Sestrin as a feedback inhibitor of TOR that prevents age-related pathologies (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 Mar 5.

Published in final edited form as: Science. 2010 Mar 5;327(5970):1223–1228. doi: 10.1126/science.1182228

Abstract

Sestrins are conserved proteins that accumulate in cells exposed to stress and potentiate adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and inhibit activation of target of rapamycin (TOR). We show that abundance of Drosophila Sestrin (dSesn) is increased upon chronic TOR activation through accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and transcription factor FoxO (Forkhead box O). Loss of dSesn resulted in age-associated pathologies including triglyceride accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, muscle degeneration and cardiac malfunction, which were prevented by pharmacological activation of AMPK or inhibition of TOR. Hence, dSesn appears to be a negative feedback regulator of TOR that integrates metabolic and stress inputs and prevents pathologies caused by chronic TOR activation, that may result from diminished autophagic clearance of damaged mitochondria, protein aggregates, or lipids.

TOR (target of rapamycin) is a key protein kinase that regulates cell growth and metabolism to maintain cellular and organismal homeostasis (1-3). Insulin (Ins) and insulin-like growth factors (IGF) are major TOR activators that operate through phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and the protein kinase AKT (2). Conversely, adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK), which is activated upon energy depletion, caloric restriction (CR), or genotoxic damage, is a stress-responsive inhibitor of TOR activation (2, 4). TOR stimulates cell growth and anabolism by increasing protein and lipid synthesis through p70 S6 kinase (S6K), eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein (4E-BP), and sterol response element binding protein (SREBP) (1-3, 5) and by decreasing autophagic catabolism through phosphorylation-mediated inhibition of ATG1 protein kinase (1, 6). Persistent TOR activation is associated with diverse pathologies such as cancer, diminished cardiac performance, and obesity-associated metabolic diseases (1). Conversely, inhibition of TOR prolongs life span and increases quality-of-life by reducing the incidence of age-related pathologies (1-3, 7). The anti-aging effects of CR could be due to inhibition of TOR (8).

Sestrins (Sesns) are highly conserved proteins that accumulate in cells exposed to stress, lack obvious domain signatures, and have poorly defined physiological functions (9, 10). Mammals express three Sesns, whereas D. melanogaster and C. elegans have single orthologues (fig. S1, A and B). In vitro, Sesns exhibit oxidoreductase activity and may function as antioxidants (11). Independently of their redox activity, Sesns lead to AMPK-dependent inhibition of TOR signaling and link genotoxic stress to TOR regulation (12). However, Sesns are also widely expressed in the absence of exogenous stress, and in Drosophila, expression of dSesn is increased upon maturation and aging (fig. S1C) (10). Given the redundancy between mammalian Sesns, we chose to test the importance of Sesns as regulators of TOR function in Drosophila. We generated both gain and loss of function dSesn mutants (fig. S2 to S4), whose analysis revealed that dSesn is an important negative feedback regulator of TOR whose loss results in various TOR-dependent, age-related pathologies.

