Ben Chapman – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

More than anything, Ben Chapman is remembered these days for the vitriol he heaped on Jackie Robinson in April of Robinson’s first year in the majors. Chapman was the Phillies’ manager that day in 1947 and “decided to make Robinson’s color an issue and encouraged at least three of his men to do the same.”1 The verbal assault unnerved Robinson, but had the effect of bringing Robinson’s teammates more fully behind him. Dodgers GM Branch Rickey later said, “Chapman did more than anybody to unite the Dodgers. When he poured out that string of unconscionable abuse, he solidified and unified thirty men … Chapman made Jackie a real member of the Dodgers.”2

More than anything, Ben Chapman is remembered these days for the vitriol he heaped on Jackie Robinson in April of Robinson’s first year in the majors. Chapman was the Phillies’ manager that day in 1947 and “decided to make Robinson’s color an issue and encouraged at least three of his men to do the same.”1 The verbal assault unnerved Robinson, but had the effect of bringing Robinson’s teammates more fully behind him. Dodgers GM Branch Rickey later said, “Chapman did more than anybody to unite the Dodgers. When he poured out that string of unconscionable abuse, he solidified and unified thirty men … Chapman made Jackie a real member of the Dodgers.”2

Chapman was white, born in Nashville but raised in Alabama. Chapman attended Powell Elementary School in Birmingham and graduated from Phillips High School. His father, Harry, was a machinist at a steel plant at the time of the 1930 census, and his mother, Effie, a homemaker. William Benjamin Chapman (born on Christmas Day in 1908) was their only child. In the family home, they house four boarders at the time of the 1930 census – a plumber, a laundress, a grocery store clerk, and a clerk in a meat market.

Harry (Tub) Chapman was also a ballplayer in his day, as were two of Harry’s brothers, Jim and John. Each played for some time in the minor leagues, Harry for reportedly as long as 13 years.3 It was while his father was playing ball in Nashville that Ben was born. “My dad was a pitcher,” Ben told sportswriter F. C. Lane, “and was going pretty good. One day a Detroit Tiger scout came to look him over and dad was determined to make a good impression. He put everything he had on every pitch and tore a ligament in his arm. That was the end of his baseball career.”4

Ben had his first uniform at the age of 4, and later worked as a batboy for the Southern Association’s Birmingham Barons and was a four-letter athlete in high school.5 He played high-school baseball as a pitcher, until his father pressed him to play the infield instead. He played semipro ball for a cotton mill in Alabama, even overlapping with some of his high school ball, but not ruled to threaten his amateur status. In the semipro league, he hit for a .186 average – but he did ultimately marry the boss’s daughter, Miss Ola Sanford, who’d known in high school, in October 1935.6

He was a competitive player even in high school. Phillips High won the Alabama state championship in 1927, and Chapman pitched as well as played infield. He told the New York Post in April 1935 that he’d won the game against Warrior High, 32-2, and that earlier in the season he’d thrown a one-hitter while striking out 19. Part of the reason for his success was his competitiveness. “All a pitcher has to do in high school ball … is to throw the ball at the batter’s head and then feed him a wide curve on the outside for him to go fishing.” Asked if that’s how he engineered the one-hitter, he replied, “What do you think? I hit four batters.”7

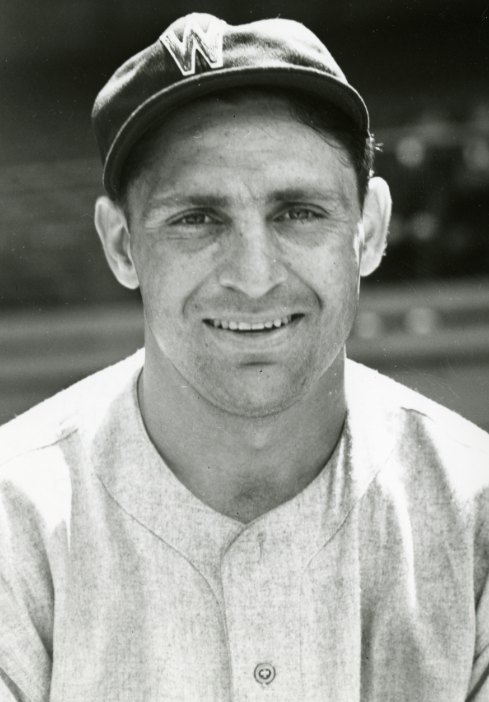

Chapman was offered a contract by a scout for the New York Yankees, but then it was his mother who stepped in and pushed for him to go to Purdue, where he had been offered a football scholarship.8 He did go to Purdue, but left after about a month to play professional baseball. Chapman was 6-feet tall and listed at 190 pounds.

