Added Fructose in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and in Metabolic Syndrome: A Narrative Review (original) (raw)

Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) represents the most common chronic liver disease and it is considered the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome (MetS). Diet represents the key element in NAFLD and MetS treatment, but some nutrients could play a role in their pathophysiology. Among these, fructose added to foods via high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) and sucrose might participate in NAFLD and MetS onset and progression. Fructose induces de novo lipogenesis (DNL), endoplasmic reticulum stress and liver inflammation, promoting insulin resistance and dyslipidemia. Fructose also reduces fatty acids oxidation through the overproduction of malonyl CoA, favoring steatosis. Furthermore, recent studies suggest changes in intestinal permeability associated with fructose consumption that contribute to the risk of NAFLD and MetS. Finally, alterations in the hunger–satiety mechanism and in the synthesis of uric acid link the fructose intake to weight gain and hypertension, respectively. However, further studies are needed to better evaluate the causal relationship between fructose and metabolic diseases and to develop new therapeutic and preventive strategies against NAFLD and MetS.

Keywords: NAFLD, metabolic syndrome, fructose, HFCS

1. Introduction

The relationship between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and metabolic disorders has been widely reported. Fatty liver might be regarded as the hepatic consequence of metabolic syndrome (MetS), a disease including central obesity, hyperglycemia, high blood pressure, hypertriglyceridemia, and low HDL cholesterol levels. Therefore, a strong reciprocal association between NAFLD and MetS has been proposed [1].

The global prevalence of NAFLD and MetS are 24% [2] and 25% [3], respectively. Both conditions are strongly associated with obesity and the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) related liver complications [4,5,6,7,8].

Treatment and prevention of NAFLD and MetS are based on lifestyle intervention. Diet represents a key point for the improvement of MetS and lifestyle correction remains the only therapeutic approach for NAFLD [9]. Guidelines recommend the association of physical activity with caloric restriction, based on the Mediterranean diet, targeting a weight loss of at least 7%, to reduce liver steatosis [10].

Free sugars play a key role in the development of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DMT2), dental caries, metabolic syndrome (MetS), cardiovascular diseases and NAFLD. The World Health Organization suggests an intake of free sugars of less than 10% of the total energy intake [11]. To ensure this, many countries have applied different strategies including the application of a “sugar tax” on high sugar food and soft drinks [12,13].

Free sugars include all available carbohydrates as monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, and galactose) and disaccharides (lactose and sucrose). In particular, the role of fructose, added to foods during industrial processes via high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) and sucrose, is still debated. Although some studies highlight the association between fructose and cardiometabolic diseases, other studies deny this relationship which could be distorted by diet energy surplus.

The aim of this narrative review is to evaluate epidemiological, pathophysiological and clinical evidence on the association between the consumption of added fructose and NAFLD and MetS.

2. Natural and Industrial Sources of Fructose

Fructose is a glucose keto-hexose isomer with higher sweetness than sucrose. The food matrix modifies the effect of fructose on the human body [14,15,16]. Therefore, it is crucial to distinguish the food sources of this nutrient. Natural sources are represented by fruits, vegetables, and honey. Fructose may also be added to food through industrial processes using sucrose or HFCS [15]. The latter represents a valid alternative to sucrose in the food industry as it remains stable within acidic foods and drinks. The two HFCS types used on the market contain 42% and 55% fructose, respectively, and they are used for sodas and other sweetened beverages, candy, processed baked goods and condiments [17].

Furthermore, although the fructose molecule is the same in natural and industrial foods, the health effects appear to be different. This may be caused by the fact that the energy source in the processed product is more concentrated and available to the human body. Furthermore, important components such as fiber, vitamins, mineral salts, or antioxidants are not present in processed foods [18].

