Periodization: What the Data Say (original) (raw)

From the outset, I want to make my intentions clear: I want this to be the most thorough quantitative overview of the periodization literature in existence, while also being readily accessible and understandable. It may get a bit dense and technical at times, but my aim is for anyone to be able to understand it, regardless of academic background, as long as they’re willing to read closely and pay attention.

Periodization is a popular topic of discussion in the strength community. However, 90% of the discussion essentially boils down to “I read an article on (insert random website here) saying that xyz form of periodization is the best,” or “here are two studies that support my view, therefore I’m right,” or “well, in theory, xyz periodization model SHOULD lead to abc outcomes, therefore it’s indisputably the best.” However, there’s a vast body of literature on the subject, with at least 60 studies (that I could find, at least), most of which the majority of people are completely unaware. With this article, I basically want to provide the groundwork for people to discuss this topic well, with an empirical starting point and a beefy list of sources to read and learn from.

If you haven’t read the first installment in this series yet (Periodization: History and Theory), I’d encourage you to check it out before diving in here.

Before we get rolling here, since this article is a doozy, I want to tell you what you should expect from this article, in order:

- Basic definitions, just to ensure everyone’s on the same page.

- Notes about the quantitative analyses I performed.

- The results of the analyses.

- Problems with the current research we have, and how it could be improved upon.

- Practical takeaways.

- Links to sources and further reading.

Definitions

To start with, I need to make sure we’re all on the same page regarding terminology so you’ll know what the heck I’m talking about for the rest of this article.

Periodization

The National Strength and Conditioning Association’s definition of periodization is as follows: “Periodization is a method for employing sequential or phasic alterations in the workload, training focus, and training tasks contained within the microcycle, mesocycle, and annual training plan. The approach depends on the goals established for the specified training period. A periodized training plan that is properly designed provides a framework for appropriately sequencing training so that training tasks, content, and workloads are varied at a multitude of levels in a logical, phasic pattern in order to ensure the development of specific physiological and performance outcomes at predetermined time points.”

The three main pieces of the definition to pull out are: sequential/phasic (training split up into distinct blocks that build on each other), variety (i.e. all of your training isn’t exactly the same), and goal-oriented (attaining peak performance at a specific time point – generally a competition).

Linear Periodization (LP)

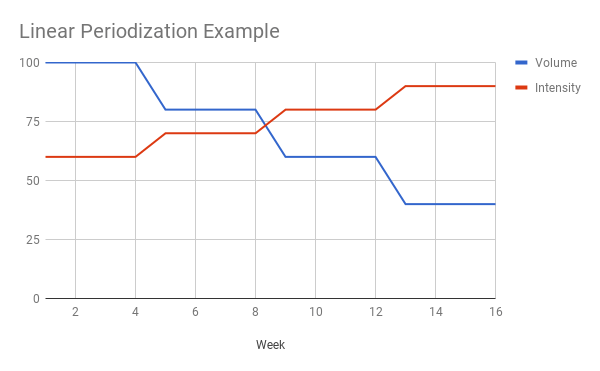

Linear Periodization (often called “traditional periodization”) refers to the system developed by Matveyev and his comrades in the ‘50s and ‘60s in the Soviet Union, whereby training volume progressively decreases over time, and training intensity progressively increases over time, with a taper before a major competition. Importantly, a “training cycle” in this model typically referred to at least an entire year of training (i.e. one world championship until the next world championship) and sometimes four years of training (i.e. one Olympics until the next Olympics).

In more recent times, the definition has shifted to some degree. Now, when most people talk about linear periodization, they’re talking about any training structure in which volume generally decreases and intensity generally increases over time. Unlike the original definition, that could refer to a few months of training, instead of a year of training or more.

Undulating Periodization (UP)

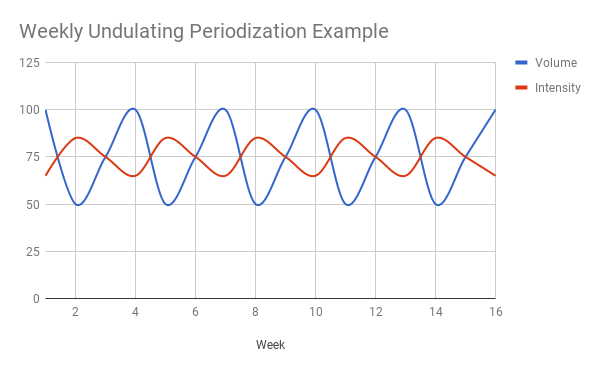

Undulating periodization refers to training structures in which volume and intensity both go up and down repeatedly over time. Undulating periodization didn’t really get introduced as a concept until the definition of linear periodization changed to include shorter time periods. When linear periodization still dealt with yearlong training organization, of course you’d have fluctuations in volume and intensity within that year.

The two major subcategories of undulating periodization are weekly undulating periodization (WUP) and daily undulating periodization (DUP). With weekly undulating periodization, the fluctuations in volume and intensity take place week to week (generally with higher intensities corresponding with lower volumes, and vice versa). For example, if a linear approach had you lifting 70% 1RM on week 1, 75% on week 2, 80% on week 3, and 85% on week 4, a weekly undulating approach may have you lifting 70% on week 1, 80% on week 2, 75% on week 3, and 85% on week 4 (intensity goes up, down, up in this example, instead of just increasing every week).

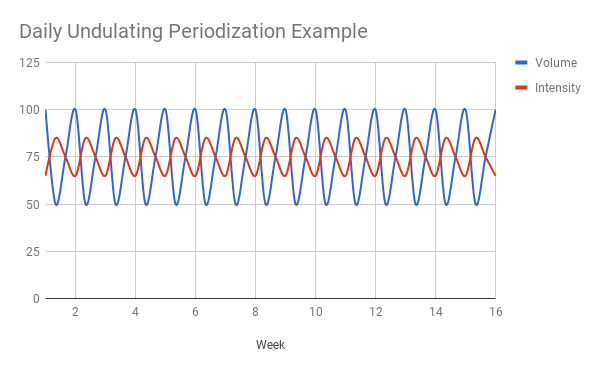

With daily undulating periodization, the fluctuations in volume and intensity take place within a single training week. For example, if your training intensity on week one is supposed to be 75% and you squat twice in that training week, without DUP, you’d use 75% loads for both sessions; with DUP, you may use 70% for one session and 80% for your other session.1There’s an argument to be made that daily and weekly undulating periodization should typically be referred to as daily and weekly undulating programming, since the fluctuations in volume and intensity happen on too short of a time scale for each workout/week to really qualify as its own training phase (or “period” – the root word in _period_ization). For daily undulating periodization, you could just define each workout as its own microcycle, and for weekly undulating periodization, you could just define each week as its own mesocycle, but those delinations can be a bit of a stretch, especially in the case of powerlifting where the fluctuations in intensity and overall training goal generally aren’t that large. However, daily/weekly undulating periodization is the terminology typically used in the literature, so that’s what we’re going with here.

Block Periodization (BP)

Block periodization was originally proposed as a way to make periodization work for sports that had more than one major competition per year (since LP was originally only designed for a single major competition). The original versions of BP had an offseason that looked basically identical to LP, with the addition of a “competitive block,” which consisted of training with just enough volume and intensity to allow for maintenance of performance without over-taxing the athlete during the competitive season.

The definition has shifted a bit more recently, and now BP is generally used to refer to training that starts with a block focused on strength endurance, followed by a block focused on hypertrophy, followed by a block focused on maximal strength, followed by a block focused on power and velocity (followed by a competitive block, if you’re dealing with a team sport athlete).

Now, if you’re reading this and thinking “why are these things defined as separate forms of periodization? They don’t seem mutually exclusive at all,” you’re right. I’ll discuss that issue more later. But basically, for the past 40+ years, prominent periodization theorists (Bondarchuk, Issurin, Matveyev, etc.) have been having public dick-measuring contests about whose model is best (and hence, why other models are inferior), which is largely why people have a tendency to treat them as completely separate concepts. As a result, they’ve been researched as separate concepts.

Notes about analysis

Just to warn you, this section will probably be a slog. If you trust that I didn’t mess anything up too badly, feel free to skip this section. This section is for people who want to know exactly what I did so they can recreate my analyses or understand why I made some of the decisions I did with the analysis.