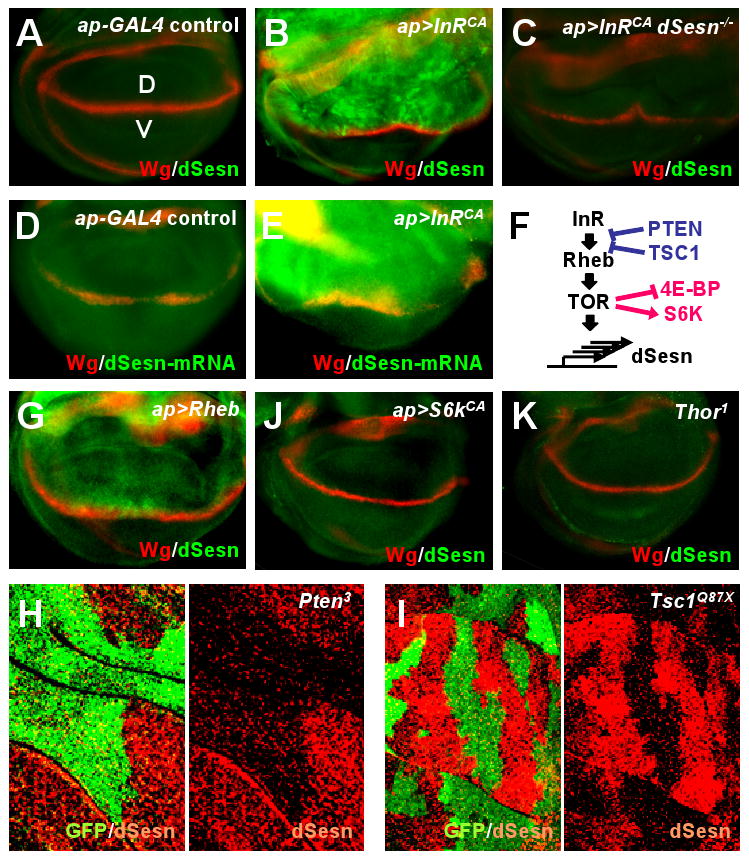

Prolonged TOR signaling induces dSesn

Persistent TOR activation in wing discs by a constitutively active form of insulin receptor (InRCA) resulted in prominent dSesn protein accumulation, not seen in a _dSesn_-null larvae (Fig. 1, A to C). InRCA also induced accumulation of dSesn RNA (Fig. 1, D to F), indicating that dSesn accumulation is due to increased transcription or mRNA stabilization. As dSesn accumulation was restricted to cells in which TOR was activated, the response is likely to be cell autonomous. dSesn was also induced when TOR was chronically activated by overexpression of the small guanine triphosphatase Rheb (Fig. 1G), or clonal loss of PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) or TSC1 (tuberous sclerosis complex 1) (Fig. 1, H and I). Dominant-negative PI3K (PI3KDN) or TOR (TORDN) inhibited dSesn accumulation caused by overexpression of InRCA, but inactive ribosomal S6 protein kinase (S6K; S6KDN) and hyperactive 4E-BP (4E-BPCA), two downstream TOR effectors, did not (fig. S5). Furthermore, dorsal-specific expression of activated S6KCA or loss of 4E-BP activity failed to induce dSesn expression (Fig. 1, J and K), indicating that TOR regulates expression of dSesn through different effector(s).

Fig. 1.

Increased abundance of dSesn upon TOR activation. Larval wing discs of indicated strains were stained to visualize indicated proteins or mRNA. The dorsal side points upwards. Dorsoventral boundary (D/V in A) was visualized by staining with an antibody to the wingless (Wg) protein (red). (A to C) Expression of dSesn protein (green) in the absence (A) or presence of InRCA in WT (B) and _dSesn_-null (C) strains. (D and E) Accumulation of dSesn mRNA (green) in response to InRCA detected by in situ hybridization. (F) The signaling network controlling TOR activity and expression of dSesn. (G to K) Accumulation of dSesn (green) in response to Rheb (G) but not S6KCA (J) or loss of 4E-BP (K). Thor1 is a Drosophila 4E-BP loss-of-function mutant. (H and I) Accumulation of dSesn after somatic loss of PTEN (H) or TSC1 (I). Absence of GFP (green) indicates loss of PTEN or TSC1 resulting in dSesn (red) accumulation.

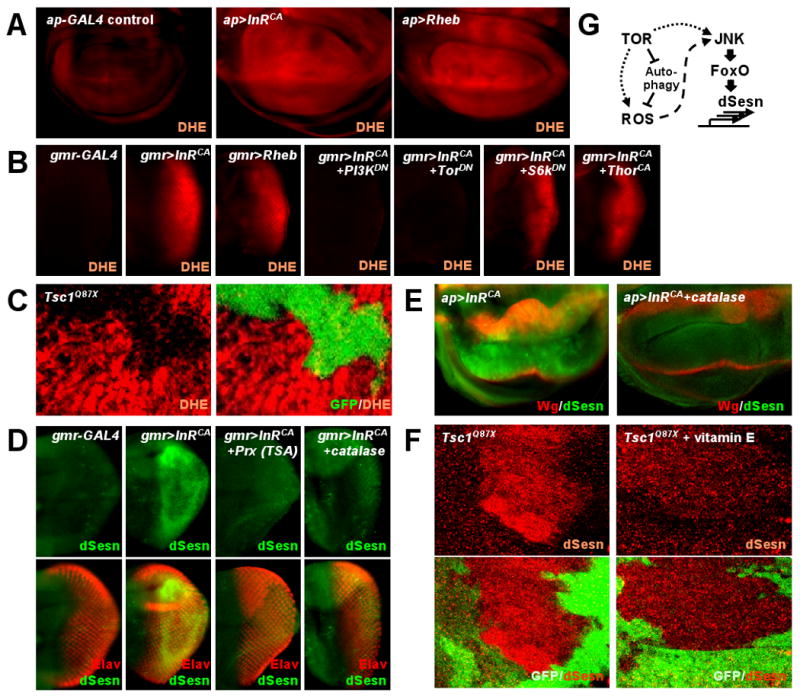

TOR signaling generates ROS to induce dSesn

In mammals, transcription of Sesn genes is increased in cells exposed to oxidative stress (9, 11) and we observed ROS accumulation, detected by oxidation of dihydroethidium (DHE), in the same region of the imaginal discs in which InRCA or Rheb were expressed (Fig. 2, A and B). InRCA-induced accumulation of ROS was blocked by co-expression of either PI3KDN or TORDN, but not S6KDN or 4E-BPCA (Fig. 2B), revealing TOR's role in ROS accumulation. Wing-disc clones in which TOR was activated by loss of TSC1 also exhibited ROS accumulation (Fig. 2C), confirming that TOR-dependent ROS accumulation is cell-autonomous. Expression of the ROS scavengers catalase or peroxiredoxin (13) inhibited InRCA-induced accumulation of dSesn (Fig. 2, D and E). Feeding animals with vitamin E, an antioxidant, also prevented dSesn induction caused by TSC1 loss (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Chronic TOR activation results in accumulation of ROS and dSesn. Larval imaginal discs of indicated strains were stained as indicated. (A) ROS accumulation (red) in response to InRCA or Rheb overexpressed in dorsal (upwards) wing discs was revealed by DHE staining. (B) InRCA-induced ROS (red) accumulation in eye discs was reduced by PI3KDN or TORDN but not by S6KDN or 4E-BPCA. (C) DHE staining (red) in TSC1-negative wing disc clones marked by absence of GFP. (D and E) Inhibition of InRCA-induced accumulation of dSesn (green) in eye and wing discs by expression of catalase or peroxiredoxin (Prx). D-V wing boundary and differentiated eye area were visualized by Wg (red) and Elav (red) staining, respectively. (F) dSesn accumulation (red) in TSC1-negative wing disc clones was suppressed by vitamin E feeding. Absence of GFP (green) indicates loss of TSC1. (G) Diagram depicting TOR-stimulated production of ROS and expression of dSesn.

