Genetic susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in the genomic era (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 Jul 13.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010 Nov 9;6(12):683–692. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.176

Abstract

Our understanding of the genetic basis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has been rapidly advanced using large-scale, case–control, candidate gene studies as well as genome-wide association studies during the past 3 years. These techniques have identified more than 30 robust genetic associations with SLE including genetic variants of HLA and Fcγ receptor genes, IRF5, STAT4, PTPN22, TNFAIP3, BLK, BANK1, TNFSF4 and ITGAM. Most SLE-associated gene products participate in key pathogenic pathways, including Toll-like receptor and type I interferon signaling pathways, immune regulation pathways and those that control the clearance of immune complexes. Disease-associated loci that have not yet been demonstrated to have important functions in the immune system might provide new clues to the underlying molecular mechanisms that contribute to the pathogenesis or progression of SLE. Of note, genetic risk factors that are shared between SLE and other immune-related diseases highlight common pathways in the pathophysiology of these diseases, and might provide innovative molecular targets for therapeutic interventions.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex auto-immune disease that occurs in genetically-predisposed individuals who have experienced certain environmental or stochastic stimuli. A diagnosis of SLE can be made if an individual fulfills four out of 11 specific criteria; the clinical presentations and autoantibody profiles of patients with SLE can, therefore, vary substantially. Despite phenotypic heterogeneity, a strong genetic contribution to the development of SLE is supported by the high heritability of the disease (>66%), a higher concordance rate for SLE in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins or siblings (24–56% versus 2–5%, respectively), and the high sibling recurrence risk ratio of patients with SLE (between eightfold and 29-fold higher than in the general population).1,2

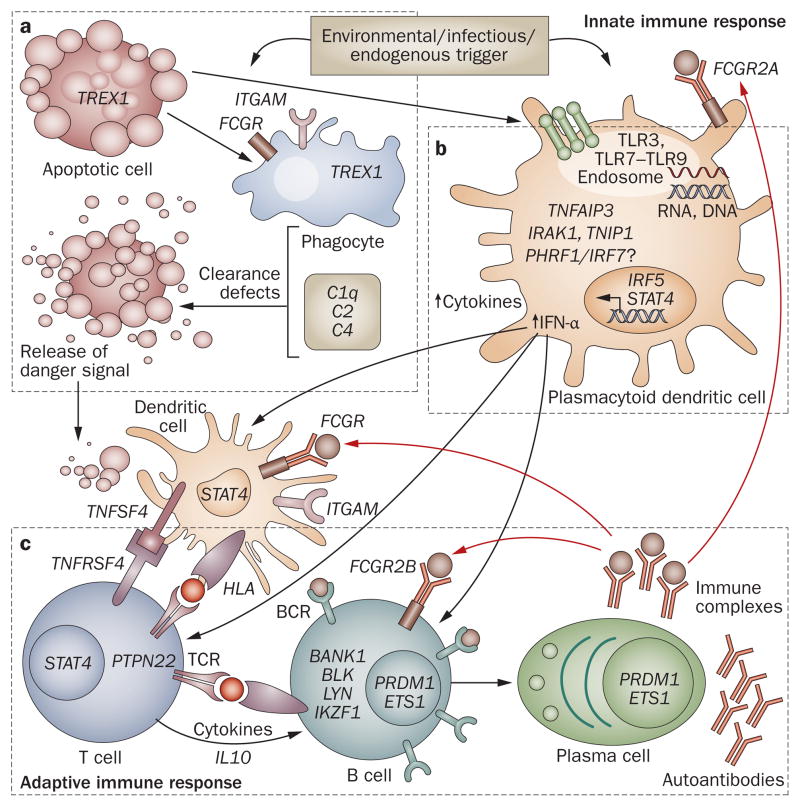

Epidemiologic studies of SLE have led to an increased interest in studying the genetic basis of the disease. Candidate gene case–control studies are commonly used to assess whether a test genetic marker is present at a higher frequency among patients with SLE than in ethnically-matched healthy control individuals. This approach has successfully established that variants of the MHC class II and the Fcγ receptor (FcγR) genes confer predisposition to SLE, as does a deficiency of the complement components C1q, C2 or C4. Candidate genes are chosen on the basis of their functional relevance to disease pathogenesis. A separate unbiased genome-wide linkage analysis approach has also been developed, in which multiallelic microsatellite markers are screened at 10–15 kb genomic intervals to identify chromosomal regions associated with risk that are shared among multiple affected members of a family. A total of 12 genome scans of families with SLE have identified a number of putative susceptibility loci and also contributed to the discovery of new risk genes, such as ITGAM on chromosome 16p11.2.3 However, the utility of linkage studies in precisely localizing causal variants is limited owing to a lack of dense marker sets and an inability to map genetic variants of small phenotypic effect size. Advances in high throughput technology have enabled the genotyping of hundreds of thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in a single individual, which facilitates the mapping of complex disease loci throughout the genome. Six genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in patients with SLE (four in populations of European ancestry and two in Asian populations) have increased the number of established genetic associations with SLE during the past few years (Table 1).4–10 For instance, these studies have identified 18 novel SLE-associated non-HLA loci that reach genome-wide significance, 12 of which have been replicated independently. In addition, candidate gene studies have identified and independently confirmed 13 SLE-associated loci (including HLA loci), most of which are also confirmed in GWAS (Table 1). To visualize how these 31 SLE-associated risk loci might affect both innate and adaptive immune responses leading to the development of disease manifestations, we have developed a working model according to the current understanding of important immunological pathways involved in the pathogenesis of SLE (Figure 1).11–14

Table 1.

SLE risk loci identified through GWAS in various ethnic groups

| Study | Strong evidence (P<5×10–8 Gene (OR)) | Good evidence (P<10–5) Gene (OR) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Established* | Novel‡ | Established* | Novel‡ | |

| European | ||||

| Hom et al.4 | HLA-DR3 (ND)IRF53 (ND)STAT4 (ND) | C8orf13-BLK (1.4) ITGAM-ITGAX (1.3) | NA | NA |

| Harley et al.5 | HLA region (1.4–2.3)IRF5 (1.3–1.6)STAT4 (1.5) | ITGAM (1.3–1.7) PHRF1 (1.3)PXK (1.3)XKR6§ (1.2–1.3) BLK (1.2) LYN (1.3) | PTPN22 (1.5) FCGR2A (1.4) | ATG5 (1.2) UBE2L3 (1.2) SCUBE1 (1.3) |

| Kozyrev et al.6 | NA | BANK1 (1.4) | NA | NA |

| Graham et al.7 | HLA region (ND) IRF53 (ND) STAT4 (1.5) | BLK (1.3)TNFAIP3 (2.3) | NA | ITGAM (ND) |

| Gateva et al.8[| | ](#TFN4) | HLA-DRB1 (2.0) IRF5 (1.9) STAT4 (1.6) PTPN22 (1.4)TNFSF4 (1.2)IL10 (1.2) | ITGAM (1.4)BLK (1.4)TNFAIP3 (1.7) PHRF1 (1.2)TNIP1 (1.3)PRDM1-ATG5 (1.2)JAZF1§ (1.2)UHRF1BP1§ (1.2) | IRAK1-MECP2(1.1) |

| Asian | ||||

| Han et al.9 | HLA region (1.9)IRF5 (1.4)STAT4 (1.5)TNFSF4(1.4–1.5) | BLK (1.3–1.4)PRDM1-ATG5 (1.3)TNFAIP3 (1.7)HIC-UBE2L3 (1.3)IKZF1§ (1.4)RASGRP3§ (1.4) SLC15A4§ (1.3)TNIP1 (1.3)ETS1 (1.4)LRRC18-WDFY4 (1.2) | NA | NA |

| Yang et al.10 | HLA region(1.8–2.0) STAT4 (1.7) | ETS1 (1.3)WDFY4 (1.3) | IRF5 (1.5) | TNFAIP3 (1.9)BLK (1.6) |

Figure 1.