3. Metabolic Pathways Involving Fructose

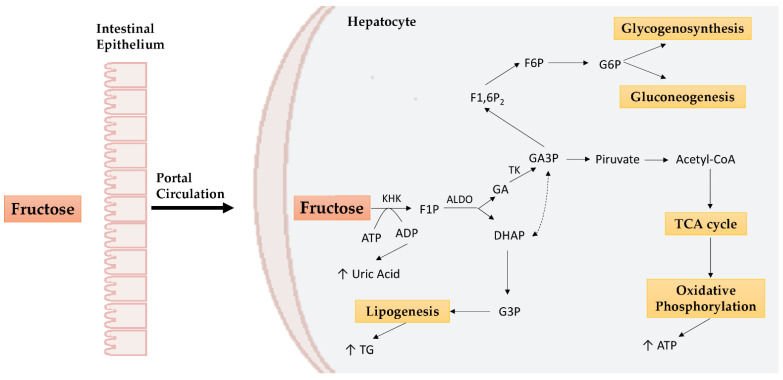

Fructose is passively absorbed in the enterocytes by facilitative glucose transporter 5 (GLUT5) and to a lesser extent by facilitative glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2), which plays a major role in the liver. Most of the fructose, through the portal circulation, reaches the liver and undergoes fructolysis [19]. Fructokinase (KHK) and aldolase B (ALDO) enzymes induce the formation of glyceraldehyde (GA), which will enter the glycolytic or gluconeogenic pathway, and of dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), which will be used to form glycerol, essential for lipogenesis processes (Figure 1) [20]. In addition to KHK and ALDO, triose kinase (TK) plays a crucial role in fructose metabolism by promoting hepatic fat storage and preventing fructolytic substrates’ involvement in oxidative processes via other enzymes (e.g., aldehyde dehydrogenase) [21].

Figure 1.

Hepatic fructose metabolism. In the liver, fructose undergoes KHK phosphorylation to obtain F1P. F1P obtained is metabolized to DHAP and GA by ALDO. DHAP is converted to G3P which enters the lipogenesis mechanisms. On the other hand, GA is converted to GA3P by TK. GA3P can promote lipogenesis after being converted to DHAP, but it can also generate pyruvate, involved, in turn, in the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation to obtain ATP. GA3P is also a precursor of G6P used for gluconeogenesis or glycogenosynthesis. KHK: ketohexokinase; ALDO: aldolase; TK: triose kinase; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; ADP: adenosine diphosphate; F1P: fructose-1-phosphate; DHAP: dihydroxyacetone phosphate; G3P: glycerol 3-phosphate; GA: glyceraldehyde; GA3P: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; F1,6P2: fructose-1,6-bisphosphate; F6P: fructose-6-phosphate; G6P: glucose-6-phosphate; TG: triglycerides; TCA: tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Unlike glucose, whose metabolism is finely regulated by phosphofructokinase, fructose does not undergo this restriction and fructolysis is potentially unlimited. The result is a large amount of substrate which is used in different metabolic pathways (glycolysis, glycogenesis, gluconeogenesis, lipogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation) according to cellular needs. As we will see below, this lack of regulation can promote metabolic alterations [22].

4. Fructose and Metabolic Diseases

The association between fructose consumption and metabolic diseases is debated. The strongest evidence was found with gout [23,24,25] and cardiovascular diseases [26,27,28]. Recently, attention was focused on the study of the pathophysiological mechanisms through which fructose could contribute to the development of MetS and NAFLD.

4.1. Fructose and NAFLD

The close relationship between NAFLD and lifestyle is widely proved. Several studies have reported the damaging or protective effect of different nutrients on liver health. NAFLD patients showed higher glucose and animal protein intake than controls who consumed more dietary fiber [29,30]. A high intake of saturated fatty acids (SFA), cholesterol and lower polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), and vitamins consumption have also been documented in NASH patients [31]. In summary, a “Western diet”, characterized by a high intake of animal foods rich in SFA, trans fatty acids, refined cereals and soft drinks, represents a dietary model strongly associated with NAFLD, MetS, obesity and T2DM [32]. On the other hand, the Mediterranean diet, consisting of plant foods (fruit, vegetables and legumes), whole grains, olive oil and fish consumption, and the reduced intake of processed meat, dairy products, refined cereals and sweets, represents the best recommendation for the management and prevention of NAFLD and MetS [9,10,33]. For example, whole grains have a lower energy density than refined products and promote a greater sense of satiety and a lower overall energy intake [34]. They also influence the intestinal microbiota composition by reducing bacterial endotoxin absorption [35]. Both caloric surplus and bacterial endotoxin levels are positively associated with NAFLD and its complications [36,37].

A regular intake of ω-3 PUFAs (EPA and DHA) would seem to reduce hepatic lipogenesis and counteract insulin resistance and inflammation [38]. Moreover, ω-9 class monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) have shown an improvement in the circulating lipid profile and in insulin resistance, thus suggesting a protective role against NAFLD [39]. Finally, a series of antioxidant compounds (alpha-tocopherol, carotenoids, polyphenols), contained mostly in fruits, vegetables, nuts and olive oil, have effects on the reduction in fatty liver [40].

Added fructose deregulates some physiological mechanisms and promotes liver fat accumulation. However, results are contradictory and might depend on the high energy intake induced by added fructose-rich diets. A meta-analysis revealed the ability of fructose to increase some NAFLD markers following a period of a high fructose high-calorie diet [41]. A 2016 study conducted in Germany on 143 patients showed that fructose consumption was higher in NAFLD patients than in healthy ones, but this difference was not significant when the calories consumed were normalized [29]. According to these data, caloric intake would seem to alter the effect of fructose on NAFLD.

