Genetic Predisposition, Clinical Risk Factor Burden, and Lifetime Risk of Atrial Fibrillation (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2019 Mar 6.

Abstract

Background

The long-term probability of developing atrial fibrillation (AF) considering genetic predisposition and clinical risk factor burden is unknown.

Methods

We estimated lifetime risk of AF in individuals from the community-based Framingham Heart Study. Polygenic risk for AF was derived using a score of approximately 1,000 AF-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms. Clinical risk factor burden was calculated for each individual using a validated risk score for incident AF comprised of height, weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, current smoking status, antihypertensive medication use, diabetes, history of myocardial infarction, and history of heart failure. We estimated the lifetime risk of AF within tertiles of polygenic and clinical risk.

Results

Among 4,606 participants without AF at age 55 years, 580 developed incident AF (median follow-up, 9.4 years; 25th-75th percentile, 4.4-14.3 years). The lifetime risk of AF after age 55 years was 37.1%, and was substantially influenced by both polygenic and clinical risk factor burden. Among individuals free of AF at age 55 years, those in low polygenic and clinical risk tertiles had a lifetime risk of AF of 22.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.4%-29.1%), whereas those in high risk tertiles had a risk of 48.2% (95% CI, 41.3%-55.1%). A lower clinical risk factor burden was associated with later AF onset after adjusting for genetic predisposition (P value <0.001).

Conclusions

In our community-based cohort, the lifetime risk of AF was 37%. Estimation of polygenic AF risk is feasible, and together with clinical risk factor burden explains a substantial gradient in long-term AF risk.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, lifetime risk, genetics, polygenic risk, risk factor, risk stratification, epidemiology

The probability of developing atrial fibrillation (AF) is influenced by both inherited and acquired risk factors.1-3 Genetic association studies of common genetic variants have confirmed a polygenic basis for AF.4,5 Well-validated clinical risk factors such as anthropometrics and cardiovascular disease components can stratify short-term AF risk.3 Although both genetic predisposition and clinical risk factor burden are associated with AF risk, the contribution of these well-established risk factors to the long-term probability of developing AF is unknown.

By accounting for competing causes of death, lifetime risk estimates provide accurate assessments of long-term disease probabilities within populations.6 For AF in particular, such estimates can serve as practical risk approximations both for clinicians and patients since the short-term risks of AF are generally small.3 Previous lifetime risk estimates for AF have typically reflected average risks in entire study samples rather than within specific risk factor strata.7-12

Comprehensive genomic assessment is currently feasible and accessible as is evidenced by direct-to-consumer availability of genetic tests, yet remains of uncertain utility partly owing to the lack of valid associations with long-term disease risks.13 Simultaneously, increasing emphasis is being placed on addressing modifiable risk factors to potentially prevent AF, given morbidity associated with the disease.14,15 Thus, there is a critical need to understand the joint relations between established risk factors and the probability of developing AF.

We therefore sought to characterize the degree to which inherited predisposition and clinical risk factor burden influence the long-term probability of developing AF. With longitudinal follow-up, genome-wide genotyping information, and detailed assessment of clinical risk factors, the community-based Framingham Heart Study is well-suited for the examination of associations between inherited predisposition and clinical risk factor burden in relation to lifetime risk of developing AF.

Methods

Summary level genetic association results cited in this manuscript are available in the Cardiovascular Disease Knowledge Portal (http://broadcvdi.org).16 Individual level data from samples described are available through application to the respective respositories.17,18

Study Sample

We calculated lifetime risks of AF in the Framingham Heart Study, a community-based observational cohort study designed to investigate cardiovascular disease risk factors.19-21 The Original cohort was comprised of 5,209 men and women from Framingham, Massachusetts, aged 30-62 years in 1948 during their first round of standardized examinations. Participants returned for detailed medical histories, physical examinations, and laboratory tests every two years. Beginning in 1971, spouses and children of the Original cohort participants (n=5,124) were recruited in the Offspring cohort with similar examinations every four to eight years. Participants from the Third Generation cohort (i.e., grandchildren of the Original cohort) were enrolled in 2002 and were examined every six to eight years. All participants signed informed consents at each examination cycle, and the Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved study protocols.

For the present analysis, we derived three samples based on participants who attended a study examination within five years of each of the attained ages of 55 (n=10,239), 65 (n=7,909), and 75 years (n=5,047). We selected age 55 years as the initial age to maximize the sample of participants in whom DNA was ascertained prior to an index attained age. Participants could be included in more than one sample. From these samples, we excluded participants if they lacked follow-up after the attained age, did not participate in DNA collection, had prevalent AF at the study examination or DNA collection, had DNA collected after age 95 years, or lacked complete single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) or risk factor data (see below for further description and sample selection flowcharts in Supplemental Figures 1-4). In sensitivity analyses we also estimated the lifetime risk of AF in individuals without available DNA.

AF Ascertainment

AF was ascertained in the Framingham Heart Study as previously described.22 Briefly, at each study examination, participants' medical histories, physical examinations, and electrocardiograms were obtained. Records of all interim outpatient appointments and hospitalizations for cardiovascular disease were sought for manual review by mailings and telephone calls via health history updates every 24 months. Participants were classified as having AF if the arrhythmia was present on an electrocardiogram obtained at a study visit or encounter with external clinicians, Holter monitoring, or noted in hospital records. Study investigators reviewed all available records, regardless of symptoms, to determine the dates of AF. Two physicians adjudicated first-detected AF events.

Genotyping And Imputation

Details of genotyping, imputation, and quality control have been previously described 23 and are summarized in the Supplemental Methods.

Polygenic Risk For AF

Full methods of the approach to estimating genetic predisposition to AF are described in the Supplemental Methods and are briefly summarized here. Our approach was motivated by the concept that complex genetic trait liability may be explained by the cumulative effects of hundreds or thousands of common genetic variants, many of which are associated with traits at levels that do not exceed the stringent genome-wide significance threshold (i.e., P value <5×10-8).24-27 We therefore created 30 candidate SNP groups using association results from a prior genome-wide association study of AF (133,073 individuals overall, 17,931 with AF),4 by selecting SNPs across a preselected range of six increasingly liberal degrees of association with AF (i.e., from P value <5×10-8 to <0.001), and five linkage disequilibrium thresholds (i.e., from r2 ≥0.1 to ≥0.9). The derived groups were comprised of between 58 to 10,751 SNPs.

