Inflammatory cell death, PANoptosis, mediated by cytokines in diverse cancer lineages inhibits tumor growth (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2022 Jan 21.

Abstract

Resistance to cell death is a hallmark of cancer. Immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint blockade therapy, drives immune-mediated cell death and has greatly improved treatment outcomes for some patients with cancer, but it often fails clinically. Its success relies on the cytokines and cytotoxic functions of effector immune cells to bypass the resistance to cell death and eliminate cancer cells. However, the specific cytokines capable of inducing cell death in tumors and the mechanisms that connect cytokines to cell death across cancer cell types remain unknown. Here, we analyzed expression of several cytokines that are modulated in tumors and found correlations between cytokine expression and mortality. Of several cytokines tested for their ability to kill cancer cells, only TNF-α and IFN-γ together were able to induce cell death in 13 distinct human cancer cell lines derived from colon and lung cancer, melanoma, and leukemia. Further evaluation of the specific programmed cell death pathways activated by TNF-α and IFN-γ in these cancer lines identified PANoptosis, a form of inflammatory cell death that was previously shown to be activated by contemporaneous engagement of components from pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis. Specifically, TNF-α and IFN-γ triggered activation of GSDMD, GSDME, caspase-8, caspase-3, caspase-7, and MLKL. Furthermore, the intra-tumoral administration of TNF-α and IFN-γ suppressed the growth of transplanted xenograft tumors in an NSG mouse model. Overall, this study shows that PANoptosis, induced by synergism of TNF-α and IFN-γ, is an important mechanism to kill cancer cells and suppress tumor growth that could be therapeutically targeted.

Keywords: Cancer, colon cancer, melanoma, lung cancer, leukemia, TNF-α, IFN-γ, PANoptosis, pyroptosis, apoptosis, necroptosis, cell death, cancer cell, tumor, caspase-1, caspase-3, caspase-7, caspase-8, gasdermin D, gasdermin E, RIPK3, MLKL

Introduction

Cancer is a group of diseases defined by abnormal growth of cells associated with pathological manifestations and significant morbidity and mortality globally (1). Because cancers are characterized by dysregulated cell death and inflammatory responses (2–4), many current therapeutic approaches aim to preferentially induce cell death in cancer cells (5–7). However, cancer cells acquire mutations that subvert the programmed cell death (PCD) pathways, making them refractory to anti-cancer therapies, and evasion of PCD mechanisms is one of the hallmarks of cancer (3). Therefore, gaining detailed understanding of these PCD mechanisms and identifying novel agonists remains a critical area of research to develop promising new strategies to treat cancers.

Elimination of transformed cancer cells by the immune system through PCD is an important checkpoint that can block cancer progression. Based on this strategy, immunotherapy such as immune checkpoint blockade therapy (ICT), which activates the immune-mediated killing of tumor cells by blocking suppressor proteins such as PD1 (programmed cell death protein 1) and CTLA4 (CTL antigen 4), has improved treatment outcomes for some patients with cancer (8). Yet, a significant proportion of patients remain refractory to ICT, primarily due to the failure to induce immunogenic cell death (8–10). The key effectors of ICT include cytotoxic T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, which can kill tumor cells directly, through cytotoxic perforins and granzymes, or indirectly, by releasing potent proinflammatory cytokines (11). However, cancer cells can subvert the granzyme- and perforin-mediated cell death mechanisms (12), making it particularly important to understand the mechanisms of cytokine-mediated killing of tumor cells. Among the cytokines, previous studies have indicated that TNF-α has potent anti-tumor activity; however, tumor cells have evolved evasion mechanisms that allow them to suppress the expression of TNF and to block its effector cell death function of apoptosis (13). TNF-α–mediated cytotoxicity can be augmented by Toll-like receptor (TLR) stimulation or by specific cytokines, including IFN-γ (14–18). Several models have been proposed to explain this augmentation and suggest that the synergism may exist at the level of transcriptional regulation of major histocompatibility complex I (MHC-I) expression and/or nitric oxide production to promote cell death (19, 20). Additionally, recent studies have indicated that tumor sensitivity to cell death is associated with both TNF-α and IFN-γ expression profiles, which are particularly important in the context of tumor resistance or loss of sensitivity to granzyme and perforin-mediated anti-tumor immune responses (11, 21). However, to date, the molecular mechanism of cell death induced by TNF-α and IFN-γ, or other cytokines, in human cancer cells remain unknown. Therefore, identifying and characterizing different cytokines capable of inducing PCD remains a critical area of research to develop promising strategies to treat cancers.

Several different PCD pathways have been described in recent years. The PCD pathway of apoptosis is a widely studied cell death mechanism executed by caspase-3 and −7 downstream of initiator caspases caspase-8/10 or −9 (22). Although loss of apoptosis is one of the founding hallmarks of cancer (3), cancer cells can also acquire resistance to apoptosis through genetic and epigenetic mechanisms (23–28). Mutations in tumor suppressor genes p53, PTEN and caspases often promote the development of tumorigenesis (29). When apoptosis is not effective, alternative PCD pathways of pyroptosis or necroptosis can be beneficial to eliminate cancer cells (30–35). Pyroptosis is executed by gasdermin family members (35–38), while necroptosis is mediated by RIPK3–dependent MLKL oligomerization (39, 40). Recent studies have shown extensive crosstalk among these PCD pathways. For instance, caspase-8 has been historically linked to immunologically silent death through apoptosis, and the tumor suppressive function of caspase-8 was attributed to its ability to drive apoptosis (41). However, several recent studies have found caspase-8 to be a critical component of PANoptosis (42, 43), which is defined as an inflammatory PCD pathway activated by specific triggers and regulated by the PANoptosome, a molecular scaffold for contemporaneous engagement of key molecules from pyroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis activated by specific triggers (14, 42, 44–57). PANoptosis has been implicated in infectious and autoinflammatory diseases, but its specific role in human cancer cells remains to be defined.

In this study, we showed that the expression profiles of key inflammatory cytokines are modulated in patients with cancer, and that the expressions of multiple cytokines are associated with disease severity. When we analyzed the effects of these differentially expressed cytokines in human cancer cell lines derived from colon and lung cancer, melanoma, and leukemia, we found that only TNF-α and IFN-γ induced cell death in all the lines tested. Mechanistically, combined treatment of TNF-α and IFN-γ activated PANoptosis. Inhibition of the unique upstream regulatory JAK signaling, but not nitric oxide (NO) (42), prevented cell death induced by TNF-α and IFN-γ. In vivo, the intra-tumoral administration of TNF-α and IFN-γ reduced tumor growth in transplanted COLO-205 cancer cells. Identifying the triggers of PANoptosis in cancer cells and the underlying mechanisms provides important insights for designing and improving therapeutic approaches.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG, JAX stock #005557) mice were acquired and maintained at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH). All mice were housed at SJCRH animal facilities under strict specific pathogen-free conditions (sterilized water, food, bedding and cages), and aseptic handling techniques were used to avoid any unwanted infections. Animal studies were conducted under protocols approved by St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital’s committee on the use and care of animals.

Analysis of TCGA cytokine expression data from patients with colon cancer

Cytokine expression and survival data for patients with colorectal cancer from the Cancer Genome Atlas Program were downloaded from Human Protein Atlas (58). Normal expression data were downloaded from Genomic Data Commons Data Portal of National Cancer Institute (59). The heatmap was generated using Morpheus (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus). Survival analysis and graph generation was done in GraphPad Prism.

Cell culture and stimulation

The fully authenticated human NCI-60 cancer cell lines (NCI, Bethesda, MD, USA) used in this study were cultured in RPMI media (Corning, 10–040-CV) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Cancer cells were seeded a day before stimulation. On the day of stimulation, the cells were washed once with warm and sterile DPBS, followed by treatment with different cytokines for 48 h. The concentration of the cytokines used were 25 ng/mL of IL-6 (Peprotech, 200-06), IL-8 (Peprotech, 200-08M), IL-18 (R&D, B001-5), IL-15 (Peprotech, 200-15), IL-1α (Peprotech, 200-01A), IL-1β (Peprotech, 200-01B), IL-2 (Peprotech, 200-02), TNF-α (Peprotech, 300-01A), IFN-γ (Peprotech, 300-02). For the inhibition of nitric oxide (NO), cancer cells were co-treated with 1 mM of L-NAME hydrochloride (TOCRIS, 0665) or 100 μM of 1400W dihydrochloride (Enzo Life Sciences, ALX-270–073-M005) along with the cytokines. For inhibition of the JAK signaling pathway, the cancer cells were co-treated with 5 μM of baricitinib (Achemblock, K12360) all through the experiment.

Generation of _IRF1_-knockout HCT116 cells using CRISPR–Cas9 system

HCT116 colon cancer cells (ATCC® CCL-247™; fully authenticated by ATCC) were transduced with lentiviral Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9-GFP and flow sorted for GFP-positive cells with optimal expression levels of Cas9-GFP. Lentiviral particles expressing two different IRF1 guide RNAs (gRNAs, 5′-CTTGGCAGCATGCTTCCATGGG-3′ and 5′-TTGCTCTTAGCATCTCGGCTGG-3′) were generated by using the HEK293T packaging system. The HEK293T cells were transfected with IRF1 guide RNAs, along with the packaging plasmids pPAX2 and pMD2. Lentiviral particles were collected 48 h post-transfection. The HCT116 cells that express the Cas9-GFP protein were transduced with IRF1 gRNA lentiviral particles in combination with 8 μg/ml polybrene for 24 h. The HCT116 cells carrying successful integration of the gRNAs were selected using puromycin (2.5 μg/ml). The IRF1 knockout and the corresponding control Cas9-expressiong wild-type HCT116 cells were used in further experiments.

