Our Favorite Things (original) (raw)

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! Subscribe today.

As part of our third annual Editors’ Choice Awards, six Outside staffers, from editorial director Alex Heard to assistant editor Kyle Dickman, reflect on some of their favorite things, including the tree porn etched into trunks by bored and lonely sheepherders out west and the lack of native deadly animals on the beautiful island nation of New Zealand.

- Tree Porn

- The (Almost) Total Lack of Scary Creatures in New Zealand

- Redemption

- One-Man Rafts

- Crabbing Off a Dock

- The Second Half of Buried in the Sky

: Tree Porn

Assistant editor Kyle Dickman explores the fantasies of sheepherders

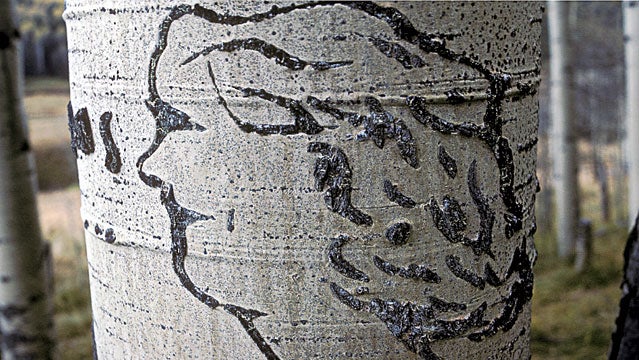

Carvings on aspen trees by lonesome sheepherders near Dolores in the San Juan Mountains of southwestern Colorado. (Scott Warren/Outside Magazine)

Yeah, it’s a little gross that sheepherders out west passed their days pleasuring themselves while gazing at crude images of naked women carved into aspen trees. But it’s not (quite) as perverted as it sounds once you learn the carvings’ provenance. At the end of the 19th century, young Basque men began pouring into the United States and taking the only jobs they could find—watching sheep in the mountains. With months of solitude, they took to etching pictures and notes into tree trunks.

There are thousands of these arborglyphs, as the archaeologists call them, mainly in California and Nevada. Some are letters to lovers left behind. (“I ache for my sweetheart.”) Some are poems. (“I am sadder than a pine forest at dusk.”) And some are truly art, like the Banksy-esque nudes a herder named D. Borel created in Tahoe National Forest. But many are what you might expect from these bored young men: scenes from the brothels of Reno. Their greatest density can be found in Porno Grove One (there are two) in Nevada’s Table Mountain Wilderness, which has a dozen of the X-rated intaglios. Taken together they can be seen as yet more evidence of man’s depravity. But I don’t think of them that way. I prefer the view expressed by a certain Basque song written about a carver: “He believed that he could reflect the loneliness of the mountains.”

: The (Almost) Total Lack of Scary Creatures in New Zealand

Contributing editor Stephanie Pearson writes about a fabulous trip to the island nation

New Zealand is a country devoid of any large predators. (Sam Hurd/Outside Magazine)

Nearly a decade ago, I was offered a dream assignment explaining why New Zealand had become a heaven for adventure travelers. My Kiwi photographer (also dreamy) and I climbed craggy peaks, cannonballed into swimming holes, and paddled the Tasman Sea in kayaks, pursuing a rich diet of seafood and adrenaline. A week into the journey, while camping on South Island, I became aware of a strange, calming absence. What I was missing was fear. At that moment, it occurred to me that New Zealand is utterly devoid of bloodthirsty critters_*_. No hungry bears or toothy cats. No man-eating crocodiles or venomous snakes. Not a single deadly insect. In other words, it’s the complete opposite of neighboring Australia, where the cast of killers is so eclectic it includes a predatory snail with a harpoonlike tooth.

To check my facts, I recently emailed Herb Christophers, of New Zealand’s Department of Conservation. “Here is your list of native deadly animals,” he replied. “Nothing!” But Christophers did mention a few isolated incidents of death by sheep butting and forwarded a 2010 news story about a 22-year-old Canadian man who, while nude sunbathing at a North Island beach, was bitten on his privates by a katipo spider, an endangered, less venomous relative of the black widow. The guy’s member did swell horribly, and he contracted myocarditis, but he lived.1

It makes you wonder: is that famously fearless Kiwi spirit a product of … boredom? Did New Zealanders turn their home into the thrill-seeking center of the universe2 because, when there’s nothing around to kill you, you crave risk? Was Sir Edmund Hillary—a beekeeper, perhaps the most dangerous career in New Zealand!—simply overcompensating?

