Chuck Estrada – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

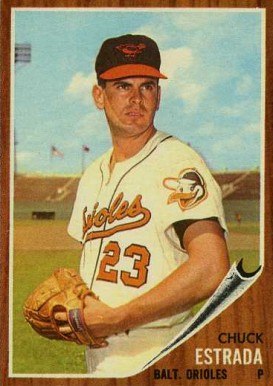

The elder statesman of the Baby Birds staff that vaulted the Baltimore Orioles into pennant contention in the early 1960s was a mere 22-year-old. He is the only AL pitcher to lead the circuit in wins during a rookie campaign and the only one in either league to do so since Chicago Cubs righty Larry Cheney in 1912.1 Though Chuck Estrada’s 18 rookie wins matched such notable hurlers as Babe Ruth and Dizzy Dean, he fell considerably short of the 22 first-place votes garnered by shortstop Ron Hansen in the only instance where teammates finished 1-2-3 in Rookie of the Year balloting.

The elder statesman of the Baby Birds staff that vaulted the Baltimore Orioles into pennant contention in the early 1960s was a mere 22-year-old. He is the only AL pitcher to lead the circuit in wins during a rookie campaign and the only one in either league to do so since Chicago Cubs righty Larry Cheney in 1912.1 Though Chuck Estrada’s 18 rookie wins matched such notable hurlers as Babe Ruth and Dizzy Dean, he fell considerably short of the 22 first-place votes garnered by shortstop Ron Hansen in the only instance where teammates finished 1-2-3 in Rookie of the Year balloting.

Despite a large number of walks and HBP during his debut season (wild pitches would climb in future campaigns), Estrada garnered a respectable 3.58 ERA (league average: 3.87) to join Hansen and rookie teammate Jim Gentile in garnering both an All Star berth and MVP consideration. Orioles manager Paul Richards, who had a knack for developing talented young pitchers, began working with Estrada the following spring to change the righty’s windup. Though there is no evidence that the new windup was a direct cause, Estrada departed spring camp with elbow soreness .2 He collected an additional 15 wins in 1961 to place among the league leaders and establish himself as one of the major leagues’ premier pitchers. But the combined 33 wins over his first two seasons would represent nearly 70 percent of Estrada’s career total when elbow problems brought a rapid end to his major league pursuits.

Charles Leonard Estrada was born on February 15, 1938, the fifth of eight children of John Robert and Catherine M. (Rizzoli) Estrada, in San Margarita, California, roughly midway between San Francisco and Los Angeles along the Central Coast. Of Spanish and Italian extraction (his maternal grandmother arrived in the United States from Italy before the turn of the 20th Century), Chuck’s paternal California roots reached back decades before statehood. His father, a truck driver for San Luis Obispo County, reared the family on the “east [side] of the railroad tracks.” The continuous after-school play of the six Estrada brothers contributed to Chuck’s prowess in football, basketball, and track. But it was baseball where he especially excelled, winning MVP honors during his junior and senior years with the Atascedero High School Greyhounds. Though he did not attract attention from major league scouts, Estrada did garner notice from college recruiters. Following his high school graduation in 1956, he accepted a full athletic scholarship to nearby California Polytechnic State University.

Before the start of the fall semester, Estrada spent his time stocking shelves at a local grocery store. The store manager knew of Estrada’s high school athletic prowess. He urged the youngster to join the local semi-pro San Luis Obispo Blues. “It was the first time a scout ever saw me, and it was purely by accident,” Estrada recalled. “A Milwaukee Braves scout [most likely Bill Marshall] came to one of our games to watch another college-bound pitcher. I started this particular game and struck out the first 15 batters before being lifted so the scout could observe the other guy.” But word soon got around. As Estrada later recalled, three days into the fall semester he was signed by Baltimore Orioles scout and minor league manager Bill Krueger shortly before the former minor league infielder was released by the organization.

