Characteristics and distribution of Listeria spp., including Listeria species newly described since 2009 (original) (raw)

Abstract

The genus Listeria is currently comprised of 17 species, including 9 Listeria species newly described since 2009. Genomic and phenotypic data clearly define a distinct group of six species (Listeria sensu strictu) that share common phenotypic characteristics (e.g., ability to grow at low temperature, flagellar motility); this group includes the pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. The other 11 species (Listeria sensu lato) represent three distinct monophyletic groups, which may warrant recognition as separate genera. These three proposed genera do not contain pathogens, are non-motile (except for Listeria grayi), are able to reduce nitrate (except for Listeria floridensis), and are negative for the Voges-Proskauer test (except for L. grayi). Unlike all other Listeria species, species in the proposed new genus Mesolisteria are not able to grow below 7 °C. While most new Listeria species have only been identified in a few countries, the availability of molecular tools for rapid characterization of putative Listeria isolates will likely lead to future identification of isolates representing these new species from different sources. Identification of Listeria sensu lato isolates has not only allowed for a better understanding of the evolution of Listeria and virulence characteristics in Listeria but also has practical implications as detection of Listeria species is often used by the food industry as a marker to detect conditions that allow for presence, growth, and persistence of L. monocytogenes. This review will provide a comprehensive critical summary of our current understanding of the characteristics and distribution of the new Listeria species with a focus on Listeria sensu lato.

Keywords: Listeria, Listeria sensu strictu, Listeria sensu lato, New species, New genus

Introduction

The genus Listeria currently includes 17 recognized species (Listeria monocytogenes, Listeria seeligeri, Listeria ivanovii, Listeria welshimeri, Listeria marthii, Listeria innocua, Listeria grayi, Listeria fleischmannii, Listeria floridensis, Listeria aquatica, Listeria newyorkensis, Listeria cornellensis, Listeria rocourtiae, Listeria weihenstephanensis, Listeria grandensis, Listeria riparia, and Listeria booriae) of small rod-shaped gram-positive bacteria. Only two of these species, L. monocytogenes and L. ivanovii, are considered pathogens. L. monocytogenes is an important human foodborne pathogen and the third leading cause of foodborne deaths due to microbial causes in the USA (Scallan et al. 2011). Human disease cases and outbreaks caused by this organism have a considerable economic impact for society and the food industry (Ivanek et al. 2004). In addition, the food industry as well as regulatory agencies around the world perform a large number of tests, of food and environmental samples, for L. monocytogenes and Listeria spp.; hence, sales of test kits for these organisms are an important revenue for a number of companies. Importantly, detection of Listeria species is often used by the food industry as a marker to detect conditions that allow for presence, growth, and persistence of L. monocytogenes. Hence, identification of new Listeria species and changes in the taxonomy of Listeria can have considerable impacts on food industry and test kit manufacturers.

Eleven Listeria species (L. marthii, L. rocourtiae, L. weihenstephanensis, L. grandensis, L. riparia, L. booriae, L. fleischmannii, L. floridensis, L. aquatica, L. newyorkensis, and L. cornellensis) have been described since 2009 (Bertsch et al. 2013; den Bakker et al. 2014; Graves et al. 2010; Lang Halter et al. 2013; Leclercq et al. 2010; Weller et al. 2015). Before this, the last description of a new Listeria species occurred in 1984 (L. ivanovii) (Seeliger et al. 1984). Importantly, all these newly recognized species have been validly described through publications in the International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, and their species classification is supported by recognized taxonomic criteria (ANib and/or DNA-DNA hybridization data). Similar to a previous report (Chiara et al. 2015), we will, in this review, categorize the species in the genus Listeria into two groups including (i) Listeria sensu strictu, which includes L. monocytogenes, L. seeligeri, L. marthii, L. ivanovii, L. welshimeri, and L. innocua (Chiara et al. 2015), and (ii) Listeria sensu lato group, which includes the other 11 Listeria species (L. grayi and 10 Listeria species newly described since 2009). The separation into these two groups is based on the relatedness of species to L. monocytogenes, which is both the first named Listeria species classified and the most important species in terms of public health and economic impact. This review will provide a summary of the current knowledge on the phenotypic and genetic characteristics of all members of the genus Listeria with a focus on Listeria sensu lato and the Listeria species that have been newly described since 2009. Insights into the recently recognized expanded diversity of the current genus Listeria will both improve our ability to understand the evolution of virulence and virulence-associated characteristics in this important gram-positive group and will help with an improved ability to develop and implement testing procedures for both L. monocytogenes and Listeria species.

Listeria sensu strictu

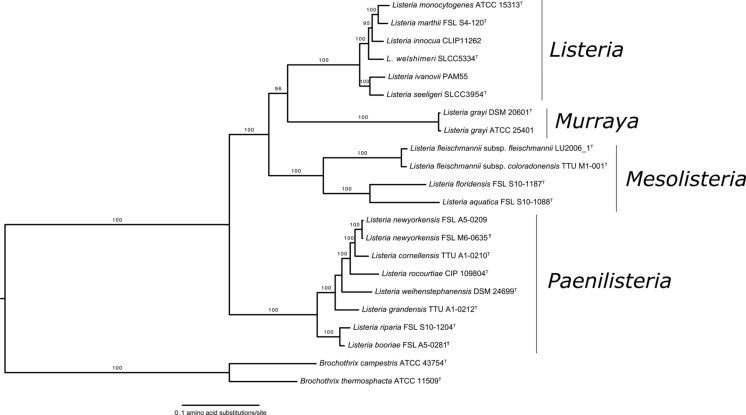

Listeria sensu strictu includes L. monocytogenes, L. seeligeri, L. ivanovii, L. welshimeri, and L. innocua, which all have been described before 1985 as well as L. marthii, which was first described in 2010. Listeria sensu strictu species form a tight monophyletic group within the genus Listeria (Fig. 1). Except for L. monocytogenes and L. innocua, all species in this group have been named after researchers that have played important roles in the study of Listeria.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree modified from Weller et al. (2015). Maximum likelihood phylogeny based on concatenated amino acid sequences of 325 single copy genes present in all Listeria species. Values on branches represent bootstrap values (>70 %) based on 250 bootstrap replicates. Proposed new genera names are shown close to monophyletic groups. Bar, 0.1 amino acid substitutions per site

Distribution

Most species within Listeria sensu strictu are well documented to be widely distributed and commonly found in different environments. L. monocytogenes has been isolated throughout the world, including in North America (Chapin et al. 2014; Sauders et al. 2012; Stea et al. 2015), South America (Hofer et al. 2000; Montero et al. 2015; Ruiz-Bolivar et al. 2011; Vallim et al. 2015), Europe (Gnat et al. 2015; Linke et al. 2014), Asia (Huang et al. 2015; Sugiri et al. 2014; Tango et al. 2014), Africa (Ahmed et al. 2013; Hmaied et al. 2014; Ndahi et al. 2014), and Oceania (McAuley et al. 2014). Human listeriosis cases have been reported throughout the world, including Africa, Oceania, South America, North America, Europe, and Asia (Ariza-Miguel et al. 2015; Barbosa et al. 2015; Hmaied et al. 2014; Huang et al. 2015; Lomonaco et al. 2015; Najjar et al. 2015; Negi et al. 2015; Ramdani-Bouguessa and Rahal 2000; Scallan et al. 2015a; Scallan et al. 2015b). Similarly, animal listeriosis cases caused by L. monocytogenes have also been reported throughout the world, including Africa (Akpavie and Ikheloa 1992; Meredith and Schneider 1984; Schroeder and van Rensburg 1993), South America (Headley et al. 2013; Headley et al. 2014), North America (Wiedmann et al. 1997; Wiedmann et al. 1994; Wiedmann et al. 1999; Woo-Sam 1999), Asia (Gu et al. 2015; Malik et al. 2002), Oceania (Fairley and Colson 2013; Fairley et al. 2012), and Europe (Rocha et al. 2013; Vela et al. 2001; Wagner et al. 2005). Animal listeriosis cases due to L. ivanovii has been recorded in different continents, including Oceania (McAuley et al. 2014; Sergeant et al. 1991), North America (Alexander et al. 1992), Europe (Gill et al. 1997; Kimpe et al. 2004), South America (Hofer et al. 2000), and Asia (Chand and Sadana 1999). We were not able to identify any reports of animal listeriosis caused by L. ivanovii in Africa. While L. ivanovii has rarely been linked to human listeriosis, L. ivanovii isolation from humans with listeriosis symptoms has been reported in different continents, including Europe (Cummins et al. 1994; Guillet et al. 2010; Lessing et al. 1994) and Asia (Snapir et al. 2006). We were unable to identify any reports of human listeriosis caused by L. ivanovii in Africa, Oceania, South America, and North America.

