Ray Noble – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

Rafael Noble (pronounced NO-bleh) was a stocky, powerful catcher. “Look at my guy Ray Noble,” said his manager with the New York Giants, Leo Durocher, in early 1952. “If I didn’t have Wes Westrum, he’d be my No. 1 man. He’s a good catcher and he has a lot of power. He’d be even better if he played every day. And he can do it. He’s a bull back there. He could catch 154 games.”1

Rafael Noble (pronounced NO-bleh) was a stocky, powerful catcher. “Look at my guy Ray Noble,” said his manager with the New York Giants, Leo Durocher, in early 1952. “If I didn’t have Wes Westrum, he’d be my No. 1 man. He’s a good catcher and he has a lot of power. He’d be even better if he played every day. And he can do it. He’s a bull back there. He could catch 154 games.”1

It didn’t work out that way. The Afro-Caribbean from Cuba played in just six games for the Giants in 1952 and 46 more in 1953, and that was the end of his big-league action. His only full season in the majors came in 1951.

What happened? Noble was a solid all-around catcher – the best that Cuba has ever produced, according to some observers. One of those is Paul Casanova, himself a Cuban catcher who played in the majors from 1965 through 1974. Speaking in 2013, Casanova cited Noble’s great arm, the way he handled pitchers, and his hitting.2 Noble got a late start in the pros, however, and the color barrier meant that he played in the Negro Leagues from 1945 to mid-1949. He then played Triple-A ball during 1949 and 1950 before making “The Show” at last at the age of 32. However, Wes Westrum – also highly regarded for his skills behind the plate – remained number one with the Giants despite a series of hand injuries. Noble hit just .218 in his sporadic big-league opportunities.

Ray – who, like many Latinos in that era, got an Americanized nickname in the US – also played under the shadow of ongoing racism. Yet he continued in Triple-A as late as 1961. His career in the Cuban professional winter league also lasted through the circuit’s final season, 1960-61. Over 16 seasons at home, Noble hit 71 homers, making him the league’s all-time leader.

Rafael Miguel Noble Magee was born on March 15, 1919. During his career, Noble’s year of birth was shown as 1922, but he was one of many players over the years to change it for professional purposes. An ongoing point of difference is his place of birth within Cuba. Baseball references show it as Central Hatillo, but according to Aldo Betancourt Hernández, father-in-law of Paul Casanova, it was Central Santa Ana de Auza, in the municipality of San Luis. Betancourt wrote a history book about San Luis, his hometown, in 2008.3

A central, in Cuba’s old economy, was a giant sugar-mill complex. Rafael’s parents (whose given names have been lost to time) worked in this industry. The English surname of Rafael’s mother was a tipoff to her family’s origins in the British West Indies – specifically, Jamaica. Between 1902 and 1933, approximately 115,000 Jamaicans emigrated to Cuba, mainly to work as laborers in the centrales.4

In fact, the elder Noble was Jamaican too, and the family name was originally pronounced the English way. Cuban baseball author Ángel Torres also wrote that Rafael’s father would always refer to the boy as “My Son” instead of calling him by name. “Son” became Noble’s nickname, but it was often written as “San” by mistake because many people didn’t know the story. 5 That error also arose because the sound is much closer to an “a” in Spanish.

In Cuba, the Noble family took up residence in Palma Soriano, in the province of Oriente, in the eastern part of the country. There is limited information about Rafael’s siblings, but he had some in both Jamaica and Cuba. Among them was a brother, Juan Noble, who also played in the Negro Leagues. Juan was with the New York Cubans – the same team for which Rafael had played – in 1949 and 1950.6 Rafael, Juan, and their sister María were the three who went to the United States.

As a young man, Rafael Noble worked as a stevedore in Central Santa Ana, which was also located in Oriente, about 35 kilometers (21 miles) from the nation’s second biggest city, Santiago. Each sack of sugar was immensely heavy – 13 arrobas, or 325 pounds.7 Burly to begin with, Noble gained even greater strength from this hard manual labor.

