Nat Lofthouse (original) (raw)

Nathaniel Lofthouse, the youngest of four sons, was born in Bolton on 27th August 1925. His father was the head horsekeeper for Bolton Corporation. A talented centre-forward, he was selected to play for Bolton Schools against Bury Schools. Bolton won 7-1 and Lofthouse scored all seven.

In 1939 Charles Foweraker, the manager of Bolton Wanderers, signed the 14 year-old Lofthouse as an amateur. On 22nd March 1941, George Hunt, the club's leading scorer for the last two seasons, was moved to inside-right and replaced at centre-forward by the 15 year-old Lofthouse. Bolton won the game 5-1 with Lofthouse scoring two of the goals.

In his autobiography, Goals Galore, Lofthouse argued that George Hunt was the most important influence on him during this period of his career: "I would have an hour or two off to receive coaching from George Hunt, and firmly believe that these private coaching sessions played a big part in my advancement. George Hunt, who was a very great centre-forward himself, possesses the rare ability to pass on to youngsters his own deep knowledge of the game. When George is explaining points, it is easy to see why he was such a magnificent footballer. Out on the pitch at Burnden Park I learnt more from George in an hour than I could from most people in a year."

Most of the Bolton Wanderers players had joined the 53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment in 1939 on the outbreak of the Second World War, but between July 1940 and the whole of 1941 they were based in various army camps around Britain. This enabled them to play the occasional game for Bolton Wanderers in the North-East League. During this period the Bolton squad included Harry Hubbick, Jack Atkinson, George Hunt, Danny Winter, Billy Ithell, Harry Goslin, Walter Sidebottom, Albert Geldard, Tommy Sinclair, Don Howe, Ray Westwood, Ernie Forrest, Jackie Roberts, Jack Hurst and Stan Hanson.

On 22nd March 1941, George Hunt, the club's leading scorer for the last two seasons, was moved to right-half and replaced at centre-forward by the 15 year-old Lofthouse. Bolton won the game 5-1 with Lofthouse scoring two of the goals. Lofthouse immediately formed a good relationship with his inside-forward, Walter Sidebottom. In the first six games together they scored 10 goals between them.

Nat Lofthouse as a Bevin Boy

In the 1941-42 season Lofthouse ended up the club's top scorer when he managed 9 goals in 25 games. He continued to score on a regular basis but in 1943 he became a Bevin Boy and worked as a miner in a local colliery. As Dean Hayes points out in his book, Bolton Wanderers (1999): "Bevin Boy Lofthouse's Saturdays went like this: up at 3.30 a.m., catching the 4.30 tram to work; eight hours down the pit pushing tubs; collected by the team coach; playing for Bolton. But work down the mine toughened him physically and the caustic humour of his fellow miners made sure he never became arrogant about his success on the field."

In the first round of the 1945 Football League War Cup (North) Bolton beat Accrington Stanley 4-1 with Nat Lofthouse scoring two of the goals. Lofthouse went on to score a hat-trick against Blackpool. This was followed by victories over Newcastle United and Wolverhampton Wanderers to reach the final against Manchester United. Over two legs Bolton won 3-2. On 2nd June 1945, Bolton beat Chelsea 2-1 in the Cup Winners Cup.

In the 1945-46 season Bolton finished in 3rd place in the North League 1945-46 season. Lofthouse scored 21 goals in 34 games. Other scorers included Willie Moir (9), Malcolm Barras (7) and George Hunt (6). One journalist claimed that Lofthouse "was the epitome of the old-fashioned English centre-forward; seemingly hewn from oak."

On 9th March 1946 Bolton Wanderers played Stoke City in a FA Cup tie. Over 80,000 people entered the Burnden Park ground before the club closed the gates. Some locked out fans decided to climb over the walls in order to see the game. Hundreds of spectators were pushed down a barrier-less section of the embankment under the weight of the crowd. A police officer walked onto the pitch towards the referee. He blew his whistle to stop the game and Lofthouse saw the officer point towards the bodies lying motionless at the edge of the pitch saying: "I believe those people over there are dead." Thirty-three people died and over 400 were injured in the disaster.

