Second Punic War | UNRV Roman History (original) (raw)

Following its defeat in the First Punic War, the Carthaginian Empire looked to rebuild its power base by controlling Spain.

Hamilcar Barca, the premier Phoenician general, humiliated and angered over Rome's peace terms, and the seizure of Sardinia during Carthage's own mercenary war, looked to Spain as an overland launching point for future action against Rome.

Before long, Hamilcar would pass his hatred and obsession with Rome onto his son Hannibal, who would prove to be one of the greatest generals in history.

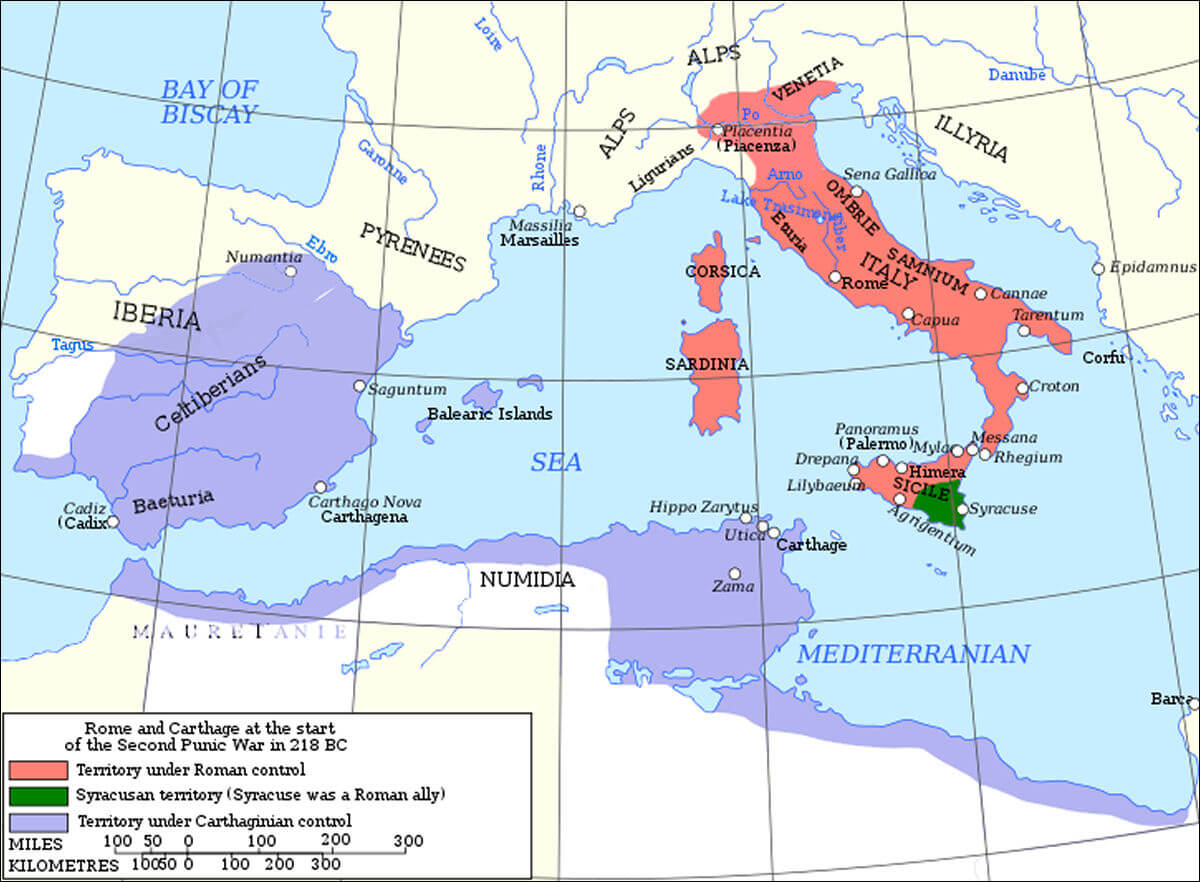

Grandiosederivative work : Augusta 89, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A map of the western Mediterranean Sea in 218 BC, showing Roman and Carthaginian territory at the start of the Second Punic War

By 220 BC, while the Romans were occupied in Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum, Hannibal, and his brother Hasdrubal established control of the Hispania peninsula as far north as the Ebro (Iberus) River.

Earlier, while Hamilcar was still establishing control of Spain, Rome was concerned over Carthaginian resurgence. In the 220's BC, they established a treaty with Carthage limiting expansion to anything south of the Ebro. Saguntum, a small town in that territory, had entered into an alliance with Rome, giving the Romans a small stronghold in the heart of Carthaginian lands.

Hannibal rose to power in 221 BC after the assassination of his father, Hamilcar. Instilled from birth with his father's hatred of Rome and raised to be a leader of men, Hannibal became the greatest threat to Rome in its history. With his assumption of command, he immediately set out to subdue rebellious tribes in his rear with his eventual goal to invade Italy.

Over the next year, Hannibal would be satisfied with the situation in Spain and looked to Saguntum to goad the Romans into war and justify his planned invasion. By 220 BC, Hannibal laid siege and opened the door to one of the ancient world's great wars.

After an eight month siege, Saguntum was captured. Having collected the spoils, Hannibal wintered in Carthago Nova while planning for his over Alps invasion of Italy in the Spring. Since Rome's victory in the first Punic War, the vaunted Carthaginian fleet was no match for Rome, and Hannibal knew that the Romans would only be vulnerable from an overland attack.

He hoped that by marching through southern Gaul and northern Italy, recent conflicts between the Romans and local tribes would boost his ranks with fresh, angry recruits.

Roman diplomatic attempts over the winter to seek justice from Carthage over Hannibal's siege met with failure. In negotiations with the Carthaginian capital, the Roman envoy Fabius made a last ditch effort to avert war.

According to Livy, pulling the folds of his toga into his hands Fabius said, "we bring you peace and war. Take which you will.'

Scarcely had he spoken when the answer no less proudly rang out: 'Whichever you please, we do not care.'

Fabius let the gathered folds fall, and cried: 'We give you war.'

Outbreak of the Second Punic War

The outbreak of the Second Punic War began when Hannibal moved north across Ebro to begin his historic march over the Alps.

Before leaving Spain, however, Hannibal was well aware that Roman forces intended for him would try to meet him there. He secured Spain with an army of about 16,000 men under the command of Hasdrubal and took 80,000 infantry, 12,000 Numidian and Iberian cavalry and a number of elephants with him on his march.

Early in the spring of 218 BC, Hannibal set out from Carthago Nova, for the Ebro River. He was confidant in Hasdrubal's ability in Spain, as his brother had campaigned with his father Hamilcar against the Iberian Celts since he was just a boy.

Unfortunately for Hasdrubal, Hannibal took all the senior command and elite troops with him on his march, which would play a role late in the war.

Hasdrubal's duty was to maintain Carthaginian dominion over Spain and to defend the primary interests (especially mines and resources) from Roman countering forces. With success in those primary goals, he was to raise an additional army and follow Hannibal to Italy.

After crossing the Ebro in April or May of 218 BC, Hannibal had little choice but to conquer local tribes as he moved. Leaving a violent population in his rear could've been disastrous, and despite the time delay and cost in casualties of operations against the Celts, he rapidly subdued the area. Except for the Greek coastal cities, which leaned towards Rome in diplomatic alliances, all of Spain was secure.

The general Hanno was left with 10,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry to keep the area between the Ebro and the Pyrenees under control.

With his rear secured, Hannibal continued north. Allowing some native Spanish troops to return to their homes (and possible transfer to Hasdrubals army) and deductions for Hanno's occupation force, he continued on with 50,000 men, 9,000 cavalry and his elephants. Later in the same year, 218 BC, Hannibal marched through the Pyrenees and into Gaul, never to return to Spain.

Once in Gaul, Hannibal was met with only slight resistance from the native Celts there. Along the march from the Pyrenees to the Rhodenus (Rhone), Hannibal's original planning started to bear fruit. The Gallic Celts were no friends of the Romans and many joined with him while en route.