Ben became a very good ballplayer, with a .302 lifetime average over the course of 15 major-league seasons and 1,717 games. Chapman was primarily an outfielder, though he played 153 games as an infielder (every position but first base), and he even pitched in 25 games – with a winning record at that.

He managed the Phillies for the latter half of 1945, all of 1946 and 1947, and the first half of 1948.

Chapman was initially signed by Johnny Nee of the Yankees, in 1927, while Ben was still a junior in high school. Being a minor at the time, his (quite likely proud) father had to sign the contract for him.9 The spring following his graduation in January 1928, the Yankees had him report to Asheville in the South Atlantic (SALLY) League. He appeared in 147 games, batting .336 with seven homers for the Class-B Tourists, who won the pennant with ease — by 18 games over the second-place Macon Peaches. Chapman was the shortstop on that year’s league All-Star team. He was clearly good on offense, but committed a league-leading 67 errors.

He bumped up to Double A in 1929, and hit for exactly the same average: .336, for the St. Paul Saints (American Association), but this time with 31 homers and 137 RBIs. He moved from shortstop to third base, but the penchant for errors continued; he chalked up 43 of them.

This was a ballplayer ready for the majors, though, and the Yankees brought him up in 1930. Even before spring training began, it was thought he would make the team. Manager Bob Shawkey announced Chapman as his third baseman six weeks before the season began. He played 91 games at third base and 45 games at second, and he hit 10 home runs contributing toward his .316 average. His average remained very consistent all year long. Playing with Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth in the same lineup no doubt helped. Chapman’s 24 errors at third base led the league; three leagues, three times he’d committed the most errors.

In his second year in the majors, Chapman was moved to the outfield, where his strong throwing arm and his speed could perhaps better be utilized. In part the move was because Earle Combs got injured, but it was a position for which he was better suited. Manager Joe McCarthy explained: “He didn’t get the ball away quickly enough for an infielder and lost too many double plays. He had a full arm action instead of a snap throw. This was an asset in the outfield but a handicap in the infield. There wasn’t any question that he belonged in the outfield.”10

He played 137 games (with only 11, all at second base, in the infield.) He played left field primarily but a substantial number in right field, too. His average held steady, dipping just one point – to .315. His homers jumped from ten to 17, and where he had driven in 81 runs in 1930, he drove in 122 in 1931. Only five American Leaguers drove in more.

Chapman was fast on the basepaths, too. He led the league with 61 stolen bases in 1931, the first of four years he led in thefts, including three years in a row: 1931, 1932, and 1933. (It should be noted that he also led the league all three years in times caught stealing, too.) Both in 1928 and 1929, he’d also led the league in stolen bases in the minors, with 30 stolen bases and 26, respectively. Dubbed the “Dixie Flyer” and the “Alabama Flash,” there were a few times when he competed against other players in pregame sprints on the field. In 1931, the Christian Science Monitor reported that Chapman had run 100 yards in 10.5 seconds, on grass at Comiskey Park.11

His 1932 saw him again surpass 100 RBIs and 100 runs scored (107 and 101, respectively), tailing off just a bit in batting average, too, to .299. Though he topped 100 runs scored four more times, the closest he came to driving in 100 was in 1933, when he fell two short (98). In 1933 and 1934, his average climbed back over .300.

The year 1933 was the first of four years in a row when Chapman was voted an All-Star (he couldn’t have been earlier, because 1933 was the first year that Major League Baseball held an All-Star Game.) Batting leadoff, he was the first American League player ever to bat in an All-Star Game. He grounded out. In the game, he was 1-for-5, a bunt single to third base.

