Matrix Metalloproteinases as Biomarkers of Atherosclerotic Plaque Instability (original) (raw)

Abstract

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases responsible for tissue remodeling and degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. MMPs may modulate various cellular and signaling pathways in atherosclerosis responsible for progression and rupture of atherosclerotic plaques. The effect of MMPs polymorphisms and the expression of MMPs in both the atherosclerotic plaque and plasma was shown. They are independent predictors of atherosclerotic plaque instability in stable coronary heart disease (CHD) patients. Increased levels of MMPs in patients with advanced cardiovascular disease (CAD) and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) was associated with future risk of cardiovascular events. These data confirm that MMPs may be biomarkers in plaque instability as they target in potential drug therapies for atherosclerosis. They provide important prognostic information, independent of traditional risk factors, and may turn out to be useful in improving risk stratification.

Keywords: matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), atherosclerosis, biomarkers, doxycycline, statins

1. Introduction

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of zinc-dependent endoproteases responsible for tissue remodeling and degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins [1]. MMPs are secreted by endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle, fibroblasts, osteoblasts, macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes [2]. MMPs family contain 28 members, 23 are expressed in human tissues and 14 are expressed in veins and arteries. They are classified on the basis of their substrates and the organization of their structural domains [3]. MMPs may be inhibited by tissue and biological and synthetic inhibitors [4]. Endogenous tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) are widely distributed in many tissues and organs. In the case of biological inhibitors, doxycycline (an antibiotic) remains the single MMPs inhibitor that was approved by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical use [5]. Importantly, statins exert pleiotropic effects in vivo, including influence on signaling mechanisms that leads to MMPs inhibition. [6]. MMPs play important role in maintaining vein wall structure and function, but on the other hand, in adverse cardiovascular remodeling, atherosclerotic plaque formation and plaque instability [7,8]. Serum elevation of MMP-2, ADAMTS-1, and ADAMTS-7 is correlated with the initial stages of chronic venous disease (CVD), whereas the serum elevation of MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-9, NGAL, ADAM-10, ADAM-17, and ADAMTS-4 is particularly involved in skin change complications [9].

Increased activity of MMP-7 and MMP-9 was observed in unstable plaques, the highest tissue expression of MMP-9 was found in plaques of lipid type compared with plaques of necrotic and inflammatory-erosive types [10]. In addition, MMP-7 could contribute to plaque instability in carotid atherosclerosis, potentially involving macrophage-related mechanisms [11]. MMP-9 is a strong independent predictor of atherosclerotic plaque instability in stable coronary heart disease (CHD) patients, where MMP-9 levels are positively associated with the size of the necrotic core of coronary atherosclerotic plaques [12]. It was shown that serum MMP-9 and the MMP-9/TIMP-1 molar ratio may be valuable in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) diagnosis and prognosis. MMP-9 activation in serum was associated with poor cardiovascular outcome [13]. Tan et al. investigated associations of MMP-9 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) concentrations with the severity of carotid atherosclerosis, based on measurements of carotid plaque and intima–media thickness (IMT). Elevated serum MMP-9 concentration was independently associated with high total carotid artery plaque score, plaque instability, and large IMT value [14]. Importantly, using selective MMP-9 inhibitors may provide new perspective to intervene on ECM remodeling in humans [15]. These data confirm that MMPs may be biomarkers and have been proposed as potential therapeutic targets in cardiovascular diseases [16,17,18].

2. MMPs Structure and Tissue Distribution

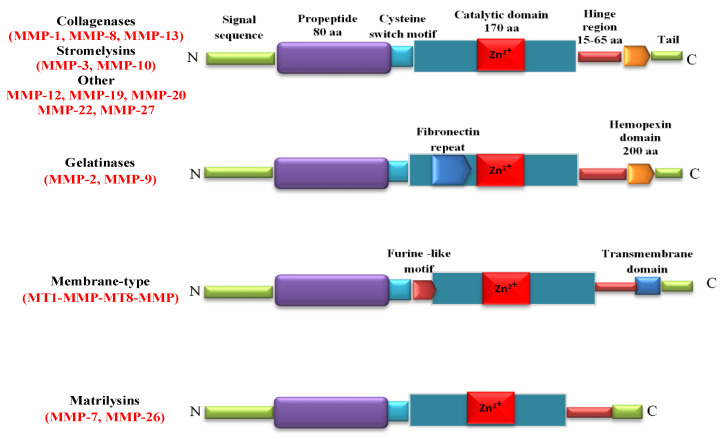

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are Zn2+ endopeptidases. They contain about 80 types of amino acids, a catalytic metalloproteinase domain (containing about 170 amino acids), a binding type of the special peptide or hinge-shaped region of variable length and a hemopexin stationary domain, with about 200 amino acids [19]. A definition of MMPs is based on their substrate specificity, structural organization, and cellular location. From a chemical point of view, the MMPs include collagenases (MMP-1/collagenase-1, MMP-8/collagenase-2, and MMP-13/collagenase-3), stromelysins (MMP-3/stromelysin-1, MMP-10/stromelysin-2, and MMP-11/stromelysin-3), gelatinases (MMP-2/gelatinase-A and MMP-9/gelatinase-B), membrane-type MMPs such as transmembrane MMP-14, MMP-15, MMP-16, MMP-24, membrane-anchored MMP-17, and MMP-25, and matrilysins (MMP-7/matrilysin-1 and MMP-26/matrilysin-2 [20] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Catalytic domain contains Zn2+ in the active site. Signal sequence and prodomain are removed during the proteolytic activation of pro-MMPs. Cysteine-rich switch is essential for the activation of MMPs. The hinge region serves as a linker between the catalytic domain and C-terminal domain.

The MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, and MMP-9 expression was found in endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), while MMP-12 showed expression in VSMCs and fibroblasts [21]. MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9, MMP-13, a membrane-type (MT) MMPs, MT-MMP1, and MT-MMP3 were found in the vascular wall [22]. Indeed leukocytes and dermal fibroblasts are key sources of MMP-2, whereas platelets are source of MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-14 [23] (Table 1).

Table 1.

The family of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), tissue distribution, and substrates.

| SUBFAMILY | MMP | Tissue Distribution | Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagenases | |||

| Collagenase-1 | MMP-1 | Endothelial cells, VSMCs, vascular wall, platelets, fibroblasts, macrophages | Collagens: I, II, III, VII, VIII, X Gelatins, entactin, aggrecan, link protein |

| Collagenase-2 | MMP-8 | Macrophages, neutrophils | Collagens: I, II, III;Aggrecan link protein |

| Collagenase-3 | MMP-13 | Vascular wall, SMCs, macrophages | Collagens: I, II, III |

| Gelatinases | |||

| Gelatinase-A | MMP-2 | Endothelial cells, VSMCs, adventitia, leukocytes, dermal fibroblasts, platelets | Collagens: I, IV, V, VII, X, XI;Gelatins, elastin, fibronectin, laminin, b-amyloid protein precursor |

| Gelatinase-B | MMP-9 | Endothelial cells, VSMCs, adventitia, vascular wall, macrophages | Collagens: IV, V, XIV; Gelatins, elastin, entactin, vitronectin |

| Stromelysins | |||

| Stromelysin-1 | MMP-3 | Endothelial cells, VSMCs, vascular wall, platelets | Collagens: III, IV, IX, X;Aggrecan, fibronectin, laminin, elastin, gelatins, casein |

| Stromelysin-2 | MMP-10 | Uterus | Collagens: II, IV, V;Aggrecan, fibronectin, gelatins, activate procollagenase |

| Stromelysin-3 | MMP-11 | Uterus, brain | Collagen IV, weakly fibronectin, laminin, aggrecan, gelatins, IGFBP-1, a1-protease inhibitor |

| Matrilysins | |||

| Matrilysin-1 | MMP-7 | Endothelial cells, VSMCs, vascular wall, uterus | Collagen IV,aggrecan fibronectin, laminin, entactin, vitronectin, casein, IGFBP-1 |

| Matrilysin-2 | MMP-26 | Collagen IV,gelatin, fibronectin | |

| Membrane-type MMPs | |||

| MT1-MMP | MMP-14 | Vascular wall, platelets, fibroblasts, uterus, brain | Collagens I, II, III; fibronectin, laminin-1, dermatan sulfate |

| MT2-MMP | MMP-15 | Fibroblasts, leukocytes | Large tenascin-C, fibronectin, laminin, entactin, aggrecan, perlecan |

| MT3-MMP | MMP-16 | Vascular wall, leukocytes | Collagen III, gelatin, casein, fibronectin |