According to Polybius, they crossed the Rhone at a distance of a 4 days march from the sea, using boats made by local Celts for the infantry and cavalry and large, flat earth covered wooden skiffs for the elephants.

During the crossing of the Rhone, Hannibal and his army finally started to meet some resistance. Gauls appeared on the opposite bank to disrupt the crossing, but Hannibal was ready. A force under Hanno was sent further upstream to cross and attack the Gauls in the rear. The successful maneuver ended the threat, and peaceful crossing resumed.

With the hostile Celts disposed, only friendly tribes remained on either side of the Alps, and Rome's only chance to stop Hannibal was to meet him at the Rhone.

Two Roman armies had been raised for the purposes of dealing with Carthage. The first, commanded by Publius Cornelius Scipio the Elder, was set to depart for Spain. The second, under the command of Tiberius Sempronius Longus, was originally intended to be an invasion force in Africa.

Hannibal's approach, among other factors, inspired a revolt among the Boii and Insubrian tribes in Cisapline Gaul, and Roman plans were forced to change. Scipio's army was circumvented from going to Spain and sent with Lucius Manlius to defend the Po Valley from the Gauls.

Sempronius' forces were already in Sicily preparing for the African invasion, and Scipio had to wait in Rome for another army to be raised before he could meet Hannibal marching east.

It wasn't long before another army was ready for Scipio. He and his brother Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio sailed to Massilia, in southeastern Gaul, with the intention of meeting Hannibal before he could reach the safety of the Alps.

Hannibal, however, had outmaneuvered the Romans and was already moving northward along the Rhone, with the intention of moving around the Romans and then south through the mountains.

The Romans knew they had no choice of stopping Hannibal's march and had to react. The army of Sempronius was brought up to the Po, and his invasion of Africa was scrapped. Scipio the Elder, returned to Italy to await the Carthaginians, while the bulk of his army went west with Gnaeus Scipio into Spain.

Upon his escape from the Roman roadblock, Hannibal moved into Transalpine Gaul territory occupied by the Boii. Knowing the local Celts' relationship with Rome, Hannibal took full advantage. The Celts were eager to help Hannibal cross the Alps, and their aid, knowing the safe passages, likely was a major factor in his successful march through them.

Prior to going through the mountains, however, Hannibal's army was undersupplied and exhausted after marching 750 miles from Carthago Nova to Transalpine Gaul.

A civil war being fought between two brothers of the same undetermined tribe in a very fertile region in the mountain foothills also worked in Hannibal's favor. In exchange for helping secure his position, the tribal chief fed the Carthaginians and provided enough supplies to see them through the rest of the journey.

By October of 218 BC, Hannibal and his menacing force were ready to cross the Alps into Italy.

The Invasion of Italy

While Hannibal's march through Gaul was relatively uncontested, the survival of his army through the Alps - let alone his subsequent victories - was a marvelous achievement. Malnourished, weather-beaten and exhausted, the Carthaginian force was met with resistance by many of the local Gallic tribes.

The Allobroges offered the first challenge by attacking the rear of his column. Other Celts harassed Hannibal's baggage trains, rolling large boulders from the heights onto the Carthaginian columns, causing panic and death among the victims.

Fierce resistance throughout the march debilitated Hannibal's army, and the cold altitudes of the Alps certainly were no benefit to some of the under-dressed tribal warriors in his forces.

Cold and hungry, Hannibal and his army stormed a Gallic town on the third day of the mountain hike. The resulting plunder offered some relief in the form of food and supplies, but constant pressure from the Celts, landslides, continuing bad weather and poor supply made the success of the operation all the more memorable.

By the 15th day, Hannibal stepped down into the foothills of northern Italy. With only 20,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry and only a few remaining elephants, his army was decimated by the journey. Fortunately for Hannibal, the Celts on the Italian side of the Alps were far friendlier, and Gallic recruits pushed the numbers of the Carthaginian army back up to between 30,000 and 40,000 men.

Meanwhile, the Romans were waiting in Cisalpine Gaul under Scipio the Elder. With a small force already positioned to keep the Gauls in check, Scipio moved to intercept Hannibal.

At the Battle of Ticinus, in late 218 BC, the two forces were first engaged in a small confrontation. Light troops sent by Scipio to scout the enemy were met by Numidian cavalry and soundly defeated.

As a prelude of things to come, the most significant result was the wounding of Scipio and the opening of additional Gallic recruitment to Hannibal. The Romans were forced to withdraw to Placentia, under Manlius, to plan for another attack.

With the minor victory at Ticinus, but more importantly the withdrawal of the Romans, Gallic and Ligurian recruits were now eager to join against Rome. Hannibal's army, significantly supplemented, was now ready to push full force into Italy.

At the Trebbia River, the Romans combined the forces of Scipio's remaining legions with those of Tiberius Sempronius Longus. In December of 218 BC, with Scipio out of commission from his wounds, the eager Sempronius threw caution to the wind and advanced against Hannibal.

The Battle of the Trebbia River was the first significant engagement of the war, and the first real test for Hannibal and his army. He brilliantly anticipated Sempronius' impetuousness and set up an ambush.

Before the impending fight, Hannibal sent a force of 2,000 - 1,000 each of infantry and cavalry - under the command of his brother Mago to conceal themselves in the riverbeds. When dawn broke, Numidian cavalry harassed the Roman camp, angering Sempronius and stirring him to action. The main Roman army approached the Trebbia, pushing the Numidians back across, completely unaware of the trap set for them.

Hannibal waited with his army arranged as a screen with 10,000 cavalry and elephants, flanking the infantry of 30,000. Sempronius faced him with upwards of 40,000 men. Roman light infantry (velites) met the enemy first and were badly beaten, though they would be largely responsible for eliminating the remainder of Hannibal's few elephants. Numidian cavalry crushed the Roman cavalry on the flanks and things were bad for Sempronius from the start.

When the main armies met, the situation stabilized slightly for Rome, but the flanking pressure from the superior Numidian cavalry soon began to turn the tide. At the critical juncture, Mago's ambush was sprung, and the Romans were finished. Demoralized by the bitter cold of December in northern Italy, the Romans were routed and cut down as they fled.

In the end, nearly half of Sempronius' force was lost, about 15 to 20,000 men. The remainder of the Roman army managed to escape to Placentia.

Hannibal's losses were far less. His elephants were gone, but of his regular army only the newly recruited Gauls suffered at all.

At Trebbia, Hannibal proved his superior leadership in understanding the psychology of his opponent, his tactical strategy and in propaganda warfare.

With his victory, Hannibal released the bulk of any prisoners captured with the intention of securing favor among Rome's allies throughout Italy.

While theoretically an excellent concept, it was this sort of continuing hope for open rebellion that played a major factor in his eventual undoing.

Hannibal's War in Italy

After Hannibal's victory at Trebbia and in the following spring's campaign season, the Romans appointed a new command for the Consul Flaminius.

Flaminius was brash and eager to meet the Carthaginian force and exact revenge for previous Roman losses. Hannibal, always the tactician, was well aware of the Roman commander's strategy and laid in wait.

Initially out-maneuvering his Roman adversaries, Hannibal looked for another spot to unleash a trap. He found a perfect one at Lake Trasimenus in April of 217 BC.

Hannibal set up an ambush that would force the Romans into open terrain, sandwiched between the northern shore of the lake and the opposite hilly ground. A Carthaginian decoy baited the Romans into following it into the trap, while the bulk of the main army occupied the high ground surrounding the northern lake shores.

The night before the battle commenced, Hannibal ordered his men to light camp fires on the hills of Tuoro, at a considerable distance, to give the impression that his army was much farther away. Flaminius fell for the ploy and walked through a long, foggy and narrow valley directly into the open land designed for the Carthaginian trap.

Early in the morning, Hannibal ordered a full assault on Flaminius, and the result was a complete massacre. Cavalry and infantry poured down from the hills into the unsuspecting Roman lines and caught them completely outside of their normal formations. Forced to fight in the open without the tightly formed legionary tactics, the Romans were driven against the lake and completely surrounded.

