Macedonia - Province of the Roman Empire (original) (raw)

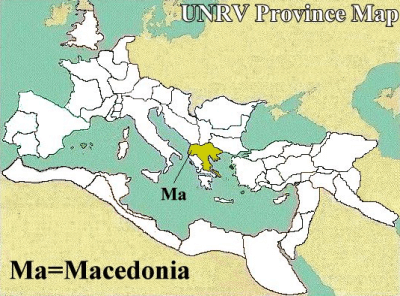

Ancient Macedonia, in stark contrast to the age of the Greek city-states, was a regional Greek (Macedonian ethnicity, not necesarily Greek) kingdom. It was located north-east of the Greek mainland and northwest of Asia Minor.

Macedonians were the Greeks who had to contend with all of the many war-like European tribes. They served as a buffer for the people who dominated the history of the ancient Greek world, like the Athenians and Spartans, and stood between the tribal Europeans and the Greek city-states.

While it left them, to some degree, independent of the politics and wars between those two rivals, the Macedonians were deeply unappreciated by their neighboring Greeks. They were looked on as no better than barbarians themselves, particularly since they had never developed or adopted the concept of the city-state, or polis, and were firmly entrenched as a kingdom.

This Kingdom was established with Aigai as the capital, some time during the 7th Century BC, upon the occupation of the central Macedonian plain. The king came to power through inheritance, but first had to be approved by the army. Serving the king was an aristocracy of nobles who had a limited amount of power. Like all monarchies that shared power with an aristocracy, however, the balance of power frequently shifted from the king to the nobles, and back again.

The political turmoil in mainland Greece to the south, between Athens and Sparta, gave rise to King Philip II. Having come to power in 359 BC, he immediately pacified their northern neighbors, captured the important gold and silver mines of Amphipolis, and began building cities and a large standing army. By 338 BC, he had conquered the southern mainland, except for Sparta, and was essentially King of all Greece. In 336 BC, plans to conquer the Persian Empire came to an abrupt end by the sword of an assassin.

Macedonian dominance of Greece could have very well collapsed it not for the succession of Philips' son, Alexander the Great. At the age of 21 he assumed his father's kingdom, confirmed his own authority and, by 334 BC, continued the plans to conquer Persia.

Asia Minor fell quickly, and with a defeat of the Persian king, Darius, in 333 BC, the conquest of the Phoenician coasts, Palestine and Egypt were secured. In 331 BC, Alexander again defeated Darius, and the whole of the Persian Empire fell under Macedonian control.

At its peak, Alexander's Empire stretched from Greece in the west, to Egypt in the south, and all the way into Mesopotamia, Scythia and India in the east. But, before he was able to establish an heir and an effective consolidation of these conquests, he fell into a fever and died in 323 BC, at the age of just 33.

With the death of Alexander, the newly-won Macedonian Empire crumbled quickly. The east was Hellenized, and its lasting effect can still be seen in the modern world, but future Macedonian kings would be limited to the control of their own Greek province thereafter.

A growing power in the west, Rome, would soon become involved in the affairs of Greece and Macedonia. The First Macedonian-Roman war occurred between 214 BC and 205 BC. This coincided with the Second Punic War, when Hannibal of Carthage and Philip V of Macedon made an alliance against Rome. The Romans, weary of war with Carthage, ended the Macedonian conflict with favorable terms to Macedon, but Roman interests were secured in Illyricum to the north.

The second Macedonian-Roman War began in 200 BC and ended in 196 BC. This war, erupting so soon after the after the first, and the exhausting Carthaginian war, was unpopular back in Rome, but the Roman Republican legions under Flaminius were veterans and well-prepared. The Greeks asked for Roman help against Macedonian incursions and Rome made an alliance against them.

They launched an attack on the armies of King Philip, who refused to guarantee to make no hostile moves against the states of Greece, and Philip V was defeated. He lost all his territories outside of Macedonia, and had to recognize the independence and autonomy or the southern Greek city-states.

The third and most decisive Macedonian-Roman war began in 171 BC and ended in 168 BC. The Romans were suspicious of the revival of Macedonian fortunes under Philip and his successor, Perseus. In 172 BC, the Romans declared war on Perseus and defeated him at Pydna (168 BC). The Antigonid dynasty was overthrown, and Macedonia was divided into four separate republics under loose Roman jurisdiction.

