Transcriptional Interactions Between Yeast tRNA Genes, Flanking Genes and Ty Elements: A Genomic Point of View (original) (raw)

Abstract

Retroelement insertion can alter the expression of nearby genes. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae retrotransposons Ty1–Ty4 are transcribed by RNA polymerase II (pol II) and target their integration upstream of genes transcribed by RNA polymerase III (pol III), mainly tRNA genes. Because tRNA genes can repress nearby pol II-transcribed genes, we hypothesized that transcriptional interference may exist between Ty1 insertions and pol III-transcribed genes, the preferred targets for Ty1 integration. Ty1s upstream of two pol III-transcribed genes (SNR6 and SUP2) were recovered and analyzed by RNA blot analysis. Ty1 insertions were found to exert a neutral or modest stimulatory effect on the expression of these genes. Further RNA analysis indicated a modest tRNA position effect on Ty1 transcription. To investigate the possible genomic relevance of these expression effects, we compiled a comprehensive tRNA gene database. This database allowed us to analyze a genome's worth of tRNA genes and Ty elements. It also enabled the prediction and experimental confirmation of tRNA gene position effects at native chromosomal loci. We provide evidence supporting the hypothesis that tRNA genes exert a modest inhibitory effect on adjacent pol II promoters. Direct analysis of PTR3 transcription, promoted by sequences very close to a tRNA gene, shows that this tRNA position effect can operate on a native chromosomal gene.

[The following individuals kindly provided reagents, samples, or unpublished information as indicated in the paper: S. Sandmeyer and J. McCusker.]

It is well known that the integration of retroelements can interfere with the expression of nearby genes (Roeder et al. 1980; Harrison et al. 1989; Kobayashi et al. 1998; Gaisne et al. 1999; Morgan et al. 1999). The five Ty retrotransposons found in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae apparently target their integration to nonessential regions or “safe havens.” Whereas Ty5 was found to preferentially insert in vivo at telomeric and silenced mating regions (Zou et al. 1996), Ty1–4 seem to target their integration upstream of tRNA genes. Moreover, Ty1 (Devine and Boeke 1996) and Ty3 (Chalker and Sandmeyer 1992) were found to target their integration just upstream of genes transcribed by RNA polymerase III (pol III), including SNR6, 5S rDNA, and tRNA genes. Because Ty1 and Ty2 insertions near genes transcribed by RNA polymerase II (pol II) can activate, vary, or inactivate their transcription (Boeke and Sandmeyer 1991) and Ty3 insertions in either orientation moderately increase steady-state levels of SUP2 pre-tRNA (Kinsey and Sandmeyer 1991), we hypothesized that Ty1 insertions might affect the expression of target pol III-transcribed genes as well.

In S. cerevisiae, actively transcribed tRNA genes have been shown to transcriptionally repress the expression of adjacent pol II-transcribed genes (Kinsey and Sandmeyer 1991; Hull et al. 1994; Kendall et al. 2000). This relatively ill-defined phenomenon, which we refer to as tRNA position effect, has also been called tRNA-mediated gene silencing (Kendall et al. 2000), and reportedly operates over a few hundred base pairs (bp) on both sides of the tRNA gene. The tRNA gene is only inhibitory when it is transcriptionally active (Hull et al. 1994; Kendall et al. 2000). The severity with which tRNA position effect down-regulates nearby pol II-transcribed genes, however, depends on the pol II promoter used in the reporter. α-factor-induced transcripts corresponding to Ty3 ς elements and full-length Ty3 elements were inhibited to varying degrees. ς elements were reportedly transcriptionally inhibited two- to 60-fold, whereas Ty3 elements were inhibited two- to 14-fold (Kinsey and Sandmeyer 1991; Hull et al. 1994). On the other hand, several artificially-juxtaposed pol II-transcribed reporter genes were strongly inhibited by a neighboring tRNA gene (Hull et al. 1994). We hypothesized that appropriately oriented Ty1 insertions near tRNA genes might suffer similar transcriptional inhibition. Alternatively, because Ty1 is probably evolutionarily adapted to survival in a tRNA-proximal environment, it may be relatively resistant to this form of inhibition.

Presently, the mechanism by which tRNA position effect occurs remains unclear. Kendall et al. (2000) have proposed, however, that subnuclear localization of tRNA genes to the nucleolus antagonizes transcription of nearby pol II-transcribed genes. Despite the evidence for tRNA position effect, little has been done to directly examine whether or not it operates on any of the 274 native chromosomal tRNA loci. One possibility is that pol II-transcribed genes found bordering these loci may be exempt, or conditionally resistant to this form of transcriptional inhibition. Alternatively, selective pressure might maintain the close association of such pol II-transcribed genes with tRNA loci as a general regulatory mechanism designed to maintain low levels of expression.

To test whether there is transcriptional interference between tRNA genes and Ty1 elements, we analyzed several in vivo Ty1 element insertions into target plasmids, containing either a marked SNR6 gene (U6mg) or a marked SUP2 tRNA gene (sup2+b) (Chalker and Sandmeyer 1992, 1993). We found Ty1 insertions to have a neutral, or in one case a stimulatory effect, on the expression of adjacent pol III-transcribed genes. Additionally, tRNA position effects on Ty1 insertions were measurable at considerable distances. The inhibition was partial, however, and quite modest. Finally, we present direct evidence that modest levels of tRNA position effects can actually operate at a native chromosomal locus, PTR3.

RESULTS

Integration of Ty1 Into Two pol III-Transcribed Target Regions

When a Ty1 element inserts upstream of a tRNA gene in divergent transcriptional orientation, the Ty1 pol II promoter and the tRNA pol III promoter can be separated by as little as 100–500 bp. To determine whether the neighboring pol II and pol III promoters were interfering with each other, Ty1-neo insertions were captured in vivo to generate a set of systematically structured constructs with a Ty1-neo element next to a pol III-transcribed reporter gene. The pol III-transcribed reporter genes U6mg (Chalker and Sandmeyer 1993) and sup2+b tRNA (Kinsey and Sandmeyer 1991) produce products distinguishable by size or hybridization properties, respectively, from their native counterparts, allowing effects on that target gene to be determined specifically without altering the functions of the chromosomal counterparts. The reporter genes are contained within the two 2 micron (2μ) HIS3 target plasmids, pDLC605 and pDLC356, respectively, and have been characterized previously. Figure 1 depicts all of the Ty1-neo insertions that were captured in each target plasmid. Twenty-two of 23 Ty1-neo integration events into pDLC605 occurred within the region upstream of the U6mg target gene, and one outlier lay downstream of U6mg (Fig. 1A). Similarly, most (20 of 29) of the Ty1-neo elements integrated upstream of the sup2+b target gene (Fig. 1B). The other nine insertions mapped just downstream of sup2+b. Clearly, the preferred sites of integration, as indicated by multiple insertions at the same position, lie within the region (200 to 83 bp) just upstream of either target gene. Although Ty1 targeting in these plasmids is qualitatively similar to that reported previously (Ji et al. 1993; Devine and Boeke 1996), the presence of a relatively small upstream genomic window combined with the presence of 2μ sequences, which are required for plasmid propagation, may have limited the Ty1 target area used in this study.