However, Schwarz et al. showed that an intake of fructose equal to 25% of the caloric intake resulted in an increase in hepatic lipogenesis [42]. Furthermore, in patients with NAFLD, an increase in daily fructose intake was strongly associated with low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), greater severity of fibrosis and liver inflammation [43]. Even in young people, an excess of added fructose led to alterations in the lipid profile in both healthy subjects and those with NAFLD [44]. Again, in a large longitudinal study conducted on 2600 participants, the increased consumption of sugary drinks was associated with fatty liver, regardless of possible confounding factors such as the total energy intake [45].

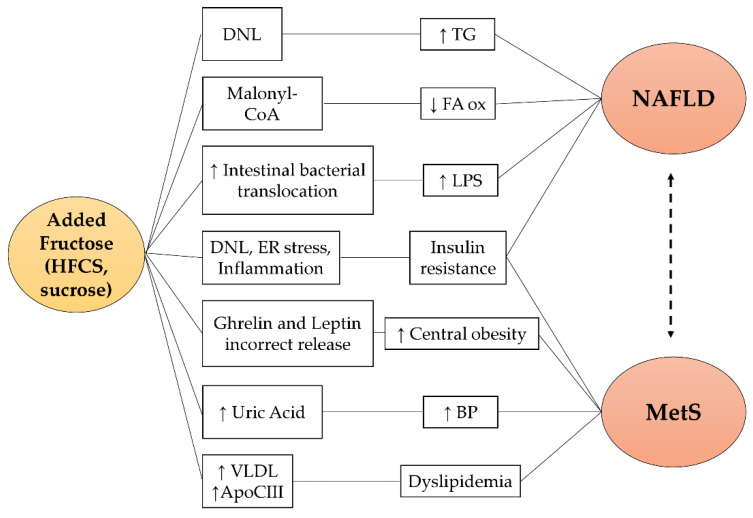

Fructose-related pathogenetic mechanisms for NAFLD are reported in Figure 2. A high fructose content diet induces a greater stimulation of de novo lipogenesis (DNL) due to the increased upregulation of transcription factors (SREBP1c and ChREBP) [46,47]. Concomitantly with the DNL induction, intermediate metabolites of fructolysis directly participate in the lipogenesis processes [20]. In addition, fructose promotes malonyl CoA production which inhibits fatty acids oxidation with consequent hepatic accumulation of triglycerides [48]. Finally, the chronic consumption of fructose alters the balance of the intestinal microbial flora and favors bacterial translocation processes, inducing a high circulating lipopolysaccharide (LPS) concentration [49]. LPS levels have been associated with the presence of NAFLD and the development of liver inflammation and fibrosis [37]. In particular, the increased expression and secretion of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), associated with high endotoxemia, stimulate SREBP1c activation, one of the protagonists of DNL [50]. In addition, in the intestinal lumen, fructose undergoes the gut microbiota action and is converted into acetate, which supplies lipogenic acetyl-CoA independently of the fructolytic metabolic processes [51].

Figure 2.

Fructose-related pathogenetic pathways in NAFLD and MetS. Fructose promotes NAFLD and MetS via different pathways: (1) it acts as a substrate and inducer of hepatic DNL resulting in steatosis and insulin resistance; (2) it is a precursor of malonyl CoA, an inhibitor of fatty acids oxidation; (3) it increases uric acid synthesis which is associated with hypertension; (4) it induces Apo CIII expression and the secretion of VLDL promoting dyslipidemia; (5) it favors intestinal bacterial translocation resulting in elevated serum LPS levels, closely associated with NAFLD; (6) it causes an incorrect regulation of the hunger–satiety mechanism which favors greater caloric intake and weight gain. HFCS: high fructose corn syrup; DNL: de novo lipogenesis; ER stress: endoplasmic reticulum stress; VLDL: very low-density lipoprotein; Apo CIII: apolipoprotein C-III; TG: triglycerides; FA ox: fatty acids oxidation; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; BP: blood pressure; NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; MetS: metabolic syndrome.

Experimental studies demonstrated that eight weeks of a high fructose and sucrose diet induced liver fat accumulation and disease progression in a time of exposure dependent manner [52,53]. Similarly, an observational study performed in a group of young men showed the impaired synthesis of markers of fatty acids after the consumption of sugary drinks with a high fructose content. This effect did not occur for those who consumed sugary drinks rich in sucrose or glucose [54]. Finally, a randomized clinical trial conducted on NAFLD patients showed that 6 weeks of fructose dietary restriction led to a significant reduction in the hepatic lipid content [55].

