p31comet Blocks Mad2 Activation through Structural Mimicry (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2007 Dec 18.

SUMMARY

The status of spindle checkpoint signaling depends on the balance of two opposing dynamic processes that regulate the highly unusual two-state behavior of Mad2. In mitosis, a Mad1-Mad2 core complex recruits cytosolic Mad2 to kinetochores through Mad2 dimerization and converts Mad2 to a conformer amenable to Cdc20 binding, thus facilitating checkpoint activation. p31comet inactivates the checkpoint through binding to Mad1- or Cdc20-bound Mad2, thereby preventing Mad2 activation and promoting the dissociation of the Mad2-Cdc20 complex. Here, we report the crystal structure of the Mad2-p31comet complex. The C-terminal region of Mad2 that undergoes rearrangement in different Mad2 conformers is a major structural determinant for p31comet binding, explaining the specificity of p31comet toward Mad1- or Cdc20-bound Mad2. p31comet adopts a fold strikingly similar to that of Mad2 and binds at the dimerization interface of Mad2. Therefore, p31comet exploits the two-state behavior of Mad2 to block its activation by acting as an “anti-Mad2”.

INTRODUCTION

A cell-cycle surveillance mechanism called the spindle checkpoint monitors the proper bipolar attachment of sister chromatids to spindle microtubules and ensures the fidelity of chromosome segregation during mitosis (Bharadwaj and Yu, 2004; Musacchio and Hardwick, 2002; Musacchio and Salmon, 2007; Yu, 2002). Checkpoint-dependent inhibition of a multisubunit uiquitin ligase, the anaphase-promoting complex or cyclosome (APC/C), requires the direct binding of Mad2 to the mitotic activator of APC/C, Cdc20 (Fang et al., 1998; Hwang et al., 1998; Kim et al., 1998; Yu, 2007). Cytosolic Mad2 has an autoinhibited conformation, called N1-Mad2 or open-Mad2 (hereafter referred to as O-Mad2) that is kinetically unfavorable for Cdc20 binding (De Antoni et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2000; Luo et al., 2004; Yu, 2006). Upon binding to Cdc20, Mad2 undergoes a large structural change to reach the N2- or closed-Mad2 conformation (hereafter referred to as C-Mad2). Mad1—an upstream regulator of Mad2—forms a tight core complex with Mad2. In the Mad1-Mad2 complex, Mad2 also adopts the C-Mad2 conformation (Luo et al., 2002; Sironi et al., 2002). In mitosis, the kinetochore-bound Mad1-Mad2 core complex recruits another copy of cytosolic O-Mad2 through C-Mad2–O-Mad2 dimerization (De Antoni et al., 2005; Shah et al., 2004). All available data support the following two-state model for Mad2 activation. In this model, the Mad1-Mad2 core complex converts O-Mad2 to an intermediate Mad2 conformer (referred to as I-Mad2) that can directly bind to Cdc20 and complete the open-to-closed rearrangement (Figure 1A). Alternatively, I-Mad2 on its own can convert to an unliganded C-Mad2 that dissociates from the Mad1-Mad2 core complex, binds subsequently to Cdc20, and is more active in APC/C inhibition in vitro (Luo et al., 2004; Yu, 2006).

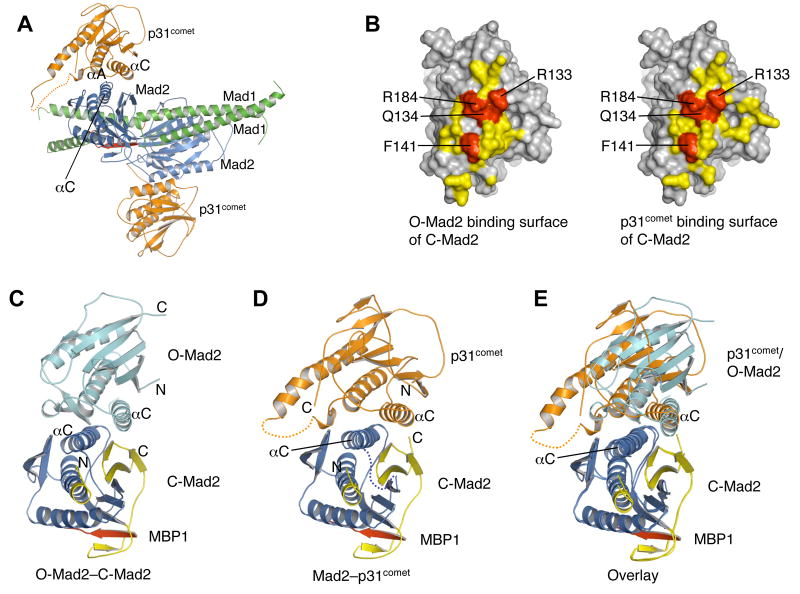

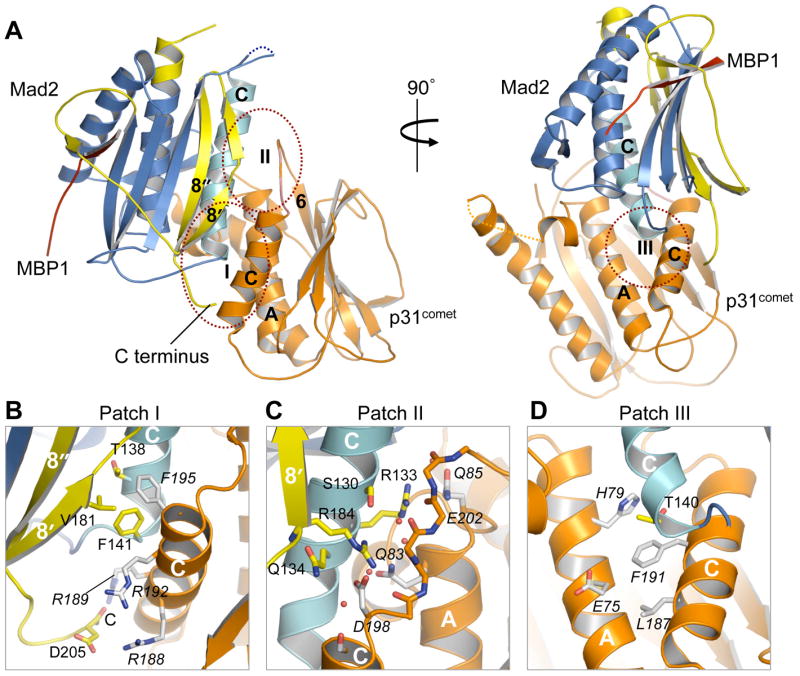

Figure 1. Structure of the Mad2-p31comet Complex.

