The Alzheimer's Disease Mitochondrial Cascade Hypothesis: Progress and Perspectives (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2015 Aug 1.

Published in final edited form as: Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 Sep 23;1842(8):1219–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.09.010

Abstract

Ten years ago we first proposed the Alzheimer's disease (AD) mitochondrial cascade hypothesis. This hypothesis maintains gene inheritance defines an individual's baseline mitochondrial function; inherited and environmental factors determine rates at which mitochondrial function changes over time; and baseline mitochondrial function and mitochondrial change rates influence AD chronology. Our hypothesis unequivocally states in sporadic, late-onset AD, mitochondrial function affects amyloid precursor protein (APP) expression, APP processing, or beta amyloid (Aβ) accumulation and argues if an amyloid cascade truly exists, mitochondrial function triggers it. We now review the state of the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis, and discuss it in the context of recent AD biomarker studies, diagnostic criteria, and clinical trials. Our hypothesis predicts biomarker changes reflect brain aging, new AD definitions clinically stage brain aging, and removing brain Aβ at any point will marginally impact cognitive trajectories. Our hypothesis, therefore, offers unique perspective into what sporadic, late-onset AD is and how to best treat it.

Keywords: aging, amyloid, brain, dementia, Alzheimer's disease, mitochondria

1. Introduction

As originally defined, Alzheimer's disease (AD) described patients with presenile dementia, extracellular cortical “plaques”, and intraneuronal “tangles” [1, 2]. Subsequent work found plaques contain an amyloid protein, beta amyloid (Aβ), and tangles contain aggregated tau protein [3-5]. Aβ itself is a fragment of a larger protein, the amyloid precursor protein (APP) [6].

In order to establish AD as a bona fide disease, early criteria excluded patients with senile dementia [2, 7]. Due to its commonality, senile dementia was generally considered an age-associated phenomenon, and not a true disease. Because plaques and tangles frequently accompanied senile dementia, though, investigators eventually expanded the definition to also include those with senile dementia, plaques, and tangles [8].

Initially, an arbitrary boundary of 55, 60, or 65 years of age separated the presenile “dementia of the Alzheimer's type” (DAT) cases from the “senile dementia of the Alzheimer's type” (SDAT) cases [9]. From the outset, those with SDAT vastly outnumbered those with DAT.

A small minority of the presenile DAT patients experienced clear-cut autosomal dominant inheritance. Sequence analysis of a candidate gene, the APP gene, in a handful of these familial AD (FAD) kindreds revealed APP mutations [10]. In other families, FAD linkage studies helped identify mutations in two related genes, PSEN1 and PSEN2 [11, 12]. Their products, the presenilin 1 and 2 proteins, contribute to a larger protein complex, the γ secretase complex, which cleaves APP [13].

Largely based on APP mutation data, investigators proposed the “amyloid cascade hypothesis” to explain why and how AD arises [14, 15]. The amyloid cascade hypothesis assumes Aβ causes and drives clinical AD by forming in the brain, disrupting function, triggering other pathologies, and directly or indirectly killing neurons. The recognized role of presenilin proteins in APP processing, as well as Aβ's ability to perturb cell function and viability in experimental systems, bolsters this hypothesis [16]. While the overall principle remains unchanged over two decades, refinements have occurred, most notably in regards to which Aβ configuration mediates the disease. Initial versions claimed plaque Aβ caused AD; current versions claim Aβ oligomers cause AD [17].

The amyloid cascade hypothesis etiologically lumps late-onset AD (LOAD) with FAD, and de-emphasizes potential connections between LOAD and aging [9]. It presumes FAD-based disease models model LOAD. It predicts that because Aβ causes AD, removing Aβ or preventing its formation will arrest or prevent AD.

Meanwhile, clinical efforts to better diagnose, track, and treat AD continue to produce new data and novel datasets. Investigators often interpret their findings, which increasingly utilize new technologies such as in vivo plaque imaging, within the context of the amyloid cascade hypothesis.

To better unify and reconcile clinical and amyloid cascade hypothesis-based perspectives, new AD definitions were recently proposed [18-20]. While many believe this will help us to better understand and treat AD, it is important to recognize this view is not universal and alternative perspectives exist. This review will discuss recent AD biomarker data, diagnostic criteria, and clinical trial results from the perspective of a different AD hypothesis, the “mitochondrial cascade hypothesis” [21-27].

2. The Mitochondrial Cascade Hypothesis: Basis and Overview

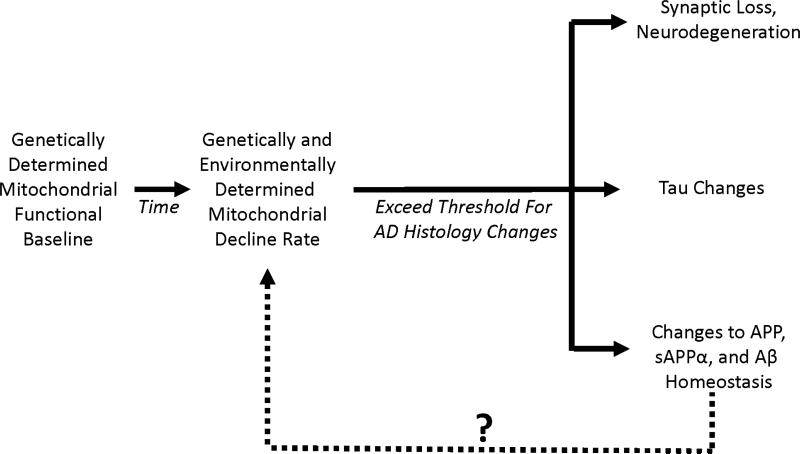

We first proposed the AD mitochondrial cascade hypothesis in 2004 [24]. It consists of three main parts (Figure 1). First, the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis maintains gene inheritance defines an individual's baseline mitochondrial function. In this respect, both mothers and fathers contribute to their offspring's AD risk, but because mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is maternally inherited mothers contribute more.

Figure 1. The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis.

This hypothesis maintains individuals start out with a particular level of mitochondrial function, and that each individual's mitochondrial function declines at a particular rate. Eventually, mitochondrial decline surpasses a threshold and triggers the histologic changes associated with AD. The question mark indicates changes in APP, sAPPα, or Aβ may or may not further influence mitochondrial function. In FAD, if APP, sAPPα, or Aβ homeostasis changes induce mitochondria dysfunction, these changes may end up activating pathways that are also activated in LOAD.

Second, inherited and environmental factors determine the rate at which age-associated mitochondrial changes develop and manifest. If, as data suggest, declining mitochondrial function or efficiency drives aging phenotypes [28-30], then greater mitochondrial durability should associate with slower brain aging and lesser mitochondrial durability should associate with faster brain aging.

Third, an individual's baseline mitochondrial function and functional change rate influences their AD chronology. Those with low baseline function and fast rates of mitochondrial decline will develop symptoms and AD histology changes at younger ages than those with high baseline function and slow rates of mitochondrial decline. Those with less extreme combinations, for example those with low baseline function and slow rates of mitochondrial decline, or with high baseline function and fast rates of mitochondrial decline, will develop symptoms and AD histology changes at intermediate ages.

The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis incorporates, links, and builds upon previously proposed hypotheses and concepts. The idea that mtDNA inheritance, through effects on mitochondrial function, influences AD risk was originally developed by Parker [31, 32]. Several investigators postulated somatic mtDNA mutations, accumulating over a person's lifespan, influence aging [33-35]; Wallace, in particular, championed the idea that somatic mtDNA mutations could cause AD [34]. The proposition that mitochondria drive aging certainly dates back decades [36]. Regarding AD, contributory or even causal roles for specific mitochondrial defects were envisioned by a number of investigators including, but not limited to, Blass, Gibson, Sims, Hoyer, Parker, Beal, Castellani, Smith, and Perry [37-48].

Our hypothesis unequivocally states in sporadic, late-onset AD, mitochondrial function effects APP expression, APP processing, or Aβ accumulation. This possibility had already been suggested by data from other laboratories [21]. By the late 1990's at least three studies reported toxin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction pushes APP processing towards Aβ production [49-51]. Those data, in conjunction with data showing AD subject mitochondrial transfer increases neuroblastoma cell Aβ production (discussed in greater detail in the next section) [52], led us to speculate that even if an amyloid cascade truly exists, mitochondrial function triggers it.

We were further impressed by the fact that mitochondrial dysfunction could potentially produce other AD-associated molecular phenomena, such as increased oxidative stress markers [53, 54]. Additionally, others had already shown mitochondrial dysfunction affects tau phosphorylation [55, 56], and can induce inflammation [57]. For all these reasons, we felt that as far as LOAD was concerned, diverse investigations suggested mitochondria could initiate and drive multiple AD pathologies.

