Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms of RecQ1, RAD54L and ATM Genes Are Associated With Reduced Survival of Pancreatic Cancer (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2006 Apr 11.

Published in final edited form as: J Clin Oncol. 2006 Mar 6;24(11):1720–1728. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4206

Abstract

PURPOSE

Our goal was to determine whether single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), in DNA repair genes influence the clinical outcome of pancreatic cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We evaluated 13 SNPs of eight DNA damage response and repair genes in 92 patients with potentially resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. All patients were treated with neoadjuvant concurrent gemcitabine and radiotherapy with or without a component of induction gemcitabine/cisplatin at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center during February 1999 to August 2004 and followed up to August 2005. Response to the pretreatment was assessed by evaluating time to tumor progression and overall survival. Kaplan-Meier plot, log-rank test and Cox regression were used to compare survival of patients according to genotype.

RESULTS

The RecQ1 A159C_, RAD54L_ C157T_, XRCC1_ R194W, and ATM T–77C genotypes had a significant effect on the overall survival with a log rank P values of 0.001, 0.004, 0.001 and 0.02, respectively. A strong combined effect of the four genotypes was observed. Patients with none of the adverse genotypes had a mean survival time of 62.1 months, and those with 1, 2, or ≥3 at-risk alleles had median survival times of 27.5, 14.4, and 9.9 months, respectively (_P<_0.001, log rank test). There is a significant interaction between the RecQ1 gene and other genotypes. All four genes except XRCC1 remained as independent predictors of survival in multivariate Cox regression models adjusted for other clinical predictors.

CONCLUSION

These observations support the hypothesis that polymorphic variants of DNA repair genes affects clinical prognosis of patient with pancreatic cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer is a rapidly fatal disease with a 5-year survival <5% (1). Surgical resection offers the only potentially curative treatment. The 5-year survival rate for patients after tumor resection is 10% for node-positive and 30% for node-negative resections. Other known prognostic factors for surgical patients include tumor size, tumor grade, and tumor stage (2). The poor prognosis of pancreatic cancer is due to both its metastasis-prone and therapy-resistant nature, which is partially explained by the frequent genetic and epigenetic alterations described in this tumor (3). On the other hand, host variations in DNA repair or drug metabolism, may also influence clinical response to therapy and overall survival of the patients (4). Prognostic markers are needed to stratify patients on protocols and for use in clinical practice. Predictive markers identifying response to cytotoxic therapy would further potentially provide a means of individualizing treatment and could lead to a better understanding of resistance mechanisms of both standard and novel treatment strategies

Gemcitabine is a standard of care in pancreatic cancer, offering a slightly better overall survival than 5-fluorouracil for patients with locally advanced and metastatic tumors (5). Little is known about DNA repair pathways that may alter cytotoxicity or radiosensitivity of gemcitabine. Previous studies have shown that gemcitabine induced radiosensitization and cytotoxic effect of mitomycin C were absent in homologous recombination repair (HRR)-deficient cells, suggesting that HRR may play an important role in gemcitabine-mediated cell killing (6,7). HRR is also involved in the repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), which are the most common type of radiation lesions that lead to mammalian cell death (8,9).

Previous clinical studies have shown that individual variation in DNA repair capacity conferred by single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) affects the clinical response to platinum-based cancer therapy and overall survival of patients (10-13). Because gemcitabine and radiation-induced DNA damage is most likely repaired through the BER and HRR pathways, we hypothesized that genetic variations in these pathways may affect sensitivity to gemcitabine and radiotherapy, thus overall prognosis. We tested this hypothesis in a relatively homogeneous population, i.e. 92 patients with potentially resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma who had undergone neoadjuvant gemcitabine-based chemoradiation. We evaluated eight DNA repair genes, i.e. RecQ1, RAD54L, ATM, XRCC1, XRCC2, XRCC3, LIG3, and LIG4. We selected 13 SNPs of the eight genes on the basis of their known allele frequencies, functional significance or previous reports of association with cancer risk or clinical outcome.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Recruitment and Data Collection