Figure 1.

Integration of Ty1-neo into _SNR6_- and _SUP2_-containing target plasmids. (A) U6mg represents the marked SNR6 gene, and (B) sup2+b is the marked SUP2 gene. The term genomic signifies that the sequence is the native sequence flanking the SNR6 or SUP2 loci, respectively, whereas _2_μ and HIS3 are vector sequences. Ty1-neo insertions into the target plasmids are depicted as small black arrowheads. Arrowheads pointing downward represent Ty1-neo insertions in the same transcriptional direction as the target gene, whereas those pointing upward are transcribed divergently from the target gene. The distance in base pairs from the major pol III transcription start sites (+1) is indicated (Kinsey and Sandmeyer 1991; Chalker and Sandmeyer 1993). The lowercase letters indicate the individual Ty1-neo insertion constructs that were used for expression studies.The Ty1-neo integration positions are −273, −147, −90, +318, −608, −289, −96, and −83 for a–h and −166, −105, −179, and −103 for t, u, w, and x, respectively.

Ty1 Insertions Exert Neutral or Mildly Positive Effects on Adjacent pol III-Transcription

To examine the effect that Ty1 insertions have on the expression of the genes they target for integration, total RNA isolated from cells carrying plasmid constructs with a single Ty1-neo insertion was subjected to quantitative RNA blot analysis, using U14 (control) and either _U6_- or sup2+_b_-specific probes. Figure 2 shows the effects that various Ty1-neo insertions had on the relative amount of U6mg transcripts that were produced. The level of U6mg RNA in cells containing a Ty1-neo insertion is expressed relative to the level in cells containing the pDLC605 control plasmid (Fig. 2B). The steady-state level of U6mg RNA was unaffected by any of the Ty1-neo insertions at the tested positions, lanes a–h in Figure 2, with the possible exceptions of insertions b and h, which show a 30% reduction in expression.

Figure 2.

Effect of Ty1-neo insertions on U6mg target gene expression. (A) RNA blot analysis of U6mg and U14 transcripts containing the target plasmid with a single integrated Ty1-neo element. Multiple yeast transformants containing the same Ty1-neo target plasmid were analyzed. RNA was also isolated from cells lacking the U6mg target plasmid (-target). The endogenous U6 snRNA (U6) present in all cells is indicated. The ratio of U6mg to U14 RNA was determined for each sample. These ratios were further normalized for plasmid copy number in each transformant. (B) Normalized RNA levels are relative to that of a target plasmid lacking a Ty1-neo insertion (-Ty1).

Only one Ty1 insertion had a significant effect on the production of sup2+b transcripts (Fig. 3). The level of sup2+b pre-tRNA in cells containing a Ty1-neo insertion is expressed relative to the level in cells containing the pDLC356 control plasmid (Fig. 3B). A Ty1-neo insertion at position x in Figure 3B, oriented such that the Ty1-neo element and the tRNA gene are transcribed divergently, increased the steady-state level of sup2+b pre-tRNA nearly fourfold. The data for the Ty1-neo insertion at position x shows a fair bit of scatter, but the effect is clearly significant (Fig. 3B). In most instances, however, especially for those positions of multiple independent insertions, the steady-state level of sup2+b pre-tRNA was only modestly affected by the Ty1-neo insertions (positions t and w in Fig. 3B). For unknown reasons, the scatter among independent transformants was greater for the sup2+b plasmids than for the U6mg constructs. All observed expression was tRNA promoter-dependent because control experiments done on promoter mutant constructs showed no expression (Fig. 3B; t*, u*, x* and w*).

Figure 3.

Effect of Ty1-neo insertions on pre-sup2+b target gene expression. (A) Representative RNA blots of pre-sup2+b and U14 transcripts from cells harboring plasmids with a Ty1-neo inserted at position t or x (* indicates the presence of a G56 mutation in box B of the sup2+b gene, rendering it transcriptionally inactive). Multiple yeast transformants containing the same Ty1-neo target plasmid were analyzed. RNA was also isolated from cells lacking the sup2+b target plasmid (-target). RNA blots are not shown for the target plasmids containing Ty1-neo insertions at positions u and w. The ratio of sup2+b to U14 RNA was determined for each sample, and normalized for plasmid copy number. As multiple species of pre-sup2+b transcript were present, indicated by the bracketed region, the sum of all bands in this region was measured. (B) RNA levels are relative to that of a target plasmid lacking a Ty1-neo insertion (-Ty1).

tRNA Position Effects on Ty1 Transcription

Because pol II promoters are reportedly regulated by tRNA position effect, we examined whether the Ty1 promoter was affected by its proximity to the SUP2 pol III promoter. To address the question of interference of a pol III promoter on a neighboring pol II promoter, we used the juxtaposed sup2+b tRNA gene and several integrated Ty1 elements, respectively. Additionally, sup2+b tRNA variants with a previously characterized C to G substitution in the box B internal promoter element (Chalker and Sandmeyer 1992, 1993) were constructed as controls. Mutation of this absolutely conserved C to a G at position 56 of the mature tRNA has been shown to decrease in vitro expression of the SUP4 tRNATyr gene ∼20-fold (Allison et al. 1983). Total RNA isolated from cells containing the mutant sup2+b(G56) tRNA constructs, indicated by an asterisk, was subjected to RNA blot analysis (Fig. 3B). As expected, no sup2+_b_-specific pre-tRNA was detected in these samples.

Further RNA blot analysis of total RNA from cells containing the sup2+b tRNA constructs and cells containing the promoter mutant sup2+b(G56) tRNA gene constructs (Fig. 4), indicated a modest difference in Ty1-neo expression consistent with tRNA position effect. Only those Ty1-neo insertions whose orientation placed the Ty1 promoter close to the tRNA promoter were affected (Fig. 4B, w and x). For these constructs, the steady-state level of Ty1-neo RNA in the presence of the transcriptionally inactive tRNA gene, sup2+b(G56), was approximately threefold higher (Fig. 4B, w* and x*) relative to the level of Ty1-neo RNA observed in the presence of the transcriptionally active tRNA gene, sup2+b. In Ty1 insertions at positions x and w, the transcription start site of the Ty1 element lies ∼330 bp and 400 bp, respectively, from the transcription start site of the sup2+b tRNA gene (Fig. 4B). Clearly, the transcriptionally active sup2+b tRNA gene interferes with expression from the upstream Ty1 promoter. These results, along with similar results observed for ς and Ty3 (Kinsey and Sandmeyer 1991; Hull et al. 1994) and other pol II-transcribed promoters fused to various reporter genes (Hull et al. 1994), indicate that tRNA genes might repress surrounding genes at their native chromosomal locations.

