PI-RADS Prostate Imaging – Reporting and Data System: 2015, Version 2 (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2019 Apr 16.

Abstract

The Prostate Imaging – Reporting and Data System Version 2 (PI-RADS™ v2) is the product of an international collaboration of the American College of Radiology (ACR), European Society of Uroradiology (ESUR), and AdMetech Foundation. It is designed to promote global standardization and diminish variation in the acquisition, interpretation, and reporting of prostate multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) examination, and it is based on the best available evidence and expert consensus opinion. It establishes minimum acceptable technical parameters for prostate mpMRI, simplifies and standardizes terminology and content of reports, and provides assessment categories that summarize levels of suspicion or risk of clinically significant prostate cancer that can be used to assist selection of patients for biopsies and management. It is intended to be used in routine clinical practice and also to facilitate data collection and outcome monitoring for research.

Keywords: Prostate mpMRI, Prostate MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging, Prostate, Prostate cancer

1. Introduction

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has been used for noninvasive assessment of the prostate gland and surrounding structures since the 1980s. Initially, prostate MRI was based solely on morphologic assessment using T1-weighted (T1W) and T2-weighted (T2W) pulse sequences, and its role was primarily for locoregional staging in patients with biopsy proven cancer. However, it provided limited capability to distinguish benign pathological tissue and clinically insignificant prostate cancer from significant cancer.

Advances in technology (both in software and hardware) have led to the development of multiparametric MRI (mpMRI), which combines anatomic T2W with functional and physiologic assessment, including diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and its derivative apparent-diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps, dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI, and sometimes other techniques such as in-vivo MR proton spectroscopy. These technologic advances, combined with a growing interpreter experience with mpMRI, have substantially improved diagnostic capabilities for addressing the central challenges in prostate cancer care: 1) Improving detection of clinically significant cancer, which is critical for reducing mortality; and 2) Increasing confidence in benign diseases and dormant malignancies, which are not likely to cause problems in a man’s lifetime, in order to reduce unnecessary biopsies and treatment.

Consequently, clinical applications of prostate MRI have expanded to include, not only locoregional staging, but also tumor detection, localization (registration against an anatomical reference), characterization, risk stratification, surveillance, assessment of suspected recurrence, and image guidance for biopsy, surgery, focal therapy and radiation therapy.

In 2007, recognizing an important evolving role for MRI in assessment of prostate cancer, the AdMeTech Foundation organized the International Prostate MRI Working Group, which brought together key leaders of academic research and industry. Based on deliberations by this group, a research strategy was developed and a number of critical impediments to the widespread acceptance and use of MRI were identified. Amongst these was excessive variation in the performance, interpretation, and reporting of prostate MRI exams. A greater level of standardization and consistency was recommended in order to facilitate multi-center clinical evaluation and implementation.

In response, the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) drafted guidelines, including a scoring system, for prostate MRI known as PI-RADS™ version 1 (PI-RADS™ v1). Since it was publishedin 2012, PI-RADS™ v1 has been validated in certain clinical and research scenarios.

However, experience has also revealed several limitations, in part due to rapid progress in the field. In an effort to make PI-RADS™ standardization more globally acceptable, the American College of Radiology (ACR), ESUR and the AdMeTech Foundation established a Steering Committee to build upon, update and improve upon the foundation of PI-RADS™ v1. This effort resulted in the development PI-RADS™ v2.

PI-RADS™ v2 was developed by members of the PI-RADS Steering Committee, several working groups with international representation, and administrative support from the ACR using the best available evidence and expert consensus opinion. It is designed to promote global standardization and diminish variation in the acquisition, interpretation, and reporting of prostate mpMRI examinations and it is intended to be a “living” document that will evolve as clinical experience and scientific data accrue. PI-RADS™ v2 needs to be tested and validated for specific research and clinical applications.

PI-RADS™ v2 is designed to improve detection, localization, characterization, and risk stratification in patients with suspected cancer in treatment naïve prostate glands. The overall objective is to improve outcomes for patients. The specific aims are to:

- Establish minimum acceptable technical parameters for prostate mpMRI

- Simplify and standardize the terminology and content of radiology reports

- Facilitate the use of MRI data for targeted biopsy

- Develop assessment categories that summarize levels of suspicion or risk and can be used to select patients for biopsies and management (e.g., observation strategy vs. immediate intervention)

- Enable data collection and outcome monitoring

- Educate radiologists on prostate MRI reporting and reduce variability in imaging interpretations

- Enhance interdisciplinary communications with referring clinicians

PI-RADS™ v2 is not a comprehensive prostate cancer diagnosis document and should be used in conjunction with other current resources. For example, it does not address the use of MRI for detection of suspected recurrent prostate cancer following therapy, progression during surveillance, or the use of MRI for evaluation of other parts of the body (e.g. skeletal system) that may be involved with prostate cancer. Furthermore, it does not elucidate or prescribe optimal technical parameters; only those that should result in an acceptable mpMRI examination.

The PI-RADS Steering Committee strongly supports the continued development of promising MRI methodologies for assessment of prostate cancer and local staging (e.g., nodal metastases) utilizing novel and/or advanced research tools not included in PI-RADS™ v2, such as in-vivo MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), diffusional kurtosis imaging (DKI), multiple b-value assessment of fractional ADC, intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM), blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) imaging, intravenous ultra-small superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) agents, and MR-PET. Consideration will be given to incorporating them into future versions of PI-RADS™ as relevant data and experience become available.

2. Section I: Clinical Considerations and Technical Specifications

2.1. Clinical Considerations

2.1.1. Timing of MRI Following Prostate Biopsy

Hemorrhage, manifested as hyperintense signal on T1W, may be present in the prostate gland, most commonly the peripheral zone (PZ) and seminal vesicles, following systematic transrectal ultrasound-guided systematic (TRUS) biopsy and may confound mpMRI assessment. When there is evidence of hemorrhage in the PZ on MR images, consideration may be given to postponing the MRI examination until a later date when hemorrhage has resolved. However, this may not always be feasible or necessary, and clinical practice may be modified as determined by individual circumstances and available resources. Furthermore, if the MRI exam is performed following a negative TRUS biopsy, the likelihood of clinically significant prostate cancer at the site of post biopsy hemorrhage without a corresponding suspicious finding on MRI is low. In this situation, a clinically significant cancer, if present, is likely to be in a location other than that with blood products. Thus, the detection of clinically significant cancer is not likely to be substantially compromised by post biopsy hemorrhage, and there may be no need to delay MRI after prostate biopsy if the primary purpose of the exam is to detect and characterize clinically significant cancer in the gland.

However, post biopsy changes, including hemorrhage and inflammation, may adversely affect the interpretation of prostate MRI for staging in some instances. Although these changes may persist for many months, they tend to diminish over time, and an interval of at least 6 weeks or longer between biopsy and MRI should be considered for staging.

2.1.2. Patient Preparation

At present, there is no consensus concerning all patient preparation issues.

To reduce motion artifact from bowel peristalsis, the use of an antispasmodic agent (e.g. glucagon, scopolamine butylbromide, or sublingual hyoscyamine sulfate) may be beneficial in some patients. However, in many others it is not necessary, and the incremental cost and potential for adverse drug reactions should be taken into consideration.

The presence of stool in the rectum may interfere with placement of an endorectal coil (ERC). If an ERC is not used, the presence of air and/or stool in the rectum may induce artefactual distortion that can compromise DWI quality. Thus, some type of minimal preparation enema administered by the patient in the hours prior to the exam may be beneficial. However, an enema may also promote peristalsis, resulting in increased motion related artifacts in some instances.

The patient should evacuate the rectum, if possible, just prior to the MRI exam.

If an ERC is not used and the rectum contains air on the initial MR images, it may be beneficial to perform the mpMRI exam with the patient in the prone position or to decompress the rectum using suction through a small catheter.

Some recommend that patients refrain from ejaculation for three days prior to the MRI exam in order to maintain maximum distention of the seminal vesicles. However, a benefit for assessment of the prostate and seminal vesicles for clinically significant cancer has not been firmly established.

2.1.3. Patient Information

The following information should be available to the radiologist at the time of MRI exam performance and interpretation:

- Recent serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level and PSA history

- Date and results of prostate biopsy, including number of cores, locations and Gleason scores of positive biopsies (with percentage of core involvement when available).

- Other relevant clinical history, including digital rectal exam (DRE) findings, medications (particularly in the setting of hormones/hormone ablation), prior prostate infections, pelvic surgery, radiation therapy, and family history.

2.2. Technical Specifications

Prostate MRI acquisition protocols should always be tailored to specific patients, clinical questions, management options, and MRI equipment, but T2W, DWI, and DCE should be included in all exams. Unless the MRI exam is monitored and no findings suspicious for clinically significant prostate cancer are detected, at least one pulse sequence should use a field-of-view (FOV) that permits evaluation of pelvic lymph nodes to the level of the aortic bifurcation. The supervising radiologist should be cognizant that superfluous or inappropriate sequences unnecessarily increase exam time and discomfort, and this could negatively impact patient acceptance and compliance.

The technologist performing the exam and/or supervising radiologist should monitor the scan for quality control. If image quality of a pulse sequence is compromised due to patient motion or other reason, measures should be taken to rectify the problem and the sequence should be repeated.

2.2.1. Magnetic Field Strength

The fundamental advantage of 3T compared with 1.5T lies in an increased signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which theoretically increases linearly with the static magnetic field. This may be exploited to increase spatial resolution, temporal resolution, or both. Depending on the pulse sequence and specifics of implementation, power deposition, artifacts related to susceptibility, and signal heterogeneity could increase at 3T, and techniques that mitigate these concerns may result in some increase in imaging time and/or decrease in SNR. However, current state-of-the-art 3T MRI scanners can successfully address these issues, and most members of the PI-RADS Steering Committee agree that the advantages of 3T substantially outweigh these concerns.

There are many other factors that affect image quality besides magnetic field strength, and both 1.5T and 3.0T can provide adequate and reliable diagnostic exams when acquisition parameters are optimized and appropriate contemporary technology is employed. Although prostate MRI at both 1.5 T and 3T has been well established, most members of the PI-RADS Steering Committee prefer, use, and recommend 3T for prostate MRI. 1.5T should be considered when a patient has an implanted device that has been determined to be MR conditional. 1.5T may also be preferred when patients are safe to undergo MRI at 3T, but the location of an implanted device may result in artifact that could compromise image quality (e.g., bilateral metallic hip prosthesis).