4.2. Fructose and MetS

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of metabolic disorders, including central obesity, hyperglycemia, arterial hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL-cholesterol, which affects about a quarter of the world’s population [3]. Several studies demonstrate a strong association between MetS and NAFLD, so that the latter has been considered the hepatic expression of MetS [56]. Insulin resistance, the main feature of MetS, is believed to play a central role in the early stages of fatty liver infiltration. However, it is still debated whether insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are components of MetS that promote fatty liver or whether NAFLD itself induces chronic hyperinsulinemia due to reduced insulin breakdown [1].

Fructose shows associations with MetS. Perez-Pozo et al. demonstrated the onset of MetS characteristics in healthy overweight adult men after a fructose daily intake in addition to the usual diet [57]. A cross-sectional study highlighted the link between fructose dietary consumption and MetS components, specifically hyperglycemia, central obesity and hypertriglyceridemia [58]. Considering this, added fructose could be considered a risk factor for MetS as well as for NAFLD.

Insulin resistance and blood glucose alteration have been related to the consumption of soft drinks containing fructose. Kimber et al. demonstrated that the prolonged intake of sugary drinks with fructose worsens insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance [59]. Similar results were obtained by Aeberli et al. who showed a reduction in liver insulin sensitivity following a moderate fructose intake [60]. Nevertheless, different results were obtained from a 24-week RCT in which a diet with a low added fructose content did not improve insulin resistance. However, the study still showed an improvement in fasting blood glucose at the end of the low-fructose diet period [61]. The process underlying the alteration of glucose metabolism might be linked to a condition of hepatic insulin resistance arising from a prolonged exposure to fructose. In the liver, fructose supports de novo lipogenesis (DNL), induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation, leading to a reduction in hepatocytes’ insulin sensitivity [62,63].

In addition to these mechanisms, fructose also takes part in uric acid formation and hyperuricemia, also favored by insulin resistance. In fact, fructose increases uric acid both acutely, via the consumption of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and the degradation of purines, and chronically by stimulating uric acid synthesis [64,65]. This is confirmed by several studies which show fructose’s effect on blood pressure. An observational study conducted in 4000 subjects showed that an intake of added fructose greater than 74 g/day (corresponding to 2.5 soft sugary drinks) was associated with higher values of blood pressure [66]. In 2010, a randomized clinical trial showed a significant increase in blood pressure in subjects who took 200 g/die of diluted fructose in water for two weeks. In particular, the treatment group showed a significant increase in uric acid. In the same work, reducing uric acid with allopurinol authors prevented blood pressure increase [57].

Sugary drinks and added fructose are also associated with dyslipidemia. In particular, 7 days of a high fructose content diet resulted in increased VLDL liver secretion [67]. Saito et al. found that the simultaneous ingestion of drinks containing fructose with a mixture of fats resulted in increased serum triglycerides [68]. Karen L. Teff et al. proved that fructose induced prolonged hypertriglyceridemia, differently from other sugars [69]. The mechanisms by which fructose promotes dyslipidemia involve DNL and the increased expression of Apo CIII. DNL, promoted by fructose through SREBP1c and ChREBP upregulation, is responsible for the increase in serum triglycerides [70]. Apo CIII also causes hypertriglyceridemia, supporting triglyceride mobilization during VLDL assembly and secretion. Finally, Apo CIII impairs the cholesterol efflux capacity of HDL-c particles, worsening the dyslipidemia [71].

Higher levels of added fructose intake were observed in obese patients [58]. In fact, several studies proved the contribution of soft drinks intake to weight gain [72,73,74,75]. Conversely, an interventional study with a low added fructose diet showed an improvement of central obesity [61]. The mechanisms underlying this are independent of the caloric diet surplus and involve insulin, leptin and ghrelin regulation [69]. Fructose intake determines a minimal insulin secretion which is insufficient to stimulate the adipocyte production of leptin. Lack of leptin synthesis prevents the triggering of satiety mechanisms by favoring further food intake [76]. Furthermore, fructose intake could contribute to the lack of ghrelin secretion inhibition. This is always caused by the reduced insulin secretion and glycemic stimulation that occur after fructose ingestion [69]. Lastly, the uncontrolled phosphorylation of fructose leads to an ATP deficit in the liver. In turn, ATP depletion promotes further energy intake through the diet, promoting weight gain [77].

5. Conclusions

The NAFLD and MetS epidemic worsens dangerously every year, along with other metabolic diseases such as diabetes and obesity. Currently, a lifestyle intervention is the best recommendation to improve liver steatosis and nutritional changes also represent the MetS treatment cornerstone.

