A protective mechanism of probiotic Lactobacillus against hepatic steatosis via reducing host intestinal fatty acid absorption (original) (raw)

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which is characterized by fat accumulation in the liver without significant alcohol consumption, is the most common liver disease in the world1. With the increased prevalence of obesity, the number of patients with NAFLD has rapidly increased over the past 20 years, with an estimated prevalence of ~25–30%2. The prevalence of NAFLD in patients with other metabolic diseases, such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, is greatly increased3. NAFLD includes a broad range of liver disease from simple steatosis to inflammatory steatohepatitis. Although simple steatosis is the mildest form of NAFLD, it is important in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, which is distinguished by the presence of hepatocyte injury (ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes), inflammation, and/or fibrosis1,4. Simple steatosis is characterized by the deposition of triglycerides (TGs) as lipid droplets in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes1,5. A key process of simple steatosis is an imbalance between fatty acid input (synthesis and uptake) and output (export and oxidation)6,7; thus, intestinal lipid absorption is important in the development of the initial progress of NAFLD. Excessive dietary lipid absorption causes fat accumulation in extraintestinal tissues, such as liver and adipose tissue, which contributes to the development of simple steatosis and obesity8. Therefore, reducing intestinal lipid absorption would be an etiological strategy for developing a drug against NAFLD and associated metabolic diseases.

Probiotics, live microorganisms, confer health benefits, such as modulation of the gut microbiota, and antiobesity effects on the host and may serve as a potential alternative therapy for disease prevention and treatment9. Currently, both clinical and basic research have revealed several distinct cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of probiotics, including blocking pathogenic bacterial effects, regulating immune responses, and modulating intestinal epithelial homeostasis10. Long-term administration of Lactobacillus species, the most widely used probiotics11, has been reported to protect mice from NAFLD induced by a high-fat diet (HFD) and improve gut permeability, inflammation, and modulation of gut flora in a diet-induced obesity model12,13,14. However, existing studies on NAFLD focused on mainly inflammatory defense despite imperceptible inflammatory phenotypes in HFD-fed rodent models15,16 and did not quantitatively study whether probiotic Lactobacillus had any effect on the early progression of steatosis via the regulation of intestinal lipid absorption in vivo. Furthermore, despite previous studies showing that the gut microbiome accounts for 30% of the energy absorption of the host17,18, there is little research on which intestinal microorganisms can affect the host’s energy absorption. Oleic acid (OA), one of the major fatty acids in the diet19, has been suggested to incorporate into the cell membrane of Lactobacillus in vitro20, where it is further converted to cyclopropane fatty acids21,22, or to increase their survivability against acidic environmental conditions23,24. OA has also been commonly used as a major supplement for the growth media of Lactobacillus species (e.g., MRS broth, Difco, Detroit, MI). These observations lead us to hypothesize that Lactobacillus reduces intestinal lipid absorption, thereby protecting against diet-induced steatosis in vivo. Thus, we quantitatively examined whether L. rhamnosus GG consumes exogenous OA in a HFD-fed mouse model using radioactive tracers both in vitro and in vivo.

Methods

Mass spectrometry-based measurement of fatty acids in tissues and bacterial cultures

Long-chain acyl-CoAs (LCACoAs) and diacylglycerides were extracted from snap frozen liver tissues of both mice fed regular chow and mice fed a 60% HFD for one week. LCACoAs were purified using a solid phase extraction method described previously; OPC columns (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) were used for the solid phase extraction25. Diacylglycerides were extracted using the Folch method26. Liver LCACoA and diacylglyceride contents were measured using a bench-top tandem mass spectrometer, 4000 Q TRAP (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), as previously described25. The consumption of fatty acids by L. rhamnosus GG was measured by an ultra-performance liquid chromatography/quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-TOF/MS, Synapt G2Si, Waters, USA)-based metabolite profiling. One milliliter of cultured broth was centrifuged (10 min, 4000×g) every 3 h for 12 h, and metabolite profiles of the supernatant were analyzed with an UPLC Q/TOF–MS system in ESI (-) mode. Mass data, including retention time (RT), m/z, and ion intensities, were extracted using Progenesis QI software packages (Waters), and the peak of each fatty acid was selected on the basis of RT and accurate mass.

Fatty acid and glucose consumption during bacterial cultivation

Fatty acid consumption of Lactobacillus strains, L. rhamnosus GG (ATCC 53103), L. acidophilus (ATCC 4356), and L. gasseri (ATCC 33323) in bacterial growth medium was evaluated quantitatively using radioactive tracers, [14C]-OA and [14C]-palmitic acid (PA) (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The glucose concentration in each bacterial medium was measured using a GM9 glucose analyzer (Analox Instruments, London, UK). Overnight cultures of Lactobacillus were diluted 100-fold (v/v) and subcultured three times to achieve viability, as described previously27. [14C]-OA (1 µci) was added to 10 ml of MRS growth medium at 20 g/l, and three Lactobacillus strains (1x108 cfu of each strain) were cultured for 6 h with shaking (37 °C at 220 rpm). For L. rhamnosus GG, 1 μci of [14C]-OA and [14C]-PA were further tested. One milliliter of cultured broth was aliquoted every 3 h and centrifuged (10 min, 4000×g), and the supernatant was collected. The pellet was resuspended and washed three times in MRS broth (10 min, 4000×g). 14C radioactivity was measured in both the supernatant and pellet of each aliquoted sample using a β-counter (Beckman scintillation counter, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Fatty acid accumulation in cultured intestinal cells

To test whether the fatty acid consumption capacity of L. rhamnosus GG affects cellular fat accumulation in vitro, C2BBe1 cells (cloned from intestinal CaCo-2 cells, ATCC CRL-2102) were cocultured with L. rhamnosus GG using a 0.4 µm pore insert to exclude direct interactions between C2BBe1 cells and surface particles of L. rhamnosus GG, with minor modifications, as previously described28,29. Briefly, C2BBe1 cells were cultured at 37 °C under 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 μg/ml streptomycin, 10 U/ml penicillin (Welgene, Daegu, Korea), and 0.01 mg/ml human transferrin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). For experimentation, the cells were plated at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well into six-well plates and were grown for 7 days postconfluence in culture medium. The experimental medium was prepared as follows: 100 μl of L. rhamnosus GG culture, grown to a concentration of 2 × 108 cfu/ml in MRS broth, was added to 10 ml of DMEM containing 500 μmol/l OA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and the pH was adjusted to 7.4. Approximately 2 × 108 cfu/ml L. rhamnosus GG was seeded on a Transwell membrane (SPL, Pochon, Korea) and inserted into a six-well culture plate containing C2BBe1 cells. As a control group, formalin-killed L. rhamnosus GG were prepared by immersion into 10% formalin for 1 h, followed by washing five times with PBS, and then resuspension into culture medium at a concentration of 1 × 109 cfu/ml. To confirm bacterial death, formalin-killed bacteria were cultured in MRS broth for 24 h. After 6 h, C2BBe1 cells cocultured with L. rhamnosus GG under OA-treated conditions were collected, and TG extraction and quantification was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI).