Krueger accepted a job as manager of the Salinas Packers in the California League (the Milwaukee Braves’ Class C affiliate) and prevailed upon his former employer to allow him to shepherd Estrada during the right-handed flamethrower’s first professional season. Under Krueger’s tutelage, the youngster placed among the league leaders in nearly every pitching category (unfortunately in walks and home runs as well). On September 8, 1957, Estrada delivered a one-hit win against the Fresno Sun Sox, one of a team-leading 17 wins he collected for the also-ran Packers. The playoffs presented a different picture when the Packers raced to the Governor’s Cup (league championship) with Estrada collecting two of the three wins against the Reno Silver Sox in the best-of-five finals.

Estrada was immediately yanked out of the Braves farm system and advanced to the Orioles’ Class A affiliate in the South Atlantic League. Observed firsthand by farm director Jim McLaughlin throughout the 1958 season, Estrada combined with righty Jerry Walker for nearly half of the Knoxville Smokies’ 67 wins. Highly praised for his remarkable poise, Estrada finished with a record of 15-11, 3.61 and a league-leading 181 strikeouts to earn a September call-up with the Orioles (he did not make an appearance). During the offseason he was selected to report to Miami, Florida, for special instruction in advance of spring training.

In 1959 Estrada reported to the Orioles’ Arizona spring camp as a non-roster invitee. Dubbed the club’s fastest pitcher, he was considered a dark horse candidate to jump to the parent club until a finger blister limited his exposure. Vancouver Mounties skipper Charlie Metro successfully pleaded to have Estrada assigned to him in the Pacific Coast League (AAA). The blister—a problem that occasionally plagued Estrada throughout his career—forced him to the sidelines at the start of the season and he did not collect his first win until May 21. But it was a gem, a seven inning one-hitter against the Spokane Indians. Twelve days later, in a win over the Sacramento Solons, he lost a chance at a shutout when the blister resurfaced and forced him from the game. In an August outing against the Phoenix Giants the blister appeared yet again when, in one of his many double-digit strikeout performances, Estrada was lifted with 10 strikeouts after only six innings. He won six of his last eight decisions to finish with a record of 14-6, 2.85 in 183 innings, missing by three his second consecutive strikeout crown. In September the National Association of Baseball Writers tabbed Estrada as the outstanding AAA right-hander nationwide. The exposure captured the attention of the Philadelphia Phillies who, when the Orioles approached the club during the offseason to acquire first baseman Ed Bouchee, included Estrada in the asking price.

Still a non-roster invitee in 1960, Estrada was selected as the Orioles’ best young pitcher in an informal poll of nationwide scribes. Following a strong spring, he was added to the parent roster. On April 21, 1960, Estrada made his major league debut in Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium in relief of Steve Barber. Entering the fifth inning against the Washington Senators trailing, 3-1, Estrada struck out five of the eight batters he faced, including future HOF slugger Harmon Killebrew, his very first victim. Two days later Estrada made his second relief appearance, this time in Yankee Stadium. Except for a line drive single to center, the Bronx Bombers were unable to get the ball out of the infield over two innings. On April 26 he collected his first major league win with three innings of relief in an 11-10 slugfest against the Senators.

With nine strikeouts and a 1.29 ERA in his first seven innings, the Orioles were anxious to see what Estrada would do as a starter. They got their answer on May 1, when he delivered a complete game 9-5 win against the Yankees. Although he was used primarily in the rotation thereafter, one particular relief appearance stands out. On May 15, Estrada entered a sixth-inning, bases-loaded, no-out situation in Boston’s Fenway Park. He did not allow a run, striking out two of the three batters he faced, including pinch-hitter Ted Williams for the third out. “I have never seen a guy throw any harder than Estrada did that inning,” said veteran teammate Gene Woodling. “He’s going to pitch a no-hitter one of these days.”3 This prediction nearly came true a month later when Estrada carried a no-hitter into the eighth against the Kansas City Athletics before settling for a 9-2 complete-game win. Plagued with arm stiffness in July, he rebounded with his first career shutout on August 9—a four-hit gem against the Detroit Tigers. Two weeks later Estrada established a single game career high of12 strikeouts in a 9-3 complete game win against the Tigers. “[He] has a smooth, easy motion which makes his speed more deceptive,” pitching coach Harry Brecheen explained. “Estrada’s fast ball is by ‘em before they know it. Very definitely, there is no one in the league any quicker than he is.”4