Perceived weaknesses in the amyloid cascade hypothesis also encouraged us to formulate the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis. On an abstract level, the amyloid cascade hypothesis did not address how increased Aβ production or decreased Aβ removal spontaneously arises in LOAD. Either possibility could conceivably occur as a consequence of genetic traits, or develop due to a random, prion-like conformational change, but to date why Aβ dynamics change after many decades of homeostasis remains unanswered.

On a more concrete level, the amyloid cascade hypothesis did not address why particular biochemical defects appear outside the brain, for example in fibroblasts and platelets [21], of AD subjects. Perhaps such changes are directly caused by undetected systemic Aβ production, or perhaps they simply represent indirect consequences of having AD such as medication exposures, dietary changes, or changes in physical activity. To us, though, such explanations appeared unlikely. The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis, therefore, specifically attempted to account for AD's late-life onset, as well as the potentially systemic nature of AD's biochemical changes.

The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis assumes that although LOAD and autosomal dominant FAD might share some important mechanisms, key differences will nevertheless exist. Both LOAD itself and FAD models feature mitochondrial dysfunction [21], so we expect most if not all mechanistic overlap will occur downstream of that step. How mitochondrial dysfunction arises, though, will differ. In LOAD, age-associated changes in mitochondrial function, which mtDNA may mediate, will prove critical. In autosomal dominant AD, changes in APP or its processing will prove critical. To this end, accumulating data certainly do suggest APP and Aβ, as well as the entire γ-secretase complex, physically associate with mitochondria and can effect changes in mitochondrial function [58-67].

One of our goals was to specifically link aging, AD, and AD histology changes. To accomplish this we adopted an already existing mitochondria-centric aging theory [68-70], and extended it to possibly explain how aging might account for AD and AD histology. We felt this was necessary because with advancing age AD prevalence and incidence skyrockets [71-75]. Indeed, among some geriatric demographics more people have AD than don't have it. AD histology changes are found even more frequently [76-78]. In pointing this out we do not claim that everyone, should they live long enough, will develop AD as exceptions to this statement likely occur [79]. Rather, to our view those who survive to very advanced ages without developing AD signs, symptoms, or histology changes are the exceptions, and those who do develop these changes represent the norm.

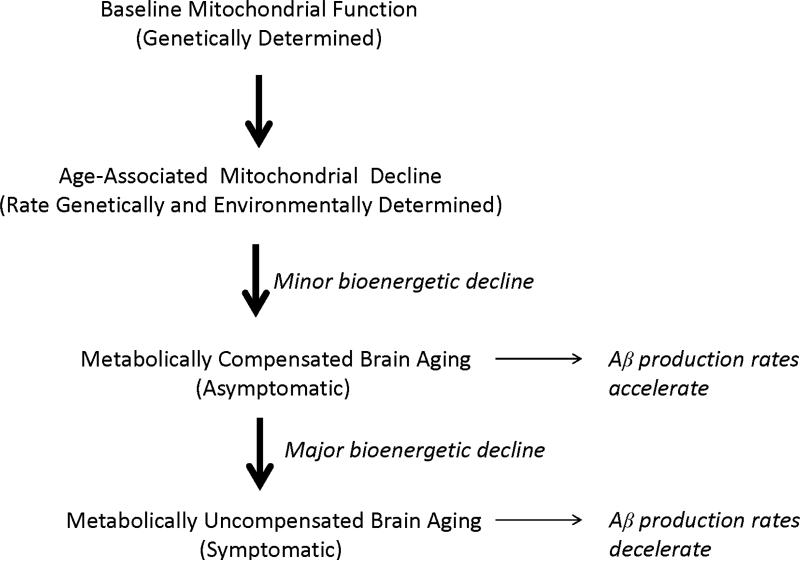

One question that occasionally arises in regards to our hypothesis is whether it classifies AD as a disease, or simply as brain aging. This question perhaps warrants nuanced consideration rather than a categorical answer. Existing data suggest mitochondrial function declines throughout much of adulthood and that adaptive changes, at least initially, mitigate this decline [47, 80-82]. While compensation remains adequate, symptoms do not manifest. With enough decline, however, adequate compensation becomes impossible. Therefore, two types of brain aging likely exist, compensated brain aging and uncompensated brain aging. According to our hypothesis, symptomatic AD coincides temporally with the stage of uncompensated brain aging. Whether uncompensated brain aging represents a disease or a stage of aging, though, doesn't really matter to those experiencing it.

Perhaps more than any other single reason, in developing the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis we were guided by our experience with cytoplasmic hybrid (cybrid) cell lines generated through the transfer of AD subject mitochondria to mtDNA-depleted neuroblastoma and teratocarcinoma cell lines [21]. Below we discuss this cybrid work, as well as other relevant research published since we first proposed the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis.

3. Support for the Hypothesis

In 1990, Parker et al. showed reduced cytochrome oxidase (COX) activity in AD subject platelets [44]. This defect was later demonstrated in AD subject brains [83-86]. As neurodegeneration and brain Aβ could not easily explain reduced platelet COX activities, Parker considered a potential genetic basis for this phenomenon [31, 44]. Because LOAD does not show clear Mendelian inheritance, mtDNA does not follow Mendelian rules, and COX contains mtDNA-encoded subunits, the possibility of an mtDNA contribution seemed particularly attractive. To test this, a cybrid approach was used.

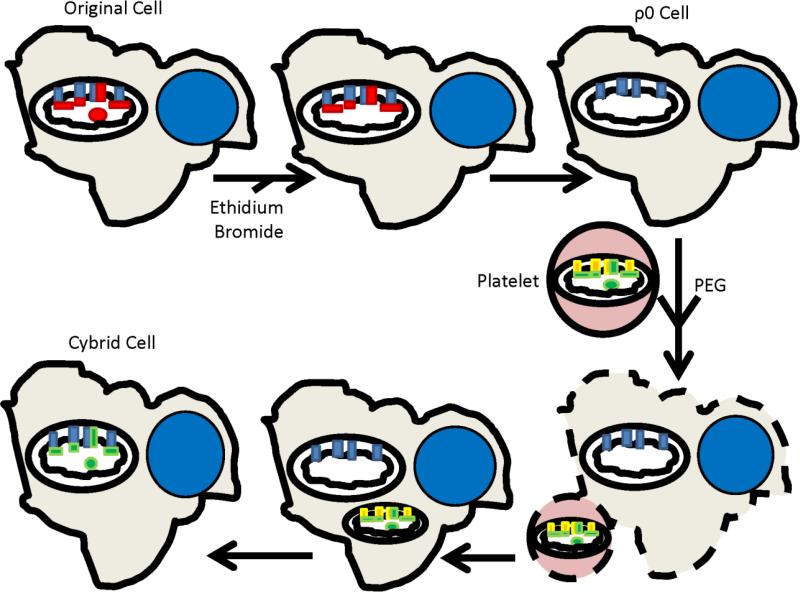

The cybrid technique, developed in the 1970's [87], assesses mtDNA functional correlates. In this technique, one transfers the cytosolic contents of a donor cell, usually a platelet or enucleated cytoplast, to a nucleated host cell [88, 89]. Most transferred components degrade over time or dilute as the host cell divides, except for mtDNA located within donor mitochondria. This exogenous mtDNA replicates, generates respiratory chain subunits, and influences respiratory chain function.

Figure 2 illustrates the general protocol used to generate our cybrid cell lines. We first removed the endogenous mtDNA from two different neuronal lines, the SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma and NT2 teratocarcinoma cell lines. Next, we isolated platelets from subjects with and without AD. Transferring platelet mitochondria to the mtDNA-depleted neuroblastoma and teratocarcinoma lines repleted their mtDNA, and created cybrid lines whose mtDNA derived from an AD or age-matched control subject. Mean COX activity was lower in cybrid lines containing AD subject mtDNA than it was in cybrid lines containing control subject mtDNA [90, 91]. Based on this, we concluded mtDNA at least partly determines low COX activity in AD.

Figure 2. The cybrid technique.