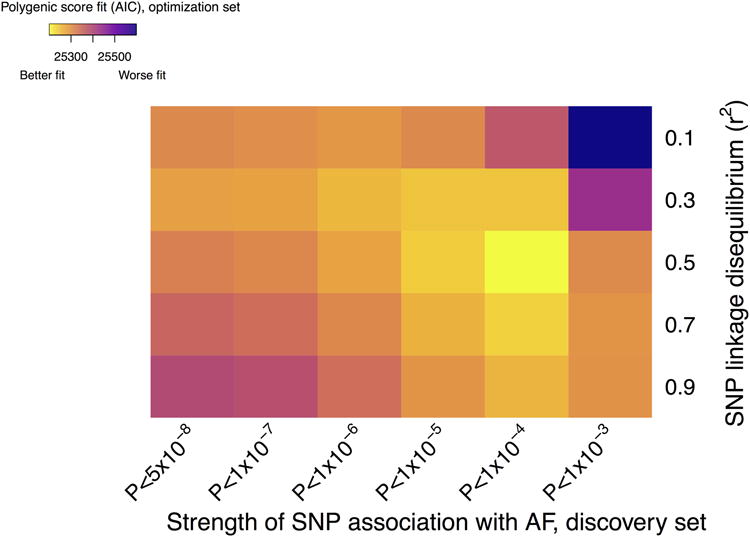

We then constructed polygenic risk scores from the candidate SNP groups and independently validated scores by testing each for association with AF in 120,286 individuals of European ancestry in the population-based UK Biobank 17 (described in the Supplemental Methods) using multivariable logistic regression. We calculated scores by summing the dosage of each AF risk allele carried by an individual (ranging from zero to two for each SNP) weighted by the natural logarithm of the relative risk for each SNP from the prior analysis,4 to yield a single continuous value for each individual. Models were adjusted for age, sex, genotyping array, and one principal component of ancestry. We considered the most informative score the one with the best model fit, as measured by the lowest Akaike's Information Criterion.28 Polygenic risk scores were strongly associated with AF in the UK Biobank, with P values ranging from 3.1×10-55 to 1.5×10-146. The best-fitting score (Figure 1) was derived from a candidate group of 1,168 SNPs (of which 835 were imputed with high quality in the UK Biobank, Supplemental Table 1). Regions tagged by the optimal SNP score accounted for a greater proportion of variance in AF susceptibility in the UK Biobank as measured by SNP-heritability 29 (7.4%, 95% CI 6.1%-8.8%) than those tagged by genome-wide significant loci alone (3.0%, 95% CI 2.2%-3.8%) (see Supplemental Methods for detail). We therefore calculated polygenic risk scores for AF in Framingham Heart Study participants based on the same candidate SNP group (of which 986 SNPs were genotyped or imputed with high confidence in Framingham) using the same approach defined above. Further description of our approach is provided in the Supplemental Methods.

Figure 1. Defining polygenic risk for atrial fibrillation (AF).

In total, we derived 30 candidate polygenic risk scores from the results of a prior genetic association study of AF.4 Each risk score was comprised of candidate single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) selected based on a varying strength of SNP association with AF in the prior analysis (x-axis) and the degree of linkage disequilibrium between each SNP (y-axis). Polygenic risk scores were then created as outlined in the methods section using a linear weighted approach and tested for association with AF in an independent sample from the UK Biobank (N=120,286 individuals of European ancestry total, 2,987 with AF). The most informative, or optimal, polygenic risk score was defined as that with the best model fit as defined by the lowest Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC). Colors correspond to model fit, with yellow indicating a better fit. All scores were highly associated with AF in the optimization sample (P value range 3.1×10-55 to 1.5×10-146). The optimal score was comprised of 1,168 SNPs.

All participants in the UK Biobank provided written informed consent to participate in research as previously described,17 and the UK Biobank was approved by the UK Biobank Research Ethics Committee (reference number 11/NW/0382). Use of UK Biobank data was approved by the local Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board.

Clinical Risk For AF

We estimated clinical risk factor burden in each Framingham Heart Study participant by using a validated composite five-year clinical risk score for AF (Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology AF [CHARGE-AF] Score).3,30-33 For each sample at the attained ages of 55, 65, and 75 years, we measured clinical risk factors for each individual within five years of the attained age and calculated the clinical composite score as a weighted sum of clinical risk factors that included height, weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, current smoking status, use of antihypertensive medication, diabetes, and history of myocardial infarction and history of heart failure. Weights for each component are provided in the Supplemental Methods. Ascertainment of these clinical risk factors has previously been described.22 Since we assessed the residual lifetime risk of AF within strata of attained age, we omitted age from the composite score.

Statistical Analysis

We performed lifetime risk analyses in each of three samples from the Framingham Heart Study based on a person's index or “attained” age free of AF. The three samples were defined at ages of 55 years, 65 years, and 75 years. Participants were followed from the later of the date of their index age free of AF or their date of DNA collection, until their first AF event, death, last available date known to be free of AF based on a Framingham examination or medical records, age 95 years, or December 31, 2014, whichever occurred first. The multiple-decrement life-table approach was applied to calculate the lifetime risk of AF, adjusting for the competing risk of death.6 Adjustment for the competing risk of death avoids over-inflation of cumulative incidence estimates that may occur if the competing risk is not taken into account.

We first calculated lifetime risk estimates for each attained age overall. We then performed the same life-table approach stratified by tertiles of the AF polygenic risk score and the clinical risk factor score separately. Tertiles were derived based on the distributions in the overall sample specific to each index age. Tertile 1 was considered “low risk”, tertile 2 was considered “intermediate risk”, and tertile 3 was considered “high risk.” We then assessed the joint contributions of genetic predisposition and clinical risk factor burden by calculating lifetime risks of AF within cross-tabulated tertiles of both the polygenic risk score and clinical risk score, resulting in nine risk strata in total. In secondary analyses, we calculated the cumulative incidences of AF at 10-year, 20-year, and 30-year time horizons. We also performed an exploratory analysis in which we regressed AF on continuous genetic predisposition and clinical risk factor burden in the age 55 years sample, and introduced a multiplicative interaction term. Models were fit using proportional hazards regression with and without adjustment for the competing risk of death.34

To assess whether a favorable cardiovascular risk profile was associated with a later age of AF onset after accounting for genetic predisposition, we regressed the age of AF onset on the clinical risk factor burden both within tertiles of polygenic risk scores and separately, adjusted for tertiles of polygenic risk, among individuals who developed AF using linear regression. Analyses were performed in the sample of individuals with an attained age of 55 years without AF. Two-sided P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute), PLINK v1.9,35 and R version 3.2.2.36

Results

In total, 5,131 unique individuals were included in the analyses for the three samples defined by attained ages of 55 (n=4,606), 65 (n=3,271), and 75 (n=1,887) years without AF (Table 1). Among participants alive and free of AF at 55 years of age, 580 developed AF during the observed follow-up period. The median (25th-75th percentile) follow-up durations for the attained ages of 55, 65, and 75 years samples were 9.4 years (4.4-14.3 years), 7.4 years (3.2-12.7 years), and 5.6 years (2.1-9.1 years), respectively. As expected, the proportions with comorbid medical illnesses were generally greater among older participants. Participants with DNA who were included in the study were generally ascertained in a more contemporary era than those without DNA (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 5,131 participants according to attained age.

