Distant Writing - What the Companies Charged (original) (raw)

10. WHAT THE COMPANIES CHARGED

The message pricing policy of the several public telegraph companies was extraordinarily complex and only gradually simplified with the advent of competition and eventual consolidation. It was not until 1862 that a flat rate that charged a domestic message irrespective of distance was introduced – and as this proved consistently unprofitable, to be soon abandoned.

The currency used here is the pound sterling, the '£' or 'L', then divided into twenty shillings, the 's', each of twelve pence, the 'd'. So the pound equalled 240 pence. Average individual male earnings in this period were about £24 per year.

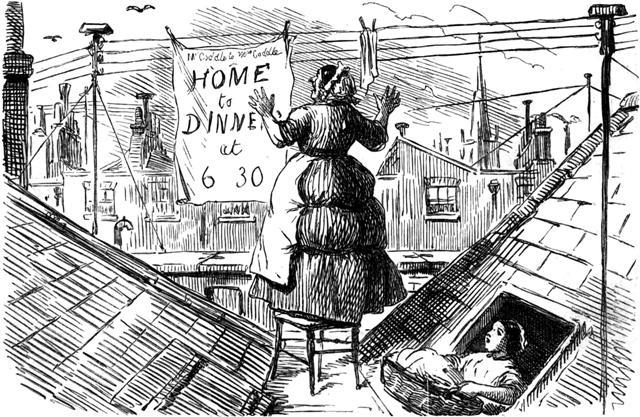

"Social Messaging" 1862

This became possible with the cheapest of all rates introduced by the

London District Telegraph Company in 1861

a.] Pricing Context

If the pricing policies of the telegraph companies were to appear high and of Byzantine complexity then they must be viewed against the only competitive mode of communication, the letter service of the General Post Office.

Just as the electric telegraph was being introduced during the 1840s the postal system was undergoing revolutionary change from its role in generating revenue for the British government into a market-driven service provider. Under the pre-1840 system, in as much as it can be calculated, for its published accounts were vague in extreme, the Post Office had a profit margin of 68% of income over working expenses; this produced an impressive 3% of the British government's revenues.

It achieved this through a wholly arbitrary and remarkably convoluted pricing policy for its primary task, the delivery of letters.

| Postage Rates for a Letter 1839 |

|---|

| Up to 15 miles 2d16 to 20 miles 2½d21 to 30 miles 3d31 to 50 miles 3½d51 to 80 miles 4d81to 120 miles 4½d121 to 170 miles 5d171 to 230 miles 5½d231 to 300 miles 6d301 to 400 miles 6½d401 to 500 miles 7d |

The base letter price was for a single sheet of paper of a defined size; folded up and sealed for privacy (no envelopes were permitted). All letters were charged by the number of the sheets in them. The distance charges were based on actual road mileage, so letters between two adjacent towns that had to go by way of London or other large cities faced increased charges. In most towns, addressees had to collect letters at post offices; local delivery, in those towns that offered it, incurred additional charges. Postal charges were paid by recipients, and, where local delivery existed, letter-carriers often had to come several times to collect the fees.

The cost of sending a single sheet letter from London in England to Edinburgh in Scotland in the 1830s was 1s 1½d, and it took forty-eight hours to be delivered.

The Post Office reform of 1840 introduced the flat rate charge of 1d for any distance, pre-paid, and the postage receipt label or stamp. Letters were delivered by the letter carriers at everyone's door; but they still had to be handed in at Post Offices for mailing. Post boxes into which stamped letters could be dropped for carriage were also introduced, but not until March 1855.

It was from this historic context of long-standing, along with the new postal regime that came in during 1840, that the contemporary public, that is the educated, writing public, made comparisons with on the pricing of the public telegraphs.

b.] The Earliest Telegraph Pricing

Before the Electric Telegraph Company established something approaching a national system in 1848 several railway companies offered public messaging.

The Great Western Railways' pioneer short line from Paddington in London to Slough originally charged a flat rate of 1s 0d for any length of message in 1843. By 1846 this had become 2s 0d for a message not exceeding twenty words, with 6d for every subsequent ten words. Answers under ten words were free, answers over ten words were half-rate. Entry to the stations to look at the instruments was 1s 0d throughout this early period.