| MT4-MMP | MMP-17 | Brain | Activates MMP2 by cleavage |

| MT5-MMP | MMP-24 | Leukocytes, lung, pancreas, kidney, brain | Activates MMP2 by cleavage |

| MT6-MMP | MMP-25 | Leukocytes | Inactivates alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor |

| Other | |||

| Metalloelastase | MMP-12 | VSMCs, fibroblasts, macrophages, great saphenous vein | Elastin, fibronectin |

| RASI-1 | MMP-19 | Liver | Gelatin |

| Enamelysin | MMP-20 | Tooth enamel | Amelogenin |

| Xenopus-MMP | MMP-21 | Fibroblasts, macrophages, placenta | |

| CA-MMP | MMP-23 | Ovary, testis | Gelatin |

| Epilysin | MMP-28 | Skin, keratinocytes | Casein |

3. Extracellular Vesicles as MMPs Carriers

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) as structures secreted by cells by the paracrine route include exosomes (diameter range: 30–100 nm), apoptotic bodies (diameter range: 0.1–1 μm), microvesicles (MVs, diameter range: > 1 μm), and large oncosomes (diameter range: 1–10 μm). They are released from cells as a result of fusion of the endosome with the plasma membrane. EVs participate in intercellular communication [24,25,26]. The composition of the microvesicles depends on the cell that secretes these structures. It is determined by a set of sorting proteins [27]. The mechanisms of transport of MMPs to extracellular vesicles are not fully understood. Sinha’s and Clark’s researches indicated that cortactin, as a regulator of matrix metalloproteinase secretion, was involved in this process [28,29]. In addition, the role of Rabi GTPases and kinesins in MMPs exposure to stem cell surface and packaging of these proteins into exosomes has been demonstrated [30,31]. In turn, the location of MMP-14 in exosomes depends on vesicle-associated membrane protein 3 (VAMP-3) [32].

EVs are involved in the secretion of MMPs into the intercellular space. As carriers of numerous proteins, including matrix metalloproteinases, extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN), and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), they can affect the reconstruction of the intercellular matrix, resulting in, among others atherosclerotic plaques destabilization [33]. Moreover, it has been shown that EVs not only transport MMPs but also participate in their activation. Studies by Bobryshev et al. have shown that at preatherosclerotic disease stage, the secretion of MMP-enriched EVs from arterial smooth muscle cells is significantly greater in the athero-prone areas of the human aorta than in the athero-resistant areas [34]. Research by Laghezza et al. showed the involvement of EVs in the proteolytic activation and secretion of MMP-9. Extracellular vesicles secreted by endothelial cells and platelets, as MMP-9 carriers, participate in the regulation of atherosclerotic plaque neovascularization. Angiogenesis is promoted at low levels of endothelial-derived microvesicles containing active MMP-2 and MMP-9, while high levels of these MVs inhibit plaque angiogenesis which reduces the risk of rupture [35]. In addition, Lozito et al. demonstrated that EVs secreted from endothelial cells are involved in the activation of MMP-2 initiating remodeling of the vascular matrix [36,37]. MMP-2 present in EC-derived vesicles also participates in neovascularization, promoting capillary structure formation and plaque rupture [25,38]. It is known that MT1-MMP present in exosomes secreted by fibroblasts participates in the pro-MMP2 activation process [39]. In turn, studies in ApoE (-/-) mice have showed that olmesartan significantly limit the formation of atherosclerotic lesions in the aorta by reducing the activity of MMP-2 [40].

MMP-rich microvesicles are effective modulators of weakening of the fibrous cap. Neutrophil-derived MVs enriched in MMP-9, metalloproteinase domain-containing proteins 10 (ADAM-10), and -17 (ADAM-17), as well as matrix-derived MVs rich in MMP-2 and endothelial MMP-10-enriched MVs, play a huge role in this process [41]. In addition, exosomes secreted by various cells, including macrophages, transporting MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9, and MMP-13, simultaneously contribute to vascular calcification. This increases plaque susceptibility to rupture, leading to life-threatening cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction [35,42,43,44]. Studies in patients with chronic kidney disease have shown that under mineral imbalance, there is an increased secretion of MMP-2-rich exosomes from vascular smooth muscle cells, which converts the exosomes into loci to endothelial calcification [45]. Chondrocyte-derived MVs containing MMP-3 participate in the calcification process of extracellular vesicles in the fibrous collagen of the extracellular matrix of cardiovascular tissues. Their secretion is induced by phosphate through extracellular kinases regulated by the Erk1/2 signal pathway [33].

Exosomes may serve as biomarkers for the development of atherosclerosis, providing potential roles for diagnosis and treatment [46]. Quantitative analysis of MMP-rich extracellular vesicles (especially those containing MMP-2 and -9) can be used as a parameter to assess calcification and plaque neovascularization in monitoring the clinical course of cardiovascular diseases. MVs analysis also seems to be helpful in identifying patients at risk of cardiovascular disease. MVs can also be a therapeutic target for preventing and controlling the development of atherosclerosis, including progression of plaque formation and its instability [40,47].

4. Biological Inhibitors of MMPs

Among tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs), such as tetracyclines, chemically-synthesized small-molecular weight MMP inhibitors and inhibitory antibodies, only doxycycline, which was approved by FDA, has been evaluated extensively in patients [48]. In a TIPTOP study, doxycycline decreased infarction size, and showed improvement of cardiac contractility characteristic in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and left ventricular (LV) dysfunction [49]. Additionally, in another clinical trial, short-term treatment with doxycycline caused reduction of MMP-2 activity in coronary bypass patients [50]. It was shown that doxycycline attenuates heart mechanical dysfunction and reduces inflammation in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) [51]. In addition to its potential plaque stabilization in acute coronary syndromes properties, doxycycline shows promise in preventing ischemia-reperfusion injury and left ventricular remodeling [52]. Furthermore, clinical study demonstrated that doxycycline therapy led to downregulation of MMPs, dampening cardiac inflammation, and reduction of secondary myocardial infarction (MI) risk in coronary bypass patients [53].

The statins may inhibit expression of MMPs in atherosclerotic plaques by reducing vascular inflammation [54,55]. Atorvastatin inhibits MMP-1, MMP-2, and MMP-9 expression in human retinal pigment epithelial cells [56] and MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9 secretion from rabbit macrophages and cultured rabbit aortic and human saphenous vein VSMCs [57]. Komukai et al. in the EASY-FIT clinical trial indicated that atorvastatin increased fibrous cap thickness and plaque stability and decreased levels of MMP-9 in CAD patients [58]. Further, Liu et al. confirmed that atorvastatin reduced plasma MMP-9 levels and myocardial dysfunction in STEMI [59]. Li et al. demonstrated that simvastatin significantly suppressed LPS-induced MMP-9 release and mRNA expression in a time- and concentration-dependent manner [60]. It was shown that in a rat model of heart failure, pravastatin suppressed the increase in myocardial MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity [61]. In addition, rosuvastatin inhibits the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 [62]. Moreover, a recent study reported the efficiency of combined therapy with rosuvastatin and ezetimibe to treat plaque instability and cardiovascular inflammation in CAD patients, by a significant decrease in MMP-9 plasma concentration [63]. Sapienza et al. recently showed that patients with advanced PAD, a pathological condition of hemodynamic instability of the atheromatous plaque, had good results from the association between platelet aggregation inhibitors and statins in terms of patency of the reconstructions [64,65].

5. MMPs in Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the vessel wall that is largely driven by an innate immune response [66]. In pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, a pivotal role is played by innate immunity receptors such as toll-like receptors (TLR) and receptors for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) [67]. TLR and RAGE mediate in macrophages and leukocyte recruitment and are significantly involved in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis [68]. This process is characterized by the accumulation of lipids, smooth muscle cell proliferation, cell apoptosis, necrosis, and fibrosis [69]. MMPs plays a key role in all stages of atherosclerosis through vascular inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, smooth muscle cell migration, vascular calcification, extracellular matrix degradation, and plaque activation and destabilization [8,16,70]. The expression of MMPs is controlled by different microRNA molecules. MicroRNA regulation of extracellular matrix components is crucial in the process of atherosclerotic plaque destabilization [71]. In the artery wall, subendothelial retention of plasma lipoproteins triggers monocyte-derived macrophages and T helper type 1 (Th1) cells to form atherosclerotic plaques. Plaque rupture or endothelial erosion can induce thrombus formation, leading to myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke [72]. Ruptured plaques are characterized by a large lipid-rich core, a thin fibrous cap that contains few smooth muscle cells and many macrophages, angiogenesis, adventitial inflammation, and remodeling. Plaque rupture is the most common cause of coronary thrombosis [73]. It was shown that endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) is a cellular reprogramming mechanism by which endothelial cells acquire a mesenchymal phenotype. EndMT contributes to the initiation and progression of atherosclerotic lesion and plaque destabilization, which further causes acute cardiovascular events [74].