FoxO and p53 are ROS-activated transcription factors that control mammalian Sesn genes (9-12, 14). The dSesn locus contains 8 perfect FoxO-response elements (fig. S6A), a frequency 25-times higher than that expected on the basis of random distribution. Overexpressed FoxO or p53 could both increase expression of the dSesn gene (fig. S6, B to D). However, InRCA caused accumulation of dSesn in a _p53_-null background (fig. S6E), but not in a _FoxO_-null background (fig. S6, F and J), indicating that TOR-activated FoxO (fig. S6, K to M) (15) is likely to be the regulator of dSesn gene transcription. Indeed, accumulation of dSesn in response to Rheb overexpression was also FoxO-dependent (fig. S6, G and H).

In dorsal wing disc cells, where ROS accumulated in response to InRCA (Fig. 2A), JNK, a protein kinase that phosphorylates FoxO (13, 14), was also activated (fig. S7, A and B). JNK activation was diminished in cells overexpressing catalase (fig. S7C), suggesting that it depends on TOR-induced accumulation of ROS. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 (MKK7)-mediated activation of JNK also resulted in accumulation of dSesn (fig. S7, D and E), as did overexpression of Mst1 (mammalian STE20-like kinase 1), another protein kinase that phosphorylates FoxO (16), (fig. S7F). However, only JNKDN, but not Mst1DN, inhibited InRCA-mediated accumulation of dSesn (fig. S7, G and H). Collectively, these data suggest that dSesn transcription is increased upon chronic TOR activation through ROS-dependent activation of JNK and FoxO (Fig. 2G).

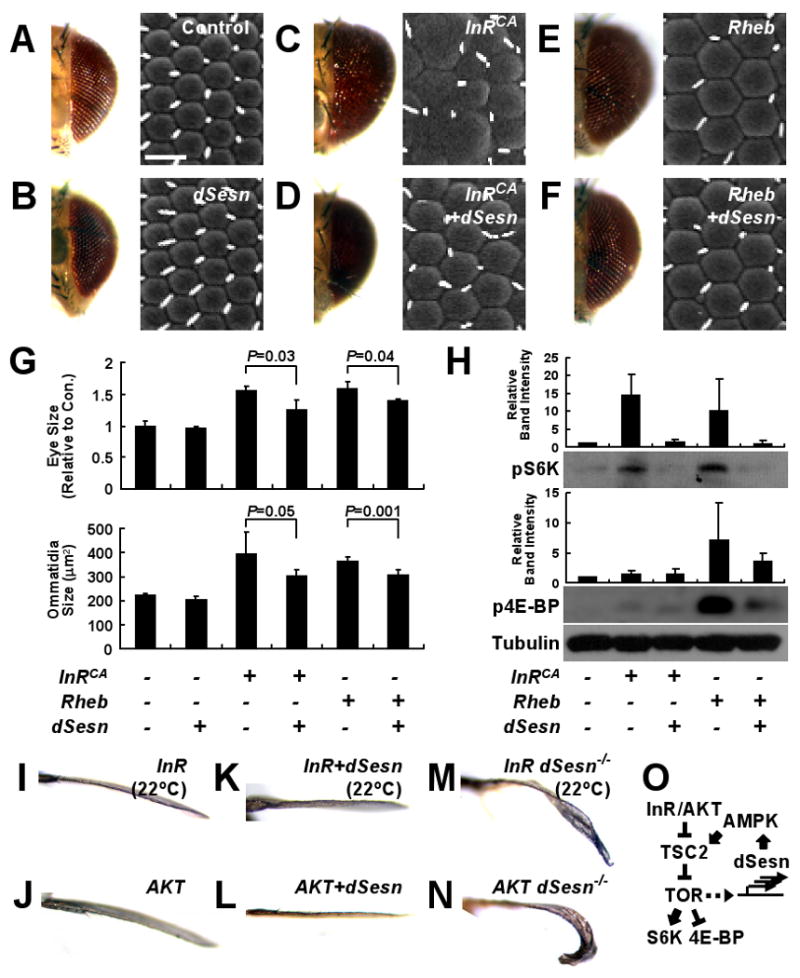

dSesn antagonizes TOR-dependent cell and tissue growth

To determine effects of dSesn on cell growth, a major function of TOR (1-3), we overexpressed dSesn in dorsal wings (fig. S2F). This resulted in a dose-dependent phenotype in which the wing bends upwards (fig. S8, A to D), indicating suppressed dorsal tissue growth. A dSesnC86S variant, in which the cysteine required for oxidoreductase activity was mutated (11), still conferred this phenotype (fig. S8, E and F) when expressed in amounts similar to those of dSesnWT (fig. S3, A to D). We measured cell number and size in a dorsal wing region defined by the L3, L4, C1 and C2 veins (shaded in pink in fig. S8, G and H). Although the size of this area was significantly reduced by dSesn expression (fig. S8I), cell number remained unchanged (fig. S8J), showing that decreased cell size (fig. S8K) can account for dSesn suppression of tissue growth. Overexpression of dSesn also reduced cell size in larval wing discs (fig. S9) and adult eyes (fig. S10). Thus, dSesn inhibits cell growth without affecting cell proliferation independently of its redox activity.

