Lou Polli – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

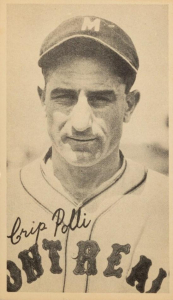

One of the greatest pitchers in minor-league history, lanky righthander Louis “Crip” Polli compiled a minor league lifetime record of 263-226 over 22 seasons. After a late start in professional ball, Polli had the mixed blessing of spending his prime years in the juggernaut New York Yankees organization of the late 1920s and early 1930s. On the one hand, he personally knew immortals such as Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig; on the other, he was held back in the minors when he probably could have been pitching in the big leagues with a less powerful organization.

One of the greatest pitchers in minor-league history, lanky righthander Louis “Crip” Polli compiled a minor league lifetime record of 263-226 over 22 seasons. After a late start in professional ball, Polli had the mixed blessing of spending his prime years in the juggernaut New York Yankees organization of the late 1920s and early 1930s. On the one hand, he personally knew immortals such as Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig; on the other, he was held back in the minors when he probably could have been pitching in the big leagues with a less powerful organization.

Eventually breaking free from the Yankees, Polli joined the St. Louis Browns in 1932, then spent another dozen years in the minors before hooking on with the New York Giants in 1944. Although he never won a game in the big leagues, Crip did pitch three no-hitters at the highest level in the minors, including one in his very last game in organized ball in 1945. When he died in December 2000, he was the oldest living former major-league baseball player.

Many published sources list Polli’s birthplace as Barre, Vermont, but he actually wasn’t born in Vermont. In fact, he wasn’t even born in the United States. The youngest of seven children, Louis Americo Polli was born on July 9, 1901, in Baveno, a little town on Lake Maggiore in the Italian Alps, near Italy’s border with Switzerland. His unusual middle name–which is quite common in Barre for sons of Italian immigrants–hints at the circumstances under which the Pollis came to Barre and the pride they took in their new citizenship.

At the turn of the century, Vermont quarries actively recruited skilled stonecutters from northern Italy, making them one of the few groups whose immigration was aggressively solicited. They were reputedly the best stonecutters in the world, descended from the men whose skills built Rome and supplied raw stone to Michelangelo. Louis’ father, Battista, was one of that breed. He had already emigrated to Barre at the time of Louis’ birth, and the rest of the family joined him when Louis was only seven months old. The Pollis settled in a house at 44 Circle Street, where one of Lou’s nephews lives to this day.

Barre was well-known for its radical politics during the era when Lou was growing up there. Some of the Italian granite workers joined labor unions and became active in the Socialist Party; they were even powerful enough to elect a Socialist mayor. The Pollis, however, were apolitical, and the only connection to the Socialists Lou recalls is attending plays and dances at the Socialist Hall on Granite Street. He remembered adults throwing their coats in a pile on the floor of the Hall and children falling asleep on top of them.

As a child Lou frequently tagged along behind his brothers. By the time he was 13 he was competing in baseball against much older boys. Polli later recalled his first big break: “The team from Barre used to take a wagon to play its games and the kids all used to run behind the wagon all the way to Williamstown,” he recalled. “Then one day the second baseman got sick, so they asked me to play. That meant I got to ride in the wagon on the way back, and didn’t I feel like a big deal.”

Lou attended Barre’s Spaulding High School, but in those days the Spaulding baseball team lacked a coach–for away games Polli was placed in charge and given money to buy dinner for the team. Before long he transferred to a prep school with strong athletic teams, Goddard Seminary, which was located where Barre Auditorium is now. At Goddard Lou suffered a football injury that briefly put him on crutches, and his classmates branded him “Crip,” short for “Cripple.” Even though he fully recovered from the injury, he retained that nickname his entire life, and it was the name by which most people knew him.

Polli lettered in football and basketball at Goddard, but his best sport was baseball. During his senior year he attracted national attention by striking out 28 batters in a ten-inning game against Cushing Academy on June 3, 1921, for which he was featured in Ripley’s Believe It Or Not. During one five-game span that year Crip struck out 105 batters. Letters from colleges poured in, but he hid them from his parents. Crip had no interest in pursuing his education–all he wanted to do was play baseball.

