Hepatitis B Viral Protein HBx and the Molecular Mechanisms Modulating the Hallmarks of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Review (original) (raw)

Abstract

With 296 million cases estimated worldwide, chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the most common risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HBV-encoded oncogene X protein (HBx), a key multifunctional regulatory protein, drives viral replication and interferes with several cellular signalling pathways that drive virus-associated hepatocarcinogenesis. This review article provides a comprehensive overview of the role of HBx in modulating the various hallmarks of HCC by supporting tumour initiation, progression, invasion and metastasis. Understanding HBx-mediated dimensions of complexity in driving liver malignancies could provide the key to unlocking novel and repurposed combinatorial therapies to combat HCC.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, HBx protein, hepatocellular carcinoma, cancer hallmarks, therapeutics

1. Introduction

Despite the availability of hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccines, the worldwide incidence of hepatitis B cases remain to be an estimated 296 million, with over 1.5 million new infections occurring annually [1]. Prolonged chronic inflammation and tissue damage associated with HBV often lead to fibrosis/cirrhosis and eventually hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common form of liver cancer [2]. According to the latest epidemiological data from Globocan 2020 report, newly diagnosed liver cancer cases account for over 900,000 cancer cases annually (4.7% of all cancers) and there are approximately 830,000 deaths linked to HCC annually [3]. Geographic variations associated with HBV infection show 70–80% hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroprevalence in South East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, linked to high levels of HBV driven HCC incidence, whereas less than 2% HBsAg seroprevalence is observed in Western Europe, America and Australia with a similar low level of HBV-driven HCC [4].

HBV is a small DNA virus, a prototype of Hepadnaviridae family of viruses, with a 3.2 kilobases circular and partially double stranded genome. During replication, the partially dsDNA genome is gap repaired and transcribed into a full length pre-genomic RNA which is subsequently reverse transcribed by a viral polymerase with RT activity. The genome encodes four overlapping open reading frames (ORF) encoding envelope protein (pre-S1/pre-S2), core protein (pre-C/C), viral polymerase and X protein (HBx) [5]. While the exact molecular mechanisms driving HBV-induced HCC have been poorly defined, it has been speculated that virus-host genome integration, prolonged inflammation aided host immune response and cellular signal transduction pathways altered by the viral regulatory protein HBx could play a crucial role in the progression of liver tumorigenesis [6,7,8].

HBx gene, the smallest ORF of the HBV genome, encodes a 154-amino acid regulatory protein of molecular weight 17 kDa. It is found in all mammalian Hepadnaviruses, termed Orthohepadnaviruses, but interestingly not in avian species which are infected by Avihepadnaviruses. HBx proteins from different species contain conserved regions, helical structures in the amino- and carboxy-terminal as well as a coil-to-coil motif with several regions with known functional domains [9]. Attempts at crystallizing the protein have been proven futile, so no detailed structural information is available. HBx forms homodimers via disulfide bonds and acetylation [10]. It received its name, X protein, due to the lack of sequence homology to any existing protein. Intracellular localization studies based on HBV patient-derived liver biopsies show that HBx predominantly accumulates in the cytoplasm when highly expressed, whereas low expression leads to localization primarily in the nucleus [11,12].

While the precise functions of HBx are not fully understood, it has been proposed that HBx is multifunctional owing to its negative regulatory/anti-apoptotic N terminal and transactivator C terminal in addition to being the only regulatory protein encoded by the virus. HBx is key to driving HBV viral infection via governing cellular and viral promoters and enhancers, driving promiscuous transactivation, through protein–protein interactions and, without directly binding to DNA [13,14]. Given its primary localization in the cytoplasm, HBx is able to modulate several signal transduction pathways such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB), rat sarcoma virus (Ras), rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (Raf), janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT), focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and kinase C signalling cascades. [15,16]. Furthermore, HBx has also been implicated in cell cycle regulation, calcium signalling, DNA repair and regulation of apoptosis [17]. The potential role of HBx in hepatocarginogenesis was apparent with the development of HCC in the natural hosts of HBx encoding Orthohepadnaviruses, woodchucks, squirrel monkeys and humans, whereas there is no evidence of liver tumourigenesis for infection with Avihepadnaviruses which lack the HBx protein [18]. In vitro studies have shown that prolonged expression of HBx induces cellular transformation of rodent hepatocytes, while the presence of integrated HBx gene in the chromosomal DNA has been frequently detected in patients diagnosed with HCC [19,20].

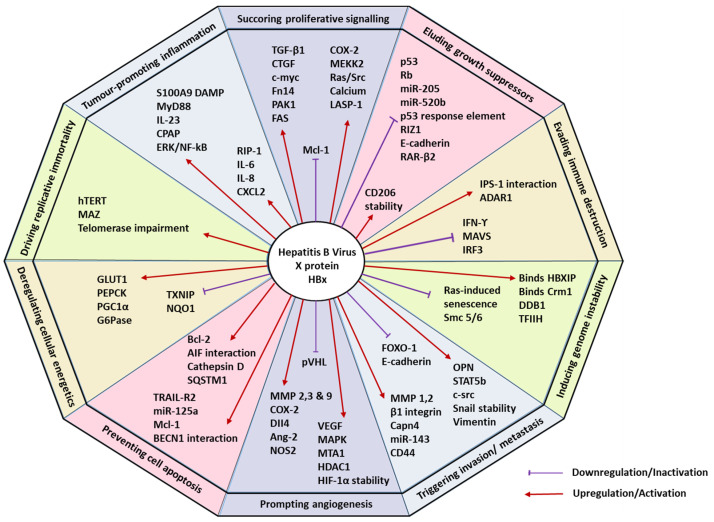

The multifunctional nature of HBx implies its involvement in altering several cellular mechanisms by hijacking the host cell homeostasis and provoking tumorigenic traits capable of inducing HCC. Such complex and distinct traits that trigger tumorigenesis and metastatic propagation, in general, have been organized into 10 major hallmarks of cancer by Hanahan and Weinberg [21,22]. These hallmarks are sustaining proliferative signalling, eluding growth suppressors, evading immune destruction, facilitating replicative immortality, aiding in tumour-promoting inflammation, triggering invasion and metastasis, prompting angiogenesis, inducing genomic instability, preventing cell apoptosis, and deregulating cellular energetics [22]. This article discusses the involvement of HBx in modulating the different hallmarks of HCC, highlighting the potential therapeutic implications. Table 1 and Figure 1 provide a summary and overview of HBx-mediated hallmarks of HCC.

Table 1.

Key molecular mechanisms regulated by hepatitis B Virus X protein that drive hallmarks of hepatocellular carcinoma.

| HCC Hallmark | HBx Activity | Study Design | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustaining proliferative signalling | Activates stellate cells and elevates transforming-growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) | In vitro co-culture with LX-2 cells and stable QSG7701-HBx cell line | Guo et al. [23] |

| Five-fold elevated expression of c-myc | In vitro human hepatoma cell lines Huh7 and IHHs and in vivo X15–myc transgenic mouse modelIn vivo HBx-transgenic mice with c-myc driven by woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) | Shukla & Kumar et al.Terradillos et al. [24,25] | |

| HBx-SMYD3 interaction, guided by the downstream target gene c-myc | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 cells and HBV containing HepG2.2.15 cells | Yang et al. [26] | |

| Enhanced expression of fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14 (fn14) | In vitro human fibroblasts and HCC cells and In vivo HBx-transgenic mice. | Feng et al. [27] | |

| Disrupts cell cycle progression by upregulating p21 and p27 | In vivo pX expressing primary mouse hepatocytes | Qiao et al. [28] | |

| Elevates serine/threonine p21 activated kinase 1 (PAK1) | In vivo tumour xenografts in mice and in vitro human hepatoma cells with pHBV1.3 | Xu et al. [29] | |

| Upregulates transcription of fatty acid synthase (FAS), mediated by 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) | In vitro HBx-expressing human hepatoma HepG2 and H7402 cells | Wang et al. [30] | |

| Upregulates cyclooxygenase (COX-2) and MERK/ERK kinase 2 (MEKK2) | In vitro HBx-expressing L-O2 and H7402 cell lines. | Shan et al. [31] | |

| Suppressed anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1 | In vitro Chang liver cells transiently transfected with HBx (CHL-X) | Lee et al. [32] | |

| Activates Ras and Src kinase | In vitro human hepatoma Hep3B cells with transiently transfected HA-tagged HBx | Noh et al. [33] | |

| Enhances cytosolic calcium levels | In vitro HepG2 cells transfected with full length HBx | Yang & Bouchard, 2012 [34] | |

| Elevates adhesion protein LASP-1 via PI3K pathway | In vitro HBx stably transfected HepG2 and Huh-7 cells | Tang et al. [35] | |

| Eluding growth suppressors | Partial sequestration of p53 causing G1 arrest | In vitro HBx expressing human fibroblasts, HepG2 cells and liver tissue from patients | Elmore et al. [36] |

