Artie Wilson – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

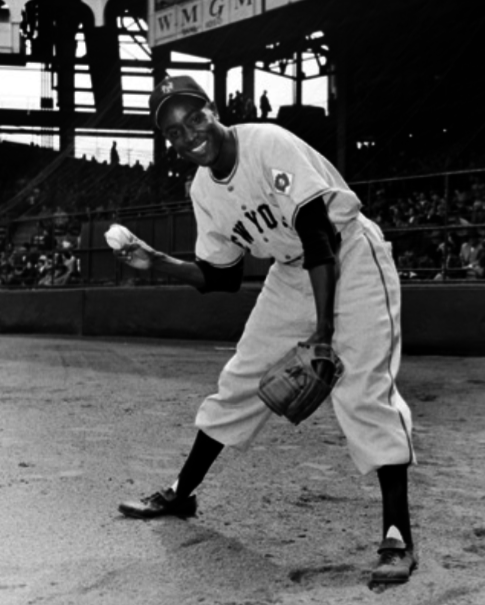

Artie Wilson’s career makes just the barest impression in the old Baseball Encyclopedia: 19 games and 24 plate appearances spread across five weeks in the spring of 1951. But both before and after that short stint with the famously fated ’51 Giants, Wilson ranked for years as one of the biggest stars in two big-time leagues, and is forever remembered by big-time baseball fans in both the Deep South and the Pacific Northwest.

Artie Wilson’s career makes just the barest impression in the old Baseball Encyclopedia: 19 games and 24 plate appearances spread across five weeks in the spring of 1951. But both before and after that short stint with the famously fated ’51 Giants, Wilson ranked for years as one of the biggest stars in two big-time leagues, and is forever remembered by big-time baseball fans in both the Deep South and the Pacific Northwest.

Arthur Lee Wilson was born near Birmingham, Alabama, in the fall of 1920, just a couple of weeks after the Cleveland Indians finished off the Brooklyn Robins in the World Series.1 We don’t know much about Wilson’s childhood. By the late 1930s, though, he was working in a Birmingham factory. In 1939 he suffered an accident that might easily have cost him a sterling baseball career almost before it began. “I was cleaning up the machine shop,” Wilson later recalled. “I happened to be standing close by a machine and then a long piece of iron got hooked and was vibrating in the saw. I tried to grab it but I didn’t know what happened. I ran across to the warehouse station and I needed someone to turn off that machine. I didn’t know my thumb was [gone] until I pulled the glove off. I pulled out my thumb, which got caught up in that glove.”2

More than a half-century later, Wilson recalled using a golf ball as a rehab tool. “I carried that golf ball all the time,” he said in 1997. “My thumb got strong and I never missed it. The only thing was that when I threw, I had a natural sinker.”3

Wilson reportedly didn’t miss a single day of work. Or a baseball game, either. In those years, the Birmingham Black Barons played the area’s best baseball. But just a rung below was the Industrial League, with all-black teams representing local factories and steel mills. Before the 1944 season, Barons shortstop Piper Davis told the owner about an even better shortstop. Just a few months later, having signed with the Barons, Wilson earned a spot in the starting lineup for the Negro American League in the East-West All-Star Game, black baseball’s annual soiree held at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. He missed out in 1945 – Jackie Robinson got the spot instead – but was again the West’s starting shortstop from 1946 through ’48. In the latter season, Wilson was credited for many years with a .402 batting average in 76 games; today, some consider him the last .400 hitter in a “major” league (a claim only bolstered by further research showing him with a .428 average that season in approximately 40 official league games).

The story of how Wilson wound up as property of the New York Yankees has been told in different ways in different places, but Neil Lanctot’s version in Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution seems the most reliable.