Lofthouse married Alma Foster in 1947. He remained in good form after the war. In the 1946-7 season he was top scorer with 18 goals. He hit another 18 in the 1947-48 season. Willie Moir was top scorer in the 1948-49 season but Lofthouse got the title back in 1950-51 (21), 1951-52 (18) and 1952-53 (22).

This excellent form won him his first international cap for England against Yugoslavia on 22nd November, 1950. He scored both goals in the 2-2 draw. He described the goals in his autobiography, Goals Galore: "Hancocks, who kept bobbing up in the most unexpected places, pushed the ball inside to Mannion. As if on a piece of string it went on to Baily, who hit a first-time accurate pass high over the head of right-back Stankovic. Medley, running on to it, rammed the ball over to me. All I had to do was side-foot it into the net for my first goal for England. Four minutes later England scored a second goal-and again Medley was the architect, placing the ball so accurately in the goalmouth that all I had to do was nod my head and the ball was nestling snugly in the back of the net."

In 1951 he played against Wales (1-1), Northern Ireland (2-0) and Austria (2-2). He remained a regular in the team for the next six years. The team at this time included Tom Finney, Neil Franklin, Harry Johnston, Tommy Lawton, Stanley Matthews, Malcolm Barras, Wilf Mannion, Stan Mortensen, Bill Perry and Billy Wright.

In the 1952-53 season Bolton Wanderers beat Notts County (1-0), Luton Town (1-0), Gateshead (1-0) and Everton (4-3) to reach the FA Cup final. Lofthouse had scored in every round of the cup. Bolton's opponents, Blackpool, was managed by Joe Smith, the hero of their 1923 FA Cup victory.

Nat Lofthouse scored a goal in the 2nd minute. Cyril Robinson, the Blackpool defender, was later interviewed about the match: "We kicked off and within a couple of minutes we had a goal scored against us. That's about the worst thing that could happen. Gradually we got some passes together, got Stan Matthews on the ball and Mortensen got the equaliser, but they went back ahead straight away." The Bolton scorer was Willie Moir.

Stanley Matthews wrote in his autobiography that: "At half-time we sipped our tea and listened to Joe. He wasn't panicking. He didn't rant and rave and he didn't berate anyone. He simply told us to keep playing our normal game." Harry Johnson, the captain, told the defence to "be more compact and tighter as a unit." He also added: "Eddie (Shinwell), Tommy (Garrett), Cyril (Robinson) and me, we will deal with the rough and tumble and win the ball. You lot who can play, do your bit."

Despite the team-talk Bolton Wanderers took a 3-1 lead early in the second-half. Robinson commented: "It looked hopeless then, I was thinking to myself at least I've been to Wembley." Then Stan Mortensen scored from a Stanley Matthews cross. According to Matthews: "although under pressure from two Bolton defenders who contrived to whack him from either side as he slid in, his determination was total and he managed to toe poke the ball off the inside of the post and into the net."

In the 88th minute a Bolton defender conceded a free kick some 20 yards from goal. Stan Mortensen took the kick and according to Robinson: "I've never seen one taken as well. It flew, you couldn't see the ball on the way to the net." Matthews added that "such was the power and accuracy behind Morty's effort, Hanson in the Bolton goal hardly moved a muscle."

The score was now 3-3 and the game was expected to go into extra-time. In his autobiography, Stanley Matthews described what happened next: "A minute of injury time remained... Ernie Taylor, who had not stopped running throughout the match, picked up a long throw from George Farm, rounded Langton and, as he had done like clockwork through the second half, found me wide on the right. I took off for what I knew would be one final run to the byline. Three Bolton players closed in, I jinked past Ralph Banks and out of the corner of my eye noticed Barrass coming in quick for the kill. They had forced me to the line and it was pure instinct that I pulled the ball back to where experience told me Morty would be. In making the cross I slipped on the greasy turf and, as I fell, my heart and hopes fell also. I looked across and saw that Morty, far from being where I expected him to be, had peeled away to the far post. We could read each other like books. For five years we'd had this understanding. He knew exactly where I d put the ball. Now, in this game of all games, he wasn't there. This was our last chance, what on earth was he doing? Racing up from deep into the space was Bill Perry."