The fourth Macedonian War or revolt occurred between 149 and 148 BC. The Macedonians wanted a restoration of their kingdom and supported a man who pretended to be the son of the last king. The rebels overran Macedon in 150 BC and attacked southern Greece in 149 BC, but were finally crushed by the Romans in 148 BC under the Praetor Metellus Macedonicus. The Romans razed the Greek city of Corinth, one of the leading cities of the revolt, and put an end to Greek resistance under Roman rule.

It was this point, in 146 BC, that Macedonia became an official Roman province, with mainland Greece to follow shortly thereafter.

In the civil wars of the late Roman Republic, Macedonian rule was thrown into doubt again. While still under the control of the Romans, the Greek world would continue to fall back and forth under Pompey and then Caesar, and later under Antonius and Cleopatra. At the battle of Actium in 31 BC, off the shores of Epirus, Ocatavian, later to become the Roman emperor Augustus, would ensure Roman dominance of the Greek world under a single Roman leader.

During the Imperial period, when the Roman Empire was ruled by successive emperors, Macedonia was easily incorporated, and it remained a bastion of Roman/Hellenized culture as a part of the Byzantine empire until the 11th century AD.

Economy of Macedonia

The reign of Augustus began a long period of peace, prosperity and wealth for Macedonia, although its importance in the economic standing of the Roman world diminished when compared to its neighbor, Asia Minor.

The economy was greatly stimulated by the construction of the Via Egnatia road, the installation of Roman merchants in the cities, and the founding of Roman colonies. The Imperial government brought, along with its roads and administrative system, an economic boom, which benefited both the Roman ruling class and the lower classes. With vast tracts of arable land and rich pastures, the great ruling families amassed huge fortunes in the society based on slave labor.

The improvement in the living conditions of the productive classes brought about an increase in the number of artisans and craftspeople to the region. Stonemasons, miners, blacksmiths, etc. were employed in every kind of commercial activity and craft. Greek people were also widely employed as tutors, educators and doctors throughout the Roman world.

The export economy was based essentially on agriculture and livestock, while iron, copper and gold, along with such products as timber, resin, pitch, hemp, flax and fish were also exported. Another source of wealth was the country's ports, such as Dion, Pella, Thessalonika, Kassandreia, and Neapolis.

Tribes of Macedonia

Archeological finds and historic evidence show that the first Hellenic-speaking tribes settled in the area of Northern Pindos in 2200 - 2100 BC. During the following centuries, various groups of these tribes - the Ionians, Achaians, and Minyes etc. - moved to the south, while some of the Macedni tribe moved to Sterea Hellas and Peloponnesus, and others settled in today's west, south and central Macedonia. These tribes spoke the Hellenic language, with a local dialect.

There were three basic groups of Greek-speaking peoples in Macedonia: The Ionians in the NW part of Thessaly, the Arcadians and Aeolian in eastern Macedonia and the Macedni in the west from which the region takes its name.

The Dorians were a split group from the Macedni and moved south into Macedonia and east into Asia Minor.

By the late 2nd century AD, all of these tribes would have been considered "Greek" by the Romans, and little to no distinction would have been made in tribal status.

There were also several large colonies of Jewish settlers, as well as a great many Romans scattered throughout the region. These Roman settlers were eventually Hellenized and absorbed into Greek culture with the transfer of Roman power to Byzantium in the 4th Century AD.

There has been a great deal of debate on whether or not the Macedonian people were actually Greek, as opposed to just Hellenized northern neighbors of varying European tribal descent. Certainly, there were influences of other tribes, based on their proximity, that the Achean people didn't have, but this doesn't fully support the argument that they were completely separate people.

They may have been related through the Dorians, or there may be other influences and origins from migrating tribes. The Macedonians, however, were certainly completely Hellenized by the time of Alexander, but the debate of ethnicity will rage on.

Did you know...

The name Macedonia derives from the Ancient Greek word "makos" which is the Doric form of "mekos" meaning "length" or "height" and "makedos" or "makednos" which is a term for a tall man. Legend says that the ancient Macedonians were so tall that if they fell they could not stand up without help.