Совместимые альтернативы? О затоплении кораблей Черноморского флота в 1918 году (original) (raw)

Подборка архивных публикаций по годам

Совместимые альтернативы? О затоплении кораблей Черноморского флота в 1918 году

Тихменев, как известно, проведя голосование на флоте – как следует поступить с кораблями, затопить или вернуть в Севастополь, – и не получив однозначных результатов, принял решение выполнить указание того текста телеграммы, который был открытым. Отсюда можно сделать парадоксальный вывод, что именно решение Тихменева о возвращении флота в Севастополь спасло большевиков от нападения немцев на Новороссийск.

В октябре 1925 года со дна Цемесской бухты Новороссийска силами советского ЭПРОНа был поднят эсминец дореволюционного Черноморского флота «Калиакрия». Он оказался единственным кораблем из еще построенных в эпоху Российской империи, который вошел в качестве боевой единицы в Черноморский флот Советского Союза (переименован в «Дзержинский»; кроме того, было еще заложенных 3 эскадренных миноносца и 1 крейсер, которые достроили в советское время), символически связав собой два исторических периода – дореволюционный и советский, а, значит, и современный, ведь нынешний российский Черноморский флот – наследник флота советского.

«Калиакрия», а также другие 8 эсминцев и 1 линкор Черноморского флота были затоплены собственными командами 18 июня 1918 года по секретному требованию советского правительства во избежание захвата кораблей немцами – всего полтора месяца простояли они в Новороссийске после срочной эвакуации из Севастополя, захваченного немцами 1 мая 1918 года.

Командир эсминца Керчь Владимир Кукель, возглавивший процесс затопления кораблей

Во многих публикациях затопление кораблей 18 июня 1918 года в Цемесской бухте называется гибелью флота. Возможно, традиция такого наименования идет из самых известных и по сей день воспоминаний – книги 1923 года под названием «Правда о гибели Черноморского флота» командира эсминца «Керчь» Владимира Кукеля, руководившего процессом затопления. Для общественного же восприятия большую роль сыграла пьеса 1933 года «Гибель эскадры» Александра Корнейчука, по которой был в 1965 году был снят одноименный фильм: и это произведение также героизировало тех, кто пошел на затопление своих кораблей, ассоциируя с ними «флот» как таковой.

Однако, как известно, чуть меньше половины кораблей (6 миноносцев и 1 линкор), стоявших в Новороссийске, отказалось совершать самоподрыв и во главе с и.о. командующего флота Александром Тихменевым предпочло вернуться в Севастополь, находившемуся тогда под немецкой оккупацией.

Кроме того, более точным будет утверждение, что весной-летом 1918 года флот оказался расколот даже не на две части, а на три.

Этой третьей частью – были те, кто вовсе не покидал Севастополь: некоторые корабли в момент эвакуации не смогли выйти из бухты, попав под немецкий обстрел, какие-то находились в нерабочем состоянии, а на каких-то судах команды разбежались.

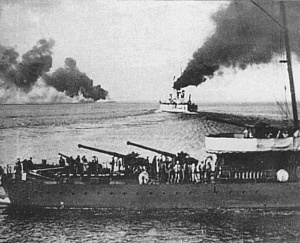

Эсминец «Керчь» провожает уходящий из Новороссийска в Севастополь линкор «Воля», 17 июня 1918 года.

Строго говоря, в эвакуации из Севастополя в Новороссийск в апреле 1918 года в количественном выражении приняло участие чуть ли не меньше половины флота: в Новороссийск ушло 2 линкора и 16 миноносцев, осталось в Севастополе – 7 линкоров и 12 миноносцев, а также все крейсеры (3) и подводные лодки (15), общая же численность не вышедших из порта составляла порядка 170 судов. Правда, ушедшая часть флота была более современной и находилась в лучшем боевом состоянии.

Так или иначе говорить о том, что в конце апреля 1918 года в Новороссийск был эвакуирован весь флот, а в июне того же года этот флот погиб – не приходится.

После окончания Первой мировой войны в ноябре 1918 года и ухода немцев из Севастополя, все незатопленные корабли оказались под властью так называемых союзников по Антанте, которые первоначально их присвоили себе и частично вообще увели из Севастопольского порта. Однако в дальнейшем многие корабли белым удалось вернуть в занятый ими Севастополь. И именно эти корабли-остатки Черноморского флота сделали возможной врангелевскую эвакуацию – «русский исход» ноября 1920 года.

Эвакуация Петра Врангеля завершилась в порту французской колонии Тунис – Бизерте, куда остатки Черноморского флота под названием Русская эскадра прибыли в феврале 1921 года.

В октябре 1924 года Франция признала Советский Союз, и тут же советской стороной был поставлен вопрос о «возвращении» уплывшей «собственности» из Бизерты в Севастополь. Главным лоббистом этого «возвращения» был военный атташе СССР Евгений Беренс (я о нем уже писала), который в 1918 году, будучи начальником Морского генерального штаба при большевиках, по сути, первым выдвинул и обосновал идею необходимости затопления Черноморского флота в Цемесской бухте.

И пока советские дипломаты во второй половине 1920-х годов пытались добиться разрешения на транспортировку кораблей из Бизерты в Севастополь, на дне Цемесской бухты Новороссийска искали их затопленных собратьев.

Попытка «вернуть» из Франции в Севастополь «собственность советской республики» оказалась безрезультатной, в итоге, советский Черноморский флот создавался в прямом смысле слова с нуля. За исключением «Калиакрии», другие поднятые целиком или частично миноносцы оказались не пригодны к боевой службе. Аналогичной оказалась судьба и их незатопленных собратьев, боевая биография которых закончилась с «русским исходом». И пока в Советском Союзе разбирали на части поднятые со дна Цемесской бухты корабли, в Бизерте Русская эскадра была постепенно распилена французами на металлолом.

К началу 1930-х годов все корабли, за исключением одного, относящиеся к Черноморскому флоту Российской империи, создававшиеся на протяжении полувека после знаменитого затопления кораблей в Севастопольской бухте в годы Крымской войны, – и ушедшие в эмиграцию, и затопленные у Новороссийска – физически исчезли.

За пределами идеологического раскола

В судьбе кораблей Черноморского флота в годы гражданской войны проявилось то же раздвоение, те два вектора, напряжение между которыми составляет чуть ли не основную драматическую контроверзу отечественной истории ХХ века, о котором я писала в статье о братьях – морских офицерах Евгении и Михаиле Беренсах. Одни корабли (как и люди), согласно логике государственной необходимости, выбрали судьбу той части флота, что была затоплена в Цемесской бухте 18 июня 1918 года; другие подчинились логике спасения кораблей, и, как оказалось в дальнейшем, и людей.

История раскола Черноморского флота и затопления его части в июне 1918 года во всех мемуарных свидетельствах объясняется через идеологическое противостояние. С «белой» стороны – это воспоминания Николая Гутана и Нестора Монастырева, со стороны «красной» – воспоминания Владимира Кукеля, Федора Раскольникова, Василия Жукова, М.М. Лучина, Савелия Сапронова. И тем, кто затопил флот, и тем, кто вернулся в Севастополь, в литературе, как советской (А.И. Козлов, И.Т. Сирченко), так и постсоветской (А.П. Павленко, С. Войтиков, А. Пученков), приписываются идеологические мотивы. Однако в действительности, эта история выходит за пределы проблематики идеологического конфликта и вообще темы братоубийственной гражданской войны между красными и белыми.

Линкор Воля в Южной бухте Севастополя во время германской оккупации, лето 1918 года

Так, ни в одной советской директиве о необходимости затопить флот ни разу не упоминались «белогвардейцы», «контрреволюционные элементы» и т.п. (тексты директив подробно цитируются в статье 1984 года А.И. Козлова). Хотя, скажем, в феврале 1918 года угроза «контрреволюции», «соглашательства» и «саботажа» на Черноморском флоте была важным лейтмотивом телеграмм севастопольскому Военно-революционному комитету из центра – как показывает историк Сергей Войтиков в только что вышедшей книге «Брестский мир и гибель Черноморского флота», эти телеграммы предшествовали убийствам и самосудным расстрелам морских офицеров 22 – 24 февраля в Севастополе. Однако во всех указаниях, шедших от советского правительства весной 1918 года первоначально в Севастополь – с требованиями эвакуации в Новороссийск, а затем – в Новороссийск с приказами затопить флот, речь шла только о германской угрозе.