IncuCyte cell death analysis

The kinetics of cell death were measured using a two-color IncuCyte S3 imaging system (Essen Biosciences). Different lines of NCI-60 cancer cells were seeded in 12-well (0.25 × 106 cells/well) or 24-well (0.125 × 106 cells/well) cell cultures plates and stimulated with indicated cytokines in the presence of the cell-impermeable DNA binding fluorescent dye SYTOX Green (S7020; Life Technologies, 20 nM) following the manufacturer’s protocol. A series of images were acquired at 1-hour time intervals for up to 48 h post-treatment with a 20× objective and analyzed using the IncuCyte S3 software, which allows precise analysis of the number of dye-positive dead cells present in each image. A minimum of three images per well was taken for the analysis of each time point. Dye-positive dead-cell events for each of the cancer cells were plotted using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 software.

Western blotting

For the Western blotting analysis of caspases, cancer cells were seeded a day before stimulation at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells/well in 6-well cell culture plates. The proteins from the indicated cell types were collected by combining cell lysates with culture supernatants with caspase lysis buffer (with 1× protease inhibitors, 1× phosphatase inhibitors, 10% NP-40, and 25 mM DTT) and 4× sample loading buffer (containing SDS and 2-mercaptoethanol). For the Western blot analysis of all other signaling proteins, the cells were lysed in RIPA buffer, supplemented with protease inhibitor and phosphoStop as per the manufacturer’s instructions and sample loading buffer. Samples were denatured by boiling for 10 min at 100°C and separated using SDS-PAGE–followed by the transfer on to Amersham Hybond P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (10600023; GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and immunoblotted with primary antibodies against IRF1 (rabbit monoclonal Ab [mAb], 8478; Cell Signaling Technology), STAT1 (rabbit mAb, 14994; Cell Signaling Technology), caspase-1 (rabbit polyclonal antibody [pAb], 22915-1-AP; Proteintech), caspase-3 (rabbit pAb, 9662; Cell Signaling Technology), cleaved caspase-3 (rabbit pAb, 9661; Cell Signaling Technology), caspase-7 (rabbit pAb, 9492; Cell Signaling Technology), gasdermin D (rabbit pAb, 96458; Cell Signaling Technology), GSDME/DFNA5 (rabbit mAb, ab215191; Abcam), caspase-8 (mouse mAb, clone 12F5, ALX-804-242-C100; Enzo Life Sciences), MLKL (rabbit mAb, clone EPR17514, ab184718; Abcam), RIPK3/RIP3 (rabbit pAb, NBP2-24588; Novus Biologicals) and β-actin (rabbit mAb, 13E5, 4970; Cell Signaling Technology) followed by secondary anti-rabbit or anti-mouse HRP antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), as previously described (60).

Membrane proteins and MLKL oligomerization.

The membrane proteins were isolated using the Thermo Scientific Mem-PER Plus Membrane Protein Extraction Kit (Catalog number #89842). For Western blot analysis of MLKL oligomerization (activation), the cells were lysed in NP-40 lysis buffer (1.0% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, and 50 mM HEPES) containing complete protease inhibitors and phospho-STOP (Roche) and divided in two fractions. One half of the lysate was mixed with a sample loading dye containing the disulfide bond-reducing reagent 2-BME (2-Mercaptoethanol, 25 mM) and the other half with a sample buffer without any reducing agents. Both of these lysate preparations were boiled for 10 min at 100°C and subjected to immunoblotting analysis of total MLKL protein.

NSG mouse xenograft tumor model

The NSG mice (NOD/SCID-gamma null mouse strain that lacks IL-2-γ chain) were used as the model recipients for the subcutaneous transplantation of human COLO-205 cancer cells. Briefly, 8- to 10-week-old NSG mice were shaved on their lower backs and transplanted with 2 × 106 COLO-205 cells in 200 μl of medium prepared by mixing (1:1) RPMI and Matrigel (BD Bioscience, 354230). The mice were monitored regularly for engraftment and growth of COLO-205 cancer cell tumors. The recipient mice were divided into four groups and treated intratumorally with injection of the indicated cytokines or PBS (groups: 1) PBS, 2) TNF-α, 3) IFN-γ, or 4) TNF-α and IFN-γ) on day 12, 14 and 16 post-transplantation of the tumor cells. The tumor growth was monitored and measured using digital calipers, and the volume of the tumors were calculated using the formula: volume = (length × width2) × ½.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism version 5.0 and 8.0 softwares were used for data analyses. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by t tests (two-tailed) or Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests for two groups, and one-way ANOVA (with Dunnett’s or Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests) for three or more groups. The number of experimental repeats and technical replicates are indicated in the corresponding figure legends; n in the figure legends represents the number of biological replicates used in the experiments. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and is represented as *, ns, not significant.

Results

TNF-α and IFN-γ cooperatively induce cancer cell death

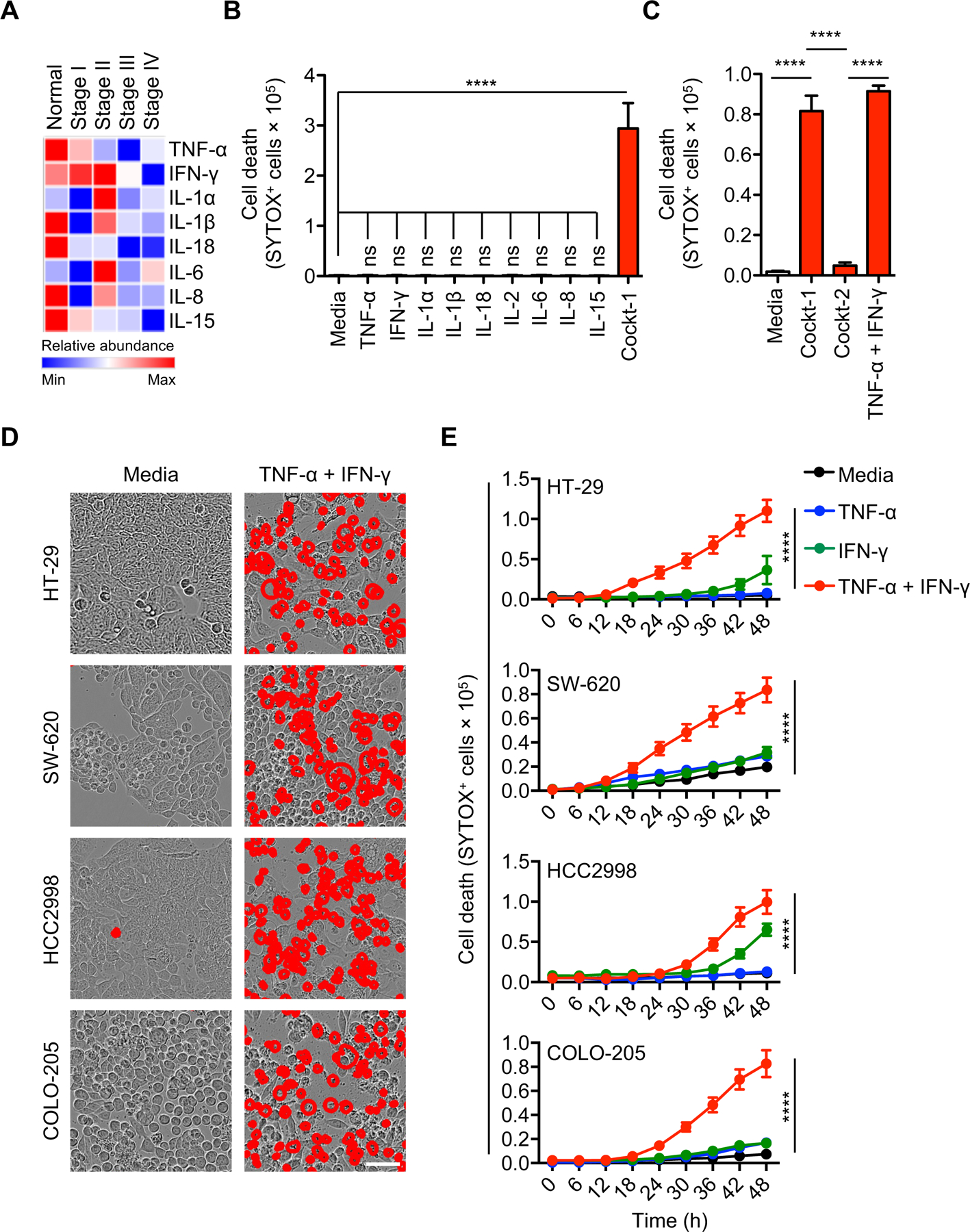

Expression and modulation of cytokines have critical functions associated with tumor growth and therapeutic outcomes (61–63). To determine which proinflammatory cytokines are highly modulated in tumors, we re-analyzed a publicly available TCGA dataset from healthy volunteers and patients with different stages of colorectal cancer (CRC; Stage I to IV, low to high grade tumors). The analyses showed altered expression of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-18, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-15 in the tumor microenvironment (TME) (Figure 1A). We also observed that the decreased expression of proinflammatory cytokines was often associated with a decreased probability of survival (Supplementary Figure 1). These findings suggested a strong inverse correlation between proinflammatory cytokine profiles and cancer progression. However, the role of specific cytokines in modulating tumorigenesis is not clear. It is possible that impaired cell death in the absence of proinflammatory cytokines contributes to the reduced probability of survival. To investigate this possibility, we treated the human colon cancer cell line HCT-116 with the proinflammatory cytokines that were differentially modulated in the TME of patients with CRC. We did not detect cell death in response to any of these cytokines individually (Figure 1B). However, combining all the selected cytokines, referred to as cocktail-1 (Cockt-1), induced robust cancer cell death (Figure 1B), suggesting that synergistic cytokine signaling is required for this process. Previously, we have identified that the combination of TNF-α and IFN-γ induces robust cell death in murine immune cells (42). Similarly, we found that TNF-α and IFN-γ alone or the cytokine combination that contained TNF-α and IFN-γ (Cockt-1), but not a cytokine combination which lacks both TNF-α and IFN-γ (Cockt-2), induced human cancer cell death (Figure 1C). These results indicate that TNF-α and IFN-γ are required to trigger cancer cell death in HCT-116.