Noble’s baseball career also began with Central Santa Ana’s team in the late 1930s. From then until the early 1940s, he also played for teams affiliated with Cuban Mining and Santa Clara.8 This was in “sugar mill” competition; the centrales were generally the only organizations in rural Cuba that could afford to equip teams. Nonetheless, the level of play was quite high – sometimes even higher than that of the Cuban League in Havana, according to Cuban baseball author Roberto González Echevarría, even though there may not have been a set schedule. The Cuban Mining squad, based in Cristo, Oriente province, was the most famous of these teams.9 Then, from 1942 through 1944, Noble was with the Contramaestre Rifleros, another highly regarded sugar-mill club in Oriente.10

In the winter of 1942-43, Noble – who had impressed local scouts – got his first experience in the Cuban winter league. He was 0-for-3 in three games for the Havana Rojos (or Reds). He did not play the following three winters in Cuba, even though the league was still functioning despite World War II. Roberto González Echevarría noted that Noble played at least two winters in Panama, with the Cervecería team.11 During the 1945-46 season, he won the batting title with a .300 mark. 12

Noble was also still toting sacks of sugar. He later recalled that he was earning $6 a day (or six Cuban pesos, then equal in value to a dollar). It wasn’t bad money for the time and place. In 1945, however, Alex Pómpez, owner of the New York Cubans in the Negro National League, approached him with an offer to come to the United States. Noble said he found it easier work, so he stayed up north.13

In the winter of 1946-47, Noble returned to the Cuban winter league, joining the Cienfuegos Elefantes and staying with that team for 14 seasons. The prime of his career there overlapped his time in the major leagues. In that first winter-league season, though, he got just 82 at-bats in 42 games, playing behind American Red Hayworth. Cienfuegos manager Martín Dihigo, the great Hall of Famer, brought Hayworth in because he was concerned that Noble was a liability behind the plate. “Early in his career there were questions about Noble’s defensive ability,” wrote Roberto González Echevarría, “but as the years progressed he improved and became a solid receiver with a strong arm. He was a rock blocking the plate.” Noble also hit some of the longest homers at Havana’s Gran Stadium, which was not conducive to the long ball. He could clear the warehouse behind the left-field fence there.14

The summer of 1947 was a memorable one for the New York Cubans. Author Adrián Burgos, Jr. wrote about it in his biography of Alex Pómpez, Cuban Star. Despite an impressive array of talent, the Cubans got off to an inconsistent start, but they surged in the second half of the season and brought Pómpez his first pennant in his 30 years in the Negro Leagues. New York then defeated the Cleveland Buckeyes, champions of the Negro American League (or West), in the Negro World Series. Noble was one of the batting stars of the five-game victory. In Game Three, at Shibe Park in Philadelphia, he hit a towering grand slam that struck the top of the left-field roof; the Cubans won, 9-4. In the clinching Game Five, at Chicago’s Comiskey Park, his two-run double put New York ahead to stay, 6-5.15

Burgos also described how after the 1948 season, Pómpez – strapped for cash – entered a working agreement with the New York Giants. The Cubans became an informal Giants farm team, and the first transactions between the clubs came in June 1949. Pómpez sold Noble, player-manager Ray Dandridge, and pitcher Dave “Impo” Barnhill to the Giants for $21,000.16 It was the beginning of the end for the Cubans – the franchise went defunct after the 1950 season.

Noble finished the 1949 season with Jersey City, the Giants’ Triple-A affiliate in the International League, where he batted .259 in 67 games. In 1950 he was assigned to the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League and had a very strong year, hitting .316 with 15 homers and 76 RBIs in 110 games for the PCL pennant-winners. In mid-September Oaks manager Charlie Dressen reportedly said that he wouldn’t trade Noble for any other catcher in the business.17

But on October 11, 1950, Oakland and the Giants swung a deal in which Noble, shortstop Artie Wilson (another Negro League star), and pitcher Al Gettel went to New York in exchange for four players and $125,000. The irony was that the Brooklyn Dodgers named Dressen their manager that November. He led the Dodgers for the next three years, during the height of their rivalry with the Giants, and that coincided with Noble’s time in the majors.