In the end, the Roman army of 25,000 lost as many as 15,000 including Flaminius himself. 4,000 cavalry reinforcements, sent late under Gaius Centenius, were also intercepted and finished off in the complete Carthaginian rout.

The ancients claimed that the blood was so thick in the Lake, that the name of a small stream feeding it was renamed Sanguineto, the Blood River.

When the news reached Rome, depression and fear reigned supreme. Hannibal had inflicted the biggest loss in Roman history on Flaminius and their manpower resources were quickly being depleted. Hannibal's strategy of encouraging revolt among the Roman allies could be devastating if Rome couldn't field any more legions.

To counteract Hannibal's methods, the Romans elected Fabius Maximus as dictator. In times of dire need, dictatorial power allowed a single man to develop strategies, make appointments and prepare the armies without the usual political wrangling.

Maximus, too, proved a brilliant choice, as his strategy of survival versus direct combat would prove its worth, despite the unpopularity.

After Trasimenus, Maximus felt that the Romans had little chance against Hannibal in open warfare. His tactics of delay and harassment did just enough to keep the Roman allies of central Italy from switching sides to Hannibal.

While Hannibal plundered and looted as he marched around the plains, he was unable to convince to people to rise with him. His generals, and his army, boosted by victory and with dreams of the ultimate prize, encouraged a direct siege on Rome itself to end the war.

Hannibal, however, was well aware that despite his superior skill on the battlefield, he lacked the numbers to successfully engage in a long term siege. Siege equipment was in short supply as well, and he looked for better options for his force.

Instead of moving directly on an open path to Rome, Hannibal turned south towards what he hoped would be better success among the people to join his cause.

Fabius Maximus, meanwhile, despite his efforts and success in keeping the economic and political stability of Rome at the status quo, was losing popularity among the Senate and the people. Romans wanted military success on the battlefield, not a war of attrition. Maximus' efforts to dwindle Hannibal's army, well aware of his problems in getting reinforcements, and wait for the right moment to strike were unappreciated by a nervous and anxious population.

The "Delayer" as Maximus was known, became a hated target, and his dictatorship didn't last long.

Hannibal crossed the Apennines and spent the summer of 217 BC scouring southern Italy. He invaded Picenum, Apulia and Campania, where his tactics of divide and conquer were beginning to bear more fruit.

Success in the south initiated a change within Rome. The people removed Fabius Maximus from his dictatorship and returned to the Consular elections. Gaius Terentius Varro and Lucius Aemilius Paullus were elected in his place, and it was their mission to remove Hannibal for good.

While the Carthaginians wintered in Gerontium, between 217 and 216 BC, the two new consuls raised a substantial army to deal with Hannibal once and for all.

In the Spring of 216 BC, Hannibal broke his winter camp and seized the large army supply depot at Cannae on the Aufidus River in Apulia. While the ancient sources vary, Varro and Paulus led upwards of 70 to 80,000 men after Hannibal.

Despite previous devastating losses, Roman tradition held that force could only be countered by force, and the large rebuilt Roman army would meet Hannibal at Cannae in August, 216 BC.

The Battle of Cannae

The newly elected Roman Consuls, Gaius Terentius Varro and Lucius Aemilius Paullus, who had both run on a platform of taking the war to Hannibal, were anxious to begin their tenure with military achievement.

Counter to the delaying tactics of the dictator Fabius Maximus, Varro and Paulus immediately formed a large force to deal with the Carthaginians ravaging southern Italy. While ancient sources offer conflicting reports, it can be safe to assume that between the two, Consuls, they levied a force of nearly 80,000 men.

Hannibal meanwhile, still attempting to subvert Roman authority in the allied areas of Italy, was waiting for the Romans with approximately 40,000 men; Gauls, Carthaginians and Numidian cavalry.

Despite the popular conception that the elephants played a major role in the campaign, by this time, all of his elephants had died.

Hannibal, despite his numerical inferiority, had such an overwhelming strategic edge, that he was eager to meet the new Roman challenge. Theoretically, the Roman tactic of crushing Hannibal between two large armies should have spelled his doom, but Hannibal's brilliance allowed him to turn the tables once the engagement got under way.

On August 2, 216 BC, in the Apulian plain, near Cannae and near the mouth of the Aufidus River, the two great armies came face to face.

The Consul Varro was in command on the first day for the Romans, as the consuls alternated commands as they marched. Paullus, it has been suggested, was opposed to the engagement as it was taking shape, but regardless, still brought his force to bear. The two armies positioned their lines and soon advanced against one another.

The cavalry was to meet first on the flanks. Hasdrubal, commanding the Numidians, quickly overpowered the inferior Romans on the right flank and routed them. Pushing them into the river and scattering any opposing infantry in his path, Hasdrubal dominated the right flank and was quickly able to get in the rear of the enemy lines.

While the much superior Numidians dealt quickly with their Roman counterparts, such was not the case with the infantry.

As Hasdrubal was routing the Roman horse, the mass of infantry on both sides advanced towards each other in the middle of the field. The Iberian and Gallic Celts on the Carthaginian side, while fierce, were no match for Roman armament and close-quartered combat.

Initially, the vast numerical advantage of the legions pushed deep into the middle of the Carthaginians. While the Celts were pushed back, they didn't break, however. They held as firm as they could, while Hasdrubal's cavalry pushed around to the rear of the enemy and the Carthaginian infantry held firm on the immediate flanks.

The Romans soon found that their success in the middle was pushing them into a potential disaster. As they victoriously fought farther into the center of Hannibal's lines, they were actually walking themselves right into being completely encircled.

Just as the Romans were on the brink of crushing the enemy center, the Carthaginian flanks were brought to bear and the pressure pinned in the Roman advance. Hasdrubals' cavalry completed the circle by forcing the rear of the Roman line to turn back and form a square. All around, the massive bulk of the Roman army was forced into confined space.

Hannibal brought his archers and slingers to bear and the result in the confines was devastating. Unable to continue the original break through against the Celts in the center of Hannibal's lines, the Romans were easy prey for the Carthaginians. Hannibal, with complete fury, encouraged his own men, under fear of the lash, if they weren't zealous enough in the slaughter.

In the midst of the battle the Consul, Paullus, was wounded (either early or late depending on Livy or Polybius as the source). He valiantly attempted to maintain the Roman ranks, though vainly. While the commander of the day, Varro, fled the battle, Paullus stayed the course, trying to save his army.

In the end, it was a terrible slaughter, and Paullus would be dead with the bulk of his men. Romans trying to escape were hamstrung as they ran, so the Carthaginians could concentrate on those who were still fighting, but allow time to return and kill the crippled later.

In a fast and furious display of death, Hannibal ordered his men to stand down only a few short hours after they originally encircled the enemy.

On a small strip of land where the Romans were bottled up, estimates as high as 60,000 corpses were piled one on top of another. Another 3,000 Romans were captured, and more staggered into villages surrounding the battlefield.

Hannibal, however, still trying to win the hearts of the Italian Roman allies, once again released the prisoners, much to the dismay of his commanders. In salute to the fallen Paullus, Hannibal also honored him with ceremonial rituals in recognition of his valiant actions.

In the end, perhaps only as many as 15,000 Romans managed to escape with Varro. These survivors were later reconstituted as two units and assigned to Sicily for the remainder of the war as punishment for their loss.

Along with Paullus, both of the Quaestors were killed, as well as 29 out of 48 military tribunes and an additional 80 other senators (at a time when the Roman Senate was no more than 300 men).

The rings signifying membership in the Senate and from those of Equestrian (Knight class or the elite class after Patrician) status were collected from the dead in baskets and later thrown onto the floor of the Carthaginian Senate in disrespect.

In contrast, Hannibal's losses numbered only between 6,000 and 7,000 men, most of whom were his Celtic recruits. Once again Hannibal proved brilliant in battlefield strategy, using the enemy's tactics against itself and routing an army twice the size of his own.

