1.4. Support Vector Machines (original) (raw)

Support vector machines (SVMs) are a set of supervised learning methods used for classification,regression and outliers detection.

The advantages of support vector machines are:

- Effective in high dimensional spaces.

- Still effective in cases where number of dimensions is greater than the number of samples.

- Uses a subset of training points in the decision function (called support vectors), so it is also memory efficient.

- Versatile: different Kernel functions can be specified for the decision function. Common kernels are provided, but it is also possible to specify custom kernels.

The disadvantages of support vector machines include:

- If the number of features is much greater than the number of samples, avoid over-fitting in choosing Kernel functions and regularization term is crucial.

- SVMs do not directly provide probability estimates, these are calculated using an expensive five-fold cross-validation (see Scores and probabilities, below).

The support vector machines in scikit-learn support both dense (numpy.ndarray and convertible to that by numpy.asarray) and sparse (any scipy.sparse) sample vectors as input. However, to use an SVM to make predictions for sparse data, it must have been fit on such data. For optimal performance, use C-ordered numpy.ndarray (dense) orscipy.sparse.csr_matrix (sparse) with dtype=float64.

1.4.1. Classification#

SVC, NuSVC and LinearSVC are classes capable of performing binary and multi-class classification on a dataset.

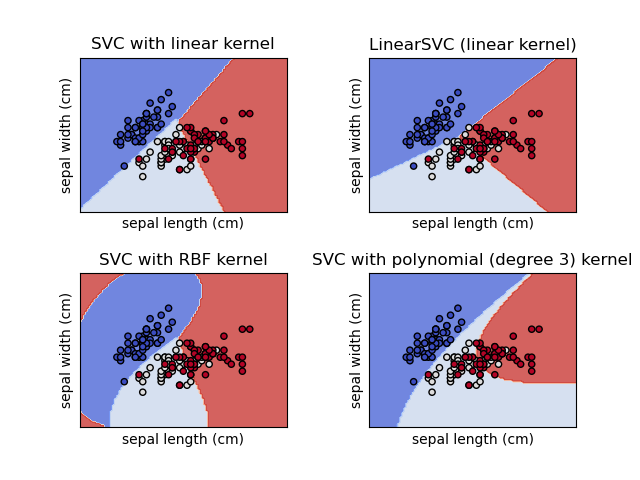

SVC and NuSVC are similar methods, but accept slightly different sets of parameters and have different mathematical formulations (see section Mathematical formulation). On the other hand,LinearSVC is another (faster) implementation of Support Vector Classification for the case of a linear kernel. It also lacks some of the attributes of SVC and NuSVC, likesupport_. LinearSVC uses squared_hinge loss and due to its implementation in liblinear it also regularizes the intercept, if considered. This effect can however be reduced by carefully fine tuning itsintercept_scaling parameter, which allows the intercept term to have a different regularization behavior compared to the other features. The classification results and score can therefore differ from the other two classifiers.

As other classifiers, SVC, NuSVC andLinearSVC take as input two arrays: an array X of shape(n_samples, n_features) holding the training samples, and an array y of class labels (strings or integers), of shape (n_samples):

from sklearn import svm X = [[0, 0], [1, 1]] y = [0, 1] clf = svm.SVC() clf.fit(X, y) SVC()

After being fitted, the model can then be used to predict new values:

clf.predict([[2., 2.]]) array([1])

SVMs decision function (detailed in the Mathematical formulation) depends on some subset of the training data, called the support vectors. Some properties of these support vectors can be found in attributessupport_vectors_, support_ and n_support_:

get support vectors

clf.support_vectors_ array([[0., 0.], [1., 1.]])

get indices of support vectors

clf.support_ array([0, 1]...)

get number of support vectors for each class

clf.n_support_ array([1, 1]...)

Examples

- SVM: Maximum margin separating hyperplane

- SVM-Anova: SVM with univariate feature selection

- Plot classification probability

1.4.1.1. Multi-class classification#

SVC and NuSVC implement the “one-versus-one” (“ovo”) approach for multi-class classification, which constructsn_classes * (n_classes - 1) / 2classifiers, each trained on data from two classes. Internally, the solver always uses this “ovo” strategy to train the models. However, by default, thedecision_function_shape parameter is set to "ovr" (“one-vs-rest”), to have a consistent interface with other classifiers by monotonically transforming the “ovo” decision function into an “ovr” decision function of shape (n_samples, n_classes).