L. innocua, L. seeligeri, and L. welshimeri have also been identified throughout the world in most studies that identified reasonable large sets of Listeria isolates that were not L. monocytogenes to the species level (Chapin et al. 2014; Fox et al. 2015; Hofer et al. 2000; Linke et al. 2014; Sauders et al. 2012; Stea et al. 2015). A number of these studies have often failed to isolate L. ivanovii from environmental samples (Chapin et al. 2014; Fox et al. 2015; Sauders et al. 2012). For example, Sauders et al. (2012) reported that 23.4 and 22.3 % of samples obtained from natural and urban environments in New York State (USA), respectively, were positive for Listeria; the 442 Listeria isolates characterized in this study represented L. seeligeri (234 isolates), L. monocytogenes (80 isolates), L. welshimeri (74 isolates), L. innocua (50 isolates), and L. marthii (4 isolates). In a study in Austria (Linke et al. 2014), 149 out of 467 soil samples (30 %) were positive for Listeria spp.; species identified included L. monocytogenes (6 % of all samples), L. seeligeri (15 % of samples), L. innocua (6 % of samples), L. ivanovii (3 % of samples), L. welshimeri (2 % of samples), and unidentified Listeria spp. (2 % of samples). L. seeligeri thus has been the most commonly isolated Listeria species in two largest studies on Listeria diversity in natural environments. In a study in Canada (Stea et al. 2015), Listeria spp. were isolated from 53.8 % of the 329 water samples with a detection rate of 72.1 % in rural watersheds compared to 35.4 % for urban watersheds. L. monocytogenes was found in 30.3 and 34.5 % of the positive rural and urban watershed samples, respectively, and L. ivanovii was found in 8.4 and 6.9 % of these samples. Other Listeria spp. were not individually identified in this study but grouped into two large groups. The L. innocua group, including L. innocua, L. seeligeri, L. marthii, and L. grayi, was isolated from 56.3 and 34.5 % of the positive rural and urban watershed samples, respectively. The L. welshimeri group, which included L. welshimeri and all other Listeria spp., was isolated from 37 and 43.1 % of the positive rural and urban watershed samples, respectively (Stea et al. 2015). Despite the less frequent isolation of L. ivanovii, this species has been isolated from farm environments (McAuley et al. 2014). While these data indicate that L. ivanovii is one of the least commonly isolated Listeria sensu strictu species, this could also be due to reduced recovery of this species in the enrichment media and isolation protocols that have typically been optimized for recovery of L. monocytogenes.

Conversely, the one Listeria sensu strictu species that may not be globally distributed is L. marthii. Thus far, this species has only been isolated from very specific natural areas in a small part of New York State (USA), Connecticut Hill and Finger Lakes National Forest, which are natural areas in close proximity to each other (Chapin et al. 2014; Sauders et al. 2012). In these same studies, L. marthii was not found in other natural areas and urban areas (Chapin et al. 2014; Sauders et al. 2012). A PubMed search as of November 11, 2015 also was not able to locate other studies that have reported identification of L. marthii. This could at least be partially due to the fact that L. marthii cannot be easily distinguished from the closely related L. innocua and thus could have been misclassified in other studies.

In general, there is no clear indication that different Listeria sensu strictu species are preferably found in certain environments, even though individual studies have identified statistical associations between different environments and isolation of specific Listeria species. For example, a study in the state of New York (USA) reported that L. seeligeri and L. welshimeri were significantly associated with natural environments (P < 0.0001), while L. innocua and L. monocytogenes were significantly associated with urban environments (P < 0.0001) (Sauders et al. 2012). A study carried out in Austria (Linke et al. 2014) found a significant association between the presence of Listeria spp. in soil samples and abiotic conditions such as moisture, pH, and soil type. The authors specifically found that Listeria spp. were more frequently isolated from soil samples with low moisture content, neutral pH, and soil types consisting of a mixture of sand and humus. The same authors also observed a seasonal effect on the prevalence of Listeria spp. in soil with the lowest isolation rates observed in July (winter).

Phenotypic characteristics

Listeria sensu strictu species share many phenotypic characteristics; this makes isolates from this group easily recognizable as being members of the genus Listeria (Table 1). Key phenotypic characteristics shared by all Listeria sensu strictu species include (i) ability to grow at temperatures as low as 4 °C, (ii) motility (at least at 30 °C), (iii) positive catalase reaction, (iv) inability to reduce nitrate to nitrite, and (v) positive reaction in the Voges-Proskauer test, indicating ability to produce acetoin from the fermentation of glucose through the butanediol pathway. Moreover, all sensu strictu species are capable of fermenting D-arabitol, α-methyl D-glucoside, cellobiose, D-fructose, D-mannose, N-acetylglucosamine, maltose, and lactose, while none of the species can ferment inositol, L-arabinose, and D-mannitol (Bertsch et al. 2013; Bille et al. 1992; den Bakker et al. 2014; McLauchlin and Rees 2009; Weller et al. 2015).

Table 1.

Phenotypic characteristics of Listeria species (modified from Weller et al. 2015)

| Listeria species | Voges-Proskauer | Methyl red | Nitrate reduction | Motility | Growth at 4 °C | Hemolysis | PI-PLC | Arylamidase | α-Mannosidase | Fermentation of | D-Arabitol | D-Xylose | L-Rhamnose | α-Methyl-D-glucoside | D-Ribose | Glucose-1-phosphate | D-Tagatose | D-Mannitol | Sucrose | Turanose | Glycerol | D-Galactose | L-Arabinose | L-Sorbose | Inositol | Methyl-α-D-mannose | Maltose | Lactose | Melibiose | Inulin | D-Melezitose | D-Lyxose | D-Glucose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Listeria sensu stricto | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L. monocytogenes | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | V | V | − | V! | − | − | + | + | V! | V! | V | V | V! | |

| L. marthii | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | V! | − | − | + | + | V | − | − | − | V! | |

| L. innocua | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | V | + | − | − | − | − | + | V | + | − | − | V! | − | − | + | + | V | V! | V | V | V! | |

| L. welshimeri | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | V | + | + | + | V | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | ND | + | + | − | − | V | V | + | |

| L. ivanovii | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | V | − | + | + | − | + | + | V | − | − | + | − | + | V | − | V! | − | − | + | + | − | − | V | − | V! | |

| L. seeligeri | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | ND | + | + | − | − | V | − | + | |

| Listeria sensu lato, possible new genus Murraya | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L. grayi | + | + | V | + | + | − | − | + | V | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | V | + | − | V! | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | V | + | |

| Listeria sensu lato, possible new genus Mesolisteria | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L. fleischmannii | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | V | V | V | + | − | − | V | V | V | + | + | V | − | V | − | + | |

| L. floridensis | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | |

| L. aquatica | V | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | V | − | + | − | V | − | − | − | − | − | − | V | + | |

| Listeria sensu lato, possible new genus Paenilisteria | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L. newyorkensis | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | V | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | |

| L. cornellensis | − | V | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | V | − | V | − | − | − | + | (+) | − | − | − | − | + | |

| L. rocourtiae | − | V | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | |

| L. weihenstephanensis | − | V | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | V! | − | − | − | − | + | |

| L. grandensis | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | V | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | |

| L. riparia | − | V | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | V | − | − | V | − | − | V | + | + | − | V | − | + | + | V | − | − | − | + | |

| L. booriae | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | V | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + |

Only the two species considered pathogenic, L. monocytogenes and L. ivanovii, as well as a few L. innocua strains (Johnson et al. 2004; McLauchlin and Rees 2009) show phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) activity, while L. monocytogenes, L. ivanovii, and L. seeligeri as well as some L. innocua strains show hemolytic capabilities (Johnson et al. 2004; McLauchlin and Rees 2009). L. ivanovii can be differentiated from L. monocytogenes by its unique ability, among sensu strictu species, to ferment D-ribose (Bertsch et al. 2013; Bille et al. 1992; den Bakker et al. 2014; McLauchlin and Rees 2009; Weller et al. 2015). L. welshimeri can be identified by its ability to ferment D-tagatose, while L. seeligeri is the only sensu strictu species capable of fermenting D-xylose but not capable of fermenting D-ribose or D-tagatose (Bertsch et al. 2013; Bille et al. 1992; den Bakker et al. 2014; McLauchlin and Rees 2009; Weller et al. 2015). L. marthii is the only sensu strictu species incapable of fermenting sucrose, a characteristic that can be used to differentiate strains from this species from other sensu strictu species (den Bakker et al. 2014). While L. innocua is typically identified by its inability to cause hemolysis and ferment D-xylose combined by its ability to ferment glycerol (Bertsch et al. 2013; Bille et al. 1992; den Bakker et al. 2014; McLauchlin and Rees 2009; Weller et al. 2015), hemolytic L. innocua strains are difficult to differentiate from L. monocytogenes and L. seeligeri based on standard biochemical tests (Johnson et al. 2004).

