Dynamins and BAR Proteins—Safeguards against Cancer (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2017 May 17.

Abstract

Dynamins and BAR proteins are crucial in a wide variety of cellular processes for their ability to mediate membrane remodeling, such as membrane curvature and membrane fission and fusion. In this review, we highlight dynamins and BAR proteins and the cellular mechanisms that are involved in the initiation and progression of cancer. We specifically discuss the roles of these proteins in endocytosis, endo-lysosomal trafficking, autophagy, and apoptosis as these processes are all tightly linked to membrane remodeling and cancer.

Keywords: cancer, dynamin, endophilin, Drp1, Mfn, Opa, BAR domain, membrane fission and fusion

I. Introduction

Dynamins and members of the BAR protein family (“BAR proteins”) mediate membrane remodeling during fundamental cellular processes, such as synaptic vesicle recycling, mitochondrial fragmentation, ER fusion, and downregulation of cell surface receptors.1–3 Dynamins are atypical GTPases broadly implicated in membrane fission and fusion events in the cell.1,3 Dynamin, the founding member of this superfamily, is crucial for endocytosis, synaptic membrane recycling, and membrane trafficking within the cell.4 Dynamin assembles into polymers on the necks of budding membranes in cells and has been shown to undergo GTP-dependent conformational changes that lead to membrane fission in vitro.5–10 This led to the model that dynamin pinches off vesicles by wrapping around and constricting the necks of budding vesicles.11,12 Additional dynamin family members have been implicated in a variety of fundamental cellular processes, including mitochondrial fission and fusion, antiviral activity, plant cell plate formation, and chloroplast biogenesis.1,3,13,14 Among these proteins, self-assembly, oligomerization into ordered structures, and GTPase activity are common characteristics and, for the majority, essential for their functions.

BAR proteins are major contributors to membrane remodeling events in the cell. They are also involved in the regulation of the actin network, cell migration, T-tubule formation, cell motility, and neuromorphogenesis. Depending on the shape of the BAR domain dimer, BAR proteins sense and induce either positive (N- and F(FCH)-BAR proteins)15–20 or negative curvature [I(inverse)-BAR proteins].21–23 BAR domains bind the membrane via electrostatic interactions with lipid head groups. N-BAR proteins contain an amphipathic helix in their N-terminus (hence the name N-BAR), which inserts into the lipid bilayer and may play a role in curvature sensing.17,24 N-BAR proteins, like endophilin and amphiphysin, promote high curvatures, like the highly constricted necks of clathrin-coated pits15,17,19,20 while F-BAR proteins, like syndapin, CIP4 and FBP17, have been shown to stabilize more shallow membrane deformations.16,18,25

II. Endocytosis and intracellular signaling

Endocytic internalization and endo-lysosomal trafficking of cell-surface receptors, like EGFR and VEGFR, are crucial events in the intracellular signaling pathways that regulate cell growth and proliferation. If interrupted, these may lead to carcinogenesis, which is why proteins controlling these pathways are of great interest in the effort to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of cancer pathogenesis and identify novel modes of prevention.

Evidence is emerging that expression of the ubiquitous isoform of dynamin, dynamin 2, may provide a useful tool for the prognosis of some cancers.26 One prospective role of dynamin in cancer cells is downregulation of receptors like EGFR at the plasma membrane through clathrin-mediated endocytosis.27 Several groups have associated increased levels of EGFR with cancer cell growth.26–28 Internalization and subsequent downregulation of EGFR leads to decreased phosphorylation of ERK.29,30 Phosphorylation of ERK is generally associated with uncontrolled cell growth in numerous cancers.31 Hence, one possible pathway to regulate ERK phosphorylation is through dynamin 2-dependent internalization of EGFR. Therefore, dynamin 2 may play a role in carcinogenesis by controlling cell signaling pathways involved in cell growth and proliferation. It has also been shown that in cervical cancer cells, low levels of dynamin 2 correlate with an increase in matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression, which leads to greater tumor invasion.32 Thus, expression of dynamin 2 may lead to downregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-2, though how this occurs is not yet clear. Overall, the correlation between low levels of dynamin 2 and increased tumorigenesis is likely due to defects in membrane fission.

Dynamin interacts with a number of accessory proteins during clathrin-mediated endocytosis and intracellular membrane trafficking. Major binding partners of dynamin are endophilin, amphiphysin, syndapin (also referred to as pacsin), Cdc42 interacting protein 4 (CIP4), and forming-binding protein 17 (FBP17).2 BAR proteins facilitate dynamin-mediated plasma membrane fission during endocytosis, possibly by generating optimal membrane curvature for dynamin assembly.6,33 In turn, dynamin has been shown to promote the membrane tubulating activity of both F-BAR34 and possibly also N-BAR proteins.35,36 This suggests that a functional partnership between dynamin family members and BAR proteins coordinate membrane curvature with membrane fission and fusion (Fig. 1). The N-BAR proteins amphiphysin and endophilin have been shown to act as tumor suppressors,37,38 while several F-BAR proteins have been linked to cancer progression and metastasis of tumors.37 Endophilin B1 (also referred to as Bax interacting factor 1, Bif-1) has been shown to act as a tumor suppressor by promoting EGFR downregulation.39 Suppression of endophilin B1 in breast cancer cells and in HeLa cells results in a significant delay in EGFR degradation, and endophilin B1 knockdown in lung cancer cells delayed EGFR degradation and sustained receptor activation.39 Suppression of Bif-1 also sustained the activation of Erk1/2, which, as mentioned previously, plays an important role in downstream signaling to promote cell growth. Unlike dynamin 2, endophilin B1 had no effect on internalization of EGFR. Instead, it was found that endophilin B1 knockdown dramatically decreased trafficking of EGFR to the lysosome. Endophilin B1 interacts with a multitude of autophagy and apoptosis players, indicating that it primarily functions downstream of dynamin in intracellular membrane remodeling events in the cell.