The recommendations in this document focus only on 3T and 1.5T MRI scanners since they have been the ones used for clinical validation of mpMRI. Prostate mpMRI at lower magnetic field strengths (<1.5T) is not recommended unless adequate peer reviewed clinical validation becomes available.

2.2.2. Endorectal Coil (ERC)

When integrated with external (surface) phased array coils, endorectal coils (ERCs) increase SNR in the prostate at any magnetic field strength. This may be particularly valuable for high spatial resolution imaging used in cancer staging and for inherently lower SNR sequences, such as DWI and high temporal resolution DCE.

ERCs can also be advantageous for larger patients where the SNR in the prostate may be compromised using only external phased array RF coils. However, use of an ERC may increase the cost and time of the examination, deform the gland, and introduce artifacts. In addition, it may be uncomfortable for patients and increase their reluctance to undergo MRI.

With some 1.5T MRI systems, especially older ones, use of an ERC is considered indispensable for achieving the type of high resolution diagnostic quality imaging needed for staging prostate cancer. At 3T without use of an ERC, image quality can be comparable with that obtained at 1.5 T with an ERC, although direct comparison of both strategies for cancer detection and/or staging is lacking. Importantly, there are many technical factors other than the use of an ERC that influence SNR (e.g., receiver bandwidth, coil design, efficiency of the RF chain), and some contemporary 1.5T scanners that employ a relatively high number of external phased array coil elements and RF channels (e.g., 16 or more) may be capable of achieving adequate SNR in many patients without an ERC.

Credible satisfactory results have been obtained at both 1.5T and 3T without the use of an ERC. Taking these factors into consideration as well as the variability of MRI equipment available in clinical use, the PI-RADS Steering Committee recommends that supervising radiologists to strive to optimize imaging protocols in order to obtain the best and most consistent image quality possible with the MRI scanner used. However, cost, availability, patient preference, and other considerations cannot be ignored.

If air is used to inflate the ERC balloon, it may introduce local magnetic field inhomogeneity, resulting in distortion on DWI, especially at 3T. The extent to which artifacts interfere with MRI interpretation will vary depending on specific pulse sequence implementations, but they can be diminished using correct positioning of the ERC and distention of the balloon with liquids (e.g. liquid perfluorocarbon or barium suspension) that will not result in susceptibility artifacts. When liquid is used for balloon distention, all air should be carefully removed from the ERC balloon prior to placement. Solid, rigid reusable ERCs that avoid the need for inflatable balloons and decrease gland distortion have been developed.

2.2.3. Computer-Aided Evaluation (CAE) Technology

Computer-aided evaluation (CAE) technology using specialized software or a dedicated workstation is not required for prostate mpMRI interpretation. However, CAE may improve workflow (display, analysis, interpretation, reporting, and communication), provide quantitative pharmacodynamic data, and enhance lesion detection and discrimination performance for some radiologists, especially those with less experience interpreting mpMRI exams. CAE can also facilitate integration of MRI data with some forms of MR targeted biopsy systems.

3. Section II: Normal Anatomy and Benign Findings

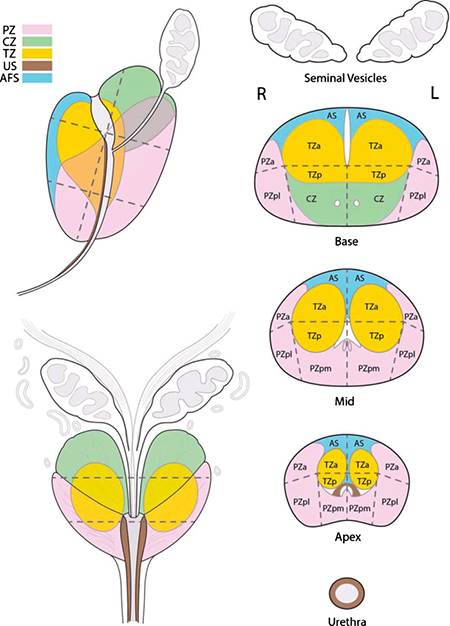

3.1. Normal Anatomy (Figure 1)

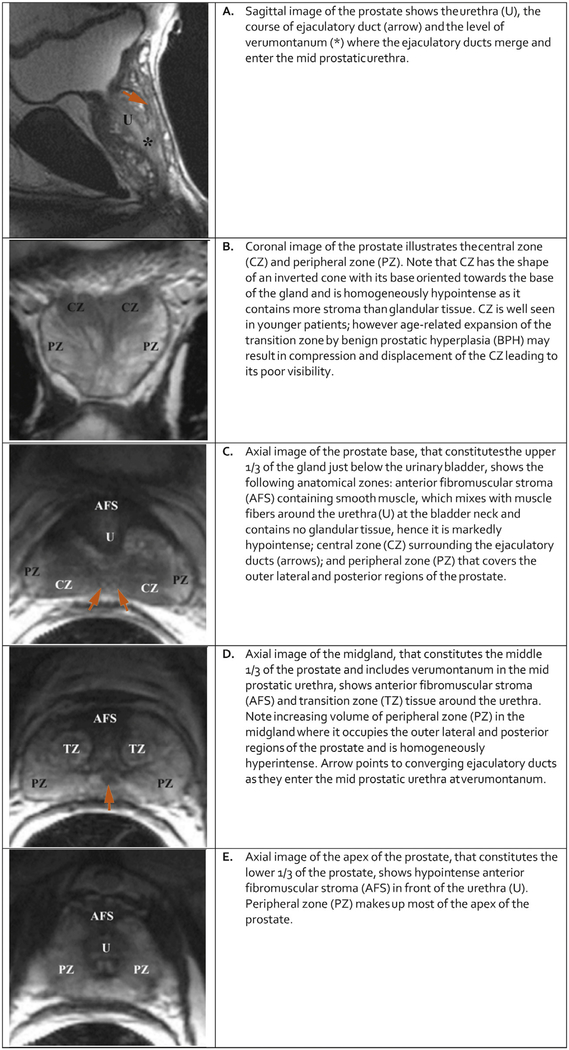

Fig. 1 – Anatomy of the prostate illustrated on T2-weighted imaging (modified from Bonekamp D, Jacobs MA, El-Khouli R, et al. Advancements in MR maging of the prostate: from diagnosis to interventions. Radiographics 2011;31(3):677; with permission.).

From superior to inferior, the prostate consists of the base (just below the urinary bladder), the midgland, and the apex. It is divided into four histologic zones: (a) the anterior fibromuscular stroma, contains no glandular tissue; (b) the transition zone (TZ), surrounding the urethra proximal to the verumontanum, contains 5% of the glandular tissue; (c) the central zone (CZ), surrounding the ejaculatory ducts, contains about 20% of the glandular tissue; and (d) the outer peripheral zone (PZ), contains 70%-80% of the glandular tissue. When benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) develops, the TZ will account for an increasing percentage of the gland volume.

Approximately 70%-75% of prostate cancers originate in the PZ and 20%-30% in the TZ. Cancers originating in the CZ are uncommon, and the cancers that occur in the CZ are usually secondary to invasion by PZ tumors.

Based on location and differences in signal intensity on T2W images, the TZ can often be distinguished from the CZ on MR images. However, in some patients, age-related expansion of the TZ by BPH may result in compression and displacement of the CZ. Use of the term “central gland” to refer to the combination of TZ and CZ is discouraged as it is not reflective of the zonal anatomy as visualized or reported on pathologic specimens.

A thin, dark rim partially surrounding the prostate on T2W is often referred to as the “prostate capsule.” It serves as an important landmark for assessment of extra prostatic extension of cancer. In fact, the prostate lacks a true capsule; rather it contains an outer band of concentric fibromuscular tissue that is inseparable from prostatic stroma. It is incomplete anteriorly and apically.

The prostatic pseudocapsule (sometimes referred to as the “surgical capsule”) on T2W MRI is a thin, dark rim at the interface of the TZ with the PZ. There is no true capsule in this location at histological evaluation, and this appearance is due to compressed prostate tissue.

Nerves that supply the corpora cavernosa are intimately associated with arterial branches from the inferior vesicle artery and accompanying veins that course posterolateral at 5 and 7 o’clock to the prostate bilaterally, and together they constitute the neurovascular bundles. At the apex and base, small nerve branches surround the prostate periphery and penetrate through the capsule, a potential route for extraprostatic extension (EPE) of cancer.

3.2. Sector Map (Appendix II)

The segmentation model used in PI-RADS™ v2 was adapted from a European Consensus Meeting and the ESUR Prostate MRI Guidelines 2012. It employs thirty-nine sectors/regions: thirty-six for the prostate, two for the seminal vesicles, and one for the external urethral sphincter. (Appendix II).

Use of the Sector Map will enable radiologists, urologists, pathologists, and others to localize findings described in MRI reports, and it will be a valuable visual aid for discussions with patients about biopsy and treatment options.

Division of the prostate and associated structures into sectors standardizes reporting and facilitates precise localization for MR-targeted biopsy and therapy, pathological correlation, and research. Since relationships between tumor contours, glandular surface of the prostate, and adjacent structures, such as neurovascular bundles, external urethral sphincter, and bladder neck, are valuable information for periprostatic tissue sparing surgery, the Sector Map may also provide a useful roadmap for surgical dissection at the time of radical prostatectomy.

Either hardcopy (on paper) or electronic (on computer) recording on the Sector Map is acceptable.

For information about the use of the Sector Map, see Section III and Appendix II.

3.3. Benign Findings

Many signal abnormalities within the prostate are benign. The most common include:

3.3.1. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) develops in response to testosterone, after it is converted to di-hydrotestosterone. BPH arises in the TZ, although exophytic and extruded BPH nodules can be found in the PZ. BPH consists of a mixture of stromal and glandular hyperplasia and may appear as bandlike areas and/or encapsulated round nodules with circumscribed margins. Predominantly glandular BPH nodules and cystic atrophy exhibit moderate-marked T2 hyperintensity and are distinguished from malignant tumors by their signal and capsule. Predominantly stromal nodules exhibit T2 hypointensity. Many BPH nodules demonstrate a mixture of signal intensities. BPH nodules may be highly vascular on DCE and can demonstrate a range of signal intensities on DWI.

