THEORIZING MEMES (original) (raw)

THEORIZING MEMES

Sanjoop K P

Abstract

The paper studies the contemporary phenomenon of Internet Memes focusing on two aspects: aa. to historicise the concept of memes-tracing the evolution of the term, and bb. to develop a model of meme analysis in the Indian context. The meaning and interpretation of an idea change based on the knowledge domain within which it is analysed. Memes have a history of usage tied to both evolutionary biology and internet-mediated communications. The paper documents these shifts in meaning, identifies certain limitations of theorizing memes based on western academia and provides an alternative model for analysing image-macro memes. It proposes that memes occupy the world of collaborative creation and they must be analysed under the larger lens of participatory media culture.

Keywords: digital culture, language, memetic, Meme frame, premise

The Origin of Memes

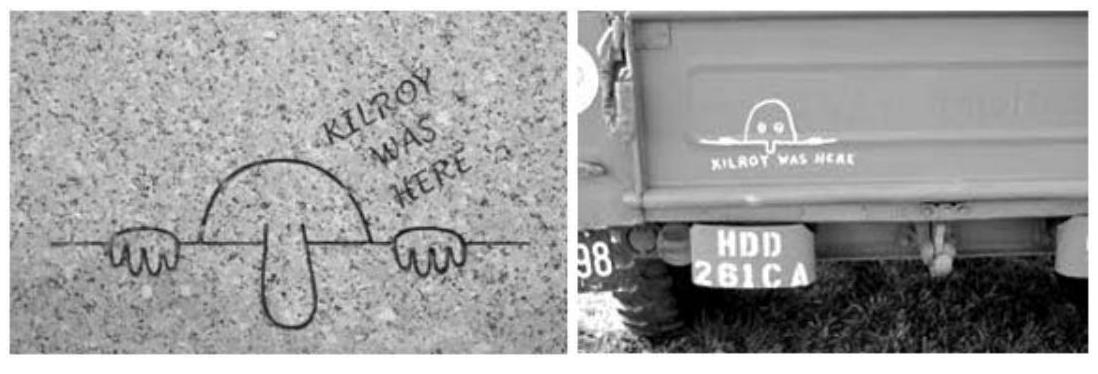

Memes in the contemporary sense were not born with internet. There are several examples of memes that predate the era of Internet. A classic example is -“Kilroy meme”. Launched during World War II, this meme incorporated a simple drawing of a man with a long nose looking over a wall, alongside a mysterious caption: “Kilroy Was Here” (Fig:1).

Fig. 1.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kilroy\_was\_here

- Mr Sanjoop K P, Research Scholar, Department of English, Mangalore University. ↩︎

Though its origins are still a matter of debate, the most accepted version of its history, according to Daniel Gilmore, links it to a Massachusetts shipyard inspector named James J Kilroy (Shifman, 2014). Kilroy’s job was to examine riveters’ work after they completed their shifts. To keep track of his inspections, he began marking inspected areas with the phrase “Kilroy Was Here.” When the ships were ready for launch, soldiers noticed these scribblings all over the ship. Kilroy was everywhere! At some point in the meme’s journey, caricature of a little man with a huge nose was added to it. After the war, Kilroy was reincarnated in urban graffiti, as well as in various pop-culture artefacts. (Fig: 2). The meme gained popularity in the American context and outside the country. As Limor Shifman observes, “the slogan’s meaning was mysterious and open to interpretation was an advantage, as it allowed each person to endow it with his or her own preferred meaning” (p. 24). The success of the meme depended upon its ease of imitation, its open-ended nature and the historical context that produced it. Moreover, the ability to understand and disseminate or generate new meanings out of the meme allowed membership of a community with a shared social capital of producing and understanding the cultural/political meanings of the meme. Its popularity tells us that people strived to replicate the meme, to join a community of Kilroy writers.

Defining a Meme

Meme is a blanket term, that includes a range of internet activities. Memes are “postmodern folklore” (Shifman, 2014, p. 15) in which shared norms and values are constructed through cultural artefacts such as photoshopped images, animated GIFS, edited/remixed videos, and unconventional language models. They can be “widely shared catchphrases, auto-tuned songs, manipulated stock photos, or recordings of physical performances” (Milner, 2016, p. 2). They can take the form of pictures captioned on Reddit, puns hash tagged on Twitter, and videos mashed up on YouTube. Memes typify the internet ecosystem which is characterised by replication, remixing, repetition, re-appropriation, variation, and imitation, among other things. Instead of developing a uniform framework for defining and theorizing memes, it is important to undertake a culture specific approach towards the study of memes. Throughout this paper, the term “Meme” is used in the sense that it was defined by Richard Dawkins 1{ }^{1} who originally coined the term. Based on his understanding of the information exchange among genes he developed a systematic model to understand the ‘propagation’ of memes.