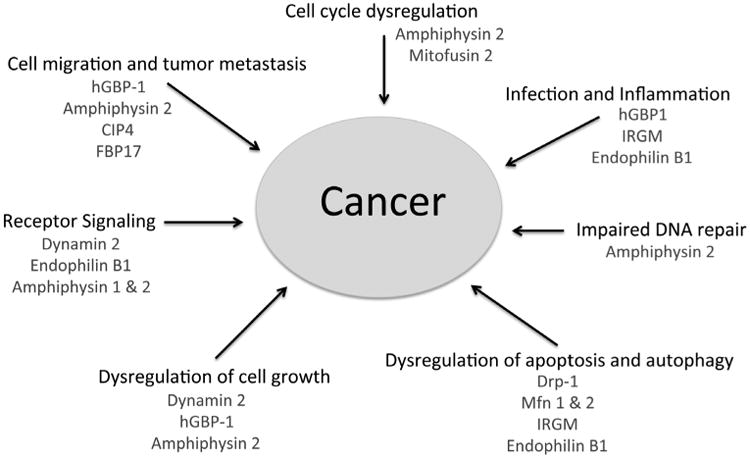

Fig. 1.

Dynamin and BAR proteins regulate pathways involved in carcinogenesis and metastasis. A closer look at cellular mechanisms involved in carcinogenesis and metastasis, namely, receptor signaling, cell migration, cell growth, cell cycle progression, DNA repair, autophagy, and apoptosis, reveal significant involvement of membrane remodeling members of the dynamin and BAR protein families. Although the exact molecular mechanisms controlling their functions in these diverse fundamental processes are not fully elucidated, this indicates that dynamins and BAR proteins may serve important safeguarding roles in the cell's fight against cancer via their membrane remodeling properties.

III. Apoptosis

There is a strong link between apoptosis and cancer.40 Apoptosis acts to suppress carcinogenesis in events of irreparable cellular damage or oncogenic stress, and cancer may develop when the signaling pathways that promote apoptosis are impaired or inhibited. Dynamins associated with mitochondria dynamics are implicated in apoptosis and consequently various forms of cancer. Dynamin family members mediate mitochondrial fission (Drp1) and mitochondrial fusion (Mfn and Opa1).41–43 There is a strong link between mitochondrial shape and apoptosis. For example, Drp1-mediated fission has been shown to facilitate the activity of pro-apoptotic protein Bax, possibly by promoting oligomerization and insertion into the outer mitochondrial membrane, an event required for apoptosis,44 while Mfn- and Opa1-mediated fusion may be inihibitory.44–47 Interestingly, Bax promotes both Drp1 and Mfn activity,44,46,48 which suggests that dynamins and Bax form a functional partnership to coordinate regulation of mitochondrial shape and the apoptosis process. As dynamin family members play important roles in controlling apoptosis, it is no surprise to find they are linked to various cancers. For example, the anticancer drug 4EGI-1 causes apoptosis and mitochondria fragmentation in glioma cells and, in agreement, the cells had decreased levels of Mfn-1 and Opa1 and increased levels of Drp1.49 In addition, blocking mitochondrial fragmentation by Drp1-siRNA prevented the antitumor effects of 4EGI-1.49 Moreover, small human heat-shock protein (HSPB11), which has been associated with brain tumor malignancy, inhibits cell death possibly through enhancing the inhibitory phosphorylation of Drp1, which leads to decreased apoptosis.50 Consistent with this, others have found that the kinase inhibitor tyrphostin A9 induces cancer cell death by Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fragmentation.51 Another antitumor drug, doxorubicin, also induces mitochondrial fission through Drp1 activity.52 In human glioma cells, decreasing the levels of Drp1 with shRNA or with the drug Mdivi-1 induced apoptosis and inhibited tumor growth.53 However, overexpression of Drp1 has also been associated with tumor growth, e.g., the increase in malignant oncocytic thyroid tumors.54 Mfn 2 (which is also known as hyperplasia suppressor gene 2) has been shown to exert antitumor effects in a diverse set of cancer cells (lung, breast, gastric, bladder, liver).55–59 Mfn2 overexpression in bladder carcinoma cells significantly inhibited cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis.58 Significant downregulation of Mfn2 was also observed in liver cancer cells and overexpression of Mfn2 inhibited proliferation of these cells and induced apoptosis by increasing the level of caspase-3.59

Endophilin B1 is also involved in regulation of mitochondrial dynamics, and thus plays a key role in apoptosis.60 Endophilin B1 translocates to the mitochondria during the apoptosis process and has been suggested to play a role in Bax oligomerization at sites of mitochondrial fission.61 The exact nature of the relationship between dynamins, endophilin B1, and Bax is yet unclear. Loss of endophilin B1 leads to suppression of Bax activation and inhibition of apoptosis.62 This effect was shown to be BAR domain-dependent, which emphasizes the role of membrane remodeling in the function of endophilin B1. Interestingly, Bax promotes en-dophilin B1 oligomerization and the formation of MVB-like structures via endophilin B1-me-diated tubulation and vesiculation.63 This further indicates a functional partnership between apoptosis proteins and membrane remodeling members of the dynamins and BAR protein families. In all, these studies show that the roles of dynamin family member Drp1, Mitofusin and Opa1, and endophilin B1 in cancer are linked to their ability to regulate mitochondrial dynamics.