Stanley Matthews added that Perry "coolly and calmly stroked the ball wide of Hanson and Johnny Ball on the goalline and into the corner of the net." Bill Perry admitted: "I had to hook it a bit. Morty said he left it to me, but that's not true, it was out of his reach." Blackpool had beaten Bolton Wanderers 4-3. Matthews, now aged 38, had won his first cup-winners medal.

That season Lofthouse scored six goals for the Football League in a match against their Irish League. He also scored 22 Football League goals and in 1953 the Football Writers' Association (FWA) awarded Nat Lofthouse the first Footballer of the Year Award.

Bolton Wanderers continued to struggle in the First Division but Lofthouse remained in good form and was the club's top scorer in 1954-55 (15), 1955-56 (32), 1956-57 (28) and 1957-58 (17). Bolton also enjoyed a good FA Cup run that season beating York City (3-0), Stoke City (3-1), Wolverhampton Wanderers (2-1), Blackburn Rovers (2-1) to reach the final against Manchester United. Lofthouse scored both goals in the 2-0 victory.

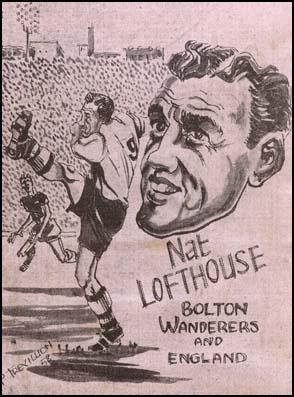

Nat Lofthouse by Paul Trevillion (1958)

Although still a regular goalscorer Lofthouse, like Stanley Matthews, and was not selected for the 1958 World Cup. The football historian, Brian Glanville, has speculated: "Perhaps his style was a little too traditional for the England selectors and the team manager, Walter Winterbottom." Lofthouse won his last international cap for England against Wales in 1958. The game ended in a 2-2 draw. Lofthouse had the excellent record of scoring 30 goals in 33 games.

Lofthouse had a series on injuries and in 1960 decided to retire from the game. He had scored 285 goals in 452 league and cup appearances for Bolton Wanderers. He ran a public house in Bolton but in July 1961 he was appointed chief coach of the club in 1967. The following year he became manager but he was not a success and he became chief scout instead.

Alma Lofthouse died in 1985. The following year he became president of Bolton Wanderers and in January 1994 he was awarded the OBE. Three years later the club decided to name their East Stand at their new Reebok Stadium after him.

Nat Lofthouse died in a Bolton nursing home on 15th January 2011.

Primary Sources

(1) Nat Lofthouse, Goals Galore (1954)

My early schooldays may seem unimportant to the reader, but to me they were the most formative of my life. I discovered it was impossible to learn all there was to know about football. Modesty, and the putting of team before self was always stressed. The old maxim that practice makes perfect was constantly hammered into us by a schoolmaster to whom I shall always be heavily in debt.

One of our biggest supporters was Mr. Bert Cole, a forty-year-old sportsman who got a great kick out of helping schoolboy footballers to make the grade. He told me he thought I might develop into a useful header of a football, and with the permission of my father-who by now was head horsekeeper for Bolton Corporation-he used to come to our house on a Sunday morning and encourage me to head a football correctly. More often than not I practised heading a ball against the wall of the stables which adjoined our house, and this form of practice was the basis of the heading technique I later developed with Bolton.

Progress in football is made slowly but surely, and when I did eventually secure my place in the Bolton Schools XI I knew I would be able to hold my own. Mr. Cole, my mentor, was equally thrilled by my honour and promised me a new bike if I scored a hat-trick in my debut, which, incidentally, was against Bury Town. I thought he might be pulling my leg but I was determined to succeed just the same.

Well, I succeeded beyond my wildest dreams. We beat Bury 7-1. I scored all seven goals - a personal record. Afterwards, to my frenzied delight, Mr. Cole wheeled a handsome new bike round to my home. "I had a hunch you were going to score at least three goals," he told me, "so I took the precaution of having the bike ready."