Model of SLE-associated genetic variants in the immune response. This model is derived from current understandings of important immunological pathways involved in SLE pathogenesis, as highlighted by the identified SLE susceptibility loci. a | Processing and clearance of immune complexes. Environmental triggers that induce apoptosis and release of nuclear antigens can stress phagocytes (including macrophages and neutrophils), causing defective clearance of nuclear antigens. b | TLR–IFN signaling. Environmental triggers including ultraviolet light, demethylating drugs and viruses can yield stimulatory DNA or RNA that activates TLRs, resulting in secretion of type I IFN. c | Signal transduction in the adaptive immune response. Presentation of nuclear antigens to dendritic cells leads to the generation of autoantibodies and immune complexes that amplify both innate and adaptive immune responses. Abbreviations: BCR, B-cell receptor; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; TCR, T-cell receptor; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

Individual genetic risk variants associated with SLE each have a modest magnitude of risk with an odds ratio in the range of 1.1–2.3 (Table 1). However, the genetic risk for SLE involves multiple genes and so the overall genetic risk for SLE is higher than in many other auto-immune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, Graves disease, multiple sclerosis, and psoriasis.15 GWAS have identified risk loci shared between SLE and other autoimmune disorders (Table 2), implying that common immunological mechanisms exist among some of these disease processes. In this Review, we highlight established and novel genetic risk factors for SLE, the identification of which has revealed new paradigms for the pathogenesis of the disease, and might provide new therapeutic targets for disease management.

Table 2.

SLE risk loci shared with other autoimmune diseases

| Pathway | Gene | Location | Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocyte regulation | |||

| T-cell signaling | HLA class II | 6p21.3 | RA, SSc, Graves disease, IBD, T1D |

| PTPN22* | 1p13 | RA, T1D, SSc, Graves disease, Crohn’s disease | |

| TNFSF4 | 1q25 | SSc | |

| B-cell signaling | BANK1* | 4q24 | SSc, RA |

| BLK* | 8p23 | SSc, pAPS | |

| Intergenic (PRDM1) | 6q21 | RA, Crohn’s disease | |

| Intergenic(IKZF1) | 7p12 | Crohn’s disease | |

| Innate immune regulation | |||

| TLR–IFN signaling | IRF5 | 7q32 | RA, IBD, SSc |

| STAT4* | 2q33 | RA, SS, SSc | |

| TNF–NFκB signaling | TNFAIP3 | 6q23 | RA, T1D, psoriasis, celiac disease |

| TNIP1 | 5q33 | Psoriasis | |

| Immune complex clearance | |||

| Phagocytic | FCGR2A* | 1q23 | T1D, UC |

| Cytokine regulation | |||

| Anti-in3ammatory | IL10* | 1q31–q32 | UC, T1D |

HLA genes in SLE

The first genetic association described for SLE was with the HLA region at chromosome 6p21.3, which encodes over 200 genes, many with known immunological roles.16,17 The HLA region is subdivided into the class I and class II regions, which contain genes encoding glycoproteins that process and present peptides for recognition by T cells, and the class III region containing other important immune genes (such as TNF, C2, C4A, C4B and CFB). GWAS in both European and Asian populations have shown that the strongest contribution to risk for SLE resides in the HLA region and consists of multiple genetic effects.4,5,7–10 The long-range linkage disequilibrium (LD) within the HLA region has made assessing the relative contribution of each component gene to disease susceptibility difficult; however, the available evidence suggests that genetic variants of HLA class II (such as HLA-DR2 and HLA-DR3) and class III (such as MSH5 and SKIV2L) genes, in particular, predispose an individual to SLE.

HLA class II region genes

The HLA-DR2 (DRB1*1501) and HLA-DR3 (DRB1*0301) class II genes have been found to consistently associate with SLE in many European populations, with a twofold relative risk conferred by each allele.18 The extended HLA haplotype, for example HLA-A1, B8, C4AQ0, C4B1, DR3, and DQ2, containing two class III gene alleles (C4AQ0 and the TNF –308A allele) is considered a common European haplotype implicated in SLE susceptibility. Using genotypes of almost 100 microsatellite HLA markers, three individual haplotypes—DRB1*1501(DR2)-DQB1*0602, DRB1*0801(DR8)-DQB1*0402, and _DRB1*0301(DR3)-DQB1*0201_—have been identified to associate with SLE susceptibility.19 In the study that found these associations, both the class I and class III regions (which include TNF, C2, C4A and C4B) might have been excluded from the critical risk region (~500 kb) of the DRB1*1501 extended haplotype.19 The long-range LD of the _DRB1*0301_-containing haplotype reduces ancestral recombinants (when one portion of the genome is inherited from one individual and the other portion from another individual), resulting in a ~1 Mb critical genomic segment of most class II and class III regions. The risk interval of the DRB1*0801 haplotype, which is less common in Europeans than in Hispanics, has been narrowed to ~500 kb. In addition to European populations, the associations between SLE susceptibility and HLA-DR2 and HLA-DR3 have been confirmed in Asian populations.20–22 Furthermore, the role of SLE-associated HLA class II alleles in initiating SLE-relevant autoantibody responses has been demonstrated in humanized mice expressing the HLA-DR3 transgene but not other DR or DQ alleles.23