During the winter of 1950-51, the Giants got word that Noble was catching with a bad wrist because he was wearing a leather brace on the joint, which he had injured while playing with Oakland. Cienfuegos owner Bobby Maduro assured the Giants that Noble was healthy and arranged to have X-rays taken. Noble flew to New York and “when the Giants were convinced that the reports they had were unfounded, he returned to Cuba.”18

Noble reported to spring training in late February at 214 pounds, about 15 more than his typical playing weight (at least then).19 Nonetheless, Leo Durocher liked what he saw. A few days later, he raved to reporters, “That’s him. Look at him. He looks like a black lion. Look at those shoulders. That’s power, boys. They tell me he can do everything. He’s like a cat behind the bat. He can throw; he can hit; he can run.”20

Noble hit much better than Wes Westrum in camp and made the Giants roster for 1951. He was originally viewed as an “insurance” catcher, but his performance prompted talk in late March that he might take the starting job.21 In early April, however, he suffered a severely sprained ankle while sliding into home plate in an exhibition game against the Boston Red Sox. It bothered him all year.

Noble made his big-league debut on April 18 when he caught the ninth inning of a game at Braves Field in Boston. By coincidence, that inning also marked the debut in the majors of another notable Latino player, Luis “Canena” Márquez from Puerto Rico. Noble became the second black catcher in modern major-league history, after Roy Campanella – though it’s well worth remembering that Fleet Walker played catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1884.

During the 1951 season, Noble appeared in 41 games behind the plate, with 26 starts. He hit .234 with five homers in 141 at-bats; the first round-tripper came off Warren Spahn of the Braves on April 27. It was Noble’s first start and first time playing in the majors at the Polo Grounds, which had also been the home field of the New York Cubans. One month and a day later, Spahn gave up a much better-remembered first home run: number 1 of 660 for Willie Mays.

Noble’s single biggest day in the majors came on May 9. At the Polo Grounds, he led a 17-3 drubbing of the St. Louis Cardinals by going 4-for-6 with two homers and five RBIs. The second of those homers, off Al Brazle, was described as “a towering blast, estimated at 500 feet, that cleared the roof of a building behind the left field wall.” Noble liked to use the whole field, though. “I punch better than pull,” he said. “When I try to pull I miss too many. They play me to pull. But when I got to get a hit I try to punch to right.”22

A foul ball had broken Westrum’s finger on May 1. So, from May 2 through May 17, Noble started 14 out of 15 games (resting in the nightcap of a doubleheader on May 6). His average got as high as .286 after a 7-for-13 three-game burst during this stretch. Sportswriters were saying, “Rafael Noble … has [Westrum] chained to Leo Durocher’s bench” and “Westrum will have a tough time getting back his backstop position from the hitting, hustling Rafael Noble.”23 Nonetheless, as soon as Westrum was ready to play, he did reclaim the starting job.

Noble played on his bad ankle that summer even though it affected his running (not a strength to begin with) and his hitting, which he viewed as his bread and butter. “That is how I been in baseball,” he said. “Hit.”24 Also, as Joshua Prager described in his book about the 1951 Giants, The Echoing Green, Leo Durocher began to use third-stringer Sal Yvars more – despite the history of bad blood between the manager and Yvars.25

In mid-September, however, Noble enjoyed another brief flurry of activity. Westrum was ejected in the first inning at Wrigley Field in Chicago on September 14, and Noble went 2-for-4 with an RBI. National League President Ford Frick suspended Westrum for three games because he had pushed umpire Al Barlick, and Noble stayed in the lineup for all three, including both ends of a doubleheader at Pittsburgh on September 16. There was another factor, as Prager recounted. On September 15 Durocher had sent Sal Yvars to the racetrack with $800 in bets from the team on a surefire tip that the skipper had gotten from one of his Hollywood cronies, actor George Raft.26

Noble did not play in either Game One or Game Two of the three-game playoff against Brooklyn to decide the 1951 pennant. In Game Three he entered in the ninth inning after Bill Rigney had batted for Westrum. It’s often mentioned that Willie Mays was on deck when Bobby Thomson hit “The Shot Heard ’Round the World” – but it gets little if any attention that Noble was due up after Mays.

