Summary of Native American Tribes – X-Z – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Summaries: A B C D E-I J-K L-M N O P Q-R S T-V W X-Z

Ishi (Yana for Man) was the “last wild Indian.”

Yahi – Meaning “person” in their language, the Yahi constituted the southernmost group of the Yana division of the Hokan linguistic stock. They were hunter-gatherers who lived in small egalitarian bands without centralized political authority. Primarily living on Mill and Deer Creeks in northern California, they were reclusive. When white settlers began to invade their lands, they fiercely defended their diminishing mountain canyons’ territory. The last known survivor of the Yana people was from the Yahi tribe. He emerged from the mountains near Oroville, California, on August 29, 1911, after the last of his family died. Having lived his entire life hiding with his tribe in the Sierra wilderness, he had never been exposed to European-American culture. Though he refused to speak his name due to traditional customs, he was dubbed “Ishi,” the Yana word for “man.” Known as the “last wild Indian,” he was taken to the University of California, Berkeley, for study and protection, where he lived nearby until he died of tuberculosis in 1916. During the “study, his language was recorded.

Yahooskin – Also referred to as Yahuskin, they were a Shoshonean band that, before 1864, roved and hunted with the Walpapi about the shores of Goose, Silver, Warner, and Harney Lakes in Oregon. On October 14, 1864, they made a treaty with the U.S. Government, ceding their lands and placing them on the Klamath Reservation, established at that time. With the Walpapi and a few Paiute who had joined them, the Yahooskin were assigned lands in the southern part of the reservation, where they were engaged in agriculture, lived in willow lodges and log houses, and gradually abandoned their roaming proclivities. At the turn of the century, they were reported to have more than 100 members. Unfortunately, for those living on the Klamath Reservation in Oregon, including the Modoc, Klamath, and Yahooskin tribes, an act of Congress terminated federal recognition in 1954. It took away some 1.8 million acres of their reservation. In 1986, the Klamath Indian Tribe Restoration Act returned their federal recognition but did not return their land. Today, they are scattered primarily in Klamath County, Oregon.

Yakama – The Yakima (as it was spelled at the time), a Shahaptian tribe, were living on the banks of the Columbia, Wénatchee, and northern branches of the Yakima Rivers when Lewis and Clark came along in 1806. Numbering about 1,200 people at the time, they called themselves Waptailmim, “people-of-the-narrows,” or Pakintlema, “people of the gap,” from the situation of their village near Union Gap on the Yakima River. They primarily lived on salmon, roots, berries, and nuts. By the treaty of 1855, they and 13 other tribes gave up the territory from the Cascade Mountains to the Snake and Palus Rivers and Lake Chelan to the Columbia River. They were to form the Yakima Reservation under Kamaiakan, a Yakama chief. However, before the treaty could be ratified, the Yakima War broke out, and it was not until 1859 that the treaty provisions were enacted. Today, most of the over 8,000 tribal members live on the Yakama Reservation in south-central Washington. (The official spelling of the Yakama was changed by the tribe in 1994 from Yakima to Yakama in 1994 to reflect the native pronunciation.)

Yakonan Family – The Yakonan were a linguistic family formerly occupying territory in western Oregon, on and adjacent to the coast from the Yaquina River south to the Umpqua River. Composed of four tribes, including the Yaquina, Alsea, Siuslaw, and Kuitsh, they were notable for the practice of artificial head deformation. The Yakonan mythology and traditions were much like those of the tribes of the Washington Coast, but they showed traces of modification by contact with the California tribes to the south. Despite no totemic clan system, they tended to segregate into blood-related groups. There was a preference for marriage outside the tribe, though this rule was not strictly enforced. Slavery was an institution in full force until the tribes came under the control of the United States. They were removed to the Siletz Reservation in Oregon in 1855. Their numbers began to decline rapidly through the ravages of tuberculosis and extensive intermarriage with other tribal members. By the early 1900s, no census could be taken of specific members.

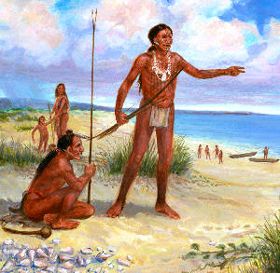

Yamasee Indians.

