LIN-28 and the poly(U) polymerase PUP-2 regulate let-7 microRNA processing in Caenorhabditis elegans (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2010 Nov 19.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009 Aug 27;16(10):1016–1020. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1675

Abstract

The let-7 microRNA (miRNA) is an ultraconserved regulator of stem cell differentiation and developmental timing, and a candidate tumour suppressor. Here we show that LIN-28 and the poly(U) polymerase PUP-2 regulate let-7 processing in C. elegans. We demonstrate that lin-28 is necessary and sufficient to block let-7 activity in vivo; LIN-28 directly binds let-7 pre-miRNA to prevent Dicer processing. Moreover, we have identified a poly(U) polymerase, PUP-2, which regulates the stability of LIN-28 blockaded let-7 pre-miRNA, and contributes to lin-28 dependent regulation of let-7 during development. We show that PUP-2 and LIN-28 interact directly, and that LIN-28 stimulates uridylation of let-7 pre-miRNA by PUP-2 in vitro. Our results demonstrate that LIN-28 and let-7 form an ancient regulatory switch, conserved from nematodes to humans, and provide insight into the mechanism of LIN-28 action in vivo. Uridylation by a PUP-2 orthologue might regulate let-7 and additional miRNAs in other species. Given the roles of Lin28 and let-7 in stem cell and cancer biology, we propose such poly(U) polymerases are potential therapeutic targets.

Small RNAs regulate gene expression in many eukaryotes including plants, animals and fungi. miRNAs are endogenous short RNAs that modulate gene expression by blocking translation and/or destabilizing target mRNAs1,2. In animals miRNAs are transcribed as long precursors (pri-miRNAs), which are processed in the nucleus by the RNase III enzyme complex Drosha-Pasha/DGCR8 to form ~80 nt pre-miRNAs, or are derived directly from introns3. pre-miRNAs are exported from the nucleus and processed by the RNase III enzyme Dicer, and incorporated into an Argonaute-containing RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The first identified miRNAs, the products of the C. elegans genes lin-4 and let-7, control cell fates during larval development4. When either lin-4 or let-7 is inactivated, specific epithelial cells fail to differentiate and undergo additional divisions. lin-4 acts during early larval development, regulating lin-14 and lin-28 mRNAs4,5,6,7,8. let-7 acts during late larval development, regulating lin-41, hbl-1, daf-12 and pha-4 mRNAs9,10,11,12. As such, the time of appearance of these miRNAs must be tightly controlled. In C. elegans and other animals the expression of let-7 is developmentally regulated, but the mechanisms underlying this regulation remain unknown13. Post-transcriptional regulation of specific miRNAs has recently been uncovered14. let-7 biogenesis is blocked by Lin28 at either the Drosha15,16 or Dicer17,18 step in mammalian cell culture. Lin28 is a conserved RNA-binding protein, which in mammals controls stem cell lineages and inhibits let-7 miRNA processing in vitro15,16,17,18,19. However, the mechanism and in vivo significance of this activity are unclear.

RESULTS

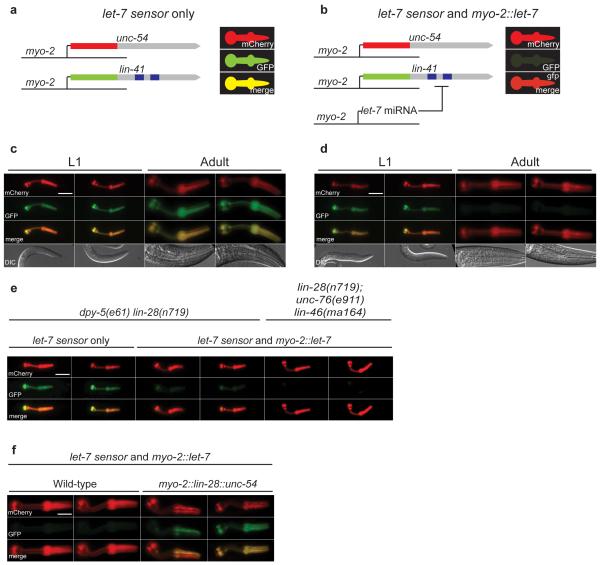

An in vivo assay of let-7 miRNA function reveals developmental regulation

To study the mechanism of miRNA action in vivo, we established a quantitative miRNA reporter assay based on let-7 in C. elegans (Fig 1a,b and Supplementary Methods). We generated two transgenes comprising the promoter of myo-2, the coding sequences of either GFP or mCherry and the 3′UTR of either lin-41 or unc-54 (myo-2::gfp::lin-41 and myo-2::mcherry::unc-54; hereafter referred to as the let-7 sensor; Fig. 1a). The myo-2 promoter confers expression exclusively in the pharyngeal muscle, the food pump of C. elegans20, and lin-41 is a genetically identified target of the let-7 miRNA9, whereas the unc-54 3′UTR is not known to be regulated by any miRNA. Transgenic animals carrying an intrachromosomal array of the let-7 sensor expressed both GFP and mCherry strongly throughout larval development (Fig. 1c). As expected, a transgene expressing let-7 (myo-2::let-7) silenced GFP, but not mCherry (Fig. 1d). Surprisingly, this effect was developmentally regulated; inhibition of GFP is markedly stronger in adults than L1 larvae (Fig. 1d). As the let-7 transgene does not contain the let-7 promoter, this regulation must occur post-transcriptionally. In addition to the qualitative analysis of fluorescent protein expression using microscopy we quantified the activity of the let-7 sensor using flow cytometry of whole animals. We used a COPAS Biosort instrument to quantify GFP and mCherry expression along the body axis of thousands of individual animals at different stages during development. let-7 sensor silencing was least efficient at the L1 larval stage, and reached maximal efficiency during L3 (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1). This correlates with the temporal expression pattern of let-7, which begins to accumulate during the L3 stage21. Since let-7 is being driven by a promoter active at all stages, but appears active only at later larval stages, these data may reflect a mechanism that post-transcriptionally regulates let-7 during development.