Идея затопления флота вызывала явно неоднозначное отношение в среде большевиков, причем как центрального руководства, так и на местах. Во всяком случае внутренняя среда большевистского руководства была далека от «ура-патриотизма» по этому поводу, всеми это воспринималось как крайне тяжелый, трагический и практический невыполнимый шаг. Посланные из Москвы в Новороссийск в конце мая 1918 года для руководства процессом затопления член коллегии Наркомата по морским делам Иван Вахрамеев и назначенный тогда же главным комиссаром Черноморского флота Николай Авилов-Глебов не смогли объяснить командам необходимость затопления кораблей и в какой-то момент они, по сути, сбежали в Екатеринодар. Там они присоединились к местному руководству только что созданной Кубано-Черноморской советской республики, которое буквально умоляло, как пишет историк Александр Пученков, и центр, и матросов не топить корабли, необходимые для защиты республики от тех же немцев, оккупировавших 1 мая 1918 года Таганрог.

Уклонился от распоряжения вмешаться в ситуацию нарком по делам национальностей РСФСР, находившийся на Северном Кавказе и вскоре назначенный председателем Военного совета Северо-Кавказского военного округа Иосиф Сталин. Сталин передоверил это вмешательство Александру Шляпникову, на конец весны 1918 года – особо-уполномоченному СНК по продовольствию на Северном Кавказе. Однако и Шляпников проигнорировал поручение центра.

Белые, в свою очередь, как пишет А. Пученков, никогда не ставили в упрек большевикам затопление кораблей Черноморского флота, признавая государственную необходимость такого шага. Отнюдь не сторонник советской власти контр-адмирал Михаил Саблин, согласившийся возглавить Черноморский флот в конце апреля 1918 года и выпущенный поэтому большевиками из тюрьмы, под руководством которого корабли и были эвакуированы в Новороссийск, разделял представление о необходимости затопления флота в Цемесской бухте во избежание попадания его в руки немцев. По мнению С. Войтикова, Саблин психологически не мог сам отдать распоряжение о затоплении, поэтому, по сути, сбежал из Новороссийска в Москву «для разъяснения обстоятельств затопления флота». Однако узнав, что оставленный им на посту и.о. командующего флотом Александр Тихменев отдал флоту приказ возвращаться в Севастополь, послал ему телеграмму, в которой назвал действия Тихменева предательством (в Москве Саблин был арестован, но бежал, и в дальнейшем возглавлял флот при белом правительстве Врангеля).

Мемуарные описания реакции населения на затопление судов в Цемесской бухте также не соответствуют традиционной «красно-белой» градации. Так, «белый» офицер Николай Гутан отмечал в воспоминаниях, что толпа, собравшаяся на пристани, была однозначно настроена против тех, кто решил возвращаться в Севастополь под руководством Тихменева (т.е. была против условных «белых»). А автор первой советской работы об истории затопления флота большевик Василий Жуков, напротив, сообщил о народном возмущении теми, кто решил затопить свои корабли (т.е. против сторонников большевиков). При этом оба мемуариста совпадали в том, что в толпе доминировали настроения мародерства в отношении корабельного имущества.

Да и само деление команд и морских офицеров на тех, кто решил затопить свои корабли, и тех, кто вернулся в Севастополь под власть немцев, также явно не проходит исключительно по критерию: поддержка большевиков и патриотизм – в первом случае и украинофильство вкупе с «белогвардейщиной» и отсутствием патриотической мотивации – во втором.

Вся эта история на самом деле распадается на два этапа – эвакуация флота из Севастополя в Новороссийск в конце апреля 1918 года и возвращение части кораблей из Новороссийска в Севастополь в середине июня того же года.

Как известно, корабли уходили от немцев из Севастополя в Новороссийск двумя партиями.

29 апреля 1918 года снялись современные эскадренные миноносцы-нефтяники. По наиболее полным подсчетам историка Екатерины Алтабаевой в книге «Смутное время. Севастополь в 1917 – 1920 гг.», их было 11, с ними же ушли 3 миноносца старого типа. Эту группу неформально возглавил эсминец «Керчь» и его командир Кукель, ставший позднее, в июне 1918 года, главным сторонником среди команды флота его затопления. 30 апреля под руководством Саблина, до последнего надеявшегося, что удастся обмануть немцев, подняв на кораблях украинские флаги (это означало, что флот признает юрисдикцию Украины и не попадает под немецкую оккупацию), ушла вторая группа кораблей – 2 новейших линкора, гордость Черноморского флота, и 2 эсминца. 3-й эсминец подорвался на мине, подвергся обстрелу, не смог выйти в море и вернулся в Севастополь, где в полузатопленном состоянии был оставлен командой, а 4-й эсминец, также планировавший уйти с Саблиным, даже не стал пробовать, сразу подорвав себя на рейде.

Обычно говорится о том, что первыми из Севастополя ушли более революционные корабли во главе с Кукелем (именно на этом настаивал сам Кукель в воспоминаниях), в то время как медлили уходить корабли с «контр-революционными» командами. Соответственно, те, кто в апреле 1918 года ушел из Севастополя первым, и был в большей степени склонен в июне того же года выполнить приказ Советской власти о затоплении флота.

Однако сопоставление списков кораблей показывает, что 4 из 11 эсминцев и 1 из 3 миноносцев первой партии вернулись в Севастополь вместе с Тихменевым, в то время как 1 из 2 линкоров из второй партии – «Свободная Россия» – остался для затопления, а его команда попросту разбежалась. Среди вернувшихся в Севастополь был, помимо других кораблей, эсминец «Капитан Сакен», который возглавлял большевик Савелий Сапронов (возможно, на момент затопления Сапронов уже не был командиром этого эсминца, но в Новороссийск «Капитан Сакен» пришел под его началом).

Более того. Группа, ушедшая из Севастополя первой, по инициативе и под началом Кукеля, как ясно из статьи советского историка А.Козлова, приняла решение об эвакуации в Новороссийск 28 апреля, но подготовка к эвакуации заняла какое-то время, и корабли отплыли только на следующий день. Это означает, что группа Кукеля запланировала собственную эвакуацию до того, как в город начали прибывать отступающие под натиском немцев красноармейские части, организованные для обороны города и Крыма большевиком Юрием Гавеном, а прибытие этих частей началось 29 апреля. Неизвестно, на какие корабли погрузились эти части, можно предположить, что на более вместительные линкоры, ушедшие с Саблиным 30 апреля.

В этом случае «задержка» «контрреволюционного» командующего флотом в Севастополе получает еще одно объяснение. Вероятно, он ждал не только ответа германского командования на посланную им делегацию, но и погрузку на корабли тех людей, в том числе пришедших с фронта, которые хотели уйти из-под неожиданной для города немецкой оккупации вместо ожидавшегося в Севастополе появления войск относительно «дружественной» Украинской народной республики (смена УНР на поставленное немцами правительство гетмана Павла Скоропадского произошла в эти же дни, 28 – 29 апреля, и, конечно, в Севастополе об этом просто не знали, впрочем, группа Петра Болбочана была послана на захват Крыма еще при власти УНР).

Есть и еще один нюанс, показывающий, что далеко не всё в годы гражданской войны определялось партийным размежеванием, и что достойные люди были на всех фронтах и во всех лагерях. Под натиском внешней военной угрозы – захвата Крыма и Севастополя хоть украинцами, хоть немцами – разным властям в Севастополе в общем-то удалось договориться между собой, что делать с флотом. При том что сама возможность договоренности была совсем не очевидной в условиях многопартийных севастопольского Совета и Центрофлота при наличии преимущественно большевистского Военно-революционного комитета, дискредитировавшего себя в городе расправами над офицерами флота в феврале 1918 года (от которых сам комитет, правда, отмежевался). Тем не менее, несмотря на острые разногласия и борьбу за власть друг с другом, большевики смогли организовать оборону города, а Центрофлот взял на себя координацию с центральным правительством, при том, что был, скорее, противником большевистского центрального Совета народных комиссаров.

Показательно и то, что местные большевики с рвением и настойчивостью взялись за организацию обороны города от немцев – шаг, безусловно, патриотичный, однако не только бессмысленный со строго военной точки зрения, но и шедший в разрез с центральными директивами советской власти, настаивавшей на соблюдении условий Брестского мира.

Крупная карта в «большой игре»

Статья 5 Брестского мира, подписанного 3 марта 1918 года, гласила: «Россия незамедлительно произведет полную демобилизацию своей армии, включая и войсковые части, вновь сформированные теперешним правительством. Кроме того, свои военные суда Россия либо переведет в русские порты и оставит там до заключения всеобщего мира, либо немедленно разоружит_». Также в Брестском договоре прописывалось обязательство «_России … _немедленно заключить мир с Украинской народной республикой и признать мирный договор между этим государством и державами четверного союза. Территория Украины незамедлительно очищается от русских войск и русской красной гвардии_». Границы Украины в Брестском договоре не оговаривались, однако Крым и Севастополь, очевидно, рассматривались как русские территории – во всяком случае, их упоминание отсутствует в договорах Украинской народной республики с «державами четверного союза».

