War Propaganda Bureau (original) (raw)

Soon after the outbreak of the First World War, in August 1914, the British government discovered that Germany had a Propaganda Agency. David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was given the task of setting up a British War Propaganda Bureau (WPB). Lloyd George, appointed the successful writer and fellow Liberal MP, Charles Masterman as head of the organization.

On 2nd September, 1914, Masterman invited twenty-five leading British authors to Wellington House, the headquarters of the War Propaganda Bureau, to discuss ways of best promoting Britain's interests during the war. Those who attended the meeting included Arthur Conan Doyle, Arnold Bennett, John Masefield, Ford Madox Ford, William Archer, G. K. Chesterton, Sir Henry Newbolt, John Galsworthy, Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, Gilbert Parker, G. M. Trevelyan and H. G. Wells.

All the writers present at the conference agreed to the utmost secrecy, and it was not until 1935 that the activities of the War Propaganda Bureau became known to the general public. Several of the men who attending the meeting agreed to write pamphlets and books that would promote the government's view of the situation. The bureau got commercial companies to print and publish the material. This included Hodder & Stoughton, Methuen, Oxford University Press, John Murray, Macmillan and Thomas Nelson.

One of the first pamphlets to be published was Report on Alleged German Outrages, that appeared at the beginning of 1915. This pamphlet attempted to give credence to the idea that the German Army had systematically tortured Belgian civilians. The great Dutch illustrator, Louis Raemakers, was recruited to provide the highly emotionally drawings that appeared in the pamphlet.

The WPB published over 1160 pamphlets during the war. This included To Arms! (Arthur Conan Doyle), The Barbarism in Berlin (G. K. Chesterton), The New Army (Rudyard Kipling), The Two Maps of Europe (Hilaire Belloc), Liberty , A Statement of the British Case and War Scenes on the Western Front (Arnold Bennett), Is England Apathetic? (Gilbert Parker), Gallipoli and the Old Front Line (John Masefield), The Battle of Jutland and The Battle of the Somme (John Buchan), A Sheaf and Another Sheaf (John Galsworthy), England's Effort and Towards the Goal (Mary Humphrey Ward) and When Blood is Their Argument (Ford Madox Ford).

One of the first projects devised by Charles Masterman was the publication of a history of the war in the form of a monthly magazine. He recruited John Buchan to take charge of its production. Published by Buchan's own company, Thomas Nelson, the first installment of the Nelson's History of the War, appeared in February, 1915. A further twenty-three editions appeared at regular intervals throughout the war. Given the rank of Second Lieutenant in the Intelligence Corps, Buchan was also provided with the documents needed to write the book. General Headquarters Staff (GHQ) saw this as good for propaganda as Buchan's close relationship with Britain's military leaders made it extremely difficult for him to include any critical comments about the way the war was being fought.

Only two photographers, both army officers, were allowed to take pictures of the Western Front. The penalty for anyone else caught taking a photograph of the war was the firing squad. Charles Masterman was aware that the right sort of pictures would help the war effort. In May 1916 Masterman recruited the artist, Muirhead Bone. He was sent to France and by October had produced 150 drawings of the war. When Bone returned to England he was replaced by his brother-in-law, Francis Dodd, who had been working for the Manchester Guardian.

As soon as David Lloyd George became prime minister in December 1916, he invited Robert Donald to join the secret War Propaganda Bureau. Donald was asked to write a report on the effectiveness of the organisation. As a result of Donald's recommendations, the government established a Department of Information. John Buchan was put in charge on the department on an annual salary of £1,000 a year. Charles Masterman was given responsibility for books, pamphlets, photographs and war paintings and T. L. Gilmour dealt with cables, wireless, newspapers, magazines and the cinema.

In February, 1917, the government established a Department of Information. Given the rank Lieutenant Colonel, John Buchan was put in charge on the department on an annual salary of £1,000 a year. Charles Masterman retained responsibility for books, pamphlets, photographs and war paintings and T. L. Gilmour dealt with cables, wireless, newspapers, magazines and the cinema.

William Rothenstein offered his services to the WPB but because of his German connections he was initially turned down. He eventually went in December 1917. Soon after he arrived on the Somme front he was arrested as a spy. He stayed with the British Fifth Army in 1918 and during the German Spring Offensive, served as a unofficial medical orderly. He returned to England in March and his pictures were exhibited in May, 1918. Pictures by Rothenstein included The Ypres Salient and Talbot House, Ypres.

Early in 1918 the government decided that a senior government figure should take over responsibility for propaganda. On 4th March Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Daily Express, was made Minister of Information. Under him was Charles Masterman (Director of Publications) and John Buchan (Director of Intelligence). Lord Northcliffe, the owner of both The Times and the Daily Mail, was put in charge of all propaganda directed at enemy countries. Robert Donald, editor of the Daily Chronicle, was appointed director of propaganda in neutral countries. On the announcement in February 1918, David Lloyd George was accused in the House of Commons of using this new system of getting control over all the leading figures in Fleet Street.

Beaverbrook decided to rapidly expand the number of artists in France. He established with Arnold Bennett a British War Memorial Committee (BWMC). The artist chosen for this programme were given different instructions to those sent previously. Beaverbrook told them that pictures were "no longer considered primarily as a contribution to propaganda, they were now to be thought of chiefly as a record."