When dSesn was expressed with InRCA or Rheb, it suppressed the hyperplastic phenotypes caused by these TOR activators (Fig. 3, A to F). Both eye and individual ommatidia sizes were significantly reduced (Fig. 3G). dSesn also inhibited InRCA- or Rheb-induced phosphorylation of TOR targets S6K and 4E-BP (Fig. 3H). In mammalian cells, dSesn enhanced AMPK-induced phosphorylation of TSC2 and inhibited S6K activity through TSC2 (fig. S11, A to C), just as mSesn2 does (12). In Drosophila wings, dSesn-induced growth suppression was attenuated by reduced gene dosage of TSC1, TSC2 or AMPK although reduced dosage of these genes alone did not affect normal growth (fig. S11, D and E). Expression of mSesn1/2 in flies (fig. S3, E and F) also reduced normal (fig. S12, A to C) and InRCA-induced hyperplastic (fig. S12D) growth.

Fig. 3.

Antagonism of TOR-stimulated growth by dSesn. (A to F) Light (left) and scanning electron (right) micrographs of eyes expressing the indicated genetic elements driven by gmr-GAL4. Scale bar, 20 μm. (G) Quantification of eye and ommatidia sizes measured from frontal and lateral views, respectively. P values were calculated by one-way ANOVA. Error bars=S.D.; n=3 and 5, respectively. (H) Suppression of TOR signaling by dSesn. Adult heads with eye-specific expression of indicated genetic elements driven by _gmr_-GAL4 were subjected to immunoblot analyses with indicated antibodies. Relative band intensities were quantified and are presented as bar graphs. Error bars=S.D. n=3. (I to N) Suppression of InR-induced growth by dSesn. Anterior views of wing blades with _apterous-GAL4_-driven expression of indicated genetic elements. Dorsal sides point upwards. (O) Schematic diagram summarizing genetic interactions between dSesn and TOR signaling components.

Expression of InR, constitutively active PI3K (PI3KCA), AKT, or S6KCA in dorsal wing caused an overgrowth phenotype in which the wing bends downwards (Fig. 3, I and J; fig. S13, A to D). dSesn expression reversed this effect of overexpressed InR, PI3KCA and AKT, but not that of S6KCA (Fig. 3, K and L; fig. S13, E to H), suggesting that dSesn inhibits TOR downstream of AKT. Conversely, dorsal wing-specific expression of PTEN and dominant-negative InR (InRDN), PI3KDN, or S6KDN caused wings to bend upwards (fig. S13, I to L), and this effect was enhanced by dSesn (fig. S13, M to P).

Although _dSesn_-null flies did not exhibit developmental abnormalities, the growth promoting-effect of overexpressed InR or AKT was enhanced in _dSesn_-null background (Fig. 3, M and N; fig. S14, A and B), suggesting that endogenous dSesn restricts TOR activation and its growth promoting effect. Loss of dSesn, however, did not enhance S6K-stimulated cell growth (fig. S14, C to F) or decrease growth suppression by overexpressed InRDN or S6KDN (fig. S14, G to J). These findings indicate that Sesn is an evolutionarily conserved inhibitor of TOR signaling that acts via the AMPK-TSC2 axis (Fig. 3O).