During the 1951 World Series, Noble got into two games, both at Yankee Stadium – which he also knew from occasional games with the Cubans, including Game Two of the 1947 Negro World Series. He went 0-for-2 as a pinch hitter. In both Game Two and Game Six, the Giants had rallies brewing, and Leo Durocher sent pinch-runners in for Westrum after the catcher had reached base. Noble batted for the pitcher, both times with two outs, but could not bring in the runners. Each time he stayed in as catcher the rest of the way.

In particular, Noble regretted the second of those opportunities – with the bases loaded, Johnny Sain of the Yankees caught him looking at a curveball for strike three. Ray later said, with his fingers curled around a long black cigar, “If I ever get another chance, I swing at anything close.”27 He was out of the Giants organization, however, before they won their next pennant in 1954.

The winter of 1951-52 was one of Noble’s best. He hit .321-7-39 for Cienfuegos, finishing second in the batting race behind Bert Haas, who had been part of the deal with Oakland. Noble’s manager with the Elefantes, Billy Herman, said, “He stands out by far as the best receiver in the Cuban League.”28 Herman later added, “I always thought he was a big-league catcher.” Noble also earned praise from two longtime veterans of the Cuban scene. Miguel Ángel “Mike” González called him “100 percent improved” and Óscar Rodríguez called him “another Campanella.”29

Noble reported to spring training in 1952 two weeks late – though he cited a good reason: he had gotten married.30 The wedding, to a young American woman named Norma Jean Goode, took place in Havana on December 29, 1951.31 Norma, a beautician from New Jersey, was a childhood friend of Monte Irvin’s wife, Winnie. The pair went to the Polo Grounds for the Giants’ first home night game in 1951. When Ray met Norma, they hit it off straightaway.32 Indeed, when the wedding took place, the couple was already expecting their first child – they welcomed a little boy in June 1952.33 Rafael Juan Noble later became a character actor, acting coach, and writer-producer.

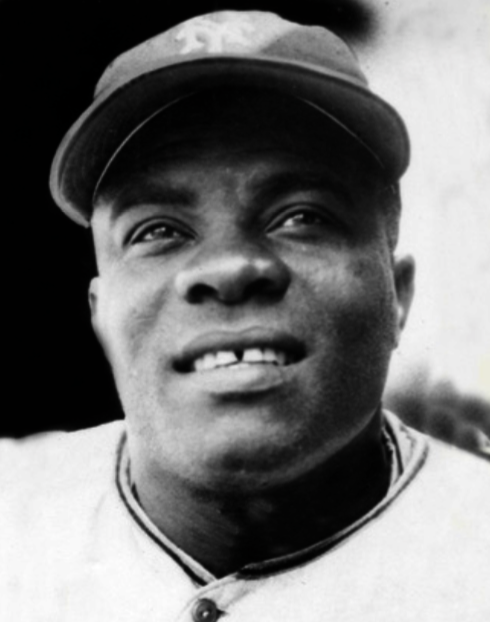

Noble passed on the news of his wedding with a smile, which was one of his notable features – broad, beaming, and gap-toothed. In this regard, he bore some resemblance to Michael Strahan, the football star turned media personality.

Reporting late to camp really wasn’t a factor after playing winter ball, and Durocher was happy with Noble’s performance in Phoenix. “What I liked best,” said Leo, “was his first home run. It was on exactly the same kind of pitch that Johnny Sain struck him out with in the last game of the World Series. He just stood there taking it last fall, but he didn’t this time.”34

Still, even though Durocher was bullish, Noble got hardly any opportunity with the Giants in 1952. Instead, Sal Yvars became the team’s primary backup. Noble played in just six games during April, May, and the first half of June. Then the Giants returned him to Oakland on option, as partial payment in the deal by which they obtained pitcher Hal Gregg. New York did not recall him, even though Wes Westrum suffered a broken finger on June 19.35