In the winter after the ’48 season, the Yankees offered Black Barons owner Tom Hayes the going rate: 5,000forWilson’srights,withanother5,000 for Wilson’s rights, with another 5,000forWilson’srights,withanother5,000 if he was still with the Yankees in June. Hayes telegraphed his acceptance, but later reneged when Bill Veeck’s Indians offered more; Wilson, too, reportedly wasn’t thrilled about going to the Yankees and taking a significant pay cut from his Barons salary. So on the 9th or 10th of February, with Bill Veeck having flown to Puerto Rico for the occasion, Wilson signed a contract with the Indians. “Our scouts say he is the best prospect in the Negro Leagues today,” Veeck told reporters. “Better, even, than Larry Doby.”4

“I’ve hit major league pitching before,” Wilson said. “I think I can hit it again. … It’s going to be like going to school all over again. I know I have a lot – an awful lot – to learn. But again, I think I can do it.”5 After the ’46 season, Wilson had joined Satchel Paige’s All-Stars in a barnstorming tour around the Eastern half of the United States, with Bob Feller’s All-Stars providing the competition, and the black and white players mingled freely. “I talked with all of them,” Wilson told me in 2004. “Phil Rizzuto said, ‘If I had an arm like yours, I’d play for a hundred years. We went out there to beat ’em, the major leaguers. And they wanted to win. They didn’t want no black players beating them.”

The Yankees didn’t have any real interest in Wilson, but they certainly didn’t want Veeck to have him, either. Immediately after the news broke about Wilson’s new contract, general manager George Weiss issued a statement: “There are so many angles to this affair which must be studied, that the Yankees offer no comment at this time other than to say Cleveland has acted unethically if not in direct violation with baseball law.” For his part, Wilson said during spring training, “New York made me an offer. I didn’t accept it. Cleveland came along with another offer. I liked it. I accepted it and signed. That’s all there is to it.”

Ah, but the Yankees lodged a formal complaint. Meanwhile, Wilson reportedly enjoyed spring training with the Tribe. “They treated me like a king,” he said many years later. “I thought I could play shortstop until I came to that camp. I learned the most from [Joe] Gordon. He told me I had to learn to play the hitters, watch the catcher’s signals and take a step before the ball was hit.”6

However much he learned, Wilson had almost no chance of breaking into the Indians’ lineup. Not with manager Lou Boudreau manning shortstop, perennial All-Star Ken Keltner at third base, and future Hall of Famer Joe Gordon at second base. Before spring training ended, Wilson was optioned to the Indians’ farm club in the Pacific Coast League, leading Dan Daniel to write, “Wilson has been sent to San Diego, and never will make the major leagues. Not so long ago Veeck said he would not trade Wilson for Phil Rizzuto.”7

On May 13 the Office of the Commissioner handed down Decision No. 26, regarding the disposition of both Wilson and Luis Marquez (also the subject of a dispute between Veeck and Weiss). In what must have seemed a brilliant balancing act, Commissioner Albert “Happy” Chandler gave Marquez to the Indians and Wilson to the Yankees; more specifically, Wilson was “awarded to the Newark International League Club.”8

Wilson was immediately transferred from the San Diego club – with whom the Indians had a working relationship – in the Pacific Coast League to the Yankees’ Newark affiliate in the International League. But Wilson never went to Newark. Instead he stayed in the Pacific Coast League, thanks to a deal with the Oakland Oaks. Still in his prime, Wilson batted .348 overall and captured his second batting title in two years.

When Wilson arrived in Oakland, there weren’t any other black players and he was told he’d have to room alone. According to one story, Billy Martin said, “He’s got a roomie now. I’ll room with him.”9

“We were close,” Wilson said in 1993 about Martin. “We’d go hear music together, everything. And we stayed in touch.”10

But while Martin would soon join the Yankees, Wilson would not. First Boudreau had blocked Wilson, and now Rizzuto (plus the Yankees’ deeply held organizational prejudices). So 1950 was just more of the same, as Wilson batted .311 in 196 games with the Oaks. That May the New York Age, a black newspaper, reported that while the Yankees still owned Wilson’s rights, “Art would rather quit baseball than play with the Bombers who tried their best to get rid of him last year. … He’s on the Coast playing with the Oakland team and making a boatload of loot.”11