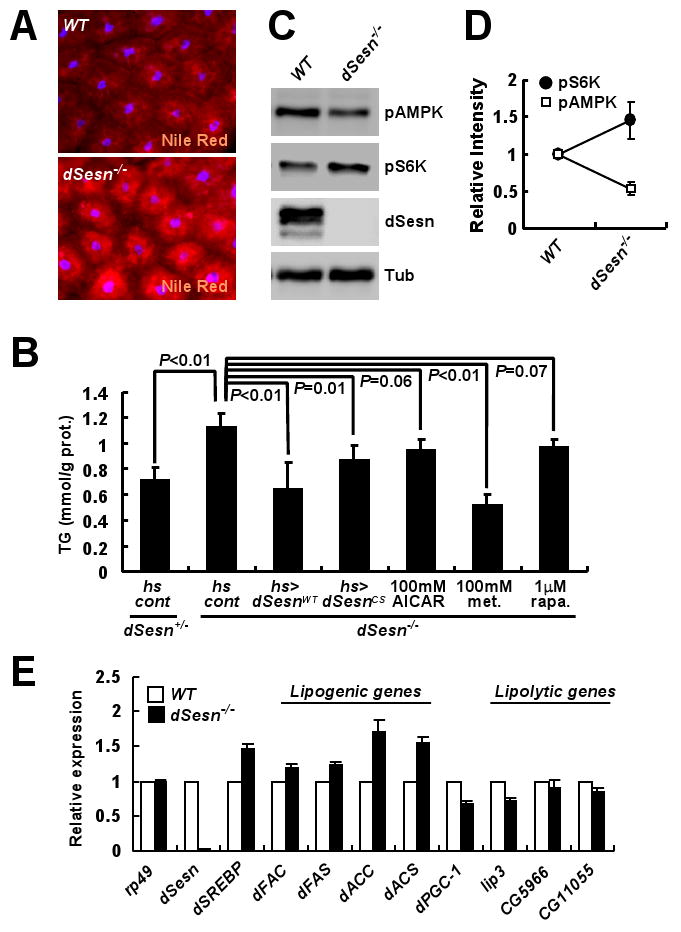

dSesn reduces lipid accumulation

Fat bodies from _dSesn_-null third-instar larvae contained more lipids than did those of WT animals (Fig. 4A). _dSesn_-null adults also contained more triglycerides, which were decreased after ectopic expression of dSesnWT or dSesnCS (Fig. 4B; fig. S15). Thus, the TOR-inhibitory function of dSesn rather than its antioxidant activity appears to affect metabolic control. Congruently, _dSesn_-null fat bodies showed decreased AMPK and increased TOR activities (Fig. 4, C and D). Pharmacological manipulation strengthened this conclusion; feeding _dSesn_-null mutants with AMPK-activators such as AICAR (5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide 1-β-D-ribofuranoside) or metformin (4), or the TOR-inhibitor rapamycin (2) reduced triglyceride accumulation (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Effect of dSesn on lipid homeostasis. (A) Lipid accumulation in fat bodies examined by Nile Red staining (red). (B) Total triglycerides were measured in five 10-day-old adult males of the indicated genotypes subjected to the indicated treatments (met., metformin; rapa., rapamycin). P values were calculated by one-way ANOVA. Error bars=S.D.; n≥3. (C and D) Protein lysates from fat bodies were analyzed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. Relative band intensities were quantified and are shown as a bar graph. Error bars=S.D.; n=3. (E) Expression of indicated mRNAs in adult flies was examined by quantitative RT-PCR. Fifty 3-day-old adult males of each genotype were used to prepare total RNA. Error bars=S.D.; n=3.

Expression of the gene encoding transcription factor dSREBP (5, 17) and its targets, which encode fatty acyl CoA synthetase (dFAC), fatty acid synthase (dFAS), acetyl CoA carboxylase (dACC) and acetyl CoA synthetase (dACS) (17), was significantly increased (20-70%) in _dSesn_-null mutants (Fig. 4E). However, the PPAR-gamma coactivator 1 (dPGC-1) gene and some lipolytic genes showed decreased expression. This is consistent with reports that dSREBP and dPGC-1 are diametrically regulated by TOR and AMPK, respectively, to properly control lipid metabolism (1, 2, 4, 5).