An expandable cell line is treated with enough ethidium bromide to interfere with mtDNA replication, but not enough to prevent nuclear DNA replication. This depletes the cell line's endogenous mtDNA (shown by the absence of the red mtDNA circle within the mitochondrion in the top row), removes its mtDNA-encoded subunits (shown by the absence of the red rectangles within the mitochondrion in the top row), and generates a respiration-incompetent cell called a ρ0 cell. Incubating ρ0 cells with platelets in the presence of polyethylene glycol (PEG) allows platelet and ρ0 cell cytosols to mix. Platelet mitochondria contain mtDNA (shown as a green circle within the mitochondrion in the bottom row), which populates the ρ0 cell mitochondria, generates mtDNA-encoded respiratory chain subunits (shown as green rectangles within the mitochondrion in the bottom row), and restores respiratory competence. The new cybrid cell now contains mtDNA from the platelet donor, mtDNA-encoded respiratory chain subunits that match those of the platelet donor, its original nuclear DNA, and its original nuclear-encoded respiratory chain subunits.

The cybrid lines containing AD subject mtDNA, the “AD cybrids”, differed from the control subject-generated “control cybrids” in other ways; results from 18 different AD cybrid studies were recently summarized elsewhere [21]. AD cybrid mitochondrial were relatively depolarized, smaller on average, and less able to buffer calcium. AD cybrids showed decreased ATP and increased oxidative stress, stress signaling, and apoptosis. Interestingly, AD cybrid Aβ levels also increased.

More recently, cybrid approaches revealed mitochondrial deficiencies in subjects with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [92, 93]. Clinically, MCI subjects exhibit objective cognitive deficits or decline, may struggle to complete previously routine activities, but essentially retain independent function [94-96]. Most progress and are subsequently diagnosed with AD, so in many MCI arguably represents very early AD [97]. Two studies in which “MCI cybrid” lines were generated through transfer of MCI platelet mitochondria to mtDNA-depleted cells observed low mean COX activity and other downstream molecular changes [92, 93]. This suggests that compared to cognitively intact individuals, individuals in the earliest clinically detectable stage of AD already show reduced mitochondrial function.

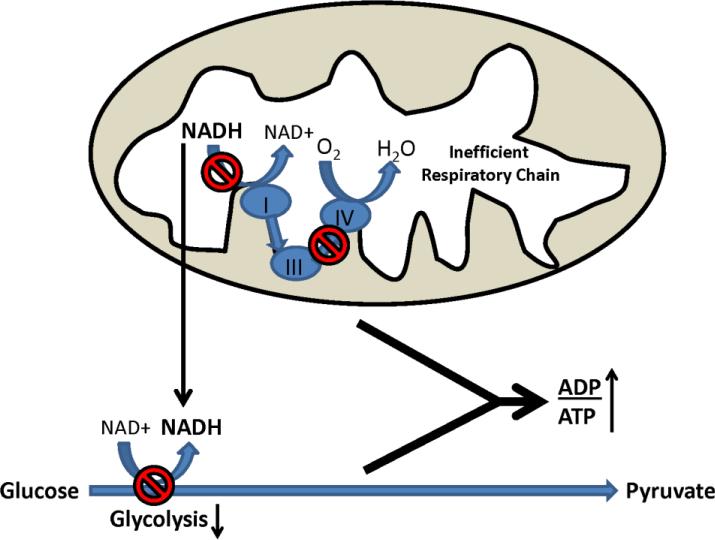

We recently analyzed glycolysis and respiratory fluxes in AD, MCI, and control cybrid cell lines [93]. The AD and MCI lines showed reduced basal oxygen consumption, which suggests reduced respiratory flux. This was despite the fact that AD and MCI respiration was relatively uncoupled, or less efficient, than control cybrid respiration. AD and MCI cybrid glycolysis fluxes were also relatively lower, a somewhat unexpected finding as cultured cells typically show inverse respiration-glycolysis relationships [98]. Redox changes may explain this paradox (Figure 3). NAD+/NADH ratios in AD and MCI cybrids were lower than they were in control cybrids; this probably reflects compromised respiratory function. A falling NAD+/NADH ratio, though, would predictably reduce glycolysis flux as glycolysis rates and NAD+/NADH ratios directly correlate. This finding provides potential insight into why respiration and glucose utilization both decline in AD subject brains [99-101].

Figure 3. Proposed mechanism through which respiratory decline can reduce glucose utilization.

In the presence of respiratory chain impairment, which in AD could result from reduced COX activity, NADH generated within the mitochondria during the Krebs cycle cannot be oxidized. Increased NADH in the mitochondrial compartment, in turn, transmits indirectly to the cytosolic compartment. Shifting the cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio towards NADH slows glycolysis, since glycolysis rates are to some extent determined by the cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio. Reductions in both respiration and glycolysis fluxes results in less ATP production, and increases the cell ADP/ATP ratio.

AD and MCI cybrid cell lines successfully model numerous pathologies observed in AD and MCI subject brains (Table 1). When considering this it is important to keep in mind several points. First, in AD and MCI cybrids the observed changes most likely arise from changes in mitochondrial function. Second, the mitochondria used to generate these cybrid lines derive not from subject brains, but from subject platelets, which implies mitochondrial dysfunction in AD and MCI subjects exists independent of Aβ or neurodegeneration. Third, AD and MCI cybrid molecular changes persist in culture, thereby suggesting AD and MCI subject mtDNA differs from control subject mtDNA.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of AD brain and AD cybrid bioenergetic-related phenomena.

| Differences in AD versus control brains also observed in AD versus control cybrid cell lines |

|---|

| Low cytochrome oxidase Vmax activity |

| Increased oxidative stress markers |

| Increased Aβ |

| Activated stress signaling pathways |

| Reduced PGC1α mRNA |

| Reduced HIF1α protein |

| Activated apoptotic signaling |

| NFκB activation |

| Overall increased COX2 protein |

| Reduced mTOR protein |

| Increased mitochondrial fission |

| Decreased SIRT1 |

| Decreased O2 consumption |

| Decreased glucose utilization |

We do not yet know exactly how mtDNA in AD and MCI cybrids differs from mtDNA in control cybrids, but differences between AD and control subject mtDNA certainly occur. MtDNA from AD subject brains exhibits excess oxidative damage and deletions [47, 102-105]. Some studies report AD subject brains and lymphocytes show increased heteroplasmic mutation levels [106-108]. In aggregate, AD subject brains and blood cells contain less PCR-amplifiable mtDNA [47, 105, 109-111].

These differences presumably reflect somatic, or acquired, changes. While the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis assumes these differences contribute to AD, our hypothesis also predicts mtDNA inheritance as well as the inheritance of genes that maintain mtDNA and mitochondrial function also play an important role.

Several investigative lines argue mtDNA inheritance could influence AD risk. First, epidemiologic studies find that although both parents contribute to an individual's AD risk [112], mothers contribute more than fathers [113-116]. Second, maternal inheritance may specifically affect mid-life memory performance [117]. Third, particular mtDNA haplogroups or haplotypes reportedly modify AD risk, although this remains uncertain as inconsistencies exist between different haplogroup and haplotype association studies [118-128].

Endophenotype studies further suggest maternal inheritance uniquely contributes to AD risk. Endophenotypes are disease-associated characteristics, traits, or markers observed in the absence of a full disease state. Maternal inheritance appears to determine several AD endophenotypes. The first maternally-determined AD endophenotype was reported by Mosconi et al. in 2007 [129]. This study found that cognitively normal, middle-aged children of AD mothers, but not AD fathers, show reduced cerebral glucose utilization on fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET). Subsequent studies found that the cognitively intact children of AD mothers, relative to the cognitively intact children of AD fathers, show greater degrees of age-associated brain atrophy, faster rates of longitudinal brain atrophy, increased Aβ plaque deposition, elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) oxidative stress markers, and AD-like CSF Aβ changes [130-137]. As mentioned above maternal inheritance also influences memory test performance in middle-aged individuals, since in some demographics individuals with AD mothers do not score as well on memory tests as individuals with AD fathers [117]. A growing number of databases using different approaches currently report maternal inheritance-associated AD endophenotypes [138-141].

We recently measured platelet mitochondria COX activity in cognitively normal adult children of AD patients [142]. We defined three subject groups, those with an AD-affected mother, an AD-affected father, or un-affected parents. Mean COX activity was lower in subjects with AD-affected mothers than it was in the other two groups. Maternal inheritance, therefore, also associates with a systemic biochemical endophenotype.

Among nuclear genes, translocase of the outer mitochondria membrane 40 homolog (TOMM40) may play a major role [143-156]. This gene's product mediates the transfer of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria. The TOMM40 gene localizes to 19q13.2, by far the most strongly associated LOAD locus [157]. The APOE gene also resides at 19q13.2, and approximately 20 years ago investigators concluded APOE isoforms mediate the association [158, 159]. The TOMM40 and APOE genes, though, sit remarkably close to each other and linkage disequilibrium occurs between particular TOMM40 and APOE alleles.