(A) Schematic drawing of the proposed mechanisms of Mad2 activation by the Mad1-Mad2 core complex and the inhibition of this process by p31comet. Upon checkpoint activation, autoinhibited O-Mad2 binds to the Mad1-Mad2 core complex through Mad2-Mad2 dimerization, which induces a conformational change of O-Mad2 and converts it into an activated intermediate state (I-Mad2). I-Mad2 dissociates from the Mad1-Mad2 core complex to become the active conformer, C-Mad2, with or without Cdc20. During checkpoint inactivation, p31comet binds to the Mad1-Mad2 core complex and blocks the binding of O-Mad2, thus preventing the generation of I-Mad2 and C-Mad2. p31comet also binds to Cdc20-bound Mad2 and activates APC/C. The symbols used for different Mad2 conformers are shown in the shaded yellow box. The Mad2-binding motif of Mad1 is colored red.

(B) Ribbon diagram of the Mad2-p31comet complex in two views. Mad2, p31comet, and MBP1 are colored blue, orange, and red, respectively. The N- and C-termini of Mad2 and p31comet are labeled. All structural figures were generated with PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org).

The p31comet protein binds to both Mad1- and Cdc20-bound C-Mad2, but not to O-Mad2 (Xia et al., 2004) (Figure 1A). Through binding to Mad1-bound C-Mad2, p31comet blocks the recruitment of O-Mad2 to the Mad1-Mad2 core complex and thus prevents Mad1-assisted structural activation of Mad2 (Mapelli et al., 2006). Through binding to Cdc20-bound C-Mad2, p31comet neutralizes the APC/C-inhibitory function of Mad2 and, in collaboration with the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UbcH10, promotes the autoubiquitination of Cdc20 and the disassembly of Mad2-Cdc20-containing checkpoint complexes (Reddy et al., 2007; Stegmeier et al., 2007; Xia et al., 2004). Thus, Mad2 is a two-state protein with an intermediate conformation of finite lifetime; it is positively regulated by Mad1 and inhibited by p31comet (Musacchio and Salmon, 2007; Yu, 2006). By opposing the Mad1-assisted structural activation of Mad2 and promoting the disassembly of the Mad2-Cdc20 complex, p31comet-dependent inhibition of Mad2 sets the threshold for checkpoint activation and enables rapid checkpoint inactivation following the proper attachment of all sister chromatids to the mitotic spindle.

To investigate how p31comet achieves its conformation-specific binding to Mad2 and how it prevents the Mad1-assisted structural activation of Mad2, we have determined the crystal structure of the human Mad2-p31comet complex bound to a high-affinity Mad2-binding peptide (MBP1) (Luo et al., 2002). Our study provides the structural basis for the inhibition of Mad2 activation by p31comet. Our structure reveals that p31comet adopts a fold that is highly similar to Mad2 and binds at the Mad2 dimerization interface. Thus, p31comet blocks the Mad1-assisted Mad2 activation by acting as a structural mimic of Mad2.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structure Determination and Overview of the Mad2-p31comet Complex

The wild-type human Mad2 protein adopts two conformations, O-Mad2 and C-Mad2, which exist in equilibrium (Luo et al., 2004). Perhaps because of this inherent conformational heterogeneity, we were unable to crystallize the wild-type Mad2-p31comet complex. We circumvented this problem by replacing L13 in Mad2 with an alanine. L13 is located in strand β1 of O-Mad2 whereas this region is disordered in C-Mad2. We surmised that the L13A mutation selectively destabilizes the open conformer of Mad2. Indeed, Mad2 L13A exclusively adopted the C-Mad2 conformation and bound to both Cdc20 and p31comet with affinities comparable to those of the wild-type Mad2 (data not shown). In addition, the N-terminal region of p31comet is not conserved in other species (Figure S1) and was dispensable for Mad2 binding (data not shown). The N-terminal about 40 residues of p31comet adopted a flexible conformation based on nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (data not shown). We thus co-expressed Mad2 L13A and a truncation mutant of p31comet lacking its N-terminal 35 residues (p31cometΔN35; residues 36-274) and purified the resulting complex. To further eliminate conformational heterogeneity of Mad2, MBP1 was also added to yield a 1:1:1 Mad2 L13A-MBP1-p31cometΔN35 ternary complex (referred to as Mad2-p31comet for simplicity), for which we were able to produce diffracting crystals. The crystal structure of Mad2-p31comet was then determined by the single anomalous dispersion (SAD) method using diffraction data to a resolution of 2.3Å (Figure 1B and Table 1).

Table 1.

Data Collection, Structure Determination and Refinement

| Data Collection | ||

|---|---|---|

| Crystal | SeMet (peak)a | SeMet (refine)a, b |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 |

| Energy (eV) | 12,662.75 | 12,662.75 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 44.23 – 2.30 (2.34 – 2.30) | 44.23 – 2.30 (2.34 – 2.30) |

| Unique reflections | 44,434 (2,216) | 43,981 (2,192) |

| Multiplicity | 7.2 (7.4) | 4.4 (4.5) |

| Data completeness (%) | 98.2 (100.0) | 97.4 (100.0) |

| _R_merge (%)c | 10.6 (62.1) | 9.4 (53.3) |

| I/σ(I) | 24.5 (4.0) | 19.8 (3.2) |

| Wilson B-value (Å2) | 30.0 | 29.2 |

| Phase Determination | ||

| Anomalous scatterer | selenium (14 of 14 possible sites) | |

| Figure of merit (44.23 – 2.30 Å) | 0.25 (0.75 after density modification) | |

| Refinement Statistics | ||

| Resolution range (Å) | 29.70 – 2.30 (2.36 – 2.30) | |

| No. of reflections _R_work/Rfree | 42,193/1,771 (3,156/129) | |

| Atoms (non-H protein/solvent) | 6,290/665 | |

| _R_work (%) | 18.9 (20.0) | |

| _R_free (%) | 25.8 (30.0) | |

| R.m.s.d. bond length (Å) | 0.017 | |

| R.m.s.d. bond angle (°) | 1.56 | |

| Mean B-value (Å2) | Mad2A: 27.0; p31cometB: 30.6; Mad2C: 26.6; p31cometD: 35.5; MBP1E: 35.5; MBP1F: 33.2; solvent: 35.1 | |

| Ramachandran outliers | p31cometB: Pro250; Mad2C: Leu161 | |

| Missing residues | Mad2A: 1-8; p31cometB: 36-53, 97-123, 273-274; Mad2C: 1-11, 108-118; p31cometD: 36-53, 97-118, 174-180, 274; MBP1E: 12; MBP1F: 11-12 |