In less than a year since the disaster at Trasimenus, the Roman's greatest loss in history put the state into a panic. There was nothing keeping Hannibal from sacking Rome at this point, other than Hannibal himself. His generals again urged him to not waste any more effort and go for the final kill, but Hannibal was reluctant. Still believing he couldn't take Rome itself, he preferred his strategy of pursuing revolt among the Roman allies.

Despite this tremendous loss, the following defection of many allied cities, and the declaration of war by Philip of Macedon that was soon to come, the Romans showed a resiliency that defined them as people. According to Livy, "No other nation in the world could have suffered so tremendous a series of disasters and not been overwhelmed."

The truth of that nature was self evident. While some in the Senate, such as Lucius Caecilius Metellus were ready to abandon the Republic as a lost cause, others like Scipio propped up the flagging Roman spirit with encouragement and undying oaths of loyalty to Rome.

Shortly after Cannae, the Romans rallied back, declaring full mobilization. Another dictator, Marcus Junius Pera, was elected to stabilize the Republic. New legions were raised with conscripts from previous untouched citizen classes.

As the land owning population was heavily diminished by losses to Hannibal, the Romans took advantage of the masses. Those in debt were released from their obligations, non-land owners were recruited, and even slaves were freed to join the legions.

The Romans also refused to pay ransoms to Hannibal for any captured legionaries who still remained. Hannibal, it was suggested, lost his spirit, understanding that Rome would rather sacrifice its own than surrender anything to him.

While fortune would still be with Hannibal for some time, the war of attrition would only benefit Rome.

After the Battle of Cannae

Unflinching from his objectives, Hannibal, in the years 216 and 215 BC maintained his course of avoiding the siege of Rome. The primary theatre during this period of the war took place mainly in Campania.

Whether he considered the march itself too exhausting, a concern about a lack of supplies, or simple shock over his complete victory at Cannae, Hannibal refused to move on Rome.

Of supplies, Hannibal only received support directly from Carthage once, in 215 BC. Opposition to his war from the Carthaginian Senate, mainly from Hanno, along with Roman superiority at sea, prevented Hannibal from ever securing the resources needed to complete his conquests.

The victory at Cannae, however, began to take a toll on the Italian allies of Rome.

The Samnites - an old foe of Rome - some Apulian towns, and many others in the south switched sides to Hannibal. Only the Greek influenced cities along the coasts seemed to hold their loyalty firmly with Rome.

Late in 216 BC, Hannibal moved on Neapolis, but his attempts to take the city were repulsed. With winter approaching, the Carthaginians instead moved to the north and the town of Capua. Here, the residents welcomed Hannibal and his army, who used the city as its winter base until 215 BC.

At this time, Rome had placed Marcus Claudius Marcellus in command of its southern army, and he waited for Hannibal in the town of Nola. During the winter months, Hannibal made his move.

Up to this point, Hannibal was able to use his superior tactical leadership to his advantage, but for the first time he faced an able Roman commander.

Marcellus lured the Carthaginian army into believing he was occupied suppressing a revolt, and Hannibal engaged the Romans in a full assault. Severely outnumbered, Marcellus' trick worked and, with an inferior force, was able to fight Hannibal to a terribly bloody draw. Hannibal disengaged, neither victorious nor defeated, but for the first time, a Roman army proved that Hannibal was not unbeatable.

Despite Marcellus' good showing, Carthage was able to capture Acerrae, Casilinium and Arpi furthering his influence in central Italy.

After repulsing Hannibal at Nola, the Romans didn't have the power to take the offensive. An attempt to bottle the Carthaginians up at Apulia, under Fabius, resulted in the escape of Hannibal's army using oxen with burning sticks tied to their horns. Sent at night, the oxen confused Fabius into believing an attack was imminent, and Hannibal was able to avoid a potential disaster.

Hannibal needed reinforcements badly and the Romans, well aware of this issue, took up the original plan used by Fabius. They were to defend the loyal allied towns, recapture those towns that were within access and keep Hannibal on the move without engaging him directly.

215 BC proved to be a fateful year for Rome. In Sicily, Heiro II of Syracuse, a longtime Roman ally, died and his pro-Carthaginian son Hieronymos succeeded him. To the north, in Cisalpine Gaul, a Roman force was crushed by the Celts. In Macedonia, Philip V moved against Illyricum and Roman interests in Greece in open alliance with Hannibal. In Italy, Carthage finally sent at least a small force of reinforcements that joined Hannibal at Lucri.

To counter these set backs, Marcellus was sent to Sicily, an alliance with the Aetolian league of Greece was established to counter Philip, and Fabius maintained the status quo with his avoidance tactics in Italy.

While Marcellus moved to Sicily in 214 BC, the Carthaginian senate chose to make another grab for that island which was once theirs, rather than reinforce Hannibal.

Still desperately short of an army large enough to do more than capture small towns and wreak havoc on the countryside, Hannibal was forced to move south. Casilinum and Arpi were recaptured by Rome, but Hannibal looked to Tarentum as a long sought after port to receive reinforcements and supplies. Meanwhile, Hannibal's brother Hanno was kept busy suppressing a revolt against Carthage near Bruttium.

In 212 BC, through an act of treachery by local Tarentine nobles, Hannibal was able to capture Tarentum bloodlessly. Roman citizens were butchered while Tarentine locals were untouched, and Hannibal finally had his port. His brother Hanno, however, was defeated at Beneventum, further depleting the overall Carthaginian force.

Despite the success of Hannibal at Tarentum and the resistance of the Romans at Herdonea, the tide was slowly beginning to turn in Rome's favor. By the following year, Samnium and Apulia would both be back under Roman control and the path was open for the Romans to besiege Capua, Hannibal's former winter base.

In 211 BC, Hannibal desperately tried to relieve Capua by feigning an attack on Rome itself. Completely unmolested during the war Rome was prepared, however, and Hannibal could do little more than camp outside the Colline gates.

He was hoping that his feint on Rome would force the siege of Capua to be lifted, and draw the army out into the open where Hannibal could work his strategic magic. The defenses of Rome were too great and the Romans knew it, so they maintained their position. Hannibal was forced to march back south empty-handed.

Shortly afterwards, Capua fell to the Romans. In the aftermath, a great number of the Capuan citizenry was sold into slavery for punishment, and the land of the town was auctioned off to Roman citizens.

Meanwhile in Sicily, the new King of Syracuse, Heironymos, was murdered by Roman operatives for fear of his allegiance to Carthage. The effort backfired, however, and a civil war ensued, with pro-Carthaginian forces eventually taking control of the city.

Marcellus was sent to Sicily to restore Roman order with several legions, while the Carthaginians tried to re-establish themselves with an army of their own. The Carthaginian senate sanctioned an army of 25,000 infantry, 3,000 cavalry and 12 elephants that landed in Sicily in support of Syracuse, but they were to prove to be no match for Marcellus.

By 210 BC, Syracuse would fall - through siege - back into Roman control, and any remnants of Carthaginian resistance were gone. Marcellus was then able to cross back into Italy and put more pressure on Hannibal.

The End of the War in Italy

While Marcellus was leading the Romans to success in Sicily, Hannibal still ravaged the southern Italian countryside. In 210 BC, Hannibal led another victory over the Romans at Herdonea, where the Romans supposedly lost another 16,000 men.

Immediately thereafter, Marcellus crossed from Sicily and met Hannibal at the Battle of Numistro. Like before, when these two men met at Nola, a long bloody fight ensued that ended in a tactical draw. Hannibal withdrew and Marcellus followed.

While technically a draw, the Romans could afford such engagements. Hannibal, despite his heavily favored ratio of victories in the overall campaign, was becoming more and more desperate for reinforcements after every engagement; victory or defeat.

209 BC was a year clearly marked to change the tide in Rome's favor. As Marcellus cautiously pursued Hannibal's army that was constantly on the move, the Romans recaptured the port base of Tarentum. Though the Carthaginian sphere of influence was shrinking fast, Hannibal wasn't ready to concede just yet.

The following year, 208 BC, Hannibal continued to hold off the Romans. At Asculum, he defeated a vastly superior Roman numerical advantage, and shortly thereafter won a greater victory in a minor skirmish at Venusia.