X = [[0], [1], [2], [3]] Y = [0, 1, 2, 3] clf = svm.SVC(decision_function_shape='ovo') clf.fit(X, Y) SVC(decision_function_shape='ovo') dec = clf.decision_function([[1]]) dec.shape[1] # 6 classes: 4*3/2 = 6 6 clf.decision_function_shape = "ovr" dec = clf.decision_function([[1]]) dec.shape[1] # 4 classes 4

On the other hand, LinearSVC implements a “one-vs-rest” (“ovr”) multi-class strategy, thus training n_classes models.

lin_clf = svm.LinearSVC() lin_clf.fit(X, Y) LinearSVC() dec = lin_clf.decision_function([[1]]) dec.shape[1] 4

See Mathematical formulation for a complete description of the decision function.

Note that the LinearSVC also implements an alternative multi-class strategy, the so-called multi-class SVM formulated by Crammer and Singer[16], by using the option multi_class='crammer_singer'. In practice, one-vs-rest classification is usually preferred, since the results are mostly similar, but the runtime is significantly less.

For “one-vs-rest” LinearSVC the attributes coef_ and intercept_have the shape (n_classes, n_features) and (n_classes,) respectively. Each row of the coefficients corresponds to one of the n_classes“one-vs-rest” classifiers and similar for the intercepts, in the order of the “one” class.

In the case of “one-vs-one” SVC and NuSVC, the layout of the attributes is a little more involved. In the case of a linear kernel, the attributes coef_ and intercept_ have the shape(n_classes * (n_classes - 1) / 2, n_features) and (n_classes * (n_classes - 1) / 2) respectively. This is similar to the layout forLinearSVC described above, with each row now corresponding to a binary classifier. The order for classes 0 to n is “0 vs 1”, “0 vs 2” , … “0 vs n”, “1 vs 2”, “1 vs 3”, “1 vs n”, . . . “n-1 vs n”.

The shape of dual_coef_ is (n_classes-1, n_SV) with a somewhat hard to grasp layout. The columns correspond to the support vectors involved in any of the n_classes * (n_classes - 1) / 2 “one-vs-one” classifiers. Each support vector v has a dual coefficient in each of then_classes - 1 classifiers comparing the class of v against another class. Note that some, but not all, of these dual coefficients, may be zero. The n_classes - 1 entries in each column are these dual coefficients, ordered by the opposing class.

This might be clearer with an example: consider a three class problem with class 0 having three support vectors\(v^{0}_0, v^{1}_0, v^{2}_0\) and class 1 and 2 having two support vectors\(v^{0}_1, v^{1}_1\) and \(v^{0}_2, v^{1}_2\) respectively. For each support vector \(v^{j}_i\), there are two dual coefficients. Let’s call the coefficient of support vector \(v^{j}_i\) in the classifier between classes \(i\) and \(k\) \(\alpha^{j}_{i,k}\). Then dual_coef_ looks like this:

Examples

1.4.1.2. Scores and probabilities#

The decision_function method of SVC and NuSVC gives per-class scores for each sample (or a single score per sample in the binary case). When the constructor option probability is set to True, class membership probability estimates (from the methods predict_proba andpredict_log_proba) are enabled. In the binary case, the probabilities are calibrated using Platt scaling [9]: logistic regression on the SVM’s scores, fit by an additional cross-validation on the training data. In the multiclass case, this is extended as per [10].

The cross-validation involved in Platt scaling is an expensive operation for large datasets. In addition, the probability estimates may be inconsistent with the scores:

- the “argmax” of the scores may not be the argmax of the probabilities

- in binary classification, a sample may be labeled by

predictas belonging to the positive class even if the output ofpredict_probais less than 0.5; and similarly, it could be labeled as negative even if the output ofpredict_probais more than 0.5.

Platt’s method is also known to have theoretical issues. If confidence scores are required, but these do not have to be probabilities, then it is advisable to set probability=Falseand use decision_function instead of predict_proba.