Figure 1. A quantitative assay reveals post-transcriptional regulation of the let-7 miRNA by lin-28.

(a,b) Schematic of the pharynx based assay of let-7 activity. (c) Fluorescence images of animals carrying the let-7 sensor transgene at L1 larval and adult stages. Both GFP and mCherry are strongly expressed.

d Fluorescence images of animals carrying both the let-7 sensor and myo-2::let-7 transgenes at L1 larval and adult stages. GFP is specifically and robustly downregulated in adults, but not in L1 larvae. Scale bar shows 20 μm.

e Fluorescence images showing that lin-28 mutants downregulate let-7 sensor GFP at the L1 stage in a myo-2::let-7 dependent fashion. This effect is not reversed in a lin-46 mutant background. Scale bar shows 20 μm.

f Fluorescence images showing that a myo-2::lin-28::unc-54 transgene is sufficient to block let-7 activity in adults carrying let-7 sensor and myo-2::let-7 transgenes. Scale bar shows 20 μm.

LIN-28 regulates pre-let-7 processing

Next we carried out forward genetic and RNAi screens to identify factors regulating let-7 activity in vivo. Knockdown of lin-28 by RNAi resulted in reduced GFP at L1 and L2 stages, in a manner dependent on the myo-2::let-7 transgene (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b and data not shown). We confirmed these results using a lin-28 loss-of-function mutant (Fig. 1e and data not shown). Mutations in lin-46 completely suppress the developmental timing defect of lin-28 mutants22, but do not restore developmental regulation of let-7 (Fig. 1e). Thus deregulation of let-7 activity in lin-28 mutants is not an indirect consequence of developmental timing defects. Other heterochronic genes, including lin-14 and lin-42 did not affect the let-7 sensor (Supplementary Fig. 2c and data not shown). Next we tested if LIN-28 was sufficient to inhibit let-7 activity. Ectopic expression of LIN-28 in the pharynx from an extrachromosomal array resulted in inhibition of let-7 in adults, which do not normally express LIN-288 (Fig. 1f). Mosaic expression of the extrachromosomal array within the pharynx indicated that LIN-28 acts cell autonomously. We concluded that LIN-28 is required and sufficient to inhibit let-7 activity in C. elegans.

We then used miRNA microarrays and northern blotting to confirm that LIN-28 regulates endogenous let-7 accumulation in L2 larvae (Supplementary Data 1; Supplementary Fig. 3)23. Further, expression of other let-7 family members was not increased in lin-28 mutants, whereas three unrelated miRNAs, including the developmentally regulated miRNA miR-85, showed increased expression in lin-28 mutant L2s (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b).

Whether Lin28 regulates let-7 processing at the Drosha15,16 or Dicer17,18 step in mammalian cells is unresolved. We addressed this in vivo in C. elegans. We used northern blotting and qRT-PCR to compare expression of let-7 and its processing intermediates from the myo-2::let-7 transgene in otherwise wild-type and lin-28 mutant L2 larvae. lin-28 mutants expressed higher levels of let-7 compared to wild type, indicating increased processing efficiency; this was accompanied by a slight reduction in the level of pre-let-7, and no change in pri-let-7 levels; these data are consistent with increased efficiency of Dicer-mediated processing (Supplementary Fig. 3c,d). We obtained similar results for endogenous let-7, although levels of pri-let-7 were decreased in lin-28 mutants, suggesting an indirect effect on the let-7 promoter (Supplementary Fig. 3e,f). Interestingly, miR-85 also appears to be regulated at the Dicer step in a _lin-28_-dependent fashion (Supplementary Fig. 3b,g). Consistent with these findings a functional LIN-28-GFP translational fusion is localised in the cytoplasm8 (Supplementary Fig. 4a and data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that LIN-28 blocks Dicer-mediated processing of let-7 and possibly other developmentally regulated miRNAs.

Next, we tested whether LIN-28 directly interacts with pre-let-7. We performed pull-down assays using streptavidin beads and biotinylated pre-let-7. LIN-28-GFP from transgenic worm extracts was retained on streptavidin beads if the synthetic pre-let-7 RNA was biotinylated, but not using a non-biotinylated control (Supplementary Fig. 4b). We tested whether this interaction was direct by native gel mobility shift assay. pre-let-7 and GST-LIN-28 interact with an estimated Kd of 2 _μ_M (Supplementary Fig. 4c and data not shown). We conclude that LIN-28 binds pre-let-7 to prevent Dicer processing. Experiments in mammalian cells suggested that the loop of the pre-let-7 hairpin is required for the interaction with Lin2815,24. However, the pre-let-7 loop is not conserved in C. elegans. We therefore tested a number of pre-let-7 loop mutants in vivo using the let-7 sensor. We found that the pre-let-7 loop is not required for the normal developmental regulation of let-7 activity (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. 5).