5.1. MMPs in Vascular Inflammation and Recruitment of Immune Cells

MMPs participate in the immune response and play a key role in vascular inflammation that is strongly associated with atherosclerosis [75]. Exposure of vascular wall cells to inflammatory mediators produced under chronic inflammation may lead to excessive MMPs activity in the arterial wall resident and recruited cells [70,76]. In response to proinflammatory mediators, monocytes enhance MMPs expression and play a key role in inflammatory cell migration and invasion into the arterial wall [77]. Human monocytes not only express TIMP-1, TIMP-2, MMP-8, MMP-12, and MMP-19 but also activate MAP kinase and NF-κB, and in this way promote the expression of MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-10, and MMP-14. The ratio between MMPs and their inhibitors (TIMPs) to free active MMPs is critical in pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases [78]. TIMP-2 plays a protective role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis by suppressing MMP-14-dependent monocyte/macrophage accumulation into plaques [79]. MMP-1 expression is augmented in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases through upregulation by inflammatory cytokines such as TNF α (tumor necrosis factor-α) and IL-1 (interleukin-1) [80]. These inflammatory cytokines participate in ROS (reactive oxygen species) production and influence the expression and activity of MMPs. In addition, activation of the PDGFR-β and ERK1/2 atherogenic pathways participates in the production of MMP-1 in human coronary smooth muscle cells (SMCs) stimulated by oxidized low-density lipoproteins (oxLDL) [81].

5.2. MMPs in Lipid Accumulation

Migration of macrophages as well as deposition of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) under the endothelium initiate the process of atherosclerosis [82]. Oxidatively modified LDL (oxLDL) are involved in the transformation of macrophages into foam cells and the migration of VSMCs into the intima [83]. Foam cell macrophages, VSMCs, and endothelial cells produce cytokines enhancing the recruitment of inflammatory cells, which in turn attracts VSMCs into the neointima [48]. MMPs and TIMPs are secreted constitutively or after activation by inflammatory response not only by monocytes and macrophages but also by foam cells [84]. oxLDL activates MMP-2 through upregulation of the MT1-MMP expression and stimulation of oxidative radicals production by xanthine/xanthine oxidase [85]. In slow-to-heal wounds increased activity and expression of MMP-1, MMP-8, and MMP-9 have been shown, accompanied with low TIMPs levels [86]. It was shown that MMP-9 can modulate cholesterol metabolism, through MMP-9-plasma secreted phospholipase A2 axis [87].

5.3. MMPs in Endothelial Dysfunction

MMPs have been found to be involved in vascular wall remodeling and atherosclerosis development through inflammatory activation and endothelium dysfunction [88]. The dysfunction of endothelium is characterized by proinflammatory and prothrombic state; the action of the endothelium is shifted toward reduced vasodilation, and the phenotype changes from antiadhesive to proadhesive [89]. Damage of endothelial junctions results in enhanced endothelial permeability, which facilitates infiltration of various inflammatory mediators. Activation of endothelial MMP-2 can induce endothelial dysfunction and disintegrity [90]. Recruited vascular wall cells can remodel the surrounding extracellular matrix through MMPs that affect migration, proliferation, and apoptosis of endothelial cells and VSMCs [91].

5.4. MMPs in Migration of VSMCs

MMPs contribute to intimal thickening and vessel wall remodeling in atherosclerosis by promoting migration and proliferation of VSMCs [92,93]. MMPs degrade ECM and facilitate VSMCs migration into the intima. Studies have shown that MMP-2 is involved in these alterations of VSMCs behaviors. IL-1β, cytokine responsible for VSMCs migration, activates MMP-2 synthesis [94]. MMP-2 plays a key role in ox-LDL-induced activating VSMCs proliferation through various pathways [95]. TNF-α promotes VSMCs migration through MMP-9 upregulation [96]. Enhanced expression of MMP-9 in VSMCs can be caused by angiotensin II (Ang II) that participates in atherosclerosis by NF-κB pathways and angiotensin type 1 receptor [97]. Moreover, MMP-9 stimulates proliferation of VSMCs by regulating cell adhesion and cadherin association [98]. Increased serum MMP-10 levels were connected with increased carotid intima–media thickness, atherosclerotic plaques, and inflammatory markers in patients with preclinical atherosclerosis [99]. Activity of certain variant of the MMP-3 promoter was correlated with progression of luminal narrowing of coronary arteries [100,101].

5.5. MMPs in Plaque Neovascularization

Remodeling of extracellular matrix and vascular basement membrane allow to form new blood vessels. Studies have shown that MMP-9 mobilizes vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) from the ECM, which can contribute to plaque neovascularization. The increase of VEGF bioavailability results from the ECM proteolysis. [102]. Hypoxia and inflammation in the lesion can induce plaque neovascularization, which leads to plaque rupture [103]. In hypoxia, the direct target of injury are endothelial cells. Hypoxia induces cell proliferation in the vascular wall and results in increased MMP-9 expression in VSMCs [104]. These cells enhance MMPs activity in hypoxic areas. The interaction of macrophages with VSMCs influences neovascularization and destabilization of plaque because of enhanced MMP-1 and MMP-9 production [105]. In neovascularization, MMPs play a crucial role because of their participation in penetration of the ECM and tissue remodeling. The cross-talk between VSMCs and macrophages augments synthesis of angiogenic factors. Both cells produce not only VEGF and IL-1β (cytokine, stimulating the secretion of VEGF) but also MMPs responsible for degradation of ECM components, resulting in penetration and reshaping of connective tissue.

5.6. MMPs in Plaque Calcification

MMPs were also demonstrated to provoke vascular calcification [106]. Vascular calcification is determined as an attribute of advanced atherosclerotic plaques. The plasma level of MMP-7 is positively associated with carotid calcification [107]. Additionally, MMP-2 contributes to the calcification of SMCs, participating in the formation of vascular calcified lesions. MMP-2 deficiency in ApoE-/- mice related to suppressed calcium deposition in aorta-derived cultured SMCs [108]. In ApoE-/- mice with advanced atherosclerotic lesion, chondrocyte-like cells were found and several bone-related proteins were expressed [109]. Platelets contain and release MMPs within vascular injury [110]. MMP-2 participates in thrombogenesis, cleaving platelet proteinase-activated receptor 1 (PAR1), and stimulating the aggregation of platelets [111]. Purroy et al. research showed low MMP-10 expression, while significantly reducing the area of atherosclerosis and their calcification in ApoE-/- Mmp10 -/- mice. Furthermore, studies in subjects with subclinical atherosclerosis showed a correlation between MMP-10 serum activity and the degree of coronary calcification [112].

5.7. MMPs in Plaque Activation and Destabilization

Studies indicate the involvement of MMPs in atherosclerotic plaque initiation, progression, and plaque rupture [113]. Link between inflammation and plaque vulnerability might provide increased CRP-related MMPs activation [114]. MMP-1 may contribute to the progression of the human atherosclerotic lesions by remodeling of the neointimal extracellular matrix (ECM) [115]. An important role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and plaque rupture may be played by enhanced MMP-1 expression induced by monocyte–endothelial cell interactions [116].

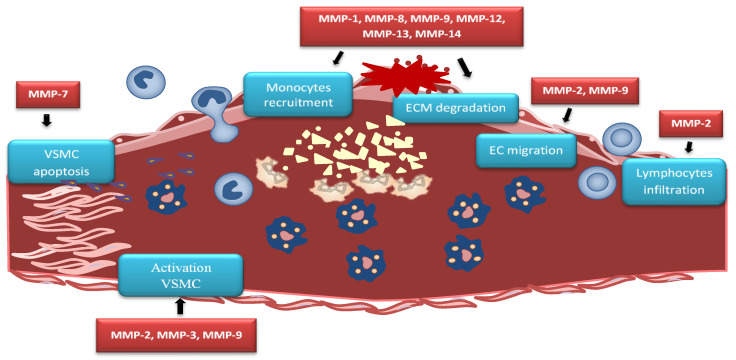

Advanced atherosclerotic plaque is filled by cell debris, extracellular lipids, and foam cell macrophages, whereas stable plaque is protected from the circulating blood by a fibrous cap. Plaque destabilization can be caused by proteolysis of fibrillar collagens. MMP-1, MMP-8, and MMP-13 show this collagenolytic activity in unstable plaques [117,118]. Studies on human cells infected with influenza A virus showed an increase of MMP-13 expression, which may partly explain the destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques. Analysis of the corresponding changes in the ApoE-deficient mouse model has shown that the increase of MMP-13 expression is due to activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway [119]. Increased MMP-7 activity can be connected with the apoptosis of VSMCs in the fibrous cap and lesion destabilization [120]. Enhanced MMP-7 activity is involved in the cleavage of N-cadherin, which mediates VSMCs apoptosis, resulting in plaque instability [121]. Vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques are characterized by increased MMPs levels [122]. Activated VSMCs produce high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), which affects the expression of MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9 and enhances plaque rupture [123] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

MMPs in atherosclerotic plaque. MMP-2 causes lymphocytes infiltration while MMP-2 and MMP-9 causes endothelial cells (EC) migration. MMP-7 activity leads to vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) apoptosis, contributing to plaque instability. Activated VSMCs produce high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) which affects the expression of MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9 and enhances plaque rupture. MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-12, MMP-13, and MMP-14 trigger similar effect by extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation within the fibrous cap that causes plaque rupture.

