Fundamental limits on the suppression of molecular fluctuations (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 Mar 9.

Published in final edited form as: Nature. 2010 Sep 9;467(7312):174–178. doi: 10.1038/nature09333

Abstract

Negative feedback is common in biological processes and can increase a system’s stability to internal and external perturbations. But at the molecular level, control loops always involve signaling steps with finite rates for random births and deaths of individual molecules. By developing mathematical tools that merge control and information theory with physical chemistry we show that seemingly mild constraints on these rates place severe limits on the ability to suppress molecular fluctuations. Specifically, the minimum standard deviation in abundances decreases with the quartic root of the number of signaling events, making it extraordinarily expensive to increase accuracy. Our results are formulated in terms of experimental observables, and existing data show that cells use brute force when noise suppression is essential, e.g. transcribing regulatory genes 10,000s of times per cell cycle. The theory challenges conventional beliefs about biochemical accuracy and presents an approach to rigorously analyze poorly characterized biological systems.

Life in the cell is a complex battle between randomizing and correcting statistical forces: births and deaths of individual molecules create spontaneous fluctuations in abundances1,2,3,4 – noise – while many control circuits have evolved to eliminate, tolerate or exploit the noise5,6,7,8. The net outcome is difficult to predict because each control circuit in turn consists of probabilistic chemical reactions. For example, negative feedback loops can compensate for changes in abundances by adjusting the rates of synthesis or degradation7, but such adjustments are only certain to suppress noise if the individual deviations immediately and surely affect the rates5. Even the simplest transcriptional autorepression by contrast involves gene activation, transcription and translation, introducing intermediate probabilistic events that can randomize or destabilize control. Negative feedback may thus either suppress or amplify fluctuations depending on the exact mechanisms, reaction steps and parameters9 – details that are difficult to characterize at the single cell level and that differ greatly from system to system. This raises a fundamental question: to what extent is biological noise inevitable and to what extent can it be controlled? Could evolution simply favor networks – however elaborate or ingeniously designed – that enable cells to homeostatically suppress any disadvantageous noise, or does the nature of the mechanisms impose inherent constraints that cannot be overcome?

Control is limited by information loss

To address this question without oversimplifying or guessing at the complexity of cells, we consider a chemical species X1 that affects the production of a second species X2, which in turn indirectly controls the production of X1 via an arbitrarily complicated reaction network with any number of components, nonlinear reaction rates, or spatial effects (Fig. 1). For generality, we only specify three of the chemical events of the larger network:

| x1→u(x2(−∞,t))x1+1(i)x1→x1/τ1x1−1(ii)x2→f(x1)x2+1(iii) | (1) |

|---|

where _x_1 and _x_2 are numbers of molecules per cell, the birth and death rates are probabilistic reaction intensities, _τ_1 is the average lifetime of X1 molecules, f is a specified rate function, and the unspecified control network allows u to be dynamically and arbitrarily set by the full time history of X2 values. Death events for X2 are omitted because the results we derive rigorously hold for all types and rates of X2 degradation mechanisms, as long as they do not depend on X1. The generality of u and f allows X1 to represent many different biological species: an mRNA with X2 as the corresponding protein, a protein with X2 as either its own mRNA or an mRNA downstream in the control pathway, an enzyme with X2 as a product, or a self-replicating DNA with X2 as a replication control molecule.