The most studied linkage disequilibrium is the one defined by APOE4 and the TOMM40 rs10524523 polyT polymorphism [143, 160]. The TOMM40 rs10524523 polyT polymorphism, located in intron 6, demonstrates substantial variation. In one classification scheme, polyT stretches of 19 or less constitute a “short” allele, polyT stretches of 20-29 define a “long” allele, and polyT stretches of 30 or more represent a “very long” allele. In Caucasian populations, the TOMM40 long allele typically segregates with the AD-associated APOE4 allele.

On a pure genetic level, linkage disequilibrium between particular TOMM40 and APOE alleles confounds AD-gene association assumptions, and makes it difficult to know whether TOMM40, APOE, or both genes truly mediate AD risk [161]. While some investigators argue TOMM40 will not turn out to play a role in AD [162, 163], from a strict association perspective it does appear that the TOMM40 gene, and by extension its protein product, could potentially impact LOAD. The APOE gene product, interestingly, also appears to influence mitochondrial function [164-167]. It will be interesting to see how this story evolves.

Polymorphisms in other nuclear genes, for example transcription factor A of the mitochondria (TFAM), associate with AD risk in some studies [168-170]. Associations such as these, though, are currently considered preliminary rather than conclusive. Also, it is important to keep in mind that respiratory chain holoenzymes contain multiple subunits. Complexes I, III, IV, and V contain both mtDNA and nuclear DNA-encoded subunits. This could obscure the contributions of individual respiratory chain genes. For example, we recently surveyed the breadth of polymorphic variation in the 13 COX subunit genes [171]. Among 27 individuals in which the exons of each COX gene were sequenced, no two individuals exhibited an identical composite genotype. We also sequenced the three mtDNA COX genes in fifty subjects. 20% had at least one non-synonymous polymorphism, and synonymous polymorphisms were even more common.

These and other data in this section argue inheritance determines an individual's baseline mitochondrial function and durability, and maternal inheritance plays a greater role than paternal inheritance [30]. This in turn influences AD-relevant phenomena including memory, bioenergetics, amyloidosis, and brain atrophy. Another assumption, that declining mitochondrial function occurs with advancing age, is generally accepted [35, 80, 81].

Data also argue mitochondria directly influence other AD-associated pathologies, and particularly APP and Aβ homeostasis. Cell culture experiments showing mitochondrial function and cell bioenergetics affect APP processing were previously mentioned [49-52, 172], and functional imaging data consistent with this principle were recently published [173]. mtDNA polymorphisms influence Aβ production and plaque deposition in mice that express an APP transgene [174]. Further, crossing mutant APP-PS1 transgenic mice that overproduce Aβ with COX-deficient mice dramatically lowers Aβ levels [175, 176]. At face value this finding might seem inconsistent with the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis, but in light of recent studies that define actual Aβ-AD temporal relationships we believe these data are quite consistent with our hypothesis. We discuss this in detail in the next section. Regardless, these mouse studies strongly underscore the presence of a mitochondria-Aβ nexus.

Finally, we note recent reports that show brains normally produce Aβ, and that Aβ production rates correlate with normal physiologic states such as sleep-wake cycles [177-184]. Overall, we feel we can confidently state APP and Aβ homeostasis are exquisitely regulated processes, and bioenergetic metabolism regulates these processes.

4. Biomarker Data: Relationships and Implications

Biomarkers consist of measurable biological endpoints, and ideally provide insight into disease-related phenomena. They can facilitate disease diagnosis, track disease progression, quantify disease risk, demonstrate treatment target engagement, or predict treatment response. Current popular AD biomarkers include FDG PET; structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); amyloid PET; and CSF Aβ, tau, and phosphorylated tau levels.

FDG PET quantifies brain glucose utilization. Regional reductions in brain glucose utilization occur with aging and to a greater extent in MCI and AD [185-193]. Glucose utilization and synaptic density directly correlate, so to some extent FDG PET reflects synaptic integrity [194]. With MRI, investigators can measure and track brain global and regional brain volumes. Regional reductions occur during aging, and become more pervasive with MCI and AD [195, 196]. Amyloid PET takes advantage of radiolabeled ligands that bind fibrillar Aβ, reveal the presence or absence of amyloid plaques, and estimate plaque burden [197-200]. Relative to control subjects, MCI and AD subjects typically show low CSF Aβ, high total tau, and high phosphorylated tau levels [201, 202]. Some feel CSF Aβ falls because of disease-associated solubility changes, or because it begins to stick to parenchymal plaques [203]. Tau rises, some claim, as increasing numbers of dead or dying neurons release their intracellular contents. The actual underlying mechanism, though, to some extent remains uncertain [204].

In 2010, Jack et al. summarized biomarker temporal relationships [205]. Their timeline states that in individuals who develop AD, Aβ plaque deposition and reduced CSF Aβ occur first. Next, CSF tau levels rise. These changes manifest years before clinical signs or symptoms develop. Later on hippocampal atrophy appears, followed shortly thereafter by memory decline and eventually dementia. Full progression from Aβ changes to clinical decline takes approximately 10 to 20 years.

The amyloid cascade hypothesis interprets this biomarker timeline in the following way. Aβ forms and accumulates within the brain. It damages and kills neurons, which spill tau. Eliminating a critical mass of neurons shrinks the brain, disrupts structural and functional integrity, and causes clinical symptoms.

The amyloid cascade hypothesis further assumes reduced FDG PET glucose utilization follows Aβ changes but precedes clinical changes. Also, Aβ plays a double role, since it acts as a biomarker of the disease, as well as causes the disease. Indeed, the “upstream” Aβ biomarkers presumably drive changes in the “downstream” CSF tau, MRI, and FDG PET biomarkers [20]. Aβ biomarkers, therefore, indicate the presence of AD while the CSF tau, MRI, and FDG PET biomarkers indicate the presence of Aβ-induced neurodegeneration.

The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis, on the other hand, does not assume Aβ drives the other biomarker changes. Our hypothesis, therefore, can accommodate a growing realization that for many subjects with suspected AD, or who have an increased risk of developing AD, what are currently considered downstream biomarker changes potentially precede upstream biomarker changes [206-213]. Also, the fact that Aβ accumulates for over a decade before symptoms arise [214], a finding that infers brains tolerate Aβ reasonably well, does not challenge our hypothesis. To us, Aβ may damage the brain a lot, a little, or not at all.

Moreover, as plaque prevalence rises with age regardless of the presence or absence of dementia [215], we believe it makes sense to view Aβ biomarkers primarily as biomarkers of brain aging. Over a given time period subjects with positive Aβ biomarkers will more likely develop cognitive decline than subjects with negative Aβ biomarkers not because positive Aβ biomarkers necessarily indicate AD, but because positive Aβ biomarkers indicate more advanced (beyond what is inferred when no Aβ biomarkers are present) brain aging.

Recent data indicate plaque deposition essentially occurs during the run-up to clinical AD [216, 217]. Plaque formation rates also vary over time [217]. After a period of rapid accumulation, plaque deposition gradually slows and by the time symptoms manifest plaque deposition is essentially done [20, 205, 218]. According to our hypothesis, Aβ deposition temporally coincides with an asymptomatic stage of compensated brain aging (a period during which strained physiologic or molecular infrastructures are essentially maintained and clinical integrity persists), as opposed to a symptomatic stage of uncompensated brain aging (a period during which strained physiologic or molecular infrastructures are not maintained and clinical deterioration ensues) (Figure 4).

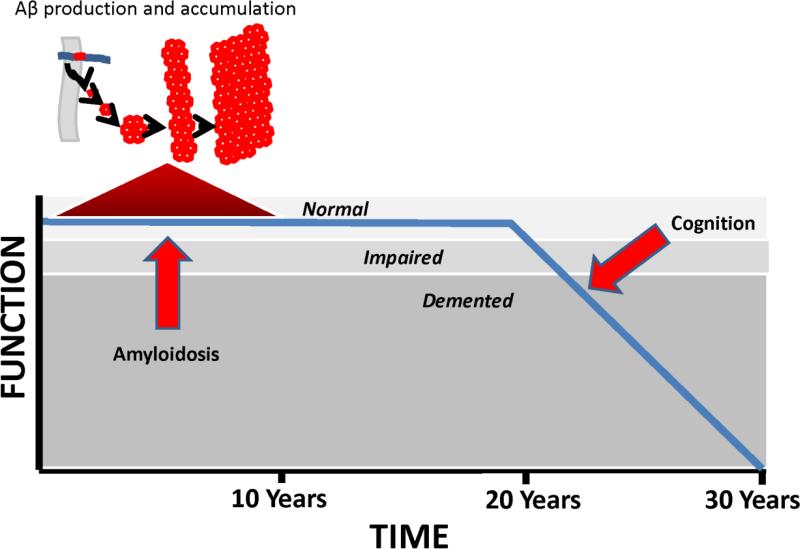

Figure 4. The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis and Aβ accumulation.