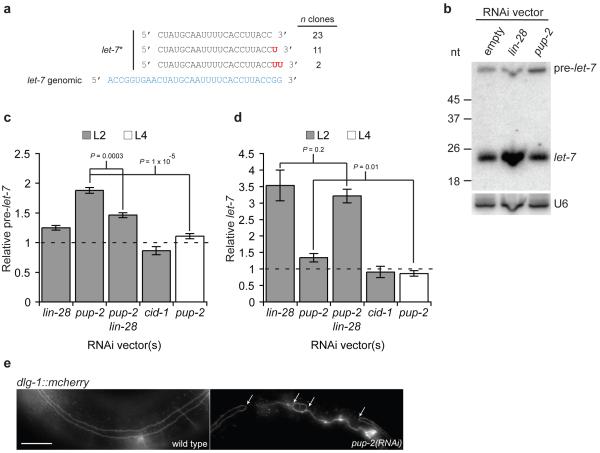

PUP-2 regulates pre-let-7 processing in a lin-28 dependent fashion

Our results so far were consistent with a LIN-28 blockade of pre-let-7 processing, but we were puzzled that pre-let-7 accumulation in L2 larvae differed little in wild-type compared to lin-28 mutant animals (Supplementary Fig. 3). We reasoned that LIN-28 might target pre-let-7 for degradation. Recent work by Kim and colleagues demonstrated that Lin28 promotes pre-let-7 uridylation and subsequent degradation in mammalian cell lines, although the enzyme(s) involved are unknown18. We inspected published high-throughput sequencing data of C. elegans small RNA libraries25,26, and found frequent modification of the 3′ end of let-7* with 1 or 2 untemplated uracil residues (C. elegans let-7 resides on the 5′ arm of the hairpin; Fig. 2a). These species are likely to arise from Dicer processing of partially uridylated intermediates, and indicate in vivo uridylation of let-7. Therefore we carried out an RNAi screen against 15 potential poly(U) polymerases (Supplementary Table 1) assaying let-7 and pre-let-7 abundance in myo-2::let-7 transgenic L2 larvae. RNAi against pup-2 resulted in increased pre-let-7 levels (Fig. 2b,c; P = 7.5 × 10−5), and a small but significant increase in mature let-7 levels (Fig. 2b,d; P = 0.029). This effect is specific to pup-2, no other poly(U) polymerases, including cid-1, a potential paralogue, had this effect27 (Fig. 2c,d). These data suggest that PUP-2 uridylation targets pre-let-7 for degradation, and is required for maximally efficient blockade of let-7 processing by LIN-28. We reasoned that LIN-28 might target uridylation of pre-let-7 by PUP-2, leading to degradation of the uridylated pre-let-7 and turnover of LIN-28/pre-let-7 complexes, ensuring efficient LIN-28 function. We examined the effect of pup-2 RNAi in situations were pre-let-7 is released from LIN-28 bockade. The effect of pup-2 RNAi on pre- and mature let-7 levels is abolished at the L4 stage (Fig. 2c,d P = 1 × 10−5 and P = 0.01 respectively). Further, L2 larvae exposed to both pup-2 and lin-28 RNAi show significantly reduced accumulation of pre-let-7 (Fig. 2c P = 0.0003). These effects are not due to reduced RNAi against pup-2 (Supplementary Fig. 6a). In contrast, the effect of lin-28 RNAi on mature let-7 levels is not altered in lin-28, pup-2 double RNAi L2 larvae (Fig. 2d P = 0.2). From these data we concluded that PUP-2 post-transcriptionally regulates let-7 in a LIN-28-dependent fashion.

Figure 2. pup-2 regulates let-7 processing in a _lin-28_-dependent fashion.

a let-7 is uridylated in vivo. Frequency of unmodified and modified let-7* molecules identified by high-throughput sequencing.

b Representative northern blot showing _pup-2_-dependent regulation of pre-let-7. 5 _μ_g of total RNA from control, lin-28(RNAi), and pup-2(RNAi) myo-2::let-7 L2 larvae was loaded. U6 was used as a loading control.

c,d Quantification of relative pre-let-7 (c), and let-7 (d) abundance in lin-28(RNAi), pup-2(RNAi) and cid-1(RNAi) myo-2::let-7 L2 and L4 larvae from northern blotting experiments. Mean fold change relative to empty vector control samples is shown. _P_-values from Students’ _t_-tests indicated; n = 4. Error bars show standard error of the mean.

e Fluorescence image showing the seam cell defect observed in pup-2(RNAi) adults. A DLG-1-mCherry fusion marks seam cell boundaries. Upper panel; wild-type with continuous seam. Lower panel; pup-2(RNAi) with incompletely fused seam. Arrows indicate sites of failed fusion. Scale bar shows 20 μm.