Meanwhile, after he went back to the Oaks, Noble caught every inning in 62 straight games before manager Mel Ott finally gave him a rest.36 He also hit well too: .298-12-60 in 104 games. Oakland’s owner, Brick Laws, wanted to purchase Noble’s contract outright.37 This too may have hindered a return to the Giants. For example, Artie Wilson’s great popularity in Oakland was one reason why he was sent back there in 1951 – Laws wanted Wilson’s drawing power at the gate.38

Yet perhaps the most notable event for Noble that summer took place on July 27 – a bench-clearing brawl in a game with the San Francisco Seals. Authors Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt described it as “one of the most vicious and overtly racial fights in baseball history.” At its root was Seals pitcher Bill Boemler, who had repeatedly thrown at Noble and another former Negro Leaguer on the Oaks, Piper Davis. Davis saw an opportunity to retaliate in a play at the plate. He bowled into Boemler, whose tag was apparently more of a punch.39

One wire service account of the subsequent melee said, “The riot … was not typical of most baseball fights. Blows were actually flung, hitting targets consistently. … Catcher Ray Noble was prominent among the blow tossers. He was the most aggressive of the Oaks.”40 Another report said, “[Noble] showed no partisanship, punching at any Seal face which got in the way of his burly fist.”41 There was still more vivid description – Noble “knocked down San Francisco players as though they were ten pins.” According to Davis, “Noble was hitting everything white coming towards him.”42

Noble, as did the other players of African descent in his era, had to contend with racism in various ways. In 1951 Giants teammates Eddie Stanky (known for his use of racial invective) and Alvin Dark (who remained suspect in this area) called him “Bushman” after the world-famous gorilla of Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo. When Noble figured the reference out, he reportedly told Durocher that the Giants might lose their double-play combination.43 Plus, the unspoken practice of racial quotas influenced the Giants roster in the early 1950s. This was another factor in Artie Wilson’s demotion in 1951 – “he knew that if Mays was coming, either he or Noble was going.”44

Later, in both 1952 and 1953, the club’s black players were put up in a separate – and inferior – hotel on spring-training trips to San Francisco. Sam Lacy, the esteemed sportswriter for the Afro-American, made it a point to raise the recurring issue with club executive Chub Feeney. Feeney and owner Horace Stoneham promised that it wouldn’t happen again.45

Noble was with the Giants in camp in 1953 because the club had recalled him, along with some other players, under its working agreement with Oakland. Right around the time of the hotel episode in San Francisco, though, trade rumors about the catcher circulated once again. New York was reportedly willing to sell the contract of “perhaps the strongest man in baseball” to the Chicago White Sox. The asking price was $25,000.46

Instead, Noble was farmed out to Triple-A Minneapolis. He hit well and returned in late May, in large part because New York wanted somebody to handle Hoyt Wilhelm’s knuckleball. Noble would be neither the first nor the last catcher to have trouble with the pitch, however – on May 28, against Brooklyn at Ebbets Field, Wilhelm was charged with four wild pitches and Noble with one passed ball. Two of those miscues came in the tenth inning, giving the Dodgers a 7-6 win.47

On June 15 the Giants sold the contract of Sal Yvars to St. Louis, but Noble fell out of favor and did not play a great deal in the second half of the season. He had started well at the plate but slumped, finishing at .206-4-14 in 119 at-bats over 46 games. As the Giants set off for a postseason tour of Japan, The Sporting News described Ray’s future with the team as “extremely dubious.”48

Noble did not cross the Pacific; instead, he went back to play with Cienfuegos. In 1953-54, he tied for the league lead in homers with 10, while batting .281 and matching his winter high with 39 RBIs. Meanwhile, in late 1953, Bobby Maduro had obtained the rights to the Springfield (Massachusetts) franchise in the Triple-A International League and won approval to move it to Havana. In January, the word was out that Maduro was looking to sign Noble as Havana’s first-string catcher.49 It was no surprise that the Sugar Kings stocked their roster with many Cuban players. In March 1954 Havana purchased Noble’s contract from the Giants. He knew which way the wind was blowing, for he did not report to spring training with the Giants (though he did send a cable asking for transportation money).50

The Cincinnati Redlegs (as they were then known) supplied the Sugar Kings with several players in 1954. Their general manager, Gabe Paul, was a friend of Maduro’s. That August, Cincinnati signed a formal working agreement with Havana, making the Sugar Kings their top farm club. Before the 1955 season, the Redlegs obtained the rights to Noble from Havana as part of the agreement.