В совокупности это означало, что Черноморский флот нужно «разоружить» либо содержать в «русских портах… до заключения всеобщего мира». Логично было предположить, что речь идет о Севастополе, где и базировался Черноморский флот. Однако, судя по всему, советское правительство после подписания мира не обязало тут же местные власти (в первую очередь, Центрофлот как главную на тот момент структуру управления флотом) начать его разоружение.

Развернувшееся же военное развертывание немцев по территории подконтрольной им Украины с угрозой занятия Крыма и Севастополя (немецкие войска вышли к Перекопу 5 апреля 1918 года) вызвало и вовсе противоречивую реакцию большевиков в центре, причем эта противоречивость была замечена участниками событий в Севастополе, о чем по понятным причинам умалчивает советская мемуаристика и научная литература и что по причинам менее понятным игнорируют и современные исследователями. Понятно, что управление большевиками даже тех районов, где признали советскую власть, на начальном этапе было хаотичным, но думается дело не только в этом.

25 марта Наркомат по морским делам, в котором при Льве Троцком важную роль играл «старый военспец» контр-адмирал Василий Альтфатер, принял решение о «немедленном вывозе» из Севастополя в Новороссийск «запасов и грузов».

27 марта также «старый военспец», хороший знакомый Альтфатера по предшествующей службе на флоте, ставший при большевиках первым начальником Морского генерального штаба уже упоминавшийся Е. Беренс прислал в Севастополь телеграмму, в которой требовал готовить к «немедленной эвакуации» не только «запасы и имущество флота», но и все корабли, включая ремонтируемые и неисправные, т.к. «слабость наших сил не может обеспечить Крыма от захвата его австро-германскими войсками». О Брестском мире как первопричине эвакуации Беренс не упоминал.

На ответ командующего Черноморским флотом Саблина, что небольшой торговый Новороссийский порт не предназначен для размещения боевого флота, пришло следующее разъяснение Наркомата по морским делам: «_Раз мир подписан и мирный договор ратифицирован, то нужно принять и все вытекающие отсюда выводы, в силу прекращения военных действий Черноморский флот, входящий в состав вооруженных сил государства, подписавшего мирный договор, также не должен принимать участия в военных действиях. Неосмотрительные действия в данном случае могли бы повлечь за собой срыв мира и объявление нам новой войны_».

Получается, что Беренс мотивировал эвакуацию флота невозможностью ведения эффективных военных действий, а морской Наркомат – необходимостью неукоснительно соблюдать их прекращение, как того требовал Брестский договор (хотя Брестский договор требовал разоружения флота). Однако уже в следующей телеграмме Наркомата речь шла именно об эвакуации, и объяснялось это – как ранее Беренсом – слабостью наличных сил: «_Эвакуацию нужно производить исключительно потому, что Тавриде грозит опасность наступления австро-германских войск. Мирным договором это не предусмотрено, но немцы могут сделать поползновение рассматривать Севастополь как город Украины, и, так как у Высшего Военного Совета нет гарантий, что наши войска не допустят овладеть городом, то предусмотрительно приходится уводить флот из Севастополя_».

Спустя две недели, когда немцы вовсю занимали Крымский полуостров, Совет народных комиссаров уже сам предлагал организовать военное сопротивление, настаивая, впрочем, не столько на обороне, сколько на эвакуации кораблей: «_Совнарком предлагает Черноморфлоту оказать энергичное сопротивление захвату Севастополя, а в случае невозможности удержать Севастополь, со всеми судами, могущими выйти в море, перейти [в] Новороссийск, уничтожив все остающиеся [в] Севастополе суда, имущество и запасы_».

Однако в Севастополе требование эвакуации флота с различными мотивировками наталкивалось на устойчивое недоумение. Вероятно, отчасти дело было в том, что местные органы власти (севастопольские советы разных составов), включая флотские (Центрофлот), были многопартийными, причем в них входили не только эсеры и меньшевики, но и большое количество беспартийных. В результате на заседаниях Центрофлота поднимался вопрос, зачем вообще Черноморскому флоту соблюдать Брестский мир, подписанный большевиками. В другой раз была послана телеграмма обратного содержания – рассматривается ли Севастополь в центре как «русский порт», и если да, то почему на него не распространяются положения Брестского мира о «разоружении», а вместо этого Москва требует эвакуации. При этом на самом флоте преобладали настроения на борьбу с врагом до конца, даже если эта борьба не сможет увенчаться победой. Из книги В. Жукова складывается впечатление, что моряки вообще не понимали, зачем нужно эвакуироваться, если не было еще ни одной попытки дать немцам отпор[1].

Параллельно этому большевики вели сложную игру по вытеснению из местных органов власти «соглашателей» – так, ими была создана Таврическая советская республика, председателем местного СНК которой стал старый большевик Антон Слуцкий (все правительство было расстреляно крымско-татарскими националистами 24 апреля 1918 года). Севастополь не был назван в составе территории этой республики, думается, по одной причине – тогда деньги на эвакуацию Черноморского флота пришлось бы выдавать Центрофлоту, однако Совнарком объявил представителю Центрофлота эсеру Виллияму Спиро, что финансирование эвакуации будет осуществляться через Таврическую республику.

Как только немцы заняли Севастополь, они тут же выдвинули требование вернуть флот на место его постоянной дислокации. В ответ руководство большевиков стало использовать факт отсутствия флота в Севастополе как козырь в дипломатической игре с Германией, из чего можно сделать вывод, что и само по себе требование эвакуации флота в Новороссийск было частью какой-то большой игры.

Так, советские дипломатические представители (Георгий Чичерин, Адольф Иоффе) по указанию Ленина в мае 1918 года неоднократно сообщали Германии, что флот может быть возвращен в Севастополь (под власть немцев), «если будет заключен мир с Финляндией, Украиной, Турцией и если Германия будет его соблюдать».

Однако пока шел этот торг, 23 мая 1918 года начальник Морского генштаба Беренс написал, а Ленин и Троцкий его утвердили, доклад о срочной необходимости затопления флота в Новороссийске во избежание захвата его немцами. Автор доклада предлагал больше не обращать внимания на Брестский мирный договор в случае с Черноморским флотом, т.к. Германия его не соблюдает, о чем говорит ее «поход на Керчь». Не очень понятно, почему аналогичным аргументом не являлся захват того же Севастополя или занятие немцами в начале мая 1918 года большой части Азовского побережья (Таганрог, Ейск, а также Ростов-на-Дону), где стояли корабли Азовской флотилии Черноморского флота. Далее, по мнению Беренса, флот следовало затопить, т.к. порт Новороссийска не подходит по своим условиям для содержания Черноморского флота, и суда скоро придут в негодность, и их невозможно будет использовать как боевые единицы (текст доклада с резолюцией Ленина опубликован в 1931 году В.Жуковым)[2]. Этот аргумент, кажется, еще более загадочным – если суда сами по себе скоро придут в негодность, зачем их «срочно» подвергать затоплению. В итоге, Беренс делал вывод, что немцы могут попытаться захватить Новороссийск с суши и тогда им достанется Черноморский флот, который некому будет защитить.

Не отрицая значение патриотически-государственнических мотивов этого текста, легшего, по сути, в основу всей «идеологии» затопления, зафиксированной в дальнейшем и в воспоминаниях моряков, и в научной литературе, стоит отметить еще одно странное обстоятельство. А именно – ту форму, в которой до руководства Черноморским флотом было доведено требование о затоплении флота. Как известно, была послана обычная телеграмма – с указанием вернуть флот в Севастополь. А затем – телеграмма секретная, с требованием не соблюдать текст первой телеграммы, а осуществить затопление.

На запрос и.о. командующего флотом Тихменева, по какой причине приказ является секретным, он получил не слишком логичный ответ: немцы выдвинули ультиматум о возвращении флота в Севастополь, они угрожают напасть на Новороссийск, если флот не вернется до 18 июня 1918 года, поэтому затопление флота должно быть осуществлено тайно. Итак, во избежание захвата Новороссийска немцами флот требовалось вернуть в Севастополь, однако центральная власть, заявлявшая, что главное – снять угрозу немецкой оккупации Новороссийска, требовала этот ультиматум проигнорировать. Очевидно, если бы Тихменев выполнил указание большевиков, то корабли в Севастопольской бухте появиться не смогли бы.

Однако Тихменев, как известно, проведя голосование на флоте – как следует поступить с кораблями, затопить или вернуть в Севастополь, – и не получив однозначных результатов, принял решение выполнить указание того текста телеграммы, который был открытым. Отсюда можно сделать парадоксальный вывод, что именно решение Тихменева о возвращении флота в Севастополь спасло большевиков от нападения немцев на Новороссийск, хотя в Севастополь вернулась меньшая часть ушедших кораблей.