PUP-2 contributes to LIN-28-dependent regulation of let-7 during development

Next we sought to determine if PUP-2 is required for regulation of let-7 during development. Misregulation of let-7 results in altered timing of larval development, defects in differentiation of a hypodermal stem cell lineage required for the formation of adult-specific lateral alae4, and defects in vulval morphogenesis 21. Lateral seam cells differentiate and fuse into a syncytium in wild-type adults, but this fusion is defective if pup-2 or lin-28 is knocked down, consistent with a role in regulating let-7 (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Table 2). pup-2 RNAi in a lin-28 null mutant background does not increase seam cell fusion defects suggesting this activity of pup-2 is lin-28 dependent (Table 1). Next we tested whether pup-2 genetically interacts with let-7. let-7(_n2853_ts) animals show reduced let-7 expression and temperature sensitive vulval bursting21. At 15°C, vulval bursting of let-7(_n2853_ts) animals was suppressed by pup-2 RNAi, whereas lin-28 RNAi suppressed vulval bursting at both 15°C and 20°C (Table 1). Weaker suppression of let-7(n2853ts) by pup-2 compared to lin-28 is consistent with a role for pup-2 as a lin-28 modifier. Taken together with the effect of pup-2 on let-7 processing, these data indicate pup-2 ensures efficient activity of lin-28 by targeting blockaded pre-let-7 molecules for destruction. This might occur via LIN-28 dependent uridylyl-transferase activity of PUP-2 on pre-let-7; we sought to test this hypothesis in vitro.

Table 1.

Genetic interactions of pup-2 and lin-28 with let-7 in vulval development

| genotype | % burst at 20°C (n) | % burst at 15°C (n) |

|---|---|---|

| let-7(n2853); empty vector RNAi | 97 (119) | 47 (86) |

| let-7(n2853); lin-28(RNAi) | 16 (115) | 0 (28) |

| let-7(n2853); pup-2(RNAi) | 97 (120) | 28 (114) |

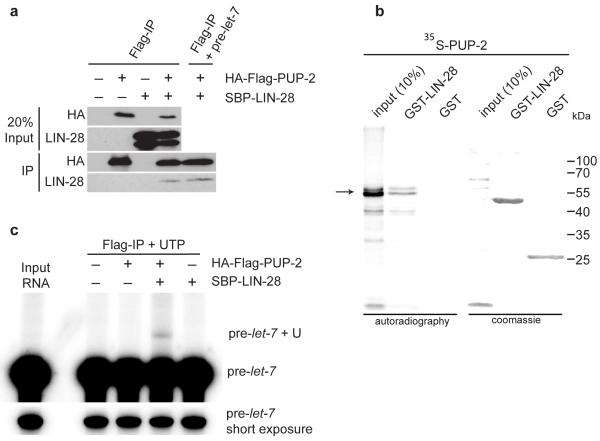

PUP-2 uridylates pre-let-7 in a LIN-28 dependent fashion in vitro

We expressed HA-FLAG tagged PUP-2 and SBP tagged LIN-28 in a HEK293T human embryonic kidney cell line. Immunoprecipitation of HA-FLAG-PUP2 using anti-FLAG antibodies specifically co-precipitated SBP-LIN-28 (Fig. 3a). This interaction was in absence of C. elegans pre-_let_-7 and likely direct. Indeed, the addition of excess exogenous pre-_let_-7 to the cell extract did not enhance the interaction. We also confirmed this interaction in GST pull-down experiments. In vitro translated PUP-2 directly interacts with GST-LIN-28 (Fig. 3b). PUP-2 was previously shown to polyuridylate an artificially tethered RNA in Xenopus oocytes, but was inactive without tethering27. Therefore, we tested if LIN-28 might be able to recruit PUP-2 to mediate pre-let-7 uridylation (Fig. 3c). We incubated anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates from cell extracts expressing HA-FLAG-PUP2 and/or SBP-LIN-28 with radiolabeled pre-let-7 and radiolabelled UTP. We find that HA-FLAG-PUP2 uridylated pre-let-7 only in the presence of SBP-LIN-28 (Fig. 3c). We also confirmed LIN-28 dependent uridylation of pre-let-7 by PUP-2 in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Finally, we attempted to identify in vivo uridylated pre-let-7 directly by cloning, but we were unable to do so. We conclude that rapid degradation of uridylated pre-let-7 prevents accumulation of these species in vivo, as has been postulated in human cell lines18.

Figure 3. LIN-28 interacts with PUP-2 and promotes uridylation of pre-let-7 by PUP-2.

a Co-Immunoprecipitation of PUP-2 and LIN-28 expressed in HEK293T cells.

b GST pull-down assay demonstrating a direct interaction of GST-LIN-28 and PUP-2 in vitro.

c In vitro uridylation assay showing that PUP-2 uridylates pre-let-7 in a LIN-28 dependent fashion.

DISCUSSION

We have developed a quantitative assay of let-7 miRNA function in C. elegans. This assay is highly sensitive and amenable to high-throughput experiments. We have isolated new mutants in known miRNA pathway components through mutagenesis screens using this assay; analysis of novel miRNA function defective mutants should provide insights into the miRNA mechanism. In addition, this assay could be modified to study post-transcriptional regulation or target specificity of other miRNAs.