Noble had two solid summers while playing in his homeland, but he did not make it back to the majors. At some level, Maduro’s ambition to have a major-league franchise in Havana may have hampered a possible return. The Cuban fans also demanded a good product on the field. On the other hand, even though the Reds used several different catchers in 1954 and 1955, the veteran was advancing in age and may simply have been labeled a Triple-A player by that point.

In September 1955 Cincinnati traded Noble to the Kansas City Athletics for third baseman Hal Bevan. He spent the next three seasons in the A’s organization as the starting catcher at Triple-A – 1956 at Columbus, 1957 and 1958 at Buffalo. He hit 21 and 20 homers in his two years with the Bisons, whose home ballpark then was cozy, hitter-friendly Offermann Stadium.

Noble’s last season as a full-time player was 1959, when, at 40 years of age, he hit .294 in 138 games for Houston of the American Association, which at that time was not affiliated with any major-league club. The Buffs became a farm team of the Chicago Cubs in 1960, and Noble still got into 92 games, batting a still solid .274.

Cienfuegos won two Cuban league championships while Noble was a member of the team, in 1955-56 and 1959-60. The star pitchers for those teams were Camilo Pascual and Pedro Ramos. Pascual once told Roberto González Echevarría, “Noble was so big I could hardly miss him. He was a great target.”51

The Caribbean Series, which pitted the region’s winter-league champs against each other, started in 1949. Its first era ran through 1960, and Noble got to play in three of those tournaments. In addition to the two with the Elefantes – both of which the Cubans won – he reinforced Marianao’s roster in the 1958 edition. Overall, he was 11-for-35 (.314) in this competition. His 6-for-15 performance in 1956 led all batters, and he was named Series MVP.

Cuban professional winter baseball came to an end in the winter of 1960-61. During this final season, only native players were on the rosters. Noble finished his career at home back where it began, with the Havana Rojos. He hit .171-0-8 in 43 games, bringing his lifetime totals to .256-71-378 in 879 games.

Like many of his compatriots, Noble faced some delays getting out of Cuba in early 1961, amid political tension. He finished his playing career with a handful of appearances for Houston that spring. On April 20 he hit a grand slam to help power a seven-run ninth-inning rally that gave the Buffs a 10-7 win over Dallas-Fort Worth.

After retiring as a player, Noble decided to return to his native land. His marriage to Norma had ended when little Rafael was very young. A 1958 article from Buffalo showed him with three children – one may surmise that the two others came from his second marriage.52

Then, as Adrián Burgos wrote, “just two years after his arrival, Noble’s job as a baseball coach disappeared within the restructured society. Noble chose to remain in Cuba. However, a decade after his return, Cuba’s turbulent political and economic climate prompted his decision to migrate back to the United States.”53 His daughter Daisy remained in Cuba.

Noble settled in Brooklyn, New York, where he ran a liquor store.54 He lived at 698 Chauncey Street, in the Bushwick neighborhood. He was not involved with baseball. Burgos wrote, “The closest of ‘Ray’ Noble’s neighbors knew him as a bear of a man, strong and hardworking; little did they know he had participated in the championship series of the Negro leagues, the major leagues, and the Caribbean.”55 Fellow players still paid their respects, though – for example, Paul Casanova met Noble during this period. Although they never played together, Casanova greatly appreciated how men like Noble had opened the door for him and others to play.56

The Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame (in exile) inducted Rafael Noble in 1985. He also threw out the ceremonial first pitch for a Cuban veterans’ game at Roosevelt Stadium in New Jersey in 1991. His catcher was Roberto González Echevarría, who observed that Noble seemed to have shrunk physically, and that one of his legs had been amputated because of diabetes. At a banquet that night, Noble told the Yale professor that he considered letting himself die rather than lose his leg, but that he was glad he had changed his mind.57

Noble died in Cabrini Medical Center in Manhattan on May 9, 1998. The cause was complications from his diabetes. He was survived by his second wife, Haydee Moran, and a son named Ernesto – as well as Norma, their son Rafael, and Daisy (who were not mentioned in his obituaries).58 Noble was buried in Brooklyn’s Cypress Hills Cemetery, which is also the resting place of Jackie Robinson.