Maybe. Maybe not. Either way, I can’t wait to go back.3

*OK, there are great white sharks, but they seem to be of less menacing stock. New Zealand has had 13 documented fatal shark attacks in the past 170 years; Australia has had 15 since 2000.

1. Enjoy a North Island beach (with no katipos) at Wharekauhau Country Estate, an iconic Kiwi lodge with three new cottages on 5,500 acres overlooking Palliser Bay just northeast of Wellington. From $531 per person.

2. The highest bungee jump in the country is the 440-foot drop over the Nevis River, near Queenstown ($212). The longest continuous mountain-biking trail is along the 47-mile Queen Charlotte Track, on the South Island, with an elevation gain of 1,300 feet. Expect a 13-hour ride ($6 per night at one of seven Department of Conservation campsites ).

3. Note to my editor: I’d especially like to check out the Southern Alps’ Minaret Station, New Zealand’s first luxury tented heli-lodge (think wall-to-wall sheepskin). Suites, $2,850 per night (minimum stay, two nights).

: Redemption

Senior executive editor Michael Roberts reclaims his youth

It's amazing what a flip can do for your coolness factor. (Marie McClellan/Flickr)

I always wanted to be that boy at the pool who did flips off the diving board. Growing up, the best I could muster was a decent swan dive. Sometimes I’d take a run down the board telling myself I’d go for it, but once in the air I’d freeze up just as I began to rotate, my eyes closed, not knowing what to do next. It was the same on the ski hill: the cool kids were pulling 360s, while I was stuck on the spread eagle. By the time I left home for college, I’d pretty much come to terms with the fact that I just wasn’t that good at flying.

Then, last winter, I saw a chance to try again. House of Air, an indoor trampoline park in San Francisco, was offering an evening class in action-sports aerial maneuvers. Develop your skills on our competition-grade trampolines, the pitch went, and you can take them to the terrain park. At 38, I was the oldest guy in my class by at least a decade. For the first four weeks, we practiced a sequence of drops and rotations designed to build proper form. Just as we began ramping up to a front flip, I got sick (I swear) and missed two critical sessions. When I came back, my classmates had already moved on to the backflip. I tried so hard to catch up that I tweaked my shoulder. Finally, in the very last class, I nailed a couple dozen flips. I couldn’t stop. That night, I giddily emailed a video clip of one to my old grade-school buddies.*

But my real moment of glory came this past summer at the lake house of a family friend. Some kids were bopping around on one of those inflatable floating trampolines. I swam out to them, took a couple of test bounces, and launched a crisp front flip into the water. When I surfaced, this gangly seven-year-old boy was staring at me in silence. I knew exactly what he was thinking.

*Editor’s note: He actually sent this to seemingly everyone in his contacts list.

: One-Man Rafts

Correspondent Christopher Solomon learns that being on a boat really does make fly-fishing better

Rafting while fishing is the best. (Renee V/Flickr)

My first dozen years as a fly-fisherman were spent wearing out the felt soles of wading boots while walking. This was not by choice. But in my simple cosmology, those classy wooden drift boats were for rich people. The rest of us had to hoof it. Last year, however, I gave in to a friend’s badgering and bought an old Water Master Grizzly raft on eBay. Now I’m a riverman.

The Griz looks like an inner tube mated with a whitewater raft—an oblong donut of PVC fabric, battleship gray, with a seat on one half and no floor on the other, so flippered feet can drop and steer when desired or stand in the shallows and cast. An absurdly ambitious racing stripe marks the waterline. When you float past wading fishermen while wearing this drab rubber ducky, you feel the momentary stab of dignity lost; it’s the moped of the river.

But oh, the places we go! Thanks to the Griz, my favorite freestone river, the Methow in northern Washington, is a new world. I’ve now visited stretches I’d never before seen and pulled hungry trout from handsome, hidden holes. The few times I’ve been in an actual drift boat, the water unspooled quickly. But when you ride near eye level with the foam line, you feel the river’s every intimate roll. You smell the mud on the shore. You can look through your feet into the deep hole below and see the tail fin of Old Dynamite wave as gently as a flag in a breeze. And at day’s end, you can fit the deflated Griz into the trunk of a Honda Civic, with room to spare. Try that with a drift boat.