HLA class III region genes

Complete deficiencies of C2 or C4 are rare and are associated with a high risk of developing SLE.24 Over 75% of patients with _C4_-deficiency and about 20% of those with _C2_-deficiency develop SLE or a lupus-like disease.25,26 C4A and C4B code for complement C4-A and complement C4-B proteins, respectively, which have different functional characteristics; complement C4-A has a higher affinity for immune complexes (ICs) and stronger genetic evidence for an association with SLE than complement C4-B.27,28 The C4A null allele (deficiency of C4A), is associated with SLE susceptibility in multiple ethnic groups, including European and East Asian populations.29 Healthy European Americans exhibit copy number variations (CNVs) of total C4 that range from two to six gene copies; decreases in C4A (but not C4B) copy number predisposes to developing SLE while having three or more copies of C4A protects against SLE.30 CNVs of C4 genes determine the basal levels of circulating complement C4 proteins that function in the clearance of ICs, which can otherwise promote autoimmunity. A functional SNP in the promoter region of TNF (–308G>A), which is located ~400 kb telomeric to the C4 genes in the HLA class III region, has been associated with SLE susceptibility in some studies, but was excluded as an independent risk factor in family-based association studies from the UK31 and USA.30 Of interest, the UK study showed that a novel HLA class III locus, SKIV2L (also known as SKI2W; an RNA helicase gene that is located 11.3 kb upstream of C4A32), is associated with SLE independent of class II loci.31 Another SNP (rs3131379) in the HLA class III locus MSH5 exhibited the highest SLE-associated signal in a GWAS conducted in 2008.5 Furthermore, a study that screened the MHC genomic region of 1,610 European-derived patients with SLE (and 1,470 of their parents) for 1,974 high-density SNPs identified multiple independent loci associated with SLE, including DRB1*0301, DRB1*1401, DRB1*1501 and the DQB2 alleles, CREBL1, MICB and OR2H2.33 Overall, these studies highlight the important contributions of HLA class III genes to SLE susceptibility. In the future, the collection of samples from multiple ethnic groups might permit the mapping of a wide range of populations in order to overcome long-range LD among MHC loci, thereby facilitating the identification of multiple independent functional variants predisposing to SLE susceptibility.

Non-HLA genes in SLE

During the past few years, technological advances and collaboration among investigators have enabled GWAS to be performed using a combination of European and Asian populations with SLE. The genetic associations identified in these studies highlight major SLE susceptibility genes common to multiple ethnic populations. This approach facilitates the localization of causal variants on the basis of population differences in LD of the genetic markers and the putative casual variants (Supplementary Table 1 online). Results from these studies not only confirmed the importance of several non-HLA loci previously implicated in the disease, but also identified a number of novel genes, some of which encode proteins that function in various aspects of the immune system, while others have no known relationship to the pathogenesis of SLE.

IRF5

Interferon (IFN) regulatory factor 5 (IRF5; encoded by IRF5)—a pivotal transcription factor in the type I IFN pathway (Figure 1b)—regulates the expression of IFN-dependent genes, inflammatory cytokines and genes involved in apoptosis. IRF5 is one of the most strongly and consistently SLE-associated loci outside the MHC region and was detected using both candidate gene and GWAS approaches (Table 1). Association studies derived from multiple ethnic groups have identified four functional IRF5 variants: a 5 bp indel (insertion–deletion) near the 5′ untranslated region (UTR), rs2004640 in the first intron, a 30 bp indel in the sixth exon and rs10954213 in the 3′ UTR.34–42 The haplotypes defined by different combinations of these SNPs are associated with increased, decreased, or neutral levels of risk for SLE. Increased risk haplotypes are associated with functional changes in IRF5-mediated signaling, including increased expression of IRF5 mRNA and interferon-inducible chemokines, as well as elevated α activity.43,44 Indeed, IRF5 is necessary for the development of lupus-like disease in mice, as was demonstrated using _Irf5_-deficient mice and Irf5-sufficient FcγRIIB−/−Yaa mice, implying a role for IRF5 in mediating SLE pathogenesis through pathways beyond type I IFN production.45

STAT4

STAT4 encodes the signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 protein (STAT4) and has been found to associate with SLE in multiple GWAS using populations of European or Asian ancestry (Table 1). As in previous candidate gene studies, the minor T allele of rs7574865, in the third intron of STAT4, is strongly associated with SLE with an odds ratio of 1.5–1.7.5,7–10,46–49 Interestingly, this rs7574865 risk variant is associated with a more- severe SLE phenotype that is characterized by disease-onset at a young age (<30 years), a high frequency of nephritis, the presence of antibodies towards double-stranded DNA,47,49,50 and an increased sensitivity to IFN-α signaling in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.51 Studies to identify causal variants of STAT4 led to the discovery of several markers that are independently associated with SLE and/or with differential levels of STAT4 expression;50,52,53 a risk haplotype (spanning 73 kb from the third intron to the seventeenth exon of STAT4) common to European Americans, Koreans and Hispanic Americans was also identified.53 Functionally, either type I IFN or interleukin (IL)-12 induces phosphoryla-tion of STAT4, which has a signal transduction role in these pathways. Individuals carrying one or more risk alleles of both IRF5 and STAT4 have an increased risk for SLE, suggesting a genetic interaction between these two genes (Figure 1b).50

PTPN22

PTPN22 encodes tyrosine-protein phosphatase non- receptor type 22 (PTPN22), a lymphoid-specific phosphatase that inhibits T-cell activation (Figure 1c).54 The nonsynonymous SNP rs2476601 (Arg620Trp) is associated with a risk of developing multiple auto-immune diseases including SLE,55 providing evidence for shared mechanisms between these diseases despite differences in disease manifestations. GWAS of SLE have confirmed the association between rs2476601 and SLE in European-derived populations,5,8 but not in Asian-derived populations,9,10 possibly attributable to greater variability in allele frequencies in European populations (2–15%).55 The Arg620Trp substitution increases the intrinsic lymphoid-specific phosphatase activity of PTPN22, which reduces the threshold for T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling and promotes autoimmunity.56 By contrast, a PTPN22 variant (Arg263Gln in the catalytic domain) that reduces the phosphatase activity of PTPN22 and, therefore, increases the threshold for TCR signaling has been associated with protection against SLE in European-derived populations.57 A connection between PTPN22 and the type I IFN pathway has been suggested on the basis of elevated serum IFN-α activity and decreased tumor necrosis factor (TNF) levels in patients with SLE carrying the rs2476601 risk allele.58

FcγR genes

FCGR2A, FCGR3A, FCGR3B, and FCGR2B encode FcγRs (low-affinity Fcγ receptors for IgG), which recognize ICs (Figure 1a) and are involved in antibody-dependent responses (Figure 1c). Various functional variants of these genes have been identified as risk factors for SLE. The nonsynonymous SNP rs1801274 (His131Arg) of FCGR2A is associated with a low affinity for IgG2-opsonized particles (by contrast, His131 is associated with a high affinity for these particles), and reduced clearance of ICs.59 However, rs1801274 showed inconsistent association with susceptibility to SLE or lupus nephritis, or both, in various ethnic groups including Europeans, African Americans and Koreans.60–64 Ethnic differences, disease heterogeneity, genotyping error (owing to extensive sequence homo logy among FcγR genes) and random fluctuations in small samples might explain these inconsistent associations. A GWAS conducted in 2008 confirmed the association of rs1801274 with SLE in women of European descent.5

A nonsynonymous SNP in FCGR3A (rs396991; Phe158Val or Phe176Val if the leader sequence is included) alters the binding affinities of the encoded receptor for ICs containing IgG1, IgG3 or IgG4. The low-affinity phenylalanine allele that confers less-efficient clearance of ICs than other alleles was associated with SLE susceptibility,65 but, in patients with SLE and renal involvement, the high-affinity valine allele was associated with progression to end-stage renal disease.66 Since IgG2 and IgG3 are major subclasses of ICs deposited in renal biopsy samples of patients with lupus nephritis,67 the relative importance of _FCGR2A_-H/R131 and _FCGR3A_-V/F158 to disease progression might depend on the IgG subclass of pathogenic autoantibodies in an individual patient. Because these alleles are often inherited together,68 the presence of multiple risk alleles might interact to enhance the risk for SLE.69