Figure 1: Concomitant treatment of TNF-α and IFN-γ triggers robust cell death in NCI-60 colon cancer cells.

(A) Heat map representing the levels of inflammatory cytokines in the tumor microenvironment relative to levels in healthy tissue. (B-C) Quantification of the cell death in HCT-116 colon cancer cells treated with media or the indicated cytokines and assessed in culture 48 h post-stimulation. “Cocktail-1” (Cockt-1) is a combination prepared by mixing all the individual cytokines used in this panel (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-18, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-15); Cocktail-2 (Cockt-2) is same as Cockt-1, except that it lacks TNF-α and IFN-γ (contains L-1α, IL-1β, IL-18, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-15). (D) Representative images of cell death detected by IncuCyte imaging analysis of cancer cells treated with TNF-α and IFN-γ at 48 h post-treatment. Scale bar, 50 μM. (E) Time-course analysis of cell death of cancer cells treated with TNF-α alone, IFN-γ alone, or TNF-α plus IFN-γ, assessed over the course of 48 h post-stimulation. Data are representative of three independent experiments (B-E). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (B,C,E). ****P < 0.0001. Analyses were performed using the t test (B-C) or the two-way ANOVA (E).

We next sought to determine the efficacy of the TNF-α and IFN-γ combination in triggering cell death in a broad range of human colon cancer cell lines. The NCI-60 colon cancer cell lines (HT-29, SW-620, HCC2998, COLO-205) were susceptible to TNF-α and IFN-γ co-treatment–mediated cell death (Figure 1D). To study the relative contribution of TNF-α or IFN-γ in inducing cell death, we treated the NCI-60 colon cancer lines with TNF-α or IFN-γ alone, or in combination. The cell death induced by co-treatment of TNF-α and IFN-γ was more robust than that induced by individual treatment with TNF-α or IFN-γ (Figure 1E). We further extended our findings to other cancer lines from the NCI-60 panel. Comprehensive screening demonstrated that TNF-α and IFN-γ co-treatment induced cell death in a range of cancer cells, including the NCI-60 melanoma lines SK-MEL-2, M14, SK-MEL-5 and UACC-62 (Supplementary Figure 2, A and B); lung cancer lines HOP-92 and H226 (Supplementary Figure 2, C and D); and leukemia lines HL-60 and RPMI-8226 (Supplementary Figure 2, E and F). These findings suggest that various cancer cells may have varying sensitivities to TNF-α and IFN-γ individually, but the combined treatment triggers robust cell death across a wide range of cancer cells.

TNF-α and IFN-γ induce PANoptosis in cancer cells

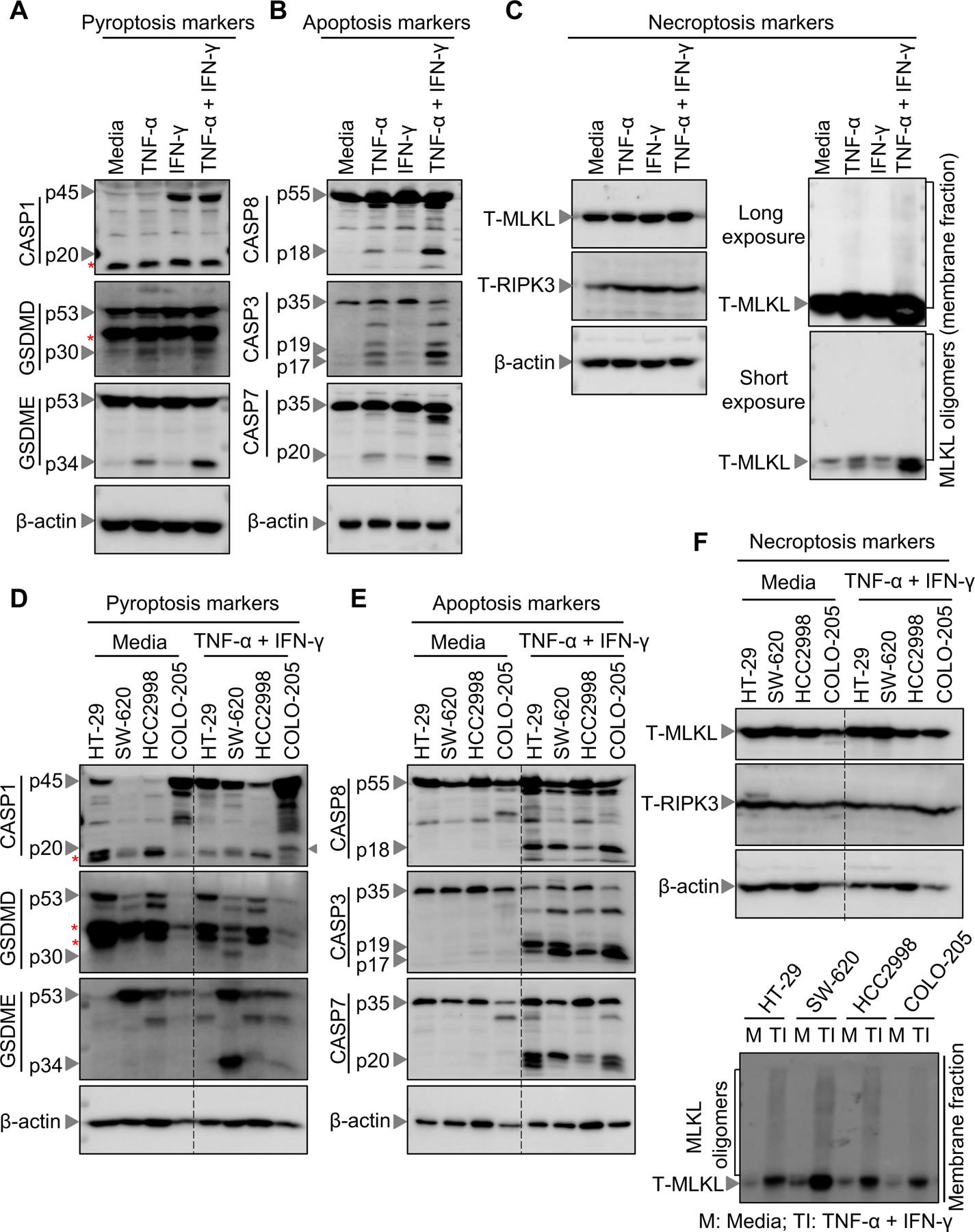

We have previously demonstrated that synergism of TNF-α and IFN-γ induces inflammatory cell death, PANoptosis, by activating gasdermin E (GSDME), caspase-8, −3 and −7, and MLKL in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (42). To determine whether PANoptosis was activated in cancer cells, we first analyzed the biochemical markers of PANoptosis in colon cancer lines. Consistent with the cell death data (Figure 1), we found that the combination of TNF-α plus IFN-γ activated PANoptosis in the HCT-116 colon cancer cells, while either cytokine treatment alone induced only weak activation of these biochemical markers (Figure 2, A–C).

Figure 2: TNF-α and IFN-γ treatment triggers PANoptotic cell death in human cancer cells.

(A-C) Western blot analysis of PANoptosis components in HCT-116 colon cancer cells treated with cytokines as indicated and assessed in culture at 48 h post-stimulation. (A) Western blot analysis of the pyroptosis markers: pro- (P45) and activated (P20) caspase-1 (CASP1), pro- (P53) and activated (P30) gasdermin D (GSDMD), and pro- (P53) and activated (P34) gasdermin E (GSDME). (B) Western blot analysis of the apoptosis markers: pro- (P55) and cleaved caspase-8 (CASP8; P18), pro- (P35) and cleaved caspase-3 (CASP3; P19 and P17), and pro- (P35) and cleaved caspase-7 (CASP7; P20). (C) Western blot analysis of necroptosis components: total MLKL (T-MLKL), MLKL oligomers, and total RIPK3 (T-RIPK3). (D-F) Western blot analysis of PANoptosis components in NCI-60 colon cancer cells treated with cytokines as indicated and assessed in culture at 48 h post-stimulation. (D) Western blot analysis of the pyroptosis markers: pro- (P45) and activated (P20) CASP1, pro- (P53) and activated (P30) GSDMD, and pro- (P53) and activated (P34) GSDME. (E) Western blot analysis of the apoptosis markers: pro- (P55) and cleaved CASP8 (P18), pro- (P35) and cleaved CASP3 (P19 and P17), and pro- (P35) and cleaved CASP7 (P20). (F) Western blot analysis of necroptosis components: T-MLKL, MLKL oligomers, and T-RIPK3. Western blot of β-Actin was used as loading control. Asterisks indicate non-specific bands. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments (A-F).