Although BPH is a benign entity, it may have important clinical implications for biopsy approach and therapy since it can increase gland volume, stretch the urethra, and impede the flow of urine. Since BPH tissue produces prostate-specific antigen (PSA), accurate measurement of gland volume by MRI is an important metric to allow correlation with an individual’s PSA level and to calculate the PSA density (PSA/prostate volume).

3.3.2. Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage in the PZ and/or seminal vesicles is common after biopsy. It appears as focal or diffuse hyperintense signal on T1W and iso-hypointense signal on T2W. However, chronic blood products may appear hypointense on all MR sequences.

3.3.3. Cysts

A variety of cysts can occur in the prostate and adjacent structures. As elsewhere in the body, cysts in the prostate may contain “simple” fluid and appear markedly hyperintense on T2W and dark on T1W. However, they can also contain blood products or proteinaceous fluid, which may demonstrate a variety of signal characteristics, including hyperintense signal on T1W.

3.3.4. Calcifications

Calcifications, if visible, appear as markedly hypointense foci on all pulse sequences.

3.3.5. Prostatitis

Prostatitis affects many men, although it is often sub-clinical. Pathologically, it presents as an immune infiltrate, the character of which depends on the agent causing the inflammation. On MRI, prostatitis can result in decreased signal in the PZ on both T2W and the ADC (apparent diffusion coefficient) map. Prostatitis may also increase perfusion, resulting in a “false positive” DCE result. However, the morphology is commonly band-like, wedge-shaped, or diffuse, rather than focal, round, oval, or irregular, and the decrease in signal on the ADC map is generally not as greatnor as focal as in cancer.

3.3.6. Atrophy

Prostatic atrophy can occur as a normal part of aging or from chronic inflammation. It is typically associated with wedge-shaped areas of low signal on T2W and mildly decreased signal on the ADC map from loss of glandular tissue. The ADC is generally not as low as in cancer, and there is often contour retraction of the involved prostate.

3.3.7. Fibrosis

Prostatic fibrosis can occur after inflammation. It may be associated with wedge- or band-shaped areas of low signal on T2W.

4. Section III: Assessment and Reporting

A major objective of a prostate MRI exam is to identify and localize abnormalities that correspond to clinically significant prostate cancer, and mpMRI is able to detect intermediate to high grade cancers with volumes ≥0.5cc, depending on the location and background tissue within the prostate gland. However, there is no universal agreement of the definition of clinically significant prostate cancer.

In PI-RADS™ v2, the definition of clinically significant cancer is intended to standardize reporting of mpMRI exams and correlation with pathology for clinical and research applications. Based on the current uses and capabilities of mpMRI and MRI-targeted procedures, for PI-RADS™ v2 clinically significant cancer is defined on pathology/histology as Gleason score ≥7 (including 3+4 with prominent but not predominant Gleason 4 component), and/or volume ≥0.5cc, and/or extra prostatic extension (EPE).

PI-RADS™ v2 assessment uses a 5-point scale based on the likelihood (probability) that a combination of mpMRI findings on T2W, DWI, and DCE correlates with the presence of a clinically significant cancer for each lesion in the prostate gland.

PI-RADS™ v2 Assessment Categories

PI-RADS 1 – Very low (clinically significant cancer is highly unlikely to be present)

PI-RADS 2 – Low (clinically significant cancer is unlikely to be present)

PI-RADS 3 – Intermediate (the presence of clinically significant cancer is equivocal)

PI-RADS 4 – High (clinically significant cancer is likely to be present)

PI-RADS 5 – Very high (clinically significant cancer is highly likely to be present)

Assignment of a PI-RADS v2 Assessment Category should be based on mpMRI™ findings only and should not incorporate other factors such as serum prostate specific antigen (PSA), digital rectal exam, clinical history, or choice of treatment. Although biopsy should be considered for PIRADS 4 or 5, but not for PIRADS 1 or 2, PI-RADS™ v2 does not include recommendations for management, as these must take into account other factors besides the MRI findings, including laboratory/clinical history and local preferences, expertise and standards of care. Thus, for findings with PIRADS Assessment Category 2 or 3, biopsy may or may not be appropriate, depending on factors other than mpMRI alone.

It is anticipated that, as evidence continues to accrue in the field of mpMRI and MRI-targeted biopsies and interventions, specific recommendations and/or algorithms regarding biopsy and management will be included in ™ future versions of PI-RADS™.

When T2W and DWI are of diagnostic quality, DCE plays a minor role in determining PIRADS Assessment Category. Absence of early enhancement within a lesion usually adds little information, and diffuse enhancement not localized to a specific T2W or DWI abnormality can be seen in the setting of prostatitis. Moreover, DCE does not contribute to the overall assessment when the finding has a low (PIRADS 1 or 2) or high (PIRADS 4 or 5) likelihood of clinically significant cancer. However, when DWI is PIRADS 3 in the PZ, a positive DCE may increase the likelihood that the finding corresponds to a clinically significant cancer and may upgrade the Assessment Category to PIRADS (Table 1). Likewise when T2W is PIRADS 3 in the TZ, DWI may increase the likelihood that the finding corresponds to a clinically significant cancer and may upgrade the Assessment Category to PIRADS 4 (Table 2).

Table 1 –

PI-RADS Assessment Category for the peripheral zone (PZ)

| DWI | T2W | DCE | PI-RADS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Any* | Any | 1 |

| 2 | Any | Any | 2 |

| 3 | Any | − | 3 |

| + | 4 | ||

| 4 | Any | Any | 4 |

| 5 | Any | Any | 5 |

Table 2 –

PI-RADS Assessment Category for the transition zone (TZ)

| T2W | DWI | DCE | PI-RADS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Any* | Any | 1 |

| 2 | Any | Any | 2 |

| 3 | ≤4 | Any | 3 |

| 5 | Any | 4 | |

| 4 | Any | Any | 4 |

| 5 | Any | Any | 5 |

4.1. Reporting (see Appendix I: Report Templates)

4.1.1. Measurement of the Prostate Gland

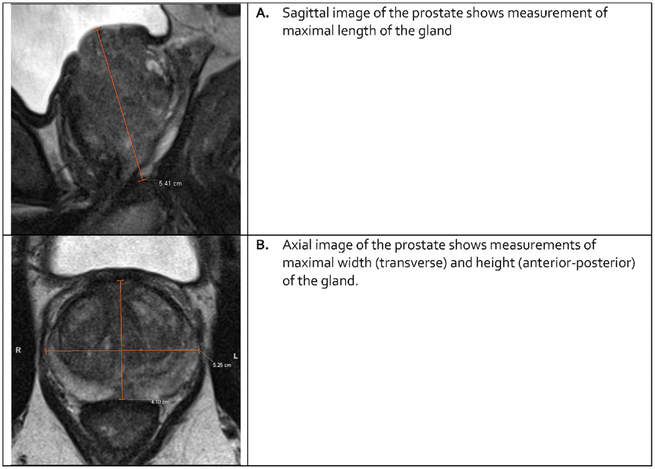

The volume of the prostate gland should always be reported. It may be determined using manual or automated segmentation or calculated using the formula for a conventional prolate ellipse; (maximum AP diameter) × (maximum transverse diameter) × (maximum longitudinal diameter) × 0.52 (Figure 2).

Fig. 2 – Measurements of the prostate on T2-weighted images used for volume assessment with the prolate ellipsoid formula (length × width × height × 0.52).

Prostate volume may also be useful to calculate PSA density (PSA/prostate volume).

4.1.2. Mapping Lesions

Prostate cancer is usually multifocal. The largest tumor focus usually yields the highest Gleason score and is most likely to contribute to extraprostatic extension (EPE) and positive surgical margins.

For PI-RADS™ v2, up to four findings with a PIRADS Assessment Category of 3, 4, or 5 may each be assigned on the Sector Map (Appendix II), and the index (dominant) intraprostatic lesion should be identified. The index lesion is the one with the highest PIRADS Assessment Category. If the highest PIRADS Assessment Category is assigned to two or more lesions, the index lesion should be the one that shows EPE. Thus, a smaller lesion with EPE should be defined as the index lesion despite the presence of a larger tumor with the identical PIRADS Assessment Category. If none of the lesions demonstrate EPE, the largest of the tumors with the highest PIRADS Assessment Category should be considered the index lesion.

If there are more than four suspicious findings, then only the four with the highest likelihood of clinically significant cancer (i.e. highest PIRADS Assessment Category) should be reported. There may be instances when it is appropriate to report more than four suspicious lesions.

Reporting of additional findings with PIRADS Assessment Category 2 or definitely benign findings (e.g. cyst) is optional, but may be helpful to use as landmarks to guide subsequent biopsy or for tracking lesions on subsequent mpMRI exams.

If a suspicious finding extends beyond the boundaries of one sector, all neighboring involved sectors should be indicated on the Sector Map (as a single lesion).

4.1.3. Measurement of Lesions

With current techniques, mpMRI has been shown to underestimate both tumor volume and tumor extent compared to histology, especially for Gleason grade 3. Furthermore, the most appropriate imaging plane and pulse sequence for measuring lesion size on MRI has not been definitely determined, and the significance of differences in lesion size on the various MRI pulse sequences requires further investigation. In the face of these limitations, the PI-RADS Steering Committee nevertheless believes that standardization of measurements will facilitate MR-pathological correlation and research and recommends that the following rules be used for measurements.

The minimum requirement is to report the largest dimension of a suspicious finding on an axial image. If the largest dimension of a suspicious finding is on sagittal and/or coronal images, this measurement and imaging plane should also be reported. If a lesion is not clearly delineated on an axial image, report the measurement on the image which best depicts the finding.

Alternatively, if preferred, lesion volume may be determined using appropriate software, or three dimensions of lesions may be measured so that lesion volume may be calculated (maximum AP diameter) × (maximum transverse diameter) × (maximum cranio-caudal diameter) × 0.52.

In the PZ, lesions should be measured on ADC. In the TZ, lesions should be measured on T2W.

If lesion measurement is difficult or compromised on ADC (for PZ) or T2W (for TZ), measurement should be made on the sequence that shows the lesion best.