Figure 4.

Effect of sup2+b tRNA gene expression on Ty1-neo expression. (A) Representative RNA blots of Ty1-neo and ACT1 transcripts from the cells used in the previous figure. RNA blot is not shown for the target plasmid containing Ty1-neo insertion at position x. The ratio of Ty1-neo to ACT1 RNA was determined for each sample. Ratios, or levels, were adjusted for relative plasmid copy number. (B) Ty1-neo RNA levels in the absence of an actively transcribed tRNA gene (* indicates the presence of the G56 mutation in sup2+b) are relative to those in the presence of an actively transcribed tRNA gene.

Assembly and Survey of a Database of tRNA Gene Loci

We generated a tRNA- and Ty-centered database for several reasons: (1) to analyze the intergenic windows flanking tRNA genes to address the hypothesis that regions upstream of tRNA genes are “safe havens” for Ty element insertion; (2) to probe the hypothesis that windows exist as buffer regions to relieve potential tRNA position effects on adjacent pol II promoters; (3) to identify exceptions to the general trend of larger windows as buffer regions to examine whether tRNA position effects operate on flanking non-Ty sequences in the genome; and (4) to generate a public resource to foster further studies of tRNA loci and their associated Ty sequences.

The database covers the locations and orientations of the 274 tRNA genes in the yeast genome and their neighboring open reading frames (ORFs) as well as Ty sequences (SGD data as of July 2, 2002). The database was used to analyze the features surrounding tRNA genes (Fig. 5A). From an initial survey of the database, we show that the intergenic windows upstream of tRNA genes are larger that the downstream windows even after the removal of all annotated Ty sequence (Fig. 5B). The total mean upstream window is 2,330 bp long and the downstream window is 560 bp long. For comparison, the average genome-wide inter-ORF distance excluding telomeric regions (genome) was only 480 bp long. The upstream window value, however, is significantly inflated by inclusion of full-length Ty elements. Removal of these (Fig. 5B; -Ty elements) reduced the length of the upstream window to 1,310 bp and the downstream window to 510 bp. Even when all annotated Ty sequences including LTR fragments were removed from the windows (Fig. 5B; -Ty sequence) the upstream window was still 1,010 bp long, whereas those downstream were 490 bp long. Moreover, the noncoding pol II-transcribed genes, such as the small nuclear RNA genes except SNR6, are neither under- nor over-represented at tRNA loci.

Figure 5.

The tRNA gene loci database. (A) Graphic representation of the data included in the tRNA gene and Ty element database. Gene and Ty sequence nomenclature, coordinates and orientations are according to SGD. Gene expression data is according to the yeast Transcriptome database (Holstege et al. 1998). Intergenic distance measurements were based on the ORF coordinates assigned by SGD and not the start sites of transcription which remain to be determined for many genes. (B) The average intergenic window size upstream (5′, black bars) and downstream (3′, white bars) of all the tRNA genes in the genome (total). The average intergenic window size upstream (5′, black bars) and downstream (3′, white bars) of all the tRNA genes in the genome (total); if full-length Ty elements are excluded (-Ty elements); and if Ty element and LTR sequences are excluded (-Ty sequence) from the intergenic windows. The calculated mean genome-wide inter-ORF distance excluding telomeric regions (genome, gray) is indicated.

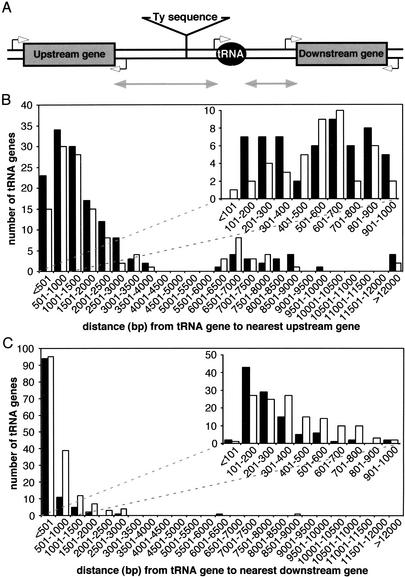

If there is no transcriptional interference between tRNA genes and adjacent pol II-transcribed genes, there should be no orientation bias in the genome. Analysis of the promoter orientations, expression levels, and transcriptional initiation rates at tRNA loci, however, provides additional evidence supporting the inhibition of upstream pol II promoters by adjacent pol III promoters. The generic genomic tRNA locus (Fig. 6A) contains the tRNA gene, upstream and downstream non-Ty ORFs, and may or may not contain Ty sequence. Sixty-seven percent of tRNA genes have Ty sequence between them and the nearest upstream or downstream non-Ty ORFs. We analyzed the transcriptional orientations of the adjacent upstream and downstream non-Ty ORFs relative to their associated tRNA genes genome-wide (Fig. 6B,C). The upstream and downstream non-Ty ORFs may be transcribed in either the same direction as the tRNA gene or the opposite transcriptional direction as the tRNA gene. The latter results in divergent transcription for upstream non-Ty ORFs and convergent transcription for downstream non-Ty ORFs. For all 274 tRNA loci, 55% of upstream non-Ty ORFs are divergently transcribed with the tRNA gene, whereas 42% of downstream non-Ty ORFs are transcribed in the same direction as the tRNA gene. These two transcriptional orientation combinations are relevant to the issue of tRNA position effect because they place the adjacent non-Ty gene promoter closest to the tRNA gene promoter, generating the conformations that could lead to tRNA position effects. To identify tRNA loci possessing maximal tRNA position effect conformations (i.e., genes that are actually immediately adjacent to and within a few hundred base pairs of a tRNA gene), we examined the distance distribution (includes all Ty sequences) of the adjacent non-Ty ORFs with the above promoter orientations for the upstream (Fig. 6B) and downstream (Fig. 6C) genes.

Figure 6.

Genomic distribution of the distances from tRNA genes to their nearest neighbor genes. (A) Cartoon of the generic tRNA locus in the yeast genome. The gray double-headed arrows represent the distances from tRNA genes to their nearest (B) upstream and (C) downstream genes. Solid bars represent tRNA genes that are transcribed in the opposite direction as the neighboring gene, and open bars represent tRNA genes that are transcribed in the same direction as the nearby gene. The minor peaks in the distributions for distances >6,000 and 12,000 bp indicate the presence of one or two full-length Ty elements, respectively.