Importantly, phenotypic characteristics do not always allow for unambiguous classification of Listeria isolates. Phenotypic data alone, sometimes in combination with genetic data, have led to description of a number of “atypical” Listeria isolates both before and after 1985. For example, hemolytic L. innocua strains (as discussed above) could be considered atypical Listeria. Similarly, a number of atypical (including non-hemolytic) L. monocytogenes have been described (Burall et al. 2014; Hof 1984; Moreno et al. 2014; Pine et al. 1987). While one could argue that these non-hemolytic L. monocytogenes strains that were described before the taxonomic description of L. marthii may indeed have been L. marthii, a number of these strains were confirmed to truly be atypical L. monocytogenes. For example, the initial ATCC strain (ATCC 15313) which was found to be non-hemolytic (Jones and Seeliger 1983) appears to clearly represent L. monocytogenes. More recently, another non-hemolytic strain was confirmed as belonging to the species L. monocytogenes after whole genome sequencing (Burall et al. 2014). Overall, one cannot exclude though that at least some of the atypical Listeria strains that have been described in the past may represent species that either were not described at the times or have not been identified at all. Future characterization of atypical Listeria isolates by whole genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis would help to resolve some of these identification challenges and may yield additional species that have not yet been described.

Genomic characteristics

Listeria sensu strictu genomes share many characteristics. The G+C content varies from 34.6 to 41.6 %; genome sizes vary from 2.8 to 3.2 Mb, and Listeria genomes are highly syntenic (i.e., the order of the genes are highly conserved across different species) (den Bakker et al. 2010b). The Listeria sensu strictu pan-genome has been estimated as approximately 6500 genes, 17 % of which are involved in nucleobase, nucleotide, nucleoside, and nucleic acid metabolism, 14 % of which are involved in cellular macromolecular metabolism, and 10 % of which are involved in protein metabolic process (den Bakker et al. 2010b). The high number of internalin genes is another characteristic of Listeria sensu strictu genomes. L. welshimeri seems to have the lowest number of internalin genes among sensu strictu species with nine of these genes found in the only strain analyzed (den Bakker et al. 2010b). On the other hand, five different L. monocytogenes genomes were shown to have between 18 and 28 internalin genes encoded in their genomes (den Bakker et al. 2010b). Three Listeria pathogenicity islands (LiPI) have been identified in the genomes of Listeria sensu strictu strains. These LiPIs are further discussed below. Moreover, a 53-kb island that includes genes involved in the metabolism of ethanolamine, cobalamin, and propanediol has been identified in all Listeria sensu strictu species (Chiara et al. 2015). This island includes 82 genes involved in the cobalamin (vitamin B12) biosynthetic process and utilization of both ethanolamine and propane-2-diol, two carbon sources whose utilization is necessary for L. monocytogenes and Salmonella to cause disease in vertebrate hosts (Conner et al. 1998; Joseph et al. 2006; Klumpp and Fuchs 2007; Mellin et al. 2014). Absence of this island in all Listeria sensu lato species in conjunction with its homology and conserved arrangement of the genes in comparison to sequences from other bacteria led to speculations that the entire island has been transferred to Listeria sensu strictu ancestor through horizontal gene transfer from a _Salmonella_-like bacterium (Buchrieser et al. 2003) or from gram-positive bacteria (Chiara et al. 2015).

Virulence

L. monocytogenes is a facultative intracellular pathogen that causes a rare, yet severe, human illness; typical symptoms include septicemia, abortions, and encephalitis (McLauchlin and Rees 2009). In addition, a few instances have been reported where L. monocytogenes infection of humans has led to gastrointestinal illnesses without systemic infections (Aureli et al. 2000; Dalton et al. 1997; Frye et al. 2002). Human listeriosis is virtually always caused by foodborne exposure to L. monocytogenes (Scallan et al. 2011). In addition to human disease, L. monocytogenes also has been reported to cause invasive disease in >40 animal species. L. ivanovii is also considered a pathogen but has been predominantly linked to animal disease with some studies suggesting that L. ivanovii predominantly infects sheep (Chand and Sadana 1999; Sergeant et al. 1991), but occasional isolation of L. ivanovii from bovines (Alexander et al. 1992; Gill et al. 1997) and humans with symptoms consistent with listeriosis suggests that this organism may also be able to cause disease in other animals, including rarely in humans (Cummins et al. 1994; Guillet et al. 2010; Lessing et al. 1994; Ramage et al. 1999; Snapir et al. 2006). In most human cases, L. ivanovii was isolated from the patient’s blood, with no clear evidence of the transmission route. However, at least in one case, the septicemic condition was preceded by a gastrointestinal illness suggesting that the strain was orally acquired (Guillet et al. 2010).

L. innocua was initially considered non-pathogenic (hence its name) and non-hemolytic. Recent work has however identified a number of hemolytic L. innocua isolates. Presumably, these isolates would have been (mis-)classified as L. monocytogenes before the use of molecular methods that allow for identification and phylogenetic characterization (e.g., MLST methods), which clusters hemolytic L. innocua strains with non-hemolytic L. innocua. Interestingly, some hemolytic L. innocua (e.g., FSL J1-023) have been shown to invade (human) Caco-2 cells at same levels as L. monocytogenes (den Bakker et al. 2010b), while another study has characterized the hemolytic L. innocua strain PRL/NW 15B95 as avirulent in a mouse model (Johnson et al. 2004). L. innocua has also been isolated at least once from a fatal human case (Perrin et al. 2003), further supporting that at least some L. innocua may be able to cause human disease. No information whether this strain was hemolytic or not was provided, though. L. innocua strains carrying a L. monocytogenes lineage I-specific pathogenicity island, LiPI-3, have also been found and shown to be hemolytic when the gene llsA, encoded within LiPI-3, was expressed from a constitutive highly expressed Listeria promoter (Clayton et al. 2014). One of these strains was isolated from a human patient with meningitis in the UK (Clayton et al. 2014). Whole genome sequencing has confirmed that hemolytic L. innocua strains contain a complete Listeria pathogenicity island 1 (also referred as the prfA cluster); specifically, the hemolytic isolate FSL J1-023 was found to contain a Listeria pathogenicity island 1 (LiPI-1) that shows a high level of homology with the L. monocytogenes pathogenicity island 1 (den Bakker et al. 2010a). This and genomically similar hemolytic L. innocua strains thus will test positive by PCR-based and other molecular methods that detect L. monocytogenes based on the presence of hly or other genes located in the pathogenicity island 1. Interestingly, this same hemolytic L. innocua isolate (FSL J1-023) did not contain the complete inlAB operon, which encodes two internalins (InlA and InlB) that are critical virulence factors, but only contained inlA. Other atypical L. innocua strains encoding LiPI-1 and inlA have been found in Brazil (Moreno et al. 2014) and in Korean-imported clams (Johnson et al. 2004), suggesting that these atypical L. innocua strains are widespread. The specific implications that the presence of inlA and the absence of inlB have on virulence in humans and other animals remain to be determined. While InlA is essential for invasion of human intestinal epithelial cells, InlB appears to contribute to invasion of human hepatic and placental cells (Lecuit 2007). While the data available to date suggest that at least some L. innocua may have the potential to cause invasive human disease, further data are thus needed to determine whether all or some hemolytic L. innocua are a human health hazard and what their virulence is relative to L. monocytogenes.

While isolates of the species L. seeligeri also typically are hemolytic, this species is generally considered non-pathogenic. Interestingly, non-hemolytic L. seeligeri strains have been reported (Volokhov et al. 2006), and one study suggested that non-hemolytic L. seeligeri represent a recent loss of the Listeria pathogenicity island 1 (prfA cluster) (den Bakker et al. 2010a). Some possible cases of human disease caused by L. seeligeri have been described, including a human meningitis case (Rocourt et al. 1986). Genomic studies suggest that hemolytic L. seeligeri contain a variant of the Listeria pathogenicity island 1 (prfA cluster), which is characterized by the presence of additional genes not found in L. monocytogenes and a partial duplication of the gene plcB (Schmid et al. 2005), which seems to have been split into two independent ORFs in some strains (den Bakker et al. 2010b). To date, the inlAB operon has not been found among L. seeligeri strains. A functional study (Stelling et al. 2010) on selected L. seeligeri virulence genes indicates that (i) regulation of prfA expression differs between L. monocytogenes and L. seeligeri, although hly transcription is temperature dependent in both species, and (ii) PrfA and Hly functions are largely, but not fully, conserved between L. seeligeri and L. monocytogenes. While virulence gene homologs and their expression thus appear to have adapted to distinct but possibly related functions in L. monocytogenes and L. seeligeri (Stelling et al. 2010), it remains to be determined whether L. seeligeri is pathogenic in specific, yet to be determined, host species. Despite rare isolation from humans with illness symptoms, there is no evidence that L. seeligeri should be considered a pathogen or presents a human health risk comparable to L. monocytogenes.