There are two structurally nearly identical MBP1-bound Mad2-p31comet heterodimers in an asymmetric unit (Figure 1B and S2). Consistent with the high-affinity interaction between p31comet and Mad2 (Mapelli et al., 2006; Xia et al., 2004), the Mad2-p31comet interface is extensive, with a total buried surface area of 2180 Å2 (Figure 1B). By contrast, the interface between the two Mad2-p31comet heterodimers is formed by the antiparallel pairing of the edge strands of the two Mad2 molecules and only buries a surface area of only 960 Å2 (Figure S2B). The Mad2-p31comet complex has a native molecular mass of 53 kD as determined by equilibrium sedimentation and gel filtration chromatography (Figure S2C), indicating that it exists predominantly as a 1:1 heterodimer in solution with a calculated molecular mass of 51 kD. Therefore, although we cannot rule out the possibility that this type of Mad2-Mad2 interface exists in larger Mad2-Cdc20-containing checkpoint complexes, the Mad2-Mad2 interface observed in our crystals is very likely caused by crystal packing and is unlikely to be functionally relevant.

p31comet Has A Mad2-like Fold

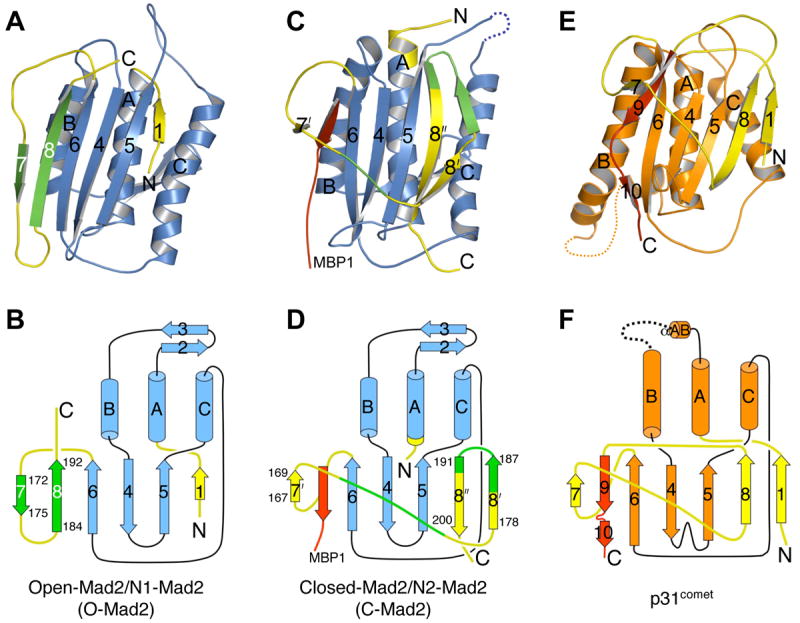

The structure of p31comet contains three central α-helices sandwiched by a seven-stranded β-sheet on one side and a short helix on the other (Figure 1B and 2). The N-terminal region (residues 36-53) and the loop connecting helices αAB and αB (residues 97-118) in p31comet could not be located in the final electron density map and are likely disordered. The overall folding topology of p31comet is strikingly similar to that of ligand-bound C-Mad2 (Figure 2). The backbone root mean square deviation (RMSD) between p31comet and C-Mad2 is 3.0 Å. This structural similarity is unexpected, because p31comet does not share obvious sequence similarity with Mad2 that is detectable by regular sequence alignment algorithms. However, a structure-based sequence alignment reveals that Mad2 and p31comet do in fact share limited sequence similarity, especially between residues located within their regular secondary structural elements (Figure 3A). In particular, R35 and E98 are two invariable residues found in all Mad2 proteins. They form a salt-bridge buried in the interior of the protein and help specify the Mad2 fold (Figure 3B). R84 and E163 in p31comet are the equivalents of R35 and E98 in Mad2. They also form an analogous interior salt-bridge (Figure 3C) and are conserved among most p31comet proteins (Figure S1). Furthermore, R84 of p31comet is located in a conspicuous YQRXXΦP motif (X, any residue; Φ, hydrophobic residue) that is present in both Mad2 and p31comet proteins (Figure 3 and S1). The similarity between Mad2 and p31comet sequences that specify their folds suggests that Mad2 and p31comet have evolved from a common ancestor.

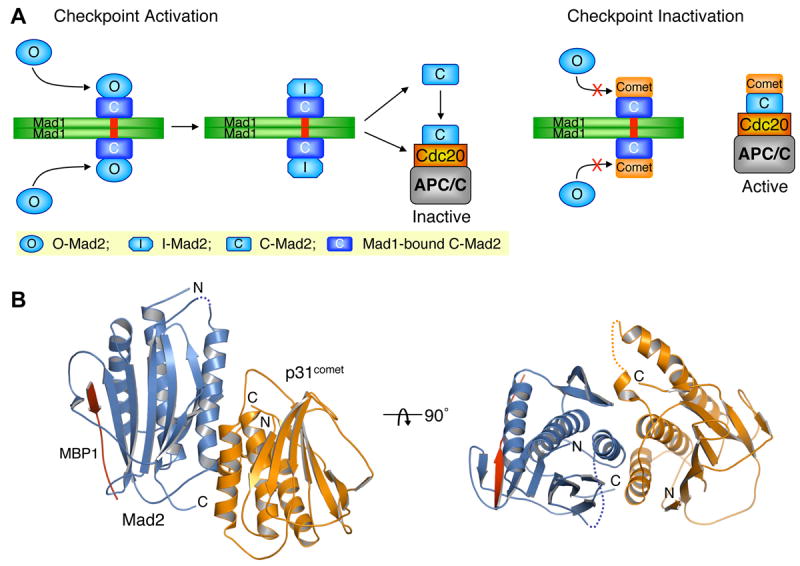

Figure 2. p31comet Has a Fold Similar to Mad2.

Ribbon and topology diagrams of O-Mad2 (PDB ID 1DUJ) (A,B), C-Mad2 (C,D) and p31comet (E,F). The secondary structural elements are labeled and the missing loops in C-Mad2 (residues 108-118) and p31comet (residues 97-118) are shown as dashed lines. The core domain is colored blue for Mad2 and orange for p31comet. The N- and C-terminal regions involved in Mad2 conformational change are colored yellow, except that residues 172-175 and 184-192 are in green. The analogous segment in p31comet is shown in yellow. MBP1 and the C-terminal pseudo-ligand tail of p31comet are shown in red.