Автор этих строк в своей предыдущей статье, посвященной братьям Беренсам, выдвинула предположение, что начальник Морского генштаба Евгений Беренс был разведчиком, причем, возможно, даже двойным, что он контактировал с разведками Британии (что более вероятно) и Германии. И, возможно, о его контактах летом 1918 года были в курсе Ленин и Троцкий, и именно этим объясняется неуязвимость Беренса на своем посту в ходе раскрытия осенью 1918 года британского «заговора послов», когда в Морском генштабе были арестованы многие ближайшие сотрудники Беренса, но не он сам. А в марте 1918 года, как раз в тот момент, когда Беренс, по сути, подменил первоначальную установку морского Наркомата на «вывоз запасов имущества» из Севастополя в Новороссийск требованием эвакуации флота, в Морском генеральном штабе ликвидировались следы сотрудничества с его британскими агентами. В конце мая-начале июня же складывается своего рода триумвират тех, кто требовал скорейшего тайного уничтожения флота – Ленин, Троцкий и Беренс.

В книге 1931 года участника событий, прапорщика В. Жукова «Черноморский флот в революции 1917-1918 гг.», долгие годы лежавшей в спецхране, автор как бы между делом пишет: «_Англичане прекрасно учитывали описанную стратегическую обстановку, и в их интересах было не допустить захвата Черноморского флота немцами, почему их дипломатия пыталась всякими окольными путями, через влиятельные морские круги, оказать воздействие на советское правительство, которое, помимо этого, пришло к выводу о необходимости уничтожить Черноморский флот. По тем же соображениям, хотя и под предлогом борьбы с большевиками, англичане, пришедшие в Крым на смену немцев (август 1918 г.), поспешили уничтожить русские морские силы на Черном море. Так, по постановлению англо-французской Военно-морской комиссии экспертов, были взорваны цилиндры машин и башенные орудия на старых броненосцах, а 11 подводных лодок были выведены в море и утоплены_»[3]. В более поздней советской литературе подобные стратегические расклады вокруг истории с затоплением флота не фигурируют.

Историк спецслужб Александр Колпакиди в разговоре с автором этих строк согласился с предположением, что за идеей затопления флота действительно могли стоять какие-то негласные договоренности руководства большевиков с Англией и Францией, которые вели свою активную игру – или, точнее, попытки большевиков договориться с союзниками по Антанте о сотрудничестве. В частности, по мнению А.Колпакиди, так называемый Красный десант – операция частей Красной Армии под Таганрогом в начале июня 1918 года, совершенно бессмысленная с военной точки зрения (весь десант был просто расстрелян немцами в упор) – вполне могла быть провокацией, с целью надавить на руководство большевиков в каком-то вопросе. Возможно, открытие французских архивов, до сих пор засекреченных, позволило бы дать ответ по данному поводу.

Пока же можно только очень осторожно сказать, что в случае справедливости высказанного предположения предметом англо-французского шантажа вполне мог стать вопрос затопления Черноморского флота – ведь именно после истории с Красным десантом (8 – 14 июня) Ленин и Троцкий начинают «бомбить» телеграммами Новороссийск с требованием срочного затопления (активный обмен телеграммами – с 13 июня).

И если это предположение всё же справедливо, то это, вероятно, могло бы объяснить яростную реакцию большевиков («красный террор») на раскрытие в начале сентября 1918 года заговора британских послов, планировавших свержение советской власти – спустя всего два с половиной месяца после затопления кораблей Черноморского флота.

Бегущие на кораблях

В книге 1931 года В.Жукова, правда, с соответствующими идеологическими коннотациями, подчеркивалось, что именно Черноморский флот как целостность дал жизнь врангелевской эвакуации: «… _флот оказал белым неоценимую услугу при бегстве их и эвакуации из Крыма и помог им увезти на судах награбленное ценное имущество республики, которое, как и сам флот, сделались для них источником питания и существования надолго за границей_»[4].

Однако врангелевский «исход» был не единственной эвакуацией, которую осуществляли корабли Черноморского флота в годы гражданской войны.

Впервые на кораблях бежали как раз красноармейцы – вместе с жителями Севастополя – в апреле 1918 года от наступающих немецких и украинских войск. Тогда в Новороссийск было эвакуировано по различным подсчетам 4,5 – 5 тысяч военнослужащих и 15 тысяч гражданских лиц (при численности жителей города в начале ХХ века около 60 тысяч человек).

Эсминец «Стремительный», поднятый со дна Цемесской бухты в 1926 году

В апреле 1919 года флот сыграл большую роль в спасении людей, убегавших от установления советской власти в Крыму: как пишет Екатерина Алтабаева в книге «Смутное время. Севастополь в 1917 – 1920 гг.», «_транспорты и пароходы с сотнями мирных жителей в трюмах и на палубах буксировали миноносцы «Жаркий», «Живой», «Поспешный», «Пылкий», «Строгий», «Свирепый» и даже подводные лодки «Утка», «Буревестник»_». Именно эти миноносцы остались «живы» годом ранее, т.к. их команды отказались топить свои корабли под Новороссийском и ушли в Севастополь под власть немцев. После окончания Первой мировой войны и ухода немцев из Крыма в ноябре 1918 года там было создано Второе краевое правительство, признавшее власть белого генерала Антона Деникина, и теперь, в апреле 1919-го эти корабли увозили в тот же Новороссийск из «белого» Крыма людей, бежавших от наступавшей Красной Армии.

Что касается упомянутых в цитате подводных лодок, то это была часть того подводного флота, который смог пережить немецкую оккупацию (подводные лодки даже не пробовали сбежать в Новороссийск в апреле 1918 года от наступающих немецких войск), однако не смог пережить «союзников». После оставления белыми в апреле 1919 года Крыма и Севастополя, отмечает Е. Алтабаева, «_Те суда, которые остались в Севастополе (в основном это были довольно старые линейные корабли), оккупационные власти Антанты не собирались отдавать красным. На крейсере «Память Меркурия», миноносцах «Быстром», «Жутком», «Заветном», транспорте «Березань» подрывные команды взорвали ходовые механизмы. А одиннадцать подводных лодок вывели на внешний рейд и затопили на большой глубине. Французские интервенты привели в негодность орудия береговых батарей, самолеты базы гидроавиации_».

Прошло чуть менее года, и снова оставшиеся в живых корабли Черноморского флота увозили тех, кто смог пробраться на корабли, убегая от наступающей Красной Армии. На этот раз – из Новороссийска в Севастополь и Феодосию, на март 1920 года за «белыми» оставался только Крым, отвоеванный Деникиным у «красных» в июне 1919 года. Тогда, после поражения правительства Деникина, уехавшего в эмиграцию, корабли эвакуировали из Новороссийска чуть более 30 тысяч человек. Правда, в той эвакуации принимали участие не только корабли Черноморского флота, но и суда союзников (Британии, Франции, США, Италии), однако важно не столько это, сколько то, что эвакуация по причине своей абсолютной неорганизованности получила название «Новороссийской катастрофы». Екатерина Алтабаева приводит слова современников событий: «_На пристани творилось что-то ужасное: многие, потерявшие надежду выехать из Новороссийска, бросались в море, иные стрелялись, другие истерично плакали, протягивая в сторону уходящих транспортов руки_».

Этот катастрофический опыт деникинской эвакуации был учтен правительством Врангеля, последним «белым» правительством в Крыму и Севастополе. План эвакуации на кораблях был составлен практически сразу же после «новороссийской катастрофы», в апреле 1920 года, учитывалось расчетное количество посадочных мест, места дислокации кораблей – чтобы они не концентрировались в одном Севастополе, а при необходимости могли вывести людей и из прибрежных городов Крыма, начался ремонт кораблей, чтобы они смогли выдержать длительный переход в море, и т.п. В итоге, спустя полгода, в ноябре того же 1920 года, из Севастополя – на этот раз не в Новороссийск, а в чужую землю, Константинополь – корабли Черноморского флота эвакуировали 145 тысяч человек, из которых только порядка 5 тысяч были военнослужащими.

Именно такого спасения оказались лишены в годы Великой Отечественной войны, как известно, защитники Севастополя. Они, находясь под землей, на 35-й батарее, последнем рубеже обороны города, в июле 1942 года ждали – и не дождались – кораблей Черноморского флота, которые увезли бы их от немцев.

Кроме того, история раскола флота в июне 1918 года – это история корабельного патриотизма, как бы банально это ни звучало. И понимался этот патриотизм каждым по-своему. Вообще история Черноморского флота периода гражданской войны – не только о боевых действиях, но и о свойственной черноморцам корабельной субъектности. Понятно, что для многих моряков почти во все времена корабль – это своего рода дом. И не случайно, судьбы отдельных кораблей и флота в целом весной – летом 1918 года решались самими командами.