| Inhibition of p53 response element | In vitro HBx transiently transfected human Calu-6 cells | Truant et al. [37] | |

| Inactivates Rb gene promoter | In vitro HepG2 and Hela cells | Choi et al. [38] | |

| Confers stability to replication initiator CDC6 | In vitro HBx-expressing human hepatoma cells Huh7, HepG2.In vivo X15-myc transgenic mouse model | Pandey & Kumar, 2012 [39] | |

| miR-205 inhibition via promoter hypermethylation | In vitro HBx-expressing hepatoma cell lines and In vivo HBx- transgenic mice and patient samples | Zhang et al. [40] | |

| Controls miR-520b and hepatitis B X-interacting protein (HBXIP) | In vitro HBx-expressing human hepatoma cells and In vivo nude mice transplantation and patient samples | Zhang et al. [41] | |

| Represses RIZ1 via hypermethylation | In vitro HBx-expressing human hepatoma cells and patient samples | Zhao et al. [42] | |

| Suppresses E-cadherin tumour suppressor | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 cell line | Lee et al. [43] | |

| Hypermethylates p16 via pRb-E2f pathway | HBV-HCC patient and tissue specimens | Zhu et al. [44] | |

| Downregulates retinoic acid receptor-beta 2 (RAR-β2) | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 cells | Jung et al. [45] | |

| Resisting cell death | Pro-apoptosis | ||

| Induces the expression of TRAIL-R2 (DR5) | In vitro HBx-expressing Huh-7 cells | Kong et al. [46] | |

| Upregulation of miR-125a | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 and LO-2 liver cells | Zhang et al. [47] | |

| Anti-apoptosis | |||

| Induces myeloid cell leukemia-1 (Mcl-1) and B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) | In vitro HBx-expressing HPCs (HP14.5) cells | Shen et al. [48] | |

| Interacts with apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and AIF-homologue mitochondrian-associated inducer of death (AMID) | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 cells | Liu et al. [49] | |

| Autophagy | |||

| Upregulating SQSTM1 and lysosomal aspartic protease cathepsin D | In vitro HBx-expressing Huh-7 cells and human tissue specimens | Liu et al. [50] | |

| Interacts with BECN1 (Beclin 1) | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 and SK-Hep-1 | Son et al. [51] | |

| PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 cells | Wang et al. [52] | |

| Facilitating replicative immortality | Activates human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 and QBC939 cell lines | Zhang et al. Qu et al. [53,54] |

| MAZ binding aided telomerase impairment | In vitro HBx-expressing H7402 hepatoma cells | Su et al. [55] | |

| Prompting angiogenesis | Upregulates VEGF mRNA expression and stabilizes HIF-1α | In vitro HBx-expressing human HepG2 and mouse Hepa 1–6 HCC cell linesIn vitro ChangX-34 and HBx transgenic mice modelIn vitro HBx-expressing HEK293 cells | Lee et al.Moon et al.Yun et al. [56,57,58] |

| Mitigates binding of von Hippel-Lindau (pVHL) | In vitro HBx-expressing HEK293 cells | Moon et al. [58] | |

| Activates p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) | In vitro HBx-expressing human hepatoma cell lines and HBx transgenic mice model | Yoo et al. [59] | |

| Upregulates metastasis-associated protein 1 (MTA1) and histone deacetylase (HDAC1) | In vitro Chang X-34 cells, HBx transgenic mice and patient samples | Yoo et al. [60] | |

| Overexpresses matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) 2,3 and 9 | In vitro HBx-expressing human Chang cell lines and murine AML-12 liver cell lineIn vitro HBx-expressing human hepatoma cell linesIn vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 cell line and xenograft mice model | Lara-Pezzi et al. [61] Yu et al. [62] Liu et al. [63] | |

| Induces COX-2 enzyme | In vitro HBx-expressing Hep3B cell line and patient samples | Cheng et al. [64] | |

| Mediates Dll4 upregulation | In vitro HBx-expressing human hepatoma cell lines and HCC patient samples | Kongkavitoon et al. [65] | |

| Stimulates Ang-2 isoform | In vitro HBx-expressing Chang cell line and rat hepatic stellate cells CFSC-2G, THP1 promonocyte cell line and patient and tissue specimens | Sanz-Cameno et al. [66] | |

| Induces nitrogen oxide synthase 2 (NOS2) | In vitro HBV-expressing HepG2 and HepG2.2.15 cell lines and patient and tissue specimens | Majano et al. [67] | |

| Triggering invasion and metastasis | Promotes production of MMPs 1 and 2 and disrupts adherens junctions | In vitro HBx-expressing human Chang cell lines and murine AML-12 liver cell lineHCC patient tissue specimens | Lara-Pezzi et al. [61] Giannelli et al. [68] |

| Modifies α integrin subunits and activates β1 integrin subunits | In vitro HBx-expressing Chang cell line | Lara-Pezzi et al. [69] | |

| Upregulation of Capn4 via nuclear factor-kB/p65 | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 and H7402 cell lines | Zhang et al. [70] | |

| Promotes tumour stemness via impaired FOXO1 and β-catenin nuclear translocation | In vitro HBx-expressing cell lines and In vivo tumour xenograft mice model | Lin et al. [71] | |

| Elevates miRNA-143 (miR-143) | In vitro HepG2 and Huh7 cell lines and In vivo HBx transgenic mice and patient tissue samples | Zhang et al. [72] | |

| Activates cell-surface adhesion molecule CD44 | In vitro HBx expressing Chang cell line | Lara-Pezzi et al. [73] | |

| Activates ossteopontin (OPN) through 5-LOX | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 cell line | Zhang et al. [74] | |

| Activates (STAT5b) and c-Src proto-oncogene | In vitro HBx-expressing Huh7 and HCC patient samplesIn vitro HBx-expressing SMMC-7721 cell line | Lee et al. [75]Yang et al. [76] | |

| Stabilizes Snail protein | In vitro human hepatoma Huh7 and Chang cell lines and patient samples | Liu et al. [77] | |

| Induces expression of vimentin | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 and Huh7 cell lines and patient samples | You et al. [78] | |

| Represses E-cadherin | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 cell line and patient samples | Arzumanyan et al. [79] | |

| Evading immune destruction | Induces apoptosis in HBV-specific CD8+ T cells | In vitro HBx-expressing primary hepatocytes | Lee et al. [80] |

| Interacts with IPS-1 and inhibits interferon-ϒ | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 and In vivo HBx transgenic mice | Kumar et al. [81] | |

| Inhibits IRF3 and associations between VISA and RIG-1/MDA5 | In vitro BHK and HEK 293 cell lines | Wang et al. [82] | |

| Degradation of MAVS via Lys(136) ubiquitination | In vitro human hepatoma cell lines, In vivo HBx knock-in mice model and liver tumour samples | Wei et al. [83] | |

| Promotes RNA adenosine deaminase ADAR1 | In vitro HepG2.2.15 and NTCP-expressing HepG2 and Huh7, In vivo mice model | Wang et al. [84] | |

| Tumour-promoting inflammation | Induces RIP-1 and aids in activation of cytokines IL-6, IL-8 and CXCL2 | In vitro HBx-expressing LO-2 hepatocytes | Xie & Huang [85] |

| Induces S100A9 DAMP protein | In vitro HBx-expressing human hepatoma cell lines, In vivo HBx transgenic mice model and patient samples | Duan et al. [86] | |

| Activates signal transduction adaptor MyD88, including, IRAK-1, NF-kB and ERKs/p38 | In vitro HBx-expressing human hepatic L02 cells and human hepatoma SMMC-7721 | Xiang et al. [87] | |

| Activates ERK/NF-kB pathway and IL-23 subunits | In vitro HepG2 and Huh7, normal hepatocyte Chang liver and HL-7702, and HepG2.2.15 cells lines and patient samples | Xia et al. [88] | |

| Interacts with CPAP regulator | In vitro HBx- and NTCP-expressing human hepatoma cell lines and In vivo xenograft mice model | Yen et al. [89] | |

| Inducing genomic instability | Binds HBXIP | In vitro Hela and mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cell lines and In vivo liver regeneration mice model | Fujii et al. [90] |

| Binds Crm1 with the NES domain on HBx | In vitro HBx-expressing Hep3B and primary human fibroblast cell lines | Forgues et al. [91] | |

| Binds DDB proteins | In vitro wild-type or mutant HBx-expressing HepG2 cell lines | Becker et al. [92] | |

| Disrupts Ras-induced senescence | In vitro HBx-expressing human primary fibroblasts BJ and TIG3 cell lines and In vivo mice model | Oishi et al. [93] | |

| Stimulates DNA helicase catalytic activity of TFIIH subunits | In vitro HBx-expressing Hela cells and yeast model | Qadri et al. [94] | |

| Degradation of Smc 5/6 | In vitro wild type and mutant HBx-expressing HepG2, HepAD38, HepG2-NTCP cell lines | Murphy et al. [95] | |

| Deregulating cellular energetics | Downregulates TXNIP protein | In vitro HBx-expressing MIHA and LO-2 cell lines, In vivo mice model and HCC patient samples | Zhang et al. [96] |

| Elevates expression of GLUT1 | In vitro human hepatoma HepG2 cell line and HCC patient samples | Zhou et al. [97] | |

| Overexpression of PEPCK, PGC1α, and G6Pase | In vitro HBx-expressing HepG2 cell line, In vivo HBx transgenic mice and HCC patient samples | Shin et al. [98] | |

| Downregulates NQO1 enzyme | In vitro HBx-expressing Huh7 cell line | Jung et al. [99] |

Figure 1.