The study involves 92 patients who, at the time of diagnosis, had potentially resectable adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas and had not received any treatment for pancreatic cancer. All patients were enrolled in one of two phase II clinical trials (ID98-020 and ID01-341) of pre-operative (neo-adjuvant) chemoradiotherapy at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (M.D. Anderson) conducted sequentially from February 1999 to August 2004 and were followed up to August 31, 2005. These 92 patients represent the subset of patients enrolled in these clinical trials who consented for blood donation. Patients in the ID98-020 trial (n=43) had received gemcitabine-based chemoradiotherapy consisting of weekly gemcitabine (400 mg/m2) for 4 weeks and radiation (30 Gy in 10 fractions) for 2 weeks. Patients in the ID01-341 trial (n=49) had received induction therapy of gemcitabine (750 mg/m2/day) and Cisplatin (30 mg/m2/day) every 2 weeks for 4 weeks followed by chemoradiotherapy with weekly gemcitabine (400 mg/m2) for 4 weeks and radiation (30 Gy in 10 fractions) for 2 weeks. Clinical information was collected from the medical records with the patients’ consent. Clinical stage was defined based on the initial computed tomography imaging and defined as stated in the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual using the TNM staging system (14). Pathologic stage was determined after surgery, in those patients who underwent a successful resection of their primary tumor, and also used the TNM staging system (14). Tumor progression was defined as local tumor progression, tumor recurrence, metastasis and death due to the disease. Patients without tumor progression at the end of the follow-up were censored. The pre-operative treatment effect was evaluated histologically in resected tumors according to previously published criteria (15), i.e. tumors with >90% viable carcinoma cells were defined as treatment effect grade I, 51-90% as grade IIA, 10-50% as grade IIB, and <10% as grade III. Post-surgical treatment or treatment received after tumor recurrence were not considered in this study.

DNA Extraction and Genotyping

Whole blood was collected from patients at the time of enrollment and DNA was extracted from peripheral lymphocytes using a DNA Isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Polymorphisms were detected using the Masscode technique (BioServe, Laurel, MD). About 10% of the samples were analyzed in duplicate, and discrepancies were seen in less than 0.1% of the samples. Those with discordant results from two analyses were excluded from the final data analysis. The genes, chromosome locations, nucleotide substitutions, amino acid changes, reference SNP identification numbers and reported allele frequencies of the 13 SNPs evaluated in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

SNPs evaluated in this study

| Gene | Chromosome | SNP | Nucleotide change | RS#a | Allele Frequencyb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RECQL | 12p12 | 3'UTR EX15+159 | A to C | 13035 | 0.28 |

| IVs3-86 | A to G | 4987216 | 0.02 | ||

| RAD54L | 1p32 | A730A ex18+157 | C to T | 1048771 | 0.12 |

| ATM | 11q22-q23 | IVS22-77 | T to C | 664677 | 0.29 |

| D1853N, Ex38+61 | A to G | 1801516 | 0.92 | ||

| D126E, Ex6+47 | A to T | 2234997 | 0.94 | ||

| XRCC1 | 19q13.2 | R194W | C to T | 1799782 | 0.13 |

| Q399R | A to G | 25487 | 0.66 | ||

| XRCC2 | 7q36.1 | R188H | G to A | 3218536 | 0.05 |

| XRCC3 | 14q32.3 | T241Met | C to T | 861539 | 0.22 |

| IVs7-14 | A to G | 1799796 | 0.29 | ||

| LIG3 | 17q11.2-q12 | IVs18-39 | G to A | 2074522 | 0.10 |

| LIG4 | 13q33-q34 | 5'UTR Ex2+54, T9I | C to T | 1805388 | 0.13 |

Survival Measurements

Dates of death were obtained and crosschecked using at least one of the following sources: the Social Security Death Index, inpatient medical records, or the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center tumor registry. Time to progression and overall survival time was calculated from the date the patient had enrolled in the trial to the date tumor progression was first recorded, or the date of death or last follow-up, respectively. When patients with tumor resection were analyzed as a separate group, overall survival time was calculated from the date of tumor resection to date of death or last follow up.

Statistical Methods

The distribution of genotypes was tested for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium with the goodness-of-fit χ2 test. The association between overall survival time and time to disease progression with genotypes was estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier and assessed using the log-rank test. Median follow-up time was computed with censored observations only. Median survival time (MST) was calculated, and mean survival time was presented when MST could not be calculated. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using univariate or multivariate Cox proportional hazard models. Known or potential clinical prognostic factors such as tumor size, tumor grade, tumor stage, the effects of preoperative treatment on tumors, as well as serum CA19-9 values at diagnosis were included in the multivariate model when appropriate. Gene-gene interactions were determined by generating a cross-product term and tested by using the likelihood ratio test. All statistical testing was conducted with SPSS software, version 12.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL), and statistical significance was defined as P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Survival Analysis

The median age of the 92 patients was 65 years (range, 38 to 83 years). The patient characteristics and clinical features of the tumor are summarized in Table 2. The median (range) time interval from the initial pathological diagnosis to enrollment in the trial was 16 (1 to 91) days. Of the 92 cases, 62 had their primary tumor surgically resected after pre-operative treatment; the remaining 30 patients were not resected due to disease progression found at restaging after preoperative therapy (23 patients) or at the time of operation (7 patients). All 62 patients who underwent pancreatic resection had a grossly complete resection, however, pathologic evaluation of the surgical specimens demonstrated a microscopically positive margin (R1 resection) in 7 (11.3%) of the 62 patients.

Table 2.