Every culture produces its own memes that circulate within the community of meme users and meme producers. Slogans, caricatures, jokes, folk elements, fashions become memetic through constant and subtly varying replications transmitted by a community of users. Richard Dawkins, in The Selfish Gene (1976) observes that memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense can be called imitation. Dawkins identified three key elements of a successful genetic variant: copy-fidelity, fecundity, and longevity. In relation to memes, copy-fidelity is the ability to replicate accurately; fecundity is its speed of replication; and longevity its stability over time. Certain memes he said, will be more successful than others because they fulfil a cultural need or are uniquely suited to a specific circumstance (Marwick, 2013). The stylized portrait of Che Guevara that fills the visual ecosystem of Kerala is one such example (Fig 3&3 \& 4). Apart from being a protest symbol of the ‘left’ in Kerala, its appearance on t-shirts, slippers, umbrellas, abandoned building walls, denotes its prolific and prolonged participation in the popular culture of Kerala. The memetic sign undergoes repeated modifications in the process of its transmission and repeated use in multiple contexts. Though, memes as modes of communication existed prior to the internet era, the digital media enabled a mammoth increase in its spread and the speed at which they could be produced and reproduced.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Source: Scroll.in (photo credit: Praveen Jose)

Dawkinsian Meme and the Internet Meme

The earliest use of the term ‘meme’ was in the context of evolutionary biology. Richard Dawkins describes it as, “small units of culture that spread from person to person by copying or imitation”(Shifman, 2014). He tried to apply evolutionary theory to cultural change and this metaphor runs throughout the discussion of the term. He originally proposed the term as a cultural corollary to the gene. A ‘meme,’ is “an idea that functions in a mind the same way a gene or virus functions in the body. And an infectious idea (call it a “viral meme”) may leap from mind to mind, much as viruses leap from body to body”(Godwin, 1994). Like genes, memes are replicators that undergo variation, competition, selection, and retention. He imagined a meme as a spreadable idea, like its biological counterpart-the gene. According to Dawkins, memes are ideas which infect language and thought, replicating themselves within the minds and languages of individuals for the sole purpose of replication. Some of the examples of Dawkinsian memes are slogans, catch phrases, fashions, learned skills, and so on (Wiggins, 2019, p. 2).

Scholarship on memes has historically relied on this kind of an epidemiological model and has its limitations. Memes behave very differently from genes and reducing culture to biology would simplify complex human behaviours. According to Shifman, it is “not necessary to think of biology when analysing internet memes. The ideas of replication, and adaptation, can be analysed from a purely sociocultural perspective” (p. 12). Henry Jenkins and his colleagues rightfully assert that the gene-meme 2{ }^{2} metaphor is used in a problematic way, by conceptualizing people as helpless and passive creatures. The depiction of people as active agents is essential for understanding internet memes, particularly when the meaning of the meme is dramatically altered in the course of a meme’s journey. The Dawkinsian approach also ignores the discursive aspect of internet meme. Dawkins’ definition of meme elaborates on the movement of thoughts and concepts from brain to brain in the form of imitation, but it fails to relate to the complex and multifaceted ways in which content is created, spread, and represented online (Wiggins, 2019, p. 8). However, the greatest drawback of this kind of a formulation of the transmission of memes lies in its failure to recognize human agency and choice, in the construction, curation and consumption of the internet meme. According to Dawkins, memes replicate and mutate by random

chance, in a Darwinian fashion. But internet memes are created and altered by human creativity. Instead of trying to understand the complex tapestry of cultural communication through a simplistic theory of viral spread, it may be better to depart from Dawkins’ epidemiological argument and situate meme studies in the larger context of participatory media culture.