In the mpMRI report, the image number(s)/series and sequence used for measurement should be indicated.

4.2. Caveats for Overall Assessment

- In order to facilitate correlation and synchronized scrolling when viewing, it is strongly recommended that imaging plane angle, location, and slice thickness for all sequences (T2W, DWI, and DCE) are identical.

- Changes from prostatitis (including granulomatous prostatitis) can cause signal abnormalities in the PZ with all pulse sequences. Morphology and signal intensity may be helpful to stratify the likelihood of malignancy. In the PZ, mild signal changes on T2W and/or DWI that are not rounded but rather indistinct, linear, lobar, or diffuse are less likely to be malignant.

- For the PZ, DWI is the primary determining sequence (dominant technique). Thus, if the DWI score is 4 and T2W score is 2, PIRADS Assessment Category should be (Table 1).

- For the TZ, T2W is the primary determining sequence. Thus, if the T2W score is 4 and DWI score is 2, PIRADS Assessment Category should be 4 (Table 2).

- Since the dominant factors for PIRADS assessment are T2W for the TZ and DWI for the PZ, identification of the zonal location of a lesion is vital. Areas where this may be especially problematic include the interface of the CZ and PZ at the base of the gland and the interface of the anterior horn of the PZ with TZ and anterior fibromuscular stroma.

- Currently, the capability of reliably detecting and characterizing clinically significant prostate cancer with mpMRI in the TZ is less than that in the PZ.

- Homogeneous or heterogeneous nodules in the TZ that are round/oval, well- circumscribed, and encapsulated are common findings in men aged 40 and above. Often, they demonstrate restricted diffusion and/or focal contrast enhancement, but they are considered to be benign BPH. These do not have to be assigned a PIRADS Assessment Category. Although such nodules may on occasion contain clinically significant prostate cancer, the probability is very low.

- Bilateral symmetric signal abnormalities on any sequence are often due to normal anatomy or benign changes.

- If a component of the mpMRI exam (T2W, DWI, DCE) is technically inadequate or was not performed, it should be assigned PIRADS Assessment Category “X” for that component (Tables 3 and 4). This occurs most commonly with DWI. Since DWI is often crucial for diagnosis of clinically significant cancers in the PZ, inadequate or absent DWI data should usually prompt repeat of this component of the mpMRI examination if the cause of failure can be remedied. If this is not possible, assessment may be accomplished with the other pulse sequences that were obtained using the tables below. However, this is a serious limitation, and it should be clearly acknowledged in the exam report, even if it applies to only one area of the prostate gland.

Table 3 –

PI-RADS Assessment Category Without Adequate DWI for PZ and TZ

| T2W | DWI | DCE | PI-RADS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | X | Any | 1 |

| 2 | X | Any | 2 |

| 3 | X | − | 3 |

| + | 4 | ||

| 4 | X | Any | 4 |

| 5 | X | Any | 5 |

Table 4 –

PI-RADS Assessment Category Without Adequate DCE for TZ

| T2W | DWI | DCE | PI-RADS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Any | X | 1 |

| 2 | Any | X | 2 |

| 3 | ≤4 | X | 3 |

| 5 | X | 4 | |

| 4 | Any | X | 4 |

| 5 | Any | X | 5 |

If both DWI and DCE are inadequate or absent, assessment should be limited to staging for determination of EPE.

5. Section IV: Multiparametric MRI (mpMRI)

5.1. T1-Weighted (T1W) and T2-Weighted (T2W)

Both T1W and T2W sequences should be obtained for all prostate MR exams. T1W images are used primarily to determine the presence of hemorrhage within the prostate and seminal vesicles and to delineate the outline of the gland. T1W images may also useful for detection of nodal and skeletal metastases, especially following intravenous administration of a gadolinium-based contrast agent (GBCA).

T2W images are used to discern prostatic zonal anatomy, assess abnormalities within the gland, and to evaluate for seminal vesicle invasion, EPE, and nodal involvement.

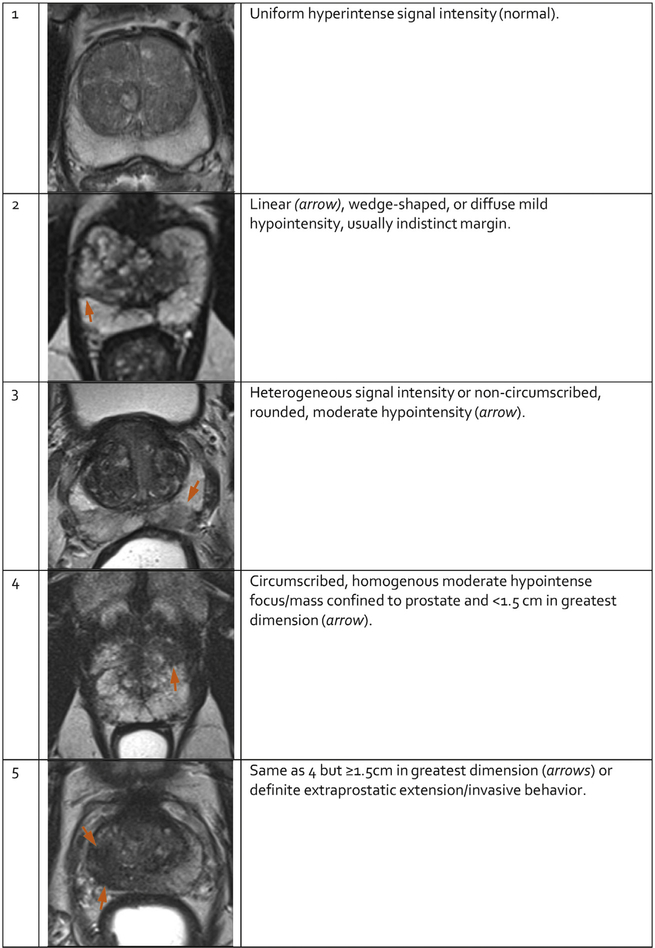

On T2W images, clinically significant cancers in the PZ (Figure 3) usually appear as round or ill- defined hypointense focal lesions. However, this appearance is not specific and can be seen in various conditions such as prostatitis, hemorrhage, glandular atrophy, benign hyperplasia, biopsy related scars, and after therapy (hormone, ablation, etc.).

Fig. 3 – PI-RADS assessment for peripheral zone on T2-weighted imaging.

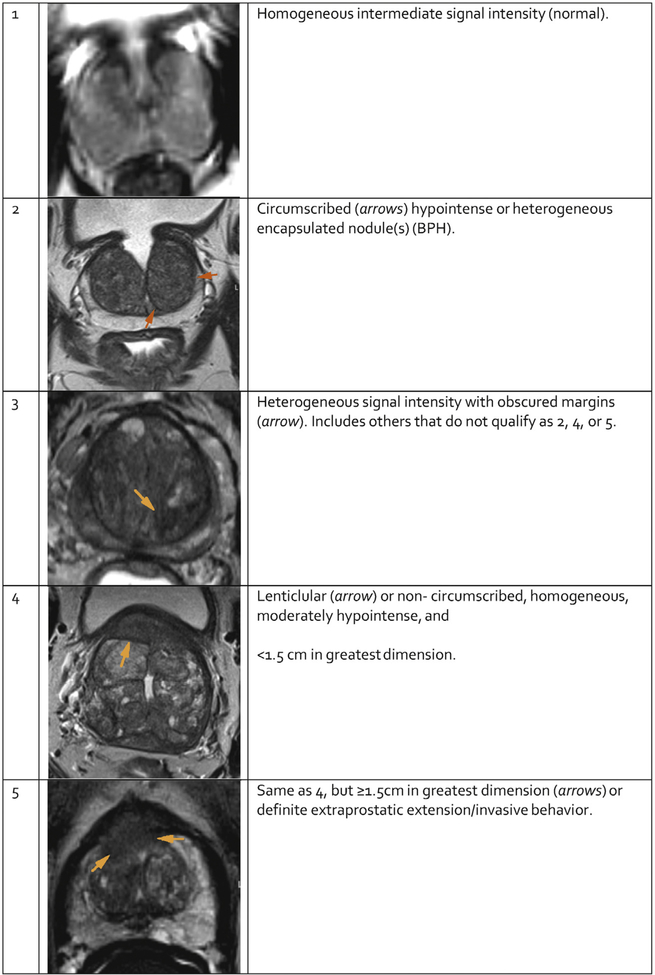

The T2W features of TZ tumors (Figure 4) include noncircumscribed homogeneous, moderately hypointense lesions (“erased charcoal” or “smudgy fingerprint” appearance), spiculated margins, lenticular shape, absence of a complete hypointense capsule, and invasion of the urethral sphincter and anterior fibromuscular stroma. The more features present, the higher the likelihood of a clinically significant TZ cancer.

Fig. 4 – PI-RADS assessment for transition zone on T2-weighted imaging.

TZ cancers may be difficult to identify on T2W images since the TZ is often composed of variable amounts of glandular (T2-hyperintense) and stromal (T2-hypointense) tissue intermixed with each other, thus demonstrating heterogeneous signal intensity. Areas where benign stromal elements predominate may mimic or obscure clinically significant cancer.

Both PZ and TZ cancers may extend across anatomical boundaries. Invasive behavior is noted when there is extension within the gland (i.e. across regional parts of the prostate), into the seminal vesicles, or outside the gland (EPE).

5.1.1. Technical Specifications

5.1.1.1. T2W.

Multiplanar (axial, coronal, and sagittal) T2W images are usually obtained with 2D RARE (rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement) pulse sequences, more commonly known as fast-spin-echo (FSE) or turbo-spin-echo (TSE). In order to avoid blurring, excessive echo train lengths should be avoided.

- Slice thickness: 3 mm, no gap. Locations should be the same as those used for DWI and DCE

- FOV: generally 12–20 cm to encompass the entire prostate gland and seminal vesicles

- In plane dimension: ≤0.7 mm (phase) × ≤0.4 mm (frequency)

3D axial acquisitions may be used as an adjunct to 2D acquisitions. If acquired using isotropic voxels, 3D acquisitions may be particularly useful for visualizing detailed anatomy and distinguishing between genuine lesions and partial volume averaging effects. However, the soft tissue contrast is not identical and in some cases may be inferior to that seen on 2D T2W images, and the in-plane resolution may be lower than their 2D counterpart.