Низовая демократия, которой в нашей стране нет до сих пор, в тех критических условиях проявила себя как положительный феномен в таком, казалось бы, по природе недемократическом институте, каким является флот. По каждому вопросу – выбор командующего, эвакуация в Новороссийск, затопление кораблей или возвращение в Севастополь – на флоте проводилось голосование, и в зависимости от его исхода принималось решение. И вся история кораблей Черноморского флота в целом – пример трагического выбора в ситуации, когда две взаимоисключающих позиции в равной мере являются верными, а герои есть с обеих сторон.

Автор статьи выражает благодарность за консультации Д.Ю. Козлову, А.И. Колпакиди, О.Р. Айрапетову, А.В. Ганину.

[1] Жуков В.К. Черноморский флот в революции 1917-1918 гг. М., 1931. С. 217.

[2] Там же. С. 246 – 248.

[3] Там же. С. 295.

[4] Там же. С. 302.

______

Наш проект осуществляется на общественных началах и нуждается в помощи наших читателей. Будем благодарны за помощь проекту:

Номер банковской карты – 4817760155791159 (Сбербанк)

Реквизиты банковской карты:

— счет 40817810540012455516

— БИК 044525225

Счет для перевода по системе Paypal — russkayaidea@gmail.com

Яндекс-кошелек — 410015350990956

Кандидат исторических наук. Преподаватель МГУ им. М.В. Ломоносова. Главный редактор сайта Русская Idea

Комментарии к архивным материалам закрыты. Однако Вы можете высказывать свое мнение в нашем Телеграм-канале, а также в сообществе Русская Истина в ВК. Добро пожаловать!

Также Вы можете присылать нам свое развернутое мнение в виде статьи или поста в блоге.

Чувствуете в себе силы, мысль бьет ключом? Становитесь нашим автором!

а также…

Свежие записи:

Поделитесь нашими материалами в своих соцсетях!

сайт консервативной политической мысли

открытая дискуссионная площадка

Manuscript submission criteria

Manuscripts and articles will be reviewed by the Editorial Board only if all the requirements listed below are met.

- The Editorial Board will consider articles that occupy 0.5 to 1.5 pages [a page is 40,000 typographical units]. They must present the results of an independent and original research, which is in line with the profile of the almanac and demonstrates the author’s ability to be fully conversant with the modern literature addressing the problems in question and to adequately apply the commonly used methodology for defining and solving scientific matters.

Besides, the Site for Russian Verity also publishes analytical synopsis of modern works (size – about 1 sheet), as well as reviews of recent scientific works (size – 0.25 sheet).

All texts must contain only literary language and must be duly edited following the scientific style standards. - If the manuscript is accepted for consideration, it does not imply that it will be published. All manuscripts are sent anonymously for expert review. The names of the reviewers (usually at least two) are not disclosed. If the submitted manuscript is rejected, the editors send a reply to the author clarifying the reasons.

The only relevant criterion for publishing the manuscript is the quality of the text and consistence with the scope of the almanac. - Please avoid automatic bulleted and numbered lists and word breaks. rtf is the preferable format. Only «» can be used as quotation marks. If a quote includes citations, use quotation marks in quotation marks, «“one”, two, three, “four”». Hyphens should not be used as dashes. The Russian letter ё is used only in cases when the replacement for e distorts the meaning of the word. The shortened forms mln and bln are used without the full stop. Abbreviations like “т.к.”, “т.н.” are not allowed. The figure in the footnotes is used in the end of a sentence before the full stop and in a sentence before any punctuation mark (comma, period, and semicolon). Illustrations are sent separately in jpg-files. Graphs and charts are made in separate Microsoft Excel files. The text should contain the indication of the location of this illustration, graphics, charts, and / or its image.

- The editors can edit and cut materials.

Those who submit manuscripts are kindly asked to understand the fact that the editors do not enter into any correspondence, particularly they do not engage in a meaningful debate via e-mail or mail, and do not have any obligation concerning the publication of the submitted materials. - The cover must contain the name, first name and patronymic of the author, the academic degree and academic rank, the position and place of work, the address and zip code and the email address of the author and must be stored in a separate file.

The information is to be written both in Russian and in English. The main file of the article must contain the name, the text itself, footnotes and endnotes bibliography. This is done to meet the requirement of an anonymous review of manuscripts sent to the editorial board. - The author must provide a list of keywords, a summary of the work (abstract) in English and in Russian (size – 100-200 words). The abstract is a separate analytical text, which allows to fully grasp the essence of the study, without the need for the reader to refer to the article. The summary (abstract) must be written in correct academic English. It must not be a word-for-word translation and cannot contain unintelligible structures and idioms which sound Russian.

- Links and references:

- Links to scientific and philosophical literature, analytical reports and articles in scientific journals should be presented in the form of intrabibliographic references containing the number of publications in the bibliography and pages.

For example:

[26, p. 237]. - Links to archived documents must be included in the footnotes indicating (describing) the nature of the document.

For example:

For biographies of K.N. Leontiev [From a letter from K.N. Leontiev to Vs.S. Solovyov, January 15, 1877, Moscow] // Russian State Historical Archives. F. 1120. Op. 1. D. 98. L. 54 ob.-55. - Links to information, official and other sources, including Internet resources that are not scientific or analytical materials, must be given in footnotes.

For example:

The National Security Strategy of the Russian Federation until 2020. The Security Council of the Russian Federation. URL: http //www.scrf.gov.ru /documents/99.html

Solovyov O. The central bank is preparing a new devaluation // Nezavisimaya Gazeta. January 13, 2015. - The footnotes can contain any additional ideas; footnotes can contain links, presented in the same way as in the main text. When referring to Internet publications, there is no need to indicate the access date.

- The bibliography in endnotes is compiled in the alphabetical principle (first list the authors and the works in Russian, then in Latin). The last name and initials of the author must be in italics. The references to monographs must indicate the total number of pages, and references to articles must indicate the page numbers in a journal or a collection where the article is printed.

For example:

Berdyaev N.A. Philosophy of Inequality / Compiled, foreword and notes L.V. Polyakov. M: IMA-Press, 1990. 285 p.

Gajda F. Bloody Sunday as a very ambitious provocation of the opposition // Website on conservative political thought “Russian idea”. January 5, 2015. URL: http://politconservatism.ru/forecasts/krovavoe-voskresene-kak-grandioznaya-provokatsiya-oppozitsii/

Shirinyants A.A .The Intellectuals in the Political History of the XIX Century // Bulletin of Moscow University. Edition 12. Political sciences. 2012. № 4. pp. 39-55.

Nye J. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: Public Affairs, 2004. 208 p. - The endnotes reference list must specify the official place of publication and publisher (sometimes the search may require extra efforts, but the names must be presented).

- The translation of Russian names in English or their Latin transliteration are not required, nor is it necessary to translate foreign titles into Russian (except publications in Oriental languages).

Reviewing rules for submitted manuscripts

- The Site for Russian Verity guarantees the transparency of the publication policy and criteria for manuscripts. Editors select reviewers in such a way to minimize the likelihood of a clash of interest and avert prejudice to the manuscripts submitted. The reviews of the manuscript are taken into account to decide whether to publish it or suggest further work on it. The final decision is taken by the Editorial Board.

- The cover must contain the name, first name and patronymic of the author, the academic degree and academic rank, the position and place of work, the address and zip code and the email address of the author and must be stored in a separate file. The information must be provided both in Russian and in English.

- Manuscripts, submitted to the journal, are assessed in accordance with the double-blind peer-review procedure. For this purpose the manuscripts are sent to the external experts without any identification of authorship, neither the name nor the place of work. Similarly, the journal does not disclose the names or positions of reviewers to the authors or third parties in accordance with international standards of peer-reviewing in academic journals.

- The journal invites recognized experts in the relevant field, who have had their works on the relevant issues published over 3 years. The manuscript is reviewed by the Editorial Board, as well the experts. The Editorial Board Chairman and Editor-in-Chief select external experts and invite them to review the manuscript. The reviews are kept by the editors for 5 years.

- A submitted manuscript is initially assessed by the editors in order to confirm that it corresponds to the scope and standards of the journal. Then, the editors delete any references to the author and code the manuscript. The coded manuscript is submitted to the reviewer.

- The coded manuscript is sent to the external experts along with the standardized questionnaire via e-mail. In the covering letter the editors set the deadline for the review (each case is considered separately, but the time allotted cannot exceed 1 month).

- On receiving the results of the external assessment, the editors examine the review to see if it meets the existing criteria. If the review does not give an adequate evaluation of the manuscript, the editors could seek additional review by other experts.

- If the review contains suggestions for improving the manuscript, it is forwarded to the author. Before sending it, the editors delete comments which are meant for the editors exclusively as well as any offensive or insulting comments.