Hallmarks of hepatocellular carcinoma modulated by hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx). Numerous liver tumorigenesis-driving hallmarks influence the downstream cellular mechanisms by sustaining proliferative signalling, eluding growth suppressors, evading immune destruction, facilitating replicative immortality, aiding in tumour-promoting inflammation, triggering invasion and metastasis, prompting angiogenesis, inducing genome instability, preventing cell apoptosis, and deregulating cellular energetics.

2. Sustaining Proliferative Signalling

According to Hanahan and Weinberg, cancer cells endure proliferative signalling by enabling growth factor expression, stimulating non-malignant cells within the tumour-associated stroma, upregulating receptor protein levels in cancer cells and altering the structures of receptor molecules while activating downstream mitogenic signalling pathways linked to these receptors [22]. Conceivably, the most significant function of HBx is its ability to promote cell proliferation in hepatocarcinogenesis. For example, HBx has been proposed to activate stellate cells in fibrosis and elevate expression of transforming-growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) thus promoting cellular transformation [23].

HBx-transgenic liver cancer mouse model studying pre-neoplasm showed a five-fold elevated expression of c-myc, a multifunctional transcription factor which promotes cell proliferation, while an In vitro study established a strong correlation between HBx and c-myc which abetted ribosome biogenesis and cellular transformation [24,25]. Another In vitro study involving HepG2 hepatoma cells, concluded HBx-SMYD3 interaction, guided by the downstream target gene c-myc, promoted cell proliferation [26]. Additionally, HBx-transgenic mouse models implicate enhanced expression of fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14 (fn14) in c-myc/TGF-α-driven hepatocarcinogenesis [27]. HBx also disrupts cell cycle progression by upregulating p21 and p27, proteins that inhibit cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity, which in turn enhances the ability of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling to cause proliferation in hepatocytes [28]. Similarly, HBx elevates serine/threonine p21 activated kinase 1 (PAK1) and causes cytoskeletal rearrangement in xenograft mouse models [29].

With regard to altering mitogenic signalling pathways, HBx promotes cell proliferation via the 5-LOX/FAS mediated positive feedback loop mechanism. In vitro studies in HepG2 and H7402 cells concluded that HBx upregulated the transcription of fatty acid synthase (FAS), known to play a critical role in tumour cell survival and proliferation, mediated by 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) through phosphorylated ERK 1/2 [30]. Another study also has found that HBx promotes liver cell division by upregulating cyclooxygenase (COX-2) and MERK/ERK kinase 2 (MEKK2), the latter known to regulate several transcription and translation factors [31]. COX-2, on the other hand, is highly expressed in HCC, and along with HBx, mediates sequestration of p53 to abolish apoptosis. Incapacitated p53 can induce reactivation of previously suppressed anti-apoptotic proteins such as Mcl-1 thus driving forward an indirect HBx-mediated cell proliferation [32]. HBV gene expression and hepatocyte transformation is also driven by Ras-Raf MAPK signalling pathway by HBx-mediated activation of Ras and Src kinase through overriding the pro-apoptotic effects of HBx which will be reviewed in the following sections [33,100]. Such signalling mechanisms are imperative for successfully stimulating cell cycle and deregulating cell cycle checkpoint controls [101].

HBx is also capable of enhancing cytosolic calcium levels leading to elevated mitochondrial calcium uptake which induces HBV replication in vitro [34]. HBx may be involved in extracellular matrix remodelling by elevating adhesion protein LASP-1 through PI3K pathway to promote hepatocyte proliferation and invasion [35]. It is worth noting that high concentrations of HBx and its subcellular localization, especially in cell systems that lack effective negative growth regulatory pathways and intact tumour suppressors, suggests that cell growth inhibition in such cells is not strictly governed to the extent of that of healthy cells, which could be a key driver of neoplastic transformation [102].

3. Evading Growth Suppressors

Neoplastic maladies arise from accumulated genetic and epigenetic changes in proto-oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes with the latter mostly involved in suppression of metastasis, pro-apoptosis and DNA damage repair [103]. For instance, mutations arising from the TP53 tumour suppressor gene have been implicated in over half of all human cancers [104]. HBx is known to bind to the C terminus of p53 and obstruct numerous crucial cellular processes such as transcriptional binding, DNA sequence-specific binding and apoptosis. More specifically, in human hepatocytes and fibroblasts, HBx partially sequesters p53 in the cytoplasm leading to unfavourable G1 arrest conditions that eventually result in inhibition of apoptosis, typically indicating onset of hepatocarcinogenesis [36,105]. Interestingly, transient transfection of human pulmonary adenocarcinoma Calu-6 cells has shown that HBx directly interacts with p53 and enables inhibition of p53 response element-directed transactivation [37].

Retinoblastoma-associated (Rb) tumour suppressor is another critical gatekeeper of cell cycle progression that is deregulated by HBx. It has been shown that HBx incapacitates inhibition of E2F1 activity, a positive regulator of cell cycle progression, by inactivating Rb gene promoter and thereby tumour suppressor Rb [38]. Additionally, HBx increases CDK2 activity, leading to impairment of E2F1–Rb balance, which confers stability to replication initiator protein CDC6 and aids in the HBx-mediated oncogenic sabotage thereafter [39].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), which regulate gene expression through translational repression and degradation of complementary target mRNAs, define tumourigenesis [106]. miR-205, a miRNA tumour suppressor is inhibited by HBx via hypermethylation of miR-205 promoter [40]. Another vital tumour suppressor miR-520b which targets cyclin D1 and MEKK2 is known to inhibit liver cancer cell proliferation [107]. HBx stimulates hepatocarcinogenesis by partnering with survivin by controlling tumor suppressor miR-520b and oncoprotein hepatitis B X-interacting protein (HBXIP), binding protein of HBx [41]. Epigenetically, HBx also represses RIZ1, another tumour suppressor of HCC, via methytransferase 1 (DNMT1) governed hypermethylation and suppressed miR-152 [42]. Moreover, HBx acts as an epigenetic deregulator by altering transcription of DNMT1 and 3 and thereby suppresses E-cadherin tumour suppressor while hypermethylating p16 via pRb-E2f pathway [43,44]. Tumour-suppression activity of retinoic acid receptor-beta 2 (RAR-β2) is epigenetically downregulated by HBx via DNMT-driven hypermethylation, instigating upregulation of G1-checkpoint regulators p16, p21 and p27 and eventually E2F1 activation and ensued tumourigenesis [45,108].

4. Resisting Cell Death

Programmed cell death by apoptosis, initiated by highly regulated cascades of intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, is another hurdle tumour cells need to circumvent. Series of upstream regulators and downstream effectors of the apoptotic machinery regulate binding of Fas ligand on the cell membrane leading to activation of caspase 8 and caspase 3 and thereby extrinsic pathways, while the mitochondrial release of cytochrome c activates extrinsic pathways, leading to proteolysis that gradually dissembles the cells, eventually consumed by phagocytic neighbouring cells [17,109].

Intriguingly, HBx-induced apoptosis in HCC plays a contradictory role depending on the cellular conditions and components that HBx interacts with. For instance, pro-apoptotic HBx induces the expression of TRAIL-R2 (DR5), a death receptor that targets TNF µ-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL) that is known to elicit apoptosis [46]. HBx suppresses the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of A20 via upregulation of miR-125a which prevents inhibition of caspase 8 leading to hepatocyte sensitization to TRAIL-induced apoptosis [47]. Conversely, anti-apoptotic HBx elevates the expression of widely known apoptosis inhibitor genes myeloid cell leukemia-1 (Mcl-1) and B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) which inherently restrains pro-apoptotic Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) further inactivating caspase 9 and 3 [48]. HBx also modulates apoptotic activities by acting on the mitochondria, caspases and SIRT-related pathways. More precisely, elevated cytoplasmic HBx interacts with apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and AIF-homologue mitochondrian-associated inducer of death (AMID) which primarily drives the inhibition of AIF translocation from mitochondrion-to-nucleus [49]. The discrepant behaviour of HBx-elicited apoptosis could be partly attributed to HBx mutations, such as C-terminal truncation (trHBx), which are significantly more common in tumour tissues compared to non-tumour tissues [110,111]. For example, expression of wild type HBx (wtHBx) impaired colony formation in several HCC cell lines while cell growth remained unaltered in cells transfected with trHBx, with some studies even suggesting that C-terminal transactivation might be the primary site of pro-apoptotic function [112]. However, it is worth noting that HBx intracellular localization could be another key driver of apoptosis, since wtHBx and trHBx displayed preferential localization in cytoplasm and nucleus, respectively [113,114].