Mike Godwin (1994) adopted Dawkins’ idea of meme and placed it in the context of participatory media. Prior to Godwin’s essay 3{ }^{3}, the meaning of the word meme was limited to Dawkins’ definition of the term. Godwin used the term meme in the context of internet mediated communications to elucidate on what he calls “the Nazi comparison meme”. This refers to a recurring pattern of behaviour among the participants on internet platforms to derogatorily compare other participants to Nazis, during an argument. In Godwin’s words, “the labelling of posters or their ideas as “similar to the Nazis” or “Hitler-like” was a recurrent and often predictable event”. Nazi comparison was a “rhetoric hammer”, that somehow came handy for the (net dwellers) participants in online chats. Godwin identified this mode of behaviour in several forums and wanted to theorize this phenomenon. He argues there are obvious topics in which the comparison recurs. In discussions about guns and the Second Amendment, for example, gun-control advocates are periodically reminded that Hitler banned personal weapons. And birth-control debates are frequently marked by prolifers’ insistence that abortionists are engaging in mass murder, worse than that of Nazi death camps. And in any newsgroup in which censorship is discussed, someone inevitably raises the spectre of Nazi book-burning. (paras.1-3)

Nazi comparison memes, became a device for othering online participants who were considered as ideological opponents during online discussions on particular topics.

Memes and Virals

It is essential to differentiate Memes from its closest ally ‘Virals’, before moving any further. Virals are those internet pieces which could spread quickly to a wide range of users. Often, they are a single cultural unit (such as a video, photo, or joke) that circulates in many copies. An internet message becomes viral when it is actively forwarded from one person to other, “resulting in a rapid increase in the number of people who are exposed to the message” (Hemsley & Mason, 2010, pp. 138-176).

Shifman in her book argues that, a single video or image-macro meme is not an internet meme but part of a meme - “each individual meme is one manifestation of a group of texts that together can be described as the meme” (Shifman, 2014, p. 56). Simply put, some virals are born and buried as virals whereas others evolve to be memetic. In other words, memes thrive on intertextual references, and every newly created meme intertextually refers to other memes, sociopolitical events and other cultural artefacts like movies, advertisements etc. According to Shifman, if a single photo, video, or a physical performance triggers the creation of memes and if we are able to collect all the derivatives, then the corpus of all the collected memes can be called a meme. This is what Shifman calls the derivatives of a digital text. A viral content alone cannot become a meme until it enables the production of other digital texts. However, Shifman’s analysis has certain limitations. For instance, Shifman’s analysis presupposes the existence of an original viral image or videos which trigger derivatives. But most of the time, it is impossible to trace a specific video or photo that might have triggered several imitations or variations. Without meme repositories like ‘know your Meme,’ it will be difficult to label some memes as derivatives of a specific viral video or photo. Another consequence of Shifman’s formulation is that, grouping memes based on a single viral content would gloss over the problem of re-encontextualization of the internet meme. Varis and Blommaert (2014) argue “sharing” in Facebook is a classic example of re-encontexualizing. Reencontextualization refers to the

process by means of which a piece of “text” is extracted from its original context- of-use and re-inserted into an entirely different one, involving different participation frameworks, a different kind of textuality. (pp.7-8)

Hence, every sharing creates a different set of derivatives, making this process an unending one. Shifman partially address this issue when she discusses the concept of “stance”. She identifies three dimensions of cultural items that people can easily imitate when creating a meme: content, form, and stance (pp. 39-41). By stance, she means “the ways in which addressers position themselves in relation to the text, its linguistic codes, the addressees, and other potential speakers.”

Unpacking Image-macro Meme

This section will provide a model of meme analysis in the vernacular context of Kerala. Photographic memes with overlaid texts are referred to as image-macro memes. An Image-macro meme is a photographic image on which a caption, catchphrase or a dialogue is digitally superimposed. They combine the visual and the written text to communicate a desired message and evoke a particular response. Meme comprehension requires the knowledge of three basic components of an image-macro meme: 1. Meme-frame 2. Language 3. The Premise of the meme.

