H-15N-HSQC NMR spectra by titrating a stock solution of the H3K14ac peptide into 15N-labeled BRD2 (0.2 mM). Binding affinity was determined by monitoring the changes of chemical shift perturbations of selected protein residues as a function of peptide concentration using the same procedure as reported previously [18].

Structure deposition

The PDB entry codes for the crystal structure of the PB BRD2 in the free form and the solution NMR structure of the BRD2 bound to the H3K14ac peptide are 3LJW and 2KTB, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the use of the NMR facility at the New York Structural Biology Center and the staff at the X6A beamline of the National Synchrotron Light Sources at the Brookhaven National Laboratory for facilitating X-ray data collection. We thank D Lencer and W Shreffler (Mount Sinai School of Medicine) for discussion of peptide microarray, S Chakravarty (Mount Sinai School of Medicine) for discussion on structure-based sequence alignment, and A Plotnikov (Mount Sinai School of Medicine), R Page (Brown University) and V Stojanoff (the Brookhaven National Laboratory) for protein structural analysis using X-ray crystallography techniques. This work was supported by a graduate training program fellowship from the National Cancer Institute (ZC-P) and research grants from the National Institutes of Health (M-MZ).

References

- 1.Seet BT, Dikic I, Zhou MM, Pawson T. Reading protein modifications with interaction domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:473–483. doi: 10.1038/nrm1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taverna SD, Li H, Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Patel DJ. How chromatin-binding modules interpret histone modifications: lessons from professional pocket pickers. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1025–1040. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanchez R, Zhou MM. The role of human bromodomains in chromatin biology and gene transcription. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2009;12:659–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awad S, Hassan AH. The Swi2/Snf2 bromodomain is important for the full binding and remodeling activity of the SWI/SNF complex on H3- and H4-acetylated nucleosomes. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1138:366–375. doi: 10.1196/annals.1414.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeng L, Zhou M. Bromodomain: an acetyl-lysine binding domain. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:124–128. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassan AH, Prochasson P, Neely KE, et al. Function and selectivity of bromodomains in anchoring chromatin-modifying complexes to promoter nucleosomes. Cell. 2002;111:369–379. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandy M, Gutierrez J, Prochasson P, Workman J. SWI/SNF displaces SAGA-acetylated nucleosomes. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1738–1747. doi: 10.1128/EC.00165-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Zhai W, Richardson J, et al. Polybromo protein BAF180 functions in mammalian cardiac chamber maturation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3106–3116. doi: 10.1101/gad.1238104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang X, Gao X, Diaz-Trelles R, Ruiz-Lozano P, Wang Z. Coronary development is regulated by ATP-dependent SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling component BAF180. Dev Biol. 2008;319:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trotter KW, Archer TK. Reconstitution of glucocorticoid receptor-dependent transcription in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3347–3358. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3347-3358.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia W, Nagase S, Montia AG, et al. BAF180 is a critical regulator of p21 induction and a tumor suppressor mutated in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1667–1674. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolas RH, Goodwin GH. Molecular cloning of polybromo, a nuclear protein containing multiple domains including five bromodomains, a truncated HMG-box, and two repeats of a novel domain. Gene. 1996;175:233–240. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)82845-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson M. Polybromo-1: the chromatin targeting subunit of the PBAF complex. Biochimie. 2009;91:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodwin G, Nicolas R. The BAH domain, polybromo and the RSC chromatin remodelling complex. Gene. 2001;268:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mujtaba S, He Y, Zeng L, et al. Structural basis of lysine-acetylated HIV-1 Tat recognition by PCAF bromodomain. Mol Cell. 2002;9:575–586. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mujtaba S, He Y, Zeng L, et al. Structural mechanism of the bromodomain of the coactivator CBP in p53 transcriptional activation. Mol Cell. 2004;13:251–263. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00528-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen W, Xu C, Huang W, et al. Solution structure of human Brg1 bromodomain and its specific binding to acetylated histone tails. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2100–2110. doi: 10.1021/bi0611208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng L, Zhang Q, Gerona-Navarro G, Moshkina N, Zhou M-M. Structural basis of site-specific histone recognition by the bromodomains of human coactivators PCAF and CBP/p300. Structure. 2008;16:643–652. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandrasekaran R, Thompson M. Polybromo-1-bromodomains bind histone H3 at specific acetyl-lysine positions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;355:661–666. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson M, Chandrasekaran R. Thermodynamic analysis of acetylation-dependent Pb1 bromodomain-histone H3 interactions. Anal Biochem. 2008;374:304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein E, Duncan E, Masui O, et al. Mouse polycomb proteins bind differentially to methylated histone H3 and RNA and are enriched in facultative heterochromatin. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2560–2569. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2560-2569.