The London & South-Western Railway adopted a completely different tariff in 1846: ignoring distance, it was based entirely on message length. The cost between any two stations on their line from Nine Elms in London to Southampton and Portsmouth was:

| | Message | Answer | | | ------------------------------------------------------ | -------- | ----- | | Under 20 words | 3s 0d | 2s 0d | | 20 to 30 words | 4s 6d | 3s 6d | | 40 to 60 words | 6s 0d | 5s 0d | | 60 to 80 words | 7s 6d | 6s 6d | | 80 to 100 words | 9s 0d | 8s 0d | | Spectators wishing to view the instruments paid 1s 0d. | | |

The South Eastern Railway worked the telegraph between London and Dover and over all its branches in 1846. It then charged the following public message rate for up to twenty words from its London Bridge terminus: to Tunbridge 5s 0d, Tonbridge Wells 6s 0d, Folkestone 10s 6d, Dover 11s 0d, Canterbury 10s 6d and to Ramsgate 12s 6d. From twenty to forty words were charged double and from forty to sixty words treble the above rate. The public were not allowed in the South-Eastern's instrument rooms.

As the only railway company retaining control of its circuits after the formation of the Electric Telegraph Company the South Eastern consistently kept a high tariff. On November 17, 1851 the railway grudgingly introduced a flat rate of 5s 0d for a twenty word message and 3d a word, over its entire system, but its rates did include an answer in the original cost.

The Eastern Counties Railway advertised a public message tariff between all of its stations in 1846; for up to thirty words from London to Colchester the cost was 3s 6d, to Cambridge 3s 6d, to Ipswich 5s 6d, to Norwich 7s 6d and to Yarmouth 9s 6d. Thirty word messages to the suburban stations in London from its Shoreditch terminus were 2s 0d. A flat rate of 1s 0d for every subsequent ten words and 1s 0d a mile for delivery was charged.

The Midland Railway in December 1846 worked the telegraph for public messages between the towns of Leeds, Normanton, Sheffield, Derby, Rugby, Tamworth, Birmingham, Nottingham, Newark and Lincoln.

The charge made by the Midland for under ten words was 1d a mile; above ten words and under twenty, 1½d a mile; above twenty words and under thirty, 3d a mile; and for every additional ten words ½d a mile; messengers to deliver the message from any station on foot would be charged at 1s 0d, or by post-chaise at cost. In the case of any message failing through the defect of the instrument or neglect of the railway company's servants the money would be refunded. Messages regarding lost luggage on the railway were sent free-of-charge. This tariff ended in 1848.

c.] Telegraph Company Message Pricing From its inception the Electric company used a message length of twenty words for publicising its pricing. The cost of a twenty-word message became the industry norm for determining prices. As well as "words" all numbers and punctuation had to be spelt out. Additions such as underlining, italic text, parenthesis and inverted commas were charged as two words. At this period the delivery of the message within one-half mile of the receiving office was free, but the words in both the sender's and recipient's addresses were charged for. There was also then a minimum charge.

Between 1848, when the major English and Scottish cities were first in circuit, and March 1850 the Electric company charged 1d a mile for twenty words for the first fifty miles (i.e. 4s 2d), ½d a mile for the second fifty miles (i.e. 6s 3d) and ¼d a mile for distances beyond. Half-rate was charged for each additional ten words or fraction thereof. Actual examples of the confusing basic tariff for a twenty-word telegraphic message from London, in place from January 1, 1848 until March 1850, were:

Southampton..........5s 6d

Yarmouth...............7s 0d

Birmingham............6s 6d

Manchester.............8s 6d

Liverpool................8s 6d

Berwick...................12s 0d

Bristol.....................13s 0d

Glasgow...................14s 0d

Edinburgh...............16s 0d

The maximum charge for twenty words over any distance was fixed at 10s 0d in March 1850; this was reduced to 8s 6d in March 1851, when a "simplified" charge of 3d a word for over twenty words or half-rate for ten words was also introduced.

For important messages Repetition was recommended; for a further half-rate charge on the message cost it would be transmitted back to the sender by the receiving office to ensure accuracy.

There was an extra charge on top of repetition for Insured Messages. This applied to communications that had monetary value, mercantile buying and selling orders, for example. In 1848 for a premium of 12½ per cent the Electric Telegraph Company would be responsible for losses due to errors in transmission for sums up to £1,000. The maximum premium was 2s 6d which applied to liabilities of £1,000 and over. The premium had reduced to 10% of the liability by 1860 but this was payable with no upper limit.

The Magnetic and United Kingdom companies both had a limit for compensation of £5 for errors in repeated messages, but they charged only a 1% premium for their Insured Messages. In any case, repetition was rarely, and insurance almost never used by the message sending public.