Yamasee – A former noted tribe of the Muskogean Family, they were best known in connection with early South Carolina history, but apparently, originally occupied the coast region and islands of southern Georgia and extending into Florida. Due to their location near the Savannah River, they were frequently confused with the Shawnee and Yuchi tribes. Missions were established in their territory by the Spaniards in about 1570, and they lived under the jurisdiction of the Spanish government of Florida until 1687. At that time, the Spaniards attempted to transport some of their people as laborers to the West Indies. Naturally, they revolted, attacking a number of the mission settlements and peaceful Indian tribes, before fleeing north across the Savannah River to the English colony of South Carolina. They were allowed to settle there in present-day Beaufort County, where they would establish several villages. They aided in the fight against the Tuscarora tribe in 1712. In 1715, when they became dissatisfied with the traders, they organized with other tribes, including nearly all of the tribes from Cape Fear to the Florida border, to fight against the English. Numerous traders were slaughtered, and a general massacre of settlers occurred along the Carolina frontier.

After several engagements, Governor Craven defeated the Yamasee at Salkechuh on the Combahee River and drove them across the Savannah River. They retired to Florida, where the Spaniards received them again and settled in villages near St Augustine. From then, they were known as allies of the Spaniards and enemies of the English, against whom they made frequent raids with other Florida tribes. In 1727, the English attacked and destroyed their village near St. Augustine, and their Indian allies and most of the inhabitants were killed. In 1761, what was left of the Yamasee numbered only about 20 men in camps near St. Augustine and Pensacola. Later, the Seminole tribe virtually destroyed the tribe, and those who survived were enslaved. As late as 1812, a small band retained the name among the Seminole, and some settled among the Hitchiti, but by the turn of the century, they had disappeared entirely.

Yamhill – A Kalapuyan family formerly living on Yamhill Creek, a western tributary of the Willamette River in Oregon. By 1910, they only numbered five. Any descendants of the Yamhill today are part of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon.

Yampa – A division of Ute Indians, the Yampa lived in eastern Utah on and about the Green and Grand Rivers. By 1849, they occupied 500 lodges. Bands of the Yampa included the Akanaquint arid Grand River Ute. They eventually merged with the White River Ute.

Yana – Having their own distinctive language, the Yana formerly occupied the territory from the Round Mountains near the Pit River in Shasta County to Deer Creek in Tehama County, California. The west boundary was about 10 miles east of the Sacramento River, both banks held by the Wintun tribe, with whom the Yana were frequently at war. They lived by hunting wild game, fishing for salmon, and collecting fruit, acorns, and roots. Unfortunately for the Yana, when gold was discovered in the area during the California Gold Rush, prospectors, ranchers, and businessmen flocked to their territory. Because their food supply began to diminish, they suffered significant losses and fought with the intruders. As a result, in 1865, the miners organized a large group and attacked the Yana camp, killing all but about 30 people. What was left of the tribe retreated into the mountain wilderness, and by 1902, only about six remained.

Yankton – See Nakota

Yaquina Indians.

Yaquina – This small tribe of Indians on the Oregon coast formed a small linguistic family that spoke the Alsean or Yakokna language, which is now extinct. They lived on the Yaquina River and bay near present Newport, Oregon. The early explorers and writers classed them as the Salishan tribes to the north but later were shown to be linguistically independent. They were coastal and river people, and they survived as fishermen and primarily hunted seals. Because of their coastal location, they came into contact with white trading vessels in the late 18th century, at which time they were reported to have numbered as many as 5,000. The tribe began to diminish as white settlers moved in, hastened by the activities of the Hudson’s Bay Company, miners, and the Rogue Wars of the 1850s. The remaining Yaquina people live on the Siletz Reservation in Oregon and are primarily of mixed blood.

Yatasi – A tribe of the Caddo confederacy, they were closely affiliated in language with the Natchitoch. They are first spoken of by Henri de Tonti, an Italian-born soldier, explorer, and fur trader in the service of France, who stated that in 1690 their village was on the Red River of Louisiana, northwest of the Natchitoch, where they were living in company with the Natasi and Choye Indians.