After the season, though, it looked as though Artie would finally get his shot in the majors, when the New York Giants acquired him from Oakland in a six-player, $125,000 deal. Asked for comment, Bobby Hofman, Wilson’s erstwhile double-play partner with the Oaks, allowed that Wilson was solid rather than flashy on the field. But off the field? “He collects those silly looking golf caps, all colors,” Hofman said. “He doesn’t play golf at all, he just wears the damn caps. Must have 40 of them, at least.” For his part, Wilson would admit owning only seven or eight: “I just like to wear ’em.”12

A couple of weeks before Opening Day, Giants manager Leo Durocher was asked to name the spring’s biggest development. His response: “This fellow Wilson. In my book he has been terrific and I don’t see how I’m going to keep him out of the lineup. He can play second, short, or third; he can play the outfield, and don’t be surprised if one of these days you see him on first base. A fellow who can field and hit the way he can is going to take somebody’s job, make no mistake about that.”13 He’d also reportedly claimed that only three National League shortstops – the Giants’ own Alvin Dark, along with Granny Hamner and Pee Wee Reese – could beat out Wilson in a fair match.14

As expected, though, Wilson opened the season on the Giants’ bench. His third game action – like the first two, as a pinch-hitter in a game the Giants were losing – came against the Dodgers, who just happened to be managed by Chuck Dressen, Wilson’s manager with Oakland in both 1949 and ’50. Dressen probably had seen Wilson play more games against tough competition than anyone else, and he trotted out that knowledge against the Giants, ordering what the New York World-Telegram’s Joe King described as “a shift which probably had never before been seen in the big leagues… shifting three of his infielders to the left side of second base, and pulling in his right fielder, Carl Furillo, to play second. He left right field wide open, undefended, and right field in Harlem roams 460 feet from the plate before it turns toward center.”15

Alas, Wilson couldn’t take advantage of the shift, tapping weakly to pitcher Don Newcombe. According to King, Dressen hadn’t invented the shift; “Lefty O’Doul of the San Francisco Seals had worked it on Wilson frequently,” and Wilson’s only home run in 1950 came when he hit the ball against the shift.

In fact, Wilson had been facing extreme shifts since early in his Organized Baseball career. Back in 1950, the following item appeared in Pacific Coast Baseball News:

“Li’l Artie has done more than expected of him since he joined the Oaks from the Padres. … His play at short has been so remarkable defensively the Oaks pace all other teams in double-plays. His scrappiness has earned him the admiration of his teammates, the respect of his foes. Yet, with his skills and years of experience, he still possesses the eagerness to learn and is often out during the day with skipper Charley Dressen trying to improve his fielding and hitting when a night game is slated. He’s the fire in the Oakland wheel that keeps it rolling so fast toward first place. And even the adoption of the ‘Williams’ shift hasn’t stopped his flurry of base-hits. The lad runs, hits, fields superbly –what more does one need to be the outstanding player of the year[?]”16

Wilson finally started a game on April 26, going 1-for-3 with a walk while spelling Eddie Stanky at second base. On May 6 he started at shortstop in the second game of a doubleheader, going 1-for-4. While he would get into 10 more games with the Giants, he wouldn’t start again. His last hit came on May 12 when he singled home Bobby Thomson in a losing effort against the Phillies. In the stands that afternoon: General Douglas MacArthur, dressed in mufti and attending his first major-league game since 1935.17

Back in 1948, Wilson’s last season with the Barons, one of his teammates was a 17-year-old outfielder named Willie Mays. In the spring of ’51, Mays was batting .477 for the Giants’ Minneapolis farm team. It was time. But with Mays coming up, somebody had to go down. It was Willie’s old Birmingham mentor.