All of the Special Acts authorising the companies had clauses indemnifying them from damages caused by errors in transmission of ordinary public messages. Repetition and Insurance as premium services were there to justify this legal indemnity. Although tested in the Courts the companies were never to be found liable for errors. Public messages with any sort of error were said, in 1853, to be one in every 2,400 sent, which was thought acceptable.

For a single charge of 2s 6d travellers could book carriages, post-horses, refreshments, beds or other accommodations at all towns where the Company had a telegraph station. Lost luggage could also be sought for the same flat-rate.

In the Company's early years, until about 1850 or 1851, before public knowledge and confidence was established, the majority of its messages out of London consisted of bulk news and commercial information carried by contract at a discounted rate, set by negotiation, or for its own subscription news-rooms.

In July 1853 the Electric Telegraph Company re-introduced a 1s 0d message rate for twenty words between its branch offices in London, first used in 1850. They now totalled eighteen: the railway stations at Euston Square, King’s Cross, Shoreditch, Fenchurch Street, London Bridge, Waterloo Bridge, Paddington, Blackwall and Highbury; and 43 Mincing Lane; the General Post Office; 30 Fleet Street; 448 West Strand; 17a Great George Street; 89 St. James's Street; 1 Parkside, Knightsbridge; 6 Edgware Road; and London Docks. It now also offered a promotional message rate between its metropolitan offices of 4d for a message of ten words at the same time; but this was not continued.

The message rate to and from the London branches and the provinces was the same as for Founders' Court.

In November 1853, as competition began to be felt, the overall pricing structure was again slightly simplified – the charge for a twenty word message under 50 miles became 1s 0d, under 100 miles became 2s 6d, beyond 100 miles it cost 5s 0d. The 3d a word charge for more than twenty words and the half-rate for ten words ad-ditional was continued.

Commencing in June 1854, as a further concession, but only in response to competition, the words in the addresses of sender and recipient were sent free-of-charge. At the same time the Electric offered Special Rates for twenty words where the competition was strongest. The 112 miles between London and Birmingham were charged at 1s 0d; and the 210 miles to Liverpool, the 180 miles to Manchester and the 309 miles to Carlisle at 2s 6d. The average message length then was calculated at twenty-three words, of which seven represented the sender's and recipient's addresses.

During August 1855 the Magnetic and British Telegraph companies both agreed a joint rate structure with the Electric company.

For the four-and-a-half-years between July 1855 and January 1860 the cost of a twenty word message on the Electric's circuits, with addresses "free", was 1s 0d within London, 1s 6d within 50 miles, 2s 0d within 100 miles, 3s 0d within 150 miles, 4s 0d over 150 miles and 5s 0d to Dublin in Ireland. The rate within 200 miles was reduced in 1860 to 2s 6d from 4s 0d.

Delivery of the message by messenger on foot, termed at the time porterage, was free-of-charge under a half-mile from the receiving office; from a half to one mile it was 6d, from one to two miles 1s 0d and from two to three miles 1s 6d. Delivery "express" by horse-cab was also free under a half-mile; from a half to one mile it was 1s 0d, from one to two miles 2s 0d and from two to three miles 3s 0d.

In 1853 the British Electric Telegraph Company had the following rates for a twenty word message throughout its 42 station network in the north of England and the west of Scotland: under 30 miles 1s 0d, under 100 miles 2s 6d and over 100 miles 5s 0d. The 5s 0d rate applied only to messages to its disconnected station in London, forwarded over the wires of the "old" Electric Telegraph Company. The British company, unlike the Electric company, also levied an additional 6d fee for delivering each message. However, it also marketed a 1s 0d for twenty word rate between six pairs of large cities in its catchment area.

The European Telegraph Company, in concert with the Submarine company, announced the opening of its new line from London to Birmingham on August 13, 1853. Messages between the two cities were advertised at 1s 0d for twenty words, 6d for additional ten words or less. However porterage (delivery) was charged at 6d for the first half mile and six pence a mile beyond that. Messages for the Continent of Europe could be forwarded by post from Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham, saving 1s 6d.

This line superseded the need to transfer messages to the Continent from the Electric’s office to the Submarine company’s office in London. Messages “will proceed directly thorough one set of instruments, errors of frequent copying will be obviated, the messages will remain under one management, and all delay between Lothbury and Cornhill will be avoided.”