French explorers Louis Juchereau de St. Denis and Sieur de Bienville, during their explorations of the Red River in 1701, allied with the Yatasi and received no trouble from the tribe. The road frequented by travelers from the Spanish province to the French settlements on Red River and New Orleans passed near their village. When disputes erupted between the Spanish and the French over territorial boundaries, the Yatasi proved their steadfastness to the French interests by refusing to comply with the Spanish demand to close the road. When the Chickasaw were waging war along the Red River in the early 1700s, the Yatasi were among the sufferers, and part of the tribe sought refuge with the Natchitoch. Others fled up the river to join the Kadohadacho, Nanatsoho, Nasoni, and Caddo tribes. During the late 18th century, as more and more white settlers moved into the region, they brought with them the diseases of smallpox and measles, which devastated the tribe, reducing them to just a little more than 30 people by 1800. Today, the tribe is extinct, and those who claim descent live with the Caddo on the Wichita Reservation in Oklahoma.

Yazoo – Formerly living on the lower Yazoo River in Mississippi, their group was small. They were always closely associated with the Koroa tribe. The French, in 1718, erected a fort four leagues from the mouth of Yazoo River to guard the stream, which formed the waterway to the Chickasaw country. In 1729, in imitation of the Natchez tribe, the Yazoo and Koroa rose against the French and destroyed the fort, but both tribes were finally expelled. Later, they probably united with the Chickasaw and Choctaw tribes. Whether this tribe had any connection with the West Yazoo and East Yazoo towns among the Choctaw is not known. Today, the tribe is extinct.

Yodok – A former Maidu village on the east bank of the American River, just below the junction of South Fork in Sacramento County, California.

Yojuane – Labeled by several names, including the Diujuan, Lacovane, Iojuan, Joyvan, Yacavan, Yocuana, and Yujuane, they were a Tonkawan people, who ranged over a large area in east-central Texas. Initially, their territory extended from the Colorado River east of present-day Austin northward to the Red River. However, as more and more white settlers came to the area in the second half of the eighteenth century, the Yojuane were primarily confined to the southern portion of this range. Throughout the 18th century, the Yojuane shared the common Tonkawan hatred for the Apache Indians, and there is evidence of early hostilities with the Hasinai tribe.

They were at San Francisco Xavier de Horcasitas Mission near the site of present Rockdale between 1748 and 1756. By the mid-1800s, they were generally included among the bands of the Tonkawa, who were assembled on the Brazos Indian Reservation in present-day Young County. In 1859, however, they were moved to a reservation in Indian Territory. After the Civil War, some of the Tonkawa returned to northern Texas, where they lived until 1884, when they were forced back onto the reservation in Oklahoma. Today, the Tonkawa Indians are extinct as an ethnic group.

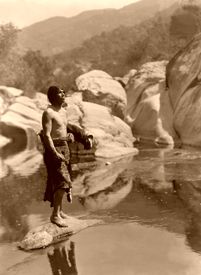

Quiet waters–Tule River Reservation, Yokut, Edward S. Curtis, 1924.

Yokuts Family – Also called Mariposan, a name derived from present-day Mariposa County, California, the Yokut name means “person” or “people.” Members of the Penutian Family lived on the floor of San Joaquin Valley from the mouth of the San Joaquin River to the foot of Tehachapi Mountains and the adjacent lower slopes or foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, up to an altitude of a few thousand feet, from the Fresno River south. Having numerous dialects the Yokut were comprised of as many as 50 separate hunter-gatherer tribes; they had numerous dialects. They occupied the entire San Joaquin Valley of central California from the mouth of the San Joaquin River to the foot of the Tehachapi Mountains and the adjacent lower slopes or foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, from the Fresno River south.

Yoncalla – The southernmost Kalapuyan tribe formerly lived on Elk and Calapooya Creeks, tributaries of the Umpqua River in Oregon. There were two bands of the group — Chayankeld and Tsantokau. The tribe is extinct today.

