From Krebs to Clinic: Glutamine Metabolism to Cancer Therapy (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2017 Jun 26.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Rev Cancer. 2016 Jul 29;16(10):619–634. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.71

Abstract

The resurgence of research in cancer metabolism has recently broadened interests beyond glucose and the Warburg Effect to other nutrients including glutamine. Because oncogenic alterations of metabolism render cancer cells addicted to nutrients, pathways involved in glycolysis or glutaminolysis could be exploited for therapeutic purposes. In this Review, we provide an updated overview of glutamine metabolism and its involvement in tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo, and explore the recent potential applications of basic science discoveries in the clinical setting.

Introduction

Glucose has been central to the study of cancer metabolism following Otto Warburg’s pioneering work on aerobic glycolysis 1, whereas studies of other nutrients, such as glutamine, have been at the margins of the cancer metabolism literature until recently. Hans Krebs, famed for characterization of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, studied glutamine metabolism in animals in 1935, and documented its importance in organismal homeostasis. Subsequently, the role of glutamine in cell growth and cancer cell biology was slowly appreciated (Figure 1 (Timeline)) and has been a subject of several comprehensive reviews 2, 3. Given the many energy-generating and biosynthetic roles glutamine plays in growing cells, which are discussed and updated in this Review, inhibition of glutaminolysis has the potential to effectively target cancer cells.

Figure 1.

Timeline of key discoveries in mammalian glutamine metabolism and cancer

α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; GLUD, glutamate dehydrogenase.

There are nine amino acids (isoleucine, leucine, methionine, valine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, histidine, threonine and lysine) humans cannot synthesize and hence are considered essential amino acids. Five amino acids (alanine, aspartate, asparagine, glutamate, and serine) are believed to be dispensable, because they can be readily synthesized. Glutamine belongs to a group of amino acids that are conditionally essential, particularly under catabolic stressed conditions such as the post-operative period, injury, or sepsis, where glutamine consumption by the kidney, gastrointestinal tract, and immune compartment rise dramatically4. Cells of the intestinal mucosa are particularly dependent on glutamine, and they rapidly undergo necrosis after glutamine depletion 4. These observations mirror the dependence of growing cancer cells on glutamine 5, with some cancer cells dying rapidly if glutamine is deprived 6.

Circulating glutamine is the most abundant amino acid (~500 μM)7, making up over 20% of the free amino acid pool in blood and 40% in muscle8. While diet can serve as a source of glutamine from digested foods absorbed through the small intestine, the endothelium of which retains up to 30% of dietary glutamine, glutamine can be considered a non-essential amino acid at the organismal level owing to the fact that the muscle and other organs synthesize glutamine as a scavenger for ammonia produced from the metabolism of other amino acids 9. In fact, glutamine is held at a fairly constant level in the circulation, presumably due to _de novo_synthesis and release from the skeletal muscle, lung, and adipose tissue 3, 10, 11. The kidney releases ammonia from glutamine to maintain acid-base homeostasis 12, and the liver and kidney eliminate excess nitrogen in the form of urea from glutamine via the urea cycle, another process first identified by Krebs 13. In rapidly dividing cells such as lymphocytes, enterocytes of the small intestine, and especially cancer cells, glutamine is avidly consumed and utilized for both energy generation and as a source of carbon and nitrogen for biomass accumulation14.

Glutamine Metabolism

The maintenance of high levels of glutamine in the blood provides a ready source of carbon and nitrogen to support biosynthesis, energetics and cellular homeostasis that cancer cells may exploit to drive tumor growth. Glutamine is transported into cells through one of many transporters 15, such as the heavily-studied solute carrier family 1 neutral amino acid transporter member 5 (SLC1A5; also known as ASCT2; Figure 2) 16, and can then be used for biosynthesis or exported back out of the cell by antiporters in exchange for other amino acids such as leucine through the L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1, a heterodimer of SLC7A5 and SLC3A2)) antiporter 17. Glutamine-derived glutamate can be also exchanged through the xCT (a heterodimer of SLC7A11 and SLC3A2; Figure 3) antiporter for cystine, which is quickly reduced to cysteine inside the cell18.

Figure 2. Major metabolic and biosynthetic fates of glutamine.

Glutamine enters the mammalian cell through transporters such as SLC1A5 (also known as ASCT2) 15. Glutamine itself can contribute to nucleotide biosynthesis and uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) synthesis for support of protein folding and trafficking 210, or is converted to glutamate by glutaminase (GLS or GLS2) 28. Glutamate can contribute to the synthesis of glutathione 110, and has many other metabolic fates in the cell that impact on several inborn errors of metabolism, which were recently reviewed 211. Glutamate is converted to α-ketoglutarate (αKG) through one of two sets of enzymes, glutamate dehydrogenase (GLUD1 or GLUD2, henceforth referred to collectively as GLUD) or aminotransferases 30. While the byproduct of GLUD is NH4+, the byproduct of aminotransferase reactions is other amino acids. Note that aminotransferases may be present either in the cytoplasm or the mitochondria. α-ketoglutarate enters the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and can provide energy for the cell. Malate exiting the TCA cycle can produce pyruvate and NADPH for reducing equivalents 31, and oxaloacetate (OAA) can be converted to aspartate to support nucleotide synthesis 34. These two pathways are illustrated in more detail in Figure 4. Alternately, α-KG can proceed backwards through the TCA cycle, in a process called reductive carboxylation (RC) to produce citrate, which supports synthesis of acetyl-CoA and lipids 87.

Figure 3. Glutamine control of amino acid pools and ROS.

Glutamate acts as a nitrogen donor for the transamination involved in the production of ‘dispensable amino acids’ alanine, aspartate, and serine through the actions of glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT), glutamic pyruvate transaminase (GPT) and phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1), respectively. Glutamine can also act as a nitrogen donor for asparagine through asparagine synthetase (ASNS). In a reaction independent of transamination, proline can be synthesized by conversion of glutamate to pyrroline-5-carboxylate (P5C) by pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase (P5CS; also known as aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family member A1, (ALDH18A1)) and subsequently to proline by pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 1 (PYCR1) and PYCR2. Glutamine also contributes to the tripeptide glutathione (composed of glutamate, cysteine and glycine), which neutralizes the ROS H2O2 110. The first step in glutathione synthesis is the condensation of glutamate and cysteine through glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL; not shown in the figure). Glutamine input directly contributes to the availability of cysteine and glycine for production of glutathione. Glutamate can be exchanged for cystine (which is quickly reduced to cysteine inside the cell) through the xCT antiporter (a heterodimer of SLC7A11 and SCL3A2), which has been shown to be important in a variety of cancers and has been considered as a drug target 18, 212. Glycine is next added by glutathione synthetase (GSS; not shown in the figure). Additionally, glutamate can contribute to glycine through transamination by PSAT1 into phosphoserine (pSer) and α-ketoglutarate (αKG) and subsequent conversion to glycine through serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT; not shown in the figure) as part of the one-carbon metabolism pathway, which has been shown in numerous studies to be critical in cancer metabolism and is also reviewed in this Focus Issue by Dr. Karen Vousden 139, 140, 213. GLS, kidney-type glutaminase; GLS2, liver-type glutaminase; GLUD, glutamate dehydrogenase; OAA, oxaloacetate.

In addition to transport, cancer cells can acquire glutamine through breaking down macromolecules under nutrient-deprived conditions. Macropinocytosis, which can play a role in normal biology and is active in most non-cancerous cells 19, can be stimulated by oncogenic RAS 20, allowing cancer cells to scavenge extracellular proteins, which are then degraded to amino acids including glutamine, supplying metabolites for survival 21, 22. This process must be tightly controlled 23, as excess RAS can hyperactivate macropinocytosis to lead to cell death, in a process previously misidentified as autophagic cell death 24. The complex relationship between glutamine metabolism and autophagy is discussed below, but it is notable that some RAS-transformed cancer cells derive glutamine and maintain metabolic flux from autophagic degradation of intracellular proteins 25, 26.

Energy generation

Upon entry into the cell via transporters, glutamine is converted by mitochondrial glutaminases to an ammonium ion and glutamate, which is further catabolized through two different pathways (Figure 2). Interestingly, despite its importance, the mitochondrial glutamine transporter has not yet been definitively identified and characterized27. Glutaminase, which as Krebs determined exists in multiple tissue-specific versions, is encoded by two genes in mammals, kidney-type glutaminase (GLS) and liver-type glutaminase (GLS2) 28, 29. Glutamate can then be converted to α-ketoglutarate, which enters the TCA cycle to generate ATP through production of NADH and FADH2. As Lehninger first described 30, glutamate can be converted to α-ketoglutarate either by glutamate dehydrogenase (encoded by the highly-conserved and more broadly-expressed GLUD1 or the hominoid-specific GLUD2, henceforth collectively termed GLUD), which is an ammonia-releasing process, or by a number of non-ammonia producing aminotransferases, which transfer nitrogen from glutamate to produce another amino acid and α-ketoglutarate 30. Proliferating cells including cancer cells and activated lymphocytes utilize glutamine as an energy-generating substrate31–33. In some tumor cells, a portion of metabolized glutamine is converted to pyruvate through the malic enzymes31, 34, but as discussed below, this is likely not an energy-generating process. Notably, and as will be expanded on below, proliferating cells incorporate a majority of the glutamine they utilize for biomass for building protein and nucleotides 35.