- The deadline for resubmitting the manuscript is set each time individually. If the manuscript is rewritten significantly before resubmission (no less than 15% of the text), it could be sent for additional reviewing. While choosing experts for the additional reviewing, preference will be given to the same experts who did the initial review (given that they agree).

- The editors send copies of the reviews or a refusal with the reasons to the authors of the submitted articles. They also commit themselves to sending copies of the reviews to the Russian Ministry of Education and Science should the following request be made.

- Reviewing is conducted on the basis of the standardized questionnaire:

The importance of the issues to the academic tasks set of RV:

1 = minimal contribution

2 = minor contribution

3 = moderate contribution

4 = significant contribution

5 = substantial contribution to the discipline

The relevance of the research for philosophy, political science and historical science nowadays:

1 = almost irrelevant

2 = minor relevance

3 = moderate relevance

4 = significant relevance

5 = substantial contribution to the discipline

Author’s originality (autonomy) in addressing the issue:

1 = low (trivial, unoriginal, “common place”);

2 = below average (there are some original thoughts);

3 = moderate;

4 = sufficient;

5 = original research, containing a new approach to issue;

The credibility of the hypothesis, coherence and logical reasoning:

1 = not convincing;

2 = not very convincing (many contradictions);

3 = average level of credibility (standard, traditional proofs);

4 = quite convincing arguments (in general, sound persuasive, with few exceptions);

5 = very persuasive arguments

The reliability of data:

1 = unreliable;

2 = limited reliability (accuracy of the information causes significant doubt)

3 = partly reliable (not differentiated);

4 = quite reliable (sufficient data without sufficient critical thinking);

5 = fully reliable (complete, adequate and critically processed data)

Appropriate style, accuracy and precision, brevity:

1. Low (grammatical and stylistic errors, lacking terminological precision, multiple repetitions);

2. Below average (repetitions, no precision)

3. Average

4. Above average (some minor flaws);

5. High.

Kirill Benediktov

Russia–France: Possible Conservative Alliance? (№ 3, 2015)

The article studies the possible Russian-French alliance retrospectively and analyses its fundamental features. The main assumption is that France is one of the two Western European countries that could build a strategic alliance with Russia, with Germany being the other one. Starting from it, the author shows that only shared values could provide a solid foundation for an effective alliance. Otherwise the alliance between Russia and the leading European country would be at best tactical, rather than strategic. While there are few, if any, shared values with Germany following the forced transformation of the German cultural code in the wake of the WWII, relations with France have evolved differently. With conservative values shared by most Russians and Frenchmen, the ideological proximity brings the two countries closer. Nowadays some French politicians regard Russia as a guardian and a stronghold of traditional European values that have fallen prey to globalization and are ousted by the aggressive Anglo-Saxon civilization and its model. The sympathizers include intellectuals that form the political agenda and shape public opinion. Others are political activists, mobilizing the electorate. Marine Le Pen, the president of the French National Front, is the most favorably disposed towards Russia among European politicians. The examples of the National Front and its leader reveal the attitude of French conservatives towards Russia. As seen from France, Russia is returning to its roots, so French conservatives regard the resurgence of the Russian Orthodox Church, the formal LGBT propaganda ban and other events as the signs of a titanic battle between the living European Christian tradition endorsed by both France and Russia and the post-Christian and anti-Christian world based on the Anglo-Saxon globalization concept. They also interpret them as signals for possible ideological rapprochement.

Keywords: France, Russia, Alliance, Values, Conservatism, National Front, Marine Le Pen.

Paul Grenier

Russian Conservatism and its Reception the West through the Prism of Ideological Liberalism (№ 3, 2015)

The author focuses attention, first, on the poor reception in the West of Russia’s current attempt to define its national idea by reference to its own pre-communist philosophical tradition. He demonstrates that this negative reception, however, is conditioned by what may, optimistically, be temporary political-ideological exigencies, at a period when very little that is associated with the Russian leadership is able to get a fair or warm reception in mainstream U.S. publications. The author points out that the Russian religious philosophical tradition was widely considered admirable and constructive in the West prior to 2014. At present, however, the typical approach in the U.S. and European press is to contrast Russian realpolitik policies with abstract Western ideals rather than Western realpolitik policies. Meanwhile, the very existence of legitimate Russian ideals is dismissed. The author then turns his attention to Russia’s present efforts to define its own ideals in a conservative vein. He suggests that this effort demands a careful definition of categories and to this end distinguishes between ideological and non-ideological brands of both conservatism and liberalism. He urges Russia’s intellectual leadership to embrace the whole of its tradition (i.e. the best of its tradition) rather than only a part. He notes a tendency by Russian conservatism to privilege what in Plato’s Republic were the virtues of the Guardians (as opposed to the Traders). But the Russian heritage incorporates, according to the author, both liberal and conservative elements, even as it is ultimately grounded in а realm that lies beyond liberalism and conservatism.

Keywords: International Relations, Realism, Barack Obama, Demagogy, Liberalism, Conservatism, Ideology, Russian national idea, N. Berdyaev, G. Fedotov, V. Solovyov, I. Ilyin, Pierre Manent, Jane Jacobs, Plato’s Republic.

Mikhail Ilyin

A Diaologue about Islands and Straits, Intermarums and Intermunds (№ 1, 2015)

Mikhail Ilyin reviews main subjects of scholarly debate between himself and Vadim Tzimburski since early 90s when they both were promoting geopolitical and chronopolitical studies in new Russia. The debate focused on five major issues: character of geopolitics, links between geopolitics and chronopolitics, geopolitics of Russia (Eurasia), limitrophe areas around Russia and particularly Balto-Pontida. Very clear and coherent differences between both analysts would not undermine their essential agreement on basis issues and would not prevent their co-authorship. Furthermore, disagreements were complementary. Even now they continue to inspire further investigations.

Keywords: geopolitics, chronopolitics, Russia-Eurasia, Island of Russia, Heartland, limitrophe areas, Balto-Pontida, Balto-Pontic system.

Leonid Ionin

Projects of Total Democracy: Power of Referendums, E-Democracy, “One Man – One Vote” (№ 3, 2015)

This work regards total democracy as a commitment to solving problems and dealing with contradictions in modern representative democracies through maximizing equality and granting the public with direct access to the mechanisms of social control. The paper considers the proposals to create a “community” run by referendums, to establish online democracy, and to improve the egalitarian principle of “one man – one vote”. It also analyses the sociological and epistemological basis of these models. It draws a conclusion that the conservative approach is more promising, that is the use of the mechanisms elaborated at the earlier, relatively distant stages of political development, the use of mechanisms which take into account diverse particular features of the political process.

Keywords: Public Opinion, Referendum, Scientific Knowledge, Common Knowledge, Qualifications, Classes, Universalism, Particularism.

Andrey Ivanov

The Slogan “Russia for Russians” in Conservative Thought in the Second Half of the XIX Century (№ 4, 2015)

The article studies the origin of the slogan “Russia for Russians” and its conservative interpretations in the second half of the XIX century. The study is based on numerous works, most of which have never been previously used. The author analyzes the attitude to the slogan “Russia for Russians” of well-known conservatives, such as Emperor Alexander III, V. Skaryatin, I. Aksakov, M. Katkov, M. Skobelev, S. Syromyatnikov, V. Rozanov, A. Suvorin and others.

Keywords: “Russia for Russians”, Russian Conservatism, Russian Nationalism, Pan-Slavism, Emperor Alexander III.

Alexei Kharin

The First Book about the Great Geopolitician (№ 1, 2015)

The article is devoted to the intellectual biography V.L. Tsymbursky, written by a political scientist B.V. Mezhuev. In the monograph, Mezhuev succeeded to show basic landmarks of work and the main ideas of the thinker, as well as to determine the value of Tsymbursky’s works. Separate positions cause a discussion, but on the whole the book turned out well.

Keywords: B.V. Mezhuev, V.L. Tsymbursky, “the Island of Russia”, Great Limitrophe, geopolitics, chronopolitics, civilization.

Stanislav Khatuntsev

Vadim Tsymbursky, a Russian Geopolitician (№ 1, 2015)

The article covers geopolitical conceptualization of a prominent Russian philologist, cultural philosopher, thinker, and political writer V.L. Tsymbursky, in particular, his “Island Russia” model, the concepts of “Euronapping” and of the Great Limitroph; as well as their criticism, the author’s opinion of some problems brought up by Tsymbursky. The category of limitrophic spaces is supplemented with the category of limbic territories.

Keywords: V.L. Tsymbursky, “Island Russia”, geopolitics, civilization approach, civilization geopolitics, internal geopolitics of Russia, “Euronapping”, Great Limitrophe, limb, transfer of the capital city.

Stanislav Khatuntsev

“Preserving the Future”: Konstantin Leontiev’s Seven Geopolitical Pillars (№ 4, 2015)

This article analyses the issues related to the “seven pillars” approach, K. Leontiev’s set of ideas about the new «Eastern Slavic culture», and his geopolitical ideas.

