Getting in touch with the clathrin terminal domain (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2013 Apr 1.

Abstract

The N-terminal domain (TD) of the clathrin heavy chain is folded into a seven-bladed β-propeller that projects inward from the polyhedral outer clathrin coat. As the most membrane-proximal portion of assembled clathrin, the TD is a major protein–protein interaction node. Contact with the TD β-propeller occurs through short peptide sequences typically located within intrinsically disordered segments of coat components that usually are elements of the membrane-apposed, inner ‘adaptor’ coat layer. A huge variation in TD binding motifs is known and now four spatially discrete interaction surfaces upon the β-propeller have been delineated. An important operational feature of the TD interaction sites in vivo is functional redundancy. The recent discovery that ‘pitstop’ chemical inhibitors apparently occupy only one of the four TD interactions surfaces, but potently block clathrin-mediated endocytosis, warrants careful consideration of the underlying molecular basis for this inhibition.

Keywords: Clathrin-mediated endocytosis, heavy chain, terminal domain, interaction surface, β-propeller, S. cerevisiae, mutant alleles, small molecule chemical inhibitors, invagination, receptor

Coat dependent vesicular trafficking is an evolutionarily conserved feature of eukaryotic cells. During normal cell operation, small, membrane-bound transport intermediates constantly ferry integral membrane proteins, lipids and other soluble macromolecules between relatively long-lived intracellular organelles. As the different donor compartments in these transport reactions retain their biological identity and function, coat-mediated sorting is, of necessity, cargo selective. The task of determining the precise set of cargo packaged into coated vesicles is typically performed by so-called adaptors, which constitute an inner layer of the assembled proteinaceous coat encasing the cytosolic face of a membrane bud. The outer layer is a typically a stiff geometric molecular scaffold that surrounds the vesicle during membrane deformation and scission and functions integrally with the inner adaptor layer (1).

The clathrin coat

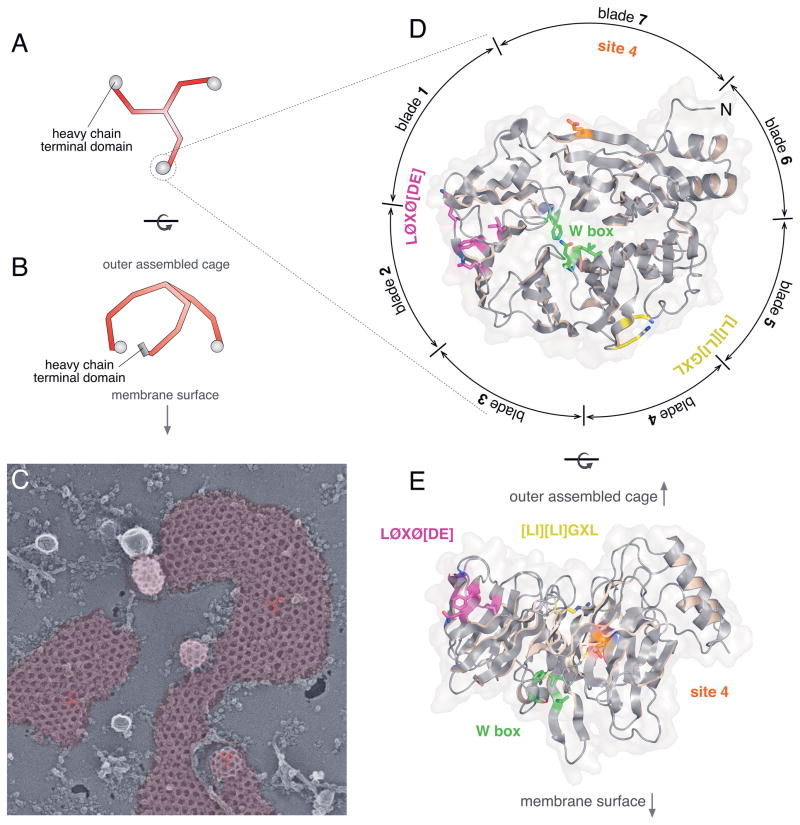

Of the various transport carriers (2, 3), probably the best understood are clathrin-coated vesicles, which can form at several distinct membrane locations within the cell (4–7). The three-fold symmetry and inherent sidedness of the clathrin protomer, termed the triskelion (8), underpins the formation of a regular outer polyhedral lattice upon interdigitation (9) (Figure 1). The coats that assemble on the _trans_-Golgi network (TGN), at the plasma membrane and on endosomes all come from a single reservoir of soluble clathrin. This means that compartment-specific adaptors must recruit clathrin to different sites of action, and that these proteins likely share a similar mode of engaging clathrin to drive assembly of the polyhedral coat. The major adaptors in TGN- and cell surface-derived clathrin-coated vesicles are termed AP-1 and AP-2, respectively (5). Both are heterotetramers with a shared overall organization. The ~100-kDa β chains of AP-1 (designated β1) and AP-2 (β2) are ~85% identical and represent the primary clathrin binding subunit (10, 11). Limited proteolysis shows the C-terminal hinge and appendage domains of β1 and β2 are required for clathrin binding (12, 13). A conserved, leucine rich, linear sequence tract within the unstructured β2 subunit hinge binds to clathrin directly (14). Another class of clathrin-associated sorting proteins (CLASPs), the β-arrestins, mesh activated G protein-coupled receptors with endocytic clathrin coats (15, 16). The β-arrestins also have a leucine-containing linear sequence, very similar to the β1/2 hinge sequence, that associates with clathrin (17). The reciprocal binding site on clathrin is the globular ‘terminal domain’ (TD) at the N-terminus of the clathrin heavy chain (HC) (18). Structurally, the TD is folded into a seven-bladed β-propeller (19) and this represents the region of the outer triskelion positioned closest to the membrane surface in the assembled coat (20) (Figure 1). The β-arrestin sequence engages the first 100 residues of the clathrin HC (18), which correspond to the first two blades of the βpropeller (19, 21). Generalization of these results defined the adaptor ‘clathrin box’ consensus: LØXØ[DE] (single letter amino acid code where Ø represents a hydrophobic residue and alternative residues are bracketed) (21, 22), but it soon became apparent that there are other sequence variants that bind to the TD as avidly (Table 1).