Glutamine enzymes in cancer

The expression of enzymes involved in glutamine metabolism varies widely in cancers and is impacted by tissue of origin and oncogenotypes, which rewire glutamine metabolism for energy generation and stress suppression. Of the two glutaminase enzymes 28,GLS is more broadly expressed in normal tissue and thought to play a critical role in many cancers, while GLS2 expression is restricted primarily to the liver, brain, pituitary gland, and pancreas36. Alternative splicing adds further complexity, as GLS pre-mRNA is spliced into either glutaminase C (GAC) or kidney-type glutaminase (KGA) isoforms37–39. The two GLS isoforms and GLS2 also differ in their regulation and activity. GLS but not GLS2 is inhibited by its product glutamate, while GLS2 but not GLS is activated by its product ammonia_in vitro_ 28, 29. Although both GLS and GLS2 are activated by inorganic phosphate, GLS (and particularly GAC) shows a much larger increase in catalysis in the presence of inorganic phosphate 37. Sirtuin 5 (SIRT5), which can be overexpressed in lung cancer 40, can desuccinylate GLS to suppress its enzymatic activity 41, while SIRT3 can deacetylate GLS2 to promote its increased activity with caloric restriction 42. Phosphate, acetyl-coA, and succinyl-CoA availability are impacted by nutrient uptake and metabolism, suggesting that GLS and GLS2 activity may be responsive to the metabolic state of the cell. Additionally, GLS is regulated through transcription 43, RNA-binding protein regulation of alternative splicing44–47, post-transcriptional regulation by miRNAs and pH stabilization of the GLS mRNA 48, 49, and protein degradation via the anaphase-promoting complex(APC)-CDH1 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex 50, 51.

Expression of GAC, which is more active than KGA, is increased in several cancer types, suggesting that GLS alternative splicing may play an important role in the presumed higher glutaminolytic flux in cancer 18, 37, 45, 47, 52–54. In contrast, the role of GLS2 in cancer seems more complex. Silenced by promoter methylation in liver cancer, colorectal cancer and glioblastoma, re-expression of GLS2 has been shown to have tumor suppressor activities in colony formation assays 55–59. In fact, a recent studied showed that GLS2, in a non-metabolic function, sequesters the small GTPase RAC1 to suppress metastasis 60. However, GLS2 seems to support the growth and promote radiation resistance in some cancer types 61. Indeed, GLS2 is induced by the tumor suppressor p53 and related proteins p63 and p73 55, 56, 62, 63, suggesting perhaps that it functions in resistance to radiation, or is important in cancers that still possess wild-type p53. Additionally, GLS2 is a critical downstream target of the N-MYC oncogene in neuroblastoma 64, 65. The context dependent role of GLS2 in cancer clearly merits further study.

Once produced via glutaminase, glutamate is further converted to α-ketoglutarate through one of two mechanisms 30 (Figure 2). GLUD catalyzes the reversible deamination of glutamate to produce α-ketoglutarate and release ammonium. This reaction is at near-thermodynamic equilibrium in the liver, and so GLUD operates in both directions in this organ 66, but in cancer is thought to chiefly operate in the direction of α-ketoglutarate 67, and so GLUD activity will be discussed in this context for the purpose of this Review. Like GLS, GLUD is controlled through post-translational modifications and allosteric regulation. It is activated by ADP and inactivated by GTP, palmitoyl-CoA, and SIRT4-dependent ADP-ribosylation 68–71. Interestingly, GLUD is also allosterically activated by leucine, and mTOR (which itself is activated by leucine availability17, 72) can promote GLUD activity by suppressing SIRT4 expression 73,74. These observations suggest that a low energetic state might induce GLUD allosterically via ADP to increase ATP production, while high leucine availability could also induce GLUD allosterically and through mTOR suppression of SIRT4.

Aminotransferases are enzymes which convert glutamate to α-ketoglutarate without producing ammonia (Figure 3). Two of these enzymes, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase are well known in clinical medicine as ‘liver enzymes’ or markers of liver pathology 75, 76. Glutamic-pyruvate transaminase (GPT, also known as alanine aminotransferase) transfers nitrogen from glutamate to pyruvate to make alanine and α-ketoglutarate, and is encoded in humans by GPT(cytoplasmic isoform) and GPT2 (mitochondrial isoform). Glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT, also known as aspartate aminotransferase), which transfers nitrogen from glutamate to oxaloacetate to produce aspartate and α-ketoglutarate, is encoded for in humans by_GOT1_ (cytoplasmic isoform) and GOT2(mitochondrial isoform). Phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1), as part of the serine biosynthesis pathway transfers nitrogen from glutamate to 3-phosphohydroxy-pyruvate to make phosphoserine and α-ketoglutarate. Different aminotransferases show different tissue distribution: aspartate aminotransferase activity is high across most tissues, while alanine aminotransferase activity is highest in the liver, although expression is still fairly universal 36, 77,78. However, aminotransferases such as PSAT1 may be inappropriately expressed in tumors 79. The potential importance of which enzyme converts glutamate to α-ketoglutarate in cancer cell physiology is discussed below.

Glutamine and ATP: What Else?

Amino acid production

The nitrogen from glutamine supports the levels of many amino acid pools in the cell through the action of aminotransferases 35 (Figure 3). Separate from transamination reactions, carbon and nitrogen from glutamate can be used to produce proline, which plays a key role in the production of the extracellular matrix protein collagen 80 (Figure 3). While proline can be degraded to glutamate 81, the MYC oncoprotein can alter the expression of proline synthesis and degradation enzymes to promote the net synthesis of proline from glutamine-derived glutamate 82. Overall, tracer experiments determined that at least 50% of non-essential amino acids used in protein synthesis by cancer cells in vitro can be directly derived from glutamine16, 83. While various glutamine-derived amino acids contribute to cancer cell survival, recent studies have shown that aspartate biosynthesis, which can depend on both glutamine flux through the TCA cycle and glutamate transamination 84, 85, is especially critical due its key role in both purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis to support cell division 84–86, as discussed in greater detail below.

Reductive carboxylation and fatty acid synthesis

Cancer cells take up large amounts of glucose, but most of this carbon is excreted as lactate rather than metabolized in the TCA cycle 7, potentially depriving the cells of the citrate derived from the TCA cycle that supports fatty acid synthesis (Figure 2). Glutamine metabolism can serve as an alternative source of carbon to the TCA cycle to fuel fatty acid synthesis, through reductive carboxylation, which is a process by which glutamine-derived α-ketoglutarate is reduced through the consumption of NADPH by isocitrate dehydrogenases (IDHs) in the non-canonical reverse reaction to form citrate 87. Reductive carboxylation, the importance of which is still somewhat controversial88, seems to be a major source of carbon for lipid synthesis in cancer cells that are hypoxic, have constitutive hypoxia-inducible factor-α (HIFα) stabilization or have mitochondrial defects 89–92. Although the contribution of reductive carboxylation to lipid formation from glutamine remains unclear due to the possibility of isotope exchange 88, studies suggest that reductive carboxylation occurs in vivo and can support lipogenesis for tumor growth and progression 89, 93,94 and can also control the levels of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) 95.

Protein synthesis, trafficking, and stress pathway suppression

Several of the metabolic fates of glutamine directly support protein synthesis and trafficking, and suppress stress responses carried out by two related pathways, the integrated stress response (ISR) and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathway (Figure 4). Glutamine input thus supports the overall amino acids pools of the cell to suppress the ISR, which is otherwise activated under amino acid deprivation by the amino acid-sensing kinase GCN2 (encoded by EIF2αK4) (Figure 3). Phosphorylation of eIF2α by GCN2 inhibits general cap-dependent protein synthesis via the ISR but induces cap-independent synthesis of the activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), which in turn induces a pathway to increase transcription of ER-associated chaperones, halt cap-dependent translation, and eventually result in cell death 96. Glutamine deprivation can directly lead to uncharged tRNAs, or lead to a depletion of downstream products such as asparagine to indirectly lead to uncharged tRNAs, all of which can activate GCN2 and induce ATF4 translation. Suppression of the ISR by glutamine input has been shown to be critical for survival of several cancer cell and tumor types including neuroblastoma and breast cancer65, 97,98. It was also observed that GCN2 is activated in mice in response to treatment with asparaginase99, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and may deplete serum asparagine and glutamine 100–102.