Tommy Sampson, who played with and managed Wilson in Birmingham, attributed Wilson’s short stint in the majors to his extreme hitting style. “You know the reason why?” Sampson told interviewer Brent Kelley. “He couldn’t hit the ball to right field. That was his problem. You throw the ball and he’s gonna hit it to left field anyway, or he’s gonna hit it to shortstop. He was always running away from the plate; he hit running. That’s the reason why he didn’t stay up.”18

Meanwhile, Monte Irvin offered a couple of reasons for the demotion: “Although nobody wants to admit it,” Irvin wrote in his memoir, “there was an unwritten quota system at the time that limited the number of black players on a ballclub. But Durocher was going to send Artie down anyway because Leo thought it was simply outrageous that he couldn’t pull the ball. If he had been getting base hits, it might have been different. … Wilson had never pulled the ball before and couldn’t in the majors. …”19

Yes, keeping Wilson would have given the Giants five black players: Wilson, Mays, Thompson, Monte Irvin, and backup catcher Ray Noble. It’s been said that owner Horace Stoneham simply didn’t want more than four black players on the club. As a practical matter, most teams with black players preferred an even number, because it was felt, however ridiculously, that a black player must have a black roommate. And it was two per room.

Of course, it was also true that Wilson’s manager hadn’t found much use for him. When Mays was promoted, Wilson had started only two games, pinch-hit in 11 more, and collected just four hits (all singles) in 22 at-bats.

And as Wilson would later say, “Leo had two people that he could option out – Ray Noble or myself. But we already had an agreement that if he wasn’t going to play me, he was going to send me to Oakland’s minor-league affiliate in the Pacific Coast League because I can’t sit on the bench and just do nothing; I’ve got to play.”20

Initially the Giants sent Wilson to Ottawa in the International League. But after just a few days (and two games) with that club, he was shifted to Minneapolis. And after a few weeks there, it was back to Oakland. According to one source, Oaks owner Brick Laws called Giants owner Horace Stoneham and pleaded for Wilson, because otherwise the Oaks just wouldn’t draw any fans. Oakland’s fans presented a large floral arrangement upon Wilson’s return to the city, and the club drew more than 23,000 fans for his first three games. And after a doubleheader against the San Francisco Seals that season, manager Lefty O’Doul said, “You don’t see shortstop being played better by anybody than you saw it today. I spent a few years in the majors, but I never saw anything like the exhibition Wilson staged.”21

After the season the Cardinals and other National League clubs reportedly inquired with the Giants about acquiring second baseman Eddie Stanky to serve as player-manager. It says something about Artie Wilson’s declining stock that, in the event Stanky did leave, Wilson was merely listed among lesser lights Bob Hofman, Dave Williams, and Rudy Rufer as candidates to replace him in the Giants’ lineup.22 In the event, the Giants did trade Stanky to the Cardinals, and Williams took over at second base. In fact, just before Stanky was officially dispatched, the Giants sold Wilson to the Pacific Coast League’s Seattle Rainiers.23

Wilson’s stock had obviously fallen, not surprising considering his .255 batting average in 81 games with the Oaks. But with the Rainiers he rediscovered his batting stroke, topping .300 in each of his three seasons in Seattle. In ’53, Wilson became the Rainiers’ everyday second baseman, and would play mostly that position for the rest of his career. In 1955 he joined the PCL’s Portland Beavers, where one of his teammates was outfielder Ed Mickelson. In Mickelson’s memoir, he wrote,

“Artie kept us alive with his infectious, positive spirit, saying, ‘Never fear, Artie’s here!”

… Artie’s forte was a line drive over the third baseman’s head, just inside the left field line. Even though he was a left-handed hitter, the defense bunched him to the left, but he would still manage to drop the ball the opposite way, safely down the left field line for a base hit. …

“Artie, whom I guessed to be either a shade over or under 40, could still run, display an average arm, hit PCL pitching for over a .300 average and, perhaps most importantly, display a love and zest for the game that was unmatched by most. God! How I would have loved to have seen Artie Wilson play in his youth.”24

According to one source, Wilson became known in the Coast League as “the Birmingham Gentleman.”25 He returned to Seattle for most of 1956 and all of ’57, struggling in the latter season. Still only 36, Wilson seemed finished. But in 1962, after four seasons out of baseball, he made a brief and unsuccessful comeback, batting .186 over 39 games in the Class-A Northwest League and the Triple-A PCL (with Portland again). After which he really was finished in the game.