| Attained Age Free of Atrial Fibrillation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 55 Yr (N=4606) | 65 Yr (N=3271) | 75 Yr (N=1887) | |

| Framingham Heart Study Cohort | |||

| Original, No. (%) | 378 (8.2) | 542 (16.6) | 638 (33.8) |

| Offspring, No. (%) | 3124 (67.8) | 2584 (79.0) | 1242 (65.8) |

| Third Generation, No. (%) | 1104 (24.0) | 145 (4.4) | 7 (0.4) |

| Years of follow-up, median (25th-75th percentile) | 9.4 (4.4-14.3) | 7.4 (3.2-12.7) | 5.6 (2.1-9.1) |

| Age at covariate measurement, y | 55.0±1.9 | 65.0±1.7 | 74.9±1.6 |

| Age at DNA collection, y | 59.6±11.3 | 65.9±10.4 | 73.4±8.6 |

| Women, No. (%) | 2492 (54.1) | 1869 (57.1) | 1120 (59.4) |

| Current smoker, No. (%) | 915 (19.9) | 422 (12.9) | 124 (6.6) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 125±17 | 131±18 | 137±20 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 78±10 | 76±10 | 72±10 |

| Hypertension treatment, No. (%) | 1031 (22.4) | 1299 (39.7) | 1015 (53.8) |

| Height, cm | 168±9 | 166±9 | 163±10 |

| Weight, kg | 78.3±17.5 | 77.0±16.6 | 73.6±15.2 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 270 (5.9) | 350 (10.7) | 246 (13.0) |

| History of heart failure, No. (%) | 15 (0.3) | 20 (0.61) | 21 (1.1) |

| History of myocardial infarction, No. (%) | 74 (1.6) | 126 (3.9) | 101 (5.4) |

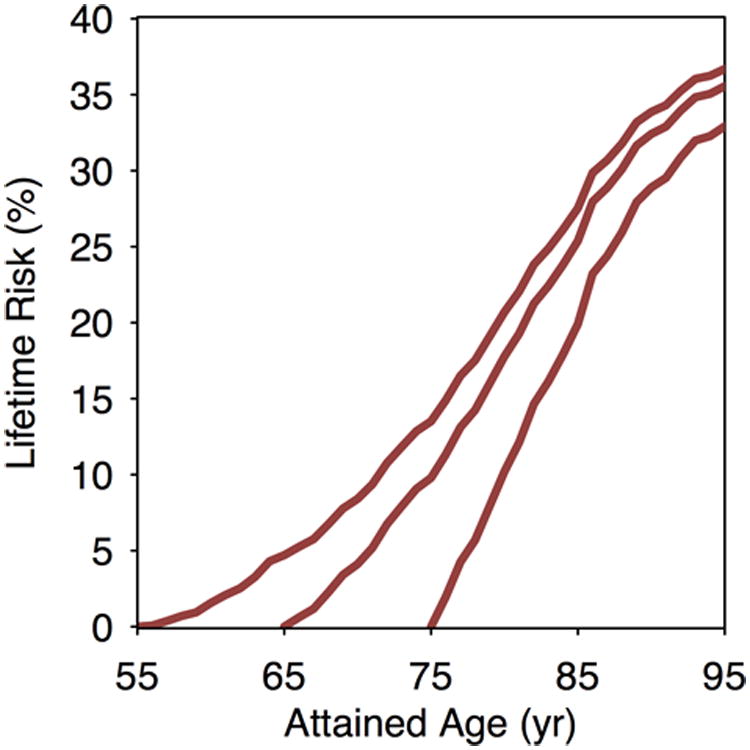

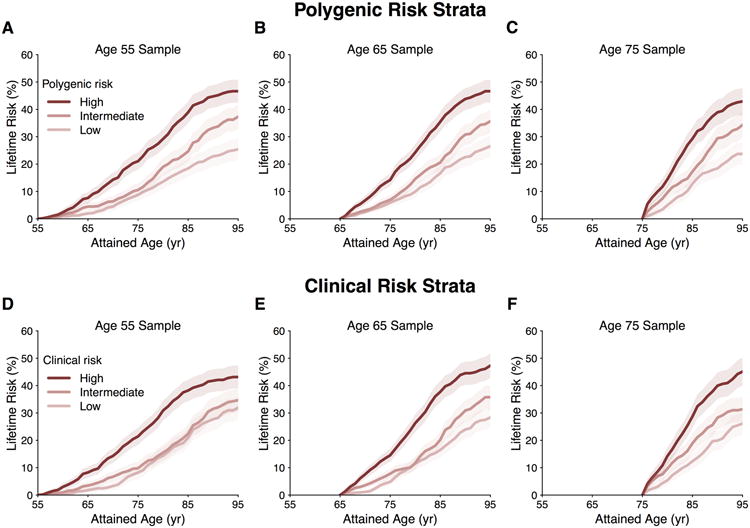

Estimates of lifetime risk of AF are displayed in Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 2. At age 55 years, the overall residual lifetime risk of AF was 37.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 34.6-39.6), and was similar at older attained ages. The participant characteristics stratified by tertile of AF genetic predisposition and clinical risk factor burden are displayed in Supplemental Tables 3-4. The lifetime risk of AF was higher among individuals with greater genetic predisposition to AF. For example, among individuals free of AF at age 55 years, those in the highest tertile of polygenic risk had an estimated lifetime risk of AF of 46.9% (95% CI, 42.7-51.2), whereas those in the lowest tertile had a risk of 25.8% (95% CI, 21.8-29.9, Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 5). Similar graded patterns of AF risk according to genetic predisposition were observed at different attained ages and with shorter time horizons.

Figure 2. Lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) at selected attained ages, adjusted for the competing risk of death.

Lifetime risk of AF in Framingham Heart Study participants for a given attained age is cumulative through age 95 years.

Figure 3. Lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) stratified by polygenic risk or clinical risk factor burden tertiles adjusted for the competing risk of death.

Panels display the lifetime risk of AF in Framingham Heart Study participants stratified by low, intermediate, and high polygenic risk (A-C) or clinical risk factor burden (D-F) at attained ages of 55, 65, and 75 years free of AF.

Similar to analyses of polygenic risk factor burden, the lifetime risk of AF was highest among individuals with a greater burden of clinical AF risk factors. For example, individuals within the highest tertile of clinical AF risk factor burden at age 55 had a lifetime risk of developing AF of 43.1% (95% CI, 38.9-47.3), whereas those in the lowest tertile had a risk of 32.6% (95% CI, 28.2-37.0) (Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 6). However, the lifetime risk of AF was similar between those with intermediate and low clinical risk factor profiles. Comparable patterns were observed at different attained ages and with time horizons of 10, 20, and 30 years of follow-up (Supplemental Table 6).