Autophagy signifies another crucial cell-physiologic response that sequesters protein aggregates and impairs organelles into autophagosomes which fuse with lysosomes, resulting in degradation [50,115]. HBx is known to incapacitate lysosomal acidification and ensued decrease in lysosomal degradative capacity while simultaneously upregulating autophagy substrate SQSTM1 and lysosomal aspartic protease cathepsin D, which aids in chronic HBV infection followed by liver cancer [50]. Similarly, HBx interacts with BECN1 (Beclin 1) and hinders the interaction of BECN1-Bcl-2 complex that inhibits assembly of pre-autophagosomal components [51]. Contrariwise, In vitro studies in HepG2 cells suggest the progressive activation of autophagic lysosomal pathway by HBx via the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway [52]. Such paradoxical behaviour of HBx in driving autophagy of hepatocytes could be attributed to severely stressed cancer cells preferentially undergoing autophagy to achieve reversible dormancy [116]. Clarifying such conflicting behaviours of HBx-induced autophagic tumour cells could close a crucial research gap in liver cancer research.

5. Enabling Replicative Immortality

Contrary to the proliferative barriers that normal cells instil with limited number of division cycles, tumour cells display acquired unlimited replicative potential, propagated primarily by abrogating senescence and cell death. For instance, telomere maintenance is crucial to sustaining the neoplastic state. Healthy cells achieve apoptosis or senescence by decreasing telomerase activity and gradually shortening the telomeres, unlike tumour cells which preserve unaltered telomere lengths owing to persistent telomerase reactivation [117]. HBx is reported to impact on telomeres and telomerase activity; however, this remains controversial. A number of studies have suggested that HBx activates human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) mRNA expression in hepatocarcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma cells [53,54,118], whereas one study reported that HBx transgenic mice showed significantly low telomerase activity with virtually no difference in the mRNA expression of hTERT compared to healthy mice, during partial hepatectomy [119]. However, since there is high mutation rate in HBx, especially in different HBV genotypes, it is challenging to exclusively define telomerase activity in the HCC patient population as a whole. Canonically, one study argues that certain, not all, HBx isoforms are able to impair human telomerase expression by transcriptionally repressing its promoter, aided by myc-associated zinc finger protein (MAZ) binding to its consensus sequence. Nonetheless, telomere shortening is widely observed in hepatocarcinogenesis. They further speculate that HBx-mediated impaired telomerase activity could lead to genome instability and subsequent restoration of telomerase transcription that may aid in HCC cellular transformation [55].

6. Prompting Angiogenesis

Unregulated angiogenesis is a key hallmark of neoplastic growth and metastasis. Similar to normal tissues, tumour tissues too acquire nutrients and oxygen as well as dispel waste products by developing new blood vessels, known as angiogenesis. However, unlike the tightly regulated largely quiescent vasculogenesis in normal cells, cancer cells maintain a constantly activated “angiogenic switch” owing to several countervailing factors [120,121]. There is a strong correlation between HBV-induced angiogenesis and HCC progression and malignancy, especially by the only regulatory protein encoded by HBV: HBx [122].

Compelling evidence by Kleinman and Martin (2005) show that, in matrigel injected mice, HBx-expressing HCC cells induced more blood vessel formation compared to control HCC cells. Moreover, HBx alone could not only elicit angiogenesis but also upregulate VEGF mRNA expression as well as aid in transcriptional activation and stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α), the latter a key regulator of cellular adaptive responses to hypoxic conditions [56,57,58]. HBx directly interacts with transcriptional regulator bHLH/PAS domain of HIF-1α while mitigating binding of tumour suppressor protein von Hippel-Lindau (pVHL) and averting ubiquitin-dependent degradation of HIF-1α [58]. More specifically, HBx induces phosphorylation of HIF-1α while activating p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) [59]. HBx also drives HIF-1α-related angiogenesis by upregulating metastasis-associated protein 1 (MTA1), critical gene involved in tumour invasion and metastasis, and histone deacetylase (HDAC1) [60]. Increased expression of VEGF and HIF-1α has been observed in patient samples, thus entails a strong positive correlation with HBV-induced HCC [123,124]. HBx has been known to overexpress several matrix metalloproteinases (MMP 2 [61], 3 [62] and 9 [63]), which initiates neovascularization by disintegrating basement membrane thus ameliorating endothelial migration to nearby tissues. Moreover, HBx induction of COX-2 enzyme catalyses pro-angiogenic activity that further drives HBV-associated tumourigenesis [64].

Among key pathways that govern angiogenesis in general, Notch signalling is notable for its functions in cell development, wound healing, pregnancy and more importantly, tumour angiogenesis. More explicitly, Notch ligands Delta-like 4 (DII4) seem to act as a negative regulator of tumour angiogenesis. One study reported upregulated Notch1 and DII4 in HBV genome containing HepG2.2.15 cells compared to HepG2 control cells, also HBx silencing diminished DII4 levels and cleaved Notch1 [65]. Furthermore, specific signalling pathway inhibitor treatment assured that MEK1/2, PI3K/AKT and NF-κB pathways deem imperative for HBx-mediated Dll4 upregulation [65]. Angiogenesis in hypervascular tumours such as HCC is partly regulated by angiopoietins especially the well-characterized angiopoietin-1 (Ang1) and angiopoietin-2 (Ang2) which bind to the tyrosine kinase receptor. Unsurprisingly, HBx-expressing hepatocytes and HBV infected patient biopsies have shown significant stimulation of Ang-2 isoform expression [66]. Finally, successful vasculature and tumour invasion require endothelium-derived nitric oxide and according one study, HBx alone or HBV genome are capable of inducing nitrogen oxide synthase 2 (NOS2) mRNA expression; however, this potential mechanism warrants further research [67].

7. Triggering Invasion and Metastasis

Tumour metastatic dissemination and invasion is conceivably the most significant cancer hallmark, as all other hallmarks tend to be indistinctively represented in both benign and malignant tumours, unlike metastasis which, with the exception of endometriosis, tends to define malignancy for its unique characteristic ability to invade and colonize distant healthy tissues [125].

The influence of HBx on cell migration, invasion and extracellular matrix remodelling are largely associated with the upregulation of membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs). Aggressive behaviour of HCC cells is partly driven by metastasis induced by HBx, which disrupts adherences junctions and integrin-associated adhesion to the extracellular matrix in addition to promoting production of MMPs 1, 3 and 9 [126]. HBx expressing cells have been shown to modify α integrin subunits and activate β1 integrin subunits which localize in pseudopods and prevents cell attachment, thus leading to epithelial transformation [69]. Calpain small subunit 1 (Capn4), a regulatory subunit involved in cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis, is highly correlated with tumour metastasis after liver transplantation [127]. Interestingly, HBx contributes to upregulation of Capn4 via nuclear factor-kB/p65 in HepG2 hepatoma cells [70]. Another study has also highlighted, HBx-mediated progression of tumour stemness in HCC via a positive feedback loop mechanism involving miR-5188 impairment of FOXO1 (a well-characterized tumour suppressor in HCC) and stimulation of β-catenin nuclear translocation [71]. Likewise, miRNA-driven HBx influence has been associated with metastatic behaviour, for instance, In vivo work by Zhang et al. demonstrates a dramatic elevation of miRNA-143 (miR-143) in HBx transgenic mice [72]. MiR-143 transcription is carried out by nuclear factor kappa B (Nf-Kb) which potentiates metastatic activities and fibronectin type III domain containing 3B (FNDC3B) which directs cell motility [72].

HBx alters migratory phenotype of transformed hepatocytes through cytoskeletal rearrangement and development of pseudopodial protrusions in addition to activating cell-surface adhesion molecule CD44, a hyaluronan (HA) receptor. This is achieved by HBx-mediated relocation of F-actin binding proteins (that belong to the ezrin/radixin/moesin family) in the pseudopodial protuberances, via a Rho/Rac- dependent manner while simultaneously enhancing CD44-moesin interaction [73]. While a majority of these studies focus on HBx wild type, one landmark study has concluded that HBx mutant, HBxΔ127 promotes hepatoma cell migration by activating ossteopontin (OPN), a secreted phosphoprotein well implicated in mammalian epithelial cell transformation, through 5-LOX (another key enzyme tied to metabolism of arachidonic acid and often upregulated in several tumor types) [74]. It is worth noting that HBV integration which most often leads to terminal truncations on HBx, was identified in 80%-90% of the host genome of HBV-induced HCC cases [128].