5.1.1.2. T1W.

Axial T1W images of the prostate may be obtained with or without fat suppression using spin echo or gradient echo sequences. Locations should be the same as those used for DWI and DCE, although lower spatial resolution compared to T2W may be used to decrease acquisition time or increase anatomic coverage.

5.1.2. PI-RADS Assessment for T2W (Tables 5 and 6)

Table 5 –

PI-RADS Assessment for T2W for PZ

| Score | Peripheral Zone (PZ) |

|---|---|

| 1 | Uniform hyperintense signal intensity (normal) |

| 2 | Linear or wedge-shaped hypointensity or diffuse mild hypointensity, usually indistinct margin |

| 3 | Heterogeneous signal intensity or non-circumscribed, rounded, moderate hypointensity |

| Includes others that do not qualify as 2, 4, or 5 | |

| 4 | Circumscribed, homogenous moderate hypointense focus/mass confined to prostate and <1.5 cm in greatest dimension |

| 5 | Same as 4 but ≥1.5 cm in greatest dimension or definite extra prostatic extension/invasive behavior |

Table 6 –

PI-RADS Assessment for T2W for TZ

| Score | Transition Zone (TZ) |

|---|---|

| 1 | Homogeneous intermediate signal intensity (normal) |

| 2 | Circumscribed hypointense or heterogeneous encapsulated nodule(s) (BPH) |

| 3 | Heterogeneous signal intensity with obscured margins Includes others that do not qualify as 2, 4, or 5 |

| 4 | Lenticular or non-circumscribed, homogeneous, moderately hypointense, and <1.5cm in greatest dimension |

| 5 | Same as 4, but ≥1.5 cm in greatest dimension or definite extraprostatic extension/invasive behavior |

5.2. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI)

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) reflects the random motion of water molecules and is a key component of the prostate mpMRI exam. It should include an ADC map and high b-value images.

The ADC map is a display of ADC values for each voxel in an image. In most current clinical implementations, it uses two or more b-values and a monoexponential model of signal decay with increasing b-values to calculate ADC values. Most clinically significant cancers have restricted/impeded diffusion compared to normal tissues and, thus, appear hypointense on grey-scale ADC maps. Although ADC values have been reported to correlate inversely with histologic grades, there is considerable overlap between BPH, low grade cancers, and high grade cancers. Furthermore, ADC calculations are influenced by choice of b-values and have been inconsistent across vendors. Thus, qualitative visual assessment is often used as the primary method to assess ADC. Nevertheless, ADC values, using a threshold of 750–900 μm2/sec, may assist differentiation between benign and malignant prostate tissues in the PZ, with ADC values below the threshold correlating with clinically significant cancers.

“High b-value” images utilize a b-value between ≥1400sec/mm2. They display preservation of signal in areas of restricted/impeded diffusion compared with normal tissues, which demonstrate diminished signal due to greater diffusion between applications of gradients with different b-values. Compared to ADC maps alone, conspicuity of clinically significant cancers is sometimes improved on high b-value images, especially in those adjacent to or invading the anterior fibromuscular stroma, in a subcapsular location, and at the apex and base of the gland. High bvalue images can be obtained in one of two ways: either directly by acquiring a high b-value DWI sequence (requiring additional scan time), or by calculating (synthesizing) the high b-value image by extrapolation from the acquired lower b-value data used to create the ADC map (potentially less prone to artifacts because it avoids the longer TEs required to accommodate the strong gradient pulses needed for high b-value acquisitions). As the b-value increases, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) decreases, so that the optimum high b- value may be dependent on magnetic field strength, software, and manufacturer. Thus, there is no currently widely accepted optimal “high b-value”, but if adequate SNR permits, b-values of 1400–2000sec/mm2 or higher seem to be advantageous.

5.2.1. Technical Specifications

Free-breathing spin echo EPI sequence combined with spectral fat saturation is recommended.

- TE: ≤90 msec; TR: ≥3 000 msec

- Slice thickness: ≤4 mm, no gap. Locations should match or be similar to those used for T2W and DCE

- FOV: 16–22 cm

- In plane dimension: ≤2.5 mm phase and frequency

For ADC maps, if only two b-values can be acquired due to time or scanner constraints, it is preferred that the lowest b-value should be set at 50–100 sec/mm2 and the highest should be 800–1000sec/mm2. Additional b-values between 100 and 1000 may provide more accurate ADC calculations and estimations of extrapolated high b-value images (>1400sec/mm2).

Information regarding perfusion characteristics of tissues may be obtained with additional b-values ranging from 0 to 500 sec/mm2,

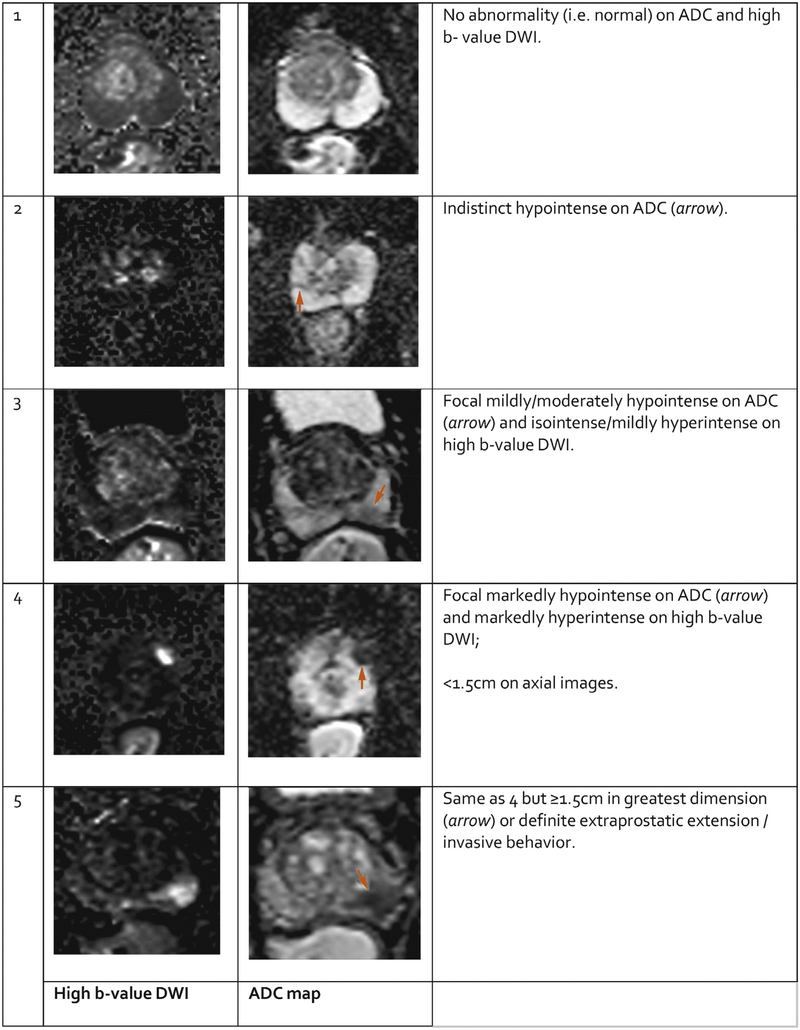

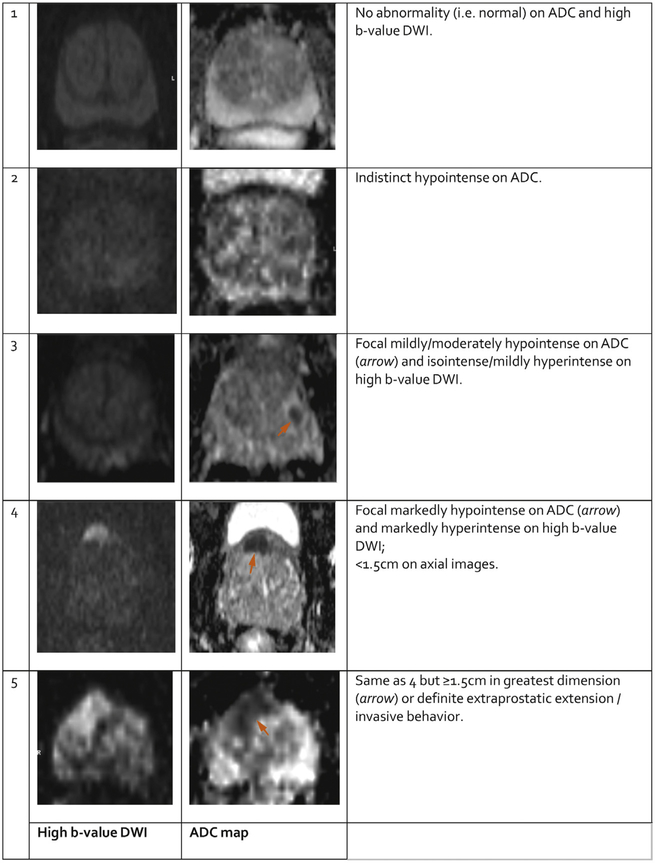

5.2.2. PI-RADS Assessment of DWI (Figures 5 and 6 and Table 7)

Fig. 5 – PI-RADS assessment for peripheral zone on diffusion weighted imaging.

Fig. 6 – PI-RADS assessment for transition zone on diffusion weighted imaging.

Table 7 –

PI-RADS Assessment for DWI for both PZ and TZ

| Score | Peripheral Zone (PZ) or Transition Zone (TZ) |

|---|---|

| 1 | No abnormality (i.e., normal) on ADC and high b-value DWI |

| 2 | Indistinct hypointense on ADC |

| 3 | Focal mildly/moderately hypointense on ADC and isointense/ mildly hyperintense on high b-value DWI. |

| 4 | Focal markedly hypontense on ADC and markedly hyperintense on high b-value DWI; <1.5 cm in greatest dimension |

| 5 | Same as 4 but ≥1.5cm in greatest dimension or definite extraprostatic extension/invasive behavior |

Signal intensity in a lesion should be visually compared to the average signal of “normal” prostate tissue in the histologic zone in which it is located.

5.2.3. Caveats for DWI

- Findings on DWI should always be correlated with T2W, T1W, and DCE.