Animals

Two animal studies were performed regarding HFD feeding. The long-term HFD study was performed for 9 weeks to evaluate the chronic effects of L. rhamnosus treatment on hepatic lipid accumulation and obesity. A short-term HFD study was performed for 1 week to determine whether intestinal lipid absorption is an underlying mechanism without differences in body weight or inflammatory status. To match ages on the experimental day, 5-week-old and 13-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and used for the long-term and short-term studies, respectively. In each study, HFD-fed mice were divided into two groups: a live L. rhamnosus GG-treated group (LGG, 1 × 109 cfu/mouse/day) and a formalin-killed L. rhamnosus GG-treated group (fLGG, 1 × 109 cfu/mouse/day). Regular chow diet (RCD)-fed mice were given saline instead of the bacteria. Each L. rhamnosus GG and saline treatment was administered daily to mice by oral gavage during the study period. Mice were individually housed in a specific pathogen-free facility under controlled temperature (22 ± 1 °C), humidity (55 ± 10%), and lighting (12-h light/dark) with free access to water and fed ad libitum with the HFD (45%, D12451, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, for the long-term study; 60%, D12492, Research Diets, for short-term study) or regular chow diet (5053, Labdiet, St. Louis, MO). Body weight and food intake were monitored weekly. Body fat composition was measured by 1H-NMR (Bruker Optics, Billerica, MA). All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Gachon University and Seoul National University.

Oil red o and Hematoxylin and eosin staining

In vitro, C2BBe1 cells were cocultured with L. rhamnosus GG under OA-treated conditions for 6 h, and then Oil Red O (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Oil Red O deposits were observed via light microscopy in the phase contrast view. For in vivo samples, paraffin sections of livers were stained with hematoxylin and eosin as described previously27. Cryosections of livers were stained with Oil Red O to visualize lipid droplets as described previously30. For individual scores for histopathological evaluation of hepatic steatosis, slices of the liver tissue were scored according to the criteria described previously31. Briefly, steatosis (0–3), lobular inflammation (0–2), hepatocellular ballooning (0–2), and fibrosis (0–4) were separately scored, and the NAFLD activity score (NAS) was expressed as the sum of each score.

Quantitative measurement of intestinal lipid and glucose absorption in vivo

In the short-term HFD study, the LGG and fLGG groups were fasted overnight following 1 week of HFD feeding. Ten microcuries of [14C]-OA and 100 μci of [3H]-glucose (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) were dried and resuspended in 5 ml of MRS broth. After collection of fasting blood samples (0 min), 500 µl of the mixture (10 µci of [3H]-glucose and 1 µci of [14C]-OA) was orally administered to mice of each group. Intestinal fatty acid and glucose absorption were determined by measuring the plasma occurrence of [14C]-OA and [3H]-glucose radioactivity at 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. Tracer assays were performed after extracting the organic phase for [14C]-OA and after deproteinizing using barium hydroxide and zinc sulfate for [3H]-glucose, as previously described7,32.

Basal plasma parameters

Blood samples collected by cardiac puncture from overnight-fasted mice were centrifuged for 20 min at 3000×g and stored at −20 °C. Total cholesterol, TG, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, aspartate transaminase (AST), and alanine transaminase (ALT) were measured in plasma using a Cobas c111 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Plasma nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA) content was measured using a colorimetric assay kit (Wako, Osaka, Japan).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from C2BBe1 cells and snap-frozen small intestine jejunums, livers, brown adipose tissues, and gastrocnemius skeletal muscle of overnight-fasted animals using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fishers Scientific, Waltham, MA). RNA was quantified by 260/280 wavelength measurement using a NanoDrop 2000C spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Pure RNA was reverse transcribed using a TOPscriptTM RT DryMIX kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Enzynomics, Daejeon, Korea). Real-time PCR was performed on an applied Biosystems 7300 Real-time PCR system (Thermo Fishers Scientific, Waltham, MA). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Fecal microbiota composition and fecal calorie excretion analyses

In the short-term HFD study, fecal samples from three groups were collected for 24 h following 1 week of HFD feeding. Samples from five mice in each group were combined, and the fecal microbiota composition was analyzed by Illumina sequencing performed by GenomicWorks (GenomicWorks, Daejeon, Korea) as described previously33,34,35,36. Briefly, PCR amplification was performed with extracted DNA using primers targeting the V3–V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene. The amplified products were purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and assessed on a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) using a DNA 7500 chip. Sequencing was carried out with an Illumina MiSeq Sequencing System according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA). To measure fecal exergy excretion, feces were collected during the last 48 h, and calorie content in dried feces was analyzed by bomb calorimetry using a Parr 6400 Calorimeter (Parr, Moline, IL).

Statistics

All results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. The significance of the differences in mean values among two groups was evaluated by two-tailed unpaired Student's _t_-tests. More than two groups were evaluated by one-way or two-way ANOVA (in the case of two independent variables) followed by post hoc analysis (Bonferroni, GraphPad Prism 5.0). _P_-values<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