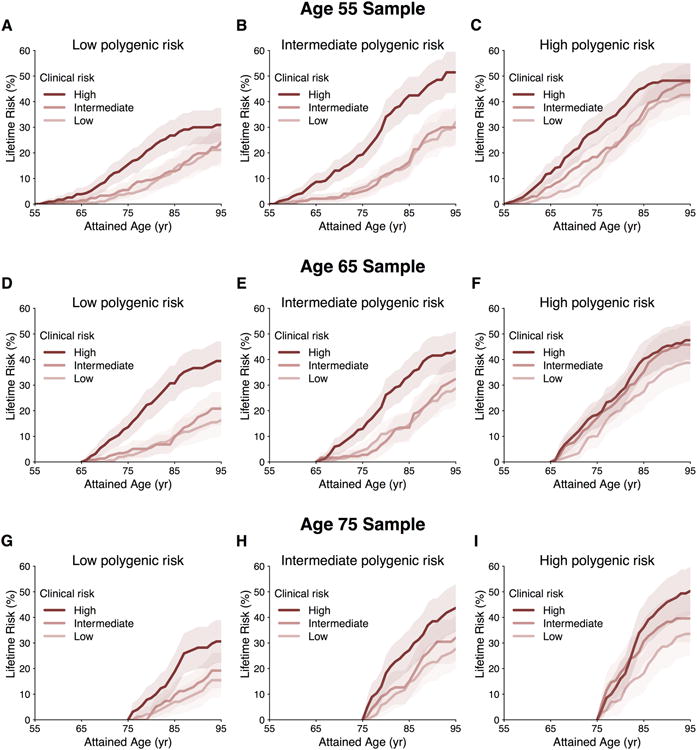

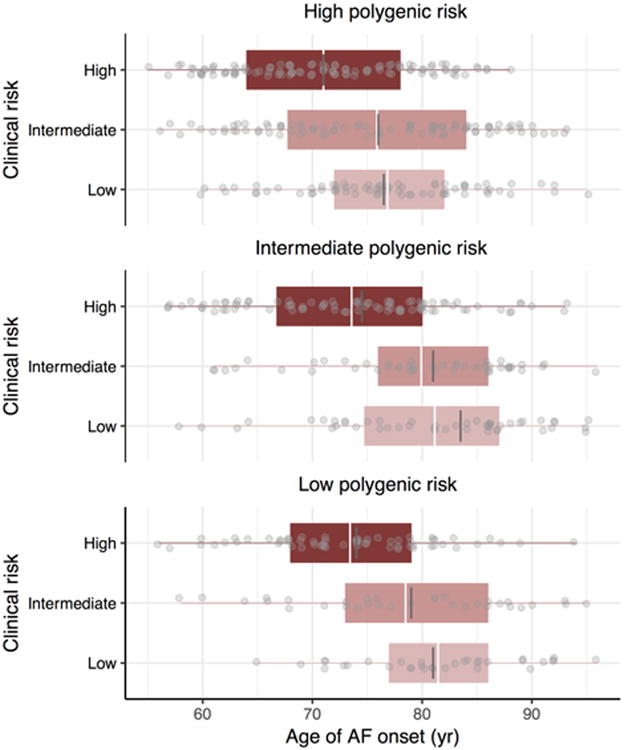

To assess the joint contributions of genetic predisposition and clinical risk factor burden to the lifetime risk of developing AF, we estimated AF risks by tertiles of both polygenic and clinical risk. Among individuals free of AF at age 55 years, those in the lowest polygenic and clinical risk strata had a lifetime risk of AF of 22.3% (95% CI, 15.4-29.1%), whereas those in the highest polygenic and clinical risk tertiles had lifetime risks of AF as high as 48.2% (95% CI 41.3-55.1%, Figure 4). For individuals with low clinical risk factor burden, but high genetic predisposition to AF, the lifetime risk was 43.6% (95% CI, 35.6-51.6), a value comparable to that in other high clinical risk factor burden strata. Substantial gradients of AF risk were consistently observed within strata of polygenic and clinical risk, regardless of the attained age and follow-up time horizons (Supplemental Tables 7-9). We did not observe an interaction between genetic predisposition and clinical risk factor burden in exploratory models in which both were treated as continuous covariates (Supplemental Table 10), but our power to detect an interaction was modest. Among individuals who developed AF, we observed that a lower clinical risk factor burden was associated with a later age of AF onset, regardless of genetic predisposition (P value <0.001 within each tertile of polygenic risk) (Figure 5). We observed an approximately seven year gradient in the age of AF onset across tertiles of clinical risk factor burden when adjusted for polygenic predisposition to AF (age ± standard error; 73.2 ± 0.6 years, 78.6 ± 0.7 years, 80.6 ± 0.7 years, for high, intermediate, and low clinical risk factor burden, respectively).

Figure 4. Lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) stratified by polygenic risk within clinical risk factor burden tertiles adjusted for the competing risk of death.

Panels display the lifetime risk of AF in Framingham Heart Study participants stratified by low, intermediate, and high polygenic risk and clinical risk factor burden at attained ages of 55 years (A-C), 65 years (D-F), and 75 years (G-I).

Figure 5. Age of atrial fibrillation (AF) onset stratified by clinical and polygenic risk.

Gray dots indicate the age of onset of AF in Framingham Heart Study participants free of AF at age 55 years who subsequently developed AF. The white and dark grey lines represent the mean and median age of AF onset, respectively, boxes represent the interquartile range, and whiskers correspond to range of age of onset of AF. The two-side P values were <0.001 for the associations between clinical risk factor burden and age of AF onset within each tertile of polygenic risk score.

Discussion

Our findings illustrate the high lifetime risk of AF and contributions of both genetic and clinical factors in determining long-term AF risk. In the community-based Framingham Heart Study sample comprised of 5,131 individuals with contemporary follow-up, we observed that the lifetime risk of AF was 37.1% after age 55 years. Marked variability in the lifetime risk of AF can be accounted for by both polygenic predisposition and clinical risk factor burden. The lifetime risk of AF ranged from about 20% among individuals in the lowest tertiles of both polygenic and clinical risk to almost 50% among individuals in the highest tertiles of both. On average, a favorable clinical risk profile was associated with later onset of AF regardless of polygenic predisposition to AF.

Our findings have three major implications. First, the observed stratification of AF risk by a score comprised of nearly 1,000 SNPs highlights the feasibility of comprehensive polygenic risk profiling for AF and estimation of lifetime risk based on inherited predisposition. In contrast to the traditional method of creating scores comprised only of the top variant at each disease susceptibility locus,37,38 we estimated polygenic risk by including many SNPs that did not exceed stringent genome-wide significance thresholds, an approach that likely contributed to the considerable degree of risk stratification observed. Our study provides absolute AF risk estimates associated with comprehensively ascertained polygenic risk, and demonstrates that lifetime risk models can be utilized to incorporate genomic risk profiles. Given the increasing ubiquity of genomic data both in the clinical setting and via direct-to-consumer testing, epidemiologically derived estimates are necessary for generating accurate personalized risk assessments.

Second, our observation that individuals with a lower burden of clinical risk factors had a reduced probability of developing AF within polygenic risk strata underscores the potential importance of risk factor modification for attenuating AF risk regardless of inherited predisposition, similar to a recent analysis of coronary heart disease.39 Among individuals who developed AF, a more favorable clinical risk profile was associated with postponement of disease onset, indicating that optimal cardiovascular health may compress the period of exposure to AF. Nevertheless, the fact that individuals with few clinical risk factors but high polygenic risk had about a 40% lifetime probability of developing AF underscores the independent contribution of an inherited predisposition to disease risk.

Modifiable AF risk factors include hypertension, obesity, smoking, diabetes, and obstructive sleep apnea,3,40 the first four of which were included in our assessment of clinical risk factor burden. Risk factor management through lifestyle modification reduces AF burden and severity.41,42 Future analyses are warranted to determine the extent to which dedicated risk factor modification will prevent AF, delay onset, reduce arrhythmia burden, and minimize overall attributable morbidity and mortality across the spectrum of polygenic risk.