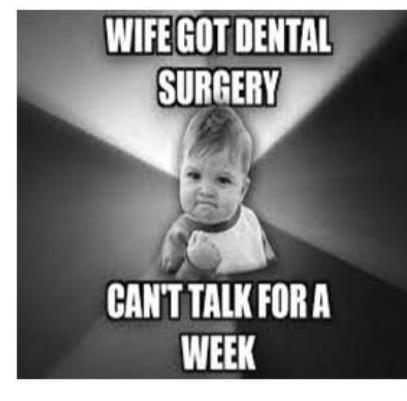

A meme-frame is the visual template into which a meme message is packed. It is also known as a plain meme or blank meme. As the term suggests, memeframe provides the visual frame work of the meme into which a desired message can be inserted. The creation of a meme-frame demands the aid of editing tools. The simplest form of a meme-frame is one that is self-explanatory. Such memeframes partially deliver the message through the body language or a particular facial expression of the character presented. Fig 5 depicts one such example; The Success Kid. The Success Kid is an Internet meme featuring a baby clenching a fistful of sand with a determined facial expression. It began in 2007 and eventually became known as “Success Kid”. Meme-frames like this are edited and remixed to communicate a new idea (Fig 6). This kind of a meme-frame does not require a knowledge of region or culture specific set of references.

Fig 5

Fig 6

Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Success\_Kid https://in.pinterest.com/printmeme/success-kid-memes/

A complex form of the meme-frame would include culture specific references in it. Complex meme-frame demands the knowledge of cultural texts like cinema, soaps, advertisements, music albums, news on politics etc. An example for the complex form of the meme-frame would be one in which the frame is taken from a very popular movie which is familiar to a linguistically specific audience (Fig 7 & 8).

Fig 7

When friends have seen your ‘Salary is credited’ message and it’s Friday evening

Fig 8

Figure 7: https://www.memezero.com/movie/In\\ Harihar\ Nagar/

Fig 7 is a famous scene from the movie In Harihar Nagar, featuring the iconic villain John Honai, who terrorizes one of the characters and tries to snatch a briefcase filled with cash from her. Fig 8 is memetic reference to this scene in the movie in order to convey a new and different message. Since, this movie scene sets up the template of the meme, meme comprehension presupposes the viewers’ knowledge of the movie and the meaning of this iconic scene. In the context of the Malayalam speaking public of Kerala comic blockbusters (movies like In Harihar Nagar, Punjabi House, Chitram, Minnaram, etc) and super-hits of Mammootty, Mohanlal and Suresh Gopi (The King, The Commissioner, Narasimham) etc, have inspired a large number of meme-frames.

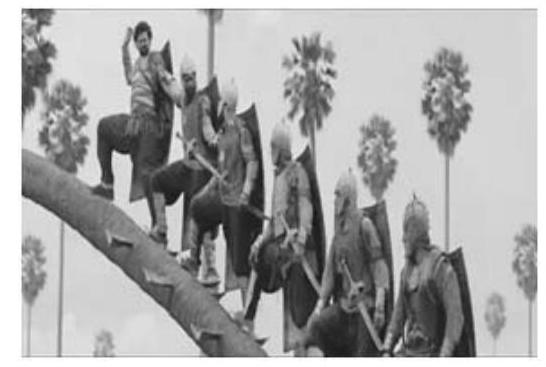

The popularity of the meme-frame determines the success of a meme. For instance, Fig 9 is a meme-frame taken from the blockbuster film Bahubali. The image shows soldiers bending tall palm trees to cross over a huge fort amidst battle. Fig 10 is a finished meme, in which a premise is inserted through

language. This is done through a caption which reads: Workers in Gujarat return to their houses after a day’s work. This meme refers to the wall built in Ahmedabad to screen slums ahead of US president Trump’s visit to India in February 2020. Fig 8 demonstrates a complex intertextual mixing of two pet themes of the Malayali public: politics and movies, by using a movie frame to deliver a political message. One will find it nearly impossible to translate these with the same emotional effect to someone who does not know the language or the context of the original meme-frame.

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Sources: https://www.quora.com/What-are-some-of-the-funniest-scenes-in-Baahubali-2 http://trollmallus.blogspot.com/2017/04/icu-bahubali-trolls-and-many-more.html