For upstream genes within 400 bp of a tRNA gene there is a modest transcriptional bias toward the inhibitory conformation; 67% are transcribed divergently relative to the tRNA gene, thereby generating the conformation favoring tRNA position effect. Supporting the notion of tRNA position effect in yeast chromosomes, the subset of divergently transcribed genes within 400 bp of a tRNA gene has a lower mean expression level (0.6 copies/cell, Fig. 7A) and transcription initiation rate (data not shown). This subset of genes is transcribed on average 3.5-fold less (P < 0.0001) than the mean of all genes upstream of tRNA genes (2.1 copies/cell), as determined by examination of a transcription database (Holstege et al. 1998). These bioinformatic data indicate the presence of tRNA position effects at the subset of loci very close to tRNA genes; all of these lack interposed Ty sequences. In contrast, the mean expression level for all upstream genes is unaffected by whether or not the flanking genes are separated from the tRNA gene by Ty sequences. Interestingly, the subset of genes within 400 bp upstream and convergently transcribed relative to tRNA genes also has a lower mean expression level (0.6 copies/cell, Fig. 7B) than the mean of all genes upstream of tRNA genes. The latter result should be interpreted with caution because of the small sample number (n = 8 convergently transcribed upstream genes within 400 bp of the tRNA gene).

Figure 7.

Expression level distribution of the genes upstream of tRNA genes. The expression level for each upstream gene is plotted versus the distance between the upstream ORF and the nearby tRNA gene. (A) Expression level versus intergenic distance for divergently transcribed genes at tRNA loci lacking (solid circles) and containing (open diamonds) upstream Ty sequences. (B) Expression level versus intergenic distance for convergently transcribed genes at tRNA loci lacking (solid triangles) and containing (open squares) upstream Ty sequences. The black arrow and broken black line indicate a 400-bp distance from the upstream gene to the tRNA gene. The horizontal lines (black for solid and gray for open symbols) and numbers represent the mean expression level for the distances spanned by the lines. Gene expression data is according to the yeast Transcriptome database (Holstege et al. 1998). Intergenic distance measurements were based on the ORF coordinates assigned by SGD and not the start sites of transcription, which remain to be determined for many genes.

For downstream genes within 200 bp of a tRNA gene, there is again a transcriptional bias. The bias, however, is away from the inhibitory conformation; only 38% of downstream genes within 200 bp of a tRNA gene are transcribed in the same transcriptional orientation as the tRNA gene. Also, this subset of genes in the same transcriptional orientation is transcribed on average 1.5-fold less (P = 0.04) than the average of all genes downstream of tRNA genes (data not shown) as determined by examination of a gene expression database (Holstege et al. 1998). Taken together, these findings indicated that tRNA position effects exist at a number of genomic tRNA loci in yeast chromosomes. Transcriptional inhibition of the adjacent upstream genes, however, appears to be more dramatic.

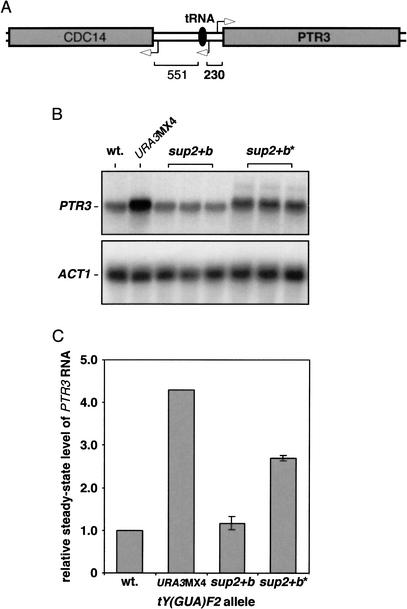

tRNA Position Effects on a Genomic pol II-Transcribed Gene

Examination of the tRNA database allowed us to identify those rare cases in which non-Ty ORFs were located very close to pol III-transcribed genes. One such case is represented by the tY(GUA)F2 locus (Fig. 8A) in which the distance between the 5′-end of the mature tRNATyr and the ATG of the upstream PTR3 gene is merely 230 bp. Whereas PTR3 encodes a plasma membrane sensor of extracellular amino acids (Island et al. 1991; Klasson et al. 1999; Forsberg and Ljungdahl 2001), it has not been reported to function in either pol III transcription or tRNA position effects. To determine whether pol III-transcription of this tRNA gene interferes with the expression of the adjacent PTR3 gene in vivo, we engineered several congenic strains containing various alleles at the tY(GUA)F2 locus. The wild-type tY(GUA)F2 gene (wt) was replaced using a homologous recombination strategy with one of three alleles: (1) a complete gene substitution _tY(GUA)F2_Δ::Ca_URA3_MX4 allele (_URA3_MX4); (2) the tY(GUA)F2-sup2+b allele (sup2+b); or (3) the transcriptionally inactive tY(GUA)F2-sup2+b(G56) allele (sup2+b*). Total RNA was isolated from several isolates for each of the strains containing the above chromosomal tY(GUA)F2 alleles and subjected to quantitative RNA blot analysis using _PTR3_- and _ACT1_-specific probes (Fig. 8B). In cells containing the _URA3_MX4 allele, the steady-state level of PTR3 RNA was found to be more than fourfold higher relative to the level of PTR3 RNA observed in the presence of the wild-type or the sup2+b alleles. Moreover, the presence of a transcriptionally inactive tRNA gene, the sup2+b* allele, stimulated the steady-state level of PTR3 gene expression >2.5 fold (P < 0.0001) relative to that measured in the presence of a transcriptionally active tRNA gene, the wild-type, or the sup2+b alleles. PTR3 expression in the strain containing the _URA3_MX4 allele is possibly the highest because the presence of the pol II-transcribed _URA3_MX4 cassette might physically recruit the RNA pol II to the locus. These results directly demonstrate that tRNA position effects occur in at least one native yeast locus.

Figure 8.

Effect of a native chromosomal tRNA gene on PTR3 expression. (A) Cartoon of the tY(GUA)F2 locus on chromosome VI. Open arrowheads indicate the transcriptional orientation, and the distance between the tRNA gene and the flanking non-Ty ORFs is given in base pairs. (B) RNA blot analysis of cells containing various chromosomal alleles of the tY(GUA)F2 tRNA gene. The level of PTR3 to ACT1 RNA was determined for each sample. (C) PTR3 levels in the presence of no tRNA gene, an actively transcribed tRNA gene and a transcriptionally inactive tRNA gene are relative to those in the presence of the wild-type tRNA gene, _URA3_MX4, sup2+b and sup2+b* relative to wt. (* indicates the presence of the G56 mutation in sup2+b).