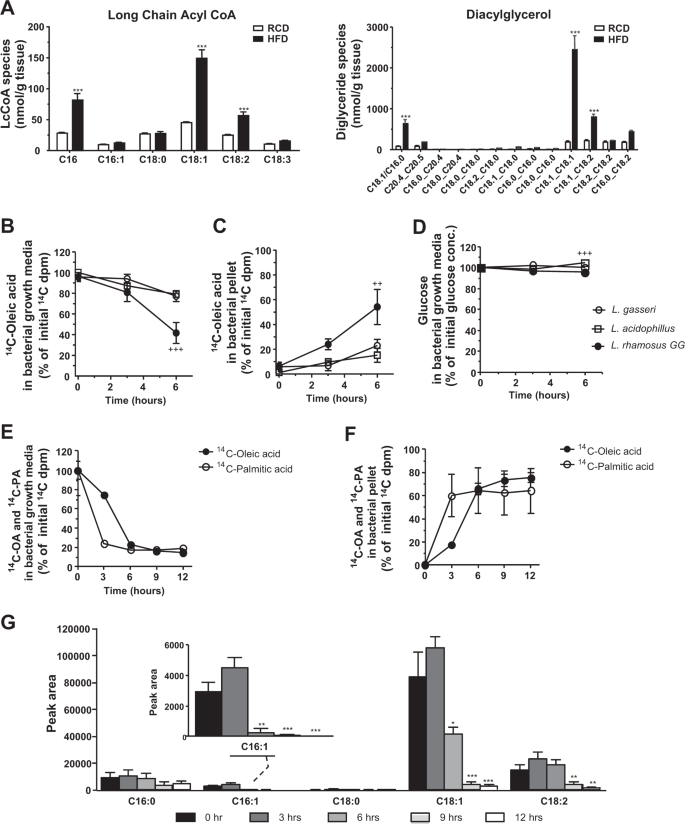

OA is the most abundant fatty acids in the liver of HFD-fed mice

OA is a common dietary unsaturated fatty acid in human diets and is present in many rodent HFDs (i.e., D12492) used in metabolic studies37. OA accounts for ~34% of the composition of fatty acids in the HFD (Supplementary Table 1). Hepatic fatty acid composition reflected the diet. Specifically, OA (C18:1) was the most abundant long chain fatty acid in the HFD-fed mouse livers and was dramatically increased during HFD feeding in the liver (Fig. 1a, left). Furthermore, we also showed that OA was the most abundant fatty acid among the diacylglycerol species (Fig. 1a, right), which are known to play causative roles in insulin resistance, a major culprit of metabolic diseases7,38,39. PA, another key player in metabolic diseases40,41, occupied the highest percentage of saturated fatty acids in both the diet and liver (Fig. 1a, left). These results suggest that the dietary fatty acids ingested reflect fatty acid composition in the liver.

Fig. 1: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG consumes exogenous fatty acids.

a Diet-dependent hepatic long-chain acyl CoA (left panel) and diacylglycerol (right panel) (n = 6 per group). [14C]-OA radioactivity measured in b bacterial growth media and in c bacterial pellets. d Percentage of glucose concentration measured in bacterial growth media. [14C]-OA and [14C]-PA radioactivity measured in e bacterial growth media and in f bacterial pellets. g Relative peak area of fatty acids detected in the growth media after 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 h of incubation of L. rhamnosus GG (n = 6 per group). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. ++P < 0.01 and +++P < 0.001 for the difference between L. rhamnosus GG and others by two-way ANOVA and **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis (Bonferroni)

Lactobacillus strains consume exogenous OA in bacterial growth media

Since it has been suggested that Lactobacillus strains use an exogenous OA source that is converted to cyclopropane fatty acid to increase their survival in acidic conditions in vitro23, we quantitatively measured whether Lactobacillus strains consume OA under normal growth conditions by using an [14C]-OA tracer. We cultured three Lactobacillus strains, namely, L. gasseri, L. acidophilus, and L. rhamnosus GG, in MRS broth with isotope-labeled [14C]-OA for 6 h and measured the radioactivity of [14C]-OA in bacterial growth media and bacterial pellets. During 6 h of growth, [14C]-OA radioactivity in the bacterial growth medium was markedly decreased by ~60% compared to the initial [14C]-OA activity by L. rhamnosus GG strains (Fig. 1b). The decreased radioactivity in the growth medium was associated with increased radioactivity in bacterial pellets (Fig. 1c), which indicates the incorporation of exogenous OA into the bacteria. However, the other Lactobacillus species, L. gasseri and L. acidophilus, showed only slight changes in [14C]-OA activity, accounting for ~20% decreases in the bacterial growth medium and ~20% increases in bacterial pellets during the 6 h of growth (Fig. 1b, c). The glucose concentration of the medium was similarly stable during growth of all three Lactobacillus strains, although L. rhamnosus GG showed slight decreases at 6 h (Fig. 1d). These results quantitatively indicate that L. rhamnosus GG consumes exogenous OA to a greater extent than other Lactobacillus strains in growth media.

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG consumes fatty acids during cultivation

To further test whether L. rhamnosus GG consumes specific fatty acid substrates, we cultured L. rhamnosus GG in MRS broth with isotope-labeled [14C]-OA and [14C]-PA for 12 h and measured the radioactivity in bacterial growth media and bacterial pellets. In bacterial growth medium, [14C]-PA radioactivity was decreased by ~70% at 3 h, and [14C]-OA radioactivity was decreased by ~70% at 6 h by L. rhamnosus GG (Fig. 1e) compared to the initial radioactivity. Each decrease in radioactivity in growth media was associated with increased radioactivity in bacterial pellets (Fig. 1f). Consistent with the radioactive tracer data, the fatty acid consumption of L. rhamnosus GG measured by UPLC-Q-TOF/MS showed similar results. While saturated fatty acid species, such as C16:0 and C18:0 in the media had a nonsignificant trend of decrease, fatty acid species containing double bonds (C18:1, C18:2, and C16:1) were significantly decreased over time in the bacterial growth medium (Fig. 1g). In particular, C16:1 and C18:1 showed earlier decreases than C18:2, even after 6 h of growth (Fig. 1g). These data quantitatively suggest that L. rhamnosus GG prefers fatty acids as its substrate during cultivation.

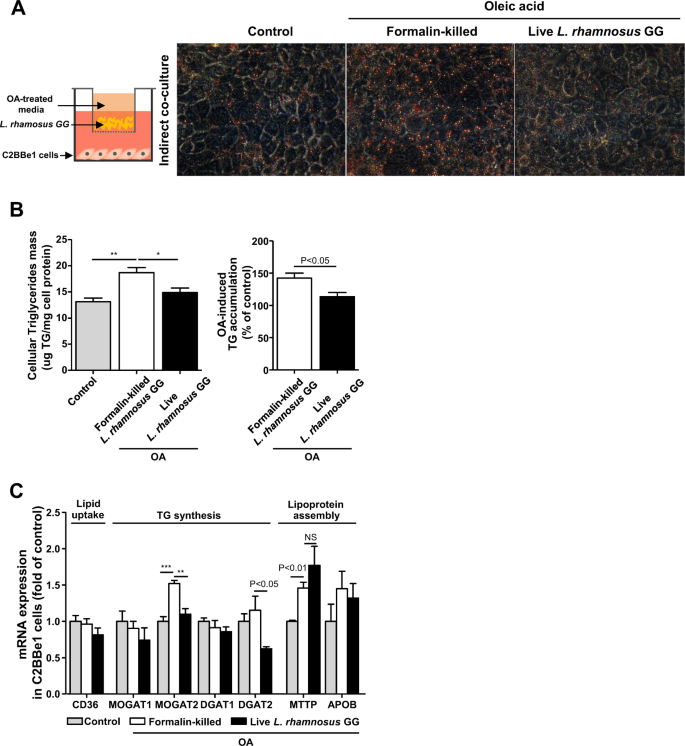

L. rhamnosus GG reduces lipid-induced fat accumulation in intestinal C2BBe1 cells

Next, we investigated whether L. rhamnosus GG reduces lipid absorption at the cellular level using human intestinal C2BBe1 cells. To distinguish the effect of live bacteria on fatty acid consumption, we used both live L. rhamnosus GG and formalin-killed L. rhamnosus GG and cocultured them with C2BBe1 cells under OA-treated conditions for 6 h. Direct interaction of cells and bacteria was prevented by using an indirect coculture system (Fig. 2a). After 6 h of culture, OA-induced lipid accumulation, which was measured by both Oil Red O staining (Fig. 2a) and a TG kit (Fig. 2b), was significantly decreased by L. rhamnosus GG compared to that of formalin-killed L. rhamnosus GG. Accordingly, mRNA expression of monoacylglycerol acyltransferase (MOGAT) 2 and diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT) 2, involved in TG synthesis, were significantly decreased in L. rhamnosus GG-treated C2BBe1 cells compared to that observed in formalin-killed L. rhamnosus GG-treated C2BBe1 cells (Fig. 2c). There were no differences in the expression of fatty acid uptake genes, such as cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36), and lipoprotein assembly genes, such as microsomal TG transfer protein (MTTP) or apolipoprotein B (APOB) (Fig. 2c). These results indicate that L. rhamnosus GG reduces OA-induced lipid accumulation in intestinal cells via limiting the exogenous OA source.