This project started by running a pubmed search for “periodization” and “periodize,” then mining sources from the extant reviews and meta-analyses on periodization and checking the reference lists of the studies I found. The searched turned up 60 total articles, all of which are in this spreadsheet (if you want a copy, go “file” → “download,” or “make a copy”).

My intention was just to use normal meta-analytic procedures (i.e. calculate effect sizes and use a random effects model). However, I ran into some issues with that approach. Namely, several studies reported standard deviations so small that I simply couldn’t deem them credible, and, as a result, they’d lead to effect sizes so large I couldn’t deem them credible either. For example, if you use the reported data in this study (pre-training bench press 1.28 ± 0.002 times body weight, with increases ranging from 0.13-0.42 times body weight), you’d wind up with within-group effect sizes ranging from 65-160, and between-group effect sizes ranging from 10-95. That’s clearly ludicrous. There were no other issues THAT major, but several other studies had standard deviations small enough (and hence, effect sizes large enough; i.e. 5+) that they made me very skeptical.

As a result, I just used percent changes. Percent changes can be dangerous when used with individual studies since they’re sensitive to pre-training strength differences (giving an advantage to groups that are weaker to begin with), but there were enough studies included in all of these analyses that small pre-training strength differences would just wash out. I also like percent changes for something like this since they’re easier for non-academic readers to understand intuitively. I looked at the data four different ways:

- Just mean percent changes between the two things I was comparing (i.e. periodized vs. nonperiodized, or linear vs. undulating periodization) without any sort of fiddling.

- Percent changes per week. Basically, you expect larger total strength gains in studies that run for a longer period of time, which can make differences between groups appear larger. If one protocol lets people gain strength twice as fast, you may be looking at a 3% vs. 6% strength increase at 6 weeks, but a 6% vs. 12% strength increase at 12 weeks. The difference to total percentage change is twice as large at 12 weeks (6% vs. 3%), but the difference in strength gains per week is the same (0.5% per week vs. 1% per week).

- Mean percent changes, when pooling together all of the exercises within a single study. This essentially makes sure one study can’t overpower the rest. For example, if one study just tested the squat, it would have one data point in the analysis. If another study tested squat, bench, leg press, and shoulder press, it would have four data points in the analysis. You could argue that all those effects should be included independently to pick up on differences between exercises within a single study, or you could argue that you should pool within each study, since each study is essentially just testing one training program against another, so why let one comparison matter four times as much in your analysis? In a similar vein, I also pooled the effects of different groups within a single study in this step. For example, if I was doing a comparison of periodized and nonperiodized training, and one study had a nonperiodized group, an LP group, and a DUP group, I’d pool the effects seen in the LP and DUP groups here.

- Mean (pooled) percent changes per week.

Personally, I think the second and the fourth options give the best comparison (the graphs you’ll see below will use option 4 when pooling trained and untrained lifters, and option 2 for everything else). However, if any of the manipulations I described seem inappropriate or unnecessary to you, I can understand that as well. In general, none of the analyses led to meaningfully different outcomes (I report when they did). For reporting results, I just used the average of the four analyses; confidence intervals are the lowest bottom end to the highest upper end (just to be purposefully conservative with the CIs).

One last thing I did for comparisons is weighting means by the number of subjects in the study. For example, if a study had 30 participants per group, its results would count 3x as much as a study with just 10 participants per group. This ended up not actually changing much of anything, for what it’s worth (which is good – if you have big studies coming to dramatically different conclusions than small studies, you have a problem).

There were six main comparisons: periodized vs. nonperiodized training for 1) all participants, 2) trained participants, and 3) untrained participants and linear vs. undulating periodization for 4) all participants, 5) trained participants, and 6) untrained participants. Significance tests are all two-tailed paired samples t-tests, and effect sizes are all Cohen’s d (note: these are effect sizes between conditions once I’d run my analyses, not effect sizes for each study to be pooled for the analysis).

I also looked to see whether periodization or periodization style had larger effects on squat or bench press (same sort of analysis as described above), and whether there was any evidence that periodization or a particular periodization style became more effective over time. I did this by plotting differences between groups (dependent variable) and study lengths (independent variable), and seeing if the differences between groups for a given comparison tended to increase or decrease with study length, using simple linear regression.

A couple final points:

- Since this isn’t a formal meta-analysis, I had a little more leeway to decide what studies and groups to include or exclude when running analyses. Generally, I just went with studies using young, healthy people (so a couple of studies in the elderly were excluded), and included groups that were at least roughly matched for volume and intensity. If this was a formal meta-analysis and I included “matched for volume and intensity” as a criteria, I’d have to exclude several studies that matched volume and intensity pretty closely, but not perfectly; if I didn’t include that as a criterion, I’d need to include studies like this that compared light, low-volume nonperiodized training against heavier, higher-volume periodized training. Of note, I decided which studies to include and exclude before running any analyses.

- I only included studies that used dynamic, isotonic exercises (i.e. squat, bench press, leg press, shoulder press, etc.) since, I assume, most of us are interested in how periodization affects strength gains for dynamic, isotonic exercises. This means I excluded a couple of studies that tested strength on a dynamometer or used isometric strength tests.

- If you don’t like the studies I chose to analyze or exclude, or the way I analyzed things, feel free to use my spreadsheet to do things differently! I already did a lot of the work for you, and I certainly wouldn’t claim that the way I analyzed things is the only way to go about it (or that I exhausted all the questions you could ask in this data set).

- If you have any questions about exactly how I did things with my analysis, feel free to ask. I’m trying to keep this section brief, as I realize 98% of people reading this article don’t care about this section one iota. I like to nerd out about the details, though.

Results

The studies included for review are in the table below. Studies were excluded for several possible reasons, including participants’ characteristics (i.e. elderly or children), how strength was assessed (isometric or isokinetic), or details of the training programs used (i.e. block and reverse linear periodization didn’t have enough studies to make meaningful quantitative comparisons).

| Author (year) | Training status | Periodized vs. Nonperiodized? | Linear vs. Undulating? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadizad (2014) | Untrained | Yes | Yes |