Figure 4. Control by glutamine of the integrated stress response, protein folding and trafficking, and ER stress.

GCN2, a serine-threonine kinase with a regulatory domain that is structurally similar to histidine-tRNA synthetase, is allosterically activated by uncharged tRNAs with amino acid deprivation (including glutamine deprivation) and in turn activates the integrated stress response (ISR) 96, 214,215. Glutamine can suppress GCN2 activation through its contribution to amino acid pools by aminotransferases 65, 97–99. To control endoplasmic reticulum (ER) homeostasis, glutamine supports protein folding and trafficking through its contribution to uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) as part of the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway. Glutamine is the substrate for glutamine fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase (GFAT), which is the key rate-limiting enzyme in the hexosamine pathway, and the downstream product UDP-GlcNAc is a substrate for O-linked glycosylation through O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (OGT). Thus, glutamine deprivation can lead to improper protein folding and chaperoning and ER stress 210. A key output of both the ISR and of ER stress is activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), which is induced via cap-independent translation downstream of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) phosphorylation by GCN2 or other kinases 96. α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; GLS, kidney-type glutaminase; GLS2, liver-type glutaminase.

Glutamine also contributes to the synthesis of uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) as part of the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway, which is required for glycosylation, proper ER-Golgi trafficking, and suppression of the ER stress pathway, also upstream of ATF4 induction (Figure 4). Aberrant expression and activity of O-Linked β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (OGT), which links UDP-GlcNAc to proteins, was shown to be critical for the survival and progression of breast cancer, prostate cancer, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia103–105. Thus, glutamine input directly maintains translation, protein trafficking, and survival through suppression of the ISR and ER stress pathways106, 107.

ROS control: glutathione and reducing equivalents

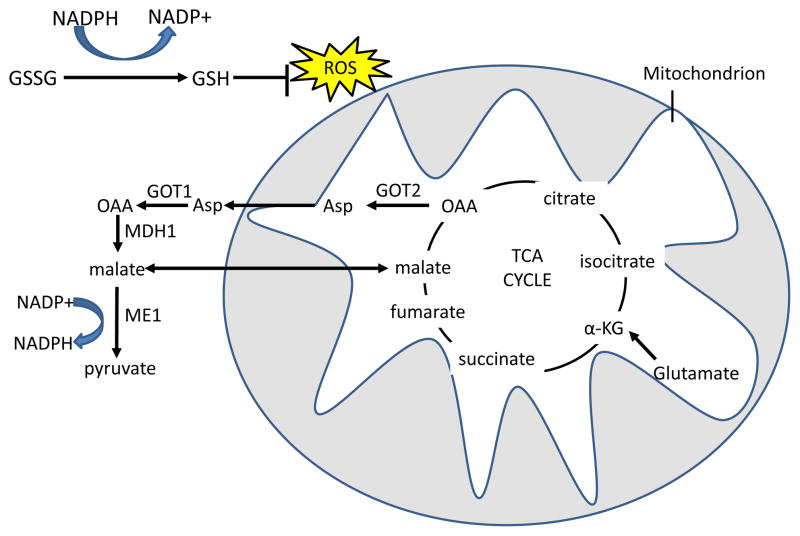

ROS-mediated cell signaling can be pro-tumorigenic when at physiological levels108, but when levels are in excess, ROS can be highly damaging to macromolecules 109. ROS are generated from several sources, including the mitochondrial electron transport chain, which can leak electrons to oxygen to generate superoxide (O2−). Thus, increased glutamine oxidation can correlate with increased ROS production108. However, several glutamine metabolic pathways lead to products that directly control ROS levels; hence, glutamine metabolism is critical for cellular ROS homeostasis. The most well-known pathway in which glutamine controls ROS is through synthesis of glutathione. Glutathione is a tri-peptide (Glu-Cys-Gly) which serves to neutralize peroxide free radicals. It has long been appreciated that glutamine input is the rate-limiting step for glutathione synthesis 110, and as shown in Figure 3, glutamine is directly and indirectly responsible for the other two amino-acid components of glutathione. As glutathione levels are known to correlate with tumorigenesis and drug resistance in cancer 111, a richer understanding of this pathway may contribute to better cancer treatment strategies. In fact, several studies have shown that acute glutamine administration to cancer patients receiving radiation or chemotherapy reduces treatment toxicity through increased glutathione synthesis112, 113. Glutamine also affects ROS homeostasis through production of NADPH via GLUD114, and at least two other related mechanisms 31, 34 where TCA cycle-derived aspartate or malate is exported to the cytoplasm and then converted to pyruvate to produce NADPH through the malic enzymes, provide reducing equivalents for glutathione. Figure 5 details two glutamine-derived pathways, one of which is mediated by oncogenic K-RAS 34.

Figure 5. Glutamine derived TCA cycle intermediates can be used via two pathways to produce NADPH and neutralize ROS through the malic enzyme.

Reduced glutathione (GSH) neutralizes H2O2 with the glutathione peroxidase enzyme, and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) is reduced by NADPH and glutathione reductase to regenerate GSH. In the first pathway, glutamine-derived malate is transported out of the mitochondria, and is converted by malic enzyme 1 (ME1) to pyruvate, reducing one molecule of NADP+ to NADPH. In the malate-aspartate shuttle-related second pathway, found in mutant KRAS-transformed cells, aspartate that is produced from GOT2 mediated transamination of glutamine-derived oxaloacetate (OAA) is transported out of the mitochondria. Aspartate is then converted in the cytosol back to OAA by GOT1 and then to malate by malate dehydrogenase 1 (MDH1), which is in turn processed to pyruvate by ME1 to produce one molecule of NADPH 34. The fate of glutamine-derived pyruvate is similar to glucose-derived pyruvate in that much of it is expelled as lactate31. α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; GOT, glutamic oxaloacetate transaminase.

Regulation of mTOR

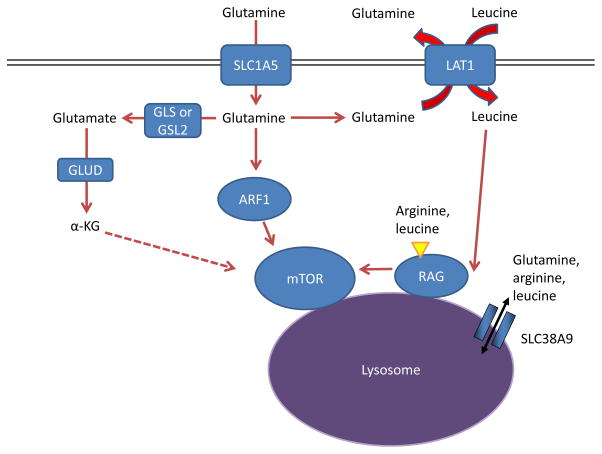

The TOR pathway senses amino acids and broadly promotes biosynthetic pathways such as protein translation and fatty acid synthesis while inhibiting degradative processes like autophagy 115. As such, mTOR activity must be tightly controlled to prevent inappropriate cell growth, and glutamine regulates this activity through several mechanisms (Figure 6). Amino acid availability stimulates mTOR activity independently of the activating mTOR pathway mutations often found in human cancer 115, and thus must be maintained regardless of mutation state. Glutamine and other amino acids that support mTOR activity need not come from amino acid transporters, as macropinocytosis-derived amino acids can also support mTOR activation 23. Conversely, mTOR itself can regulate glutamine metabolism by cell-type specific mechanisms, either by inhibiting expression of mitochondrial SIRT4, thereby relieving repression of GLUD69, 73,116, or by instead inhibiting GLUD expression while upregulating expression of aminotransferases117, as is discussed further below. The important implication of these findings is that, independent of direct mutations of negative regulators of the mTOR pathway itself, such as tuberous sclerosis 1 protein (TSC1; also known as hamartin) and TSC2 (also known as tuberin), increased glutamine uptake and metabolism that is common in many cancers may also strongly stimulate mTOR activity. The regulation of mTOR by amino acid availability, including glutamine, is a rich and evolving field, and more advances will be needed to fully understand this intriguingly intricate process 115.

Figure 6. Glutamine controls mTOR activity.