On the other hand, all L. marthii and L. welshimeri isolates characterized to date have been non-hemolytic. None of the (few) L. marthii and L. welshimeri genomes sequenced so far contain the Listeria pathogenicity island 1 (prfA cluster), further supporting that members of these two species are non-pathogenic.

Listeria sensu lato

Listeria sensu lato is comprised of L. grayi (first described in 1966) as well as L. fleischmannii, L. floridensis, L. aquatica, L. newyorkensis, L. cornellensis, L. rocourtiae, L. weihenstephanensis, L. grandensis, L. riparia, and L. booriae. Phylogenetically, L. grayi is most closely related to Listeria sensu strictu species. L. fleischmannii, L. floridensis, and L. aquatica share a most recent common ancestor with L. grayi and sensu strictu species, while the other Listeria sensu lato species group together in the most basal cluster within the genus (Fig. 1; Weller et al. 2015). A list of Listeria sensu lato species with their respective type strains and repository places is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Type strains of Listeria spp. identified since 2010

| Species | Type strain (strain collection where available) | Other available strains (strain collection) |

|---|---|---|

| L. marthii | FSL S4-120T (=ATCC BAA-1595T = BEIR NR 9579T = CCUG 56148T = DSM-23813T) | Three other strains (BEI) |

| L. rocourtiae | CIP 109804T (=DSM 22097T) | |

| L. weihenstephanensis | WS 4560T (=DSM 24698T = LMG 26374T) | WS 4615 (=DSM 24699 = LMG 26375) |

| L. fleischmannii subsp. fleischmannii | LU2006-1T (=DSM 24998T = LMG 26584T = CIP 110547T) | LU2006-2; LU2006-3; DSM-25003; LMG 26585 |

| L. fleischmannii subsp. coloradonensis | TTU M1-001T (=ATCC BAA-2414T = DSM 25391T = CIP 110717T) | |

| L. floridensis | FSL S10-1187T (=DSM 26687T = LMG 28121T = BEI NR-42632T) | |

| L. aquatica | FSL S10-1188T (=DSM 26686T = LMG 28120T = BEI NR-42633T) | FSL S10-1181 |

| L. cornellensis | TTU A1-0210T (=FSL F6-0969T = DSM 26689T = LMG 28123T = BEI NR-42630T) | FSL F6-0970 |

| L. riparia | FSL S10-1204T (=DSM 26685T = LMG 28119T = BEI NR-42634T) | FSL S10-1219 |

| L. grandensis | TTU A1-0212T (=FSL F6-0971T = DSM 26688T = LMG 28122T = BEI NR-42631T) | |

| L. newyorkensis | FSL M6-0635T (=DSM 28861T = LMG 28310T) | FSL A5-0209 |

| L. booriae | FSL A5-0281T (=DSM 28860T = LMG 28311T) | FSL A5-0279 |

Distribution

With the exception of L. grayi, Listeria sensu lato species have only recently been described and their distribution is yet to be comprehensively elucidated. However, two species, L. newyorkensis and L. fleischmannii, have already been identified in both North America and Europe (Chiara et al. 2015; den Bakker et al. 2013; Weller et al. 2015), suggesting that their occurrence may be broad, at least in the northern hemisphere. L. newyorkensis has been isolated from raw milk in Italy (Chiara et al. 2015) and from a seafood processing plant in northeastern USA. L. fleischmannii has been isolated from cheeses in Italy and Switzerland and from the environment of a cattle ranch in the state of Colorado, USA. (Bertsch et al. 2013; den Bakker et al. 2013). Listeria sensu lato species only isolated in Europe so far include L. rocourtiae, which was isolated in Austria, from processed lettuce (Leclercq et al. 2010), and L. weihenstephanensis, isolated from vegetation in a pond in Germany (Lang Halter et al. 2013). Species only isolated in the USA include L. floridensis, L. aquatic, and L. riparia, all three isolated from running waters in the state of Florida, and L. cornellensis and L. grandensis, both isolated from water in the state of Colorado (Table 3; den Bakker et al. 2014). L. grayi has been isolated from several continents, including Europe, Asia, Africa, South America, and North America, and sources such as freshwater fish and abattoirs (Bernagozzi et al. 1994; Bouayad et al. 2015; Hofer et al. 2000; Jallewar et al. 2007; Schlech et al. 2005), suggesting that this species is distributed globally.

Table 3.

Reported isolation locations of Listeria sensu lato species (as of November 2015)

| Species | Source of isolation | References |

|---|---|---|

| L. rocourtiae | Pre-cut lettuce, Salzburg (Austria) | Leclercq et al. (2010) |

| L. weihenstephanensis | Vegetation (Lemma trisulca) from pond in Wolnzach/Pfaffenhofen (Germany) | Lang Halter et al. (2013) |

| L. fleischmannii | Cheese and ripening cellars (Switzerland); cheese (southern Italy); environmental samples, cattle ranch, Colorado (USA) | den Bakker et al. (2013), Bertsch et al. (2013) |

| L. floridensis | Running water, Florida (USA) | den Bakker et al. (2014) |

| L. aquatica | Running water, Florida (USA) | den Bakker et al. (2014) |

| L. cornellensis | Water, Colorado (USA) | den Bakker et al. (2014) |

| L. riparia | Running water, Florida (USA) | den Bakker et al. (2014) |

| L. grandensis | Water, Colorado (USA) | den Bakker et al. (2014) |

| L. newyorkensis | Non-food-contact surface in a seafood processing plant (northeastern USA); raw milk (southern Italy) | Weller et al. (2015) |

| L. booriae | Non-food-contact surface in a dairy processing plant (northeastern USA) | Weller et al. (2015) |

| L. grayi | Various locations (worldwide) | Bernagozzi et al. (1994), Bouayad et al. (2015), Hofer et al. (2000), Jallewar et al. (2007), Schlech et al. (2005) |

Phenotypes

Like the Listeria sensu strictu species, all sensu lato species are catalase positive, non-spore-forming, non-capsulated, and rod-shaped. Listeria sensu lato species present several phenotypic characteristics that distinguish them from Listeria sensu strictu species (see Table 1 for details). While all sensu strictu species are Voges-Proskauer reaction positive and hence able to produce acetoin from fermentation of glucose through the butanediol pathway, among sensu lato species, only L. grayi and one out of two L. aquatica strains analyzed have this ability (den Bakker et al. 2014). Conversely, while none of the sensu strictu species are able to reduce nitrate to nitrite, all sensu lato species but L. floridensis can reduce nitrate (den Bakker et al. 2014; Weller et al. 2015). Motility is another characteristic that appears restricted to the Listeria sensu strictu species and L. grayi, although contradictory results were initially obtained for L. rocourtiae and L. weihenstephanensis. In initial studies, Leclercq et al. (2010) and Lang Halter et al. (2013) reported that isolates representing these species were motile, while subsequent studies (Bertsch et al. 2013; den Bakker et al. 2014) reported no motility for representatives of these species. Subsequent motility tests carried out by Weller et al. (2015) also found no motility with all sensu lato strains tested (with the exception of L. grayi strains) at temperatures ranging from 4 to 37 °C. These findings are consistent with genomic studies that reported absence of flagellar genes from all Listeria sensu lato strains (except L. grayi), thus suggesting that L. grayi is the only motile Listeria sensu lato species (Chiara et al. 2015; den Bakker et al. 2013; den Bakker et al. 2014).

In terms of acid production from different carbohydrate substrates, a high variability has been observed within and between sensu lato species. All sensu lato species were able to acidify D-xylose and D-glucose, but none were able to acidify glucose 1-phosphate nor inulin. Other molecules presented variable results depending on the species (Weller et al. 2015). Interestingly, the species L. fleischmannii, L. aquatica, and L. floridensis all seem to have lost the ability to grow in liquid media at 4 °C, a key characteristic shared among other members of the genus Listeria. These three species form a cluster within the genus Listeria and share the most common recent ancestor with Listeria sensu strictu species and L. grayi, which suggests that the inability to grow at low temperatures was lost in this group.