| Apel (2011) | Trained | No | Yes |

| Baker (1994) | Trained | Yes | Yes |

| Buford (2007) | Untrained | No | Yes |

| de Lima (2012) | Untrained | No | Yes |

| Eifler (2016) | Trained | Yes | Yes |

| Harris (2000) | Trained | Yes | No |

| Hartmann (2009) | Trained | No | Yes |

| Herrick (1996) | Untrained | Yes | No |

| Hoffman (2009) | Trained | Yes | Yes |

| Hoffman (2003) | Trained | Yes | No |

| Kok (2009) | Untrained | No | Yes |

| Kraemer (2003) | Untrained | Yes | No |

| Kramer (1997) | Trained | Yes | No |

| Miranda (2011) | Trained | No | Yes |

| Monteiro (2009) | Trained | Yes | Yes |

| Moraes (2013) | Untrained | Yes | No |

| O’Bryant (1988) | Untrained | Yes | No |

| Peterson (2008) | Trained | No | Yes |

| Prestes (2009) | Trained | No | Yes |

| Rhea (2003) | Trained | No | Yes |

| Schiotz (1998) | Untrained | Yes | No |

| Schoenfeld (2016) | Trained | No | Yes |

| Simão (2012) | Untrained | No | Yes |

| Souza (2014) | Untrained | Yes | Yes |

| Stone (2000) | Trained | Yes | No |

| Willoughby (1993) | Trained | Yes | No |

Periodized vs. Nonperiodized Overall

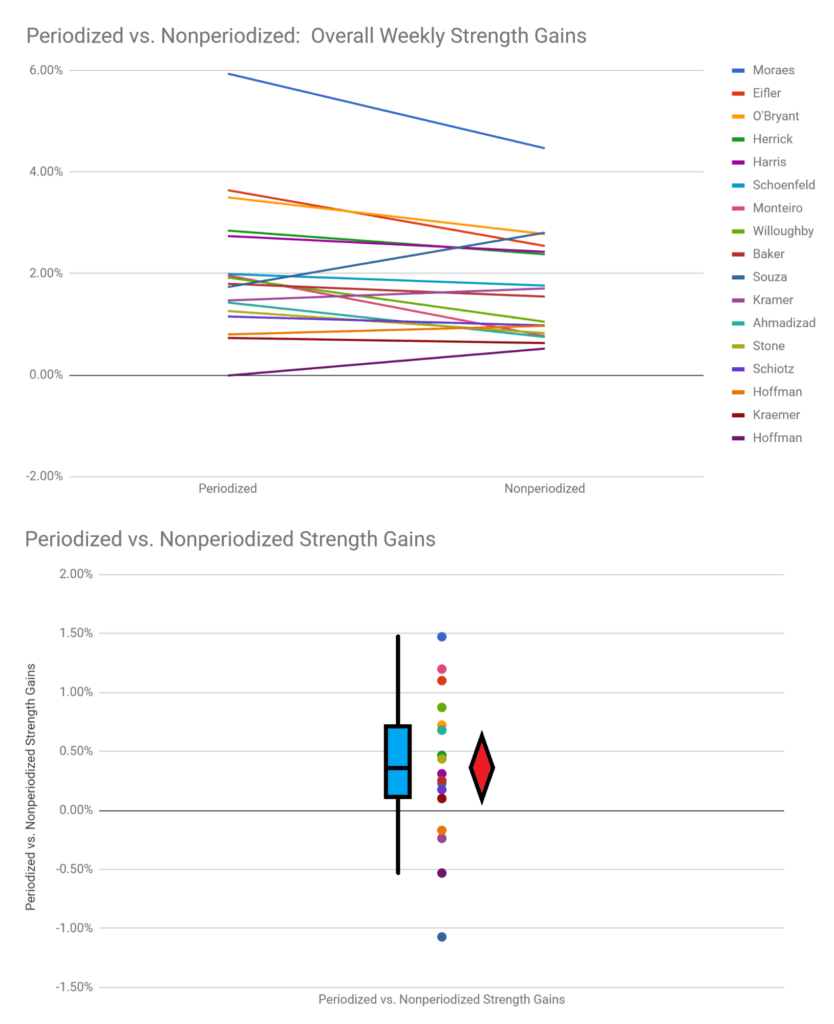

Depending on how the data were analyzed, periodized training led to average strength gains of 21.78-23.62%, with average weekly strength gains of 1.96-2.05%. Nonperiodized training, on the other hand, led to average strength gains of 18.90-19.10%, with average weekly strength gains of 1.59-1.70%. These were significant differences in all analyses (p<0.05), and the associated effect sizes were all between 0.23-0.30 (classified as small effects). On average, periodized groups gained strength about 22% faster (95% CI for all analyses: 2.80-39.26%).

Note about these graphs: The top graph shows results from a single study. A line sloping down means faster gains with periodized training, while a line sloping up means faster gains with nonperiodized training. The bottom graph shows, from left to right, a box plot, the difference in results in each study (in this case, periodized minus nonperiodized, so a positive number means faster gains for periodized), and a 95% CI for the difference.

Linear vs. Undulating Periodization Overall

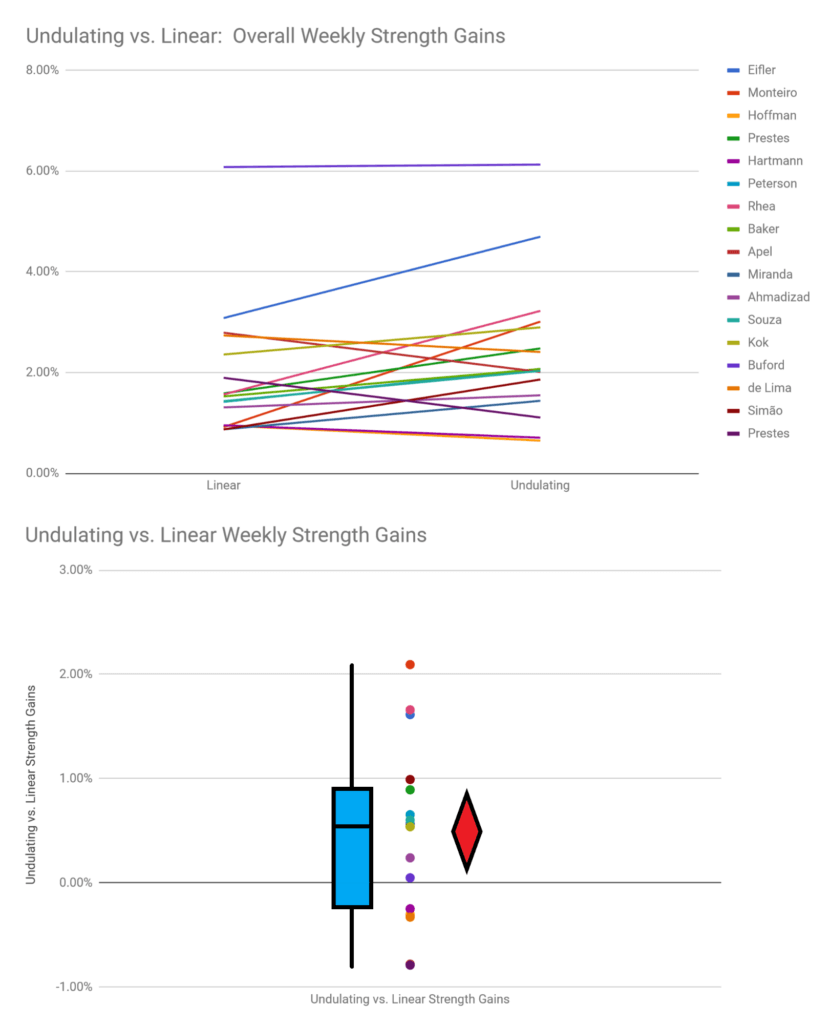

Depending on how the data were analyzed, undulating periodization led to average strength gains of 24.75-27.44%, with average weekly strength gains of 2.37-2.59%. Linear periodization, on the other hand, led to average strength gains of 20.33-21.65%, with average weekly strength gains of 1.90-1.96%. These were significant differences (p<0.05) in all but one analysis (pooled, non-weekly; p=0.08), and the associated effect sizes were all between 0.21-0.37 (classified as small effects). On average, undulating groups gained strength about 17% faster (95% CI for all analyses: -0.88-36.60%).