When age-associated mitochondrial decline first begins, neurons compensate by pushing their bioenergetic infrastructures. During this period of bioenergetic compensation, Aβ production increases and Aβ accumulates. As age-associated mitochondrial decline progresses, neurons can no longer bioenergetically compensate and bioenergetic-related parameters such as mitochondrial mass down-regulate. During this hypometabolic period, Aβ production decreases.

We propose the following explanation applies. Under conditions of mild bioenergetic stress the brain become relatively hypermetabolic. Bioenergetic hypermetabolism, in turn, increases Aβ production. As bioenergetic stress worsens, the brain shifts from a state of bioenergetic hypermetabolism to one of hypometabolism, and Aβ production falls.

Consistent with this view, data suggest normal age-related CSF Aβ levels vary with age. Studies of non-demented individuals report that while CSF Aβ levels seem to decline during young adulthood, during late mid-life CSF Aβ levels may actually slightly increase [219, 220]. Also, emerging data from FDG PET and cerebral perfusion studies show glucose utilization and cerebral blood flow may regionally increase around the time that plaque deposition begins [221, 222]. This scheme further fits, we feel, with studies of AD subject brains that show inter and even intra-neuron variations in specific mitochondrial mass markers [47, 105, 223, 224].

Mice engineered to overproduce mutant APP and PS1 proteins in the setting of less COX holoenzyme may provide additional insight into this issue. The brains of these mice show reduced plaque deposition, less fibrillar Aβ, and less oxidative stress than APP-PS1 mice that can freely produce COX [175, 176]. We wonder whether the COX problem in these mice models a COX defect more severe than the one modeled by our AD cybrid model [52, 172], and produces a hypometabolic environment while our AD cybrids produce a hypermetabolic environment.

Finally, we predict falling Aβ CSF levels reflect falling Aβ production more than it reflects decreased solubility or increased incorporation into plaques. Mathematical simulations based on the amyloid cascade hypothesis and other studies suggest otherwise, and argue during the course of AD Aβ production rates do not decline [203, 225]. The AD symptomatic period, however, can last over a decade [226]. Minimal fibrillar Aβ deposition occurs during this time [214, 217], CSF Aβ levels remain low [201, 205], and Aβ does not appreciably shift to the blood compartment [227, 228]. If Aβ production rates do not decline during this time, then where does all the Aβ go?

5. New AD Definitions: Relationships and Implications

Until recently, research involving AD subjects almost exclusively utilized the 1984 McKhann criteria [229]. Under these criteria, only clinically demented individuals could receive an AD diagnosis. However, subsequent research revealed non-demented subjects with objective cognitive decline often progress to a dementia syndrome and an AD diagnosis. The MCI designation captured these subjects [94-96]. Additional research also suggested that relative to individuals with no subjective cognitive complaints, elderly individuals with subjective cognitive complaints are more likely to develop AD [193, 230-233].

Autopsy studies reveal at the time of death, brains from cognitively normal individuals frequently contain plaques [77, 234-237]. More recently, technology advances make it possible to identify plaques in living subjects with fully preserved cognition, subjective cognitive impairment, MCI, and AD [197, 198, 200, 238, 239]. To take advantage of biomarker advances, and to specifically identify those in the earliest stages of AD or at the highest risk of AD, new diagnostic criteria were proposed [20, 240]. One set of updated criteria, published in 2011, consider Aβ an “upstream” biomarker [20]. Accordingly, the presence of Aβ plaques or low CSF Aβ implies the presence of AD, even in non-demented subjects.

“Prodromal” AD applies to subjects with Aβ changes and MCI [240]. “Preclinical” AD applies to subjects with Aβ changes and either fully normal cognition or questionable cognitive changes that don't quite justify an MCI clinical diagnosis [20]. These expanded criteria dramatically increase the number of elderly that qualify for an AD diagnosis, or at least some form of it; one literature- based analysis concludes 85% of those over 85 meet at least one of the new AD criteria [26].

The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis perspective differs somewhat. Because we do not assume Aβ causes AD, we would not make it the sole defining AD diagnostic criterion. After all, many with plaques will remain asymptomatic for years or even decades, and perhaps some will never develop symptoms [241]. Further, plaque deposition may coincide temporally with a period of compensated brain aging, and data argue symptoms generally manifest only after plaques stop forming (Figure 5) [205, 216, 217]. In the absence of symptoms or signs, therefore, using the presence or absence of plaques to define stages of brain aging, as opposed to AD, seems reasonable.

Figure 5. Aβ accumulation and cognitive decline timelines.

Before notable cognitive decline commences, Aβ accumulation initiates, accelerates, peaks, and decelerates. By the time cognitive decline begins, Aβ accumulation virtually has virtually ceased.

In essence, the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis sees plaque deposition as technically marking one's passage through brain aging, as opposed to one's passage into AD. According to our hypothesis, in asymptomatic individuals plaques indicate a higher AD risk (or at least a higher risk of developing symptomatic AD) as their presence indicates a more advanced state of brain aging.

Lastly, it is worth noting that at least some elements of cognitive decline evolve throughout adulthood [195, 242-245]. Cognitive speed and multitasking abilities, for example, become less robust with advancing age. These changes typically manifest at ages younger than those at which plaque deposition typically begins. The amyloid cascade hypothesis [14, 15], in conjunction with the newly designated preclinical AD category [20], necessarily infers cognitive changes that arise before plaques appear are etiologically unrelated to cognitive changes that arise after plaques appear. Under the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis, pre-plaque and post-plaque cognitive changes can potentially share a common etiology. For this reason, we believe our hypothesis better accommodates data that argue early adult cognitive markers predict AD risk long before plaques and probably Aβ changes occur [246, 247].

6. Therapeutic Development: Implications

If Aβ initiates and sustains an AD-specific cascade, removing it or preventing its creation would ideally arrest onset or progression. In one human study, a vaccine to Aβ did reduce plaque burden, a remarkable technical achievement [248, 249]. While safety concerns caused this trial to terminate prematurely, subsequent clinical analyses were at best unimpressive [250, 251].

Trials featuring intravenous infusions of antibodies to Aβ failed to meet their primary endpoints [252]. One of these antibodies, which to date has not yet reported any post-hoc evidence of clinical efficacy in its phase 3 trials, appears to reduce plaque burden [253]. The other did not show a straightforward reduction in plaque burden, but despite this a subsequent alternative analysis argued clinical effects should not be ruled out and called for further studies [254].

A γ secretase inhibitor did make it to phase III testing, but safety issues and accelerated decline in the treatment group brought this trial to an early end [255]. A drug intended to modify γ secretase activity similarly failed [256]. An agent claimed to inhibit Aβ oligomer formation did not meet its primary endpoint and further development was discontinued [257, 258].

Several explanations could explain these generally disappointing results [252]. Perhaps the underlying premise, that Aβ both initiates and sustains an AD-specific cascade, is wrong. Maybe the attempted interventions did not adequately engage their target, or investigators enrolled too many misdiagnosed subjects. It is also possible Aβ-based approaches will work in some populations but not in others. Because all reported trials studied symptomatic AD subjects whose brains, it is postulated, may already contain critical amounts of Aβ-induced damage, some investigators now believe the wrong subjects were tested. According to this reasoning, Aβ-based approaches might prevent asymptomatic or barely symptomatic preclinical AD subjects from progressing to symptoms [252], despite the fact these approaches appear to accelerate, not impact, or at best very minimally slow symptomatic subject progression.

Future studies, therefore, will probe Aβ-based interventions in subjects meeting the new preclinical AD criteria [20]. As people meeting preclinical AD criteria may remain cognitively stable for many years [205, 214], these trials will take a long time to complete. An alternative design will test Aβ-based interventions in asymptomatic FAD subjects with presenilin 1 mutations, as their age of symptomatic onset is reasonably predictable [259, 260].

The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis, though, predicts Aβ-based interventions failed not because these trials enrolled the wrong patients, but because Aβ does not cause LOAD. Further, our hypothesis predicts that even if Aβ-based interventions turn out to benefit FAD patients, benefits may not extrapolate well to LOAD because LOAD and FAD cascades potentially differ.