The Language component refers to the ways in which “languaging” is performed through fixed expressions and speech characteristics. Language restricts the spread of a meme and will arrest it within a specific linguistic boundary. Language includes the peculiarities of dialects, vernacular usages, and slangs to enhance the impact and the communicative capacity of the memes and allow the readers to connect with the issues raised. “I can has cheeseburger?”, a caption that went viral in the western media. On 11 January, 2007 a blogger based in Hawaii posted an image of a smiling cat, with a caption of the cat asking “I can has cheeseburger?” Soon enough it was tagged to a wide variety of other images. The caption, then, quickly became the basis for a particular pidginized variety of written English. This inspired the use of ungrammatical sentence structures in mainstream Facebook meme groups like FFC (Fan Fight Club), ICU (International Chalu Union), and Troll Malayalam in Kerala. Such experiments with language produce a community of viewers who are in-the-know of the meme

subculture. To draw an example from the Malayalam context, When the Cochin metro was inaugurated, the presence of a Kummanam Rajasekharan raised eyebrows as he was seen among the dignitaries. The accusation was that Kummanam Rajasekharan, the then BJP state president, was not in the list of dignitaries who were supposed to be a part of the inaugural ceremony (The News Minute, 2017). Opposition leader Ramesh Chennithala, local MLA P T Thomas, and Metro Man E Shreedharan were not permitted to share the metro travel with the Prime Minister citing security reasons. Hence, the presence of Mr Rajasekharan seemed uninvited and it was seen as a clear case of security breach. Memes started flowing and the word “Kummanadi” was coined which means ‘the act of travelling without buying tickets’ and later the definition has widened to ‘attending events uninvited’. Mr Rajasekharan denied all the allegations regarding the issue, stating that the Kerala police and the Special Protection Group (PSG) of the prime minister had informed him that his name was on the list of invitees. However, all this effort could not stop the spreading of the meme. The online meme logic sometimes transcends the digital spaces to shape the lived experiences of people. It is interesting to note that these new coinages spill over to offline communications too, thereby altering an existing language or slang. Though, the meme related to Mr Rajasekharan emerged in a context of political rivalry, Kummanadi is now a common expression that gets into the conversations of people in Kerala, both online and offline. Memes like this, catalysed a verbal migration of Malayalam language. A slang that was confined to a village in Kerala, now has the potential to spread across countries and cultures through online communication.

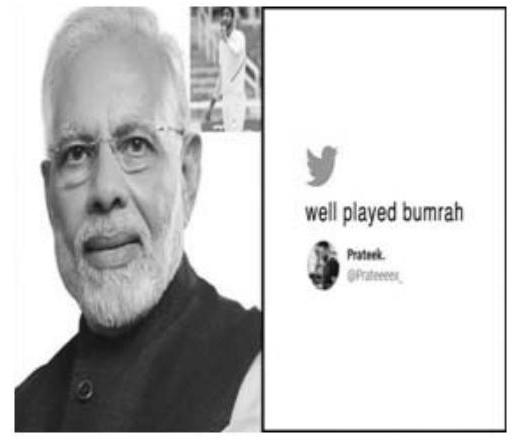

The most prominent component in a meme is the premise of the meme, because it connects the individual meme to a larger conversation. Participatory media facilitates vast constellations of individual expression, which intertwine into collective commentary, even as specific texts rise and fall. Memes occupy the world of collaborative creation suggested by An Xaio Mina (2019), where it is the larger conversation that matters rather than its individual components. Hence, it could be stated that meme has a fixed premise with novel expressions (Milner, 2016, p. 88). In fact, every new expression can inspire a different string of premises, thereby making meme analysis open ended. Recently in the Indian context, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been part of a series of congratulatory

memes dedicated to the Tokyo Olympic winners. All these memes have an oversized picture of the Prime Minister with the winners occupying only a corner of the poster (Fig 12). This series of memes originated after the Central government’s official event to felicitate medal winners at Tokyo Olympics turned out to be a PR exercise for the Prime Minister. “The stage for the event carried a large banner congratulating the winners-but the biggest photo on the banner was P M Modi’s. The images of the winners were found as a cluster in one corner” (The Wire, 2021). Ever since the official event, Prime Minister Narendra Modi featured in a series of Memes. Here the individual meme texts contribute to a larger conversation which reflects deeper political connotations. One way of reading this phenomenon is to see it as an attempt to use soft events-Modi’s visit to the US, his birthday, his 20 years of public office-as opportunities to rehabilitate and celebrate the prime minister’s image. As political scientist Neelanjana Sircar has put it, Modi represents a "politics of vishwas"4, built around the idea that “anything good coming out of the government is a result of the Prime Minister’s personal intervention” (Venkataramakrishnan, 2020). The series of memes featuring Modi, attempts to build a counter move against this kind of propaganda push. The meme in Fig 11 refers to Indian fast bowler Jaspreet Bumrah’s five wicket haul in a test match against England. The meme has Jaspreet Bumrah’s photograph in a corner, hardly identifiable, and Modi’s image at the centre, with the caption “well played Bumrah”.