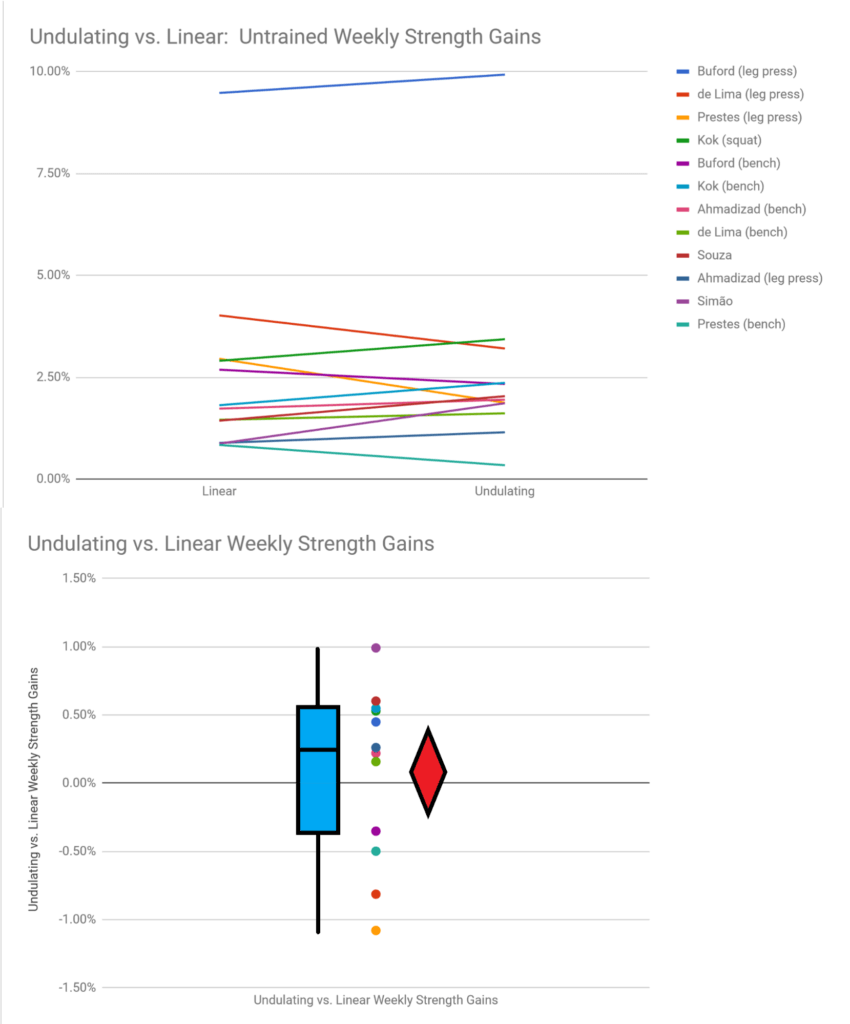

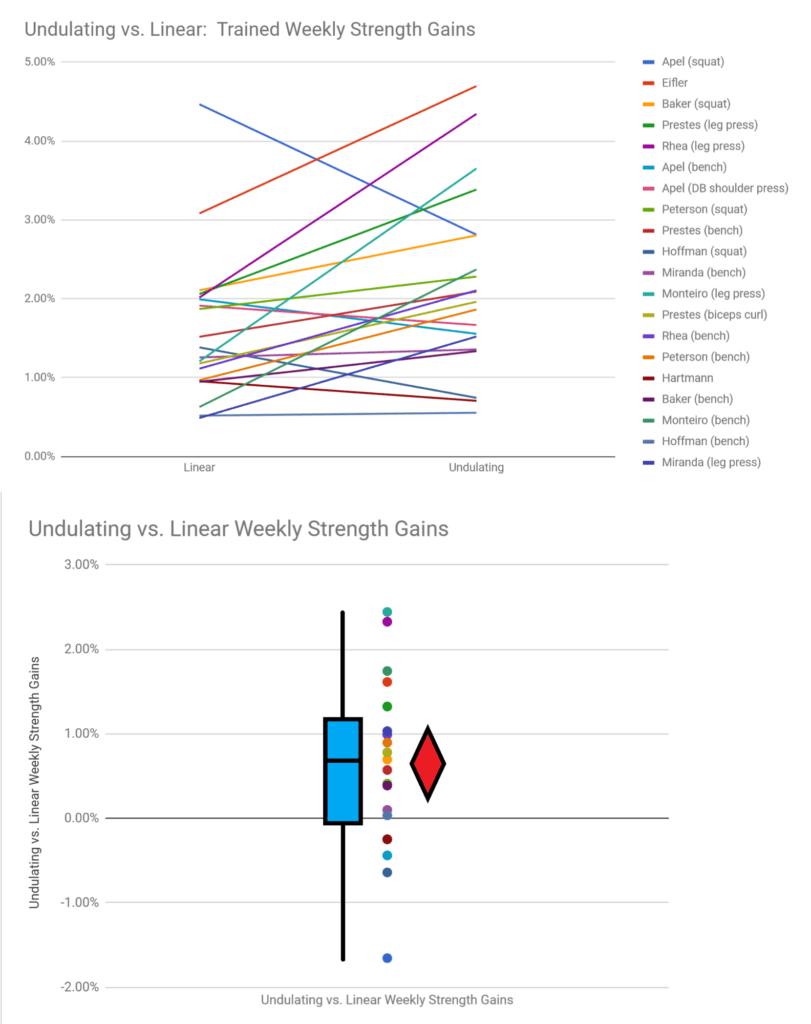

Values above zero mean faster gains for undulating

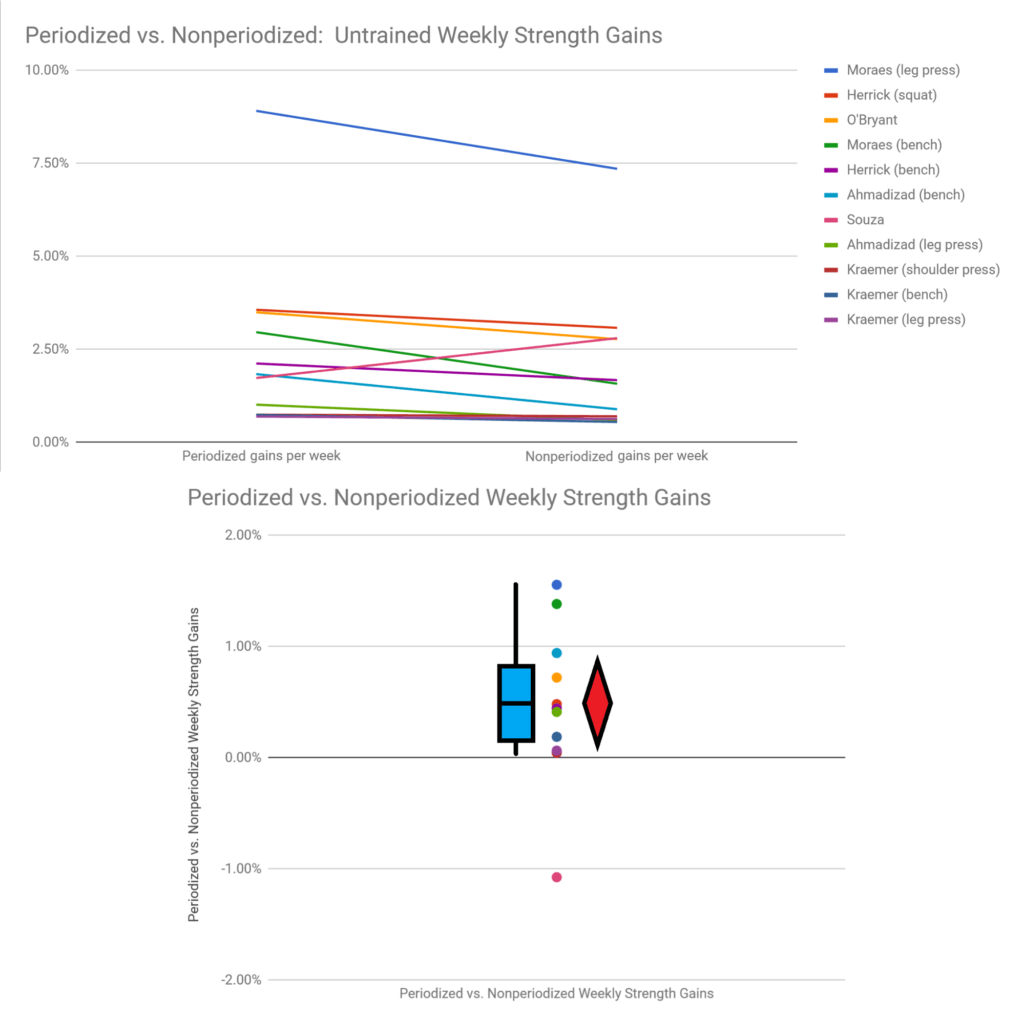

Periodized vs. Nonperiodized Untrained

Depending on how the data were analyzed, periodized training led to average strength gains of 32.85-33.62%, with average weekly strength gains of 2.53-2.70%. Nonperiodized training, on the other hand, led to average strength gains of 27.13-27.14%, with average weekly strength gains of 2.06-2.30%. These were significant differences in total and weekly strength gains before pooling to account for multiple effects within studies (p<0.05), but not after pooling (p=0.06-0.15). The associated effect sizes were all between 0.23-0.30 (classified as small effects). On average, periodized groups gained strength about 17.5% faster (95% CI for all analyses: -10.51-39.78%).