Figure 1. Clathrin structure and function.

A. Stylized cartoon depiction of the clathrin triskelion viewed from the ventral surface. The TD at the N-terminal end of each heavy chain (red) is indicated (gray), while the C-terminal end of each heavy chain is involved in trimerization.

B. More accurate schematic representation of the lateral view of a clathrin triskelion based on the high-resolution cryoelectron microscopy structure of the assembled cage (63). The arrow indicates the defined sidedness of the assembled trimer.

C. Rapid-freeze deep-etch image of assembled clathrin lattice on the glass-adherent ventral surface of a cultured HeLa cell. In these cells, the clathrin polymer (pseudocolored purple) ranges from large expanses of planar assemblies with a preponderance of hexagonal units through adjacent, pentagon-containing hemispherical-shaped buds, to deeply invaginated structures just about to be released from the plasma membrane as clathrin-coated vesicles. The relative positioning of several individual triskelia (red) interdigitated within the assembled lattice is shown.

D. Ribbon diagram of the human clathrin TD (PDB code 2XZG (40)) viewed from the membrane-proximal surface of the β-propeller. The positioning of the seven β-stranded blades is indicated as well as the relative locations of the TD interaction surfaces. Rendered in stick representation are some important side chains (with oxygen in red and nitrogen in blue) defining each binding site (Ile80, Gln89, Phe91 and Lys96 for the clathrin-box LØXØ [DE] site 1/purple; Phe27, Gln152, Ile154 and Ile170 for the W-box site 2/green; Arg188 and Gln192 for the [LI][LI]GXL site 3/yellow; Glu11 for site 4/orange). Note the circumferential positioning of the LØXØ [DE], [LI][LI]GXL and site 4 interaction surfaces.

E. Ribbon diagram of the TD β-propeller rotated ~90° to illustrate a lateral view. Color-coded as in D with the relative sidedness (arrows) shown.

Table 1.

The clathrin-binding motifs.

| adaptor motif | clathrin HC location1 | key clathrin HC residues1 | examples | sequence motif | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD site 1: clathrin-box motif | LØXØ[DE] | TD groove between blades 1 & 2 | Ile80Thr87Gln89Phe91Lys96Lys98 | amphiphysinβ-arrestin 1AP-2 β2 subunit_S.c_.2 Ent1/2p_S.c_. Yap1802p_S.c_. Apl2p (AP-1 β1) | LLDLDLIEFELLNLDLIDL*4LIDM*LLDLD |

| TD site 2: W-box motif | PWXXW | top of β-propeller | Phe27Gln152Ile154Ile170 | amphiphysinSNX9 | PWDLWPWSAW |

| TD site 3: β-arrestin 1L site | [LI][LI]GXL | TD groove between blades 4 & 5 | R188Q192 | β-arrestin 1LAP-2 β2 subunit | LLGDLLLGDL |

| TD site 4 | unknown | TD exposed surface of blade 7 | Glu11 | unknown | not available |

| ankle | unknown non linear? | CHC1R1/2 | Cys682Gly710 | GGA1 | Thr613 +Asn622 |

In S. cerevisiae clathrin-dependent vesicle transport in the TGN–endosomal system and during endocytic uptake, which takes place at cortical actin patches, share many mechanistic features and orthologous components with those in metazoa (23–25). In several yeast clathrin adaptors the C-terminal carboxylate of a truncated clathrin box substitutes for the distal acidic side chain (26) (Table 1). In vertebrate amphiphysin one standard clathrin box is trailed closely by another sequence, PWDLW, that independently binds to the TD (27–29) at a site distinct from the clathrin box, the so-called W-box site (30). There are now well over thirty endocytic proteins that bind physically to clathrin, but not all of the interaction motifs have been precisely mapped. Nevertheless, a multiplicity of proteins clearly converges on the TD, so it is critical to understand how these binding events are involved in clathrin assembly and coated vesicle function in vivo.

Additional adaptor binding sites on the TD

Collette et al. provided the first study to directly examine the importance of these interactions in vivo by testing whether the known binding sites on the TD are required for clathrin function in budding yeast (31). The yeast TD W-box and clathrin-box sites, which are fully conserved with the human HC, were mutated together to F26W and I79S + Q89M, respectively, and this mutant (chc1-box) was then expressed in yeast as the sole source of clathrin HC. It was expected that these mutations in the HC would cause extensive perturbation of clathrin function by disrupting the binding of multiple adaptors. Surprisingly, the TD mutant cells are essentially wild type for all phenotypic tests performed, including growth and several trafficking assays monitoring endocytosis and TGN/endosomal sorting (31). Moreover, recruitment of clathrin to membranes is still efficient, and clathrin-coated vesicles can be purified from chc1-box cells, but AP-1 is prominently absent from the clathrin-coated vesicle fractions. Although two-hybrid interaction of several adaptors with the mutant TD is ablated, the epsin Ent2p, which has a C-terminal clathrin-box motif, retains some residual binding to the mutant yeast TD (31). Collectively these functional data suggested that there must be alternative sites on the clathrin HC mediating adaptor binding and clathrin membrane recruitment necessary for vesicle transport.