Amino acids stimulate the mTOR pathway, and amino acid pools rely on glutamine to be maintained. Specifically, arginine and leucine are two amino acids that can together almost fully stimulate mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) through activation of the RAS-related GTPase (RAG) complex, which in turn recruits mTORC1 to the lysosome and stimulates its activity 72, 133, 216. Glutamine can contribute to mTORC1 activation by being exchanged for essential amino acids, including leucine, through the large neutral amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1; a heterodimer of SLC7A5 and SLC3A2) transporter 17. This RAG-dependent regulation of mTOR is likely dependent on the lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9, which transports glutamine, arginine, and leucine as substrates129, 132, 133, as well as the leucine sensor sestrin 2 (not shown in Figure) 217, 218. Although the mechanism is not well understood, α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) may regulate RAGB activity and mTOR activation downstream of glutamine metabolism219. Several RAG-independent pathways of mTOR regulation by glutamine have also been identified. Glutamine promotes mTOR localization to the lysosome (and thus activity) through the RAS-family member ADP ribosylation factor 1 (ARF1) in a poorly understood mechanism, as well as the TTT-RUVBL1/2 complex (not shown in Figure) 128, 130. GLS, kidney-type glutaminase; GLS2, liver-type glutaminase; GLUD, glutamate dehydrogenase.

Nucleotide biosynthesis

Glutamine directly supports the biosynthetic needs for cell growth and division. While carbon from glutamine is used for amino acid and fatty acid synthesis, nitrogen from glutamine contributes directly to both de novo purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis 118. The importance of glutamine as a nitrogen reservoir is underscored by the fact that glutamine-deprived cancer cells undergo cell cycle arrest that cannot be rescued by TCA-cycle intermediates such as oxaloacetate but can be rescued by exogenous nucleotides118, 119. In fact, synthesis of nucleotides from exogenous glutamine has been observed in human primary lung cancer samples cultured ex vivo 120.

Glutamine can also contribute to nucleotide biosynthesis through other pathways. Aspartate derived from glutamine via the TCA cycle and transamination (Figures 2,3) serves as a crucial source of carbon for purine and pyrimidine synthesis 84, 85, and provision of aspartate can rescue cell cycle arrest caused by glutamine deprivation 86. Additionally, glutamine dependent mTOR signaling may activate the enzyme carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 2, aspartate transcarbamylase, and dihydroorotase (CAD), which catalyzes the incorporation of glutamine derived nitrogen into pyrimidine precursors118, 121, 122. It has been suggested that NADPH produced downstream of glutamine metabolism and flux through the malic enzymes can further support nucleotide synthesis 31. Overall, glutamine can support biomass accumulation of fatty acids, amino acids, and nucleotides, by directly contributing carbon and nitrogen, indirectly generating reducing equivalents, and stimulating the signaling pathways that are necessary for their synthesis.

Autophagy and glutamine

Autophagy and glutamine have a complex relationship that mirrors the complexities of autophagy in cancer initiation and progression. The role of autophagy in cancer appears paradoxical: in some settings, it is tumor suppressive, by limiting oxidative stress and chromosomal instability that may lead to oncogenic mutations 123,124, while in other situations, autophagy supports cancer cell survival by providing nutrients and suppressing stress pathways such as p53 125, 126. Thus, autophagy may influence tumor initiation and tumor progression differently, affecting tumor growth in a seemingly contradictory context-dependent manner. Many of the processes impacted by glutamine metabolism suppress autophagy. Glutamine suppresses GCN2 activation and the ISR, which can both otherwise induce autophagy 65, 97, 127. Glutamine also indirectly stimulates mTOR, which in turn suppresses autophagy through a complex mechanism17, 128–134(recently reviewed by Dunlop and Tee 135). Similarly, ROS can induce autophagy as a stress response 136 but is suppressed by glutamine metabolism through production of glutathione and NADPH31, 34, 110. Conversely, generation of ammonia from glutaminolysis could potentially promote autophagy activation in an autocrine and paracrine manner 137, 138. Although increased glutamine metabolism in cancer would suppress ROS levels (through glutathione production) as well as ER stress and promote mTOR activity, ammonia release from glutamine metabolism will vary between cancer types. Glutaminase releases ammonia in catalyzing the reaction of glutamine to glutamate, and some cancers process glutamate to α-ketoglutarate via GLUD (releasing another ammonium ion), while others use transamination, which does not release ammonia, as was first described by Lehninger 30. Similarly, SIRT5 desuccinylates and reduces GLS activity, thus reducing ammonia production and autophagy activation 41. Through the relative contributions of SIRT5 and GLUD versus transamination, one might speculate that ammonia production downstream of glutamine metabolism could ‘tune’ autophagy to the specific needs of the tumor cells to maintain organelle turnover, provide nutrients, and reduce cell stress.

Divergent Paths to α-Ketoglutarate

A perhaps understudied aspect of glutamine metabolism in cancer is the consequence of two divergent pathways that convert glutamate to α-ketoglutarate, and the subsequent fate of the nitrogen derived from glutamate (Figure 7). The different pathways were first identified more than thirty years ago 30, and the field has made much progress on the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of GLUD versus aminotransferase utilization, but not nearly as much progress on the ‘when’ or the ‘why’. Specifically, the field must still address the relative contributions of each pathway to cancer cell physiology, and how the two different pathways are utilized depending on tissue of origin, proliferation state, cell health or stress, stage of tumor evolution, and oncogenotype.

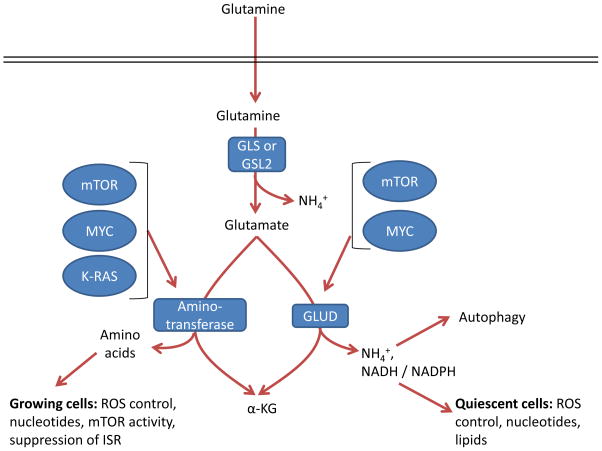

Figure 7. Two roads to α-ketoglutarate.

Glutamate can be converted by one of two different pathways into α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), and the choice of which pathway is influenced both by oncogene input and cell proliferation and metabolic state. GLS, kidney-type glutaminase; GLS2, liver-type glutaminase; GLUD, glutamate dehydrogenase; ISR, integrated stress response; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Reactions via GLUD or aminotransferases result in production of α-ketoglutarate but have different by-products. In addition to α-ketoglutarate and ammonium, GLUD can produce both NADH and NADPH with different kinetics 114, which support the TCA cycle, bioenergetics, control of ROS levels, and lipid synthesis. In contrast, the byproduct of aminotransferases is α-ketoglutarate as well as other amino acids such as serine, alanine, aspartate, and asparagine downstream of aspartate, which contribute to a variety of cell functions such as nucleotide biosynthesis, redox control, and suppression of the ISR 65, 84, 85, 97, 98, 139–141. In breast cancer with genomic amplification of the serine biosynthesis gene phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH), PSAT1 is the major source of glutamine dependent α-ketoglutarate, through transamination,, and breast cancer cells with amplified PHGDH grow poorly after PHGDH depletion compared to those with normal levels142, underscoring the importance of these reactions in certain tumor types. Alanine is a product of transamination that is highly secreted from some tumor types 30, 141, which perhaps may safely dispose of nitrogen without ammonia production. While some tumors are sensitive to the aminotransferase inhibitor aminooxyacetate (AOA) 65, 143, it is a broad-spectrum inhibitor, and so specific inhibition of individual aminotransferases will be required to assess their specific roles in cancer.

The underlying oncogenotype affects these two pathways differentially, which may be related to the metabolic requirements the oncogenes impose on the cells. MYC upregulates both GLUD and aminotransferases 144, and seems to require both pathways, depending on context67, 145. In contrast, oncogenic mutant KRAS activity increases aminotransferases and decreases GLUD mRNA expression 34. The role of mTOR in glutamine metabolism seems highly context and cell-type specific: in mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) and colon and prostate cancer cells, mTOR supports increased activity of GLUD via repression of SIRT4 69, 73, 116, whereas in mouse mammary 3D culture models and human breast cancer, mTOR instead inhibits expression of GLUD while promoting expression of aminotransferases, particularly PSAT1 117. It is notable that mTOR requires constant amino acid input 146, while KRAS drives macropinocytosis 22, and thus, pathway selection of glutamine catabolism by these two pathways may reflect differing metabolic requirements that we do not yet fully appreciate. Nonetheless, these studies do suggest that transformed cells with strong PI3K-AKT-mTOR, KRAS, or MYC pathway activation increase their flux of glutamate to α-ketoglutarate for metabolism and biosynthesis.

