Household Words (original) (raw)

In February 1850, Charles Dickens decided to join forces with his publisher, Bradbury & Evans, and his friend, John Forster, to publish the journal, Household Words . Dickens became editor and William Wills, a journalist he worked with on the Daily News, became his assistant. One colleague described Wills as "a very intelligent and industrious man... but rather too gentle and compliant always to enforce his own intentions effectually upon others." Dickens thought that Wills was the ideal man for the job. He commented that "Wills has no genius, and is, in literary matters, sufficiently commonplace to represent a very large proportion of our readers".

Dickens rented an office at 16 Wellington Street North, a small and narrow thoroughfare just off the Strand. Dickens described it as "exceedingly pretty with the bowed front, the bow reaching up for two stories, each giving a flood of light." Dickens announced that aim of the journal would be the "raising up of those that are down, and the general improvement of our social condition". He argued that it was necessary to reform a society where "infancy was made stunted, ugly, and full of pain; maturity made old, and old age imbecile; and pauperism made hopeless every day." He added that he wanted London to "set an example of humanity and justice to the whole Empire".

Dickens planned to serialise his new novels in the journal. Another project was the serialisation of A Child's History of England. He also wanted to promote the work of like-minded writers. The first person he contacted was Elizabeth Gaskell. Dickens had been very impressed with her first novel, Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life (1848) and offered to take her future work. She sent him Lizzie Leigh , a story about a Manchester prostitute, which appeared in the first issue, on 30th March 1850.

After lengthy negotiations it was agreed that Charles Dickens would have half share in all profits of Household Words. Bradbury & Evans to have one quarter, John Forster and William Henry Wills, one eighth each. Whereas the publisher was to manage all the commercial details, Dickens was to be in sole charge of editorial policy and content. Dickens was also paid £40 a month for his services as editor and a fee was agreed for any articles and stories published by the journal. The first edition of the journal appeared on 30th March, 1850. It contained 24 pages and cost twopence and came out every Wednesday. On the top of each page were the words: "Conducted by Charles Dickens". All contributions were anonymous but when his friend, Douglas Jerrold, read it for the first time, he commented that it was "mononymous throughout". Elizabeth Gaskell described the content as "Dickensy".

On 12th April 1850 Dickens wrote to his close friend, Angela Burdett Coutts: "The Household Words I hope (and have every reason to hope) will become a good property. It is exceedingly well liked, and goes, in the trade phrase, admirably. I daresay I shall be able to tell you, by the end of the month, what the steady sale is. It is quite as high now, as I ever anticipated; and although the expenses of such a venture are necessarily very great, the circulation much more than pays them, so far. The labor, in conjunction with Copperfield, is something rather ponderous; but to establish it firmly would be to gain such an immense point for the future (I mean my future) that I think nothing of that."

Claire Tomalin wrote that with the journal: "He set out to raise standards of journalism in the crowded field of periodical publication and, by winning educated readers and speaking to their consciences, to exert some influence on public matters; and to this end he himself wrote on many social issues - housing, sanitation, education, accidents in factories, workhouses, and in defence of the right of the poor to enjoy Sundays as they chose."

The journal was a great success and it was soon selling 39,000 copies. Peter Ackroyd has argued: "It was nothing like such serious journals as The Edinburgh Review - it was not in any sense intellectual - but rather took its place among the magazines which heralded or exploited the growth of the reading public throughout this period... Since this was not the cleverest, the most scholarly or even the most imaginative audience in Britain, Household Words had to be cheerful, bright, informative and, above all, readable." In its first year Dickens earned an extra £1,700 from the journal and in the second year of trading, £2,000.