A nonsynonymous SNP in the transmembrane domain of FCGR2B (Ile187Thr) that alters the inhibitory function of FcγRIIb on B cells is associated with SLE in Asian populations,70–72 but not in European Americans, African Americans or Swedish populations partly owing to their low allele frequencies.73–75 The FcγRIIb encoded by the Thr187 allele is excluded from lipid rafts, which results in impaired inhibition of B-cell activation and promotes autoimmunity.76 A promoter haplotype (–386G/–120T) that confers increased transcription of FCGR2B is associated with SLE in European Americans.77

Six SNPs exist in FCRG3B, underlying three different allotypic variants of FcγRIIIb (NA1, NA2 and SH). NA1 and NA2 differ in four amino acid positions including two potential glycosylation sites, resulting in a decreased capacity to mediate phagocytosis in individuals homozygous for NA2.78 Although Hatta et al.79 reported an association between the NA2 allotype and SLE in a Japanese population, this observation has not been replicated, suggesting that the association between SLE and this genomic region might be influenced by other genetic variations. Both duplication and deficiency of FCGR3B were reported in normal individuals, demonstrating CNVs in general populations.80,81 A low copy number of FCGR3B is associated with a decrease in protein expression, IC uptake and neutrophil adhesion to ICs,82 which might explain why individuals with fewer than two copies of FCGR3B have a higher risk for SLE (with or without nephritis). An integrated approach to simultaneously assess CNVs, allotypic variants, and SNPs in large-scale case–control studies including multiple ethnic populations is needed to dissect the relative contribution of various variants in this complex FCGR locus to SLE.

C1q genes

The complement system, through opsonization, facilitates the clearance of apoptotic debris and cellular fragments that might contain nuclear antigens, which are targets for SLE-associated autoantibodies. Complement component 1q (C1q; encoded by C1QA, C1QB and C1QC) is part of the classical pathway of complement activation, and, together with the enzymatically active components C1r and C1s, forms the C1 complex. Complete deficiency of C1q, although rare, is a powerful SLE risk factor and >90% of individuals with this deficiency develop SLE or lupus-like manifestations.83 In addition, a synonymous SNP of C1QA (rs172378), of which allele A is linked to decreased levels of serum C1q, is associated with subacute cutaneous lupus.84 Other SNPs in the C1q genes are also associated with subphenotypes of SLE (such as lupus nephritis and photosensitivity) in African American and Hispanic populations.85 The pathogenic mechanism in these cases is thought to be defective IC clearance (Figure 1a). However, studies have found that C1q has a regulatory effect on cytokine production induced by Toll-like receptors (TLRs),86 as well as IC-induced IFN-α production,87 providing additional explanations for the elevated risk for SLE associated with C1q-deficiency.

The IRAK1-MECP2 region

IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1; encoded by IRAK1), a serine–threonine protein kinase, regulates multiple pathways in both innate and adaptive immune responses by linking several immune-receptor-complexes to TNF receptor-associated factor 6.88 In mouse models of lupus, Irak1 is shown to regulate nuclear factor κ B (NFκB) in TCR signaling and TLR activation, as well as the induction of IFN-α and IFN-γ (Figure 1b),89 implicating IRAK1 in SLE. In a study of four different ethnic groups, multiple SNPs within IRAK1 were associated with both adult-onset and childhood-onset SLE.89

Another potential risk gene for SLE, methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2), located in a region of LD with IRAK1, has a critical role in the transcriptional suppression of methylation-sensitive genes.90 A large replication study in a European-derived population confirmed the importance of this region (IRAK1–MECP2) to SLE, although further work is required to identify the causal variants.7 The location of IRAK1 and MECP2 on the X chromosome raises the possibility that gender bias of SLE might, in part, be attributed to sex chromosome genes.

TREX1

TREX1 encodes 3′ repair exonuclease 1, a major 3′–5′ DNA exonuclease. This enzyme proofreads DNA polymerase and potentially also functions as a DNA-degrading enzyme in granzyme-A-mediated apoptosis and as a cytosolic DNA sensor (Figure 1a).91 _TREX1_-deficiency impairs DNA damage repair, leading to the accumulation of endogenous retroelement-derived DNA. Defective clearance of this DNA induces IFN production and an immune-mediated inflammatory response, promoting systemic autoimmunity. A study of populations from the UK, Germany and Finland reported mono-allelic frameshift or missense mutations and a single 3′ UTR variant of TREX1 present in patients with SLE, all of which were absent in controls.92 Another study identified several novel mutations of TREX1 in patients with Aicardi–Goutieres syndrome, which shares several common features with SLE.93 Although rare, the association of TREX1 with SLE indicates a role for the defective clearance of damaged DNA in the activation of innate immunity and the development of SLE.

TNFSF4

TNF ligand superfamily member 4 (also known as OX40L; encoded by TNFSF4) and its receptor, TNF receptor superfamily member 4 (OX40L receptor), are expressed on antigen-presenting cells and activated T cells, respectively (Figure 1c). Their interaction induces the production of co-stimulatory signals to activate T cells. OX40L-mediated signaling inhibits the generation and function of IL-10-producing CD4+ type 1 regulatory T cells, but induces B-cell activation and differentiation, as well as IL-17 production.94,95 A study using both case–control and family-based European-derived samples identified a SLE risk haplotype marked by a series of tagging SNPs in the upstream region of TNFSF4, which correlates with increased expression of OX40L.96 Increased OX40L levels are thought to predispose to SLE either by augmenting the interaction between T cells and antigen-presenting cells, or by influencing the functional consequences of T-cell activation via the OX40L receptor.96 Associations between some _TNFSF4_-tagging SNPs and an increased risk for SLE have been confirmed in GWAS in Chinese populations and in a European replication study;8,9 these results were replicated in four independent SLE datasets from Germany, Italy, Spain and Argentina.97 However, further studies are needed to localize causal variants and to understand how these polymorphisms affect the pathogenesis of SLE.

IL10

IL10 encodes IL-10, an important regulatory cytokine with both immunosuppressive and immunostimulatory properties (Figure 1c). Increased IL-10 production by peripheral blood B cells and monocytes from patients with SLE is known to correlate with disease activity,98 demon strating that IL-10 has an important role in the pathogenesis of SLE. A study of the molecular mechanisms underlying this increase in IL-10 production led to the identification of IL10 haplotypes (defined by three SNPs in the IL10 promoter region) that associate with the levels of IL-10 that are secreted.99 Associations between these IL10 SNPs and SLE susceptibility have been reported in European, Hispanic American and Asian populations.100–102 A large-scale replication study in populations from the USA and Sweden has confirmed IL10 as a SLE susceptibility locus.8

Novel genetic associations with SLE

Regulators of type I IFN and NFκB

Activated type I IFN and NFκB signaling pathways in patients with SLE indicate their importance in the pathogenesis of this disease.103,104 GWAS have identified multiple novel genes that impact on these pathways associated with SLE, in addition to IRF5 and STAT4 (both of which are established SLE-associated genes).