Here we demonstrate that LIN-28 regulates C. elegans pre-let-7 (see Supplementary Fig. 7a for a model). These results provide a molecular basis for the genetic link between lin-28 and let-7 in controlling developmental timing. In C. elegans this pathway determines the behaviour of epithelial stem cells. In mammals let-7 and Lin28 might regulate primordial germ cell differentiation and other stem cell lineages28. Therefore, the specific interaction of a structured RNA (pre-let-7) with a protein (Lin28) constitutes an ultraconserved switch regulating stem cell differentiation. The let-7/lin-28 switch might be as conserved as let-7 itself. For example, pre-let-7 processing is developmentally regulated in the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus13, which also expresses a Lin28 orthologue (data not shown).

Our finding that the terminal loop of pre-let-7 is dispensable for regulation by LIN-28 is at odds with two previous studies15,16, but is consistent with competition experiments carried out by Rybak et al.17. Our approach has been to assess let-7 function in vivo, whereas previous work was based on in vitro interaction studies. All 22 nucleotides of mature let-7 are conserved in bilateria, whereas for many other miRNAs only the “seed” sequence (nucleotides 2 to 8) appears to be under evolutionary constraint. In contrast, there is little sequence similarity in the terminal loops of let-7 in different species. It is therefore tempting to speculate that nucleotides corresponding to mature let-7 contribute to LIN-28 recognition. Similar RNA-protein interactions might impose evolutionary constraint on the sequences of other ultraconserved miRNAs.

Here we show that LIN-28 recruits the poly(U) polymerase PUP-2 to uridylate C. elegans pre-let-7. We speculate that mammalian PUP-2 orthologues might similarly regulate let-7 in stem cells (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Indeed, the mouse Tut4/Zcchc11 uridylyl transferase regulates let-7 in embryonic stem cells29. let-7 is a candidate tumour suppressor21,30,31,32 and LIN28 is a potential proto-oncoprotein28,33. Therefore TUT4/ZCCHC11 might be an important novel target for anti-cancer therapy. Our data suggest that miRNAs are regulated through pre-miRNA sequestration and uridylation-dependent pre-miRNA degradation. This situation appears to be analogous to two-step regulation of the activity of proteins through sequestration and targeted degradation, for example in the case of cadherin34. Uridylation-dependent degradation of RNA has been observed previously and U tails have been shown to recruit either 5′ to 3′ or 3′ to 5′ exonucleases35,36. High-throughput sequencing suggests additional miRNAs and/or pre-miRNAs are subject to uridylation (data not shown), so regulation in this way may be widespread. Further uncovering the mechanisms underlying this pathway will be of great interest.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information This information is provided as a collated PDF file including Supplementary Tables and Figures, and a 2 separate XLS data files.

1

2

3

Acknowledgements

We thank Andrea Hutterer (Wellcome Trust Cancer Research UK Gurdon Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK) for a strain carrying the mjIs15 transgene, Mark Jackman (Wellcome Trust Cancer Research UK Gurdon Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK) for pDEST-MAL, pcDNA5/FRT/TO_GATEWAY_TEV_SBP and pDEST-3FLAG 3HA vectors, Eric Moss (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, NJ) for anti-LIN-28 antibody, and Marv Wickens (Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin, MA) for PUP-2 cDNA. We thank Richard Gregory and Narry Kim for sharing unpublished data. N.J.L. and K.J.M. were supported by a PhD studentship from the Wellcome Trust (UK). J.A. and A.B. were supported by grants from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (UK). H.L.L. was supported by a PhD studentship from Cancer Research UK. This work was supported by a Cancer Research UK Programme Grants to E.A.M. and S.B. and core funding to the Wellcome Trust/Cancer Research UK Gurdon Institute provided by the Wellcome Trust and Cancer Research UK.

Appendix

Online Methods

Nematode culture and strains

We grew C. elegans under standard conditions at 20 °C37. The food source used was E. coli strain HB101 (Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, MN, USA). We used bleaching followed by starvation-induced L1 arrest to generate synchronized cultures. The wild-type strain was var. Bristol N238. Additional strains used are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

DNA constructs and transgenics

We generated DNA vectors using the Multisite Gateway Three-Fragment vector construction kit (Invitrogen; Supplementary Data 2). We performed site directed mutagenesis using PCR and mutagenic primers (Supplementary Data 2). All constructs were confirmed by sequencing. To generate transgenic animals, we performed germline transformations as described39. Injection mixes contained 2-10 ng μl−1 of vector, 5-10 ng μl−1 of marker, and Invitrogen 1 kb ladder to a final concentration of 100 ng μl−1 DNA (see Supplementary Methods for details). We integrated array transgenes via X-ray irradiation as described40. We generated single copy transgenes by transposase mediated integration (mosSCI) as described41.

Microscopy

We carried out differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence imaging using standard methods42 and using an AxioImager A1 upright microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). We captured images using an ORCA-ER digital camera (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu, Japan) and processed images using OpenLabs 4.0 software (Improvision, Coventry, UK). For analysis of let-7 sensor transgene expression, we imaged all animals under identical conditions. We performed confocal microscopy using an Olympus FluoView FV1000 upright microscope using 63x objective magnification.