We then evaluated the effect of the TNF-α and IFN-γ combination in different cancer cell lines to characterize the mechanism of cell death. Without cytokine treatment, we detected robust expression of caspase-1 in the colon cancer lines HT-29 and COLO-205, but not in SW-620 or HCC2998 (Figure 2D). TNF-α and IFN-γ treatment further upregulated the expression of caspase-1 in all the colon cancer lines tested (Figure 2D). We also detected active caspase-1 in TNF-α and IFN-γ–treated COLO-205 cells (Figure 2D), indicating that pyroptosis may be occurring in these cells. However, the expression of the pyroptotic executioner GSDMD was not observed in COLO-205 cells, suggesting that COLO-205 cells cannot undergo GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis (Figure 2D). Similar to the varied caspase-1 expression, the expression of GSDMD and GSDME was also varied across the different cell lines. Furthermore, robust activation of GSDME, another executioner of pyroptosis known to be cleaved by caspase-3 (35, 64), was observed in response to TNF-α and IFN-γ treatment in HCT-116 and SW-620 cells, whereas HCC2998 and COLO-205 cancer cells showed only minor cleavage (Figure 2, A and D), confirming that pyroptotic effectors are activated in these cells. In addition, we observed proteolytic cleavage of apoptotic caspases including the upstream caspase-8 and the downstream caspase-3 and −7 in all 5 colon cancer lines (Figure 2, B and E), indicating a universal susceptibility of these cancer cell lines to TNF-α and IFN-γ treatment-induced apoptotic effector activation. Next, we examined the role of TNF-α and IFN-γ in inducing necroptotic effectors by assessing the oligomerization of MLKL as a measure of its activation. We observed higher order oligomers of MLKL in cells treated with TNF-α and IFN-γ (Figure 2, C and F). Additionally, the expression of RIPK3 and MLKL was intact in all these colon cancer lines. Furthermore, we observed that TNF-α and IFN-γ co-treatment induced PANoptosis in a range of other cancer cells, including the NCI-60 melanoma lines SK-MEL-2, M14, SK-MEL-5 and UACC-62 (Supplementary Figure 3, A–C); lung cancer lines HOP-92 and H226, and leukemia lines HL-60 and RPMI-8226 (Supplementary Figure 3, D–F). Overall, the contemporaneous activation of pyroptotic, apoptotic, and necroptotic effectors observed in these cell lines indicate that TNF-α and IFN-γ induce robust PANoptosis in a wide variety of cancer cells.

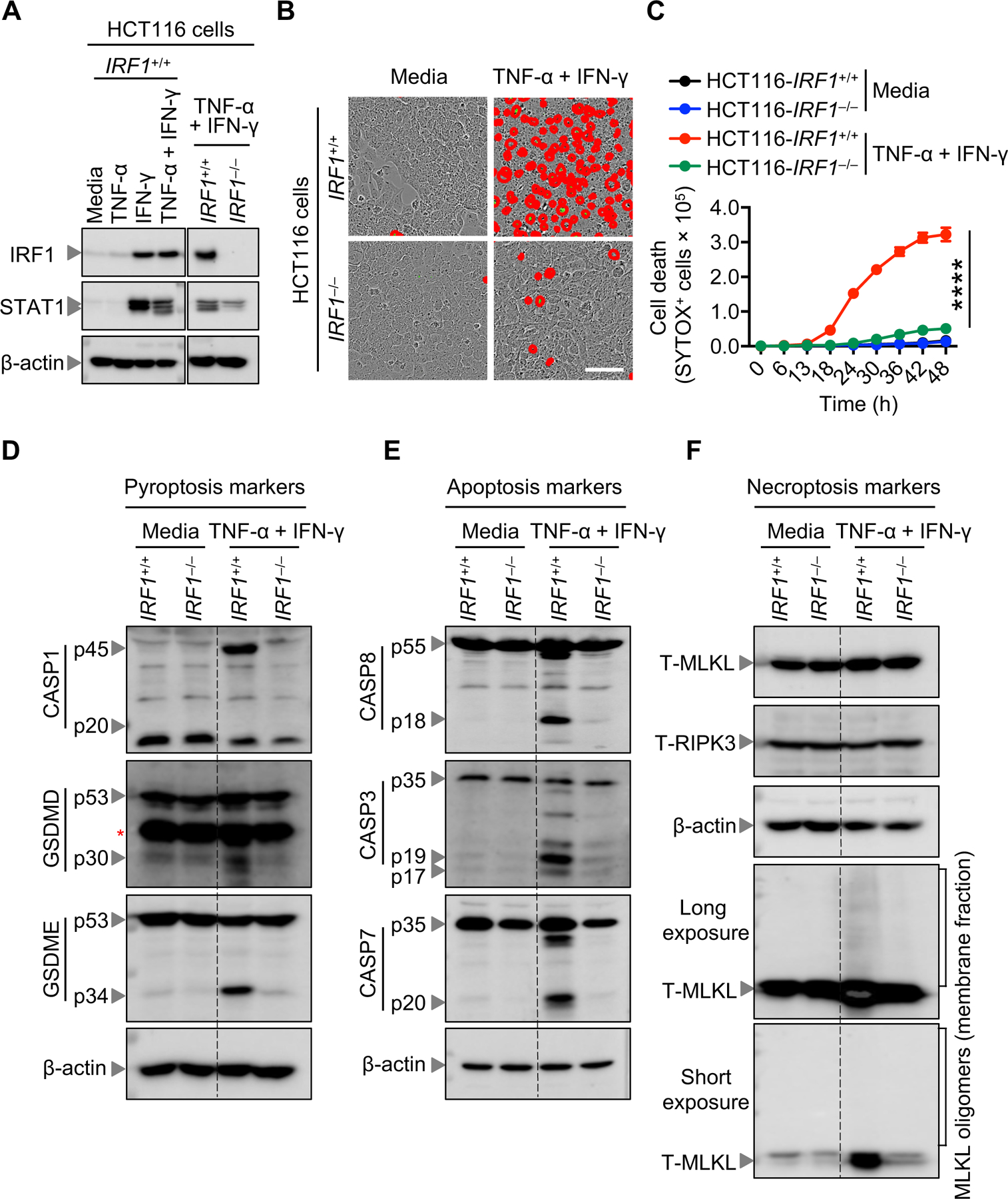

TNF-α and IFN-γ drive IRF1-dependent, but iNOS-independent cancer cell death

We previously observed that TNF-α plus IFN-γ treatment induces death of immune cells in murine BMDMs through the JAK/STAT1-IRF1-iNOS signaling axis (42). To investigate whether TNF-α and IFN-γ treatment utilizes a similar mechanism to induce human cancer cell death, we generated HCT-116 cells deficient in IRF1 and treated HCT-116 control and _IRF1_-deficient HCT-116 colon cancer cells with the combination of TNF-α and IFN-γ (Figure 3A). The cell death induced by TNF-α and IFN-γ was significantly reduced in _IRF1_-deficient HCT-116 colon cancer cells compared to HCT-116 control cancer cells (Figure 3, B and C). Importantly, the reduced cleavage of GSDMD and GSDME and caspase-8, −3 and −7, and the reduction in high order oligomers of MLKL from the cell membrane fraction in _IRF1_-deficient HCT-116 colon cancer cells confirms that IRF1 is required for TNF-α plus IFN-γ treatment-induced PANoptosis (Figure 3, D–F).

Figure 3: TNF-α and IFN-γ treatment triggers IRF1-dependent PANoptotic cell death.

(A) Western blot analysis of IRF1 and STAT1 proteins in _IRF1_−/− and the corresponding control IRF1+/+ HCT-116 colon cancer cells, after treatment with indicated cytokines for 48 h. (B) Representative images of cell death detected by IncuCyte image analysis of indicated HCT-116 cells, treated with TNF-α and IFN-γ at 48 h post-treatment. Scale bar, 50 μM. (C) Quantitative real-time analysis of cell death in wild-type and _IRF1_-deficient HCT-116 colon cancer cells co-treated with TNF-α and IFN-γ. (D-F) Western blot analysis of PANoptosis components in wild-type and _IRF1_-deficient HCT-116 cells treated with TNF-α and IFN-γ for 48 h. (D) Western blot analysis of the pyroptosis markers: pro- (P45) and activated (P20) caspase-1 (CASP1), pro- (P53) and activated (P30) gasdermin D (GSDMD), and pro- (P53) and activated (P34) gasdermin E (GSDME). (E) Western blot analysis of the apoptosis markers: pro- (P55) and cleaved caspase-8 (CASP8; P18), pro- (P35) and cleaved caspase-3 (CASP3; P19 and P17), and pro- (P35) and cleaved caspase-7 (CASP7; P20). (F) Western blot analysis of necroptosis components: total MLKL (T-MLKL), total RIPK3 (T-RIPK3), and MLKL oligomers. Western blot of β-Actin was used as loading control. Asterisks indicate non-specific bands. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments (A-F). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (C). ****P < 0.0001. Analysis was performed using the two-way ANOVA (C).