Patients’ characteristics and clinical features

| Characteristics | No. of cases | (%) | No. of deaths | MST (months) | P (LR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤50 | 12 | (13) | 6 | 20.3 | |

| 51–60 | 23 | (25) | 16 | 16.1 | |

| 61–70 | 29 | (32) | 17 | 18.9 | |

| >70 | 28 | (30) | 18 | 22.7 | 0.85 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 52 | (56) | 33 | 16.5 | |

| Female | 40 | (44) | 24 | 22.7 | 0.38 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 83 | (90) | 52 | 20.3 | |

| Hispanics | 5 | (5) | 3 | 18.2 | |

| Black | 3 | (3) | 1 | ||

| Other | 1 | (1) | 1 | 10.7 | 0.43 |

| Diabetes | |||||

| No | 69 | (75) | 40 | 22.5 | |

| Yes | 23 | (25) | 17 | 16.9 | 0.20 |

| Smoking | |||||

| Never | 27 | (29) | 15 | 24.5 | |

| Ever | 65 | (71) | 42 | 18.4 | 0.46 |

| CA19-9 level (units/ml) | |||||

| ≤47 | 22 | (24) | 12 | 24.5 | |

| 48–500 | 44 | (48) | 23 | 21.7 | |

| 501–1000 | 10 | (11) | 8 | 23.9 | |

| >1000 | 16 | (17) | 14 | 15.3 | 0.05 |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||||

| ≤1 | 24 | (26) | 11 | 44.8a | |

| 1.1–2.5 | 38 | (41) | 28 | 16.1 | |

| >2.5 | 32 | (34) | 18 | 24.3 | 0.06 |

| Tumor resection | |||||

| Yes | 55 | (60) | 31 | 28.7 | |

| No | 37 | (40) | 26 | 10.3 | <0.001 |

| Stage after surgery | |||||

| 0 or I | 8 | (11) | 3 | 49.1a | |

| IIA | 20 | (34) | 7 | 56.3a | |

| IIB (node positive) | 34 | (55) | 20 | 18.9 | 0.006 |

| Clinical protocol | |||||

| GEM/XRT | 44 | (48) | 29 | 22.5 | |

| GEM/Cisplatin/XRT | 48 | (52) | 28 | 16.1 | 0.321 |

| Tumor grade (differentiation) | |||||

| Well | 3 | (4) | 1 | 48.4a | |

| Moderate | 44 | (67) | 22 | 27.8 | |

| Poor | 19 | (29) | 14 | 15.3 | 0.01 |

| Treatment effect (viable cells) | |||||

| GI (>90%) | 4 | (7) | 3 | 18.2 | |

| G2A (50–90%) | 17 | (30) | 9 | 24.5 | |

| G2B (10–49%) | 27 | (47) | 14 | 24.3 | |

| G3 (<10%) | 9 | (16) | 2 | 60.4a | 0.34 |

There were 57 deaths (62.0%) among the 92 cases. The median follow-up time was 33 months for the living patients. The MST of the 92 patients was 20.3 months (95% CI: 14.7–25.9). The tumor size (>1 cm), tumor with poor differentiation, serum level of CA19-9 at diagnosis >1000 units/ml, tumor not resected, and node positive resection (Stage IIB) were significantly associated with reduced overall survival (Table 2).