Analyses with the COPAS Biosort instrument

We used a COPAS Biosort instrument (Union Biometrica, Holliston, MA, USA) to simultaneously measure length (time of flight), absorbance (extinction), and fluorescence. We optimized fluorophore detection for simultaneous detection of GFP and mCherry. We used a multiline solid state argon laser for excitation (488nm GFP and 561nm mCherry), and detected emission by appropriate PMTs after passing through band pass filters (510/23nm GFP and 615/45nm mCherry). We harvested animals from plates and washed in M9 buffer37 prior to sorting. We determined length and absorbance for each larval stage using synchronised wild-type populations. We then generated gates to isolate animals of specific developmental stages from mixed populations (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

RNA interference assays

We obtained RNAi clones from genome-wide RNAi libraries43,44,45. We generated additional RNAi constructs by subcloning of an appropriate genomic DNA fragment into pDEST-L444045,46 (Supplementary Data 2). We confirmed all RNAi constructs by sequencing. For experiments using let-7 sensor and myo-2::let-7 transgenes we performed RNAi by feeding as described using the eri-1(mg366) RNAi hypersensitive genetic background47. For COPAS Biosort analysis, we plated 10-50 L1 larvae on 90 mm RNAi plates, and analysed animals once the oldest progeny reached the L3 larval stage. For harvest and RNA extraction we plated ~3,000 L1 larvae per RNAi plate and grew animals to adulthood prior to bleaching. After synchronisation by starvation, we plated the progeny onto fresh RNAi plates and grew to the desired stage before harvesting. We performed RNAi by injection as described48. We analyzed phenotypes on progeny laid 24-48 hrs post-injection.

Phenotypic analysis of seam cell development

We performed RNAi by injection into strains carrying seam cell marker transgenes wIs51 and mjIs15.

Vulval bursting assay

let-7(_n2853_ts) embryos were added to RNAi plates by bleaching gravid adults, and grown at 15 °C. Non-burst adults were then transferred to fresh RNAi plates and temperature-shifted as required. L4 progeny were picked to fresh RNAi plates (15-25 animals per plate), and vulval bursting was scored after 48 hrs.

RNA Extraction

For total RNA isolation we harvested animals from plates by washing with M937. We pelleted and froze animals in liquid nitrogen and dissolved pellets in 10 volumes of Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). We extracted total RNA was from Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

miRNA microrarray analysis

We performed miRNA microarrays using custom DNA oligonucleotide arrays as described previously49,50. Data analysis was as described50. To compare miRNA expression in wild-type and lin-28 mutant L2 larvae we isolated and size selected total RNA from synchronized animals to 18-26 nt using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The small RNA fraction was 3′ end-labelled using T4 RNA ligase (Fermentas UK, York, UK). C. elegans miRNA microarrays were based on miRbase release 8.0 51,52. We performed all experiments in triplicates. For microarray probe information and primary microarray data see Supplementary Data 1.

Northern blotting

We performed northern blotting as described25,53, with the following modifications. We used 5-20 _μ_g total RNA, or small RNA fraction (miRvana, Ambion) isolated from ~200 _μ_g total RNA. For developmental expression profiles (Supplementary Fig. 3a) we carried out 1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl]carbodimide hydrochloride (EDC, Perbio Science, Erembodegem, Belgium) crosslinking reactions for 2 hrs at 60 °C. Otherwise blots were UV-crosslinked. We modified northern hybridisations as follows; membranes were pre-hybridised at 40 °C for 4 hrs in hybridisation buffer (0.36 M Na2HPO4, 0.14 M NaH2PO4, 7% (v/v) SDS and 1 mg of sheared, denatured salmon sperm DNA) and hybridised at 40 °C overnight using 20 pmole of _γ_-32P-ATP-radiolabelled DNA oligonucleotide probes (Supplementary Data 2). After hybridisation, we washed membranes twice with 0.5 xSSC, 0.1 % (v/v) SDS at 40 °C for 10 min and once with 0.1 xSSC, 0.1 % (v/v) SDS at 40 °C for 5min. We detected radioactivity by phosphoimager (GE Healthcare, Amersham, UK). We quantified band intensity using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare).

Real-time RT-PCR

We performed RT-PCR as described25, using the standard curve method. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

pre-let-7 pull-down

For these experiments we generated a strain carrying a rescuing lin-28::gfp translational fusion transgene (mosSCI integrated) in a lin-28(n719) mutant background. We prepared protein extracts from starvation synchronised L1 larvae. We cleared lysates against streptavadin Dynabeads (Invitrogen) for 30 min at 4 °C in PD buffer [18 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.9, 10 % (v/v) glycerol, 40 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 100 _μ_M ZnSO4, 1x Proteinase Inhibitor Cocktail (PIC; Roche)]. Dynabeads were blocked with 15 _μ_g yeast tRNA for 1 h at 4 °C in PD buffer before addition of 100 pmol synthetic 5′ biotinylated pre-let-7 (Microsynth, Balgach, Switzerland) for pull-down, or unmodified synthetic pre-let-7 for control reactions, and incubated for 1 hr at room temperature. We added pre-blocked Dynabeads to the binding reaction and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. We washed beads 3 times in PD buffer. We analyzed bound proteins by western blotting with primary mouse anti-GFP (Clontech JL-8; 1:1000) and secondary HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (Dakocytomation P0450; 1:10,000), or rat anti-tubulin (Chemicon international MAB1684, 1:1000) and secondary HRP-conjugated mouse anti-rat (GE Healthcare NA9310; 1:10,000).