Artists sent abroad under the BWMC programme included John Sargent, Augustus John, John Nash, Henry Lamb, Henry Tonks, Eric Kennington, William Orpen, Paul Nash, C. R. W. Nevinson, Colin Gill, William Roberts, WyndhamLewis, Stanley Spencer, Philip Wilson Steer, George Clausen, Bernard Meninsky, Charles Pears, Sydney Carline, David Bomberg, Austin Osman Spare, Gilbert Ledward and Charles Jagger.

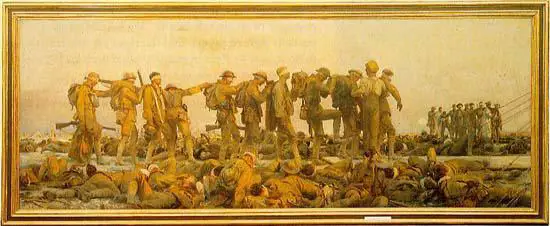

David Lloyd George asked John Singer Sargent to paint a picture showing collaboration between British and US troops. Sargent rejected the commission and instead painted Gassed, that showed a group of soldiers suffering from the effects of gas.

Overall, over ninety artists produced pictures for the government during the war. Many of the artists found the work very difficult. Some like Augustus John produced very little, whereas others, such as Paul Nash complained about the control over subject matter. Nash told a friend: "I am not allowed to put dead men into my pictures because apparently they don't exist". On another occasion he said: "I am no longer an artist. I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth and may it burn their lousy souls."

At the end of the war William Orpen was asked by the War Artists Advisory Committee to portray leaders such as Sir Douglas Haig, Hugh Trenchard, Herbert Plumer and Ferdinand Foch. His biographer, Bruce Arnold, points out: "He left for France in April 1917, and for the next four years was totally immersed in the war and its aftermath. His output, and its overall excellence, makes him the outstanding war artist of that period, possibly the greatest war artist produced in Britain. Analysis of his war work, the major part of which is in the Imperial War Museum, London, shows a development in style and understanding, from the idealism which inspired him when he first arrived at the front to the disillusionment with the terrible ending to the war, and then the further dismay he and many felt at the direction taken by the peace deliberations. His paintings of the Somme battlefields are haunting recollections of anguish and chaos, of ruined landscapes baked in the summer sun, the torn ground white and rocky, the debris of the dead scattered and ignored." Orpen was shocked by what he saw at the front and also painted pictures such as Dead Germans in a Trench. Other paintings such as The Mad Woman of Douai, Bombfire in Picardy and The Harvest, "convey the stress and anguish he certainly felt about the war and its aftermath".

The fiercest critic of the propaganda scheme was Charles Nevinson. Some of Nevinson's paintings such as Paths of Glory, were considered to be unacceptable and were not exhibited until after the Armistice. He shared the feelings of Paul Nash who wrote at the time: "I am no longer an artist. I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth and may it burn their lousy souls."

William Orpen, Dead Germans in a Trench (1917)

Primary Sources

(1) In his book Falsehood in Wartime, Arthur Ponsonby explained the role of wartime propaganda.

People must never be allowed to become despondent; so victories must be exaggerated and defeats, if not concealed, at any rate minimized, and the stimulus of indignation, horror and hatred must be assiduously and continuously pumped into the public minds of 'propaganda'.

(2) Hiliare Belloc, letter to G. K. Chesterton (12 December, 1917)

It is sometimes necessary to lie damnably in the interests of the nation. It wasn't only numbers that lost us Cambrai; it was very bad staff work on the south side. Things like thought oughtn't to happen.

(3) After the war William Beach Thomas wrote about his report on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in his book, A Traveller in News (1925)

I was thoroughly and deeply ashamed of what I had written, for the good reason that it was untrue. The vulgarity of enormous headlines and the enormity of one's own name did not lessen the shame.

(4) Philip Gibbs, Adventures in Journalism (1923)

We identified ourselves absolutely with the Armies in the field. We wiped out of our minds all thought of personal scoops and all temptation to write one word which would make the task of officers and men more difficult or dangerous. There was no need of censorship of our despatches. We were our own censors.

(5) C. E. Montague, Disenchantment (1922)

The average war correspondent - there were golden exceptions - insensibly acquired a cheerfulness in the face of vicarious torment and danger. Through his despatches there ran a brisk implication that the regimental officers and men enjoyed nothing better than "going over the top"; that a battle was just a rough jovial picnic, that a fight never went on long enough for the men, that their only fear was lest the war should end this side of the Rhine. This tone roused the fighting troops to fury against the writers. This, the men reflected, in helpless anger, was what people at home were offered as faithful accounts of what their friends in the field were thinking and suffering.

(6) Robert Donald, press release (February, 1918)

I have been asked to become the Director of of a section of propaganda work. I could not undertake work of this kind if it interfered with my editorial responsibilities or my political independence, or if it did not give me liberty of action within the sphere allotted to me. After all, this is a newspaper man's job. It consists simply of presenting the British case in neutral and allied countries in a form which is at once interesting and informative.