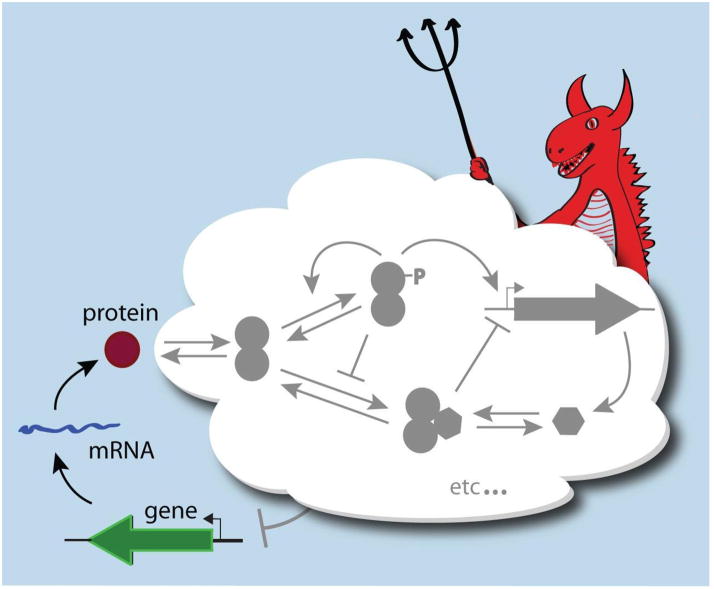

Figure 1. Schematic of optimal control networks and information loss.

Biological networks can be overwhelmingly complex, with numerous feedback loops and signaling steps. Predictions about noise then rely on quantitative estimates for how every probabilistic reaction rate responds to every type of perturbation. To investigate bounds on behavior, most of the network is here replaced by a ‘control demon’ representing a controller that is optimized over all possible network topologies, rates and mechanisms. The bounds are then calculated in terms of the few specified features.

The arbitrary birth rate u represents a hypothetical ‘control demon’ that knows everything about past and present values of _x_2 and uses this information to minimize the variance in _x_1. This corresponds to an optimal reaction network capable of any type of time-integration, frequency-based control, spatially extended dynamics, or other exotic actions. The sole restriction is that the control system depends on _x_1 only via reaction (iii), an example of a common chemical signaling relay where a concentration determines a rate. Because individual X2 birth events are probabilistic, some information about X1 is then inevitably and irrecoverably lost and the current value of X1 cannot be perfectly inferred from the X2 time-series. Specifically, the number of X2 birth events in a short time period is on average proportional to f(_x_1), with a statistical uncertainty that depends on the average number of events. If _x_1 remained constant, the uncertainty could be arbitrarily reduced by integrating over a longer time, but because it keeps changing randomly on a time scale set by _τ_1, integration can only help so much. The problem is thus equivalent to determining the strength of a weak light source by counting photons: each photon emission is probabilistic, and if the light waxes and wanes, counts from the past carry little information about the current strength. The otherwise omniscient control demon thus cannot know the exact state of the component it is trying to control.

We then quantify how finite signaling rates restrict noise suppression, without linearizing or otherwise approximating the control systems, by analytically deriving a feedback-invariant upper limit on the mutual information10 between X1 and X2 – an information-theoretic entropic measure for how much knowing one variable reduces uncertainty about another – and derive lower bounds on variances in terms of this limit. We use a continuous stochastic differential equation for the dynamics of species X1, an approximation that makes it easier to extend the results to more contexts and processes, but keep the signaling and control processes discrete. After considerable dust has settled, this theory (summarized in Box 1 and detailed in the Supplementary Information, SI) allows us to calculate fundamental lower bounds on variances.

Box 1.

Outline of underlying theory

Statistical uncertainties and dependencies are often measured by variances and correlation coefficients, but both uncertainty and dependence can also be defined purely in terms of probabilities (pi), without considering the actual states of the system. The Shannon entropy H (X) = Σ_pi_log_pi_ measures inherent uncertainty rather than how different the outcomes are, and the mutual information between random variables I (_X_1; _X_2) = H (X_1)–_H (_X_1|_X_2) measures how much knowing one variable reduces entropic uncertainty in another, regardless of how their outcomes may correlate10,27. Despite the fundamental differences between these measures, however, there are several points of contact that can be used to predict limits on stochastic behavior.