Shortly after the yeast mutant studies were reported, a third binding site on the mammalian clathrin TD was, in fact, identified through the analysis of a splicing variant of β-arrestin 1 (alternatively termed arrestin2) (32). This longer variant contains an 8 amino-acid insertion with the sequence LLGDLASS (33). Using live cell imaging of GFP-tagged β-arrestins, Kang et al. discovered that the long form of β-arrestin 1 (designated arrestin2L) redistributes more efficiently than the short form (arrestin2S) to clathrin-coated pits upon agonist induction of β-adrenergic receptors (32). Moreover, an arrestin2L with the LIELD clathrin-box motif deleted (arrestin2L- LIELD-GFP) still redistributes to clathrin-coated regions upon agonist treatment, while the recruitment of arrestin2S- LIELD-GFP is extremely impaired. The arrestin2L- LIELD is also more efficient at promoting receptor internalization than the comparable short form (32). Consistent with this, the binding affinity of arrestin2L for the clathrin TD is greater than that of arrestin2S. Buoyed by these findings Kang et al. went on to obtain crystal structures of the full length β-arrestins bound to the clathrin TD (32). Both the long and short forms of β-arrestin 1 engage the binding site between blades 1 and 2 of the TD β-propeller using the LIELD clathrin-box motif, as expected (18, 21). However, in the arrestin2L–TD co-crystal, the 8 amino-acid arrestin2L splice loop binds to a shallow hydrophobic groove between TD blades 4 and 5 (32) (Figure 1D), a site originally speculated to be a possible additional interaction surface (21). Mutational analysis and binding assays define the consensus peptide interaction motif for this third TD site as [LI][LI]GXL (32) but, alone this short peptide motif does not appear to bind to the TD detectably. Still, of interest, several other clathrin adaptors contain this motif (including the β subunits of AP-1 and AP-2) but to date the general importance these [LI][LI]GXL sequences on binding to the TD or collection into clathrin-coated structures has not been examined. Also, all of the key side chains required for [LI][LI]GXL binding on blade 4 are perfectly conserved in the yeast TD, and of the five residues important on blade 5, two are identical and two conservatively substituted. Thus this surface is likely active in S. cerevisiae Chc1p as well.

A full complement of TD contacts

In a recent report in Traffic, Willox and Royle systematically revisit the role of these three clathrin HC TD binding sites (34). Using RNA interference (RNAi) knockdown of the endogenous clathrin HC and synchronous reconstitution with RNAi-resistant HC cDNAs in human cells, they monitored the endocytosis of transferrin, as well as the recruitment of GFP-HC constructs to cell membranes. Remarkably, a clathrin HC mutant where all three TD binding sites are ablated gives substantial rescue of transferrin internalization, while cells expressing a complete TD deletion ( 1–330) are defective. Also the triple mutant HC is recruited to surface puncta containing transferrin, as well as to the perinuclear TGN/endosomal region of the cell (34). The critical implication of these findings is that other adaptor binding sites on the TD must exist.

Since the yeast TD could not substitute for the human TD in their system, despite conservation of just about all the key residues in the known TD binding sites, Willox and Royle generated a set of yeast–human TD chimeras to help identify alternative TD binding site(s) (34). Using this strategy they mapped a new binding site to the first 100 amino acids of the clathrin HC, which also contains the clathrin-box binding site. Conservation-based in silico modeling predictions and further mutagenesis steered them to a surface exposed site on blade 7 of the β-propeller near amino acid Glu11 (the first β strand located at the N-terminus of the TD actually closes the folded propeller by being incorporated as the outer strand of blade 7 (19, 34); Figure 1). Only upon mutation at this fourth site (E11K) in combination with the other three TD binding site mutations is endocytosis ablated. The quadruple mutant cells also have fewer clathrin-containing puncta and brighter dispersed cytosolic fluorescence, so proper translocation of the TD-mutated clathrin onto membranes is defective (34). Missing was biochemical validation (using circular dichroism, for example) of the proper folding of the various TD mutants but, remarkably, the authors further show that any single binding site in the absence of the others can effectively restore internalization. That is, the four sites exhibit functional redundancy (34). Still, there may be subtle functional or cargo-specific differences between the various combination mutants, but more detailed analyses, including examination of the dynamics of clathrin coat formation through total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy, will be needed to uncover such distinctions.

Willox and Royle astutely note that the spatial distribution of the three circumferential TD binding sites, splayed about 120° apart, with the W-box site make maximal use of the available TD surface (34) (Figure 1). In this regard, it is worth pointing out that both coat protein complex I (COPI) and COPII have similar integral seven-bladed β-propeller units in the outer coat layer and that extensive interactions are established with both the top surface and the outer rims of the circumferential propeller exterior in both assembled coats (3, 35–37). And within the βpropeller-containing superfamily of proteins that execute a diverse array of biologic functions, many different surfaces of the thick disc-like fold are used (38). In a similar fashion, the clathrin TD utilizes the broad exposed surface of the β-propeller to contact multiple components of the inner layer of the coat. Some obvious advantages of an array of four separate sites are to prevent competition between clathrin TD binding proteins and to provide the flexibility to accommodate different interaction motifs and relative orientations of binding partners.

Chemical inhibition

Since the TD represents the major clathrin interaction node (39), it is an appealing potential target for chemical inhibitor screens. In fact, there are no facile, selective pharmacological tools available to precisely interfere with clathrin-mediated trafficking only. The discovery of two TD binding ‘pitstop’ inhibitors (40) is therefore an important step forward. Cell permeable pitstop 2 has strong inhibitory action on endocytosis; the inhibitor diminishes by >90% the uptake of transferrin, epidermal growth factor and human immunodeficiency virus-1, but not Shiga toxin (40). The internalization of the latter toxin is clathrin independent (41). And because endocytosis plays an important role in dampening the relay of cellular signals (42, 43) and in pathogen entry (44), these compounds may even be therapeutically relevant.

The pitstops were identified because in vitro they efficiently obstruct the soluble clathrin TD from associating with the clathrin-binding region of amphiphysin, as well as with three other endocytic accessory factors (40). Co-crystallography reveals that both pitstop 1 and pitstop 2 occlude the clathrin-box site between blades 1 and 2 of the TD β-propeller (40). The two chemically different heterocyclic inhibitors occupy the same molecular surface of the TD–but roughly orthogonal to one another (40). This is consistent with the different orientations of three key TD side chains (Arg64, Gln89 and Phe91) when either pitstop 1 or 2 is bound. The current X-ray crystallographic data thus show that pitstops occupy only one contact surface on the TD—the clathrin box site (Figure 1).

Yet, because any one of the four TD binding sites appears sufficient for transferrin internalization (34), it seems remarkable that pitstop 1 and 2 block clathrin-mediated endocytosis so effectively (40). How can this be rationalized with the structural and functional results outlined above? One possibility is that by binding to the diagonal groove between blades 1 and 2, a general allosteric change propagates inaccessibility to the three other contact sites on the molecular surface of the TD but this is not supported by the existing structural data. The TD βpropeller is folded as a rigid body and no substantial conformational shift in the α-carbon backbone positioning in the apo form (19) or when liganded (21, 30, 32, 40) is evident.