The summer after his graduation from Goddard Lou met Mary Catherine Smith after a baseball game at Gaysley Park in nearby Graniteville. A year later they married. The wedding was controversial by 1922 standards–it may have been the first between members of Barre’s large Scottish and Italian communities –but it lasted nearly 70 years, till death did them part.

Back in 1922 Lou and Mary moved into a small house behind Mary’s parents’ home in Lower Graniteville, only a mile or so from the world-famous Rock of Ages Quarry. For the next several years, as the couple started a family, Lou worked during the week as a rigger in the quarry. He became well-known for climbing 150 feet to the tops of the derricks used to lift the mammoth blocks of granite.

On weekends Polli pitched for the Barre-Montpelier team in the outlaw Green Mountain League in 1923-24, distinguishing himself as the top pitcher of a league that included former major-league stars like Jeff Tesreau and Ray Fisher. Then in 1925-26 he pitched on Saturdays and Sundays in the Boston Twilight League, earning up to $100 a game.

On April 15, 1920, two armed robbers shot and killed the paymaster and an armed guard for a shoe company in South Braintree, Massachusetts, absconding with $15,000. Anarchist Italian immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were convicted of the murders, and the ensuing national clamor over their executions called attention to the radical political views of some Italian-Americans.

Historians have speculated that prejudice might have played a part in causing Lou Polli’s late start in organized baseball. After all, Barre was infamous for its Socialist mayor and its labor struggles in the early years of the century, resulting in the assassination of an anarchist leader. Could Polli have been branded simply by residence?

Asked to speak of this many years later, the 97-year-old Polli thought those theories were nonsense. At the time in question he had a wife and two kids to support, and he said he was able to earn more money working at the quarry and playing semi-pro ball on weekends than he ever could have earned in the minors. Moreover, he actually did play organized baseball, albeit only for a brief time in 1922 (he won three out of four decisions for Montreal of the short-lived Eastern Canada League).

In any event, Crip finally got what he considers to be his real start in organized baseball with Harrisburg of the New York-Penn League in 1927. He had been discovered the previous summer by Ben Houser, his manager with the team from Old Town, Maine, in the Boston Twilight League. Houser was also a part-time scout for the New York Yankees. Impressed by Polli’s diverse repertoire of pitches–he threw a curve, a sinker, a knuckleball and a screwball to go along with a fastball estimated at above 90 mph–Houser recommended Polli to Nashua of the Class-B New England League. Even though Lou was only 1-2 for Nashua, the Yankees signed him after the season ended.

In his first full minor-league season, Polli led the New York-Penn League in wins with 18 and strikeouts with 109 while notching a sparkling 2.25 ERA. In 1928 the Yankees promoted him to the top level of the minors with St. Paul of the American Association, where he was a mediocre 13-15 with a 3.53 ERA. In his second season with St. Paul, Polli’s 22 wins and 288 innings topped the league. Based on that performance, the Yankees invited Polli to his first big-league spring-training camp in 1930.

It was a memorable experience: “There were 26 pitchers trying out for one job,” Polli said. “It came down to me and Lefty Gomez.” A future Hall-of-Famer, Gomez was coming off an 18-11 season with San Francisco in 1929. “He was seven years younger,” Polli continued, “so you knew damn well who would get the job.” Still, Crip retained marvelous memories of his 31-day preseason barnstorming tour with the Bronx Bombers, riding the rails on The Yankee Express and playing exhibition games all over the south.

Those Yankees were arguably the greatest team in baseball history, and Polli got to know many players who wound up in the Hall of Fame. His bridge partner, for example, was none other than Bill Dickey–and his frequent opponents were Lou and Eleanor Gehrig. “I roomed with Tony Lazzeri for a time,” Polli said. “Earle Combs, too. But Lazzeri! He snored so hard that he kept me awake half the night. I’d go over and punch him in the arm to get him to stop. He did, but then he’d start up again and I’d lose more sleep.”

But the teammate Polli was asked about most frequently is, of course, Babe Ruth: “He was full of hell, that guy, but I liked him. He was always nice to me. We’d shoot pool and I played a lot of golf with him. We used to play at those Tom Thumb courses for a quarter a hole. He couldn’t putt worth a damn. I took a lot of quarters from him.”