Fig. 2: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG reduces oleic acid-induced intestinal fat accumulation in vitro.

a Oil Red O staining of OA-induced lipid accumulation in C2BBe1 cells cocultured indirectly with L. rhamnosus GG (original magnification ×40). b Cellular TG mass and OA-induced TG accumulation by the control. c mRNA levels of genes related to intestinal lipid metabolism in C2BBe1 cells. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis. Statistical comparisons obtained by Student’s _t_-test. NS, nonsignificant. Formalin-killed LGG, formalin-killed L. rhamnosus GG-treated C2BBe1 cells. Live LGG, live L. rhamnosus GG-treated C2BBe1 cells

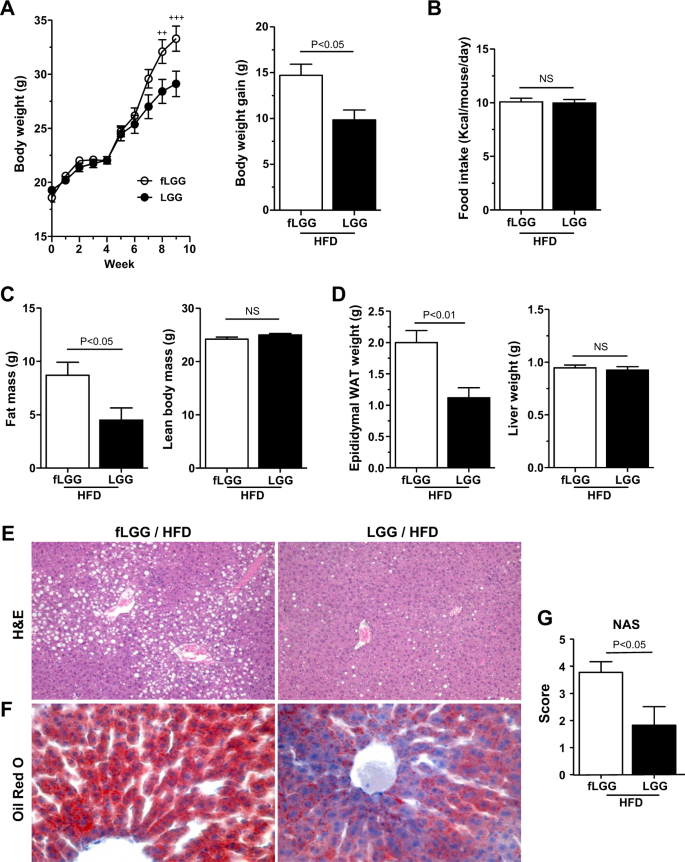

Long-term feeding of L. rhamnosus GG reduces the gain of fat mass and hepatic lipid accumulation in HFD mice

Next, we assessed the effects of L. rhamnosus GG on the development of the level of diet-induced hepatic steatosis in vivo using a HFD-fed mouse model. During 9 weeks of HFD feeding, body weight began to diverge after 6 weeks and was significantly lower in the LGG group than in the fLGG group after 8 weeks of HFD feeding (Fig. 3a, left). After 9 weeks of HFD feeding, the LGG group exhibited an ~33% decrease in body weight gain compared to that of the fLGG group (Fig. 3a, right). Food intake during the experimental period was identical between the LGG and fLGG groups (Fig. 3b). The difference in body weight between the LGG and fLGG groups was ~5 g, which was mostly accounted for by decreased fat mass measured by 1H-NMR (Fig. 3c, left), as no difference in lean body mass was observed (Fig. 3c, right). Accordingly, epididymal white adipose tissue (WAT) weight was significantly decreased by ~50% in the LGG group compared to that in the fLGG group (Fig. 3d, left). Hepatic lipid accumulation revealed by Oil Red O staining (Fig. 3f) and NAS (Fig. 3g) was decreased in the LGG group compared to that in the fLGG group, mainly at the area of the central vein (Fig. 3e). We did not find any noticeable level of fibrosis or inflammatory foci in either the LGG or fLGG group (Fig. 3e). The liver weight between the LGG and fLGG groups was identical (Fig. 3d, right). These results indicate that L. rhamnosus GG protects against diet-induced hepatic lipid accumulation in the early stages of NAFLD.

Fig. 3: In vivo, body weight gain and fat mass are decreased in the LGG group during long-term HFD study.

a Left panel: body weight change curve during experimental periods; right panel: body weight gain. b Food intake. c Body composition. The left panel is the fat mass, and the right panel is the lean body mass. d Tissue weight. The left panel is the epididymal white adipose tissue (WAT) weight, and the right panel is the liver tissue weight. e Hematoxylin and eosin staining and f Oil Red O staining of liver sections (original magnification ×20). g NAFLD activity score (NAS). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 5–6 per group). ++P < 0.01 and +++P < 0.001 by two-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis. Statistical analysis performed by Student’s _t_-test. NS, nonsignificant

Short-term feeding of L. rhamnosus GG reduces intestinal lipid absorption without increasing fecal excretion

Since long-term HFD feeding can influence the level of inflammation42, gut permeability43, composition of gut flora44, and body weight, all of which could have an effect on hepatic lipid accumulation, we chose an earlier period of HFD feeding, 1 week, to minimize these confounding factors and test whether L. rhamnosus GG inhibits intestinal OA absorption in vivo as was seen in vitro (Fig. 2). During 1 week of HFD feeding, body weight was similarly increased in both the fLGG and LGG groups (Fig. 4a); however, the gain of fat mass was slight but significantly reduced in the LGG group compared to that in the fLGG group (Fig. 4b). A [14C]-OA isotope was used to quantitatively measure the amount of lipid absorption from the intestinal rumen to the blood stream. Plasma [14C]-OA activity was significantly decreased in the LGG group compared to that in the fLGG group (Fig. 4c), while there were no differences in plasma [3H]-glucose (Fig. 4d), indicating no effect on glucose absorption. Both daily calorie intake (Fig. 4e) and fecal calorie excretion (Fig. 4f) were identical between the fLGG and LGG groups. Lean body mass, liver tissue weight, and circulation parameters, such as cholesterol, TG, NEFA, LDL, HDL, AST, and ALT levels, were identical between the fLGG and LGG groups (Supplementary Table 2). These results indicate that L. rhamnosus GG reduces intestinal OA absorption in the host by consuming the fatty acid in the intestinal rumen but not excreting it into feces.