A feature of many of the TD-binding sequences is alternating hydrophobic (leucine or phenylalanine predominantly) and acidic side chains (Table 1). If only a single operative TD surface is permissive for (transferrin) internalization (34), this means either that all vital TD-binding adaptors, CLASPs and accessory proteins encode at least one each of the particular binding motifs for the four specified sites, or that the motifs themselves are structurally malleable. If the latter is true, pitstops may, in fact, be able to occupy all four TD binding sites, albeit with different conformations and affinity (34); but this remains to be established. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) could have provided illuminating information on both the KD and the stoichiometry of pitstop binding to the TD in solution. It will certainly be interesting to determine whether pitstops interfere with clathrin-mediated endocytosis when only the surface chemistry of the clathrin-box site is altered by site-directed mutagenesis.

Irrespective of precisely how the pitstops prohibit TD protein–protein interactions, an obvious presumption is that in intact cells the inhibitors would prevent the massing of clathrin at internalizations sites on the plasma membrane. But nothing at all like this actually happens. Cargo ligands such as transferrin and epidermal growth factor can enter and concentrate within the clathrin-coated structures of pitstop-exposed cells, and the coats progress through all invagination stages, yet delivery to the cell interior is decreased tenfold. Instead of reduced delivery of clathrin to nascent bud sites, assembled clathrin appears to be stabilized and less dynamic (40). These rather unexpected results raise two central mechanistic questions: first, can new clathrin coats actually form in the presence of the pitstop drugs? Second, why are the assembled lattices seemingly stalled in these pharmacologically treated cells?

The nucleation of clathrin-coated structures at the cell surface of metazoan cells depends on phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2) (45–47). Hindering PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis rapidly and extensively obstructs de novo coat formation (48, 49). One facile way to manipulate surface PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels is by acute application of a primary alcohol, like 1-butanol (50). Cells treated with or without pitstop 2 promptly produce new clathrin-coated structures once 1-butanol is washed out (40). This shows, perhaps counter intuitively, that pitstops do not prevent deposition of clathrin triskelia at the plasma membrane and, along with other results, prompted Haucke and colleagues to conclude that the protein–protein interactions at the TD are not necessary for clathrin lattice formation (40).

The pitstops apparently work by blocking (some) interactions with the TD. If the compounds do not abolish clathrin recruitment in vivo, then their potent interference with clathrin-mediated uptake must evidently occur later, once the coat is assembling. A timed conversion from an AP-2-centric to a clathrin-centric interaction hub has been speculated to assure proper vectorial progression during coat assembly (39). Dynamic reorganization of TD connectivity, as the complex set of proteins mass at import sites with a specific temporal relationship (51–53), could be vital for the coordinated passage from the rather planar nascent lattice to the spherical, nearly complete clathrin-coated vesicle. That the yeast Chc1p TD chimera with human clathrin HC is recruited to patches at the plasma membrane but is unable to support robust transferrin uptake also hints at important rearrangements at the TD during clathrin-coated vesicle formation (34). Remarkably though, the pitstop blockade of clathrin-mediated endocytosis occurs without clear accumulation of any arrested intermediate along the budding process. Morphometric analysis reveals that all stages, from gently curved to deeply invaginated spherical profiles, are represented in the pitstop-treated cells (40). That a rate-limiting intermediate does not mount up indicates there does not appear to be a single stage where TD contacts need to be realigned to permit further lattice remodeling. So the phenotype implies that the synthetic drugs interfere with vesicle formation during multiple assembly steps. von Kleist et al. conclude that pitstop “stalls maturation or consumption” but what does this actually mean at the molecular level?

One alternative for stabilization of surface deposited clathrin could be by disruption of the uncoating process, since the uncoating co-chaperone auxilin (and the ubiquitous auxilin 2/GAK; cyclin G-associated protein kinase) binds physically to the TD in the process of properly placing Hsc70 for triskelion disassembly (54, 55). The bulk of auxilin is recruited to endocytic clathrin coats just after scission (53, 56), but there is evidence auxilin/GAK is also involved in the continual exchange of clathrin during coated vesicle assembly (57–59) (but see also (60) for a different opinion), so this idea seems in line with the failure of clathrin to recover at all within bleached zones of pitstop 2-treated cells subjected to fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments (40). The pitstops weakly inhibit uncoating in vitro, although without added auxilin and Hsc70 (61–63) enzymatic uncoating is not really being measured (40). Both auxilin and auxilin 2 encode several peptide motifs that bind physically to clathrin triskelia lacking the TD (54, 55). In any event, ATP-dependent, Hsc70-driven clathrin uncoating does not have to involve the TD directly (61), and auxilin also has several independent AP-2 interaction motifs to move into assembled coats (54, 55). A feature of auxilin-silenced cells (57, 59) and neurons from auxilin−/− mice (64) is pronounced accumulation of budded coated vesicles and abnormal stabilization of membrane free, cytosolic clathrin cages, which are not evident in pitstop inhibited cells. In S. cerevisiae, disruption of the gene encoding the auxilin orthologue (swa1/aux1) also causes aberrant accumulation of clathrin on membranes and coated vesicles (65, 66) so, generally, pitstop drugs do not closely phenocopy auxilin loss.

By dynamically regulating PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels, the phosphoinositide polyphosphatase synaptojanin 1 plays a role in remodeling and uncoating of endocytic clathrin coats (47, 67). The ubiquitously expressed long-splice isoform of synaptojanin 1, SJ170, also binds to the TD (68, 69) so another potential explanation for the inhibitory effects of pitstops could be by obstructing access of SJ170 to the maturing coated structure. Again, though, this seems unlikely because SJ170 has several AP-2 binding motifs in addition to the clathrin binding sequence (as does the short isoform SJ145 (70)), and the major diagnostic phenotype of synaptojanin loss-of-function in various metazoan species is the dramatic accumulation of budded clathrin-coated vesicles, but without evidence of massive assembly of empty cages (71–74). While there is a doubling of clathrin-coated pits at presynaptic terminals of pitstop 1-injected neurons, synaptojanin 1 loss results in a tenfold increase in coated vesicles (71–73). Analogous experiments in S. cerevisiae document that disruption of synaptojanin-like phosphatases leads to accumulation of PtdIns(4,5)P2 and a strong blockade in surface uptake. This is associated with accumulation of long membrane invaginations and delayed uncoating of endocytic vesicles (75, 76). To summarize, the pitstop-induced endocytic phenotype is dissimilar to that of either auxilin- or synaptojanin-depleted cells. Maybe a combination of these defects causes the complex phenotype but this still does not explain why any of three other surfaces on the TD not targeted by pitstop compounds are able to support transferrin internalization in vivo. Also somewhat unclear is why, with an IC50 of 10–20 μM, recovery from the effects of pitstop 2 in cells seems to require hours not minutes (40).