Further intervention studies are necessary to confirm the causal participation of added fructose in NAFLD and MetS pathogenesis under real life conditions. In particular, it is advisable to avoid potentially confounding factors such as the diet calorie surplus and the excessive amount of fructose administered. This would allow the insertion of another important step in the understanding of the pathogenesis of NAFLD and MetS. However, the data presented in this review are robust and reliable and, in our opinion, a strong warning regarding high fructose food consumption, particularly sugary drinks, must be provided as part of the lifestyle modification for NAFLD patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C. and F.A.; methodology, D.F.; software, M.C.; validation, M.D.B. and F.B.; formal analysis, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing, M.C., D.P., F.A. and F.B.; supervision, M.D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Del Ben M., Polimeni L., Brancorsini M., Di Costanzo A., D’Erasmo L., Baratta F., Loffredo L., Pastori D., Pignatelli P., Violi F., et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome and patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein3 gene variants. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2014;25:566–570. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Younossi Z.M., Koenig A.B., Abdelatif D., Fazel Y., Henry L., Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saklayen M.G. The Global Epidemic of the Metabolic Syndrome. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2018;20:12. doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meroni M., Longo M., Rustichelli A., Dongiovanni P. Nutrition and Genetics in NAFLD: The Perfect Binomium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:2986. doi: 10.3390/ijms21082986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baratta F., Pastori D., Angelico F., Balla A., Paganini A.M., Cocomello N., Ferro D., Violi F., Sanyal A.J., Del Ben M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Fibrosis Associated with Increased Risk of Cardiovascular Events in a Prospective Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;18:2324–2331.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantovani A., Petracca G., Beatrice G., Csermely A., Lonardo A., Schattenberg J.M., Tilg H., Byrne C.D., Targher G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident chronic kidney disease: An updated meta-analysis. Gut. 2022;71:156–162. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwok R., Choi K.C., Wong G.L., Zhang Y., Chan H.L., Luk A.O., Shu S.S., Chan A.W., Yeung M.W., Chan J.C., et al. Screening diabetic patients for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with controlled attenuation parameter and liver stiffness measurements: A prospective cohort study. Gut. 2016;65:1359–1368. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tilg H., Moschen A.R. Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: The multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology. 2010;52:1836–1846. doi: 10.1002/hep.24001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grundy S.M., Stone N.J., Bailey A.L., Beam C., Birtcher K.K., Blumenthal R.S., Braun L.T., de Ferranti S., Faiella-Tommasino J., Forman D.E., et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082–e1143. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2016;64:1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . Guideline: Sugars Intake for Adults and Children. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chriqui J.F., Chaloupka F.J., Powell L.M., Eidson S.S. A typology of beverage taxation: Multiple approaches for obesity prevention and obesity prevention-related revenue generation. J. Public Health Policy. 2013;34:403–423. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2013.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwendicke F., Stolpe M. Taxing sugar-sweetened beverages: Impact on overweight and obesity in Germany. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:88. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3938-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayoub-Charette S., Liu Q., Khan T.A., Au-Yeung F., Blanco Mejia S., de Souza R.J., Wolever T.M., Leiter L.A., Kendall C., Sievenpiper J.L. Important food sources of fructose-containing sugars and incident gout: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ. Open. 2019;9:e024171. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choo V.L., Viguiliouk E., Blanco Mejia S., Cozma A.I., Khan T.A., Ha V., Wolever T.M.S., Leiter L.A., Vuksan V., Kendall C.W.C., et al. Food sources of fructose-containing sugars and glycaemic control: Systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled intervention studies. BMJ. 2018;363:k4644. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semnani-Azad Z., Khan T.A., Blanco Mejia S., de Souza R.J., Leiter L.A., Kendall C.W.C., Hanley A.J., Sievenpiper J.L. Association of Major Food Sources of Fructose-Containing Sugars With Incident Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3:e209993. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White J.S., Hobbs L.J., Fernandez S. Fructose content and composition of commercial HFCS-sweetened carbonated beverages. Int. J. Obes. 2015;39:176–182. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tajima R., Kimura T., Enomoto A., Saito A., Kobayashi S., Masuda K., Iida K. No association between fruits or vegetables and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in middle-aged men and women. Nutrition. 2019;61:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang D.M., Jiao R.Q., Kong L.D. High Dietary Fructose: Direct or Indirect Dangerous Factors Disturbing Tissue and Organ Functions. Nutrients. 