Genetic variants of MMP-9 were found to be associated with different stages of atherosclerosis [124]. Crucial significance of MMP-9 in the growth of atherosclerotic plaque is shown in ApoE-deficient mice [125]. Atherosclerotic plaque formation is associated with hypertension-induced atherosclerosis and increased levels of MMP-9 mRNA [126]. Matrix-degrading activity of MMPs contributes to complications of human atherosclerotic lesions. Studies have shown enhanced expression of MMPs in macrophage-rich areas (around lipid-rich core) suggesting important role of MMPs (derived from macrophages) in developing of vulnerable regions of atherosclerotic plaques [127]. Ablation of MMP-9 contributed to the reduction of atherosclerotic burden and attenuated macrophage infiltration and collagen deposition. In addition, imbalance in the expression of MMP-9/TIMP-1 was perceived in macrophages within the atherosclerotic plaques [128]. A positive correlation between MMP-9 macrophages and plasma lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) concentration was also shown. This is particularly important due to the fact that MMP-9 is derived from macrophages with coronary plaque instability. As demonstrated by Gu et al., LPA acting through the LPA2 receptor can induce MMP-9 by activating the NF-κB pathway [129] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participation of MMPs in processes involved in development and progression of atherosclerotic plaque.

| Vascular Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction | |

|---|---|

| Increase of inflammatory cell migration and invasion into the arterial wall | MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-12, MMP-13, MMP-14 |

| Influence on endothelial dysfunction | MMP-2, MMP-9 |

| Participation in oxLDL effect | MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-8, MMP-9 |

| Promotion of EC apoptosis | MMP-9 |

| Development of Plaque | |

| Increase of intima–media thickness | MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-10 |

| Promotion of plaque growth | MMP-2 |

| Promotion of VSCMs migration | MMP-9 |

| Decrease of VSCMs contractility | MMP-2, MMP-9 |

| Neovascularization | |

| Degradation of ECM | MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-12, MMP-13, MMP-14 |

| Release of growth factors | MMP-2, MMP-9, MMP-13, MMP-14 |

| Calcification | |

| Provoke vascular calcification | MMP-2, MMP-7 |

| Plaque Activation and Destabilization | |

| Apoptosis of VSMCs in the fibrous cap | MMP-7 |

| Collagenolytic activity | MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-13 |

| Enhances plaque rupture | MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-12, MMP-13, MMP-14 |

Evidence suggests that neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) may play a crucial role in vascular remodeling and plaque instability during the development of atherosclerosis [130]. NGAL is involved in the regulation of MMP activity. MMPs and NGAL also play a key role in development of arterial aneurysms [131]. The complex formation between NGAL and MMP-9 suggests that NGAL might play a role in progression of atherothrombotic disease. NGAL has performed as a more consistent predictor of adverse outcomes in patients with ACS, especially STEMI, compared with patients having stable CAD [132]. NGAL was associated with increased risk of long-term CHD events, independent of conventional risk factors and biomarkers [133].

6. MMPs as Biomarkers in Cardiovascular Diseases

MMPs are involved in various stages of plaque progression that are important to predict future atherothrombotic cardiovascular events [134]. Vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques are responsible for life-threatening clinical endpoints; thus, the best approach for both stroke and myocardial infarction (MI) would be safe diagnosis and knock out of the vulnerable lesion before endpoints occur [135]. Higher markers of matrix remodeling, such as MMP-9 and TIMP-1, were associated with a greater prevalence of carotid stenosis and subclinical atherosclerosis in the internal carotid artery (IC) [136]. Sequence variants at the MMP-1 genomic locus may influence risk of coronary heart disease in humans [137]. MMP-1 (-1607 1G/2G) and MMP-3 (-1171 5A/6A) polymorphisms may contribute to different subtypes of ischemic stroke susceptibility [138].

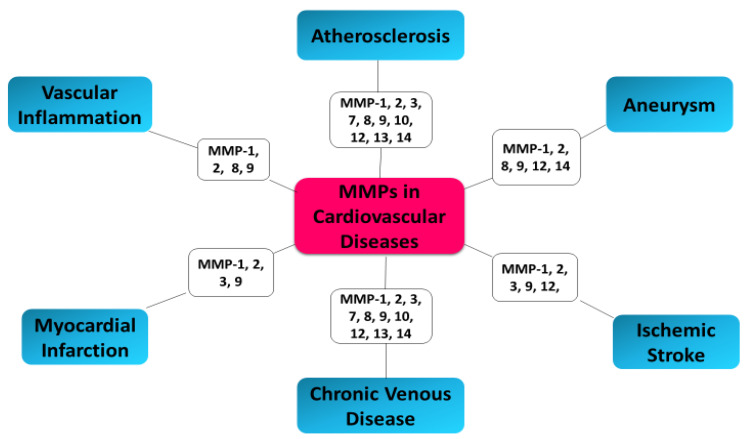

Since 2005, Sapienza and coauthors showed that an imbalance exists between MMPs and TIMPs in unstable carotid plaques, which is reflected in the plasma levels of these markers [139]. Disturbed equilibrium of the metalloproteinase/tissue inhibitors system, destabilization of atherosclerotic plaque, and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in patients are caused by increased expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitor (TIMP-2) [140]. Studies have indicated that MMP-2, MMP-8, and MMP-9 facilitate plaque rupture and clinical events [18,118]. In 2006, Turu et al. demonstrated significantly higher MMP-8 plasma concentrations in patients with unstable atherosclerotic plaques compared to patients with stable plaques [141]. The results of recent research confirm the relationship between MMP-8 and the processes of remodeling and destabilization of the plaque. A demonstrated relationship between the variability of the MMP-8 gene and atherosclerosis suggest that MMP-8 concentrations may have prognostic and diagnostic significance in assessing the patient’s cardiovascular risk [142]. MMP-8 has also been shown to be a proteinase responsible for the activation of other MMPs, such as MMP-2 and MMP-9 [143,144]. MMP-2 promotes a platelet aggregation, which is involved in a prothrombotic effect of atherosclerotic plaques. Enhanced MMP-2 activity was especially observed in plaques of patients with a higher rate of subsequent major cardiovascular events [145]. MMP-2 has been determined as a predictor of mortality in patients with ACS [146]. High levels of MMP-8 in the carotid plaque correlate with an unstable plaque composition and systemic cardiovascular outcome [147]. Seifert et al. confirmed that MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities was significantly higher in the ApoE-/- cuff model in unstable atherosclerotic plaques as compared to downstream more stable plaque phenotypes [148]. Increased plasma MMP-9 and TIMP-1 levels have been demonstrated in the coronary circulation in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), which suggests active process of plaque rupture and future risk of cardiovascular events [149]. Kelly et al. have shown the association of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 with function and remodeling of left ventricular (LV) as well as cardiovascular death or heart failure [150]. The correlation between TIMP-1 and MMP-9 and echocardiographic parameters of LV remodeling after AMI (acute myocardial infarction) suggest a promising indicator of patients with adverse prognosis. In type 2 diabetes mellitus, elevated MMP-7 and MMP-12 plasma levels are linked with severe atherosclerosis as well as more frequent coronary events [151]. The stronger elevated plasma levels of MMP12 and imbalance between MMP12 and TIMP1 was observed in patients with STEMI compared to patients with stable angina pectoris [152]. Moreover, another study has shown elevated peripheral blood levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in patients with ACS [153]. Blankenberg et al. demonstrated that plasma MMP-9 concentrations may constitute risk markers for future cardiovascular death in ACS patients [154]. However, this study also has shown the correlation between MMP-9 level and acute-phase reactants; therefore, independent prognostic information of MMPs is not clear. Moreover, increased levels of TIMPs are associated with enhanced risk of cardiovascular events in patients with ACS [155,156]. Elevated MMPs levels have been shown not only in affected tissue in patients with ACS, arthritis, and cancer but also in peripheral blood, suggesting elevated blood MMPs levels in patients at risk of acute plaque disruption [153]. Higher plasma MMP-9 levels have been shown in patients with significant carotid stenosis undergoing carotid endarterectomy with detected spontaneous embolization, compared to patients without it [157]. MMP-9 expression and macrophage infiltration constitute strong indicators of high risk atherosclerotic carotid plaques and plaque instability [158,159]. MMP-9 may have vital significance in differentiating patients with unstable angina with or without plaques [160]. In patients with angiographically confirmed coronary heart disease (CHD), it was showed that increased concentrations of MMP-9 at baseline were associated with future cardiovascular (CV) death [161]. Tang et al. demonstrated that increased plasma levels of MMP2 and MMP9 in patients with coronary heart diseases (CHD) suggest the instability of the atherosclerotic plaque in correlation to the severity of ACS, and may serve as good indicators for the prediction of ACS and diagnosis of chronic total occlusion (CTO) of the coronary artery [162]. MMP-2 and MMP-9 circulating levels can serve as indicators of efficiency of the therapy provided to heart failure (HF) patients, as well as for identification of patients who could benefit from particular therapeutic intervention via modification of MMP pathway [163] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