Values above zero mean faster gains for periodized

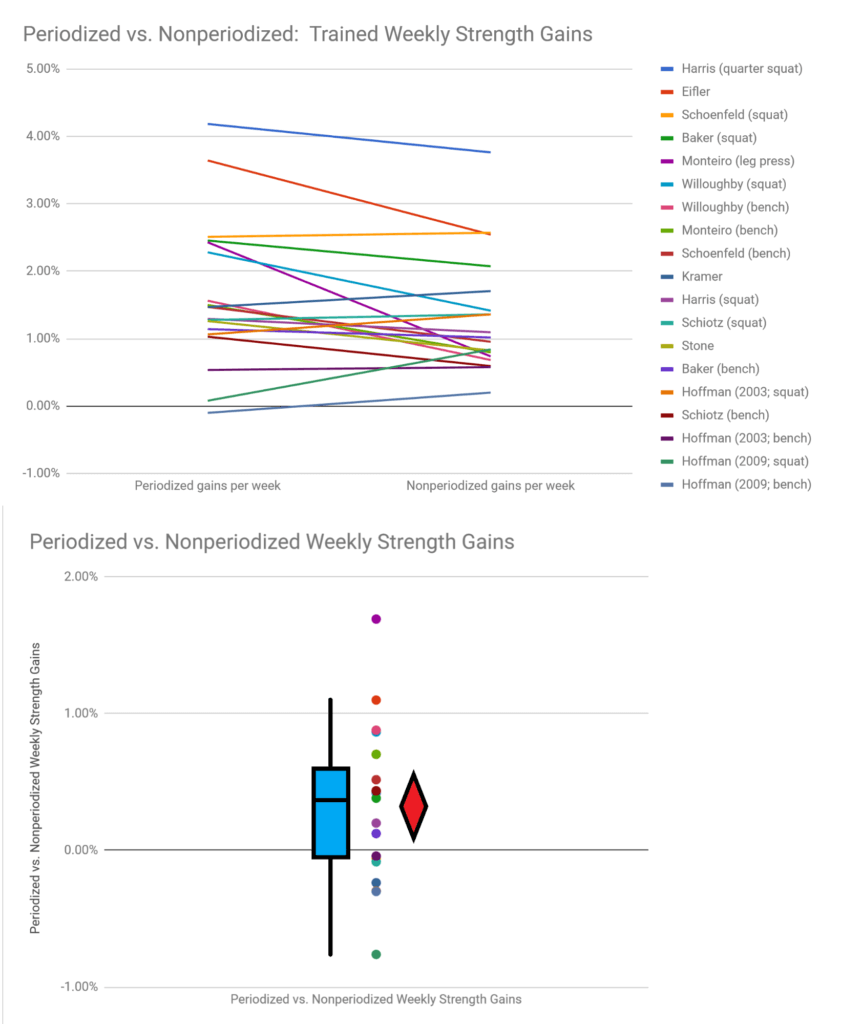

Periodized vs. Nonperiodized Trained

Depending on how the data were analyzed, periodized training led to average strength gains of 17.83-18.28%, with average weekly strength gains of 1.64-1.70%. Nonperiodized training, on the other hand, led to average strength gains of 14.36-14.71%, with average weekly strength gains of 1.32-1.37%. These were significant differences (p<0.05) in all but one analysis (pooled, non-weekly; p=0.12), and the associated effect sizes were all between 0.31-0.47 (classified as small effects). On average, periodized groups gained strength about 23.5% faster (95% CI for all analyses: -3.42-49.28%).

Linear vs. Undulating Untrained

Depending on the analysis, the training in these studies led to strength gains of 25.09-27.70%, with average weekly strength gains of 2.38-2.67%. None of the analyses revealed any differences that were remotely close to significant, and all effect sizes were trivial (d<0.12).

Linear vs. Undulating Trained

Depending on how the data were analyzed, undulating periodization led to average strength gains of 23.72-24.51%, with average weekly strength gains of 2.19-2.24%. Linear periodization, on the other hand, led to average strength gains of 16.99-18.02%, with average weekly strength gains of 1.57-1.58%. These were significant differences in all analyses (p<0.05), and the associated effect sizes were all between 0.56-0.76 (classified as medium effects). On average, groups employing undulating periodization gained strength about 28% faster (95% CI for all analyses: 0.47-56.29%).

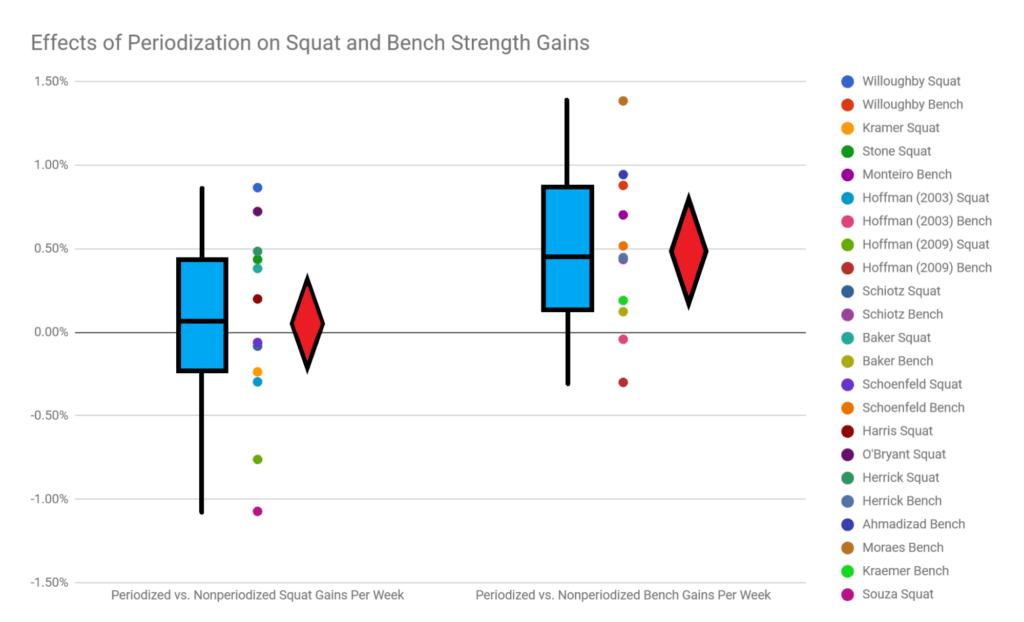

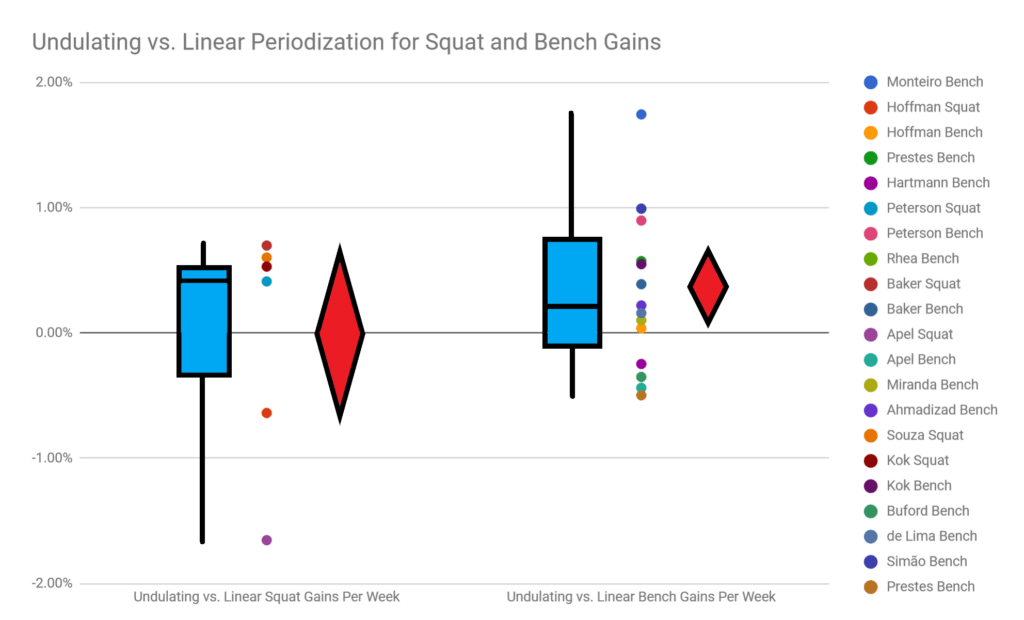

Squat vs. Bench Press

I found this bit very interesting: periodization and periodization style seem to affect bench press, but not squat.

Across all studies, periodized training led to an average increase in bench strength of 1.35% per week, while nonperiodized training led to an average increase of just 0.87% per week. On average, periodized training led to 55.43% faster bench gains (95% CI for all analyses: 22.43-88.43%, p<0.05). However, periodized and nonperiodized training led to essentially identical squat gains: 1.87% vs. 1.83% per week.

Values above zero mean faster gains for periodized

Across all studies, undulating periodization led to an average increase in bench strength of 1.63% per week, while linear periodization led to an average increase of just 1.28% per week. On average, undulating periodization led to 26.55% faster bench gains (95% CI for all analyses: 1.73-51.37%, p<0.05). However, undulating and linear periodization led to essentially identical squat gains: 2.35% vs. 2.36% per week, albeit with a sample of just six studies.