As Aβ-based “secondary prevention trials” begin in preclinical AD subjects, we wonder if nature in some way has already conducted such a trial. We now know from biomarker studies that brain amyloidosis burns itself out before clinical signs and symptoms emerge [217]. To us, this suggests Aβ-based interventions designed to remove or prevent Aβ from accumulating before this process naturally stops on its own will prove superfluous and, therefore, ineffective. The fact that the amyloid tap turns itself off before clinical changes appreciably manifest, we feel, also argues against the idea that Aβ perpetuates itself in a prion-like fashion [261].

While the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis perspective assumes removing Aβ will transform the course of neither brain aging nor AD, the presence of a mitochondrial-APP-presenilin nexus suggests drugs that modify this nexus may yet modify AD. γ secretase inhibition, after all, did accelerate cognitive decline [255]. Trials of β secretase inhibitors still need to play out, especially since inhibiting β secretase-mediated APP cleavage should change levels of APP and its α secretase-generated sAPPα product. Altering levels of APP and of sAPPα, a growth factor [262], may impact AD more than altering Aβ levels.

In general, we feel removing Aβ from the brains of LOAD patients will only help to the extent that Aβ toxicity contributes to LOAD. If Aβ contributes substantially removing it may help substantially, but if it contributes a little or not at all, then removing Aβ will help a little or not at all. We suspect the latter possibility will prove to be the case, and that removing Aβ will not actually remove the cause of AD but instead an epiphenomenon of aging. Finally, as we believe mitochondrial dysfunction initiates LOAD, we would instead advocate developing mitochondrial or bioenergetic medicine approaches for the treatment of LOAD [263-266]. If correct, we believe, such approaches will benefit both asymptomatic and symptomatic individuals. We therefore think it still makes sense to enroll AD subjects in AD trials.

7. Conclusions

The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis offers unique AD perspectives. At the clinical level, it tends to lump rather than split age-associated and AD-associated cognitive changes. At the etiological level, our hypothesis tends to split rather than lump LOAD and FAD. Accordingly, we believe FAD's unique genetics etiologically distinguishes FAD from LOAD more than it links FAD to LOAD.

The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis sees Aβ as a marker of brain aging, and not AD's singular cause. Because of this, we would not solely equate the presence of brain Aβ changes with the presence of AD, and we would not universally consider the Aβ deposition process as a disease process. According to our hypothesis, Aβ marks a continuum between brain aging and AD, as opposed to a unique and age-unrelated event. In some ways, therefore, brain aging and LOAD also represent a continuum.

The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis proposes changes in mitochondrial function change Aβ homeostasis. Early on, these mitochondrial changes increase Aβ production and cause it to accumulate. Later on, as mitochondrial dysfunction surpasses a threshold Aβ production and accumulation declines.

Because Aβ is considered a consequence of brain aging as opposed to the cause of a disease, we predict targeted removal of brain Aβ will only benefit AD patients to the extent Aβ mediates brain damage. We further predict targeted Aβ removal will benefit asymptomatic subjects to the same extent it benefits symptomatic subjects.

According to our hypothesis, arresting brain aging will arrest both the development and progression of AD. We believe manipulating mitochondrial function and cell bioenergetic pathways will ultimately achieve this goal.

Highlights.

- The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis argues bioenergetic dysfunction mediates Alzheimer's disease (AD).

- It assumes AD-associated biomarker changes reflect brain aging.

- It assumes a recently proposed AD clinical classification scheme stages brain aging.

- It assumes removing Aβ from symptomatic or presymptomatic individuals will marginally impact cognition.

Acknowledgements

RHS and JMB are supported by P30AG035982 and the Frank and Evangeline Thompson Alzheimer's Treatment Program Fund.

Abbreviations

Aβ

beta amyloid

AD

Alzheimer's disease

APP

amyloid precursor protein

COX

cytochrome oxidase

COX2

cytochrome oxidase subunit 2

CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

cybrid

cytoplasmic hybrid

DAT

dementia of the Alzheimer's type

FAD

familial Alzheimer's disease

FDG PET

fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

HIF1α

hypoxia induction factor 1 α; late-onset Alzheimer's disease

LOAD

late-onset Alzheimer's disease

MCI

mild cognitive impairment

MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

NAD

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

PEG

polyethylene glycol

PGC1α

peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma complex 1 α

sAPPα

soluble amyloid precursor protein α

SDAT

senile dementia of the Alzheimer's type

SIRT1

silent information regulator of transcription 1

TFAM

transcription factor A of the mitochondria

TOMM40

translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane 40 homolog

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

SK is a shareholder in Gencia Corporation, a biopharmaceutical company developing an Alzheimer's disease therapy.