At Venusia, Marcellus was killed in battle, and the "Sword of Rome," the only Roman general to give Hannibal a challenge, would no longer be an obstacle.

The death of Marcellus, though, provided little real improvement to Hannibal's fortunes. His army was dreadfully undermanned with poor moral, and he had no choice but to call for more forces from Hispania, where his brother Hasdrubal still commanded the defense of Carthaginian interests.

The war in Spain never went as well for Carthage as it did in Italy. With the assumption of overall command of all Roman forces there by Scipio the Younger (later Africanus) in 210 BC, Hasdrubal was constantly on the run.

As the new Carthaginian Empire in Hispania seemed to be a lost cause, Hasdrubal marched his army along a similar route as Hannibal's march through the Alps some 10 years earlier. Arriving in northern Italy in the Spring of 208 BC, Hasdrubal immediately set out to join with Hannibal in the south and bolster his brother's flagging army.

As Hasdrubal marched along the Adriatic, Hannibal was held in check in the south for fear of losing the loyalty of local allies and conquests he had gained in the region. Isolated along the eastern Italian coast, the Romans jumped at the chance to crush Hasdrubal before he could reinforce Hannibal.

Two Roman armies, under the commands of the Consuls Gaius Claudius Nero and Marcus Livius Salinator, met Hasdrubal near the Metaurus River in 207 BC. The 30,000 Carthaginians were outmatched from the start by the 35,000 - 40,000 Romans lined up against them. While the battle hung in the balance for some time, the superior numbers of Nero allowed him to eventually outflank and envelop Hasdrubal.

By the end of the day, 20,000 of the Carthaginian force, including a great many Gauls, were killed. Hasdrubal himself was also killed in battle, and his head was soon to be thrown into Hannibal's camp to demoralize him. As the remaining Gauls fled the battle, the Romans allowed them to leave, to spread the word of the great Roman victory and the re-establishment of dominance in Italy.

The Battle of Metaurus was the most pivotal battle of the entire war. Had Hasdrubal been victorious, a large enough force coming from north and south would have been able to move against the capital. The Roman victory assured that Hannibal would never be reinforced by a substantial force. Despite all of his previous victories, Rome could persevere.

Two years later, while Scipio pressed on, the last bastion of Carthaginian presence was removed from Hispania. Another brother of Hannibal, Mago, sailed with his remaining army from the siege of Carthago Nova, by way of the Balearic Islands, to Liguria in northern Italy.

Attempting to re-inspire the Gauls who were devastated after Metaurus, Mago stayed in Celtic territories to recruit anew. Soon after his arrival, however, the Romans met him and crushed his army, along with any Carthaginian hope of ultimate victory.

In the battle, Mago was wounded and another brother of Hannibal, Hanno, was killed. Mago took what little army he had left and joined Hannibal in Bruttium.

With the defeat of Hasdrubal and Mago, Rome was free to conduct operations against Carthage in retaliation for its invasion of Italy. While Hannibal managed to stave off his own defeat while being bottled up in Bruttium for four more years, Scipio was able to plan the invasion of Africa.

Leaving a substantial force to bring Spain under Roman control, Scipio, recently elected Consul, moved to Sicily and organized the forces left there from earlier campaigns. By 204 BC, Scipio crossed the Mediterranean and invaded Africa.

Roman success within a year forced Hannibal and Mago to be recalled for the defense of Carthage, though Mago would die en route. In 203 BC Hannibal sailed his remaining army of some 15,000 men back home and the war in Italy was over.

The fate of Carthage rested in Hannibal's defense against Scipio Africanus.

The First Punic War in Spain (218-214 BC)

While Hannibal was making his march across the Alps, the Romans took the fight and retaliation for Saguntum, directly to the Carthaginians in Spain. An invasion by a Roman Consular army under Publius Cornelius Scipio was launched in 218 BC, but a revolt among the Celts in Cisalpine Gaul forced a change in the plans. P. Cornelius Scipio returned to Italy to deal with the revolt and the impending arrival of Hannibal, while his brother Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio, took the invasionary army on to Hispania. Gnaeus had under his command an initial force numbering 22,000 infantry, 2,200 cavalry and a strong fleet of 60 quinqueremes.

Gnaeus Scipio landed at Emporiae in NE Hispania, in October 218 BC and immediately advanced south, taking control of territory as far as Tarraco. Uncontested by Carthaginian resistance as he marched, he set to work subjugating local Iberian Celts. Hannibal's brother, Hanno, left in command in Northern Spain, decided to meet Scipio despite commanding a far inferior force. Outnumbered by as many as 2 to 1, Hanno's army was crushed near the town of Cissa, and Hanno himself was captured. As a result and from the very outset of the Roman invasion, Rome was able to secure a port as a supply base and also immediately nullify Spain as a source of supply and reinforcement for Hannibal in Italy.

In 217 BC, Hasdrubal, now in command of the Carthaginian forces, recruited heavily among the local Iberians. His fleet was brought to a strength of about 40 ships under Himilco. He advanced on Scipio's position on the Ebro River with his combined ground and naval forces, but his fleet was caught completely by surprise by a recently reinforced contingent of Roman ships. With the victory on the Ebro, the domination of the Roman navy was never again challenged throughout the length of the entire war. Shipping lanes and Carthaginian ports were blockaded and controlled which would eventually have a significant impact on Hannibal's campaign in Italy.

After the victory at the Ebro, the Roman senate sent Publius Scipio back to Spain with reinforcements of 8,000 men. Gnaeus raided the Balearic Islands to put down a revolt of the local Iberians and Publius took control of the overall navy. In the year 216 BC, both Roman and Carthaginian commands were occupied consolidating control over their own territories rather than fighting one another. The Romans grappled with King Indibilis and his Balearic Iberians, and Hasdrubal with the Tartesii tribe. Because of the Tartesii, Hasdrubal, despite recent reinforcements of 4,000 infantry and 500 cavalry from Africa, had to postpone any plans to check the Roman advance until the following year.

With the opening of the campaign season in 215 BC, Hasdrubal Barca led his army of 30,000 north to meet the Romans. The Scipios meanwhile, with a comparable force moved south to block Hasdrubal at the Ebro. At the small town of Detrosia, the armies met in very similar conditions to those that unfolded for Hannibal at Cannae. Hasdrubal's plan all along was to mimic Hannibal's strategy and hold the Roman infantry in the center while his cavalry enveloped the flanks. Unlike Hannibal's army, Hasdrubal lacked the disciplined cavalry of his brother and the result was a far different outcome. Quickly after the battle opened, the Scipios recognized the strategy and effectively countered it. In the end, Hasdrubal's army was routed and its effects were felt throughout the course of the entire war.

The defeat at Dertosia was monumental for the Carthaginians. Many local Iberian tribes shifted their allegiance to Rome, and control of the vast mineral wealth of Spain was slowly crumbling. The Romans seized several cities south of the Ebro and took control of territory belonging to the Carthaginian allied tribes, the Intibili and the Illiturgi. The arrival of Mago with 12,000 infantry, 1,500 cavalry and 20 elephants helped to avert complete disaster for Carthage, but its effect on Hannibal in Italy was profound. Mago had been enroute to join Hannibal and the diversion helped stem the Roman advance in Hispania but reduced the overall effectiveness of the Italian campaign.

The Second Punic War in Spain (214-211 BC)

By 214 BC, Mago and Hasdrubal had levied new forces and decided to strike first. Advancing into the territory of some of Rome's new Spanish allies near Acra Leuce they defeated the local tribal forces. Publius Scipio moved quickly to counter the new offensive but was ambushed by the Punic cavalry, losing 2,000 men. He withdrew northward to rendezvous with Gnaeus Scipio's army, just as a third Carthaginian force commanded by Hasdrubal Gisgo, arrived from Africa. These five armies (3 Carthaginian, 2 Roman) engaged in a series of actions around the cities of the Iliturgi and Intibili in east-central Hispania with the Carthaginians pressing the action. In the end of the campaign season, the Romans maintained control of the newly won territory, but Gnaeus had been seriously injured in combat.