Please note that when decision_function_shape='ovr' and n_classes > 2, unlike decision_function, the predict method does not try to break ties by default. You can set break_ties=True for the output of predict to be the same as np.argmax(clf.decision_function(...), axis=1), otherwise the first class among the tied classes will always be returned; but have in mind that it comes with a computational cost. SeeSVM Tie Breaking Example for an example on tie breaking.

1.4.1.3. Unbalanced problems#

In problems where it is desired to give more importance to certain classes or certain individual samples, the parameters class_weight andsample_weight can be used.

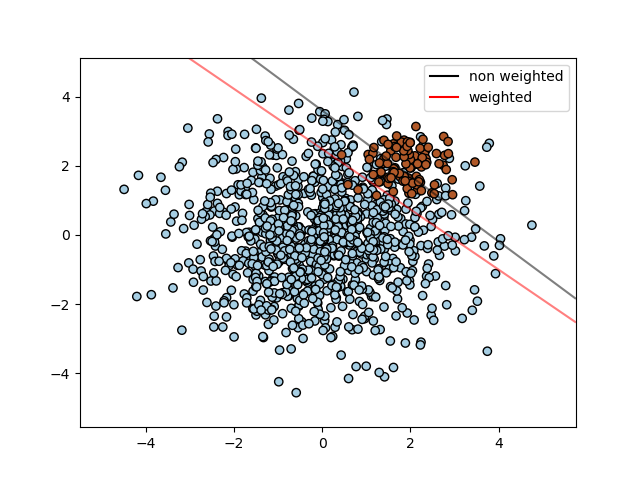

SVC (but not NuSVC) implements the parameterclass_weight in the fit method. It’s a dictionary of the form{class_label : value}, where value is a floating point number > 0 that sets the parameter C of class class_label to C * value. The figure below illustrates the decision boundary of an unbalanced problem, with and without weight correction.