DISCUSSION

Effect of Ty1 insertions on Adjacent pol III Transcription

Because Ty elements target their integration to noncoding regions, it is reasonable to suggest that the reason for this is to minimize deleterious effects on the host cell (Boeke and Devine 1998). One way of doing so is to target integration upstream of pol III-transcribed genes or to telomeres and silent mating loci; these regions are known to contain relatively few genes and for their repressive (silencing) effects. Ty1 elements are commonly found inserted upstream of tRNA genes and other genes transcribed by RNA polymerase III. Surprisingly, however, their effect on tRNA gene transcriptional activity has never been directly evaluated. Possibly, this is because tRNA promoter elements are internal, and it is widely assumed that sequences external to the tRNA gene will have little impact on transcriptional activity, in spite of evidence to the contrary (Kinsey and Sandmeyer 1991; Hull et al. 1994; Kendall et al. 2000). Also, it is technically difficult to measure the transcriptional activity of individual tRNA genes because most are repeated. The latter problem can be overcome by carefully marking the pol III-transcribed gene of interest, U6 and SUP2 (Kinsey and Sandmeyer 1991; Chalker and Sandmeyer 1993).

Twelve different insertions, reflecting the common insertion sites upstream of two pol III-transcribed genes were studied, including both orientations of the Ty1 relative to the target gene. This revealed that the U6 gene was relatively unaffected by the presence of a nearby Ty1 element, perhaps because the native U6 gene already contains a Ty1 LTR within its 5′ flanking region (Brow and Guthrie 1990). Two of 4 insertions evaluated, however, showed a significant (P < 0.05) increase in sup2+b tRNA transcript abundance, in one case four times that observed in the absence of the Ty1 element. It is formally possible that the increased transcription results from insertion of DNA and not from the Ty1 sequence itself. Significant inhibitory effects on transcription were not observed for any insertion. Analysis of the tRNA gene database shows that 33 tRNA genes in strain S288C are as closely linked to Ty1 elements as are the insertions that stimulate tRNA transcription. Therefore it is possible that a significant fraction of total tRNA gene expression is attributable to adjacent Ty1 elements. Furthermore, because Ty1 LTRs (delta elements) are found upstream of 67% of tRNA genes, and these solo LTRs can recombine with full-length elements, it is possible that Ty1 to solo LTR recombination could be a significant force in modulating tRNA expression levels as cellular needs for tRNAs change in evolution.

Effect of tRNA Genes on Ty1 Transcript Abundance

Just as Ty1 elements affect tRNA transcription, active tRNA genes can affect Ty1 promoters. We show here that the Ty1 promoter is subject to such effects, but that they affect only divergently transcribed elements, and the maximal effect on transcript levels is a threefold reduction. Our current data for tRNA position effects on Ty1 insertions agree well with those reported for ς and Ty3 (Kinsey and Sandmeyer 1991; Hull et al. 1994). Whereas the initial isolation of Ty1-neo insertions depended on selection for G418-resistant yeast, we cannot rule out the possibility that the data for the Ty1 elements analyzed in this study may under-represent the extent of tRNA position effects on Ty1 elements. Examination of the tRNA database shows that ∼36% of the Ty1s in the genome are suitably oriented and close enough to a tRNA gene to have their transcription affected in this way. An interesting corollary to this type of regulation, which depends on the transcriptional activity of the tRNA gene, is that any cellular state, such as stationary phase, which interferes with tRNA transcription (Tower and Sollner Webb 1988), might well have the opposite effect on the transcription of suitably positioned Ty1 elements. Along these lines, we have searched for temporal and functional commonalities among the upstream genes within 400 bp of tRNA genes. By our analysis, this subset of genes does not appear to cluster by any recognizably similar function, pathway, or expression profile.

tRNA Gene Database Allows a Genome-Wide Look at Ty1 Integration Windows

We have described a database of tRNA genes that can be used to study the relationships between those genes, Ty1 elements, and neighboring non-Ty ORFs. Using the database, we have calculated the mean distance between the tRNA gene boundaries and their neighboring genes. At the upstream boundary of tRNA genes, there is a remarkably large distance (2,330 bp) to the nearest non-Ty1 genes, relative to the distance from the downstream boundary (560 bp) or to the genome-wide inter-ORF distance (480 bp). To determine whether this long 5′-intergenic interval exists in the absence of Ty elements, we examined this distance after deleting all full-length Ty elements (1,310 bp) or all vestiges of annotated Ty sequences (1,010 bp) and found it was still modestly longer than the control distances. These facts indicate that the native yeast genome structure has evolved to put more DNA between tRNA genes and ORFs, possibly to buffer the consequences of tRNA position effect.

Transfer RNA Position Effect: Extent of the Effect and Possible Functions

We have described a database of tRNA genes that can be used to study the relationships between those genes, Ty1 elements, and neighboring pol II-transcribed genes. Examination of this database allowed us to examine the relative orientations of the pol II-transcribed genes flanking tRNA genes to seek evidence for or against position effects of tRNA genes on the genes flanking them. The null hypothesis that there are no position effects on adjacent genes would predict no bias in the orientation of flanking pol II-transcribed genes relative to tRNA genes, when one focuses on the subset of very closely spaced genes. We found a strong deviation from randomness in the intergenic window upstream of tRNA genes (Figs. 5B and 6B). Unexpectedly, we observed an over-representation of genes divergently transcribed relative to the tRNA gene. Consistent with the action of a tRNA position effect, we observed that the mean expression level and transcription initiation rate for the divergently transcribed genes was 3.5-fold less than control genes. Why might such a position be beneficial to this subset of genes? This subset of genes might represent genes that function best at very low levels, or perhaps these genes are derepressed specifically when tRNA genes are at their lowest expression level.

Finally, in this paper we present the first direct evidence that tRNA position effect can influence the expression of a chromosomal gene, the PTR3 gene. Although the effect is modest, it is reproducible. Extrapolation of this result to the entire genome indicates that as many as 12 genes in the yeast genome are down-regulated by tRNA position effects by 3.5-fold or more, and there may be many more affected to a lesser extent.

METHODS

Strains and Media

All strains used in this study are described below. Media were prepared as described (Sherman et al. 1986).

Targeting Assay and Plasmids

The Ty1 donor plasmid, pSD530, consists of a _neo_-marked Gal–Ty1 element in a pRS316 (URA3 CEN6) plasmid backbone lacking the bla gene (Devine and Boeke 1996). Growth of the yeast carrying similar Gal–Ty1 constructs on galactose has been used to induce Ty1 transposition 20- to 100-fold (Boeke et al. 1985, 1988). The neo marker within the Ty1 element confers G418 resistance to yeast cells harboring newly transposed Ty1-neo elements (Boeke et al. 1988). Therefore, after induction and subsequent loss of the donor plasmid, cells that are auxotrophic for uracil and G418-resistant have undergone transposition.