MMPs as biomarkers in cardiovascular diseases.

7. Conclusions

Accumulating evidence confirm the key role of MMPs in plaque development and pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, especially in the advanced stages of the disease, where their elevated activity increases the risk of plaque rupture. The degradation of extracellular matrix protein is catalyzed by MMPs and participates in the migration of vascular SMCs and consequently, leads to plaque instability. Increased peripheral blood MMP-2 and MMP-9 in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) may be useful as noninvasive tests for detection of plaque vulnerability. Local carotid plaque MMP-8 level corresponds with a higher frequency of secondary manifestations of cardiovascular disease during follow-up, and increased plasma levels are predictive for subsequent all-cause mortality. Mentioned findings suggest that local MMPs plaque levels may be useful in detection of the vulnerable plaque and can help to predict patients with high risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular events. The use of biomarkers to select patients for individualized therapies in secondary prevention will help achieve the goal of precision medicine. [164]. In addition, modulation of immune-mediated inflammation is a new promising point of action for the eradication of fatal atherosclerotic events [135]. The Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study (CANTOS) trial confirmed that targeting inflammation with interleukin-1β (IL-1 β) inhibition significantly reduces cardiovascular events [165].

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Nagase H., Visse R., Murphy G. Structure and function of matrix metalloproteinases and timps. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;69:562–573. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacColl E., Khalil R.A. Matrix metalloproteinases as regulators of vein structure and function: Implications in chronic venous disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2015;355:410–428. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.227330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marino-Puertas L., Goulas T., Gomis-Ruth F.X. Matrix metalloproteinases outside vertebrates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2017;1864:2026–2035. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta S.P. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors: Specificity of binding and structure-activity relationships. Exp. Suppl. 2012;103:v–vi. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Q., Jin M., Yang F., Zhu J., Xiao Q., Zhang L. Matrix metalloproteinases: Inflammatory regulators of cell behaviors in vascular formation and remodeling. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:928315. doi: 10.1155/2013/928315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiang B., Toma J., Fujii H., Osherov A.B., Nili N., Sparkes J.D., Fefer P., Samuel M., Butany J., Leong-Poi H., et al. Statin therapy prevents expansive remodeling in venous bypass grafts. Atherosclerosis. 2012;223:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loftus I.M., Naylor A.R., Bell P.R., Thompson M.M. Matrix metalloproteinases and atherosclerotic plaque instability. Br. J. Surg. 2002;89:680–694. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myasoedova V.A., Chistiakov D.A., Grechko A.V., Orekhov A.N. Matrix metalloproteinases in pro-atherosclerotic arterial remodeling. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2018;123:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serra R., Gallelli L., Butrico L., Buffone G., Calio F.G., De Caridi G., Massara M., Barbetta A., Amato B., Labonia M., et al. From varices to venous ulceration: The story of chronic venous disease described by metalloproteinases. Int. Wound J. 2017;14:233–240. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volkov A.M., Murashov I.S., Polonskaya Y.V., Savchenko S.V., Kazanskaya G.M., Kliver E.E., Ragino Y.I., AM C.H. Changes of content of matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue expression in various types of atherosclerotic plaques. Kardiologiia. 2018;10:12–18. doi: 10.18087/cardio.2018.10.10180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbas A., Aukrust P., Russell D., Krohg-Sorensen K., Almas T., Bundgaard D., Bjerkeli V., Sagen E.L., Michelsen A.E., Dahl T.B., et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 7 is associated with symptomatic lesions and adverse events in patients with carotid atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e84935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ezhov M., Safarova M., Afanasieva O., Mitroshkin M., Matchin Y., Pokrovsky S. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 as a predictor of coronary atherosclerotic plaque instability in stable coronary heart disease patients with elevated lipoprotein(a) levels. Biomolecules. 2019;9:129. doi: 10.3390/biom9040129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lahdentausta L., Leskela J., Winkelmann A., Tervahartiala T., Sorsa T., Pesonen E., Pussinen P.J. Serum MMP-9 diagnostics, prognostics, and activation in acute coronary syndrome and its recurrence. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2018;11:210–220. doi: 10.1007/s12265-018-9789-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan C., Liu Y., Li W., Deng F., Liu X., Wang X., Gui Y., Qin L., Hu C., Chen L. Associations of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 concentrations with carotid atherosclerosis, based on measurements of plaque and intima-media thickness. Atherosclerosis. 2014;232:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yabluchanskiy A., Ma Y., Iyer R.P., Hall M.E., Lindsey M.L. Matrix metalloproteinase-9: Many shades of function in cardiovascular disease. Physiology. 2013;28:391–403. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00029.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown B.A., Williams H., George S.J. Evidence for the involvement of matrix-degrading metalloproteinases (MMPs) in atherosclerosis. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2017;147:197–237. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui N., Hu M., Khalil R.A. Biochemical and biological attributes of matrix metalloproteinases. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2017;147:1–73. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J., Tan G.J., Han L.N., Bai Y.Y., He M., Liu H.B. Novel biomarkers for cardiovascular risk prediction. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2017;14:135–150. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cauwe B., Van den Steen P.E., Opdenakker G. The biochemical, biological, and pathological kaleidoscope of cell surface substrates processed by matrix metalloproteinases. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007;42:113–185. doi: 10.1080/10409230701340019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amin M., Pushpakumar S., Muradashvili N., Kundu S., Tyagi S.C., Sen U. Regulation and involvement of matrix metalloproteinases in vascular diseases. Front. Biosci. 2016;21:89–118. doi: 10.2741/4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sansilvestri-Morel P., Fioretti F., Rupin A., Senni K., Fabiani J.N., Godeau G., Verbeuren T.J. Comparison of extracellular matrix in skin and saphenous veins from patients with varicose veins: Does the skin reflect venous matrix changes? Clin. Sci. 2007;112:229–239. doi: 10.1042/CS20060170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pradhan-Palikhe P., Vikatmaa P., Lajunen T., Palikhe A., Lepantalo M., Tervahartiala T., Salo T., Saikku P., Leinonen M., Pussinen P.J., et al. Elevated MMP-8 and decreased myeloperoxidase concentrations associate significantly with the risk for peripheral atherosclerosis disease and abdominal aortic aneurysm. Scand. J. Immunol. 2010;72:150–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seizer P., May A.E. Platelets and matrix metalloproteinases. Thromb. Haemost. 2013;110:903–909. doi: 10.1160/TH13-02-0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raposo G., Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013;200:373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deng W., Tang T., Hou Y., Zeng Q., Wang Y., Fan W., Qu S. Extracellular vesicles in atherosclerosis. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2019;495:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2019.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sluijter J.P.G., Davidson S.M., Boulanger C.M., Buzas E.I., de Kleijn D.P.V., Engel F.B., Giricz Z., Hausenloy D.J., Kishore R., Lecour S., et al. Extracellular vesicles in diagnostics and therapy of the ischaemic heart: Position paper from the working group on cellular biology of the heart of the european society of cardiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018;114:19–34. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Niel G., D'Angelo G., Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018;19:213–228. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinha S., Hoshino D., Hong N.H., Kirkbride K.C., Grega-Larson N.E., Seiki M., Tyska M.J., Weaver A.M. Cortactin promotes exosome secretion by controlling branched actin dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 2016;214:197–213. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201601025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clark E.S., Whigham A.S., Yarbrough W.G., Weaver A.M. Cortactin is an essential regulator of matrix metalloproteinase secretion and extracellular matrix degradation in invadopodia. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4227–4235. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiesner C., El Azzouzi K., Linder S. A specific subset of rabgtpases controls cell surface exposure of MT1-MMP, extracellular matrix degradation and three-dimensional invasion of macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 2013;126:2820–2833. doi: 10.1242/jcs.122358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bachmann A., Straube A. Kinesins in cell migration. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015;43:79–83. doi: 10.1042/BST20140280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clancy J.W., Sedgwick A., Rosse C., Muralidharan-Chari V., Raposo G., Method M., Chavrier P., D'Souza-Schorey C. Regulated delivery of molecular cargo to invasive tumour-derived microvesicles. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6919. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nawaz M., Shah N., Zanetti B.R., Maugeri M., Silvestre R.N., Fatima F., Neder L., Valadi H. Extracellular vesicles and matrix remodeling enzymes: The emerging roles in extracellular matrix remodeling, progression of diseases and tissue repair. Cells. 