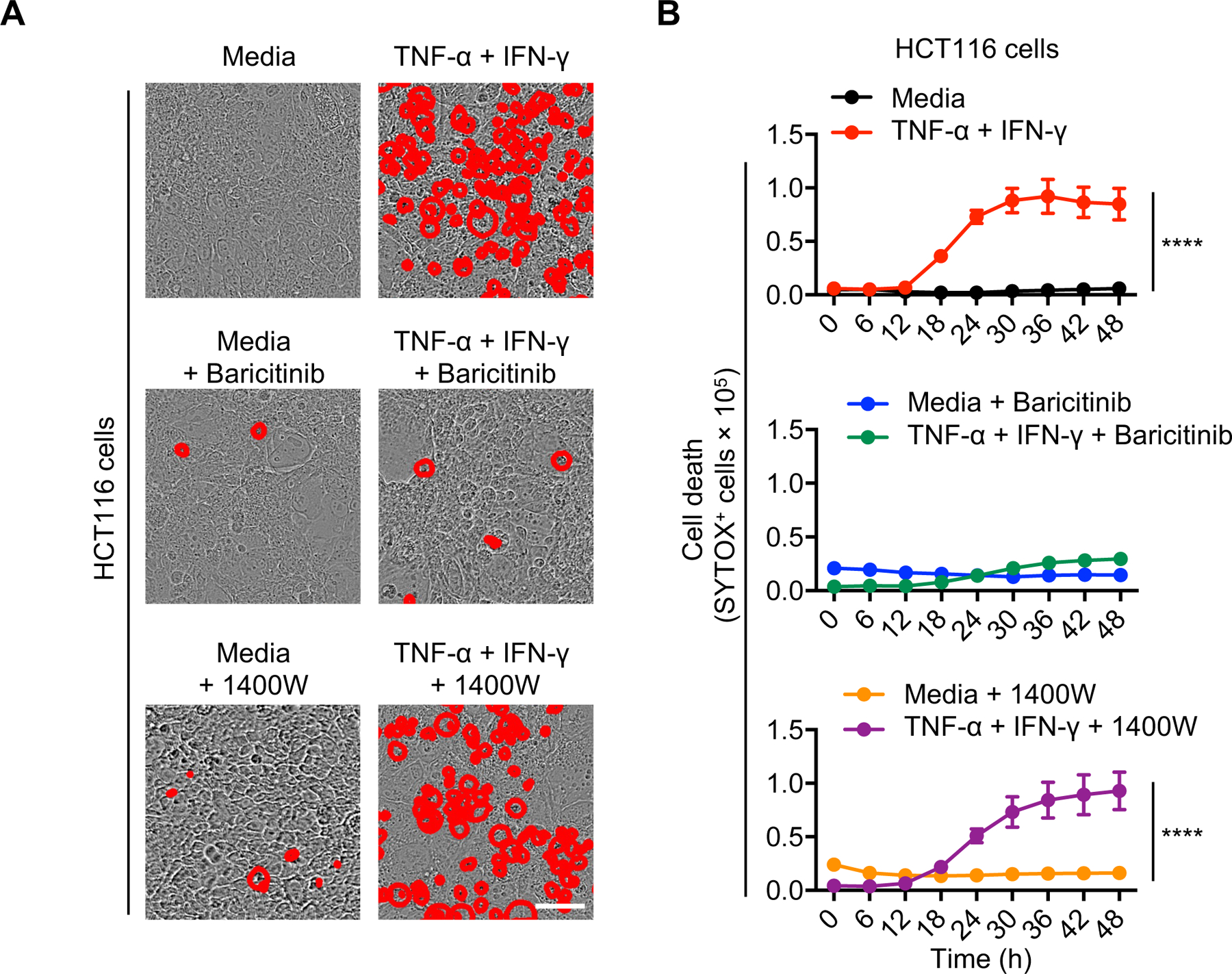

Previously we have shown that signaling through JAK-STAT1-IRF1 is required for NO production, which in turn induces PANoptosis in macrophages (42). To investigate the role of the JAK-STAT1 pathway in PANoptosis induced by TNF-α and IFN-γ, we treated cancer cells with the JAK inhibitor baricitinib. Baricitinib-treated cancer cells showed reduced cell death (Figure 4, A and B), suggesting that the JAK-STAT1 pathway is required for cancer cell death. To further investigate the role of NO in this process, we treated cancer cells with the NO inhibitors L-NAME (NOS inhibitor) or 1400W (iNOS inhibitor) and monitored cell death. In contrast to their effect in macrophages (42), NO inhibitors failed to inhibit the cancer cell death induced by TNF-α plus IFN-γ treatment both in colon cancer (Figure 4, A and B) and melanoma cell lines (Supplementary Figure 4, A and B). Together, these results suggest that the JAK-STAT1-IRF1 signaling axis plays a key role in driving TNF-α and IFN-γ treatment-induced cancer cell PANoptosis, while NO is dispensable for this process.

Figure 4: JAK inhibition, but not nitric oxide inhibition, prevents the TNF-α and IFN-γ-dependent cancer cell death.

Representative images (A) or time course analyses (B) of cell death detected by IncuCyte imaging of human HCT-116 colon cancer cells treated for 48 h with TNF-α and IFN-γ, in the presence or absence of the JAK1 inhibitor, baricitinib, or inducible nitric oxide inhibitor, 1400W. Scale bar, 50 μM. Data are representative of two independent experiments (A-B). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (B). ****P < 0.0001. Analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA (B).

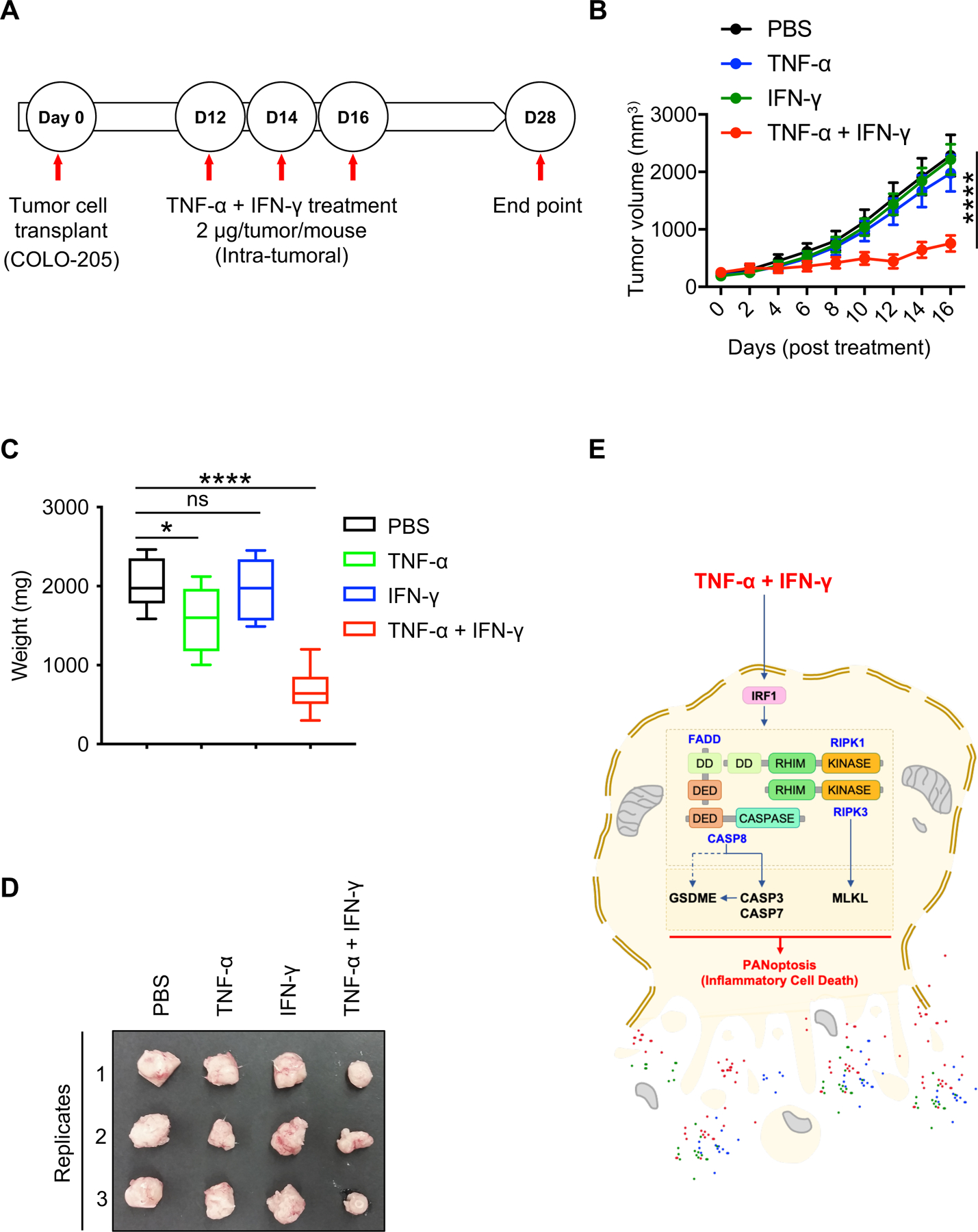

TNF-α plus IFN-γ suppresses tumor growth in vivo

We next examined the therapeutic potential of TNF-α and IFN-γ to prevent tumor development in tumor-bearing NSG mice (Figure 5A). We observed that intra-tumoral administration of TNF-α alone provided a minor but significant reduction in tumor weight, while combined intra-tumoral injection of TNF-α and IFN-γ resulted in a larger reduction in tumor weight and significantly reduced the tumor volume (Figure 5, B–D). Together, these findings demonstrate that administration of IFN-γ promotes robust JAK-STAT–dependent IRF1 expression and potentiates TNF-α–mediated cell death, PANoptosis, (Figure 5E), and that the TNF-α and IFN-γ combination was superior to single agents alone in treating the established tumors. These findings provide a proof of concept for the applicability of TNF-α and IFN-γ–mediated cell death for the treatment of tumors in vivo.

Figure 5: TNF-α and IFN-γ treatment suppresses transplanted tumor growth in vivo.

(A) Diagram representing the NSG mouse model of tumorigenesis. (B) Time course analysis of tumor volume of transplanted COLO-205 cell tumors in NSG mice. (C) Weight of the tumors measured at the endpoint of the experiment, 28 post-inoculation and 16 days post-treatment with TNF-α and IFN-γ. (D) Representative images of the tumors that were collected at day 28 post-inoculation. (E) Depiction of the TNF-α plus IFN-γ–induced PANoptosis pathway based on the experimental findings from the current study. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (B,C). *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001. Analyses were performed using the one-way ANOVA (B) or the t test (C).