IV. Autophagy

Another intracellular membrane trafficking process that is tightly coupled to cell death and survival is autophagy. Autophagy is an evolutionary conserved lysosomal degradation mechanism used for elimination of damaged organelles, mis-folded proteins, and invasive pathogens.64 As such, it serves a housekeeping function in the cell, as well as provides nutrients during periods of starvation. The autophagy process entails the formation of the autophagosome, a double-membrane vacuole that encapsulates cargo and fuses with the lysosome to mediate cargo degradation and recycling. Autophagy has both tumor-suppressor and tumor-promoting effects. At early stages of cancer, defects in or inhibition of autophagy results in impaired degradation and removal of damaged organelles, unfolded proteins, and reactive oxygen species (ROS), which may result in activation of oncogenic signals. At later stages, cancer cells rely on autophagy for energy and nutrients needed for proliferation, which then functions as a survival factor, promoting cell proliferation and tumor progression.

There is emerging evidence linking endophilin B1 to autophagy.62,65 Knockdown of endophilin B1 caused a decrease in autophagosome formation and an increase in spontaneous tumors in mice.62 Moreover, nutrient starvation caused accumulation of endophilin B1 in the cytoplasm where it co-localized with autophagy proteins Atg5 and LC3.66 Loss of endophilin B1 leads to inhibition of protein degradation.62 Endophilin B1 interacts with a number of key autophagy regulators either directly or indirectly, specifically Atg9,67 Beclin-1, and UVRAG.62,66,68 Atg9 is a transmembrane protein involved in initiation of autophagosome formation.65 Atg9 vesicles are recruited to sites of autophagy to form initial membrane vacuoles.69 The source of these vesicles is still a matter of debate; TGN, Golgi, endosomes, and the plasma membrane have all been suggested to serve as sources for autophago some biogenesis.70,71 It has been shown that Atg9 vesicles fuse with endophilin B1 vesicles at Golgi to generate a cup-shaped membrane structure72,73 that may be the immature autophagosome.66,74 Another endophilin B1 associated autophagy protein is UVRAG.62 Endophilin B1 and UVRAG interact to regulate the function of the Beclin-1-phos-phoinositide 3-kinase class III (PI3KCIII) complex. UVRAG is also involved in endosomal trafficking; it promotes fusion of EGFR endosomes with lysosomes,75 which also requires endophilin B1,39 and promotes the formation of PI(3)P by PI3KCIII.62 UVRAG also facilitates HOPS complex activity, which is required for endosomal fusion and formation of the autophagosome-lysosome.39 Beclin-1 is involved in the regulation of both autophagy and apoptosis. It forms a complex with phosphoinositide 3-kinase class III (also referred to as Vps34), which promotes the generation of PI(3)P, a key signaling molecule in the initiation of autophagy.62 Endophilin B1 promotes formation of the Beclin-1-PI3KCIII complex, while Bcl-2 acts as inhibitor.68 Beclin-1 is mutated in many cancers,65 and loss of Beclin-1 results in PI(3)P mislocalization, abnormal endosomes, and a decrease in EGFR degradation.76 Moreover, endophilin B1 may indeed be crucial in the cell's decision to undergo autophagy or apoptosis; by binding to Bax and promoting a Bax-Bcl-2 interaction, Beclin-1 is released from Bcl-2 and able to initiate autophagy.62

Beclin-1 has been shown to bind specific pathogens (e.g., HIV Nef, herpes vBcl-2, and M2 from influenza), leading to inhibition of autophagy and survival of the invading pathogens.68 This exemplifes the crucial role autophagy plays in the innate immune response to intracellular pathogens. Autophagy involved in removal of pathogens is referred to as “xenophagy” and this process, beyond removal of pathogens, has important effects on the induction and modulation of the inflammatory reaction.77 Not surprisingly, both autophagy and inflammation are involved in several steps of carcinogenesis and cancer progression.77

Members of the dynamin family are involved in the innate immune response to pathogens.78 Immunity-related GTPase M (IRGM) has been shown to inhibit the propagation of a number of different intracellular pathogens.79 IRGM null mice are extremely susceptible to bacterial infection80 and mutations in IRGM are linked to Helicobacter Pylori infection and gastric inflammation, which may ultimately lead to gastric cancer.81 Polymorphism in the IRGM gene has also been linked to Chron's disease, which is often the cause of colorectal cancer.80 IRGM is linked to apoptosis and autophagy, though its exact mechanism or role in these processes is not known. IRGM localizes to mitochondrial membranes where it preferentially binds cardiolipin and participates in the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics, specifically Drp1-mediated fission.82 The only known binding partners of IRGM are endophilin B1 and autophagy proteins Atg5, Atg10, and LC3.79 Thus, all proteins known to interact with IRGM regulate one of the initial steps of autophagosome biogenesis, suggesting that IRGM might contribute to the nucleation and/or the elongation of autophagosome, and that this function is likely crucial for the role of IRGM on infection.79 While IRGM plays a protective role in cancer by promoting autophagy-mediated removal of pathogens that may otherwise give rise to inflammation, it was shown to promote melanoma cell metastasis.83 This effect was shown to be linked to Rac-1-dependent F-actin polymerization, which promotes cell migration and invasion. IRGM was also shown to mediate survival of tumor cells during starvation by promoting autophagy,74 further confirming that autophagy plays dual roles in cancer depending on the stage of disease progression. Human guanylate binding protein 1 (hGBP-1) is another dynamin family member that is known to inhibit infection and propagation of certain pathogens.84,85 It has also been shown to reduce tumor growth via anti-angiogenic effect by regulation of the VGFR pathway, though the exact mechanisms are yet unknown.86