Third, the approximately 37% average lifetime risk of AF estimated in our study emphasizes the immense public health impact presented by AF. Prevention of AF is an important goal, particularly when considering the clinical and economic impact of the arrhythmia, limitations of antiarrhythmic and anticoagulant therapy, and increasing prevalence of AF in an era of greater longevity.43-45 Whereas prior reports have suggested that the lifetime risk of AF is about one in four,7-12 the higher lifetime risk estimates in our study may be related to diminished mortality from competing causes of death, greater follow-up during older ages of life when AF risk is greatest, or enhanced surveillance for AF owing to increased awareness of the arrhythmia.46 We anticipate that the true lifetime risk of AF and attributable morbidity are currently underestimated since undiagnosed AF is common.47,48 Utilization of increasingly available mobile cardiac rhythm monitoring technology and wearable sensors is likely to provide refined estimates of the lifetime risk of AF in the future.49,50

In contrast to prior reports demonstrating that AF genetic risk does not add substantively to short-term AF discrimination beyond clinical risk factors,51,52 our current report has several important differences. First, the present paper is focused on residual lifetime probabilities of AF conditional on survival to specified ages, rather than short-term improvements in discrimination of disease risk in a pooled sample. Second, the comprehensive approach for determining AF genetic predisposition we employed is based on a larger and better-powered discovery sample, and relaxed assumptions about both SNP association with AF and linkage disequilibrium, that resulted in a score comprised of about 1,000 variants. In aggregate, the findings highlight the high lifetime risk of developing AF, and the substantial contributions of genetic predisposition and clinical risk factor burden to variability in long-term AF risk. Nevertheless, the clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of genomic profiling remain unclear.

Our study should be interpreted in the context of the study design. The Framingham Heart Study is principally composed of individuals of European ancestry, consequently limiting the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic/racial groups particularly since AF is more prevalent in such individuals.3 The polygenic risk score utilized in our analysis was based on a linear combination of common and low-frequency variants selected using summary level-data from a prior genome-wide association study. The fact that the optimal score utilized in our analysis included many sub-genome-wide threshold SNPs highlights both the polygenic nature of AF and importance of larger, well-powered, multi-ancestry studies to identify the genetic determinants of AF. Future scores based on larger samples that include rare genetic variants and utilize different methods for variant selection or weighting may improve the specificity of scores used to summarize genetic predisposition to AF. We cannot establish causal relations between the specific SNPs and clinical risk factors included in our score and risk of AF. Further refinement of polygenic risk or clinical risk algorithms, and application to larger samples, may further enhance AF short, intermediate, and lifetime risk estimation. Additional clinical risk factors, such as echocardiographic measurements, may be important determinants of disease risk and were not included.

In conclusion, the contributions of genetic predisposition and clinical risk to the development of AF are substantial. Our findings demonstrate the feasibility of assessing AF risk within genetic and clinical risk factor strata, and provide epidemiologic estimates of long-term AF risk. Future studies are warranted to further refine polygenic and clinical risk estimates in additional races and populations.

Supplementary Material

Suplemental Material

Clinical Perspective.

What is new?

- The lifetime risk of developing atrial fibrillation is about 37% after age 55 years, which is considerably greater than prior estimates.

- The lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation varies substantially according to genetic predisposition and clinical risk factor burden.

- Atrial fibrillation develops at an older age among individuals with a favorable clinical risk factor profile, regardless of genetic predisposition.

- Nevertheless, the lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation in individuals with high genetic predisposition was substantial, even when the clinical risk factor burden was low.

What are the clinical implications?

- Individualized projections of lifetime atrial fibrillation risk may be refined by accounting for genetic predisposition and clinical risk factor burden.

- Robust estimation of genetic predisposition to atrial fibrillation is feasible with genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism data.

- Addressing modifiable clinical risk factors might attenuate long-term risk of developing atrial fibrillation or delay the onset of disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants K23HL114724 (Lubitz), 2R01HL092577 (Ellinor, Benjamin, Lunetta), 1R01HL128914 (Ellinor and Benjamin), 1RC1HL101056 and 1R01HL102214 (Benjamin), R01HL104156 and K24HL105780 (Ellinor), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) contract HHSN268201500001I and N01-HC-25195 (Framingham Heart Study), a Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Scientist Development Award 2014105 (Lubitz), Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Research Mentorship Grant 2016077 (Hulme and Lubitz), American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship Award 17POST33660226 (Weng), and American Heart Association Established Investigator Awards 13EIA14220013 (Ellinor) and by the Fondation Leducq 14CVD01 (Ellinor).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Dr. Lubitz receives sponsored research support from Bayer HealthCare, Biotronik, and Boehringer Ingelheim, and has consulted for St. Jude Medical and Quest Diagnostics.

Additional Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank all Framingham Heart Study and UK Biobank participants, staff, and investigators. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 17488.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Ellinor is a principal investigator on a Bayer HealthCare grant to the Broad Institute related to the development of new therapeutics for atrial fibrillation.