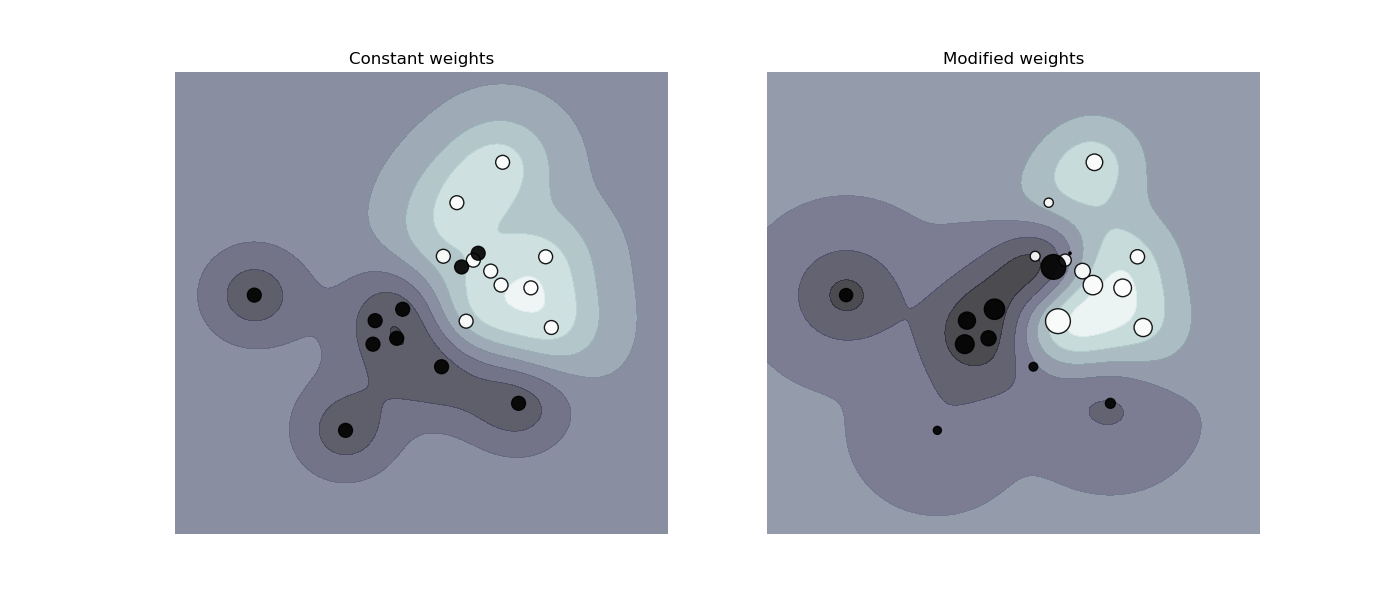

SVC, NuSVC, SVR, NuSVR, LinearSVC,LinearSVR and OneClassSVM implement also weights for individual samples in the fit method through the sample_weight parameter. Similar to class_weight, this sets the parameter C for the i-th example to C * sample_weight[i], which will encourage the classifier to get these samples right. The figure below illustrates the effect of sample weighting on the decision boundary. The size of the circles is proportional to the sample weights:

Examples

1.4.2. Regression#

The method of Support Vector Classification can be extended to solve regression problems. This method is called Support Vector Regression.

The model produced by support vector classification (as described above) depends only on a subset of the training data, because the cost function for building the model does not care about training points that lie beyond the margin. Analogously, the model produced by Support Vector Regression depends only on a subset of the training data, because the cost function ignores samples whose prediction is close to their target.

There are three different implementations of Support Vector Regression:SVR, NuSVR and LinearSVR. LinearSVRprovides a faster implementation than SVR but only considers the linear kernel, while NuSVR implements a slightly different formulation than SVR and LinearSVR. Due to its implementation inliblinear LinearSVR also regularizes the intercept, if considered. This effect can however be reduced by carefully fine tuning itsintercept_scaling parameter, which allows the intercept term to have a different regularization behavior compared to the other features. The classification results and score can therefore differ from the other two classifiers. See Implementation details for further details.

As with classification classes, the fit method will take as argument vectors X, y, only that in this case y is expected to have floating point values instead of integer values:

from sklearn import svm X = [[0, 0], [2, 2]] y = [0.5, 2.5] regr = svm.SVR() regr.fit(X, y) SVR() regr.predict([[1, 1]]) array([1.5])

Examples

1.4.3. Density estimation, novelty detection#

The class OneClassSVM implements a One-Class SVM which is used in outlier detection.

See Novelty and Outlier Detection for the description and usage of OneClassSVM.

1.4.4. Complexity#

Support Vector Machines are powerful tools, but their compute and storage requirements increase rapidly with the number of training vectors. The core of an SVM is a quadratic programming problem (QP), separating support vectors from the rest of the training data. The QP solver used by the libsvm-based implementation scales between\(O(n_{features} \times n_{samples}^2)\) and\(O(n_{features} \times n_{samples}^3)\) depending on how efficiently the libsvm cache is used in practice (dataset dependent). If the data is very sparse \(n_{features}\) should be replaced by the average number of non-zero features in a sample vector.

For the linear case, the algorithm used inLinearSVC by the liblinear implementation is much more efficient than its libsvm-based SVC counterpart and can scale almost linearly to millions of samples and/or features.

1.4.5. Tips on Practical Use#

- Avoiding data copy: For SVC, SVR, NuSVC andNuSVR, if the data passed to certain methods is not C-ordered contiguous and double precision, it will be copied before calling the underlying C implementation. You can check whether a given numpy array is C-contiguous by inspecting its

flagsattribute.

For LinearSVC (and LogisticRegression) any input passed as a numpy array will be copied and converted to the liblinear internal sparse data representation (double precision floats and int32 indices of non-zero components). If you want to fit a large-scale linear classifier without copying a dense numpy C-contiguous double precision array as input, we suggest to use the SGDClassifier class instead. The objective function can be configured to be almost the same as the LinearSVCmodel. - Kernel cache size: For SVC, SVR, NuSVC andNuSVR, the size of the kernel cache has a strong impact on run times for larger problems. If you have enough RAM available, it is recommended to set

cache_sizeto a higher value than the default of 200(MB), such as 500(MB) or 1000(MB). - Setting C:

Cis1by default and it’s a reasonable default choice. If you have a lot of noisy observations you should decrease it: decreasing C corresponds to more regularization.