(2) Nat Lofthouse, Goals Galore (1954)

That afternoon George Hunt was at inside-right, and from the first moment I kicked the ball I felt he was around to give me a helping hand. For a youngster of fifteen this match was something of an ordeal, and always shall I remember George Hunt for his sympathetic approach to the problem of helping a "new boy". I must also pay tribute to the considerate play of Bill Griffiths, the Bury centre-half. Had he wished, Bill could have forgotten I was little more than a boy and treated me as a full-grown opponent. Instead he never made things hard and his gentlemanly approach not only gained my admiration but also helped me to play my natural game.

Yes, for a lad of fifteen I had a pleasant debut, scoring twice. But I owed much to colleague George Hunt and opponent Bill Griffiths for this small success.

Apart from the satisfaction of scoring two goals for Bolton Wanderers I also received my first expenses. They amounted to two shillings and sixpence, and I remember thinking, "And they pay you for playing, too!"

With Bolton Wanderers favouring a policy of developing as many youngsters as possible, I realized that if I wanted to make headway in soccer it was essential I took the game seriously. I trained hard every Tuesday and Thursday evenings, putting everything I had into it. Some afternoons, by arrangement with my chief, Mr. Caffrey, I would have an hour or two off to receive coaching from George Hunt, and firmly believe that these private coaching sessions played a big part in my advancement. George Hunt, who was a very great centre-forward himself, possesses the rare ability to pass on to youngsters his own deep knowledge of the game.

When George is explaining points, it is easy to see why he was such a magnificent footballer. Out on the pitch at Burnden Park I learnt more from George in an hour than I could from most people in a year.

A typical example of Hunt's earnest efforts to make me the complete footballer was the patience he showed in teaching me to shoot with the left foot. I knew it was little more than a "swinger" when I joined Bolton-but Hunt did not say so. His approach proved to be the right one.

"Y'know, Nat," he said to me one day, "you've got a cracking shot in your right boot and your left isn't bad. But I do think we could make that left even stronger than the right. Let's give it a trial."

So for hours a day I used to go out on to the Burnden Park pitch, a carpet slipper on my right foot, and a soccer boot on my left. Hunt would toss a football at me from all angles, heights and speeds, and I was expected to hit it first time into the net.

George Hunt never scolded or unduly criticized me. He kept telling me my shooting was getting better, even if I did not always agree, and when we played together in matches George was constantly around encouraging me and pointing out errors.

Few young footballers have had a better chance to learn their trade. Bolton Wanderers, by playing me alongside George Hunt, made certain that I was given every opportunity of making the grade. When I was finally offered a professional engagement, I felt I owed much to the patience and tact of George Hunt.

Now I am a great believer in father and son sharing confidences. As a small boy I'd always sought and found "Dad's advice" right. With this in mind I asked Mr. Foweraker if I could bring my father along for a talk before signing any forms. He agreed to meet us the following Tuesday evening, and what a smart couple the Lofthouses were as they made their way into Burnden Park in their best suits.

After we had settled down in the Manager's office, my father with a whisky-and-soda and me with an orangeade, Mr. Foweraker quickly pointed out the bright future he felt sure would be mine when football was resumed after the war. I'd have signed without this "sales-talk", and it wasn't long before I was putting my signature on the form which made me a professional. I felt a little faint when I was handed my signing-on cheque for ££10. I'd never seen so much money in my life.

(3) Nat Lofthouse, Goals Galore (1954)

The miners of Britain are the finest fellows in the world. How do I know? Because I became a "Bevin Boy" during the war and worked alongside these men-men in every sense of the word. But it did not take me long to realize that in most cases their rugged exteriors hid hearts of gold.

I was only eighteen when I reported at Mossley Colliery, near Bolton, a pit in which I knew many of the Wanderers' supporters worked. I must admit that, although it was only a forty-five minutes' tram-ride from home, I had never visited such "distant parts". The one thing that sticks in my mind about that morning was the miners going on shift carrying their famous lamps.

Mr. Massey, the Labour Officer to whom I reported, was a sympathetic and understanding official. I think he realized that many youngsters like me, who were being whisked away from ordinary jobs to completely new surroundings, found things strange, and had he been my own father, Mr. Massey could not have gone to greater lengths in his efforts to make me feel at home.