Polli was assigned to Louisville in 1930 after just missing out on making the Yankees. That was the first summer he brought his family to live with him during the season, and daughter Margaret remembered the culture shock she experienced in Kentucky, as well as the sweltering heat of the Louisville summer and how players and their families gathered in a basement after games and passed around a bucket of ice-cold beer (despite Prohibition) to cool off.

Even though Louisville won the American Association pennant, Polli suffered through a miserable 8-13 season, including a career-worst 5.82 ERA. To make things worse, he was sued after moving out of the first house he lived in that summer and ended up having to pay rent on two houses. Then, to cap off a really horrible year, the Yankees released him.

Perhaps Polli’s release by the Yankees was fortuitous. “Our catcher, Bill Dickey, later told me that the Yankee brass held me back because they didn’t want me pitching for another big-league team,” Crip said. Now he had a chance to catch on with another organization–and he did after rebounding from his poor 1930 season with a 21-15 record for the Milwaukee Brewers in 1931.

Crip’s chance came with the St. Louis Browns. In his major-league debut on April 18, 1932, he pitched one inning of a 14-7 loss to Detroit, giving up a run on two hits and a walk. The next day he pitched again in a mop-up role as the Tigers won 8-0. After those two appearances he pitched sparingly. Remaining with St. Louis for the entire season, Polli appeared in a total of just five games, pitching only seven innings of relief.

Although the Browns were a perennial second-division club–Polli says they had about six real major leaguers and the rest should have been at Double A–they did have one star, Hall-of-Famer Goose Goslin. Polli described the Goose as a “great ball-player and a real nice, friendly man. He would talk to anyone for hours. He was great with the kids, always signing a ball and handing it back to them.” Then there was Bump Hadley, a pitcher who led the AL in walks with 171 and losses with 21: “Not too consistent a pitcher. He’d win a game or two and then lose seven, eight in a row. He said he wondered why they kept him.”

At his own request Polli returned to Milwaukee in 1933, and he and his family spent three more happy years in that baseball-crazy city. His most memorable day in a Brewer uniform came on September 7, 1935. The opposing pitcher that day was Lou Fette, a former teammate of Crip’s at St. Paul who became a 20-game winner as a Boston Braves rookie in 1937. Crip had told Fette that he would throw a no-hitter the next time he pitched against him, and that’s exactly what he did.

While traveling with the Milwaukee team, Crip sometimes roomed with Earl Webb, a Tennessee native who had hit an all-time major-league record 67 doubles for the Boston Red Sox in 1931. “He was a mountaineer from the hills,” Crip said. “He used to spend his time reading magazines of western stories and drinking whiskey. His family used to make their own.” Webb, however, was not the most unusual of Polli’s teammates; Crip claims to have played with one man who never wore shoes. “His feet were so tough that we gave him a hotfoot once and he didn’t even notice,” Polli said.

In 1936-37 Crip played for the Montreal Royals, the team for which he pitched his second no-hitter on July 19, 1937. Living in Montreal was ideal, close enough to Vermont that he could come home on off-days. Sometimes he brought a teammate with him; one visitor was Del Bissonette, the former Dodger. But like his boyhood idol, Ty Cobb, Polli could be tough to handle–and on at least one occasion his temper proved costly:

I had a pretty good year [with the Royals in 1937] and they had promised me a bonus. Then they wouldn’t pay me. So I went to the offices, which were up on the second floor, and argued with those three Frenchmen who ran the team. [One of the “Frenchmen” was Charles Trudeau, father of Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau.] I called them cheap Frenchmen, they said I’d never play for them again and they punished me by sending me to Chattanooga.

Polli spent the next five seasons in the south, bouncing from Chattanooga to Knoxville to Jacksonville. Then in 1944 the 43-year-old led the International League in ERA with a 1.84 mark for Jersey City, earning a second shot at the majors a dozen years after his first.

Used mostly in middle relief, Crip Polli pitched 36 innings in 19 games for the 1944 New York Giants, going 0-2 with a 4.54 ERA. He did rack up three saves, but that figure pale in comparison to teammate Ace Adams‘ NL-leading 13. Crip claims that Adams was the “pet” of player-manager Mel Ott, a Hall-of-Fame outfielder who was not much of a manager–at least not according to Crip.