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H, Ilin S, Wang W, et al. Molecular basis for site-specific read-out of histone H3K4me3 by the BPTF PHD finger of NURF. Nature. 2006;442:91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature04802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long F, Vagin AA, Young P, Murshudov GN. BALBES: a molecular-replacement pipeline. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907050172. Available at: http://journals.iucr.org/d/issues/2008/01/00/ba5114/ba5114hdr.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, et al. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58 (Pt 11):1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhalluin C, Carlson J, Zeng L, et al. Structure and ligand of a histone acetyltransferase bromodomain. Nature. 1999;399:491–496. doi: 10.1038/20974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen W, Xu C, Huang W, et al. Solution structure of human Brg1 bromodomain and its specific binding to acetylated histone tails. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2100–2110. doi: 10.1021/bi0611208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y, Wang X, Zhang J, et al. Structural basis and binding properties of the second bromodomain of Brd4 with acetylated histone tails. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6403–6417. doi: 10.1021/bi8001659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dey A, Nishiyama A, Karpova T, McNally J, Ozato K. Brd4 marks select genes on mitotic chromatin and directs postmitotic transcription. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4899–4909. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-05-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin YJ, Umehara T, Inoue M, et al. Solution structure of the extraterminal domain of the bromodomain-containing protein BRD4. Protein Sci. 2008;17:2174–2179. doi: 10.1110/ps.037580.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagashima T, Maruyama T, Furuya M, et al. Histone acetylation and subcellular localization of chromosomal protein BRD4 during mouse oocyte meiosis and mitosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:141–148. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hargreaves DC, Horng T, Medzhitov R. Control of inducible gene expression by signal-dependent transcriptional elongation. Cell. 2009;138:129–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leschziner AE, Lemon B, Tjian R, Nogales E. Structural studies of the human PBAF chromatin-remodeling complex. Structure. 2005;13:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carey M, Li B, Workman J. RSC exploits histone acetylation to abrogate the nucleosomal block to RNA polymerase II elongation. Mol Cell. 2006;24:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasten M, Szerlong H, Erdjument-Bromage H, et al. Tandem bromodomains in the chromatin remodeler RSC recognize acetylated histone H3 Lys14. EMBO J. 2004;23:1348–1359. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vandemark AP, Kasten MM, Ferris E, et al. Autoregulation of the rsc4 tandem bromodomain by gcn5 acetylation. Mol Cell. 2007;27:817–828. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassan A, Neely K, Workman J. Histone acetyltransferase complexes stabilize swi/snf binding to promoter nucleosomes. Cell. 2001;104:817–827. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hassan A, Awad S, Prochasson P. The Swi2/Snf2 bromodomain is required for the displacement of SAGA and the octamer transfer of SAGA-acetylated nucleosomes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18126–18134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moriniere J, Rousseaux S, Steuerwald U, et al. Cooperative binding of two acetylation marks on a histone tail by a single bromodomain. Nature. 2009;461:664–668. doi: 10.1038/nature08397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaynberg J, Fukuda T, Chen K, et al. Structure of an ultra-weak protein-protein complex and its crucial role in regulation of cell morphology and motility. Mol Cell. 2005;17:513–523. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leschziner A, Saha A, Wittmeyer J, et al. Conformational flexibility in the chromatin remodeler RSC observed by electron microscopy and the orthogonal tilt reconstruction method. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4913–4918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700706104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim S, Sprung R, Chen Y, et al. Substrate and functional diversity of lysine acetylation revealed by a proteomics survey. Mol Cell. 2006;23:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choudhary C, Kumar C, Gnad F, et al. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science. 2009;325:834–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. SMART 6: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37 (Database issue):D229–D232. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pavlidis P, Noble W. Matrix2png: a utility for visualizing matrix data. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:295–296. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. Multidimensional heteronuclear nuclear magnetic resonance of proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1994;239:349–363. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)39013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen S, Sandoval J, Swiss VA, et al. Age-dependent epigenetic control of differentiation inhibitors is critical for remyelination efficiency. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1024–1034. doi: 10.1038/nn.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, et al. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson BA. Using NMRView to visualize and analyze the NMR spectra of macromolecules. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;278:313–352. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54 (Pt 5):905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rieping W, Habeck M, Bardiaux B, et al. ARIA2: automated NOE assignment and data integration in NMR structure calculation. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:381–382. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laskowski RA, Rullmann JAC, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: Programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]