On the same day the Electric Telegraph Company announced that from August 15, 1853 their message rate to Birmingham, and other places within 50 miles of London, would be 1s 0d for twenty words, with no charge for porterage within half-a-mile. It also listed its fifteen offices in the capital from which the rate applied.

The English & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company introduced a reduced tariff in May 30, 1854 between London, Liverpool, Manchester and Carlisle at 2s 6d for twenty words; and for Birmingham to London, Liverpool or Manchester, and vice versa, at 1s 0d. Direct connections were also promoted to Scotland, and Belfast, Dublin, Galway, Cork and Queenstown in Ireland.

The opening of the "Submarine & European Telegraph", the united trading title of these companies, was advertised in Liverpool on May 12, 1854 with a cost for twenty words to London of 2s 6d (previously 5s 0d), Manchester 1s 0d and Birmingham 1s 0d (formerly 2s 6d, an additional ten words now 6d originally 1s 3d). There was no charge for name and address, or porterage for the first mile. The Electric company promptly matched these rates.

The "Submarine & European Telegraph" also promoted much simplified city-to-city rates with just two tariffs for twenty words, either 1s 0d or 2s 6d. But it possessed only a very limited number of public offices: in London at 30 Cornhill, City, 43 Regent Circus, West End, and the House of Commons, as well as in Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Gravesend, Chatham, Canterbury, Dover and Deal.

The European, British and Magnetic companies, singly and as merged, understandably offered message rates broadly comparable to the Electric company's; and just as complex; although it was through their competitive influence that the Electric company gradually reduced its rates throughout the 1850s.

d.] The Price Cartel 1855

Once the European company opened its circuit to Liverpool on May 10, 1854 it began a vicious price war with the Electric Telegraph Company. The cost of a twenty word message to London was reduced from 5s 0d to 2s 6d, and messages between Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham, previously 2s 6d, were reduced to 1s 0d. On its merger with the British company this combative policy was extended: messages from London to Leeds and Hull, formerly 5s 0d, were now charged at 2s 6d, with reductions of from 25% to 40% for distant stations such as Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Glasgow.

In July 1854 the new British Telegraph Company, the combined British and European firms, charged the following national message rates for twenty words: under 50 miles 1s 0d, under 100 miles 2s 0d, under 200 miles 2s 6d, under 300 miles 3s 0d, over 300 miles 4s 0d, with no charge for address of sender or recipient, with no charge for porterage under one mile, where messengers were kept, otherwise 1s 0d a mile was charged outside a one-mile radius; and 3d a word extra, or one-half the above rates for any number not exceeding ten words.

The British company's rate in 1855 from London to Belfast was 7s 0d; Birmingham 1s 0d, Glasgow 4s 0d, Greenock 4s 0d, Hull 2s 6d, Leeds 2s 6d, Liverpool 2s 6d, Manchester 2s 6d and Newcastle 3s 0d.

The effect of this discounting was disastrous. The British company was forced to suspend its half-yearly dividend for July 1855. On August 31, 1855 the British Telegraph Company, the English & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company and the Electric Telegraph Company ended price competition and adopted a common message tariff for Great Britain and Ireland.

On its inception by merger in 1857 the British & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company adopted the same message charges as the Electric company had fixed in June 1855. The only exceptions to this were for messages to Ireland, where the Electric had only a limited presence; 5s 0d for twenty words to most of its 83 stations there and 6s 0d to the remote Atlantic coast towns.

The South Eastern Railway Company, with its independent telegraph, reduced its messages rates considerably from January 1, 1856 to something approaching those of the telegraph companies. The rate for twenty words on its own system became 1s 0d within 25 miles, 1s 6d between 25 and 50 miles, and 2s 0d over 50 miles, with a surcharge of 1s 0d applied to messages sent on Sunday. Delivery was free within a half mile, as were names and addresses. The telegraph company rates were applied in addition for messages to the rest of the world. The railway charged four words in code as twenty words!

Eventually, by the mid-1860s, the South Eastern Railway adopted a flat rate charge of 1s 0d for a twenty word message between any of the stations on its own system, and 6d for every extra ten words or part of ten words. Addresses and delivery remained free and the extra charges still applied.

In January 1861, the Electric company adopted a 6d rate for twenty words for all messages between its London stations to combat the new London District Telegraph Company that offered fifteen words for 6d.