First, because imperfectly estimating the state of a system fundamentally restricts the ability to control it (SI), there is a hard bound on variances whenever there is incomplete mutual information between the signal _X_2 and the controlled variable _X_1. We quantify the bound by means of Pinsker’s nonanticipatory epsilon entropy28, a rarely utilized information-theoretic concept that exploits the fact that the transmission of information in a feedback system must occur in real time. This shows (SI) how an upper bound on the mutual information I (_X_1; _X_2) – i.e. a limited Shannon capacity in the channel from _X_1 to _X_2 – imposes a lower bound on the mean squared estimation error E (_X_1_X̂_1)2, where the ‘estimator’ _X̂_1 is an arbitrary function of the discrete signal _X_2 time series and the _X_1 dynamics at equilibrium is described by a stochastic differential equation. Since the capacity of the molecular channels we consider is not increased by feedback, this results in a lower limit in the variance of _X_1, in terms of the channel capacity C, that holds for arbitrary feedback control laws: σ12/〈x1〉≥(1+Cτ1)−1.

Second, the Shannon capacity is potentially unlimited when information is sent over point process ‘Poisson channels’29, x2→fx2+1, as in stochastic reaction networks where a controlled variable affects the rate of a probabilistic signaling event. However, infinite capacity requires that the rate f (_x_1) is unrestricted and thus that _X_1 is unrestricted – contrary to the purpose of control. Here we consider two types of restrictions. First, if the rate has an upper limit _f_max it follows30 that _C_=K<_f_> where _K_= log(_f_max/<_f_>). The channel capacity then equals the average intensity multiplied by the natural logarithm of the effective dynamic range _f_max/<_f_>, and the noise bound follows σ12/〈x1〉2≥1/(N1(KN2+1)). This allows for any nonlinear function f (_x_1) but, for specific functions, restricting the variance in _x_1 can further reduce the capacity. For example, we analytically show that the capacity of the generic Poisson channel subject to mean and variance constraints follows C=〈f〉log(1+σf2/〈f〉2). Having less noise in _x_1will reduce the variance in f and thereby make it harder to transmit the information that is fundamentally required to reduce noise. Combining this expression for the channel capacity with the feedback limit above reveals hard limits beyond which no improvements can be made: any further reduction in the variance would require a higher mutual information, which is impossible to achieve without instead increasing the variance. When f is linear in _x_1 this produces the result in Eq. (2). Analogous calculations allow us to derive capacity and noise results when f is a Hill function, or for processes with bursts, extrinsic noise, parallel channels, and cascades (SI). Finite channel capacities are the only fundamental constraints considered here, so at infinite capacity perfect noise suppression is possible by construction.

Noise limited by 4th root of signal rate

When the rate of making X2 is proportional to X1, f =_αx_1, for example when X1 is a template or enzyme producing X2, the hard lower bound on the (squared) relative standard deviation created by the loss of information follows:

| σ12〈x1〉2≥1〈x1〉×21+1+4N2/N1≈{1/N1forN2<N11/N1N2forN2>N1 | (2) |

|---|

where <…> denotes population averages and _N_1 = <_u_>_τ_1 = <_x_1> and _N_2 = α<_x_1>_τ_1 are the numbers of birth events of X1 and X2 made on average during time _τ_1. Thus no control network can significantly reduce noise when the signal X2 is made less frequently than the controlled component. When the signal is made more frequently than the controlled component, the minimal relative standard deviation (square root of Eq. (2)) at most decreases with the quartic root of the number of signal birth events. Reducing the standard deviation of X1 10-fold thus requires that the signal X2 is made at least 10,000 times more frequently. This makes it hard to achieve high precision, and practically impossible to achieve extreme precision, even for the slowest changing X1 in the cell where the signals X2 may be faster in comparison.