This biography appears in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III. It was most recently updated on January 12, 2021.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Rafael J. Noble, Paulino Casanova, Aldo and Emma Betancourt, and Zaida Aguirre (niece of Rafael Noble) for their assistance. Sra. Aguirre’s e-mails in January 2021 provided more background on Noble’s family and his later life.

Continued thanks to SABR member José Ramírez, who obtained the input from Casanova and the Betancourts, and to Roberto González Echevarría.

Sources

Betancourt Hernández, Aldo, Historia de Mi Pueblo (self-published, 2008).

Burgos, Adrián Jr., Cuban Star (New York: Hill and Wang, 2011).

Figueredo, Jorge S., Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc.: 2003).

Echevarría, Roberto González, The Pride of Havana (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Torres, Ángel, La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 1878-1997 (Miami: Review Printers, 1996).

Burgos, Adrián Jr., “Playing Ball in a Black and White ‘Field of Dreams’: Afro-Caribbean Ballplayers in the Negro Leagues, 1910-1950,” Journal of Negro History, Volume 82, No. 1 (Winter 1997). Burgos conducted a personal interview with Rafael Noble on February 24, 1995.

baseball-reference.com

retrosheet.org

paperofrecord.com (various small items from The Sporting News)

fultonhistory.com (source for New York state newspapers)

Notes

1 Edgar Munzel, “Lip Sounds Off – Baffled by Cub Buildup System,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1952, 6.

2 Telephone interview, Paul Casanova with José Ramírez, October 24, 2013.

3 Aldo Betancourt Hernández, Historia de Mi Pueblo; Telephone interview, Aldo Betancourt with José Ramírez, October 30, 2013.

4 Margarita Cervantes-Rodríguez, International Migration in Cuba (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010), 117, 121. Aldo Betancourt’s book notes that the vicinity of San Luis was heavily influenced by Haitians, who migrated to the area starting in 1791, as the Haitian Revolution began.

5 Ángel Torres, La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 1878-1997, 169.

6 “Lowdown on NY Cubans Reveals Plenty Power,” New York Age, April 29, 1950, 22.

7 Torres, La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 169.

8 Negro League Player Register, Center for Negro League Baseball Research (cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Players%20Register/M-N.pdf).

9 Roberto González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, 201.

10 Torres, La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 169.

11 González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, 288.

12 “G.E. Wins Panama Pro Title,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1946.

13 “Baseball Men Expect Great Things From Cuban Catcher,” Associated Press, February 15, 1952.

14 González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, 31, 288. E-mail from Roberto González Echevarría to Rory Costello, September 23, 2013.

15 Adrián Burgos, Jr., Cuban Star, 171-176.

16 Burgos, Cuban Star, 182-183.

17 Jack McDonald, “Chuck’s Acorn Stars to Haunt Him as Giants,” The Sporting News, February 21, 1951, 2.

18 J.G. Taylor Spink, “U.S. Players Get Polish; Gonzalez Gold in Havana,” The Sporting News, January 10, 1951, 2.

19 “Giants’ Noble Must Work,” wire service report, February 25, 1951.

20 “Leo Raves About Noble at Camp,” Washington Afro-American, February 27, 1951, 18.

21 “Noble May Swipe Westrum’s Post,” United Press, March 27, 1951.

22 “Baseball Men Expect Great Things from Cuban Catcher.” Confirmation that the tape-measure shot came off Brazle: Joe Reichler, “Noble Leads 21-Hit Attack Against Limping Redbirds,” Associated Press, May 10, 1951.