Outlook

Trying to place pitstop inhibitory action into a mechanistic framework for clathrin-mediated endocytosis seemingly challenges some widely held concepts; it is as if the small molecule inhibitors have overturned conclusions from decades of prior experimentation. A prevailing notion has been that physical adaptor/CLASP–TD interactions are, at least in part, the inaugural contacts that drive the polymerization of a clathrin coat (39, 77–83). Some of the data that underpin this model are that extended polyhedral arrays of assembled clathrin can be simply formed on synthetic membrane templates using disordered segments of CLASPs (84, 85) where the known clathrin binding information is clathrin-box-like motifs (86, 87). Careful, time-resolved, live-cell imaging of clathrin-mediated endocytosis discloses that at the time when clathrin recruitment begins, pioneer adaptors and CLASPs already populate the assembly zone (53, 88). Not all the proteins in this pioneer unit, like AP-2, FCHO1/2, eps15, epsin, CALM and NECAP, contact clathrin directly. Those that do (AP-2, epsin, CALM), have well characterized clathrin TD interaction motifs (10, 14, 89–93). To support their conclusion that the TD is not necessary for clathrin coat initiation, von Kleist et al. report that in clathrin heavy chain siRNA-treated cells, an RNAi resistant, N-terminally-deleted (ΔTD) heavy chain tagged with GFP targets apparently normally to the juxtanuclear TGN region as well as to dispersed peripheral surface puncta. Possibly these findings could be reconciled by the presence of other adaptor binding sites in the clathrin HC, such as the ankle binding site that interacts with Golgi associated, γ-adaptin ear containing, Arf binding protein 1 (GGA1) and AP-1/2 β chains (79). But Willox and Royle find, contrastingly, that deletion of the TD ( 1–330) or simultaneously disrupting all four TD binding sites significantly affects clathrin recruitment, especially at the plasma membrane, so the important discrepancy between these two mammalian studies will need to be resolved. Moreover in S. cerevisae, a similar chc1-ΔTD mutant expressed in the chc1-Δ strain behaves as a clathrin null (31).

It may also be significant that the initial screens for pitstop inhibitors used recombinant TD and not purified clathrin triskelia, because the strong avidity effects of the trimer and so-called ‘matricity’ (39, 52, 78) are lost. Also curious is why the effect of the pitstops on the interaction between clathrin and the AP-2 β2 subunit was not analyzed, as the β2 hinge + appendage segment alone can stimulate assembly of clathrin cages (14, 90, 94). In fact, nowhere in the von Kleist et al. study is it shown directly that pitstops physically thwart the normal trimeric functional unit, the triskelion (8), from binding to TD interaction motifs. It seems that the formal proof of their model requires alteration of the surface chemistry of the TD clathrin box site such that pitstop antagonists can no longer engage the β-propeller. But, in essence, this is what the Collette et al. (31) and Willox and Royle (34) studies did, although whether the mutations introduced forestall pitstop binding is currently not known for certain. It does, however, raise the issue of whether the structure-guided mutations are actually equivalent the to chemical inhibition–or whether the synthetic pitstops have additional mysterious effects?

There is a general belief or expectation that broad chemical screens coupled with iterative chemical refinement of initial ‘hits’ will lead to the development of pharmacological ‘magic bullets’ to interfere with selected biological events with extreme selectivity and potency. However, given the small molecular nature of typical inhibitors and the enormous range of potential contact surfaces upon thousands of different cellular proteins, unanticipated non-selective effects seem inevitable (95). For example, the leucine-based protease/proteasome inhibitor benzyloxycarbonyl-Leu-Leu-Leu-aldehyde (ZLLLal/MG132) can also bind to and affinity purifiy clathrin triskelia (96), clearly an unrelated molecular target. It is possible that in the cellular context pitstop compounds engage cryptic surfaces on the clathrin HC (or possibly other important endocytic components) not revealed by static structural studies (97) and that this is an important aspect of the in vivo action of these drugs. Nevertheless, in all probability, the new pitstops will rapidly supersede the crude, old pharmacological tools, like sucrose (98) and chlorpromazine (99), as the method of choice to interfere acutely with clathrin-regulated internalization. The compounds may even be efficacious in yeast. With the interest in and continued use of pitstops more information on their precise mode of action is likely to be collected. At the very least, these novel chemical inhibitors have deftly underscored the pivotal role of the clathrin TD in successful coated vesicle production. With a full complement of TD interaction surfaces now in hand, a more coherent mechanistic model to understand TD operation is certain to be forthcoming. Crucially, any new model must conceptually integrate experimental results derived from mutagenesis, in vitro biochemical and chemical studies, recognizing that each one is constrained in the range of instructive phenotypes that can be revealed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. Douglas Boettner, Frances Brodsky, John Collette, David Owen and Ernst Ungewickell for helpful comments and suggestions on the manuscript. Supported by NIH grants R01 GM55796 (SKL) and R01 DK53249 (LMT).