The United Kingdom company introduced the flat rate of one shilling for a twenty-word message throughout its system; its rates were 1s 0d for the first twenty words and 3d for each additional five words or part of five words irrespective of distance; with the options of repetition and insurance of messages. It commenced working message traffic in 1861 and from November 1861 the other companies adopted these rates wherever the United Kingdom company opened competing offices. The original shilling rate did not include delivery but by 1862 porterage under a mile was free.

This rate was never remunerative and effective price competition lasted four years, 1861 until 1865.

In the face of flat rate competition in February 1862 the Electric and Magnetic adopted a new common tariff. The charge for messages to any part of Great Britain, not exceeding twenty words, was: within 25 miles, 1s 0d; within 50 miles, 1s 6d; within 100 miles, 2s 0d; within 200 miles, 2s 6d; within 300 miles, 3s 0d; within 400 miles, 4s 0d. Special exceptions were made in the cases of Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham (i.e. where the United Kingdom company had offices): the charge to these places being 1s 0d per 20 words. For messages of twenty words to distant cities in Ireland: Queenstown, Galway, and Londonderry, 6s 0d; to all other Irish stations, 5s 0d for 20 words (Seven words were allowed in addresses without charge).

Delivery of a message over the first free half-mile incurred an escalating range of fees. By foot messenger a distance of 1 mile added 6d, 2 miles 1s 0d, and 3 miles 1s 6d extra. By Express messenger, fly (hired coach), cab, horse or rail 1s 0d a mile was charged. For forwarding a message by post 1d was added, and by railway parcel in Britain or by road coach in Ireland, 1s 0d.

Messages sent on Sundays were charged 1s 0d extra.

Within Ireland in 1862 the Magnetic company offered similar zone tariffs: 1s 0d, 1s 6d and 2s 0d with a maximum of 2s 6d for twenty words. The Electric company then had, in addition to its cable to Dublin, only a handful of stations in the south, based around Cork, Waterford and Wexford; between which it charged 1s 0d and 2s 0d, with a cheap-rate 6d tariff from Cork to its suburb of Queenstown, copying that of the Magnetic company. It charged 2s 6d for messages to Dublin, the same as the Magnetic, but sent them via England by its South-of-Ireland and Holyhead cables. Both companies then charged a flat-rate of 5s 0d for twenty word messages from Ireland to all of their English stations.

In March 1864 the rate for twenty words from London to Scottish stations was reduced to 3s 0d. Later in that year, in August, the common tariff of the Electric and the Magnetic was reduced and simplified further: for 50 miles or less, 1s 0d; for 100 miles or less 2s 0d; for 200 miles, 2s 6d, and for 300 miles, 3s 0d. The exceptions for London (6d), the stations competitive with the United Kingdom company (1s) and Irish stations remained.

On September 9, 1858, and for several years subsequently, the Channel Islands Telegraph Company and the Electric Telegraph Company charged 3s 0d for twenty words from the islands to Weymouth, where the English cable landed, 4s 0d to Southampton, 5s 0d to London, and 5s 8d to Liverpool, Manchester and Glasgow, and the same costs in reverse, using the country's longest domestic cable. Messages between the islands of Jersey, Guernsey and Alderney were 1s 0d. If sent to England via Paris and the Submarine company's circuits, the charge was 11s 6d, reduced in 1862 to 7s 6d. By 1868 this had become 6s 8d to and from London, and 7s 8d to and from British provincial stations. The Isle of Man Telegraph Company and the Electric Telegraph Company latterly charged 4s 6d for twenty words between stations on the island and all stations on the British mainland.

The Electric Telegraph Company's

Average Message Cost

1850 13s 11¾ d

1852 6s 3½ d

1855 4s 1¾ d

1861 3s 9¼ d

1868 2s 0¾ d

In Ireland the British & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company offered a promotional rate of 6d for a ten word message on its suburban circuits from Dublin to Kingstown and Cork to Queenstown in 1858. This led to:

The exception to the twenty-word standard was to be that initially adopted by the London District company having a uniform 4d rate for its fifteen word messages within London, including delivery. In 1861 it increased this to 6d. So the basic charge for fifteen words was 6d; for fifteen words each in message and a reply it was 9d; for twenty words, 9d, each delivered, without extra charge, within half-a-mile of a station. Repetition back to the sender for accuracy was an extra half-rate.

Cynical newspapers claimed its lady clerks in London merely re-wrote a received message on a delivery form, paying boys a penny to take it to the recipient.