Systems with nonlinear amplification before the infrequent signaling step are also subject to bounds. For arbitrary nonlinear encoding where f is an arbitrary functional of the whole _x_1 time history – corresponding to a second control demon between X1 and X2 – the quartic root limit turns into a type of square root limit (Box 1 and SI). However, gene regulatory functions typically saturate at full activation or leak at full repression, as the generalized Hill function f=v(K1+x1h)/(K2+x1h) with K_1<K_2. Here X1 may be an activator or repressor, and X2 an mRNA encoding either X1 or a downstream protein. Without linearizing _f_ or restricting the control demon, an extension of the methods above (SI) reveals similar quartic root bounds as in Eq. (2), with the difference that _N_2 is replaced by _γN_2_,_max where _γ_ is on the order of one in a wide range of biologically relevant parameters (SI), and _N_2_,_max= _vτ_1 = _N_2 _v_/<_f_>. Cells can then produce much fewer signal molecules without reducing the information transfer, depending on the maximal rate increase v/<_f_>, but the quartic root effect still strongly dampens the impact on the noise limit. If X2 is an mRNA, N_2,_max is also limited because transcription events tend to be relatively rare even for fully expressed genes.

Many biological systems show much greater fluctuations due to upstream sources of noise, or sudden ‘bursts’ of synthesis4,11,12. If X1 molecules are made or degraded in bursts (size b_1,_ averaged over births and deaths) there is much more noise to suppress, and if signal molecules X2 are produced in bursts (size _b_2) each independent burst only counts as a single signaling event in terms of the Shannon information transfer, and:

| σ12〈x1〉2≥b1〈x1〉×21+1+4N2/b2N1/b1 | (3) |

|---|

The effective average number of molecules or events is thus reduced by the size of the burst, which can increase the noise limits greatly in many biological systems. The effect of slower upstream fluctuations in turn depends on their time-scales, how they affect the system, and whether or not the control system can monitor the source of such noise directly. If noise in the X1 birth rate is extrinsic to X1 but not directly accessible by the controller, the predicted noise suppression limits can follow similar quartic root principles for both fast and slow extrinsic noise, while for intermediate time-scales the power-law is between 3/8 and ¼ (SI, and Fig 2).

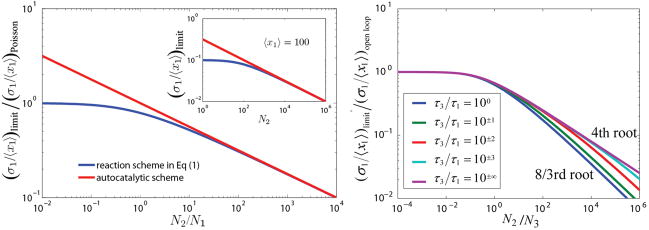

Figure 2. Hard limits on standard deviations.

(left) Intrinsic noise (Eq. (1)). The lower limit on the relative standard deviation normalized by that of a Poisson distribution, as a function of the ratio _N_2/_N_1. Blue curve corresponds to reaction scheme (1), and red to the autocatalytic scheme described above Eq. (5). The quartic root is the strongest relative response along either curve, while at low relative signaling frequencies the limit is an even more damped function of _N_2/_N_1. (Left, inset) The same lower limit for an average of 100 X1 molecules, as a function of _N_2. (Right) Extrinsic noise. X1 is made at rate x_3_u, where X3 is born with constant probability and decays exponentially with rate 1/_τ_3, while intrinsic birth and death noise in X1 is ignored. For _τ_3≪_τ_1 or _τ_3≫_τ_1, the quartic root asymptotic still applies, essentially because the process mimics a one-variable random process in both cases. At intermediate time-scales the _N_2 dependence is less strict and _τ_3=_τ_1 produces an asymptotic power law exponent of 3/8 rather than ¼, partly supporting previous6,16 conclusions that extrinsic noise is slightly easier to suppress. However, many actual control systems may find intermediately slow noise the hardest to eliminate and any predictions about suppressing extrinsic noise will depend on the properties of that noise. The predicted extrinsic noise limit is also a conservative estimate, and the actual magnitude of the noise limit may be slightly higher (SI).