Yscanis – Also called the Yxcani Indians, these people were a tribe of the Wichita Confederacy who first made their home along the lower Canadian River in present-day Oklahoma. They were first met by the “white man” in 1719 when Jean Baptiste Bénard de la Harpe, a French explorer, made his way through the area. Under pressure from their bitter enemies, the Comanche and the Osage, they made their way to Texas by the middle of the 18th century. Fray José Francisco Calahorra y Saenz visited them in the area of North Texas in 1760 and failed to establish a mission for them. Twelve years later, in 1772, Athanase de Mézières visited them on the east bank of the Trinity River below the site of present Palestine. At this time, Mezieres described the village as consisting of 60 warriors and their families. They lived in a scattered agricultural settlement, raised maize, beans, melons, and calabashes, were closely allied with the other Wichita tribes, whose language they spoke, and were said by Mezières to be cannibals. Juan Agustín Morfí, in 1781 heard that they were living in a large village eight leagues up the Brazos River from the Tawakoni Indian settlement near the site of present Waco. The name “Yscanis” was last used in 1794. But a quarter of a century later, when the Tawakoni villages were again mentioned in the records, one of them appears as that of the Waco, a name formerly unknown in Texas and not accounted for by migration. The Waco may have been the Yscanis under a new name.

Big Turtle Dance of the Yuchi.

Yuchi – Also spelled Euchee and Uchee, the tribe previously lived in the eastern Tennessee River Valley in Tennessee, northern Georgia, and northern Alabama. They called themselves Tsoyaha, meaning “Children of the Sun.” Mysteriously, their language never closely resembled any other Native American language, suggesting a long period of isolation from other tribes. The first descriptions of the Yuchi, dating back to the 17th century, suggested that the Yuchi and the Westo were the same people. One of the first camps mentioned was Chestowee in southeastern Tennessee in 1714. Later, the camp was attacked and destroyed by the Cherokee. A large Yuchi camp known as “Uche Town” existed on the Chattahoochee River during the mid-1700s, located near Uche Creek. William Bartram visited it in the 1770s, praising its layout and thriving population.

More camps existed in present-day Aiken County, South Carolina, and several places along the Oconee River in Georgia. In the early 19th century, the Yuchi were forcibly removed along with the Muscogee to Oklahoma. Today, most Yuchi are of multi-tribal descent, and many are citizens of the Muscogee Creek Nation and other tribes, including the Shawnee and the Sac and Fox. Though the tribe has tried to obtain federal recognition, they have been unsuccessful since most Yuchi are enrolled in other tribes. Today, only a very few people can speak the distinctive Yuchi language, but efforts are being made to help preserve it in language classes.

Yufera – This name was applied to a town or group of towns reported to have been situated somewhere inland from Cumberland Island in present-day Georgia. The name was derived from the Timucuan people, but it may have referred to a part of the Muskogee tribe called Eufaula.

Yui – Once located on the mainland, 14 leagues inland from Cumberland Island and probably in the southeastern part of the present state of Georgia, they were described as having five villages. The name first appears in Spanish documents. The San Pedro visited them on the Cumberland Island mission and appear to have been Christianized early in the 17th century. At one time, the missionaries estimated them to number more than 1,000 in 1602. However, no individual mission bore their name, and they soon lost sight of their history, becoming that of the other Timucua tribes.

Yuki – A tribe from the Round Valley of Mendicino County in northern California, their name means “alien” or “enemy” The Yuki were of a much more warlike character than most California Indians. In the 1850s they were forced onto a reservation in Round Valley, where conditions led to the “Mendicino War” revolt in 1859, which further decimated the tribe. Today there remain but a hundred Yuki, only a dozen of which speak the language.

Yuma – Of the Yuman Family, the tribe traditionally lived in the Colorado River Valley and nearby areas in southern California and Arizona. Grouped into loose bands that averaged about 135 people, the bands were led by headmen who had shown skills as warriors and in economic matters. They were not nomadic and seldom left their villages, which were filled with homes made of a frame of logs and poles with a thatch covering. Built partially underground to keep out the extreme heat, the houses, usually about 20 by 25 feet, were usually occupied by several family members. The Yuma were farmers raising corn, beans, pumpkins, and melons. They were first visited by the Spanish explorer Juan de Oñate in 1604-05. They were described as a fine people, far superior to most other Indians. For centuries, they battled the Papago, Apache, and other tribes for control of the fertile flood plains of the Colorado River. By 1853, their numbers were estimated to be about 3,000. Today, many of the tribal members live on the Fort Yuma-Quechan Reservation, which is located along both sides of the Colorado River near Yuma, Arizona. The reservations’ nearly 2,500 members prefer to be called the Quechan (pronounced Kwuh-tsan). They continue to be an agricultural tribe but also operate several businesses and count on tourism as a large part of their economy. The reservation borders Arizona, California, Baja California, and Mexico, encompassing 45,000 acres.