Genotype Frequency and Effects on Overall Survival

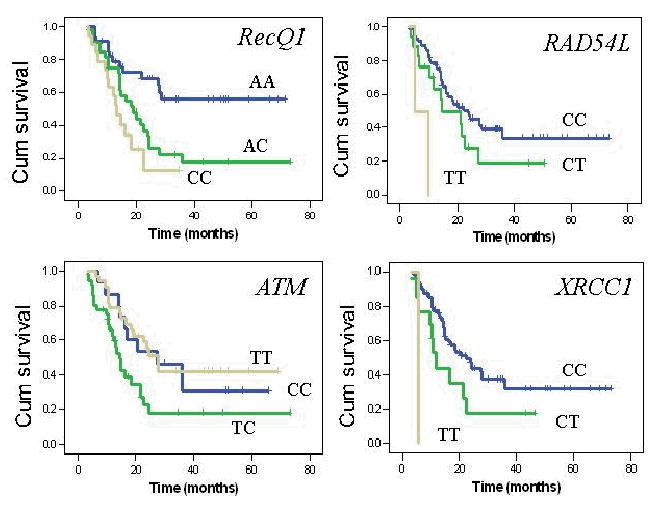

The 13 SNPs were successfully amplified in 91% to 99% of the patients. Genotype frequencies of all 13 SNPs were found to be in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (χ2 = 0.03–1.22, P >0.1) except RecQ1 A159 (χ2 = 4.22, P = 0.04). There was a significant difference in the ethnic distribution of the ATM E126D SNP, with a higher frequency of the variant allele in Hispanics (20%) and blacks (33%) than in whites (1%) (P = 0.02, Fisher exact test). The genotype frequencies and the MST by each genotype are shown in Table 3. Of the 13 SNPs evaluated, four showed a significant effect on overall survival. The strongest genetic effect on survival was observed for the RecQ1 A159C , with MSTs of 18.9 and 13.1 months for the AC and CC genotypes, respectively, compared with a mean survival time of 46.9 months for the AA wild-type (P value of the log-rank test [P(LR)] = 0.004). At the end of the study, about 62% of the AA genotype carriers were still alive, compared with 25% of the AC and 26% of the CC genotype carriers (Fig. 1). The RAD54L C157T, ATM T-77C and XRCC1 R194W genotypes also showed significant effects on survival (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Other SNPs, such as the XRCC2 R188H and ATM D126E genotypes, had a mild effect on survival, but the differences did not reach the level of statistical significance. Neither of the two XRCC3 SNPs nor the LIG3 and LIG4 genotypes had any significant effects on overall survival.

Table 3.

Overall survival by genotype

| Genotype | No. of cases | No. of deaths | MSTa(months) | HR (95% CI)b | P | Genotype | No. of cases | No. of deaths | MST (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RecQ1 159 | ATM-D1853N | ||||||||

| AA | 34 | 13 | 46.9a | Reference | GG | 74 | 45 | 18.4 | |

| AC | 32 | 24 | 18.9 | 2.5 (1.3–5.0) | 0.008 | GA | 16 | 11 | 23.9 |

| CC | 19 | 14 | 13.1 | 3.8 (1.8–8.4) | 0.001 | AA | 1 | 0 | |

| AC/CC | 41 | 38 | 16.1 | 2.8 (1.5–5.4) | 0.001 | ||||

| P(LR)c | 0.001(0.001) | ATM-E126D | |||||||

| TT | 88 | 54 | 21.4 | ||||||

| RAD54L | TA | 3 | 2 | 6.2 | |||||

| CC | 72 | 38 | 23.9 | Reference | |||||

| CT | 17 | 11 | 14.6 | 1.6 (0.8–3.0) | 0.16 | LIG3 | |||

| TT | 1 | 1 | 5.4 | GG | 73 | 45 | 20.3 | ||

| CT/TT | 14.6 | 1.8 (1.0–3.3) | 0.06 | GA | 19 | 8 | 18.9 | ||

| P(LR)c | 0.004 (0.06) | ||||||||

| LIG4 | |||||||||

| ATM C77T | CC | 69 | 43 | 18.9 | |||||

| TT | 33 | 17 | 27.8 | Reference | CT | 20 | 12 | 22.7 | |

| TC | 36 | 25 | 14.4 | 2.2 (1.2–4.2) | 0.01 | TT | 1 | 1 | |

| CC | 15 | 10 | 27.5 | 1.2 (0.7–3.8) | 0.69 | ||||

| TC vs TT/CC | 2.1 (1.2–3.7) | 0.002 | XRCC1-399 | ||||||

| P(LR)c | 0.018 (0.006) | AA | 29 | 16 | 24.5 | ||||

| AC | 48 | 32 | 14.8 | ||||||

| XRCC1-194 | CC | 14 | 9 | 21.4 | |||||

| CC | 72 | 39 | 22.7 | Reference | |||||

| CT | 13 | 9 | 12.0 | 1.8 (0.9–3.7) | 0.08 | XRCC2 R188H | |||

| TT | 1 | 1 | 5.4 | GG | 79 | 48 | 21.4 | ||

| CT/TT | 10.7 | 2.0 (1.0–3.9) | 0.04 | GA | 10 | 7 | 14.6 | ||

| P(LR)c | 0.001 (0.04) | ||||||||

| XRCC3 17893 | |||||||||

| Combined | AA | 43 | 25 | 22.5 | |||||

| 0 | 8 | 1 | 62.1a | Referenced | AG | 38 | 23 | 16.9 | |

| 1 | 32 | 17 | 27.5 | Referenced | GG | 8 | 6 | 18.2 | |

| 2 | 24 | 19 | 14.4 | 3.6(1.8–7.2) | <0.001 | ||||

| 3 | 11 | 9 | 9.9 | 4.5(2.0–10.0) | <0.001 | XRCC3 T241M | |||

| P(LR) | <0.001 | GG | 40 | 25 | 21.7 | ||||

| GA | 37 | 24 | 16.1 | ||||||

| RecQ1 –86 | AA | 14 | 8 | 27.8 | |||||

| GG | 87 | 54 | 21.4 | ||||||

| GA | 2 | 2 | 16.1 |

Figure 1.

Overall survival curves by genotypes. P values of the log rank test were 0.02 and 0.004 for RecQ1 AC or CC versus AA genotype; 0.16 and 0.002 for RAD54L CT or TT versus CC genotype; 0.04 and 0.001 for XRCC1 CT or TT versus CC genotype; and 0.009 and 0.85 for ATM TC or CC versus TT genotype.