V. Cell Cycle Regulation

Dysregulation of cell cycle progression is a key factor in initial stages of tumorigenesis. Mitofusin 2 and amphiphysin 2 have both been shown to play roles in cell cycle regulation.38,55 In addition to its role in mitochondrial fusion, Mfn 2 has been shown to arrest cell cycle transition from G1 to S phase in gastric tumor cells, though the exact mechanism of Mfn 2 has yet to be determined.57 Dynamin 2 was recently suggested to control c-Myc-dependent cell growth,87 indicating that dynamins may be general regulators of cancer development by controlling cell cycle progression, cell proliferation and growth by controlling upstream signaling pathways.

Amphiphysin 2 (also referred to as Bin1) binds c-Myc and acts as a tumor suppressor by regulating cell cycle control.88 Many tumor cells express mutated forms of Amphiphysin 2 and expression of this protein is reduced or altered in several cancer types, including breast, colon, prostate, lung, liver, and brain cancer.38,89 It is believed that Amphiphysin 2 is involved in safeguarding normal cells from the powerful oncogenic effect of c-Myc overexpression. Knockdown of Amphiphysin 2 in cancer cells caused cell proliferation, survival and increase in invasive capacity. Loss of Amphiphysin 2 in mosaic mice is associated with lung and liver carcinomas. Also, Amphiphysin 2 supports T-cell mediated immune surveillance against tumors. The mechanism by which Amphiphysin 2 promotes tumor suppression is unknown, though it has been shown to promote apoptosis in cancer cells via activation of Bax90 and is known to promote DNA repair by binding and inhibiting poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP1), a key component in base excision repair pathway via its BAR domain.89

VI. The Actin Network and Regulation of Cell Motility

Another role of BAR proteins that links them to cancer is their ability to regulate the actin network, which controls cell migration and cell polarity.37 These functions are crucial at later stages of cancer progression, for tumor invasion and tumor metastasis. Thus, BAR proteins may act to suppress tumorigenesis via participation in endocytosis, apoptosis, and autophagy, or act to promote cancer progression via their roles as regulators of the actin network. CIP4 is an F-BAR protein that plays a role in actin cytoskeleton regulation via its interaction with N-WASP.91 CIP4 and FBP17, another dynamin binding F-BAR protein, are both involved in the formation of invadopodia in breast91 and bladder cancer,92 and high levels of CIP4 correlate with invasive breast cancer.91

Dynamin function during various membrane trafficking events is tightly linked to the actin network.4 Contrary to the anticancer effects of dynamin 2, discussed above, it has also been shown that high expression levels dynamin 2 were associated with poor prognosis of prostate cancer.26 This contrary role of dynamin may be associated with its role in actin polymerization.93,94 In fact, a recent study found that the drug DBHA, which prevents dynamin 2 stimulated GTPase activity, also suppressed migration and invasion of H1299 cancer cells.95 This suggests that inhibition of a dynamin-dependent actin polymerization pathway results in a decreased rate of tumor invasion. In addition, another drug promoting dynamin oligomerization, RyngoR1-23, inhibited cell migration, possibly by preventing dynamin-actin interactions.96

VII. Conclusions

Members of the dynamin and BAR proteins families mediate membrane remodeling in the cell. Evidence is emerging that members of these proteins serve a safeguarding role, protecting the cell against cancer and infection. Remodeling of cellular membranes is a crucial cellular process involved in signaling pathways controlling cell survival and cell death, innate immunity to intracellular pathogens, regulation of cell surface receptors, and the actin network activity. In addition, their roles in membrane trafficking, dynamins, and BAR proteins are also involved in regulation of cell cycle progression, cell growth and proliferation. The exact mechanisms are not known, though the crucial roles of these proteins in fundamental cellular processes urges future investigation into these mechanisms in efforts elucidate new signaling pathways and to identify novel drug targets in the fight against cancer.

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to my dear friend Lee A. Goodglick who is missed every day by his friends and colleagues (JEH). Thanks to Marisa Rubio and Andy Kehr for their comments and careful reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

BAR

BIN/amphiphysin/Rvs

CIP4

Cdc4 interacting protein 4

FBP17

forming-binding protein 17

EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

VGFR

vascular epithelial growth factor receptor

ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma 2

Drp1

dynamin-related protein 1

Mfn

mitofusin

Opa1

optic Atrophy 1

Bax

bcl-2-like protein 4

4EGI-1

α-[2-[4-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-2-thiazolyl]hydrazinylidene]-2-nitro-benzenepropanoic acid