Abbreviations used in this manuscript

COP

coat protein complex

HC

heavy chain

TD

terminal domain

TGN

_trans_-Golgi network

References

- 1.Kirchhausen T. Three ways to make a vesicle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:187–198. doi: 10.1038/35043117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughson FM. Copy coats: COPI mimics clathrin and COPII. Cell. 2010;142:19–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Field MC, Sali A, Rout MP. Evolution: On a bender--BARs, ESCRTs, COPs, and finally getting your coat. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:963–972. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson MS. 100-kD coated vesicle proteins: molecular heterogeneity and intracellular distribution studied with monoclonal antibodies. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:887–895. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.4.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahle S, Mann A, Eichelsbacher U, Ungewickell U. Structural relationships between clathrin assembly proteins from the Golgi and the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 1988;7:919–929. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoorvogel W, Oorschot V, Geuze HJ. A novel class of clathrin-coated vesicles budding from endosomes. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:21–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sachse M, Urbe S, Oorschot V, Strous GJ, Klumperman J. Bilayered Clathrin Coats on Endosomal Vacuoles Are Involved in Protein Sorting toward Lysosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1313–1328. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ungewickell E, Branton D. Assembly units of clathrin coats. Nature (Lond) 1981;289:420–422. doi: 10.1038/289420a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.den Otter WK, Renes MR, Briels WJ. Asymmetry as the key to clathrin cage assembly. Biophys J. 2010;99:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahle S, Ungewickell E. Identification of a clathrin binding subunit in the HA2 adaptor protein complex. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20089–20093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallusser A, Kirchhausen T. The β1 and the β2 subunits of the AP complexes are the clathrin coat assembly components. EMBO J. 1993;12:5237–5244. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroder S, Ungewickell E. Subunit Interaction and Function of Clathrin-coated Vesicle Adaptors from the Golgi and Plasma Membrane. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7910–7918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Traub LM, Kornfeld S, Ungewickell E. Different domains of the AP-1 adaptor complex are required for Golgi membrane binding and clathrin recruitment. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4933–4942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shih W, Galluser A, Kirchhausen T. A clathrin binding site in the hinge of the β2 chain of the mammalian AP complexes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31083–31090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman OB, Jr, Krupnick JG, Santini F, Gurevich VV, Penn RB, Gagnon AW, Keen JH, Benovic JL. β-arrestin acts as a clathrin adaptor in endocytosis of the β2- adrenergic receptor. Nature. 1996;383:447–450. doi: 10.1038/383447a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson SS, Downey WE, 3rd, Colapietro AM, Barak LS, Menard L, Caron MG. Role of b-arrestin in mediating agonist-promoted G protein-coupled receptor internalization. Science. 1996;271:363–366. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krupnick JG, Goodman OB, Jr, Keen JH, Benovic JL. Arrestin/clathrin interaction. Localization of the clathrin binding domain of nonvisual arrestins to the carboxy terminus. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15011–15016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.15011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman OB, Jr, Krupnick JG, Gurevich VV, Benovic JL, Keen JH. Arrestin/clathrin interaction. Localization of the arrestin binding locus to the clathrin terminal domain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15017–15022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.15017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ter Haar E, Musacchio A, Harrison SC, Kirchhausen T. Atomic structure of clathrin: a β propeller terminal domain joins an α zigzag linker. Cell. 1998;95:563–573. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81623-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fotin A, Cheng Y, Sliz P, Grigorieff N, Harrison SC, Kirchhausen T, Walz T. Molecular model for a complete clathrin lattice from electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 2004;432:573–579. doi: 10.1038/nature03079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ter Haar E, Harrison SC, Kirchhausen T. Peptide-in-groove interactions link target proteins to the β propeller of clathrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1096–1100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dell’Angelica EC. Clathrin-binding proteins: got a motif? Join the network! Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:315–318. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinberg J, Drubin DG. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis in budding yeast. Trends Cell Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boettner DR, Chi RJ, Lemmon SK. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis: lessons from yeast. Nature Cell Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ncb2403. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conibear E. Converging views of endocytosis in yeast and mammals. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:513–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wendland B, Steece KE, Emr SD. Yeast epsins contain an essential N-terminal ENTH domain, bind clathrin and are required for endocytosis. EMBO J. 1999;18:4383–4393. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drake MT, Traub LM. Interaction of two structurally-distinct sequence types with the clathrin terminal domain β-propeller. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:28700–28709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramjaun AR, McPherson PS. Multiple amphiphysin II splice variants display differential clathrin binding: identification of two distinct clathrin-binding sites. J Neurochem. 1998;70:2369–2376. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70062369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slepnev VI, Ochoa GC, Butler MH, De Camilli P. Tandem arrangement of the clathrin and AP-2 binding domains in amphiphysin 1, and disruption of clathrin coat function mediated by amphiphysin fragments comprising these sites. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17583–17589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910430199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miele AE, Watson PJ, Evans PR, Traub LM, Owen DJ. Two distinct interaction motifs in amphiphysin bind two independent sites on the clathrin terminal domain β-propeller. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:242–248. doi: 10.1038/nsmb736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collette JR, Chi RJ, Boettner DR, Fernandez-Golbano IM, Plemel R, Merz AJ, Geli MI, Traub LM, Lemmon SK. Clathrin functions in the absence of the terminal domain binding site for adaptor-associated clathrin-box motifs. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:3401–3413. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang DS, Kern RC, Puthenveedu MA, von Zastrow M, Williams JC, Benovic JL. Structure of an arrestin2/clathrin complex reveals a novel clathrin binding domain that modulates receptor trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.023366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sterne-Marr R, Gurevich VV, Goldsmith P, Bodine RC, Sanders C, Donoso LA, Benovic JL. Polypeptide variants of b-arrestin and arrestin3. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15640–15648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willox AK, Royle SJ. Functional analysis of interaction sites on the N-terminal domain of clathrin heavy chain. Traffic. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01289.