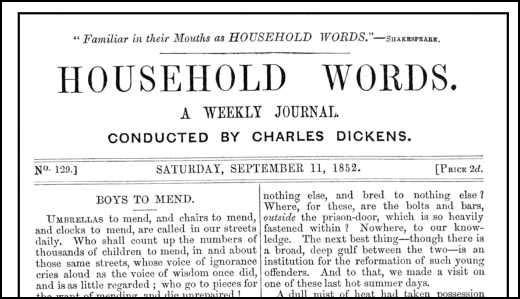

Household Words (11th September, 1852)

The leading article was usually written by John Forster. Other contributors included Wilkie Collins, Eliza Lynn Linton, Blanchard Jerrold, George Augustus Sala and Percy Fitzgerald. Sala later recalled meeting Dickens for the first time: "I was overcome with astonishment at the sight of the spare, wiry gentleman who, standing on the hearthrug, shook me cordially by the hand - both hands, if I remember alright... He was then, I should say, barely forty; yet to my eyes he seemed to be rapidly approaching fifty." Fitzgerald later commented on the way Dickens edited the journal: "the way he used to scatter his bright touches over the whole, the sparkling word of his own that he would insert here and there, gave a surprising point and light."

Elizabeth Gaskell continued to publish stories in Household Words including Traits and Stories of the Huguenots , Morton Hall , My French Master , The Squire's Story , Company Manners , An Accursed Race , Half a Lifetime Ago , The Poor Clare , My Lady Ludlow , The Sin of a Father and The Manchester Marriage . She also produced a series of stories that were published between 13th December 1851 and 21st May 1853, that eventually became the novel, Cranford. Her biographer, Jenny Uglow has suggested that the Cranford stories "make the dangerous safe, touching the tenderest spots of memory and bringing the single, the odd and the wanderer into the circle of family and community."

Jane W. Stedman has argued: "For this periodical, Wills performed the multitudinous tasks of a working editor, from proof-reading and dealing with an enormous amount of correspondence, to frequently settling both the contents and order of each number. He kept the office book, listing each contributor, his work, and payment (which he had a tendency to pare down). For all of this, Wills was paid £8 per week, his contributions included. And yet his role was pivotal—although Dickens was not an easy editor.

Margaret Dalziel has argued in her book, Popular Fiction 100 Years Ago (1957), that it was similar to Eliza Cook's Journal: "Both were weeklies a little more expensive than those designed for the very poor (Household Words cost twopence, Eliza Cook's Journal a penny-halfpenny); both were bent on exploiting a well known name in their struggle to attract readers; and there was considerable similarity in their contents. Both spurned the facile attractions of riddles, puzzles, illustrations, correspondence columns, and so on. Both were keenly interested in social problems, and in emigration as a solution for them. Both gave less space to fiction than to articles and sketches."

In May 1855 Charles Dickens joined with the Liberal Party MP, Austen Layard, to form the Association for Administrative Reform. He spoke at several public meetings for the organisation and it was suggested that Dickens should stand for the House of Commons. Dickens replied that he had no intention of entering politics himself: "literature is my profession - it is at once my business and my pleasure, and I shall never pass beyond it."

Dickens image as a social reformer was very important to him. After publishing an anti-woman's rights article by Eliza Lynn Linton he told William Wills: "it gets so near the sexual side of things as to be a little dangerous to us at times." He also got worried about an article by Wilkie Collins about the the behaviour of the wealthy in England. He told Wills that in future he must edit his work as "not to leave anything in it that may be sweeping, and unnecessarily offensive to the middle class".

Elizabeth Gaskell contributed a large number of short stories to Household Words. Her novel, North and South (1855), appeared in the journal between 2nd September 1854 and 27 January 1855. Peter Ackroyd, the author of Dickens (1990) has pointed out: "Mrs Gaskell's North and South, which was proving too long and too unwieldy for serial publication. Mrs Gaskell herself was also somewhat difficult, particularly in her inability or slowness to cut her text as Dickens desired; nothing irritated him more than unprofessional behaviour, especially in novelists whom he knew to be inferior to himself, and although he kept his own communications with Mrs Gaskell relatively courteous he was far from flattering about her to his deputy." Gaskell was also often late in delivering her manuscript. Dickens commented to William Henry Wills that if he was her husband, he would feel compelled to "beat her". Dickens eventually edited the serial and she regarded the abrupt ending of the serial version as "mutilated... like a pantomime figure with a great large head and a very small trunk".

In September, 1857, Dickens wrote to Angela Burdett Coutts, about his decision to write a novel about the French Revolution. "Sometimes of late, when I have been very much excited by the crying of two thousand people over the grave of Richard Wardour, new ideas for a story have come into my head as I lay on the ground, with surprising force and brilliancy". Wardour was the character he played in The Frozen Deep.