2018;7:167. doi: 10.3390/cells7100167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bobryshev Y.V., Killingsworth M.C., Orekhov A.N. Increased shedding of microvesicles from intimal smooth muscle cells in athero-prone areas of the human aorta: Implications for understanding of the predisease stage. Pathobiology. 2013;80:24–31. doi: 10.1159/000339430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taraboletti G., D'Ascenzo S., Borsotti P., Giavazzi R., Pavan A., Dolo V. Shedding of the matrix metalloproteinases mmp-2, mmp-9, and mt1-mmp as membrane vesicle-associated components by endothelial cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2002;160:673–680. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64887-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lozito T.P., Tuan R.S. Endothelial cell microparticles act as centers of matrix metalloproteinsase-2 (MMP-2) activation and vascular matrix remodeling. J. Cell Physiol. 2012;227:534–549. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laghezza Masci V., Taddei A.R., Gambellini G., Giorgi F., Fausto A.M. Microvesicles shed from fibroblasts act as metalloproteinase carriers in a 3-d collagen matrix. J. Circ. Biomark. 2016;5:1849454416663660. doi: 10.1177/1849454416663660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreno P.R., Purushothaman K.R., Fuster V., Echeverri D., Truszczynska H., Sharma S.K., Badimon J.J., O'Connor W.N. Plaque neovascularization is increased in ruptured atherosclerotic lesions of human aorta: Implications for plaque vulnerability. Circulation. 2004;110:2032–2038. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143233.87854.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimoda M., Khokha R. Metalloproteinases in extracellular vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2017;1864:1989–2000. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng X.W., Song H., Sasaki T., Hu L., Inoue A., Bando Y.K., Shi G.P., Kuzuya M., Okumura K., Murohara T. Angiotensin type 1 receptor blocker reduces intimal neovascularization and plaque growth in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Hypertension. 2011;57:981–989. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Badimon L., Suades R., Arderiu G., Pena E., Chiva-Blanch G., Padro T. Microvesicles in atherosclerosis and angiogenesis: From bench to bedside and reverse. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2017;4:77. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2017.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bakhshian Nik A., Hutcheson J.D., Aikawa E. Extracellular vesicles as mediators of cardiovascular calcification. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2017;4:78. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2017.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu R., Gao W., Yao K., Ge J. Roles of exosomes derived from immune cells in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:648. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bailey G., Meadows J., Morrison A.R. Imaging atherosclerotic plaque calcification: Translating biology. Curr. Atheroscler Rep. 2016;18:51. doi: 10.1007/s11883-016-0601-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kapustin A.N., Shanahan C.M. Emerging roles for vascular smooth muscle cell exosomes in calcification and coagulation. J. Physiol. 2016;594:2905–2914. doi: 10.1113/JP271340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu X. The role of exosomes and exosome-derived micrornas in atherosclerosis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017;23:6182–6193. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666170413125507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alique M., Ramirez-Carracedo R., Bodega G., Carracedo J., Ramirez R. Senescent microvesicles: A novel advance in molecular mechanisms of atherosclerotic calcification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:2003. doi: 10.3390/ijms19072003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newby A.C. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition therapy for vascular diseases. Vascul Pharmacol. 2012;56:232–244. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cerisano G., Buonamici P., Valenti R., Sciagra R., Raspanti S., Santini A., Carrabba N., Dovellini E.V., Romito R., Pupi A., et al. Early short-term doxycycline therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction and left ventricular dysfunction to prevent the ominous progression to adverse remodelling: The tiptop trial. Eur. Heart J. 2014;35:184–191. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schulze C.J., Castro M.M., Kandasamy A.D., Cena J., Bryden C., Wang S.H., Koshal A., Tsuyuki R.T., Finegan B.A., Schulz R. Doxycycline reduces cardiac matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity but does not ameliorate myocardial dysfunction during reperfusion in coronary artery bypass patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Crit. Care Med. 2013;41:2512–2520. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318292373c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bench T.J., Jeremias A., Brown D.L. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition with tetracyclines for the treatment of coronary artery disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2011;64:561–566. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodriguez-Granillo G.A., Rodriguez-Granillo A., Milei J. Effect of doxycycline on atherosclerosis: From bench to bedside. Recent Pat. Cardiovasc. Drug Discov. 2011;6:42–54. doi: 10.2174/157489011794578419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kormi I., Alfakry H., Tervahartiala T., Pussinen P.J., Sinisalo J., Sorsa T. The effect of prolonged systemic doxycycline therapy on serum tissue degrading proteinases in coronary bypass patients: A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Inflamm Res. 2014;63:329–334. doi: 10.1007/s00011-013-0704-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rival Y., Beneteau N., Chapuis V., Taillandier T., Lestienne F., Dupont-Passelaigue E., Patoiseau J.F., Colpaert F.C., Junquero D. Cardiovascular drugs inhibit MMP-9 activity from human THP-1 macrophages. DNA Cell Biol. 2004;23:283–292. doi: 10.1089/104454904323090912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cevik C., Otahbachi M., Nugent K., Warangkana C., Meyerrose G. Effect of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibition on serum matrix metalloproteinase-13 and tissue inhibitor matrix metalloproteinase-1 levels as a sign of plaque stabilization. J. Cardiovasc. Med. (Hagerstown) 2008;9:1274–1278. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e328316912f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dorecka M., Francuz T., Garczorz W., Siemianowicz K., Romaniuk W. The influence of elastin degradation products, glucose and atorvastatin on metalloproteinase-1, -2, -9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1, -2, -3 expression in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2014;61:265–270. doi: 10.18388/abp.2014_1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luan Z., Chase A.J., Newby A.C. Statins inhibit secretion of metalloproteinases-1, -2, -3, and -9 from vascular smooth muscle cells and macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc Biol. 2003;23:769–775. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000068646.76823.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Komukai K., Kubo T., Kitabata H., Matsuo Y., Ozaki Y., Takarada S., Okumoto Y., Shiono Y., Orii M., Shimamura K., et al. Effect of atorvastatin therapy on fibrous cap thickness in coronary atherosclerotic plaque as assessed by optical coherence tomography: The easy-fit study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;64:2207–2217. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu H.L., Yang Y., Yang S.L., Luo J.P., Li H., Jing L.M., Shen Z.Q. Administration of a loading dose of atorvastatin before percutaneous coronary intervention prevents inflammation and reduces myocardial injury in stemi patients: A randomized clinical study. Clin. Ther. 2013;35:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li D.D., Pang H.G., Song J.N., Huang H., Zhang M., Zhao Y.L., Sun P., Zhang B.F., Ma X.D. The rapid lipopolysaccharide-induced release of matrix metalloproteinases 9 is suppressed by simvastatin. Cell Biol. Int. 2015;39:788–798. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ichihara S., Noda A., Nagata K., Obata K., Xu J., Ichihara G., Oikawa S., Kawanishi S., Yamada Y., Yokota M. Pravastatin increases survival and suppresses an increase in myocardial matrix metalloproteinase activity in a rat model of heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;69:726–735. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guo Z., Sun X., He Z., Jiang Y., Zhang X. Role of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in apoptosis of hippocampal neurons in rats during early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurol. Sci. 2010;31:143–149. doi: 10.1007/s10072-009-0192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang X., Zhao X., Li L., Yao H., Jiang Y., Zhang J. Effects of combination of ezetimibe and rosuvastatin on coronary artery plaque in patients with coronary heart disease. Heart Lung Circ. 2016;25:459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sapienza P., Mingoli A., Borrelli V., Brachini G., Biacchi D., Sterpetti A.V., Grande R., Serra R., Tartaglia E. Inflammatory biomarkers, vascular procedures of lower limbs, and wound healing. Int. Wound J. 2019;16:716–723. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sapienza P., Mingoli A., Borrelli V., Grande R., Sterpetti A.V., Biacchi D., Ferrer C., Rubino P., Serra R., Tartaglia E. Different inflammatory cytokines release after open and endovascular reconstructions influences wound healing. Int. Wound J. 2019;16:1034–1044. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolf D., Ley K. Immunity and inflammation in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2019;124:315–327. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Olejarz W., Lacheta D., Gluszko A., Migacz E., Kukwa W., Szczepanski M.J., Tomaszewski P., Nowicka G. RAGE and TLRs as key targets for antiatherosclerotic therapy. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018;2018:7675286. doi: 10.1155/2018/7675286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Olejarz W., Gluszko A., Cyran A., Bednarek-Rajewska K., Proczka R., Smith D.F., Ishman S.L., Migacz E., Kukwa W. TLRs and RAGE are elevated in carotid plaques from patients with moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Breath. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11325-020-02029-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu M.Y., Li C.J., Hou M.F., Chu P.Y. New insights into the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:2034. doi: 10.3390/ijms18102034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang X., Khalil R.A. Matrix metalloproteinases, vascular remodeling, and vascular disease. Adv. Pharmacol. 2018;81:241–330. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kowara M., Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska A., Opolski G., Wlodarski P. MicroRNA regulation of extracellular matrix components in the process of atherosclerotic plaque destabilization. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2017;44:711–718. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gistera A., Hansson G.K. The immunology of atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017;13:368–380. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Falk E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006;47:C7–C12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li A., Peng W., Xia X., Li R., Wang Y., Wei D. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition: A potential mechanism for atherosclerosis plaque progression and destabilization. DNA Cell Biol. 2017;36:883–891. doi: 10.1089/dna.2017.3779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nissinen L., Kahari V.M. Matrix metalloproteinases in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1840:2571–2580. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Watanabe R., Maeda T., Zhang H., Berry G.J., Zeisbrich M., Brockett R., Greenstein A.E., Tian L., Goronzy J.J., Weyand C.M. Mmp (matrix metalloprotease)-9-producing monocytes enable t cells to invade the vessel wall and cause vasculitis. Circ. Res. 2018;123:700–715. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Uzui H., Harpf A., Liu M., Doherty T.M., Shukla A., Chai N.N., Tripathi P.V., Jovinge S., Wilkin D.J., Asotra K., et al. Increased expression of membrane type 3-matrix metalloproteinase in human atherosclerotic plaque: Role of activated macrophages and inflammatory cytokines. Circulation. 2002;106:3024–3030. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000041433.94868.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Raffetto J.D., Khalil R.A. Matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in vascular remodeling and vascular disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008;75:346–359. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Di Gregoli K., George S.J., Jackson C.L., Newby A.C., Johnson J.L. Differential effects of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1 and TIMP-2 on atherosclerosis and monocyte/macrophage invasion. Cardiovasc. Res. 2016;109:318–330. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nam S.I., Yu G.I., Kim H.J., Park K.O., Chung J.H., Ha E., Shin D.H. A polymorphism at -1607 2g in the matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) increased risk of sudden deafness in korean population but not at -519a/g in mmp-1. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:171–175. doi: 10.1002/lary.21334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Akiba S., Kumazawa S., Yamaguchi H., Hontani N., Matsumoto T., Ikeda T., Oka M., Sato T. Acceleration of matrix metalloproteinase-1 production and activation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta in human coronary smooth muscle cells by oxidized ldl and 4-hydroxynonenal. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1763:797–804. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Newby A.C. Metalloproteinase production from macrophages—A perfect storm leading to atherosclerotic plaque rupture and myocardial infarction. Exp. Physiol. 2016;101:1327–1337. doi: 10.1113/EP085567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen Q., Wang Q., Zhu J., Xiao Q., Zhang L. Reactive oxygen species: Key regulators in vascular health and diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018;175:1279–1292. doi: 10.1111/bph.13828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Newby A.C. Metalloproteinase expression in monocytes and macrophages and its relationship to atherosclerotic plaque instability. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28:2108–2114. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.173898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Valentin F., Bueb J.L., Kieffer P., Tschirhart E., Atkinson J. Oxidative stress activates MMP-2 in cultured human coronary smooth muscle cells. Fundam Clin. Pharmacol. 2005;19:661–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2005.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ayuk S.M., Abrahamse H., Houreld N.N. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in diabetic wound healing in relation to photobiomodulation. J. Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:2897656. doi: 10.1155/2016/2897656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hernandez-Anzaldo S., Brglez V., Hemmeryckx B., Leung D., Filep J.G., Vance J.E., Vance D.E., Kassiri Z., Lijnen R.H., Lambeau G., et al. Novel role for matrix metalloproteinase 9 in modulation of cholesterol metabolism. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016;5:1–16. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Johnson J.L. Metalloproteinases in atherosclerosis. Eur J. Pharmacol. 2017;816:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.de Franciscis S., Serra R. Matrix metalloproteinases and endothelial dysfunction: The search for new prognostic markers and for new therapeutic targets for vascular wall imbalance. Thromb. Res. 2015;136:5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Carmona-Rivera C., Zhao W., Yalavarthi S., Kaplan M.J. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce endothelial dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus through the activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Ann. Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1417–1424. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Amato B., Compagna R., Amato M., Grande R., Butrico L., Rossi A., Naso A., Ruggiero M., de Franciscis S., Serra R. Adult vascular wall resident multipotent vascular stem cells, matrix metalloproteinases, and arterial aneurysms. Stem Cells Int. 2015;2015:434962. doi: 10.1155/2015/434962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Newby A.C. Dual role of matrix metalloproteinases (matrixins) in intimal thickening and atherosclerotic plaque rupture. Physiol. Rev. 2005;85:1–31. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00048.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Johnson J.L. Matrix metalloproteinases: Influence on smooth muscle cells and atherosclerotic plaque stability. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2007;5:265–282. doi: 10.1586/14779072.5.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang Z., Kong L., Kang J., Vaughn D.M., Bush G.D., Walding A.L., Grigorian A.A., Robinson J.S., Jr., Nakayama D.K. Interleukin-lbeta induces migration of rat arterial smooth muscle cells through a mechanism involving increased matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity. J. Surg. Res. 2011;169:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Auge N., Maupas-Schwalm F., Elbaz M., Thiers J.C., Waysbort A., Itohara S., Krell H.W., Salvayre R., Negre-Salvayre A. Role for matrix metalloproteinase-2 in oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced activation of the sphingomyelin/ceramide pathway and smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circulation. 2004;110:571–578. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136995.83451.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Li H., Liang J., Castrillon D.H., DePinho R.A., Olson E.N., Liu Z.P. Foxo4 regulates tumor necrosis factor alpha-directed smooth muscle cell migration by activating matrix metalloproteinase 9 gene transcription. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;27:2676–2686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01748-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Guo R.W., Yang L.X., Wang H., Liu B., Wang L. Angiotensin ii induces matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression via a nuclear factor-kappab-dependent pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. Regul. Pept. 2008;147:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dwivedi A., Slater S.C., George S.J. MMP-9 and -12 cause n-cadherin shedding and thereby beta-catenin signalling and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009;81:178–186. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Orbe J., Montero I., Rodriguez J.A., Beloqui O., Roncal C., Paramo J.A. Independent association of matrix metalloproteinase-10, cardiovascular risk factors and subclinical atherosclerosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007;5:91–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu J., Khalil R.A. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as investigational and therapeutic tools in unrestrained tissue remodeling and pathological disorders. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2017;148:355–420. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fischer T., Senn N., Riedl R. Design and structural evolution of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. Chemistry. 2019;25:7960–7980. doi: 10.1002/chem.201805361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mott J.D., Werb Z. Regulation of matrix biology by matrix metalloproteinases. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chistiakov D.A., Myasoedova V.A., Melnichenko A.A., Grechko A.V., Orekhov A.N. Calcifying matrix vesicles and atherosclerosis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017;2017:7463590. doi: 10.1155/2017/7463590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu Y., Zhang H., Yan L., Du W., Zhang M., Chen H., Zhang L., Li G., Li J., Dong Y., et al. MMP-2 and MMP-9 contribute to the angiogenic effect produced by hypoxia/15-hete in pulmonary endothelial cells. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2018;121:36–50. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Butoi E., Gan A.M., Tucureanu M.M., Stan D., Macarie R.D., Constantinescu C., Calin M., Simionescu M., Manduteanu I. Cross-talk between macrophages and smooth muscle cells impairs collagen and metalloprotease synthesis and promotes angiogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1863:1568–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kalampogias A., Siasos G., Oikonomou E., Tsalamandris S., Mourouzis K., Tsigkou V., Vavuranakis M., Zografos T., Deftereos S., Stefanadis C., et al. Basic mechanisms in atherosclerosis: The role of calcium. Med. Chem. 2016;12:103–113. doi: 10.2174/1573406411666150928111446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gaubatz J.W., Ballantyne C.M., Wasserman B.A., He M., Chambless L.E., Boerwinkle E., Hoogeveen R.C. Association of circulating matrix metalloproteinases with carotid artery characteristics: The atherosclerosis risk in communities carotid mri study. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1034–1042. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.195370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sasaki T., Nakamura K., Sasada K., Okada S., Cheng X.W., Suzuki T., Murohara T., Sato K., Kuzuya M. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 deficiency impairs aortic atherosclerotic calcification in apoe-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2013;227:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rattazzi M., Bennett B.J., Bea F., Kirk E.A., Ricks J.L., Speer M., Schwartz S.M., Giachelli C.M., Rosenfeld M.E. Calcification of advanced atherosclerotic lesions in the innominate arteries of apoe-deficient mice: Potential role of chondrocyte-like cells. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1420–1425. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000166600.58468.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gresele P., Falcinelli E., Sebastiano M., Momi S. Matrix metalloproteinases and platelet function. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2017;147:133–165. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sebastiano M., Momi S., Falcinelli E., Bury L., Hoylaerts M.F., Gresele P. A novel mechanism regulating human platelet activation by mmp-2-mediated par1 biased signaling. Blood. 2017;129:883–895. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-06-724245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Purroy A., Roncal C., Orbe J., Meilhac O., Belzunce M., Zalba G., Villa-Bellosta R., Andres V., Parks W.C., Paramo J.A., et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-10 deficiency delays atherosclerosis progression and plaque calcification. Atherosclerosis. 2018;278:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Newby A.C. Metalloproteinases and vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2007;17:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Montero I., Orbe J., Varo N., Beloqui O., Monreal J.I., Rodriguez J.A., Diez J., Libby P., Paramo J.A. C-reactive protein induces matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -10 in human endothelial cells: Implications for clinical and subclinical atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006;47:1369–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lemaitre V., O'Byrne T.K., Borczuk A.C., Okada Y., Tall A.R., D'Armiento J. Apoe knockout mice expressing human matrix metalloproteinase-1 in macrophages have less advanced atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2001;107:1227–1234. doi: 10.1172/JCI9626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hojo Y., Ikeda U., Takahashi M., Sakata Y., Takizawa T., Okada K., Saito T., Shimada K. Matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression by interaction between monocytes and vascular endothelial cells. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1459–1468. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sukhova G.K., Schonbeck U., Rabkin E., Schoen F.J., Poole A.R., Billinghurst R.C., Libby P. Evidence for increased collagenolysis by interstitial collagenases-1 and -3 in vulnerable human atheromatous plaques. Circulation. 1999;99:2503–2509. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.19.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Molloy K.J., Thompson M.M., Jones J.L., Schwalbe E.C., Bell P.R., Naylor A.R., Loftus I.M. Unstable carotid plaques exhibit raised matrix metalloproteinase-8 activity. Circulation. 2004;110:337–343. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000135588.65188.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lee H.S., Noh J.Y., Shin O.S., Song J.Y., Cheong H.J., Kim W.J. Matrix metalloproteinase-13 in atherosclerotic plaque is increased by influenza a virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;221:256–266. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Levkau B., Kenagy R.D., Karsan A., Weitkamp B., Clowes A.W., Ross R., Raines E.W. Activation of metalloproteinases and their association with integrins: An auxiliary apoptotic pathway in human endothelial cells. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:1360–1367. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Williams H., Johnson J.L., Jackson C.L., White S.J., George S.J. MMP-7 mediates cleavage of n-cadherin and promotes smooth muscle cell apoptosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010;87:137–146. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Stoneman V.E., Bennett M.R. Role of apoptosis in atherosclerosis and its therapeutic implications. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2004;107:343–354. doi: 10.1042/CS20040086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Inoue S., Nakazawa T., Cho A., Dastvan F., Shilling D., Daum G., Reidy M. Regulation of arterial lesions in mice depends on differential smooth muscle cell migration: A role for sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors. J. Vasc. Surg. 2007;46:756–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Rauch I., Iglseder B., Paulweber B., Ladurner G., Strasser P. MMP-9 haplotypes and carotid artery atherosclerosis: An association study introducing a novel multicolour multiplex realtime pcr protocol. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2008;38:24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Choi E.T., Collins E.T., Marine L.A., Uberti M.G., Uchida H., Leidenfrost J.E., Khan M.F., Boc K.P., Abendschein D.R., Parks W.C. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 modulation by resident arterial cells is responsible for injury-induced accelerated atherosclerotic plaque development in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1020–1025. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000161275.82687.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Su W., Gao F., Lu J., Wu W., Zhou G., Lu S. Levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 mrnas in patients with primary hypertension or hypertension-induced atherosclerosis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2012;40:986–994. doi: 10.1177/147323001204000317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Shah P.K., Falk E., Badimon J.J., Fernandez-Ortiz A., Mailhac A., Villareal-Levy G., Fallon J.T., Regnstrom J., Fuster V. Human monocyte-derived macrophages induce collagen breakdown in fibrous caps of atherosclerotic plaques. Potential role of matrix-degrading metalloproteinases and implications for plaque rupture. Circulation. 1995;92:1565–1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Nenseter M.S., Narverud I., Graesdal A., Bogsrud M.P., Halvorsen B., Ose L., Aukrust P., Holven K.B. Elevated serum MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: Effects of LDL-apheresis. Cytokine. 2013;61:194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gu C., Wang F., Zhao Z., Wang H., Cong X., Chen X. Lysophosphatidic acid is associated with atherosclerotic plaque instability by regulating nf-kappab dependent matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression via LPA2 in macrophages. Front. Physiol. 2017;8:266. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Giaginis C., Zira A., Katsargyris A., Klonaris C., Theocharis S. Clinical implication of plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) concentrations in patients with advanced carotid atherosclerosis. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2010;48:1035–1041. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2010.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Serra R., Grande R., Montemurro R., Butrico L., Calio F.G., Mastrangelo D., Scarcello E., Gallelli L., Buffone G., de Franciscis S. The role of matrix metalloproteinases and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in central and peripheral arterial aneurysms. Surgery. 2015;157:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sivalingam Z., Larsen S.B., Grove E.L., Hvas A.M., Kristensen S.D., Magnusson N.E. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a risk marker in cardiovascular disease. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2017;56:5–18. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2017-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Chong J.J.H., Prince R.L., Thompson P.L., Thavapalachandran S., Ooi E., Devine A., Lim E.E.M., Byrnes E., Wong G., Lim W.H., et al. Association between plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and cardiac disease hospitalizations and deaths in older women. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011028. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Shah P.K. Biomarkers of plaque instability. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2014;16:547. doi: 10.1007/s11886-014-0547-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Mangge H., Almer G. Immune-mediated inflammation in vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques. Molecules. 2019;24:3072. doi: 10.3390/molecules24173072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Romero J.R., Vasan R.S., Beiser A.S., Polak J.F., Benjamin E.J., Wolf P.A., Seshadri S. Association of carotid artery atherosclerosis with circulating biomarkers of extracellular matrix remodeling: The framingham offspring study. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2008;17:412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ye S., Gale C.R., Martyn C.N. Variation in the matrix metalloproteinase-1 gene and risk of coronary heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 2003;24:1668–1671. doi: 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Huang X.Y., Han L.Y., Huang X.D., Guan C.H., Mao X.L., Ye Z.S. Association of matrix metalloproteinase-1 and matrix metalloproteinase-3 gene variants with ischemic stroke and its subtype. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2017;26:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Sapienza P., di Marzo L., Borrelli V., Sterpetti A.V., Mingoli A., Cresti S., Cavallaro A. Metalloproteinases and their inhibitors are markers of plaque instability. Surgery. 2005;137:355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]