Chapman’s only appearance in a World Series came in 1932 (from 1929 through 1935, it was the only year the Yankees won the pennant.) His outfield play presented some interesting moments; working center field in 1935, he led the American League again in errors (15) but also in outfield assists (25).

There was a very remarkable play in which Chapman was involved, on July 26, 1935. He was on second base when Jesse Hill hit a hard line drive off Senators pitcher Ed Linke. The ball ricocheted off Linke’s forehead and came back on the fly to catcher Jack Redmond, who caught it for an out – then fired over the fallen Linke and doubled Chapman off the bag at second.12

The Yankees finished in first place again in 1936, but Chapman was no longer with the team after midseason. He’d caught a really bad cold in early May and never quite got right. He was traded to Washington on June 14, 1936, for Jake Powell, another player who goes down in history as a racist and ne’er-do-well.13 In part, the Yanks were making way for an up-and-coming center fielder: Joe DiMaggio. Chapman was called the Yankees’ “biggest disappointment” that year. The trade was said to be a case of “giving up Chapman’s defensive ability for a heftier hitter.”14 One could say that Chapman was moved twice—once by the Yankees to make room for DiMaggio, and once a very few years later to make room on the Red Sox for Ted Williams.

Chapman wore a Senators uniform when he played in the 1936 All-Star Game. He was 2-for-8 (a single in 1933 and a triple in 1934) in All-Star action.

In the World Series, Chapman hit .294 (5-for-17, with six RBIs). He drove in the sixth and tenth of New York’s 12 runs in their 12-6 win over the Chicago Cubs in Game One, and the two winning runs in the third inning of the 4-2 Game Two. Chapman drove in one run in Game Three and another in Game Four, driving in at least one run in each of the four games as the Yankees swept the Cubs in the Series.

Chapman’s average over the seven seasons in which he appeared for the Yankees was .305. He was with Washington for two season halves – the second half of 1936 and the first half of 1937. On June 11, 1937, just a few days short of the anniversary of his arrival in D.C., he was traded by the Senators (along with Bobo Newsom) to the Boston Red Sox for Mel Almada and the two Ferrell brothers, pitcher Wes and catcher Rick. It was kind of a trade of temperamental titans, with Chapman, Wes Ferrell, and Newsom all ranking among some of the top contenders for that honor in baseball history. He’d appeared in 132 games for the Senators and been remarkably consistent with his batting average — .300.

The Red Sox found a very productive right fielder; Chapman hit .324 in his two seasons with Boston. He had hit .307 in the second part of 1937, but in 1938, with a full season playing for the Red Sox, he hit .340, with 80 RBIs and 92 runs scored. One might think that the last thing a team would do was let a 29-year-old batter with that sort of production go—but on December 15, 1938, he was traded to the Cleveland Indians for Denny Galehouse and Tommy Irwin. Boston believed they had a replacement waiting in the wings, a player who had won the Triple Crown in the American Association that year playing for the Minneapolis Millers—Ted Williams.

(Mark Armour repeated a story from Ed Linn that “Cronin had to play Chapman because he was afraid of the damage to team morale if he was left on the bench with the other players.” There is also the possibility that he’d paved the way for dismissal when he had “purposely ignored a bunt sign and became engaged in a fist fight with manager Joe Cronin.”15)

The Indians were glad to get him, though there was some thought he might be traded on to St. Louis to help secure a second baseman, the team’s greatest need. That didn’t happen, and Chapman performed well for manager Ossie Vitt and the Indians in 1939. His average was .290, but he had a .390 on-base percentage. More importantly, he drove in 82 runs, third most on the club, and he led the team in runs scored with 101. He felt he could have been more productive but for the huge outfield in League Park. “I figure I lost at least 20 hits” compared to playing in Fenway Park.16 He did tie a major-league record with three triples in one game, on July 3, but oddly that was in the relatively small Briggs Stadium in Detroit.