The target plasmids used here, pDLC356 and pDLC605, respectively, consist of the sup2+b or U6mg target genes and flanking genomic sequence in a high copy, _bla_- and _HIS3_-marked, shuttle vector (Chalker and Sandmeyer 1992, 1993). These targets contain pol III-transcribed genes that were modified in subtle ways to allow their products to be distinguished from their endogenous wild-type counterparts. Because the donor plasmid contains Ty1-neo (KanR) and the target plasmid contains the bla gene (AmpR), KanR/AmpR clones arise only by transposition of Ty1-neo into the target plasmid. Therefore, transposition events into either of the target plasmids can be rescued by transformation into Escherichia coli and identified by selection on medium containing ampicillin and kanamycin.

The donor strain, ySD10, was described previously (Devine and Boeke 1996) as YPH499 (MAT a _ura3_-_52 trp1_Δ_63 his3_Δ_200 lys2_-_801 ade2_-101 leu2_Δ_1) (Sikorski and Hieter 1989) containing pSD530 (Devine and Boeke 1996). Each of the target plasmids was then transformed into ySD10 by the lithium acetate method (Gietz et al. 1992) and carried through the transposition assay detailed below.

Approximately 30 independent transformants for each target plasmid were patched onto SC medium lacking histidine and uracil (SC-His-Ura) with 2% glucose (selection for both plasmids) and incubated at 30°C for 2 d. Yeast patches were then replica-plated onto SC-His-Ura with 2% galactose (induces Gal–Ty1 expression and transposition) and incubated at 22°C for 4 d. Patches were replica-plated onto SC-His-Ura with 2% glucose (represses Gal–Ty1 transposition) and incubated at 30°C for 2 d. The donor plasmid was shuffled out by growth on YPD medium at 30°C overnight followed by growth on SC-His containing 1 g/L of 5-fluoro-orotic acid (5-FOA) (Boeke et al. 1984) with 2% glucose at 30°C for 2 d. Finally, patches were replica-plated onto YPD medium containing 0.5 mg/L of G418 (selects for Ty1-neo transposition events) and incubated at 30°C for 1–2 d.

Recombinant target plasmids containing T1-neo insertions were recovered into E. coli by isolating total DNA from yeast patches using the glass bead-phenol method (Kaiser et al. 1994) followed by electroporation of DH10β cells using a Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) electroporation apparatus. Individual Ty1 insertions were mapped by sequencing and labeled a–h (U6mg) and t–x (sup2+b).

The sup2+b(G56) box B mutations were constructed as follows in the pDLC356 target plasmid derivatives containing individual Ty1-neo transposition events. A 1.9-kb _Bst_E II_–Mlu_I fragment from pDLC565, containing the mutated box B promoter element of the sup2+b tRNA gene, (Chalker and Sandmeyer 1992, 1993) was ligated to both the 4.9-kb _Sal_I –_Bst_E II fragment and the 7.1-kb _Mlu_I–_Sal_I fragment of Ty1-neo insertion t to yield the t* mutant. After digestion with _Mlu_I and partial digestion with _Bst_E II, the 1.9-kb _Bst_E II –_Mlu_I fragments of insertions w and x, were replaced with that of pDLC565 (Chalker and Sandmeyer 1992) to generate the w* and x* mutants, respectively.

Generation of Strains With Various tY(GUA)F2 Alleles

In the parent strain, BY4741 (MAT ahis3_Δ_1 leu2_Δ_0 met15_Δ_0 ura3_Δ_0) (Brachmann et al. 1998), the tY(GUA)F2 gene was first replaced with the Ca_URA3_MX4 cassette (Goldstein and McCusker 1999) by homologous recombination generating a _tY(GUA)F2_Δ::Ca_URA3_MX4 allele. In the resulting strain, the Ca_URA3_MX4 cassette was then replaced with the sup2+b and the sup2+b(G56) alleles of the tRNATyr by homologous recombination to generate the tY(GUA)F2-sup2+b and the tY(GUA)F2-sup2+b(G56) alleles, respectively. All gene replacements in the resulting strains were verified by PCR and by sequencing across all of the recombination junctions.

RNA Isolation and Blot Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from several independent yeast transformants. Yeast cultures were grown at 30°C to an OD600 of 0.7–1.0 in SC-His with 2% glucose. Thirty milliliters of culture was used for total RNA isolation, and 30 ml was used for total DNA isolation. Total RNA was extracted by hot acid phenol (Collart and Oliviero 1993), denatured by formaldehyde and/or formamide, and fractionated by denaturing gel electrophoresis as described below.

For quantification of low molecular weight RNAs, U6mg, U14, and sup2+b total RNA (10 μg) was boiled in sample buffer (85% deionized formamide, 9 mM EDTA, and 0.1% xylene cyanol) and iced before loading onto 10% polyacrylamide, 8 M urea denaturing gels in 1X TTE (90 mM Tris base, 29 mM Taurine and 0.5 mM EDTA) running buffer. The denaturing gels were run at 23 V/cm for 4.5 h. RNA was then stained with ethidium bromide to examine its integrity and to position the rRNA molecular weight markers before being electrophoretically transferred to Gene Screen Plus filters as described by the manufacturer (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA). After transfer, the RNA was fixed by UV crosslinking. Membranes were prehybridized at 42°C with hybridization solution (5X SSPE, 5X Denhardt's solution, 5% dextran sulfate-Na+ (500 kD), 0.1% SDS, and 50% deionized formamide). _U6mg_-specific (5′-CCTTATGCAGGGGAACTG-3′), _U14_-specific (5′-CCGAGAGTACTAACGATGGGTTCGTAAGCGTACTCC-3′), and sup2+_b_-specific (5′-GATTTCGTAGGTTACCTGATAAAT TACAG-3′) oligonucleotides were 5′-end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and purified over G25 Sephadex spin columns. Filter-bound RNAs were hybridized at 25°C in hybridization solution for at least 12 h to 30 pmoles. 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probes mixed with 2.5 mg of boiled sheared herring sperm DNA. After hybridization, filters were washed twice for 20 min at 25°C with 1X SSPE, 1X SSPE + 1% SDS and 0.1X SSPE + 0.1% SDS and exposed to a Molecular Dynamics phosphoimager screen.