A key developmental regulatory process prominently involved in cancer metastasis and invasion is epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT). Among plethora of research focussing on EMT modulation by oncogenic viruses, HBV-induced HCC has been well implicated especially due to the high incidence of poor patient survival associated with metastasis in advanced tumour stages [129]. HBx ameliorates cancer motility and EMT by activating signal transducers and activators of transcription 5b (STAT5b) and c-Src proto-oncogene in hepatoma cells [75,76]. Moreover, HBx stabilizes Snail protein, a key EMT-orchestrating transcriptional factor, through triggering the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B/glycogen synthase kinase-3b (PI3K/AKT/GSK-3b) signalling pathway [77]. Lastly, HBx is known to induce the expression of vimentin, a putative mesenchymal marker, while epigenetically repressing E-cadherin, a key cell-to-cell adhesion molecule which best characterizes phenotypic alterations that are indicative of EMT-driven cellular transformation [78,79].

8. Evading Immune Destruction

Evading innate and adaptive immunity remains a crucial defensive mechanism that ensures HBV survival in infected hepatocytes. While it is expected for virus–host interactions to induce immune system activation, viruses with oncogenic potential, through evolution, have developed several strategies to surpass barriers of the immune system and establish chronic infections [130].

In particular, HBx imposes immune suppression by inducing apoptosis in HBV-specific CD8+ T cells (known to be major effector cells of viral clearance during acute HBV infection), while decreasing the production of interferon-ϒ in hepatocytes (a cytokine that suppresses HBV proliferation in hepatocytes) [80,131]. Beta interferon promoter stimulator 1 (IPS-1) is an adaptor protein that mediates retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 (RIG-1) signalling and is known to activate antiviral innate immune response and interferon β (IFN-β). HBx-IPS-1 protein interaction interferes with RIG-1-related immuneregulation and inhibits activation of IFN-β [81]. Similarly, HBx mediates inhibition of IFN-regulatory factor (IRF3) and disrupts associations of the mitochondrial membrane protein virus-induced signalling receptor (VISA) with its upstream components RIG-1 and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) [82]. Another HBx/IFN-β linked immune suppression mechanism is the interaction between HBx and mitochondrial antiviral signalling (MAVS) protein, a critical activator of Nf-kB and IRF-3, and degradation of MAVS via Lys-136 ubiquitination that prevents IFN-β induction [83]. Moreover, HBx protein impairs glucose metabolism with augmented lactate production, which weakens the migratory ability of T cells in the liver as well as their cytolytic activity [132]. Additionally, HBV evades immune recognition with the aid of HBx which transcriptionally promotes RNA adenosine deaminase ADAR1 resulting in HBV RNA deamination of adenosine (A) to generate inosine (I),which disrupts host immune recognition in hepatocytes [84].

Attenuation of the antiviral immune response can also be accomplished by HBx-mediated epigenetic modulation and miRNA dysregulation [133]. HBx-dysregulated tumour suppressor miR-101 reduces LPS-stimulated macrophage expression, capable of inducing HCC, due to its inability to modulate DUSP1 phosphatase enzyme, which leads to impaired ERK1/2/p38/JNK elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TGF-β [134]. To gain a more comprehensive insight into HBx influence on a plethora of miRNA dysregulation pathways and their associated immune response, refer to Sartorius et al. [133].

9. Tumour-Promoting Inflammation

Inflammation, an adaptive response to infection and tissue damage, paradoxically contributes towards tumourigenesis via facilitating other cancer hallmarks by delivering bioactive molecules to the tumour microenvironment, such as anti-apoptotic survival factor, growth factors, angiogenesis-driving extracellular matrix-modifying enzymes, proangiogenic factors and inductive signals that aid in cellular transformation [22]. Non-resolving inflammation which substantially contributes to HCC, is initiated by extrinsic pathways involving pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) by pathogen-associated molecule patterns (PAMPs) resulting from gut microflora or damage-associated molecule patterns (DAMPs) released from apoptotic liver cells. Such inflammation-mediating DAMPs include nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins, such as, histones and IL-1, high-mobility group box1 (HMGB1), heat shock proteins and myeloid-specific S100 proteins (S100s). Similarly, intrinsic pathways, including the recruitment of inflammatory cells by the tumour itself, too contribute to HCC disease pathogenesis [135].

HBx overexpression in healthy hepatocytes induces serine/threonine kinases, in particular, receptor-interacting protein (RIP-1), which inherently aids in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8 and CXCL2, in addition to secreting HMGB1, a cytokine mediator of inflammation [85]. Moreover, HBx has been mechanistically demonstrated to induce S100A9 DAMP protein, by prompting translocation of cytoplasmic NF-kB into the nucleus followed by binding to activate its transcription [86]. Activated S100A9 binds to PRR receptor RAGE in the tumour microenvironment and blocks host-mediated antitumor immune response targeting tumour cells, in doing so enabling tumour progression [136,137].

HBx induces immunomodulation by upregulating inflammatory cytokines and other related cellular components such as ICAM-1, major histocompatibility complex and Fas ligand, thus promoting long term liver inflammation and ensuing HCC [138,139]. Paradoxically, HBx may also hinder HBV-specific immune response, promote apoptosis of immune cells and induce immune response leading to persistent HBV infection and liver tumourigenesis [140]. In vitro, HBx stimulates production of interleukin-6 (IL-6) while activating downstream signalling targets of innate immune signal transduction adaptor MyD88, including, IRAK-1, NF-kB and ERKs/p38 in the HBV-infected liver microenvironment [87]. Besides, chemokine expression profiles in hepatoma cells show that IL-8 is significantly upregulated when HBx is overexpressed, while downregulation was observed in pro-inflammatory mediators such as, macrophage inflammatory protein-3β (MIP-3β), epithelial-neutrophil activating protein 78 (ENA78) and monocyte chemotactic proteins-1, -2 and -3 [141]. In chronic HBV patients, HBx also invokes activation of ERK/NF-kB pathway which leads to transactivation of the p19 and p40 subunits of IL-23, predominantly secreted by macrophages and dendritic cells which are mainly activated by proinflammatory cytokines [88]. Another study reports that HBx-mediated tumour microenvironment remodelling involves interactions with centrosomal P4.1-associated protein (CPAP), a key regulator of procentriole elongation and microtubule nucleation, which progressively leads to enhanced inflammatory cytokine production, malignancy associated with NF-kB activation [89].

10. Genome Instability and Mutation

Successful establishment of neoplasms and eventual dominance over the tumour microenvironment, in part require alterations in the premalignant cell genome and amassing favourable genotypes. Tumour cells hijack the host DNA-maintenance machinery by damaging the host cell’s ability to detect and respond to DNA damage, activate DNA repairing and inactivate mutagenic molecules [22]. HBV in known to productively infect hepatocytes by taking over DNA damage response proteins and indirectly influencing intracellular signalling pathways that determine DNA repair [142].

HBx induces genetic instability and defects in chromosomal segregation partly by binding with the conserved HBx-interacting protein (HBXIP) and driving aneuploidy associated with overabundant centrosome formation as well as tripolar and multipolar mitotic spindles. HBx promotes aneuploidy, a classic trait of tumourigenicity, by disrupting the cell growth stimulating function of HBXIP, resulting in failed centrosome duplication during prometaphase. HBXIP and HBx prevent the dissociation of midbody microtubules that hold the dividing daughter cells together during telophase, which leads to merged binucleated cells [90]. Additionally, HBx has been shown to contain a leucine-rich nuclear export signal (NES) domain which binds to nuclear export receptor Crm1 and activates NF-kB nuclear translocation. Given Crm1 plays a role in mitosis, HBx-mediated inactivation of Crm1 via its nuclear export could be a key affair that drives HBV related oncogenesis [91]. Additionally, since Crm1 is involved in maintaining centrosome integrity, disrupting Crm1 activity by HBx indirectly drives formation of supernumerary centrosomes and abnormal multipolar spindles [143]. HBx overexpression in healthy hepatocytes displays synthesis of polyploidy nuclei, DNA damage accumulated via elevated IL-6 expression and PLK1 and p38/ERK activation which strongly correlates with aberrant polyploidation and hepatocyte transformation [144].

With regard to HBx-mediated disruption of DNA repair mechanisms, HBx binds with damaged DNA binding (DDB) proteins causing alterations in p53 function, which in turn induces cell apoptosis and inhibits nucleotide excision repair (NER), thereby compromising genome integrity [92,145]. Furthermore, Ras-induced senescence is interrupted by HBx leaving hepatocytes cells vulnerable to mitotic errors, caused by supernumeracy centrosomes and multipolar spindles [93]. HBx also stimulates DNA helicase catalytic activity of TFIIH subunits while recruiting DNA-repair enzyme tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 2 (TDP2) for the synthesis of HBV DNA [94,146]. Chromosome segregation and organization are crucial functions of the structural maintenance of chromosomes (Smc) complex proteins, Smc 5/6 in particular. Relevantly, given the multi-regulatory functions of HBx, it is not surprising that HBx promotes host cell genetic instability via degradation of Smc 5/6 proteins following binding with cellular DDB1-containing E3 ligase [95,147].