Some key differences in the two pathways from glutamate to α-ketoglutarate may warrant further studies. Most noticeably, in addition to ammonia release by GLS, GLUD releases an additional ammonium ion and transamination does not. While ammonia is often thought of as a toxic byproduct, cancers can utilize ammonia to induce autophagy and neutralize intracellular pH 137, 138, 147, and GLUD can also produce NADPH 114 to reduce glutathione and lead to lower levels ROS 114. Together, these pathways could reduce cell stress and promote survival in some cancers 148. GLUD catalyzes a reaction that is reversible; however, the high Km for ammonia limits this reaction to deamination of glutamate in most tissues with the exception of the liver 66, 149. In contrast, aminotransferases are freely reversible, and thus may provide more metabolic plasticity to certain cancer cells that rely on them. Further, GLUD results in disposal of a nitrogen atom in ammonium, while aminotransferase supports a much more biosynthetic phenotype that may better support rapidly growing cancer cells. In fact, a recent study suggests that rapidly-dividing mammary epithelial cells in culture as well as highly proliferative human breast cancers upregulate aminotransferases and downregulate GLUD expression 117. The authors show that growing cells incorporate the nitrogen from glutamine into non-essential amino acids for cell growth, whereas this nitrogen would otherwise be disposed of by GLUD activity117. This further suggests that the utilized pathway from glutamate to α-ketoglutarate is highly dependent on the metabolic, biosynthetic, and stress-reduction needs of the cell.

Oncogenes and Glutamine Metabolism

Glutamine metabolism is upregulated by many oncogenic insults and mutations (Table 1). This section highlights and expands on some of these. The MYC oncogene has perhaps been most associated with upregulated glutamine metabolism. MYC is the third most commonly amplified gene in human cancer 150, and the discovery that MYC-transformed cells become dependent on exogenous glutamine helped to drive a resurgence in the interest in glutamine metabolism 6, 31. MYC was found to upregulate glutamine transporters and induce the expression of GLS at the mRNA and protein level48, 145, and to drive a glutamine-fueled TCA cycle and glutathione production in hypoxia 151. Glutamine in MYC-driven cells can be used for de novo proline synthesis 82 or production of the oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate in breast cancer152, although the latter finding has not been independently corroborated. Infection by adenovirus or Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) both increase MYC expression and glutamine metabolism153, 154, and in the case of KSHV this may be a part of early tumorigenesis that eventually leads to Kaposi’s sarcoma. MYC can also mediate the reprogramming of glutamine metabolism downstream of activation of other oncogenic pathways, including mTOR 155, and crosstalk with HER2 (also known as ERBB2) and the estrogen receptor (ER) in breast cancer 156. All these findings support the notion that glutaminolysis is a major component of MYC-driven oncogenesis in most settings.

Table 1.

Influence of oncogenes and tumor suppressor gene loss on glutamine metabolism

| Oncogenic change | Role in glutamine metabolism |

|---|---|

| MYC upregulation | Upregulates glutamine metabolism enzymes and transporters 6, 31, 48, 145, 177 |

| KRAS mutations | Drives dependence on glutamine metabolism, suppresses GLUD, and drives NADPH via malic enzyme 1 (ME1) 34, 108, 119, 157, 158 |

| HIF1α or HIF2α stabilization | Drives reductive carboxylation of glutamine to citrate for lipid production 89–91 |

| HER2 upregulation | Activates glutamine metabolism through MYC and NF-κB 156, 220 |

| p53, p63, or p73 activity | Activates GLS2 expression 55, 56, 62, 63 |

| JAK2-V617F mutation | Activates GLS and increases glutamine metabolism 221 |

| mTOR upregulation | Promotes glutamine metabolism via induction of MYC155 and GLUD 69, 73 or aminotransferases 117 |

| NRF2 activation | Promotes production of glutathione from glutamine 222 |

| TGFβ-WNT upregulation | Promotes SNAIL and DLX2 activation, which upregulate GLS and activates epithelial-mesenchymal transition183 |

| PKC zeta loss | Stimulates glutamine metabolism through serine synthesis 223 |

| PTEN loss | Decreased GLS ubiquitination 224 |

| RB1 loss | Upregulates GLS and SLC1A5 expression225 |

Oncogenic KRAS-driven transformation induces dependence on glutamine metabolism 108, 119, 157. However, different KRAS mutations can have different effects; for instance, lung cancer cells harboring a KRAS-G12V mutation were much less glutamine dependent than those harboring G12C or G12D mutations, though the reasons for this were not clear 158. In addition to inducing dependence on glutamine driven nucleotide metabolism 119, mutant KRAS can increase dependence on aminotransferases through downregulation of GLUD, and drive increased production of NADPH to regenerate reduced glutathione and control ROS levels34 (Figure 5).

Poor vascularization and hypoxia induce the stabilization of HIF1α or HIF2α 159, which directs glutamine towards biosynthetic fates that do not require oxygen. HIFα stabilization orchestrates a gene expression program that promotes the conversion of glucose to lactate, driving it away from the TCA cycle 159, 160. Decreased glucose entry into the TCA cycle can be compensated for by glutamine fueled production of the TCA cycle intermediate α-ketoglutarate 151. However, this α-ketoglutarate is largely channeled through reductive carboxylation in certain cell types to produce citrate, acetyl-coA, and lipids89–91. By contrast, glutamine is metabolized in human B-cell lymphoma model cells cultured in hypoxia largely via forward TCA cycling, with only a minor amount undergoing reductive carboxylation 151. HIFα stabilization can occur independently of hypoxia in tumors owing to mutations in factors involved in the degradation of HIFα subunits (such as von Hippel Lindau tumor suppressor (VHL)) 159 or through increased translation through mTOR 161, and glutamine itself can also increase HIFα stabilization 162–164. We suspect that as more genes and tissues are studied, glutamine metabolism will be found to be reprogrammed through modulation of the pathways described above (Table 1) and through novel direct mechanisms.

Glutamine Metabolism in the Clinic

Imaging

Reprogrammed cancer metabolism can be used to image tumors. Glucose-based 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) 165 has been in use for more than three decades to image and stage tumors via their avid uptake of glucose. However, some tissues, particularly the brain, also take up large amounts of glucose, making FDG-PET ineffective in imaging brain tumors165. 18F-fluorinated glutamine (18F-(2S,4R)4-fluoroglutamine(18F-FGln)) was developed as a potential tumor imaging tracer and validated in animal models166, 167, and 18F-FGln PET has since been evaluated clinically and shown promise in the diagnosis of glioma 168. Importantly, in glioma18F-FGln accumulation does not necessarily suggest increased glutamine catabolism, as mouse orthotopic models of glioma and human patient samples show high rates of glutamine accumulation but comparatively low rates of glutamine metabolism 169–171. Nonetheless, 18F-FGln is a promising new tool in the diagnosis of cancers refractory to use of FDG such as glioma, and it will be of interest to determine if high 18F-FGln uptake in other tumor types is predictive of glutamine dependence and therapeutic response to inhibition of glutamine metabolism.

Therapy

The dependence of cancer cells on glutamine metabolism has made it an attractive anti-cancer therapeutic target. As detailed in Table 2, many classes of compounds that target glutamine metabolism, from initial transport in the cell to conversion to α-ketoglutarate, have been examined. While most of these are still in the preclinical ‘tool compound’ stage or have been limited by toxicity, allosteric inhibitors of GLS have shown promise in preclinical models of cancer, and one highly potent compound in this class, CB-839, has moved on to clinical trials. A preclinical tool-compound inhibitor of GLS is bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,2,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)ethyl sulfide (BPTES) 172, which has been shown to block the growth of cancer cells in vitro, of xenografts_in vivo_, and to slow tumor growth and prolong survival in genetically engineered mouse models of cancer 151, 173. CB-839 has shown efficacy against triple negative breast cancer and hematological malignancies in preclinical studies 53, 54, and is currently the subject of several clinical trials.

Table 2.