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee C, Goldberg J. Structure of coatomer cage proteins and the relationship among COPI, COPII, and clathrin vesicle coats. Cell. 2010;142:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stagg SM, Gurkan C, Fowler DM, LaPointe P, Foss TR, Potter CS, Carragher B, Balch WE. Structure of the Sec13/31 COPII coat cage. Nature. 2006;439:234–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fath S, Mancias JD, Bi X, Goldberg J. Structure and organization of coat proteins in the COPII cage. Cell. 2007;129:1325–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen CK, Chan NL, Wang AH. The many blades of the beta-propeller proteins: conserved but versatile. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmid EM, McMahon HT. Integrating molecular and network biology to decode endocytosis. Nature. 2007;448:883–888. doi: 10.1038/nature06031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.von Kleist L, Stahlschmidt W, Bulut HGK, Puchkov D, Robertson MJ, MacGregor KA, Tomilin N, Pechstein A, Chau N, Chircop M, Sakoff J, von Kries JP, Saenger W, Krausslich HG, Shupliakov O, et al. Role of the clathrin terminal domain in regulating coated pit dynamics revelaed by small molecule inhibition. Cell. 2011;146:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romer W, Berland L, Chambon V, Gaus K, Windschiegl B, Tenza D, Aly MR, Fraisier V, Florent JC, Perrais D, Lamaze C, Raposo G, Steinem C, Sens P, Bassereau P, et al. Shiga toxin induces tubular membrane invaginations for its uptake into cells. Nature. 2007;450:670–675. doi: 10.1038/nature05996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scita G, Di Fiore PP. The endocytic matrix. Nature. 2010;463:464–473. doi: 10.1038/nature08910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sorkin A, von Zastrow M. Endocytosis and signalling: intertwining molecular networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:609–922. doi: 10.1038/nrm2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pizarro-Cerda J, Bonazzi M, Cossart P. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis: what works for small, also works for big. Bioessays. 2010;32:496–504. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clague MJ, Urbe S, de Lartigue J. Phosphoinositides and the endocytic pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:1627–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jackson LP, Kelly BT, McCoy AJ, Gaffry T, James LC, Collins BM, Honing S, Evans PR, Owen DJ. A large-scale conformational change couples membrane recruitment to cargo binding in the AP2 clathrin adaptor complex. Cell. 2010;141:1220–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Antonescu CN, Aguet F, Danuser G, Schmid SL. Phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate regulates clathrin-coated pit initiation, stabilization, and size. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:2588–2600. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-04-0362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abe N, Inoue T, Galvez T, Klein L, Meyer T. Dissecting the role of PtdIns(4,5)P2 in endocytosis and recycling of the transferrin receptor. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1488–1494. doi: 10.1242/jcs.020792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zoncu R, Perera RM, Sebastian R, Nakatsu F, Chen H, Balla T, Ayala G, Toomre D, De Camilli PV. Loss of endocytic clathrin-coated pits upon acute depletion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3793–3798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611733104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boucrot E, Saffarian S, Massol R, Kirchhausen T, Ehrlich M. Role of lipids and actin in the formation of clathrin-coated pits. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:4036–4048. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaksonen M, Toret CP, Drubin DG. A modular design for the clathrin- and actin-mediated endocytosis machinery. Cell. 2005;123:305–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmid EM, Ford MG, Burtey A, Praefcke GJ, Peak Chew SY, Mills IG, Benmerah A, McMahon HT. Role of the AP2 β-appendage hub in recruiting partners for clathrin coated vesicle assembly. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taylor MJ, Perrais D, Merrifield CJ. A high precision survery of the molecular dynamics of mammalian clathrin mediated endocytosis. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scheele U, Alves J, Frank R, Duwel M, Kalthoff C, Ungewickell EJ. Molecular and functional characterization of clathrin and AP-2 binding determinants within a disordered domain of auxilin. J Biol Chem. 2003 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scheele U, Kalthoff C, Ungewickell E. Multiple interactions of auxilin 1 with clathrin and the AP-2 adaptor complex. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36131–361138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Massol RH, Boll W, Griffin AM, Kirchhausen T. A burst of auxilin recruitment determines the onset of clathrin-coated vesicle uncoating. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10265–10270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603369103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee DW, Zhao X, Zhang F, Eisenberg E, Greene LE. Depletion of GAK/auxilin 2 inhibits receptor-mediated endocytosis and recruitment of both clathrin and clathrin adaptors. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4311–4321. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eisenberg E, Greene LE. Multiple roles of auxilin and hsc70 in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Traffic. 2007;8:640–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hirst J, Sahlender DA, Li S, Lubben NB, Borner GH, Robinson MS. Auxilin depletion causes self-assembly of clathrin into membraneless cages in vivo. Traffic. 2008;9:1354–1371. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00764.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang CX, Engqvist-Goldstein AE, Carreno S, Owen DJ, Smythe E, Drubin DG. Multiple roles for cyclin G-associated kinase in clathrin-mediated sorting events. Traffic. 2005;6:1103–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ungewickell E, Ungewickell H, Holstein SEH, Lindner R, Prasad K, Barouch W, Martin B, Greene LE, Eisenberg E. Role of auxilin in uncoating clathrin-coated vesicles. Nature. 1995;378:632–635. doi: 10.1038/378632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rothnie A, Clarke AR, Kuzmic P, Cameron A, Smith CJ. A sequential mechanism for clathrin cage disassembly by 70-kDa heat-shock cognate protein (Hsc70) and auxilin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6927–6932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018845108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xing Y, Bocking T, Wolf M, Grigorieff N, Kirchhausen T, Harrison SC. Structure of clathrin coat with bound Hsc70 and auxilin: mechanism of Hsc70-facilitated disassembly. EMBO J. 2010;29:655–665. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yim YI, Sun T, Wu LG, Raimondi A, De Camilli P, Eisenberg E, Greene LE. Endocytosis and clathrin-uncoating defects at synapses of auxilin knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4412–4417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000738107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gall WE, Higginbotham MA, Chen C, Ingram MF, Cyr DM, Graham TR. The auxilin-like phosphoprotein Swa2p is required for clathrin function in yeast. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1349–1358. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00771-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pishvaee B, Costaguta G, Yeung BG, Ryazantsev S, Greener T, Greene LE, Eisenberg E, McCaffery JM, Payne GS. A yeast DNA J protein required for uncoating of clathrin-coated vesicles in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:958–963. doi: 10.1038/35046619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Perera RM, Zoncu R, Lucast L, De Camilli P, Toomre D. Two synaptojanin 1 isoforms are recruited to clathrin-coated pits at different stages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19332–19337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609795104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haffner C, Paolo GD, Rosenthal JA, de Camilli P. Direct interaction of the 170 kDa isoform of synaptojanin 1 with clathrin and with the clathrin adaptor AP-2. Curr Biol. 2000;10:471–474. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00446-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jha A, Agostinelli NR, Mishra SK, Keyel PA, Hawryluk MJ, Traub LM. A novel AP-2 adaptor interaction motif initially identified in the long-splice isoform of synaptojanin 1, SJ170. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2281–2290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Walther K, Diril MK, Jung N, Haucke V. Functional dissection of the interactions of stonin 2 with the adaptor complex AP-2 and synaptotagmin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:964–969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307862100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cremona O, Di Paolo G, Wenk MR, Luthi A, Kim WT, Takei K, Daniell L, Nemoto Y, Shears SB, Flavell RA, McCormick DA, De Camilli P. Essential role of phosphoinositide metabolism in synaptic vesicle recycling. Cell. 1999;99:179–188. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harris TW, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR, Jorgensen EM. Mutations in synaptojanin disrupt synaptic vesicle recycling. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:589–600. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim WT, Chang S, Daniell L, Cremona O, Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Delayed reentry of recycling vesicles into the fusion-competent synaptic vesicle pool in synaptojanin 1 knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17143–17148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222657399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gad H, Ringstad N, Low P, Kjaerulff O, Gustafsson J, Wenk M, Di Paolo G, Nemoto Y, Crun J, Ellisman MH, De Camilli P, Shupliakov O, Brodin L. Fission and uncoating of synaptic clathrin-coated vesicles are perturbed by disruption of interactions with the SH3 domain of endophilin. Neuron. 2000;27:301–312. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stefan CJ, Audhya A, Emr SD. The yeast synaptojanin-like proteins control the cellular distribution of phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:542–557. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sun Y, Carroll S, Kaksonen M, Toshima JY, Drubin DG. PtdIns(4,5)P2 turnover is required for multiple stages during clathrin- and actin-dependent endocytic internalization. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:355–367. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kirchhausen T. Imaging endocytic clathrin structures in living cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:596–605. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ungewickell EJ, Hinrichsen L. Endocytosis: clathrin-mediated membrane budding. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Knuehl C, Chen CY, Manalo V, Hwang PK, Ota N, Brodsky FM. Novel binding sites on clathrin and adaptors regulate distinct aspects of coat assembly. Traffic. 2006;7:1688–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Edeling MA, Smith C, Owen D. Life of a clathrin coat: insights from clathrin and AP structures. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:32–44. doi: 10.1038/nrm1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brodsky FM, Chen CY, Knuehl C, Towler MC, Wakeham DE. Biological basket weaving: formation and function of clathrin-coated vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:517–568. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Musacchio A, Smith CJ, Roseman AM, Harrison SC, Kirchhausen T, Pearse BM. Functional organization of clathrin in coats: combining electron cryomicroscopy and X-ray crystallography. Mol Cell. 1999;3:761–770. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)80008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Marsh M, McMahon HT. The structural era of endocytosis. Science. 1999;285:215–220. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ford MG, Pearse BM, Higgins MK, Vallis Y, Owen DJ, Gibson A, Hopkins CR, Evans PR, McMahon HT. Simultaneous binding of PtdIns(4,5)P2 and clathrin by AP180 in the nucleation of clathrin lattices on membranes. Science. 2001;291:1051–1055. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5506.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ford MG, Mills IG, Peter BJ, Vallis Y, Praefcke GJ, Evans PR, McMahon HT. Curvature of clathrin-coated pits driven by epsin. Nature. 2002;419:361–366. doi: 10.1038/nature01020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kalthoff C, Alves J, Urbanke C, Knorr R, Ungewickell EJ. Unusual structural organization of the endocytic proteins AP180 and epsin 1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8209–8216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhuo Y, Ilangovan U, Schirf V, Demeler B, Sousa R, Hinck AP, Lafer EM. Dynamic Interactions between clathrin and locally structured elements in a disordered protein mediate clathrin lattice assembly. J Mol Biol. 2010;404:274–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Henne WM, Boucrot E, Meinecke M, Evergren E, Vallis Y, Mittal R, McMahon HT. FCHo proteins are nucleators of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Science. 2010:328. doi: 10.1126/science.1188462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Drake MT, Downs MA, Traub LM. Epsin binds to clathrin by associating directly with the clathrin-terminal domain: evidence for cooperative binding through two discrete sites. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6479–6489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Greene B, Liu S-H, Wilde A, Brodsky FM. Complete reconstitution of clathrin basket formation with recombinant protein fragments: Adaptor control of clathrin self-assembly. Traffic. 2000;1:69–75. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rosenthal JA, Chen H, Slepnev VI, Pellegrini L, Salcini AE, Di Fiore PP, De Camilli P. The epsins define a family of proteins that interact with components of the clathrin coat and contain a new protein module. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33959–33965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tebar F, Bohlander SK, Sorkin A. Clathrin assembly lymphoid myeloid leukemia (CALM) protein: localization in endocytic-coated pits, interactions with clathrin, and the impact of overexpression on clathrin-mediated traffic. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2687–2702. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.8.2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Meyerholz A, Hinrichsen L, Groos S, Esk PC, Brandes G, Ungewickell EJ. Effect of clathrin assembly lymphoid myeloid leukemia protein depletion on clathrin coat formation. Traffic. 2005;6:1225–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Owen DJ, Vallis Y, Pearse BM, McMahon HT, Evans PR. The structure and function of the β2-adaptin appendage domain. EMBO J. 2000;19:4216–4227. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Roth BL, Sheffler DJ, Kroeze WK. Magic shotguns versus magic bullets: selectively non-selective drugs for mood disorders and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:353–359. doi: 10.1038/nrd1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Saito Y, Tsubuki S, Ito H, Ohmi-Imajo S, Kawashima S. Possible involvement of clathrin in neuritogenesis induced by a protease inhibitor (benzyloxycarbonyl-Leu-Leu-Leu-aldehyde) in PC12 cells. J Biochem. 1992;112:448–455. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Durrant JD, McCammon JA. Molecular dynamics simulations and drug discovery. BMC Biol. 2011;9:71. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-9-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Heuser JE, Anderson RGW. Hypertonic media inhibit receptor-mediated endocytosis by blocking clathrin-coated pit formation. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:389–400. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang L-H, Rothberg KG, Anderson RGW. Mis-assembly of clathrin lattices on endosomes reveals a regulatory switch for coated pit formation. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1107–1117. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.5.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]