Information losses in cascades

Signaling in the cell typically involves numerous components that change in probabilistic events with finite rates. Information about upstream states is then progressively lost at each step much like a game of ‘broken telephone’ where messages are imperfectly whispered from person to person. If each signaling component X_i_+1 decays exponentially and is produced at rate αixi, an extension of the theory (SI) shows that if a control demon monitors X_n_+1 and controls X1, _N_2 above is replaced by

where Nj is the average number of birth events (or bursts, as in Eq. (3)) of species j during time period _τ_1. Information transfer in cascades is thus limited by the components made in the lowest numbers, and because the total average number of birth events over the n steps obeys Ntot_≥_n_2_Neff, a five-step linear cascade requires at least 25 times more birth events to maintain the same capacity to suppress noise as a single-step mechanism. This effect of information loss is superficially similar to noise propagation where variation in inputs cause variation in outputs, but though both effects reflect the probabilistic nature of infrequent reactions, the governing principles are very different. In fact, the mechanisms for preventing noise propagation – such as time-averaging or kinetic robustness to upstream changes6 – cause a greater loss of information, while mechanisms that minimize information losses – such as all-or-nothing nonlinear effects13 – instead amplify noise. Large variation in signaling intermediates is thus not necessarily a sign of reduced precision but could reflect strategies to minimize information loss, which in turn allows tighter control of downstream components.

The rapid loss of information in cascades also suggests another trade-off: effective control requires a combination of appropriately nonlinear responses and small information losses, but nonlinear amplification in turn requires multiple chemical reactions with a loss of information at each step. The actual bounds may thus be much more restrictive than predicted above, where assuming Hill functions or arbitrary control networks conceals this trade-off. One of the greatest challenges in the cell may be to generate appropriately nonlinear reaction rates without losing too much information along the way.

Parallel signal and control systems can instead improve noise suppression, since each signaling pathway contributes independent information about the upstream state. However, for a given total number of signaling events, parallel control cannot possibly reduce noise below the limits above: the loss of information is determined only by the total frequency of the signaling events, not their physical nature. The analyses above in fact implicitly allow for arbitrarily parallel control with f interpreted as the total rate of making control molecules affected directly by X1 (SI).

Systems selected for noise suppression

The results above paint a grim picture for suppression of molecular noise. At first glance this seems contradicted by a wealth of biological counterexamples: molecules are often present in low numbers, signaling cascades where one component affects the rates of another are ubiquitous, and yet many processes are extremely precise. How is this possible if the limits apply universally? First, the transmission of chemical information is not fundamentally limited by the number of molecules present at any given time, but by the number of chemical events integrated over the time-scale of control (i.e., by _N_2 rather than <_x_2> above). Second, most processes that have been studied quantitatively in single cells do in fact show large variation, and the anecdotal view of cells as microscopic-yet-precise largely comes from a few central processes where cells can afford a very high number of chemical events at each step, often using post-translational signaling cascades. Just like gravity places energetic and mechanistic constraints on flight but does not confine all organisms to the surface of the earth, the rapid loss of information in chemical networks places hard constraints on molecular control circuits but does not make any level of precision inherently impossible.

It can also be tempting to dismiss physical constraints simply because life seems fine despite them. For example, many cellular processes operate with a great deal of stochastic variation, and central pathways seem able to achieve sufficiently high precision. But such arguments are almost circular. The existence of flight does not make gravity irrelevant, nor do winged creatures simply fly sufficiently well. The challenges are instead to understand the trade-offs involved: what performances are selectively advantageous given the associated costs, and how small fitness differences are selectively relevant?