TNFAIP3 and TNIP1

TNF-α-induced-protein 3 (encoded by TNFAIP3) and its interacting protein, TNFAIP3-interacting protein 1 (encoded by TNIP1), are both key regulators of the NFκB signaling pathway (Figure 1b), and modulate cell activation, cytokine signaling and apoptosis.105 The association between SLE and SNPs spanning TNFAIP3 was identified through a GWAS of European-derived populations,7 and subsequently confirmed by GWAS in Asian populations.8,9 The strongest association with SLE was observed at rs5029939.7 Another SLE-associated SNP (rs2230926; located in the third exon of TNFAIP3) identified in Europeans has also been found in Japanese populations.106 TNIP1 was identified as a novel SLE susceptibility locus in a Chinese GWAS of SLE9 and this finding has been replicated in a European-derived population.7 These findings highlight the importance of the regulation of NF-κB signaling pathways in the pathogenesis of SLE.

PHRF1

Two GWAS in European populations reported a SLE-associated SNP (rs4963128) in PHRF1 (also known as KIAA1542), a gene that encodes an elongation factor. The genetic association with SLE might be attributable to its close proximity with IRF7, a gene involved in type I IFN signaling (Figure 1b).4 In addition, one study indicated an association of the IRF7–PHRF1 risk allele and SLE-associated autoantibodies with elevated IFN-α activity in serum samples from patients with SLE, implicating IRF7 rather than PHRF1 in the pathogenesis of SLE.107

Regulators of lymphocytes

GWAS have identified SLE-associated signals associated with a number of novel genes that regulate the differentiation, activation or function of various lymphocytes, including T cells, B cells and dendritic cells.

BLK, BANK1 and LYN

BLK encodes tyrosine-protein kinase Blk, a member of the Src family of kinases, which mediates intra-cellular signaling and influences the proliferation, differentiation and tolerance of B cells (Figure 1c).108 A GWAS in European-derived populations identified a SNP (rs13277113; located within the intergenic region between FAM167A and BLK), of which allele A is associated with reduced expression of BLK but increased expression of FAM167A in patients with SLE.4 Another BLK SNP, located 43 kb downstream of rs13277113, is also associated with SLE;5 both SNPs have subsequently been confirmed as SLE-associated in Chinese10,109 and Japanese110 populations.

B-cell scaffold protein with ankyrin repeats (encoded by BANK1), a B-cell adaptor protein, regulates direct coupling between the Src family of tyrosine kinases and the calcium channel IP3R, and facilitates the release of intracellular calcium, altering the B-cell activation threshold.111 Tyrosine-protein kinase Lyn (encoded by LYN) mediates B-cell activation by phosphorylating the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif of the B-cell-receptor-associated Igα/β signaling molecules, or mediates B-cell inhibition by phosphorylating inhibitory receptors such as CD22 (Figure 1c). GWAS in European-derived populations have identified associations of BANK1 and LYN with susceptibility to SLE.5,6 Three functional variants of BANK1 with either a nonsynonymous SNP (rs10516487; Arg61His), a branch point-site SNP (rs17266594; located in an intron) or a SNP in the ankyrin domain (rs3733197; Ala383Thr) might contribute to the sustained activation of B-cell receptors and the subsequent B-cell hyperactivity that is commonly observed in SLE.6 With the exception of the rs10516487 SNP of BANK1, which showed a weak association with SLE in an Asian GWAS, the remaining SNPs of BANK1 and LYN have not been confirmed in either Chinese or Asian GWAS, partly owing to the low frequencies of the SNPs in these populations.9,10

ETS1 and PRDM1

ETS1 encodes ETS1 protein, a member of the ETS family of transcription factors, which negatively regulates the differentiation of B cells and type 17 T-helper cells. ETS1 protein regulates these cells by inhibiting the function of PR domain zinc finger protein 1 (encoded by PRDM1, also known as BLIMP1), an important transcription factor in plasma cells (Figure 1c).112,113 PRDM1 has been identified as a risk locus for SLE by GWAS in both European and Asian populations.8,9 A GWAS in a Chinese Han population identified ETS1 as a novel SLE susceptibility locus,9 an association that was confirmed in a separate GWAS conducted in an Asian population.10 Allele A of the ETS1 variant (rs1128334; located in the 3′ UTR), which is associated with decreased ETS1 expression levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from normal healthy controls, confers an increase in the risk of developing SLE.10 An important role for ETS1 in the pathogenesis of SLE was demonstrated using _Ets1_-deficient mice that developed a lupus-like disease characterized by high titers of autoantibodies and local activation of complement.114

IKZF1

DNA-binding protein Ikaros (encoded by IKZF1) is a lymphoid-restricted zinc finger transcription factor that regulates lymphocyte differentiation and proliferation, as well as self-tolerance through regulation of B-cell-receptor signaling (Figure 1c).115 Data derived from both GWAS and large replication studies identified IKZF1 as a novel SLE susceptibility locus in a Chinese population,9 and as a strong candidate locus in European-derived populations.8

Genes involved in immune complex clearance

Identification of SLE-associated genetic variants at loci related to IC clearance highlights the importance of this process in SLE pathogenesis. ITGAM encodes integrin alpha-M (also known as CD11b or complement receptor 3), the α-chain of the aMβ2 integrin. This integrin adhesion molecule binds the complement cleavage fragment of C3b, and also a myriad of other ligands that are potentially relevant to SLE (Figure 1a).116 Associations between SLE susceptibility and ITGAM or the ITGAM-ITGAX region were found independently in two European GWAS.4,5 Consistent with these results, a fine-mapping study showed that a nonsynonymous variant (rs1143679; Arg77His), with an effect on structural and functional changes of integrin aM, contributed to SLE susceptibility.3 In a subsequent meta-analysis, the SNP showed a frequency of 9–11% in Americans of European, Hispanic or African descent, as well as in Mexican and Colombian populations, and displayed a robust association with SLE in these populations.117 The low frequency of this risk allele in Asian populations might contribute to the lack of its association with SLE in Korean and Japanese populations;117 indeed, this hypothesis has been confirmed in large populations of Hong Kong Chinese and Thai individuals.118

Other genes associated with SLE

GWAS have identified many novel loci involved in the pathogenesis of SLE, although some loci have not yet been fully characterized or have no obvious connection to known SLE pathways. Studies in European populations showed SLE-associated markers in the genomic regions containing PXK, XKR6, JAZF1 and UHRF1BP1.5,8 GWAS in Asian populations identified different susceptibility loci including RASGRP3 and WDFY4.9,10 Interestingly, several novel loci such as SLC15A4 and UBE2L3 reach genome-wide significance for association with SLE in Asian, but not European, populations. Whether or not these findings reflect ethnic variations requires further study. The mechanisms by which these genes increase the risk for SLE are unknown, although some (such as UBE2L3 and RASGRP3) might regulate immune responses.