Recombinant protein expression

We obtained LIN-28 cDNA (F02E9.2b) from the ORFeome library45. We subcloned cDNAs into pDEST-GEX-2TK (Gateway cassette inserted at SmaI site in pGEX-2TK), or pDEST-MAL. We expressed and purified recombinant proteins as described25,54.

GST-pull-down

We used PUP-2 cDNA in pDEST14 (Invitrogen) to produce 35S-methionine-radiolabelled protein by in vitro transcription-translation using a TNT T7 coupled reticulocyte lysate kit (Promega). We performed pull-downs were performed using GST-LIN-28 as described54.

Pre-let-7 transcription

We performed in vitro transcription reactions in a volume of 20 _μ_l with 0.5 mM of each NTP, 40 mM Tris pH 7.9, 12 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine, 20 mM DTT, 1 mM NaCl, 100 U T7 RNA polymerase (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and 1U RNasin (Promega, Madison WI, USA). We incubated reactions for 1 hr at 37 °C, prior to phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. We transcribed radiolabeled RNA for electrophoretic mobility shift assays with _α_-32P-UTP to a specific activity of approximately 6,000 cpm/fmol.

Immunoprecipitation

We cloned LIN-28 cDNA into pcDNA5/FRT/TO_GATEWAY_TEV_SBP. We cloned PUP-2 cDNA into pDEST-3FLAG 3HA. We performed immunoprcipitation assays as described previously18. Briefly, we transfected HEK293T cells with pHA-FLAG-PUP-2 and/or pLIN-28-SBP. After 48h we collected cells in cold lysis buffer (500mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 10 mMTris (pH8.0), 1% (v/v) Triton X-100), sonicated for 4 min on ice and centrifugated for 10 min. We incubated 50 _μ_l of the supernatant was with 5 _μ_l of pre-washed anti-FLAG antibody, conjugated to agarose beads (Sigma) and incubated for 2 hr at 4°C. We washed agarose-beads twice with lysis buffer and twice with buffer D. For in vitro uridylation, we incubated agarose beads in a 30 _μ_l reaction containing 3.2 mM of MgCl2, 1 mM of DTT and 0.25 mM of rUTP and 5′-end-labeled pre-miRNA of 1 × 104-1 × 105 cpm, for 20 min at 37 °C. We purified RNA by Trizol extraction and isopropanol precipitation. We analyzed reactions in a 12% urea polyacrylamide gel.

In vitro uridylation assays

We performed in vitro uridylation assays in 30 _μ_l reactions containing 1.5 _μ_g of in vitro transcribed pre-let-7 in 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 30 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM MnCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM UTP, 1 _μ_l of RNaseOut and 0.01 Mbq _α_-32P-UTP. We added 1 _μ_g of recombinant MBP-PUP-2 and increasing amounts of recombinant GST-LIN-28 to a maximum of 10 _μ_g. We incubated reaction mixtures at 30 °C for 30 min. We purified RNA by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. We analyzed reactions in a 6% urea polyacrylamide gel. We used 2U of S. pombe CID1 poly(U) polymerase (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) as a positive control. We detected radioactivity by phosphoimager (GE Healthcare).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

We carried out binding reactions in a total volume of 20 _μ_l containing 50,000 cpm of radiolabelled RNA, 30 _μ_g tRNA, 1 _μ_l RNaseOut (40 unit/_μ_l, Invitrogen), 50 mM Tris pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 0.07 % (v/v) _β_-mercaptoethanol, 5 mM MgOAc2, and increasing amounts of recombinant GST-LIN-28 to a maximum of 10 _μ_M. We incubated the reactions at room temperature for 45 min, followed by analysis using 5% native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. We detected radioactivity by phosphoimager (GE Healthcare).