The District offered tradesmen the opportunity to have customers place orders by telegraph free-of-charge. The tradesman paying twenty shillings for a package of one hundred messages for this service. It also gave substantial rebates at the year end on business accounts to secure frequent users in commerce and trade.

It launched a similar generous offer for the general public in 1862; one hundred 6d stamps for just one pound, continuing it until 1866, effectively offering a message rate of 2½d for fifteen words within London, approaching the Post Office letter fee of 1d. This was the cheapest rate for a telegraph message ever offered in Britain. It permitted for the first time "social messaging" on a wholly personal level, in that trivial domestic matters might be communicated relatively cheaply.

However, even with its basic 6d rate and its 2½d discounted rate for fifteen words, the Company's average message cost during the year 1864 was 7½d.

In 1866, unable to raise the capital needed to repair massive weather damage to its over-house circuits, the London District company temporarily raised its tariff from 6d to 1s 0d for fifteen words. The sixpenny rate was restored for a year but was finally abandoned in May 1867 when its financial state forced it to adopt a rate of 1s 0d for twenty words, double that charged by the other companies between their London stations.

Cipher – For messages rendered in apparently random numeric or letter cipher rather than code which substituted dictionary words for phrases the Companies charged each letter as a word. This was necessary due to the extreme difficulty and slowness in truly accurate transmission of such messages. The rate applied to both the Private Keys used by individuals and to the Cryptograph messages sent by the government and police.>

The Twenty-Word Message - By the 1860s it was established that the address of the sender consisted, on average, of four words and the address of the receiver occupied eight words. With no less than fourteen words required for the companies' accompanying service instructions by the operators, and with seventeen, the average number of words sent by the public, the total number of words transmitted for each "twenty-word" message was actually forty-three.

e.] The Last Tariff Ending all competition in July 1865 the three national telegraph companies, the Electric, the Magnetic and the United Kingdom, agreed to consolidate their tariffs at 6d for twenty words within London, 1s 0d within 100 miles, 1s 6d within 200 miles and 2s 0d beyond 200 miles, including delivery within a half mile. This lasted until the companies ceased working in February 1870.

There were, however, "extras" to this tariff. The most irritating to the public was that there was no 'through rate' to cover messages transferred from one company's system to another. For such each company charged its segment as a separate transaction. "Thus the charge for a message from Southampton to Accrington would have been 2s 0d for transmission from Southampton to Manchester by the Electric company, and 1s 0d for transmission from Manchester to Accrington by the Magnetic company." By 1868 there were, it is claimed, up to twenty-five telegraph service providers, railway companies and independent telegraphs, that were not part of the national agreement and were entitled to add their own charge to the common rate, usually 6d or 1s 0d. At the Electric company's 350 auxiliary stations on railways which did not customarily handle public messages, the railway station-master was entitled to 6d over the usual rate for providing the service. The domestic cable companies serving the offshore islands all charged a special rate to compensate for their risk.

In balance to this there was a general introduction of a 6d rate for twenty words for messages within the country's largest cities as well as London. This district rate applied to Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds and Edinburgh, among other places.

In 1866 in Ireland, where the Electric company was the competitive interloper, there was a common message tariff broadly similar to that in Britain; twenty words for 6d within Dublin, Belfast and Cork, 1s 0d for up to 50 miles, 1s 6d for up to 100 miles, 2s 0d for up to 200 miles and 2s 6d for other stations. There was a preferential 1s 0d for twenty words rate from all those places where the Electric company's recently opened canal-side circuits worked to Belfast. Above twenty words the sender had the option of half-rate for every ten words or less, or ¾ d a word extra. Ten words were allowed free for the addresses of sender and recipient. A surcharge of 1s 0d was made for any message sent on Sunday. Delivery was as in Britain, free up to half-a-mile, then 6d for every half-mile, 1s 0d per mile for horse or express delivery.

The price-fixing by the major companies was driven by the growing lobby for state intervention.

In comparison, the basic message rate in France, Belgium and Switzerland during the 1860s was one franc, say 10d, for fifteen words, which had to include the addresses, over one zone of about 50 miles. Only four compact countries, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands and Switzerland were to introduce a national flat rate. All continental countries charged for the addresses of the recipient and sender. Because of the lack of free addresses and the close zone tariff most messages were far more expensive than in Britain.

As has been stated previously mailing a Post Office letter addressed to anywhere in the three kingdoms cost just 1d, the speed of delivery varying by distance. In London there were twelve collections and deliveries of letters per day; in most country towns six a day.