Conclusions

In this Review, important advances in the identification of genetic variations that predispose to SLE are summarized. In addition to common gene variants explored in GWAS, rare risk variants (such as TREX1 and C1Q) and CNVs (such as for C4 and FCGR3B) are thought to contribute to SLE. Future advances in deep-sequencing technology and bioinformatics will identify more rare variants and define further CNVs. Results from these studies provide information on the unique and overlapping genetic variants in SLE and in related autoimmune diseases, which reveals underlying disease-specific and common pathways. We expect that these genetic insights will help to provide personalized treatment for patients with SLE in the near future (Box 1). For example, an IFN-α antagonist might be a useful therapeutic agent for patients harboring a cluster of susceptibility variants involved in the IFN pathway. Patients carrying the SLE susceptibility variants of ITGAM and STAT4 frequently have lupus nephritis and a severe disease course, which suggests that genetic risk variants might also help to predict disease severity. Overall, the findings discussed in this Review improve our understanding of disease pathogenesis and highlight new molecular pathways that lead to disease manifestations.

Box 1. Future directions of GWAS.

- GWAS have identified genetic risk loci for complex human diseases and marked the start of a new era of genetic research

- Despite these discoveries, newly identified loci from GWAS only account for a minor proportion of the overall genetic component of disease risk, which brings new challenges to this area of research

- Published GWAS that use the commercial genotyping arrays mainly target common single nucleotide polymorphisms, which can result in other types of polymorphisms, such as structural variants in copy numbers or repeat elements, being overlooked

- Advances in deep-sequencing technologies will help to complete a more comprehensive list of genetic risk factors for complex disease in the near future

- Genetic findings from GWAS will be placed into a functional context and will help to uncover the underlying mechanisms of disease susceptibility

- The translation of genetic knowledge into clinical management to improve personalized treatment options is important

Abbreviation: GWAS, genome-wide association studies

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Data

Key points.

- Innovations in genotyping technology such as candidate gene studies and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have advanced our understanding of the genetic basis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- GWAS and candidate gene studies using both European and Asian populations identified and confirmed more than 30 robust SLE susceptibility loci

- Genetic associations identified in various ethnic groups not only highlight major SLE susceptibility genes that are common to multiple ethnic populations, but also indicate those loci with population-specific effects

- Most SLE-associated gene products participate in key pathways involved in the disease pathogenesis and genetic risk factors that are shared between autoimmune diseases can help to identify common disease pathways

- Novel SLE risk loci can reveal new paradigms for the pathogenesis of the disease, and might provide new therapeutic targets for disease management

Review criteria.