: Crabbing Off a Dock

Editorial director Alex Heard reflects on his love for the lazy outdoors

A crab hangs from a net of bacon bits by a pier. (Loop Images/Outside Magazine)

I like outdoor activities that let you fall asleep while doing them, so naturally I’m a fan of crabbing off a dock. I learned the basics from my mother in the summer of 1967, during a family beach vacation in Biloxi, Mississippi. Mama, as I unfailingly addressed her back then, announced one morning that we were going to catch blue crabs off a nearby pier that jutted into the Gulf of Mexico. I was skeptical, but before long she had me and two siblings geared up—collapsible metal basket traps, chicken parts, long pieces of twine to raise and lower the rigs—and hauling them in like crazy. I was nine and trigger-happy, prone to checking the baskets too often. (You have to wait for the crab to say, “Hey, chicken parts!” and skeedle into position.) Following her example, I took it down a notch and settled into a pattern of snoozy vigilance.

After college I lived in Washington, D.C., for several years, so I was able to crab during weekend trips to Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic backwaters of Maryland and Virginia. Once, a friend and I caught a bunch using the demanding handline technique: you attach bait to the end of a line, toss it out, and pull it in real slow until a feeding Jimmy or Sook (waterman lingo for males and females) comes into net range. But that required staying awake, so I drifted back to the old ways—lying on the dock while the traps did their thing, fogged out in that perfect summer blend of sunshine, salt-muck smells, and the sound of tidal water lapping against dock pilings. Oh, and don’t forget the ice-cold beer, which keeps you both hydrated and half asleep. It’s crabbing’s performance-enhancing drug.

: The Second Half of ‘Buried in the Sky’

Senior editor Grayson Schaffer reviews a book about the 2008 accident on K2

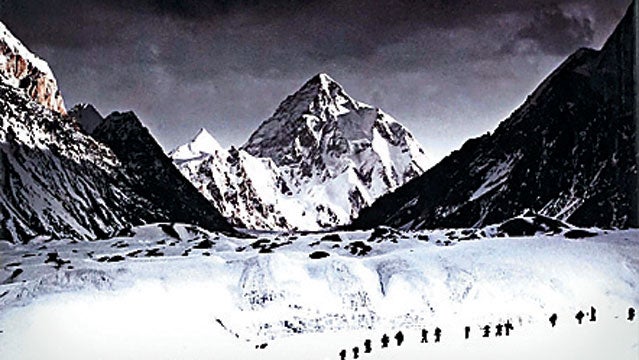

The tale of a 2008 disaster that killed 11 people. (Courtesy of WW Norton & Co)

If you forgive the sluggish first hundred pages, which veer into everything from Buddhist mythology to Nepal’s civil war, Buried in the Sky (W.W. Norton, $27), published last June, is easily the most riveting and important mountaineering book of the past decade.

Its topic—the August 2008 disaster on K2 that killed 11 climbers—has already inspired five books and three films, none of which, we now know, come close to reporting the whole story. Cousins and co-authors Peter Zuckerman, a former newspaperman for the Oregonian, and Amanda Padoan, an ExplorersWeb blogger, take the point of view of Nepalese Sherpas Chhiring Dorje and Pasang Lama and Pakistani high-altitude porter Shaheen Baig for most of the book. But it’s not their perspective so much as their exhaustive reporting and elegant delivery that gives the book its rich texture.

While Western climbers such as “irritable Dutchman” Wilco van Rooijen and American publicity hound Nick Rice squabble “like tweens,” and members of the ill-fated Korean Flying Jump expedition shamble off the summit “like lushes leaving a bar—reveling, swearing, and puking on their boots,” the Sherpas and Pakistanis operate in a parallel world that exists on every expedition-style Himalayan climb but usually goes unseen, even by the mountaineers in camp. Unlike so many climbing yarns, the hired help in Buried in the Sky come off as real and sometimes abused people with aspirations and loved ones anxiously awaiting them at home.