For quantification of higher molecular weight RNAs, ACT1, PTR3, and Ty1-neo, 20 μg total RNA was boiled in sample buffer (55% deionized formamide, 1X MOPS buffer, pH 7.0, 5% formaldehyde, 8 mM EDTA) and 0.1% bromophenol blue) and iced before loading onto 1% agarose, 1X MOPS buffer, pH 7.0 (40 mM MOPS, 10 mM sodium acetate, and 1 mM EDTA) and 2% formaldehyde gels. The gels were run in 1X MOPS buffer at ∼6 V/cm for 4 h. RNA was stained with ethidium bromide before being transferred by capillary action to Gene Screen Plus filters as described by the manufacturer (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA). Following transfer, the RNA was fixed by UV crosslinking. Membranes were then prehybridized as indicated previously and then hybridized at 42°C in hybridization solution for at least 12 h to 32P-labeled DNA probes mixed with 2.5 mg boiled sheared herring sperm DNA. _ACT1_-specific (1.2 kb _Bam_HI–_Hin_dIII fragment of pΔ10-AHX3 [Chapman and Boeke 1991]), _PTR3_-specific (1.7 kb intra-ORF PCR product), and _neo_-specific (1.0 kb _Bam_HI fragment (Joyce et al. 1993) of pGH54) DNA probes were internally labeled and purified over G25 Sephadex spin columns. Filters were washed twice for 20 min at 25°C with 2X SSPE, twice at 60°C with 2X SSPE + 2% SDS, and twice at 25°C with 0.2X SSPE and then exposed to a Molecular Dynamics phosphoimager screen for at least 24 h. Quantitation of the relative steady-state transcripts was done using ImageQuant v1.11 (Molecular Dynamics) and Microsoft Excel software.

Relative Plasmid Copy Number

The relative copy number of the various _U6mg_- and sup2+_b_-containing plasmids was determined by DNA blot analysis with _bla_- and _ACT1_-specific probes used to detect plasmid and yeast genomic DNA, respectively. Total yeast DNA was isolated as described (Boeke et al. 1985) from 30-mL aliquots of the same cultures used for RNA isolation. The genomic DNA samples were digested with _Bam_HI and _Xba_I and fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis. The DNA fragments were transferred by capillary action to Gene Screen Plus membranes as described by the manufacturer (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA). Hybridization was analyzed using a Molecular Dynamics phosphoimager. The ratio of _bla_- to _ACT1_-specific hybridization of different samples provided a measure of the relative plasmid copy number present in transformed populations. These ratios were used to normalize the relative measurements of U6mg, sup2+b, and Ty1-neo transcripts for gene dosage.

Sequencing

The insertion sites of Ty1-neo recombinants were sequenced by extending primers homologous to the subterminal regions of the Ty1-neo outward into the adjacent sequences. A single recombinant clone was selected from each patch to ensure that each recombinant sequenced represented an independent transposition event. Ty1-neo sequencing primers were JB939 (5′-CCTTAGAAGTAACCGAAGCAC-3′) and JB940 (5′-GATCTATTACATTATGGGTG-3′). PCR products spanning the homologous recombination junctions of at the various _tY(GUA)F2_-allele loci were sequenced using primer JB3286 (5′-GTGATTGTTGTTCTAGTCGCTTGC-3′).

tRNA Gene Loci Database

Data pertaining to all annotated tRNA loci were extracted from the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) at http://genome-www.stanford.edu/Saccharomyces/ and the yeast Transcriptome database at http://web.wi.mit.edu/young/expression/ (Holstege et al. 1998) and reassembled into a flat-file tRNA- and Ty-centered database using Microsoft Access and Excel. The tRNA gene, flanking gene, and Ty database is accessible at http://www.bs.jhmi.edu/MBG/BoekeLab/Boeke_Lab_Homepage, Supplements to Publications. The coordinates and transcriptional orientation of each tRNA gene are given as well as the coordinates, orientations, and available expression levels of the non-Ty ORFs that flank the tRNA gene. Moreover, the coordinates and orientations of annotated Ty sequences, LTRs and full-length Tys (Kim et al. 1998) are listed with their associated tRNA gene. Distance measurements were made using the annotated gene coordinates, which are actually the ORF coordinates. Therefore, the actual distance between transcription start sites and therefore, promoters, is modestly overestimated for divergently and convergently transcribed genes.

Several (86) ORFs annotated as hypothetical ORFs were disallowed during the construction of this database because they lack homologs in yeast, worms, or humans according to BLAST searches conducted through the SGD website or any evidence supporting their identity as genes. Forty-five ORFs were disallowed because they were in fact discovered to consist entirely of Ty sequence. Of the remaining 41 ORFs, 20 were disallowed because they encoded polypeptides less than 200 codons long and lacked serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) tags (Velculescu et al. 1995) and were absent from the Transcriptome data set (Holstege et al. 1998). Seventeen were disallowed because they encoded polypeptides <200 codons long. Four were disallowed because they contained internal tRNA genes, and one was disallowed because it lacked a SAGE tag and was absent from the Transcriptome data set.

Calculations

The mean genome-wide inter-ORF distance excluding telomeric regions (genome) was calculated to be 480 bp long as follows. Using the annotated gene coordinates from SGD (http://genome-www.stanford.edu/Saccharomyces/), we designated the first and last named genes as the ends of each chromosome to minimize the bias imposed by the long, gene-poor telomeric regions. This crude method, however, by no means designates precise telomere boundaries. The total base pairs in these “telomereless” segments for the 16 yeast chromosomes was then summed. The number of bp for all of the ORFs in these telomereless segments was summed as well. Subtracting the number of base pairs for the ORFs from the total number of base pairs in the genome gives the number of base pairs for the inter-ORF sequence in the telomere-free genome. The number of intergenic regions for the telomere-free genome corresponds to the number of ORFs (ORFs disallowed in our data set were excluded here as well) less 16 (one for each chromosome because the chromosomes begin and end with ORFs). Therefore, dividing the number of base pairs for the inter-ORF sequence by the number of inter-ORF regions yields the mean length of the intergenic regions in the telomere-free genome. Note that this estimate of inter-ORF length is actually inflated by the fact that tRNA genes and their flanking regions were not deleted before this analysis.

Probability (P) values were determined by two-tailed _t_-test analysis using Microsoft Excel.

WEB SITE REFERENCES

http://genome-www.stanford.edu/Saccharomyces/; Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD).

http://web.wi.mit.edu/young/expression/; Young Lab Home Page (Transcriptome database).

http://www.bs.jhmi.edu/MBG/BoekeLab/Boeke_Lab_Homepage; this manuscript (tRNA gene, flanking gene and Ty database).