Values above zero mean faster gains for undulating

Do the effects of periodization or periodization style grow or shrink over time?

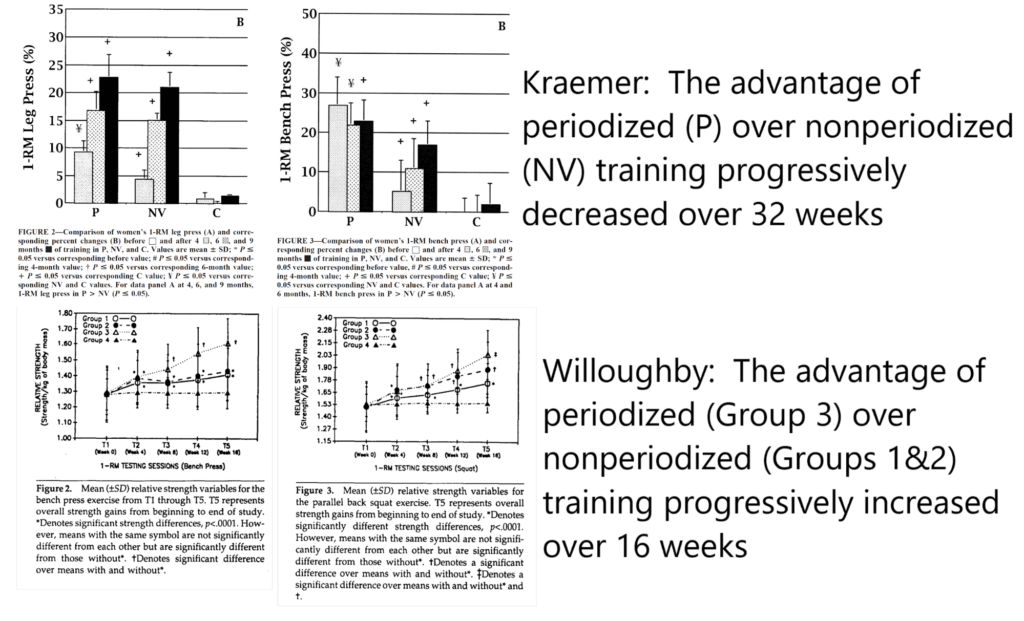

It’s unclear whether the advantage of periodized training over nonperiodized training increases or decreases over time. When looking at studies on trained lifters, untrained lifters, and all cohorts, there were no significant relationships between study length and relative advantage of periodization. When looking at individual studies that report strength gains at multiple time points, the picture is equally hazy. For example, Willoughby et. al report that the advantage of periodized training grew monthly over the course of a 16-week study, while Kraemer et al report that the advantage of periodized training was largest near the beginning of a 32-week study, with the advantage progressively diminishing over time. Of note, however, the effect of periodization on strength gains seems to be a bit larger (effect sizes of 0.31-0.46 vs. 0.23-0.30), and more consistent (significant effects in 3 of 4 analyses vs. 2 of 4 analyses) in trained lifters than in untrained lifters.

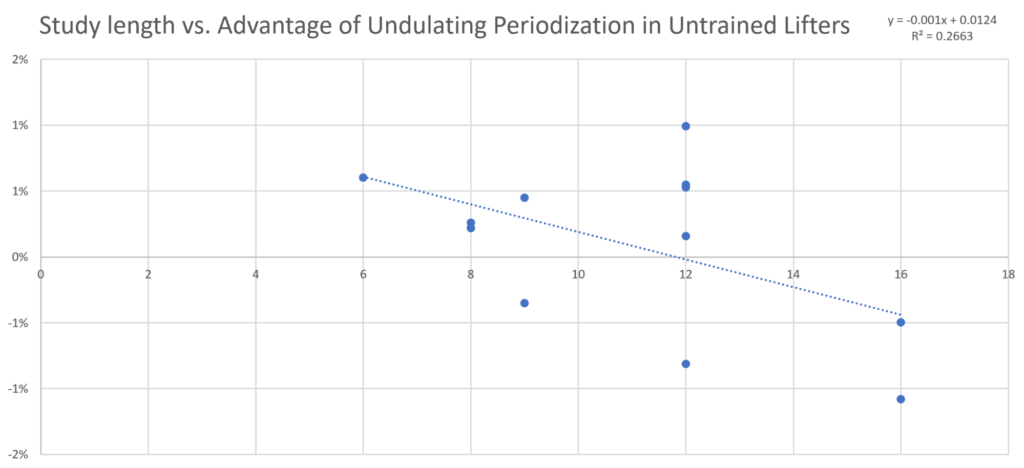

The advantage of undulating periodization over linear periodization may diminish over time. There were no significant relationships between study length and relative advantage of periodization, but there was a moderately strong inverse relationship in untrained lifters (r = -0.52, r2 = 0.27, p = 0.09). Furthermore, when looking at individual studies, all studies that ran longer than 12 weeks either found no difference between periodization styles, or they found that linear models outperformed undulating models. However, that may be making a mountain out of a molehill, as several 12-week studies found that undulating models outperformed linear models, and the studies that ran longer than 12 weeks only ran for up to 16 weeks – not exactly a tremendous difference.

X-axis = length of the study. Y-axis = strength gains per week with undulating periodization minus strength gains per week with linear periodization. Positive numbers mean faster gains with undulating periodization, while negative numbers mean faster gains with linear periodization.

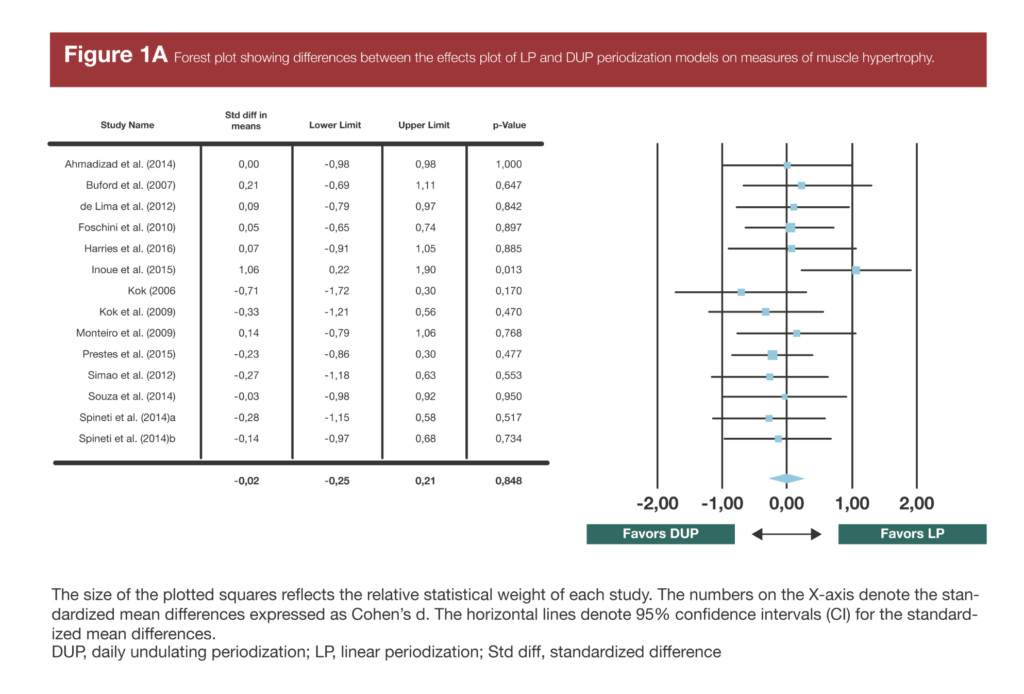

Hypertrophy

I’ll forgo my own analysis here, as there’s a very recent meta-analysis comparing the effects of UP and LP on hypertrophy, and an even more recent systematic review comparing the effects of periodized and nonperiodized training on hypertrophy (both by Grgic et al). In short, it doesn’t seem that periodization or periodization style affects hypertrophy to any meaningful degree, at least in the short term. However, it’s worth pointing out that rarely are studies designed to compare competing training theories proposed to maximize hypertrophy. Most of the time, studies use programs designed to maximize strength gains – strength is the primary outcome measure – and measures of hypertrophy are just secondary measures taken. We’ll need more studies using programs designed specifically to maximize hypertrophy – with hypertrophy as the main outcome – in order to know for sure whether periodization or periodization style affects muscle growth.