There was a dropoff in 1940. Though he played only six fewer games (143 in 1940), his RBI total dropped to 50 and his runs scored to 82 – though his average was almost the same and his OBP wasn’t off by much. During the course of the season, he experimented with wearing eyeglasses.17 The Indians scored less than 90% of the runs they’d scored in 1939, but much of Chapman’s decline was his own. This was the year of the notorious player mutiny against manager Vitt, the players later dubbed the “Crybabies” because of their complaints against their skipper. Chapman was said to be one of the ringleaders. It may have paved the way for his departure from Cleveland. He later expressed regret for his involvement, telling Vitt, “I don’t know what got into us. It was all so silly.”18

Chapman was with three ballclubs in the next six months. The day before Christmas in 1940, the Indians traded him to the Washington Senators for left-handed pitcher Joe Krakauskas. In his second stint working for the Senators, he played in 28 early-season games, mostly in left field, but was only hitting .255 and had only knocked in ten runs. The Senators were well-enough set with outfielders, and they simply released him on May 26, 1941. Chapman was heard to say it was to get out from under his high $12,000 salary.19

Three days later, he signed as a free agent with the Chicago White Sox. He got a chance to play, appearing in 57 games, but he only hit .226 with them and he was unconditionally released on November 3.

The _Cleveland Plain Dealer_’s Gordon Cobbledick offered a postscript to his time in the majors (not knowing he’d be back), calling him a “man of many moods” and saying that when he was with New York, he wanted to go to Boston to take advantage of the left-field wall. He talked about hitting left-handed. If he was batting leadoff, he talked about batting third. He was always looking for greener grass. The Yankees, Cobbledick wrote, simply gave up on him. He suggested maybe the National League would be a good place for him, because “They don’t know him so well over there.”20

It was back to the minor leagues again in 1942, as player/manager for the Richmond Colts in the Piedmont League. He played in 118 games and hit .324 but with very little power – only three home runs. He played 62 games at third base, did some pinch hitting, but also worked on something new – pitching. (He felt himself capable of playing many positions, and proved he could. He’d even talked about trying batting left-handed, as far back as 1934.) Chapman worked in 16 games and posted a 6-3 record with an excellent 1.71 earned run average in 95 innings of work. He was considered a member of that year’s All-Star team (per Tom Ferguson of the Virginian-Pilot) and was so popular that the team held a Ben Chapman Night in August.21

Chapman would have played for Richmond in 1943, too, but for his fiery temper. In baseball, it’s frowned upon when a player or manager hits an umpire. In the final game of the playoff series against Portsmouth, on September 16, Chapman was called out at first base by umpire I. H. Case. Fellow umpire James B. Clegg, working that game behind the plate, told The Sporting News what transpired. “As he prolonged the argument, I walked out from my plate position just as Case ordered Chapman from the field. ‘Chapman said, ‘If you say I’m out of the game, I’m going to let you have it.’ Case then said, ‘You’re out.’ Chapman swung and struck umpire Case in the face, whereupon Lazzeri ran out and grabbed Chapman. A policeman quickly appeared and escorted Ben from the field.”22 The league suspended Chapman from Organized Baseball for a full year.

It wasn’t the first time he had struck an umpire, but when it had happened in the majors, he was only suspended for three days. On July 11, 1937, he threw his glove at umpire John Quinn and struck him square on the right shoulder. He was ejected and lucky not to have been more seriously penalized.23

As a manager, Chapman was perhaps even more competitive than he had been as a player. Dan Albaugh said he used to berate his own players a lot—the very reason the Indians had mutinied against Vitt—and that he fought constantly with umpires, a favorite tactic being to “give the men in blue a Nazi salute.”24

It wasn’t the first time Chapman had become involved in an incident. Years earlier, he’d gotten into an extended feud with teammate Babe Ruth when he essentially called out the aging Ruth as, essentially, over the hill. There had been another occasion during his Yankees days when he had exchanged heated verbal barbs with a fan in the stand and then, once the final out was recorded, “the infuriated Chapman leaped over the barrier into the stands and cased the frightened fan clear into the street.”25

There was a fight in Washington on April 25, 1933, where Chapman charged into the Senators dugout and attacked pitcher Earl Whitehill (incidentally, one of the players to whom Chapman had attended in 1923, when Chapman was a batboy for Birmingham Barons and Whitehill a pitcher for the team.) The incident had been prompted by Chapman’s spiking of second baseman Buddy Myer. It was Myer who threw the first punch, but it was the second day in a row Chapman had spiked him—the foot which was not on the bag. Other players became involved, and a number of fans, too, three of whom were arrested. Chapman, Myer, and Whitehill were all suspended for a few days. Chapman said he was “playing the game.”26