Figure 3. Mad2 and p31comet Share Limited Sequence Similarity.

(A) Structure-based sequence alignment of human Mad2 and p31comet. The secondary structural elements of Mad2 are drawn above the sequences and colored blue. The secondary structural elements of p31comet are drawn below the sequences and colored orange. MBP1 is colored red. R35 and E98 in Mad2 are aligned with R84 and E163 in p31comet respectively, and are labeled with asterisks. The YQRXXΦP motif is boxed. In the alignment, Mad2 and p31comet share less than 10% sequence identity.

(B) The buried salt bridge between R35 and E98 in Mad2.

(C) The buried salt bridge between R84 and E163 in p31comet.

Both p31comet and Mad2 contain a similar structural core that consists of three central β strands (β4-6) packed against three long helices (αA-C) (Figure 2). Upon ligand binding, the C-terminal segment of Mad2 undergoes a dramatic conformational change that traps the Mad2-binding peptide between strands β6 and β7’ in a manner that is reminiscent of the way seat belts are used in automobiles (Sironi et al., 2002) (Figure 2C,D). The C-terminal region of p31comet also adopts a similar seat-belt conformation that traps its own C-terminal tail in the pseudo-ligand binding site between strands β6 and β7 (Figure 2E,F). Furthermore, many conserved residues in p31comet are located at this pseudo-ligand binding site and form a contiguous surface (Figure S3). There are also notable differences between the folds of p31comet and C-Mad2. For example, a short β hairpin (β2 and β3) connects αA and αB in Mad2 whereas these helices are linked by a short helix and a disordered loop in p31comet (Figure 2). The C-terminal region of Mad2 forms a β hairpin (β8’ and β8”) with β8” pairing to β5, whereas in p31comet, β9 acts as the pseudo-ligand and β8 interacts with both β1 and β5. These differences help explain why p31comet does not perform similar functions as Mad2, but instead is a Mad2 inhibitor. For example, insertion of its own C-terminal tail into the ligand-binding site prevents p31comet from binding exogenous peptide ligands. The implications of the striking similarity and important differences between the overall folds of Mad2 and p31comet will be further discussed.

Structural Basis for the Binding Specificity of p31comet toward C-Mad2

The binding interface between Mad2 and p31comet consists of αC, β8’, and the C-terminus of Mad2 and αA, αC, and the loop between αC and β6 of p31comet (Figure 4A). At this interface, Mad2 and p31comet make extensive contacts through large sets of hydrophobic and charged residues, constituting three main patches of interactions (Figure 4B-D). In the first patch, the C-terminal end of αC, the N-terminal portion of β8’, and the C-terminus of Mad2 interact extensively with αC of p31comet. In particular, T138, F141, and V181 in Mad2 form hydrophobic interactions with F195 and the aliphatic portion of the R192 side chain in p31comet (Figure 4B). The C-terminal carboxyl group and the side chain of D205 in Mad2 establish favorable electrostatic interactions with R188 and R189, respectively, in p31comet (Figure 4B). The second patch consists of the central parts of β8’ and αC in Mad2, and the loop between αC and β6 and the C-terminal tip of αA in p31comet. Bridged by several tightly bound water molecules, S130, R133, Q134, and R184 of Mad2 form an elaborate network of electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding interactions with Q83, Q85, D198, and the backbone carbonyl groups of residues 199-203 in p31comet (Figure 4C). Finally, the third patch involves a hydrophobic interaction between T140 at the C-terminal end of αC in Mad2 and F191 of p31comet (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Interactions between Mad2 and p31comet.

(A) Ribbon diagrams of the Mad2-p31comet complex. Two different views are shown to provide a clearer perspective of the Mad2-p31comet interface. Helix αC in Mad2 is colored cyan to highlight its central role in establishing interactions between Mad2 and p31comet. Three main patches of interactions at the Mad2-p31comet interface are labeled and circled with red dashed lines.

(B-D) Interactions between Mad2 and p31comet. The side chains of contacting residues are shown as sticks. Nitrogen and oxygen atoms are colored blue and red, respectively. Mad2 carbons are colored yellow while p31comet carbons are colored gray and labeled in italics. The tightly bound water molecules are drawn as red spheres in (C).

It has been previously shown that p31comet selectively binds to Mad1- or Cdc20-bound C-Mad2, but does not compete with Mad1 or Cdc20 for Mad2 binding (Mapelli et al., 2006; Xia et al., 2004). Our structure of Mad2-p31comet readily explains these observations. First, the p31comet-binding elements of Mad2 form a contiguous surface on the side of Mad2 that is opposite to its ligand-binding site (Figure 4A). As a result, there is no direct contact between p31comet and MBP1, consistent with the observation that p31comet does not disrupt the Mad1-Mad2 and Mad2-Cdc20 interactions. Second, as discussed above, strand β8’ and the C-terminus of Mad2 display extensive interactions with p31comet (Figure 4A). These structural elements are located in the C-terminal segment of Mad2 that undergoes a large structural rearrangement between O-Mad2 and C-Mad2 (Figure 2A-D). In O-Mad2, the C-terminal region forms a β hairpin (β7 and β8) and a flexible tail on the side of Mad2 that is distant to αC (Figure 2A,B). Thus, the C-terminal segment of O-Mad2 is not properly positioned to interact with p31comet, which provides the structural basis for the binding specificity of p31comet for C-Mad2 and the lack of binding to O-Mad2.