Strategies to pharmacologically target glutamine metabolism in cancer

| Class | Drug | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Glutamine mimic | 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON) 16 Azaserine 16 Acivicin 16 | Off-target effect on nucleotide biosynthesis 16, 226 Limited by toxicity 16, 227 |

| Glutamine depletion | L-Asparaginase100, 101, 228–230 | Off-target toxic conversion of glutamine to glutamate231,232 Limited by toxicity 100, 101 FDA-approved to treat ALL 102 |

| GLS inhibitors | 968 233 BPTES 172, 234–236 CB-839 53, 54 | Pre-clinical tool 237 Pre-clinical tool 151, 173 Phase I clinical trial |

| SLC1A5 inhibitors | Benzylserine 238, 239 γ-FBP 2,40 GPNA 241 | Pre-clinical tools 238–241 |

| GLUD inhibitors | EGCG 242, 243 R162 148 | Tool compound 65,67 Pre-clinical tool compound 148 |

| Aminotransferase inhibitors | AOA 65, 143 | Clinically used to treat tinnitus 244 Toxic at higher doses 143 |

| SLC7A11 or xCT system inhibitors | Sulfasalazine 18 Erastin 245 | FDA approved for arthritis 18 Tool compound, induces iron-dependent ferroptosis 246 |

The transition of glutaminase inhibition to the clinic will be aided by understanding potential inherent or acquired resistance mechanisms. Cancers that depend on GLS2 61, 64, which is not sensitive to BPTES or CB-839, would be unlikely to respond to therapy 174. The expression of pyruvate carboxylase, which can provide carbon to the TCA cycle through its conversion of pyruvate to oxaloacetate, represents a potential mechanism for glutaminase independence120, 175. Glutamine synthetase (GLUL) expression may also predict glutamine independence and promote BPTES resistance171, 176–178.

Metabolic synthetic lethality and combination therapy

The heterogeneity, varied oncogenotypes, and microenvironment of tumors pose considerable challenges to targeted therapies, but the use of combination therapy is a successful paradigm in the treatment of HIV and certain types of cancers. Particularly attractive drug combinations induce synthetic lethality, where two drugs induce cell death in combination but not individually. Many candidate preclinical synthetic lethal treatments target pathways or cellular functions that help cancer cells to compensate for the targeting of another pathway or cellular function. The pleiotropic role of glutamine in cellular functions, such as energy production, macromolecular synthesis, mTOR activation, and ROS homeostasis 179, makes GLS inhibition a potentially ideal candidate for combination therapy, as detailed in Table 3. A few combinations are notable because they reveal novel consequences of glutamine metabolism. Specific inhibition of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 synergizes with glutaminase inhibition 53, consistent with the described role of glutamine in controlling expression and activity of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins, as reviewed recently 180. Similarly, the synergism between glutamine withdrawal and chemical activation of the ISR with the retinoid-derivative fenretinide 65 shows that glutamine can suppress this stress response through various mechanisms, as discussed above. While invasive and metastatic cells have not specifically been studied for their sensitivity to glutaminolysis inhibition, it has been shown that highly invasive ovarian cancer cells have increased glutamine dependence compared to less invasive cells 181, and metastatic prostate tumors show increased glutamate availability and dependence on glutamine uptake93, 182. Indeed, genetic inhibition of glutaminase was shown to prevent epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, a key step in tumor cell invasiveness and eventual metastasis 183. Thus, prevention of metastasis may be another avenue to focus on the development of combinatorial strategies in glutamine metabolic inhibition.

Table 3.

Treatments that are synthetically lethal with inhibition of glutamine metabolism

| Co-treatment | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Metformin | Metformin decreases glucose oxidation to increase cellular dependence on glutamine 247. |

| GLUT1 inhibition | Combined downregulation of glucose transport (Apigenin) and glutaminase causes severe metabolic stress 248. |

| Glycolysis inhibition (2-DG) | Blocking of compensatory glutamine contribution to TCA cycle, nucleotides and mTOR signaling blocks growth in 2-DG resistant cells 249. |

| Mitochondrial pyruvate carrier inhibition | Specific chemical inhibition of pyruvate transport into the mitochondrion synergizes with inhibition of glutaminolysis to cause increased death 250. |

| Transglutaminase inhibition | Combined inhibition of glutaminase and transglutaminase causes potentially lethal acidification 251. |

| mTOR inhibition | Consistent with the role of glutamine in mTOR activation 219 and mTOR control of metabolism, GLS and mTOR inhibition are synthetic lethal252. |

| ATF4 activation | Glutamine withdrawal activates the ISR, and further activating this pathway with the retinoid-derivative fenretinide causes increased cancer cell death 65. |

| BCL-2 inhibition | Inhibiting GLS causes apoptosis through altered metabolism, with the effect exacerbated by inhibition of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 53. |

| HSP90 inhibition | Consistent with a role of GLS in controlling ROS and ER stress, HSP90 and GLS inhibition cause ER stress-induced cell death via ROS 253. |

| BRAF inhibition | BRAF inhibition resistance causes a shift to glutamine dependence, and so combination therapy may be used to combat this resistance 254. |

| NOTCH inhibition | NOTCH1 promotes glutaminolysis in T-ALL, sensitizing NOTCH inhibited T-ALL cells to genetic and pharmacological GLS inhibition 255. |

| EGFR inhibition | GLS inhibition restores sensitivity to the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib in cells which had developed resistance256. |

The effects of metabolic inhibitors in vivo may also broadly influence immunity. There has been a recent surge of interest in manipulating the immune response to target cancer, either through the blocking of immune checkpoints or the use of engineered chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. These approaches require immune cells to function within the tumor microenvironment. Recent work has indicated that immune cells compete with cancer cells for glucose 184, and we speculate that perhaps this may be true for glutamine as well. In fact, glutamine metabolism is increased in T-cell activation and regulates skewing of CD4+ T-cells towards more inflammatory subtypes32, 185, 186. While ex vivo experiments suggest that lymphocytes show signs of proper activation even in the presence of CB-839173, it remains to be seen how GLS inhibition will affect anti-tumor immunity in vivo. Studies in mouse lymphocytes suggest that the CB-839-insensitive GLS2 may play a key role in lymphocyte proliferation 144, and so targeting of glutamine metabolism through the modulation of tumor-specific pathways may be required to maintain both high glutamine availability and immune response.

Glutamine Usage: Plastic versus Patient

While the critical role of glutamine metabolism in cancer cells in vitro is well established, less clear is what role glutamine plays in tumors in vivo, which can face shortages of nutrients and oxygen7. Not surprisingly, tumors utilize a variety of nutrients as carbon sources and energy besides glucose and glutamine, including lipids and acetate 187–189, and may also utilize macropinocytosis to support amino acid pools 22. However, the circumstances under which macropinocytosis becomes dominant in vivo remain to be established. As an illustrative example of the metabolic complexity of tumors, lung cancer cell lines are often glutamine dependent in vitro, but a recent study of K-RAS driven mouse lung tumors demonstrated that glucose but not glutamine was preferentially used to supply carbon to the TCA cycle, through the action of pyruvate carboxylase 190. Furthermore, two recent metabolomics and metabolic flux studies of primary human lung cancer showed little change in glutamine entry into the TCA cycle, and instead suggested that human lung cancer can synthesize glutamine from the TCA cycle120, 191. Human and mouse gliomas exhibit high rates of glucose catabolism and accumulate but do not avidly metabolize glutamine168, and do not depend on circulating glutamine to maintain cancer growth, but instead utilize glucose to synthesize glutamine through glutamine synthetase to support nucleotide biosynthesis169–171. Hence, much more work is needed to further define the use of nutrients in vivo, to guide the selection of metabolic therapies in the clinic.

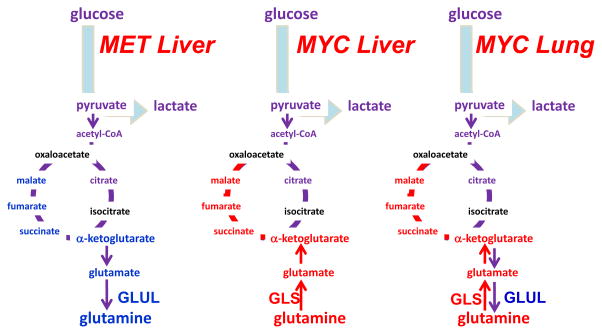

Nevertheless, glutamine metabolism has been documented as critical for tumorigenesis and tumor survival in specific in vivo models151, 173, 192,193, which have varied metabolic profiles depending on the tumor oncogenotype. The complexities in vivo are exemplified by a study utilizing mouse models to compare the effects of metabolic driver and tissue of origin on tumor metabolism 177 (Figure 8). MET-driven liver tumors expressed glutamine synthetase and so presumably made their own glutamine from glucose flux, and thus do not need to take up glutamine from the environment. Likewise, MYC-driven lung tumors upregulated both GLS and glutamine synthetase, consistent with a recent study showing that MYC indirectly induces glutamine synthetase 177, 178. Conversely, MYC-driven liver tumors upregulated GLS and SLC1A5 and avidly consumed and catabolized glutamine 173, 177 (Figure 8). In fact, in this same MYC-driven liver cancer model, loss of a single copy of GLS slowed tumor growth and pharmacologic inhibition of GLS prolonged survival 173, suggesting the critical importance of glutamine metabolism in certain cancer settings. The heterogeneity of glutamine metabolism in tumors arising in the same tissue type, demonstrated by the MYC and MET driven liver models, is mirrored in studies of human breast cancer that show that ER+ breast cancer cell lines are less glutamine dependent than triple negative breast cancer cell lines 18, 54, 176. This finding is further supported by a study in primary ER− human breast tumors that shows high glutamine to glutamate ratio in the tumors, suggesting increased glutamine catabolism 194.