On another occasion (May 5, 1938), when Tigers catcher Birdie Tebbetts ragged on Chapman for being called out on a third strike, Chapman knocked him down. It was the “first fistic outbreak” at Fenway since 1920. He was suspended three days and fined when he was playing in Philadelphia and was called out on a play by umpire John Quinn. “A few moments later [Chapman] scooped up an Athletics drive and did his best to hit Quinn in the head with the throw.”27

Chapman served his suspension for all of 1943. He owned a bowling alley in Montgomery, and played some semipro ball there.28 He worked in the offseason teaching prep school football and basketball, doing some officiating in both sports as well. Chapman refereed for years in college basketball’s Southeastern Conference.29 He also coached the Birmingham Steelers basketball team, of the Southern Professional Basketball League, until December 1948.

Chapman was classified 1-A for the World War II draft, and was called for a physical; he received two letters in the mail on February 24, 1944. One contained his contract as manager for Richmond, and the other directed him to report for induction on March 1.30 But the war was coming to an end, and he had a trick knee. Ultimately, he was declared 4-F and was never inducted into military service.

He was hired by Richmond again for 1944, and Chapman combined three jobs once more – pitching, playing outfield, and managing. He hit .303 in 57 games, pitching in 21 of them and recording 13 wins against only six defeats. His ERA for ’44 was 2.21. In early August, he was brought up to the Brooklyn Dodgers (traded by Richmond for Clyde King and some cash) and appeared in 20 big-league games, ten in August and ten in September. He hit for a .368 average in 44 plate appearances with 11 runs scored and 11 RBIs. Interestingly, he never once played either infield or outfield for the 1944 Dodgers. He debuted as a pitcher and won his first game, a start against the visiting Boston Braves, working a complete game 9-4 win. Chapman pitched in 11 games and was 5-3 with a 3.40 ERA. He threw two back-to-back complete game victories on August 30 (10-2) and September 4 (4-1), the first a four-hitter and the second a three-hitter. In the other nine games, he pinch hit.

In 1945 he began the year with Brooklyn, and worked three games in April, five in May, and two in June – reflecting his role as a pitcher. He was hitting for a .136 average in 24 plate appearances, with a 3-3 mark as a moundsman (with a 5.53 ERA), until he was traded to the Phillies for catcher Johnny Peacock on June 15.

He threw seven innings for the Phillies in 1945 and 1 1/3 in 1946, without any decisions either year and with a combined 6.48 ERA. He only appeared in one game in 1946, the May 12 game. On June 11, the Phillies released him.

But that was deceiving. They released him as a player. He remained the manager. Chapman had taken over as Phillies manager after 69 games in 1945 (Freddie Fitzsimmons had the team 18-51 at that point, and it’s not surprising there was a change made. It was reported that Fitzsimmons resigned.) Chapman’s first game as manager was June 30, 15 days after arriving in the Peacock trade. His first edict, supposedly, was to tell everyone on the team that if they so much as mentioned last place, they would be sent forthwith to the minors.31 The 1945 Phils (they were actually known as the Blue Jays in 1944 and 1945) were 28-57 under Chapman, but still finished in last place. In August, after a five-game winning streak, Chapman was hired on a one-year contract for 1946.

In 1946, Chapman said his team was the best-trained team in the majors and he predicted they would surprise. GM Herb Pennock said of Chapman, “Ben has gotten the Phils over their last place complex, and from here on in we’re moving.”32 He was still a fiery personality, ejected four times in 1946. The formerly Futile Phils moved up to fifth place (69-85), and they set new attendance records, more than doubling any previous attendance in franchise history save for the 1916 team (and they were only several thousand short of doubling that mark.) In 1945, they’d drawn 285,057 but it 1946 they drew 1,045,247. It was a good move of Chapman’s to have asked for a bonus clause for attendance in his contract, for any totals exceeding 400,000. He reportedly made more ($15,000) through the bonus than his $12,500 salary.33

In 1947 — the year in which Chapman taunted Jackie Robinson so viciously — they dropped back to eighth place and attendance dipped to 907,332, still well over the 400,000 bonus threshold.