While molecular methods provide for most reliable species classification, some specific phenotypic characteristics can be used to differentiate each species within Listeria sensu lato. L. grayi can be distinguished from other sensu lato species by a positive result in the Voges-Proskauer test and by a positive result in a motility test (McLauchlin and Rees 2009; Weller et al. 2015). Moreover, L. grayi can be differentiated from Listeria sensu strictu species by its ability to ferment D-mannitol (McLauchlin and Rees 2009; Weller et al. 2015). L. fleischmannii is unable to grow well at low temperatures and can be differentiated from other sensu lato species by its ability to ferment D-arabitol, L-rhamnose, and D-ribose (Bertsch et al. 2013; den Bakker et al. 2013; Weller et al. 2015). In addition to being characterized by its inability to grow at temperatures below 7 °C, L. floridensis is the only sensu lato species unable to reduce nitrate (den Bakker et al. 2014; Weller et al. 2015). L. aquatica is the only Listeria species unable to ferment maltose and α-methyl D-glucoside and the only sensu lato species able to ferment D-tagatose (den Bakker et al. 2014; Weller et al. 2015). L. newyorkensis can be differentiated from other Listeria species by its inability to acidify D-arabitol, absence of α-mannosidase activity, and ability to acidify D-ribose, D-galactose, and L-arabinose (Weller et al. 2015). L. cornellensis can be distinguished from other sensu lato species by being unable to ferment L-rhamnose at 37 °C and presents a weak acidification of lactose (den Bakker et al. 2014; Weller et al. 2015). L. rocourtiae can be distinguished from other sensu lato species by its positive α-mannosidase activity combined with its inability to ferment L-arabinose and D-arabitol (Leclercq et al. 2010; Weller et al. 2015). L. weihenstephanensis can be differentiated from other sensu lato species by its ability to ferment D-arabitol, L-rhamnose, and D-mannitol (Lang Halter et al. 2013; Weller et al. 2015). L. grandensis may be differentiated from L. cornellensis by its stronger ability to ferment lactose (den Bakker et al. 2014; Weller et al. 2015). L. riparia can be distinguished from other sensu lato species by its positive α-mannosidase activity in combination with the ability to ferment L-rhamnose, D-galactose, and L-arabinose (den Bakker et al. 2014; Weller et al. 2015). L. booriae can be differentiated from other Listeria by its ability to ferment melibiose, L-arabinose, and D-arabitol (Weller et al. 2015). While a number of phenotypic characteristics can thus be used to differentiate Listeria sensu lato species, identification of Listeria sensu lato isolates using standard biochemical test kits may often not be straight forward as carbohydrate substrates that allow for species differentiation may not be included and as identification schemes and databases may not yet have been updated with information on the recently described Listeria species.

In terms of pathogenicity, none of the sensu lato species seem to be pathogenic as they all failed to produce positive results in both hemolytic tests and phosphoinositide phospholipase C activity tests (Bertsch et al. 2013; den Bakker et al. 2013; den Bakker et al. 2014; Lang Halter et al. 2013; Leclercq et al. 2010; Weller et al. 2015). Moreover, invasion assays using human carcinogenic cell lines (Caco-2) showed that L. fleischmannii is not able to internalize into human intestinal epithelial cells further supporting that this specific species is not pathogenic for humans (Bertsch et al. 2013).

Genomic characteristics

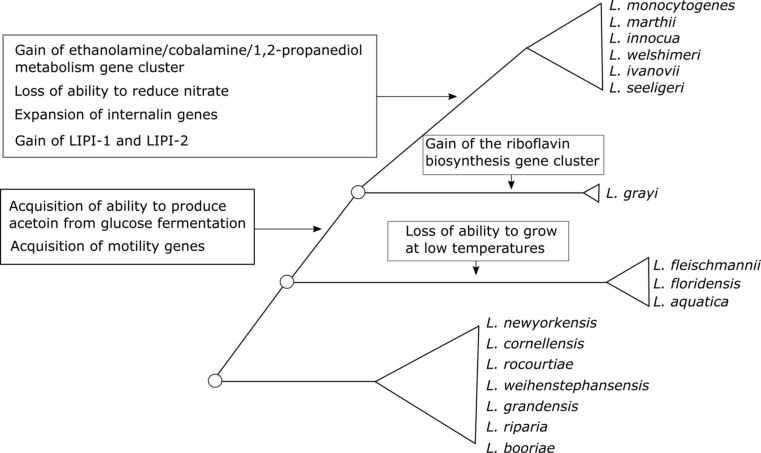

The availability of genome sequence data for all Listeria sensu lato species not only presented unique opportunities to better characterize these species but also allowed for novel insights in the evolution of virulence related and other relevant phenotypes in the overall genus Listeria (Fig. 2). The G+C content of sensu lato genomes varies from 38.3 % (L. fleischmannii) to 45.2 (L. newyorkensis and L. booriae). As expected based on phenotypic data, genome analyses showed that none of the Listeria sensu lato species harbor the Listeria pathogenicity island 1, which includes the major virulence genes prfA, plcA, hly, mpl, actA, plcB, or the Listeria pathogenicity island 2, which includes inlA and inlB. With the exception of L. grayi, none of the other sensu lato species carry the motility genes that encode flagellar proteins, which explains why these species are not motile. Phylogenetic analyses suggest that the ancestor of Listeria sensu strictu and L. grayi acquired the whole flagellar biosynthetic genes through horizontal gene transfer from an ancestor of the Bacillus cereus complex (Chiara et al. 2015) (see Fig. 2). The only gene related to motility that is present in a sensu lato species (other than L. grayi) is mogR, which was identified only in L. fleischmannii. This gene encodes for the motility gene repressor MogR (den Bakker et al. 2013); its specific function in this species remains to be determined. Another interesting genomic feature was observed among the genome sequences for two L. grayi strains. Four genes, genomically clustered, were found among these strains and encode for proteins involved in the biosynthesis of riboflavin (Chiara et al. 2015). The origin of these genes is not clear. However, the absence of these genes from all other Listeria species suggests that the cluster was acquired via horizontal gene transfer by the ancestor of L. grayi from another bacterial species.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the phylogenetic history of the current genus Listeria. Circles represent extinct ancestor species. Triangles represent the current monophyletic taxa proposed here to be classified into distinct genera. Text close to branches depicts evolutionary events of gain or loss of genetic features that help define current taxa

Interestingly, Listeria sensu lato species genomes showed an underrepresentation of genes associated with internalin domains when compared to sensu strictu species (Chiara et al. 2015; den Bakker et al. 2010b). This suggests that expansion of internalin genes happened after the divergence between Listeria sensu strictu and Listeria sensu lato and further supports that Listeria sensu lato strains are unlikely to be pathogenic for mammalian species as internalins have been shown to typically be important for interactions between Listeria and mammalian hosts (Pizarro-Cerda et al. 2012). Interestingly, L. fleischmannii subsp. coloradonensis genome has also been found to harbor a gene encoding a putative mosquitocidal toxin MTX2 from Bacillus, which also resembles the Clostridium perfringens potent epsilon toxin ETX that causes rapid fatal enterotoxemia in animals (den Bakker et al. 2013); this raises the possibility that at least some sensu lato isolates may be able to cause disease in non-mammalian hosts such as insects.

Phylogeny and phenotypic characteristics of Listeria sensu lato suggesting that these species may represent new genera

In taxonomy, delineation of different species is governed by fairly well-defined criteria. While, traditionally, DNA-DNA hybridization values of <70 % were used to delineate different species (Wayne et al. 1987), more recently whole genome sequencing-based criteria (ANIb) have been used to define different species (Richter and Rossello-Mora 2009). In Listeria, this approach was used by den Bakker et al. (2014) and Weller et al. (2015) to classify newly identified Listeria strains into seven distinct species and to confirm classification into separate species for other species that had been proposed previously (Bertsch et al. 2013; Lang Halter et al. 2013; Leclercq et al. 2010).