To illustrate the biological consequences of imperfect signaling we consider systems that must suppress noise for survival and must relay signals through gene expression, where chemical information is lost due to infrequent activation, transcription, and translation. The best characterized examples are the homeostatic copy number control mechanisms of bacterial plasmids that reduce the risk of plasmid loss at cell division. These have been described much like the example above with X1 as plasmids and X2 as plasmid-expressed inhibitors5, except that plasmids self-replicate with rate u(t)_x_1 and therefore are bound by the quartic root limit for all values of _N_1 and _N_2 (SI, Fig. 2). To identify the mechanistic constraints when X1 production is directly inhibited by X2, rather than by a control demon that is infinitely fast and that delivers the optimal response to every perturbation, we consider a closed toy model:

| x1→x1u(x2)x1+1x1→x1/τ1x1−1andx2→x1R2+(x2)x2+1x2→R2−(x2)x2−1. | (5) |

|---|

where X1 degradation is a proxy for partitioning at cell division, and the rate of making X2 is proportional to X1 because each plasmid copy encodes a gene for X2. We then use the logarithmic gains6,14 H_12 = −_∂_ln_u/_∂_ln_x_2 and H22=∂ln(R2−/R2+)/∂lnx2 to quantify the percentage responses in rates to percentage changes in levels without specifying the exact rate functions. Parameter _H_12 is similar to a Hill coefficient of inhibition, and _H_22 determines how X2 affects its own rates, increasing when it is negatively auto-regulated and decreasing when it is degraded by saturated enzymes. The ratio _H_12/_H_22 is thus a total gain, corresponding to the eventual percentage response in u to a percentage change in _x_1. With _τ_2 as the average lifetime of X2 molecules, stationary fluctuation-dissipation approximations6,15 (linearizing responses, SI) then give:

| σ12〈x1〉2=1〈x1〉×(H22H12+τ2τ1×1H22)︷NoisefromlowX1numbers+1〈x2〉×H12H22×τ2τ1︷NoisefromlowX2numbers≥2N1N2︷Lowerlimittototalnoise. | (6) |

|---|

where the limit holds for all Hij and τi (SI). This reflects a classic trade-off in control theory: higher total gain suppresses spontaneous fluctuations in X1 but amplifies the transmitted fluctuations from X2 to X1. Numerical analysis confirms that even a Hill-type inhibition function u can get close to the limit (not shown), and thus that direct inhibition can do almost as well as a control demon. However, the parameter requirements can be extreme: the signal molecules must be very short-lived, and the optimal gain (H12/H22)opt≈N2/N1 may be so high that introducing any delays or ‘extrinsic’ fluctuations6,16 would destabilize the dynamics. Regardless of the inhibition control network, plasmids thus need to express inhibitors at extraordinarily high rates, and generate strongly nonlinear feedback responses without introducing signaling cascades. Most plasmids indeed take these strategies to the extreme, for example transcribing control genes tens of thousands of times per cell cycle using several gene copies and some of the strongest promoters known. Some plasmids also eliminate many of the cascade steps inherent in gene expression, using small regulatory RNAs, and still create highly nonlinear responses using proofreading-type mechanisms (Fig. 3, left). Others partially avoid indirect control by ensuring that the plasmid copies themselves prevent each others’ replication (Fig. 3, right), or suppress noise without closing control loops17,18 by changing the Poisson nature of the X1 and X2 chemical events (Eq. (1)). Though such schemes may have limited effects on variances11, some plasmids seem to take advantage of them5.

Figure 3. Plasmid replication control.