References

- 1.Arnar DO, Thorvaldsson S, Manolio TA, Thorgeirsson G, Kristjansson K, Hakonarson H, Stefansson K. Familial aggregation of atrial fibrillation in Iceland. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:708–712. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lubitz SA, Yin X, Fontes JD, Magnani JW, Rienstra M, Pai M, Villalon ML, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Levy D, Larson MG, Ellinor PT, Benjamin EJ. Association between familial atrial fibrillation and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2010;304:2263–2269. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso A, Krijthe BP, Aspelund T, Stepas KA, Pencina MJ, Moser CB, Sinner MF, Sotoodehnia N, Fontes JD, Janssens AC, Kronmal RA, Magnani JW, Witteman JC, Chamberlain AM, Lubitz SA, Schnabel RB, Agarwal SK, McManus DD, Ellinor PT, Larson MG, Burke GL, Launer LJ, Hofman A, Levy D, Gottdiener JS, Kaab S, Couper D, Harris TB, Soliman EZ, Stricker BH, Gudnason V, Heckbert SR, Benjamin EJ. Simple Risk Model Predicts Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation in a Racially and Geographically Diverse Population: the CHARGE-AF Consortium. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000102. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christophersen IE, Rienstra M, Roselli C, Yin X, Geelhoed B, Barnard J, Lin H, Arking DE, Smith AV, Albert CM, Chaffin M, Tucker NR, Li M, Klarin D, Bihlmeyer NA, Low SK, Weeke PE, Muller-Nurasyid M, Smith JG, Brody JA, Niemeijer MN, Dorr M, Trompet S, Huffman J, Gustafsson S, Schurmann C, Kleber ME, Lyytikainen LP, Seppala I, Malik R, Horimoto A, Perez M, Sinisalo J, Aeschbacher S, Theriault S, Yao J, Radmanesh F, Weiss S, Teumer A, Choi SH, Weng LC, Clauss S, Deo R, Rader DJ, Shah SH, Sun A, Hopewell JC, Debette S, Chauhan G, Yang Q, Worrall BB, Pare G, Kamatani Y, Hagemeijer YP, Verweij N, Siland JE, Kubo M, Smith JD, Van Wagoner DR, Bis JC, Perz S, Psaty BM, Ridker PM, Magnani JW, Harris TB, Launer LJ, Shoemaker MB, Padmanabhan S, Haessler J, Bartz TM, Waldenberger M, Lichtner P, Arendt M, Krieger JE, Kahonen M, Risch L, Mansur AJ, Peters A, Smith BH, Lind L, Scott SA, Lu Y, Bottinger EB, Hernesniemi J, Lindgren CM, Wong JA, Huang J, Eskola M, Morris AP, Ford I, Reiner AP, Delgado G, Chen LY, Chen YI, Sandhu RK, Li M, Boerwinkle E, Eisele L, Lannfelt L, Rost N, Anderson CD, Taylor KD, Campbell A, Magnusson PK, Porteous D, Hocking LJ, Vlachopoulou E, Pedersen NL, Nikus K, Orho-Melander M, Hamsten A, Heeringa J, Denny JC, Kriebel J, Darbar D, Newton-Cheh C, Shaffer C, Macfarlane PW, Heilmann-Heimbach S, Almgren P, Huang PL, Sotoodehnia N, Soliman EZ, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, Franco OH, Volker U, Jockel KH, Sinner MF, Lin HJ, Guo X, ISGC MCot, Neurology Working Group of the CC. Dichgans M, Ingelsson E, Kooperberg C, Melander O, Loos RJF, Laurikka J, Conen D, Rosand J, van der Harst P, Lokki ML, Kathiresan S, Pereira A, Jukema JW, Hayward C, Rotter JI, Marz W, Lehtimaki T, Stricker BH, Chung MK, Felix SB, Gudnason V, Alonso A, Roden DM, Kaab S, Chasman DI, Heckbert SR, Benjamin EJ, Tanaka T, Lunetta KL, Lubitz SA, Ellinor PT, Consortium AF. Large-scale analyses of common and rare variants identify 12 new loci associated with atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet. 2017;49:946–952. doi: 10.1038/ng.3843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Low SK, Takahashi A, Ebana Y, Ozaki K, Christophersen IE, Ellinor PT, Consortium AF, Ogishima S, Yamamoto M, Satoh M, Sasaki M, Yamaji T, Iwasaki M, Tsugane S, Tanaka K, Naito M, Wakai K, Tanaka H, Furukawa T, Kubo M, Ito K, Kamatani Y, Tanaka T. Identification of six new genetic loci associated with atrial fibrillation in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2017;49:953–958. doi: 10.1038/ng.3842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beiser A, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Seshadri S, Sullivan LM, Wolf PA. Computing estimates of incidence, including lifetime risk: Alzheimer's disease in the Framingham Study. The Practical Incidence Estimators (PIE) macro. Stat Med. 2000;19:1495–1522. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000615/30)19:11/12<1495::aid-sim441>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, D'Agostino RB, Massaro JM, Beiser A, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;110:1042–1046. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140263.20897.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heeringa J, van der Kuip DA, Hofman A, Kors JA, van Herpen G, Stricker BH, Stijnen T, Lip GY, Witteman JC. Prevalence, incidence and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:949–953. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo Y, Tian Y, Wang H, Si Q, Wang Y, Lip GYH. Prevalence, incidence, and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation in China: new insights into the global burden of atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2015;147:109–119. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandalenakis Z, Von Koch L, Eriksson H, Dellborg M, Caidahl K, Welin L, Rosengren A, Hansson PO. The risk of atrial fibrillation in the general male population: a lifetime follow-up of 50-year-old men. Europace. 2015;17:1018–1022. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magnussen C, Niiranen TJ, Ojeda FM, Gianfagna F, Blankenberg S, Njolstad I, Vartiainen E, Sans S, Pasterkamp G, Hughes M, Costanzo S, Donati MB, Jousilahti P, Linneberg A, Palosaari T, de Gaetano G, Bobak M, den Ruijter HM, Mathiesen E, Jorgensen T, Soderberg S, Kuulasmaa K, Zeller T, Iacoviello L, Salomaa V, Schnabel RB, BiomarCa REC. Sex Differences and Similarities in Atrial Fibrillation Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Mortality in Community Cohorts: Results From the BiomarCaRE Consortium (Biomarker for Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Europe) Circulation. 2017;136:1588–1597. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chao TF, Liu CJ, Tuan TC, Chen TJ, Hsieh MH, Lip GYH, Chen SA. Lifetime Risks, Projected Numbers and Adverse Outcomes in Asian Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: A Report from the Taiwan Nationwide AF Cohort Study. Chest. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke W, Trinidad SB. The Deceptive Appeal of Direct-to-Consumer Genetics. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:564–565. doi: 10.7326/M16-0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benjamin EJ, Chen PS, Bild DE, Mascette AM, Albert CM, Alonso A, Calkins H, Connolly SJ, Curtis AB, Darbar D, Ellinor PT, Go AS, Goldschlager NF, Heckbert SR, Jalife J, Kerr CR, Levy D, Lloyd-Jones DM, Massie BM, Nattel S, Olgin JE, Packer DL, Po SS, Tsang TS, Van Wagoner DR, Waldo AL, Wyse DG. Prevention of atrial fibrillation: report from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop. Circulation. 2009;119:606–618. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.825380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Force ESCT. Gorenek B, Pelliccia A, Benjamin EJ, Boriani G, Crijns HJ, Fogel RI, Van Gelder IC, Halle M, Kudaiberdieva G, Lane DA, Larsen TB, Lip GY, Lochen ML, Marin F, Niebauer J, Sanders P, Tokgozoglu L, Vos MA, Van Wagoner DR, Document r. Fauchier L, Savelieva I, Goette A, Agewall S, Chiang CE, Figueiredo M, Stiles M, Dickfeld T, Patton K, Piepoli M, Corra U, Marques-Vidal PM, Faggiano P, Schmid JP, Abreu A. European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA)/European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (EACPR) position paper on how to prevent atrial fibrillation endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS) Europace. 2017;19:190–225. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardiovascular Disease Knowledge Portal. [Accessed November 12, 2017]; http://broadcvdi.org/