Fig 11

Felicitation Ceremony for Olympics winner.

Find the pics of winners

Fig 12

Sources: https://www.scoopwhoop.com/humor/twitter-memes-modi-congratulations-memes/

Conclusion

Today, memes have developed into a complete genre of communication among digital users. To fully understand its potential, one must look at the networked ecosystem of digital media and its functioning. Ryan M Milner (2016) uses the metaphor of the tapestry to theorize the phenomenon of memetic participation in the internet (pp. 2-4). Memetic participation implies the converging nature of social media which is characterised by a complex web of communication networks. Tapestry signifies an intricate or complex sequence of events. And this metaphor casts individual participatory media texts like tweets, Facebook posts and memes as strands that intertwine into threads of interaction, eventually forming whole tapestries of public conversation. According to Milner,

“when everyday members of the public contribute their small conversational strands to the vast cultural tapestry, they are memetically making their world. In other words, the aggregate texts, collectively created, circulated, and transformed by countless cultural participants are memetic”. (pp.2-3).

This kind of a digital environment enables us to operate within a participatory digital culture (Jenkins, et al., 2013). Participatory culture is a term that is often used for designating the involvement of users, audiences, consumers, and fans in the creation of culture and content. Examples are the joint editing of an article on Wikipedia, the uploading of images to Flickr or Facebook, the uploading of videos to YouTube and the creation of short messages on Twitter or Weibo. The participatory culture model is often opposed to the mass media and broadcasting model typical of newspapers, radio, and television, where there is one sender and many recipients. Scholars argue that culture and society become more democratic because users and audiences are enabled to produce culture themselves.

Endnotes

1{ }^{1} Richard Dawkins in his book “The Selfish Gene” (1976), introduced the idea of memes, while discussing the transfer of cultural information from person to person.

2{ }^{2} Gene-Meme metaphor refers to viewing memes only as a cultural corollary to the gene.

3 “Meme, Counter-Meme”(1994)

4{ }^{4} Neelanjana Sircar’s article on Scroll.in titled " The Politics of Vishwas: Political Mobilization in the 2019 Election" argues that Modi’s 2019 win represents a politics of Vishwas or trust, rather than Vikas or development.

References

Blommaert, J M E, & Varis, P K (2014). “Conviviality and collectives on social media: Virality, memes and new social structures.” Tilburg papers in Cultural Studies, No 108.

Dawkins, R (1976). The Selfish Gene. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Godwin, M (1994, October 01). Meme, counter-meme. Wired. h t t p s : / / www.wired.com/1994/10/godwin-if-2/.

Hemsley, J, & Mason, R M (2013). “The Nature of knowledge in social media age: Implications for knowledge management models.” Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 23, 138-176.

Jenkins, H, Ford, S, & Green, J (2013). Spreadable media: Creating Value and Meaning in Networked Culture. New York. New York University Press.

Marwick, A (2013). Memes. Contexts, 12-13. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1536504213511210

Milner, R M (2016). The World made Meme: Public Conversations and Participatory Media. England: MIT Press.

Podium at official event felicitates oversized Modi for Olympics, medal winners also feature. (2021, August 10). The Wire. https://thewire.in/politics/ podium-at-official-event-felicitates-oversized-modi-for-olympics-medal-winners-also-feature.

Shifman, L (2014). Memes in Digital Culture. England: MIT Press.

Venkataramakrishnan, R (2020, July 25). Neelanjana Sircar on Narendra Modi’s politics: “Murkier the data, easier it is to control narrative”. Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/968452/murkier-the-data-easier-it-is-to-control-narrative- neelanjan-sircar-on-narendra-modis-politics.

Why was BJP leader Kummanam on Kochi Metro with PM? Kerala Minister wants probe. (2017, June 17). The News Minute. https://www.thenewsminute.com/ article/why-was-bjp-leader-kummanam-kochi-metro-pm-kerala-minister-wants-probe-63823.

Wiggins, B E (2019). The Discursive Power of Memes in Digital Culture: Ideology, Semiotics, and Intertextuality. New York. Routledge.