11. Deregulating Cellular Energetics

Altered energy metabolism is another crucial malignancy trait that is closely associated with exponential proliferation-inducing hallmark of cancer cells, with regard to the abnormal Warburg effect of cancer cell metabolism. One study shows that C-terminal truncated HBx in capable of inducing neoplasmic traits by downregulating an important regulator of glucose sensing and reduction–oxidation system, thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP), which drives glucose metabolism reprogramming [96]. This finding remains significant as TXNIP has been implicated as a tumour suppressor and its expression is either low or redundant in hepatoma cells [148]. Cancer cells promote their aerobic glycolysis-driven energy metabolism by upregulating glucose transporters such as GLUT1, to increase glucose uptake into the cytoplasm. Oncogene HBx interacting protein HBXIP elevates GLUT1 via upregulating NF-kB in liver cancer [97]. Another recent study has concluded that hepatic glucose homeostasis is retained by HBx via elevating the gene expression of hepatic gluconeogenic enzymes, namely, PEPCK, PGC1α, and G6Pase and glucose production which are inherently regulated through nitric oxide (NO)/JNK signalling [98].

HBx contributes to abnormal energy metabolisms in hepatic cells by promoting lipid peroxidation and reactive oxygen species (ROS). In hepatoma cell lines, HBx also reduces expression of mitochondrial enzymes that are part of electron transport in oxidative phosphorylation (complexes I, III, IV, and V) while sensitizing the mitochondrial membrane potential [149]. HBx induces oxidative stress and mitochondrial injury by downregulating NADPH: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) enzyme detoxifies ROS, thereby indirectly inducing glycolysis that drives carcinogenesis. Interestingly, C-terminal truncated HBx-induced mitochondrial damage is more severe than nucleus DNA [99].

12. Therapeutic Potential of HBx

Since HBx expression persists throughout from the inception of acute HBV infection to the progression of HCC, spanning a couple of decades of repeated cycles of chronic liver inflammation, it could be considered an ideal therapeutic target. While research into the potential therapeutic implications of HBx is still in its infancy, identifying HBx-interacting host cell targets and better understanding HBx-mediated host immune response, could potentially help reverse the chronic inflammatory state during HBV, and thereby preventing liver cellular transformation.

However, given the multi-regulatory functions of HBx, especially its pervasive role in every cancer hallmark, it remains challenging to narrow down the search for prospective therapies [150]. Another limitation is that due to the difficulty in obtaining appropriate protein samples, the native full-length polypeptide sequence of HBx has not been deciphered by NMR or x-ray structural characterization [151]. Additionally, standardized protocols are yet to be established for studying HBx [152]. Even though the majority of the HBx-related studies, as detailed in this review, rely on HBx-overexpression In vitro studies, these models fall short of deciphering its real physiological relevance. Another limitation can be attributed to the double-edged nature of HBx, for instance, its contradictory role in both promoting and inhibiting apoptosis as well as alternating between activating and hindering host immune response, throughout the course of the HBV infection.

Despite such shortcomings, experimental progress in HBx-based therapeutics are currently being pursued worldwide. Recently, HBx protein-based therapeutic vaccine has been shown to drive HBV viral antigen clearance by mobilizing systemic HBx-mediated CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response in HBV carrier mice [153]. Similarly, In vitro and In vivo HBx-knockdown models using short hairpin or short interfering RNA have been shown to abrogate HBx activity and promote antiviral response and anti-tumourigenicity [154,155]. HBx monoclonal antibody shows promise as an anti-tumour agent based on HCC mouse models and clinical studies. HBx antibody bound cell penetrating HIV tat protein which is conjugated experimentally to enhance antibody delivery to the cell, inhibits HBV transcription and translation. Combinatorial therapies utilizing HBx antibody and HBV capsid inhibitors that eliminate viral infection could aid in long term containment of chronic HBV infection and tumour emergence [156,157]. Alternatively, more research needs to be focused into repurposing drugs currently existing in the market. For instance, Dicoumarol, a competitive NQO1 inhibitor, has been verified as an inhibitor of HBx expression, displaying strong antiviral activity in humanised mouse model [157]. Similarly, FDA-approved Nitazoxanide, repurposed from its prescription for protozoan enteritis, inhibits the HBx-DDB1 protein interaction and restores Smc5 protein expression and prevents viral transcription and translation [158]. Another study which conducted large-scale screening of 640 FDA-approved drugs against HBV, concluded that a few of these compounds (24 most potent compounds) decreased HBV transcription by, on average, 33.9% in the absence of HBx expression and 30.6% in the presence of HBx. Further analysis showed one compound, Terbinafine, potently and specifically impaired HBx-mediated HBV RNA transcription In vitro [159].

More precisely, among principal clinical trials in randomized Phase II trial evaluating antiviral therapies to combat HBV, the recombinant yeast-based vaccine, GS-4774, which contains HBx, HBsAg and HBcAg viral components capable of eliciting an immune response by promoting antigen processing via MHC class I and II pathways, was assessed. The study concluded that, while the vaccine was well-tolerated, there was limited efficacy observed, with no significant clinical outcomes in HBsAg clearance, in virally suppressed non-cirrhotic patients with chronic HBV infection [160]. Similarly, another randomized Phase II trial using combinatorial therapy of GS-4774 and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), showed clear restoration of several T-cell functions in HBeAg negative patients with hepatitis B even though the therapy fell short on producing clinically significant decrease in HBsAg in these patients [161,162]. Notably, therapies solely based on HBx are yet to reach clinical trials. Nonetheless, these promising observations further emphasize the significance of targeting HBx along with combinatorial therapies in eliminating HBV-induced hepatocellular carcinoma.

13. Conclusions and Future Prospects

The high mortality rate associated with HBV-induced hepatocarcinogenesis has encouraged intense research into better understanding the cellular and physiological mechanisms of HBV-induced liver malignancies. With regard to HBx viral protein, its multifactorial nature prevents current research from identifying a specific function of HBx that potentially drives cellular transformation. Unsurprisingly, it is even more challenging to identify suitable cellular targets for HBx-based therapy since it is difficult to quantify the cellular and nuclear localization of HBx at a particular point over the course of the HBV infection, as this is subjected to frequent alterations depending on the HBV viral load, tumour microenvironment and other risk factors the liver encounters (hepatitis C, metabolic diseases, chronic alcoholism and aflatoxin exposure) [163]. Nonetheless, the past few decades have witnessed a surge in research focussing on the role of HBx in the initiation, progression and metastasis of HCC.

While decades of research have suggested the potential role of HBx from genetic and epigenetic standpoints, especially its implication on HCC pathogenesis, the emerging field of epitranscriptomics, the study of RNA modifications, is an untrodden territory that warrants research. Few studies have suggested certain RNA modifications such as m6A to play a crucial role in HCC, yet the role of the HBx protein in this context remains unclear, highlighting a research gap with immense therapeutic prospective [164,165,166,167,168,169]. It is also worth exploring the mechanisms HBx employs to control the level of HBV replication and which exact domains and host cell targets are modulated by HBx and their concomitant biological relevance. A better understanding how HBx regulates various hallmarks of HCC would provide rather an overall picture of HBV-mediated HCC. In this context, it is imperative to take into account the short half-life and unstructured nature of HBx when designing experimental models to closely emulate, as much as possible, actual liver disease pathogenesis. Thus, elucidating the role of HBx in hepatocarcinogenesis could be the key to unlocking promising therapeutic strategies to combat HCC.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to the authors whose excellent works have not been quoted in this review manuscript due to space restriction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R., Z.L. and J.M.; Writing—original draft preparation, E.S.; Critical revision, N.B. and R.R; Funding acquisition, R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Key Program Special Fund of Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (KSF-E-23, R.R.) and the Research Development Fund of Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (RDF-17-02-31 R.R.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Global Progress Report on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2021. [(accessed on 29 December 2021)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027077.