LinearSVC and LinearSVR are less sensitive toCwhen it becomes large, and prediction results stop improving after a certain threshold. Meanwhile, largerCvalues will take more time to train, sometimes up to 10 times longer, as shown in [11]. - Support Vector Machine algorithms are not scale invariant, so it is highly recommended to scale your data. For example, scale each attribute on the input vector X to [0,1] or [-1,+1], or standardize it to have mean 0 and variance 1. Note that the same scaling must be applied to the test vector to obtain meaningful results. This can be done easily by using a Pipeline:

from sklearn.pipeline import make_pipeline

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.svm import SVC

clf = make_pipeline(StandardScaler(), SVC())

See section Preprocessing data for more details on scaling and normalization. - Regarding the

shrinkingparameter, quoting [12]: We found that if the number of iterations is large, then shrinking can shorten the training time. However, if we loosely solve the optimization problem (e.g., by using a large stopping tolerance), the code without using shrinking may be much faster - Parameter

nuin NuSVC/OneClassSVM/NuSVRapproximates the fraction of training errors and support vectors. - In SVC, if the data is unbalanced (e.g. many positive and few negative), set

class_weight='balanced'and/or try different penalty parametersC. - Randomness of the underlying implementations: The underlying implementations of SVC and NuSVC use a random number generator only to shuffle the data for probability estimation (when

probabilityis set toTrue). This randomness can be controlled with therandom_stateparameter. Ifprobabilityis set toFalsethese estimators are not random andrandom_statehas no effect on the results. The underlying OneClassSVM implementation is similar to the ones of SVC and NuSVC. As no probability estimation is provided for OneClassSVM, it is not random.

The underlying LinearSVC implementation uses a random number generator to select features when fitting the model with a dual coordinate descent (i.e. whendualis set toTrue). It is thus not uncommon to have slightly different results for the same input data. If that happens, try with a smallertolparameter. This randomness can also be controlled with therandom_stateparameter. Whendualis set toFalsethe underlying implementation of LinearSVC is not random andrandom_statehas no effect on the results. - Using L1 penalization as provided by

LinearSVC(penalty='l1', dual=False)yields a sparse solution, i.e. only a subset of feature weights is different from zero and contribute to the decision function. IncreasingCyields a more complex model (more features are selected). TheCvalue that yields a “null” model (all weights equal to zero) can be calculated using l1_min_c.

1.4.6. Kernel functions#

The kernel function can be any of the following:

- linear: \(\langle x, x'\rangle\).

- polynomial: \((\gamma \langle x, x'\rangle + r)^d\), where\(d\) is specified by parameter

degree, \(r\) bycoef0. - rbf: \(\exp(-\gamma \|x-x'\|^2)\), where \(\gamma\) is specified by parameter

gamma, must be greater than 0. - sigmoid \(\tanh(\gamma \langle x,x'\rangle + r)\), where \(r\) is specified by

coef0.

Different kernels are specified by the kernel parameter:

linear_svc = svm.SVC(kernel='linear') linear_svc.kernel 'linear' rbf_svc = svm.SVC(kernel='rbf') rbf_svc.kernel 'rbf'

See also Kernel Approximation for a solution to use RBF kernels that is much faster and more scalable.

1.4.6.1. Parameters of the RBF Kernel#

When training an SVM with the Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel, two parameters must be considered: C and gamma. The parameter C, common to all SVM kernels, trades off misclassification of training examples against simplicity of the decision surface. A low C makes the decision surface smooth, while a high C aims at classifying all training examples correctly. gamma defines how much influence a single training example has. The larger gamma is, the closer other examples must be to be affected.

Proper choice of C and gamma is critical to the SVM’s performance. One is advised to use GridSearchCV withC and gamma spaced exponentially far apart to choose good values.

Examples

1.4.6.2. Custom Kernels#

You can define your own kernels by either giving the kernel as a python function or by precomputing the Gram matrix.

Classifiers with custom kernels behave the same way as any other classifiers, except that:

- Field

support_vectors_is now empty, only indices of support vectors are stored insupport_ - A reference (and not a copy) of the first argument in the

fit()method is stored for future reference. If that array changes between the use offit()andpredict()you will have unexpected results.

You can use your own defined kernels by passing a function to thekernel parameter.

Your kernel must take as arguments two matrices of shape(n_samples_1, n_features), (n_samples_2, n_features)and return a kernel matrix of shape (n_samples_1, n_samples_2).