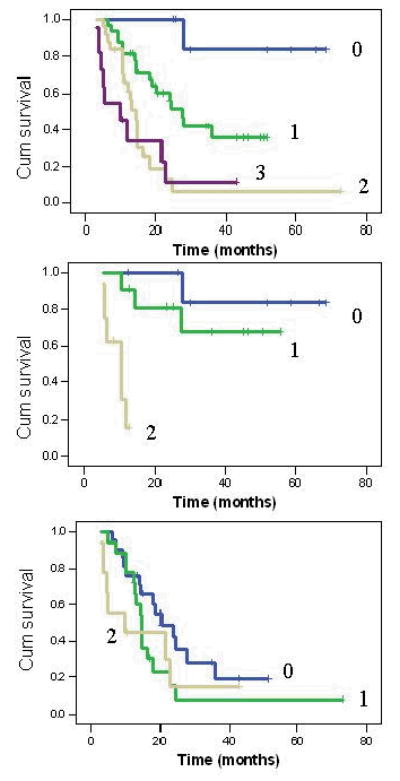

Combined Genotype Effects

A strong gene-dosage effect was observed when the RecQ1 159 AC/CC, RAD54L 157 CT/TT, XRCC1 199W, and _ATM_-77TC genotypes were analyzed in combination. Patients with none of the adverse genotypes had a mean survival time of 62.1 months, whereas those with one, two, or more at-risk alleles had MSTs of 27.5, 14.4, and 9.9 months, respectively (P(LR) < 0.001) (Table 3 and Fig. 2). Further analysis revealed a significant interaction between the RecQ1 A159C genotype and the remaining three SNPs. A strong protective effect of the RecQ1 159AA genotype was observed. In the presence of the AA genotype, the overall survival time was 62.1 (mean), 40.3 (mean), and 10.3 (median) months for those with zero, one, or two adverse genotypes of the RAD54L, ATM, and XRCC1 SNPs, respectively (_P_LR <0.001). Among patients with the RecQ1 159 AC/CC genotypes, however, the MSTs were 20.3, 14.6, and 9.9 months, respectively, if they also had zero, one, or two adverse genotypes of the other three genes (_P_LR = 0.17). The likelihood ratio P value for the statistical interaction between RecQ1 and the number of other adverse genotypes was 0.003.

Figure 2.

Combined effect of RecQ1 159 AC/CC, RAD54L 157 CT/TT, XRCC1 194CT/TT, and ATM-77 TC on overall survival (upper panel). The number of 0–3 indicates number of adverse genotypes. P(LR) = 0.03, 0.007, and 0.001 for patients carrying 1, 2 or 3 adverse genotypes compared with those having none. Combined effect of RAD54L, XRCC1 and ATM genotypes in patients carrying the RecQ1 159 AA genotype (middle panel) or the RecQ1 AC/CC genotypes (lower panel). Note the strong protective effect of RecQ1 AA genotype on survival. The likelihood ratio P value for the statistical interaction between RecQ1 and the number of other adverse genotypes was 0.0035.

Genotype Effects on Two-Year Survival and Time to Tumor Progression

Two-year survival was evaluated among 72 patients and the survival rate was 39%. RecQ1 159 AC/CC and ATM -77 TC genotypes was significantly associated with a reduced two year survival rate, 21% and 15%, respectively (Table 4). The odds ratio (95% CI) of dying was 7.5 (2.5–22.9) and 6.4 (1.9–22.1) for the two adverse genotypes, respectively. Patients with two or more adverse genotypes of the RecQ1, RAD54L, ATM and XRCC1 genes had a 2-year survival rate of 8% only (OR: 20.7, 95% CI: 4.1–105, P <0.001). The RecQ1 A159C and ATM T-77C variant genotypes were also significantly associated with a shorter time to disease progression (Table 4).

Table 4.

Two-year survival and time to progressions by genotype

| Two-year survival | Progression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Dead N (%) | Alive N (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | No. of events | MTPa (months) | P(LR) |