The next three years saw the jockeying of position for both sides. The three Carthaginian armies were content to harass the Romans while maintaining control of their power base in the south of Spain. The Romans, without reinforcements of their own since their arrival several years earlier, were also limited in choices. Because of the limited manpower resources, advancement required leaving too many troops in the rear to maintain supply and communication lines, making any gains untenable. The Carthaginians faced difficulties of their own in the form of revolts in Africa. King Syphax of the Numidians rose against Carthage, an uprising eagerly incited by the Romans, troubling the Carthaginian's cause in Spain even further. As a result Spanish forces were sent to Africa to help quell the rebellion, but rather than putting it to an end, Syphax was able to withdraw via Gibraltar and add his vaunted Numidian cavalry to the Roman cause. Through the whole affair, the Scipios took advantage of the situation and recaptured the site that started the entire war, Saguntum. They also made inroads with the Celtiberians and were able to recruit an additional army of 20,000 tribesmen.

The beginning of 211 BC proved to be a much better year for the Barca clan. At the time, between the 3 armies, estimates of 35,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry and 30 elephants have been given for the total Carthaginian force. Conversely, the Romans had nearly 50,000 mixed legionary and Celtic infantry with an additional 5,000 cavalry. The Roman plan for the season was simple, engage and defeat the Carthaginian ground forces. The problem however, was that the Carthaginians were so evenly divided between 3 separate armies, that Roman advances against one force would leave their territory vulnerable to an unoccupied Carthaginian army.

As a result the Scipios divided their armies to attempt to meet the multiple Carthaginian forces. Gnaeus went after Hasrubal with an army twice his size, while Publius moved against Mago. Hasdrubal, though heavily outnumbered, managed to hold off the Roman advance. Learning that the bulk of his opposition was made up of the Celtic warriors, Hasrubal arranged to pay off the Celts and send them home leaving Gnaeus with only a small contingent of actual legionaries. Left completely vulnerable, Gnaeus Scipio had little recourse but to slowly withdraw while holding off Hasdrubal's attacks.

Publius Scipio, advancing on Mago near Castulo, had his own problems. Mago, was reinforced by Gisgo and additional Numidian cavalry under Masinissa. Approaching the enemy, Publius found himself walking into a hornet's nest, being stung on all sides. Trying to maneuver out of his difficulties, he soon discovered that an additional force under Indibilis of the Balearic Islands was approaching his flank. Surrounded and now outnumbered, Publius Cornelius Scipio was killed and his army of 23,000 men were destroyed at the Battle of Castulo (211 BC).

With one Roman army destroyed the separate Carthaginian forces now converged with Hasdrubal on Gnaeus. Unaware of his brother's fate, Gnaeus would surely try to withdraw when he found out, so the Carthaginians moved fast to prevent any escape. As the enemy approached in formation, Scipio realized that he faced the entire army of the Carthaginians in Hispania and attemped a quick withdrawal from open battle. He occupied high ground on a hill near Ilorca and immediately began fortifying, preparing for a siege. His efforts were in vain, however, as the Punic armies stormed the hastily construced defenses and destroyed the army of the Romans. Within 30 days of his brother's death at Castulo, Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio met the same fate at the Battle of Ilorca.

The stunning victories caught both the victors and the defeated off-guard. The Carthaginians, now in total command of Hispania, were seemingly ill prepared for total victory and failed to capitalize on the opportunity. Reinforcements could've been sent to Hannibal in Italy, or against gains in the north of Spain, but instead their interest in victory seemed to wane. Instead the Carthaginians spent the following months again consolidating their positions and reaffirming control of the south. In Rome, the defeats were obviously shocking but were greeted with a resolute response. The Senate immediately dispatched C. Claudius Nero to shore up the remaining garrisons in Spain. Victories over Syracuse in Sicily and at Capua in Italy allowed the Romans to send some reinforcements and plan for the next year's campaign. At the end of 211 BC, the positions of both sides were exactly the same as when the war had started in 218. The Romans, thanks to Marcius Septimus who saved the remnants of the defeated Roman armies by withdrawing north after the battles Castulo and Ilorca, and his replacement Nero, managed to hold onto territory north of the Ebro while the Carthaginians had regained complete authority over everything south.

The Third Punic War in Spain (210-207 BC)

After the Roman defeats at Castulo and Ilorca, the situation in Spain was desperate. The Senate appointed C. Claudius Nero to command there, but his presence was to prove only a temporary affair. In 210 BC the desperation was apparent in the granting of imperium to the young Publius Cornelius Scipio. At only 25 years of age, the legal age for a praetorship, Scipio, likely in sympathy over the death of his father and uncle, was unanimously elected the overall command of the campaign in Spain. He left Rome with an army of 10,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry and like his uncle before him, landed at Emporiae. Consolidating with the remaining forces still left in Spain, he began his campaign with 28,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry, and would receive no reinforcements from Italy for the remainder of the war.

From his base in Tarraco, Scipio immediately set about boosting the morale of his troops and securing alliances with local Celtiberian tribes. Also scouting the enemy during the winter before his first campaign, he discovered that the Carthaginian forces were not only still divided in three forces, but that in-fighting between them seemed to show a lack of cooperation. Hasdrubal, Mago and Hasdrubal Gisgo each had as many troops as Scipio's single army, but it became apparent that 3 separate campaigns of conquest could be planned. The Carthaginian base of Carthago Nova soon developed as Scipio's first target, with a garrison of 1,000 men he surmised that its defeat would not only be easy, but would be a major blow to the enemy in the heart of its territory.

In early 209 BC, Scipio set out with 25,000 men and 30 ships under the command of Gaius Laelius. Arriving at Carthago Nova in complete surprise, he fortified his own position to protect himself from Carthaginian reinforcements and prepared for the assault on the city. After two attempts to take the city by direct attack, Scipio employed a strategy of assaulting the small garrison from several sides. Completely outnumbered and unable to face the Romans from so many points, a marine force was able to storm the gates and gain entry to the city. At first, the Romans massacred the inhabitants in order to flush out any remaining resistance but when the Carthaginian commander (another Mago) surrendered, Scipio ordered the end of the slaughter.

The capture of Carthago Nova not only drove a wedge into the heart of Carthaginian Spain, it gave the Romans much needed military stores and supplies, access to local silver mines, an excellent harbor and a perfectly positioned base for further operations in southern Spain. Scipio's treatment of the locals once the battle was over was exemplary. Carthaginian citizens were set free and they were allowed to keep their property. Artisans were promised freedom if they continued to work in Roman service. He also recruited heavily among the locals as naval rowers and additional auxiliary forces, not only supplementing his own forces, but giving the impression that the people were allies to Rome rather than enemies.

After Carthago Nova was secure, Scipio moved his main force to Tarraco where he spent the remainder of the year training and drilling his men. Under Scipio, the Romans abandoned their traditional Italian gladius for one used by Celtiberians. The Spanish short sword (Gladius Hispaniensis) was better suited for close quartered legionary tactics and it would soon become the primary sword of the entire Roman army.

The Carthaginians meanwhile, seriously devoid of any naval capacity were unable to retaliate at Carthago Nova. In the aftermath of its loss to Rome, they had little choice but to keep focused on quelling local tribes before they defected to the enemy. In effect, Rome had accomplished in Hispania what Hannibal had attempted to do in Italy, turning the inhabitants against the traditional power. Hasdrubal had begun recruiting an army to reinforce Hannibal in Italy, but Scipio and his extensive network of scouts were well aware of these plans. In the campaign year of 208 BC, Scipio marched south to Baecula to meet the unsuspecting Hasdrubal.

Near the Baetis River, the battle of Baecula faced 40,000 to 50,000 Romans against as many as 30,000 Carthaginian forces. Hasdrubal immediately withdrew to his camp and prepared for the defense when the Romans approached. While the enemy formed in a defensive posture, Scipio was able to outflank the enemy and quickly took command of the field. Hasdrubal wisely realized he was outmatched and retreated to safety in the Carthaginian dominated interior of Hispania. While the Carthaginians lost as much as half or 2/3rds of its army, Hasdrubal was able to save enough of it to continue with his planned reinforcement of Hannibal. Scipio, though later widely criticized, knew that pursuit into the interior of Spain would have been folly and let Hasdrubal go, choosing instead to focus on the remaining Carthaginian forces and strongholds.