The following code defines a linear kernel and creates a classifier instance that will use that kernel:

import numpy as np from sklearn import svm def my_kernel(X, Y): ... return np.dot(X, Y.T) ... clf = svm.SVC(kernel=my_kernel)

You can pass pre-computed kernels by using the kernel='precomputed'option. You should then pass Gram matrix instead of X to the fit andpredict methods. The kernel values between all training vectors and the test vectors must be provided:

import numpy as np from sklearn.datasets import make_classification from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split from sklearn import svm X, y = make_classification(n_samples=10, random_state=0) X_train , X_test , y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, random_state=0) clf = svm.SVC(kernel='precomputed')

linear kernel computation

gram_train = np.dot(X_train, X_train.T) clf.fit(gram_train, y_train) SVC(kernel='precomputed')

predict on training examples

gram_test = np.dot(X_test, X_train.T) clf.predict(gram_test) array([0, 1, 0])

Examples

1.4.7. Mathematical formulation#

A support vector machine constructs a hyper-plane or set of hyper-planes in a high or infinite dimensional space, which can be used for classification, regression or other tasks. Intuitively, a good separation is achieved by the hyper-plane that has the largest distance to the nearest training data points of any class (so-called functional margin), since in general the larger the margin the lower the generalization error of the classifier. The figure below shows the decision function for a linearly separable problem, with three samples on the margin boundaries, called “support vectors”:

In general, when the problem isn’t linearly separable, the support vectors are the samples within the margin boundaries.

We recommend [13] and [14] as good references for the theory and practicalities of SVMs.

1.4.7.1. SVC#

Given training vectors \(x_i \in \mathbb{R}^p\), i=1,…, n, in two classes, and a vector \(y \in \{1, -1\}^n\), our goal is to find \(w \in \mathbb{R}^p\) and \(b \in \mathbb{R}\) such that the prediction given by\(\text{sign} (w^T\phi(x) + b)\) is correct for most samples.

SVC solves the following primal problem:

\[ \begin{align}\begin{aligned}\min_ {w, b, \zeta} \frac{1}{2} w^T w + C \sum_{i=1}^{n} \zeta_i\\\begin{split}\textrm {subject to } & y_i (w^T \phi (x_i) + b) \geq 1 - \zeta_i,\\ & \zeta_i \geq 0, i=1, ..., n\end{split}\end{aligned}\end{align} \]

Intuitively, we’re trying to maximize the margin (by minimizing\(||w||^2 = w^Tw\)), while incurring a penalty when a sample is misclassified or within the margin boundary. Ideally, the value \(y_i (w^T \phi (x_i) + b)\) would be \(\geq 1\) for all samples, which indicates a perfect prediction. But problems are usually not always perfectly separable with a hyperplane, so we allow some samples to be at a distance \(\zeta_i\) from their correct margin boundary. The penalty term C controls the strength of this penalty, and as a result, acts as an inverse regularization parameter (see note below).

The dual problem to the primal is

\[ \begin{align}\begin{aligned}\min_{\alpha} \frac{1}{2} \alpha^T Q \alpha - e^T \alpha\\\begin{split} \textrm {subject to } & y^T \alpha = 0\\ & 0 \leq \alpha_i \leq C, i=1, ..., n\end{split}\end{aligned}\end{align} \]

where \(e\) is the vector of all ones, and \(Q\) is an \(n\) by \(n\) positive semidefinite matrix,\(Q_{ij} \equiv y_i y_j K(x_i, x_j)\), where \(K(x_i, x_j) = \phi (x_i)^T \phi (x_j)\)is the kernel. The terms \(\alpha_i\) are called the dual coefficients, and they are upper-bounded by \(C\). This dual representation highlights the fact that training vectors are implicitly mapped into a higher (maybe infinite) dimensional space by the function \(\phi\): see kernel trick.

Once the optimization problem is solved, the output ofdecision_function for a given sample \(x\) becomes:

\[\sum_{i\in SV} y_i \alpha_i K(x_i, x) + b,\]

and the predicted class corresponds to its sign. We only need to sum over the support vectors (i.e. the samples that lie within the margin) because the dual coefficients \(\alpha_i\) are zero for the other samples.