Ott was so nervous that his spikes chewed up the ground wherever he stood. On one occasion he called in Polli with the bases loaded and nobody out without giving him a chance to warm up. Crip walked in a run, then struck out the side to end the inning–only to be bawled out by Ott for walking in the run. Ironically, the manager also may have cost Crip his best chance at a win that season. It was on May 27, in a game against the Cardinals, the eventual World Champions that year. Ott made a rare appearance at third base and booted a grounder hit by Pepper Martin. The error led to three unearned runs, turning a lead into a defeat charged to Polli.

Crip returned to Jersey City of the International League in 1945. There he ended his long career–with a flourish in a minor key. Polli’s oldest daughter, Mary, had been suffering for two years with tuberculosis, a dark cloud hanging over the family. Before his scheduled last start of the 1945 season, on September 3, the veteran pitcher learned the bad news: Mary’s condition had been diagnosed as terminal.

Many men would have begged off that day, especially as the opponents were the fabled Newark Bears, a Yankee farm club considered by many minor-league historians as one of the most powerful minor-league clubs in history. These Bears were on a rampage, with a 14-game win streak.

Lou Polli, part of his mind numbed with the awful news of his daughter’s fate, asked for the ball. Then he went out and pitched the game of his life. Though 44 years old and a battle-scarred veteran of 22 professional campaigns, Crip set down the Bears inning after inning–without a hit. When it was over he had his third minor-league no-hitter, having faced just 30 batters, three above the minimum. His teammates, perhaps sensing the emotion-laden situation, responded explosively, mauling the Newark club 11-0. The Bears’ 14-game victory streak was over.

Crip’s heroic performance made no difference to the inexorable march of his daughter’s fate. Mary Polli died on November 5, 1945, at the sanatorium in Saranac Lake, New York, where Christy Mathewson had died two decades earlier.

Polli never pitched another game in professional baseball.

Following his daughter Mary’s death, Lou Polli went to Halifax, Nova Scotia, to manage a semi-pro team for the summer of 1946, then returned to Graniteville in 1947 and became the first constable for Barre Town, Vermont, serving until 1970. Over the years he also became Town Agent and Collector of Taxes, and daughter Margaret remembers him staying up late at night computing tax bills in his head–he never used an adding machine. Polli remained in those offices until his retirement at age 80 in 1981, but even in “retirement” he went back to work at a friend’s service station on Washington Street.

After this return to Graniteville Polli managed the Lower Graniteville baseball team for several seasons until about 1950, mostly playing shortstop but occasionally pitching. “Even at that point in his career he was by far the best pitcher I ever saw,” said Russell Ross, one of his teammates. Polli then became involved in the area’s youth baseball programs. One of his favorite stories involved a group of Graniteville Little Leaguers that he managed:

I instructed one youngster, who was seated on the bench, to follow another boy in the batting order. The kid who was up hit a home run, and when he started running around the bases, the second kid trotted behind him. When they got back to the bench I asked the second kid, “What were you doing?” And he said, “You told me to follow him, so I did.” I nearly cracked up over that one, but I managed to hold back my laughter.

Crip excelled at almost everything he attempted, and a trophy-filled room at his house in Graniteville attested his prowess at bowling, golf, billiards and bridge (he was considered one of the best bridge players in Vermont). He also enjoyed fishing at his daughter’s camp on Harvey’s Lake in West Barnet.

Polli still lived in the same old house in Graniteville until 1996, when he moved in with his daughter Margaret in Barre. He was doing well until November 1997, when he slipped in the shower and fractured a hip. He spent his recuperation at Wood-ridge Nursing Home, which is affiliated with Central Vermont Hospital, reading the Burlington Free Press and the Montpelier Times-Argus each day, turning first to the sports pages to find out how his beloved Yankees did.

On December 19, 2000, Crip Polli died at the age of 99. At the time of his death, he was the oldest living ex-major league player.

Sources

A version of this biography originally appeared in Green Mountain Boys of Summer: Vermonters in the Major Leagues 1882-1993, edited by Tom Simon (New England Press, 2000).

In researching this article, the author made use of the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, the Tom Shea Collection, the archives at the University of Vermont, and several local newspapers.