23 Charles J. Tiano, “Short Takes,” Kingston (New York) Daily Freeman, May 18, 1951, 13. Les Matthews, “Sports Train,” New York Age, May 19, 1951

24 “Ray Noble Regains Catching Form in the Cuban League,” Associated Press, February 13, 1952. This story was a variant of “Baseball Men Expect Great Things from Cuban Catcher.”

25 Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006), 93-94.

26 Prager, The Echoing Green, 105-107.

27 “Baseball Men Expect Great Things from Cuban Catcher.”

28 Pedro Galiana, “Herman Back in Majors; Cubans Toss Luncheon,” The Sporting News, January 23, 1952, 22.

29 “Baseball Men Expect Great Things from Cuban Catcher.”

30 The Sporting News, March 12, 1952, 26.

31 “Wed to Ball Player,” Washington Afro-American, January 15, 1952, 10. Jet, February 7, 1952, 44.

32 Sam Lacy, “Girls Behind the Guys,” The Afro-American, April 8, 1952.

33 Sam Lacy, “From A to Z With Sam Lacy,” The Afro-American, June 24, 1952, 15.

34 “Lippy Goes to Bat for Henley, Gail Hits Ball for Leo,” The Sporting News, March 19, 1952, 18.

35 “Three Clubs Still Lag in Attendance,” The Sporting News, June 25, 1962, 23. “Giant Glints,” The Sporting News, June 25, 1952, 13.

36 The Sporting News, August 27, 1952, 32.

37 Johnny Page, “Page in the Sportbook,” Amsterdam (New York) Recorder, July 15, 1952, 10.

38 Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt, Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers, 1947-1959 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1994), 68.

39 Moffi and Kronstadt, Crossing the Line, 64-65.

40 “Seals Thump Oaks Twice,” United Press, July 28, 1952.

41 “PCL Fans See Grappling Bout at Home Plate,” United Press, July 28, 1952.

42 Moffi and Kronstadt, Crossing the Line, 65.

43 Jack Hernon, “The Lip’s Keystone Combination Threatened,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 19, 1951, 11.

44 Gaylon White, “Thank God, We Saw the ‘Say Hey Kid’ Play,” The Bilko Athletic Club website (bilkoathleticclub.com/bunts/thank-god-we-saw-the-say-hey-kid-play/). Extract from the book published in February 2014 by Rowman & Littlefield. Originally published in 2001 on the Society for American Baseball Research website.

45 Sam Lacy, “Giants to Outlaw Calif. Hotel Policy,” The Afro-American, March 31, 1953, 15.

46 “Chisox Can Get Noble for 25Gs,” United Press, March 26, 1953.

47 “Noble, Brought Up to Catch Knuckler, Fails in Big Test,” The Sporting News, June 3, 1953, 15.

48 Arch Murray, “Giants in Japan, Trip Hailed as Aid in International Affairs,” The Sporting News, October 14, 1953, 19.

49 “Cubans Pick ‘Sugar Kings’ as Nickname,” Associated Press, January 11, 1954.

50 “Giants Sell Noble to Cuban Team,” United Press International, March 6, 1954. “Ray Noble Only Giant Absentee,” Associated Press, March 4, 1954.

51 Email from Roberto González Echevarría to Rory Costello, September 23, 2013.

52 “No. 5 Rafael Noble, Catcher,” Buffalo Courier-Express, May 25, 1958, Pictorial-47.

53 Adrián Burgos, Jr., “Playing Ball in a Black and White ‘Field of Dreams’: Afro-Caribbean Ballplayers in the Negro Leagues, 1910-1950,” Journal of Negro History, Volume 82, No. 1 (Winter 1997).

54 “Ray Noble, New York Giants Catcher, 79,” New York Times, May 12, 1998.

55 Burgos, Cuban Star, 236.

56 Telephone interview, Paul Casanova with José Ramírez, October 24, 2013. As a teenager, Casanova was on the roster of the Almendares Alacranes during the last two seasons of the Cuban professional league, but he never got into a game.

57 González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, 404.

58 “Ray Noble, New York Giants Catcher, 79”; “Former Giant Ray Noble Dies,” Associated Press, May 10, 1998. Haydee’s maiden name provided by Aldo Betancourt.