Keywords: Heptastylism (Seven Pillars), Anatolism, K. Leontiev, Geopolitics, “Eastern Question”, Constantinople, “Eastern Union”, Russian History, Russian Post-Reform Political Thinking, Historiosophy.

Aleksey Kozhevnikov

Russia’s Present and Future in A. Solzhenitsyn’s and I. Shafarevich’s Works: “From Under the Rubble” Collection (1974) (№ 4, 2015)

The article analyzes A. Solzhenitsyn’s and I. Shafarevich’s political essays. Solzhenitsyn’s and Shafarevich’s articles, published in the “From Under the Rubble” collection, dwelt on the historical problems and development of the Russian nation.

Keywords: A. Solzhenitsyn, I. Shafarevich, “From Under the Rubble” Collection, Russian National Values, Historical Problems of the Russian Nation, Development of the Russian Nation.

Yegor Kholmogorov

Searching for Lost Tsargrad: Tsymbursky and Danilevsky (№ 1, 2015)

The article analyzes how Nikolay Danilevsky’s geopolitical ideas influenced Vadim Tsymbursky, and reveals the similarities and differences in the approaches of both thinkers to Russia’s internal and external geopolitics. Their ideas critically underline vulnerable points of each other’s concepts. Разбираются Danilevsky’s nationalism, pan-Slavism and the programme of the struggle for Constantinople are observed, as well as Tsymbursky’s ideas of «Island Russia», limitrophe zone, internal colonization, and his attention to the region of Novorossia. The author comes to a conclusion that the key problems stated by Danilevsky and Tsymbursky don’t have a solely geopolitical solution and demand the transition to chronopolitics, the consideration of civilizations not only as geographical, but also as historical and cultural integrals.

Keywords: Danilevsky; Tsymbursky; geopolitics; Constantinople; pan-Slavism; nationalism; “Island Russia”; civilization; limitrophe; Siberia; internal colonization; Novorossia; Konstantin Leontiev; chronopolitics; Byzantium.

Olga Malinova

The Conservatives and Collective Memory: Cultivating a Repertoire of Politically Usable Past (№ 3, 2014)

The paper analyses a development of “infrastructure” of a usable past in post-Soviet Russia. It argues that the latter is both a resource and a matter of symbolic investments for the ruling elite. It concludes that after more than 20 years after the collapse of the USSR the repertoire of the usable past remains rather scarce, and “memory policy” is still far from being consistent. The paper supposes that more systematic development of the repertoire of the usable past could be a matter of efforts of the conservatives as well as the other political forces who must be interested in development of this resource that might be considered as fundamental common good.

Keywords: political uses of the past, collective memory, symbolic politics, B. Yeltsin, V. Putin.

Boris Makarenko

Never the Twain Shall Meet? Conservatism in Russia and in the West (№ 3, 2015)

The article compares and contrasts the main values and political principles of contemporary Western and Russian conservatism. The key assumption is that in the West conservatism relies on the uninterrupted tradition of political participation, while Russian conservatism is reinventing its values and political practices, relying on the philosophical and political heritage of the past ages. In the West, conservatism exists in democracies and market economies, while in Russia, conservatism develops in a society in transition, undergoing rapid and uneven modernization. The “strong state” for the West lies in democratic sovereignty, a competitive and efficient economy, and an optimized “welfare state”. Russian conservatism lacks a comprehensive economic doctrine; the value of sovereignty is believed to lie in the defense of internal and external security, and the “welfare state” is largely paternalistic. In the West, conservatism fosters moral and cultural values of the post-industrial age; in Russia these values retain their traditional character, but modernization necessitates their adaptation to the changing society. While, amid the emergence of new conservative ideas, Western conservatism faces the major challenge of developing a “new synthesis”; Russian conservatism needs to respond to the challenge of developing a comprehensive system of values in conformity with the contemporary stage of Russia’s political development.

Keywords: Conservatism, Values, Comparative Politics, Political Development, Political Parties.

Mikhail Maslin

Classic Eurasianism and Its Modern Transformations (№ 4, 2015)

The article reveals the essence of classical Eurasianism in the 1920-1930s. The author makes a general critical evaluation of A. Dugin’s neoeurasianism. Neoeurasianism distorts classical Eurasianism, presenting the image full of xenophobia, racism and aggression. Meanwhile, the author demonstrates the intellectual potential of undistorted classical Eurasianism taking the example of A. Panarin’s heritage.

Keywords: Eurasianism, Neourasianism, Orientalism, Geopolitics, Russian Emigration, Atlantism, Russophobia, Mysticism, Conspirology.

Oleg Matveychev

“The Philosophy of Inequality” by N. Berdyaev – the Manifesto of Liberal Conservatism (№ 3, 2015)

The report describes the concept of the ideological mix. Analyzing “The Philosophy of Inequality”, the author illustrates that N. Berdyaev voices purely liberal-conservative ideas in it. This fact accounts for valid interpretation and popularity of the book in Western Europe in the 1920s and 1930s.

Keywords: “The Philosophy of Inequality” by N. Berdyaev, Ideological Mixes, Liberal Conservatism.

Boris Mezhuyev

Mapping of Russian Europeanism (№ 1, 2015)

This article deals with the evolution of geopolitical views of Vadim Tsymburski in the context of his conceptualization of the problem of “buffer”, or “limitroрhe” territories between Russia and Europe which were called by the author of “The Island of Russia” as “straitterritories”. It is known that Vadim Tsymburski thought that the loss of control by Russia over these territories has strengthened the security of our country that was damaged throughout the history by Russia’s own urge to eliminate these «buffer» territories for the geopolitical confluence of Russia and Europe. The question arises, how could Vadim Tsymbursky treat the elimination of “strait territories” by Europe in terms of his system, could it be seen by him as a threat to Russian security? The article proves that in the end of his life just this point motivated the scholar to reconsider his geopolitical conception but this reconsideration was prevented by his death.

Keywords: geopolitics, strait-territories, buffer territories, Russian Europeanism.

Andrei Nikiforov

The Crimean Contribution to the Revolutionary Restoration of Geopolitical Justice and the New Mission of Russia (№ 3, 2015)

The “Crimean Spring” was a manifestation of the expanding regionalization, that the world has been witnessing in recent years. An integral region becomes the actor of world politics. The region relies on the collective political will of the regional community rather than on separate nation-states with their borders established by treaties of by force. The Crimean issue has provoked sharp divisions in European society, virtually splitting it in two parts: a group of regionalists, advocates of traditional values and a group of neo-liberals and all those who scrounge off globalization. The “Crimean Spring” marked the beginning of the revolutionary restoration of geopolitical justice.

Keywords: “Crimean Spring”, Regionalism, Traditional Values.

Tatyana Plyashchenko

Conservative Liberalism in Russia the Post-reform Period: The History of a Failure (№ 4, 2015)

The article dwells on the peculiarities of Russian conservative liberalism in the second half of the 19th century and its proponents, including A. Gradovsky, K. Kavelin, and B. Chicherin. The article gives special prominence to the policies of the Russian conservative liberals at both theoretical and operative level.

Keywords: Conservative Liberalism, Liberal Nationalism, Nation-State.

Leonid Polyakov

The Eternal and Momentary in Russian Conservatism (№ 4, 2015)

The article pinpoints the plurality of meanings of the terms “conservatism” and “conservatives” which were in use in the Russian philosophical and political thought in second half of the XIX – early XX centuries, and gives a critical evaluation. The study starts with Nikolai Berdyaev’s definition of “conservatism” which poses the key dilemma: either to mercilessly criticize the momentary from the point of view of “eternity”, or to ascribe to the existing momentary a rank of “Eternal”. Through this dilemma it is possible to demonstrate how authentic conservative principles and meanings could have been presented in different and alternative ideological paradigms. The everlasting character of this dilemma in the pre-revolutionary Russian conservative thought for a long time deprived of a possibility for political representation, brought about a fatal gap between conservatism “from above” and radical-left mood “from below”. The ultimate outcome was the collapse of the Empire. The contemporary situation in Russia allows to escape such a scenario through assuming conservative principles as “spiritual bonds” tying authorities and the people.

Keywords: Conservatism, Liberalism, Progressivism, Reactionary, Revolution.

Alexei Rutkevich

Peculiarities of Russian Conservatism. Map and Territory (№ 4, 2015)

Russian conservatism makes part of European political thought, as well as Russian party practices in Russia in the XIX century. The article consistently analyzes the stages of development of conservative ideology in Western Europe and in Russia.

Keywords: Ideology, Baroque, Romanticism, Conservatism, Reaction, Liberal Conservatism, Political Philosophy, Map, Territory.