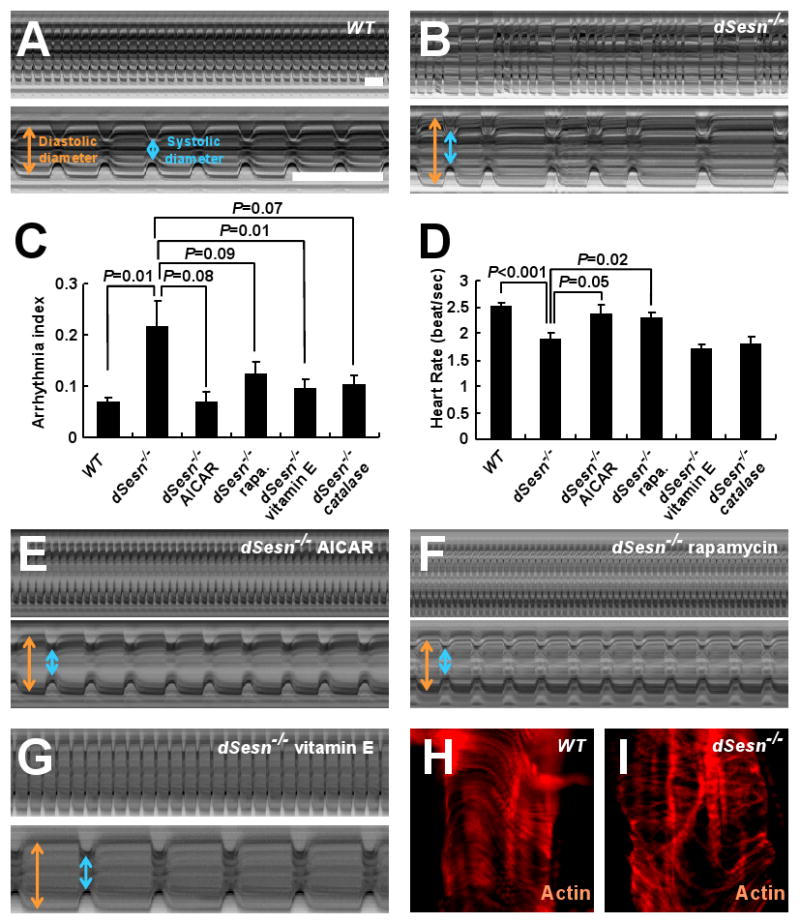

dSesn mutants exhibit a decline in cardiac performance

Age-related decline in heart performance is another phenotype associated with TOR hyperactivity in insects and mammals (18-20). In WT flies, the heart beats in a highly regular manner (Fig. 5A; movie S1), but in _dSesn_-null mutants heart function was compromised (Fig. 5B; movie S2) as manifested by arrhythmia (Fig. 5C) and decreased heart rate (Fig. 5D). Slowing of heart rate reflected expansion of the diastolic period (fig. S16A), as observed in aged or TOR-activated flies (18, 21). These defects were largely prevented by feeding flies AICAR (Fig. 5E; movie S3) or rapamycin (Fig. 5F; movie S4), indicating they are caused by low activity of AMPK or high TOR activity. Vitamin E feeding or catalase expression suppressed the arrhythmia caused by loss of dSesn (Fig. 5, C and G) but not the decrease in heart rate (Fig. 5D), suggesting that TOR-induced oxidative stress contributes to the arrhythmic phenotype. Analysis of F-actin revealed structural disorganization of myofibrils in _dSesn_-null hearts (Fig. 5, H and I), suggesting that cardiac muscle degeneration may cause some of the functional defects in _dSesn_-null hearts. Reflecting this structural abnormality, _dSesn_-null hearts were dilated during both the diastolic and systolic phases, and this was prevented by AICAR or rapamycin (fig. S16B).

Fig. 5.

Effect of dSesn on cardiac function. (A, B, E to G) Representative M mode records of indicated 2-week-old flies fed without or with indicated drugs, showing movement of heart tube walls (y-axis) over time (x-axis). Diastolic (orange) and systolic (blue) diameters are indicated. 1 second is indicated as a bar. (C and D) Quantification of cardiac function parameters. P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA. Error bars indicate S.E.M.; n>10. (H and I) Actin fibers in WT and _dSesn_-null hearts were visualized by phalloidin staining (red).

Heart-specific depletion of dSesn caused cardiac malfunction similar to that seen in _dSesn_-null mutants (fig. S17, A and B; movies S5 and S6). Heart-specific depletion of AMPK also caused cardiac malfunction, but this was not alleviated by AICAR administration (fig. S17, C to E; movie S7), supporting the notion that dSesn maintains normal heart physiology through AMPK activation.

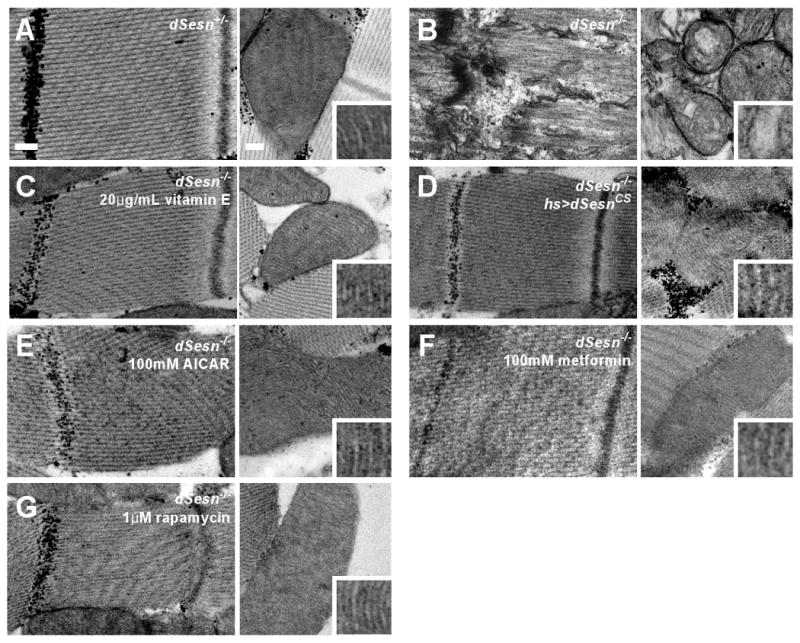

Skeletal muscle degeneration and mitochondrial dysfunction caused by loss of dSesn

dSesn mRNA and protein are abundant in the adult thorax (fig. S18), which is mostly composed of skeletal muscle. mSesn1 is also highly expressed in skeletal muscle (10). We therefore tested whether dSesn has a role in maintaining muscle homeostasis. 20-day-old _dSesn_-null flies showed degeneration of thoracic muscles with loss of sarcomeric structure, including discontinued Z discs, disappearance of M bands, scrambled actomyosin arrays, and diffused sarcomere boundaries (Fig. 6, A and B; fig. S19, A to H). Such defects are only partially observed in very old WT flies (∼90 days) (22), and were not found in young (5-day-old) _dSesn_-null muscles (fig. S19, I to L). Thus, the _dSesn_-null skeletal muscle appears to undergo accelerated aged-related degeneration.

Fig. 6.

Effect of dSesn on progressive muscle degeneration. Thoracic skeletal muscles of indicated 20-day-old male flies treated without or with indicated drugs were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Left panels: sarcomeres; right panels: mitochondria. Mitochondrial microstructure is shown in the insets (0.15 μm width). Scale bars, 0.2 μm.

Despite its normal appearance, muscle from 5-day-old _dSesn_-null flies exhibited mitochondrial abnormalities, including a rounded shape, occasional enlargement, and disorganization of cristae (fig. S19, I to L), which were also observed in 20-day-old mutants (fig. S19, E to H). Mitochondrial dysfunction can result in excessive generation of ROS leading to other abnormalities (23). Indeed, _dSesn_-null muscles exhibited increased accumulation of ROS, revealed by more intense DHE fluorescence and reduced _cis_-aconitase activity (fig. S20, A and B), which was associated with muscle cell death (fig. S20C). Furthermore, the muscle defects were prevented by vitamin E feeding (Fig. 6C), underscoring the role of ROS in muscle degeneration.