Charles Dickens research involved talking to his great friend, Thomas Carlyle, the author of the book, The French Revolution (1837). Peter Ackroyd, the author of Dickens (1990), has pointed out: "He (Dickens) had always admired Carlyle's History of the French Revolution, and asked him to recommend suitable books from which he could research the period; in reply Carlyle sent him a cartload of volumes from the London Library. Apparently Dickens read, or at least looked through, them all; it was his aim during the period of composition only to read books of the period itself."

Dickens decided he would not publish A Tale of Two Cities in Household Words. Jealous of the money that Bradbury & Evans had made out of the venture, he decided to start a new journal, All the Year Round. He had 300,000 handbills and posters printed, in order to advertise the new journal. When Bradbury & Evans heard the news they issued an injunction claiming that Dickens was still contracted to work for their journal.

Dickens refused to back-down and the first edition of the journal was published on 30th April 1859. For the first time in his life he had sole control of a journal. "He owned it, he edited it, and only he could take the major decisions concerning it." This was reinforced by the masthead that said: "A weekly journal conducted by Charles Dickens."

Primary Sources

(1) Claire Tomalin, Dickens: A Life (2011)

He (Charles Dickens) set out to raise standards of journalism in the crowded field of periodical publication and, by winning educated readers and speaking to their consciences, to exert some influence on public matters; and to this end he himself wrote on many social issues - housing, sanitation, education, accidents in factories, workhouses, and in defence of the right of the poor to enjoy Sundays as they chose.

(2) ****Peter Ackroyd, Dickens (1990)**

So it was by trial and error that Dickens was able to assemble a team of writers around him. Among the first of his regular contributors were Henry Morley, R. H. Horne, Dudley Costello and Blanchard Jerrold; some of them had worked with him on the Daily News and some of them were young aspiring writers who naturally tended to copy him and were for a while branded as "slavish imitators" of his style. In later years others joined this inner circle of regular writers, among them Percy Fitzgerald, G.A.H. Sala, and Wilkie Collins.

(3) Margaret Dalziel, Popular Fiction 100 Years Ago (1957)

Both were weeklies a little more expensive than those designed for the very poor (Household Words cost twopence, Eliza Cook's Journal a penny-halfpenny); both were bent on exploiting a well known name in their struggle to attract readers; and there was considerable similarity in their contents. Both spurned the facile attractions of riddles, puzzles, illustrations, correspondence columns, and so on. Both were keenly interested in social problems, and in emigration as a solution for them. Both gave less space to fiction than to articles and sketches.

(4) Charles Dickens, letter to Angela Burdett Coutts (12th April, 1850)

The Household Words I hope (and have every reason to hope) will become a good property. It is exceedingly well liked, and goes, in the trade phrase, admirably. I daresay I shall be able to tell you, by the end of the month, what the steady sale is. It is quite as high now, as I ever anticipated; and although the expenses of such a venture are necessarily very great, the circulation much more than pays them, so far. The labor, in conjunction with Copperfield, is something rather ponderous; but to establish it firmly would be to gain such an immense point for the future (I mean my future) that I think nothing of that.

(5) Charles Dickens, Household Words (12th June, 1858)

Some domestic trouble of mine, of long-standing, on which I will make no further remark than that it claims to be respected, as being of a sacredly private nature, has lately been brought to an arrangement, which involves no anger or ill-will of any kind, and the whole origin, progress, and surrounding circumstances of which have been, throughout, within the knowledge of my children. It is amicably composed, and its details have now to be forgotten by those concerned in it... By some means, arising out of wickedness, or out of folly, or out of inconceivable wild chance, or out of all three, this trouble has been the occasion of misrepresentations, mostly grossly false, most monstrous, and most cruel - involving, not only me, but innocent persons dear to my heart... I most solemnly declare, then - and this I do both in my own name and in my wife's name - that all the lately whispered rumours touching the trouble, at which I have glanced, are abominably false. And whosoever repeats one of them after this denial, will lie as wilfully and as foully as it is possible for any false witness to lie, before heaven and earth.