- 17.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, Downey P, Elliott P, Green J, Landray M, Liu B, Matthews P, Ong G, Pell J, Silman A, Young A, Sprosen T, Peakman T, Collins R. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mailman MD, Feolo M, Jin Y, Kimura M, Tryka K, Bagoutdinov R, Hao L, Kiang A, Paschall J, Phan L, Popova N, Pretel S, Ziyabari L, Lee M, Shao Y, Wang ZY, Sirotkin K, Ward M, Kholodov M, Zbicz K, Beck J, Kimelman M, Shevelev S, Preuss D, Yaschenko E, Graeff A, Ostell J, Sherry ST. The NCBI dbGaP database of genotypes and phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1181–1186. doi: 10.1038/ng1007-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dawber TR, Meadors GF, Moore FE., Jr Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1951;41:279–281. doi: 10.2105/ajph.41.3.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. The Framingham offspring study. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110:281–290. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Splansky GL, Corey D, Yang Q, Atwood LD, Cupples LA, Benjamin EJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Fox CS, Larson MG, Murabito JM, O'Donnell CJ, Vasan RS, Wolf PA, Levy D. The Third Generation Cohort of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Framingham Heart Study: design, recruitment, and initial examination. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1328–1335. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schnabel RB, Sullivan LM, Levy D, Pencina MJ, Massaro JM, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Newton-Cheh C, Yamamoto JF, Magnani JW, Tadros TM, Kannel WB, Wang TJ, Ellinor PT, Wolf PA, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ. Development of a risk score for atrial fibrillation (Framingham Heart Study): a community-based cohort study. Lancet. 2009;373:739–745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60443-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellinor PT, Lunetta KL, Albert CM, Glazer NL, Ritchie MD, Smith AV, Arking DE, Muller-Nurasyid M, Krijthe BP, Lubitz SA, Bis JC, Chung MK, Dorr M, Ozaki K, Roberts JD, Smith JG, Pfeufer A, Sinner MF, Lohman K, Ding J, Smith NL, Smith JD, Rienstra M, Rice KM, Van Wagoner DR, Magnani JW, Wakili R, Clauss S, Rotter JI, Steinbeck G, Launer LJ, Davies RW, Borkovich M, Harris TB, Lin H, Volker U, Volzke H, Milan DJ, Hofman A, Boerwinkle E, Chen LY, Soliman EZ, Voight BF, Li G, Chakravarti A, Kubo M, Tedrow UB, Rose LM, Ridker PM, Conen D, Tsunoda T, Furukawa T, Sotoodehnia N, Xu S, Kamatani N, Levy D, Nakamura Y, Parvez B, Mahida S, Furie KL, Rosand J, Muhammad R, Psaty BM, Meitinger T, Perz S, Wichmann HE, Witteman JC, Kao WH, Kathiresan S, Roden DM, Uitterlinden AG, Rivadeneira F, McKnight B, Sjogren M, Newman AB, Liu Y, Gollob MH, Melander O, Tanaka T, Stricker BH, Felix SB, Alonso A, Darbar D, Barnard J, Chasman DI, Heckbert SR, Benjamin EJ, Gudnason V, Kaab S. Meta-analysis identifies six new susceptibility loci for atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet. 2012;44:670–675. doi: 10.1038/ng.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans DM, Visscher PM, Wray NR. Harnessing the information contained within genome-wide association studies to improve individual prediction of complex disease risk. Human molecular genetics. 2009;18:3525–3531. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O'Donovan MC, Sullivan PF, Sklar P. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009;460:748–752. doi: 10.1038/nature08185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lango Allen H, Estrada K, Lettre G, Berndt SI, Weedon MN, Rivadeneira F, Willer CJ, Jackson AU, Vedantam S, Raychaudhuri S, Ferreira T, Wood AR, Weyant RJ, Segre AV, Speliotes EK, Wheeler E, Soranzo N, Park JH, Yang J, Gudbjartsson D, Heard-Costa NL, Randall JC, Qi L, Vernon Smith A, Magi R, Pastinen T, Liang L, Heid IM, Luan J, Thorleifsson G, Winkler TW, Goddard ME, Sin Lo K, Palmer C, Workalemahu T, Aulchenko YS, Johansson A, Zillikens MC, Feitosa MF, Esko T, Johnson T, Ketkar S, Kraft P, Mangino M, Prokopenko I, Absher D, Albrecht E, Ernst F, Glazer NL, Hayward C, Hottenga JJ, Jacobs KB, Knowles JW, Kutalik Z, Monda KL, Polasek O, Preuss M, Rayner NW, Robertson NR, Steinthorsdottir V, Tyrer JP, Voight BF, Wiklund F, Xu J, Zhao JH, Nyholt DR, Pellikka N, Perola M, Perry JR, Surakka I, Tammesoo ML, Altmaier EL, Amin N, Aspelund T, Bhangale T, Boucher G, Chasman DI, Chen C, Coin L, Cooper MN, Dixon AL, Gibson Q, Grundberg E, Hao K, Juhani Junttila M, Kaplan LM, Kettunen J, Konig IR, Kwan T, Lawrence RW, Levinson DF, Lorentzon M, McKnight B, Morris AP, Muller M, Suh Ngwa J, Purcell S, Rafelt S, Salem RM, Salvi E, Sanna S, Shi J, Sovio U, Thompson JR, Turchin MC, Vandenput L, Verlaan DJ, Vitart V, White CC, Ziegler A, Almgren P, Balmforth AJ, Campbell H, Citterio L, De Grandi A, Dominiczak A, Duan J, Elliott P, Elosua R, Eriksson JG, Freimer NB, Geus EJ, Glorioso N, Haiqing S, Hartikainen AL, Havulinna AS, Hicks AA, Hui J, Igl W, Illig T, Jula A, Kajantie E, Kilpelainen TO, Koiranen M, Kolcic I, Koskinen S, Kovacs P, Laitinen J, Liu J, Lokki ML, Marusic A, Maschio A, Meitinger T, Mulas A, Pare G, Parker AN, Peden JF, Petersmann A, Pichler I, Pietilainen KH, Pouta A, Ridderstrale M, Rotter JI, Sambrook JG, Sanders AR, Schmidt CO, Sinisalo J, Smit JH, Stringham HM, Bragi Walters G, Widen E, Wild SH, Willemsen G, Zagato L, Zgaga L, Zitting P, Alavere H, Farrall M, McArdle WL, Nelis M, Peters MJ, Ripatti S, van Meurs JB, Aben KK, Ardlie KG, Beckmann JS, Beilby JP, Bergman RN, Bergmann S, Collins FS, Cusi D, den Heijer M, Eiriksdottir G, Gejman PV, Hall AS, Hamsten A, Huikuri HV, Iribarren C, Kahonen M, Kaprio J, Kathiresan S, Kiemeney L, Kocher T, Launer LJ, Lehtimaki T, Melander O, Mosley TH, Jr, Musk AW, Nieminen MS, O'Donnell CJ, Ohlsson C, Oostra B, Palmer LJ, Raitakari O, Ridker PM, Rioux JD, Rissanen A, Rivolta C, Schunkert H, Shuldiner AR, Siscovick DS, Stumvoll M, Tonjes A, Tuomilehto J, van Ommen GJ, Viikari J, Heath AC, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Province MA, Kayser M, Arnold AM, Atwood LD, Boerwinkle E, Chanock SJ, Deloukas P, Gieger C, Gronberg H, Hall P, Hattersley AT, Hengstenberg C, Hoffman W, Lathrop GM, Salomaa V, Schreiber S, Uda M, Waterworth D, Wright AF, Assimes TL, Barroso I, Hofman A, Mohlke KL, Boomsma DI, Caulfield MJ, Cupples LA, Erdmann J, Fox CS, Gudnason V, Gyllensten U, Harris TB, Hayes RB, Jarvelin MR, Mooser V, Munroe PB, Ouwehand WH, Penninx BW, Pramstaller PP, Quertermous T, Rudan I, Samani NJ, Spector TD, Volzke H, Watkins H, Wilson JF, Groop LC, Haritunians T, Hu FB, Kaplan RC, Metspalu A, North KE, Schlessinger D, Wareham NJ, Hunter DJ, O'Connell JR, Strachan DP, Wichmann HE, Borecki IB, van Duijn CM, Schadt EE, Thorsteinsdottir U, Peltonen L, Uitterlinden AG, Visscher PM, Chatterjee N, Loos RJ, Boehnke M, McCarthy MI, Ingelsson E, Lindgren CM, Abecasis GR, Stefansson K, Frayling TM, Hirschhorn JN. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010;467:832–838. doi: 10.1038/nature09410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ehret GB, Lamparter D, Hoggart CJ, Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits C. Whittaker JC, Beckmann JS, Kutalik Z. A multi-SNP locus-association method reveals a substantial fraction of the missing heritability. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:863–871. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akaike H. A New Look at the Statistical Identification Model. IEEE Trans Automat Contr. 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weng LC, Choi S, Klarin D, Smith JG, Loh PR, Chaffin M, Roselli C, Hulme OL, Lunetta KL, Dupuis J, Benjamin EJ, Newton-Cheh CN, Kathiresan S, Ellinor PT, Lubitz SA. Heritability of Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2017;10:e001838. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.117.001838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfister R, Bragelmann J, Michels G, Wareham NJ, Luben R, Khaw KT. Performance of the CHARGE-AF risk model for incident atrial fibrillation in the EPIC Norfolk cohort. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2015;22:932–939. doi: 10.1177/2047487314544045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christophersen IE, Yin X, Larson MG, Lubitz SA, Magnani JW, McManus DD, Ellinor PT, Benjamin EJ. A comparison of the CHARGE-AF and the CHA2DS2-VASc risk scores for prediction of atrial fibrillation in the Framingham Heart Study. Am Heart J. 2016;178:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shulman E, Kargoli F, Aagaard P, Hoch E, Di Biase L, Fisher J, Gross J, Kim S, Krumerman A, Ferrick KJ. Validation of the Framingham Heart Study and CHARGE-AF Risk Scores for Atrial Fibrillation in Hispanics, African-Americans, and Non-Hispanic Whites. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolek MJ, Graves AJ, Xu M, Bian A, Teixeira PL, Shoemaker MB, Parvez B, Xu H, Heckbert SR, Ellinor PT, Benjamin EJ, Alonso A, Denny JC, Moons KG, Shintani AK, Harrell FE, Jr, Roden DM, Darbar D. Evaluation of a Prediction Model for the Development of Atrial Fibrillation in a Repository of Electronic Medical Records. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:1007–1013. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Last accessed March 22, 2017]; https://www.r-project.org/