- Due to technical issues, units of signal intensity have not been standardized across different MRI scanners and are not analogous to Hounsfield units of density on CT. As a result, there are no standardized “prostate windows” that are applicable to images obtained from all MRI scanners. Clinically significant cancers have restricted/impeded diffusion and should appear as hypointense on the ADC map. It is strongly recommended that ADC maps from a particular scanner are set to portray clinically significant prostate cancers so that they appear markedly hypointense on ADC maps, and they should be consistently viewed with the same contrast (window width and level) settings. Guidance from radiologists who have experience with a particular vendor or scanner may be helpful.

- Color-coded maps of ADC may assist in standardization of viewing and assessing images from a particular scanner or vendor, but they will not obviate the concerns with reproducibility of quantitative ADC values.

- Benign findings and some normal anatomy (e.g., calculi and other calcifications, areas of fibrosis or dense fibromuscular stroma, and some blood products, usually from prior biopsies) may exhibit no or minimal signal on both T2W and ADC because there is insufficient signal. However, in contrast to clinically significant prostate cancers, these entities will also be markedly hypointense on all DWI images.

- Some BPH nodules in the TZ are not clearly encapsulated, and they may exhibit hypointensity on ADC maps and hyperintensity on high b-value DWI. Although morphologic features may assist assessment in some cases, this is currently a recognized limitation of mpMRI diagnosis.

- An encapsulated, circumscribed, round nodule in the PZ is likely an extruded BPH nodule, even if it is hypointense on ADC. PIRADS Assessment Category for this finding should be 2.

5.3. Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced (DCE) MRI

DCE MRI is defined as the acquisition of rapid T1W gradient echo scans before, during and after the intravenous administration of a low molecular weight gadoliniumbased contrast agent (GBCA). As with many other malignancies following bolus injection of a GBCA, prostate cancers often demonstrate early enhancement compared to normal tissue. However, the actual kinetics of prostate cancer enhancement are quite variable and heterogeneous.

Some malignant tumors demonstrate early washout, while others retain contrast longer. Furthermore, enhancement alone is not definitive for clinically significant prostate cancer, and absence of early enhancement does not exclude the possibility.

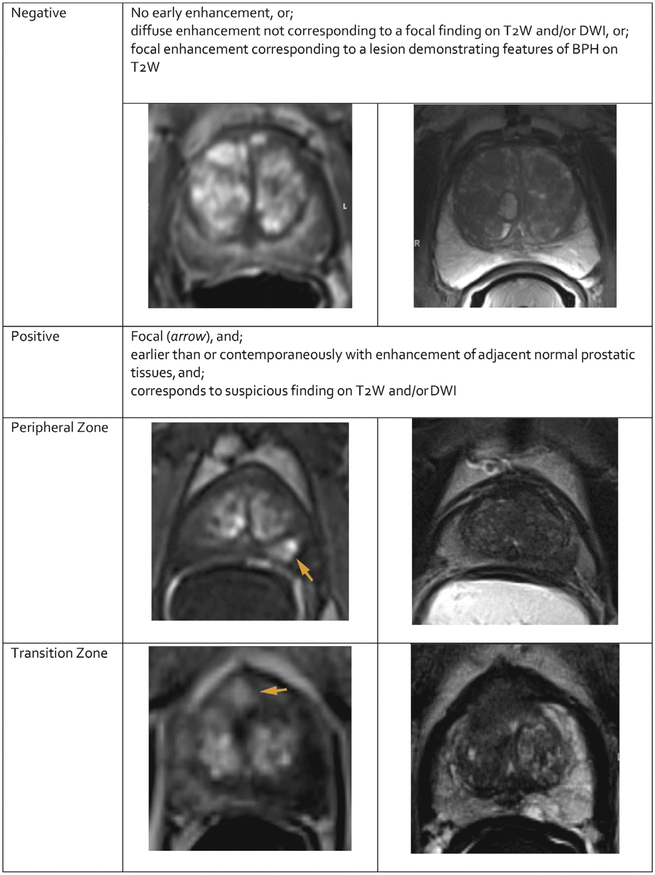

DCE should be included in all prostate mpMRI exams so as not to miss some small significant cancers. The DCE data should always be closely inspected for focal early enhancement. If found, then the corresponding T2W and DWI images should be carefully interrogated for a corresponding abnormality. At present, the added value DCE is not firmly established, and most published data show that the added value of DCE over and above the combination of T2W and DWI is modest. Thus, although DCE is an essential component of the mpMRI prostate examination, its role in determination of PI-RADS™ v2 Assessment Category is secondary to T2W and DWI.

DCE is positive (Figure 7) when there is enhancement that is focal, earlier or contemporaneous with enhancement of adjacent normal prostatict issues, and usually corresponds to a suspicious finding on T2W and/or DWI. Positive enhancement in a lesion usually occurs within 10 seconds of the appearance of the injected GBCA in the femoral arteries (depending on temporal resolution used to acquire the images, injection rate, cardiac output, and other factors).

Fig. 7 – PI-RADS assessment for dynamic contrast enhanced MRI.

The most widely available method of analyzing DCE is direct visual assessment of the individual DCE time-points at each slice location by either manually scrolling or using cine mode. Visual assessment of enhancement may be improved with fat suppression or subtraction techniques (especially in the presence of blood products that are hyperintense on pre-contrast enhanced T1W). Visual assessment of enhancement may also be assisted with a parametric map which color-codes enhancement features within a voxel (e.g., slope and peak). However, any suspicious finding on subtracted images or a parametric map should always be confirmed on the source images.

Considerable effort has gone into “curve typing” (i.e., plotting the kinetics of a lesion as a function of signal vs. time). However, there is great heterogeneity in enhancement characteristics of prostate cancers, and at present there is little evidence in the literature to support the use of specific curve types. Another approach is the use of compartmental pharmacokinetic modeling, which incorporates contrast media concentration rather than raw signal intensity and an arterial input function to calculate time constants for the rate of contrast agent wash-in (Ktrans) and wash-out (kep). Commercial software programs are available that produce “maps” of Ktrans and keep and may improve lesion conspicuity. Although pharmacodynamic (PD) analysis may provide valuable insights into tumor behavior and biomarker measurements for drug development, the PI-RADS Steering Committee believes there is currently insufficient peer reviewed published data or expert consensus to support routine adoption of this method of analysis for clinical use.

Thus, for PI-RADS™ v2, a “positive” DCE MRI lesion is one where the enhancement is focal, earlier or contemporaneous with enhancement of adjacent normal prostatic tissues, and corresponds to a finding on T2W and/or DWI. In the TZ, BPH nodules frequently enhance early, but they usually exhibit a characteristic benign morphology (round shape, well circumscribed). A “negative” DCE MRI lesion is one that either does not enhance early compared to surrounding prostate or enhances diffusely so that the margins of the enhancing area do not correspond to a finding on T2W and/or DWI.

5.3.1. Technical Specifications

DCE is generally carried out for several minutes to assess the enhancement characteristics. In order to detect early enhancing lesions in comparison to background prostatic tissue, temporal resolution should be <10 seconds and preferably <7 seconds per acquisition in order to depict focal early enhancement. Fat suppression and/or subtractions are recommended.

- Although either a 2D or 3D T1 gradient echo (GRE) sequence may be used, 3D is preferred.

- TR/TE: <100msec/ <5msec

- Slice thickness: 3 mm, no gap. Locations should be the same as those used for DWI and DCE.

- FOV: encompass the entire prostate gland and seminal vesicles

- In plane dimension: ≤2 mm × ≤2 mm

- Temporal resolution: ≤15 sec (<7 sec is preferred)

- Total observation rate: ≥2 min

- Dose: 0.1mmol/kg standard GBCA or equivalent high relativity GBCA

Injection rate: 2–3cc/sec starting with continuous image data acquisition (should be the same for all exams)

5.3.2. PI-RADS Assessment for DCE (Table 8)

Table 8 –

PI-RADS Assessment for DCE

| Score | Peripheral Zone (PZ) or Transition Zone (TZ) |

|---|---|

| (−) | no early enhancement, or diffuse enhancement not corresponding to a focal finding on T2W and/or DWI or focal enhancement corresponding to a lesion demonstrating features of BPH on T2W |

| (+) | focal, and; earlier than or contemporaneously with enhancement of adjacent normal prostatic tissues, and corresponds to suspicious finding on T2W and/or DWI |

5.3.2.1. Caveats for DCE.

- DCE should always be interpreted with T2W and DWI; Focal enhancement in clinically significant cancer usually corresponds to focal findings on T2W and/or DWI.

- DCE may be helpful when evaluation of DWI in part or all of the prostate is technically compromised (i.e., Assessment Category X) and when prioritizing multiple lesions in the same patient (e.g., all other factors being equal, the largest DCE positive lesion may be considered the index lesion).

- Diffusely positive DCE is usually attributed to inflammation (e.g., prostatitis). Although infiltrating cancers may also demonstrate diffuse enhancement, these are uncommon and usually demonstrate an abnormality on the corresponding T2W and/or DWI.

- There are instances where histologically sparse prostate cancers are intermixed with benign prostatic tissues. They may be occult on T2W and DWI, and anecdotally may occasionally be apparent only on DCE. However, these are usually lower grade tumors, and the enhancement might, in some cases, be due to concurrent prostatitis.

6. Section V: Staging

MRI is useful for determination of the T stage, either confined to the gland (<T2 disease) or extending beyond the gland (>T3 disease).

The apex of the prostate should be carefully inspected. When cancer involves the external urethral sphincter, there is surgical risk of cutting the sphincter, resulting in compromise of urinary competence. Tumor in this region may also have implications for radiation therapy.

High spatial resolution T2W imaging is required for accurate assessment of extraprostatic extension (EPE), which includes assessment of neurovascular bundle involvement and seminal vesicle invasion. These may be supplemented by high spatial resolution contrast-enhanced fat suppressed T1W.

The features of seminal vesicle invasion include focal or diffuse low T2W signal intensity and/or abnormal contrast enhancement within and/or along the seminal vesicle, restricted diffusion, obliteration of the angle between the base of the prostate and the seminal vesicle, and demonstration of direct tumor extension from the base of the prostate into and around the seminal vesicle.