Estrada’s success helped the Orioles to the club’s first season of pennant contention since the franchise played in St. Louis. On September 4 he made a second no-hit bid, leaving the Yankees hitless for 6⅔ innings before settling for a 6-2 victory. The victory put the Orioles two games ahead of New York in the standings, their largest margin since June. But the next day the Yankees launched a 22-4 run to outpace all comers and advance to the 1960 World Series. Estrada was named to both the Topps Chewing Gum Company’s and _The Sporting News_’ All-Rookie teams, with the latter also naming him second-team All-Star right-hander behind Pittsburgh’s 20-game winner, Vern Law. Once again Estrada became the desired target of major league clubs, with the San Francisco Giants making an especially aggressive bid by dangling All-Star outfielder Felipe Alou in exchange for the hard-throwing righty.

Estrada was one of the last players to sign for the 1961 season as he held out for a sizeable pay raise. Nicknamed “El Torro” or “Cha Cha” by his teammates, he hoped to build upon his debut success before elbow problems surfaced. “It felt like somebody was stabbing me,” he said. “I was really worried. I couldn’t throw, I didn’t know what to think.”5 On those few occasions when he could take the mound, the results were troublesome, and the term “sophomore jinx” got a lot of play in camp. Things were no better in Estrada’s first appearance of the season. He walked the first three batters he faced before surrendering a grand slam to Minnesota Twins outfielder Bob Allison. A double by left fielder Jim Lemon ended Estrada’s day with an ERA of infinity. He continued to struggle through the first two months of the season, including two consecutive starts in which he did not survive into the third inning. In an apparent attempt to buy low, the Chicago White Sox dangled outfielders Al Smith or Minnie Minoso for Estrada or one of his fellow Kiddie Korps members—most of whom were struggling, but the offer was rejected.

Estrada’s season turned on a June 6 shutout against the Los Angeles Angels in what proved to be the last whitewash of his career. Plagued by arm problems throughout the remainder of the season, he was still able to win 13 of his last 18 decisions. In an interesting twist, he was the sole beneficiary of Jim Gentile’s AL record-setting five grand slams, each of which were hit when Estrada was pitching. Though he finished with a very respectable record of 15-9, 3.69 in 212 innings, there was cause for concern. Estrada placed among the league leaders in wild pitches and HBP and led the majors with 132 walks. Moreover, the tender elbow would prevent him from ever approaching the 12 complete games he had thrown in 1960.

The 1962 season opened on an encouraging note when Estrada survived spring training entirely pain free. In his first appearance of the season he was seemingly on course for his third career shutout when recurring blisters forced him from the game after seven innings; he settled for a 3-0 win against the Red Sox. But the promising start gave way to misfortune as Estrada compiled a league-worst 17 losses (tying Athletics righty Ed Rakow). He fell victim to bad luck when the Orioles were shut out in four consecutive starts and he lost by two or fewer runs in six other contests, including a heartbreaking three-hit loss to the Angels on September 8. Moreover, in one-third of his starts, Estrada twirled a 2.09 ERA (league average: 3.97) only to show eight losses and three no decisions for his efforts. “[This] is making me a better pitcher,” he insisted. “I have to pitch now. I don’t just stand out there and throw hard. I used to throw and win. Now I pitch and get beat.”6 To make matter worse, Estrada’s elbow did not survive the season. During an at-bat in June, he heard something pop. He was unable to right himself until mid-August while still struggling with his control. In his last appearance of the season Estrada’s three HBP was one shy of a major league record. He yielded a career-high 24 homers and finished with a record of 9-17, 3.83 in 223⅓ innings. One bright spot came on September 13 when Estrada connected for his only major league home run, a two-run shot off Senators righty Jack Jenkins. He was far from a great hitter, but his athleticism led to periodic usage as a pinch-runner throughout his career. Unlike in years past, when the club was continually turning away offers for their star pitcher, during the offseason the Orioles authored a deal for Twins catcher Earl Battey in which they readily offered Estrada; but the trade was declined.