Discussion

Improved understanding of the mechanisms and novel agonists that can drive cell death in cancer cells is essential for developing new targeted therapeutics. Our finding here that the combination of TNF-α and IFN-γ acts as a potent inducer of PANoptosis in a range of different cancer cell types provides important mechanistic insights. Inhibition of JAK signaling significantly reduced the cytotoxic effects of TNF-α and IFN-γ treatment. However, in contrast to what was previously observed in murine macrophages (42), TNF-α plus IFN-γ–induced PANoptosis does not rely on the NO pathway to kill the human cancer cells. Additionally, TNF-α plus IFN-γ treatment activated caspase-1 in human COLO-205 cancer cells. Consistent with these in vitro findings, we also found that concomitant treatment of TNF-α and IFN-γ provided tumor suppressive effects in an in vivo xenograft model of tumorigenesis.

Studies using proinflammatory cytokines or the inhibition of these cytokines for disease treatment have indicated the feasibility and potential for cytokine modulation as a therapeutic strategy (65–68). In cancer specifically, TNF-α has been shown to augment the efficacy of birinapant, a SMAC (second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases) mimetic and antagonist of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAP)-induced death, in triple-negative breast cancer cells (69). Additionally, early studies focused on IFN-γ also provided evidence for its critical role in immunological rejection of tumors (70, 71). However, clinical trials using systemic delivery of cytokines for cancer treatment have historically identified several side effects (52). Therefore, pre-clinical and clinical research protocols are being developed for targeted and local delivery methods to reduce toxicities while enhancing efficacy (72, 73). Our findings here show that TNF-α plus IFN-γ is effective against a wide range of tumor cell types including colon and lung cancer, melanoma and leukemias and that this combination suppressed tumor growth via intratumoral delivery in vivo, highlighting its potential for clinical applications.

We identified that individual treatments using either TNF-α or IFN-γ alone were not sufficient to induce cell death in cancer cells. However, a range of human cancer cell lines were susceptible to the PANoptotic cell death induced by the combination of TNF-α and IFN-γ. PANoptosis is a form of inflammatory cell death that utilizes molecular components from pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis but that cannot be accounted for by any of those three pathways alone. These observations are significant, as engaging the versatile multi-cell death modality PANoptosis is highly effective in bypassing the resistance to cell death in cancer cells. The intrinsic plasticity in PANoptosis, potentiated by the PANoptosome and the engagement of effectors from multiple PCDs, allows a cell to proceed with inflammatory cell death even when a key molecule from pyroptosis, apoptosis or necroptosis is inhibited, mutated, or repressed. Moreover, the cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ represent two classic markers of activated cytotoxic T cells which play central roles in eliminating tumor cells in vivo, suggesting potential implications for the development of anti-cancer therapeutic approaches. While several cytokines were modulated in the TME in patients, the TNF-α and IFN-γ combination was unique; all other cytokines tested failed to induce any significant cancer cell death, both in isolation and in combination. Moreover, other cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6 are detrimental and may even promote tumorigenesis (66, 68, 74–81). Lack of detectable levels of cell death in response to these other cytokines could be one of the reasons they fail to provide consistent results in pre-clinical and clinical applications. An additional contributing factor may be that acute treatment with proinflammatory cytokines promotes cytotoxic and anti-tumor responses, while chronic exposure drives a tolerogenic tumor-promoting microenvironment (82). In line with this, we found that acute treatment with TNF-α and IFN-γ substantially reduced tumor growth in vivo. Additionally, previous therapeutic approaches administering either TNF-α or IFN-γ alone have failed, most often due to inconsistent results, toxicities and/or lack of efficacy (83–87). Together, this suggests that the anti-tumor response is largely dependent on the synergism between TNF-α and IFN-γ.

While the TNF-α and IFN-γ combination effectively reduced tumor growth in our in vivo model, the tumors continued to grow gradually and finally emerged at extended time points, suggesting that resistance mechanisms may develop. The resistance mechanisms may help the cancer cells escape TNF-α and IFN-γ treatment-induced cell death in immune-deficient NSG mice. However, the outcome may be different in immunocompetent animals. Indeed, cell death is known to augment the development of T cells and other adaptive immune responses that promote durable tumor regression (88–92). For instance, during ICT, cytotoxic T cells and NK cells produce potent proinflammatory cytokines (11). Furthermore, the success of ICT is strongly associated with TNF-α, IFN-γ, and other proinflammatory cytokines, and low expression of TNF-α in tumors correlates with poor outcomes in non-responding patients (93). Additionally, the development of lung cancer is associated with decreased expression of proinflammatory cytokines by the cytotoxic T cells and NK cells (94). These early findings indicate that disrupting the resistance to cell death through cytokine signaling has tremendous potential to extend the therapeutic benefits of ICT to diverse patients and cancer types (10, 95). Therefore, it is possible that the highly inflammatory nature of the PANoptotic cell death induced by TNF-α and IFN-γ would provide robust activation of anti-cancer immunity in immunocompetent animals to completely eradicate tumors and aid in the development of long-lasting anti-tumor immunity.

Overall, our study identifies the combination of TNF-α and IFN-γ as an effective approach to induce cell death, PANoptosis, in cancer cells. These findings lay a foundation for identifying new strategies to target different cancer types and develop more effective anti-cancer regimens.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figures 1-4