References

- 1.Alzheimer A. Uber eine eigenartige Erkrankung der Hirnrinde. Allg Z Psychiat Psych-Gerichtl Med. 1907;64:146–148. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kraepelin E. Psychiatrie. Ein Lehrbuch fur Studierende und Arzte., Klinishce Psychiatrie. Verlag Johann Ambrosius Barth; Lepzig: 1910. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Divry P. Etude histochimique des plaques seniles. J. Belg. Neurol. Psychiatry. 1927;9:643–657. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer's disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;120:885–890. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, Quinlan M, Wisniewski HM, Binder LI. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4913–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik KH, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Muller-Hill B. The precursor of Alzheimer's disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature. 1987;325:733–736. doi: 10.1038/325733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amaducci LA, Rocca WA, Schoenberg BS. Origin of the distinction between Alzheimer's disease and senile dementia: how history can clarify nosology. Neurology. 1986;36:1497–1499. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.11.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katzman R. Editorial: The prevalence and malignancy of Alzheimer disease. A major killer. Arch Neurol. 1976;33:217–218. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1976.00500040001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swerdlow RH. Is aging part of Alzheimer's disease, or is Alzheimer's disease part of aging? Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1465–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goate A, Chartier-Harlin MC, Mullan M, Brown J, Crawford F, Fidani L, Giuffra L, Haynes A, Irving N, James L, et al. Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1991;349:704–706. doi: 10.1038/349704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherrington R, Rogaev EI, Liang Y, Rogaeva EA, Levesque G, Ikeda M, Chi H, Lin C, Li G, Holman K, et al. Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1995;375:754–760. doi: 10.1038/375754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy-Lahad E, Wasco W, Poorkaj P, Romano DM, Oshima J, Pettingell WH, Yu CE, Jondro PD, Schmidt SD, Wang K, et al. Candidate gene for the chromosome 1 familial Alzheimer's disease locus. Science. 1995;269:973–977. doi: 10.1126/science.7638622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe MS, Xia W, Ostaszewski BL, Diehl TS, Kimberly WT, Selkoe DJ. Two transmembrane aspartates in presenilin-1 required for presenilin endoproteolysis and gamma-secretase activity. Nature. 1999;398:513–517. doi: 10.1038/19077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardy J, Allsop D. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 1991;12:383–388. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. A beta oligomers - a decade of discovery. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1172–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Jr., Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR, Jr., Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swerdlow RH. Mitochondria and cell bioenergetics: increasingly recognized components and a possible etiologic cause of Alzheimer's disease. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2012;16:1434–1455. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swerdlow RH. Alzheimer's disease pathologic cascades: who comes first, what drives what. Neurotoxicity research. 2012;22:182–194. doi: 10.1007/s12640-011-9272-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swerdlow RH, Burns JM, Khan SM. The Alzheimer's disease mitochondrial cascade hypothesis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S265–279. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swerdlow RH, Khan SM. A “mitochondrial cascade hypothesis” for sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Medical hypotheses. 2004;63:8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2003.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swerdlow RH, Khan SM. The Alzheimer's disease mitochondrial cascade hypothesis: an update. Experimental neurology. 2009;218:308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swerdlow RH. Brain aging, Alzheimer's disease, and mitochondria. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2011;1812:1630–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swerdlow RH. Pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2:347–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trifunovic A, Wredenberg A, Falkenberg M, Spelbrink JN, Rovio AT, Bruder CE, Bohlooly YM, Gidlof S, Oldfors A, Wibom R, Tornell J, Jacobs HT, Larsson NG. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature. 2004;429:417–423. doi: 10.1038/nature02517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kujoth GC, Hiona A, Pugh TD, Someya S, Panzer K, Wohlgemuth SE, Hofer T, Seo AY, Sullivan R, Jobling WA, Morrow JD, Van Remmen H, Sedivy JM, Yamasoba T, Tanokura M, Weindruch R, Leeuwenburgh C, Prolla TA. Mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science. 2005;309:481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1112125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross JM, Stewart JB, Hagstrom E, Brene S, Mourier A, Coppotelli G, Freyer C, Lagouge M, Hoffer BJ, Olson L, Larsson NG. Germline mitochondrial DNA mutations aggravate ageing and can impair brain development. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker WD. Sporadic neurologic disease and the electron transport chain: a hypothesis. In: Pascuzzi RM, editor. Proceedings of the 1989 Scientfic Meeting of the American Society for Neurological Investigation: New Developments in Neuromuscular Disease. Indiana University Printing Services; Bloomington, Indiana: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parker WD, Jr., Boyson SJ, Parks JK. Abnormalities of the electron transport chain in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 1989;26:719–723. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linnane AW, Marzuki S, Ozawa T, Tanaka M. Mitochondrial DNA mutations as an important contributor to ageing and degenerative diseases. Lancet. 1989;1:642–645. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace DC. Mitochondrial genetics: a paradigm for aging and degenerative diseases? Science. 1992;256:628–632. doi: 10.1126/science.1533953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin MT, Simon DK, Ahn CH, Kim LM, Beal MF. High aggregate burden of somatic mtDNA point mutations in aging and Alzheimer's disease brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:133–145. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harman D. The biologic clock: the mitochondria? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1972;20:145–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1972.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blass JP, Zemcov A. Alzheimer's disease. A metabolic systems degeneration? Neurochem Pathol. 1984;2:103–114. doi: 10.1007/BF02834249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibson GE, Sheu KF, Blass JP, Baker A, Carlson KC, Harding B, Perrino P. Reduced activities of thiamine-dependent enzymes in the brains and peripheral tissues of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:836–840. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520320022009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sims NR, Finegan JM, Blass JP. Altered glucose metabolism in fibroblasts from patients with Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:638–639. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198509053131013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sims NR, Finegan JM, Blass JP. Altered metabolic properties of cultured skin fibroblasts in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1987;21:451–457. doi: 10.1002/ana.410210507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sims NR, Finegan JM, Blass JP, Bowen DM, Neary D. Mitochondrial function in brain tissue in primary degenerative dementia. Brain Res. 1987;436:30–38. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91553-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoyer S. Brain oxidative energy and related metabolism, neuronal stress, and Alzheimer's disease: a speculative synthesis. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1993;6:3–13. doi: 10.1177/002383099300600101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoyer S. Brain glucose and energy metabolism abnormalities in sporadic Alzheimer disease. Causes and consequences: an update. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:1363–1372. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parker WD, Jr., Filley CM, Parks JK. Cytochrome oxidase deficiency in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1990;40:1302–1303. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.8.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beal MF. Aging, energy, and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:357–366. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castellani R, Hirai K, Aliev G, Drew KL, Nunomura A, Takeda A, Cash AD, Obrenovich ME, Perry G, Smith MA. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:357–360. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirai K, Aliev G, Nunomura A, Fujioka H, Russell RL, Atwood CS, Johnson AB, Kress Y, Vinters HV, Tabaton M, Shimohama S, Cash AD, Siedlak SL, Harris PL, Jones PK, Petersen RB, Perry G, Smith MA. Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3017–3023. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03017.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swerdlow R, Marcus DL, Landman J, Kooby D, Frey W, 2nd, Freedman ML. Brain glucose metabolism in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Med Sci. 1994;308:141–144. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199409000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Webster MT, Pearce BR, Bowen DM, Francis PT. The effects of perturbed energy metabolism on the processing of amyloid precursor protein in PC12 cells. J Neural Transm. 1998;105:839–853. doi: 10.1007/s007020050098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gabuzda D, Busciglio J, Chen LB, Matsudaira P, Yankner BA. Inhibition of energy metabolism alters the processing of amyloid precursor protein and induces a potentially amyloidogenic derivative. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13623–13628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gasparini L, Racchi M, Benussi L, Curti D, Binetti G, Bianchetti A, Trabucchi M, Govoni S. Effect of energy shortage and oxidative stress on amyloid precursor protein metabolism in COS cells. Neurosci Lett. 1997;231:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00536-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khan SM, Cassarino DS, Abramova NN, Keeney PM, Borland MK, Trimmer PA, Krebs CT, Bennett JC, Parks JK, Swerdlow RH, Parker WD, Jr., Bennett JP., Jr. Alzheimer's disease cybrids replicate beta-amyloid abnormalities through cell death pathways. Annals of neurology. 2000;48:148–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith MA, Rudnicka-Nawrot M, Richey PL, Praprotnik D, Mulvihill P, Miller CA, Sayre LM, Perry G. Carbonyl-related posttranslational modification of neurofilament protein in the neurofibrillary pathology of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 1995;64:2660–2666. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64062660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Markesbery WR. The role of oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:1449–1452. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.12.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blass JP, Baker AC, Ko L, Black RS. Induction of Alzheimer antigens by an uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:864–869. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530080046009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Szabados T, Dul C, Majtenyi K, Hargitai J, Penzes Z, Urbanics R. A chronic Alzheimer's model evoked by mitochondrial poison sodium azide for pharmacological investigations. Behav Brain Res. 2004;154:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ichimura H, Parthasarathi K, Quadri S, Issekutz AC, Bhattacharya J. Mechano-oxidative coupling by mitochondria induces proinflammatory responses in lung venular capillaries. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:691–699. doi: 10.1172/JCI17271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caspersen C, Wang N, Yao J, Sosunov A, Chen X, Lustbader JW, Xu HW, Stern D, McKhann G, Yan SD. Mitochondrial Abeta: a potential focal point for neuronal metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J. 2005;19:2040–2041. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3735fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lustbader JW, Cirilli M, Lin C, Xu HW, Takuma K, Wang N, Caspersen C, Chen X, Pollak S, Chaney M, Trinchese F, Liu S, Gunn-Moore F, Lue LF, Walker DG, Kuppusamy P, Zewier ZL, Arancio O, Stern D, Yan SS, Wu H. ABAD directly links Abeta to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2004;304:448–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1091230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manczak M, Anekonda TS, Henson E, Park BS, Quinn J, Reddy PH. Mitochondria are a direct site of A beta accumulation in Alzheimer's disease neurons: implications for free radical generation and oxidative damage in disease progression. Human molecular genetics. 2006;15:1437–1449. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anandatheerthavarada HK, Biswas G, Robin MA, Avadhani NG. Mitochondrial targeting and a novel transmembrane arrest of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein impairs mitochondrial function in neuronal cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:41–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anandatheerthavarada HK, Devi L. Amyloid precursor protein and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscientist. 2007;13:626–638. doi: 10.1177/1073858407303536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Devi L, Prabhu BM, Galati DF, Avadhani NG, Anandatheerthavarada HK. Accumulation of amyloid precursor protein in the mitochondrial import channels of human Alzheimer's disease brain is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9057–9068. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1469-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crouch PJ, Blake R, Duce JA, Ciccotosto GD, Li QX, Barnham KJ, Curtain CC, Cherny RA, Cappai R, Dyrks T, Masters CL, Trounce IA. Copper-dependent inhibition of human cytochrome c oxidase by a dimeric conformer of amyloid-beta1-42. J Neurosci. 2005;25:672–679. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4276-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hansson CA, Frykman S, Farmery MR, Tjernberg LO, Nilsberth C, Pursglove SE, Ito A, Winblad B, Cowburn RF, Thyberg J, Ankarcrona M. Nicastrin, presenilin, APH-1, and PEN-2 form active gamma-secretase complexes in mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51654–51660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404500200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hansson Petersen CA, Alikhani N, Behbahani H, Wiehager B, Pavlov PF, Alafuzoff I, Leinonen V, Ito A, Winblad B, Glaser E, Ankarcrona M. The amyloid beta-peptide is imported into mitochondria via the TOM import machinery and localized to mitochondrial cristae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13145–13150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806192105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Teng FY, Tang BL. Widespread gamma-secretase activity in the cell, but do we need it at the mitochondria? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Balaban RS, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell. 2005;120:483–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gadaleta MN, Cormio A, Pesce V, Lezza AM, Cantatore P. Aging and mitochondria. Biochimie. 1998;80:863–870. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)88881-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lenaz G, D'Aurelio M, Merlo Pich M, Genova ML, Ventura B, Bovina C, Formiggini G, Parenti Castelli G. Mitochondrial bioenergetics in aging. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1459:397–404. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Corrada MM, Brookmeyer R, Paganini-Hill A, Berlau D, Kawas CH. Dementia incidence continues to increase with age in the oldest old: the 90+ study. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:114–121. doi: 10.1002/ana.21915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Corrada MM, Brookmeyer R, Berlau D, Paganini-Hill A, Kawas CH. Prevalence of dementia after age 90: results from the 90+ study. Neurology. 2008;71:337–343. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310773.65918.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yaffe K, Middleton LE, Lui LY, Spira AP, Stone K, Racine C, Ensrud KE, Kramer JH. Mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and their subtypes in oldest old women. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:631–636. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jorm AF, Jolley D. The incidence of dementia: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 1998;51:728–733. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.3.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hogan DB. If we live long enough, will we all be demented?: redux. Neurology. 2008;71:310–311. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319660.82871.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Polvikoski T, Sulkava R, Myllykangas L, Notkola IL, Niinisto L, Verkkoniemi A, Kainulainen K, Kontula K, Perez-Tur J, Hardy J, Haltia M. Prevalence of Alzheimer's disease in very elderly people: a prospective neuropathological study. Neurology. 2001;56:1690–1696. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.12.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Polvikoski T, Sulkava R, Rastas S, Sutela A, Niinisto L, Notkola IL, Verkkoniemi A, Viramo P, Juva K, Haltia M. Incidence of dementia in very elderly individuals: a clinical, neuropathological and molecular genetic study. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;26:76–82. doi: 10.1159/000090252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mizutani T, Shimada H. Neuropathological background of twenty-seven centenarian brains. J Neurol Sci. 1992;108:168–177. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(92)90047-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.den Dunnen WF, Brouwer WH, Bijlard E, Kamphuis J, van Linschoten K, Eggens-Meijer E, Holstege G. No disease in the brain of a 115-year-old woman. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:1127–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boveris A, Navarro A. Brain mitochondrial dysfunction in aging. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:308–314. doi: 10.1002/iub.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Navarro A, Boveris A. The mitochondrial energy transduction system and the aging process. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C670–686. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00213.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barrientos A, Casademont J, Cardellach F, Estivill X, Urbano-Marquez A, Nunes V. Reduced steady-state levels of mitochondrial RNA and increased mitochondrial DNA amount in human brain with aging. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;52:284–289. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kish SJ, Bergeron C, Rajput A, Dozic S, Mastrogiacomo F, Chang LJ, Wilson JM, DiStefano LM, Nobrega JN. Brain cytochrome oxidase in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 1992;59:776–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mutisya EM, Bowling AC, Beal MF. Cortical cytochrome oxidase activity is reduced in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 1994;63:2179–2184. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63062179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Parker WD, Jr., Parks J, Filley CM, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Electron transport chain defects in Alzheimer's disease brain. Neurology. 1994;44:1090–1096. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.6.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maurer I, Zierz S, Moller HJ. A selective defect of cytochrome c oxidase is present in brain of Alzheimer disease patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:455–462. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bunn CL, Wallace DC, Eisenstadt JM. Cytoplasmic inheritance of chloramphenicol resistance in mouse tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:1681–1685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.5.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chomyn A, Lai ST, Shakeley R, Bresolin N, Scarlato G, Attardi G. Platelet-mediated transformation of mtDNA-less human cells: analysis of phenotypic variability among clones from normal individuals--and complementation behavior of the tRNALys mutation causing myoclonic epilepsy and ragged red fibers. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;54:966–974. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.King MP, Attardi G. Human cells lacking mtDNA: repopulation with exogenous mitochondria by complementation. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1989;246:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.2814477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sheehan JP, Swerdlow RH, Miller SW, Davis RE, Parks JK, Parker WD, Tuttle JB. Calcium homeostasis and reactive oxygen species production in cells transformed by mitochondria from individuals with sporadic Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4612–4622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04612.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Swerdlow RH, Parks JK, Cassarino DS, Maguire DJ, Maguire RS, Bennett JP, Jr., Davis RE, Parker WD., Jr. Cybrids in Alzheimer's disease: a cellular model of the disease? Neurology. 1997;49:918–925. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.4.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Silva DF, Santana I, Esteves AR, Baldeiras I, Arduino DM, Oliveira CR, Cardoso SM. Prodromal Metabolic Phenotype in MCI Cybrids: Implications for Alzheimers Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012 doi: 10.2174/1567205011310020008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Silva DF, Selfridge JE, Lu J, E L, Roy N, Hutfles L, Burns JM, Michaelis EK, Yan S, Cardoso SM, Swerdlow RH. Bioenergetic flux, mitochondrial mass and mitochondrial morphology dynamics in AD and MCI cybrid cell lines. Hum Mol Genet. 2013 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt247. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Petersen RC. Clinical practice. Mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2227–2234. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0910237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rabins PV, Ritchie K, Rossor M, Thal L, Winblad B. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1985–1992. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.12.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Morris JC, Storandt M, Miller JP, McKeel DW, Price JL, Rubin EH, Berg L. Mild cognitive impairment represents early-stage Alzheimer disease. Archives of neurology. 2001;58:397–405. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Swerdlow RH, E L, Aires D, Lu J. Glycolysis-respiration relationships in a neuroblastoma cell line. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:2891–2898. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fukuyama H, Ogawa M, Yamauchi H, Yamaguchi S, Kimura J, Yonekura Y, Konishi J. Altered cerebral energy metabolism in Alzheimer's disease: a PET study. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Silverman DH, Small GW, Chang CY, Lu CS, Kung De Aburto MA, Chen W, Czernin J, Rapoport SI, Pietrini P, Alexander GE, Schapiro MB, Jagust WJ, Hoffman JM, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Alavi A, Clark CM, Salmon E, de Leon MJ, Mielke R, Cummings JL, Kowell AP, Gambhir SS, Hoh CK, Phelps ME. Positron emission tomography in evaluation of dementia: Regional brain metabolism and long-term outcome. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286:2120–2127. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.17.2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Frackowiak RS, Pozzilli C, Legg NJ, Du Boulay GH, Marshall J, Lenzi GL, Jones T. Regional cerebral oxygen supply and utilization in dementia. A clinical and physiological study with oxygen-15 and positron tomography. Brain. 1981;104:753–778. doi: 10.1093/brain/104.4.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mecocci P, MacGarvey U, Beal MF. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA is increased in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:747–751. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Corral-Debrinski M, Horton T, Lott MT, Shoffner JM, McKee AC, Beal MF, Graham BH, Wallace DC. Marked changes in mitochondrial DNA deletion levels in Alzheimer brains. Genomics. 1994;23:471–476. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hamblet NS, Castora FJ. Elevated levels of the Kearns-Sayre syndrome mitochondrial DNA deletion in temporal cortex of Alzheimer's patients. Mutat Res. 1997;379:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.de la Monte SM, Luong T, Neely TR, Robinson D, Wands JR. Mitochondrial DNA damage as a mechanism of cell loss in Alzheimer's disease. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2000;80:1323–1335. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Coskun PE, Beal MF, Wallace DC. Alzheimer's brains harbor somatic mtDNA control-region mutations that suppress mitochondrial transcription and replication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:10726–10731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403649101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Coskun PE, Wyrembak J, Derbereva O, Melkonian G, Doran E, Lott IT, Head E, Cotman CW, Wallace DC. Systemic mitochondrial dysfunction and the etiology of Alzheimer's disease and down syndrome dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S293–310. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chang SW, Zhang D, Chung HD, Zassenhaus HP. The frequency of point mutations in mitochondrial DNA is elevated in the Alzheimer's brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:203–208. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Brown AM, Sheu RK, Mohs R, Haroutunian V, Blass JP. Correlation of the clinical severity of Alzheimer's disease with an aberration in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN. 2001;16:41–48. doi: 10.1385/JMN:16:1:41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Davis RE, Miller S, Herrnstadt C, Ghosh SS, Fahy E, Shinobu LA, Galasko D, Thal LJ, Beal MF, Howell N, Parker WD., Jr. Mutations in mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase genes segregate with late-onset Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4526–4531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 111.Rodriguez-Santiago B, Casademont J, Nunes V. Is mitochondrial DNA depletion involved in Alzheimer's disease? European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2001;9:279–285. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Katzman R. Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:964–973. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198604103141506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Edland SD, Silverman JM, Peskind ER, Tsuang D, Wijsman E, Morris JC. Increased risk of dementia in mothers of Alzheimer's disease cases: evidence for maternal inheritance. Neurology. 1996;47:254–256. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.1.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Duara R, Lopez-Alberola RF, Barker WW, Loewenstein DA, Zatinsky M, Eisdorfer CE, Weinberg GB. A comparison of familial and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1993;43:1377–1384. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.7.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bassett SS, Avramopoulos D, Fallin D. Evidence for parent of origin effect in late-onset Alzheimer disease. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114:679–686. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]