- 2.Wong V.W.-S., Janssen H.L.A. Can we use hcc risk scores to individualize surveillance in chronic hepatitis b infection? J. Hepatol. 2015;63:722–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kgatle M. Advances in Treatment of Hepatitis C and B. IntechOpen; London, UK: 2017. Recent advancement in hepatitis b virus, epigenetics alterations and related complications. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seeger C., Mason W.S. Hepatitis b virus biology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. MMBR. 2000;64:51–68. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.1.51-68.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feitelson M.A., Lee J. Hepatitis b virus integration, fragile sites, and hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2007;252:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berasain C., Castillo J., Perugorria M.J., Latasa M.U., Prieto J., Avila M.A. Inflammation and liver cancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009;1155:206–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali A., Abdel-Hafiz H., Suhail M., Al-Mars A., Zakaria M.K., Fatima K., Ahmad S., Azhar E., Chaudhary A., Qadri I. Hepatitis b virus, hbx mutants and their role in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10238–10248. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathew M.A., Kurian S.C., Varghese A.P., Oommen S., Manoj G. Hbx gene mutations in hepatitis b virus and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterol. Res. 2014;7:1–4. doi: 10.14740/gr589w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller R.H., Robinson W.S. Common evolutionary origin of hepatitis b virus and retroviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:2531–2535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin-Vilchez S., Lara-Pezzi E., Trapero-Marugán M., Moreno-Otero R., Sanz-Cameno P. The molecular and pathophysiological implications of hepatitis b x antigen in chronic hepatitis b virus infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 2011;21:315–329. doi: 10.1002/rmv.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henkler F., Hoare J., Waseem N., Goldin R.D., McGarvey M.J., Koshy R., King I.A. Intracellular localization of the hepatitis b virus hbx protein. J. Gen. Virol. 2001;82:871–882. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-4-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouchard Michael J., Schneider Robert J. The enigmatic x gene of hepatitis b virus. J. Virol. 2004;78:12725–12734. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12725-12734.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faktor O., Shaul Y. The identification of hepatitis b virus x gene responsive elements reveals functional similarity of x and htlv-i tax. Oncogene. 1990;5:867–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami S. Hepatitis b virus x protein: A multifunctional viral regulator. J. Gastroenterol. 2001;36:651–660. doi: 10.1007/s005350170027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caselmann W.H., Koshy R. Hepatitis B Virus. Imperial College Press; London, UK: 1998. Transactivators of hbv, signal transduction and tumorigenesis; pp. 161–181. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rawat S., Clippinger A.J., Bouchard M.J. Modulation of apoptotic signaling by the hepatitis b virus x protein. Viruses. 2012;4:2945–2972. doi: 10.3390/v4112945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson W.S. Molecular events in the pathogenesis of hepadnavirus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Annu. Rev. Med. 1994;45:297–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.45.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seifer M., Höhne M., Schaefer S., Gerlich W.H. In vitro tumorigenicity of hepatitis b virus DNA and hbx protein. J. Hepatol. 1991;13:S61–S65. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paterlini P., Poussin K., Kew M., Franco D., Brechot C. Selective accumulation of the x transcript of hepatitis b virus in patients negative for hepatitis b surface antigen with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1995;21:313–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo G.H., Tan D.M., Zhu P.A., Liu F. Hepatitis b virus x protein promotes proliferation and upregulates tgf-beta1 and ctgf in human hepatic stellate cell line, lx-2. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. HBPD INT. 2009;8:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shukla S.K., Kumar V. Hepatitis b virus x protein and c-myc cooperate in the upregulation of ribosome biogenesis and in cellular transformation. FEBS J. 2012;279:3859–3871. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terradillos O., Billet O., Renard C.A., Levy R., Molina T., Briand P., Buendia M.A. The hepatitis b virus x gene potentiates c-myc-induced liver oncogenesis in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1997;14:395–404. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang L., He J., Chen L., Wang G. Hepatitis b virus x protein upregulates expression of smyd3 and c-myc in hepg2 cells. Med. Oncol. 2009;26:445–451. doi: 10.1007/s12032-008-9144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng S.L., Guo Y., Factor V.M., Thorgeirsson S.S., Bell D.W., Testa J.R., Peifley K.A., Winkles J.A. The fn14 immediate-early response gene is induced during liver regeneration and highly expressed in both human and murine hepatocellular carcinomas. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;156:1253–1261. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64996-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiao L., Leach K., McKinstry R., Gilfor D., Yacoub A., Park J.S., Grant S., Hylemon P.B., Fisher P.B., Dent P. Hepatitis b virus x protein increases expression of p21(cip-1/waf1/mda6) and p27(kip-1) in primary mouse hepatocytes, leading to reduced cell cycle progression. Hepatology. 2001;34:906–917. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu J., Liu H., Chen L., Wang S., Zhou L., Yun X., Sun L., Wen Y., Gu J. Hepatitis b virus x protein confers resistance of hepatoma cells to anoikis by up-regulating and activating p21-activated kinase 1. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:199–212.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Q., Zhang W., Liu Q., Zhang X., Lv N., Ye L., Zhang X. A mutant of hepatitis b virus x protein (hbxdelta127) promotes cell growth through a positive feedback loop involving 5-lipoxygenase and fatty acid synthase. Neoplasia. 2010;12:103–115. doi: 10.1593/neo.91298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shan C., Xu F., Zhang S., You J., You X., Qiu L., Zheng J., Ye L., Zhang X. Hepatitis b virus x protein promotes liver cell proliferation via a positive cascade loop involving arachidonic acid metabolism and p-erk1/2. Cell Res. 2010;20:563–575. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee Y.I., Kang-Park S., Do S.I., Lee Y.I. The hepatitis b virus-x protein activates a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent survival signaling cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:16969–16977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011263200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noh E.J., Jung H.J., Jeong G., Choi K.S., Park H.J., Lee C.H., Lee J.S. Subcellular localization and transcriptional repressor activity of hbx on p21(waf1/cip1) promoter is regulated by erk-mediated phosphorylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;319:738–745. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang B., Bouchard M.J. The hepatitis b virus x protein elevates cytosolic calcium signals by modulating mitochondrial calcium uptake. J. Virol. 2012;86:313–327. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06442-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang R., Kong F., Hu L., You H., Zhang P., Du W., Zheng K. Role of hepatitis b virus x protein in regulating lim and sh3 protein 1 (lasp-1) expression to mediate proliferation and migration of hepatoma cells. Virol. J. 2012;9:163. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elmore L.W., Hancock A.R., Chang S.F., Wang X.W., Chang S., Callahan C.P., Geller D.A., Will H., Harris C.C. Hepatitis b virus x protein and p53 tumor suppressor interactions in the modulation of apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:14707–14712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Truant R., Antunovic J., Greenblatt J., Prives C., Cromlish J.A. Direct interaction of the hepatitis b virus hbx protein with p53 leads to inhibition by hbx of p53 response element-directed transactivation. J. Virol. 1995;69:1851–1859. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1851-1859.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi B.H., Choi M., Jeon H.Y., Rho H.M. Hepatitis b viral x protein overcomes inhibition of e2f1 activity by prb on the human rb gene promoter. DNA Cell Biol. 2001;20:75–80. doi: 10.1089/104454901750070274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pandey V., Kumar V. Hbx protein of hepatitis b virus promotes reinitiation of DNA replication by regulating expression and intracellular stability of replication licensing factor cdc6. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:20545–20554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.359760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang T., Zhang J., Cui M., Liu F., You X., Du Y., Gao Y., Zhang S., Lu Z., Ye L., et al. Hepatitis b virus x protein inhibits tumor suppressor mir-205 through inducing hypermethylation of mir-205 promoter to enhance carcinogenesis. Neoplasia. 2013;15:1282–1291. doi: 10.1593/neo.131362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang W., Lu Z., Kong G., Gao Y., Wang T., Wang Q., Cai N., Wang H., Liu F., Ye L., et al. Hepatitis b virus x protein accelerates hepatocarcinogenesis with partner survivin through modulating mir-520b and hbxip. Mol. Cancer. 2014;13:128. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao Z., Hu Y., Shen X., Lao Y., Zhang L., Qiu X., Hu J., Gong P., Cui H., Lu S., et al. Hbx represses riz1 expression by DNA methyltransferase 1 involvement in decreased mir-152 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2017;37:2811–2818. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee J.O., Kwun H.J., Jung J.K., Choi K.H., Min D.S., Jang K.L. Hepatitis b virus x protein represses e-cadherin expression via activation of DNA methyltransferase 1. Oncogene. 2005;24:6617–6625. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu Y.Z., Zhu R., Fan J., Pan Q., Li H., Chen Q., Zhu H.G. Hepatitis b virus x protein induces hypermethylation of p16(ink4a) promoter via DNA methyltransferases in the early stage of hbv-associated hepatocarcinogenesis. J. Viral Hepat. 