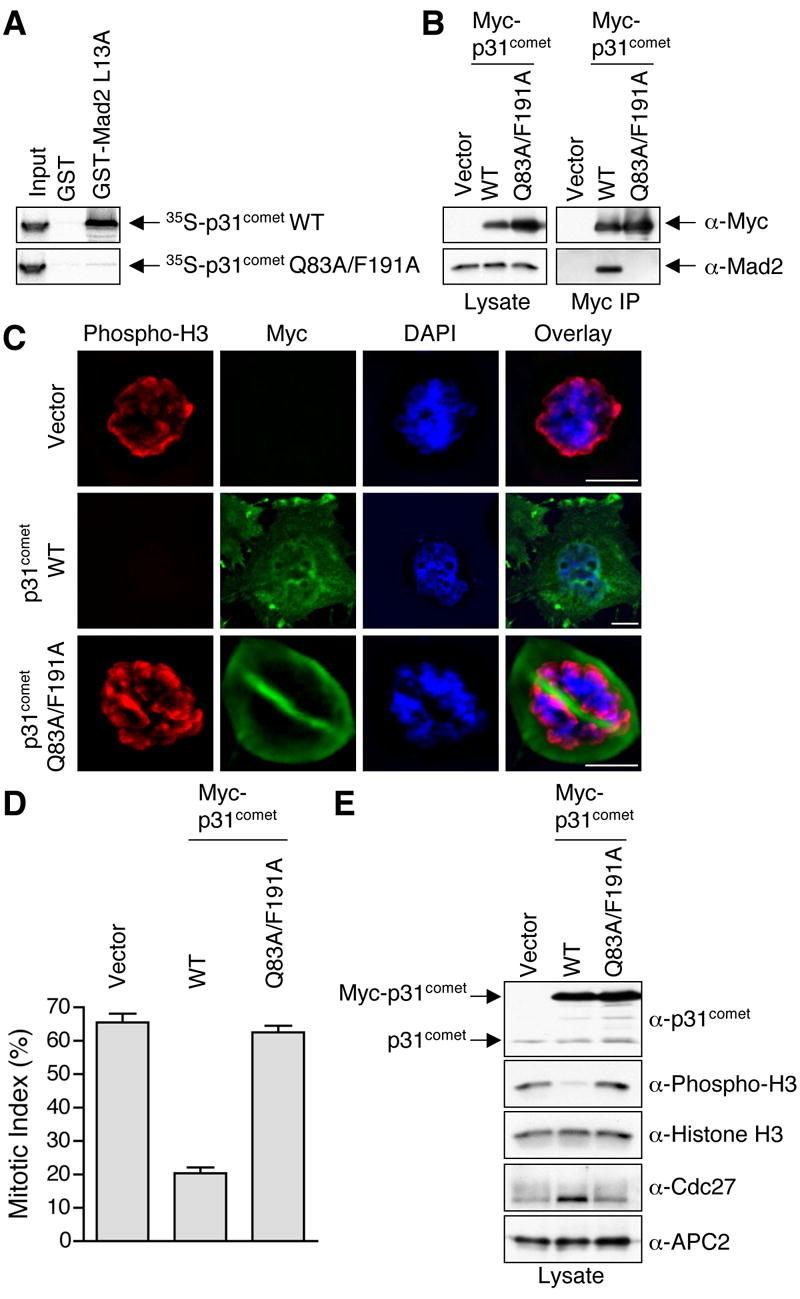

A p31comet Mutant Deficient in Mad2 Binding Fails to Override Nocodazole-triggered Mitotic Arrest

To validate the binding interactions between Mad2 and p31comet observed in our crystal structure, we performed systematic mutagenesis studies on both Mad2 and p31comet. Among the p31comet-binding residues in Mad2, mutations of R133, F141, and R184 significantly decreased p31comet binding (Figure S4). Consistent with our finding, an earlier study showed that several double mutants of Mad2, including R133E/Q134A, R133A/F141A, and R133A/R184A, failed to bind to p31comet (Mapelli et al., 2006). Among the Mad2-binding residues in p31comet, only mutations of Q83 and F191 greatly diminished Mad2 binding (Figure S5). While confirming the relevance of the Mad2-p31comet interface in our structure, these mutagenesis results also suggest that the interactions contributing to the binding energy between Mad2 and p31comet are not evenly distributed across this interface. Instead, there are hot spots of interactions that contribute the majority of the binding energy, reminiscent of the binding of human growth factor to its receptor (Clackson and Wells, 1995).

Previous studies have clearly demonstrated a role of p31comet in checkpoint inactivation (Habu et al., 2002; Reddy et al., 2007; Stegmeier et al., 2007; Xia et al., 2004). Though it is very likely that Mad2 binding is important for the function of p31comet, this notion has not been formally tested. Individual mutations of Q83 and F191 in p31comet greatly diminished, but did not abolish, Mad2 binding. We thus constructed the p31comet Q83A/F191A double mutant, which completely lost its ability to bind to Mad2 in vitro (Figure 5A). HeLa cells were transfected with a control plasmid or plasmids encoding Myc-p31comet wild type (WT) or the Q83A/F191A double mutant and treated with nocodazole, a spindle poison, to activate the spindle checkpoint. Myc-p31comet WT, but not Myc-p31comet Q83A/F191A, efficiently bound to the endogenous Mad2 protein (Figure 5B). Consistent with previous reports (Habu et al., 2002; Xia et al., 2004), overexpression of Myc-p31comet WT significantly decreased the percentage of cells arrested in mitosis in the presence of nocodazole (Figure 5C,D) and reduced the cellular levels of phospho-histone H3 and hyperphosphorylated Cdc27 (Figure 5E). In contrast, upon nocodazole treatment, expression of Myc-p31comet Q83A/F191A did not appreciably alter the mitotic index or the levels of phospho-histone H3 or Cdc27 hyperphosphorylation, as compared to the control plasmid (Figure 5C-E). Thus, mutations of p31comet that disrupt its binding to Mad2 also disrupt the ability of p31comet to overcome spindle checkpoint-dependent mitotic arrest. This finding further suggests that Mad2 binding by p31comet is critically important for its function in checkpoint silencing.

Figure 5. Mad2 Binding Is Required for the Function of p31comet in Checkpoint Silencing.

(A) 35S-labeled p31comet WT or Q83A/F191A proteins were incubated with beads bound to GST or GST-Mad2 L13A. After washing, proteins bound to beads were separated on SDS-PAGE and analyzed using a phosphoimager.

(B) HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and treated with nocodazole. Lysates of the transfected cells were immunoprecipitated using anti-Myc beads. Both the lysates and immunoprecipitates were blotted with the indicated antibodies.

(C) HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, treated with nocodazole, and stained with DAPI (blue), anti-Myc (green), and anti-phospho-H3 (red). Scale bars indicate 10 μm.

(D) The mitotic indices of the transfected cells in (C) were quantified. At least 400 cells were counted for each transfection. The averages and standard deviations of three separate experiments are shown.

(E) Lysates of cells described in (C-D) were blotted with the indicated antibodies.