Fig. 4: In vivo, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG reduces fat mass gain and intestinal lipid absorption during a short-term HFD study.

a Left panel: body weight change curve during experimental periods; right panel: body weight gain. b Left panel: fat mass; right panel: fat mass gain. c [14C]-OA radioactivity measured in plasma. d [3H]-glucose radioactivity measured in plasma. e Calorie intake. f Fecal calorie excretion. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 5–7 per group). +P < 0.05 and +++P < 0.001 by two-way ANOVA and **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis. NS nonsignificant

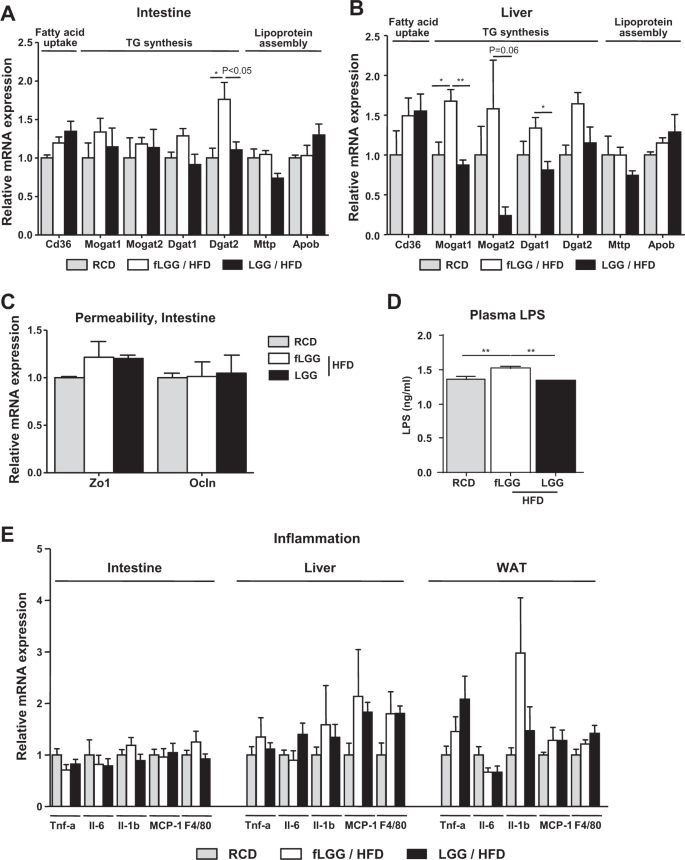

L. rhamnosus GG reduces the mRNA expression of genes related to lipid metabolism

In agreement with the gene expression data obtained from intestinal cells (Fig. 2c), the mRNA expression of lipid synthesis genes, Dgat1 and Dgat2, after 1 week of HFD feeding was decreased in the intestines of the LGG group compared to that in the intestines of the fLGG group (Fig. 5a). There were similar changes in the liver, as Mogat1, Mogat2, Dgat1, and Dgat2 gene expression was decreased in the LGG group (Fig. 5b). However, the mRNA expression of fatty acid uptake genes, such as Cd36, and lipoprotein assembly genes, such as Apob and Mttp, was not different among the groups in both the intestine and liver (Fig. 5a, b). Consistent with the intestine and liver, brown adipose tissue showed a similar mRNA expression pattern; TG synthesis-related gene expression was decreased in the LGG group compared to that in the fLGG group, but fatty acid uptake gene expression was not different among groups in brown adipose tissue (Fig. S1A). There were no differences in the expression of both fatty acid uptake and TG synthesis genes in gastrocnemius skeletal muscle (Fig. S1B). In the intestine, we further analyzed the expression of genes related to gut permeability45, namely, zonula occludens 1 (Zo1), tight junctions of intestinal cells, namely, occludin (Ocln), and inflammation, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (Tnf-α), interleukin (Il)-6, Il-1β, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and F4/80, but none of these were different between the groups (Fig. 5c and e). Plasma LPS content was slightly reduced in the LGG group compared to that in the fLGG group (Fig. 5d). The mRNA expression of inflammatory markers was not changed in other tissues, including liver and WAT (Fig. 5e). These results indicate that L. rhamnosus GG affects intestinal lipid absorption of a host and the regulation of genes involved in TG synthesis but does not affect the expression levels of genes involved in gut permeability and inflammation during short-term HFD feeding.

Fig. 5: The effect of L. rhamnosus GG on lipid metabolism, gut permeability, and inflammation during short-term HFD feeding.

mRNA expression of genes related to fatty acid uptake, TG synthesis and lipoprotein assembly in the a intestine and b liver. c mRNA expression of genes related to gut permeability. d Plasma LPS concentration. e mRNA expression of genes related to inflammation in the intestine, liver, and epididymal WAT. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 5–6 per group). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis. Statistical analysis performed by Student’s _t_-test

Diversity and population of the gut microbiota are altered by diet but exhibit reduced changes in the presence of L. rhamnosus GG treatment