Bench jockeying was an established practice in baseball, the intent often being to get under the skin of opposing players. At the time, it wasn’t uncommon to bring up opponent’s ethnicity, but Chapman went well over the line more than once — and he had a history of it. He remembered the way he’d been taunted when he first came up. “The first words I remember hearing when I was a rookie with the Yankees were, ‘Hey, you redneck so-and-so, go back to Alabama where you belong.”34

Even before the incidents with Robinson, Chapman had spoken about the “spiritual value of holler guys.”35 Chapman had often traded insults with opposing players; in 1935, the Washington Post reported on a game where he relentlessly rode Senators pitcher Buck Newsom throughout.36

He clearly crossed over the line, though. In 1934, something like 15,000 New Yorkers signed a petition asking the Yankees to get rid of Chapman because of his anti-Semitic remarks.37

Before the 1936 season, he had said, “The first thing I want to do is make my peace with the Jewish fans at the Stadium. I understand that some of them have signed a petition asking that I be traded. I had a little trouble with a couple of Jewish spectators in 1934, but last year I took plenty of riding without ever making a return. What is behind this opposition to me I do now know. In Birmingham I have a host of Jewish friends. I play baseball and basketball at the Y.M.H.A.”38

In 1942, when managing in Richmond, he had one of his players, Julio Acosta, teach him “the correct slang to holler at Charlotte’s Gil Torres to get his goat.”39

As to Robinson, Dodgers traveling secretary Harold Parrott wrote “Chapman mentioned everything from thick lips to the supposedly extra-thick Negro skull, which he said restricted brain growth to almost animal level when compared to white folk. He listed the repulsive sores and diseases he said Robbie’s teammates would be infected with if they touched the towels or combs he used. He charged Jackie outright with breaking up his own Brooklyn team. The Dodger players had told him privately, he said, that they wished that the black man would go back into the South where he belonged, picking cotton, swabbing out latrines, or worse.”40 Commissioner of Baseball Happy Chandler had to intercede and demand that Chapman stop.

So did National League president Ford Frick. They didn’t waste any time. They realized the P.R. problem. Nationally syndicated columnist Walter Winchell asked the question in print: “If the baseball player insults the ump he can be thrown out of the game. Why, then, can’t bigoted ball players (who insult Americans) be thrown out of baseball?”41

As early as May 8, Frick had already made it clear: “I told Ben and the Philadelphia club that such language was not becoming from any National League bench and I warned them not to do it any more. They agreed to abide by my directive.”42 Chapman and Robinson were asked to pose for a photograph together, to try and counter the negative publicity. It had to be very uncomfortable for both, but they did it. The photo ran in many papers on May 12. Dodgers officials said they took Chapman at his word that he knew he had erred, and believed he was sincere.43 Robinson himself, wrote about the photo shoot at the time in the African American newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier. He said, “I was glad to cooperate and when we got over to the Phillies’ dugout, Chapman came out to shake my hand. We said hello to each other and he smiled when the picture was snapped. Chapman impressed me as a nice fellow and I don’t really think he meant the things he was shouting at me the first time we played Philadelphia.”44

A remarkable column by Dan Burley ran in the New York Amsterdam News, another black paper, talking about how “prior to 1947, such riding was confined to the racial distinctions whites make among themselves. Thus, Italian players got it in the neck as did Irish and the few Jews who are in the majors. In other words, ballplayers played the ‘dozens’ and made an art of it.”45 Indeed, Italian players were subjected to the “w” word almost as a matter of course, Irish players were called “Micks” and so forth. The difference in white players riding black players was seen right away by Frick and Chandler, and many others, and a halt was put to it.