This figure, displaying the results of Grgic et al, first appeared in Volume 1, Issue 7 of MASS. Graphic credit: Katherine Whitfield

Interpretation

Here are some general thoughts about this analysis, in no particular order:

Overall, periodized training tends to produce larger strength gains than nonperiodized training, though the effect is pretty small. Of note, however, the effect is a bit larger and more consistent in trained lifters than in untrained lifters. The results here largely match those of Williams et al, once they removed outliers (i.e. studies comparing apples to oranges) and adjusted for nesting effects. That makes me a little more confident that I didn’t screw anything up too badly, even though I used a somewhat more simplistic method of analysis.

You can’t assume that findings in one population will apply to another population, or even that findings in one lift will apply to another lift.

- In this case, undulating periodization seemed to do considerably better than linear periodization for trained lifters (in fact, this was the biggest difference observed in any of the main analyses – even bigger than the effect of periodized vs. nonperiodized training), while there was no difference whatsoever for untrained lifters.

- Similarly, periodized training and undulating periodization beat the pants off nonperiodized training and linear periodization (respectively) for the bench press, while neither factor seemed to make any difference whatsoever for the squat. However, to hedge this finding a bit, it’s also possible that the bench findings are just more trustworthy than the squat findings. Rates of squat progress were 50-100% faster than rates of bench progress, possibly indicating lower overall training status for the squat (which makes sense – MOST people at the gym train bench harder than they train squat). So it’s possible that the gains that came from just practicing the squat more drowned out any possible effects of periodization or periodization style, whereas the bench results let us see the “true” effects.

- Is undulating periodization just a short-term strategy that essentially peaks lifters? If so, it would be good for short-term training, but may not be the best approach for long-term development. There’s some weak evidence for that notion from these data, but I’d caution against this interpretation, at least for now. The fact is, we don’t have any really long-term studies, and the trend seen with untrained lifters could have been a result of random variation. I have a hard time believing that UP produces larger gains than LP, on average, at 12 weeks, but an additional 2-4 weeks is sufficient to flip the script. Furthermore, since hypertrophy is similar with both LP and UP, I don’t see why you’d expect UP to fall short for long-term development. However, this is a possibility worth keeping in the back of your mind as more research is published.

Problems with the data

There are several problems with the research, in aggregate. Some are relatively minor issues, and some are larger problems.

The vast majority of the studies are pretty short. One study made it into this analysis that was 32 weeks long, but all the rest were between 6 and 16 weeks. As such, we have a fair amount of evidence about the short-term effects of periodization but very little data on the long-term effects. It may be tempting to assume that the short-term differences would compound over time, but it’s also possible that differences would diminish over time as well (which I think is likely, since hypertrophy seems to be similar). It’s also possible that novelty leads to short-term strength gains, with that effect diminishing over time (though I’m personally skeptical of that notion).

Lack of studies on highly trained lifters. I’m not the guy that joins in the “these guys didn’t even squat 600lbs, therefore this study is irrelevant. Lol” powerlifter circlejerk since propensity for strength gains varies so much, and since powerlifting tends to select for people who are more gifted than average. However, it’s hard to look at the rates of strength gains in the studies on trained lifters and conclude that most of these guys weren’t super well-trained. The trained lifters in these studies were gaining strength at a clip of 1.32-2.24% per week. That’s compared to a rate of 2.06-2.70% per week for untrained lifters. Call me crazy, but most people I’d consider “trained” don’t gain strength at 75% the rate of completely untrained folks, and they’re certainly not getting 1.5-2% stronger per week. As such, we’re left without much data on people most of us would really consider “trained lifters.”

Lack of matched peak intensity. This isn’t as much of an issue for the LP vs. UP studies, but it’s a major problem with the periodized training vs. nonperiodized training studies. A typical study comparing periodized and nonperiodized training would have the nonperiodized group working with a moderate load (typically 70-75% 1RM, or 10RM loads) the whole time, while the periodized group would work with loads covering a larger range (maybe 60% 1RM to 90%1RM, or 15RM to 3RM loads). Average intensity and volume would be matched, but ultimately, the periodized group would get practice with loads closer to 1RM loads, meaning they had an element of increased specificity compared to the nonperiodized group. In that case, are you really testing the effects of periodization per se, or are you (perhaps primarily) testing the effects of specificity?

Lack of standardization. The definitions of different periodization models can be a little slippery, and that’s reflected in the programs used in these studies. It would take forever to point out all of the examples of this, but you can see it in my spreadsheet. In the “program label” column, I made note of all of the classifications I thought a particular program design could have conformed to. With nonperiodized training and DUP, this was typically fairly straightforward, but a lot of the LP, WUP, and BP studies arguably incorporated other periodization elements.

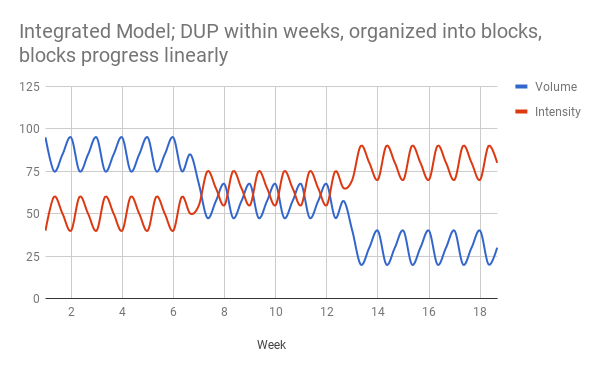

Testing either/or hypotheses. This is the complete opposite problem from problem 4. I’m honestly not convinced science is equipped to do a good job of answering questions about different periodization models. In science, you’re supposed to control all variables to the best of your ability apart from the one being tested – in this case, periodization model. However, in the real world, these concepts are almost never applied in an either/or way. You can undulate volume and intensity within a week if you train a lift multiple times, organize your training into discrete multi-week blocks with specific purposes, and progress intensity week-to-week to block-to-block all within the same training program, thus incorporating undulating, block, and linear elements. It doesn’t make much sense to me to test linear vs. undulating periodization, as if they’re two entirely disparate concepts, unless you’re also going to add in another group incorporating both linear and undulating aspects to see whether the two models have a beneficial interaction (no studies do this). Testing most ecologically valid hypotheses regarding periodization would require some uncontrolled variables (not gonna get published), or a ton of groups to test multiple interactions (not gonna get funded, and recruitment/logistics would be a nightmare), but the current approach of just testing models against each other doesn’t provide us with data that’s super useful in the real world, in my opinion.

This is a somewhat pedantic point, but I’m also not crazy about individual studies claiming to test “linear periodization vs. undulating periodization.” Ultimately, an individual study is just testing one training program against another training program. The two programs may serve as examples of two different periodization styles (or periodized training and nonperiodized training), but you can’t assume they serve as tremendously good representatives for an entire classification of possible programs. I think you need a big-picture overview (like this one) to meaningfully test hypotheses about periodization, incorporating the results from multiple studies using multiple programs that fall under the same umbrella of periodization style. This critique is similar to the “don’t put too much faith in a single study because the results of a single study may be off,” critique, but it’s a bit stronger. Something more like, “don’t put too much faith in a single periodization study, because one study isn’t capable of meaningfully testing a hypothesis about entire periodization models using single training programs in the first place.”

Takeaways

- Periodized training seems to produce faster, larger strength gains than nonperiodized training, regardless of training status. It’s not going to be a night-and-day difference, but it does seem to be a pretty consistent, meaningful effect.

- It’s probably wise to incorporate some undulations into trained lifters’ programs, and since DUP has been used more frequently in the research than WUP, it’s the option with more evidence to support it at the moment. Undulations may not affect strength gains for untrained lifters. Again, this doesn’t mean incorporating undulating at the exclusion of linear or block periodization elements. Those can (and probably should) be integrated.

- Periodization and periodization style may matter more for bench than for squat. I’d want to see some studies on powerlifters (who should be equally trained in both the bench and the squat) to be super confident with this takeaway, though.

- Periodization and periodization style don’t seem to affect hypertrophy, at least in the literature we currently have. This is to be expected, as most research equates volume between training programs, and volume is by far the biggest driver of hypertrophy. However, it’s possible (likely, I’d argue) that periodized plans designed to progressively increase volume over time would lead to greater hypertrophy than nonperiodized plans, or periodized plans that don’t focus on progressively increasing volume. That’s a hypothesis for future research to test.