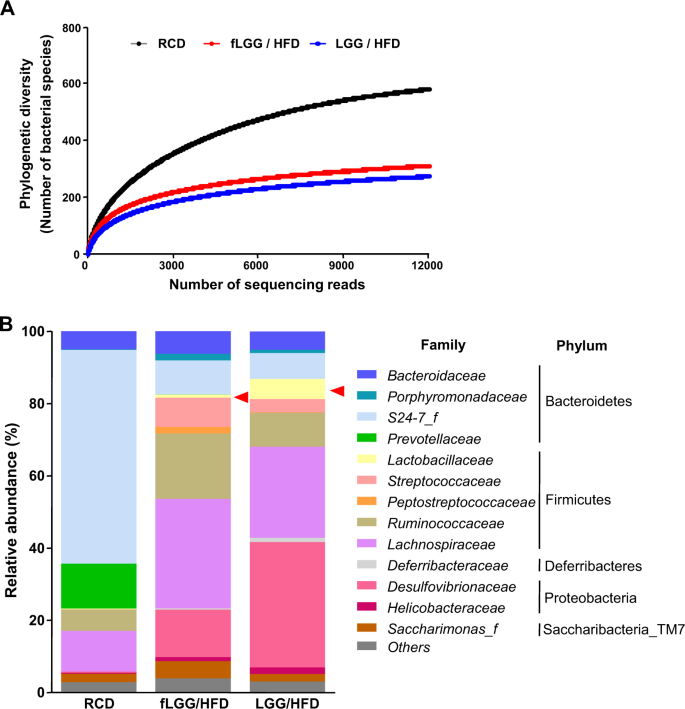

Since it is possible that altered gut microbiota due to probiotic administration could affect intestinal lipid absorption46, we investigated whether L. rhamnosus GG affected the phylogenetic richness of the gut microbiota during short-term HFD feeding. We analyzed α-diversity, as assessed by rarefaction and phylogenetic diversity, in each feces sample of three groups. Consistent with previously reported data44, we observed that the phylogenetic diversity was changed by diet and that the fecal microbiota of the HFD-fed groups (the fLGG and LGG groups) had lower phylogenetic diversity than that of the RCD group (Fig. 6a). However, the fecal microbiota of the fLGG and LGG groups was not different in phylogenetic diversity, which indicates that L. rhamnosus GG did not affect phylogenetic diversity in the fecal microbiota during short-term HFD feeding (Fig. 6a). Furthermore, we analyzed fecal microbiota composition and intestinal colonization of L. rhamnosus GG using 16S rRNA sequencing of feces after 1 week of HFD or RCD feeding. Similar to previous reports46,47, we found that the proportions of both Firmicutes and Proteobacteria were increased while the proportion of Bacteroidetes decreased in the HFD-fed groups (the fLGG and LGG groups) compared to those in the RCD group at the phylum level (Fig. 6b). At the family level, the proportion of Lactobacillaceae was markedly increased by ~5.6% in the LGG group, while it was almost undetectable in the RCD (~0.3%) and fLGG (~0.9%) groups (Fig. 6b). These data are consistent with our previous report that a single inoculation of L. rhamnosus GG colonized the intestine of mice and was detected in feces for up to 7 days27. Of the Proteobacteria, the LGG group showed an increase in the proportion of Desulfovibrionaceae (Fig. 6b), which has been previously reported to increase under HFD conditions;48 however, the effects on the beneficial results of the LGG group are not clear.

Fig. 6: The effect of L. rhamnosus GG on the gut microbiota during short-term HFD feeding.

a Rarefaction curves plotted for phylogenetic distance between the microbiota of the RCD, fLGG, and LGG groups. Phylogenetic distance was calculated at a rarefaction depth of 12,000 sequences/sample. b Comparison of family-level proportional abundance in the feces of the RCD, fLGG, and LGG groups (pooling, n = 3 per group). The red arrow indicates Lactobacillaceae

Discussion

Intestinal microbiomes are composed of 10 times more microorganisms than the number of cells constituting the human body49. It is not surprising that the metabolism of the microbiome could affect the host's energy metabolism. Since the Jeffrey I. Gordon group published a paper on the discovery of obesity-related changes in the portion of gut bacteria belonging to Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in human and animal50,51,52, many studies have confirmed that there is a notable difference in the intestinal compartment in obese mice compared to that in normal mice, with a significantly higher percentage of bacteria belonging to Firmicutes and a lower percentage to Bacteroidetes47,53. Furthermore, it is reported that normal mice receiving intestinal microflora from obese mice gain more weight than mice receiving intestinal microflora from lean mice even if they consume the same amount of calories50. In a study published in NEJM in 2014, researchers found that mice exposed to antibiotics in childhood become obese as adults, and normal mice become obese when grafted intestinal bacteria are transplanted into normal mice. These results indicate that intestinal microorganisms play an important role in energy accumulation and the development of obesity. Despite these studies over a decade, debate has remained regarding which specific bacteria and whether the increased bacteria have causality or consequence of obesity due to altered intestinal nutrients17,53. In particular, a decrease in Firmicutes has been recently reported in type 1 diabetes models, suggesting that a reduction in certain bacteria involved in fermentation could be a cause54. Furthermore, Bacteroidetes is known to be the major bacterium producing acetate (C2) and propionate (C3) in the intestine, which can induce glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and insulin resistance through activation of the parasympathetic nerve system and lipogenesis55,56. Firmicutes strains are known to produce mainly butyrate (C4), which improves insulin resistance by inhibiting HDAC57,58. Lactobacillus, which was used in this study, belongs to Firmicutes, and it has a characteristic of proliferating well when fatty acids are abundant and even using fatty acids when exposed to an acidic environment, such as small intestine's lumen23 (Fig. 1). Given the other positive features of Lactobacillus for other diseases when used as probiotics, increases in Firmicutes during a HFD, particularly the increase in Lactobacillus, are likely changes secondary to in intestinal lipid alterations rather than causes of obesity, even preventing obesity in the host by using its fatty acid-consuming abilities.

An open key question in probiotics is whether clinical application is able to improve metabolic research in humans. L. rhamnosus GG (LGG), ATCC 53103, was originally isolated from the feces of a healthy subject, and it was identified as a potential probiotic strain due to its resistance to acid and adhesion capacity to the intestinal epithelial layer59. Since then, the beneficial effects of this strain have been studied. However, in human intervention studies, its effects in obesity and related metabolic diseases were mild60,61, and applicable clinical symptoms are not exactly known yet. Since weight loss remains the mainstay of NAFLD treatment62, drugs reducing dietary lipid absorption could be a reasonable approach against hepatic steatosis. However, orlistat, a gastrointestinal lipase inhibitor, has been faced with side effects, such as oily stools and urgent bowel movements63. In this study, we clearly showed that, even under short-term periods, L. rhamnosus GG inhibits intestinal fatty acid absorption and decreases body fat accumulation without increasing fecal lipid excretion, which is a key determinant for the side effect of the orlistat. Mechanistically, it makes sense if gut bacteria consume the excessive intestinal lipids increased by the orlistat, steatorrhea could be improved. Thus, it could be a testable trial whether orlistat’s steatorrhea is decreased with combinational treatment of specific gut bacteria that consume fatty acids from among the probiotics, such as L. rhamnosus GG. More sophisticated lipid tracers that are currently under development may help to quantify energy uptake and identify the mechanism in humans.