Mdivi-1

mitochondrial division inhibitor 1

MVB

multi-vesicular bodies

ROS

reactive oxygen species

Atg

autophagy associated protein

LC3

microtu-bule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3

UVRAG

UV radiation resistance-associated gene protein

TGN

trans-Golgi network

PI3KCIII

phosphoinositide 3-kinase class III

PI(3)P

phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate

HOPS

homotypic fusion and vacuole protein sorting

IRGM

immunity-related GTPase M

hGBP-1

human guanylate binding protein 1

PARP1

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

N-WASP

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein

DBHA

N'-[4-(dipropylamino)benzylidene]-2-hydroxybenzohydrazide

References

- 1.Praefcke GJ, McMahon HT. The dynamin superfamily: universal membrane tubulation and fission molecules? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:133–47. doi: 10.1038/nrm1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daumke O, Roux A, Haucke V. BAR domain scaffolds in dynamin-mediated membrane fission. Cell. 2014;156:882–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heymann JA, Hinshaw JE. Dynamins at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3427–31. doi: 10.1242/jcs.051714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:857–902. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081307.110540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chappie JS, Mears JA, Fang S, Leonard M, Schmid SL, Milligan RA, Hinshaw JE, Dyda F. A pseudoatomic model of the dynamin polymer identifies a hydrolysis-dependent powerstroke. Cell. 2011;147:209–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sundborger A, Soderblom C, Vorontsova O, Evergren E, Hinshaw JE, Shupliakov O. An endophilin-dynamin complex promotes budding of clathrin-coated vesicles during synaptic vesicle recycling. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:133–43. doi: 10.1242/jcs.072686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sweitzer SM, Hinshaw JE. Dynamin undergoes a GTP-dependent conformational change causing vesiculation. Cell. 1998;93:1021–9. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bashkirov PV, Akimov SA, Evseev AI, Schmid SL, Zimmerberg J, Frolov VA. GTPase cycle of dynamin is coupled to membrane squeeze and release, leading to spontaneous fission. Cell. 2008;135:1276–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morlot S, Galli V, Klein M, Chiaruttini N, Manzi J, Humbert F, Dinis L, Lenz M, Cappello G, Roux A. Membrane shape at the edge of the dynamin helix sets location and duration of the fission reaction. Cell. 2012;151:619–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pucadyil TJ, Schmid SL. Real-time visualization of dynamin-catalyzed membrane fission and vesicle release. Cell. 2008;135:1263–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundborger AC, Hinshaw JE. Regulating dynamin dynamics during endocytosis. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:85. doi: 10.12703/P6-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roux A. Reaching a consensus on the mechanism of dynamin? F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:86. doi: 10.12703/P6-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bui HT, Shaw JM. Dynamin assembly strategies and adaptor proteins in mitochondrial fission. Curr Biol. 2013;23:R891–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman JR, Nunnari J. Mitochondrial form and function. Nature. 2014;505:335–43. doi: 10.1038/nature12985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatia VK, Hatzakis NS, Stamou D. A unifying mechanism accounts for sensing of membrane curvature by BAR domains, amphipathic helices and membrane-anchored proteins. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:381–90. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frost A, Perera R, Roux A, Spasov K, Destaing O, Egelman EH, De Camilli P, Unger VM. Structural basis of membrane invagination by F-BAR domains. Cell. 2008;132:807–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallop JL, Jao CC, Kent HM, Butler PJ, Evans PR, Langen R, McMahon HT. Mechanism of endophilin N-BAR domain-mediated membrane curvature. EMBO J. 2006;25:2898–910. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itoh T, De Camilli P. BAR, F-BAR (EFC) and ENTH/ ANTH domains in the regulation of membrane-cytosol interfaces and membrane curvature. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:897–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masuda M, Takeda S, Sone M, Ohki T, Mori H, Kamioka Y, Mochizuki N. Endophilin BAR domain drives membrane curvature by two newly identifed structure-based mechanisms. EMBO J. 2006;25:2889–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peter BJ, Kent HM, Mills IG, Vallis Y, Butler PJ, Evans PR, McMahon HT. BAR domains as sensors of membrane curvature: the amphiphysin BAR structure. Science. 2004;303:495–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1092586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suetsugu S, Toyooka K, Senju Y. Subcellular membrane curvature mediated by the BAR domain superfamily proteins. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:340–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suetsugu S. The proposed functions of membrane curvatures mediated by the BAR domain superfamily proteins. J Biochem. 2010;148:1–12. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvq049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao H, Pykalainen A, Lappalainen P. I-BAR domain proteins: linking actin and plasma membrane dynamics. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhatia VK, Madsen KL, Bolinger PY, Kunding A, Hede-gard P, Gether U, Stamou D. Amphipathic motifs in BAR domains are essential for membrane curvature sensing. EMBO J. 2009;28:3303–14. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q, Navarro MV, Peng G, Molinelli E, Goh SL, Judson BL, Rajashankar KR, Sondermann H. Molecular mechanism of membrane constriction and tubulation mediated by the F-BAR protein Pacsin/Syndapin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12700–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902974106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu B, Teng LH, Silva SD, Bijian K, Al Bashir S, Jie S, Dolph M, Alaoui-Jamali MA, Bismar TA. The significance of dynamin 2 expression for prostate cancer progression, prognostication, and therapeutic targeting. Cancer Med. 2014;3:14–24. doi: 10.1002/cam4.