| All cases | 44 (61) | 28 (39) | 68 | 12.1 | |||

| RecQ1-159 | |||||||

| AA | 9 (33) | 18 (67) | 1.0 | 18 | 25.2 | ||

| AC/CC | 30 (69) | 8 (21) | 7.5 (2.5–22.9) | 0.001 | 44 | 10.3 | 0.002 |

| RAD54L | |||||||

| CC | 31 (56) | 24 (44) | 1.0 | 53 | 13.4 | ||

| CT/TT | 11 (63) | 4 (27) | 2.1 (0.6–7.5) | 0.38 | 13 | 10.9 | 0.44 |

| ATM-77 | |||||||

| TT/CC | 18 (46) | 21 (54) | 1.0 | 34 | 14.0 | ||

| TC | 22 (85) | 4 (15) | 6.4 (1.9–22.1) | 0.005 | 28 | 8.7 | 0.03 |

| XRCC1-194 | |||||||

| CC | 31 (57) | 23 (43) | 1.0 | 52 | 11.9 | ||

| CT/TT | 10 (83) | 2 (17) | 3.7 (0.7–18.6) | 0.11 | 11 | 4.3 | 0.06 |

| Combined | |||||||

| 0/1 | 11 (37) | 19 (63) | 1.0 | 26 | 15.6 | ||

| 2/3 | 24 (92) | 2 (8) | 20.7 (4.1–105) <0.001 | 29 | 8.2 | 0.001 |

Cox Regression Models

Finally, we conducted a multivariate analysis of the effects of genotype on survival using Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for other clinical factors. As shown in Table 5, RecQ1 A159C, RAD54L C157T, and ATM T-77C genotypes remained significant independent predictors of survival among all patients regardless of their surgical status. The hazard ratios (95% CI) for the RecQ1 159 AC/CC, RAD54L 157 CT/TT, and _ATM_-77TC genotypes were 2.7 (1.3–5.8), 2.7 (1.3–5.4), and 2.0 (1.0–4.0), respectively, after adjusting for tumor size and CA19-9 level. Tumor grade was not included in this model or in the model for patients with non-resected tumors because information on tumor grade was missing from 28% of the 92 patients. Among patients who had undergone tumor resection, the RecQ1 and RAD54L genotypes remained as significant independent predictors for survival after adjusting for other clinical factors (Table 5).

Table 5.

Hazard ratios and their 95% CIs for overall survival in multivariate Cox regression models

| All Patients (n=75) | Non-resected (n=26) | Resected (n=46)a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | (95% CI) | P | HR | (95% CI) | P | HR | (95% CI) | P |

| RecQ1 (AA vs AC/CC) | 3.0 | (1.4–6.3) | 0.004 | 6.0 | (1.1–39.9) | 0.012 | 14.8 | (1.8–124) | 0.013 |

| RAD54L (CC vs CT/TT) | 2.9 | (1.4–6.0) | 0.004 | 6.8 | (1.5–24.3) | 0.035 | 28.3 | (2.5–318) | 0.007 |

| ATM 77 (TT/CC vs TC) | 1.9 | (1.0–3.8) | 0.054 | 3.6 | (1.2–11.2) | 0.025 | 3.7 | (1.1–12.6) | 0.037 |

| XRCC1 (CC vs CT/TT) | 1.8 | (0.8–4.0) | 0.136 | 1.1 | (0.4–3.4) | 0.876 | 3.1 | (0.7–14.3) | 0.146 |

| Tumor Size (≤1 vs. >1) | 1.2 | (0.6–2.2) | 0.585 | 0.4 | (0.1–1.3) | 0.127 | 0.7 | (0.2–1.7) | 0.386 |

| CA19-9 level (<1000 vs. ≥1000) | 2.3 | (1.0–5.0) | 0.040 | 2.8 | (0.9–8.6) | 0.072 | 3.0 | (0.5–8.9) | 0.339 |

| Clinical protocol (1 vs. 2) | 1.6 | (0.9–3.1) | 0.132 | 1.4 | (0.4–3.4) | 0.876 | 0.8 | (0.3–2.3) | 0.667 |

| Stage after surgery (I/IIA vs. IIB) | NA | NA | 10.4 | (2.5–42.5) | 0.001 | ||||

| Treatment Effect (G1/G2A vs. G2B/G3) | NA | NA | 0.2 | (0.1–0.6) | 0.004 | ||||

| Differentiation (well/moderate vs. poor) | NA | NA | 0.4 | (0.04–6.3) | 0.520 |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the effect of 13 SNPs of eight DNA repair genes on the overall survival of patients with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma who had received preoperative gemcitabine-based chemoradiotherapy. We demonstrated that the RecQ1 A159C variant genotype, both alone and in combination with other genes, was associated with significantly decreased overall survival in this patient population. The RecQ1 159 AA genotype displayed a strong protective effect and a significant interaction with other genotypes. Three SNPs of the RAD54L, ATM, and XRCC1 genes were also found to significantly affect overall survival.