- 37.Meigs JB, Shrader P, Sullivan LM, McAteer JB, Fox CS, Dupuis J, Manning AK, Florez JC, Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Cupples LA. Genotype score in addition to common risk factors for prediction of type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2208–2219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kathiresan S, Melander O, Anevski D, Guiducci C, Burtt NP, Roos C, Hirschhorn JN, Berglund G, Hedblad B, Groop L, Altshuler DM, Newton-Cheh C, Orho-Melander M. Polymorphisms associated with cholesterol and risk of cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1240–1249. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khera AV, Emdin CA, Drake I, Natarajan P, Bick AG, Cook NR, Chasman DI, Baber U, Mehran R, Rader DJ, Fuster V, Boerwinkle E, Melander O, Orho-Melander M, Ridker PM, Kathiresan S. Genetic Risk, Adherence to a Healthy Lifestyle, and Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2349–2358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1605086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gami AS, Pressman G, Caples SM, Kanagala R, Gard JJ, Davison DE, Malouf JF, Ammash NM, Friedman PA, Somers VK. Association of atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 2004;110:364–367. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136587.68725.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Lau DH, Mehta AB, Mahajan R, Twomey D, Alasady M, Hanley L, Antic NA, McEvoy RD, Kalman JM, Abhayaratna WP, Sanders P. Aggressive risk factor reduction study for atrial fibrillation and implications for the outcome of ablation: the ARREST-AF cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2222–2231. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abed HS, Wittert GA, Leong DP, Shirazi MG, Bahrami B, Middeldorp ME, Lorimer MF, Lau DH, Antic NA, Brooks AG, Abhayaratna WP, Kalman JM, Sanders P. Effect of weight reduction and cardiometabolic risk factor management on symptom burden and severity in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2050–2060. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim MH, Johnston SS, Chu BC, Dalal MR, Schulman KL. Estimation of total incremental health care costs in patients with atrial fibrillation in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:313–320. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.958165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piccini JP, Hammill BG, Sinner MF, Jensen PN, Hernandez AF, Heckbert SR, Benjamin EJ, Curtis LH. Incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation and associated mortality among Medicare beneficiaries, 1993-2007. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:85–93. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.962688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Writing Group M, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB American Heart Association Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schnabel RB, Yin X, Gona P, Larson MG, Beiser AS, McManus DD, Newton-Cheh C, Lubitz SA, Magnani JW, Ellinor PT, Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. Lancet. 2015;386:154–162. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61774-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Orchard J, Lowres N, Freedman SB, Ladak L, Lee W, Zwar N, Peiris D, Kamaladasa Y, Li J, Neubeck L. Screening for atrial fibrillation during influenza vaccinations by primary care nurses using a smartphone electrocardiograph (iECG): A feasibility study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:13–20. doi: 10.1177/2047487316670255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Svennberg E, Engdahl J, Al-Khalili F, Friberg L, Frykman V, Rosenqvist M. Mass Screening for Untreated Atrial Fibrillation: The STROKESTOP Study. Circulation. 2015;131:2176–2184. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lowres N, Neubeck L, Salkeld G, Krass I, McLachlan AJ, Redfern J, Bennett AA, Briffa T, Bauman A, Martinez C, Wallenhorst C, Lau JK, Brieger DB, Sy RW, Freedman SB. Feasibility and cost-effectiveness of stroke prevention through community screening for atrial fibrillation using iPhone ECG in pharmacies. The SEARCH-AF study. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:1167–1176. doi: 10.1160/TH14-03-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freedman B, Camm J, Calkins H, Healey JS, Rosenqvist M, Wang J, Albert CM, Anderson CS, Antoniou S, Benjamin EJ, Boriani G, Brachmann J, Brandes A, Chao TF, Conen D, Engdahl J, Fauchier L, Fitzmaurice DA, Friberg L, Gersh BJ, Gladstone DJ, Glotzer TV, Gwynne K, Hankey GJ, Harbison J, Hillis GS, Hills MT, Kamel H, Kirchhof P, Kowey PR, Krieger D, Lee VWY, Levin LA, Lip GYH, Lobban T, Lowres N, Mairesse GH, Martinez C, Neubeck L, Orchard J, Piccini JP, Poppe K, Potpara TS, Puererfellner H, Rienstra M, Sandhu RK, Schnabel RB, Siu CW, Steinhubl S, Svendsen JH, Svennberg E, Themistoclakis S, Tieleman RG, Turakhia MP, Tveit A, Uittenbogaart SB, Van Gelder IC, Verma A, Wachter R, Yan BP Collaborators AF-S. Screening for Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the AF-SCREEN International Collaboration. Circulation. 2017;135:1851–1867. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lubitz SA, Yin X, Lin HJ, Kolek M, Smith JG, Trompet S, Rienstra M, Rost NS, Teixeira PL, Almgren P, Anderson CD, Chen LY, Engstrom G, Ford I, Furie KL, Guo X, Larson MG, Lunetta KL, Macfarlane PW, Psaty BM, Soliman EZ, Sotoodehnia N, Stott DJ, Taylor KD, Weng LC, Yao J, Geelhoed B, Verweij N, Siland JE, Kathiresan S, Roselli C, Roden DM, van der Harst P, Darbar D, Jukema JW, Melander O, Rosand J, Rotter JI, Heckbert SR, Ellinor PT, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Consortium AF. Genetic Risk Prediction of Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation. 2017;135:1311–1320. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Everett BM, Cook NR, Conen D, Chasman DI, Ridker PM, Albert CM. Novel genetic markers improve measures of atrial fibrillation risk prediction. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2243–2251. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Suplemental Material