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gong C, Zhang J, Zhang L, Wang Y, Ma H, Wu W, Cui J, Wang Y, Ren Z. Dynamin2 downregulation delays EGFR endocytic trafficking and promotes EGFR signaling and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:702–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang M, Yin G, Wang F, Liu H, Zhou S, Ni J, Chen C, Zhou Y, Zhao Y. Downregulation of CD9 promotes pancreatic cancer growth and metastasis through upregulation of epidermal growth factor on the cell surface. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:350–8. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson GL, Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science. 2002;29:1911–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1072682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung BM, Tom E, Zutshi N, Bielecki TA, Band V, Band H. Nexus of signaling and endocytosis in oncogenesis driven by non-small cell lung cancer-associated epidermal growth factor receptor mutants. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5:806–23. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i5.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sebolt-Leopold JS. Advances in the development of cancer therapeutics directed against the RAS-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3651–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee YY, Do IG, Park YA, Choi JJ, Song SY, Kim CJ, Kim MK, Song TJ, Park HS, Choi CH, Kim TJ, Kim BG, Lee JW, Bae DS. Low dynamin 2 expression is associated with tumor invasion and metastasis in invasive squamous cell carcinoma of cervix. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:329–35. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.4.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farsad K, Ringstad N, Takei K, Floyd SR, Rose K, De Camilli P. Generation of high curvature membranes mediated by direct endophilin bilayer interactions. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:193–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao Y, Ma Q, Vahedi-Faridi A, Sundborger A, Pechstein A, Puchkov D, Luo L, Shupliakov O, Saenger W, Haucke V. Molecular basis for SH3 domain regulation of F-BAR-mediated membrane deformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8213–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003478107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Z, Chang K, Capraro BR, Zhu C, Hsu CJ, Baumgart T. Intradimer/Intermolecular interactions suggest autoinhibition mechanism in endophilin A1. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:4557–64. doi: 10.1021/ja411607b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farsad K, Slepnev V, Ochoa G, Daniell L, Haucke V, De Camilli P. A putative role for intramolecular regulatory mechanisms in the adaptor function of amphiphysin in endocytosis. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:787–96. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00306-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y, Aardema J, Misra A, Corey SJ. BAR proteins in cancer and blood disorders. Int J Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;3:198–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lundgaard GL, Daniels NE, Pyndiah S, Cassimere EK, Ahmed KM, Rodrigue A, Kihara D, Post CB, Sakamuro D. Identifcation of a novel effector domain of BIN1 for cancer suppression. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:2992–3001. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Runkle KB, Meyerkord CL, Desai NV, Takahashi Y, Wang HG. Bif-1 suppresses breast cancer cell migration by promoting EGFR endocytic degradation. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012;13:956–66. doi: 10.4161/cbt.20951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowe SW, Lin AW. Apoptosis in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:485–95. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan DC. Dissecting mitochondrial fusion. Dev Cell. 2006;11:592–4. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen H, Detmer SA, Ewald AJ, Griffn EE, Fraser SE, Chan DC. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:189–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frank S, Gaume B, Bergmann-Leitner ES, Leitner WW, Robert EG, Catez F, Smith CL, Youle RJ. The role of dynamin-related protein 1, a mediator of mitochondrial fission, in apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2001;1:515–25. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karbowski M, Lee YJ, Gaume B, Jeong SY, Frank S, Nechushtan A, Santel A, Fuller M, Smith CL, Youle RJ. Spatial and temporal association of Bax with mitochondrial fission sites, Drp1, and Mfn2 during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:931–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frezza C, Cipolat S, Martins de Brito O, Micaroni M, Beznoussenko GV, Rudka T, Bartoli D, Polishuck RS, Danial NN, De Strooper B, Scorrano L. OPA1 controls apoptotic cristae remodeling independently from mitochondrial fusion. Cell. 2006;126:177–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoppins S, Edlich F, Cleland MM, Banerjee S, McCaffery JM, Youle RJ, Nunnari J. The soluble form of Bax regulates mitochondrial fusion via MFN2 homotypic complexes. Mol Cell. 2011;41:150–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Renault TT, Floros KV, Elkholi R, Corrigan KA, Kushnareva Y, Wieder SY, Lindtner C, Serasinghe MN, Asciolla JJ, Buettner C, Newmeyer DD, Chipuk JE. Mitochondrial shape governs BAX-induced membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2015;57:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu S, Zhou F, Zhang Z, Xing D. Bax is essential for Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission but not for mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization caused by photodynamic therapy. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:530–41. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang X, Dong QF, Li LW, Huo JL, Li PQ, Fei Z, Zhen HN. The cap-translation inhibitor 4EGI-1 induces mitochondrial dysfunction via regulation of mitochondrial dynamic proteins in human glioma U251 cells. Neurochem Int. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2015.07.019. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turi Z, Hocsak E, Racz B, Szabo A, Balogh A, Sumegi B, Gallyas FJ. Role of mitochondrial network stabilisation by a human small heat shock protein in tumour malignancy. J Cancer. 