Years later, Chapman still bridled at the memory of bearing the brunt of the charge of racism. He said, “I’m no bigot. I believe that every man, be he black, or white or whatever, is entitled to equal opportunity. The pigment of a man’s skin is God’s doing.”46 He also said, “I had already managed five black players. People have told me that was the reason I was fired at Philadelphia. I don’t believe that… I remember three black writers coming into my office in Philadelphia. They wanted to ask me some questions. I told them I wanted to ask them … questions first. ‘Do you want this guy to make the big leagues like all the other guys did? Do you want him treated like all the other players?’ They said that’s what they wanted. That’s the way they wrote it, that I was treating Jackie like Gehrig was treated, like Dixie was treated. That’s the way it should have been.”47 At the time he had said, “Robinson is just another ballplayer to us… We’ll ride anybody if it’ll help us win.”48

Chapman suffered a strained back on July 7, and was treated at the hospital and released after the train the team was on collided with an engine. Mrs. Chapman was kept at the hospital in Chicago, treated for shock.

He was the first of three Phillies managers in 1948, gone a little more than halfway through the season (37-42). The team was in seventh place at the time. Did he resign, or was he fired? It depends on who one asked. The newspaper headlines all said he was dismissed, and quoted owner Bob Carpenter as saying he had informed Chapman it was time for a change. There was some suggestion that it was a mutual decision, or that Chapman had chosen to leave, but Chapman told the Associated Press, “You can say I never quit in my life… I wish Mr. Carpenter would tell the public his real reason for my dismissal.”49 He denied it was because Carpenter wanted to hire some Negro players. “I don’t know if he had his eye on any or not. But if he hired them I would have managed them.”50 There were stories that the team was thinking of hiring Goose Tatum. But if the Phillies were thinking of integrating, it took them almost ten years to get there – John Kennedy on April 22, 1957.

For several years, stories ran from time to time that Chapman had never been told why he was fired. In 1953, Frederick Lieb and Stan Baumgartner’s book The Philadelphia Phillies suggested that he was fired “as a way of showing that he (Carpenter) was taking charge of the front office following the death of Herb Pennock.”51

Chapman both purchased and managed the Class-B Gadsden Chiefs in the Southeastern League in 1949, back home in Alabama.52 The team finished in last place, with a 39-95 record. In 1950, he worked as manager of the Danville Leafs in the Class B Carolina League. The team finished in second place.

He managed the Tampa Smokers (Class B Florida International League) in 1951, and managed them to first place in league standings with a 90-50 record, though they lost to Miami in the first round of the playoffs.

Chapman’s last involvement in baseball was as a coach for the Cincinnati Reds in 1952, though he resigned on August 1 when he learned that incoming manager Rogers Hornsby himself planned to work the third-base coaching box. He was named a scout for the team, but in 1953 he returned to manage Tampa. He resigned near the end of July. He signed on as a coach for Toronto’s team in the International League, apparently believing he was in line to become manager. That did not happen, and he turned to full-time work selling insurance.

In 1966, Chapman was one of the four charter inductees into Richmond’s baseball Hall of Fame. Into his late 70s, Chapman coached on weekends at Samford University in Birmingham.53

Around 1992, a year or so before he died, Chapman told author Ray Robinson, speaking of Jackie Robinson (the two Robinsons were not related): “A man learns about things and mellows as he grows older. I think that maybe I’ve changed a bit. Maybe I went too far in those days. But I always went along with the bench jockeying, which has always been part of the game. Maybe I was rougher at it than some players. I thought that you could use it to upset and weaken the other team. It might give you an advantage.” He then paused, and added, “The world changes. Maybe I’ve changed, too. Look, I’m real proud that I’ve raised my son different.” His son Bill, he said, was coaching football and there were some black players on the team. “And he gets along well with them. They like him. That’s a nice thing, don’t you think?”54 Bill Chapman had also signed a contract to pitch in the Cincinnati Reds organization, and appeared in 27 games for Tampa in 1962 and 1963.

Ben Chapman died, apparently of a heart attack, at home in Hoover, Alabama, on July 7, 1993. He was survived by his wife, Ola, and two sons, William and Robert.

So urces

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Chapman’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson (New York: Ballantine Books, 1997), 172.

2 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made (New York: Fawcett, 1974), 74.

3 Collie Small, “The Terrible-Tempered Mr. Chapman,” The Saturday Evening Post, April 5, 1947, and F. C. Lane, “That Meteor of the Base Paths – Ben Chapman,” Baseball Magazine, February 1932.