While clear cutoffs exist for classification of isolates into a new species, cutoffs for defining new genera are much less well defined (Qin et al. 2014). It has been suggested that a 16S rRNA diversity higher than 5 % or an amino acid identity (AAI) lower than 70 % could be used to determine whether two species should belong to distinct genera (Konstantinidis and Tiedje 2007). Qin et al. (2014) have suggested that a percentage of conserved proteins (POCP) > 50 % should be used as a threshold to define whether two species should be classified into the same genus or not. Deloger et al. (2009) suggested the utilization of the DNA maximal unique matches (MUMs) shared by two genomes as a tool for classification of species and genus. However, there is no clear agreement on definitive thresholds that could be used to determine boundaries of bacterial genera. A clear convergence of phylogenetic and phenotypic data as well as whole genome sequencing-based similarity measures suggested though that the current genus Listeria may warrant reclassification into more than one genus. Listeria sensu strictu clearly represents a distinct and well-defined group of organisms that should be maintained as a single genus with the name Listeria. The species currently grouped in Listeria sensu lato on the other hand appear to warrant reclassification into three different genera (see Fig. 1); reclassification into more than one genus is not only required to avoid phylogenetically incongruent genera but also yields proposed genera with distinct and unique phenotypic characteristics (e.g., all species in the proposed genus Mesolisteria are not able to grow at 4 °C). Specifically, we propose that L. grayi could be classified into a distinct new genus named Murraya; this represents a revival of the previously proposed genus Murraya (Wemekamp-Kamphuis et al. 2002). ANIb values based on comparisons of genome sequences of Murraya strains and Listeria sensu stricto strains support that these taxa are highly divergent (ANIb <73 %). L. fleischmannii, L. aquatica, and L. floridensis could be classified into another genus named Mesolisteria (referring to the mesophillic nature of species within this genus). Finally, the species L. newyorkensis, L. cornellensis, L. rocourtiae, L. weihenstephanensis, L. grandensis, L. riparia, and L. booriae could be classified into the new genus named Paenilisteria (almost Listeria, referring to the phenotypic resemblance to the genus Listeria). Importantly, Listeria sensu lato species present some phenotypic features different from those that characterize the genus Listeria. For example, with the exception of L. grayi, all sensu lato species are non-motile, while all sensu strictu species are motile. All sensu lato species with the exception of L. floridensis are capable of reducing nitrate to nitrite, an ability not present among sensu strictu species. Moreover, three sensu lato species (L. fleischmannii, L. floridensis, and L. aquatica) are unable to grow at low temperatures, one of the major characteristics of the genus Listeria. Genomically, sensu lato species also lack features characteristic of the genus Listeria such as a high number of genes encoding for internalin-like proteins. Based on the data available to date, we thus would like to propose that the Listeria sensu lato species may warrant classification into separate genera according to their phylogenetic and phenotypic characteristics (Fig. 2), even though further genome sequence analyses (e.g., determination of AAI, POCP, and MUM values) may be helpful and needed for a final reclassification proposal.

Conclusions

The genus Listeria has considerably expanded in the past decade to include 17 species with diverse phenotypic and genotypic characteristics. Comparative characterization of the nine species newly described since 2009, including through comparative genomic analyses, has provided new insights into the evolution of Listeria and suggests a need to reevaluate the taxonomy of the current genus Listeria. Specifically, there is convincing evidence that a group of Listeria species (“Listeria sensu lato”) that are distinct from L. monocytogenes may warrant reclassification into three different genera (including revival of the previously proposed genus Murraya); these species include all but one of the Listeria species newly reported since 2009. Taxonomy revaluation of Listeria sensu lato and clarification of the genetic and phenotypic characteristics of this group are of particular importance, since this group includes species that show distinct phenotypes from Listeria sensu strictu, which includes the pathogen L. monocytogenes. For example, all Listeria sensu lato species, expect for L. grayi, lack flagellar motility, and a distinct subset of Listeria sensu lato species (proposed to represent the new genus Mesolisteria) lacks the ability to grow at temperatures below 7 °C. Identification of a number of new Listeria species that are distinct from Listeria sensu strictu (which includes L. monocytogenes) and that have preliminarily been designated as Listeria sensu lato also is important for diagnostic kit manufacturers and the food industry, which uses tests for the genus Listeria as an indicator that detects conditions that allow for presence, growth, and persistence of L. monocytogenes. In particular, clarity is needed whether a meaningful test for conditions that allow for presence, growth, and persistence of L. monocytogenes should (i) detect only Listeria sensu strictu or (ii) should detect all 17 currently described Listeria species. Reclassification of Listeria sensu lato into different genera would provide clarity on this issue and would clarify the genus Listeria as a genetically and phenotypically circumscribed group that only contains six species that share key phenotypes such as ability to grow at low temperatures and a positive Voges-Proskauer reaction. Until a reclassification and clarification of the genus Listeria is completed, it is essential for end users of Listeria tests to understand which Listeria species a given test detects and to correspondingly interpret test results (e.g., whether detection of Listeria spp. that do not grow at refrigeration temperatures truly predicts conditions that allow for presence, growth, and persistence of L. monocytogenes).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Henk den Bakker for his help with the manuscript preparation. This material is partially based upon work that is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, US Department of Agriculture Hatch funds under NYC-143445 as well as an unrestricted gift from Wegmans Foods. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the US Department of Agriculture.

Compliance with ethical standards

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Funding

This material is partially based upon work that is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, US Department of Agriculture Hatch funds under NYC-143445 as well as an unrestricted gift from Wegmans Foods. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the US Department of Agriculture.