Expression of exogenous dSesnCS, devoid of redox activity (11), prevented muscle degeneration (Fig. 6D), suggesting again that regulation of AMPK-TOR by dSesn, rather than intrinsic redox activity, is of importance. Indeed, feeding animals with AMPK activators prevented muscle degeneration in _dSesn_-null mutants (Fig. 6, E and F), and depletion of AMPK in skeletal muscles caused severe degeneration of mitochondrial and sarcomeric structures (Fig. S21, E to H). Treatment of animals with rapamycin also prevented muscle degeneration in _dSesn_-null flies (Fig. 6G). Thus, dSesn-dependent control of AMPK-TOR signaling is essential for prevention of mitochondrial dysfunction and maintenance of muscle homeostasis during aging.

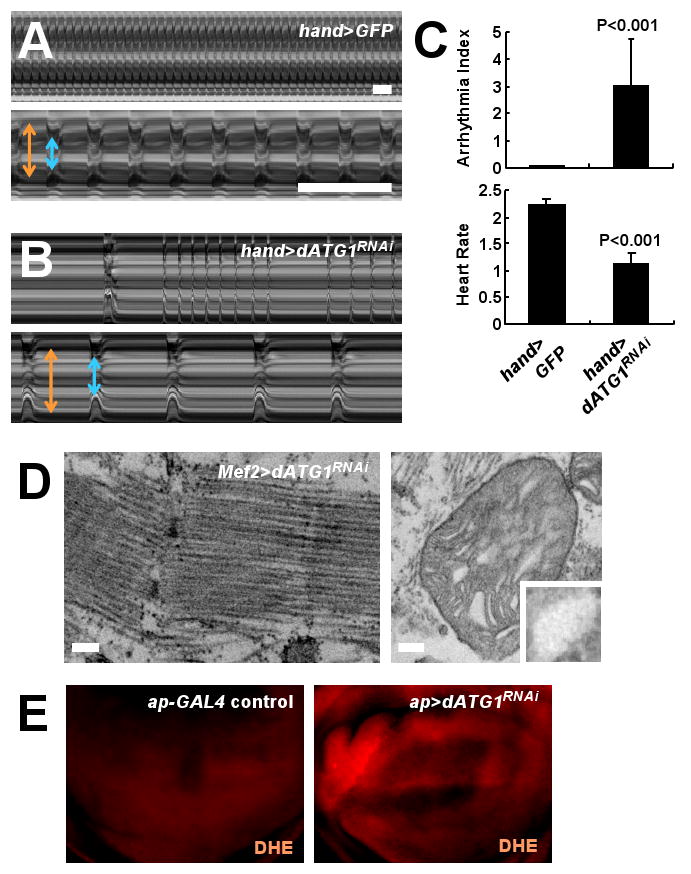

Inhibition of autophagy phenocopies dSesn loss-of-function

We noticed that _dSesn_-null muscles accumulated polyubiquitin aggregates (fig. S20D), which are hallmarks of defective autophagy (24). To test whether decreased autophagy brought about by excessive and prolonged TOR activity (23) might cause muscle degeneration, we silenced expression of ATG1, an essential component of the autophagic machinery, which is inhibited by TOR (1, 6). This caused a decline in cardiac performance (Fig. 7, A to C; movie S8), and degeneration and mitochondrial abnormalities in skeletal muscle (Fig. 7D; fig. S21, I to L). These results suggest that TOR upregulation caused by dSesn loss inhibits autophagy needed to eliminate ROS-producing dysfunctional mitochondria (25), which may contribute to muscle degeneration. Consistent with this view, ATG1 silencing resulted in ROS accumulation in wing discs (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7.

Phenotypes caused by silencing of dATG1. (A and B) Representative M mode records of control and _dATG1RNAi_-expressing hearts from 2-week-old adult flies, showing the movement of heart tube walls (y-axis) over time (x-axis). Diastolic (orange) and systolic (blue) diameters are indicated. 1 second is indicated as a bar. (C) Quantification of cardiac function parameters. P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA. Error bars indicate S.E.M.; n≥9. (D) _dATG1RNAi_-expressing thoracic skeletal muscle was analyzed by TEM. Left panel: sarcomeres; right panel: mitochondria. Mitochondrial microstructure is shown in the insets (0.15 μm width). Scale bars, 0.2 μm. (E) ROS accumulation (red) in response to dATG1RNAi expressed in dorsal (upwards) wing discs revealed by DHE staining.

Discussion

The results described above identify Sesn as a feedback regulator of TOR function. In mammalian cells increased expression of mSesns in response to genotoxic stress leads to inhibition of TOR activity through activation of AMPK (12). We now show that transcription of the dSesn gene is increased upon chronic TOR activation through JNK and FoxO in a manner dependent on ROS accumulation. Although transient InR activation inhibits FoxO through its phosphorylation by AKT (14), we find that chronic TOR activation overcomes this inhibition and results in nuclear translocation of FoxO, which increases dSesn transcription. In turn, dSesn suppresses metabolic dysfunction and age-related tissue degeneration brought about by hyperactivated TOR. Although dSesn can inhibit TOR-stimulated cell growth, our analysis points to its most important function being the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis and prevention of TOR-induced tissue degeneration. The three major functions of dSesn revealed by this study: suppression of lipid accumulation, prevention of cardiac malfunction and protection of muscle from age-related degeneration, are adversely affected by obesity, lack of exercise and aging, which make a disproportional contribution to health problems in developed and rapidly developing societies.