Imaging features used to assess for EPE include asymmetry or invasion of the neurovascular bundles, a bulging prostatic contour, an irregular or spiculated margin, obliteration of the rectoprostatic angle, a tumor-capsule interface of greater than 1.0 cm, breach of the capsule with evidence of direct tumor extension or bladder wall invasion.

The next level of analysis is that of the pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. The detection of abnormal lymph nodes on MRI is currently limited to size, morphology and shape, and enhancement pattern. In general, lymph nodes over 8 mm in short axis dimension are regarded as suspicious, although lymph nodes that harbor metastases are not always enlarged. Nodal groups that should be evaluated include: common femoral, obturator, external iliac, internal iliac, common iliac, pararectal, presacral, paracaval, and para-aortic to the level of the aortic bifurcation.

Images should be assessed for the presence of skeletal metastases.

SECTOR MAP CREDIT.

The prostate sector map was modified by David A. Rini, Department of Art as Applied to Medicine, Johns Hopkins University. It is based on previously published figures by Villers et al (Curr Opin Urol 2009;19:274–82) and Dickinson et al (Eur Urol 2011;59:477–94) with anatomical correlation to the normal histology of the prostate by McNeal JE (Am J Surg Pathol 1988 Aug;12:619–33).

Acknowledgements:

Administration

Mythreyi Chatfield

Steering Committee American College of Radiology, Reston

Jeffrey C. Weinreb:

Co-Chair Yale School of Medicine, New Haven

Jelle O. Barentsz:

Co-Chair Radboudumc, Nijmegen

Peter L. Choyke National Institutes of Health, Bethesda

Franc¸ ois Cornud Rene´ Descartes University, Paris

Masoom A. Haider University of Toronto, Sunnybrook

Health Sciences Ctr

Katarzyna J. Macura Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

Daniel Margolis University of California, Los Angeles

Mitchell D. Schnall University of Pennsylvania,

Philadelphia

Faina Shtern AdMeTech Foundation, Boston

Clare M. Tempany Harvard University, Boston

Harriet C. Thoeny University Hospital of Bern

Sadna Verma

Working Groups:

T1 and T2

Clare Tempany: Chair University of Cincinnati

Robert Mulkern Harvard University, Boston

Baris Turkbey National Institutes of Health, Bethesda

Alexander Kagan Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital, New York

Alberto Vargas Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital, New York

DCE

Pete Choyke: Chair-DCE

Aytekin Oto University of Chicago

Masoom A. Haider University of Toronto, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Ctr

Francois Cornud Rene Descartes University, Paris

Fiona Fennessey Harvard University, Boston

Sadna Verma University of Cincinnati

Pete Choyke National Institutes of Health, Bethesda

Jurgen Fu¨ tterer

DWI

Francois Cornud: Chair Radboudumc, Nijmegen

Anwar Padhani Mount Vernon Cancer Centre, Middlesex

Daniel Margolis University of California, Los Angeles

Aytekin Oto University of Chicago

Harriet C. Thoeny University Hospital of Bern

Sadna Verma University of Cincinnati

Peter Choyke National Institutes of Health, Bethesda

Jelle Barentsz Radboudumc, Nijmegen

Masoom A. Haider University of Toronto, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Ctr

Clare M. Tempany Harvard University, Boston

Geert Villeirs Ghent University Hospital

Baris Turkbey

Sector Diagram National Institutes of Health, Bethesda

David A. Rini J

Other Reviewers/

Contributors ESUR Johns Hopkins University

Alex Kirkham University College London Hospitals

Clare Allen University College London Hospitals

Nicolas Grenier University Boordeaux

Valeria Panebianco Sapienza University of Rome

Geert Villeirs Ghent University Hospital

Mark Emberton University College London Hospitals

Jonathan Richenberg The Montefiore Hospital, Brighton Phillippe Puech

USA Lille University School of Medicine

Martin Cohen Rolling Oaks Radiology, California

John Feller Desert Medical Imaging, Indian Wells, Ca

Daniel Cornfeld Yale School of Medicine, New Haven

Art Rastinehad Mount Sinai School of Medicine

John Leyendecker University of Texas Southwestern

Medical Center, Dallas

Ivan Pedrosa University of Texas Southwestern

Medical Center, Dallas

Andrei Puryska Cleveland Clinic

Andrew Rosenkrantz New York University

Peter Humphey Yale School of Medicine, New Haven Preston Sprenkle

China Yale School of Medicine, New Haven Liang Wang

Australia Tongji Medical College

Les Thompson Wesley Hospital, Brisbane

Financial disclosures: Jeffrey C. Weinreb certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None

Appendix I

Report Templates (this section is under construction)

Standard (Free Text) Report

Structured Report

Appendix II

Sector Map

The segmentation model used in PI-RADS™ v2 employs thirty-nine sectors/regions: thirty-six for the prostate, two for the seminal vesicles and one for the external urethral sphincter.

The prostate is divided into right/left on axial sections by a vertical line drawn through the center (indicated by the prostatic urethra), and into anterior/posterior by a horizontal line through the middle of the gland.

The right and left peripheral zones (PZ) at prostate base, midgland, and apex are each subdivided into three sections: anterior (a), medial posterior (mp), and lateral posterior (lp).

The right and left transition zones (TZ) at prostate base, midgland, and apex are each subdivided into two sections: anterior (a) and posterior (p).

The central zone (CZ) is included in the prostate base around the ejaculatory ducts.

The anterior fibromuscular stroma (AS) is divided into right/left at the prostate base, midgland, and apex.

The seminal vesicles (SV) are divided into right/left.

The urethral sphincter (US) is marked in the prostate apex and along the membranous segment of the urethra.

The sector map illustrates an idealized “normal prostate”. In patients and their corresponding MRI images, many prostates have components that are enlarged or atrophied, and the PZ may obscured by an enlarged TZ. In such instances, in addition to the written report, a sector map which clearly indicates the location of the findings will be especially useful for localization.

Appendix III

| Lexicon ABNORMALITY | |

|---|---|

| Focal abnormality | Localized at a focus, central point or locus |

| Focus | Localized finding distinct from neighboring tissues, not a three-dimensional space occupying structure |

| Index Lesion | Lesion identified on MRI with the highest PIRADS Assessment Category. If the highest PIRADS Assessment Category is assigned to two or more lesions, the index lesion should be one that shows EPE or is largest. Also known as dominant lesion |

| Lesion | A localized pathological or traumatic structural change, damage, deformity, or discontinuity of tissue, organ, or body part |

| Mass | A three-dimensional space occupying structure resulting from an accumulation of neoplastic cells, inflammatory cells, or cystic changes |

| Nodule | A small lump, swelling or collection of tissue |

| Non-focal abnormality | Not localized to a single focus |

| Diffuse | Widely spread; not localized or confined; distributed over multiple areas, may or may not extend in contiguity, does not conform to anatomical boundaries |

| Multifocal | Multiple foci distinct from neighboring tissues |

| Regional | Conforming to prostate sector, sextant, zone, or lobe; abnormal signal other than a mass involving a large volume of prostatic tissue |

| SHAPE | |

| Round | The shape of a circle or sphere |

| Oval | The shape of either an oval or an ellipse |

| Lenticular | Having the shape of a double-convex lens, crescentic |

| Lobulated | Composed of lobules with undulating contour |

| Water-drop-shaped Tear-shaped | Having the shape of a tear or drop of water; it differs from an oval because one end is clearly larger than the other |

| Wedge-shaped | Having the shape of a wedge, pie, or V-shaped |

| Linear | In a line or band-like in shape |

| Irregular | Lacking symmetry or evenness |

| MARGINS | |

| Circumscribed | Well defined |

| Non-circumscribed | Ill-defined |

| Indistinct | Blurred |

| Obscured | Not clearly seen or easily distinguished |

| Irregular | Uneven |

| Spiculated | Radiating lines extending from the margin of a mass |

| Encapsulated | Bounded by a distinct, uniform, smooth low-signal line (BPH nodule) |

| Organized chaos | Heterogeneous mass in transition zone with circumscribed margins, encapsulated (BPH nodule) |

| Erased charcoal sign | Blurred margins as if smudged, smeared with a finger; refers to appearance of a homogeneously T2 low-signal lesion in the transition zone of the prostate with indistinct margins (prostate cancer) |

| Hyperintense | Having higher signal intensity (more intense, brighter) on MRI than background prostate tissue or reference tissue/ structure |

| T2 Hyperintensity | Having higher signal intensity (more intense, brighter) on T2-weighted imaging |

| Isointense | Having the same intensity as a reference tissue/structure to which it is compared; intensity at MRI that is identical or nearly identical to that of background prostate |

| Hypointense | Having less intensity (darker) than background prostate tissue or reference tissue/structure |

| Markedly hypointense | Signal intensity lower than expected for normal or abnormal tissue of the reference type, e.g., when involved with calcification or blood or gas |

| T2 hypointensity | Having lower signal intensity (less intense, darker) on T2-weighted imaging |

| MR IMAGING SIGNAL CHARACTERISTICS | |

| Restricted diffusion | Limited, primarily by cell membrane boundaries, random Brownian motion of water molecules within the voxel; having higher signal intensity than peripheral zone or transition zone prostate on DW images acquired or calculated at b values >1400 accompanied by lowered ADC values. Synonymous with “impeded” diffusion |

| Diffusion-weighted hyperintensity | Having higher signal intensity, not attributable to T2 shine-through, than background prostate on DW images |

| Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) | A measure of the degree of motion of water molecules in tissues. It is determined by calculating the signal loss in data obtained with different b-values and is expressed in units of mm2/sec or μm2/sec |

| ADC Map | A display of ADC values for each voxel in an image |

| ADC Hyperintense | Having higher signal intensity (more intense, brighter) than background tissue on ADC map |

| ADC Isointense | Intensity that is identical or nearly identical to that of background tissue on ADC map |

| ADC Hypointense | Having lower intensity (darker) than a reference background tissue on ADC map |

| b-value | A measure of the strength and duration of the diffusion gradients that determines the sensitivity of a DWI sequence to diffusion |

| Dynamic contrast enhanced DCE Wash-in | Early arterial phase of enhancement; a period of time to allow contrast agent to arrive in the tissue |

| DCE Wash-out | Later venous phase, de-enhancement, reduction of signal following enhancement; a period of time to allow contrast agent to clear the tissue |