Conflict of interest

Renato H. Orsi declares that he has no conflict of interest. Martin Wiedmann declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmed HA, Hussein MA, El-Ashram AM. Seafood a potential source of some zoonotic bacteria in Zagazig, Egypt, with the molecular detection of Listeria monocytogenes virulence genes. Vet Ital. 2013;49:299–308. doi: 10.12834/VetIt.1305.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akpavie SO, Ikheloa JO. An outbreak of listeriosis in cattle in Nigeria. Rev Elev Med Vet Pays Trop. 1992;45:263–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander AV, Walker RL, Johnson BJ, Charlton BR, Woods LW. Bovine abortions attributable to Listeria ivanovii: four cases (1988-1990) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1992;200:711–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariza-Miguel J, Fernandez-Natal MI, Soriano F, Hernandez M, Stessl B, Rodriguez-Lazaro D. Molecular epidemiology of invasive listeriosis due to Listeria monocytogenes in a Spanish hospital over a nine-year study period, 2006–2014. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:191409. doi: 10.1155/2015/191409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aureli P, Fiorucci GC, Caroli D, Marchiaro G, Novara O, Leone L, Salmaso S. An outbreak of febrile gastroenteritis associated with corn contaminated by Listeria monocytogenes. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1236–1241. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004273421702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa AV, Cerqueira Ade M, Rusak LA, Dos Reis CM, Leal NC, Hofer E, Vallim DC. Characterization of epidemic clones of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b isolated from humans and meat products in Brazil. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015;9:962–969. doi: 10.3855/jidc.5639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernagozzi M, Bianucci F, Sacchetti R, Bisbini P. Study of the prevalence of Listeria spp. in surface water. Zentralbl Hyg Umweltmed. 1994;196:237–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsch D, Rau J, Eugster MR, Haug MC, Lawson PA, Lacroix C, Meile L. Listeria fleischmannii sp. nov., isolated from cheese. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:526–532. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.036947-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bille J, Catimel B, Bannerman E, Jacquet C, Yersin MN, Caniaux I, Monget D, Rocourt J. API Listeria, a new and promising one-day system to identify Listeria isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1857–1860. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.6.1857-1860.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouayad L, Hamdi TM, Naim M, Leclercq A, Lecuit M. Prevalence of Listeria spp. and molecular characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from broilers at the abattoir. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2015;12:606–611. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchrieser C, Rusniok C, Kunst F, Cossart P, Glaser P. Comparison of the genome sequences of Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua: clues for evolution and pathogenicity. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;35:207–213. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(02)00448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burall LS, Grim C, Gopinath G, Laksanalamai P, Datta AR. Whole-genome sequencing identifies an atypical Listeria monocytogenes strain isolated from pet foods. Genome Announc. 2014;2:e01243–14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01243-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand P, Sadana JR. Outbreak of Listeria ivanovii abortion in sheep in India. Vet Rec. 1999;145:83–84. doi: 10.1136/vr.145.3.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin TK, Nightingale KK, Worobo RW, Wiedmann M, Strawn LK. Geographical and meteorological factors associated with isolation of Listeria species in New York state produce production and natural environments. J Food Prot. 2014;77:1919–1928. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara M, Caruso M, D’Erchia AM, Manzari C, Fraccalvieri R, Goffredo E, Latorre L, Miccolupo A, Padalino I, Santagada G, Chiocco D, Pesole G, Horner DS, Parisi A. Comparative genomics of Listeria sensu lato: genus-wide differences in evolutionary dynamics and the progressive gain of complex, potentially pathogenicity-related traits through lateral gene transfer. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7:2154–2172. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EM, Daly KM, Guinane CM, Hill C, Cotter PD, Ross PR. Atypical Listeria innocua strains possess an intact LIPI-3. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner CP, Heithoff DM, Julio SM, Sinsheimer RL, Mahan MJ. Differential patterns of acquired virulence genes distinguish Salmonella strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4641–4645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins AJ, Fielding AK, McLauchlin J. Listeria ivanovii infection in a patient with AIDS. J Infect. 1994;28:89–91. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(94)94347-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton CB, Austin CC, Sobel J, Hayes PS, Bibb WF, Graves LM, Swaminathan B, Proctor ME, Griffin PM. An outbreak of gastroenteritis and fever due to Listeria monocytogenes in milk. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:100–105. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701093360204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deloger M, El Karoui M, Petit MA. A genomic distance based on MUM indicates discontinuity between most bacterial species and genera. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:91–99. doi: 10.1128/JB.01202-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Bakker HC, Bundrant BN, Fortes ED, Orsi RH, Wiedmann M. A population genetics-based and phylogenetic approach to understanding the evolution of virulence in the genus Listeria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:6085–6100. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00447-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Bakker HC, Cummings CA, Ferreira V, Vatta P, Orsi RH, Degoricija L, Barker M, Petrauskene O, Furtado MR, Wiedmann M. Comparative genomics of the bacterial genus Listeria: genome evolution is characterized by limited gene acquisition and limited gene loss. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:688. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Bakker HC, Manuel CS, Fortes ED, Wiedmann M, Nightingale KK. Genome sequencing identifies Listeria fleischmannii subsp. coloradonensis subsp. nov., isolated from a ranch. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:3257–3268. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.048587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Bakker HC, Warchocki S, Wright EM, Allred AF, Ahlstrom C, Manuel CS, Stasiewicz MJ, Burrell A, Roof S, Strawn LK, Fortes E, Nightingale KK, Kephart D, Wiedmann M. Listeria floridensis sp. nov., Listeria aquatica sp. nov., Listeria cornellensis sp. nov., Listeria riparia sp. nov. and Listeria grandensis sp. nov., from agricultural and natural environments. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:1882–1889. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.052720-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairley RA, Colson M. Enteric listeriosis in a 10-month-old calf. N Z Vet J. 2013;61:376–378. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2013.809634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairley RA, Pesavento PA, Clark RG. Listeria monocytogenes infection of the alimentary tract (enteric listeriosis) of sheep in New Zealand. J Comp Pathol. 2012;146:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox EM, Wall PG, Fanning S. Control of Listeria species food safety at a poultry food production facility. Food Microbiol. 2015;51:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye DM, Zweig R, Sturgeon J, Tormey M, LeCavalier M, Lee I, Lawani L, Mascola L. An outbreak of febrile gastroenteritis associated with delicatessen meat contaminated with Listeria monocytogenes. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:943–949. doi: 10.1086/342582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill PA, Boulton JG, Fraser GC, Stevenson AE, Reddacliff LA. Bovine abortion caused by Listeria ivanovii. Aust Vet J. 1997;75:214. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1997.tb10069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnat S, Troscianczyk A, Nowakiewicz A, Majer-Dziedzic B, Ziolkowska G, Dziedzic R, Zieba P, Teodorowski O. Experimental studies of microbial populations and incidence of zoonotic pathogens in the faeces of red deer (Cervus elaphus) Lett Appl Microbiol. 2015;61:446–452. doi: 10.1111/lam.12471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves LM, Helsel LO, Steigerwalt AG, Morey RE, Daneshvar MI, Roof SE, Orsi RH, Fortes ED, Milillo SR, den Bakker HC, Wiedmann M, Swaminathan B, Sauders BD. Listeria marthii sp. nov., isolated from the natural environment, Finger Lakes National Forest. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:1280–1288. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.014118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Liang X, Huang Z, Yang Y. Outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes in pheasants. Poult Sci. 2015 doi: 10.3382/ps/pev264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillet C, Join-Lambert O, Le Monnier A, Leclercq A, Mechai F, Mamzer-Bruneel MF, Bielecka MK, Scortti M, Disson O, Berche P, Vazquez-Boland J, Lortholary O, Lecuit M. Human listeriosis caused by Listeria ivanovii. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:136–138. doi: 10.3201/eid1601.091155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headley SA, Bodnar L, Fritzen JT, Bronkhorst DE, Alfieri AF, Okano W, Alfieri AA. Histopathological and molecular characterization of encephalitic listeriosis in small ruminants from northern Parana. Brazil Braz J Microbiol. 2013;44:889–896. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822013000300036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headley SA, Fritzen JT, Queiroz GR, Oliveira RA, Alfieri AF, Di Santis GW, Lisboa JA, Alfieri AA. Molecular characterization of encephalitic bovine listeriosis from southern Brazil. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2014;46:19–25. doi: 10.1007/s11250-013-0441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hmaied F, Helel S, Le Berre V, Francois JM, Leclercq A, Lecuit M, Smaoui H, Kechrid A, Boudabous A, Barkallah I. Prevalence, identification by a DNA microarray-based assay of human and food isolates Listeria spp. from Tunisia. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2014;62:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof H. ) Virulence of different strains of Listeria monocytogenes serovar 1/2a. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1984;173:207–218. doi: 10.1007/BF02122112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer E, Ribeiro R, Feitosa DP. Species and serovars of the genus Listeria isolated from different sources in Brazil from 1971 to 1997. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2000;95:615–620. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762000000500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YT, Ko WC, Chan YJ, Lu JJ, Tsai HY, Liao CH, Sheng WH, Teng LJ, Hsueh PR. Disease burden of invasive listeriosis and molecular characterization of clinical isolates in Taiwan, 2000–2013. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanek R, Grohn YT, Tauer LW, Wiedmann M. The cost and benefit of Listeria monocytogenes food safety measures. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2004;44:513–523. doi: 10.1080/10408690490489378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jallewar PK, Kalorey DR, Kurkure NV, Pande VV, Barbuddhe SB. Genotypic characterization of Listeria spp. isolated from fresh water fish. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;114:120–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Jinneman K, Stelma G, Smith BG, Lye D, Messer J, Ulaszek J, Evsen L, Gendel S, Bennett RW, Swaminathan B, Pruckler J, Steigerwalt A, Kathariou S, Yildirim S, Volokhov D, Rasooly A, Chizhikov V, Wiedmann M, Fortes E, Duvall RE, Hitchins AD. Natural atypical Listeria innocua strains with Listeria monocytogenes pathogenicity island 1 genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:4256–4266. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.7.4256-4266.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Seeliger HPR. Designation of a new type strain of Listeria monocytogenes. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1983;33:429. doi: 10.1099/00207713-33-2-429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph B, Przybilla K, Stuhler C, Schauer K, Slaghuis J, Fuchs TM, Goebel W. Identification of Listeria monocytogenes genes contributing to intracellular replication by expression profiling and mutant screening. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:556–568. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.556-568.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimpe A, Decostere A, Hermans K, Baele M, Haesebrouck F. Isolation of Listeria ivanovii from a septicaemic chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera) Vet Rec. 2004;154:791–792. doi: 10.1136/vr.154.25.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klumpp J, Fuchs TM. Identification of novel genes in genomic islands that contribute to Salmonella typhimurium replication in macrophages. Microbiology. 2007;153:1207–1220. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/004747-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM. Prokaryotic taxonomy and phylogeny in the genomic era: advancements and challenges ahead. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:504–509. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang Halter E, Neuhaus K, Scherer S. Listeria weihenstephanensis sp. nov., isolated from the water plant Lemna trisulca taken from a freshwater pond. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:641–647. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.036830-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq A, Clermont D, Bizet C, Grimont PA, Le Fleche-Mateos A, Roche SM, Buchrieser C, Cadet-Daniel V, Le Monnier A, Lecuit M, Allerberger F. Listeria rocourtiae sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:2210–2214. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.017376-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuit M. Human listeriosis and animal models. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:1216–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessing MP, Curtis GD, Bowler IC. Listeria ivanovii infection. J Infect. 1994;29:230–231. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(94)90914-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke K, Ruckerl I, Brugger K, Karpiskova R, Walland J, Muri-Klinger S, Tichy A, Wagner M, Stessl B. Reservoirs of Listeria species in three environmental ecosystems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:5583–5592. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01018-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomonaco S, Nucera D, Filipello V. The evolution and epidemiology of Listeria monocytogenes in Europe and the United States. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;35:172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik SV, Barbuddhe SB, Chaudhari SP. Listeric infections in humans and animals in the Indian subcontinent: a review. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2002;34:359–381. doi: 10.1023/A:1020051807594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley CM, McMillan K, Moore SC, Fegan N, Fox EM. Prevalence and characterization of foodborne pathogens from Australian dairy farm environments. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97:7402–7412. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-8735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLauchlin J, Rees C, et al. Genus I. Listeria Pirie 1940a 383AL. In: Vos P, et al., editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology, vol 3. 2. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 244–257. [Google Scholar]