Structural Basis for the Blockage of Mad2 Activation by p31comet

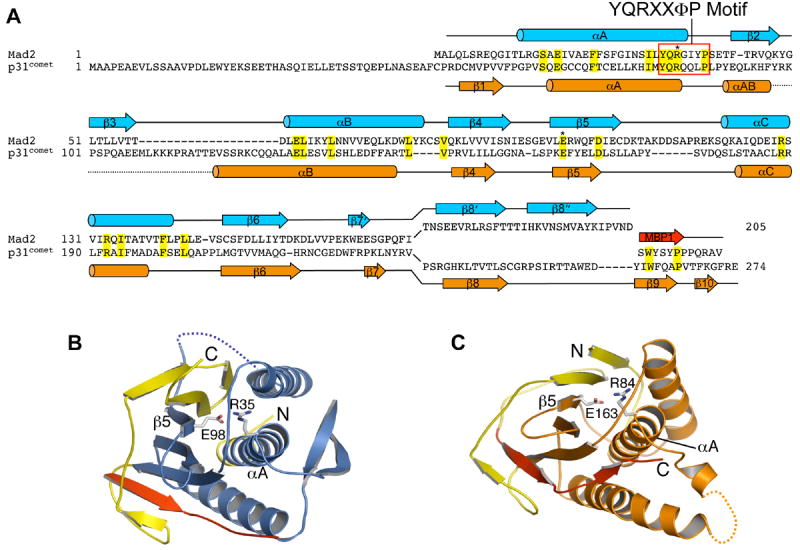

Binding of p31comet to Mad1-bound C-Mad2 blocks the recruitment of an additional copy of O-Mad2 to the Mad1-Mad2 core complex, thus preventing the generation of active Mad2 conformers, such as I-Mad2 and unliganded C-Mad2, and contributing to checkpoint inactivation (Figure 1A,B) (De Antoni et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2004; Mapelli et al., 2006; Yu, 2006). The structure of Mad2 bound to a fragment of Mad1 has been determined previously (Sironi et al., 2002). The Mad2 molecules in our Mad2-p31comet structure have virtually the same conformation as Mad1-bound Mad2, with backbone RMSDs of about 1 Å. By overlaying the Mad2 molecules in the Mad1-Mad2 and Mad2-p31comet structures, we constructed a structural model of the Mad1-Mad2-p31comet ternary complex (Figure 6A). In this model, there are no steric clashes between p31comet and Mad1 or between the two p31comet molecules, suggesting that the Mad2-p31comet binding mode in the Mad2-p31comet complex is compatible with the formation of the Mad1-Mad2-p31comet ternary complex. Mutations of Mad2 residues located on αC, including R133, Q134, and F141, are known to disrupt the dimerization of Mad2 and consequently its function in the spindle checkpoint (De Antoni et al., 2005; Mapelli et al., 2006; Sironi et al., 2001), indicating that αC is a major dimerization determinant of Mad2. Mapelli et al. have determined the crystal structure of the O-Mad2–C-Mad2 dimer (Mapelli et al., 2007). O-Mad2 indeed binds to a surface on C-Mad2 that includes αC and β8’ (Figure 6B,C). The p31comet-binding surface of Mad2 also contains αC and β8’ (Figure 6B,D). Thus, O-Mad2 and p31comet have largely overlapping binding surfaces on C-Mad2, providing a straightforward explanation for the ability of p31comet to block O-Mad2–C-Mad2 dimerization and to prevent structural activation of Mad2.

Figure 6. A Structure Model for the Blockage of Mad1-assisted Mad2 Activation by p31comet.

(A) A structural model of the Mad1-Mad2-p31comet complex. The Mad2 molecule in the Mad2-p31comet complex was superimposed with the Mad2 molecules in the Mad1-Mad2 complex (PDB ID 1GO4). For clarity, the Mad2 monomers in the Mad1-Mad2 complex are omitted. Mad1 is colored green with its Mad2-binding region colored red. The three interacting helices in Mad2-p31comet are indicated.

(B) A surface representation to show that C-Mad2 uses a similar surface for the binding of p31comet or O-Mad2. The p31comet-binding residues of C-Mad2 are colored yellow and the four key interacting residues, R133, Q134, R184 and F141, are colored red. The O-Mad2-binding residues of C-Mad2 are colored yellow. The same four residues R133, Q134, R184 and F141 (red) that are important for p31comet binding are also involved in O-Mad2 binding.

(C) Ribbon diagram of the O-Mad2–C-Mad2 dimer (Mapelli et al., 2007). O-Mad2 is colored in cyan. C-Mad2 is colored blue with its C-terminal region shown in yellow. MBP1 is in red. The αC helices are labeled.

(D) Ribbon diagram of the Mad2-p31comet complex with C-Mad2 in the same orientation as in (C).

(E) Overlay of ribbon diagrams of the O-Mad2–C-Mad2 dimer and the Mad2-p31comet complex. The C-Mad2 molecules in both structures are superimposed. The color scheme is the same as in (C) and (D).

An Allosteric Model for the Activation of O-Mad2 by the Mad1-Mad2 Core Complex

The Mad1-Mad2 core complex recruits a second O-Mad2 molecule through O-Mad2–C-Mad2 dimerization and converts O-Mad2 to I-Mad2 and unliganded C-Mad2, thus facilitating Mad2 binding to Cdc20 (De Antoni et al., 2005; Yu, 2006). However, the mechanism of Mad2 activation and the nature of I-Mad2 remain enigmatic. Conversion of O-Mad2 to C-Mad2 involves two main structural changes that occur at both sides of the Mad2 molecule. On one side, β1 in O-Mad2 dissociates from β5, traverses through the β5-αC loop, and forms an additional turn in αA. On the other side, the C-terminal region of O-Mad2 including β7, β8 and the flexible C-terminal tail dissociates from β6, rearranges into the β8’/8” hairpin, and undergoes translocation to pair with β5.

Several lines of evidence suggest that the dissociation of β1 and its traversing through the β5-αC loop are rate-limiting steps in the conversion of O-Mad2 to C-Mad2. First, our hydrogen/deuterium exchange experiments show that the amide protons of residues in β1 of O-Mad2 undergo slow exchange with solvent (X.L., unpublished results). In contrast, despite that β8 is much longer than β1, all amide protons of residues within β8 in O-Mad2 are fast-exchanging with solvent. These results suggest that the pairing between β1 and β5 is more stable than that between β8 and β6 in O-Mad2. Second, the L13A mutation destabilizes a hydrophobic core that maintains the association between β1 and β5, and consequently Mad2 L13A adopts exclusively the C-Mad2 fold. Third, addition of a longer flexible tag at the N-terminus of Mad2 prevents the conversion of O-Mad2 to C-Mad2 (X.L., unpublished results). Finally, Mapelli et al. have shown that a Mad2 mutant with a shorter β5-αC loop called loop-less Mad2 (Mad2LL) is locked into the open conformation (Mapelli et al., 2007). The last two results suggest that traversing of the N-terminal region of Mad2 through the β5-αC loop is an important step during the conversion from O-Mad2 to C-Mad2.