Mechanistically, probiotic Lactobacillus strains have been proposed to benefit human health with several general mechanisms of action11,64. First, certain Lactobacillus can directly or indirectly influence the abundance or diversity of the commensal microbiota65. Second, certain Lactobacillus strains have the ability to enhance epithelial barrier function, such as via nuclear factor-κB (NF-kB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent pathways, which are related to the function of mucus or tight junctions in intestinal cells65. Third, most probiotic Lactobacillus strains can also modulate the host’s immune responses and exert local systemic effects specific to the strains66, which are mostly mediated by microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs)67. Last, bacteria produce metabolites from intestinal carbohydrates, amino acids and lipid sources, such as short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), branched amino acids and conjugated linoleic acid27,68. Although many experiments with in vitro and in vivo animal models validate these mechanisms for probiotic strains in general and for L. rhamnosus GG in particular, most published data pay less attention to the characteristic outcome of Lactobacillus in fatty acid absorption. In our knowledge, only one previous study showed that Lactobacillus reuteri JBD301 reduces dietary fat absorption in the intestine and protects against diet-induced obesity under long-term HFD-feeding conditions69, which is consistent with our results in this study. However, their findings for fatty acid absorption were limited to in vitro evidence. Furthermore, it was difficult to distinguish whether host-bacterial fatty acid competition is primary or secondary to the anti-obesity effect of Lactobacillus, since Lactobacillus strains have been known to alter systemic inflammation, gut permeability, and the population of the gut microbiota under chronic HFD feeding conditions12,13,14. In this study, we attempted to dissociate these confounding factors and identify a new role for L. rhamnosus GG in the early progression of NAFLD by using acute HFD-fed and body weight-matched mice. Furthermore, we quantitatively demonstrated a novel mechanism by which L. rhamnosus GG reduces intestinal fatty acid absorption using tracer-labeled [14C]-OA in vivo, which was not associated with gut permeability or systemic inflammation under short-term HFD-feeding conditions. These results provide a novel mechanism by which L. rhamnosus GG consumes intestinal fatty acids and protects against the initial stage of NAFLD development earlier than changes in gut permeability or inflammation in vivo. Additionally, we showed that L. rhamnosus GG reduces body fat gain and protects against lipid-induced hepatic steatosis under long-term HFD-feeding conditions. Together, these data provide an additional and new function of L. rhamnosus GG in competing with the host for intestinal lipid uptake and suggest a therapeutic potency of the most well-known probiotics against diet-induced obesity, NAFLD, and related metabolic diseases.

References

- Cohen, J. C., Horton, J. D. & Hobbs, H. H. Human fatty liver disease: old questions and new insights. Science 332, 1519–1523 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bashiardes, S., Shapiro, H., Rozin, S., Shibolet, O. & Elinav, E. Non-alcoholic fatty liver and the gut microbiota. Mol. Metab. 5, 782–794 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Younossi, Z. M. et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 64, 73–84 (2016).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Ahmed, M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in 2015. World J. Hepatol. 7, 1450–1459 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Sattar, N., Forrest, E. & Preiss, D. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Br. Med. J. 349, g4596 (2014).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Postic, C. & Girard, J. Contribution of de novo fatty acid synthesis to hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance: lessons from genetically engineered mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 829–838 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lee, H. Y. et al. Apolipoprotein CIII overexpressing mice are predisposed to diet-induced hepatic steatosis and hepatic insulin resistance. Hepatology 54, 1650–1660 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Karasov, W. H. & Hume, I. D. in Handbook of Physiology 1st edn, Vol. 1 (ed Dantzler, W. H.) Sec. 13 (Oxford University Press, New York, 1997).

- Sanders, M. E. Probiotics: definition, sources, selection, and uses. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46(Suppl. 2), S58–S61 (2008). discussionS144–151.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Yan, F. & Polk, D. B. Probiotics and immune health. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 27, 496–501 (2011).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Segers, M. E. & Lebeer, S. Towards a better understanding of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG–host interactions. Microb. Cell Fact. 13(Suppl. 1), S7–S7 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kawano, M., Miyoshi, M., Ogawa, A., Sakai, F. & Kadooka, Y. Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 inhibits adipose tissue inflammation and intestinal permeability in mice fed a high-fat diet. J. Nutr. Sci. 5, e23 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar - Ritze, Y. et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG protects against non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. PLoS ONE 9, e80169 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar - Xin, J. et al. Preventing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through Lactobacillus johnsonii BS15 by attenuating inflammation and mitochondrial injury and improving gut environment in obese mice. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 98, 6817–6829 (2014).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ito, M. et al. Longitudinal analysis of murine steatohepatitis model induced by chronic exposure to high-fat diet. Hepatol. Res. 37, 50–57 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Imajo, K. et al. Rodent models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 21833–21857 (2013).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar - Bäckhed, F. et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 15718–15723 (2004).

Article PubMed CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cani, P. D. et al. Microbial regulation of organismal energy homeostasis. Nat. Metab. 1, 34–46 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Berry, E. M. Dietary fatty acids in the management of diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 66, 991s–997s (1997).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Veerkamp, J. H. Fatty acid composition of bifidobacterium and lactobacillus strains. J. Bacteriol. 108, 861–867 (1971).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Polacheck, J. W., Tropp, B. E. & Law, J. H. Biosynthesis of cyclopropane compounds. 8. The conversion of oleate to dihydrosterculate. J. Biol. Chem. 241, 3362–3364 (1966).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Johnsson, T., Nikkila, P., Toivonen, L., Rosenqvist, H. & Laakso, S. Cellular fatty acid profiles of lactobacillus and lactococcus strains in relation to the oleic acid content of the cultivation medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 4497–4499 (1995).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Corcoran, B. M., Stanton, C., Fitzgerald, G. F. & Ross, R. P. Growth of probiotic lactobacilli in the presence of oleic acid enhances subsequent survival in gastric juice. Microbiology 153, 291–299 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - De Man, J. C., Rogosa, M. & Sharpe, M. E. A medium for the cultivation of lactobacilli. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 23, 130–135 (1960).