2010;17:98–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jung J.K., Park S.H., Jang K.L. Hepatitis b virus x protein overcomes the growth-inhibitory potential of retinoic acid by downregulating retinoic acid receptor-beta2 expression via DNA methylation. J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91:493–500. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kong F., You H., Zhao J., Liu W., Hu L., Luo W., Hu W., Tang R., Zheng K. The enhanced expression of death receptor 5 (dr5) mediated by hbv x protein through nf-kappab pathway is associated with cell apoptosis induced by (tnf-α related apoptosis inducing ligand) trail in hepatoma cells. Virol. J. 2015;12:192. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0416-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang H., Huang C., Wang Y., Lu Z., Zhuang N., Zhao D., He J., Shi L. Hepatitis b virus x protein sensitizes trail-induced hepatocyte apoptosis by inhibiting the e3 ubiquitin ligase a20. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0127329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen L., Zhang X., Hu D., Feng T., Li H., Lu Y., Huang J. Hepatitis b virus x (hbx) play an anti-apoptosis role in hepatic progenitor cells by activating wnt/β-catenin pathway. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2013;383:213–222. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1769-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu H., Yuan Y., Guo H., Mitchelson K., Zhang K., Xie L., Qin W., Lu Y., Wang J., Guo Y., et al. Hepatitis b virus encoded x protein suppresses apoptosis by inhibition of the caspase-independent pathway. J. Proteome Res. 2012;11:4803–4813. doi: 10.1021/pr2012297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu B., Fang M., Hu Y., Huang B., Li N., Chang C., Huang R., Xu X., Yang Z., Chen Z., et al. Hepatitis b virus x protein inhibits autophagic degradation by impairing lysosomal maturation. Autophagy. 2014;10:416–430. doi: 10.4161/auto.27286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Son J., Kim M.J., Lee J.S., Kim J.Y., Chun E., Lee K.Y. Hepatitis b virus x protein promotes liver cancer progression through autophagy induction in response to tlr4 stimulation. Immune Netw. 2021;21:e37. doi: 10.4110/in.2021.21.e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang P., Guo Q.S., Wang Z.W., Qian H.X. Hbx induces hepg-2 cells autophagy through pi3k/akt-mtor pathway. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2013;372:161–168. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1457-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qu Z.L., Zou S.Q., Cui N.Q., Wu X.Z., Qin M.F., Kong D., Zhou Z.L. Upregulation of human telomerase reverse transcriptase mrna expression by in vitro transfection of hepatitis b virus x gene into human hepatocarcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma cells. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5627–5632. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i36.5627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang X., Dong N., Zhang H., You J., Wang H., Ye L. Effects of hepatitis b virus x protein on human telomerase reverse transcriptase expression and activity in hepatoma cells. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2005;145:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Su J.-M., Lai X.-M., Lan K.-H., Li C.-P., Chao Y., Yen S.-H., Chang F.-Y., Lee S.-D., Lee W.-P. X protein of hepatitis b virus functions as a transcriptional corepressor on the human telomerase promoter. Hepatology. 2007;46:402–413. doi: 10.1002/hep.21675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee S.W., Lee Y.M., Bae S.K., Murakami S., Yun Y., Kim K.W. Human hepatitis b virus x protein is a possible mediator of hypoxia-induced angiogenesis in hepatocarcinogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;268:456–461. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yun C., Lee J.H., Wang J.H., Seong J.K., Oh S.H., Yu D.Y., Cho H. Expression of hepatitis b virus x (hbx) gene is up-regulated by adriamycin at the post-transcriptional level. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;296:1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moon E.J., Jeong C.H., Jeong J.W., Kim K.R., Yu D.Y., Murakami S., Kim C.W., Kim K.W. Hepatitis b virus x protein induces angiogenesis by stabilizing hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. FASEB J. 2004;18:382–384. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0153fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoo Y.G., Oh S.H., Park E.S., Cho H., Lee N., Park H., Kim D.K., Yu D.Y., Seong J.K., Lee M.O. Hepatitis b virus x protein enhances transcriptional activity of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha through activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:39076–39084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoo Y.G., Na T.Y., Seo H.W., Seong J.K., Park C.K., Shin Y.K., Lee M.O. Hepatitis b virus x protein induces the expression of mta1 and hdac1, which enhances hypoxia signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:3405–3413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lara-Pezzi E., Gómez-Gaviro M.V., Gálvez B.G., Mira E., Iñiguez M.A., Fresno M., Martínez-A C., Arroyo A.G., López-Cabrera M. The hepatitis b virus x protein promotes tumor cell invasion by inducing membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 expression. J. Clin. Investig. 2002;110:1831–1838. doi: 10.1172/JCI200215887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu F.L., Liu H.J., Lee J.W., Liao M.H., Shih W.L. Hepatitis b virus x protein promotes cell migration by inducing matrix metalloproteinase-3. J. Hepatol. 2005;42:520–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu L.P., Liang H.F., Chen X.P., Zhang W.G., Yang S.L., Xu T., Ren L. The role of nf-kappab in hepatitis b virus x protein-mediated upregulation of vegf and mmps. Cancer Investig. 2010;28:443–451. doi: 10.3109/07357900903405959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cheng A.S.L., Chan H.L.Y., Leung W.K., To K.F., Go M.Y.Y., Chan J.Y.H., Liew C.T., Sung J.J.Y. Expression of hbx and cox-2 in chronic hepatitis b, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma: Implication of hbx in upregulation of cox-2. Mod. Pathol. 2004;17:1169–1179. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kongkavitoon P., Tangkijvanich P., Hirankarn N., Palaga T. Hepatitis b virus hbx activates notch signaling via delta-like 4/notch1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0146696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sanz-Cameno P., Martín-Vílchez S., Lara-Pezzi E., Borque M.J., Salmerón J., Muñoz de Rueda P., Solís J.A., López-Cabrera M., Moreno-Otero R. Hepatitis b virus promotes angiopoietin-2 expression in liver tissue: Role of hbv x protein. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:1215–1222. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Majano P.L., García-Monzón C., López-Cabrera M., Lara-Pezzi E., Fernández-Ruiz E., García-Iglesias C., Borque M.J., Moreno-Otero R. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in chronic viral hepatitis. Evidence for a virus-induced gene upregulation. J. Clin. Investig. 1998;101:1343–1352. doi: 10.1172/JCI774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Giannelli G., Bergamini C., Marinosci F., Fransvea E., Quaranta M., Lupo L., Schiraldi O., Antonaci S. Clinical role of mmp-2/timp-2 imbalance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer. 2002;97:425–431. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lara-Pezzi E., Majano P.L., Yáñez-Mó M., Gómez-Gonzalo M., Carretero M., Moreno-Otero R., Sánchez-Madrid F., López-Cabrera M. Effect of the hepatitis b virus hbx protein on integrin-mediated adhesion to and migration on extracellular matrix. J. Hepatol. 2001;34:409–415. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(00)00090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang F., Wang Q., Ye L., Feng Y., Zhang X. Hepatitis b virus x protein upregulates expression of calpain small subunit 1 via nuclear facter-κb/p65 in hepatoma cells. J. Med. Virol. 2010;82:920–928. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin X., Zuo S., Luo R., Li Y., Yu G., Zou Y., Zhou Y., Liu Z., Liu Y., Hu Y., et al. Hbx-induced mir-5188 impairs foxo1 to stimulate β-catenin nuclear translocation and promotes tumor stemness in hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics. 2019;9:7583–7598. doi: 10.7150/thno.37717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang X., Liu S., Hu T., Liu S., He Y., Sun S. Up-regulated microrna-143 transcribed by nuclear factor kappa b enhances hepatocarcinoma metastasis by repressing fibronectin expression. Hepatology. 2009;50:490–499. doi: 10.1002/hep.23008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lara-Pezzi E., Serrador J.M., Montoya M.C., Zamora D., Yáñez-Mó M., Carretero M., Furthmayr H., Sánchez-Madrid F., López-Cabrera M. The hepatitis b virus x protein (hbx) induces a migratory phenotype in a cd44-dependent manner: Possible role of hbx in invasion and metastasis. Hepatology. 2001;33:1270–1281. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang X., Ye L.-h., Zhang X.-d. A mutant of hepatitis b virus x protein (hbxδ127) enhances hepatoma cell migration via osteopontin involving 5-lipoxygenase. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2010;31:593–600. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee T.K., Man K., Poon R.T., Lo C.M., Yuen A.P., Ng I.O., Ng K.T., Leonard W., Fan S.T. Signal transducers and activators of transcription 5b activation enhances hepatocellular carcinoma aggressiveness through induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9948–9956. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang S.Z., Zhang L.D., Zhang Y., Xiong Y., Zhang Y.J., Li H.L., Li X.W., Dong J.H. Hbx protein induces emt through c-src activation in smmc-7721 hepatoma cell line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;382:555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu H., Xu L., He H., Zhu Y., Liu J., Wang S., Chen L., Wu Q., Xu J., Gu J. Hepatitis b virus x protein promotes hepatoma cell invasion and metastasis by stabilizing snail protein. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:2072–2081. doi: 10.1111/cas.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.You H., Yuan D., Bi Y., Zhang N., Li Q., Tu T., Wei X., Lian Q., Yu T., Kong D., et al. Hepatitis b virus x protein promotes vimentin expression via lim and sh3 domain protein 1 to facilitate epithelial-mesenchymal transition and hepatocarcinogenesis. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021;19:33. doi: 10.1186/s12964-021-00714-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]