(Left) Plasmid ColE1 expresses an inhibitor that prevents replication, similarly to the self-replication model in the main text with X1 as plasmid and X2 as inhibitor. Because plasmids are under selection for noise suppression the theory predicts it must maximize expression rates and minimize the length of signaling cascades while still achieving ‘cooperative’ nonlinear effects in the control loop. ColE1 indeed expresses a short-lived anti-sense RNA inhibitor (RNA I) tens of thousands of times per cell cycle (~10Hz), that directly and irreversibly blocks the maturation of a constitutively synthesized sense-RNA replication pre-primer (RNA II)5 – eliminating both the translation step and binding and unbinding to genes and making it energetically and mechanistically possible to produce inhibitors at such high rates. ColE1 could also create strongly nonlinear control kinetics by exploiting kinetic proofreading in RNA II elongation5,31. Many unrelated plasmids similarly express anti-sense inhibitors at high rates, avoid cascades, and use multistep inhibition kinetics. (Right) Plasmids such as P1, F, and pSC101 use ‘handcuffing’ mechanisms, where repeated DNA sequences (iterons) bind each other and prevent replication32. This can achieve similar homeostatic dynamics as monomer-dimer equilibria where a higher fraction of molecules are in dimer form at higher abundance. Using DNA itself as inhibitor this could eliminate the need for indirect signaling altogether, but because the mechanisms seem incapable of strongly nonlinear corrections32, most such plasmids use additional control systems that go through gene expression and thus are subject to information loss. Plasmids also commonly use counteracting loops, where replication inhibitors also auto-inhibit their own synthesis – a counter-intuitive strategy that in fact can improve control greatly (increasing _H_22 for a given high _H_21 in Eq. (4)).

Outlook

Several recent studies have generalized control-theoretic notions19,20 or applied them to biology21,22. Others have demonstrated physical limits on the accuracy of cellular signaling13,23,24,25, for example using fluctuation-dissipation approximations to predict estimation errors associated with a constant number of diffusing molecules hitting a biological sensor26. Interestingly, the latter show that the minimal relative error decreases with the square root of the number of events, regardless of detection mechanism. Some studies have also analyzed the information transfer capacity of open-loop molecular systems25, or extracted valuable insights from Gaussian small-noise approximations. Here we extend these works by developing exact mathematical methods for arbitrarily complex and nonlinear real-time feedback control of a dynamic process of noisy synthesis and degradation. In such systems, the minimal error decreases with the quartic root of the integer number of signaling events, making a decent job 16 times harder than a half-decent job. This perhaps explains why there is so much biochemical noise – correcting it would just be too costly – but also constrains other aspects of life in the cell. For example, the noise levels may increase or decrease along signaling cascades, depending on the kinetic details at each step, but information about upstream states is always progressively and irreversibly lost. Though it is tempting to believe that large reaction networks are capable of almost anything if the rates are suitably nonlinear, the opposite perspective may thus be more appropriate: having more steps where one component affects the rates of another creates more opportunities for losing information and fundamentally prevents more types of behaviors. While awaiting the detailed models that predict what single cells actually do – which require every probabilistic chemical step to be well characterized – fusing control and information theory with stochastic kinetics thus provides a useful starting point: predicting what cells cannot do.

Supplementary Material

1

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the BBSRC under grant BB/C008073/1, by the National Science Foundation Grants DMS-074876-0 and CAREER 0720056, and by grants GM081563-02 and GM068763-06 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author contributions The three authors (I.L., G.V., and J.P.) contributed equally, and all conceived the study, derived the equations, and wrote the paper.