This Review is based on peer-reviewed, full-text articles published in English-language journals between 1986 and 2010. The MEDLINE database was searched using combinations of the following keywords: “systemic lupus erythematosus”, “genetics”, “GWAS”, “polymorphism”, “risk factors”, “genetic variation” and “susceptibility”. Further papers were identified by searching the reference lists of the selected articles.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Both authors contributed equally to researching data for the article, providing a substantial contribution to discussions of the content, writing the article and to review and/or editing of the manuscript before submission.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Deapen D, et al. A revised estimate of twin concordance in SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:311–318. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alarcón-Segovia D, et al. Familial aggregation of systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and other autoimmune diseases in 1,177 lupus patients from the GLADEL cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1138–1147. doi: 10.1002/art.20999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nath SK, et al. A nonsynonymous functional variant in integrin-alpha(M) (encoded by ITGAM) is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:152–154. doi: 10.1038/ng.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hom G, et al. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus with C8orf13-BLK and ITGAM-ITGAX. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:900–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harley JB, et al. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nat Genet. 2008;40:204–210. doi: 10.1038/ng.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozyrev SV, et al. Functional variants in the B-cell gene BANK1 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:211–216. doi: 10.1038/ng.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham RR, et al. Genetic variants near TNFAIP3 on 6q23 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1059–1061. doi: 10.1038/ng.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gateva V, et al. A large-scale replication study identifies TNIP1, PRDM1, JAZF1, UHRF1BP1 and IL10 as risk loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1228–1233. doi: 10.1038/ng.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han JW, et al. Genome-wide association study in a Chinese Han population identifies nine new susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1234–1237. doi: 10.1038/ng.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang W, et al. Genome-wide association study in Asian populations identifies variants in ETS1 and WDFY4 associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moser KL, Kelly JA, Lessard CJ, Harley JB. Recent insights into the genetic basis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes Immun. 2009;10:373–379. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harley IT, Kaufman KM, Langefeld CD, Harley JB, Kelly JA. Genetic susceptibility to SLE: new insights from fine mapping and genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:285–290. doi: 10.1038/nrg2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhodes B, Vyse TJ. The genetics of SLE: an update in the light of genome-wide association studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1603–1611. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crow MK. Collaboration, genetic associations, and lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:956–961. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0800096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vyse TJ, Todd JA. Genetic analysis of autoimmune disease. Cell. 1996;85:311–318. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg MA, Arnett FC, Bias WB, Shulman LE. Histocompatibility antigens in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1976;19:129–132. doi: 10.1002/art.1780190201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The MHC sequencing consortium. Complete sequence and gene map of a human major histocompatibility complex. Nature. 1999;401:921–923. doi: 10.1038/44853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsao BP. In: Dubois’ Lupus Erythematosus. 6. Wallace DJ, Hahn BH, editors. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2002. pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham RR, et al. Visualizing human leukocyte antigen class II risk haplotypes in human systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:543–553. doi: 10.1086/342290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doherty DG, et al. Major histocompatibility complex genes and susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in southern Chinese. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:641–646. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong GH, et al. Association of complement C4 and HLA-DR alleles with systemic lupus erythematosus in Koreans. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:442–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee HS, et al. Independent association of HLA-DR and Fcγ receptor polymorphisms in Korean patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:1501–1507. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang C, et al. Differential responses to Smith D autoantigen by mice with HLA-DR and HLA-DQ transgenes: dominant responses by HLA-DR3 transgenic mice with diversification of autoantibodies to small nuclear ribonucleoprotein, double-stranded DNA, and nuclear antigens. J Immunol. 2010;184:1085–1091. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walport MJ. Complement. Second of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1140–1144. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu YL, Hauptmann G, Viguier M, Yu CY. Molecular basis of complete complement C4 deficiency in two North-African families with systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes Immun. 2009;10:433–445. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Truedsson L, Bengtsson AA, Sturfelt G. Complement deficiencies and systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity. 2007;40:560–566. doi: 10.1080/08916930701510673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schifferli JA, Steiger G, Paccaud JP, Sjöholm AG, Hauptmann G. Difference in the biological properties of the two forms of the fourth component of human complement (C4) Clin Exp Immunol. 1986;63:473–477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blanchong CA, et al. Genetic, structural and functional diversities of human complement components C4A and C4B and their mouse homologs, Slp and C4. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:365–392. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pickering MC, Walport MJ. Links between complement abnormalities and systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:133–141. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Y, et al. Gene copy-number variation and associated polymorphisms of complement component C4 in human systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): low copy number is a risk factor for and high copy number is a protective factor against SLE susceptibility in European Americans. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:1037–1054. doi: 10.1086/518257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernando MM, et al. Identification of two independent risk factors for lupus within the MHC in United Kingdom families. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Z, Shen L, Dangel AW, Wu LC, Yu CY. Four ubiquitously expressed genes, RD(D6S45)–SKI2W(SKIV2L)–DOM3Z–RP1(D6S60E), are present between complement component genes factor B and C4 in the class III region of the HLA. Genomics. 1998;53:338–347. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barcellos LF, et al. High-density SNP screening of the major histocompatibility complex in systemic lupus erythematosus demonstrates strong evidence for independent susceptibility regions. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graham RR, et al. A common haplotype of interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) regulates splicing and expression and is associated with increased risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2006;38:550–555. doi: 10.1038/ng1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graham RR, et al. Three functional variants of IFN regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) define risk and protective haplotypes for human lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6758–6763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701266104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sigurdsson S, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of the genetic variants of interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) reveals a novel 5 bp length polymorphism as strong risk factor for systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:872–881. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demirci FY, et al. Association of a common interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) variant with increased risk of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Ann Hum Genet. 2007;71:308–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin HD, et al. Replication of the genetic effects of IFN regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) on systemic lupus erythematosus in a Korean population. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R32. doi: 10.1186/ar2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawasaki A, et al. Association of IRF5 polymorphisms with systemic lupus erythematosus in a Japanese population: support for a crucial role of intron 1 polymorphisms. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:826–834. doi: 10.1002/art.23216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siu HO, et al. Association of a haplotype of IRF5 gene with systemic lupus erythematosus in Chinese. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:360–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelly JA, et al. Interferon regulatory factor-5 is genetically associated with systemic lupus erythematosus in African Americans. Genes Immun. 2008;9:187–194. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Löfgren SE, et al. Promoter insertion/deletion in the IRF5 gene is highly associated with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in distinct populations, but exerts a modest effect on gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:574–578. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niewold TB, et al. Association of the IRF5 risk haplotype with high serum interferon-α activity in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2481–2487. doi: 10.1002/art.23613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rullo OJ, et al. Association of IRF5 polymorphisms with activation of the interferon-α pathway. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:611–617. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.118315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richez C, et al. IFN regulatory factor 5 is required for disease development in the FcγRIIB−/−Yaa and FcγRIIB–/– mouse models of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2010;184:796–806. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Remmers EF, et al. STAT4 and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor KE, et al. Specificity of the STAT4 genetic association for severe disease manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palomino-Morales RJ, et al. STAT4 but not TRAF1/C5 variants influence the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus in Colombians. Genes Immun. 2008;9:379–382. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawasaki A, et al. Role of STAT4 polymorphisms in systemic lupus erythematosus in a Japanese population: a case-control association study of the STAT1–STAT4 region. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:R113. doi: 10.1186/ar2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sigurdsson S, et al. A risk haplotype of STAT4 for systemic lupus erythematosus is overexpressed, correlates with anti-dsDNA and shows additive effects with two risk alleles of IRF5. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2868–2876. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kariuki SN, et al. Cutting edge: autoimmune disease risk variant of STAT4 confers increased sensitivity to IFN-α in lupus patients in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;182:34–38. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abelson AK, et al. STAT4 associates with systemic lupus erythematosus through two independent effects that correlate with gene expression and act additively with IRF5 to increase risk. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1746–1753. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.097642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Namjou B, et al. High-density genotyping of STAT4 reveals multiple haplotypic associations with systemic lupus erythematosus in different racial groups. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1085–1095. doi: 10.1002/art.24387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen S, Dadi H, Shaoul E, Sharfe N, Roifman CM. Cloning and characterization of a lymphoid-specific, inducible human protein tyrosine phosphatase, Lyp. Blood. 1999;93:2013–2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gregersen PK, Olsson LM. Recent advances in the genetics of autoimmune disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:363–391. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bottini N, et al. A functional variant of lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase is associated with type I diabetes. Nat Genet. 2004;36:337–338. doi: 10.1038/ng1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Orrú V, et al. A loss-of-function variant of PTPN22 is associated with reduced risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:569–579. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kariuki SN, Crow MK, Niewold TB. The PTPN22 C1858T polymorphism is associated with skewing of cytokine profiles toward high interferon-α activity and low tumor necrosis factor α levels in patients with lupus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2818–2823. doi: 10.1002/art.23728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bredius RG, et al. Phagocytosis of Staphylococcus aureus and Hemophilus influenzae type B opsonized with polyclonal human IgG1 and IgG2 antibodies. Functional hFcγ RIIa polymorphism to IgG2. J Immunol. 