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Boeke laboratory for helpful discussions and reagents. We also thank Suzanne Sandmeyer and John McCusker for generous gifts of plasmids and Brendan Cormack for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM36481 to J.D.B.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

E-MAIL jboeke@jhmi.edu; FAX (410) 614-2987.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.612203.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allison D.S., Goh, S.H., and Hall, B.D. 1983. The promoter sequence of a yeast tRNAtyr gene. Cell 34**:** 655-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeke J.D. and Devine, S.E. 1998. Yeast retrotransposons: Finding a nice quiet neighborhood. Cell 93**:** 1087-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeke J.D., Sandmeyer, S.B., et al. 1991. Yeast transposable elements. In The molecular and cellular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces (ed. J.R. Broach), pp. 193–261. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 4.Boeke J.D., LaCroute, F., and Fink, G.R. 1984. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol. Gen. Genet. 197**:** 345-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boeke J.D., Garfinkel, D.J., Styles, C.A., and Fink, G.R. 1985. Ty elements transpose through an RNA intermediate. Cell 40**:** 491-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boeke J.D., Xu, H., and Fink, G.R. 1988. A general method for the chromosomal amplification of genes in yeast. Science 239**:** 280-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brachmann C.B., Davies, A., Cost, G.J., Caputo, E., Li, J., Hieter, P., and Boeke, J.D. 1998. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: A useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14**:** 114-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brow D.A. and Guthrie, C. 1990. Transcription of a yeast U6 snRNA gene requires a polymerase III promoter element in a novel position. Genes & Dev. 4**:** 1345-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalker D.L. and Sandmeyer, S.B. 1992. Ty3 integrates within the region of RNA polymerase III transcription initiation. Genes & Dev. 6**:** 117-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.___, 1993. Sites of RNA polymerase III transcription initiation and Ty3 integration at the U6 gene are positioned by the TATA box. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90**:** 4927-4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman K.B. and Boeke, J.D. 1991. Isolation and characterization of the gene encoding yeast debranching enzyme. Cell 65**:** 483-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collart M.A., Oliviero, S., et al. 1993. Preparation of yeast RNA. In Current protocols in molecular biology (ed. F.M. Ausubel), pp. 13.12.11–13.12.15. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY.

- 13.Devine S.E. and Boeke, J.D. 1996. Integration of the yeast retrotransposon Ty1 is targeted to regions upstream of genes transcribed by RNA polymerase III. Genes & Dev. 10**:** 620-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forsberg H. and Ljungdahl, P.O. 2001. Sensors of extracellular nutrients in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 40**:** 91-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaisne M., Becam, A.M., Verdiere, J., and Herbert, C.J. 1999. A “natural” mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains derived from S288c affects the complex regulatory gene HAP1 (CYP1). Curr. Genet. 36**:** 195-200.. 195.htm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gietz D., St. Jean, A., Woods, R.A., and Schiestl, R.H. 1992. Improved method for high efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 20**:** 1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein A.L. and McCusker, J.H. 1999. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15**:** 1541-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison D.A., Geyer, P.K., Spana, C., and Corces, V.G. 1989. The gypsy retrotransposon of Drosophila melanogaster: Mechanisms of mutagenesis and interaction with the suppressor of Hairy-wing locus. Dev. Genet. 10**:** 239-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holstege F.C., Jennings, E.G., Wyrick, J.J., Lee, T.I., Hengartner, C.J., Green, M.R., Golub, T.R., Lander, E.S., and Young, R.A. 1998. Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell 95**:** 717-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hull M., Erickson, J., Johnston, M., and Engelke, D. 1994. tRNA genes as transcriptional control elements. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14**:** 1266-1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Island M.D., Perry, J.R., Naider, F., and Becker, J.M. 1991. Isolation and characterization of S. cerevisiae mutants deficient in amino acid-inducible peptide transport. Curr. Genet. 20**:** 457-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji H., Moore, D.P., Blomberg, M.A., Braiterman, L.T., Voytas, D.F., Natsoulis, G., and Boeke, J.D. 1993. Hotspots for unselected Ty1 transposition events on yeast chromosome III are near tRNA genes and LTR sequences. Cell 73**:** 1007-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joyce K.A., Atkinson, A.E., Bermudez, I., Beadle, D.J., and King, L.A. 1993. Synthesis of functional GABAA receptors in stable insect cell lines. FEBS Lett. 335**:** 61-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser C.S., Michaelis, S., and Mitchell, A., 1994. Methods in yeast genetics: A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 25.Kendall A., Hull, M.W., Bertrand, E., Good, P.D., Singer, R.H., and Engelke, D.R. 2000. A CBF5 mutation that disrupts nucleolar localization of early tRNA biosynthesis in yeast also suppresses tRNA gene-mediated transcriptional silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97**:** 13108-13113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J.M., Vanguri, S., Boeke, J.D., Gabriel, A., and Voytas, D.F. 1998. Transposable elements and genome organization: A comprehensive survey of retrotransposons revealed by the complete Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome sequence. Genome Res. 8**:** 464-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinsey P.T. and Sandmeyer, S.B. 1991. Adjacent pol II and pol III promoters: Transcription of the yeast retrotransposon Ty3 and a target tRNA gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 19**:** 1317-1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klasson H., Fink, G.R., and Ljungdahl, P.O. 1999. Ssy1p and Ptr3p are plasma membrane components of a yeast system that senses extracellular amino acids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19**:** 5405-5416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi K., Nakahori, Y., Miyake, M., Matsumura, K., Kondo-Iida, E., Nomura, Y., Segawa, M., Yoshioka, M., Saito, K., Osawa, M., et al. 1998. An ancient retrotransposal insertion causes Fukuyama-type congenital muscular dystrophy. Nature 394**:** 388-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morgan H.D., Sutherland, H.G., Martin, D.I., and Whitelaw, E. 1999. Epigenetic inheritance at the agouti locus in the mouse. Nat. Genet. 23**:** 314-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roeder G.S., Farabaugh, P.J., Chaleff, D.T., and Fink, G.R. 1980. The origins of gene instability in yeast. Science 209**:** 1375-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherman F., Fink, G.R., and Hicks, J.B., 1986. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 33.Sikorski R.S. and Hieter, P. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122**:** 19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tower J. and Sollner-Webb, B. 1988. Polymerase III transcription factor B activity is reduced in extracts of growth-restricted cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8**:** 1001-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velculescu V.E., Zhang, L., Vogelstein, B., and Kinzler, K.W. 1995. Serial analysis of gene expression. Science 270**:** 484-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou S., Ke, N., Kim, J.M., and Voytas, D.F. 1996. The Saccharomyces retrotransposon Ty5 integrates preferentially into regions of silent chromatin at the telomeres and mating loci. Genes & Dev. 10**:** 634-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]