Yuma musician Isaiah West Taber, around the turn of the 20th century.

Yuman Family – An important linguistic family, these tribes occupied the extensive territory in the extreme southwest portion of the United States and lower California, including much of the Colorado River Valley and the lower valley of the Gila River.

Their social groups were well-defined; they lived in communal huts, well constructed of cottonwood and well thatched, practiced agriculture, and made fine basketry and pottery. Interestingly, they did not borrow the art of irrigation from the Pueblo peoples, resulting in their crops often suffering from drought. They were also not boatmen. Instead, crossing rivers and transported their goods on rude rafts made of bundles of reeds or twigs. They cremated their dead and with them all articles of personal property. The climate favored nudity, with men wearing only the breechcloth, and not always that, while women generally wore short dresses made of strips of bark.

In the 18th century, Fray Francisco Garcés described them: “The Indian men of its banks are well-formed, and the Indian women fat and healthy; the adornment of the men, as far as the Jamajabs [Mohave], is total nudity; that of the women is reduced to certain short and scanty petticoats of the bark of trees; they bathe at all seasons, and arrange the hair, which they always wear long, in diverse figures, utilizing for this purpose a kind of gum or sticky stud.

They are always painted, some black, others red, and many with all colors. All those of the banks of the river are very generous and lovers of their country, in which they do not hunt game because they abound in all provisions.”

Important tribes of the northern Yuman area were the Cocopa, Diegueño, Havasupai, Maricopa, Mohave, Tonto, Walapai, Yavapai, and Yuma. They were said to have differed considerably, physically and otherwise, the river tribes being somewhat superior to the others. The population of the Yuman tribes within the United States numbered about 3,700 in 1909.

Yurok – The Yurok tribe, meaning “downriver people,” have lived near the Pacific Ocean coast of northern California and southern Oregon for as many as 10,000 years. The Yurok language is Algonquin, the farthest west in which the language has been found. The nomadic bands lived on hunting and fishing and gathering nuts, roots, and berries. In the winter, they concentrated in villages, living in rectangular houses with slanted cedar roofs. Social status was determined by wealth, and unlike other Native Americans, they practiced owning and selling land. After the gold rush of 1849, the Yurok lost most of their land; however, they now own several ranches in California, flourishing with hotels and gaming resorts. They are the largest Indian tribe in California, with nearly 5,000 enrolled members.

Yustaga – Located between the Aucilla and Suwannee Rivers near the Florida Coast, the Yustaga belonged to the Timucuan branch of the Muskhogean linguistic stock. Luys Hernandez de Biedma, a chronicler for Hernando De Soto, first mentioned them, who named Yustaga a “province” through which the Spaniards marched just before arriving at Apalachee. Later, the French mentioned them and more Spaniards who came through the area. Their history soon merged with the Timucuan people. The last mention of the name appears to be in 1659. They were estimated to have numbered as many as 1,000 in 1,600, but by 1675, they had already been reduced to about 350.

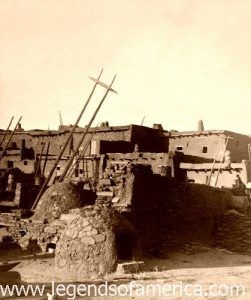

Zuni Pueblo 1873.

**Zuni**– The Zuni Indians of today are one of 19 original tribes that once inhabited the area that is now called New Mexico and Arizona. The Zuni tribe is said to have originated from the ancient Ancient Puebloans, a prominent society encompassing large amounts of land, riches, and many distinct cultures and civilizations. The Zuni people are, in a way, a mysterious tribe. Their culture is as reclusive and isolated as their city and language. They are very interesting and well-known people for their beautiful artwork, sculpture, and dishware. The Zuni are one of the few fortunate tribes who have managed to keep their ways of life the same throughout the years despite the westward push of the European immigrant settlers, the Mexican-American war, and the rough treatment they endured during all of the conflicts that they dealt with.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

Also See:

Ancient Cities of Native Americans

Native American Archaeological Periods

Native Americans – First Owners of America

Sources:

Handbook of Texas Heard, Norman J., Handbook of the American Frontier, Scarecrow Press, 1987

NCpedia Ricky, Donald, Encyclopedia of Mississippi Indians, Somerset Publishers, 2000

Webb, Frederick, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, 1906

Wikipedia