1993;151:1463–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Duits AJ, et al. Skewed distribution of IgG Fcγ receptor IIa (CD32) polymorphism is associated with renal disease in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1832–1836. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yap SN, Phipps ME, Manivasagar M, Tan SY, Bosco JJ. Human Fcγ receptor IIA (FcγRIIA) genotyping and association with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in Chinese and Malays in Malaysia. Lupus. 1999;8:305–310. doi: 10.1191/096120399678847876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen JY, et al. Fcγ receptor IIa, IIIa, and IIIb polymorphisms of systemic lupus erythematosus in Taiwan. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:877–880. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.005892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salmon JE, et al. Fcγ RIIA alleles are heritable risk factors for lupus nephritis in African Americans. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1348–1354. doi: 10.1172/JCI118552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Song YW, et al. Abnormal distribution of Fcγ receptor type IIa polymorphisms in Korean patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:421–426. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199803)41:3<421::AID-ART7>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koene HR, et al. The FcγRIIIA-158F allele is a risk factor for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1813–1818. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199810)41:10<1813::AID-ART13>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alarcón GS, et al. Time to renal disease and end-stage renal disease in PROFILE: a multiethnic lupus cohort. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zuniga R, et al. Identification of IgG subclasses and C-reactive protein in lupus nephritis: the relationship between the composition of immune deposits and FCγ receptor type IIA alleles. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:460–470. doi: 10.1002/art.10930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Magnusson V, et al. Both risk alleles for FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIA are susceptibility factors for SLE: a unifying hypothesis. Genes Immun. 2004;5:130–137. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sullivan KE, et al. Analysis of polymorphisms affecting immune complex handling in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:446–452. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kyogoku C, et al. Fcγ receptor gene polymorphisms in Japanese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: contribution of FCGR2B to genetic susceptibility. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1242–1254. doi: 10.1002/art.10257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Siriboonrit U, et al. Association of Fcγ receptor IIb and IIIb polymorphisms with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in Thais. Tissue Antigens. 2003;61:374–383. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chu ZT, et al. Association of Fcγ receptor IIb polymorphism with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in Chinese: a common susceptibility gene in the Asian populations. Tissue Antigens. 2004;63:21–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li X, et al. A novel polymorphism in the Fcγ receptor IIB (CD32B) transmembrane region alters receptor signaling. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3242–3252. doi: 10.1002/art.11313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kyogoku C, Tsuchiya N, Wu H, Tsao BP, Tokunaga K. Association of Fcγ receptor IIA, but not IIB and IIIA, polymorphisms with systemic lupus erythematosus: a family-based association study in Caucasians. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:671–673. doi: 10.1002/art.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Magnusson V, et al. Polymorphisms of the Fcγ receptor type IIB gene are not associated with systemic lupus erythematosus in the Swedish population. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1348–1350. doi: 10.1002/art.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Floto RA, et al. Loss of function of a lupus-associated FcγRIIb polymorphism through exclusion from lipid rafts. Nat Med. 2005;11:1056–1058. doi: 10.1038/nm1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Su K, et al. A promoter haplotype of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif-bearing FcγRIIb alters receptor expression and associates with autoimmunity. II Differential binding of GATA4 and Yin-Yang1 transcription factors and correlated receptor expression and function. J Immunol. 2004;172:7192–7199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.7192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Salmon JE, Edberg JC, Kimberly RP. Fcγ receptor III on human neutrophils. Allelic variants have functionally distinct capacities. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1287–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI114566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hatta Y, et al. Association of Fcγ receptor IIIB, but not of Fcγ receptor IIA and IIIA polymorphisms with systemic lupus erythematosus in Japanese. Genes Immun. 1999;1:53–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Clark MR, Liu L, Clarkson SB, Ory PA, Goldstein IM. An abnormality of the gene that encodes neutrophil Fcγ receptor III in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:341–346. doi: 10.1172/JCI114706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Koene HR, Kleijer M, Roos D, de Hasse M, Von dem Borne AE. FcγRIIIB gene duplication: evidence for presence and expression of three distinct FcγRIIIB genes in NA(1+,2+)SH(+) individuals. Blood. 1998;91:673–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Willcocks LC, et al. Copy number of FCGR3B, which is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, correlates with protein expression and immune complex uptake. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1573–1582. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Walport MJ, Davies KA, Botto M. C1q and systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunobiology. 1998;199:265–285. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(98)80032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Racila DM, et al. Homozygous single nucleotide polymorphism of the complement C1QA gene is associated with decreased levels of C1q in patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2003;12:124–132. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu329oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Namjou B, et al. Evaluation of C1q genomic region in minority racial groups of lupus. Genes Immun. 2009;10:517–524. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yamada M, et al. Complement C1q regulates LPS-induced cytokine production in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:221–230. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lood C, et al. C1q inhibits immune complex-induced interferon-alpha production in plasmacytoid dendritic cells: a novel link between C1q deficiency and systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3081–3090. doi: 10.1002/art.24852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kollewe C, et al. Sequential autophosphorylation steps in the interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-1 regulate its availability as an adaptor in interleukin-1 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5227–5236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jacob CO, et al. Identification of IRAK1 as a risk gene with critical role in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6256–6261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901181106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sawalha AH, et al. Common variants within MECP2 confer risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stetson DB, Ko JS, Heidmann T, Medzhitov R. Trex1 prevents cell-intrinsic initiation of autoimmunity. Cell. 2008;134:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee-Kirsch MA, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the 3′–5′ DNA exonuclease TREX1 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1065–1067. doi: 10.1038/ng2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ramantani G, et al. Expanding the phenotypic spectrum of lupus erythematosus in Aicardi–Goutières syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1469–1477. doi: 10.1002/art.27367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ito T, et al. OX40 ligand shuts down IL-10-producing regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13138–13143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603107103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stüber E, Neurath M, Calderhead D, Fell HP, Strober W. Cross-linking of OX40 ligand, a member of the TNF/NGF cytokine family, induces proliferation and differentiation in murine splenic B cells. Immunity. 1995;2:507–521. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cunninghame Graham DS, et al. Polymorphism at the TNF superfamily gene TNFSF4 confers susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:83–89. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Delgado-Vega AM, et al. Replication of the TNFSF4 (OX40L) promoter region association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes Immun. 2009;10:248–253. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hagiwara E, Gourley MF, Lee S, Klinman DK. Disease severity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus correlates with an increased ratio of interleukin-10: interferon-γ-secreting cells in the peripheral blood. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:379–385. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Eskdale J, et al. Interleukin 10 secretion in relation to human IL-10 locus haplotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9465–9470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Eskdale J, Wordsworth P, Bowman S, Field M, Gallagher G. Association between polymorphisms at the human IL-10 locus and systemic lupus erythematosus. Tissue Antigens. 1997;49:635–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1997.tb02812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mehrian R, et al. Synergistic effect between IL-10 and bcl-2 genotypes in determining susceptibility to SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:596–602. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199804)41:4<596::AID-ART6>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chong WP, et al. Association of interleukin-10 promoter polymorphisms with systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes Immun. 2004;5:484–492. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bengtsson AA, et al. Activation of type I interferon system in systemic lupus erythematosus correlates with disease activity but not with antiretroviral antibodies. Lupus. 2000;9:664–671. doi: 10.1191/096120300674499064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Okamoto T. NFκB and rheumatic diseases. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2006;6:359–372. doi: 10.2174/187153006779025685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Beyaert R, Heyninck K, Van Huffel S. A20 and A20-binding proteins as cellular inhibitors of nuclear factor-kappa B-dependent gene expression and apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1143–1151. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shimane K, et al. The association of a nonsynonymous single-nucleotide polymorphism in TNFAIP3 with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis in the Japanese population. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:574–579. doi: 10.1002/art.27190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Salloum R, et al. Genetic variation at the IRF7/PHRF1 locus is associated with autoantibody profile and serum interferon-alpha activity in lupus patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:553–561. doi: 10.1002/art.27182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Reth M, Wienands J. Initiation and processing of signals from the B cell antigen receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:453–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhang Z, et al. The association of the BLK gene with SLE was replicated in Chinese Han. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:619–624. doi: 10.1007/s00403-010-1029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ito I, et al. Replication of the association between the C8orf13-BLK region and systemic lupus erythematosus in a Japanese population. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:553–558. doi: 10.1002/art.24246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yokoyama K, et al. BANK regulates BCR-induced calcium mobilization by promoting tyrosine phosphorylation of IP(3) receptor. EMBO J. 2002;21:83–92. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Maier H, Colbert J, Fitzsimmons D, Clark DR, Hagman J. Activation of the early B-cell-specific mb-1 (Ig-α) gene by Pax-5 is dependent on an unmethylated Ets binding site. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1946–1960. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.6.1946-1960.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Moisan J, Grenningloh R, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Ho IC. Ets-1 is a negative regulator of TH17 differentiation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2825–2835. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang D, et al. Ets-1 deficiency leads to altered B cell differentiation, hyperresponsiveness to TLR9 and autoimmune disease. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1179–1191. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wojcik H, Griffiths E, Staggs S, Hagman J, Winandy S. Expression of a non-DNA-binding Ikaros isoform exclusively in B cells leads to autoimmunity but not leukemogenesis. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1022–1032. doi: 10.1002/eji.200637026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Luo BH, Carman CV, Springer TA. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Han S, et al. Evaluation of imputation-based association in and around the integrin-αM (ITGAM) gene and replication of robust association between a non-synonymous functional variant within ITGAM and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1171–1180. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yang W, et al. ITGAM is associated with disease susceptibility and renal nephritis of systemic lupus erythematosus in Hong Kong Chinese and Thai. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2063–2070. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Data