2017;9:335. doi: 10.3390/nu9040335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tappy L., Rosset R. Fructose Metabolism from a Functional Perspective: Implications for Athletes. Sports Med. 2017;47:23–32. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu L., Li T., Liao Y., Wang Y., Gao Y., Hu H., Huang H., Wu F., Chen Y.G., Xu S., et al. Triose Kinase Controls the Lipogenic Potential of Fructose and Dietary Tolerance. Cell Metab. 2020;32:605–618.e607. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannou S.A., Haslam D.E., McKeown N.M., Herman M.A. Fructose metabolism and metabolic disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2018;128:545–555. doi: 10.1172/JCI96702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi H.K., Curhan G. Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:309–312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39449.819271.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siqueira J.H., Mill J.G., Velasquez-Melendez G., Moreira A.D., Barreto S.M., Benseñor I.M., Molina M.D.C.B. Sugar-Sweetened Soft Drinks and Fructose Consumption Are Associated with Hyperuricemia: Cross-Sectional Analysis from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) Nutrients. 2018;10:981. doi: 10.3390/nu10080981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pillinger M.H., Abeles A.M. Such sweet sorrow: Fructose and the incidence of gout. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2010;12:77–79. doi: 10.1007/s11926-010-0088-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanhope K.L., Medici V., Bremer A.A., Lee V., Lam H.D., Nunez M.V., Chen G.X., Keim N.L., Havel P.J. A dose-response study of consuming high-fructose corn syrup-sweetened beverages on lipid/lipoprotein risk factors for cardiovascular disease in young adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015;101:1144–1154. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.100461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanhope K.L., Bremer A.A., Medici V., Nakajima K., Ito Y., Nakano T., Chen G., Fong T.H., Lee V., Menorca R.I., et al. Consumption of fructose and high fructose corn syrup increase postprandial triglycerides, LDL-cholesterol, and apolipoprotein-B in young men and women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96:E1596–E1605. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gungor A., Balamtekin N., Ozkececi C.F., Aydin H. The Relationship between Daily Fructose Consumption and Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein and Low-Density Lipoprotein Particle Size in Children with Obesity. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2021;24:483–491. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2021.24.5.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wehmeyer M.H., Zyriax B.C., Jagemann B., Roth E., Windler E., Schulze Zur Wiesch J., Lohse A.W., Kluwe J. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with excessive calorie intake rather than a distinctive dietary pattern. Medicine. 2016;95:e3887. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alferink L.J., Kiefte-de Jong J.C., Erler N.S., Veldt B.J., Schoufour J.D., de Knegt R.J., Ikram M.A., Metselaar H.J., Janssen H., Franco O.H., et al. Association of dietary macronutrient composition and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in an ageing population: The Rotterdam Study. Gut. 2019;68:1088–1098. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Musso G., Gambino R., De Michieli F., Cassader M., Rizzetto M., Durazzo M., Fagà E., Silli B., Pagano G. Dietary habits and their relations to insulin resistance and postprandial lipemia in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2003;37:909–916. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hosseini Z., Whiting S.J., Vatanparast H. Current evidence on the association of the metabolic syndrome and dietary patterns in a global perspective. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2016;29:152–162. doi: 10.1017/S095442241600007X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willett W.C., Sacks F., Trichopoulou A., Drescher G., Ferro-Luzzi A., Helsing E., Trichopoulos D. Mediterranean diet pyramid: A cultural model for healthy eating. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995;61:1402S–1406S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.6.1402S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giacco R., Della Pepa G., Luongo D., Riccardi G. Whole grain intake in relation to body weight: From epidemiological evidence to clinical trials. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011;21:901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bailey M.A., Holscher H.D. Microbiome-Mediated Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Inflammation. Adv. Nutr. 2018;9:193–206. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmy013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mundi M.S., Velapati S., Patel J., Kellogg T.A., Abu Dayyeh B.K., Hurt R.T. Evolution of NAFLD and Its Management. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2020;35:72–84. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carpino G., Del Ben M., Pastori D., Carnevale R., Baratta F., Overi D., Francis H., Cardinale V., Onori P., Safarikia S., et al. Increased Liver Localization of Lipopolysaccharides in Human and Experimental NAFLD. Hepatology. 2020;72:470–485. doi: 10.1002/hep.31056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Minno M.N., Russolillo A., Lupoli R., Ambrosino P., Di Minno A., Tarantino G. Omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5839–5847. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i41.5839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Priore P., Cavallo A., Gnoni A., Damiano F., Gnoni G.V., Siculella L. Modulation of hepatic lipid metabolism by olive oil and its phenols in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. IUBMB Life. 2015;67:9–17. doi: 10.1002/iub.