In 1963 many observers believed that Estrada, a high fastball pitcher, would benefit when the MLB Playing Rules Committee decided to enlarge the strike zone from the batter’s armpit to the top of the shoulder. He was not around long enough to find out. Estrada had rested his elbow through the offseason but, instead of showing improvement, it had gotten worse. He yielded 14 runs in his first 14 innings of grapefruit league competition and managed just six innings through the first 26 games of the regular season. Estrada showed improvement in May before being chased in the third in a 7-1 loss to the Angels on June 1. It proved to be his last game of the season after a bone spur and calcium deposits were discovered in his elbow. He was placed on the disabled list on June 8. The team doctor set out a conservative healing approach that Estrada initially abided by before choosing surgery on September 25.

The Orioles hoped to bring Estrada along slowly after the operation. “He’s not the second, third or even fourth starter in our plans,” said club president Lee MacPhail. “[A]t least, not now. We’re figuring without him and, if he comes along, it’ll be a pleasant surprise.”7 Following a strong spring, Estrada began the 1964 season in the bullpen, but was quickly moved into the rotation when Steve Barber went down with a back injury. A promising five inning start in Boston on April 29 was followed by two far less successful appearances through May 9. When Barber returned, Estrada was moved back to the bullpen. In July elbow problems resurfaced, resulting in a near two-month stay on the disabled list. He finished the season with a meager record of 3-2, 5.27 in only 54⅔ innings. In October Estrada travelled south to regain his composure in the Florida Instructional League. He stayed a short time, departing for his California home on November 10.

As the years passed, the relationship between the Orioles and their young pitchers had begun to fray. Managers had grown increasingly tired of the excessive reactions of Estrada, Barber and Milt Pappas when they were lifted from a game; within two years all three would be gone. Saddled with the additional claim of lacking focus when on the mound, Estrada was the first to go. His departure was telegraphed by manager Hank Bauer in the spring of 1965. Asked to assess Estrada’s chances going into the season, the skipper said, “Not until he shows us something . . . He’s got to make the club. We sorta babied him last year with that elbow, but we can’t any longer.”8 Among the last cuts in camp, Estrada was optioned to the Rochester Red Wings. He made 30 appearances (26 starts) with the Red Wings in a forgettable campaign, leading the International League in losses (14) and walks (91) while allowing 82 earned runs and 17 homers, both among the most in the league. Estrada would never throw in the Orioles organization again.

In February 1966, he was sent on a conditional basis to Seattle, the Angels’ Pacific Coast League entry. Despite a brilliant spring as a non-roster invitee with the parent club, Estrada was assigned to the AAA affiliate. “He impressed everyone in camp,” said Angels coach Salty Parker. “He made the club as far as [manager Bill Rigney was] concerned, but [GM Fred] Haney had other ideas and sent him to our Seattle farm . . . I believe the boy felt he had been betrayed after the fine spring he had.”9 Observers were further dismayed in May when, following a promising start in Seattle, Estrada was returned to Rochester. He was immediately returned to the PCL when the Red Wings sold him to Tacoma. On May 18, Estrada debuted with the Chicago Cubs’ affiliate and delivered a four-hit shutout against the Phoenix Giants. Ten days later the Cubs traded relief specialist Ted Abernathy and recalled Estrada. He surrendered just one earned run in his first 5⅔ innings of relief to earn a start against the San Francisco Giants on June 14. Yielding first-inning homers to future HOF outfielder Willie Mays and catcher Tom Haller, Estrada was lifted after facing just seven batters. He made four additional appearances before being returned to Tacoma where he finished the season.