The RecQ1 gene belongs to the DNA helicase family, which includes four additional members—WRN, BLM, RecQ4, and RecQ5 (16). RecQ helicases are important tumor suppressors that are not only involved in DNA HRR but also in S phase checkpoint and telomere maintenance (17,18). Of the five human RecQ helicases identified, three are associated with genetic disorders characterized by an elevated incidence of cancer or premature aging: Werner, Bloom, and Rothmund-Thomson syndrome (19). Although the biological significance of the WRN and BLM helicases has been extensively investigated, less information is available concerning the functions of the other human RecQ helicases. RecQ1 is known to be able to unwind a diverse set of DNA substrates (20, 21), to catalyze efficient strand annealing between complementary single-stranded DNA molecules and to interact with several important factors required for DNA mismatch repair (22). It is possible that a deficient RecQ1 gene may confer an aggressive tumor phenotype through rapid accumulation of genetic alterations and genomic instability. On the other hand, a deficient RecQ1 function may confer a higher cellular sensitivity to genotoxic stress, thus a better clinical response to cytotoxic therapy. It is tempting to speculate that RecQ1 may play a role in resolving gemcitabine-induced DNA replication arrest. Because the functional significance of the RecQ1 SNPs investigated in the current study is currently unknown, the biologic interpretation of the data is difficult. The RecQ1 A159C SNP is located on the 3′-untranslated region of the gene and exerted its effect in a dominant-inheritance mode, i.e., one variant allele is required to alter the chance of survival. It is possible that this SNP may affect translation efficiency and mRNA stability, or it may be in linkage disequilibrium with other SNPs of the same gene or other important genes located in the same chromosome region. Further investigations to confirm our observations in other patient populations as well as on the biological functions of this SNP and this gene are warranted. .

RAD54L belongs to the DEAD-like helicase superfamily (19), and it plays a role in the HRR of DNA DSBs. RAD54L has been proposed as a candidate tumor suppressor gene in tumors with a nonrandom deletion of chromosome 1p32 (23–25). The RAD54L C157T SNP has previously been associated with increased risk of meningioma (25). The variant allele of this SNP was associated with a significantly reduced overall survival in the current study, which could be related to a better repair of DNA DSBs and thus poorer clinical response to therapy. However, functionally, the C157T SNP is a silent polymorphism (Ala730Ala) that does not induce any amino acid change. We can only speculate that the observed effect on survival was related to linkage disequilibrium of this SNP with other SNPs of the same gene or with other genes on the same chromosome. A haplotype analysis will help to explain this observation.

The ATM gene encodes a protein kinase that plays a key role in the detection and repair of DNA DSBs and in maintaining genome integrity (26,27). A previous study has shown that polymorphic variants of the ATM gene are associated with increased in vitro chromosomal radiosensitivity (28). Another study showed that the ATM -77 TC heterozygote was associated with a reduced radiosensitivity among patients with breast cancer compared with the TT homozygote (29). Interestingly, we observed significantly reduced survival time among TC heterozygote carriers relative to that among TT and CC homozygote carriers, which is consistent with a poor response to radiotherapy for the TC heterozygote. Because the T-77C SNP is located in an intron region, it is conceivable that its functional difference may be mediated by affecting RNA splicing. However, to date, no functional studies have been reported linking altered protein function or cellular phenotype with the presence of this SNP. Further analysis of the ATM haplotypes is underway.

The XRCC1 protein plays an important role in BER (30, 31). The XRCC1 194W allele has been previously associated with a reduced risk of cancer but has not been evaluated as a predictor of clinical outcome (32). In the current study, we observed an association between the 194W allele and a shorter overall survival time, even though this effect disappeared after other clinical and genetic factors had been adjusted for (Table 5). The Q399R genotype has been shown to affect clinical response to platinum-based cancer therapy (13), but we did not observe any significant effect of this SNP on clinical outcome in the current study. The weak effect or lack of effect of the XRCC1 gene SNPs observed in the current study are consistent with those of a previous report that the BER pathway does not significantly affect the repair of gemcitabine-induced DNA damage and cell killing (6).

XRCC2 and XRCC3 are RAD51 paralogs that play mediating roles in homologous recombination. Ligase IV and ligase III are components of the NHEJ machinery required for DNA replication and repair (33, 34). None of the SNPs of these genes had any significant effect on patient survival or other clinical parameters in the current study, suggesting a minor role of these genes in clinical response to gemcitabine-based chemoradiation in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer.

This study is limited by its small size and some of the observations maybe made by chance alone. However, the remarkable effect these genotypes have on the overall survival of this relatively homogeneous patient population and the gene dosage effects observed in this study warranty further confirmation in a larger study. If confirmed, such information may provide opportunities for discovery of novel therapeutic targets and genetic profiles that can direct the choice of therapy and predict the treatment tolerance, response, and overall outcome.

Footnotes

This work has been partially presented at the 13th SPORE Investigators Workshop on July 9-12 in Washington, DC.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) RO1 grant CA098380 (to D.L.), SPORE P20 grant CA101936 (to J.L.A.), NIH Cancer Center Core grant CA16672, and a research grant from the Lockton Research Funds (to D.L.).