Aleksey Shchavelev

The Islander or Thinking about “Conjunctures of Land and Time…” (№ 1, 2015)

The paper is a survey commentary on the last book by V.L. Tsymburskiy “Conjunctures of Land and Time”.

Keywords: V.L. Tsymburskiy, review, philosophy of history, historiography.

Alexander Shchipkov

Russian Identity and Russian Tradition at the End of the Globalization Era (№ 3, 2015)

The report dwells on a new demand for tradition and identity, which emerges as globalization exhausts itself. The keynote of Russian identity is claimed to be religious and ethical, rather than ethnic. Irredentism – the reunification of the largest divided nation (Russian) – should be viewed as a key element of Russian identity. It should be distinguished from russification of other ethnic groups by force. To cite Weber’s famous formula, the core of Russian identity is formed by “Orthodox ethics and solidarity spirit, that is equity, partnership and mutual assistance. This is a particular Russian ethos. In practice, justice plays the role of the categorical imperative in the Russian tradition. The author believes that meaningful socio-cultural ideas can be centred round Christian ethics. This factor, along with the Russian language, allows to make the “Russian World” concept more precise from the semantic point of view, as this notion still needs to be fully defined.

Keywords: Identity, Orthodox Ethics, Globalization Limits, Russian World, Solidarity, Justice, Tradition, Ethos

Aleksandr Shiriniants

Conservatism and the Party System in Modern Russia (№ 3, 2014)

The programs of Russian modern political parties, proclaiming conservative aims are analysed in the article through the patterns of phenomenology and axiology of Russian conservatism. The problem of the role of conservatism in contemporary ideological quest in Russia is discussed; original definitions of conservatism and its basis are proposed; links between conservatism and tradition and theoretical reflection are described; specific features of Russian political conservatism and the sources of its heterogeneity are revealed; accent is put on the role played by Russian intelligentsia in formation of conservative ideology; “oppositional” and “progressive” character of conservatism is marked down; comparison of conservative declarations with conservative values is developed.

Keywords: conservative ideology, conservative values, political parties, party-building in modern Russia.

Konstantin Simonov

Conservatism Facing Uncertainty (№ 3, 2015)

European values and the centuries-old picture of the world are exposed to erosion and are undergoing transformation. This is manifested, in particular, in neglecting the obvious benefits of trade and economic relations with Russia, in undermining free competition through affirmative activities, which involve, among other things, the policy of gender and juvenile equality. Such changes make the prediction of the future impossible.

Keywords: Values, Europe, Future Forecasts.

Alexander Tsipko

Soviet Intellectual Community Converting to Russian Conservatism (On Spontaneous Anti-Communism Untying USSR Ideological Bonds) (№ 4, 2015)

The article identifies the interdependence of conservatism, including its Russian version, and anti-communism. It focuses on the ideology of the “Russian Party”, a departure in Soviet political thinking in the 1960s-1970s. The article contains its comparative analysis with the ideology and policies of “Polish Party”, the Polish intellectual community of the 1970s-1980s leading the “Solidarity” movement. It also highlights the differences between the “Russian party” and the Sixtiers.

Keywords: Soviet Political Thinking, “Russian Party”, Conservatism, Anti-Communism, The Sixtiers, “Polish Party”.

Andrei P. Tsygankov

«Island» Geopolitics of Vadim Tsymbursky (№ 1, 2015)

The article analyzes the role of V. Tsymbursky in rethinking geopolitics. In particular, his theory of Russia as a geopolitical “island” is discussed. Other discussed issues include the geopolitics of values, intellectual influences, and Tsymbursky’s position in Russian foreign policy debates. The article formulates two lessons of the thinker for Russia – the need in mastering Russian cultural space and a long period of flexible foreign policy under the conditions of uni-multipolar world.

Keywords: geopolitical “island”, the geopolitics of values, the uni-multipolar world.

Andrei Tsygankov

«Island» Geopolitics of Vadim Tsymbursky (№ 1, 2015)

The article analyzes the role of V. Tsymbursky in rethinking geopolitics. In particular, his theory of Russia as a geopolitical “island” is discussed. Other discussed issues include the geopolitics of values, intellectual influences, and Tsymbursky’s position in Russian foreign policy debates. The article formulates two lessons of the thinker for Russia – the need in mastering Russian cultural space and a long period of flexible foreign policy under the conditions of uni-multipolar world.

Keywords: geopolitical “island”, the geopolitics of values, the uni-multipolar world.

Vadim Tsymbursky (1957 – 2009)

Morphology of Russian Geopolitcs. An excerpt from the book. Chapter Five. First Eurasian Epoch of Russia: from Sebastopol to Port-Arthur (№ 1, 2015)

Vadim Tsymbursky made his PhD thesis «The Morphology of Russian Geopolitics and the Dynamic of International Systems of XVIII–XX centuries» in about 1997-2003. He could not complete his work but he left some fragments of it in manuscript. In the fifth chapter of thesis entitled «The first Eurasian interlude: from Sebastopol to Port-Arthur» the scholar made the analysis of the geopolitical thought of this period of time which was periodically repeated in the Russian history. This period is characterized by temporary backwash after the Russian onslaught on Europe and concentration on the eastern borders of Empire. The chapter describes in detail geopolitical views of prominent authors such as Fyodor Dostoevsky, Nikolai Danilevsky, Alexander Hertzen, Rostislav Fadeev etc.

Keywords: Eurasian interlude, Baltic-Black Sea region, European bipolarity, Balkan question.

Vasiliy Vanchugov

From «Island» to «Fortress»: Methaphor as an Instrument of Political Analysis and Practical Politics (№ 1, 2015)

This article is devoted to the representation of ideas, in particular, the use in the field of geopolitics, metaphors, analogies, comparisons, as well as cases of mythologizing ideologies. For this purpose, the author has made a comparison of the various narratives, methods and techniques of modern production of knowledge in the humanities in general, and in politics in particular. Taking the complex of ideas from the book “The Island of Russia”, the author of the article is going to highlight one of his key works in the context of contemporary issues, because, in his opinion, the most topical issue is the “dismantling” of the empire, discussion of which gives us the opportunity to be engaged in designing future.

Keywords: politics, geopolitics, history, philosophy of history, metaphor, formula, hermeneutics, myth, empire, power, governance.

Yan Vaslavsky

Russia and Europe: A New Crossroads (№ 3, 2015)

The article analyses the changing concept of united Europe from the times of Napoleon Bonaparte. The author ponders on two visions of European politics and development promoted by advocates of Napoleon Bonaparte and philosophers who eschewed the Napoleonic imperial model, respectively. Moreover, the article seeks to study the current relations between Europe and Russia given the changing concept of united Europe.

Keywords: France, Napoleon Bonaparte, Pan-European idea, Napoleonic Wars, Russia and Europe, Russian-European Relations.

Anton Zakutin

Modern Conservatism in the UK and in Russia: Possible Convergence Points (№ 3, 2015)

The article compares and contrasts basic conservative notions of modern political discourse in the UK and in Russia. Despite profound differences between the two political cultures, the two conservative brands exhibit a number of possible convergence points. The need to defend genuine traditional values against a background of expanding globalization, can unite advocates of various and diverse conservative trends. This article gives an overview of the most common ideas in parties’ platforms, among think tanks, among conservative thinkers of the states in question.

Keywords: Conservatism, Comparative Politics, Euroscepticism, Toryism.

Lyubov Bibikova

Postmodernism and the Value Crisis of the European Historical Science (№ 3, 2015)

The article analyzes causes and consequences of the shift towards postmodernism in Europe’s historiography against a background of social and political trends in Europe in the late 20th-early 21stcentury. The text focuses on the crisis of values in European studies of history, and, above all, the philosophy of history, which has been driven by postmodernism to eschew classical positivist notions of objectivity and validity as the fundamental values of historical knowledge. Consequently, leading European historical methodologists have arrived at the conclusion that historical science is predominantly aimed at reaching and maintaining public consensus on various political trends. The state of affairs in the 20th century impelled European historians to search for the roots of the European unity.

Keywords: Postmodernism, Philosophy of History, Historical Science of Europe, Historiography, Memory, Microhistory, Linguistic Shift.

Anatoly Chernyaev

Nikolai Berdyaev’s “Theocratic Socialism” (№ 3, 2014)

Basing on the analysis of Nikolai Berdyaev’s works of 1903–1917, the article reconstructs his project of “theocratic socialism”. It demonstrates the similarity between the concept of Berdyaev and the ideology of European religious Reformation, and also discusses the question of the relevance and applicability of Western experience of the Reformation in Russian socio-historical conditions.

Keywords: Reformation, Orthodoxy, theocracy, socialism, revolution, freedom, personality, new religious consciousness, Berdyaev, Merezhkovsky, Kartashov.

Paul Grenier

Russian Conservatism and its Reception the West through the Prism of Ideological Liberalism (№ 3, 2015)