To all intents and purposes that first day at the pit-head was like reporting to an Army or Navy depot. I was shown round the pit, saw the baths, was taken to the locker-room to get my number, then on to the lamp-room, where again I was given a number, and back to the office for a pay-check number, finally I was issued with a pit helmet. Candidly, none of this interested me a great deal. I felt I was only in the mining business because of National Service, and after I'd had a meal at the canteen and boarded the tram for home, a wave of depression swept over me. I wondered why I hadn't become a soldier like so many other footballers. But who was I to grumble? While many of my friends were fighting overseas I could still go home to my family. Later, I derived some comfort by reminding myself of this when things didn't go well at the pit.

The following day I reported once more at Mossley Common - this time for real work. I'll admit the job did not impress me. All I had to do was push empty tubs into the lift. Six weeks of this nearly drove me round the bend, but I was assured that when I went down the pit I'd find life more interesting. So for a time I dreamed about getting below ground. I was so anxious to get a more interesting job, it became almost an obsession.

Finally, however, the great day arrived and I climbed into the lift to descend into the darkness. But when the manager told me what my job was, I felt like handing in my cards. It was pushing tubs into the lift-the same boring job I had been doing at the pit-head.

"Be patient, Nat," said my mother, when I unfolded my troubles to her at supper. "Don't do or say anything which will upset people at the mine."

I took her advice, but found it difficult not to complain when shortly afterwards I was taken off this assignment and given one almost as boring. This time I worked on a little engine drawing empty tubs. How I hated the word "tubs". I even used to go home and dream about them. Nothing, it seemed, could separate Nat Lofthouse from empty pit-tubs. I made up my mind to ask the foreman for another job. "I'd like something harder-with more work," I said. "Right, son," replied Mr. Grundy, the official under whom I worked, "we'll get you the kind of job you want."

And promptly I found myself back with empty pit-tubs ! The only difference was that I had to push the empty tubs along to be loaded. But this time I did not complain.

The job proved to be the best I could possibly have had. It made me fitter than ever I had been before. My body became firmer and harder. I learnt to take hard knocks without feeling them. My legs became stronger and when I played football I felt I was shooting with greater power.

Nat Lofthouse celebrating the 1958 FA Cup victory.

(4) Nat Lofthouse, Goals Galore (1954)

The game hadn't been in progress long before I realized that these men from Yugoslavia were first-class footballers. They used the ball quickly and accurately. They never hesitated to use their broad shoulders, and Horvat, their 6 ft. 4 in. centre-half, stuck so close to me I began to think I owed him money. Horvat was a first-rate tackler, but it did not take me long to realize that the best way to worry the Yugoslav defenders was to swing the ball about from one wing to the other. Hancocks - who twice went near with cannon-ball shots of his own special brand - and Medley were soon in the picture, and it was from a wing-to-wing move that we took the lead after 30 minutes' play.

Hancocks, who kept bobbing up in the most unexpected places, pushed the ball inside to Mannion. As if on a piece of string it went on to Baily, who hit a first-time accurate pass high over the head of right-back Stankovic. Medley, running on to it, rammed the ball over to me. All I had to do was side-foot it into the net for my first goal for England.

Four minutes later England scored a second goal-and again Medley was the architect, placing the ball so accurately in the goalmouth that all I had to do was nod my head and the ball was nestling snugly in the back of the net.

(4) Nat Lofthouse, Goals Galore (1954)

Billy Moir, our captain, is a superstitious chap. Until he became captain of Bolton Wanderers he really believed he only gave of his best if he trotted on to the field last in the line. Taking over the captaincy altered all that, Billy had to be first on to the field but if anything his play seemed to improve even more, and facing Harry Johnston in the centre¬circle at Wembley he did what every good captain aspires to do. He won the toss, and decided to take advantage of a slight following wind.

The game that followed was one of the most dramatic in which I have played. After only two minutes I opened the scoring for Bolton Wanderers to complete my record of having scored in every round of the Cup.