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Godos J., Federico A., Dallio M., Scazzina F. Mediterranean diet and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Molecular mechanisms of protection. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017;68:18–27. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2016.1214239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiu S., Sievenpiper J.L., de Souza R.J., Cozma A.I., Mirrahimi A., Carleton A.J., Ha V., Di Buono M., Jenkins A.L., Leiter L.A., et al. Effect of fructose on markers of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014;68:416–423. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwarz J.M., Noworolski S.M., Wen M.J., Dyachenko A., Prior J.L., Weinberg M.E., Herraiz L.A., Tai V.W., Bergeron N., Bersot T.P., et al. Effect of a High-Fructose Weight-Maintaining Diet on Lipogenesis and Liver Fat. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;100:2434–2442. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abdelmalek M.F., Suzuki A., Guy C., Unalp-Arida A., Colvin R., Johnson R.J., Diehl A.M., Network N.S.C.R. Increased fructose consumption is associated with fibrosis severity in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:1961–1971. doi: 10.1002/hep.23535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jin R., Le N.A., Liu S., Farkas Epperson M., Ziegler T.R., Welsh J.A., Jones D.P., McClain C.J., Vos M.B. Children with NAFLD are more sensitive to the adverse metabolic effects of fructose beverages than children without NAFLD. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97:E1088–E1098. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma J., Fox C.S., Jacques P.F., Speliotes E.K., Hoffmann U., Smith C.E., Saltzman E., McKeown N.M. Sugar-sweetened beverage, diet soda, and fatty liver disease in the Framingham Heart Study cohorts. J. Hepatol. 2015;63:462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dekker M.J., Su Q., Baker C., Rutledge A.C., Adeli K. Fructose: A highly lipogenic nutrient implicated in insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, and the metabolic syndrome. Am. J. Physiol Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;299:E685–E694. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00283.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herman M.A., Samuel V.T. The Sweet Path to Metabolic Demise: Fructose and Lipid Synthesis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;27:719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGarry J.D. Banting lecture 2001: Dysregulation of fatty acid metabolism in the etiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:7–18. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perdomo C.M., Frühbeck G., Escalada J. Impact of Nutritional Changes on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients. 2019;11:677. doi: 10.3390/nu11030677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Todoric J., Di Caro G., Reibe S., Henstridge D.C., Green C.R., Vrbanac A., Ceteci F., Conche C., McNulty R., Shalapour S., et al. Fructose stimulated de novo lipogenesis is promoted by inflammation. Nat. Metab. 2020;2:1034–1045. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-0261-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao S., Jang C., Liu J., Uehara K., Gilbert M., Izzo L., Zeng X., Trefely S., Fernandez S., Carrer A., et al. Dietary fructose feeds hepatic lipogenesis via microbiota-derived acetate. Nature. 2020;579:586–591. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2101-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sánchez-Lozada L.G., Mu W., Roncal C., Sautin Y.Y., Abdelmalek M., Reungjui S., Le M., Nakagawa T., Lan H.Y., Yu X., et al. Comparison of free fructose and glucose to sucrose in the ability to cause fatty liver. Eur. J. Nutr. 2010;49:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00394-009-0042-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schultz A., Neil D., Aguila M.B., Mandarim-de-Lacerda C.A. Hepatic adverse effects of fructose consumption independent of overweight/obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:21873–21886. doi: 10.3390/ijms141121873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hochuli M., Aeberli I., Weiss A., Hersberger M., Troxler H., Gerber P.A., Spinas G.A., Berneis K. Sugar-sweetened beverages with moderate amounts of fructose, but not sucrose, induce Fatty Acid synthesis in healthy young men: A randomized crossover study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99:2164–2172. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simons N., Veeraiah P., Simons P.I.H.G., Schaper N.C., Kooi M.E., Schrauwen-Hinderling V.B., Feskens E.J.M., van der Ploeg E.M.C.L., Van den Eynde M.D.G., Schalkwijk C.G., et al. Effects of fructose restriction on liver steatosis (FRUITLESS); a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021;113:391–400. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Angelico F., Del Ben M., Conti R., Francioso S., Feole K., Maccioni D., Antonini T.M., Alessandri C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver syndrome: A hepatic consequence of common metabolic diseases. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2003;18:588–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.02958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perez-Pozo S.E., Schold J., Nakagawa T., Sánchez-Lozada L.G., Johnson R.J., Lillo J.L. Excessive fructose intake induces the features of metabolic syndrome in healthy adult men: Role of uric acid in the hypertensive response. Int. J. Obes. 2010;34:454–461. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chan W., Smith B., Stegall M., Borrows R. Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome in Kidney Transplantation: The Role of Dietary Fructose and Systemic Endotoxemia. Transplantation. 2019;103:191–201. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stanhope K.L., Schwarz J.M., Keim N.L., Griffen S.C., Bremer A.A., Graham J.L., Hatcher B., Cox C.L., Dyachenko A., Zhang W., et al. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2009;119:1322–1334. doi: 10.1172/JCI37385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aeberli I., Hochuli M., Gerber P.A., Sze L., Murer S.B., Tappy L., Spinas G.A., Berneis K. Moderate amounts of fructose consumption impair insulin sensitivity in healthy young men: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:150–156. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Domínguez-Coello S., Carrillo-Fernández L., Gobierno-Hernández J., Méndez-Abad M., Borges-Álamo C., García-Dopico J.A., Aguirre-Jaime A., León A.C. Decreased Consumption of Added Fructose Reduces Waist Circumference and Blood Glucose Concentration in Patients with Overweight and Obesity. The DISFRUTE Study: A Randomised Trial in Primary Care. Nutrients. 2020;12:1149. doi: 10.3390/nu12041149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jegatheesan P., De Bandt J.P. Fructose and NAFLD: The Multifaceted Aspects of Fructose Metabolism. Nutrients. 2017;9:230. doi: 10.3390/nu9030230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith G.I., Shankaran M., Yoshino M., Schweitzer G.G., Chondronikola M., Beals J.W., Okunade A.L., Patterson B.W., Nyangau E., Field T., et al. Insulin resistance drives hepatic de novo lipogenesis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2020;130:1453–1460. doi: 10.1172/JCI134165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Le M.T., Frye R.F., Rivard C.J., Cheng J., McFann K.K., Segal M.S., Johnson R.J., Johnson J.A. Effects of high-fructose corn syrup and sucrose on the pharmacokinetics of fructose and acute metabolic and hemodynamic responses in healthy subjects. Metabolism. 2012;61:641–651. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi H.K., Willett W., Curhan G. Fructose-rich beverages and risk of gout in women. JAMA. 2010;304:2270–2278. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jalal D.I., Smits G., Johnson R.J., Chonchol M. Increased fructose associates with elevated blood pressure. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;21:1543–1549. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009111111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lê K.A., Ith M., Kreis R., Faeh D., Bortolotti M., Tran C., Boesch C., Tappy L. Fructose overconsumption causes dyslipidemia and ectopic lipid deposition in healthy subjects with and without a family history of type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009;89:1760–1765. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saito H., Kagaya M., Suzuki M., Yoshida A., Naito M. Simultaneous ingestion of fructose and fat exacerbates postprandial exogenous lipidemia in young healthy Japanese women. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2013;20:591–600. doi: 10.5551/jat.17301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Teff K.L., Elliott S.S., Tschöp M., Kieffer T.J., Rader D., Heiman M., Townsend R.R., Keim N.L., D’Alessio D., Havel P.J. Dietary fructose reduces circulating insulin and leptin, attenuates postprandial suppression of ghrelin, and increases triglycerides in women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;89:2963–2972. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stanhope K.L., Griffen S.C., Bair B.R., Swarbrick M.M., Keim N.L., Havel P.J. Twenty-four-hour endocrine and metabolic profiles following consumption of high-fructose corn syrup-, sucrose-, fructose-, and glucose-sweetened beverages with meals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;87:1194–1203. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hieronimus B., Stanhope K.L. Dietary fructose and dyslipidemia: New mechanisms involving apolipoprotein CIII. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2020;31:20–26. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schulze M.B., Manson J.E., Ludwig D.S., Colditz G.A., Stampfer M.J., Willett W.C., Hu F.B. Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA. 2004;292:927–934. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Twarog J.P., Peraj E., Vaknin O.S., Russo A.T., Woo Baidal J.A., Sonneville K.R. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and obesity in SNAP-eligible children and adolescents. Prim. Care Diabetes. 2020;14:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Berkey C.S., Rockett H.R., Field A.E., Gillman M.W., Colditz G.A. Sugar-added beverages and adolescent weight change. Obes. Res. 2004;12:778–788. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Miller C., Ettridge K., Wakefield M., Pettigrew S., Coveney J., Roder D., Durkin S., Wittert G., Martin J., Dono J. Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages, Juice, Artificially-Sweetened Soda and Bottled Water: An Australian Population Study. Nutrients. 2020;12:817. doi: 10.3390/nu12030817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Crujeiras A.B., Carreira M.C., Cabia B., Andrade S., Amil M., Casanueva F.F. Leptin resistance in obesity: An epigenetic landscape. Life Sci. 2015;140:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bawden S.J., Stephenson M.C., Ciampi E., Hunter K., Marciani L., Macdonald I.A., Aithal G.P., Morris P.G., Gowland P.A. Investigating the effects of an oral fructose challenge on hepatic ATP reserves in healthy volunteers: A (31)P MRS study. Clin. Nutr. 2016;35:645–649. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]