After Baecula, Hasdrubal moved to reinforce Hannibal in Italy with his remaining army and Scipio moved against the armies of Mago and Hasdrubal Gisgo. Reinforced by the local Spanish tribes who hailed him as a King (though he refused this), Scipio was in excellent position to deal a deathblow to Carthage. One of his generals, Silanus, was sent with 10,000 infantry and 500 cavalry on a forced march to attack Mago in his training camp. Recently reinforced by Hanno from Africa, the Carthaginians outnumbered the Roman force, but Silanus' attack was a complete surprise. Mago and Hanno were utterly defeated and any recent Carthaginian levies were scattered beyond hope of recovery. Hanno was captured while Mago salvaged what little was left of his army and retreated to Gades joining Hasdrubal Gisgo, who had wisely moved out of reach of Scipio when news of the battle had reached him.

Meanwhile, an army under the command of Marcius harassed and assaulted pro-Carthaginian Iberian tribes in an attempt to eliminate what remained of their recruiting base. Both he and Scipio spent the remainder of the year spreading Roman control while preparing for the final campaign to eliminate the Carthaginian presence in Hispania. News of Hasdrubal's complete defeat in upper Italy after escaping Scipio arrived at this time and Carthage was clearly on the defensive in all theatres for this first time in the war. While the year 207 BC was drawing to a close, both sides prepared for what would prove to be the final battle between the two forces in Hispania.

The End of the War in Spain

The Carthaginians spent the winter of 207 and 206 BC once again recruiting amongst the locals for a final effort against Scipio. In the spring of 206 BC Mago and Hasdrubal Gisgo marched from Gades with between 50,000 and 70,000 infantry, 4,000 to 5,000 cavalry and 32 war elephants. Scipio also prepared for the final campaign in securing new recruits among local Roman allies. Weakened by the need to garrison so many new conquests, the Romans were left with only a small contingent of actual legionaries among 45,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry. Despite this, Scipio was ready to put an end to the war in Spain and he marched to Illipa to meet the advancing Carthaginian army.

Because of Scipio's brilliant tactical ability his inferiority in numbers (and an army made up of mostly non Romans) didn't make a difference. Preparing for a single and final decidng battle Scipio positioned his forces to prevent a Carthaginian retreat to their base at Gades. Much like the tactics of Hannibal in Italy, Scipio set up a cavalry ambush and lured Mago to attack. Mago moved against Scipio believing he was in the superior position and the trap was unleashed. The Carthaginians were initially driven back but managed to recover and extend the battle over a course of a few days. As it continued both lines were arranged in similar patterns on the field, with the main infantry of both armies occupying the center, flanked by local tribesman. On the final day, Scipio rearranged his formation with the tribesmen in the middle flanked by regular legionaries.

Scipio launched his attack at first light, and caught by surprise the Carthaginians were overwhelmed. During the protracted battle the Carthaginians, who had gone without breakfast were certainly hungry and exhausted throughout the day, succumbed to the Roman onslaught. A heavy rain late in the day delayed the inevitable, but because Scipio had earlier cut off the retreat route to Gades, the entire force of Mago and Hasdrubal Gisgo was soon enveloped and destroyed. The battle was a great victory for Rome, and Scipio in particular, was assured greatness in history as one of the ancient world's greatest generals.

Fighting illness, Scipio continued the campaign against the remnants of Carthaginian resistance. Moving against Gades, Scipio's illness worsened and at some point many believed he had died. His troops had long been operating unpaid and the recent plunder from various expeditions roused them into a mutinous state. Believing Scipio was too ill, or perhaps even dead, to make good on payments, they revolted on the Sucro River in 206 BC. The mutiny was quickly quelled as Scipio recovered, payments were arranged and the ringleaders executed, and operations soon continued as normal.

By the end of the year, 206 BC, Gades was also captured and several Spanish tribes also fell under the Roman sword. Advance political arrangements were made with several African tribes to aid in the eventual invasion of Africa. By 205 BC, Mago, knowing the cause in Spain was lost, sailed from Liguria to Italy in an attempt to join with Hannibal but was subsequently defeated in Cisalpine Gaul much like Hasdrubal before him. All evidence of Carthaginian resistance was gone, and the Romans stood as the new masters of Spain. Scipio left the Roman garrison and returned to Rome to be elected Consul. From there, he continued on to Sicily to prepare for the invasion of Carthage itself on the African mainland. He proved his worth to Rome and fought a brilliant campaign in Spain. The only blemishes on his record, for which he would be furiously punished politically by Cato the Elder years later, were his failure to stop Hasdrubal from escaping to Italy, and the short-lived and uneventful mutiny in 206 BC. However, even though the final conquest of Hispania would take another 2 centuries, the campaigns of Scipio in the far west of Europe helped establish Rome as the ultimate power of the Mediterranean.

The Invasion of Africa

Publius Cornelius Scipio debarked for Sicily in 205 BC with an army of volunteers, to meet up with forces (the survivors from Cannae) assigned to him there. As a furious debate raged in the Senate as to the next course of action, no new levies were authorized for the invasion of Africa, but Scipio was allowed to prepare his campaign. Allied arrangements were made with various African tribes, Libyans, Moors and the Numidian Prince Massinissa to assist in the coming invasion.

In 204 BC Scipio crossed the sea and landed in North Africa with a veteran army of as many as 35,000 men. While Scipio had retained the services of Masinissa, another Numidian, King Syphax, maintained his loyalty to Carthage. Both sides of the Numidian forces had already been at war, and while being used to the advantage of both Rome and Carthage, both also sought favor by the two warring parties. Masinissa had been on the losing end of most engagements with Syphax, but he still was able to provide Scipio with 6,000 infantry and 4,000 of the vaunted Numidian cavalry.

At the start of the campaign, Scipio moved on Utica and laid siege. Met by a joint army of Carthaginians and Numidians, led y Syphax and Hasdrubal Gisgo, he was pinned along the shore of the African coast for a time and forced to lift the siege. For the winter of 204 to 203 BC, both armies waited in their own camps until the following spring. At the start of the 203 BC season, Scipio launched a surprise attack, burning the camps of the enemy and creating mass panic. In the end, 40,000 enemy troops were dead with an additional 5,000 prisoners taken, but both Syphax and Hasdrubal escaped. With the quick victory, Scipio resumed his siege of Utica, while the Carthaginians immediately began recruiting another army.

Soon after, another Carthaginian force of about 30,000 men began to muster at the Great Plains of the Bagrades River. Scipio moved away from his siege of Utica and swept down in force on the green army. The Romans smashed the defenders, this time in a double flanking maneuver, but Hasdrubal and Syphax were able to escape once again.

Late in the year 203 BC, Syphax was still operating with a small force near Cirta. Scipio dispatched Laelius and Masinissa, the allied Numidian king with a partial force to end the threat once and for all, while he maintained the siege of Utica. Near the Ampsaga River, Syphax fought his last battle as his outmatched force was badly beaten. Masinissa capured Syphax and took him to Cirta, whereby the city surrendered without resistance.

With this defeat and the fall of Utica, Carthage had little choice but to sue for peace and accept Scipio's harsh terms. Carthage, however, had recalled Hannibal from Italy and seemed to accept the terms only to give Hannibal enough time to return. As Hannibal was making the dangerous voyage back to Africa (trying to avoid the powerful Roman fleets) with his veteran army, a Roman supply fleet ran aground near Carthage and it was seized and plundered by the locals. Envoys sent to Carthage to complain about this violation of the newly ratified peace treaty were promptly attacked, and Scipio had no choice but to renew his offensive. He laid waste to the interior towns of Carthaginian territory and met with Masinissa and his Numidian cavalry near the Bagrades River. By this time, in 202 BC, Hannibal had also returned and recruited a new army of 25,000 men to supplement his 12,000 veterans. Marching towards Scipio, the two armies met near Zama on the plains of the Bagrades River.