| Pharmacodynamic analysis PD curves | Method of quantifying tissue contrast media concentration changes to calculate time constants for the rate of wash-in and wash-out |

| Time vs. signal intensity curve Enhancement kinetic curve | Graph plotting tissue intensity change (y axis) over time (x axis); enhancement kinetic curve is a graphical representation of tissue enhancement where signal intensity of tissue is plotted as a function of time |

| ENHANCEMENT PATTERNS | |

| Early phase wash-in | Signal intensity characteristic early after contrast agent administration; wash-in phase corresponding to contrast arrival in the prostate |

| Delayed phase | Signal intensity characteristic following its initial (early) rise after contrast material administration |

| Persistent delayed phase Type 1 curve | Continued increase of signal intensity over time |

| Plateau delayed phase Type 2 curve | Signal intensity does not change over time after its initial rise, flat; plateau refers to signal that varies <10% from the peak signal over the duration of the DCE MRI |

| Washout delayed phase Type 3 curve | Signal intensity decreases after its highest point after its initial rise |

| Positive DCE | Focal, early enhancement corresponding to a focal peripheral zone or transition zone lesion on T2 and/or DWI MRI |

| Negative DCE | Lack of early enhancement Diffuse enhancement not corresponding to a focal lesion on T2 and/or DWI MRI Focal enhancement corresponding to a BPH lesion |

| ANATOMICAL TERMS | |

| Prostate: Regional Parts | The prostate is divided from superior to inferior into three regional parts: the base, the midgland, and the apex. |

| Base of prostate | The upper 1/3 of the prostate just below the urinary bladder. |

| Mid prostate | The top 1/3 of the prostate that includes verumontanum in the mid prostatic urethra; midgland |

| Apex of prostate | The lower 1/3 of the prostate |

| Peripheral zone | Covers the outer posterior, lateral, and apex regions of the prostate; makes up most of the apex of the prostate |

| Transition zone | Tissue around the urethra that is separated from the peripheral zone by the “surgical capsule” delineated as a low signal line on T2 weighted MRI; it is the site of most BPH |

| Central zone | Tissue surrounding the ejaculatory ducts posterior and superior, from the base of the prostate to the verumontanum; it has the shape of an inverted cone with its base oriented towards the base of the gland; contains more stroma than glandular tissue |

| Anterior fibromuscular stroma | Located anteriorly and contains smooth muscle, which mixes with periurethral muscle fibers at the bladder neck; contains no glandular tissue |

| Prostate: Sectors | Anatomical regions defined for the purpose of prostate targeting during interventions, may include multiple constitutional and regional parts of the prostate. Thirty-six sectors for standardized MRI prostate localization reporting are identified, with addition of seminal vesicles and membranous urethra. Each traditional prostate sextant is sub-divided into six sectors, to include: the anterior fibromuscular stroma, the transition zone anterior and posterior sectors, the peripheral zone anterior, lateral, and medial sectors. The anterior and posterior sectors are defined by a line bisecting the prostate into the anterior and posterior halves. See Diagram for reference |

| Prostate “_capsule_” | Histologically, there is no distinct capsule that surrounds the prostate, however historically the “_capsule_” has been defined as an outer band of the prostatic fibromuscular stroma blending with endopelvic fascia that may be visible on imaging as a distinct thin layer of tissue surrounding or partially surrounding the peripheral zone. |

| Prostate pseudocapsule | Imaging appearance of a thin “capsule” around transition zone when no true capsule is present at histological evaluation. The junction of the transition and peripheral zones marked by a visible hypointense linear boundary, which is often referred to as the prostate “pseudocapsule” or “surgical capsule.” |

| Seminal vesicle | One of the two paired glands in the male genitourinary system, posterior to the bladder and superior to the prostate gland, that produces fructose-rich seminal fluid which is a component of semen. These glands join the ipsilateral ductus (vas) deferens to form the ejaculatory duct at the base of the prostate. |

| Neurovascular bundle of prostate NVB | Nerve fibers from the lumbar sympathetic chain extend inferiorly to the pelvis along the iliac arteries and intermix with parasympathetic nerve fibers branching off S2 to S4. The mixed nerve bundles run posterior to the bladder, seminal vesicles, and prostate as the “pelvic plexus”. The cavernous nerve arises from the pelvic plexus and runs along the posterolateral aspect of the prostate on each side. Arterial and venous vessels accompany the cavernous nerve, and together these structures form the neurovascular bundles which are best visualized on MR imaging at 5 and 7 o’clock position. At the apex and the base of the prostate, the bundles send penetrating branches through the “capsule”, providing a potential route for extraprostatic tumor spread. |

| Right neurovascular bundle | Located at 7 o’clock posterolateral position. |

| Left neurovascular bundle | Located at 5 o’clock posterolateral position. |

| Vas deferens | The excretory duct of the testes that carries spermatozoa; it rises from the scrotum and joins the seminal vesicles to form the ejaculatory duct, which opens into the mid prostatic urethra at the level of the verumontanum. |

| Verumontanum | The verumontanum (urethral crest formed by an elevation of the mucous membrane and its subjacent tissue) is an elongated ridge on the posterior wall of the mid prostatic urethra at the site of ejaculatory ducts opening into the prostatic urethra. |

| Neck of urinary bladder | The inferior portion of the urinary bladder which is formed as the walls of the bladder converge and become contiguous with the proximal urethra |

| Urethra: Prostatic | The proximal prostatic urethra extends from the bladder neck at the base of the prostate to verumontanum in the mid prostate. The distal prostatic urethra extends from the verumontanum to the membranous urethra and contains striated muscle of the urethral sphincter. |

| Urethra: Membranous | The membranous segment of the urethra is located between the apex of the prostate and the bulb of the corpus spongiosum, extending through the urogenital diaphragm. |

| External urethral sphincter | Surrounds the whole length of the membranous portion of the urethra and is enclosed in the fascia of the urogenital diaphragm. |

| Periprostatic compartment | Space surrounding the prostate |

| Rectoprostatic compartment Rectoprostatic angle | Space between the prostate and the rectum |

| Extraprostatic | Pertaining to an area outside the prostate |

| Prostate-seminal vesicle angle | The plane or space between the prostate base and the seminal vesicle, normally filled with fatty tissue and neurovascular bundle of prostate. |

| STAGING TERMS | |

| Abuts “capsule” of prostate | Tumor touches the “capsule” |

| Bulges “capsule” of prostate | Convex contour of the “capsule” Bulging prostatic contour over a suspicious lesion: Focal, spiculated (extraprostatic tumor) Broad-base of contact (at least 25% of tumor contact with the capsule) Tumor-capsule abutment of greater than 1 cm Lenticular tumor at prostate apex extending along the urethra below the apex. |

| Mass effect on surrounding tissue | Compression of the tissue around the mass, or displacement of adjacent tissues or structures, or obliteration of the tissue planes by an infiltrating mass |

| Invasion | Tumor extension across anatomical boundary; may relate to tumor extension within the gland, i.e. across regional parts of the prostate, or outside the gland, across the “capsule” (extracapsular extension of tumor, extraprostatic extension of tumor, extraglandular extension of tumor). |

| Invasion: “Capsule” Extra-capsular extension ECE | Tumor involvement of the “capsule” or extension across the “capsule” with indistinct, blurred or irregular margin |

| Extraprostatic extension EPE | Retraction of the capsule |

| Extraglandular extension | Breach of the capsule Direct tumor extension through the “capsule” Obliteration of the rectoprostatic angle |

| Invasion: Pseudocapsule | Tumor involvement of pseudocapsule with indistinct margin |

| Invasion: Anterior fibromuscular stroma | Tumor involvement of anterior fibromuscular stroma with indistinct margin |

| Invasion: Prostate -seminal vesicle angle | Tumor extends into the space between the prostate base and the seminal vesicle |

| Invasion: Seminal vesicle Seminal vesicle invasion SVI | Tumor extension into seminal vesicle There are 3 types: 1. Tumor extension along the ejaculatory ducts into the seminal vesicle above the base of the prostate; focal T2 hypointense signal within and/or along the seminal vesicle; enlargement and T2 hypointensity within the lumen of seminal vesicle Restricted diffusion within the lumen of seminal vesicle Enhancement along or within the lumen of seminal vesicle Obliteration of the prostate- seminal vesicle angle 2. Direct extra-glandular tumor extension from the base of the prostate into and around the seminal vesicle 3. Metachronous tumor deposit -separate focal T2 hypointense signal, enhancing mass in distal seminal vesicle |

| Invasion: Neck of urinary bladder | Tumor extension along the prostatic urethra to involve the bladder neck |

| Invasion: Membranous urethra | Tumor extension along the prostatic urethra to involve the membranous urethra |

| Invasion: Periprostatic, extraprostatic | Tumor extension outside the prostate |

| Invasion: Neurovascular bundle of prostate | Tumor extension into the neurovascular bundle of the prostate Asymmetry, enlargement or direct tumor involvement of the neurovascular bundles Assess the recto-prostatic angles (right and left): 1. Asymmetry - abnormal one is either obliterated or flattened. 2. Fat in the angle - infiltrated (individual elements cannot be identified or separated) clean (individual elements are visible) 3. Direct tumor extension |

| Invasion: External urethral sphincter | Tumor extension into the external urethral sphincter Loss of the normal low signal of the sphincter, discontinuity of the circular contour of the sphincter |

| MRI CHARACTERISTICS OF ADDITIONAL PATHOLOGIC STATES | |

| BPH nodule | A round/oval mass with a well-defined T2 hypointense margin; encapsulated mass or “organized chaos” found in the transition zone or extruded from the transition zone into the peripheral zone |

| Hypertrophy of median lobe of prostate | Increase in the volume of the median lobe of the prostate with mass-effect or protrusion into the bladder and stretching the urethra |

| Cyst | A circumscribed T2 hyperintense fluid containing sac-like structure |

| Hematoma-Hemorrhage | T1 hyperintense collection or focus |

| Calcification | Focus of markedly hypointense signal on all MRI sequences |

| MRI CHARACTERISTICS OF ADDITIONAL PATHOLOGIC STATES | |

| BPH nodule | A round/oval mass with a well-defined T2 hypointense margin; encapsulated mass or “organized chaos” found in the transition zone or extruded from the transition zone into the peripheral zone |