- Mellin JR, Koutero M, Dar D, Nahori MA, Sorek R, Cossart P. Riboswitches. Sequestration of a two-component response regulator by a riboswitch-regulated noncoding RNA. Science. 2014;345:940–943. doi: 10.1126/science.1255083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith CD, Schneider DJ. An outbreak of ovine listeriosis associated with poor flock management practices. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1984;55:55–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero D, Bodero M, Riveros G, Lapierre L, Gaggero A, Vidal RM, Vidal M. Molecular epidemiology and genetic diversity of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from a wide variety of ready-to-eat foods and their relationship to clinical strains from listeriosis outbreaks in Chile. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:384. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno LZ, Paixao R, de Gobbi DD, Raimundo DC, Porfida Ferreira TS, Micke Moreno A, Hofer E, dos Reis CM, Matte GR, Matte MH. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of atypical Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua isolated from swine slaughterhouses and meat markets. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:742032. doi: 10.1155/2014/742032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najjar Z, Gupta L, Sintchenko V, Shadbolt C, Wang Q, Bansal N. Listeriosis cluster in Sydney linked to hospital food. Med J Aust. 2015;202:448–449. doi: 10.5694/mja14.00913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndahi MD, Kwaga JK, Bello M, Kabir J, Umoh VJ, Yakubu SE, Nok AJ. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Listeria monocytogenes and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from raw meat and meat products in Zaria, Nigeria. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2014;58:262–269. doi: 10.1111/lam.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negi M, Vergis J, Vijay D, Dhaka P, Malik SV, Kumar A, Poharkar KV, Doijad SP, Barbuddhe SB, Ramteke PW, Rawool DB (2015) Genetic diversity, virulence potential and antimicrobial susceptibility of Listeria monocytogenes recovered from different sources in India. Pathog Dis:73. doi:10.1093/femspd/ftv093 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Perrin M, Bemer M, Delamare C. Fatal case of Listeria innocua bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5308–5309. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5308-5309.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine L, Weaver RE, Carlone GM, Pienta PA, Rocourt J, Goebel W, Kathariou S, Bibb WF, Malcolm GB. Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 35152 and NCTC 7973 contain a nonhemolytic, nonvirulent variant. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2247–2251. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.11.2247-2251.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro-Cerda J, Kuhbacher A, Cossart P (2012) Entry of Listeria monocytogenes in mammalian epithelial cells: an updated view Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2 doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a010009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Qin QL, Xie BB, Zhang XY, Chen XL, Zhou BC, Zhou J, Oren A, Zhang YZ. A proposed genus boundary for the prokaryotes based on genomic insights. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:2210–2215. doi: 10.1128/JB.01688-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramage CP, Low JC, McLauchlin J, Donachie W. Characterisation of Listeria ivanovii isolates from the UK using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;170:349–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramdani-Bouguessa N, Rahal K. Neonatal listeriosis in Algeria: the first two cases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2000;6:108–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.00016-3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M, Rossello-Mora R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19126–19131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906412106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha PR, Lomonaco S, Bottero MT, Dalmasso A, Dondo A, Grattarola C, Zuccon F, Iulini B, Knabel SJ, Capucchio MT, Casalone C. Ruminant rhombencephalitis-associated Listeria monocytogenes strains constitute a genetically homogeneous group related to human outbreak strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:3059–3066. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00219-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocourt J, Hof H, Schrettenbrunner A, Malinverni R, Bille J. [Acute purulent Listeria seelingeri meningitis in an immunocompetent adult] Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1986;116:248–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Bolivar Z, Neuque-Rico MC, Poutou-Pinales RA, Carrascal-Camacho AK, Mattar S. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Listeria monocytogenes food isolates from different cities in Colombia. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011;8:913–919. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauders BD, Overdevest J, Fortes E, Windham K, Schukken Y, Lembo A, Wiedmann M. Diversity of Listeria species in urban and natural environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:4420–4433. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00282-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, Griffin PM. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States–major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:7–15. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.P11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scallan E, Crim SM, Runkle A, Henao OL, Mahon BE, Hoekstra RM, Griffin PM. Bacterial enteric infections among older adults in the United States: foodborne diseases active surveillance network, 1996-2012. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2015;12:492–499. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Mahon BE, Jones TF, Griffin PM. An assessment of the human health impact of seven leading foodborne pathogens in the United States using disability adjusted life years. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:2795–2804. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814003185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlech WF, III, Schlech WF, Haldane H, Mailman TL, Warhuus M, Crouse N, Haldane DJ. Does sporadic Listeria gastroenteritis exist? A 2-year population-based survey in Nova Scotia, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:778–784. doi: 10.1086/432724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid MW, Ng EY, Lampidis R, Emmerth M, Walcher M, Kreft J, Goebel W, Wagner M, Schleifer KH. Evolutionary history of the genus Listeria and its virulence genes. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2005;28:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder H, van Rensburg IB. Generalised Listeria monocytogenes infection in a dog. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1993;64:133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeliger HPR, Rocourt J, Schrettenbrunner A, Grimont PAD, Jones D. Listeria ivanovii sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1984;34:336–337. doi: 10.1099/00207713-34-3-336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeant ES, Love SC, McInnes A. Abortions in sheep due to Listeria ivanovii. Aust Vet J. 1991;68:39. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1991.tb09846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snapir YM, Vaisbein E, Nassar F. Low virulence but potentially fatal outcome-Listeria ivanovii. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17:286–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stea EC, Purdue LM, Jamieson RC, Yost CK, Truelstrup Hansen L. Comparison of the prevalences and diversities of Listeria species and Listeria monocytogenes in an urban and a rural agricultural watershed. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:3812–3822. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00416-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelling CR, Orsi RH, Wiedmann M. Complementation of Listeria monocytogenes null mutants with selected Listeria seeligeri virulence genes suggests functional adaptation of Hly and PrfA and considerable diversification of prfA regulation in L. seeligeri. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:5124–5139. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03107-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiri YD, Golz G, Meeyam T, Baumann MP, Kleer J, Chaisowwong W, Alter T. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Listeria monocytogenes on chicken carcasses in Bandung, Indonesia. J Food Prot. 2014;77:1407–1410. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tango CN, Choi NJ, Chung MS, Oh DH. Bacteriological quality of vegetables from organic and conventional production in different areas of Korea. J Food Prot. 2014;77:1411–1417. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallim DC, Barroso Hofer C, Lisboa Rde C, Victor Barbosa A, Alves Rusak L, Dos Reis CM, Hofer E (2015) Twenty years of Listeria in Brazil: occurrence of Listeria species and Listeria monocytogenes serovars in food samples in Brazil between 1990 and 2012 Biomed Res Int 2015:540204 doi:10.1155/2015/540204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vela AI, Fernandez-Garayzabal JF, Vazquez JA, Latre MV, Blanco MM, Moreno MA, de La Fuente L, Marco J, Franco C, Cepeda A, Rodriguez Moure AA, Suarez G, Dominguez L. Molecular typing by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of Spanish animal and human Listeria monocytogenes isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:5840–5843. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5840-5843.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volokhov D, George J, Anderson C, Duvall RE, Hitchins AD. Discovery of natural atypical nonhemolytic Listeria seeligeri isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:2439–2448. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2439-2448.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M, Melzner D, Bago Z, Winter P, Egerbacher M, Schilcher F, Zangana A, Schoder D. Outbreak of clinical listeriosis in sheep: evaluation from possible contamination routes from feed to raw produce and humans. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2005;52:278–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2005.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne LG, Brenner DJ, Colwell RR, Grimont PAD, Kandler O, Krichevsky MI, Moore LH, Moore WEC, Murray RGE, Stackebrandt E, Starr MP, Truper HG. Report of the ad hoc committee on reconciliation of approaches to bacterial systematics. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1987;37:463–464. doi: 10.1099/00207713-37-4-463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weller D, Andrus A, Wiedmann M, den Bakker HC. Listeria booriae sp. nov. and Listeria newyorkensis sp. nov., from food processing environments in the USA. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:286–292. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.070839-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wemekamp-Kamphuis HH, Karatzas AK, Wouters JA, Abee T. Enhanced levels of cold shock proteins in Listeria monocytogenes LO28 upon exposure to low temperature and high hydrostatic pressure. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:456–463. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.2.456-463.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedmann M, Czajka J, Bsat N, Bodis M, Smith MC, Divers TJ, Batt CA. Diagnosis and epidemiological association of Listeria monocytogenes strains in two outbreaks of listerial encephalitis in small ruminants. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:991–996. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.991-996.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedmann M, Arvik T, Bruce JL, Neubauer J, del Piero F, Smith MC, Hurley J, Mohammed HO, Batt CA. Investigation of a listeriosis epizootic in sheep in New York state. Am J Vet Res. 1997;58:733–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]