There's always a thrill in scoring a goal. To score the first goal in a Cup Final, however, leaves an indelible impression on the mind. I can still recall vividly the move which led to that goal. The ball moved from the left wing across to right-winger Holden, a quick pass inside to me, and from 25 yards I let rip. Yes, there was plenty of sting behind my effort, but I must admit that I didn't quite make contact as I wanted to. Yet for all that George Farm, in the Blackpool goal, was rather late in moving towards the ball, and although I knew there was an element of luck about my goal, I nearly jumped over the Wembley grandstand with delight as I saw the ball finish up snugly in the back of the Blackpool goal.

This goal was a tremendous encouragement for our players and the team moved smoothly and with tremendous zest. But we encountered misfortune after 15 minutes when left-half Eric Bell was injured. In the end this led to a re¬shuffle, Bobby Langton moved to inside-left, Bell took over from him at outside-left, and Harold Hassall dropped into the left-half position vacated by Bell. Even then we did not lose our poise and purpose, but Blackpool, hitting back hard, equalized after 15 minutes when Stan Mortensen closed in and saw a hard drive accidentally deflected into our net by the unfortunate Harold Hassall.

Four minutes later we again went into the lead, and once more it was the outcome of an extraordinary goal. Bobby Langton swung over a low cross and Billy Moir rose with goalkeeper George Farm in an effort to reach it.

Moir missed the ball but Farm harassed by the Bolton skipper misjudged the flight and it swung in over his shoulder to finish up in the back of the goal.

Poor George Farm! I sincerely felt sorry for him. It was one of those unpredictable afternoons when nothing seemed to go right for him. Two goals had been scored against him; both from shots which normally the great Scottish international would have gathered with ease.

At half-time, as we walked off the field, Stan Mortensen came up to me and shook my hand. "Well played, Nat," he said, "and congratulations on scoring in every round."

Yes, out there on the Wembley pitch, with Blackpool losing 2-i, Stan Mortensen proved once again what a prince of sportsmen he is. The gesture convinced me - if I needed convincing - that the age of chivalry and good sportsmanship is not a thing of the past.

Does half-time in a Cup Final bring a return of the nerves from which so many footballers are alleged to suffer before this great match and which seem to disappear once the game has got under way? This is a question that has often been fired at me and to be quite honest I have never been able to answer with any degree of confidence. For my part once the game started it ceased to be the F.A. Cup Final. To me it was just another soccer match. The rest of the players felt the same. We were determined to win but there were no signs of tension.

We knew that with only ten fit men, the opening minutes of the second half would be a testing time for Bolton. Tactically we could not afford to allow Blackpool to exploit the weakness, and by one of those quirks of fate which help make soccer such an exciting and unpredictable game, ten minutes after the resumption we scored a third goal. The scorer was Eric Bell, our crippled left-half-back! Again it was a goal to remember. Duggie Holden, on our right wing, swung over a delightful centre. It was the kind of cross one delights to run on to and hit hard and true with the head. Eric Bell, forgetting all about his pain, did precisely that and the ball streaked past Farm giving him no possible chance.

With a two goals' lead, and the team playing inspired football, we already had visions of Billy Moir going up to collect the Cup from the Queen. It seemed the Cup was as good as in the Board Room at Burnden Park.

It was then that Stanley Matthews decided to take a hand in things. The great winger, spurred on by the thought of losing yet another Cup winners' medal, produced every trick in his vast repertoire. With the crowd urging him on, Stanley rose to tremendous heights. It was his greatest hour, and for us long minutes of torment as he played football with the artistry we shall ever associate with his name. After 67 minutes one of Stanley's delightful centres seemed to wriggle out of the grasp of goalkeeper Hanson, and Mortensen was on the spot to slam it into the goal. Two minutes from the end 'Mortie' equalized with a magnificent shot from a free-kick, and everyone thought we were in for extra time-everyone that is except Stanley Matthews. With Referee Griffiths glancing at his watch Stanley crossed an accurate centre to Bill Perry, Blackpool's South African left-winger who fired a tremendous shot past Hanson.

That Perry goal was the winner, and when Mr. Griffiths whistled up for time a feeling of utter dejection swept over me. As we lined up to receive our medals from the Queen my colleagues and I shook hands with the Blackpool players and offered our congratulations. As I clasped Matthews' hand I said: "Well done, Stan, but I wish it was me instead of you."