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca Tweedell, PhD, for scientific editing and writing support.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants CA253095, AR056296, AI160179, AI124346 and AI101935 and by American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC) to T. D.K. The funding agencies had no role in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, and Jemal A 2018. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68: 394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green DR, and Evan GI 2002. A matter of life and death. Cancer Cell 1: 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, and Weinberg RA 2000. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 100: 57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanahan D, and Weinberg RA 2011. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144: 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernier J, Hall EJ, and Giaccia A 2004. Radiation oncology: a century of achievements. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 737–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carneiro BA, and El-Deiry WS 2020. Targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 17: 395–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pekarsky Y, Balatti V, and Croce CM 2018. BCL2 and miR-15/16: from gene discovery to treatment. Cell Death Differ 25: 21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellman I, Coukos G, and Dranoff G 2011. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 480: 480–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leach DR, Krummel MF, and Allison JP 1996. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science 271: 1734–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, and Ribas A 2017. Primary, Adaptive, and Acquired Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell 168: 707–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kearney CJ, Vervoort SJ, Hogg SJ, Ramsbottom KM, Freeman AJ, Lalaoui N, Pijpers L, Michie J, Brown KK, Knight DA, Sutton V, Beavis PA, Voskoboinik I, Darcy PK, Silke J, Trapani JA, Johnstone RW, and Oliaro J 2018. Tumor immune evasion arises through loss of TNF sensitivity. Sci Immunol 3: eaar3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baginska J, Viry E, Berchem G, Poli A, Noman MZ, van Moer K, Medves S, Zimmer J, Oudin A, Niclou SP, Bleackley RC, Goping IS, Chouaib S, and Janji B 2013. Granzyme B degradation by autophagy decreases tumor cell susceptibility to natural killer-mediated lysis under hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 17450–17455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balkwill F 2009. Tumour necrosis factor and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malireddi RKS, Gurung P, Kesavardhana S, Samir P, Burton A, Mummareddy H, Vogel P, Pelletier S, Burgula S, and Kanneganti T-D 2020. Innate immune priming in the absence of TAK1 drives RIPK1 kinase activity–independent pyroptosis, apoptosis, necroptosis, and inflammatory disease. J Exp Med 217: jem.20191644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmiegel WH, Caesar J, Kalthoff H, Greten H, Schreiber HW, and Thiele HG 1988. Antiproliferative effects exerted by recombinant human tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) on human pancreatic tumor cell lines. Pancreas 3: 180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulkarni K, Selesniemi K, and Brown TL 2006. Interferon-gamma sensitizes the human salivary gland cell line, HSG, to tumor necrosis factor-alpha induced activation of dual apoptotic pathways. Apoptosis 11: 2205–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim WH, Lee JW, Gao B, and Jung MH 2005. Synergistic activation of JNK/SAPK induced by TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma: apoptosis of pancreatic beta-cells via the p53 and ROS pathway. Cellular signalling 17: 1516–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimura M, Haisa M, Uetsuka H, Takaoka M, Ohkawa T, Kawashima R, Yamatsuji T, Gunduz M, Kaneda Y, Tanaka N, and Naomoto Y 2003. TNF combined with IFN-alpha accelerates NF-kappaB-mediated apoptosis through enhancement of Fas expression in colon cancer cells. Cell Death Differ 10: 718–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hibbs JB Jr., Taintor RR, and Vavrin Z 1987. Macrophage cytotoxicity: role for L-arginine deiminase and imino nitrogen oxidation to nitrite. Science 235: 473–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamasaki T, Akiyama Y, Fukuda M, Kimura Y, Moritake K, Kikuchi H, Ljunggren HG, Kärre K, and Klein G 1996. Natural resistance against tumors grafted into the brain in association with histocompatibility-class-I-antigen expression. Int J Cancer 67: 365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang B, Karrison T, Rowley DA, and Schreiber H 2008. IFN-gamma- and TNF-dependent bystander eradication of antigen-loss variants in established mouse cancers. J Clin Invest 118: 1398–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kesavardhana S, Malireddi RKS, and Kanneganti TD 2020. Caspases in Cell Death, Inflammation, and Pyroptosis. Annu Rev Immunol 38: 567–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boise LH, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Postema CE, Ding L, Lindsten T, Turka LA, Mao X, Nunez G, and Thompson CB 1993. bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell 74: 597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evan G, and Littlewood T 1998. A matter of life and cell death. Science 281: 1317–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hockenbery D, Nunez G, Milliman C, Schreiber RD, and Korsmeyer SJ 1990. Bcl-2 is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein that blocks programmed cell death. Nature 348: 334–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Najafi M, Ahmadi A, and Mortezaee K 2019. Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling as a target for cancer therapy: an updated review. Cell Biol Int 43: 1206–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strasser A, Harris AW, Bath ML, and Cory S 1990. Novel primitive lymphoid tumours induced in transgenic mice by cooperation between myc and bcl-2. Nature 348: 331–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsujimoto Y, Finger LR, Yunis J, Nowell PC, and Croce CM 1984. Cloning of the chromosome breakpoint of neoplastic B cells with the t(14;18) chromosome translocation. Science 226: 1097–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delbridge AR, Valente LJ, and Strasser A 2012. The role of the apoptotic machinery in tumor suppression. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4: a008789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chefetz I, Grimley E, Yang K, Hong L, Vinogradova EV, Suciu R, Kovalenko I, Karnak D, Morgan CA, Chtcherbinine M, Buchman C, Huddle B, Barraza S, Morgan M, Bernstein KA, Yoon E, Lombard DB, Bild A, Mehta G, Romero I, Chiang CY, Landen C, Cravatt B, Hurley TD, Larsen SD, and Buckanovich RJ 2019. A Pan-ALDH1A Inhibitor Induces Necroptosis in Ovarian Cancer Stem-like Cells. Cell Rep 26: 3061–3075 e3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fu Z, Deng B, Liao Y, Shan L, Yin F, Wang Z, Zeng H, Zuo D, Hua Y, and Cai Z 2013. The anti-tumor effect of shikonin on osteosarcoma by inducing RIP1 and RIP3 dependent necroptosis. BMC Cancer 13: 580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovacs SB, and Miao EA 2017. Gasdermins: Effectors of Pyroptosis. Trends Cell Biol 27: 673–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lage H, Helmbach H, Grottke C, Dietel M, and Schadendorf D 2001. DFNA5 (ICERE-1) contributes to acquired etoposide resistance in melanoma cells. FEBS Lett 494: 54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagarajan K, Soundarapandian K, Thorne RF, Li D, and Li D 2019. Activation of Pyroptotic Cell Death Pathways in Cancer: An Alternative Therapeutic Approach. Transl Oncol 12: 925–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Gao W, Shi X, Ding J, Liu W, He H, Wang K, and Shao F 2017. Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through caspase-3 cleavage of a gasdermin. Nature 547: 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kayagaki N, Stowe IB, Lee BL, O’Rourke K, Anderson K, Warming S, Cuellar T, Haley B, Roose-Girma M, Phung QT, Liu PS, Lill JR, Li H, Wu J, Kummerfeld S, Zhang J, Lee WP, Snipas SJ, Salvesen GS, Morris LX, Fitzgerald L, Zhang Y, Bertram EM, Goodnow CC, and Dixit VM 2015. Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature 526: 666–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orning P, Weng D, Starheim K, Ratner D, Best Z, Lee B, Brooks A, Xia S, Wu H, Kelliher MA, Berger SB, Gough PJ, Bertin J, Proulx MM, Goguen JD, Kayagaki N, Fitzgerald KA, and Lien E 2018. Pathogen blockade of TAK1 triggers caspase-8–dependent cleavage of gasdermin D and cell death. Science 362: 1064–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou Z, He H, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Su Y, Wang Y, Li D, Liu W, Zhang Y, Shen L, Han W, Shen L, Ding J, and Shao F 2020. Granzyme A from cytotoxic lymphocytes cleaves GSDMB to trigger pyroptosis in target cells. Science 368: eaaz7548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elmore S 2007. Apoptosis: A Review of Programmed Cell Death. Toxicologic Pathology 35: 495–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.James Peter, Joanne Isabelle, Zhang J-G, Alvarez-Diaz S, Lewis R, Lalaoui N, Metcalf D, Andrew Samuel, Leila Gillian, Esme Ian, Okamoto T, Renwick Douglas, Jeffrey Nicos, Strasser A, Silke J, and Warren. 2013. The Pseudokinase MLKL Mediates Necroptosis via a Molecular Switch Mechanism. Immunity 39: 443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olsson M, and Zhivotovsky B 2011. Caspases and cancer. Cell Death Differ 18: 1441–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karki R, Sharma BR, Tuladhar S, Williams EP, Zalduondo L, Samir P, Zheng M, Sundaram B, Banoth B, Malireddi RKS, Schreiner P, Neale G, Vogel P, Webby R, Jonsson CB, and Kanneganti T-D 2021. Synergism of TNF-α and IFN-γ triggers inflammatory cell death, tissue damage, and mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infection and cytokine shock syndromes. Cell 184: 149–168.e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fritsch M, Günther SD, Schwarzer R, Albert MC, Schorn F, Werthenbach JP, Schiffmann LM, Stair N, Stocks H, Seeger JM, Lamkanfi M, Krönke M, Pasparakis M, and Kashkar H 2019. Caspase-8 is the molecular switch for apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis. Nature 575: 683–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD, Van Damme P, Vanden Berghe T, Vanoverberghe I, Vandekerckhove J, Vandenabeele P, Gevaert K, and Nunez G 2008. Targeted peptidecentric proteomics reveals caspase-7 as a substrate of the caspase-1 inflammasomes. Mol Cell Proteomics 7: 2350–2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malireddi RK, Ippagunta S, Lamkanfi M, and Kanneganti TD 2010. Cutting edge: proteolytic inactivation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 by the Nlrp3 and Nlrc4 inflammasomes. J Immunol 185: 3127–3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gurung P, Anand PK, Malireddi RK, Vande Walle L, Van Opdenbosch N, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Green DR, Lamkanfi M, and Kanneganti TD 2014. FADD and caspase-8 mediate priming and activation of the canonical and noncanonical Nlrp3 inflammasomes. J Immunol 192: 1835–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malireddi RKS, Gurung P, Mavuluri J, Dasari TK, Klco JM, Chi H, and Kanneganti TD 2018. TAK1 restricts spontaneous NLRP3 activation and cell death to control myeloid proliferation. J Exp Med 215: 1023–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng M, Williams EP, Malireddi RKS, Karki R, Banoth B, Burton A, Webby R, Channappanavar R, Jonsson CB, and Kanneganti T-D 2020. Impaired NLRP3 inflammasome activation/pyroptosis leads to robust inflammatory cell death via caspase-8/RIPK3 during coronavirus infection. J Biol Chem 295:14040–14052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuriakose T, Man SM, Subbarao Malireddi RK, Karki R, Kesavardhana S, Place DE, Neale G, Vogel P, and Kanneganti T-D 2016. ZBP1/DAI is an innate sensor of influenza virus triggering the NLRP3 inflammasome and programmed cell death pathways. Science Immunology 1: aag2045–aag2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kesavardhana S, Malireddi RKS, Burton AR, Porter SN, Vogel P, Pruett-Miller SM, and Kanneganti T-D 2020. The Zα2 domain of ZBP1 is a molecular switch regulating influenza-induced PANoptosis and perinatal lethality during development. J Biol Chem 295: 8325–8330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng M, Karki R, Vogel P, and Kanneganti T-D 2020. Caspase-6 Is a Key Regulator of Innate Immunity, Inflammasome Activation, and Host Defense. Cell 181: 674–687.e613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Christgen S, Zheng M, Kesavardhana S, Karki R, Malireddi RKS, Banoth B, Place DE, Briard B, Sharma BR, Tuladhar S, Samir P, Burton A, and Kanneganti T-D 2020. Identification of the PANoptosome: A Molecular Platform Triggering Pyroptosis, Apoptosis, and Necroptosis (PANoptosis). Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 10: 237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Banoth B, Tuladhar S, Karki R, Sharma BR, Briard B, Kesavardhana S, Burton A, and Kanneganti T-D 2020. ZBP1 promotes fungi-induced inflammasome activation and pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis (PANoptosis). J Biol Chem 295: 18276–18283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lukens JR, Gurung P, Vogel P, Johnson GR, Carter RA, McGoldrick DJ, Bandi SR, Calabrese CR, Walle LV, Lamkanfi M, and Kanneganti T-D 2014. Dietary modulation of the microbiome affects autoinflammatory disease. Nature 516: 246–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gurung P, Burton A, and Kanneganti T-D 2016. NLRP3 inflammasome plays a redundant role with caspase 8 to promote IL-1β–mediated osteomyelitis. 113: 4452–4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karki R, Sharma BR, Lee E, Banoth B, Malireddi RKS, Samir P, Tuladhar S, Mummareddy H, Burton AR, Vogel P, and Kanneganti T-D 2020. Interferon regulatory factor 1 regulates PANoptosis to prevent colorectal cancer. JCI insight 5: e136720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malireddi RKS, Kesavardhana S, Karki R, Kancharana B, Burton AR, and Kanneganti TD 2020. RIPK1 Distinctly Regulates Yersinia-Induced Inflammatory Cell Death, PANoptosis. Immunohorizons 4: 789–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Uhlen M, Zhang C, Lee S, Sjostedt E, Fagerberg L, Bidkhori G, Benfeitas R, Arif M, Liu Z, Edfors F, Sanli K, von Feilitzen K, Oksvold P, Lundberg E, Hober S, Nilsson P, Mattsson J, Schwenk JM, Brunnstrom H, Glimelius B, Sjoblom T, Edqvist PH, Djureinovic D, Micke P, Lindskog C, Mardinoglu A, and Ponten F 2017. A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Science 357: eaan2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grossman RL, Heath AP, Ferretti V, Varmus HE, Lowy DR, Kibbe WA, and Staudt LM 2016. Toward a Shared Vision for Cancer Genomic Data. N Engl J Med 375: 1109–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tweedell RE, Malireddi RKS, and Kanneganti TD 2020. A comprehensive guide to studying inflammasome activation and cell death. Nature protocols 15: 3284–3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karki R, and Kanneganti TD 2019. Diverging inflammasome signals in tumorigenesis and potential targeting. Nat Rev Cancer 19: 197–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, and Karin M 2010. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140: 883–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Landskron G, De la Fuente M, Thuwajit P, Thuwajit C, and Hermoso MA 2014. Chronic inflammation and cytokines in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunol Res 2014: 149185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rogers C, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Mayes L, Alnemri D, Cingolani G, and Alnemri ES 2017. Cleavage of DFNA5 by caspase-3 during apoptosis mediates progression to secondary necrotic/pyroptotic cell death. Nat Commun 8: 14128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Berraondo P, Sanmamed MF, Ochoa MC, Etxeberria I, Aznar MA, Perez-Gracia JL, Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Ponz-Sarvise M, Castanon E, and Melero I 2019. Cytokines in clinical cancer immunotherapy. Br J Cancer 120: 6–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kaplanov I, Carmi Y, Kornetsky R, Shemesh A, Shurin GV, Shurin MR, Dinarello CA, Voronov E, and Apte RN 2019. Blocking IL-1beta reverses the immunosuppression in mouse breast cancer and synergizes with anti-PD-1 for tumor abrogation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116: 1361–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Solal-Celigny P, Lepage E, Brousse N, Reyes F, Haioun C, Leporrier M, Peuchmaur M, Bosly A, Parlier Y, Brice P, Coiffier B, and Gisselbrecht C 1993. Recombinant interferon alfa-2b combined with a regimen containing doxorubicin in patients with advanced follicular lymphoma. Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. N Engl J Med 329: 1608–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wong CC, Baum J, Silvestro A, Beste MT, Bharani-Dharan B, Xu S, Wang YA, Wang X, Prescott MF, Krajkovich L, Dugan M, Ridker PM, Martin AM, and Svensson EC 2020. Inhibition of IL-1beta by canakinumab may be effective against diverse molecular subtypes of lung cancer: an exploratory analysis of the CANTOS trial. Cancer Res 80: 5597–5605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lalaoui N, Merino D, Giner G, Vaillant F, Chau D, Liu L, Kratina T, Pal B, Whittle JR, Etemadi N, Berthelet J, Grasel J, Hall C, Ritchie ME, Ernst M, Smyth GK, Vaux DL, Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ, and Silke J 2020. Targeting triple-negative breast cancers with the Smac-mimetic birinapant. Cell Death Differ 27: 2768–2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dighe AS, Richards E, Old LJ, and Schreiber RD 1994. Enhanced in vivo growth and resistance to rejection of tumor cells expressing dominant negative IFN gamma receptors. Immunity 1: 447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaplan DH, Shankaran V, Dighe AS, Stockert E, Aguet M, Old LJ, and Schreiber RD 1998. Demonstration of an interferon gamma-dependent tumor surveillance system in immunocompetent mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95: 7556–7561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee S, and Margolin K 2011. Cytokines in cancer immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 3: 3856–3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van Horssen R, Ten Hagen TL, and Eggermont AM 2006. TNF-alpha in cancer treatment: molecular insights, antitumor effects, and clinical utility. Oncologist 11: 397–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Farajzadeh Valilou S, Keshavarz-Fathi M, Silvestris N, Argentiero A, and Rezaei N 2018. The role of inflammatory cytokines and tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) in microenvironment of pancreatic cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 39: 46–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ling J, Kang Y, Zhao R, Xia Q, Lee DF, Chang Z, Li J, Peng B, Fleming JB, Wang H, Liu J, Lemischka IR, Hung MC, and Chiao PJ 2012. KrasG12D-induced IKK2/beta/NF-kappaB activation by IL-1alpha and p62 feedforward loops is required for development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 21: 105–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lu T, Tian L, Han Y, Vogelbaum M, and Stark GR 2007. Dose-dependent cross-talk between the transforming growth factor-beta and interleukin-1 signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 4365–4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shchors K, Shchors E, Rostker F, Lawlor ER, Brown-Swigart L, and Evan GI 2006. The Myc-dependent angiogenic switch in tumors is mediated by interleukin 1beta. Genes Dev 20: 2527–2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bromberg JF, Wrzeszczynska MH, Devgan G, Zhao Y, Pestell RG, Albanese C, and Darnell JE Jr. 1999. Stat3 as an oncogene. Cell 98: 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chung YC, and Chang YF 2003. Serum interleukin-6 levels reflect the disease status of colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 83: 222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mantovani A, Barajon I, and Garlanda C 2018. IL-1 and IL-1 regulatory pathways in cancer progression and therapy. Immunol Rev 281: 57–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Trikha M, Corringham R, Klein B, and Rossi JF 2003. Targeted anti-interleukin-6 monoclonal antibody therapy for cancer: a review of the rationale and clinical evidence. Clin Cancer Res 9: 4653–4665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shalapour S, and Karin M 2015. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer: an eternal fight between good and evil. J Clin Invest 125: 3347–3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gleave ME, Elhilali M, Fradet Y, Davis I, Venner P, Saad F, Klotz LH, Moore MJ, Paton V, and Bajamonde A 1998. Interferon gamma-1b compared with placebo in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. Canadian Urologic Oncology Group. N Engl J Med 338: 1265–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kurzrock R, Talpaz M, Kantarjian H, Walters R, Saks S, Trujillo JM, and Gutterman JU 1987. Therapy of chronic myelogenous leukemia with recombinant interferon-gamma. Blood 70: 943–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roberts NJ, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr., and Holdhoff M 2011. Systemic use of tumor necrosis factor alpha as an anticancer agent. Oncotarget 2: 739–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schiller JH, Pugh M, Kirkwood JM, Karp D, Larson M, and Borden E 1996. Eastern cooperative group trial of interferon gamma in metastatic melanoma: an innovative study design. Clin Cancer Res 2: 29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wiesenfeld M, O’Connell MJ, Wieand HS, Gonchoroff NJ, Donohue JH, Fitzgibbons RJ Jr., Krook JE, Mailliard JA, Gerstner JB, and Pazdur R 1995. Controlled clinical trial of interferon-gamma as postoperative surgical adjuvant therapy for colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 13: 2324–2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Erkes DA, Cai W, Sanchez IM, Purwin TJ, Rogers C, Field CO, Berger AC, Hartsough EJ, Rodeck U, Alnemri ES, and Aplin AE 2020. Mutant BRAF and MEK Inhibitors Regulate the Tumor Immune Microenvironment via Pyroptosis. Cancer Discov 10: 254–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Warren S, Adjemian S, Agostinis P, Martinez AB, Chan TA, Coukos G, Demaria S, Deutsch E, Draganov D, Edelson RL, Formenti SC, Fucikova J, Gabriele L, Gaipl US, Gameiro SR, Garg AD, Golden E, Han J, Harrington KJ, Hemminki A, Hodge JW, Hossain DMS, Illidge T, Karin M, Kaufman HL, Kepp O, Kroemer G, Lasarte JJ, Loi S, Lotze MT, Manic G, Merghoub T, Melcher AA, Mossman KL, Prosper F, Rekdal O, Rescigno M, Riganti C, Sistigu A, Smyth MJ, Spisek R, Stagg J, Strauss BE, Tang D, Tatsuno K, van Gool SW, Vandenabeele P, Yamazaki T, Zamarin D, Zitvogel L, Cesano A, and Marincola FM 2020. Consensus guidelines for the definition, detection and interpretation of immunogenic cell death. J Immunother Cancer 8: e000337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Petroni G, Buque A, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G, and Galluzzi L 2020. Immunomodulation by targeted anticancer agents. Cancer Cell 39: 310–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang Q, Wang Y, Ding J, Wang C, Zhou X, Gao W, Huang H, Shao F, and Liu Z 2020. A bioorthogonal system reveals antitumour immune function of pyroptosis. Nature 579: 421–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yatim N, Jusforgues-Saklani H, Orozco S, Schulz O, Barreira da Silva R, Reis e Sousa C, Green DR, Oberst A, and Albert ML 2015. RIPK1 and NF-kappaB signaling in dying cells determines cross-priming of CD8(+) T cells. Science 350: 328–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vredevoogd DW, Kuilman T, Ligtenberg MA, Boshuizen J, Stecker KE, de Bruijn B, Krijgsman O, Huang X, Kenski JCN, Lacroix R, Mezzadra R, Gomez-Eerland R, Yildiz M, Dagidir I, Apriamashvili G, Zandhuis N, van der Noort V, Visser NL, Blank CU, Altelaar M, Schumacher TN, and Peeper DS 2019. Augmenting Immunotherapy Impact by Lowering Tumor TNF Cytotoxicity Threshold. Cell 178: 585–599 e515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hodge G, Barnawi J, Jurisevic C, Moffat D, Holmes M, Reynolds PN, Jersmann H, and Hodge S 2014. Lung cancer is associated with decreased expression of perforin, granzyme B and interferon (IFN)-gamma by infiltrating lung tissue T cells, natural killer (NK) T-like and NK cells. Clin Exp Immunol 178: 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kalbasi A, and Ribas A 2020. Tumour-intrinsic resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Rev Immunol 20: 25–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figures 1-4