In an accompanying paper, Mapelli et al. have determined the structure of Mad2LL bound to C-Mad2 (Figure 6C) (Mapelli et al., 2007). Mad2LL bound to C-Mad2 has a fold identical to that of the free O-Mad2 (Luo et al., 2000; Mapelli et al., 2007). However, NMR studies of Mad2ΔC (a Mad2 mutant that lacks the C-terminal 10 residues and only adopts the O-Mad2 conformation) bound to Mad2-MBP1 revealed that binding of C-Mad2 converts O-Mad2 to an intermediate Mad2 conformer (I-Mad2) that is structurally distinct from O-Mad2 (Mapelli et al., 2006). Thus, the structure of Mad2LL–C-Mad2 likely depicts the initial docking complex between O-Mad2 and C-Mad2 in the Mad1-Mad2 core complex (Figure 1A), not that between I-Mad2 and C-Mad2.

On the other hand, p31comet has a fold closely related to that of Mad2. p31comet and O-Mad2 bind to similar surfaces on C-Mad2. Conversely, the C-Mad2-binding site of p31comet includes its αC, αA, and the short helix connecting αA and αB (Figure 6D). Likewise, the C-Mad2-binding site of O-Mad2 is comprised of its αC, αA, and the β2/3 hairpin that connects αA and αB (Figure 6C). Therefore, p31comet and O-Mad2 use equivalent structural elements for binding to C-Mad2 (Figure 2 and 6C,D). However, when the C-Mad2 molecules in the structures of O-Mad2–C-Mad2 and p31comet–C-Mad2 are superimposed, the equivalent structural elements of p31comet and O-Mad2 do not overlay well (Figure 6E). In fact, if we superimposed O-Mad2 with p31comet in our Mad2-p31comet structure, αC and the tip of the β2/3 hairpin in O-Mad2 would have severe steric clashes with αC of C-Mad2 (Figure S6A). Thus, an intriguing possibility is that the binding mode of p31comet on C-Mad2 mimics that of I-Mad2 on C-Mad2, rather than that of O-Mad2. Binding of C-Mad2 might induce the unfolding of the β2/3 hairpin and a rotation of αC in O-Mad2 to alleviate the steric clashes between O-Mad2 and C-Mad2 in our model (Figure S6A). The rotation of αC in O-Mad2 is expected to destabilize the hydrophobic core that involves residues on β1, including L13 (Figure S6B). Disruption of this hydrophobic core could facilitate dissociation of β1 from β5, a possible rate-limiting step in the conversion from O-Mad2 to C-Mad2. Dissociation of β1 and its traversing through the β5-αC loop might then allow the translocation of the β8’/8” hairpin to pair with β5, thus generating C-Mad2 (Figures S6). The structures of Mad2-p31comet and O-Mad2–C-Mad2 provide the basis for designing future experiments that can test this model for the structural activation of Mad2. Furthermore, it is possible that the Mad2-p31comet interaction is spatially and temporally regulated during mitosis. The structure of Mad2-p31comet will help us understand the regulatory mechanisms of p31comet, once these mechanisms are discovered.

CONCLUSION

The crystal structure of the Mad2-p31comet complex reveals the structural basis for how p31comet acts as an anti-Mad2 in checkpoint inactivation, and further suggests an allosteric mechanism for the activation of the two-state protein Mad2 by the Mad1-Mad2 core complex. Our studies provide a striking illustration of how two proteins with similar folds can play antagonistic roles in the same signaling pathway.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Purification and Crystallization

The coding regions of human Mad2 and human p31cometΔN35 (residues 36-274) were cloned into pETDuet-1 (Novagen). The L13A mutation was introduced into pETDuet-1-Mad2-p31comet with the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Expression of pETDuet-1-Mad2 L13A-p31comet in the bacterial strain BL21(DE3) produced N-terminal His6-tagged Mad2 L13A and untagged p31comet proteins. The Mad2 L13A-p31comet complex was isolated from bacterial lysate by affinity chromatography using Ni2+-NTA agarose resin (Qiagen) and cleaved with TEV protease to remove the His6-tag. The complex was further purified by anion exchange chromatography using a resource Q column followed by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex S200 column. After addition of MBP1 at a 1:1 molar ratio, the resulting Mad2 L13A-p31comet-MBP1 complex was concentrated to 8 mg/ml in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, and 5 mM DTT. The seleno-methionine labeled Mad2 L13A-MBP1-p31comet complex was prepared similarly. The Mad2 L13A-MBP1-p31comet complex was crystallized at 16°C by the vapor-diffusion method in hanging-drop mode with a reservoir solution containing 16% (w/v) PEG 3350, 125 mM sodium phosphate (pH 5.0), and 25 mM DTT. The crystals were cryo-protected with reservoir solution supplemented with 16% (v/v) glycerol and then flash-cooled in liquid propane. Crystals exhibited the symmetry of space group P212121 with cell dimensions of a = 69 Å, b = 105 Å, c = 139 Å and contained two complexes per asymmetric unit.

Data Collection and Structure Determination

All data sets were collected at beamline 19-ID (SBC-CAT) at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, Illinois, USA) and processed with HKL2000 (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). Crystals diffracted to a minimum Bragg spacing (dmin) of about 2.3 Å. Phases were obtained from a selenium-SAD experiment using X-rays with an energy near the selenium K absorption edge. Using data to 3.0 Å, 14 of 14 possible selenium sites were located and refined with the program SHELX (Schneider and Sheldrick, 2002; Sheldrick, 2002). Phases were subsequently extended to 2.3 Å and refined with the program MLPHARE (Otwinowski, 1991), resulting in an overall figure of merit of 0.25. Phases were further improved by density modification with histogram matching and two-fold non-crystallographic averaging in the program DM (Cowtan and Main, 1998), resulting in a final overall figure of merit of 0.75. The resulting electron density map was of sufficient quality to automatically construct an initial model using the program ARP/warp (Perrakis et al., 1999). This model was used as a starting model for the refinement using the programs CNS (Brünger et al., 1998) and REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 1997) from the CCP4 package (Consortium, 1994; Murshudov et al., 1997), interspersed with manual rebuilding using the programs Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) and O (Jones et al., 1991). Analysis of the original dataset used for phasing revealed significant radiation decay, which was most significantly manifested through reduced electron density for the disulfide bond formed in Mad2A between C79 and C106 (this disulfide bond was not observed in Mad2C), and increased disorder in the electron density map in this region. A modified dataset was generated that incorporated only about the first 60% of the original data, which was then used for the final rounds of refinement. The electron density maps calculated from this modified dataset were more easily interpretable and the refinement was more stable (Table 1).