Figure 8. Differing requirements for glutamine in cancer based on oncogene and tissue of origin.

The oncoproteins MET and MYC lead to differing dependence on glutamine in different cancer types, which is partially influenced by differential expression of glutamine synthetase (GLUL) or glutaminase (GLS). α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; OAA, oxaloacetate; Illustration is drawn from primary data originally presented in Yuneva et al.177.

Altered glutamine metabolism can interact with the tumor microenvironment in surprising ways. Increased lactate, which may be present in the microenvironment as a consequence of increased glycolysis by cancer cells 7, has been shown to promote increased glutamine metabolism via a HIF2 and MYC-dependent mechanism 195, potentially providing a way for an evolving tumor to ‘reprogram’ itself towards increased glutaminolysis. Similarly, as discussed above, increased glutaminolysis causes an increase in excreted ammonia and autophagy in exposed cells 137, 138, and indeed, a study with co-culture of breast cancer cells and fibroblasts showed that the ammonia released from breast cancer cells stimulated autophagy in the fibroblasts to release additional glutamine, which was then taken up and metabolized by the cancer cells 196. However, ammonia can be toxic to surrounding cells, and since tumors engaging in glutaminolysis may excrete large amounts of ammonia, it is still unknown how surrounding non-transformed cells detoxify this ammonia. Finally, some tumors, particularly those of the brain and the lung 120, 169–171, 191, may synthesize and excrete glutamine, and it is still not known how this increased glutamine in the microenvironment may affect the physiology of neighboring cells. Understanding the interaction between tumor microenvironment, tissue-of-origin and oncogenic drivers may be the key to deconvoluting the potential role of glutamine in different tumor types.

Concluding remarks

Ninety years ago, Warburg uncovered that many animal and human tumors displayed high avidity for glucose, which was largely converted to lactate through aerobic glycolysis. Warburg also suggested that cancers are caused by altered metabolism and loss of mitochondrial function. These dogmatic views have been replaced and refined over the last several decades with the emergence of oncogenic alterations of metabolism, appreciation of the importance of mitochondrial oxidation in cancer physiology, and the rediscovery of the role of glutamine in tumor cell growth in addition to the pivotal role of glucose. Here, we provide an updated overview of glutamine metabolism in cancers and discuss the complexity of metabolic re-wiring as a function of the tumor oncogenotype as well as the microenvironment that adds to the heterogeneity found in vivo. In certain types of cancers, such as those driven by MYC, tumor cells appear to depend on glutamine, and hence targeting glutamine metabolism pharmacologically may prove to be beneficial. Conversely, different oncogenic drivers may result in tumor cells that could bypass the need for glutamine. Targeted inhibition of some oncogenic drivers, however, has been reported to re-wire cells to become dependent on glutamine, and hence targeted inhibitors could be synthetically lethal with inhibition of glutamine metabolism. Overall, the field of cancer metabolism has made considerable progress in understanding alternative fuel sources for cancers including glutamine, which under specific circumstances can be exploited for therapeutic purposes.

Key points.

- Cancer cells show increased consumption of and dependence on glutamine.

- Glutamine metabolism fuels the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, nucleotide and fatty acid biosynthesis, and redox balance in cancer cells.

- Glutamine activates mTOR signaling, suppresses endoplasmic reticulum stress, and promotes protein synthesis.

- Cancer cells may metabolize glutamate to α-ketoglutarate through one of two different pathways (glutamate dehydrogenase or aminostransferases), with aminotransferases potentially supporting a more biosynthetic and pro-growth phenotype.

- Activation of oncogenic pathways and loss of tumor suppressors reprogram glutamine metabolism in a tissue-dependent manner.

- Targeting glutamine metabolism shows promise as an anti-cancer therapy. Compensatory glutamine metabolism induced by cancer therapies suggests targeting glutamine metabolism may be used in combination therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ralph DeBerardinis (Children’s Research Institute at UT Southwestern, Dallas, TX) and Jonathan Coloff (Department of Cell Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) for helpful commentary and discussion. We apologize to any authors whose work could not be included due to space limitations. This work is partially supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01CA057341 (C.V.D), The Leukemia and Lymphoma Society LLS 6106-14 (C.V.D.), and the Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute. B.J.A and Z.E.S were supported by the NCI F32CA180370 and F32CA174148, respectively.

Glossary

2-Hydroxyglutarate

An α-hydroxy acid sometimes produced at high levels by cancer cells, which structurally resembles α-ketoglutarate and so inhibits α-ketoglutarate-dependent enzymes such as the jumonji-family histone demethylases. The D-2HG enantiomer is produced downstream of mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase enzymes in glioma and acute myelogenous leukemia, and the L-2HG enantiomer is produced under hypoxia.

Aminotransferases

A class of enzymes, also known as transaminases, which catalyze the reaction between an α-keto acid such as pyruvate and an α-amino acid to form a different amino acid and α-keto acid. For example, glutamic-pyruvate transaminase (GPT, alanine aminotransferase) transfers a nitrogen from glutamate to pyruvate to make alanine and α-ketoglutarate.

Autophagy

Refers to the macroautophagy, which is a process of bulk cytoplasmic and organelle degradation by specialized organelles called autophagosomes, which then deliver the contents to the lysosome. Autophagy is increased under many forms of stress and can provide nutrients for metabolism.

Cap-dependent translation

In most eukaroyotic mRNAs, translation relies on the initiation factor eIF4E binding to the 5′ mRNA cap (a modified nucleotide), along with the ribosome and other initiation factors. Certain stress pathways including ER stress and the ISR inhibit cap-dependent translation through inhibitory phosphorylation of the initiation factor eIF2α.

Caloric restriction

Restricting the available calories to a model organism, such as a mouse or C. elegans, without under-nourishing them. Caloric restriction has been shown in several species to delay age-associated diseases and dramatically extend lifespan.

Electron transport chain

A series of transmembrane protein complexes, present on the inner membrane mitochondria, which transfer electrons via redox reactions to the terminal electron acceptor oxygen, which is reduced with binding of protons to a water molecule. This generates a proton gradient that powers ATP synthase to produce ATP. Premature leakage of electrons to oxygen can lead to production of ROS.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress

Refers to various stresses that lead to protein misfolding and activate the unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR, which shares molecular machinery with the ISR, halts cap-dependent translation, induces expression of ER chaperone proteins, and can lead to death if the stress is not resolved.

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

A complex process observed in invasive solid tumors of epithelial origin in which the cancer cells acquire a mesenchymal phenotype, break through the basement membrane, and enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system via the process of intravasation. EMT is promoted by many genetic, epigenetic, and physiologic alterations commonly found in cancer.

Ferroptosis

An intracellular iron-dependent form of cell death that is distinct from apoptosis.

Glutathione

A tripeptide (glutamate-cysteine-glycine) which acts as an important antioxidant. The reduced form (GSH) can react with H2O2 to form the oxidized form (GSSG).

Hexosamine

A nitrogenous sugar created from a monosaccharide and amino acids that can be used to modify proteins to aid in protein folding and trafficking.

Integrated stress response (ISR)

A stress response pathway that responds to various cellular insults, including amino acid deprivation, through the GCN2 kinase, to phosphorylate eIF2α halt general cap-dependent protein translation, and increase transcription of endoplasmic reticulum chaperone proteins. The ISR may eventually result in apoptotic cell death if the stress is not resolved.

Macropinocytosis

A type of endocytosis where extracellular fluid and nutrients are engulfed and taken up into vesicles called macropinosomes. The contents can then be digested by lysosomal degradation to provide nutrients for metabolism.

Oncogenotype

The genetic or epigenetic alterations (to activate an oncoprotein or disable a tumor suppressor pathway) that drive the evolution and phenotype of a given tumor.

One-carbon metabolism pathway

A pathway centered on the metabolism of folate, an important carbon donor for DNA methylation and purine nucleotide synthesis. This pathway is linked to the de novo biosynthesis pathways of serine and glycine.

Reductive carboxylation

A process that occurs in some normal and cancer cells whereby α-ketoglutarate proceeds ‘backwards’ through the TCA cycle, being reduced through the consumption of NADPH by isocitrate dehydrogenase in the non-canonical reverse reaction to form citrate. This citrate may then be used in fatty acid synthesis.