Despite a pedestrian record of 6-8, 3.68 in 132 innings Estrada had, for the first time in six years, successfully completed an entire season pain free. Moreover, during a 38-day span beginning July 22, he collected three wins—two by shutout—while yielding three or fewer hits, a promising surge that did not escape the attention of Bob Scheffing, the New York Mets’ director of player development. In the offseason, the former major league catcher and manager arranged a $20,000 purchase of Estrada for the club’s AA Williamsport, Pennsylvania, affiliate in the Eastern League. Once again Estrada reported to spring training as a non-roster invitee and, on the strength of four perfect innings against the St. Louis Cardinals days before the start of the season, earned a spot on the Mets roster.

On a course for their fifth 100-loss season in only their sixth year of existence, the 1967 Mets shattered the NL record by using 27 pitchers for the season. Estrada’s contribution to this turnstile came on April 13 when he collected the club’s first win of the season with 2⅔ innings of scoreless relief against the Pittsburgh Pirates. Unfortunately, there was little gain thereafter. On June 11, Estrada entered the fourth inning of a slugfest against the Cubs and yielded three home runs, a walk, and a wild pitch while facing just nine batters. It proved to be his last appearance in the majors. The next day- he was sent to the Jacksonville Suns in the International League.

Estrada joined a roster made up of veterans like himself who were trying to resurrect their major league careers (Art Mahaffey and Dennis Bennett), combined with a mix of future stars (Tug McGraw, Amos Otis and, for a short period, Nolan Ryan). Estrada’s challenges in Florida were compounded by a shoulder injury. He managed just 139 innings with the Suns through the 1968 season, compiling a dismal record of 7-15, 5.18 in 36 appearances (24 starts). Staring at retirement, Estrada was signed by the Mets’ new director of player development, Whitey Herzog, as player-coach for the Visalia Mets in the California League, —the circuit in which the righty had begun his professional career 12 years earlier. A rested shoulder allowed the 31-year-old the means to throw again and Visalia manager Roy McMillan offered that Estrada “is throwing fine now. He is far from through.”10 He carried a record of 5-1, 1.85 into June and appeared poised for more. But a few weeks later Estrada removed himself from a game with two outs in the ninth when the elbow gave way. On July 12, 1969, after the arm did not respond to treatment, Estrada retired from the club altogether. He returned to his home in California and launched a career outside of baseball.

These outside ventures were short-lived after Wes Stock, the Mets’ minor league pitching coach and Estrada’s former Oriole teammate, left the organization to join the Milwaukee Brewers. The Mets turned to Estrada to replace him. “He has the right temperament [to coach],” said club farm director Joe McDonald. “[T]he players, especially the young pitchers, like him.”11 From 1970 to1972, Estrada helped the budding careers of Buzz Capra, Nino Espinosa, and Craig Swan among many others. When Herzog was enticed away from the Mets to become the manager of the Texas Rangers, his first managerial job at the major league level, one of the first people he tapped to join him as pitching coach was Estrada. The job proved taxing to both when the 1973 Rangers, among the youngest clubs in baseball, endured its second consecutive 100-loss season. An MLB worst 4.64 ERA was achieved by a league-high 20 pitchers. When Estrada was asked his process for selecting a relief pitcher, he cracked, “Whoever answers the bullpen phone.”12 Following a particularly grueling 14-0 loss to the White Sox on September 4, Rangers owner Bob Short approached his manager to replace Estrada. Herzog instead stood by his friend, a decision that cost both him and Estrada their jobs.13

Over the next four years Estrada served as the minor league pitching coach in the Braves, Angels, and San Diego Padres organizations. In 1978 he returned to the majors to replace Roger Craig, who was promoted from pitching coach to the Padres manager. The club’s 15-game improvement from the preceding year was largely credited to Estrada, who guided the Padres to a 3.28 ERA. Former Cy Young award winner Randy Jones was particularly effusive in his praise of Estrada. The only coach to survive when the axe fell on Craig and his successor, Jerry Coleman, Estrada left the organization after the 1981 season. He joined the Charleston Charlies staff in the International League—Cleveland’s AAA affiliate—and was advanced to the Indians in May 1983, after pitching coach Don McMahon underwent a quintuple bypass. Estrada retired in the 1990s after coaching stints in the Oakland Athletics and Colorado Rockies organizations.