Mammalian Tissue Culture, Immunoprecipitation and Protein Binding Assays

HeLa Tet-on (Invitrogen) cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were transfected with pCS2-p31comet vectors using Effectene (Qiagen). After 24 hrs, the cells were treated with 100 ng/ml nocodazole (Sigma) for 16 hrs, stained with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma), and examined using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Zeiss). Cells were also fixed and stained with DAPI and antibodies against Myc and phospho-histone H3 as described (Tang et al., 2006). Lysates of the transfected cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting using the appropriate antibodies. For in vitro protein binding assays, GST-Mad2 proteins were bound to glutathione-agarose beads and incubated with 35S-labeled p31comet proteins obtained using in vitro translation in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (Promega). After washing, proteins bound to beads were resolved on SDS-PAGE and analyzed using a phosphoimager (Fuji).

Supplementary Material

01

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Nick Grishin for his help with sequence analysis of p31comet and Mad2 and Minghua Wen for her technical support. We also thank Dr. Lin Chen and Dr. Aidong Han for their suggestions and discussion. Results shown in this report are derived from work performed at Argonne National Laboratory, Structural Biology Center at the Advanced Photon Source. Argonne is operated by University of Chicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (to X.L. and H.Y.) and the Welch Foundation (to H.Y. and J.R.).

Footnotes

Accession Number The atomic coordinates of the Mad2-MBP1-p31comet ternary complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 2QYF.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bharadwaj R, Yu H. The spindle checkpoint, aneuploidy, and cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:2016–2027. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clackson T, Wells JA. A hot spot of binding energy in a hormone-receptor interface. Science. 1995;267:383–386. doi: 10.1126/science.7529940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium TC. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowtan K, Main P. Miscellaneous algorithms for density modification. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:487–493. doi: 10.1107/s0907444997011980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Antoni A, Pearson CG, Cimini D, Canman JC, Sala V, Nezi L, Mapelli M, Sironi L, Faretta M, Salmon ED, Musacchio A. The Mad1/Mad2 complex as a template for Mad2 activation in the spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr Biol. 2005;15:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang G, Yu H, Kirschner MW. The checkpoint protein MAD2 and the mitotic regulator CDC20 form a ternary complex with the anaphase-promoting complex to control anaphase initiation. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1871–1883. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habu T, Kim SH, Weinstein J, Matsumoto T. Identification of a MAD2-binding protein, CMT2, and its role in mitosis. EMBO J. 2002;21:6419–6428. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang LH, Lau LF, Smith DL, Mistrot CA, Hardwick KG, Hwang ES, Amon A, Murray AW. Budding yeast Cdc20: a target of the spindle checkpoint. Science. 1998;279:1041–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5353.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47(Pt 2):110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Lin DP, Matsumoto S, Kitazono A, Matsumoto T. Fission yeast Slp1: an effector of the Mad2-dependent spindle checkpoint. Science. 1998;279:1045–1047. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5353.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Fang G, Coldiron M, Lin Y, Yu H, Kirschner MW, Wagner G. Structure of the Mad2 spindle assembly checkpoint protein and its interaction with Cdc20. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:224–229. doi: 10.1038/73338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Tang Z, Rizo J, Yu H. The Mad2 spindle checkpoint protein undergoes similar major conformational changes upon binding to either Mad1 or Cdc20. Mol Cell. 2002;9:59–71. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00435-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Tang Z, Xia G, Wassmann K, Matsumoto T, Rizo J, Yu H. The Mad2 spindle checkpoint protein has two distinct natively folded states. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nsmb748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapelli M, Filipp FV, Rancati G, Massimiliano L, Nezi L, Stier G, Hagan RS, Confalonieri S, Piatti S, Sattler M, Musacchio A. Determinants of conformational dimerization of Mad2 and its inhibition by p31comet. EMBO J. 2006;25:1273–1284. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapelli M, Massimiliano L, Santaguida S, Musacchio A. The Mad2 Conformational Dimer: Structure and Implications for the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint. Cell. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.049. in revision. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A, Hardwick KG. The spindle checkpoint: structural insights into dynamic signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:731–741. doi: 10.1038/nrm929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A, Salmon ED. The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:379–393. doi: 10.1038/nrm2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. Isomorphous Replacement and Anomalous Scattering. In: Wolf W, Evans PR, Leslie AGW, editors. Science and Engineering Research Council. 1991. pp. 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis A, Morris R, Lamzin VS. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:458–463. doi: 10.1038/8263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy SK, Rape M, Margansky WA, Kirschner MW. Ubiquitination by the anaphase-promoting complex drives spindle checkpoint inactivation. Nature. 2007;446:921–925. doi: 10.1038/nature05734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM. Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1772–1779. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah JV, Botvinick E, Bonday Z, Furnari F, Berns M, Cleveland DW. Dynamics of centromere and kinetochore proteins; implications for checkpoint signaling and silencing. Curr Biol. 2004;14:942–952. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick GM. Macromolecular phasing with SHELXE. Zeitschrift Fur Kristallographie. 2002;217:644–650. [Google Scholar]

- Sironi L, Mapelli M, Knapp S, De Antoni A, Jeang KT, Musacchio A. Crystal structure of the tetrameric Mad1-Mad2 core complex: implications of a ‘safety belt’ binding mechanism for the spindle checkpoint. EMBO J. 2002;21:2496–2506. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.10.2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sironi L, Melixetian M, Faretta M, Prosperini E, Helin K, Musacchio A. Mad2 binding to Mad1 and Cdc20, rather than oligomerization, is required for the spindle checkpoint. EMBO J. 2001;20:6371–6382. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegmeier F, Rape M, Draviam VM, Nalepa G, Sowa ME, Ang XL, McDonald ER, 3rd, Li MZ, Hannon GJ, Sorger PK, et al. Anaphase initiation is regulated by antagonistic ubiquitination and deubiquitination activities. Nature. 2007;446:876–881. doi: 10.1038/nature05694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z, Shu H, Qi W, Mahmood NA, Mumby MC, Yu H. PP2A is required for centromeric localization of Sgo1 and proper chromosome segregation. Dev Cell. 2006;10:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia G, Luo X, Habu T, Rizo J, Matsumoto T, Yu H. Conformation-specific binding of p31(comet) antagonizes the function of Mad2 in the spindle checkpoint. EMBO J. 2004;23:3133–3143. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H. Regulation of APC-Cdc20 by the spindle checkpoint. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:706–714. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00382-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H. Structural activation of Mad2 in the mitotic spindle checkpoint: the two-state Mad2 model versus the Mad2 template model. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:153–157. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H. Cdc20: a WD40 activator for a cell cycle degradation machine. Mol Cell. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.009. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

01