References

- 1.Greenlee RT, Murray T, Bolden S, et al. Cancer statistics 2000. CA Cancer J Clin. 2000;50:7–33. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.50.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cleary SP, Gryfe R, Guindi M, et al. Prognostic factors in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: analysis of actual 5-year survivors. J Am Col Surg. 2004;198(5):722–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardeesy N, DePinho RA. Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(12):897–909. doi: 10.1038/nrc949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips KA, Van Bebber SL. Measuring the value of pharmacogenomics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4(6):500–9. doi: 10.1038/nrd1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burris HA, 3rd, Moore MJ, Andersen J, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(6):2403–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crul M, van Waardenburg RC, Bocxe S, et al. DNA repair mechanisms involved in gemcitabine cytotoxicity and in the interaction between gemcitabine and cisplatin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65(2):275–82. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01508-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wachters FM, van Putten JW, Maring JG, et al. Selective targeting of homologous DNA recombination repair by gemcitabine. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57(2):553–62. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shenouda G. Strand-break repair and radiation resistance. In: DNA Repair in Cancer Therapy. Totowa, Humana Press, 2004, pp 257–272

- 9.Peterson CL, Cote J. Cellular machineries for chromosomal DNA repair. Genes Dev. 2004;18(6):602–16. doi: 10.1101/gad.1182704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosken CH, Wei Q, Amos CI, et al. An analysis of DNA repair as a determinant of survival in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(14):1091–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.14.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camps C, Sarries C, Roig B, et al. Assessment of nucleotide excision repair XPD polymorphisms in the peripheral blood of gemcitabine/cisplatin-treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Clin Lung Cancer. 2003;4(4):237–41. doi: 10.3816/clc.2003.n.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park DJ, Stoehlmacher J, Zhang W, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum group D gene polymorphism predicts clinical outcome to platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61(24):8654–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurubhagavatula S, Liu G, Park S, et al. XPD and XRCC1 genetic polymorphisms are prognostic factors in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with platinum chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(13):2594–601. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene FL PD, Fleming ID, Fritz AG, et al: Exocrine Pancreas. In: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, Springer, 2002, pp 157–164

- 15.Evans DB, Rich TA, Byrd DR, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation and pancreaticoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Arch Surg. 1992;127(11):1335–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420110083017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaneko H, Fukao T, Kondo N. The function of RecQ helicase gene family (especially BLM) in DNA recombination and joining. Adv Biophys. 2004;38:45–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khakhar RR, Cobb JA, Bjergbaek L, et al. RecQ helicases: multiple roles in genome maintenance. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13(9):493–501. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hickson ID. RecQ helicases: caretakers of the genome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(3):169–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohaghegh P, Hickson ID. DNA helicase deficiencies associated with cancer predisposition and premature ageing disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(7):741–6. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui S, Arosio D, Doherty KM, et al. Analysis of the unwinding activity of the dimeric RECQ1 helicase in the presence of human replication protein A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(7):2158–70. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma S, Sommers JA, Choudhary S, et al. Biochemical Analysis of the DNA Unwinding and Strand Annealing Activities Catalyzed by Human RECQ1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(30):28072–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doherty KM, Sharma S, Uzdilla LA, et al. RECQ1 Helicase Interacts with Human Mismatch Repair Factors That Regulate Genetic Recombination. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(30):28085–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasio D, Murakumo Y, Robbins D, et al. Characterization of the human homologue of RAD54: a gene located on chromosome 1p32 at a region of high loss of heterozygosity in breast tumors. Cancer Res. 1997;57(12):2378–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuda M, Miyagawa K, Takahashi M, et al. Mutations in the RAD54 recombination gene in primary cancers. Oncogene. 1999;18(22):3427–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leone PE, Mendiola M, Alonso J, et al. Implications of a RAD54L polymorphism (2290C/T) in human meningiomas as a risk factor and/or a genetic marker. BMC Cancer. 2003;3(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golding SE, Rosenberg E, Khalil A, et al. Double strand break repair by homologous recombination is regulated by cell cycle-independent signaling via ATM in human glioma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(15):15402–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314191200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiloh Y. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(3):155–68. doi: 10.1038/nrc1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gutierrez-Enriquez S, Fernet M, Dork T, et al. Functional consequences of ATM sequence variants for chromosomal radiosensitivity. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;40(2):109–19. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angele S, Romestaing P, Moullan N, et al. ATM haplotypes and cellular response to DNA damage: association with breast cancer risk and clinical radiosensitivity. Cancer Res. 2003;63(24):8717–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caldecott KW, McKeown CK, Tucker JD, et al. An interaction between the mammalian DNA repair protein XRCC1 and DNA ligase III. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(1):68–76. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cappelli E, Taylor R, Cevasco M, et al. Involvement of XRCC1 and DNA ligase III gene products in DNA base excision repair. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(38):23970–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goode ELUC, Potter JD. Polymorphisms in DNA repair genes and associations with cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;11:1513–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Audebert M, Salles B, Calsou P. Involvement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 and XRCC1/DNA ligase III in an alternative route for DNA double-strand breaks rejoining. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(53):55117–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, Rosidi B, Perrault R, et al. DNA ligase III as a candidate component of backup pathways of nonhomologous end joining. Cancer Res. 2005;65(10):4020–30. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]