Whereas TOR controls cell growth mostly through inhibition of 4E-BP and activation of S6K kinase (1-3), its ability to induce dSesn expression depends on ROS accumulation, which our results suggest is a pathophysiological aberration caused by TOR hyperactivation that is normally antagonized by dSesn. However, the previously described redox function of Sesn (11) is not required for its protective role. TOR-induced accumulation of ROS was observed in yeast (26) and hematopoietic cells (27, 28), but the molecular mechanism underlying this phenomenon and its physiological and pathophysiological significance were unknown. Our results suggest that TOR-stimulated accumulation of ROS, which is needed for accumulation of dSesn, is independent of two of the major TOR targets, 4E-BP and S6K, and instead may result from TOR-mediated inhibition of physiological autophagy, a process that eliminates ROS-producing dysfunctional mitochondria (23). Nonetheless, inhibition of 4E-BP also contributes to the pro-aging effects of TOR by suppressing translation of several mitochondrial proteins (29) and by accelerating age-related cardiac malfunction at young ages (20), which is reminiscent of the observed cardiac defects seen in _dSesn_-null flies. Although TOR activates SREBP (17) and this may contribute to lipid accumulation in _dSesn_-null flies, autophagy promotes lipid elimination (30). Thus, decreased autophagy may also contribute to triglyceride accumulation. Hence, the different degenerative phenotypes exhibited by _dSesn_-null flies are due to the cumulative effects of several biochemical and cell biological defects caused by hyperactive TOR, including reduced autophagy and reduced function of 4E-BP. Both basal physiologic autophagy and 4E-BP function are enhanced by CR, which prevents aging-related pathologies (31). In the future, it will be of interest to determine the contribution of Sesn to these anti-aging effects.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Mcginnis (UCSD), M. Tatar (Brown Univ.), S. Oldham (Burnham Institute), U. Banerjee (UCLA), I.K. Hariharan (UC Berkeley), J. Brenman (UNC), O. Puig (Merck), C. Wilson (Oxford Univ.), L. Jones (Salk Institute), M. Miura (Univ. of Tokyo), DSHB (Iowa), DGRC (Indiana), DGRC (Japan), VDRC (Austria), Cell Signaling Inc., Santa Cruz Biotech. Inc., Bloomington and Harvard stock centers for fly strains, reagents and access to lab equipment. We acknowledge help from J. Kim, M. Yoon and R. Anderson in EM analysis, V. Temkin in ROS analysis, and M. Smelkinson, O. Cook and A. Guichard in histochemistry. We thank M. Kim for suggestions and constructive criticism. Work was supported by grants and fellowships from the NIH and Superfund Research Program (CA118165, ES006376 and P42-ES010337 to M.K., DK082080 to A.B., P41-RR004050 and P30-CA23100 to M.H.E.), KRF (KRF-2007-357-C00096 to J.H.L.), HFSPO (LT00653/2008-L to J.H.L), and NSERC (to E.J.P.). M.K. is an American Cancer Society Professor.

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. Cell. 2006;124:471. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oldham S, Hafen E. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:79. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Towler MC, Hardie DG. Circ Res. 2007;100:328. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000256090.42690.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porstmann T, et al. Cell Metab. 2008;8:224. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan EY. Sci Signal. 2009;2:pe51. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.284pe51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison DE, et al. Nature. 2009;460:392. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapahi P, Zid B. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2004;2004:PE34. doi: 10.1126/sageke.2004.36.pe34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Budanov AV, et al. Oncogene. 2002;21:6017. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Velasco-Miguel S, et al. Oncogene. 1999;18:127. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budanov AV, Sablina AA, Feinstein E, Koonin EV, Chumakov PM. Science. 2004;304:596. doi: 10.1126/science.1095569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budanov AV, Karin M. Cell. 2008;134:451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owusu-Ansah E, Yavari A, Mandal S, Banerjee U. Nat Genet. 2008;40:356. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greer EL, Brunet A. Oncogene. 2005;24:7410. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harvey KF, et al. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehtinen MK, et al. Cell. 2006;125:987. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobrosotskaya IY, Seegmiller AC, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Rawson RB. Science. 2002;296:879. doi: 10.1126/science.1071124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wessells RJ, Fitzgerald E, Cypser JR, Tatar M, Bodmer R. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1275. doi: 10.1038/ng1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luong N, et al. Cell Metab. 2006;4:133. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wessells R, et al. Aging Cell. 2009;8:542. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ocorr K, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609278104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi A, Philpott DE, Miquel J. J Gerontol. 1970;25:222. doi: 10.1093/geronj/25.3.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yen WL, Klionsky DJ. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:248. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00013.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hara T, et al. Nature. 2006;441:885. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, et al. Autophagy. 2007;3:337. doi: 10.4161/auto.4127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonawitz ND, Chatenay-Lapointe M, Pan Y, Shadel GS. Cell Metab. 2007;5:265. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen C, et al. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2397. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JH, et al. Blood. 2005;105:1717. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zid BM, et al. Cell. 2009;139:149. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh R, et al. Nature. 2009;458:1131. doi: 10.1038/nature07976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colman RJ, et al. Science. 2009;325:201. doi: 10.1126/science.1173635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information