References

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim VN, Han J, Siomi MC. Biogenesis of small RNAs in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:126–139. doi: 10.1038/nrm2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambros V, Horvitz HR. Heterochronic mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1984;226:409–416. doi: 10.1126/science.6494891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalfie M, Horvitz HR, Sulston JE. Mutations that lead to reiterations in the cell lineages of C. elegans. Cell. 1981;24:59–69. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;75:855–862. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss EG, Lee RC, Ambros V. The cold shock domain protein LIN-28 controls developmental timing in C. elegans and is regulated by the lin-4 RNA. Cell. 1997;88:637–646. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81906-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slack FJ, et al. The lin-41 RBCC gene acts in the C. elegans heterochronic pathway between the let-7 regulatory RNA and the LIN-29 transcription factor. Mol Cell. 2000;5:659–669. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrahante JE, et al. The Caenorhabditis elegans hunchback-like gene lin-57/hbl-1 controls developmental time and is regulated by microRNAs. Dev Cell. 2003;4:625–637. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grosshans H, Johnson T, Reinert KL, Gerstein M, Slack FJ. The temporal patterning microRNA let-7 regulates several transcription factors at the larval to adult transition in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2005;8:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin SY, et al. The C elegans hunchback homolog, hbl-1, controls temporal patterning and is a probable microRNA target. Dev Cell. 2003;4:639–650. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasquinelli AE, et al. Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature. 2000;408:86–89. doi: 10.1038/35040556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winter J, Jung S, Keller S, Gregory RI, Diederichs S. Many roads to maturity: microRNA biogenesis pathways and their regulation. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:228–234. doi: 10.1038/ncb0309-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman MA, Thomson JM, Hammond SM. Lin-28 interaction with the Let-7 precursor loop mediates regulated microRNA processing. RNA. 2008;14:1539–1549. doi: 10.1261/rna.1155108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viswanathan SR, Daley GQ, Gregory RI. Selective blockade of microRNA processing by Lin28. Science. 2008;320:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1154040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rybak A, et al. A feedback loop comprising lin-28 and let-7 controls pre-let-7 maturation during neural stem-cell commitment. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:987–993. doi: 10.1038/ncb1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heo I, et al. Lin28 mediates the terminal uridylation of let-7 precursor MicroRNA. Mol Cell. 2008;32:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller DM, Stockdale FE, Karn J. Immunological identification of the genes encoding the four myosin heavy chain isoforms of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:2305–2309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinhart BJ, et al. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403:901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pepper AS, et al. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-46 affects developmental timing at two larval stages and encodes a relative of the scaffolding protein gephyrin. Development. 2004;131:2049–2059. doi: 10.1242/dev.01098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bracht J, Hunter S, Eachus R, Weeks P, Pasquinelli AE. Trans-splicing and polyadenylation of let-7 microRNA primary transcripts. RNA. 2004;10:1586–1594. doi: 10.1261/rna.7122604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piskounova E, et al. Determinants of microRNA processing inhibition by the developmentally regulated RNA-binding protein Lin28. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21310–21314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das PP, et al. Piwi and piRNAs act upstream of an endogenous siRNA pathway to suppress Tc3 transposon mobility in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Mol Cell. 2008;31:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batista PJ, et al. PRG-1 and 21U-RNAs interact to form the piRNA complex required for fertility in C. elegans. Mol Cell. 2008;31:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwak JE, Wickens M. A family of poly(U) polymerases. RNA. 2007;13:860–867. doi: 10.1261/rna.514007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.West JA, et al. A role for Lin28 in primordial germ-cell development and germ-cell malignancy. Nature. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature08210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gregory RI. Lin28 recruits the TUTase Zcchc11 to inhibit let-7 maturation in embryonic stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson CD, et al. The let-7 microRNA represses cell proliferation pathways in human cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7713–7722. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson SM, et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu F, et al. let-7 regulates self renewal and tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells. Cell. 2007;131:1109–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang TC, et al. Lin-28B transactivation is necessary for Myc-mediated let-7 repression and proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3384–3389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808300106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kowalczyk AP, Reynolds AB. Protecting your tail: regulation of cadherin degradation by p120-catenin. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:522–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mullen TE, Marzluff WF. Degradation of histone mRNA requires oligouridylation followed by decapping and simultaneous degradation of the mRNA both 5′ to 3′ and 3′ to 5′. Genes Dev. 2008;22:50–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.1622708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rissland OS, Norbury CJ. Decapping is preceded by 3′ uridylation in a novel pathway of bulk mRNA turnover. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood W. The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbour Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mello C, Fire A. DNA transformation. Methods Cell Biol. 1995;48:451–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fire A. Integrative transformation of Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 1986;5:2673–2680. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frøkjaer-Jensen C, et al. Single-copy insertion of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1375–1383. doi: 10.1038/ng.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horvitz HR, Sulston JE. Isolation and genetic characterization of cell-lineage mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1980;96:435–454. doi: 10.1093/genetics/96.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fraser AG, et al. Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature. 2000;408:325–330. doi: 10.1038/35042517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamath RS, et al. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003;421:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rual JF, et al. Toward improving Caenorhabditis elegans phenome mapping with an ORFeome-based RNAi library. Genome Res. 2004;14:2162–2168. doi: 10.1101/gr.2505604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Timmons L, Court DL, Fire A. Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene. 2001;263:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kennedy S, Wang D, Ruvkun GA. conserved siRNA-degrading RNase negatively regulates RNA interference in C. elegans. Nature. 2004;427:645–649. doi: 10.1038/nature02302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fire A, et al. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miska EA, et al. Microarray analysis of microRNA expression in the developing mammalian brain. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R68. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-9-r68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wienholds E, et al. MicroRNA expression in zebrafish embryonic development. Science. 2005;309:310–311. doi: 10.1126/science.1114519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Griffiths-Jones S. The microRNA Registry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D109–111. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Griffiths-Jones S, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, Bateman A, Enright AJ. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D140–144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pall GS, Hamilton AJ. Improved northern blot method for enhanced detection of small RNA. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1077–1084. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sapetschnig A, et al. Transcription factor Sp3 is silenced through SUMO modification by PIAS1. EMBO J. 2002;21:5206–5215. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1

2

3