These parameters can be accessed through the attributes dual_coef_which holds the product \(y_i \alpha_i\), support_vectors_ which holds the support vectors, and intercept_ which holds the independent term \(b\).

Note

While SVM models derived from libsvm and liblinear use C as regularization parameter, most other estimators use alpha. The exact equivalence between the amount of regularization of two models depends on the exact objective function optimized by the model. For example, when the estimator used is Ridge regression, the relation between them is given as \(C = \frac{1}{\alpha}\).

The primal problem can be equivalently formulated as

\[\min_ {w, b} \frac{1}{2} w^T w + C \sum_{i=1}^{n}\max(0, 1 - y_i (w^T \phi(x_i) + b)),\]

where we make use of the hinge loss. This is the form that is directly optimized by LinearSVC, but unlike the dual form, this one does not involve inner products between samples, so the famous kernel trick cannot be applied. This is why only the linear kernel is supported byLinearSVC (\(\phi\) is the identity function).

The \(\nu\)-SVC formulation [15] is a reparameterization of the\(C\)-SVC and therefore mathematically equivalent.

We introduce a new parameter \(\nu\) (instead of \(C\)) which controls the number of support vectors and margin errors:\(\nu \in (0, 1]\) is an upper bound on the fraction of margin errors and a lower bound of the fraction of support vectors. A margin error corresponds to a sample that lies on the wrong side of its margin boundary: it is either misclassified, or it is correctly classified but does not lie beyond the margin.

1.4.7.2. SVR#

Given training vectors \(x_i \in \mathbb{R}^p\), i=1,…, n, and a vector \(y \in \mathbb{R}^n\) \(\varepsilon\)-SVR solves the following primal problem:

\[ \begin{align}\begin{aligned}\min_ {w, b, \zeta, \zeta^*} \frac{1}{2} w^T w + C \sum_{i=1}^{n} (\zeta_i + \zeta_i^*)\\\begin{split}\textrm {subject to } & y_i - w^T \phi (x_i) - b \leq \varepsilon + \zeta_i,\\ & w^T \phi (x_i) + b - y_i \leq \varepsilon + \zeta_i^*,\\ & \zeta_i, \zeta_i^* \geq 0, i=1, ..., n\end{split}\end{aligned}\end{align} \]

Here, we are penalizing samples whose prediction is at least \(\varepsilon\)away from their true target. These samples penalize the objective by\(\zeta_i\) or \(\zeta_i^*\), depending on whether their predictions lie above or below the \(\varepsilon\) tube.

The dual problem is

\[ \begin{align}\begin{aligned}\min_{\alpha, \alpha^*} \frac{1}{2} (\alpha - \alpha^*)^T Q (\alpha - \alpha^*) + \varepsilon e^T (\alpha + \alpha^*) - y^T (\alpha - \alpha^*)\\\begin{split} \textrm {subject to } & e^T (\alpha - \alpha^*) = 0\\ & 0 \leq \alpha_i, \alpha_i^* \leq C, i=1, ..., n\end{split}\end{aligned}\end{align} \]

where \(e\) is the vector of all ones,\(Q\) is an \(n\) by \(n\) positive semidefinite matrix,\(Q_{ij} \equiv K(x_i, x_j) = \phi (x_i)^T \phi (x_j)\)is the kernel. Here training vectors are implicitly mapped into a higher (maybe infinite) dimensional space by the function \(\phi\).

The prediction is:

\[\sum_{i \in SV}(\alpha_i - \alpha_i^*) K(x_i, x) + b\]

These parameters can be accessed through the attributes dual_coef_which holds the difference \(\alpha_i - \alpha_i^*\), support_vectors_ which holds the support vectors, and intercept_ which holds the independent term \(b\)

The primal problem can be equivalently formulated as

\[\min_ {w, b} \frac{1}{2} w^T w + C \sum_{i=1}^{n}\max(0, |y_i - (w^T \phi(x_i) + b)| - \varepsilon),\]

where we make use of the epsilon-insensitive loss, i.e. errors of less than\(\varepsilon\) are ignored. This is the form that is directly optimized by LinearSVR.

1.4.8. Implementation details#

Internally, we use libsvm [12] and liblinear [11] to handle all computations. These libraries are wrapped using C and Cython. For a description of the implementation and details of the algorithms used, please refer to their respective papers.

References