"I know how you feel, Nat," replied Stan Matthews. "It's happened to me twice before."

Poor Bill Ridding. Our popular manager was too full to say anything. As we walked disconsolately from the field a crowd of our followers gallantly cheering and waving the blue and white colours of Bolton Wanderers brought a lump to our throats and I confess that when I reached the dressing-room I broke down for the first time since I was a boy and wept unashamedly.

(6) The Daily Telegraph (16th January 2011)

Nathaniel Lofthouse was born in Bolton on August 27 1925, the youngest of four sons. His father worked as a coal-bagger and later as head horsekeeper for the town’s Corporation.

Nat played his first school match as a goalkeeper. He conceded seven, and was scolded by his mother for ruining his best pair of leather shoes. He decided to become a centre-forward instead, and diligently practised his heading against a wall during lunchtimes. On his debut for Bolton Schools, it was he who scored seven goals.

He signed as an amateur for Bolton Wanderers the day after the outbreak of the Second World War and made his league debut against Bury at the age of 15, scoring twice. Too young for military service, during the war he worked as a Bevin Boy in the mines, rising at half past three in the morning to put in a 10-hour shift hauling coal tubs before training with Wanderers in the afternoon. The work made him immensely strong (“It toughened me up, physically and mentally,” he later said), although he was forced to endure teasing from the older miners if he had a poor match.

As a player he was initially somewhat clumsy, and he never became overly subtle; but his physical presence made him very difficult to play against. Though only 5ft 9in tall, he weighed more than 12 stone, and was nigh unbeatable in the air. He also had a healthy turn of speed, and a fierce shot with both feet, especially his left.

Lofthouse remained with Bolton for his entire career, playing 503 games for the club and scoring 285 goals, a mark which remains the club record. He also captained the side for several seasons. In 1946 he was on the pitch at Burnden Park as a crowd of 85,000 tried to get into Bolton’s ground to watch an FA Cup tie. Thirty-three people lost their lives in the crush.

He was first selected for England in 1950, succeeding his childhood idol Tommy Lawton in the side. Lofthouse scored twice on his debut, against Yugoslavia, and went on to play in the 1954 World Cup in Switzerland, picking up three goals in the tournament, including one in England’s 4-2 defeat by Uruguay in the quarter-final.

Although then in prime form, like Stanley Matthews he was ignored by the amateurish selection panel that chose the team for the 1958 competition. He was, however, recalled to the side the following year, and equalled Finney’s then record number of international goals. Lofthouse’s final strike rate of 30 goals in 33 matches was among the best achieved by a forward in an England shirt.

(7) Brian Glanville, The Guardian (16th January 2011)

The footballer Nat Lofthouse, who has died aged 85, won 33 England caps during a career spent entirely with one club, Bolton Wanderers. His most memorable performance, which won him the nickname the "Lion of Vienna", was for England against Austria in May 1952. Friendly internationals then held an importance that has now all but vanished, and Lofthouse's winning goal, in a 3-2 victory against a powerful team, was lauded to the skies.

Six years later, he scored both goals for Bolton Wanderers when they beat Manchester United 2-0 in the 1958 FA Cup final at Wembley. The second goal, when he crashed into United's goalkeeper Harry Gregg in mid-air as he caught a high cross, was probably illegal – as Lofthouse himself would later admit. But it still counted. A few months later, he was back at Wembley to terrorise the Russian goalkeeper with his robust challenges, helping England to win 5-0. The superb left-footed shot on the turn which scored England's fifth and last goal was his 30th for England, equalling what was then Tom Finney's record.

This made it the more bitterly ironic that Lofthouse, inexplicably, had been left out of the England World Cup team which, the previous summer, had been knocked out of the tournament by the Russians. The international career of this powerfully built centre-forward never quite matched his fame, though it began as early as 1950, when he was capped at Highbury against Yugoslavia. He did figure in the 1954 World Cup in Switzerland, playing in the opening game against Belgium and in the quarter-finals when England lost 4-2 to Uruguay, Lofthouse scoring a goal. Perhaps his style was a little too traditional for the England selectors and the team manager, Walter Winterbottom.