Very late in his life, Wilson’s youthful skills would be acknowledged once more. At a 2006 gala in Beverly Hills, Willie Mays honored his four living Birmingham Barons teammates: Bill Greason, Stephen Zapp, Sammy Williams, and Artie Wilson. “What they did for me,” Mays said before the dinner, “I’ll never forget. … I want to give them as much credit as I can.”26 A few months later, Wilson threw out the first pitch at a Yankees-Mariners game in Seattle. And around the same time, the ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia retroactively named Wilson the Negro American League’s Most Valuable Player in 1944.27

At times in his career, Wilson had been listed as 5-feet-11 and 170 or even 175 pounds. But late in his life he would say, “I never weighed 175 pounds. I weigh 162 pounds, what I’ve always weighed. And I’m only 5-feet-10.”28

On October 31, 2010, just three days after his 90th birthday, Artie Wilson died in Portland. Until nearly the end, Wilson had kept going to work at a Portland-area Ford dealership where he’d been employed for decades. “I can’t sit down,” he said in 1997. “There’s nothing to do at home.”29

He was survived by his wife, Dorothy, whom he’d wed back in 1949. They had two children, Zoe and Arthur Lee Wilson II. Known as Artie Jr., the latter starred in basketball at the University of Hawaii, and for some years worked in broadcasting and real estate. The elder Wilson also had a daughter from an earlier marriage, and departed with four grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.30

This biography appears in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III. It also appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin

Notes

1 His birthdate was October 28, 1920, and he was apparently born in Jefferson County, near Birmingham Alabama.

2 John Klima, Willie’s Boys: The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, the Last Negro League World Series, and the Making of a Baseball Legend (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2009), 37-38.

3 Bob Dolgan, “He could always hit,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 26, 1997.

4 Ed McAuley, “Indians sign Birmingham Negro shortstop,” Cleveland News, February 10, 1949.

5 Associated Press, “Gordon of Indians ends holdout for salary believed near $40,000,” New York Times, March 8, 1949.

6 Dolgan, “He could always hit.”

7 Dan Daniel, “Dan’s Dope,” New York World-Telegram, April 30, 1949.

8 Baseball, Office of the Commissioner, May 13, 1949.

9 Dolgan, “He could always hit.”

10 Filip Bondy, “Story of a different color,” New York Daily News, September 16, 1993.

11 New York Age, May 20, 1950.

12 Bill Roeder, “Wilson sets his cap on steady Giant duty,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, March 7, 1951.

13 John Drebinger, “Wilson, versatile Negro player, slated for regular Giant berth,” New York Times, April 3, 1951.

14 Bill Roeder, “Oakland supplies flag edge,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, March 26, 1951.

15 Joe King, “At least, Leo can’t call Chuck shiftless,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, April 21, 1951.

16 “Noren, Wilson clash for “rookie” honors with amazing play,” Pacific Coast Baseball News, September 10, 1949.

17 Louis Effrat, “Konstanty scores,” New York Times, May 13, 1951.

18 Brent Kelley, The Negro Leagues Revisited: Conversations with 66 More Baseball Heroes (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2000), 125.

19 James A. Riley and Monte Irvin, Nice Guys Finish First (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1996), 142-143.

20 Ross Forman, “Negro League great Artie Wilson profiled,” Sports Collectors Digest, January 29, 1993.

21 Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstandt, Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers, 1947-1959 (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1996), 68-69.

22 James P. Dawson, “Cards rebuffed in bid for Stanky,” New York Times, November 29, 1951.

23 John Drebinger, “Lanier and Diering slated for Giants,” New York Times, December 11, 1951.

24 Ed Mickelson, Out of the Park: Memoir of a Minor League Baseball All-Star (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2007), 168-169.

25 Matt Schudel, “Hit .400 in baseball’s Negro Leagues,” Washington Post, December 15, 2010.

26 USA Today, January 5, 2006.

27 Larry Blakely, “Last of the .400 hitters,” Chicago Sports Weekly, September 12, 2007.

28 Filip Bondy. “Story of a different color,” New York Daily News, September 16, 1993.

29 Dolgan, “He could always hit.”

30 Bruce Weber, “Artie Wilson, 90, shortstop who was mentor to Willie Mays,” New York Times, November 8, 2010.