Article Google Scholar - Yu, C. et al. Mechanism by which fatty acids inhibit insulin activation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1)-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 50230–50236 (2002).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Folch, J., Lees, M. & Sloane Stanley, G. H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497–509 (1957).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lee, H. Y. et al. Human originated bacteria, Lactobacillus rhamnosus PL60, produce conjugated linoleic acid and show anti-obesity effects in diet-induced obese mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 736–744 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Coconnier, M. H., Klaenhammer, T. R., Kerneis, S., Bernet, M. F. & Servin, A. L. Protein-mediated adhesion of Lactobacillus acidophilus BG2FO4 on human enterocyte and mucus-secreting cell lines in culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58, 2034–2039 (1992).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Fang, H. W. et al. Inhibitory effects of Lactobacillus casei subsp. rhamnosus on Salmonella lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and epithelial barrier dysfunction in a co-culture model using Caco-2/peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Med. Microbiol. 59, 573–579 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lee, S. Y. et al. Activation of sphingosine kinase 2 by endoplasmic reticulum stress ameliorates hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in mice. Hepatology 62, 135–146 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kleiner, D. E. et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 41, 1313–1321 (2005).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Lee, H. Y. et al. Targeted expression of catalase to mitochondria prevents age-associated reductions in mitochondrial function and insulin resistance. Cell. Metab. 12, 668–674 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Masella, A. P., Bartram, A. K., Truszkowski, J. M., Brown, D. G. & Neufeld, J. D. PANDAseq: paired-end assembler for illumina sequences. BMC Bioinform. 13, 31 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Schloss, P. D. et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 7537–7541 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S. & Li, W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 3150–3152 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Galbo, T. et al. Saturated and unsaturated fat induce hepatic insulin resistance independently of TLR-4 signaling and ceramide synthesis in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 12780–12785 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Petersen, M. C. & Shulman, G. I. Roles of diacylglycerols and ceramides in hepatic insulin resistance. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 38, 649–665 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hageman, R. S. et al. High-fat diet leads to tissue-specific changes reflecting risk factors for diseases in DBA/2J mice. Physiol. Genom. 42, 55–66 (2010).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Chavez, J. A. & Summers, S. A. A ceramide-centric view of insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 15, 585–594 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Reynoso, R., Salgado, L. M. & Calderon, V. High levels of palmitic acid lead to insulin resistance due to changes in the level of phosphorylation of the insulin receptor and insulin receptor substrate-1. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 246, 155–162 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lee, Y. S. et al. Inflammation is necessary for long-term but not short-term high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes 60, 2474–2483 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cani, P. D. et al. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet–induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 57, 1470–1481 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Daniel, H. et al. High-fat diet alters gut microbiota physiology in mice. ISME J. 8, 295–308 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Gonzalez-Mariscal, L., Betanzos, A., Nava, P. & Jaramillo, B. E. Tight junction proteins. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 81, 1–44 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Alard, J. et al. Beneficial metabolic effects of selected probiotics on diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice are associated with improvement of dysbiotic gut microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 1484–1497 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hildebrandt, M. A. et al. High fat diet determines the composition of the murine gut microbiome independently of obesity. Gastroenterology 137, 1716–1724 (2009). e1711–1712.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zhang, C. et al. Structural resilience of the gut microbiota in adult mice under high-fat dietary perturbations. ISME J. 6, 1848–1857 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yang, X., Xie, L., Li, Y. & Wei, C. More than 9,000,000 unique genes in human gut bacterial community: estimating gene numbers inside a human body. PLoS ONE 4, e6074 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar - Ley, R. E. et al. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11070–11075 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Turnbaugh, P. J. et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444, 1027 (2006).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Ley, R. E., Turnbaugh, P. J., Klein, S. & Gordon, J. I. Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 444, 1022–1023 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Turnbaugh, P. J., Backhed, F., Fulton, L. & Gordon, J. I. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 3, 213–223 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Marino, E. et al. Gut microbial metabolites limit the frequency of autoimmune T cells and protect against type 1 diabetes. Nat. Immunol. 18, 552–562 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Macfarlane, S. & Macfarlane, G. T. Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 62, 67–72 (2007).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Perry, R. J. et al. Acetate mediates a microbiome-brain-beta-cell axis to promote metabolic syndrome. Nature 534, 213–217 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Vrieze, A. et al. Transfer of intestinal microbiota from lean donors increases insulin sensitivity in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Gastroenterology 143, 913–916.e917 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bouter, K. E. C. et al. Differential metabolic effects of oral butyrate treatment in lean versus metabolic syndrome subjects. Clin. Transl. Gastroen. 9, 155 (2018).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Doron, S., Snydman, D. R. & Gorbach, S. L. Lactobacillus GG: bacteriology and clinical applications. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 34, 483–498 (2005). ix.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kadooka, Y. et al. Regulation of abdominal adiposity by probiotics (Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055) in adults with obese tendencies in a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 64, 636 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Vajro, P. et al. Effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG in pediatric obesity-related liver disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 52, 740–743 (2011).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Dixon, J. B., Bhathal, P. S., Hughes, N. R. & O'Brien, P. E. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: improvement in liver histological analysis with weight loss. Hepatology 39, 1647–1654 (2004).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Cavaliere, H., Floriano, I. & Medeiros-Neto, G. Gastrointestinal side effects of orlistat may be prevented by concomitant prescription of natural fibers (psyllium mucilloid). Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 25, 1095–1099 (2001).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lebeer, S., Vanderleyden, J. & De Keersmaecker, S. C. Host interactions of probiotic bacterial surface molecules: comparison with commensals and pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 171–184 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lebeer, S., Vanderleyden, J. & De Keersmaecker, S. C. Genes and molecules of lactobacilli supporting probiotic action. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72, 728–764 (2008). Table of Contents.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wells, J. M. Immunomodulatory mechanisms of lactobacilli. Microb. Cell Fact. 10(Suppl. 1), S17 (2011).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Abreu, M. T. Toll-like receptor signalling in the intestinal epithelium: how bacterial recognition shapes intestinal function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 131–144 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kim, C. H. Immune regulation by microbiome metabolites. Immunology 154, 220–229 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chung, H.-J. et al. Intestinal removal of free fatty acids from hosts by Lactobacilli for the treatment of obesity. FEBS Open Bio 6, 64–76 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank Jae-Sung Lee and Dr. Yeon-Mi Lee (Lee Gil Ya Cancer and Diabetes Institute, Gachon University, Korea) for their excellent technical support and Dr. Shi-Young Park and Dr. Cheol Soo Choi (Korea Mouse Phenotyping Center, Gachon University, Korea) for helpful advice in these studies. These studies were supported by grants from The Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Korea (HI14C1135), and from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2014M3A9D5A01073886, NRF-2017R1A2B4009936, and NRF-2018M3A9F3056405).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Laboratory of Mitochondrial and Metabolic Diseases, Department of Health Sciences and Technology, GAIHST, Gachon University, Incheon, Korea

Hye Rim Jang, Hyun-Jun Park, Dongwon Kang & Hui-Young Lee - Department of Medicine, Gachon University School of Medicine, Incheon, Korea

Hyun-Jun Park - Seoul Center, Korea Basic Science Institute, Seoul, Korea

Hayung Chung & Myung Hee Nam - Culture Collection of Antimicrobial Resistant Microbes, Department of Horticulture, Biotechnology and Landscape Architecture, Seoul Women’s University, Seoul, Korea

Yeonhee Lee - Korea Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center, Lee Gil Ya Cancer and Diabetes Institute, Gachon University, Incheon, Korea

Jae-Hak Park - Department of Laboratory Animal Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

Hui-Young Lee

Authors

- Hye Rim Jang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hyun-Jun Park

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Dongwon Kang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hayung Chung

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Myung Hee Nam

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yeonhee Lee

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jae-Hak Park

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hui-Young Lee

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Study design: H.R.J., J.-H.P., and H.-Y.L.; performed bacterial and cellular experiments: H.R.J., H.-J.P., and Y.L.; performed mass spectrometry: M.H.N. and H.J.; performed animal experiments: H.R.J., H.-J.P., D.K. and H.-Y.L.; analysis and interpretation of data: H.R.J., M.H.N., Y.L., J.-H.P. and H.-Y.L.; and drafting and finalizing of the manuscript: H.R.J., J.-H.P. and H.-Y.L. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence toJae-Hak Park or Hui-Young Lee.

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jang, H.R., Park, HJ., Kang, D. et al. A protective mechanism of probiotic Lactobacillus against hepatic steatosis via reducing host intestinal fatty acid absorption.Exp Mol Med 51, 1–14 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-019-0293-4

- Received: 17 December 2018

- Revised: 29 March 2019

- Accepted: 16 April 2019

- Published: 13 August 2019

- Issue Date: August 2019

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-019-0293-4