During the early days of his major league career, Estrada enjoyed the life of a carefree bachelor and at one point dated Lee MacPhail’s secretary. In December 1965 he married Georgiana Martinez, a woman six years his junior whom he met at a party in San Luis Obispo. The union dissolved in divorce nine years later, but not before producing his only child, a daughter (Ginger Marie) born in 1971. Two subsequent marriages also ended in divorce. Estrada was an avid golfer and was fanatical about watching most sports either in-person or on television. Both during and after his career he generously gave of his time, including one instance in St. Petersburg, Florida, during his coaching career, in which he pitched three innings of an Old Timers game, the proceeds from which benefitted the March of Dimes. In 2007, Estrada was inducted in the inaugural class of Atascadero High School’s Athletic Hall of Fame. Through 2016 he remains one of only two alums to have reached the major leagues (infielder Scott McClain being the other).

Estrada’s 18 wins in 1960 marked only the second time since 1944 that a franchise pitcher (dating to the former St. Louis Browns) earned more than 15 wins in a season. (The same 18-win mark stood as an Orioles’ single-season record for two years.) Much more was expected from the hard-throwing righty who concluded a seven-year major league career with a record of 50-44, 4.07 in 764⅓ innings. “The thing that bothered me the most about my short career is the fact that I was just learning how to pitch when my arm blew out,” Estrada said years later. “I used to challenge everybody.”14 Through his many years of coaching, he extended his baseball career over five decades—a mark representing a true baseball lifer.

Last revised: August 10, 2016

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank SABR members Jacob Pomrenke, Dr. Fred Worth and Rod Nelson, chair of the SABR Scouts Committee for their valuable research.

Sources

Ancestry.com

Chuck Estrada, telephone interview, June 11, 2016; unattributed quotes derive from this conversation.

Notes

1 The only modern era pitcher to join this pair is HOF righty Pete Alexander in 1911 with 28 wins.

2 Orioles pitching coach Harry Brecheen would be blamed for overworking and eventually ruining the arms of Estrada and fellow Kiddie Korps hurlers Steve Barber, Wally Bunker, Jack Fisher and Jerry Walker.

3 “Barber’s Close-Shave Hurling Leaves Oriole Foes in Lather,” The Sporting News, May 25, 1960: 7.

4 “Hats Off . . . Chuck Estrada,” ibid., July 13, 1960: 28.

5 “Estrada Chases Gloom With Blazing Humer,” ibid., March 28, 1962: 21.

6 “Estrada Ranks as Tough-Luck Champ on Slab,” ibid., July 14, 1962: 24.

7 “Birds Watch for Signs of Life in Estrada Wing,” ibid., November 23, 1963: 6.

8 “’You’ve Gotta Show Me,’ Bird-Watcher Bauer Tells Estrada,” ibid., March 13, 1965: 10.

9 “Old, New, Borrowed, Blue—The Mets,” ibid., March 11, 1967: 13.

10 “Class A Leagues,” ibid., May 3, 1969: 44.

11 “New Job for Estrada—Tutoring Mets’ Kids,” ibid., January 24, 1970: 45.

12 “Insiders Say,” ibid., July 28, 1973: 6.

13 Short’s decision to fire Herzog and Estrada was made all the easier with the Detroit Tigers’ September 2 firing of manager Billy Martin, who immediately took over the Rangers helm.

14 The Minor Leaguers of 1990: The Greatest 21 Days, “Chuck Estrada, In Condition,” January 3, 2015. Accessed June 20, 2016, http://bit.ly/28IdcnI