2015;6:470–6. doi: 10.7150/jca.11494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park SJ, Park YJ, Shin JH, Kim ES, Hwang JJ, Jin DH, Kim JC, Cho DH. A receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, Tyrphostin A9 induces cancer cell death through Drp1 dependent mitochondria fragmentation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;408:465–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang JX, Zhang XJ, Feng C, Sun T, Wang K, Wang Y, Zhou LY, Li PF. MicroRNA-532-3p regulates mitochondrial fission through targeting apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain in doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1677. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xie Q, Wu Q, Horbinski CM, Flavahan WA, Yang K, Zhou W, Dombrowski SM, Huang Z, Fang X, Shi Y, Ferguson AN, Kashatus DF, Bao S, Rich JN. Mitochondrial control by DRP1 in brain tumor initiating cells. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:501–10. doi: 10.1038/nn.3960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferreira-da-Silva A, Valacca C, Rios E, Populo H, Soares P, Sobrinho-Simoes M, Scorrano L, Maximo V, Campello S. Mitochondrial dynamics protein Drp1 is overexpressed in oncocytic thyroid tumors and regulates cancer cell migration. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lou Y, Li R, Liu J, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Jin B, Liu Y, Wang Z, Zhong H, Wen S, Han B. Mitofusin-2 over-expresses and leads to dysregulation of cell cycle and cell invasion in lung adenocarcinoma. Med Oncol. 2015;32:132. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma L, Liu Y, Geng C, Qi X, Jiang J. Estrogen receptor beta inhibits estradiol-induced proliferation and migration of MCF-7 cells through regulation of mitofusin 2. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:1993–2000. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang GE, Jin HL, Lin XK, Chen C, Liu XS, Zhang Q, Yu JR. Anti-tumor effects of mfn2 in gastric cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:13005–21. doi: 10.3390/ijms140713005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jin B, Fu G, Pan H, Cheng X, Zhou L, Lv J, Chen G, Zheng S. Anti-tumour effcacy of mitofusin-2 in urinary bladder carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2011;28(1):S373–80. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9662-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang W, Lu J, Zhu F, Wei J, Jia C, Zhang Y, Zhou L, Xie H, Zheng S. Pro-apoptotic and anti-proliferative effects of mitofusin-2 via Bax signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Med Oncol. 2012;29:70–6. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9779-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karbowski M, Jeong SY, Youle RJ. Endophilin B1 is required for the maintenance of mitochondrial morphology. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:1027–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suen DF, Norris KL, Youle RJ. Mitochondrial dynamics and apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1577–90. doi: 10.1101/gad.1658508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takahashi Y, Coppola D, Matsushita N, Cualing HD, Sun M, Sato Y, Liang C, Jung JU, Cheng JQ, Mule JJ, Pledger WJ, Wang HG. Bif-1 interacts with Beclin 1 through UVRAG and regulates autophagy and tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1142–51. doi: 10.1038/ncb1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rostovtseva TK, Boukari H, Antignani A, Shiu B, Baner-jee S, Neutzner A, Youle RJ. Bax activates endophilin B1 oligomerization and lipid membrane vesiculation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34390–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu B, Wen X, Cheng Y. Survival or death: disequilibrating the oncogenic and tumor suppressive autophagy in cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e892. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toton E, Lisiak N, Sawicka P, Rybczynska M. Beclin-1 and its role as a target for anticancer therapy. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;65:459–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Takahashi Y, Meyerkord CL, Wang HG. Bif-1/endophilin B1: a candidate for crescent driving force in autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:947–55. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Takahashi Y, Meyerkord CL, Wang HG. BARgaining membranes for autophagosome formation: Regulation of autophagy and tumorigenesis by Bif-1/Endophilin B1. Autophagy. 2008;4:121–4. doi: 10.4161/auto.5265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, Tang D. The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:571–80. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.He S, Ni D, Ma B, Lee JH, Zhang T, Ghozalli I, Pirooz SD, Zhao Z, Bharatham N, Li B, Oh S, Lee WH, Taka-hashi Y, Wang HG, Minassian A, Feng P, Deretic V, Pepperkok R, Tagaya M, Yoon HS, Liang C. PtdIns(3) P-bound UVRAG coordinates Golgi-ER retrograde and Atg9 transport by differential interactions with the ER tether and the beclin 1 complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:1206–19. doi: 10.1038/ncb2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Puri C, Renna M, Bento CF, Moreau K, Rubinsztein DC. ATG16L1 meets ATG9 in recycling endosomes: additional roles for the plasma membrane and endocytosis in autophagosome biogenesis. Autophagy. 2014;10:182–4. doi: 10.4161/auto.27174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shibutani ST, Yoshimori T. A current perspective of autophagosome biogenesis. Cell Res. 2014;24:58–68. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takahashi Y, Meyerkord CL, Hori T, Runkle K, Fox TE, Kester M, Loughran TP, Wang HG. Bif-1 regulates Atg9 trafficking by mediating the fission of Golgi membranes during autophagy. Autophagy. 2011;7:61–73. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.1.14015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zavodszky E, Vicinanza M, Rubinsztein DC. Biology and trafficking of ATG9 and ATG16L1, two proteins that regulate autophagosome formation. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1988–96. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dong H, Tian L, Li R, Pei C, Fu Y, Dong X, Xia F, Wang C, Li W, Guo X, Gu C, Li B, Liu A, Ren H, Wang C, Xu H. IFNg-induced Irgm promotes tumorigenesis of melanoma via dual regulation of apoptosis and Bif-1-dependent autophagy. Oncogene. 2015 doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.459. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liang C, Lee JS, Inn KS, Gack MU, Li Q, Roberts EA, Vergne I, Deretic V, Feng P, Akazawa C, Jung JU. Beclin1-binding UVRAG targets the class C Vps complex to coordinate autophagosome maturation and endocytic trafficking. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:776–87. doi: 10.1038/ncb1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McKnight NC, Zhong Y, Wold MS, Gong S, Phillips GR, Dou Z, Zhao Y, Heintz N, Zong WX, Yue Z. Beclin 1 is required for neuron viability and regulates endosome pathways via the UVRAG-VPS34 complex. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Netea-Maier RT, Plantinga TS, Van De Veerdonk FL, Smit JW, Netea MG. Modulation of inflammation by au-tophagy: consequences for human disease. Autophagy. 2015 doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1071759. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.MacMicking JD. IFN-inducible GTPases and immunity to intracellular pathogens. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:601–9. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Petkova DS, Viret C, Faure M. IRGM in autophagy and viral infections. Front Immunol. 2012;3:426. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brest P, Corcelle EA, Cesaro A, Chargui A, Belaid A, Klionsky DJ, Vouret-Craviari V, Hebuterne X, Hofman P, Mograbi B. Autophagy and Crohn's disease: at the crossroads of infection, inflammation, immunity, and cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10:486–502. doi: 10.2174/156652410791608252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Burada F, Plantinga TS, Ioana M, Rosentul D, Angelescu C, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Saftoiu A. IRGM gene polymorphisms and risk of gastric cancer. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:360–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2012.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Singh SB, Ornatowski W, Vergne I, Naylor J, Delgado M, Roberts E, Ponpuak M, Master S, Pilli M, White E, Komatsu M, Deretic V. Human IRGM regulates autophagy and cell-autonomous immunity functions through mitochondria. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:1154–65. doi: 10.1038/ncb2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tian L, Li L, Xing W, Li R, Pei C, Dong X, Fu Y, Gu C, Guo X, Jia Y, Wang G, Wang J, Li B, Ren H, Xu H. IRGM1 enhances B16 melanoma cell metastasis through PI3K-Rac1 mediated epithelial mesenchymal transition. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12357. doi: 10.1038/srep12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Itsui Y, Sakamoto N, Kakinuma S, Nakagawa M, Sekine-Osajima Y, Tasaka-Fujita M, Nishimura-Sakurai Y, Suda G, Karakama Y, Mishima K, Yamamoto M, Watanabe T, Ueyama M, Funaoka Y, Azuma S, Watanabe M. Antiviral effects of the interferon-induced protein guanylate binding protein 1 and its interaction with the hepatitis C virus NS5B protein. Hepatology. 2009;50:1727–37. doi: 10.1002/hep.23195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tietzel I, El-Haibi C, Carabeo RA. Human guanylate binding proteins potentiate the anti-chlamydia effects of interferon-gamma. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lipnik K, Naschberger E, Gonin-Laurent N, Kodajova P, Petznek H, Rungaldier S, Astigiano S, Ferrini S, Sturzl M, Hohenadl C. Interferon gamma-induced human guanylate binding protein 1 inhibits mammary tumor growth in mice. Mol Med. 2010;16:177–87. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Willinger T, Staron M, Ferguson SM, De Camilli P, Flavell RA. Dynamin 2-dependent endocytosis sustains T-cell receptor signaling and drives metabolic repro-gramming in T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:4423–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504279112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Elliott K, Sakamuro D, Basu A, Du W, Wunner W, Staller P, Gaubatz S, Zhang H, Prochownik E, Eilers M, Prendergast GC. Bin1 functionally interacts with Myc and inhibits cell proliferation via multiple mechanisms. Oncogene. 1999;18:3564–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Prokic I, Cowling BS, Laporte J. Amphiphysin 2 (BIN1) in physiology and diseases. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014;2:453–63. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tanida S, Mizoshita T, Ozeki K, Tsukamoto H, Kami-ya T, Kataoka H, Sakamuro D, Joh T. Mechanisms of cisplatin-induced apoptosis and of cisplatin sensitivity: potential of BIN1 to act as a potent predictor of cisplatin sensitivity in gastric cancer treatment. Int J Surg Oncol. 2012;2012:862879. doi: 10.1155/2012/862879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pichot CS, Arvanitis C, Hartig SM, Jensen SA, Bechill J, Marzouk S, Yu J, Frost JA, Corey SJ. Cdc42-interacting protein 4 promotes breast cancer cell invasion and formation of invadopodia through activation of N-WASp. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8347–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yamamoto H, Sutoh M, Hatakeyama S, Hashimoto Y, Yoneyama T, Koie T, Saitoh H, Yamaya K, Funyu T, Nakamura T, Ohyama C, Tsuboi S. Requirement for FBP17 in invadopodia formation by invasive bladder tumor cells. J Urol. 2011;185:1930–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schafer DA. Coupling actin dynamics and membrane dynamics during endocytosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:76–81. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(01)00297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schafer DA, Weed SA, Binns D, Karginov AV, Parsons JT, Cooper JA. Dynamin2 and cortactin regulate actin assembly and filament organization. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1852–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yamada H, Abe T, Li SA, Tago S, Huang P, Watanabe M, Ikeda S, Ogo N, Asai A, Takei K. N'-[4-(dipropylamino) benzylidene]-2-hydroxybenzohydrazide is a dynamin GTPase inhibitor that suppresses cancer cell migration and invasion by inhibiting actin polymerization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;443:511–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.11.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lees JG, Gorgani NN, Ammit AJ, McCluskey A, Robinson PJ, O'Neill GM. Role of dynamin in elongated cell migration in a 3D matrix. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1853:611–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]