Author information Reprints and permissions information is available at npg.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Ozbudak EM, Thattai M, Kurtser I, Grossman AD, van Oudenaarden A. Regulation of noise in the expression of a single gene. Nature Genetics. 2002;31:69–73. doi: 10.1038/ng869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elowitz MB, Levine AJ, Siggia ED, Swain PS. Stochastic gene expression in a single cell. Science (Washington, DC, United States) 2002;297:1183–1186. doi: 10.1126/science.1070919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman JR, et al. Single-cell proteomic analysis of S. cerevisiae reveals the architecture of biological noise. Nature. 2006;441:840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature04785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golding I, Paulsson J, Zawilski SM, Cox EC. Real-time kinetics of gene activity in individual bacteria. Cell (Cambridge, MA, United States) 2005;123:1025–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paulsson J, Ehrenberg M. Noise in a minimal regulatory network: Plasmid copy number control. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 2001;34:1–59. doi: 10.1017/s0033583501003663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paulsson J. Summing up the noise in gene networks. Nature (London, United Kingdom) 2004;427:415–418. doi: 10.1038/nature02257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dublanche Y, Michalodimitrakis K, Kuemmerer N, Foglierini M, Serrano L. Noise in transcription negative feedback loops: simulation and experimental analysis. Molecular Systems Biology. 2006:E1–E12. doi: 10.1038/msb4100081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barkai N, Shilo BZ. Variability and robustness in biomolecular systems. Mol Cell. 2007;28:755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maxwell J. On governors. Proc Royal Society of London. 1868;16:270–283. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cover TM, Thomas JA. Elements of Information Theory. 2. John Wiley & Sons, INC; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedraza JMPJ. Effects of molecular memory and bursting on fluctuations in gene expression. Science. 2008:339–343. doi: 10.1126/science.1144331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai L, Friedman N, Xie XS. Stochastic protein expression in individual cells at the single molecule level. Nature (London, United Kingdom) 2006;440:358–362. doi: 10.1038/nature04599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tkacik G, Callan CG, Jr, Bialek W. Information flow and optimization in transcriptional regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12265–12270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806077105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savageau MA. Parameter sensitivity as a criterion for evaluating and comparing the performance of biochemical systems. Nature (London, United Kingdom) 1971;229:542–544. doi: 10.1038/229542a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keizer J. Statistical Thermodynamics of Nonequilibrium Processes. Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh A, Hespanha JP. Optimal feedback strength for noise suppression in autoregulatory gene networks. Biophys J. 2009;96:4013–4023. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korobkova EA, Emonet T, Park H, Cluzel P. Hidden stochastic nature of a single bacterial motor. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:058105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.058105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doan T, Mendez A, Detwiler PB, Chen J, Rieke F. Multiple phosphorylation sites confer reproducibility of the rod’s single-photon responses. Science. 2006;313:530–533. doi: 10.1126/science.1126612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martins NC, Dahleh MA, Doyle JC. Fundamental Limitations of Disturbance Attenuation in the Presence of Side Information. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 2007;52:56–66. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martins NC, Dahleh MA. Feedback Control in the Presence of Noisy Channels: “Bode-Like” Fundamental Limitations of Performance. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 2008;52:1604–1615. [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Samad H, Kurata H, Doyle JC, Gross CA, Khammash M. Surviving heat shock: control strategies for robustness and performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2736–2741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403510102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yi TM, Huang Y, Simon MI, Doyle J. Robust perfect adaptation in bacterial chemotaxis through integral feedback control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4649–4653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bialek W, Setayeshgar S. Cooperativity, sensitivity, and noise in biochemical signaling. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;100:258101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.258101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregor T, Tank DW, Wieschaus EF, Bialek W. Probing the limits to positional information. Cell. 2007;130:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walczak AM, Mugler A, Wiggins CH. A stochastic spectral analysis of transcriptional regulatory cascades. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6529–6534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811999106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bialek W, Setayeshgar S. Physical limits to biochemical signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10040–10045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504321102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shannon CE. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell System Technical Journal. 1948;27:379–423. 623–656. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorbunov AK, Pinsker MS. Nonanticipatory and prognostic epsilon entropies and message generation rates. Problems of Information Transmission. 1973;9:184–191. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kabanov Y. The capacity of a channel of the Poisson type. Theory of Probability and its Applications. 1978;23:143–147. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis MHA. Capacity and cut-off rate for Poisson type channels. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 1978;26:710–715. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomizawa J. Control of ColE1 plasmid replication: binding of RNA I to RNA II and inhibition of primer formation. Cell (Cambridge, MA, United States) 1986;47:89–97. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das N, et al. Multiple homeostatic mechanisms in the control of P1 plasmid replication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:2856–2861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409790102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1