4 Lane, op. cit.

5 The Cleveland Plain Dealer of January 4, 1931 provides details of Chapman’s work as a batboy for the Barons.

6 This was his second marriage, in October 1935. An earlier July 1931 marriage to Mary Elizabeth Payne ended in divorce about two years later. See the New York Times, May 11, 1933 for Payne’s filing for separate maintenance. She charged that Chapman had gone off with the Yankees, leaving her with only $2.87. The couple reconciled later that fall, but both agreed to divorce in 1934.

7 New York Post, datelined April 11, 1935.

8 Details of Chapman’s childhood come from the Small and Lane articles mentioned above.

9 John Drohan, May 1930 clipping in Chapman’s Hall of Fame player file. Drohan wrote for the Boston Traveler. See also the Richmond Times Dispatch, December 21, 1943. A few years later, after Chapman had made himself a star in the majors, scout “Pop” Shaw sued the Yankees for $42,000, claiming he was the one who had signed Chapman off the Birmingham sandlots. He lost his case on September 2, 1932. See the Greensboro Daily Record of September 3.

10 New York World-Telegram, May 15, 1941.

11 Christian Science Monitor, August 26, 1931.

12 The story ran in Bob Considine’s national column, printed in (among other newspapers) the February 10, 1944 Augusta Chronicle.

13 Powell was suspended once when he said he enjoyed working as a policeman in the offseason and “beating niggers over the head.” See, for instance, Dan Albaugh’s article, “Ben Chapman: Jackie Robinson’s worst nightmare,” Sports Collectors Digest, September 26, 1997.

14 Seattle Daily Times, June 15, 1936.

15 Mark Armour, Joe Cronin: A Life in Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), 101. The fist fight was mention by Albaugh, ibid., but not by Cronin biographer Armour.

16 Unidentified partial newspaper clipping in Chapman’s Hall of Fame player file.

17 See, for instance, the Washington Post, June 25, 1940.

18 The Sporting News, March 6, 1964.

19 Baton Rouge State Times Advocate, May 29, 1941. See also the May 27 Washington Post.

20 Cleveland Plain Dealer,

21 Richmond Times-Dispatch, July 22, 1942 is the source of the All-Star mention.

22 The Sporting News, July 12, 1980.

23 Boston Globe, July 12, 1937.

24 Albaugh, op. cit., 147.

25 Collie Small, op. cit., 154.

26 Washington Post, April 26, 1933.

27 Ibidem.

28 Greensboro Record, August 16, 1943.

29 Unidentified newspaper clipping from August 4, 1944, found in Chapman’s Hall of Fame player file.

30 Boston Globe, February 24, 1944.

31 Collie Small, op. cit., 154.

32 New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 25, 1946.

33 The Oregonian, April 21, 1947.

34 Unattributed news clipping found in Chapman’s Hall of Fame player file.

35 The phrase was Collie Small’s. See Small, op. cit., 154.

36 Washington Post, July 8, 1935.

37 Albaugh, 146.

38 New York World-Telegram, April 7, 1936.

39 Washington Post, August 4, 1942.

40 Harold Parrott, The Lords of Baseball (Taylor Trade Publishing, 2002), quoted in Albaugh, 147.

41 Richmond Times Dispatch, May 15, 1947.

42 Boston Traveler, May 9, 1947.

43 See Walter Winchell’s column in, for instance, the Richmond Times Dispatch of June 27, 1947.

44 Pittsburgh Courier, May 17, 1947. Fifty years later, excerpts from Robinson’s columns were printed in the 1997 New Pittsburgh Courier.

45 New York Amsterdam News, June 28, 1947.

46 New Orleans Times-Picayune, February 23, 1955.

47 Unattributed news clipping found in Chapman’s Hall of Fame player file.

48 Washington Post, May 4, 1947.

49 Unattributed news clipping datelined July 17, 1948 found in Chapman’s Hall of Fame player file.

50 Unattributed news clipping found in Chapman’s Hall of Fame player file.

51 Richmond Times Dispatch, April 29, 1953.

52 New York Times, November 25, 1948.

53 Marietta Journal, April 17, 1986.

54 New York Times, May 19, 2013, 8.