Serine and glycine biosynthesis

De novo synthesis of serine and glycine from the glycolytic intermediate 3-PG. PHGDH converts 3-PG to 3-phosphohydroxypyruvate, with is then converted by the enzyme PSAT1 to 3-phosphospherine, which is converted to serine by PSPH. Serine can further be converted to glycine by the enzymes SHMT1/2, which also forms 5,10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate, which in turn fuels the folate cycle and nucleotide biosynthesis.

Synthetic lethality

A combination of two inhibitors or losses-of-function that, individually, do not produce death in cancer cells, but, when combined, synergistically induce death. Given that cancers may alter their metabolism in response to traditional chemotherapy and targeted agents, metabolic inhibitors such as inhibitors of glutamine metabolism are particularly attractive targets in synthetic lethality studies.

Biographies

Brian J. Altman, Ph.D. is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Hematology-Oncology and the Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, PA, USA. His research focuses on the role of the MYC oncogene and glutamine input in circadian rhythm in cancer.

Zachary E. Stine, Ph.D. is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Hematology-Oncology and the Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, PA, USA. His research focuses on the role of glutamine metabolism and glutaminase expression in cancer.

Chi V. Dang, M.D., Ph.D. is the John H. Glick Professor and Director of the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, PA, USA. He has made contributions to the understanding of the role of MYC in cancer, particularly its role as a transcription factor and its target genes that reprogram cancer metabolism.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

There is NO competing interest.

References

- 1.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–14. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeBerardinis RJ, Cheng T. Q’s next: the diverse functions of glutamine in metabolism, cell biology and cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:313–24. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hensley CT, Wasti AT, DeBerardinis RJ. Glutamine and cancer: cell biology, physiology, and clinical opportunities. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3678–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI69600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lacey JM, Wilmore DW. Is glutamine a conditionally essential amino acid? Nutr Rev. 1990;48:297–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1990.tb02967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubin AL. Suppression of transformation by and growth adaptation to low concentrations of glutamine in NIH-3T3 cells. Cancer Res. 1990;50:2832–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuneva M, Zamboni N, Oefner P, Sachidanandam R, Lazebnik Y. Deficiency in glutamine but not glucose induces MYC-dependent apoptosis in human cells. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:93–105. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayers JR, Vander Heiden MG. Famine versus feast: understanding the metabolism of tumors in vivo. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40:130–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergstrom J, Furst P, Noree LO, Vinnars E. Intracellular free amino acid concentration in human muscle tissue. J Appl Physiol. 1974;36:693–7. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.36.6.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krebs HA. In: Glutamine: Metabolism, Enzymology, and Regulation. Mora J, Palacios R, editors. Academic Press, Inc; New York, NY, USA: 1980. pp. 319–329. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stumvoll M, Perriello G, Meyer C, Gerich J. Role of glutamine in human carbohydrate metabolism in kidney and other tissues. Kidney Int. 1999;55:778–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.055003778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felig P, Wahren J, Raf L. Evidence of inter-organ amino-acid transport by blood cells in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973;70:1775–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.6.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor L, Curthoys NP. Glutamine metabolism: Role in acid-base balance*. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2004;32:291–304. doi: 10.1002/bmb.2004.494032050388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krebs HA, Henseleit K. Untersuchungen uber die Harnstoffbildung im Tierkörper. Hoppe-Seyler’s Zeitschrift für physiologische Chemie. 1932;210:33–66. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Windmueller HG, Spaeth AE. Uptake and metabolism of plasma glutamine by the small intestine. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:5070–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhutia YD, Babu E, Ramachandran S, Ganapathy V. Amino Acid transporters in cancer and their relevance to “glutamine addiction”: novel targets for the design of a new class of anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1782–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wise DR, Thompson CB. Glutamine addiction: a new therapeutic target in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:427–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicklin P, et al. Bidirectional transport of amino acids regulates mTOR and autophagy. Cell. 2009;136:521–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timmerman LA, et al. Glutamine sensitivity analysis identifies the xCT antiporter as a common triple-negative breast tumor therapeutic target. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:450–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerr MC, Teasdale RD. Defining macropinocytosis. Traffic. 2009;10:364–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bar-Sagi D, Feramisco JR. Induction of membrane ruffling and fluid-phase pinocytosis in quiescent fibroblasts by ras proteins. Science. 1986;233:1061–8. doi: 10.1126/science.3090687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamphorst JJ, et al. Human pancreatic cancer tumors are nutrient poor and tumor cells actively scavenge extracellular protein. Cancer Res. 2015;75:544–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Commisso C, et al. Macropinocytosis of protein is an amino acid supply route in Ras-transformed cells. Nature. 2013;497:633–7. doi: 10.1038/nature12138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palm W, et al. The Utilization of Extracellular Proteins as Nutrients Is Suppressed by mTORC1. Cell. 2015;162:259–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Overmeyer JH, Kaul A, Johnson EE, Maltese WA. Active ras triggers death in glioblastoma cells through hyperstimulation of macropinocytosis. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:965–77. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strohecker AM, et al. Autophagy sustains mitochondrial glutamine metabolism and growth of BrafV600E-driven lung tumors. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1272–85. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin TC, et al. Autophagy: resetting glutamine-dependent metabolism and oxygen consumption. Autophagy. 2012;8:1477–93. doi: 10.4161/auto.21228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pochini L, Scalise M, Galluccio M, Indiveri C. Membrane transporters for the special amino acid glutamine: structure/function relationships and relevance to human health. Front Chem. 2014;2:61. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curthoys NP, Watford M. Regulation of glutaminase activity and glutamine metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 1995;15:133–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.15.070195.001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krebs HA. Metabolism of amino-acids: The synthesis of glutamine from glutamic acid and ammonia, and the enzymic hydrolysis of glutamine in animal tissues. Biochem J. 1935;29:1951–69. doi: 10.1042/bj0291951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moreadith RW, Lehninger AL. The pathways of glutamate and glutamine oxidation by tumor cell mitochondria. Role of mitochondrial NAD(P)+-dependent malic enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:6215–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeBerardinis RJ, et al. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19345–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang R, et al. The transcription factor Myc controls metabolic reprogramming upon T lymphocyte activation. Immunity. 2011;35:871–82. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan J, et al. Glutamine-driven oxidative phosphorylation is a major ATP source in transformed mammalian cells in both normoxia and hypoxia. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:712. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Son J, et al. Glutamine supports pancreatic cancer growth through a KRAS-regulated metabolic pathway. Nature. 2013;496:101–5. doi: 10.1038/nature12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hosios AM, et al. Amino Acids Rather than Glucose Account for the Majority of Cell Mass in Proliferating Mammalian Cells. Dev Cell. 2016;36:540–9. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Consortium G. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348:648–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1262110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cassago A, et al. Mitochondrial localization and structure-based phosphate activation mechanism of Glutaminase C with implications for cancer metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1092–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112495109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elgadi KM, Meguid RA, Qian M, Souba WW, Abcouwer SF. Cloning and analysis of unique human glutaminase isoforms generated by tissue-specific alternative splicing. Physiol Genomics. 1999;1:51–62. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.1999.1.2.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shapiro RA, Farrell L, Srinivasan M, Curthoys NP. Isolation, characterization, and in vitro expression of a cDNA that encodes the kidney isoenzyme of the mitochondrial glutaminase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18792–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu W, Zuo Y, Feng Y, Zhang M. SIRT5 facilitates cancer cell growth and drug resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:10699–705. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2372-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polletta L, et al. SIRT5 regulation of ammonia-induced autophagy and mitophagy. Autophagy. 2015;11:253–70. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1009778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hebert AS, et al. Calorie restriction and SIRT3 trigger global reprogramming of the mitochondrial protein acetylome. Mol Cell. 2013;49:186–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao L, Huang Y, Zheng J. STAT1 regulates human glutaminase 1 promoter activity through multiple binding sites in HIV-1 infected macrophages. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masamha CP, et al. CFIm25 links alternative polyadenylation to glioblastoma tumour suppression. Nature. 2014;510:412–6. doi: 10.1038/nature13261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Redis RS, et al. Allele-Specific Reprogramming of Cancer Metabolism by the Long Non-coding RNA CCAT2. Mol Cell. 2016;61:520–34. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ince-Dunn G, et al. Neuronal Elav-like (Hu) proteins regulate RNA splicing and abundance to control glutamate levels and neuronal excitability. Neuron. 2012;75:1067–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xia Z, et al. Dynamic analyses of alternative polyadenylation from RNA-seq reveal a 3′-UTR landscape across seven tumour types. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5274. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao P, et al. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:762–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hansen WR, Barsic-Tress N, Taylor L, Curthoys NP. The 3′-nontranslated region of rat renal glutaminase mRNA contains a pH-responsive stability element. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:F126–31. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.1.F126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colombo SL, et al. Anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome-Cdh1 coordinates glycolysis and glutaminolysis with transition to S phase in human T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18868–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012362107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]