Ideas for future periodization research

Consider having a standardized peaking block to follow the differentiated training intervention. This could help control for the differences in peak intensity seen in the studies comparing periodized training and nonperiodized training. If the folks doing nonperiodized training had big spikes in strength after a peaking block of heavier training, leading to the same overall outcomes as the folks doing periodized training, that would suggest that there may not actually be a meaningful difference for long-term development.

In a similar vein, it would be worth doing a study comparing periodized and nonperiodized training where training intensity of the nonperiodized group is matched to the peak intensity of the periodized group. If there ended up being no differences between groups, this would suggest that prior periodization research was confounded by higher specificity in the periodized groups (i.e. the differences would be more attributable to specificity than periodization per se). If there ended up still being a difference, with the periodized group gaining more strength, that would suggest that there is an actual benefit of periodization itself.

Future studies should replace a control group with an integrated group. It always irks me a bit when I see a resistance training study include a control group in the first place (for the most part; there are times when one is needed. This is not one of those times). We should know by now that lifting weights makes you stronger than not lifting weights. Instead, for studies comparing two periodization models, the control group could be replaced by a group using a combined program. For example, a study comparing linear and daily undulating periodization could have a linear group, and daily undulating group, and a third group matching average weekly intensity with the linear group, but still undulating within each week. This would test to see if the two models being used had an additive or synergistic effect. If it was found that the DUP group got better results than the LP group, but that the combined group got results similar to the DUP group, that would suggest that the difference in results was primarily due to the undulations, whereas if the combined group got better results than both other groups, that would suggest an additive or synergistic effect, meaning DUP and LP should be integrated.

Future studies should allow session volume to be autoregulated (RPE/RIR or bar speed cutoffs would make the most sense). It’s all well and good to test the effects of different periodization models when volume is equated, but people also hypothesize that certain models are superior because they allow people to handle more training volume. Allowing autoregulated volume would let you test this hypothesis, while also making the programs themselves more ecologically valid.

This can come off as a bit of a lazy complaint, but we really need studies with more highly trained lifters, and studies lasting longer (6-12+ months). Periodization is supposedly focused on long-term planning and athletic development, and is supposedly useful for helping high-level athletes continue to improve. We can’t really test those hypotheses without…long-term study and studies on high-level lifters (or, ideally, long-term studies on high-level lifters). I get that recruitment would be a bitch and that getting participants to enough training sessions and having people available to manage all the training sessions around breaks/vacations/etc. would be a logistical nightmare (which is why I’m not volunteering to do it!), but until that work is done, discussing periodization models for long-term strength development in high-level lifters isn’t science. It’s speculation.

We need periodization studies designed with hypertrophy as the primary outcome to really test whether periodization or periodization style affects hypertrophy. As noted before, strength is typically the primary outcome, so studies typically don’t use programs designed to maximize hypertrophy. Intensity is usually the main variable periodized, and volume just comes along for the ride. On the other hand, a study testing periodized vs. nonperiodized training for hypertrophy would need to treat volume as the primary variable periodized. For example, a nonperiodized group may do 10 sets of bench per week for 15 weeks, while a periodized group may do three-week blocks of 4 sets, 7 sets, 10 sets, 13 sets, and 16 sets per week.

Wrapping it up

Hey! You made it this far. If you want to read even more about periodization, here are some sources I’d strongly recommend. If you haven’t picked up on this by now, I’m interested enough in periodization to sink probably 100 hours of my life into reading all of these studies, conducting this analysis, and writing this article, but I’m also pretty skeptical and, in some ways, disappointed with the literature as it currently stands. I think there’s still merit in the extant literature, but I think the current findings are often used to support massively extrapolated conclusions, and I think there’s plenty of room for improvement moving forward. If you share my skepticism, you’ll enjoy these three pieces:

- Periodization paradigms in the 21st century: evidence-led or tradition-driven?

- Is Empirical Research on Periodization Trustworthy? A Comprehensive Review of Conceptual and Methodological Issues

- Periodization Theory: Confronting an Inconvenient Truth

Also, if you don’t trust my analysis, feel free to check out the reviews and meta-analyses on the topic. I referred to the Grgic reviews of hypertrophy directly, and my conclusions regarding periodized vs. nonperiodized training largely match Williams’, so I’m pretty confident in my analysis there. However, I believe my conclusion that UP outperforms LP for trained but not untrained lifters is a novel finding (Harries’ UP vs. LP meta didn’t investigate that question), along with my finding that periodized training and UP outperform nonperiodized training and LP (respectively) for the bench press but not the squat.

- Comparison of Periodized and Non-Periodized Resistance Training on Maximal Strength: A Meta-Analysis.

- A meta-analysis of periodized versus nonperiodized strength and power training programs.

- Effects of linear and daily undulating periodized resistance training programs on measures of muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

- Should resistance training programs aimed at muscular hypertrophy be periodized? A systematic review of periodized versus non-periodized approaches

- Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Linear and Undulating Periodized Resistance Training Programs on Muscular Strength

- Traditional vs. Undulating Periodization in the Context of Muscular Strength and Hypertrophy: A Meta-Analysis

And, as a final reminder, if you disagree with studies I included or excluded from my analyses, or if you don’t like the way I analyzed things, or if you just want to see if there’s good data to address a question not addressed in this article, feel free to use my spreadsheet to save yourself some time. I’m biased, so I think this is the best quantitative analysis of the research currently out there, but I don’t claim it’s perfect or that it’s the final word by any means.

That wraps up this installment in the series. Next time, I’ll be addressing practical aspects and applications of periodization for everyday lifters.

Addendum, May 2018

Two recent studies (reviewed in more depth in MASS) help us flesh out some of the concepts presented in this article in a bit more detail.

The first provides a bit more evidence that the advantage of periodized training over nonperiodized training may grow over time. In this 12-week study, smith machine back squat 1RM and quadriceps CSA were measured pre-training, at the mid-point of the study (6 weeks) and at the end of the study. One group used nonperiodized training, one group followed a linear periodized approach, and one group followed a DUP approach. Over the entire 12 weeks, strength gains and hypertrophy were similar in all three groups. However, strength gains slowed dramatically during the second half of the study for the subjects in the nonperiodized group (+3.7% from week 6 to week 12), and still progressed at a decent clip in the two periodized groups (+6.6% for DUP, and +8.8% for LP), suggesting that periodized training would be the superior choice for strength gains long-term.

The more interesting study, in my opinion, is the second one. If you’ll remember, I argued that the superiority of periodized training for strength gains may simply be attributable to the fact that in most study designs, periodized training programs include heavy training (85%+, or 3-5RM), while nonperiodized plans generally stick exclusively to moderate loads (70-80%, or 8-12RM loads). As such, we can’t know whether the enhanced strength gains are driven by periodization per se, or whether they’re simply driven by specificity. This study provided the first “fair” comparison in the literature. One group in this study used a nonperiodized approach, while the other used a weekly undulating periodized approach. Both groups trained with 4-6RM loads, 10-15RM loads, and 20-25RM loads. The nonperiodized group did two sets per session in each loading zone, while the WUP group did six sets in a single loading zone each session, alternating loading zones each week. As such, total volume, average intensity, and peak intensity were the same in both groups. Unsurprisingly (to me, at least), strength gains (leg press 1RM) were the same in both groups. I don’t want to make too big of a fuss over a single study, but I would really like to see more studies use a similar design (matching for volume, average intensity, and peak intensity) when comparing periodized and nonperiodized training.

Addendum, July 2018

A new study by Rodrigues et al. provides us with more data comparing linear and undulating periodization in lifters with some prior training experience. Long story short, both set-ups caused similar strength increases in the bench press and triceps pushdown. However, pre-training, the undulating group was almost twice as strong as the linear group, with an average bench press of 91kg compared to 54.7kg in the linear group. So, it’s possible that undulating periodization was more effective, but that its effectiveness was masked by groups that were dissimilar at baseline (assuming that weaker, less experienced people tend to gain strength faster than stronger, more experienced people).

Read Next

- Periodization: History and Theory

- The Complete Strength Training Guide

- The “Hypertrophy Range” – Fact or Fiction?