The Battle of Zama

In 202 BC, Hannibal learned that Publius Cornelius Scipio was devastating the area around Zama and left his base in Hadrumetum to confront him. Carthage was heavily dependent on the fertile grain production of the area and had no choice but meet the threat, despite Hannibal's recently recruited and poorly trained army. Scipio also was well aware of Hannibal's great ability in a defensive position, especially around Carthage. He hoped that his activities in the important area near Zama would draw Hannibal away from his defensive works at Hadrumetum and Carthage. It also provided an opportunity to link up with Masinissa's cavalry operating in the same area.

Hannibal, by this time had managed to gather as many as 40,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry to confront the smaller force of Scipio with 30,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry. Though at the time the march began, Masinissa had not yet reached Scipio and Carthaginian spies were allowed into the Roman camp so they would see the lack of cavalry on hand. Encouraged, Hannibal hurried to Scipio's camp intending to use his own cavalry to overwhelm the Romans, unaware that Masinissa and his vaunted Numidians would soon arrive.

As the two armies were drawn up in their lines, Hannibal requested a meeting directly with Scipio. With the two armies drawn up in battle formation, Hannibal met Scipio in an indecisive parley. Hannibal felt that, though Rome had the advantage in the war, his superior strength on the field could save Carthage from any further destruction. He offered Spain, Sicily and Sardinia to Rome along with the guarantee that Carthage would never again attack, but Scipio refused. Knowing that Masinissa would arrive shortly, the scale would tip back towards the Romans in terms of battlefield strength, and Hannibal didn't offer anything that the Romans hadn't already won. After the time gained through the parlay, Masinissa arrived and avoided an attempt by Hannibal to prevent the merger.

Scipio chose the site of his own camp for the battle, situated on a natural spring. Hannibal meanwhile was deep within African territory without an easily accessible source of water for his army. The flat plain was to be the future site of the Roman colony of Zama, and the battle was named for this colony 150 years after it happened.

Hannibal's plan was a basic recreation of his tactics at Cannae. While a sound plan he failed to take several things into account. His cavalry was inferior to that of the Romans, his army consisted of a great many inexperienced recruits, and now he faced a general as capable as himself in Scipio, rather than the inept leadership shown by the Romans in Italy. Hannibal placed all of his elephants in the front of his army, with mixed infantry behind and cavalry on the flanks. He hoped the elephants would route the central lines of the Romans while his cavalry could envelope it from the flanks.

The battle opened with the elephants charging the Roman lines. While a frightening sight to the Romans, Scipio's plan worked and the elephants went neatly into the open lanes. Scipio's men shouted and banged their swords on their shields, archers attacked the riders, and the spearman attacked the sides of the elephants. The great beasts quickly panicked and turned on their own lines to escape the carnage. They moved directly against Hannibal's own cavalry essentially wiping out one entire flank. Now without his elephants and an already inferior cavalry only weaker by this disaster, Hannibal was in deep trouble before the infantry even met.

Scipio then turned the tables and used much the same tactics at Zama as Hannibal had at Cannae. His cavalry pushed Hannibal's aside with ease, driving them off, and the infantry met in the center. At first, the Roman front line was beaten badly in the center, but Scipio left more men in reserve, forcing Hannibal to leave some men uncommitted. Before long, the regular legionaries began to push back the front of Hannibal's force, but their own reserve line wouldn't let the retreating Carthaginian's through the lines to safety. While Hannibal's front lines were destroyed, his own vaunted veterans stood in the Roman's path. Both armies extended their lines as long as possible to prevent being flanked, and Scipio failed to encircle Hannibal. Both lines fought fiercely with neither infantry gaining an advantage and it looked as if Scipio's plan to emulate Cannae might fail. At the critical juncture, however, the Roman and Numidian cavalry broke off its pursuit of the fleeing Carthaginian cavalry and returned to attack Hannibal's flanks. Despite the brilliance of his veterans, the Carthaginians had no chance while being crushed on all sides. The Carthaginians soon broke and the battle, and the Second Punic War, would soon be over.

16 years after his invasion of Italy, the army of Hannibal was destroyed and Carthage was defeated. As many as 20,000 men of his army were killed with an equal number taken as prisoners to be sold at slave auction. The Romans meanwhile, lost as few as 500 dead and 4,000 wounded. Scipio, having defeated the master of all strategists of the time, now stood as the world's greatest general. As a reward for his success, Publius Cornelius Scipio was awared the cognomen Africanus. Hannibal, however, managed to escapethe slaughter and returned to Hadrumetum with a small escort. He advised Carthage to accept the best terms they could and that further war against Rome, at this time, was futile.

Results of the Second Punic War

Spain was forever lost to Carthage and passed into the control of Rome for the next 7 centuries, though not without troubles of its own. Carthage was reduced to the status of a client state and lost all power of enacting its own treaties and diplomacy. It was forced to pay a tribute of 10,000 talents, all warships, save 10 were turned over to Rome along with any remaining war elephants. Carthage was also forbidden to raise an army without the permission of Rome. Grain and reparations for lost supplies also had to be provided to Rome as well as having the resposibilty of collecting runaway slaves and returning them.

Masinissa, meanwhile, as a reward for his service to Rome, was crowned King of greater Numidia, and allowed nearly free reign in his territory. He, of course, took full advantage of Carthaginian weakness and captured much territory from the city in the afermath of its defeat (probably encourage from Rome.)

Hannibal remained a constant source of fear for Rome. Despite the treaty enacted in 201 BC, Hannibal was allowed to remain free in Carthage. By 196 BC he was made a Shophet, or chief magistrate of the Carthaginian Senate. In a short time he reformed many corrupt policies within the government of Carthage and tried to strengthen its internal political system. In-fighting, however, forced Hannibal to flee to the east where he later joined up with Antiochus III of Syria to fight the Romans once more.

Scipio Africanus was at first proclaimed as a great hero, which he was. Rome had lost over 300,000 men over the course of the war, farms and other establishments in Italy were devestated. Without the leadership of Scipio in Spain, Rome may very well not had the resources to continue the fight, or Hannibal would've been reinforced making Carthaginian victory far more likely. Scipio would later serve in the east during the Macedonian Wars and against Antiochus, but would be victimized later in life by the brilliant politics of Cato the Censor.

With its victory over Carthage, and over the Macedonians in a series of wars, Rome became the master of not only all of Italy, but Africa, Spain and Greece as well. The defeat of Carthage transformed the Roman Republic from a growing regional power into the super-powered Empire of the Mediterranean.

Punic Wars and Expansion - Table of Contents

- First Punic War

- Illyrian Wars

- Conquest of Cisalpine Gaul

- Second Punic War

- First Macedonian War

- Second Macedonian War

- Syrian War

- Third Macedonian War

- Fourth Macedonian War and the Achaean War

- Third Punic War

Did you know...

Hamilcar Barca negotiated the terms of the peace that led to Carthage's withdrawal from Sicily. He then set out (237 BC) to conquer Spain as a new base against Rome and had won considerable territory when he died.

Did you know...

The first classical reference to the Allobroges is made by the Greek historian Polybius, writing sometime between 150 BC and 130 BC, and describing the crossing of the Alps by Hanibal in 218BC.

Did you know...

Gaius Flaminius was a politician and consul in the 3rd century BC. He was the greatest popular leader to challenge the authority of the Senate before the Gracchi a century later.

Did you know...

The Battle of Cannae on 2nd August 216 BC serves as a classic example of a double-envelopment maneuver, a way for an inferior force to defeat a superior force on open terrain. Hannibal is still studied in military acadamies.

Did you know...

Hanno's political popularity at Carthage rested on his domination of the North African tribesmen, from whom he exacted high taxes.

Did you know...

Cato ended every speech he made with the words "Censeo Carthaginem esse delendam - Carthage must be destroyed", regardless of what the rest of the speech was about.